Isolation and Characterization of Phosphate-Solubilizing Rhizobacteria from Solanum tuberosum with Plant Growth-Promoting Activity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation and Purification of Bacterial Isolates

2.2. Cultural Characterization

2.3. Morphology Characterization

2.4. In Vitro Phosphate Solubilization Activity

2.5. Molecular Identification and Characterization

2.5.1. DNA Extraction

2.5.2. PCR Amplification

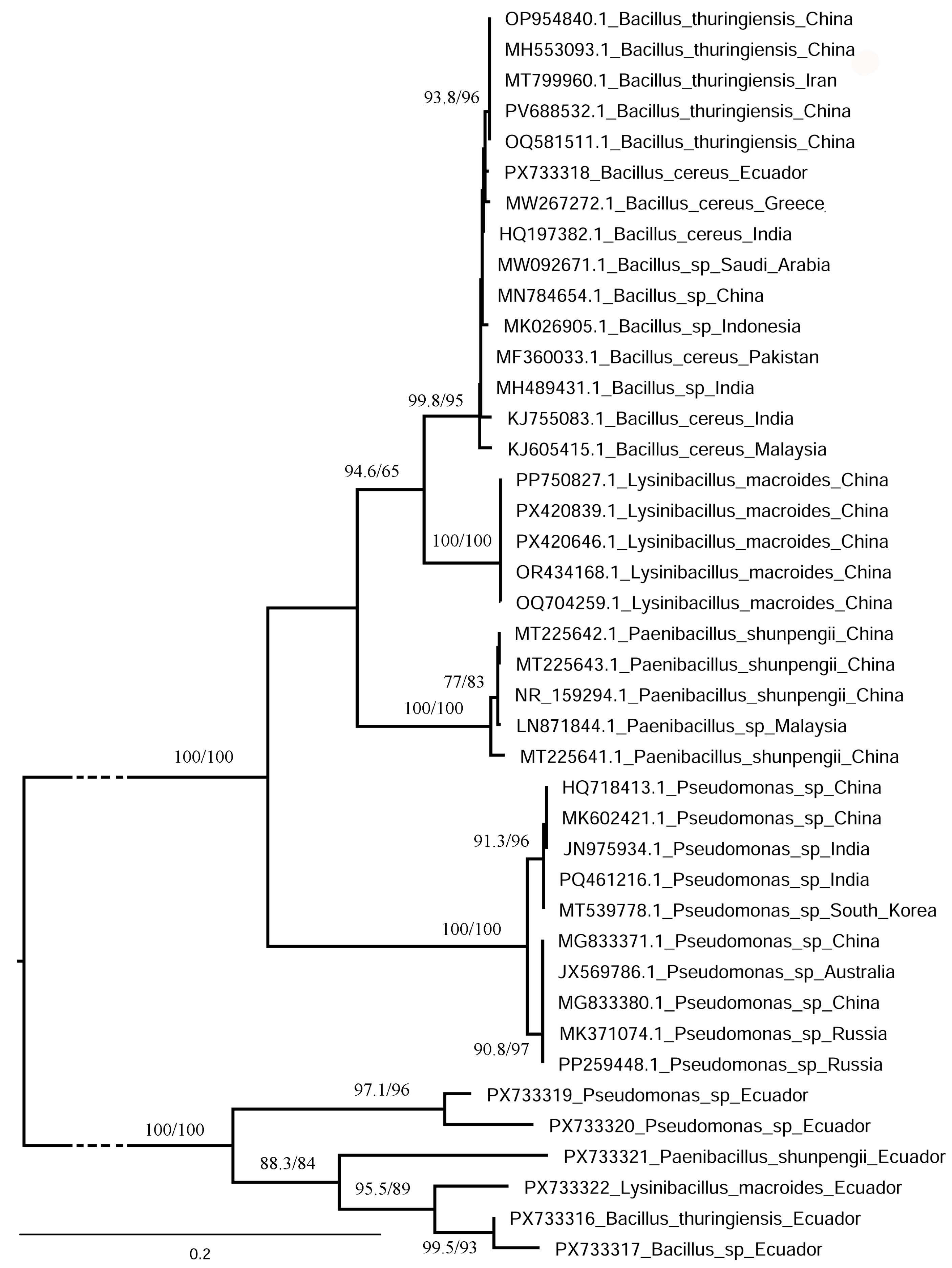

2.5.3. Phylogenetic Analysis

2.6. Plant Growth-Promoting Activity Under Greenhouse Conditions

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Isolation and Purification of Bacterial Isolates

