Abstract

Drought significantly reduces global crop yields and agricultural productivity. This study aims to isolate drought-tolerant PGPR strains and evaluate their effects, both individually and in combination with salicylic acid (SA), on cowpea plants growth, physiological traits, antioxidant enzymes, and mineral content under both drought stress and non-stress conditions. Among fifteen bacterial isolates, AO7, identified as Streptomyces diastaticus subsp. ardesiacus PX459854 through 16S rRNA sequencing, demonstrated significant plant growth promotion in cowpea under gnotobiotic conditions. On the other hand, varying salicylic acid concentrations (0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 mM) was exposed to assess the plant growth of cowpea plants in a gnotobiotic system. A pot experiment in 2023 used a split-plot design with treatments for irrigation (unstressed and stressed) and different soaking treatments (control, S. diastaticus, salicylic acid (2 mM), and a combination). After 60 days, the combination treatment enhanced growth metrics, outpacing the control under stress. The microbial community in the T4 treatment exhibited the highest counts, while T8 (combination, stressed) showed lower counts but the highest chlorophyll content at 6.32 mg g−1 FW. Notable increases in proline and significant changes in enzyme activities (PO, PPO, CAT, and APX) were observed, particularly in treatment T8 under stress, indicating a positive response to both treatments. Mineral content of cowpea leaves varied with soaking treatments of S. diastaticus and SA (2.0%) especially under drought stress which the highest values were 1.72% N, 0.16% P, and 2.66% K with treatment T8. Therefore, T8 (combination, stressed) > T6 (S. diastaticus, stressed) > T7 (salicylic acid, stressed) > T5 (control, stressed) for different applications under stressed conditions and T4 (combination, unstressed) > T2 (S. diastaticus, unstressed) > T3 (salicylic acid, unstressed) > T1 (control, unstressed) for the other applications under normal conditions. Thus, using S. diastaticus and SA (2.0%) in combination greatly enhanced the growth dynamics of cowpea plants under drought stress conditions.

1. Introduction

Globally, agriculture has been severely impacted by the consequences of climate change. Food security in underdeveloped nations is at risk due to climate change [1]. Numerous biotic (i.e., phytopathogens) and abiotic (i.e., drought, salt, heavy metals, and severe temperatures) stresses coincide more quickly as a result of global climate change. The ecosystem has suffered as a result of agriculture’s reliance on chemical pesticides and fertilizers [2]. One of the main ecological restrictions on plant growth and productivity is drought stress. Water scarcity is the primary driver of functional and chemical variations in plants, and it has the most effect on agricultural productivity [3,4]. Water stress lowers nutrient intake, which results in stomata closure, poor root growth, decreased transpiration and photosynthetic rates, and dehydration, all of which cause plants to wilt. Each crop reacts differently to drought stress, and crop plants need various amounts of water at different stages of growth and development [5,6].

Because of its flexibility, nutritional value, and capacity to enhance soil fertility through biological nitrogen fixation, cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L.) is a significant legume crop that is extensively grown in arid and semi-arid countries [7]. However, by restricting water uptake, reducing leaf area, and hindering photosynthesis, drought stress drastically lowers its productivity. Even while cowpea plants build up osmolytes and activate antioxidant defenses when there is a water deficit, extended drought still results in decreased biomass and grain output. Therefore, increasing cowpea’s resistance to drought is crucial to maintaining production in arid regions [8,9,10]. Depending on the genotype, the severity, and the timing of the stress, the drop in cowpea yield caused by drought stress varies greatly. Although cowpea is typically thought to be drought-tolerant, genotypes that are sensitive can suffer large production losses, frequently surpassing 50% [11].

Based on what has been mentioned, there are some workable ways to lessen this detrimental impact on cowpea plant output, such as chemical and biological techniques [12]. By sustaining plant growth and absorption and boosting the rhizospheric soil’s potency, plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) play a critical role in the afforestation and restoration of arid regions [13,14]. PGPR inoculation can help plants deal with drought stress by lengthening roots, which allows roots to reach the deeper layer of soil to obtain moisture, in addition to preserving the level of phytohormones in plants, which either produce or break down plant hormones or positively alter their synthesis and signaling pathways [15,16]. Additionally, these bacteria are capable of producing soluble iron compounds (siderophore), fixing atmospheric nitrogen, synthesizing antibiotics, and solubilizing inorganic phosphates [17]. Additionally, they are capable of producing the phytohormones gibberellins (GA), cytokinins, 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC), and indole-acetic acid (IAA) [18,19]. Isolated PGPB has been successfully applied to reduce drought stress in plants, according to several research [20,21]. Nevertheless, the majority of these investigations have focused on specific bacterial species, primarily Bacillus and Pseudomonas. Over the years, there has been very little focus on using actinomycetes species to improve plants’ ability to withstand stress. Actinomycetes, which are primarily found in soils, are well known for producing bioactive secondary metabolites and antibiotics as well as for their exceptional capacity to endure in harsh conditions [22,23].

One important growth regulator that increases plant resistance to a variety of biotic and abiotic stressors is salicylic acid (SA). Ion uptake, plant growth, and mineral movement all depend on it [24]. During drought stress, salicylic acid is observed to activate biological and chemical processes linked to crop plants’ tolerance mechanisms. It has been confirmed that SA is a multidirectional plant hormone that lessens drought-related damage to plants [25]. Through its influence on a variety of physiological and biochemical processes, SA is a promising molecule that can give plants drought tolerance [26]. In plants under various conditions, it functions as a stress-signal molecule that triggers the expression of biosynthetic enzymes and proteins as well as abiotic stress-responsive genes.

According to recent research, salicylic acid administration, rhizobacterial inoculation, and physiological priming can all improve growth, preserve hydration status, and safeguard metabolic systems under stress. In areas where water shortage is becoming worse, these strategies help to stabilize productivity and encourage sustainable farming. According to Azmat et al. [27], wheat in water-deficient circumstances could benefit from the integrative application of PGPR and SA. Significant increases in shoot and root biomass, photosynthetic pigments, and leaf sugar levels were the outcomes of the dual treatment. By reducing oxidative stress markers like proline and malondialdehyde (MDA), which indicate improved membrane integrity and cellular protection, it safeguarded metabolic activities.

According to Ali et al. [28], using SA and PGPR together greatly increased maize seedlings’ resistance to salt stress. When compared to untreated stressed plants, the combined treatment was superior, resulting in a 32% rise in relative water content and notable gains in shoot and root dry weights (41% and 56%, respectively). By regulating antioxidant enzymes (such as catalase and ascorbate peroxidase) and lowering oxidative damage, this strategy actively safeguarded metabolic processes. The potential for drought tolerance in cowpea under water-deficient conditions was thought to be enhanced by PGPR and SA. Thus, the purpose of this study was to isolate and identify drought-tolerant PGPR strain (Streptomyces diastaticus) from drought-prone areas and assess their individual and combined effects with salicylic acid on the growth, soil population activity, physiological characteristics, antioxidant enzymes, and mineral content of drought-stressed cowpea during the 2023 season.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation of Drought Tolerant Rhizobacteria

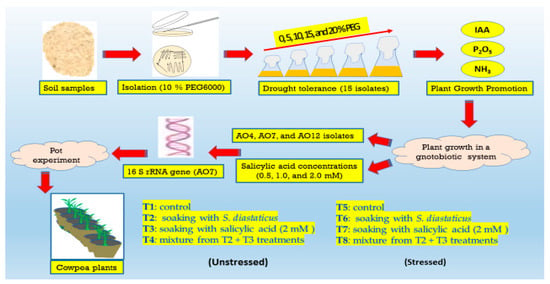

The rhizosphere of wheat growing in several parts of the western region of El-Minia (28°24′01″ N and 29°59′27″ E), Egypt was shown to have drought-tolerant rhizobacteria. Samples were taken from rhizospheric soil located in an area with limited precipitation and transported to the lab in sealed plastic bags. In less than a day, soil samples were treated by serially diluting them in distilled water that had been sterilized. Five grams of the sample were put into a glass bottle with 45 milliliters of sterile distilled water, and it was shaken at 150 rpm for 30 min. By plating 0.1 mL of soil dilutions (10−5) on nutrient agar medium (NAM) supplemented with 10% Polyethylene Glycol (PEG6000, Merck, Germany), drought-tolerant bacteria were identified [29]. After three days, fifteen bacterial isolates (AO1–AO15) were selected after incubated at 30 °C and thought to be drought-tolerant which kept a glycerol stock at −80 °C and cataloged each strain. A detailed diagram illustrating the different steps of the work (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A detailed diagram illustrating the different steps of the work.

