Abstract

An ethnobotanical survey in the northern mountainous region of Vietnam identified four Elsholtzia species, E. blanda, E. ciliata, E. communis, and E. penduliflora, growing naturally above 1500 m and traditionally used by local ethnic communities to treat skin-related ailments. This study investigates their essential oil possible chemotypes, antimicrobial properties, and potential mechanisms of action through molecular docking. Essential oils obtained by steam distillation were analyzed using GC–MS. E. blanda (yield 1.17%) was characterized by high levels of 1,8-cineole (29.0%) and camphor (17.0%). E. ciliata (1.02%) represented a possible limonene-dominant chemotype (71.0%). E. communis (1.91%) contained an exceptionally high proportion of rosefuran oxide (86.2%), whereas E. penduliflora (0.91%) exhibited a pronounced 1,8-cineole chemotype (92.1%). All essential oils showed antimicrobial activity against Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA and MRSA), Escherichia coli, and Candida albicans, with MIC values ranging from 0.4% to 3.2%. Except for E. ciliata against C. albicans, MBC/MIC and MFC/MIC ratios ≤ 4 indicated predominantly bactericidal or fungicidal effects. Molecular docking further identified nine of twenty-eight detected constituents as strong binders to microbial target proteins. These findings expand current knowledge on possible chemotypic diversity within the genus, particularly the discovery of a high-altitude limonene chemotype in E. ciliata and the identification of E. penduliflora as a rich natural source of 1,8-cineole. The convergence of chemical, biological, and in silico evidence supports the ethnomedicinal relevance of Elsholtzia species and highlights their potential as candidates for developing natural antimicrobial agents.

1. Introduction

The genus Elsholtzia Willd. (Lamiaceae) comprises about 40 species worldwide, with 33 species distributed across East and Southeast Asia [1]. These species are aromatic annual or perennial herbs traditionally used as sources of essential oils (EOs), for culinary purposes, and in various forms of folk medicine [2,3]. In Vietnam, our ethnobotanical survey conducted in the northern mountainous region identified four species, E. blanda, E. ciliata, E. communis, and E. penduliflora, among the seven Elsholtzia species reported nationally [4]. Local ethnic communities employ the aerial parts of these plants to prepare decoctions for treating skin rashes, pimples, pruritus, and common colds.

A defining characteristic of Elsholtzia species, and of the Lamiaceae family in general, is their richness in essential oils. These EOs are chemically diverse, typically dominated by monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes. Previous studies have demonstrated a range of biological properties of Elsholtzia volatile oils, including antibacterial, antioxidant, and antiviral activities [2,3]. They have also been applied as natural food preservatives and botanical insecticides [3]. Despite this potential, existing studies in Vietnam have largely focused on EO composition alone, without integrating assessments of biological activity or ethnobotanical context.

Among the four species investigated, E. blanda has been documented in several studies using aerial parts or whole plants collected at elevations above 1000 m [5,6,7]. In our study, flowering tops were sampled at nearly 2000 m in an area where the Hmong people traditionally use this species to treat colds, headaches, sore throat, fever, and diarrhea. E. ciliata is the most extensively studied species; however, previous research in Vietnam has largely involved cultivated lowland populations used as a culinary herb and in traditional medicine (Herba Elsholtziae ciliatae) [8,9,10,11]. E. communis has been documented only once previously in Sapa (Lao Cai) [5]. While the species is cultivated and valued as a citral-rich aromatic herb in China [1], our study focuses on wild-growing populations traditionally used as external remedies and serving as an important nectar source in Ha Giang. E. penduliflora was collected from the wild for research in Sapa in 1995 [5], then in 2007 [12]; however, habitat loss due to urbanization and mass tourism led to the inclusion of this species in the Vietnam Red Book (2007) [13].

Although essential oils of these four species have been studied to some extent, the chemical diversity of Elsholtzia EOs in Vietnam remains insufficiently explored. Furthermore, there has been no comprehensive evaluation combining chemical profiling, biological activity assays, and molecular docking analyses.

This study investigates the EO composition of flowering tops, plant parts traditionally used in local medicinal practices of E. blanda, E. ciliata, E. communis, and E. penduliflora collected from mountainous areas in Lao Cai and Ha Giang provinces. Comparative analysis with existing literature reveals several chemotypes recorded for the first time in Vietnam. The antimicrobial activities of these EOs were evaluated against Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA and MRSA), Escherichia coli, and Candida albicans. Additionally, molecular docking analyses were performed to assess the binding affinities of major EO constituents to selected bacterial targets. The combined biological and in silico evidence strengthens the ethnomedicinal relevance of these Elsholtzia species and highlights their potential as sources of natural antimicrobial agents.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

Fresh aerial flowering portions of four Elsholtzia species (Table 1) were collected in Ha Giang and Lao Cai, Vietnam, in November 2021 and November 2023, respectively. The scientific names of the samples were identified by Dr Hoang Quynh Hoa and M.S. Nghiem Duc Trong from Hanoi University of Pharmacy. All the voucher specimens (Table 1) have been deposited at the Herbarium of Medicinal Plants in Hanoi University of Pharmacy (Herbarium code: HNIP). The fresh materials were shade-dried and stored in a sealed PE bag prior to the EO distillation.