3.2. Cultural Characterization

3.3. Morphological Characterization

3.4. In Vitro Phosphate Solubilization Activity

3.5. Molecular Identification and Characterization

3.6. Plant Growth-Promoting Activity Under Greenhouse Conditions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ali, S.; Riaz, A.; Mamtaz, S.; Haider, H. Nutrients and Crop Production. Curr. Res. Agric. Farm. 2023, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, N.A.; Masood, A.; Umar, S.; Khan, N.A. Introductory Chapter: Phosphorus in Soils and Plants. In Phosphorus in Soils and Plants; Anjum, N.A., Masood, A., Umar, S., Khan, N.A., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, R.J.; Naidu, R. Phosphorus—An essential input for agriculture yet a key pollutant of surface waters. In Inorganic Contaminants and Radionuclides; Naidu, R., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 405–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaragamage, D.; Hettiarachchi, G.M.; Amarakoon, I.; Goltz, D.; Indraratne, S. Phosphorus fractions and speciation in an alkaline, manured soil amended with alum, gypsum, and Epsom salt. J. Environ. Qual. 2024, 53, 314–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.; Shankar, A.; Chaudhary, S.; Prasad, V. Phosphate Solubilizing Microorganisms: Multifarious Applications. In Plant Microbiome for Plant Productivity and Sustainable Agriculture; Microorganisms for Sustainability; Chhabra, S., Prasad, R., Maddela, N.R., Tuteja, N., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Siddiqui, M.H.; Ahmad, S.; Ahmad, M.M.; Siddiqui, S. New insights in enhancing the phosphorus use efficiency using phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms and their role in cropping system. Geomicrobiol. J. 2024, 41, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambafu, G.N.; Hoeppner, N.; Bessler, H.; Gweyi-Onyango, J.P.; Andika, D.O.; Mwonga, S.; Engels, C. Influence of soil phosphorus fertilizer forms on phosphorus uptake, morphology, and growth of leafy vegetables. Discov. Soil 2025, 2, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Liu, J.; Jin, J.; Han, Y.; Wei, Z. Effects of low-molecular-weight organic acids on the transformation and phosphate retention of iron (hydr) oxides. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 940, 173667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, H.A.; El-Hady, M.A. Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacterial Enzyme Dynamics in Soil Remediation. In Plant-Microbe Interactions for Environmental and Agricultural Sustainability; Pandey, A., Choure, K., El-Sheekh, M., Yadav, A.A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 247–304. [Google Scholar]

