Abstract

The microbiome of howler monkeys is being studied as a potential indicator of forest health. This explorative research aimed to analyze the microbiome, antibiotic resistance genes, and virulence factors of the howler monkey (Alouatta seniculus) in two Colombian Andean forests. A total of six samples were collected from three monkeys in two different forests. The samples were processed and sequenced using 16S rRNA V3-V4 metabarcoding and shotgun metagenomics. No significant differences in microbial diversity were observed between locations. A total of 43 possible resistance genes were identified, 11 of which were associated with plasmids, while 66 virulence genes were detected. The bacterial genera with the highest number of resistance genes were Escherichia and Enterococcus, whereas Escherichia and Citrobacter exhibited the highest number of virulence factors. The bacteria were predominantly resistant to fluoroquinolones, macrolides and beta-lactams, while adherence was the dominant virulence mechanism. This exploratory study suggests that the locations provide similar habitats for howler monkeys and that the presence of resistance genes is primarily due to intrinsic bacterial resistance mechanisms and natural resistance in wild populations despite the environmental presence of bacterial genera with resistance genes and virulence factors. However, acquisition through interaction with domestic animals was not evaluated.

Keywords:

antimicrobial resistance; howler monkey; metagenome; microbiome; primate; virulence factor 1. Introduction

The study of the gut microbiome in primates provides valuable information on their nutrition, physiology, immunity, and ecology [1]. Research on wild baboons (Papio anubis) has revealed changes in their microbiome due to the introduction of human diets high in processed foods [2]. Experiments with macaques (Macaca mulatta) have shown that a shift in gut bacteria composition can impact mucosal immunity [3]. Additionally, the microbiome in primates reflects aspects such as age, social structure, and environmental differences, contributing to our understanding of primate species [1]. Therefore, studying the gut microbiome is essential for advancing our knowledge of primate biology.

Howler monkeys (Alouatta Lacepede 1799) are widely distributed in neotropical forests, with densities exceeding one hundred monkeys per square kilometer [4,5]. The composition of the howler monkey microbiome may be influenced by the quality and temporal variation in their food resources. Differences in the howler monkeys microbiome diversity could indicate the health of the forest where they live [1]. The availability of food, such as young leaves and immature fruits, can influence the relative abundance of Ruminococcaceae and Butyricicoccus, thereby affecting microbiome diversity [6,7]. Therefore, monitoring the microbiomes of howler monkeys and other animals could contribute to the conservation of neotropical forests, as habitat fragmentation, climate, and captivity may influence the microbiomes of wild animals [8].

Bacteria in the microbiome can carry resistance and virulence genes (VFs). In the case of wild animals, the presence of resistance genes is considered natural [9]. In Enterobacteria, studies in terrestrial wild animals have found intrinsic resistance to tetracyclines, colistin, amoxicillin, first-generation aminopenicillins, and cephalosporins [10]. However, in humans and domestic animals, the presence of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) is often due to the misuse of antibiotics [11,12], there is evidence of antibiotic resistance profiles in farms and animal breeding facilities, associated with antibiotics commonly used in livestock, with resistance to β-lactams and uncommon genes in animals related to tetracycline resistance serving as examples of these findings [13]. Therefore, the resistance and virulence genes of wild animals can be influenced by the proximity of human activities such as livestock farming and/or cities, leading to horizontal gene transfer [14,15]. Previous studies suggest that wild animals living in proximity to farms are more likely to harbor resistance genes compared to those inhabiting natural areas [16]. It has also been reported that the transfer of antibiotic resistance genes between primates of the Alouatta genus and domestic animals is possible, especially in fragmented forests [17]. This, combined with the presence of microorganisms with zoonotic potential, can affect both the conservation of vulnerable species and human health [18]. Since resistance genes, virulence factors, and bacteria carrying resistance genes are not well studied in howler monkeys, specifically A. seniculus, little is known about the impact of human activities on their microbiota [17,19].

Two species of howler monkeys inhabit Colombia: Alouatta palliata and Alouatta seniculus [20]. Howler monkeys are associated with lowland forests [21] and Andean mountains [5], where their diet consists mainly of fruits and young leaves [22]. In general, Alouatta species in Colombia are considered flexible and adaptable, but the high fragmentation of forests is leading to population declines [5,21,23]. Due to their adaptability, howler monkeys may be considered an indicator species for forest health.

This exploratory study aimed to provide an initial analysis of the microbial diversity, resistance genes, and virulence factors in the microbiome of the howler monkey (A. seniculus) in two Colombian Andean forests. These results should be interpreted as preliminary. However, this research represents one of the first efforts to investigate the microbiome, resistance genes, and virulence factors, along with their association with plasmids, in wild A. seniculus populations in Colombia. The findings offer valuable insights into the composition and diversity of the intestinal microbiota, as well as the presence of antibiotic resistance and virulence genes in this species.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling Locations

Howler monkey sampling was conducted in the Barbas-Bremen Forest Reserve (hereafter “Barbas-Bremen”), located between the departments of Quindío and Risaralda, Colombia, and the Bosque de Yotoco Forest Reserve (hereafter “Bosque Yotoco”) in the department of Valle del Cauca, Colombia. The Barbas-Bremen Forest Reserve, covering 336 ha of remnant sub-Andean forest, is situated on the western slopes of the Central Cordillera at an altitude of 1700–2000 masl; the area’s average temperature is 16.7 °C, with an annual mean precipitation of 2890 mm [24]. The Bosque de Yotoco Forest Reserve, covering 559 ha of remnant sub-Andean forest, is located on the eastern slopes of the Cordillera Occidental at an altitude of 1200–1700 masl. The temperatures in this area range between 15 °C and 22 °C, with a mean annual precipitation exceeding 1100 mm [25]. Both reserves contain isolated forest fragments: Barbas-Bremen is fragmented by forest plantations and cattle ranching, while Bosque Yotoco is fragmented by roads [24,25]. These reserves play a crucial role in preserving water resources, supplying municipalities in three departments: Filandia (Quindío), Pereira (Risaralda), and Yotoco (Valle del Cauca) in the Andean region.

2.2. Sample Collection and Processing

Fecal samples from wild howler monkeys (Alouatta seniculus) were collected in March 2022 through active tracking and monitoring of individuals. This process involved the observation of wild groups in trees from the ground until defecation occurred. Subsequently, a 5 g sample of fresh fecal matter was carefully collected from the inner portion of the deposition to minimize external contamination, the collection hour and approximated deposition time for Barbas Bremen forest individuals was (9:20, 9:44 and 14:19) and Yotoco Forest (8:20, 12:20 and 16:19). As this study is exploratory, direct handling of wild individuals was not performed. Therefore, variables such as age and sex were not fully determined. The samples were obtained from three individuals in the Yotoco forest reserve and three individuals in the soil conservation district of Barbas-Bremen. The collected samples were preserved in a lysis buffer with proteinase K for subsequent DNA extraction in the laboratory. DNA extraction was performed using the DNeasy PowerSoil Pro (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) kit, following the manufacturer’s instructions with minor modifications. The extracted DNA was diluted in 50 μL of resuspension solution. The quality of the DNA was assessed using spectophotometry (Colibri Titertek Berthold 84030) with 2 μL of DNA, and DNA integrity was confirmed by visualization on a 1% agarose gel (w/v). Finally, the DNA from each sample was individually sent for metabarcoding sequencing, targeting the V3–V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene. Additionally, for shotgun metagenomic analysis, an equimolar pool was prepared by combining 5 μL of each sample extracted DNA used in the previous step into a single tube 30 μL which was then submitted for Illumina sequencing with the platform NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) with a sequencing depth of 30X.