Table 1.

List of Elsholtzia species samples studied and quantity of isolated essential oils.

2.2. Isolation of Essential Oil

The EOs were isolated by hydrodistillation using an apparatus according to the Vietnamese Pharmacopoeia V, without the addition of xylene to the apparatus [11]. The reason is to avoid any influence from the organic solvent when obtaining EO for biological testing. The distillation time was 3 h, and distilled water was used. The EO yield was calculated based on the dry weight of the material (Table 1). Anhydrous sodium sulfate was added to EO to absorb the residual water. After that, the oil was stored in a vial at −5 °C in the dark before the GC-MS analysis and antimicrobial activity testing.

2.3. GC-MS Analysis of Essential Oils

Solutions of EOs were prepared by dissolving 15 µL of EO in n-hexane to a concentration of 1:1000 (v/v). Gas chromatography analysis was performed using GC Intuvo 9000 equipped with an MSD 5977B mass spectrometer detector (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), utilizing a non-polar DB-5MS fused silica capillary column (30 m × 250 µm × 0.25 µm). The oven temperature was programmed to 50 °C and maintained for 3 min; then, the temperature increased to 280 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min. The inlet temperature was set at 250 °C, and the split ratio was 300:1. Helium, with a flow rate of 1 mL/min, was used as the carrier gas. The transfer line temperature was set at 250 °C. Electron ionization (EI) energy was 70 eV with a scan range from 35 to 450 amu.

The retention indices (RI) of the components were determined using n-alkanes (C8-C20) analyzed under the same conditions. The volatile components were identified by comparing their mass spectra and RI values to those of reference compounds and the NIST 2014 mass spectral library, the NIST Chemistry WebBook, and the Adams book [14].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The distances between groups of the abovementioned Elsholtzia spp. EO compositions were measured using multivariate analysis by including hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) and principal components analysis (PCA) of identified components in the Elsholtzia EOs studied. The statistical analyses were performed with R-Studio tools.

2.5. Antimicrobial Assay

Four standardized ATCC strains from library stock cultures were Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25932 (MSSA), ATCC 33591 (MRSA) (Gram-positive), Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 (Gram-negative), and Candida albicans ATCC 10231 (yeast). Minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of EOs were measured by microdilution on a 96-well plate (SPL) in cation-adjusted Muller-Hinton broth (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for bacteria and Sabouraud dextrose broth (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) for yeast, following Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute recommendations [15,16].

The EOs were emulsified in a solution of 4% Tween 80 in water; subsequently, a two-fold dilution series was prepared, ranging from 3.2% to 0.025% (v/v), with the dilutions made in broth. The growth control corresponded to the bacteria without EO, and the sterile control corresponded to the appropriate medium without bacteria. The reference standard is moxifloxacin (Sigma-Aldrich) for bacteria and itraconazole (Sigma-Aldrich) for yeast.

The inoculum is prepared by diluting a broth culture to ensure that it contains approximately 1.5 × 106 CFU/mL for bacteria and 1.5 × 104 CFU/mL for yeast. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) was recorded by turbidity of inoculum suspensions and defined as the lowest concentration at which no microbial growth is observed. Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) and Minimum Fungicidal Concentration (MFC) were evaluated on the basis of MIC plates. All wells with concentrations greater than or equal to MIC were inoculated onto the corresponding agar plate. The number of microorganisms was compared with the initial inoculum. MBC was defined as the concentration that could kill more than 99.9% of the prepared inoculum. MIC and MBC, or MFC, were evaluated through at least three independent experiments. The ratios MBC/MIC or MFC/MIC were used as a method to evaluate bactericidal or fungicidal activities.

2.6. Molecular Docking

Molecular docking was performed to simulate the interaction between the main components in four Elsholtzia EOs and some relevant targets of microorganisms. The four proteins for molecular docking were selected based on their critical and distinct roles in microbial pathogenesis and resistance mechanisms, corresponding directly to the clinical strains tested. For Gram-positive bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus), two Penicillin-Binding Proteins were chosen: PBP1 (PDB ID: 7O49), an essential enzyme for peptidoglycan synthesis and cell survival, and PBP2a (PDB ID: 3ZFZ), the key Methicillin resistance determinant in MRSA. Targeting PBP2a directly assesses the compounds’ ability to inhibit this core resistance mechanism. For the Gram-negative bacterium (Escherichia coli), the Ribosome 30S subunit (PDB ID: 4V4A) was selected to evaluate the disruption of protein synthesis, a non-cell wall-related mechanism. Finally, to model the antifungal activity against Candida albicans, the CYP51 (Lanosterol 14-alpha-demethylase) enzyme (PDB ID: 5FSA) was chosen, as it is critical for ergosterol biosynthesis and membrane integrity in fungi. This targeted approach provides a mechanistic basis for interpreting the observed broad-spectrum activities.