2.2. Drought Tolerance Assessment of Chosen Isolates

Elevated drought concentrations (0, 5, 10, 15, and 20%) were added to a freshly made nutrient broth (NB) medium in order to ascertain the isolates maximal tolerance threshold. PEG6000 was used to prepare drought concentrations. Serial dilutions were performed by adding 0.5 mL of each dilution to petri dishes, adding the nutrient agar medium, and then carefully shaking the petri dishes to count the number of living cells. After three days of incubation at 30 °C, the CFU was calculated and given as a Log10 value [30]. The three bacterial isolates AO4, AO7, and AO12 that demonstrated the greatest drought resistance were chosen for additional analysis, including gnotobiotic sand systems and features that promote plant growth.

2.3. Plant Growth Promotion Traits

Three characteristics of plant growth promotion were examined under drought stress circumstances at 0, 5, 10, 15, and 20% of PEG6000: IAA production was determined by using the test method outlined by [31], which calculated and expressed as µg mL−1, inorganic phosphate solubilization was determined by [32], which calculated and expressed as µg P2O5 mL−1, and ammonia production was determined by [33], which calculated and expressed as µg mL−1. Every experiment was carried out at least three times and in triplicate.

2.4. Plant Growth in a Gnotobiotic System

According to Simons et al. [34], the impact of cowpea (Kafrelsheikh 1) growth and root colonization by soaking with AO4, AO7, and AO12 isolates and varying salicylic acid concentrations (0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 mM) was exposed to tested PEG levels in glass tubes (2.5 cm in diameter, 20 cm in length), with 8 replicates. Each tube received sixty grams of a sterile blend of nutritional solution [35]. One seed was planted into sterile tubes after sterilized seeds were immersed in various isolates (AO4, AO7, and AO12) and salicylic acid concentrations (0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 mM) for ninety minutes [36]. Control seeds were steeped in distilled water. All tubes were grown in a growth cabinet with a photoperiod of 16:8 h at 20 °C. An electronic balance (ADAM model PW 214, 500 g, UK) was used to quantify the fresh and dry weight of the plants after a month, however [37], calculated the relative water content (%) = FW − DW/TW − DW × 100. Additionally, three randomly selected plants from each treatment were used to measure root colonization. The roots were then completely cleaned to remove any remaining soil, weighed, and placed in a test tube with nine milliliters of sterile saline solution (0.85% NaCl), shaken on a vortex every ten minutes for one hour. After serial dilutions, 0.1 mL of each diluent was spread out on NA plates and incubated for 48 h at 30 °C. The best isolate and concentration of SA were then selected for additional research after the number of viable cells was counted and computed as CFU g−1 root [38].

2.5. Morphological, Physio-Biochemical and Molecular Identification of the Selected Isolate

Several morphological, physiological, and biochemical tests were used to confirm one of these isolates using the methods described in Bergey’s Manual of Determinative Bacteriology by [39]. Additionally, the GeneJet Bacterial Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (Fermentas) was used to extract the genomic DNA of the test bacterial isolates cultivated on NB. The isolate’s 16 S rRNA gene was amplified at Sigma Scientific Services Co., Giza, Egypt, using universal primers and the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The PCR products were forwarded to GATC Biotech DNA Sequencing (Germany) for sequencing using an ABI 3730xl DNA Sequencer. The neighbor-joining approach was used to create a dendrogram. Additionally, tree topology confidence was assessed. From here on, Streptomyces diastaticus AO7 will be referred to by the GenBank accession number OQ254782.

2.6. Pot Experiment

The experiment was carried out in a split-plot design in the summer of 2023 in a greenhouse of the Bacteriology Laboratory, Sakha Agricultural Research Station, Kafr El-Sheikh, Egypt. The main plot consisted of two treatments (irrigation stressed and unstressed), while the subplot was consistent from eight treatments: T1: control (unstressed), T2: soaking with S. diastaticus (1 × 109 CFU mL−1 for 90 min, unstressed), T3: soaking with salicylic acid (2 mM for 90 min, unstressed), T4: mixture from T2 + T3 treatments (1:1), unstressed), T5: control (stressed), T6: soaking with S. diastaticus (1 × 109 CFU mL−1 for 90 min, stressed), T7: soaking with salicylic acid (2 mM for 90 min, stressed), T8: mixture from T6 + T7 treatments (1:1), stressed). Cowpea seeds (Kafrelsheikh, obtained from HRI, ARC, Egypt and previously disinfected with 70% (v/v) ethanol and 3% (v/v) sodium hypochlorite) were planted in 40 plastic pots (8 kg) filled with loamy soil at a rate of two seeds per pot. The soil used has the following physicochemical characteristics: pH 7.36; EC 2.79 dSm−1; organic matter (%) 1.24; available N (mg Kg−1) 16.35; available P (mg Kg−1) 9.55; and available K (mg Kg−1) 311.13. For six weeks, the pots were kept in a growing greenhouse with a temperature of 30 °C, a 16-h light/8-h dark cycle, and watering every two to three days. The pots were split into two groups after six weeks. The first group (unstressed, 20 pots) continued to get water, while the second group (stressed, 20 pots) experienced drought stress by not receiving water for three weeks in a row. After eight weeks after planting, various criteria were identified.

2.7. Measurements

2.7.1. Vegetative and Physiological Parameters

Three healthy plants per treatment were used to measure the fresh and dry mass (g plant−1), shoot length, and root length (cm plant−1) for vegetative growth. A leaf sample from each treatment was frozen in order to measure photosynthetic pigments, total soluble sugars (TSS), and antioxidant enzymes using a UV spectrophotometer (Model 6705). Total chlorophyll and carotenoids, were reported as mg g−1 FW and µg g−1 FW, respectively [40], while TSS was measured as µg g−1 FW according to Hendrix [41]. Additionally, according to Bates et al. [42], proline parameter was determined which calculated and expressed as µmol g−1 FW.

2.7.2. Soil Community

Ten grams of soil samples (rhizosphere) were put to a glass tube containing 90 mL of sterile dH2O, and the mixture was agitated for 30 min at 150 rpm. Allen [43], states that soil extract agar medium was used to estimate the total count of bacteria (CFU log 10 g−1 dry soil), Martin’s medium was used to estimate the total count of fungus (CFU log 10 g−1 dry soil), and Jensen’s medium was used to estimate the total count of actinomycetes (CFU log 10 g−1 dry soil).

2.7.3. Antioxidant Enzymes

According to Srivastava [44], peroxidase (POX) enzyme was determined by oxidizing pyrogallol to purpurgallin with H2O2 at 425 nm, which expressed as μM H2O2 g−1 FW min−1, and polyphenol oxidase enzyme (PPO) was measured at 495 nm, which expressed as μM tetra-guaiacol g−1 min−1 FW [45]. Also, catalase (CAT) enzyme was determined at 240 nm for three minutes and expressed as Unit mg−1 protein [46], while to calculate ascorbate peroxidase (APX), the activity was determined for three min at 290 nm and expressed as Unit mg−1 protein [47].

2.7.4. N, P and K in Leaves

Samples that had been dried for three days at 65 °C were ground into a uniform powder (IKa-Werke, M 20 Darmstadt, Germany). According to Page et al. [48], N (%) was determined using the Micro-Kjeldahl method, whereas P and K% were determined using spectrophotometers and the atomic absorption spectrometry method, respectively [49,50].

2.8. Statistical Analyses

SPSS software (version 20; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used to do a variance analysis on the data. Duncan’s multiple range testing method was used to examine the mean separations, and significance was determined at p ≤ 0.05 [51].

3. Results

3.1. Isolation and Purification of Drought Tolerance Bacteria

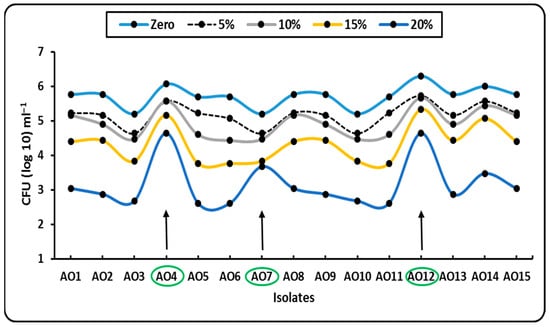

Fifteen bacterial isolates, labeled AO1–AO15, were isolated in soil samples from the western region of El-Minia, which is thought to be one of the most promising for agriculture despite long-term water stress and possible desertification. To assess their tolerance, all isolates were cultivated on nutrient broth and/or nutritional agar medium that had been supplemented with higher doses of PEG6000 (0, 5, 10, 15, and 20%). While all isolates showed some tolerance to PEG, only three isolates (AO4, AO7, and AO12) showed the maximum tolerance, with counts of 4.63, 3.67, and 4.63 CFU (log10 mL−1) at the highest concentrations of PEG (20%) using the plate count technique after 72 h, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Growth pattern (Log number, CFU ml−1) of different isolates (AO1–AO15) in presence of different concentrations (0, 5, 10, 15 and 20%) of PEG6000 on NB medium.