We performed microbiome analysis using the QIIME2 v.2023.5 workflow [26], starting with demultiplexed sequences provided by the sequencing company. First, we used Flash v.1.2.11 [27] to merge paired-end reads from demultiplexed sequences. Then, we applied the DADA2 v.1.26.0 algorithm for quality control and feature table construction. Finally, we identified the taxonomy using the SILVA v.138.2 database [28] and generated a phylogenetic tree. We imported the metadata, taxonomy, rooted phylogeny, and processed sequence files into R v.4.4.1 [29] to create the phyloseq object [30]. We analyzed the composition at the Phylum, Class, Family and Genus levels with the relative abundance of each Amplicon Variant Sequence (ASV) in each sample using the microbiome packages [31] and microbiome utilities [32]. Next, we calculated rarefaction curves and alpha diversity indices for each sample (Chao1, ACE, Shannon). Finally, we performed principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) and Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance (PERMANOVA) to assess differences between samples based on their locality. Both analyses were performed considering the weighted UniFrac distance in the vegan package [33].

The NCBI database was used to identify sequences that the SILVA database could not classify at the genus level (resulting in an “unknown” classification) and to detect genera with zoonotic significance. First, FASTA sequences were extracted from the data obtained through the QIIME2 workflow, and those classified as “unknown” by SILVA were isolated based on their IDs. The final FASTA file (consisting of 800 sequences) was then analyzed using BLAST v.2.16.0 against the NCBI’s 16S ribosomal RNA database. Next, BLAST analysis was performed using the complete FASTA file from QIIME2 (containing 3341 sequences). The sequences were manually filtered to retain only those with 100% identity and then we searched for genera on the WHO list of important pathogens [34]. The BLAST analysis was conducted using the rBLAST v.1.3.1 package [35], applying an identity percentage cutoff of 95%. Subsequently, the sequences were filtered to have an identity percentage between 100% and 97%, and the genus with the highest percentage was chosen.

2.3. Metagenomic Assembly

The quality of the raw metagenomics readings was assessed using FastQC v.0.11.8. Afterward, the first 5 low-quality nucleotides were removed using Trimmomatic v.0.39. The high-quality reads, which were 145 nucleotides long, were then assembled with SPAdes v.3.15.5 [36]. The meta parameter for metagenomic assembly was used [37] and k-mer lengths of 23, 33, 55, 77, 99, 119 and 127 were selected. The resulting scaffolds were filtered using Seqmagick v.0.8.6 to eliminate contigs smaller than 500.

2.4. Identification of Resistance Genes and Virulence Factors

To identify resistance genes and virulence factors in the assembly, we used ABRicate v.1.0.1 (Seeman T) with both the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) [38] and the virulence factor database (VFDB) [39] (updated August 2024). We extracted contigs identified with the presence of resistance genes and an initial identity percentage ≥ 80% using a custom Python v.3.12 script (abricate_scaffolds.py), to avoid overestimation a ≥90% identity percentage was selected as reliable. These contigs were then subjected to taxonomic assignment using Kraken 2 v.2.1.3 [40] with the PlusPFP database (updated June 2024). The results were visualized in R v.4.4.1 using the package Pavian v.1.2.1 [41]. We used the KrakenTools suite [42] to extract the contigs with the presence of ARGs and VFs with the KrakenTools script (extract_kraken_reads.py) based on the identified genera. A new annotation was performed using ABRicate v.1.0.1 (Seeman T) with the same configuration, this time on the contigs corresponding to each identified genus. The results were imported, visualized and reviewed in (.tsv) format and then imported into R v.4.4.1 for graphical visualization.

2.5. Genome Reconstruction

Genome mapping was performed using minimap2 v.2.14 (r883) [43] with the -xa asm5 (assembly to assembly/ref alignment) configuration for all microorganisms belonging to the ESKAPE group and other potentially pathogenic microorganisms, which includes Enterococcus faecium (CP038996.1), Staphylococcus aureus (CP000253.1), Staphylococcus pseudintermedius (CP065635.1), Staphylococcus schleiferi (CP094712.1), Klebsiella pneumoniae (CP003200.1), Acinetobacter baumannii (CP045110.1), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (AE004091.2), Escherichia coli (U00096.3) and Enterobacter faecalis (KB944666.1). The genome assembly scaffolds obtained from the mapping process were extracted and organized based on their genomic position using Samtools [44] with the markdup option. The completeness and N50 values of the reconstructed genome were assessed using quast v.5.0.2 with the respective reference genome, and only “completeness” values exceeding 40% considered for further analysis. Subsequently, genome annotation was performed using Bakta v.1.9.4 [45] with the full database v.5.1. The search for resistance genes and virulence factors was conducted using ABRicate v.1.0.1 (Seeman T). The identified genes were positioned relative to the mapped genome using a custom Python script and manual review; the results were visually reviewed using CGview Comparison Tool v.2.0.3 [46]. This involved comparing the annotated genome obtained from the mapping and the reference genome. The ABRicate results were added according to their location in the mapped genome on an additional track.

2.6. Resistance Genes and Virulence Factors Associated with Plasmids

We used Seqmagick v.0.8.6 to filter out scaffolds smaller than 1000 obtained in the metagenomic assembly. Afterward, analyzed the remaining scaffolds using PLASMe v.1.1 [47] using the “high precision” configuration. Only scaffolds with a score > 0.9 were considered as belonging to plasmids. To identify resistance genes and virulence factors, we used ABRicate v.1.0.1 (Seeman T) on the scaffolds classified as plasmid-associated, using the same configuration as before.

3. Results

3.1. Microbiome Analysis

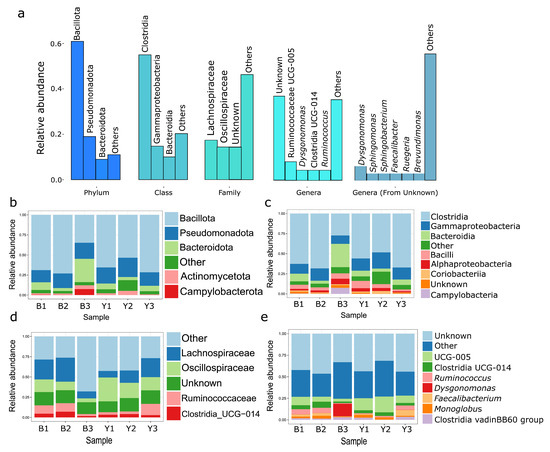

The howler monkey microbiome comprises 3341 ASVs classified into thirty-one phyla and seventy-four classes. The most abundant phyla are Bacillota, Pseudomonadota, and Bacteroidota, while the most common classes are Clostridia, Gammaproteobacteria, and Bacteroidia. The predominant families are Oscillospiraceae, Lachnospiraceae, and Ruminococcaceae, and the most prevalent genera include Ruminicoccaceae UGC-005, Dysgonomonas, Clostridia UGC-014, and Ruminococcus. Moreover, 17,277 (12.05%) sequences were cataloged as unidentified sequences; these sequences in the NCBI correspond to over one hundred genera, with Dysgonomonas, Sphingomonas, and Faecalibacter exhibiting the highest abundance (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

The taxonomic composition of the bacterial microbiome of the howler monkey (Alouatta seniculus) was analyzed in two Andean forests. (a). Analysis of phylum, class, order, and genus taxonomic composition for six individuals of A. seniculus. The data was obtained using the SILVA database and NCBI (data “unknown”). (b) The taxonomic composition at the phylum level, (c) class, (d) family, and (e) genus were analyzed for each sample from A. seniculus in the two Andean forests. The “B” samples are from the forest in the Barbas-Bremen in Quindío, while the “Y” samples are from the forest in the Yotoco-Valle del Cauca. Overall, the samples from howler monkeys show high diversity.

The taxonomic composition per sample remains consistent across all taxonomic levels, except the Barbas-Bremen individual (B3). Sample B3 exhibits a higher proportion of Bacteroidota/Bacteroidia and Campylobacterota/Campylobacteria (Figure 1b,c), a lower proportion of Oscillospiraceae (Figure 1d), and a notable variance in the genus Dysgonomonas (Figure 1e). Additionally, the following genera of zoonotic importance were identified through BLAST analysis: Enterococcus, Morganella, Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Enterobacter, Escherichia/Shigella, Klebsiella, Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas, Citrobacter, Proteus and Serratia.