All protein constructs used in this study were downloaded from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (https://www.rcsb.org/) and were of high quality and suitable for simulation. These proteins were then prepared in AutoDock Tools 1.5.6 following standard procedures, including removal of non-essential components, addition of hydrogens and Kollman charges, and identification of the active site for docking. The structures of the investigated compounds were obtained from the PubChem Database and prepared in Autodock Tools prior to docking. Molecular docking was performed using AutoDock Vina with the following parameters: (1) Box size: 18 Å × 18 Å × 18 Å, (2) Spacing: 1000, (3) Exhaustiveness: 24, (4) Num-modes: 20 [17]. Docking simulation was conducted to evaluate interaction between the main component of the four Elsholtzia EOs and selected biological targets from S. aureus (MSSA and MRSA), E. coli, and C. albicans. The ligand-protein interaction was visualized using BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Results of Hydrodistillation and GC-MS

The essential oil content of the four Elsholtzia species obtained by hydrodistillation ranged from 0.91 to 1.90%. Among them, E. communis exhibited the highest yield (1.90%), followed by E. blanda (1.17%), E. ciliata (1.02%), and E. penduliflora (0.91%) (Table 1). Compared with previously reported essential oil yields from aerial parts of the same species in Vietnam, the oil content obtained from flowering tops in our study was higher [7,10]. The total ion chromatograms of four EOs are shown in Figure S1. A total of 28 components were identified in the EOs of four Elsholtzia species by GC-MS, accounting for 99.3–99.9% of the total oils (Table 2).

Table 2.

Chemical composition of essential oil from the aerial parts of Elsholtzia species.

3.2. Essential Oil Composition and Possible Chemotypic Variation of Elsholtzia blanda

Elsholtzia blanda essential oil (EO) from Bat Xat was dominated by oxygenated monoterpenes (68.0%), accompanied by a high proportion of monoterpene hydrocarbons (29.7%). The oil exhibited a complex chemical profile comprising twenty constituents, each ranging from 0.3% to 29.0%. The major components were 1,8-cineole (29.0%), camphor (17.0%), camphene (12.2%), linalool (11.8%), and linalool isobutanoate (7.8%), the latter of which has not been previously reported in any other Elsholtzia species.

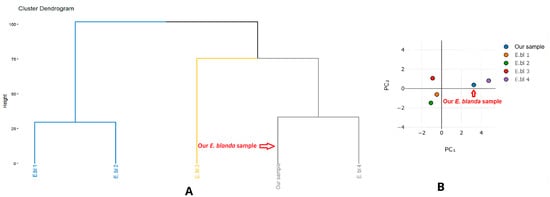

Multivariate statistical analysis, including hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) and principal component analysis (PCA), included the main essential oil components of samples with concentrations ≥3%. E. blanda was conducted on five EO samples, consisting of our sample (E.bl) and four others in a previous study, collected from mountainous regions of Vietnam (E.bl 1–E.bl 4) [5,6,7].

Figure 1 presents the cluster dendrogram, which groups the five samples into three distinct possible chemotypes:

Figure 1.

Cluster analysis (A) and principal component analysis (B) based on the chemical composition of Elsholtzia blanda essential oils.

Cluster 1: Linalool-rich chemotype (E.bl 1, E.bl 2). These two samples share exceptionally high linalool contents (56.8% and 75.2%), closely resembling the chemical composition previously reported for E. blanda from India [18].

Cluster 2: 1,8-cineole–dominant chemotype (E.bl 3). Represented by a single sample, this group is characterized by an exceptionally high level of 1,8-cineole (62.0%). No comparable chemotype has been documented in studies from other countries (India, Thailand) [18,19,20].

Cluster 3: Camphene–camphor chemotype (E.bl 4 and our sample). These samples are defined by high proportions of camphene (22.6% and 12.2%) and camphor (25.1% and 17.0%). However, in our sample, these two markers are not the most abundant components; instead, the oil contains elevated 1,8-cineole (29.0%), similar to Cluster 2, and linalool (11.8%), as observed in Cluster 1. Moreover, our sample uniquely includes linalool isobutanoate (7.8%), which is absent from the other samples. Overall, our E. blanda sample may embody a unique possible chemotype with a heterogeneous chemical profile, potentially signifying a transitional form or hybridisation among the previously identified chemotypes. The high-altitude ecological conditions of Bat Xat (>2000 m) may significantly influence this unique chemical profile.