- Gerke, J. Improving phosphate acquisition from soil via higher plants while approaching peak phosphorus worldwide: A critical review of current concepts and misconceptions. Plants 2024, 13, 3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etesami, H.; Jeong, B.R.; Glick, B.R. Contribution of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, phosphate–solubilizing bacteria, and silicon to P uptake by plant. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 699618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicka, B.; Barbaś, P.; Vambol, V.; Skiba, D.; Pszczółkowski, P.; Niazi, P.; Bienia, B. Applied Microbiology for Sustainable Agricultural Development. Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 5, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Shen, Y.; Shen, F. Optimizing fertilization strategies for high-yield potato crops. Mol. Soil Biol. 2025, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambers, H. Phosphorus Acquisition and Utilization in Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2022, 73, 17–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chea, L.; Meijide, A.; Meinen, C.; Pawelzik, E.; Naumann, M. Cultivar-dependent responses in plant growth, leaf physiology, phosphorus use efficiency, and tuber quality of potatoes under limited phosphorus availability conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 723862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.K.; Dash, G.K.; Pati, S.; Sahoo, D.; Lenka, B.; Nayak, L.; Guhey, A. Physiological and biochemical mechanisms in underground vegetable crops for growth and development. In Abiotic Stress in Underground Vegetables; Lal, M.K., Tiwari, R.K., Kumar, A., Kumar, R., Singh, B., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025; pp. 39–53. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, L.I.; Pereira, M.C.; de Carvalho, A.M.X.; Buttros, V.H.; Pasqual, M.; Doria, J. Phosphorus-solubilizing microorganisms: A key to sustainable agriculture. Agriculture 2023, 13, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Xing, Y.; Li, Y.; Jia, J.; Ying, Y.; Shi, W. The role of phosphate-solubilizing microbial interactions in phosphorus activation and utilization in plant–soil systems: A review. Plants 2024, 13, 2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Montaño, F.; Aparicio, N.; Arenas, F.; Arjona, J.M.; Camacho, M.; Fernández-García, N.; Reguera, M. Emerging crops and plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB): A synergistic approach to climate-resilient agriculture. Microbiome 2025, 13, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Li, C.; Su, X.; Yang, M.; Li, W.; Li, H. Rhizosphere microorganisms mediate ion homeostasis in cucumber seedlings: A new strategy to improve plant salt tolerance. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, P.; Wang, B.; Li, H.; Li, S.; Zhang, H.; Li, X. Harnessing the role of rhizo-bacteria to mitigate salinity stress in rice (Orzya sativa); focus on antioxidant defense system, photosynthesis response, and rhizosphere microbial diversity. Rhizosphere 2025, 33, 101043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, H.S.; Kumar, A.; Singh, M.P.; Singh, A.; Maurya, N.K.; Kumar, R. A Comprehensive Review on Plant-Soil Interactions: Microbial Dynamics, Nutrient Cycling and Sustainable Crop Production. Asian J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2025, 11, 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Wei, C.; Wang, H.; He, Z.; Zhang, F.; Lei, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, S.; Yan, L. Responses of the potato rhizosphere bacterial communities to Ralstonia solanacearum infection and their roles in binary disease outcomes. Plant Soil 2025, 514, 2349–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amri, M.; Rjeibi, M.R.; Gatrouni, M.; Mateus, D.M.R.; Asses, N.; Pinho, H.J.O.; Abbes, C. Isolation, Identification, and Characterization of Phosphate-Solubilizing Bacteria from Tunisian Soils. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouy, M.; Guindon, S.; Gascuel, O. SeaView Version 4: A Multiplatform Graphical User Interface for Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Tree Building. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2010, 27, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyaanamoorthy, S.; Minh, B.Q.; Wong, T.K.F.; Von Haeseler, A.; Jermiin, L.S. ModelFinder: Fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.-T.; Schmidt, H.A.; Von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. IQ-TREE: A Fast and Effective Stochastic Algorithm for Estimating Maximum-Likelihood Phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifinopoulos, J.; Nguyen, L.-T.; Von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. W-IQ-TREE: A fast online phylogenetic tool for maximum likelihood analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W232–W235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guindon, S.; Dufayard, J.