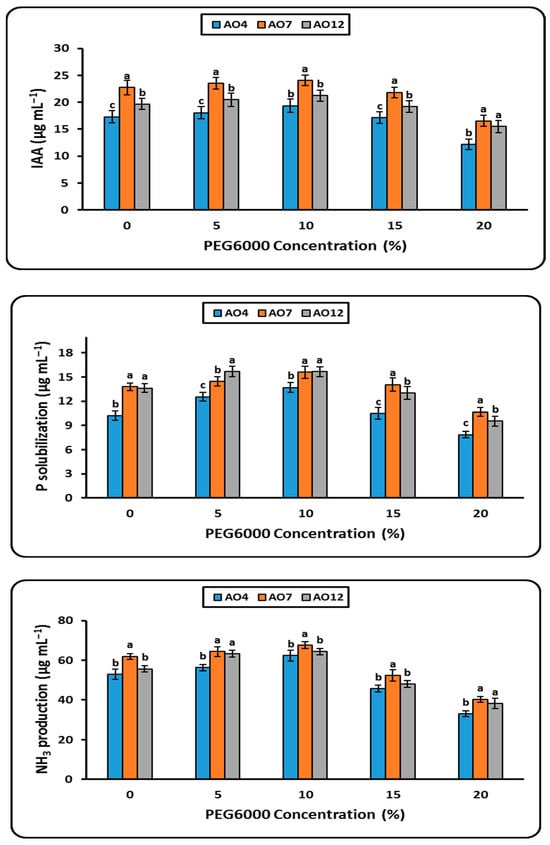

3.2. Plant Growth Promotion Traits

Three bacterial isolates, AO4, AO7, and AO12, were chosen for further evaluation of their plant growth-promoting characteristics, such as IAA, P solubilization, and NH3, under varying concentrations of PEG6000 (0, 5, 10, 15, and 20%) (Figure 3). Growing on higher PEG concentrations up to 20% reduced the IAA generation of the three isolates that were chosen in comparison to the control (zero PEG). Among the investigated bacterial isolates, isolate (AO7) produced the most IAA (16.56 μg mL−1), both in the control and at the highest PEG (20%). In the growing medium supplemented with 20% PEG, the tested isolates shown a significant capacity to solubilize phosphate, measuring 7.86, 10.67, and 9.53 μg mL−1, respectively (Figure 3). When PEG concentration rose to 20% in the growing medium, the three bacterial isolates that were chosen produced slightly less ammonia than the control group (Figure 3). As a result, the tested isolates outcomes at the highest PEG concentrations (20%) were as follows: AO7 (40.33 μg mL−1) > AO12 (38.31 μg mL−1) > AO4 (33.00 μg mL−1).

Figure 3.

Plant growth traits (IAA, P solublilization, NH3 production) of different isolates (AO4, AO7 and AO12) to tolerance different levels of PEG6000 (0, 5, 10, 15 and 20%) on NB medium. Using DMRT (5%), the means that are followed by a common letter do not differ substantially. Values are mean following the SD of three replicates.

3.3. Plant Growth in a Gnotobiotic Nutrient Solution System (Soaking in Bacterial Isolates)

Table 1 displays the reaction of PEG-affected cowpea plants to a gnotobiotic system soaking with isolates that promote plant growth. When PEG concentration rose to 20% in the growth medium as opposed to 0% under inoculation with AO4, AO7, and AO12 isolates, cowpea plant fresh weight, dry weight, root colonization, and RWC generally increased modestly. AO4 (3.53 g plant−1), AO7 (3.40 g plant−1), and AO12 (3.10 g plant−1) showed the greatest improvement in fresh weight among the various examined isolates. The dry weight parameter showed the similar pattern, with cowpea plants grown with the greatest proportion of PEG (15%) having the highest recorded value when compared to the control (Table 1). Conversely, examined isolates (AO4, AO7, and AO12) showed a positive response to soaking cowpea seeds, recording higher and significant values for root colonization as compared to the control. Under 20% PEG6000, cowpea treated with bacteria had root colonization of 26.33 CFU × 105 g−1 for the AO4 isolate, 23.00 CFU × 105 g−1 for the AO7 isolate, and 23.00 CFU × 105 g−1 for the AO12 isolate. Additionally, in comparison to other studied bacteria and the control treatment, the application of a mixture (soaking with AO7 + 20% PEG 6000) enhanced the RWC of cowpea by 84.57% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effect of soaking with tested bacterial isolates on fresh weight, dry weight, root colonization and RWC of cowpea plants under different levels of PEG6000 after 30 days from sowing.

3.4. Plant Growth in a Gnotobiotic Nutrient Solution System (Soaking in Different Levels in SA)

Table 2 displays the reaction of cowpea plants impacted by PEG to soaking in varying concentrations of SA (0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 mM) in a gnotobiotic setting. Fresh weight, dry weight, root colonization, and RWC of cowpea plants were generally somewhat higher when PEG content rose to 20% in the growth medium as opposed to 0% while soaking with varying concentrations of SA (0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 mM). Among the various SA concentrations, fresh weight significantly improved with 2.0 mM of SA (3.07 g plant−1), 1.0 mM of SA (2.70 g plant−1), and 5.0 mM of SA (2.60 g plant−1), in that order. The dry weight parameter showed the similar pattern, with cowpea plants grown with the greatest proportion of PEG (20%) having the highest recorded value when compared to the control (Table 2). Conversely, a favorable reaction to soaking cowpea seeds in several concentrations of SA (0.5, 1.0, and 2 mM) resulted in higher and significant RWC values when compared to the control. In comparison to the other tested PEG, treated cowpea with SA had RWC of 85.12%, 83.14%, and 82.14% for 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 mM of SA concentrations under 20% of PEG, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of soaking with different levels of SA on fresh weight, dry weight, root colonization and RWC of cowpea plants under different levels of PEG6000 after 30 days from sowing.

3.5. Morphological, Biochemical Characteristics and Molecular Identification of the Selected Isolate

According to the Key of [52], and Bergey’s Manual [53], AO7 was selected among the investigated isolates based on their tolerance, production of plant growth promotion, and plant growth in a gnotobiotic system under various levels of PEG6000. The following tests are used to determine that the isolate belongs to the genus Streptomyces sp. based on their morphological and biochemical characteristics: gram test (+); catalase test (+); casein hydrolysis test (+); starch degradation (+); nitrate reduction (+); H2S production (−); acid production from sugars: sucrose (+); glucose (+); xylose (+); mannitol (+); fructose (+); rhamnose (−); aerial mass color is gray; cell form is filamentous; growth at 20 °C (+) and 50 °C (−) temperatures. Additionally, it was able to grow at a NaCl concentration of 4%, but not at or above 6%.

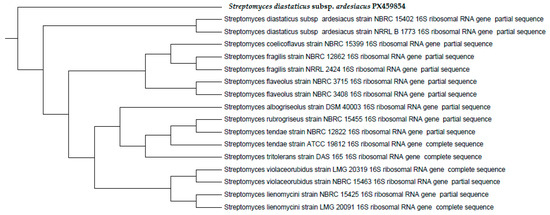

The database in Figure 4 demonstrated 98% gene sequence similarity between the Streptomyces diastaticus subsp. ardesiacus strain NRRL B-1773 16S ribosomal RNA gene and (AO7) for genetic identification. The RDP and GenBank databases provided the sequences used in the phylogenetic study. The neighbor-joining approach was used to create a dendrogram. Additionally, tree topology confidence was assessed. From here on, Streptomyces diastaticus AO7 will be referred to by the GenBank accession number PX459854 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic tree created using a 1.5 kpb 16 S rRNA gene sequence of Streptomyces diastaticus subsp. ardesiacus PX459854.

