Abstract

The cultivation of blueberry (Vaccinium spp.) has undergone an unprecedented global expansion, driven by its nutraceutical value and the diversification of production zones across the Americas, Europe, and Asia. Its consolidation as a strategic crop has prompted intensive scientific activity aimed at optimizing every stage of management from propagation and physiology to harvest, postharvest, and environmental sustainability. However, the available evidence remains fragmented, limiting the integration of results and the formulation of knowledge-based, comparative production strategies. The objective of this systematic review was to synthesize scientific and technological advances related to the integrated management of blueberry cultivation, incorporating physiological, agronomic, technological, and environmental dimensions. The PRISMA 2020 methodology (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) was applied to ensure transparency and reproducibility in the search, selection, and analysis of scientific literature indexed in the Scopus database. After screening, 367 articles met the inclusion criteria and were analyzed comparatively and thematically. The results reveal significant progress in propagation using hydrogel and micropropagation techniques, efficient fertigation practices, and the integration of climate control operations within greenhouses, leading to improved yield and fruit quality. Likewise, non-thermal technologies, edible coatings, and harvest automation enhance postharvest quality and reduce losses. In terms of sustainability, the incorporation of water reuse and waste biorefinery has emerged as key strategies to reduce the environmental footprint and promote circular systems. Among the main limitations are the lack of methodological standardization, the scarce economic evaluation of innovations, and the weak linkage between experimental and commercial scales. It is concluded that integrating physiology, technology, and sustainability within a unified management framework is essential to consolidate a resilient, low-carbon, and technologically advanced fruit-growing system.

1. Introduction

The cultivation of blueberries (Vaccinium spp.) has become one of the most rapidly expanding fruit crops worldwide in recent decades, driven by both its high economic value and its nutritional and functional importance [1]. Increasing international market demand has encouraged varietal diversification and the adoption of new cultivation technologies in nontraditional regions, ranging from temperate to subtropical climates [2]. This process has transformed global fruit growing, stimulating knowledge generation on physiology, agronomic management, technological innovation, and environmental sustainability. Currently, countries such as the United States, Peru, Chile, Spain, and China lead global production, while new regions in Latin America and Eastern Europe are emerging with competitive potential [3].

The integrated management of blueberries encompasses all stages of the production system from plant propagation and crop establishment to harvest, postharvest, and industrial processing. Recent scientific literature reports significant advances in in vitro and cutting propagation [4], nutritional control and fertigation management [5], phenological regulation through physiological compounds [6], the use of protected structures [7], integrated pest management, and harvest mechanization [8,9]. Likewise, postharvest stages have benefited from emerging technologies such as high hydrostatic pressure, pulsed light, thermosonication, and edible coatings, all aimed at extending shelf life and preserving the fruit’s bioactive compounds [10]. This holistic approach has enabled an understanding of blueberry as a complex biological system in which technological innovation and sustainability must operate synergistically.

Systematic reviews have become essential tools for integrating the broad and fragmented scientific evidence available on blueberry management. Unlike narrative reviews, this methodological approach allows for the identification of patterns, knowledge gaps, and emerging trends based on rigorous search, selection, and analytical criteria [11,12]. Its application in the agricultural field is particularly relevant, as it connects dispersed experimental results with real innovation needs in production systems, thus facilitating technology transfer to growers, nurseries, and agro-industries. Within this context, systematic review provides a solid scientific foundation to guide policy design, research programs, and investment decisions in sustainable and technology-driven agriculture [13].

The objective of this systematic review was to analyze the main scientific and technological approaches associated with the integrated management of blueberry cultivation, covering physiological, agronomic, technological, and environmental dimensions. To achieve this goal, the following research questions (RQ) were formulated:

RQ1. What are the most efficient and sustainable plant propagation and establishment techniques that ensure uniformity, vigor, and adaptability under different agroclimatic conditions?

RQ2. How do nutrition, fertigation, and eco-physiological regulation strategies influence productivity, fruit quality, and the efficient use of water and energy resources?

RQ3. What role do controlled-environment production technologies play in optimizing microclimate and mitigating abiotic stress?

RQ4. In what ways do sustainability and circular economy strategies (water reuse, renewable energy, life cycle assessment LCA, and biorefinery) contribute to reducing environmental impact and strengthening production system resilience?

RQ5. Which innovations in mechanization, harvesting, and postharvest handling ensure the preservation of bioactive compounds, food safety, and competitiveness of blueberries in demanding global markets?