3.3. Essential Oil Composition and Possible Chemotypic Variation of Elsholtzia ciliata

Elsholtzia ciliata is widely used as a culinary herb and traditional medicine in Vietnam. The plant grows naturally or is cultivated in diverse ecological regions across the country. In this study, we analyzed the EO composition of E. ciliata collected from wild-growing plants in the Bat Xat district, Lao Cai province, and found a remarkable difference compared to previous reports from Vietnam and other countries. Specifically, the Bat Xat sample was dominated by limonene (71.0%), followed by Carvone (15.5%) and 1,8-cineole (9.7%), representing a possible unique chemotype not previously observed in E. ciliata. In contrast, samples collected from other regions of Vietnam such as the mountainous area (Lao Cai), the midland region (Phu Tho), the delta region (Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City) exhibited relatively consistent chemical profiles, characterized by high contents of β-ocimene (13.3–21.5%), (α + β)-citral (31.3–40.2%), 1-octen-3-ol (4.2–7.1%), β-caryophyllene (6.1–9.2%), and (E/Z)-β-farnesene (8.3–22.7%) [8,9,10]. Meanwhile, E. ciliata samples from Lithuania and Russia displayed a distinct ketone-rich chemotype, dominated by elsholtzia ketone (5.7–25.0%) and dehydroelsholtzia ketone (70.1–75.3%) [21,22] (Table S2).

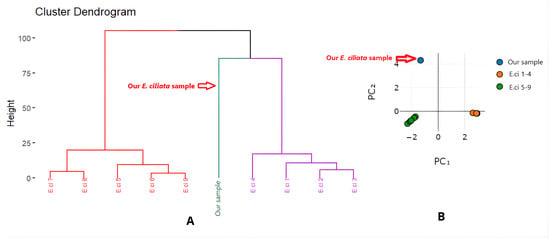

Multivariate analysis, encompassing Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA), on ten samples of Elsholtzia ciliata EO (Table S2) achieved the results shown in Figure 2. The samples were grouped into three possible chemotypic clusters: Group 1 consisted of Russian samples (E.ci 5–9) characterized by high contents of elsholtzia ketone and dehydroelsholtzia ketone. Group 2 included cultivated Vietnamese samples (E.ci 1–4), which exhibited high levels of citral and β-ocimene. The Bat Xat sample, due to its unprecedented dominance by limonene, was separated into a distinct Group 3. These HCA and PCA results are aligned with the study on E. ciliata essential oils in Korea, which reported three chemotypes—citral, limonene, and acylfuran [23].

Figure 2.

Cluster analysis (A) and principal component analysis (B) based on the chemical composition of E. ciliata essential oils.

This is the first report of a possible limonene chemotype from wild E. ciliata growing in the northern mountainous region of Vietnam. This finding enriches the chemotypic diversity profile of E. ciliata and opens new avenues for further functional and biological investigations. This discovery adds to the phytochemical diversity map of E. ciliata and paves the way for more functional and biological studies.

3.4. Essential Oil Composition and Possible Chemotypic Variation of Elsholtzia communis

The EO of Elsholtzia communis was dominated by monoterpenes featuring an acyl furan ring. Four of the five major components—rosefuran oxide (86.2%), elsholtzia ketone (5.3%), dehydroelsholtzia ketone (2.0%), and rosefuran (1.8%)—shared this acylfuran backbone, collectively accounting for over 90% of the oil’s composition. The fifth component, β-caryophyllene (5.6%), is a common sesquiterpene hydrocarbon widely found in plant EOs.

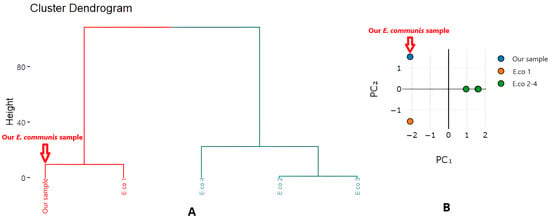

These acylfuran compounds were exclusively identified in E. communis among the four Elsholtzia species examined, suggesting a distinct chemical profile. Notably, the absence of typical monoterpenes such as limonene, β-ocimene, and 1,8-cineole, which are present in E. ciliata, E. blanda, and E. penduliflora, underscores the unique chemical profile of E. communis. Our Bat Xat sample closely resembled sample E.co 1 from a Vietnamese study [5], where elsholtzia ketone was the dominant component (82.30%). In contrast, E. communis samples E.co 2–4 collected from Thailand [24,25] and India [26] exhibited a different chemotype, with citral (β-citral and α-citral) as the predominant constituent (54.0–81.0%) (Table S3).

Cluster analysis and principal component analysis (PCA) based on chemical composition supported the classification into distinct groups. Vietnamese samples clustered together, characterized by a high acylfuran content, while the Thai and Indian samples formed a separate cluster dominated by citral (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Cluster analysis (A) and principal component analysis (B) based on the chemical composition of E. communis essential oils.

According to biosynthetic pathway studies in Elsholtzia species, there is a proposed transformation route from citral → rosefuran → elsholtzia ketone (Figure S2) [27], which may explain the observed compositional diversity in E. communis EOs and the coexistence of these three major compound groups.

3.5. Essential Oil Composition and Possible Chemotypic Variation of Elsholtzia penduliflora

The EO of Elsholtzia penduliflora was extremely simple (4 compoments) and concentrated, with 1,8-cineole making up 92.1% of the oil. In addition to 1,8-cineole, three minor components were found: m-cymene (4.5%), β-pinene (2.0%), and α-pinene (0.7%).