-F.; Lefort, V.; Anisimova, M.; Hordijk, W.; Gascuel, O. New Algorithms and Methods to Estimate Maximum-Likelihood Phylogenies: Assessing the Performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 2010, 59, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoang, D.T.; Chernomor, O.; Von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q.; Vinh, L.S. UFBoot2: Improving the Ultrafast Bootstrap Approximation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyngwi, N.A.; Koijam, K.; Sharma, D.; Joshi, S.R. Cultivable bacterial diversity along the altitudinal zonation and vegetation range of tropical Eastern Himalaya. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2013, 61, 467–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viera, W.; Noboa, M.; Martínez, A.; Báez, F.; Jácome, R.; Medina, L.; Jackson, T. Trichoderma asperellum increases crop yield and fruit weight of blackberry (Rubus glaucus) under subtropical Andean conditions. Vegetos 2019, 32, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picone, R.; Pietramellara, G.; Guggenberger, G.; Pathan, S.I.; Gentsch, N. The contemporary plant-soil feedback in legume-cereal intercropping systems: A review of carbon, nutrient, and microbial dynamics. Plant Soil 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.T.; Supronienė, S.; Žvirdauskienė, R.; Aleinikovienė, J. Climate, soil, and microbes: Interactions shaping organic matter decomposition in croplands. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chutivisut, P.; Kotchaplai, P.; Faiyue, B.; Tuntiwiwattanapun, N. Exploring The Co-composting Potentials of Raw Grease Trap and Grease Trap-Derived Soaps: Insights into Grease Trap Modification, Calcium Supplementation, and Microbial Community Analysis. Appl. Environ. Res. 2025, 47, 010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, G.; Li, Y.; Wu, X.; Liang, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Q.; Peng, F. Isolation, Characterization and Growth-Promoting Properties of Phosphate-Solubilizing Bacteria (PSBs) Derived from Peach Tree Rhizosphere. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damo, J.L.C.; Pedro, M.; Sison, M.L. Phosphate solubilization and plant growth promotion by Enterobacter sp. isolate. Appl. Microbiol. 2024, 4, 1177–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ughamba, K.T.; Ndukwe, J.K.; Lidbury, I.D.; Nnaji, N.D.; Eze, C.N.; Aduba, C.C.; Groenhof, S.; Chukwu, K.O.; Anyanwu, C.U.; Nwaiwu, A.; et al. Trends in the application of phosphate-solubilizing microbes as biofertilizers: Implications for soil improvement. Soil Syst. 2025, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Diksha Sindhu, S.S.; Kumar, R. Harnessing phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms for mitigation of nutritional and environmental stresses, and sustainable crop production. Planta 2025, 261, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patani, A.; Patel, M.; Islam, S.; Yadav, V.K.; Prajapati, D.; Yadav, A.N.; Kumar Sahoo, D.; Patel, A. Recent advances in Bacillus-mediated plant growth enhancement: A paradigm shift in redefining crop resilience. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 40, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoshru, B.; Fallah Nosratabad, A.; Mahjenabadi, V.A.J.; Knežević, M.; Hinojosa, A.C.; Fadiji, A.E.; Enagbonma, B.J.; Qaderi, S.; Patel, M.; Eisa Mollaiy Baktash, E.M.; et al. Multidimensional role of Pseudomonas: From biofertilizers to bioremediation and soil ecology to sustainable agriculture. J. Plant Nutr. 2025, 48, 1016–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantigoso, H.A.; He, Y.; Manter, D.K.; Fonte, S.J.; Vivanco, J.M. Phosphorus-solubilizing bacteria isolated from the rhizosphere of wild potato Solanum bulbocastanum enhance growth of modern potato varieties. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2022, 46, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djuuna, I.A.F.; Prabawardani, S.; Massora, M. Population distribution of phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms in agricultural soil. Microbes Environ. 2022, 37, ME21041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, T.; Yasen, M.; Li, M.; Wang, J. Plant species and altitudinal gradients jointly shape rhizosphere bacterial community structure in mountain ecosystems. Rhizosphere 2025, 37, 101245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidbury, I.D.; Borsetto, C.; Murphy, A.R.; Bottrill, A.; Jones, A.M.; Bending, G.D.; Hammond, J.P.; Chen, Y.; Wellington, E.M.H.; Scanlan, D.J. Niche-adaptation in plant-associated Bacteroidetes favours specialisation in organic phosphorus mineralisation. ISME J. 2021, 15, 1040–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, J.F.; da Silva, M.S.; de Oliveira, N.F.; de Souza, C.R.; Arcenio, F.S.; de Lima, B.A.; Zonta, E. Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria from Tropical Soils: In Vitro Assessment of Functional Traits. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Liu, L.; Li, S.; Xie, J.; Xue, X.; Jiang, Y. Screening of phosphate-solubilizing bacteria and their abilities of phosphorus solubilization and wheat growth promotion. BMC Microbiol. 2022, 22, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Zhao, G.; Wei, Y.; Dong, Y.; Hou, L.; Jiao, R. Isolation and screening of multifunctional phosphate solubilizing bacteria and its growth-promoting effect on Chinese fir seedlings. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Locations | CFU per gram of Soil | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | Mean Rank | |