To address these questions, the PRISMA 2020 methodology (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) was applied to ensure transparency and reproducibility throughout the search, selection, coding, and analysis processes. The review was based on documents indexed in the Scopus database, excluding grey literature and prioritizing experimental studies and specialized reviews. This integrative approach made it possible to connect the most relevant scientific evidence around technological innovation, environmental sustainability, and blueberry physiology, providing a comprehensive understanding of the current state and future challenges of this crop.

2. Global Context of Blueberry (Vaccinium spp.) Production Systems

Global blueberry production relies on a limited number of species and interspecific hybrid groups within the genus Vaccinium, whose chilling requirements and stress tolerance largely determine their geographic distribution and production systems. Northern highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum) is the dominant species in temperate regions, particularly in North America and Europe, where winter chilling requirements range from 800 to 1200 h, supporting stable production of cultivars such as ‘Duke’, ‘Bluecrop’, ‘Liberty’, ‘Aurora’, and ‘Legacy’. Rabbiteye blueberry (Vaccinium ashei), characterized by intermediate chilling requirements (500–600 h) and greater tolerance to adverse conditions, is widely used in warmer environments, including the southeastern United States and parts of South America. Southern highbush blueberries, derived from interspecific breeding programs, exhibit lower chilling requirements and higher heat tolerance, enabling commercial production in subtropical and Mediterranean regions with cultivars such as ‘Ventura’, ‘Star’, ‘Alixblue’, and ‘Gupton’. In contrast, lowbush blueberry species (Vaccinium angustifolium and Vaccinium myrtilloides) are mainly associated with cold climates and processing-oriented systems. These genetic groups underpin regional differences in production strategies, technology adoption, and research priorities across the global blueberry industry.

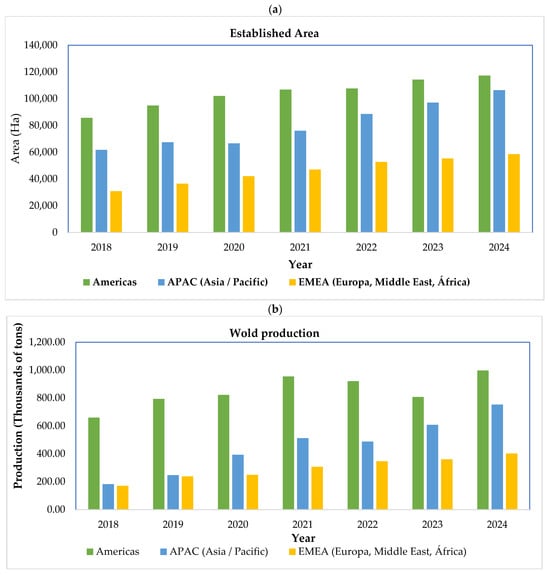

In line with the expansion of these genetic groups, the global area dedicated to blueberry cultivation has increased markedly over recent years (Figure 1a). By 2024, worldwide blueberry area reached approximately 282,192 hectares, with the Americas accounting for the largest share of established plantations. Between 2018 and 2024, global cultivated areas increased by 58.4%, reflecting sustained investment and market-driven expansion. The most pronounced growth occurred in the Asia–Pacific (APAC) region, which added nearly 44,687 hectares during this period, driven largely by the rapid adoption of southern highbush cultivars, intensive production systems, and protected cultivation technologies. Although area expansion continued across all regions, the annual rate of new plantation establishment slowed slightly between 2022 and 2024 in both the Americas and EMEA, suggesting a gradual transition from extensive expansion toward consolidation, intensification, and productivity-oriented strategies in more mature production systems.

Figure 1.

(a) Global area under cultivation and (b) total blueberry production.

The expansion in cultivated area has been accompanied by a substantial increase in global blueberry production, which grew by approximately 112% between 2018 and 2024 (Figure 1b). APAC exhibited the most pronounced relative growth, with production rising from 182,380 tonnes in 2018 to 752,160 tonnes in 2024, highlighting the rapid scaling of intensive systems in the region. Nevertheless, the Americas remain the dominant contributor to cumulative global production, with an estimated total output of 5.95 million tonnes over the same period. From 2018 to 2021, global production increased steadily, supported by strong growth in APAC; however, between 2021 and 2023, production levels stabilized, reflecting contrasting regional dynamics. In 2023, a 12% decline in production in the Americas—associated with the effects of El Niño, including elevated temperatures, altered rainfall patterns, and shifts in harvest calendars was partially offset by production gains in EMEA and APAC. In 2024, global production reached record levels, with increases of 22% in APAC and 12% in EMEA, while production in the Americas returned to levels comparable to those observed in 2021. These trends, reported by the International Blueberry Organization (IBO), underscore both the resilience and vulnerability of global blueberry production systems and highlight the growing importance of region-specific adaptation strategies under increasing climatic variability.