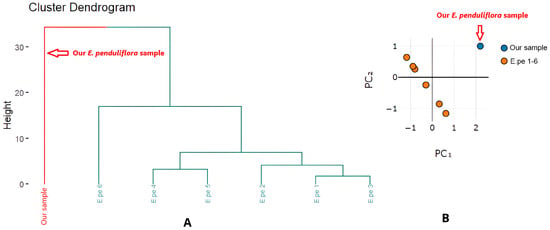

A comparison of the EO composition of E. penduliflora from our study with reports from Vietnam [6,12] and China [28] is presented in Table S4 and Figure 4. Across all studies, 1,8-cineole is the principal compound ranging from 60% to 92%.

Figure 4.

Cluster analysis (A) and principal component analysis (B) based on chemical composition of E. penduliflora essential oils.

Cluster dendrogram (Figure 4A) and PCA result (Figure 4B) highlight the distinction between our sample and previously reported samples, primarily driven by variation in 1,8-cineole content. Notably, with flowering tops as the plant material, our EO yield (0.91%) was markedly higher than that reported for whole aerial parts (0.28–0.45%) [6].

These findings indicate that naturally growing E. penduliflora from Bat Xat represents a potent natural source of 1,8-cineole. This region may serve as an alternative collection site to Sa Pa, where rapid urbanization and mass tourism have reduced natural populations and contributed to the species being listed for conservation in Vietnam [13].

3.6. Antimicrobial Effects of Essential Oils from Elsholtzia Species

Table 3 shows the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal or fungicidal concentration values (MBC or MFC) for EOs from four Elsholtzia species against various microorganisms: Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923—MSSA, ATCC 33591—MRSA), Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922), and Candida albicans (ATCC 10231). These results are expressed as percentages (v/v).

Table 3.

Antibacterial and antifungal effects of Elsholtzia species (%, v/v).

The data suggest varying degrees of antibacterial and antifungal activity among the Elsholtzia species tested. The MIC and MFC values ranged from 0.4% to 3.2%. The MBC/MIC and MFC/MIC ratios do not exceed 4, indicating that the EOs from these species exhibited bactericidal and fungicidal activity against all four strains of microorganism, except for E. ciliata EO on C. albicans.

The antifungal efficacy of the four EOs against C. albicans was superior to their antibacterial efficacy, with E. blanda and E. ciliata exhibiting an MIC of 0.4% each, while E. communis and E. penduliflora had an MIC of 0.8%. EOs of E. blanda, E. communis and E. penduliflora showed fungicidal effects, with the ratio of MFC/MIC not surpassing 4, while E. ciliata did not show a fungicidal effect.

Between the two strains of Staphylococcus aureus, the effects of EOs on MSSA were generally better than on MRSA, except for the EO of E. penduliflora, which showed better effects on MRSA than on MSSA. All four EOs showed antibacterial effects on MSSA, with the MIC values of the EOs of the three species, E. blanda, E. communis, and E. penduliflora, all being 0.8%, slightly lower than that of the EO of E. ciliata (1.6%). The antibacterial effect of EOs on E. penduliflora EO exhibited the strongest antibacterial activity against MRSA (MIC = 0.4%), followed by E. communis EO (0.8%), E. blanda EO (1.6%), and E. ciliata EO (3.2%).

The effects of the three EOs on the Gram-negative bacteria E. coli were not really impressive when compared with their effects on S. aureus and C. albicans. E. communis EO showed the strongest antibacterial effect (MIC = 0.8%). E. blanda and E. penduliflora EOs showed similar effects (MIC values were both 1.56%); E. ciliata EO had the weakest effect (MIC = 3.13%).

3.7. Docking Study of Volatile Components in Four Elsholtzia EOs

Twenty-eight constituents were found in the EOs of four Elsholtzia species. The study aimed to investigate the interactions of these compounds with the pertinent microtubule targets. Molecular docking research was conducted for each bacterial and yeast strain, targeting antimicrobial properties. The docking scores of all identified components to the microorganism targets are shown in Table 4. In addition, several compounds with good docking scores for each target were selected to provide docking poses (3D) and interactions (2D) with the active sites of the corresponding enzymes; the data are shown in Figures S3–S6.

Table 4.

Docking score of volatile components of four Elsholtzia EOs to the relevant targets of the microtube.

3.8. Docking Scores of Identified Components

All the main components in four EOs exhibited good docking scores to the PBP1 of MSSA (−6.5 to −9.5 kcal/mol). The EOs of E. blanda, E. communis, and E. penduliflora exhibited stronger anti-MSSA activity than E. ciliata, mainly due to their high contents of 1,8-cineole, camphor, linalool, camphene, linalool isobutanoate, and rosefuran oxide, which showed better docking scores than limonene (the major component of E. ciliata).