| Píllaro canton (Santa Rita) | 9.72 × 109 | 41.00 a |

| Quero canton (El Placer) | 5.66 × 106 | 27.44 b |

| Ambato canton (Llangahua) | 4.21 × 106 | 21.56 bc |

| Mocha canton (Pinguilí) | 2.06 × 106 | 17.17 c |

| Location | Isolates | Cultural Characteristics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elevation | Shape | Edge | Consistency | Texture | Bright | Color Pantone Code | ||

| Quero canton, El placer | CC-FCAGP-BSF1 | # | +++ | **** | S | L | b | 374 |

| Quero canton, El placer | CC-FCAGP-BSF2 | #### | + | * | S | L | s | 607 |

| Quero canton, El placer | CC-FCAGP-BSF3 | #### | + | * | M | L | b | 4525 |

| Quero canton, El placer | CC-FCAGP-BSF4 | #### | + | * | M | R | b | 4525 |

| Quero canton, El placer | CC-FCAGP-BSF5 | ## | +++ | R* | M | L | b | 4525 |

| Quero canton, El placer | CC-FCAGP-BSF6 | ### | + | * | S | L | s | 607 |

| Quero canton, El placer | CC-FCAGP-BSF7 | ### | + | * | S | L | s | 607 |

| Quero canton, El placer | CC-FCAGP-BSF8 | ### | +++ | R* | M | L | b | 698 |

| Mocha canton, Pinguilí | CC-FCAGP-BSF9 | #### | + | * | M | L | b | 607 |

| Mocha canton, Pinguilí | CC-FCAGP-BSF10 | ## | f+ | * | M | L | b | 4525 |

| Mocha canton, Pinguilí | CC-FCAGP-BSF11 | ### | f+ | * | S | L | b | 698 |

| Mocha canton, Pinguilí | CC-FCAGP-BSF12 | ## | f+ | * | S | L | b | 374 |

| Mocha canton, Pinguilí | CC-FCAGP-BSF13 | ### | f+ | * | S | L | b | 4525 |

| Mocha canton, Pinguilí | CC-FCAGP-BSF14 | ### | f+ | * | M | L | b | 4525 |

| Mocha canton, Pinguilí | CC-FCAGP-BSF15 | #### | + | * | S | L | b | 374 |

| Mocha canton, Pinguilí | CC-FCAGP-BSF16 | ## | + | * | M | L | b | 698 |

| Ambato canton, Llangahua | CC-FCAGP-BSF17 | ### | + | * | S | L | b | 374 |

| Ambato canton, Llangahua | CC-FCAGP-BSF18 | # | f+ | * | S | L | b | 102 |

| Ambato canton, Llangahua | CC-FCAGP-BSF19 | #### | + | * | S | L | b | 110 |

| Ambato canton, Llangahua | CC-FCAGP-BSF20 | # | + | * | S | L | b | 374 |

| Ambato canton, Llangahua | CC-FCAGP-BSF21 | ## | + | * | S | L | b | 607 |

| Ambato canton, Llangahua | CC-FCAGP-BSF22 | ## | + | * | S | L | b | 698 |

| Ambato canton, Llangahua | CC-FCAGP-BSF23 | # | + | * | S | L | b | 401 |

| Ambato canton, Llangahua | CC-FCAGP-BSF24 | ## | + | * | S | L | b | 600 |

| Ambato canton, Llangahua | CC-FCAGP-BSF25 | ## | + | * | S | L | b | 607 |

| Ambato canton, Llangahua | CC-FCAGP-BSF26 | # | + | * | S | L | b | 698 |

| Píllaro canton, Santa Rita | CC-FCAGP-BSF27 | # | + | * | S | L | b | 401 |

| Píllaro canton, Santa Rita | CC-FCAGP-BSF28 | # | + | * | S | L | b | 607 |

| Píllaro canton, Santa Rita | CC-FCAGP-BSF29 | ### | + | * | S | L | b | 401 |

| Píllaro canton, Santa Rita | CC-FCAGP-BSF30 | # | + | L* | S | R | b | 401 |

| Píllaro canton, Santa Rita | CC-FCAGP-BSF31 | ## | + | * | S | L | b | 600 |

| Píllaro canton, Santa Rita | CC-FCAGP-BSF32 | #### | f+ | * | S | L | b | 401 |