3. Materials and Methods

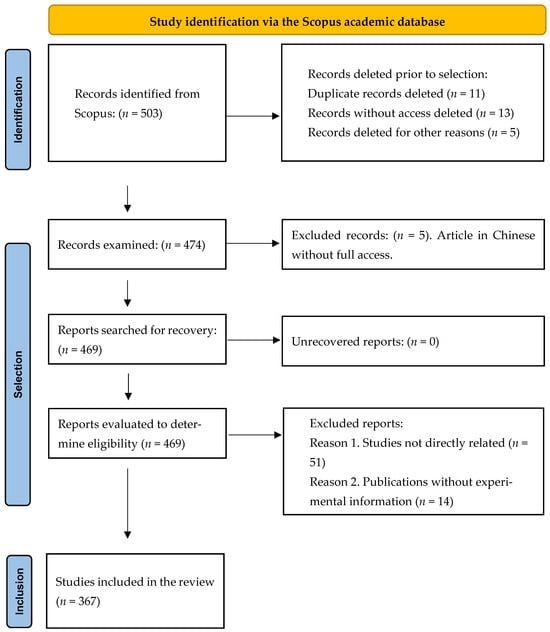

The systematic review was conducted following the PRISMA guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) to ensure a transparent, structured, and reproducible process in the identification, selection, and analysis of scientific literature related to the integrated management, sustainability, and technological innovation of blueberry (Vaccinium spp.) cultivation [14,15]. The methodological process comprised four main stages: (i) identification of documents in scientific databases, (ii) screening and selection according to inclusion and exclusion criteria, (iii) data extraction and systematization, and (iv) qualitative and quantitative analysis of reported trends and results (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

PRISMA workflow for systematic reviews.

To identify relevant studies, an exhaustive search was conducted in the Scopus database, selected for its broad coverage of peer-reviewed scientific literature related to physiology, agronomic management, sustainability, and technological innovation in blueberry (Vaccinium spp.) cultivation [16]. The search strategy was developed based on Boolean logic principles, combining controlled descriptors and free terms to maximize the sensitivity and specificity of results [17]. Synonyms and related terms were considered for the study’s main analytical dimensions: propagation, nutrition, irrigation, plant health management, physiology, harvest, postharvest, sustainability, and production-applied technology. The construction of the search equation was validated with the support of specialists in protected agriculture and bibliometrics, ensuring its scientific relevance. In Scopus, the advanced search used the following query:

TITLE-ABS-KEY (blueberry OR “Vaccinium corymbosum” OR “Vaccinium spp.”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“protected cultivation” OR “protected agriculture” OR “greenhouse” OR “tunnel” OR “shade net” OR “net house” OR “agribusiness” OR “fair trade” OR “processing”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (irrigation OR fertigation OR fertilization OR “nutrient management” OR pruning OR training OR “crop management” OR “harvest” OR “postharvest” OR “storage” OR “shelf life” OR “diseases” OR “pests” OR “crop protection” OR “biological control” OR “Transformation” OR “Commercialization” OR “Marketing” OR “export” OR “markets”).

The search covered the period 1987–2025, with no geographical restrictions, and included documents written in English, Spanish, and other languages. The retrieved records were exported in CSV (Comma-Separated Values) and RIS (Research Information Systems) formats for subsequent screening, bibliometric analysis, and systematic review.

3.1. Selection and Evaluation Process

The selection process followed the PRISMA 2020 guidelines to ensure transparency and reproducibility. Records retrieved from Scopus were imported into Microsoft Excel and Mendeley for de-duplication and reference management. In the initial phase, duplicate records (n = 11), records without full-text access (n = 13), and records excluded for other reasons (n = 5) were removed. Subsequently, three reviewers independently conducted a two-stage assessment: (i) title and abstract screening, and (ii) full-text review, applying the predefined inclusion criteria for studies on integrated management, sustainability, physiology, and technological innovation in Vaccinium spp. Each record was coded in Excel (Yes = 1; No = 0; Partial = 2), and discrepancies were resolved by consensus. The entire process, including reasons for exclusion, was documented to ensure traceability and methodological rigor.

3.2. Eligibility Criteria

Studies were considered eligible if they met the predefined criteria based on Boolean operations using search terms related to propagation, physiology, nutrition, irrigation, integrated pest and disease management, harvest, postharvest, sustainability, and technological innovation in Vaccinium spp. The eligibility criteria ensured the collection of comprehensive, high-quality evidence on integrated, sustainable, and technologically innovative blueberry management. Research from all geographic regions and production systems was included, provided it met the established methodological and thematic criteria. Peer-reviewed journal articles, conference proceedings, book chapters, and reviews published in English, Chinese, Portuguese, and Spanish between 1987 and 2025 were considered, with full-text access and verified relevance to the review objectives. At this stage, five documents in Chinese without full access were excluded.