3.6. Pot Experiment

3.6.1. Growth Characteristics

Cowpea was used as a model crop in a greenhouse pot experiment to find the best soaking with inoculation by S. diastaticus and SA. Significant variations in the growth traits of cowpea plants under various treatments were observed after 60 days of seeding. These parameters i.e., fresh and dry weight, shoot and root length are listed in Table 3. Overall, the combination treatment (T4, soaking with S. diastaticus (AO7) and SA (2.0%)) outperformed the control treatment in terms of growth parameters. In contrast to T5 treatment (control + stressed conditions), which achieved 36.21 and 6.82, cowpea plants treated with T8 (soaking with S. diastaticus (AO7) and SA (2.0%) + stressed conditions) significantly increased the fresh and dry weight (g plant−1), 84.93 and 15.63, as shown in Table 3. The shoot and root length (cm plant−1) parameters were found to be 25.33 and 12.11 for the T8 treatment (soaking with S. diastaticus (AO7) and SA (2.0%)), 21.02 and 9.99 for the T6 treatment (soaking with S. diastaticus), 17.26 and 8.47 for the T7 treatment (soaking with SA (2.0%)), and 16.56 and 7.87 for the T5 treatment (control) under stressful conditions (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of soaking with S. diastaticus (AO7) and SA (2.0%) on growth characteristics of cowpea plants under stressed and unstressed of drought after 60 days from sowing.

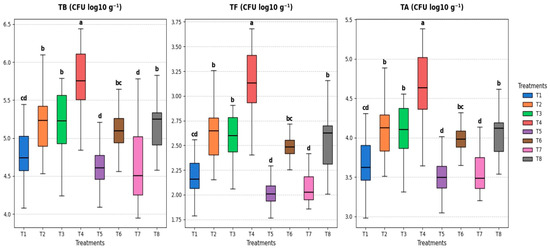

3.6.2. Soil Community

The microbial community, which comprises the total number of bacteria, actinomycetes, and fungi in the rhizosphere of cowpea plants grown under various soaking treatments with S. diastaticus and SA in both stressed and unstressed conditions, was found to differ significantly (p ≤ 0.05) after 60 days of sowing (Figure 5). When compared to the other treatments, the T4 treatment (combination + unstressed) showed the highest population of total counts of bacteria (5.74 CFU log10 g−1), actinomycetes (4.62 CFU log10 g−1), and fungi (3.12 CFU log10 g−1). In contrast, the T8 treatment (combination + stressed) recorded 5.16 CFU log10 g−1 for total counts of bacteria, 4.04 CFU log10 g−1 for actinomycetes, and 2.54 CFU log10 g−1 for fungi (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effect of soaking with S. diastaticus (AO7) and SA (2.0%) on the rhizosphere microbial community of cowpea plants under stressed and unstressed of drought after 60 days from sowing. T1: control, T2: soaking with S. diastaticus, T3: soaking with salicylic acid, T4: mixture from T2 + T3 treatments (1:1); T1–T4: unstressed; T5–T8: stressed. TB: total count of bacteria; TF: total count of fungi; TA: total count of actinomycetes. Using DMRT (5%), the means that are followed by a common letter do not differ substantially. Values are mean following the SD of three replicates.

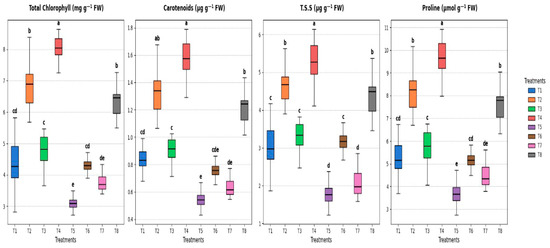

3.6.3. Physiological Characteristics

The levels of total chlorophyll, carotenoids, total soluble sugar, and proline in cowpea leaves after 60 days of planting varied significantly (p ≤ 0.05) depending on the soaking with S. diastaticus and SA (Figure 6). The highest total chlorophyll values were 6.32 mg g−1 FW for the T8 treatment (soaking with S. diastaticus + soaking with salicylic acid), followed by 4.31 mg g−1 FW for the T6 treatment (soaking with S. diastaticus) over the control treatment (T5), and 3.11 mg g−1 FW under stress. In comparison to T1 treatment (control), which obtained 0.85 and 3.13 µg g−1 FW, respectively, T4 treatment showed the highest values for carotenoids and TSS, 1.57 and 5.25 µg g−1 FW (Figure 6). Furthermore, the proline (µmole g−1 FW) parameter revealed that, in contrast to unstressed treatments, the T8 treatment recorded 7.59, followed by 5.17 for the T6 treatment and 4.54 for the T57 treatment, while the control treatment (T5) recorded 3.73 (Figure 6). Therefore, T8 > T6 > T7 > T5 for different applications under strained conditions and T4 > T2 > T3 > T1 for the other applications under unstressed conditions, according to the previously mentioned data.

Figure 6.

Effect of soaking with S. diastaticus (AO7) and SA (2.0%) on the physiological characteristics of cowpea plants under stressed and unstressed of drought after 60 days from sowing. T1: control, T2: soaking with S. diastaticus, T3: soaking with salicylic acid, T4: mixture from T2 + T3 treatments (1:1); T1–T4: unstressed; T5–T8: stressed. Using DMRT (5%), the means that are followed by a common letter do not differ substantially. Values are mean following the SD of three replicates.

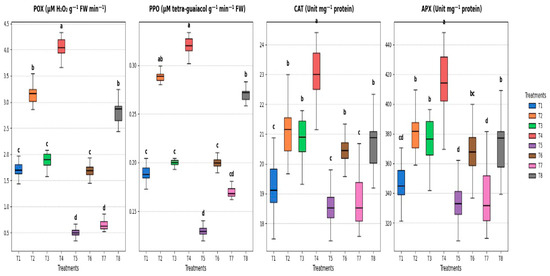

3.6.4. Antioxidant Enzymes

According to the data presented in Figure 7, cowpea plants that received various soaking treatments with S. diastaticus and SA under both stressed and unstressed conditions showed an increase in the activity of the antioxidant enzymes POX, PPO, CAT, and APX sixty days after planting. Figure 7 shows that under stressful conditions, the highest levels of PO activity (μM H2O2 g−1 FW min−1) in the soaking seeds increased dramatically from 0.51 (control, T5) to 2.81 (T8). Furthermore, the PPO enzyme activity (μM tetra–guaiacol g−1 min−1 FW) increased when seeds were soaked in the investigated treatments, recording higher values than the control, which changed from 0.19 (T1) to 0.32 (T14) under unstressed conditions and from 0.13 (T5) to 0.27 (T8) under stressed conditions. Furthermore, in comparison to the control treatment (18.61, T5) under stressful settings, the greatest values of CAT enzyme activity (Unit mg−1 protein) were 20.65 for T8, followed by 20.47 for T6 and 18.86 for T7 (Figure 7). However, our results regarding the APX enzyme were statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05). According to the data, under stressful conditions, T8 registered 371.75 Unit mg −1 protein, while T4 registered 413.69 Unit mg−1 protein in comparison to other treatments under study (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Effect of soaking with S. diastaticus (AO7) and SA (2.0%) on antioxidant enzymes of cowpea plants under stressed and unstressed of drought after 60 days from sowing. T1: control, T2: soaking with S. diastaticus, T3: soaking with salicylic acid, T4: mixture from T2 + T3 treatments (1:1); T1–T4: unstressed; T5–T8: stressed. POX: Peroxidase; PPO: Polyphenol Oxidase; CAT: Catalase; APX: Ascorbic peroxidase. Using DMRT (5%), the means that are followed by a common letter do not differ substantially. Values are mean following the SD of three replicates.

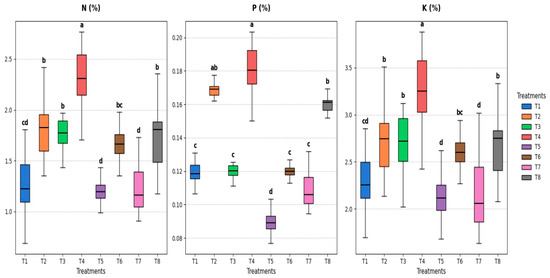

3.6.5. N, P, and K (%)

Depending on the various soaking treatments with S. diastaticus (AO7) and SA (2.0%), the mineral composition of cowpea leaves (N, P, and K %) varied considerably (p ≤ 0.05) (Figure 8). In comparison to other treatments under unstressed conditions, the treated cowpea seeds showed elevated N (%) after two months from sowing, from 1.30 (T1) to 2.30 (T4), while the same treatment significantly increased P (%) from 0.12 (T1) to 0.18 (T4) and increased K (%) from 2.33 (T1) to 3.24 (T4) (Figure 8). The highest values under stress were 1.72% for N, 0.16% for P, and 2.66% for K when treatment T8 was compared to the control and other treatments (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Effect of soaking with S. diastaticus (AO7) and SA (2.0%) on mineral compositions of cowpea leaves (N, P, and K %) under stressed and unstressed of drought after 60 days from sowing. T1: control, T2: soaking with S. diastaticus, T3: soaking with salicylic acid, T4: mixture from T2 + T3 treatments (1:1); T1–T4: unstressed; T5–T8: stressed. Using DMRT (5%), the means that are followed by a common letter do not differ substantially. Values are mean following the SD of three replicates.