| Píllaro canton, Santa Rita | CC-FCAGP-BSF33 | ## | + | * | S | L | b | 600 |

| Píllaro canton, Santa Rita | CC-FCAGP-BSF34 | # | + | L* | S | R | b | 374 |

| Píllaro canton, Santa Rita | CC-FCAGP-BSF35 | # | + | * | S | L | b | 401 |

| Píllaro canton, Santa Rita | CC-FCAGP-BSF36 | # | +++ | L* | S | L | b | 401 |

| Location | Isolates | Morphological Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morphology | Grouping | Gram Reaction | ||

| Quero canton, El placer | CC-FCAGP-BSF1 | B | DB | (-) |

| Quero canton, El placer | CC-FCAGP-BSF2 | BL | EB | (-) |

| Quero canton, El placer | CC-FCAGP-BSF3 | BL | EMP | (-) |

| Quero canton, El placer | CC-FCAGP-BSF4 | B | DB | (-) |

| Quero canton, El placer | CC-FCAGP-BSF5 | C | SAR | (+) |

| Quero canton, El placer | CC-FCAGP-BSF6 | BL | DC | (+) |

| Quero canton, El placer | CC-FCAGP-BSF7 | C | DC | (+) |

| Quero canton, El placer | CC-FCAGP-BSF8 | B | EMP | (-) |

| Mocha canton, Pinguilí | CC-FCAGP BSF9 | B | DB | (-) |

| Mocha canton, Pinguilí | CC-FCAGP-BSF10 | B | DB | (-) |

| Mocha canton, Pinguilí | CC-FCAGP-BSF11 | BL | DB | (-) |

| Mocha canton, Pinguilí | CC-FCAGP-BSF12 | B | EMP | (-) |

| Mocha canton, Pinguilí | CC-FCAGP-BSF13 | B | DB | (-) |

| Mocha canton, Pinguilí | CC-FCAGP-BSF14 | B | EMP | (-) |

| Mocha canton, Pinguilí | CC-FCAGP-BSF15 | B | EMP | (-) |

| Mocha canton, Pinguilí | CC-FCAGP-BSF16 | B | DB | (-) |

| Ambato canton, Llangahua | CC-FCAGP-BSF17 | B | EB | (-) |

| Ambato canton, Llangahua | CC-FCAGP-BSF18 | B | EB | (-) |

| Ambato canton, Llangahua | CC-FCAGP-BSF19 | B | EMP | (-) |

| Ambato canton, Llangahua | CC-FCAGP-BSF20 | C | EMP | (-) |

| Ambato canton, Llangahua | CC-FCAGP-BSF21 | C | DC | (-) |

| Ambato canton, Llangahua | CC-FCAGP-BSF22 | B | DB | (-) |

| Ambato canton, Llangahua | CC-FCAGP-BSF23 | BC | DB | (-) |

| Ambato canton, Llangahua | CC-FCAGP-BSF24 | C | SAR | (+) |

| Ambato canton, Llangahua | CC-FCAGP-BSF25 | B | DB | (-) |

| Ambato canton, Llangahua | CC-FCAGP-BSF26 | C | EMP | (-) |

| Píllaro canton, Santa Rita | CC-FCAGP-BSF27 | B | DB | (-) |

| Píllaro canton, Santa Rita | CC-FCAGP-BSF28 | BC | DB | (-) |

| Píllaro canton, Santa Rita | CC-FCAGP-BSF29 | B | EMP | (+) |

| Píllaro canton, Santa Rita | CC-FCAGP-BSF30 | B | DB | (-) |

| Píllaro canton, Santa Rita | CC-FCAGP-BSF31 | BC | EMP | (-) |

| Píllaro canton, Santa Rita | CC-FCAGP-BSF32 | C | DC | (+) |

| Píllaro canton, Santa Rita | CC-FCAGP-BSF33 | BC | DB | (-) |

| Píllaro canton, Santa Rita | CC-FCAGP-BSF34 | BC | DB | (-) |

| Píllaro canton, Santa Rita | CC-FCAGP-BSF35 | BC | DB | (-) |

| Píllaro canton, Santa Rita | CC-FCAGP-BSF36 | BC | DB | (-) |

| Isolates | Phosphate Solubilization Capacity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solubilization Halos (mm) | Phosphate Solubilization Index | |||

| Mean Rank | Mean Rank | |||