3.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined to ensure the scientific, methodological, and thematic relevance of the analyzed documents. A total of 469 records were evaluated to determine eligibility, considering as potentially relevant those focused on the integrated management of blueberry (Vaccinium spp.) cultivation that addressed aspects such as propagation, physiology, mineral nutrition, irrigation, plant health management, sustainability, harvest, postharvest, or technological innovation. Studies that did not align with the review’s objective, lacked verifiable experimental or methodological information, or did not provide full-text access were excluded. The main reasons for exclusion from the total records evaluated were as follows: Reason 1, studies not directly related to the integrated management of Vaccinium spp. (n = 51); Reason 2, publications without sufficient experimental information (n = 14); and Reason 3, documents that did not address the main topics of the review (n = 37). The selection process, in accordance with PRISMA 2020 guidelines, ensured transparency and reproducibility of the analysis and is summarized in the flow diagram (Figure 1), which details the stages of identification, screening, and exclusion of studies

4. Results and Discussion

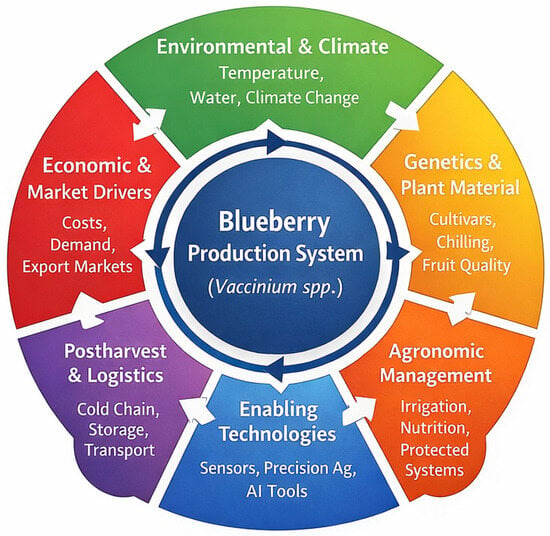

The present section integrates the most relevant findings derived from the systematic review, structured around six analytical axes: propagation and genetic improvement, agronomic and hydro-nutritional management, eco-physiological responses under controlled environments, harvest and postharvest processes, modeling through artificial intelligence (AI) and spectral vision, and environmental sustainability of the production system. These axes directly respond to the research questions guiding this review and reflect the main scientific and technological dimensions currently shaping blueberry production systems. To enhance interpretative coherence across these analytical dimensions, the results are contextualized within an integrated conceptual framework that highlights the functional interconnections among environmental conditions, plant material, agronomic practices, enabling technologies, postharvest logistics, and economic–market drivers. Importantly, this framework does not introduce additional analytical categories, but rather serves as a systems-level synthesis that supports the discussion of interactions, feedbacks, and trade-offs emerging from the reviewed evidence.

Overall, the results show substantial progress in yield performance, resource-use efficiency, and fruit quality, together with increased physiological resilience to thermal and water stress. Strategies based on microclimate modulation (radiation, temperature, and humidity), combined with non-thermal postharvest technologies, have proven effective in preserving texture, color, and bioactive compounds. Likewise, the integration of predictive models and AI strengthens fruit maturity monitoring and real-time decision-making, while life cycle assessment (LCA) and carbon footprint (CF) analyses identify critical environmental impact points and cost-effective pathways toward circularity and energy efficiency. Collectively, these findings consolidate a scientific–technical basis for designing more sustainable, traceable, and climate-smart blueberry production systems.

4.1. Conceptual Framework for Integrated Blueberry Production Systems

Figure 3 presents a conceptual framework that integrates the main dimensions governing contemporary blueberry (Vaccinium spp.) production, synthesizing the evidence generated across the six analytical axes addressed in this review. Rather than representing isolated management domains, the model conceptualizes blueberry production as a dynamic system in which environmental and climatic conditions, genetic and plant material, agronomic management, enabling technologies, postharvest logistics, and economic and market drivers interact continuously. This systemic perspective reflects the diversity of approaches identified in the reviewed studies and provides a unifying structure to interpret how advances in individual components contribute positively or negatively to overall system performance.

Figure 3.

Conceptual framework integrating the main components of modern blueberry (Vaccinium spp.) production systems.