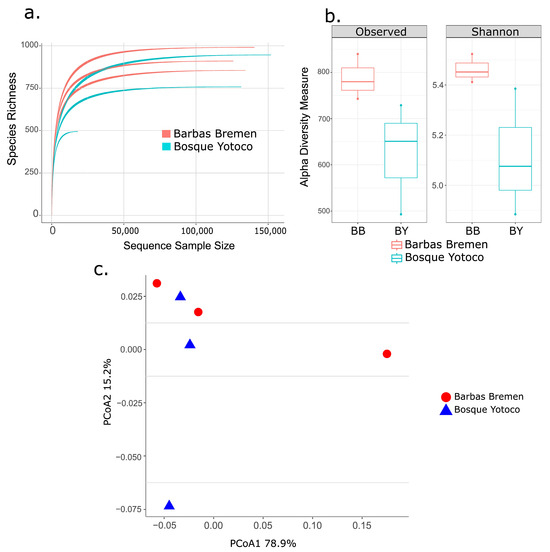

Overall, the samples from howler monkeys exhibit high diversity. The rarefaction curves reached the asymptote, indicating enough sampling depth (Figure 2a). Regarding alpha diversity, the observed ASV richness per sample closely aligns with the expected richness (mean: observed = 706, Chao1 = 787.6, ACE = 777.04). The Shannon index shows an average diversity of 5.28 ± 0.25. There are some differences in diversity between Barbas-Bremen (B) and Bosque-Yotoco (Y) (Figure 2b). In terms of beta diversity, the two axes of the PCoA analysis explain 94.1% of the variation in the data. The PCoA shows some separation between the microbial compositions of the two locations, particularly for Barbas Bremen (Figure 2c). However, this differentiation is not statistically significant according to the PERMANOVA test (R2 = 0.28, F = 1.58, p = 0.2).

Figure 2.

Measures of alpha and beta diversity in the microbiome of the howler monkey (Alouatta seniculus) in two Andean forests. (a). Rarefaction curve showing the number of readings per sample, Barbas Bremen samples are presented in red and Bosque Yotoco samples in cyan. (b). Shannon index (Alpha diversity) compared by locality Barbas Bremen samples are presented in red and Bosque Yotoco samples in cyan. (c). Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA, Beta diversity) of howler monkey samples distinguished by locality, based on UniFrac weighted distance.

3.2. Resistance Genes and Virulence Factors

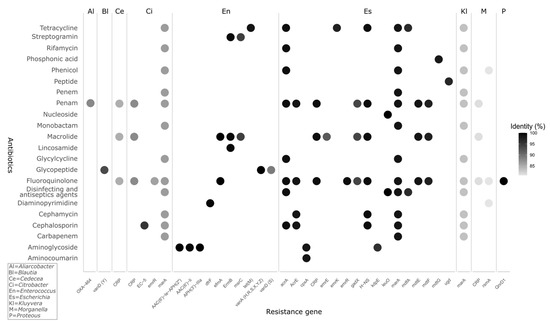

Nine bacterial genera harbor a total of forty-three antibiotic resistance genes with an identity threshold of ≥80%. The genera Escherichia and Enterococcus have the highest number of resistance genes, with 17 and 15 genes, respectively; also these two genera include the highest identity values ≥ 90%. These genes are related to resistance to twenty-two different antibiotics. The main antibiotics for which resistance is present are fluoroquinolones, macrolides, glycopeptides, and tetracyclines (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Antibiotics and percent identity of antimicrobial resistance genes (ARG) detected in the microbiome of the red howler monkey (Alouatta seniculus) from Colombian Andean forests, using the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database (CARD) for identification. Abbreviated genera in the top panel: Al = Aliarcobacter, Bl = Blautia, Ce = Cedecea, Ci = Citrobacter, En = Enterococcus, Es = Escherichia, Kl = Kluyvera, M = Morganella, P = Proteus. Percent identity is encoded by color (black, >95%; light gray, <85%). Candidate ARGs hits were initially screened at ≥80% identity to ensure sensitivity; for reporting/interpretation, only hits with ≥90% identity was retained to minimize false positives. Closely related alleles with similar identity conferring resistance to the same antibiotic class were grouped to avoid double counting.

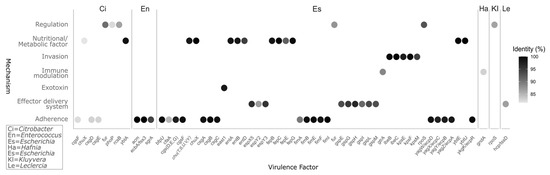

Six genera of bacteria contain virulent factors, totaling sixty-six genes with identity of over 80%, but only Escherichia, Enterococcus and one gene in Citrobacter had over 90% identity for virulence factors. These virulence genes were categorized into six mechanisms, with adherence being the most common, followed by metabolic factors. The genus Escherichia has the highest number of virulence factors, with fifty-two genes, followed by Enterococcus. Moreover, these two genera also share the highest values of identity, followed by Citrobacter, with only two genes ≥ 90% identity (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Mechanisms and percent identity of virulence factors (VF) detected in the microbiome of the red howler monkey (Alouatta seniculus) in Colombian Andean forests, using the virulence factor database (VFDB) for identification. Abbreviated genera in the top panel: Ci = Citrobacter, En = Enterococcus, Es = Escherichia, Ha = Hafnia, Kl = Kluyvera, Le = Leclercia. Gene identification used an initial identity screen ≥ 80% to ensure sensitivity; for reporting and interpretation, only calls with ≥90% identity were retained to minimize potential false positives. Closely related genes with highly similar identities and overlapping functional annotations were grouped to avoid redundancy.

3.3. Resistance Genes and Virulence Factors Associated with Plasmids

In the analysis of resistance genes and virulence factors associated with plasmids in the microbial community of A. seniculus, no virulence genes were found in plasmids with a score > 0.9 according to the PLASMe. However, eleven antibiotic resistance genes were identified in scaffolds classified as plasmid derived. These scaffolds were matched to the following reference sequences: NZ_CP047354.1 for the scaffold containing the qnrD1 gene, CP006623.1 for APH(3′)-IIa and ermB, NZ_CP066585.1 for AAC(6′)-Ie-APH(2″), and NZ_CP066662.1 for the vanA cluster (vanS, vanR, vanH, vanA, vanX, vanY, and vanZ). The first of these plasmids belongs to Proteus mirabilis, while the last three correspond to E. faecium plasmids.