| CC-FCAGP-BSF6 | 8.39 | 188.90 a | 3.79 | 188.90 a |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF8 | 8.36 | 186.40 ab | 3.79 | 186.10 ab |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF16 | 8.30 | 185.60 ab | 3.77 | 185.70 ab |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF9 | 8.09 | 185.10 ab | 3.70 | 185.00 ab |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF11 | 7.86 | 178.00 abc | 3.62 | 177.80 abc |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF10 | 7.55 | 168.20 abc | 3.52 | 168.30 abc |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF27 | 7.41 | 167.80 abc | 3.47 | 168.00 abc |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF14 | 7.35 | 165.60 bc | 3.45 | 166.20 bc |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF7 | 7.45 | 164.30 c | 3.47 | 164.10 c |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF22 | 7.25 | 162.70 c | 3.42 | 162.50 c |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF24 | 6.01 | 142.80 d | 3.00 | 142.80 d |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF33 | 5.89 | 140.60 d | 2.96 | 140.30 d |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF31 | 5.73 | 132.30 d | 2.91 | 132.40 d |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF15 | 5.60 | 130.40 d | 2.87 | 130.60 d |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF35 | 5.39 | 126.10 e | 2.79 | 125.90 e |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF25 | 5.52 | 122.70 e | 2.84 | 122.90 e |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF19 | 5.21 | 119.00 e | 2.74 | 118.90 e |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF21 | 5.05 | 110.80 e | 2.68 | 110.80 e |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF29 | 4.99 | 108.70 e | 2.66 | 108.30 e |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF12 | 4.79 | 101.90 e | 2.60 | 102.40 e |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF34 | 4.77 | 99.60 e | 2.59 | 99.40 e |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF17 | 4.52 | 98.50 ef | 2.51 | 99.40 e |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF13 | 4.06 | 82.20 fg | 2.35 | 82.30 fg |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF5 | 4.04 | 82.10 fg | 2.35 | 82.10 fg |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF20 | 3.86 | 78.80 fg | 2.29 | 78.80 fg |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF28 | 3.77 | 75.60 fg | 2.25 | 75.60 fg |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF4 | 3.75 | 74.80 fg | 2.25 | 75.10 fg |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF36 | 3.32 | 65.20 fg | 2.10 | 64.90 fg |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF2 | 2.69 | 49.30 gh | 1.90 | 49.10 gh |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF30 | 2.39 | 42.20 h | 1.80 | 42.20 h |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF18 | 2.33 | 41.50 h | 1.78 | 41.60 h |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF23 | 2.28 | 39.40 h | 1.76 | 39.30 h |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF3 | 2.16 | 36.80 h | 1.72 | 36.70 h |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF32 | 1.52 | 13.10 jk | 1.51 | 13.20 jk |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF1 | 1.35 | 9.40 kl | 1.45 | 9.30 kl |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF26 | 1.11 | 3.60 l | 1.37 | 3.50 l |