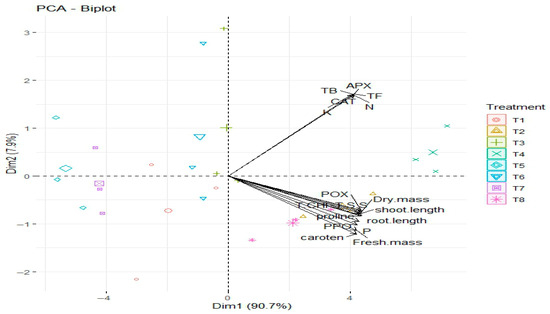

3.6.6. Analyzing the PCA Biplot

The relationship between the various cowpea plant characteristics and the various soaking treatments T1–T8 are depicted in the PCA biplot (Figure 9). Together, the first principle component (Dim1) and second principal component (Dim 2) account for a significant 98.6% of the entire variability in the dataset, explaining 90.7% and 7.9% of the total variation, respectively. Variables that heavily contribute to this main component include fresh mass, shoot length, root length, and dry mass. These variables are positively correlated and aligned in the same direction along Dim1.

Figure 9.

PCA biplot shows the relationships between the different parameters studied of cowpea plants and different soaking treatments. T1: control, T2: soaking with S. diastaticus, T3: soaking with salicylic acid, T4: mixture from T2 + T3 treatments (1:1); T1–T4: unstressed; T5–T8: stressed.

Similar to this, APX, CAT, TF, and N project significantly along Dim 2 and are positively correlated, indicating a connection between these biochemical traits (Figure 9). Additionally, treatments are distributed throughout the four quadrants, each of which reflects a different reaction. Stronger connections with specific qualities are indicated by treatments placed close to their vectors. For example, treatments near the dry mass and shoot length vectors on the right side of the biplot probably showed superior growth performance, whereas treatments near the APX, CAT, and TF vectors may have higher enzymatic or antioxidant activity (Figure 9). All things considered, the PCA effectively divides the treatments according to their development and biochemical characteristics, displaying distinct patterns of correlation between treatments and variables that are assessed.

4. Discussion

Abiotic stressors like drought, salt, and cold are constantly present for plants [54]. Over the years, drought has drawn more attention from researchers as one of the most significant environmental issues impacting plant growth and development, which in turn affects agricultural production and food supply. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) and salicylic acid (SA) are crucial for improving plant resistance to drought stress. SA aids in the regulation of osmotic equilibrium, antioxidant activity, and stress-responsive signaling pathways, enabling plants to continue growing when water availability is restricted [8]. PGPR enhances root growth, boosts nutrient uptake, and promotes the synthesis of phytohormones that aid in drought resistance. SA and PGPR work in concert to improve plant physiological and biochemical responses to drought. When combined, they offer a viable and sustainable approach to enhancing crop production in situations where there is a water shortage [55,56].

In our study, fifteen bacterial isolates (AO1–AO15) were obtained upon their tolerance to PEG6000 (0, 5, 10, 15, and 20%) using nutrient agar medium (Figure 2). While all isolates demonstrated some PEG tolerance, AO4, AO7, and AO12 exhibited the highest tolerance, which due to osmoadaptation mechanisms that enable survival under reduced water availability. Tolerant bacteria accumulate compatible solutes like proline, trehalose, and glycine betaine to manage osmotic balance and protect cellular structures [57,58]. They alter membrane fatty acid composition to maintain integrity and activate antioxidant systems to mitigate oxidative damage from osmotic stress. PEG stress also promotes the expression of osmoregulatory genes, enhancing bacterial survival in water-deficit conditions, thereby allowing growth under high PEG-induced osmotic pressure [59].

For plant growth-promoting traits, the chosen bacterial isolates were evaluated under different levels of PEG6000, which producing the highest IAA, solubilized phosphate and ammonia (Figure 3). The capacity of several rhizospheric bacteria to make IAA and their various biochemical pathways for doing so have been reported [60]. IAA is essential for plant growth and can sustain its host under stressful circumstances like drought. Additionally, it enhances lateral root development and elongation in plants, as well as seedling growth and cell differentiation [61]. As confirmed by Lata et al. [62], who found that the addition of L- tryptophan in medium can increase the secretion of IAA produced by these bacteria. In this sense, the growth and development of cowpea plants under drought stress can be enhanced by inoculating them with bacteria that produce IAA [63]. For solubilization of phosphate, bacteria can increase the availability of P by production of organic acids and chelating substances that aid in lowering the pH of the rhizosphere and the secretion of phosphatase, which releases phosphorus (P) bound in organic matter [64]. Inorganic phosphates have also been reported to be solubilized by a number of bacterial species, including Bacillus and Pseudomonas. According to a study by Kouas et al. [65], certain bacteria that could solubilize mineral phosphate improved the growth of barley. Additionally, phosphate solubilization in Arthrobacter arilaitensis and Streptomyces pseudovenezuelae was described by [66]. Additionally, due to modifications in their metabolic pathways, certain drought-tolerant bacteria can produce more ammonia when there is a shortage of water. Many PGPR strains activate ACC deaminase during drought stress, which reduces plant ethylene levels and increases stress tolerance by breaking down ACC into ammonia as a byproduct [67]. Furthermore, despite decreased moisture, osmotic stress may activate nitrogen-related enzymes, enabling bacteria to sustain or improve ammonification. In times of drought, this activity encourages root growth and supports plant nourishment. Increased NH3 synthesis is therefore thought to be one of the helpful rhizobacteria stress-reduction tactics [68,69].

A mong of the studied isolates, AO7 exhibited the highest fresh weight, dry weight, root colonization, and RWC when PEG concentration in the growth medium increased to 20% (Table 1). These outcomes could be explained by the positive effects of PGPB, which improve nutrient uptake and promote root growth, enabling the seedlings to take in more water and minerals [70]. Additionally, they generate phytohormones that support general plant growth, such as auxins and cytokinins. Also, some bacteria help the plant’s tissues retain more water by improving its osmotic adjustment. In comparison to untreated plants, treated seedlings exhibit greater biomass and improved hydration [71,72].

The results in Table 2, indicate that both fresh and dry weight as well as root colonization, and RWC were generally higher at 20% PEG compared to 0% at 2.0 mM of SA. By boosting cell membrane permeability, SA enhances the absorption of water and minerals, increasing tissue hydration and fresh weight. Additionally, it promotes photosynthesis and metabolic activity, which increases dry weight and biomass growth [73,74]. SA also increases the amount of chlorophyll and controls stomatal opening, which promotes the synthesis of carbohydrates and the retention of water. Lastly, it triggers antioxidant defenses, preserving tissue integrity and shielding cells from oxidative damage [75,76].

Our findings for the pot experiment demonstrated that soaking cowpea seeds with S. diastaticus (1 × 109 CFU mL−1) and SA (2 mM) together improves vegetative features (fresh weight, dry weight, shoot length, and root length) via encouraging growth in a synergistic manner (Table 3). While SA increases metabolic activity, beneficial bacteria enhance nutrient intake, root growth, and phytohormone production. When combined, they support larger fresh and dry weight by increasing water absorption, biomass accumulation, and chlorophyll content [55]. Furthermore, the combo reduces oxidative damage under stress by bolstering antioxidant defenses. In the end, this synergy produces seedlings that are stronger, healthier, and have better vegetative growth [4,77]. Similar results were examined by [27], who found that, although still less than the irrigated control, the combination of PGPR and salicylic acid (SA) produced the greatest growth improvements (60% in shoot length and 67% in root length) in sunflower plants when compared to the stressed control. Additionally, under drought stress circumstances, bacterially inoculated maize plants grew better than uninoculated plants in terms of survival, dry root and shoot weight, and root and shoot length [63].

By improving the rhizosphere environment, cowpea seeds treated with a bacterial suspension and SA together can increase population counts (Figure 5). According to Sorty et al. [78], SA may promote the exudation of sugars, amino acids, and other nutrients from roots, which nourish soil bacteria and aid in their growth. In the meantime, beneficial bacteria can increase water retention and habitat suitability by improving soil structure (e.g., through exopolysaccharides) [79]. By lowering plant stress and encouraging root-microbe communication, the bacterium-SA synergy also enhances microbial colonization. Consequently, this combination treatment increases microbial proliferation in the soil. According to Hafez et al. [80], the combination treatment of PGPR and SA greatly boosted soil microbial populations, particularly N2-fixing bacteria counts, which were reported at 4.35–4.98 log CFU mL−1 under water shortage and 4.37–5.57 log CFU mL−1 under well-watered circumstances.