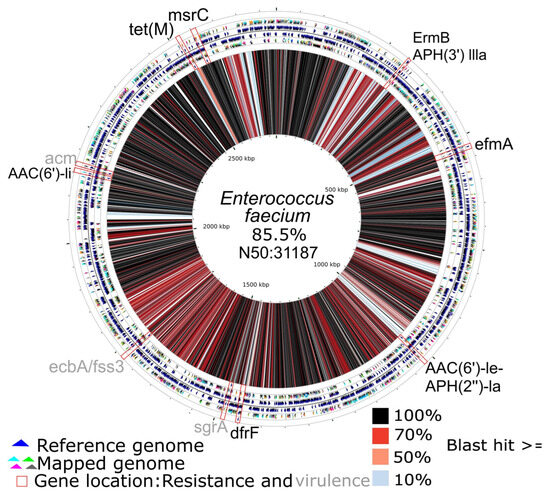

3.4. Genome Reconstruction

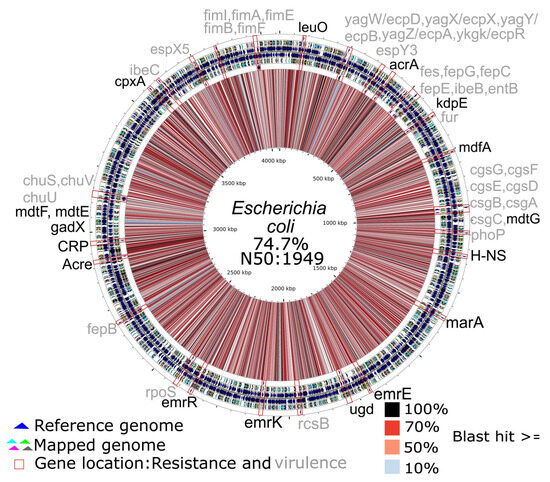

Two species from the ESKAPE group were reconstructed with a genome completeness exceeding 40% (Escherichia coli and Enterococcus faecium). In the reconstructed genome of E. faecium, seven antibiotic resistance genes were found, along with three genes related to virulence factors (Figure 5). On the other hand, in the mapped genome of E. coli, sixteen antibiotic resistance genes and thirty-five virulence genes were found (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Circular map of the Enterococcus faecium genome reconstructed from the pooled fecal metagenome of six A. seniculus individuals, aligned to the reference genome (GenBank: CP038996.1). From inner to outer: the reconstructed (mapped) genome, the reference genome, and the annotation track(s) displaying antimicrobial resistance genes (ARG) in blank and virulence factors (VF) in gray, identified in the mapped genome using the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database (CARD) and the virulence factor database (VFDB). The central similarity ring encodes pairwise identity between the reconstructed and reference genomes, where black = 100%, dark- to light-red = 98–50%, and blue to white = 49–0%.

Figure 6.

Circular map of the Escherichia coli genome reconstructed from the pooled fecal metagenome of six A. seniculus individuals, aligned to the E. coli K-12 reference (GenBank: U00096.3). From inner to outer: the reconstructed (mapped) genome, the reference genome, and the annotation track(s) with antimicrobial resistance genes (ARG) in black and virulence factors (VF) in gray, identified in the mapped genome using the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database (CARD) and the virulence factor database (VFDB). The central similarity ring shows identity between the reconstructed and reference genome: black = 100%, dark- to light-red = 98–50%, blue to white = 49–0%.

4. Discussion

The microbiome of wild howler monkeys in fragmented forests (see Figure 1) shows similarities to a population living in such an environment. The proportion of Pseudomonadota and Bacteroidota may differ between individuals of Alouatta pigra in captivity and those in fragmented forests [7]. This coincides with the results observed in the two evaluated locations. Additionally, the abundance of Bacillota (Firmicutes) and Pseudomonadota observed in this study is consistent with the microbiome composition reported for wild populations of Alouatta in different fragmented locations [6,7]. Culture methods have shown Pseudomonadota as the most prevalent phyla, followed by Bacillota (Firmicutes), Actinomycetota (Actinobacteria) and Bacteroidota (Bacteroidetes) in fragmented forest. However, since some Bacillota and other groups are anaerobic microorganisms, these methods may underestimate their abundance [48]. At the genus level, Ruminococcus (or Ruminococcaceae) has exhibited high relative abundance during periods of low food availability [7]. Therefore, these results suggest that the current environmental conditions in these locations may not provide optimal food resources. However, a larger sample size is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

The overall microbiome composition remains consistent across samples, with the exception of the Barbas-Bremen individual (B3). Bacteria of the genus Dysgonomonas are Gram-negative, facultative anaerobes widely distributed in terrestrial environments and arthropods, although they are also characterized in humans [49,50]. The B3 sample could have shown this individual difference due to the high consumption of lignocellulose, which Dysgonomonas helps digest, but it has also been reported that they occasionally eat soil and termites, with Dysgonomonas present in these environments as another possible explanation for this result [51]. In contrast, sample B3 showed a low abundance of Oscillospiraceae compared to the others. Oscillospiraceae bacteria degrade cellulose or hemicellulose, contributing to the digestion of plant fibers. The individual difference observed in B3 could be related to consumption of higher-lignin material or occasional ingestion of termites and soil [52].

The microbiome of howler monkeys (see Figure 2) is diverse and does not differ between the two locations. However, when comparing forests with distinct levels of human intervention, the specific richness can vary by up to six times [7]. Our study found consistent richness and beta diversity, indicating a possible similar environment for howler monkeys. In contrast to a study on A. pigra, using culture methods which found differences in microbial diversity between individuals from flooded and non-flooded areas which could limit movement [48], the diversity indices remained high and constant between samples. In other primates, microbiomes characterized by 16S reach similar diversities to those found in our study in wild populations, compared to captive and semi-captive [53]. In A. pigra, a Shannon index of up to 5.17 ± 0.31 has been reported during periods of high food availability. These values are comparable to our results [6]. Therefore, the diversity and composition of the howler monkey microbiome in the two locations does not appear to be affected by diets other than their natural ones; however, as this is an exploratory study, with our sample size, it is not possible to determine a clear difference between the two locations.

Antibiotic resistance in Alouatta seniculus

In howler monkeys, bacteria genera of zoonotic interest that contain antibiotic resistance genes with high identity were found (see Figure 3). The genus Escherichia has the largest number of resistance genes. This genus has been extensively studied, particularly E. coli and its resistance genes [54,55]. Most of the resistance found is directed toward fluoroquinolone antibiotics and macrolides, similar to other vertebrates [54,56]. However, the resistome differs from that in previous studies on the genus Alouatta, particularly in terms of sulfonamide resistance [17,19]. Other antibiotics with a considerable presence of resistance genes include glycopeptides, tetracyclines, and beta-lactams. Studies in wild populations of chimpanzees with variable human interaction have found tetracycline resistance genes [57]; tetracycline resistance has also been reported in A. pigra in fragmented forest with possible contact with domestic animals, but this resistance was related to tet(B) gene, different from tet(M) found in A. seniculus. Furthermore, while beta-lactam resistance was not reported in A. pigra, a gene associated with cephalosporin resistance, EC-5 was identified in A. seniculus in this study [17]. Additionally, resistance to aminoglycosides, penicillin, and fluoroquinolones has been found in E. faecium isolates from wild animals [58]. Resistance to glycopeptides, such as the vancomycin-related vanA cluster, along with the genes tet(M), erm(B), and aph(3′)-IIIa related to resistance to tetracyclines, macrolides, and aminoglycosides, respectively, have been detected in fecal samples of wild wolves and Iberian lynx, with tet(M) gene being the most common gene associated with tetracycline resistance in Enterococcus isolates found in animals and environmental sources [59,60].

In the case of E. coli (see Figure 3 and Figure 6), most of the identified genes are associated with the Efflux pump mechanism, including acrA and acrE homologs, which are part of the AcrAB-TolC, an intrinsic resistance system regulated by marA, and marA-like genes are widely distributed among bacteria. In addition to conferring antibiotic resistance, this system plays a crucial role in tolerating highly acidic environments, such as those found in the stomach [61,62,63]. The mdtG gene is associated with fosfomycin resistance when overexpressed [64]. The mdtE and mdtF genes constitute an efflux pump system regulated by multiple factors. This system is activated by regulators such as gadX, providing resistance to various antibiotics and acidic conditions. In contrast, CRP and H-NS function as repressors of mdtEF; however, their inhibitory activity is suppressed under anaerobic or highly acidic environments [65,66,67]. The gene CRP is a global transcription factor; mutations in CRP have been associated with increased resistance to various antibiotics [67,68], and this regulator has been identified in Citrobacter isolates [69] as well as in strains of Morganella morganii [70]. However, it has not yet been reported in Cedecea, although resistance studies in this genus remain limited [71]. Similarly, the emrR gene acts as a negative regulator of efflux pump mechanisms. Mutations in this gene can increase the expression of the emrAB–tolC complex in E. coli, thereby enhancing its functionality. This gene has also been reported in Citrobacter and other Enterobacteriaceae [72,73]. It is worth noting the presence of the leuO gene, which is antagonistic to genes such as H-NS [74]. The mdfA gene, which is associated with alkaline resistance in E. coli, is also part of the highly conserved and intrinsic efflux pump mechanisms. Genome annotation of the E. coli K-12 strain has identified up to 36 known efflux pumps [75]. Our results regarding resistance genes seem to indicate that resistance to these same antibiotics has been found in wildlife before and the relationship with human activity of these genes are variable mainly in Enterococcus, while many genes related to efflux pump are intrinsic of enterobacteria, in Escherichia, these genes are related to its ability to survive in the digestive system but additionally contribute to the antibiotic resistance of this microorganism under the conditions of the digestive tract.