The EO components of Elsholtzia species showed quite good docking scores on PBP2a of MRSA (−5.8 to −8.8 kcal/mol), which is slightly weaker than the docking score on PBP1 of MSSA. E. penduliflora (rich in 1,8-cineole) showed the strongest activity against MRSA, followed by E. communis (high in rosefuran oxide) and E. blanda (containing camphor and linalool isobutanoate). E. ciliata had the weakest anti-MRSA effect, consistent with the moderate docking score of limonene against PBP2a (−6.7 kcal/mol).

The docking score of all EO components to the target of the ribosome 30S of E. coli was moderate, ranging from −5.3 to −9.1 kcal/mol. Among four EOs, the E. communis EO showed the strongest activity against E. coli (MIC = 0.8%), with its main components rosefuran oxide (86.23%) and β-caryophyllene (4.59%) able to contribute to its antimicrobial activity against E. coli, with docking scores of −7.9 and −8.9 kcal/mol, respectively.

All identified components showed good to excellent docking scores toward the CYP51 enzyme of C. albicans, ranging from −7.1 to −11.7 kcal/mol. The docking score of some main components (β-caryophyllene, linalool isobutanoate, elsholtzia ketone, dehydroelsholtzia ketone, carvone, limonene, 1,8-cineol) partly explained the good antifungal activity of four Elsholtzia EOs.

3.9. Interaction of Selected Components with the Active Site of the Enzyme

The active site of S. aureus PBP-1 contains conserved motifs (SxxK, SxN, KTGT), where Ser314 acts as the nucleophile and Lys317 as the catalytic base, forming a positively charged cleft stabilized by Trp351 and Tyr566 [28]. Docking results showed that several compounds (e.g., α-pinene, limonene, camphor, dehydroelsholtzia ketone, linalool isobutanoate) interact with Trp351 and Tyr566 similarly to β-lactam antibiotics, suggesting potential inhibitory activity. Moreover, rosefuran oxide, dehydroelsholtzia ketone, and linalool isobutanoate uniquely interact with Asn370, potentially enhancing the docking score (Figure S3).

In PBP2a, the active site involves Ser403 and a conserved oxyanion hole (Ser403, Thr600), which is critical for catalytic stability and resistance. Key residues (Tyr446, Thr600) [29,30] interact strongly with elsholtzia ketone, dehydroelsholtzia ketone, D-carvone, and linalool isobutanoate, whereas m-cymene, 1,8-cineole, camphor, and rosefuran oxide mainly engage Tyr446 (Figure S4).

For the E. coli 30S ribosomal subunit, while reference antibiotics (streptomycin, gentamicin, amikacin) interacted broadly with the decoding center nucleotides (A1492, A1493, G530), natural compounds showed limited interactions: 1,8-cineole, camphor, and rosefuran oxide only bound to A1408 [31] without engaging the core decoding nucleotides (Figure S5). This partially elucidates that the impact of EOs on E. coli was generally less pronounced than on S. aureus and C. albicans, with the exception of the E. communis sample, where rosefuran oxide constituted 86.2%. Furthermore, 1,8-cineole and camphor, which interact with A1408, contributed to the anti-E. coli efficacy of E. blanda (1,8-cineole: 29.0%, camphor: 17.0%) while the anti-E. coli activity of E. pendulifora was predominantly attributed to 1,8-cineol (92.1%).

The active site of CYP51 in Candida albicans is maintained by key residues such as Tyr-118, Tyr-132, and Lys-143 [32], which form hydrogen bonds with the heme (HEM580) to stabilize its position and facilitate substrate binding. Cys-470 serves as the proximal axial ligand to the heme iron, essential for catalytic redox reactions, while His-310 and Thr-311 on helix I assist in proton transfer during sterol 14α-demethylation. Compounds including rosefuran oxide, linalool isobutanoate, β-caryophyllene, and the antifungal drugs fluconazole, itraconazole, and voriconazole show similar interaction patterns with CYP51. Specifically, fluconazole, voriconazole, rosefuran oxide, linalool isobutanoate, and β-caryophyllene interact with Tyr-118, whereas itraconazole does not. Conversely, itraconazole, rosefuran oxide, dehydroelsholtzia ketone, linalool isobutanoate, and β-caryophyllene interact uniquely with Tyr-132, indicating distinct binding modes compared to fluconazole and voriconazole (Figure S6).