SA and a bacterial soaking applied together can improve cowpea physiological characteristics by upregulating stress-responsive pathways (Figure 6 and Figure 7). In order to preserve cell turgor, beneficial bacteria enhance root architecture and water uptake. By raising chlorophyll content and maintaining photosystem functioning, SA further increases photosynthetic efficiency. When combined, they increase the activity of antioxidant enzymes (such APX and CAT), which lessens the buildup of ROS during drought. Therefore, this synergy enhances the water status, gas exchange, and general physiological performance of plants [81]. According to Tanveer [82], applying salicylic acid and Pseudomonas putida together had more notable outcomes than applying them separately. Shoot length, root length, and leaf area increased by 25, 27, and 39%, in canola plants, respectively. The relative water content and membrane stability index have increased by 14 and 12%, respectively, due to the synergistic effect of both treatments, However, the proline content increased to 18% after P. putida treatment and 28% after salicylic acid treatment.

Beneficial bacteria were shown to increase soluble sugar, phenols, and flavonoids in multiple publications [83]. Additionally, Azotobacter chroococcum inoculation increased ascorbate peroxidase, catalase, and peroxidase activity in stressed maize, according to [84], Azospirillum inoculation increased the synthesis of superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase, guaiacol peroxidase, and glutathione reductase in stressed maize [85]. Additionally, using Pseudomonas strains increases the amount of antioxidants that plants produce. They lessen the quantity of free radicals and aid in redox buffering. The plant defense system is strengthened by these actions [86].

According to our findings, which are displayed in Figure 8, soaking cowpea seeds in a bacterial suspension together with SA raises the levels of N, P, and K in plants via improving nutrient absorption and mobilization. In the rhizosphere, beneficial bacteria fix atmospheric nitrogen, enhance root growth, and solubilize phosphate and potassium, increasing their availability to the plant [15]. SA improves the efficiency of food absorption by boosting membrane permeability and root metabolic activity [87]. Together, they increase the expression of transporter genes involved in the uptake of N, P, and K and improve root-microbe signaling. Higher nutrient content and better overall plant growth under stress are the outcomes of this combination. These results are consistent with other research showing that, in the presence of abiotic stress, PGPR and SA combined can greatly enhance nutrient absorption and plant nutritional status [27,80].

Therefore, cowpea tolerance to drought stress was greatly increased by applying salicylic acid and PGPR. This improved physiological performance, nutrient uptake, and general plant vigor. Soaking with bacterial culture and SA have synergistic effects that demonstrate their potential as environmentally friendly, sustainable methods of enhancing crop resistance in water-limited environments. These results add to the mounting body of evidence in favor of biological and biochemical strategies for reducing abiotic stress in legumes. To guarantee long-term agricultural sustainability, future research should examine the molecular mechanisms underlying this synergy, determine the most effective microbial strains for various soil types, and assess field-scale applications.

5. Conclusions

This study investigates drought-tolerant PGPR strains and their effects on cowpea plant growth, physiological traits, and mineral content under drought stress and non-stressed conditions. Of fifteen bacterial isolates, AO7 (Streptomyces diastaticus subsp. ardesiacus) significantly promoted growth in cowpea. A pot experiment in 2023, using a split-plot design with varying irrigation and soaking treatments, revealed that a combination of S. diastaticus and salicylic acid (2 mM) enhanced growth metrics under drought stress after 60 days. The highest chlorophyll content was noted in treatment T8 (2.0% SA) under stress, alongside increased proline and enzyme activity, indicating positive treatment responses. Therefore, T8 > T6 > T7 > T5 for stressed conditions and T4 > T2 > T3 > T1 for normal conditions, demonstrating that the combined use of S. diastaticus and SA improves cowpea growth under drought stress.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.E.-D.O., D.F.I.A., N.M.E.D. and S.E.-N.; methodology, A.E.-D.O., D.F.I.A., N.M.E.D. and S.E.-N.; software, A.E.-D.O. and S.E.-N.; validation, A.E.-D.O. and S.E.-N.; formal analysis, A.E.-D.O. and S.E.-N.; investigation, A.E.-D.O., D.F.I.A., N.M.E.D. and S.E.-N.; resources, A.E.-D.O. and S.E.-N.; data curation, A.E.-D.O. and S.E.-N.; writing—original draft preparation, A.E.-D.O.; writing—review and editing, A.E.-D.O.; visualization, A.E.-D.O., D.F.I.A., N.M.E.D. and S.E.-N.; supervision, A.E.-D.O.; project administration, A.E.-D.O.; funding acquisition, A.E.-D.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data sets analyzed during the present study are accessible from the current author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

All the authors are grateful for the support provided by Soils, Water, and Environment Research Institute (SWERI), Agriculture Research Center (ARC), Egypt.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SA | Salicylic acid |

| PEG6000 | Poly ethylene glycol 6000 |

| PGPR | Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria |

| CFU | Linear dichroism |

| 16 S rRNA | 16S ribosomal ribonucleic acid |

| CAT | Catalase |

| POX | peroxidase |

| PPO | polyphenol oxidase |

| APX | ascorbate peroxidase |

| IAA | Indole acetic acid |

| DMRT | Duncan’s multiple range testing |

References

- Mirzabaev, A.; Kerr, R.B.; Hasegawa, T.; Pradhan, P.; Wreford, A.; von der Pahlen, M.C.T.; Gurney-Smith, H. Severe climate change risks to food security and nutrition. Clim. Risk Manag. 2023, 39, 100473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahlali, R.; Laasli, S.-E.; Barka, E.A. Plant responses to biotic and abiotic stresses: From cellular to morphological changes—Series II. Agronomy 2025, 15, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, M.; Waheed, A.; Wahab, A.; Majeed, M.; Nazim, M.; Liu, Y.-H.; Li, L.; Li, W.-J. Soil salinity and drought tolerance: An evaluation of plant growth, productivity, microbial diversity, and amelioration strategies. Plant Stress 2024, 11, 100319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A.; Wang, Y.-F.; Akbar, R.; Alhoqail, W.A. Mechanistic insights and future perspectives of drought stress management in staple crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1547452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbir, R.; Singhal, R.K.; Mishra, U.N.; Chauhan, J.; Javed, T.; Hussain, S.; Kumar, S.; Anuragi, H.; Lal, D.; Chen, P. Combined abiotic stresses: Challenges and potential for crop improvement. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, T.; Jalil, S.; Jilani, G.; Chaudhry, A.N.; Naz, I.; Khan, A.; Yang, X.; Brestic, M.; Milan, S.; El Sabagh, A. Enhancing crop resilience to water stress through iron nanoparticles: A critical review of applications and implications. Plant Stress 2025, 25, 100905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.K.; Ochar, K.; Iwar, K.; Ha, B.K.; Kim, S.H. Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L.) production, genetic resources and strategic breeding priorities for sustainable food security: A review. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1562142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, A.S.; Costa, R.R.; Sá, F.V.; Dias, G.F.; Alencar, R.S.; Viana, P.M.; Peixoto, T.D.; Suassuna, J.F.; Brito, M.E.; Ferraz, R.L.; et al. Modulation of drought-induced stress in cowpea genotypes using exogenous salicylic acid. Plants 2024, 13, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Das, N.; Pandey, P.; Shukla, P. Plant-microbiome responses under drought stress and their metabolite-mediated interactions towards enhanced crop resilience. Curr. Plant Biol. 2025, 3, 100513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tochihara-Tanaka, M.; Kai, S.; Murakami, N.; Murakami, S.; Miura, N.; Komai, R.; Tatsumi, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Hamaoka, N.; Iwaya-Inoue, M.; et al. Drought tolerance of cowpea is associated with rapid abscisic acid biosynthesis via VuWRKY57 in root. AoB Plants 2025, 17, plaf038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiombiano, C.; Lado, A.; Coulibaly, S.; Tukur, T.; Bello, T.; Serme, I.; Gnankambary, K.; Sawadogo, N.; Ouedraogo, M.H.; De La Salle, J.B.; et al. Assessment of the Effects of Drought Stress at Seedling and Flowering Stages of Cowpea Development on Yield and Yield Attributes. J. Agric. Environ. Sci. 2023, 12, 68–80. [Google Scholar]