Virulence genes of the Alouatta seniculus microbiome

E. coli was found to have the highest number of virulence factors (see Figure 4 and Figure 6) in A. seniculus microbiome, including the chu operon which allows the organism to obtain iron from the host’s hemoglobin. The chu operon enables iron acquisition from host hemoglobin, with chuUVW genes being more prevalent among strains than chuTX. All genes, except chuW, are present in Escherichia. In this operon, chuX functions as part of the iron transport system in E. coli, with homologs found in other Enterobacteriaceae [76,77]. Genes related to iron acquisition, such as chu, have also been identified in Citrobacter [78]. Other localized virulence factors in E. coli include csg, related to the formation of curli fibers and biofilms [76,79]. The csgF gene is essential for anchoring proteins involved in curli fiber biogenesis in enteric bacteria such as Salmonella and E. coli, while csgD regulates this process and csgE is required for attachment. Similar proteins or orthologs may also be present in Citrobacter, as csgF and csgE have been identified in some C. werkmanii strains, and other curli-related genes have been reported in Citrobacter spp. [80,81,82].

Another gene associated with iron acquisition, fur, is present in both Citrobacter and Escherichia (see Figure 4). The gene fur functions as an iron-dependent regulatory protein. These proteins are present in most bacterial species except for Gram-positive bacteria with high GC content, with the presence of this gene likely being intrinsic in these bacteria [83,84].

The rpoS gene has been identified in the Escherichia. It is crucial in regulating gene transcription in response to stress in most γ-proteobacteria, having some core conserved functions [85,86].

The fim gene, related to fimbriae formation for adhesion, along with ibeC, related to invasion into host tissues, has been reported in enteropathogenic strains of E. coli [79]. Other virulence factors found in E. coli include yag/ecp, related to pilus formation, and fepGCE, related to iron transporters [76]. Additionally, a gene related to the generation of enterotoxins was found. The gene east1 is a small peptide of thirty-eight amino acids, found in enteropathogenic E. coli strains associated with diarrhea in humans and animals, although its function is not fully understood [87,88]. These results suggest the environmental presence of E. coli strains with virulence factors in the fecal samples of A. seniculus, exhibiting a wide range of mechanisms, from adhesion to enterotoxin production. Although other functional traits related to virulence factors, mainly metabolism-oriented, may be present in this microbiome, we did not evaluate them systematically in this study. Future work will prioritize targeted, metabolism-oriented annotation to test whether these functions are indeed associated with virulence.

In the Enterococcus genus (see Figure 4 and Figure 5), three virulence factors related to the adhesion mechanism were identified. These include acm, which is associated with collagen adhesion. A superficial adhesin LPXTG binds to the nidogen sgrA gene and the Fss3 gene, responsible for binding to fibrinogen and collagen for initiating infection. These factors have been reported in E. faecium and E. faecalis [89].

Analysis of resistance genes and virulence factors associated with plasmids

In our study, we identified eleven resistance genes associated with plasmids. However, no virulence factors were found to be plasmid-related. The vanA cluster genes, which are responsible for glycopeptide resistance such as vancomycin, have been found in plasmids in both hospitalized patients and farm animals infected with E. faecium. These resistance genes have also been reported in plasmids [90].

The AAC(6′)-Ie-APH(2″) gene is usually associated with plasmids and has been identified as part of the Tn5281 transposon. Additionally, a relationship has been observed between vanA vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus and Tn5281 [91]. ErmB plasmids have been observed in E. faecium isolates from patients and have also been associated with transposons [92]. Similarly, APH(3′)-IIIa has been in plasmids and transposons [93].

Although tet(M) (see Figure 5) was not located in plasmids in our results, its presence has been documented in both chromosomes and plasmids, and it has been associated with transposons [94]. It is important to note that our genome reconstruction method relies heavily on the reference genome and the resistance and virulence genes present in the reference. Therefore, more in-depth studies are necessary to confirm this result, particularly when this result comes from a pool of several individuals and some of these genes may be present in both the chromosome and plasmids. The qnrd1 gene is the only plasmid-associated resistance gene not related to E. faecium, but it has been related to the genus Proteus. QnrD-positive isolates have been associated with small plasmids and are widespread throughout much of the world [95].

Our results indicate that some resistance genes are present in plasmids within the microbiome of A. seniculus, but they do not appear to be shared among different genera in the community. This could be attributed to low antibiotic pressure, which may not drive horizontal transfer between genera. However, our results are limited to the presence of these genes in plasmids; therefore, the possibility of gene transfer in the microbiome of A. seniculus is not supported by direct evidence.

Limitations

Despite the novel insights provided by this study, limitations must be acknowledged. First, the small sample size (n = 6) limits the statistical power of our analyses and restricts our ability to draw definitive conclusions about microbiome variation between locations. Furthermore, the shotgun metagenomic analysis was performed on a pooled sample, which prevents the identification of individual-specific contributions or differences by their location. In addition, since this study is a pilot, capturing or manipulating wild individuals was not desirable. However, tracking and monitoring alone did not allow for the determination of the sex and age of the individuals, which may introduce variability, as these factors can influence gut microbiota composition. Future studies with larger, well-characterized samples and individual-based metagenomic analyses will be crucial to validate and expand upon these preliminary findings.

5. Conclusions

The howler monkey (Alouatta seniculus) harbors a diverse microbiome influenced by its diet and exhibits resistance genes to certain antibiotics, such as fluoroquinolones and macrolides. The observed composition and diversity suggest that the two studied locations provide a similar environment for this primate. However, some individuals show signs of limited food availability, but a larger sample size is needed to confirm this observation. Given the importance of forests as conservation units, monitoring the howler monkey microbiome can serve as a valuable tool for assessing the effectiveness of conservation measures. Additionally, enhancing pathogen surveillance is crucial due to the environmental presence of microorganisms carrying antibiotic resistance genes and virulence factors, such as Enterococcus and Escherichia, genera which include potentially enteropathogenic microorganisms. Although antibiotic resistance in howler monkeys appears to be primarily associated with intrinsic bacterial mechanisms and natural antibiotic resistance, and there is no evidence of horizontal gene transfer, further studies are needed to assess the potential impact of human activities. Therefore, we propose expanding microbiome and resistome studies of Alouatta species across multiple Colombian forests with varying degrees of human intervention, including presence of domestic animals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C. and D.L.-A.; methodology, A.P.-M., A.F., H.F.-R. and M.P.; software, A.P.-M., A.F., H.F.-R. and J.P.A.M.; validation, A.C. and D.L.-A.; formal analysis, A.P.-M. and A.F.; investigation, A.P.-M. and A.F.; resources, N.R.-D.; data curation, A.F.; writing—original draft preparation, A.F. and A.P.-M.; writing—review and editing, A.C. and D.L.-A.; visualization, A.P.-M. and A.F.; supervision, A.C. and D.L.-A.; project administration, A.C.; funding acquisition, A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Vice-Rector at Universidad del Valle, which provided financial support for the research, grant number (CI 71335).