4. Conclusions

The essential oils of four high altitude Elsholtzia species exhibited clear chemotypic differentiation, spanning limonene, 1,8-cineole, and rosefuran oxid dominant profiles. All oils showed measurable antimicrobial effects, supported in part by molecular docking, which identified several constituents with strong predicted interactions with microbial targets. These results enhance current knowledge of chemical diversity within the genus and confirm the relevance of Elsholtzia species as valuable aromatic resources with potential applications in natural antimicrobial product development. Further work on ecological drivers of possible chemotype formation and targeted bioactivity evaluations will support their broader utilization in crop and plant derived industries.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/crops6010002/s1, Table S1. The main components of Elsholtzia blanda essential oil of our research and other studies in Vietnam and worldwide. Table S2. The main components of Elsholtzia ciliata essential oil of our research and other studies in Vietnam and around the world. Table S3. The main components of Elsholtzia communis essential oil in our research and other studies in Vietnam and around the world. Table S4. The main components of Elsholtzia penduliflora essential oil of our research and other studies in Vietnam and around the world. Figure S1. GC-MS total ion chromatograms of four Elsholtzia species essential oils studied. Figure S2. Speculation on biosynthesis pathways of Elsholtzia essential oil. Figure S3. Docking pose (3D) and interaction (2D) between some selected composition and active site of enzyme PBP1 of MSSA. Figure S4. Docking pose (3D) and interaction (2D) between some selected composition and active site of enzyme PBP2a of MRSA. Figure S5. Docking pose (3D) and interaction (2D) between some selected composition and active site of enzyme 30S of E. coli. Figure S6. Docking pose (3D) and interaction (2D) between some selected composition and active site of enzyme CYP51 of C. albicans.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.Q.C., N.T.T., D.T.B.D., A.R. and D.Q.; methodology, N.T.T., D.T.M.D., N.K.T., O.K. and A.R.; software, N.T.T., D.T.B.D., D.T.M.D.; validation, D.H.Q., A.R. and D.Q.; formal analysis, N.Q.C., N.T.T., D.T.B.D. and D.Q.; investigation, N.Q.C., N.T.T., H.Q.H., D.Q.; resources, D.Q.; data curation, N.T.T., D.T.M.D. and D.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, N.Q.C., N.T.T., D.T.B.D., D.T.M.D., N.K.T.; writing—review and editing, H.D., A.R. and D.Q.; visualization, N.T.T., D.T.B.D., D.T.M.D., D.H.Q. and D.Q.; supervision, H.D., A.R. and D.Q.; project administration, N.Q.C., D.H.Q. and D.Q.; funding acquisition, N.Q.C. and D.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Fondation Pierre Fabre, within the framework of the Mekong Pharma Network, collaborative research project (ELSHOLTZIA).

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the results of this study can be obtained from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Römer; Usteri. Elsholtzia Willd. Plants of the World Online. First Published in Bot. Mag. (Römer & Usteri) 4(11): 3(1790). Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:20816-1/images (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Chen, S.; Chen, J.; Xu, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, J. Elsholtzia: A Genus with Antibacterial, Antiviral, and Anti-Inflammatory Advantages. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 297, 115549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dram, D.; Guo, J.-Z.; Wei, R.-R.; Ma, Q.-G. A Review of Traditional Use, Constituent Analysis, Bioactivity, and Application of Volatile Oils from Elsholtzia. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2025, 28, 737–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuong, V.X. Flora of Vietnam, Lamiaceae Lindl. (Labiatae Juss.); Science & Technics Publishing House: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2000; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Lesueur, D.; Bighelli, A.; Tam, N.T.; Than, N.V.; Dung, P.T.K.; Casanova, J. Combined Analysis by GC (RI), GC/MS and 13C NMR Spectroscopy of Elsholtzia blanda, E. penduliflora and E. winitiana Essential Oils. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2007, 2, 1934578X0700200814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dung, N.X.; Huy, D.Q.; Van Khiěn, P.; Mõi, L.D.; Cu, L.D.; Nam, V.V.; Van Hac, L.; Khôi, T.T.; Leclercq, P.A. Contribution of HRC to the Study on the Chemistry of Natural Plants, Chemotaxonomy, and Biodiversity Conservation. J. High Resolut. Chromatogr. 1995, 18, 603–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.N.; Hoang, T.B. The Antimicrobial Activity and Chemical Composition of Elsholtzia blanda (Benth.) Benth. Essential Oils in Lam Dong Province, Viet Nam. CTUJS 2022, 14, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.B.; Beaufay, C.; Nghiem, D.T.; Mingeot-Leclercq, M.-P.; Quetin-Leclercq, J. In Vitro Anti-Leishmanial Activity of Essential Oils Extracted from Vietnamese Plants. Molecules 2017, 22, 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duy, N.D.; Thuy, N.T.K.; Trang, M.T.N.; Bay, N.K.; Van, Q.T.T.; Thuy, Q.C.; Thao, B.T.P. Chemical composition of the essential oils of Elsholtzia ciliata (Thunb.) Hyl. grown in Phu Tho province. J. Sci. Technol. 2022, 27, 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- Luu Tang Phuc, K.; Nguyen, H.T.; Cao, V.L.; Nguyen, N.T.P.; Nguyen, H.V.; Truong, V.; Phan, T.B.; Phuong Dung, T.T.; Xuan Tong, N. Chemical Composition of Elsholtzia ciliata (Thunb.) Hyland Essential Oil in Vietnam with Multiple Biological Utilities: A Survey on Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, Anticancer Activities. AJB 2023, 45, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vietnam Pharmacopoeia Committee. Vietnam Pharmacopoeia; Medical Publishing House: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2017; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Dung, P.T.K. Study on Some Elsholtzia Species Growing in Sapa, Lao Cai. Ph.D. Thesis, Hanoi University of Pharmacy, Hanoi, Vietnam, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology. Vietnam Red Data Book, Part II: Plants; Science and Technology Publishing House: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2007; pp. 242–243. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R.P. Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry; Allured Publishing Corp.: Carol Stream, IL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- CLSI M100; Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2020.