- Loushigam, G.; Shanmugam, A. Modifications to functional and biological properties of proteins of cowpea pulse crop by ultrasound-assisted extraction. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023, 97, 106448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chieb, M.; Gachomo, E.W. The role of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria in plant drought stress responses. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbodjato, N.A.; Babalola, O.O. Promoting sustainable agriculture by exploiting plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) to improve maize and cowpea crops. PeerJ 2024, 12, e16836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawula, S.; Daniel, A.I.; Nyawo, N.; Ndlazi, K.; Sibiya, S.; Ntshalintshali, S.; Nzuza, G.; Gokul, A.; Keyster, M.; Klein, A.; et al. Optimizing plant resilience with growth-promoting Rhizobacteria under abiotic and biotic stress conditions. Plant Stress 2025, 9, 100949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Tahir, S.; Hassan, S.S.; Lu, M.; Wang, X.; Quyen, L.T.; Zhang, W.; Chen, S. The Role of Phytohormones in Mediating Drought Stress Responses in Populus Species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adegboye, M.F.; Babalola, O.O. Actinomycetes: A yet inexhaustive source of bioactive secondary metabolites. Microb. Pathog. Strateg. Combat. Them Sci. Technol. Educ. 2013, 4, 786–795. [Google Scholar]

- Khantsi, M.; Adegboye, M.F.; Babalola, O.O. 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase (ACCd) activity as a marker for identifying plant-growth promoting rhizomicrobes in cultivated soil of South Africa. Asia Life Sci. 2013, 1, 199–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ndeddy Aka, R.J.; Babalola, O.O. Identification and characterization of Cr-, Cd-, and Ni-tolerant bacteria isolated from mine tailings. Bioremediation J. 2017, 21, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pishchik, V.N.; Chizhevskaya, E.P.; Chebotar, V.K.; Mirskaya, G.V.; Khomyakov, Y.V.; Vertebny, V.E.; Kononchuk, P.Y.; Kudryavtcev, D.V.; Bortsova, O.A.; Lapenko, N.G.; et al. PGPB Isolated from Drought-Tolerant Plants Help Wheat Plants to Overcome Osmotic Stress. Plants 2024, 13, 3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shreshtha, K.; Prakash, A.; Pandey, P.K.; Pal, A.K.; Singh, J.; Tripathi, P.; Mitra, D.; Jaiswal, D.K.; de Los Santos-Villalobos, S.; Tripathi, V. Isolation and characterization of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria from cacti root under drought condition. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2025, 8, 100319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngamcharungchit, C.; Chaimusik, N.; Panbangred, W.; Euanorasetr, J.; Intra, B. Bioactive metabolites from terrestrial and marine actinomycetes. Molecules 2023, 28, 5915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariyanna, B.; Panda, S. Unveiling the advanced application of actinomycetes in biotic stress management for sustainable agriculture. Discov. Life 2025, 55, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayyab, N.; Naz, R.; Yasmin, H.; Nosheen, A.; Keyani, R.; Sajjad, M.; Hassan, M.N.; Roberts, T.H. Combined seed and foliar pre-treatments with exogenous methyl jasmonate and salicylic acid mitigate drought-induced stress in maize. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemi, R.; Wang, R.; Gheith, E.S.; Hussain, H.A.; Hussain, S.; Irfan, M.; Cholidah, L.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, S.; Wang, L. Effects of salicylic acid, zinc and glycine betaine on morpho-physiological growth and yield of maize under drought stress. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalvandi, M.; Siosemardeh, A.; Roohi, E.; Keramati, S. Salicylic acid alleviated the effect of drought stress on photosynthetic characteristics and leaf protein pattern in winter wheat. Heliyon 2021, 7, e05908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmat, A.; Yasmin, H.; Hassan, M.N.; Nosheen, A.; Naz, R.; Sajjad, M.; Ilyas, N.; Akhtar, M.N. Co-application of bio-fertilizer and salicylic acid improves growth, photosynthetic pigments and stress tolerance in wheat under drought stress. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Q.; Ahmad, M.; Kamran, M.; Ashraf, S.; Shabaan, M.; Babar, B.H.; Zulfiqar, U.; Haider, F.U.; Ali, M.A.; Elshikh, M.S. Synergistic effects of Rhizobacteria and salicylic acid on maize salt-stress tolerance. Plants 2023, 12, 2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, B.E.; Kaufmann, M.R. The osmotic potential of polyethylene glycol 6000. Plant Physiol. 1973, 51, 914–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, O.N. Experiments in Soil Bacteriology; Burgess Publishing Co.: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova, E.G.; Doronina, N.V.; Trotsenko, Y.A. Aerobic Methylobacteria Are Capable of Synthesizing Auxins. Microbiology 2001, 70, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, S.R.; Sommers, L.E. Phosphorus. In Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 2, 2nd ed.; Agronomy Monograph Number 9; Page, A.L., Miller, R.H., Keeney, D.R., Eds.; ASA and SSSA: Madison, WI, USA, 1982; pp. 403–430. [Google Scholar]

- Cappuccino, J.G.; Sherman, N. Biochemical activities of microorganisms. In Microbiology, A Laboratory Manual; The Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Co.: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 1992; Volume 76. [Google Scholar]