Data Availability Statement

The raw sequencing data from metabarcoding and metagenomic analyses presented in this study are available in online repositories. The repository name and accession numbers are provided below: NCBI SRA, project PRJNA1190078—SRR31480689, SRR31480691, SRR31480688, SRR31480690, SRR31480687, and SRR31480686 for microbiome data, and SRR31480663 for metagenomic raw data, reviewer link https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA1190078?reviewer=ub5o2fcsup7hnu02mo5064dj3l (accessed on 24 November 2024).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the members of the Biological Diversity Research Group at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Palmira campus, for their technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| rRNA | ribosomal RNA |

| ASV | Amplicon Sequence Variant |

| VF | Virulence Factor |

| ARG | Antibiotic Resistance Genes |

| CARD | Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database |

| ESKAPE | Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterobacter spp. |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

References

- Clayton, J.B.; Gomez, A.; Amato, K.; Knights, D.; Travis, D.A.; Blekhman, R.; Knight, R.; Leigh, S.; Stumpf, R.; Wolf, T.; et al. The Gut Microbiome of Nonhuman Primates: Lessons in Ecology and Evolution. Am. J. Primatol. 2018, 80, e22867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moy, M.; Diakiw, L.; Amato, K.R. Human-Influenced Diets Affect the Gut Microbiome of Wild Baboons. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuzak, J.A.; Zevin, A.S.; Cheu, R.; Richardson, B.; Modesitt, J.; Hensley-McBain, T.; Miller, C.; Gustin, A.T.; Coronado, E.; Gott, T.; et al. Antibiotic-Induced Microbiome Perturbations Are Associated with Significant Alterations to Colonic Mucosal Immunity in Rhesus Macaques. Mucosal Immunol. 2020, 13, 471–480, Erratum in Mucosal Immunol. 2020, 13, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolt, L.; Hadley, C.; Schreier, A. Crowded in a Fragment: High Population Density of Mantled Howler Monkeys (Alouatta palliata) in an Anthropogenically-Disturbed Costa Rican Rainforest. Primate Conserv. 2022, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Posada, C.; Londoño, J.M. Alouatta seniculus: Density, Home Range and Group Structure in a Bamboo Forest Fragment in the Colombian Andes. Folia Primatol. 2012, 83, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, K.R.; Leigh, S.R.; Kent, A.; Mackie, R.I.; Yeoman, C.J.; Stumpf, R.M.; Wilson, B.A.; Nelson, K.E.; White, B.A.; Garber, P.A. The Gut Microbiota Appears to Compensate for Seasonal Diet Variation in the Wild Black Howler Monkey (Alouatta pigra). Microb. Ecol. 2015, 69, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, K.R.; Yeoman, C.J.; Kent, A.; Righini, N.; Carbonero, F.; Estrada, A.; Rex Gaskins, H.; Stumpf, R.M.; Yildirim, S.; Torralba, M.; et al. Habitat Degradation Impacts Black Howler Monkey (Alouatta pigra) Gastrointestinal Microbiomes. ISME J. 2013, 7, 1344–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahrndorff, S.; Alemu, T.; Alemneh, T.; Lund Nielsen, J. The Microbiome of Animals: Implications for Conservation Biology. Int. J. Genom. 2016, 2016, 5304028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laborda, P.; Sanz-García, F.; Ochoa-Sánchez, L.E.; Gil-Gil, T.; Hernando-Amado, S.; Martínez, J.L. Wildlife and Antibiotic Resistance. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 873989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbehang Nguema, P.P.; Onanga, R.; Ndong Atome, G.R.; Tewa, J.J.; Mabika Mabika, A.; Muandze Nzambe, J.U.; Obague Mbeang, J.C.; Bitome Essono, P.Y.; Bretagnolle, F.; Godreuil, S. High Level of Intrinsic Phenotypic Antimicrobial Resistance in Enterobacteria from Terrestrial Wildlife in Gabonese National Parks. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarżyńska, M.; Leekitcharoenphon, P.; Hendriksen, R.S.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Wasyl, D. A Metagenomic Glimpse into the Gut of Wild and Domestic Animals: Quantification of Antimicrobial Resistance and More. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmann, M.; Vehreschild, M.J.G.T.; Biehl, L.M.; Vogel, W.; Dörfel, D.; Hamprecht, A.; Seifert, H.; Autenrieth, I.B.; Peter, S. Distinct Impact of Antibiotics on the Gut Microbiome and Resistome: A Longitudinal Multicenter Cohort Study. BMC Biol. 2019, 17, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Xu, F.; Wang, H.; Xiong, W.; Li, X. Metagenomic Insights into the Antibiotic Resistomes of Typical Chinese Dairy Farm Environments. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 990272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Fan, P.; Liu, T.; Yang, A.; Boughton, R.K.; Pepin, K.M.; Miller, R.S.; Jeong, K.C. Transmission of Antibiotic Resistance at the Wildlife-Livestock Interface. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezeau, N.; Kahn, L. Current Understanding and Knowledge Gaps Regarding Wildlife as Reservoirs of Antimicrobial Resistance. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2024, 85, ajvr.24.02.0040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, G.K.; Boerlin, P.; Janecko, N.; Reid-Smith, R.J.; Jardine, C. Antimicrobial Resistance in Escherichia coli Isolates from Swine and Wild Small Mammals in the Proximity of Swine Farms and in Natural Environments in Ontario, Canada. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez-Aguilar, A.A.; Toledo-Manuel, F.O.; Barbachano-Guerrero, A.; Hernández-Rodríguez, D. Detection of Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in Escherichia coli Isolated from Black Howler Monkeys (Alouatta pigra) and Domestic Animals in Fragmented Rain-Forest Areas in Tabasco, Mexico. J. Wildl. Dis. 2020, 56, 922–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegner, C.; Sunil-Chandra, N.P.; Wijesooriya, W.R.P.L.I.; Perera, B.V.; Hansson, I.; Fahlman, Å. Detection, Identification, and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Campylobacter spp. and Salmonella spp. from Free-Ranging Nonhuman Primates in Sri Lanka. J. Wildl. Dis. 2019, 55, 879–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristóbal-Azkarate, J.; Dunn, J.C.; Day, J.M.W.; Amábile-Cuevas, C.F. Resistance to Antibiotics of Clinical Relevance in the Fecal Microbiota of Mexican Wildlife. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e107719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Restrepo, S.; Montilla, S.O. Taxonomy of the Primates of Colombia: Changes in the Last Twenty Years (2000–2019) and Annotations on Type Localities. Neotrop. Mammal. 2021, 28, 584. [Google Scholar]