| Isolates | Amplicon (bp) | Max Score | Most Related Species | Similarity (%) | Accession Number | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC-FCAGP-BSF6 | 1346 | 2428 | Bacillus thuringiensis | 100 | OQ581511.1 | Direct Submission |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF8 | 964 | 1739 | Bacillus sp. | 100 | OK663528.1 | Direct Submission |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF16 | 521 | 936 | Bacillus cereus | 99.81 | MF360033.1 | Direct Submission |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF9 | 1213 | 2177 | Pseudomonas sp. | 99.84 | JN975934.1 | Lyngwi et al. [33] |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF11 | 1188 | 2346 | Lysinibacillus macroides | 99.62 | MN538923.1 | Direct Submission |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF10 | 1058 | 1909 | Pseudomonas sp. | 100 | PP259448.1 | Direct Submission |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF27 | 980 | 1768 | Paenibacillus shunpengii | 100 | MT225642.1 | Direct Submission |

| Isolates | Leaf Area (dm2) | Fresh Mass (g) | Dry Mass (g) | Leaf Area Index | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Rank | Mean Rank | Mean Rank | Mean Rank | |||||

| CC-FCAGP-BSF27 | 0.262 | 30.10 b | 0.23 | 23.70 cd | 0.036 | 23.50 d | 0.170 | 29.60 b |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF16 | 0.281 | 32.70 b | 0.27 | 28.30 c | 0.037 | 25.50 d | 0.190 | 32.10 b |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF11 | 0.283 | 31.60 b | 0.32 | 32.40 bc | 0.041 | 32.00 bc | 0.190 | 31.80 b |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF10 | 0.322 | 36.20 ab | 0.36 | 36.30 b | 0.056 | 37.00 b | 0.210 | 36.30 ab |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF9 | 0.364 | 39.50 ab | 0.46 | 45.30 a | 0.063 | 42.00 ab | 0.240 | 40.00 a |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF8 | 0.427 | 40.10 a | 0.66 | 47.90 a | 0.092 | 48.20 a | 0.280 | 40.10 a |

| CC-FCAGP-BSF6 | 0.492 | 45.10 a | 0.87 | 50.80 a | 0.096 | 51.00 a | 0.330 | 45.50 a |

| Control | 0.029 | 3.10 d | 0.09 | 3.00 f | 0.037 | 12.80 fg | 0.020 | 3.20 d |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Leiva-Mora, M.; Mera Guzmán, P.E.; Mera-Andrade, R.I.; Zabala Haro, A.M.; Saa, L.R.; Loján, P.; Silva Agurto, C.L.; Salazar-Garcés, L.F.; González Osorio, B.B.; Cabrera Mederos, D.; et al. Isolation and Characterization of Phosphate-Solubilizing Rhizobacteria from Solanum tuberosum with Plant Growth-Promoting Activity. Appl. Microbiol. 2026, 6, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol6010008

Leiva-Mora M, Mera Guzmán PE, Mera-Andrade RI, Zabala Haro AM, Saa LR, Loján P, Silva Agurto CL, Salazar-Garcés LF, González Osorio BB, Cabrera Mederos D, et al. Isolation and Characterization of Phosphate-Solubilizing Rhizobacteria from Solanum tuberosum with Plant Growth-Promoting Activity. Applied Microbiology. 2026; 6(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol6010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeiva-Mora, Michel, Pamela Elizabeth Mera Guzmán, Rafael Isaías Mera-Andrade, Alicia Monserrath Zabala Haro, Luis Rodrigo Saa, Paúl Loján, Catherine Lizzeth Silva Agurto, Luis Fabián Salazar-Garcés, Betty Beatriz González Osorio, Dariel Cabrera Mederos, and et al. 2026. "Isolation and Characterization of Phosphate-Solubilizing Rhizobacteria from Solanum tuberosum with Plant Growth-Promoting Activity" Applied Microbiology 6, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol6010008

APA StyleLeiva-Mora, M., Mera Guzmán, P. E., Mera-Andrade, R. I., Zabala Haro, A. M., Saa, L. R., Loján, P., Silva Agurto, C. L., Salazar-Garcés, L. F., González Osorio, B. B., Cabrera Mederos, D., & Portal, O. (2026). Isolation and Characterization of Phosphate-Solubilizing Rhizobacteria from Solanum tuberosum with Plant Growth-Promoting Activity. Applied Microbiology, 6(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmicrobiol6010008