- Simons, M.; van der Bij, A.J.; Brand, I.; de Weger, L.A.; Wijffelman, C.A.; Lugtenberg, B. Gnotobiotic system for studying rhizosphere colonization by plant growth-promoting Pseudomonas bacteria. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 1996, 9, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skradleta, V.; Gaudinova, A.; Necova, M.; Hydrakova, A. Behaviour of nodulated Pisum sativum L. under short term nitrate stress conditions. Biol. Plant 1984, 26, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Nahrawy, S.; Elhawat, N.; Alshaal, T. Biochemical traits of Bacillus subtilis MF497446: Its implications on the development of cowpea under cadmium stress and ensuring food safety. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 180, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrs, H.D.; Weatherley, P.E. A re-examination of the relative turgidity technique for estimating water deficits in leaves. Aust. J. Biol. Sci. 1962, 15, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somasegaran, P.; Hoben, H.J. Handbook for Rhizobia. In Methods in Legume—Rhizobium Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, J.G.; Krieg, N.R.; Sneath, P.H.A.; Staley, J.T.; Willams, S.T. Bergeys Manual of Determinative Bacteriology; Williams and Wilkins: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: Pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes. In Methods in Enzymology; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1987; Volume 148, pp. 350–382. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix, D.L. Rapid extraction and analysis of nonstructural carbohydrates in plant tissues. Crop Sci. 1993, 33, 1306–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, L.S.; Waldren, R.P.; Teare, I.D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil 1973, 39, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, O.N. Experiments in Soil Bacteriology, 2nd ed.; University of Wisconsin: Madison, WI, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, S.K. Peroxidase and polyphenol-oxidase in Brassica juncea plants infected with Macrophomina phaseolina (Tassi): Goid of and their implication in disease resistance. Phytopathology 1987, 120, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matta, A.I.; Dimond, A.F. Symptoms of Fusarium wilt in relation to quantity of fungus and enzyme activity in tomato stems. Phytopathology 1963, 53, 574–578. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, M.V.; Paliyath, C.; Ormrod, D.P.; Murr, D.P.; Watkins, C.B. Influence of salicylic acid on H2O2 production, oxidative stress and H2O2-metabolizing enzymes: Salicylic acidmediated oxidative damage requires H2O2. Plant Physiol. 1997, 115, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, Y.; Asada, K. Hydrogen peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 1981, 5, 867–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, A.L.; Miller, R.H.; Keeny, D.R. Methods of Soil Analysis, Part II, Agronomy Monographs ASA and SSSA, 2nd ed.; Madison Book Company: Madison, WI, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, J.; Riley, J.P. A modified single solution method for the determination of phosphate in natural waters. Anal. Chim. Acta 1962, 27, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA. Soil Survey Laboratory Methods Manual Soil Survey Investigation Report, No. 42, Version 4; USDA-NRCS: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, D.B. Multiple range and multiple F tests. Biometrics 1955, 11, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonomura, Y. Fine structure of the thick filament in molluscan catch muscle. J. Mol. Biol. 1974, 2, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, R.G.; Holt, J.G. The history of Bergey’s Manual. In Bergey’s Manual® of Systematic Bacteriology; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2005; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bardi, L.; Malusà, E. Drought and nutritional stresses in plant: Alleviating role of rhizospheric microorganisms. Abiotic Stress New Res. 2012, 1–57. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260902565_Drought_and_nutritional_stresses_in_plant_Alleviating_role_of_rhizospheric_microorganisms (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- El-Saadony, M.T.; Saad, A.M.; Mohammed, D.M.; Fahmy, M.A.; Elesawi, I.E.; Ahmed, A.E.; Algopishi, U.B.; Elrys, A.S.; Desoky, E.S.M.; Mosa, W.F.; et al. Drought-tolerant plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria alleviate drought stress and enhance soil health for sustainable agriculture: A comprehensive review. Plant Stress 2024, 14, 100632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, D.; Liu, F.; Li, S.; Dong, Y. Synergistic effects of SAP and PGPR on physiological characteristics of leaves and soil enzyme activities in the rhizosphere of poplar seedlings under drought stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1485362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imhoff, J.F.; Rahn, T.; Künzel, S.; Keller, A.; Neulinger, S.C. Osmotic adaptation and compatible solute biosynthesis of phototrophic bacteria as revealed from genome analyses. Microorganisms 2020, 9, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goszcz, A.; Furtak, K.; Stasiuk, R.; Wójtowicz, J.; Musiałowski, M.; Schiavon, M.; Dębiec-Andrzejewska, K. Bacterial osmoprotectants-a way to survive in saline conditions and potential crop allies. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2025, 16, fuaf020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, N.; Jiang, C.; Chen, L.; Paul, A.; Chatterjee, A.; Shen, G. Achieving abiotic stress tolerance in plants through antioxidative defense mechanisms. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1110622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timofeeva, A.M.; Galyamova, M.R.; Sedykh, S.E. How do plant growth-promoting bacteria use plant hormones to regulate stress reactions? Plants 2024, 13, 2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etesami, H.; Glick, B.R. Bacterial indole-3-acetic acid: A key regulator for plant growth, plant-microbe interactions, and agricultural adaptive resilience. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 281, 127602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lata, D.L.; Abdie, O.; Rezene, Y. IAA-producing bacteria from the rhizosphere of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.): Isolation, characterization, and their effects on plant growth performance. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwuneme, C.F.; Babalola, O.O.; Kutu, F.R.; Ojuederie, O.B. Characterization of actinomycetes isolates for plant growth promoting traits and their effects on drought tolerance in maize. J. Plant Interact. 2020, 15, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ughamba, K.T.; Ndukwe, J.K.; Lidbury, I.D.; Nnaji, N.D.; Eze, C.N.; Aduba, C.C.; Groenhof, S.; Chukwu, K.O.; Anyanwu, C.U.; Nwaiwu, O.; et al. Trends in the application of phosphate-solubilizing microbes as biofertilizers: Implications for soil improvement. Soil Syst. 2025, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouas, S.; Djedidi, S.; Debez, I.B.; Sbissi, I.; Alyami, N.M.; Hirsch, A.M. Halotolerant phosphate solubilizing bacteria isolated from arid area in Tunisia improve P status and photosynthetic activity of cultivated barley under P shortage. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onyia, C.; Obih, E.C.; Bassa, J.S.; Chinenyenwa, C.F.; Engwa Azeh, A.G. Evolutionary relationship of four major ethnic populations in Nigeria based on Alu PV92 insertion polymorphism. Int. J. Hum. Genet. 2020, 2, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, J.D.; Vidal, M.S.; Baldani, J.I. Exploring ACC deaminase-producing bacteria for drought stress mitigation in Brachiaria. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1607697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Turki, A.; Murali, M.; Omar, A.F.; Rehan, M.; Sayyed, R.Z. Recent advances in PGPR-mediated resilience toward interactive effects of drought and salt stress in plants. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1214845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhan, M.; Sathish, M.; Kiran, R.; Mushtaq, A.; Baazeem, A.; Hasnain, A.; Hakim, F.; Hasan Naqvi, S.A.; Mubeen, M.; Iftikhar, Y.; et al. Plant Nitrogen Metabolism: Balancing Resilience to Nutritional Stress and Abiotic Challenges. Phyton-Int. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 93, 581–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoso, M.A.; Wagan, S.; Alam, I.; Hussain, A.; Ali, Q.; Saha, S.; Poudel, T.R.; Manghwar, H.; Liu, F. Impact of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) on plant nutrition and root characteristics: Current perspective. Plant Stress 2024, 11, 100341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansabayeva, A.; Makhambetov, M.; Rebouh, N.Y.; Abdelkader, M.; Saudy, H.S.; Hassan, K.M.; Nasser, M.A.; Ali, M.A.; Ebrahim, M. Plant growth-promoting microbes for resilient farming systems: Mitigating environmental stressors and boosting crops productivity—A review. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Sharma, P.L.; Paul, P.; Baruah, N.R.; Choudhury, J.; Begum, T.; Karmakar, R.; Khan, T.; Kalita, J. Harnessing endophytes: Innovative strategies for sustainable agricultural practices. Discov. Bact. 2025, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riyazuddin, R.; Nisha, N.; Gupta, R. Phytonanotechnology in the mitigation of biotic and abiotic stresses in plants. Plant Nano Biol. 2025, 12, 100173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Youssef, R.; Jelali, N.; Acosta Motos, J.R.; Abdelly, C.; Albacete, A. Salicylic acid seed priming: A key frontier in conferring salt stress tolerance in barley seed germination and seedling growth. Agronomy 2025, 15, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, P.; Balawi, T.A.; Faizan, M. Salicylic acid’s impact on growth, photosynthesis, and antioxidant enzyme activity of Triticum aestivum when exposed to salt. Molecules 2022, 28, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco-Navarro, J.D.; Padilla, Y.G.; Álvarez, S.; Calatayud, Á.; Colmenero-Flores, J.M.; Gómez-Bellot, M.J.; Hernández, J.A.; Martínez-Alcalá, I.; Penella, C.; Pérez-Pérez, J.G.; et al. Advancements in Water-Saving Strategies and Crop Adaptation to Drought: A Comprehensive Review. Physiol. Plant. 2025, 177, e70332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dere, S. Mitigating the Adverse Effects of Salt Stress on Pepper Plants Through Arbuscular mycorrhizal Fungi (AMF) and Beneficial Bacterial (PGPR) Inoculation. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorty, A.M.; Kudjordjie, E.N.; Meena, K.K.; Nicolaisen, M.; Stougaard, P. Plant Root Exudates: Advances in belowground signaling networks, resilience, and ecosystem functioning for sustainable agriculture. Plant Stress 2025, 26, 100907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelman, L.; Alahmad, A.; Castel, L.; Marquet, S.; Bucaille, F.; Laval, K.; Trinsoutrot-Gattin, I.; Thioye, B. Improving drought resilience in maize through a soil-applied prebiotic: Effects on plant physiology and rhizosphere microbial function. Plant Stress 2025, 8, 101081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, E.; Omara, A.E.D.; Ahmed, A. The coupling effects of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria and salicylic acid on physiological modifications, yield traits, and productivity of wheat under water deficient conditions. Agronomy 2019, 9, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaskheli, M.A.; Nizamani, M.M.; Tarafder, E.; Das, D.; Jatoi, G.H.; Leghari, U.A.; Laghari, A.H.; Khaskheli, R.A.; Awais, M.; Wang, Y. Potential of soil associated plant growth-promoting microbes in improving the abiotic-stress resilience of agricultural crops. In Role of Antioxidants in Abiotic Stress Management Biostimulants and Protective Biochemical Agents; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025; pp. 333–362. [Google Scholar]

- Tanveer, S.; Akhtar, N.; Ilyas, N.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Fitriatin, B.N.; Perveen, K.; Bukhari, N.A. Interactive effects of Pseudomonas putida and salicylic acid for mitigating drought tolerance in canola (Brassica napus L.). Heliyon 2023, 9, e14193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asghari, B.; Khademian, R.; Sedaghati, B. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) confer drought resistance and stimulate biosynthesis of secondary metabolites in pennyroyal (Mentha pulegium L.) under water shortage condition. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 263, 109132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Latef, A.A.; Abu Alhmad, M.F.; Kordrostami, M.; Abo-Baker, A.B.; Zakir, A. Inoculation with Azospirillum lipoferum or Azotobacter chroococcum reinforces maize growth by improving physiological activities under saline conditions. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2020, 39, 1293–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checchio, M.V.; de Cássia Alves, R.; de Oliveira, K.R.; Moro, G.V.; Santos, D.M.; Gratão, P.L. Enhancement of salt tolerance in corn using Azospirillum brasilense: An approach on antioxidant systems. J. Plant Res. 2021, 134, 1279–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekureyaw, M.F.; Beierholm, A.E.; Nybroe, O.; Roitsch, T.G. Inoculation of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) roots with growth promoting Pseudomonas strains induces distinct local and systemic metabolic biosignatures. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2022, 117, 101757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, M.; Khalid, B.; Batool, M.; Ullah, M.; Zitong, J.; Rauf, A.; Rao, M.J.; Rehman, H.U.; Kuai, J.; Xu, Z.; et al. Secondary metabolites as biostimulants in salt stressed plants: Mechanisms of oxidative defense and signal transduction. Plant Stress 2025, 13, 100891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).