- Leal, S.A.Z.; Defler, T.R. Sympatric Distribution of Two Species of Alouatta (A. seniculus and A. palliata: Primates) in Chocó, Colombia. Neotrop. Primates 2013, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, A.C.; Vélez, A.; Gómez-Posada, C.; López, H.; Zárate, D.A.; Stevenson, P.R. Use of Space, Activity Patterns, and Foraging Behavior of Red Howler Monkeys (Alouatta seniculus) in an Andean Forest Fragment in Colombia. Am. J. Primatol. 2011, 73, 1062–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechner, A. Searching for Alouatta palliata in Northern Colombia: Considerations for the Species Detection, Monitoring and Conservation in the Dry Forests of Bolívar, Colombia. Neotrop. Primates 2011, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaño Ospina, K. Aspectos Ecológicos de Diez Especies Pioneras Arbóreas en Corredores de Conexión Barbas-Bremen. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad del Quindío, Armenia, Colombia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Salinas, F.; López-Aranda, F. Las Carreteras Pueden Restringir El Movimiento de Pequeños Mamíferos En Bosques Andinos de Colombia? Estudio de Caso En El Bosque de Yotoco, Valle Del Cauca. Caldasia 2012, 34, 409–420. [Google Scholar]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, Interactive, Scalable and Extensible Microbiome Data Science Using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857, Erratum in Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magoč, T.; Salzberg, S.L. FLASH: Fast Length Adjustment of Short Reads to Improve Genome Assemblies. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2957–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA Ribosomal RNA Gene Database Project: Improved Data Processing and Web-Based Tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. Phyloseq: An R Package for Reproducible Interactive Analysis and Graphics of Microbiome Census Data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahti, L.; Shetty, S. Microbiome R Package; Bioconductor: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahti, L.; Shetty, S. Tools for Microbiome Analysis in R. Version 2.1.28; 2017–2020. Available online: http://microbiome.github.com/microbiome (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Szoecs, E.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. R Package Version 2.8-0; 2025. Available online: https://vegandevs.github.io/vegan/ (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List, 2024: Bacterial Pathogens of Public Health Importance to Guide Research, Development and Strategies to Prevent and Control Antimicrobial Resistance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- Hahsler, M.; Nagar, A. rBLAST: R Interface for the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. Bioconductor Version: Release (3.19); R Package Version 0.99.4; 2024. Available online: https://doi.org/10.18129/B9.bioc.rBLAST (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Prjibelski, A.; Antipov, D.; Meleshko, D.; Lapidus, A.; Korobeynikov, A. Using SPAdes De Novo Assembler. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2020, 70, e102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurk, S.; Meleshko, D.; Korobeynikov, A.; Pevzner, P. MetaSPAdes: A New Versatile Metagenomic Assembler. Genome Res. 2017, 27, 824–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, B.; Raphenya, A.R.; Alcock, B.; Waglechner, N.; Guo, P.; Tsang, K.K.; Lago, B.A.; Dave, B.M.; Pereira, S.; Sharma, A.N.; et al. CARD 2017: Expansion and Model-Centric Curation of the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D566–D573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zheng, D.; Liu, B.; Yang, J.; Jin, Q. VFDB 2016: Hierarchical and Refined Dataset for Big Data Analysis—10 Years On. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D694–D697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.E.; Lu, J.; Langmead, B. Improved Metagenomic Analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitwieser, F.P.; Salzberg, S.L. Pavian: Interactive Analysis of Metagenomics Data for Microbiome Studies and Pathogen Identification. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 1303–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Rincon, N.; Wood, D.E.; Breitwieser, F.P.; Pockrandt, C.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L.; Steinegger, M. Author Correction: Metagenome Analysis Using the Kraken Software Suite. Nat. Protoc. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H. Minimap2: Pairwise Alignment for Nucleotide Sequences. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 3094–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danecek, P.; Bonfield, J.K.; Liddle, J.; Marshall, J.; Ohan, V.; Pollard, M.O.; Whitwham, A.; Keane, T.; McCarthy, S.A.; Davies, R.M.; et al. Twelve Years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience 2021, 10, giab008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwengers, O.; Jelonek, L.; Dieckmann, M.A.; Beyvers, S.; Blom, J.; Goesmann, A. Bakta: Rapid and Standardized Annotation of Bacterial Genomes via Alignment-Free Sequence Identification. Microb. Genom. 2021, 7, 000685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.R.; Arantes, A.S.; Stothard, P. Comparing Thousands of Circular Genomes Using the CGView Comparison Tool. BMC Genom. 2012, 13, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.; Shang, J.; Ji, Y.; Sun, Y. PLASMe: A Tool to Identify PLASMid Contigs from Short-Read Assemblies Using Transformer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, e83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Feria, L.; Aguilar-Faisal, J.; Pastor-Nieto, R.; Serio-Silva, J. Changes in vegetation at small landscape scales and captivity alter the gut microbiota of black howler monkeys (Alouatta pigra: Atelidae) Cambios En La Vegetación a Pequeñas Escalas de Paisaje y El Cautiverio Alteran La Microbiota Intestinal de Los Monos Aulladores Negros (Alouatta pigra: Atelidae). Acta Biológica Colomb. 2023, 28, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilen, M.; Fonkou, M.D.M.; Dubourg, G.; Tomei, E.; Richez, M.; Delerce, J.; Levasseur, A.; Daoud, Z.; Raoult, D.; Cadoret, F. Dysgonomonas massiliensis sp. nov., a New Species Isolated from the Human Gut and Its Taxonogenomic Description. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2019, 112, 935–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Wang, S.; Wu, Y.; Sun, J.; Zhao, F. Seasonal Dynamics of Intestinal Microbiota in Juvenile Chinese Mitten Crab (Eriocheir sinensis) in the Yangtze Estuary. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1436547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izawa, K. Soil-Eating by Alouatta and Ateles. Int. J. Primatol. 1993, 14, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, L.; Wen, X.; Jia, T.; Han, J.; Qin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z. Comparative Study of the Gut Microbiota in Three Captive Rhinopithecus Species. BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, J.B.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Long, H.T.; Tuan, B.V.; Cabana, F.; Huang, H.; Vangay, P.; Ward, T.; Minh, V.V.; Tam, N.A.; et al. Associations Between Nutrition, Gut Microbiome, and Health in A Novel Nonhuman Primate Model. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.; Qu, Q.; Wang, M.; Huang, M.; Zhou, W.; Wei, F. Global Landscape of Gut Microbiome Diversity and Antibiotic Resistomes across Vertebrates. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vittecoq, M.; Godreuil, S.; Prugnolle, F.; Durand, P.; Brazier, L.; Renaud, N.; Arnal, A.; Aberkane, S.; Jean-Pierre, H.; Gauthier-Clerc, M.; et al. Antimicrobial Resistance in Wildlife. J. Appl. Ecol. 2016, 53, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Li, H.; Fayyaz, A.; Gai, Y. Metagenomic and Network Analysis Revealed Wide Distribution of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Monkey Gut Microbiota. Microbiol. Res. 2022, 254, 126895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsons, M.B.; Travis, D.A.; Lonsdorf, E.V.; Lipende, I.; Elchoufi, D.; Gilagiza, B.; Collins, A.; Kamenya, S.; Tauxe, R.V.; Gillespie, T.R. Antimicrobial Resistance Creates Threat to Chimpanzee Health and Conservation in the Wild. Pathogens 2021, 10, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trościańczyk, A.; Nowakiewicz, A.; Osińska, M.; Łagowski, D.; Gnat, S.; Chudzik-Rząd, B. Comparative Characteristics of Sequence Types, Genotypes and Virulence of Multidrug-Resistant Enterococcus Faecium Isolated from Various Hosts in Eastern Poland. Spread of Clonal Complex 17 in Humans and Animals. Res. Microbiol. 2022, 173, 103925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.; Barrett, J.B.; Frye, J.G.; Jackson, C.R. Antimicrobial Resistance Gene Detection and Plasmid Typing Among Multidrug Resistant Enterococci Isolated from Freshwater Environment. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, A.; Igrejas, G.; Radhouani, H.; López, M.; Guerra, A.; Petrucci-Fonseca, F.; Alcaide, E.; Zorrilla, I.; Serra, R.; Torres, C.; et al. Detection of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci from Faecal Samples of Iberian Wolf and Iberian Lynx, Including Enterococcus Faecium Strains of CC17 and the New Singleton ST573. Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 410–411, 266–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, C.; Levy Stuart, B. Many Chromosomal Genes Modulate MarA-Mediated Multidrug Resistance in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 2125–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffner, S.H.; Lee, A.V.; Pham, M.T.N.; Kassaye, B.B.; Li, H.; Tallada, S.; Lis, C.; Lang, M.; Liu, Y.; Ahmed, N.; et al. Extreme Acid Modulates Fitness Trade-Offs of Multidrug Efflux Pumps MdtEF-TolC and AcrAB-TolC in Escherichia coli K-12. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e00724-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.E.; Blair, J.M.A. Redundancy in the Periplasmic Adaptor Proteins AcrA and AcrE Provides Resilience and an Ability to Export Substrates of Multidrug Efflux. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014, 69, 982–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fàbrega, A.; Martin Robert, G.; Rosner Judah, L.; Tavio, M. Mar; Vila Jordi Constitutive SoxS Expression in a Fluoroquinolone-Resistant Strain with a Truncated SoxR Protein and Identification of a New Member of the marA-soxS-Rob Regulon, mdtG. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 1218–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Shan, Y.; Pan, Q.; Gao, X.; Yan, A. Anaerobic Expression of the gadE-mdtEF Multidrug Efflux Operon Is Primarily Regulated by the Two-Component System ArcBA through Antagonizing the H-NS Mediated Repression. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 55557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanelli, G.; Pasqua, M.; Colonna, B.; Prosseda, G.; Grossi, M. Expression Profile of Multidrug Resistance Efflux Pumps During Intracellular Life of Adherent-Invasive Escherichia coli Strain LF82. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishino, K.; Senda, Y.; Yamaguchi, A.; Nishino, K.; Yamaguchi, A.; Nishino, K.; Yamaguchi, A. The AraC-Family Regulator GadX Enhances Multidrug Resistance in Escherichia coli by Activating Expression of mdtEF Multidrug Efflux Genes. J. Infect. Chemother. 2008, 14, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishino, K.; Senda, Y.; Yamaguchi, A. CRP Regulator Modulates Multidrug Resistance of Escherichia coli by Repressing the mdtEF Multidrug Efflux Genes. J. Antibiot. 2008, 61, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghembe, R.S.; Magulye, M.A.K.; Eilu, E.; Sekyanzi, S.; Makaranga, A.; Mwesigwa, S.; Katagirya, E. A Sophisticated Virulence Repertoire and Colistin Resistance of Citrobacter Freundii ST150 from a Patient with Sepsis Admitted to ICU in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Uganda, East Africa: Insight from Genomic and Molecular Docking Analyses. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2024, 120, 105591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, D.U.; Dixit, S.; Gaur, M.; Mishra, R.; Sahoo, R.K.; Sahoo, M.; Behera, B.K.; Subudhi, B.B.; Bharat, S.S.; Subudhi, E. Sequencing and Characterization of M. Morganii Strain UM869: A Comprehensive Comparative Genomic Analysis of Virulence, Antibiotic Resistance, and Functional Pathways. Genes 2023, 14, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.K.; Sharkady, S.M. Expanding Spectrum of Opportunistic Cedecea Infections: Current Clinical Status and Multidrug Resistance. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 100, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerek, Á.; Török, B.; Laczkó, L.; Kardos, G.; Bányai, K.; Somogyi, Z.; Kaszab, E.; Bali, K.; Jerzsele, Á. In Vitro Microevolution and Co-Selection Assessment of Florfenicol Impact on Escherichia coli Resistance Development. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap, P.S.X.; Ahmad Kamar, A.; Chong, C.W.; Yap, I.K.S.; Teh, C.S.J. Whole Genome Analysis of Multidrug-Resistant Citrobacter Freundii B9-C2 Isolated from Preterm Neonate’s Stool in the First Week. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020, 21, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, T.; Bridier, A.; Briandet, R.; Ishihama, A. Novel Roles of LeuO in Transcription Regulation of E. coli Genome: Antagonistic Interplay with the Universal Silencer H-NS. Mol. Microbiol. 2011, 82, 378–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teelucksingh, T.; Thompson, L.K.; Cox, G. The Evolutionary Conservation of Escherichia coli Drug Efflux Pumps Supports Physiological Functions. J. Bacteriol. 2020, 202, e00367-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Sánchez, J.R.; Valdez-Torres, J.B.; del Campo, N.C.; Martínez-Urtaza, J.; del Campo, N.C.; Lee, B.G.; Quiñones, B.; Chaidez-Quiroz, C. Phylogenetic Group and Virulence Profile Classification in Escherichia coli from Distinct Isolation Sources in Mexico. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2022, 106, 105380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, D.; Nguyen, P.T.; Bourgault, S.; Couture, M. The Heme Binding Protein ChuX Is a Regulator of Heme Degradation by the ChuS Protein in Escherichia coli O157:H7. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2024, 256, 112575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Yin, Z.; Wang, J.; Qian, C.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, L.; Liu, B. Comparative Genomic Analysis of Citrobacter and Key Genes Essential for the Pathogenicity of Citrobacter Koseri. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarowska, J.; Futoma-Koloch, B.; Jama-Kmiecik, A.; Frej-Madrzak, M.; Ksiazczyk, M.; Bugla-Ploskonska, G.; Choroszy-Krol, I. Virulence Factors, Prevalence and Potential Transmission of Extraintestinal Pathogenic Escherichia coli Isolated from Different Sources: Recent Reports. Gut Pathog. 2019, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swasthi, H.M.; Basalla, J.L.; Dudley, C.E.; Vecchiarelli, A.G.; Chapman, M.R. Cell Surface-Localized CsgF Condensate Is a Gatekeeper in Bacterial Curli Subunit Secretion. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. Prevalence of Curli Genes among Cronobacter Species and Their Roles in Biofilm Formation and Cell-Cell Aggregation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018, 265, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Sánchez, J.R.; Quiñones, B.; Ortiz-Muñoz, J.A.; Prieto-Alvarado, R.; Vega-López, I.F.; Martínez-Urtaza, J.; Lee, B.G.; Chaidez, C. Comparative Genomic Analyses of Virulence and Antimicrobial Resistance in Citrobacter Werkmanii, an Emerging Opportunistic Pathogen. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertrand, R.L. Lag Phase-Associated Iron Accumulation Is Likely a Microbial Counter-Strategy to Host Iron Sequestration: Role of the Ferric Uptake Regulator (Fur). J. Theor. Biol. 2014, 359, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botta, A.; Barra, N.G.; Lam, N.H.; Chow, S.; Pantopoulos, K.; Schertzer, J.D.; Sweeney, G. Iron Reshapes the Gut Microbiome and Host Metabolism. J. Lipid Atheroscler. 2021, 10, 160–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schellhorn, H.E. Function, Evolution, and Composition of the RpoS Regulon in Escherichia coli. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 560099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, S.M.; Schellhorn, H.E. Evolution of the RpoS Regulon: Origin of RpoS and the Conservation of RpoS-Dependent Regulation in Bacteria. J. Mol. Evol. 2010, 70, 557–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubreuil, J.D. EAST1 Toxin: An Enigmatic Molecule Associated with Sporadic Episodes of Diarrhea in Humans and Animals. J. Microbiol. 2019, 57, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.E.; Souza, T.B.; Silva, N.P.; Scaletsky, I.C. Detection and Genetic Analysis of the Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli Heat-Stable Enterotoxin (EAST1) Gene in Clinical Isolates of Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) Strains. BMC Microbiol. 2014, 14, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agius, J.E.; Phalen, D.N.; Rose, K.; Eden, J.-S. Genomic Insights Into the Pathogenicity of a Novel Biofilm-Forming Enterococcus sp. Bacteria (Enterococcus lacertideformus) Identified in Reptiles. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 635208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arredondo-Alonso, S.; Top, J.; McNally, A.; Puranen, S.; Pesonen, M.; Pensar, J.; Marttinen, P.; Braat, J.C.; Rogers, M.R.C.; van Schaik, W.; et al. Plasmids Shaped the Recent Emergence of the Major Nosocomial Pathogen Enterococcus Faecium. mBio 2020, 11, e03284-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simjee, S.; White, D.G.; McDermott, P.F.; Wagner, D.D.; Zervos, M.J.; Donabedian, S.M.; English, L.L.; Hayes, J.R.; Walker, R.D. Characterization of Tn1546 in Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus Faecium Isolated from Canine Urinary Tract Infections: Evidence of Gene Exchange between Human and Animal Enterococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002, 40, 4659–4665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, Y.; Suzuki, M.; Kobayashi, S.; Hirahara, Y.; Kurushima, J.; Hirakawa, H.; Nomura, T.; Tanimoto, K.; Tomita, H. Enterococcal Linear Plasmids Adapt to Enterococcus Faecium and Spread within Multidrug-Resistant Clades. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2023, 67, e01619-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woegerbauer, M.; Zeinzinger, J.; Springer, B.; Hufnagl, P.; Indra, A.; Korschineck, I.; Hofrichter, J.; Kopacka, I.; Fuchs, R.; Steinwider, J.; et al. Prevalence of the Aminoglycoside Phosphotransferase Genes Aph(3′)-IIIa and Aph(3′)-IIa in Escherichia coli, Enterococcus faecalis, Enterococcus faecium, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica and Staphylococcus aureus Isolates in Austria. J. Med. Microbiol. 2014, 63, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huys, G.; D’Haene, K.; Collard, J.-M.; Swings, J. Prevalence and Molecular Characterization of Tetracycline Resistance in Enterococcus Isolates from Food. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 1555–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girlich, D.; Bonnin, R.A.; Dortet, L.; Naas, T. Genetics of Acquired Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Proteus spp. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).