- CLSI M27-A2; Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts, 2nd ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2017.

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the Speed and Accuracy of Docking with a New Scoring Function, Efficient Optimization, and Multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotoky, R.; Saikia, S.P.; Chaliha, B.; Nath, S.C. Chemical Compositions of the Essential Oils of Inflorescence and Vegetative Aerial Parts of Elsholtzia blanda (Benth.) Benth. (Lamiales: Lamiaceae) from Meghalaya, North-East India. Braz. J. Biol. Sci. 2017, 4, e252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, P.N.; Satyal, P.; Setzer, W.N.; Awale, S.; Watanabe, S.; Maneenet, J.; Satyal, R.; Acharya, A.; Phuyal, M.; Gyawali, R. Chemical-Enantiomeric Characterization and In-Vitro Biological Evaluation of the Essential Oils from Elsholtzia strobilifera (Benth.) Benth. and E. blanda (Benth.) Benth. from Nepal. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2023, 18, 1934578X231189325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bestmann, H.J.; Rauscher, J.; Vostrowsky, O.; Pant, A.K.; Dev, V.; Parihar, R.; Mathela, C.S. Constituents of the Essential Oil of Elsholtzia blanda Benth (Labiatae). J. Essent. Oil Res. 1992, 4, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korolyuk, E.; König, W.; Tkachev, A. Composition of Essential Oils of Elsholtzia ciliata Thunb. Hyl. from the Novosibirsk Region, Russia. Khim. Rastit. 2002, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Martišienė, I.; Zigmantaitė, V.; Pudžiuvelytė, L.; Bernatonienė, J.; Jurevičius, J. Elsholtzia ciliata Essential Oil Exhibits a Smooth Muscle Relaxant Effect. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.S. Chemotaxonomy Based on Essential Oil Composition and Characteristics of Native Elsholtzia ciliata (Thunb.) Hylander. Ph.D. Thesis, Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, X.; Tang, R.; Zhang, A.; Du, Z.; Yang, L.; Xu, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Yang, R.; Chen, W.; Pu, C. Mining, Expression, and Phylogenetic Analysis of Volatile Terpenoid Biosynthesis-Related Genes in Different Tissues of Ten Elsholtzia Species Based on Transcriptomic Analysis. Phytochemistry 2022, 203, 113419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanaseelungkoon, N.; Julsrigival, J.; Phannachet, K.; Chansakaow, S. Chemical Compositions and Biological Activities of Essential Oils Obtained from Some Apiaceous and Lamiaceous Plants Collected in Thailand. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2018, 11, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phetsang, S.; Panyakaew, J.; Wangkarn, S.; Chandet, N.; Inta, A.; Kittiwachana, S.; Pyne, S.G.; Mungkornasawakul, P. Chemical Diversity and Anti-Acne Inducing Bacterial Potentials of Essential Oils from Selected Elsholtzia Species. Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, 33, 553–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, S.; Tamuli, K.J.; Saikia, S.; Narzary, B.; Gogoi, B.; Bordoloi, M.; Neipihoi; Dutta, D.; Sahoo, R.K.; Das, A.; et al. Essential Oil from the Leaves of Elsholtzia communis (Collett & Hemsl.) Diels from North East India: Studies on Chemical Profiling, Antimicrobial, Cytotoxic and ACE Inhibitory Activities. Flavour Fragr. J. 2021, 36, 626–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Zhang, G.; Yang, S. Essential Oils of Elsholtzia penduliflora. Zhongguo Yaoxue Zazhi 1990, 25, 79–80. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, Y.; Wong, M.T.Y.; Essex, J.W. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Antibiotic Ceftaroline at the Allosteric Site of Penicillin-Binding Protein 2a (PBP2a). Isr. J. Chem. 2020, 60, 754–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambade, S.S.; Gupta, V.K.; Bhole, R.P.; Khedekar, P.B.; Chikhale, R.V. A Review on Five and Six-Membered Heterocyclic Compounds Targeting the Penicillin-Binding Protein 2 (PBP2A) of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA). Molecules 2023, 28, 7008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanbonmatsu, K. Energy Landscape of the Ribosomal Decoding Center. Biochimie 2006, 88, 1053–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hargrove, T.Y.; Friggeri, L.; Wawrzak, Z.; Qi, A.; Hoekstra, W.J.; Schotzinger, R.J.; York, J.D.; Guengerich, F.P.; Lepesheva, G.I. Structural Analyses of Candida Albicans Sterol 14α-Demethylase Complexed with Azole Drugs Address the Molecular Basis of Azole-Mediated Inhibition of Fungal Sterol Biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 6728–6743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.