A central feature of the framework is the transversal role of enabling technologies, which act as a functional bridge between biological processes, management decisions, and market requirements. Precision irrigation and fertigation systems, sensor networks, artificial intelligence tools, and spectral or imaging technologies support real-time monitoring, predictive decision-making, and resource-use optimization. As shown across multiple studies reviewed in this work, the effectiveness of these technologies depends on their alignment with cultivar characteristics, environmental constraints, and production objectives. Consequently, the framework highlights that technological innovation alone does not guarantee improved outcomes unless it is embedded within a coordinated agronomic and physiological management strategy.

The incorporation of economic and market drivers into the conceptual model emphasizes their feedback role in shaping production systems and technology adoption pathways. Market access, quality standards, postharvest requirements, and cost structures influence decisions related to cultivar selection, investment in infrastructure, and adoption of advanced management tools. At the same time, environmental sustainability considerations such as water-use efficiency, energy consumption, and carbon footprint interact with economic viability, reinforcing the need for integrated assessments. In this sense, the proposed framework provides a practical interpretative lens for understanding how productivity, quality, sustainability, and profitability converge in climate-smart blueberry production systems.

4.2. Innovations in Propagation, Plant Material Acquisition, and Genetic Improvement

Blueberry (Vaccinium spp.) is a perennial species of high economic value, whose genetic improvement aims to optimize yield, quality, and adaptation to agroclimatic conditions and market demands [18]. In the United States, studies on metaxenia (the effect of pollen on fruit characteristics) conducted with ten cultivars of highbush blueberry demonstrated that this phenomenon does not significantly alter fruit maturation or weight, except in self-fertile genotypes [19]. Variety evaluations in the Netherlands and the United States identified materials of high potential: ‘Reka’, ‘Chandler’, and ‘Brigitta Blue’ stood out for their productivity and extended postharvest life; ‘Elliott’ for its late harvest; and the MS 706, MS 271, MS 454, and MS 812 selections for their fruit size, quality, and earliness, being suitable for both fresh consumption and industrial use [20,21]. In China, the hybrid cultivar ‘Chasing Dream’ exhibited high yield and storage resistance [22], while the Polish program based on V. corymbosum focused on improving edaphoclimatic adaptation and fruit shelf life [23]. In Morocco, the cultivars ‘Gupton’, ‘Alix Blue’, and ‘Star’ showed good adaptation to local climatic conditions and significant differences in yield and quality, demonstrating the broad plasticity of the Vaccinium genus [24].

Although blueberry cultivation has traditionally relied on own-rooted plants, grafting has recently emerged as a complementary propagation strategy under specific agronomic conditions. Like other perennial fruit crops, the use of blueberry rootstocks can influence water-use efficiency, mineral nutrition, physiological performance, and fruit quality. Recent evidence reported by Zhu et al. [25], demonstrated that grafting blueberry cultivars onto different Vaccinium rootstocks significantly affected fruit quality, leaf mineral content, gas exchange parameters, xylem anatomical traits, and drought resistance. Certain rootstock enhanced photosynthetic performance and improved fruit quality while conferring greater tolerance to water stress compared with own-rooted plants. These effects were associated with differences in vascular structure and hydraulic conductivity, highlighting the importance of rootstock–scion interactions. Although grafting is not yet widely adopted in commercial blueberry production, these findings indicate its potential as a targeted strategy to improve fruit quality and stress resilience in challenging environments.

Micropropagation, an in vitro technique that allows the multiplication of genetically uniform and pathogen-free plants, has become an essential tool for producing high-quality plant material. In China, the use of Woody Plant Medium (WPM) supplemented with 0.1–2.0 mg L−1 of zeatin (ZT), partial illumination ranging from 2000 to 10,000 lux, and a temperature between 25 and 30 °C achieved up to 90% ex vitro rooting in moss treated with indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) or naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA) at concentrations of 1000–2000 mg L−1, in addition to developing a cold-storage method for viable explant conservation [26]. Another experiment, also conducted in China, using cultivars ‘Bluejay’, ‘Pink Lemonade’, ‘Sunshine Blue’, and ‘Top Hat’, showed that callus induction and shoot regeneration capacity depend on genetic constitution (polyploid hybridization), achieving survival rates above 90% in peat substrate [27]. In Austria, in vitro regeneration combined with thermotherapy proved effective in reducing viral and phytoplasma infections [28]. In Chile, cultures treated with colchicine (C22H25NO6) generated six vigorous and adaptable clones, recommended for genotype–environment evaluation across different agroclimatic zones [29].

Biotechnological advances have broadened breeding perspectives. Virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) has proven to be an efficient method for analyzing gene function and accelerating the development of new cultivars [18]. At the University of Florida, crosses among V. corymbosum, V. darrowii, and tetraploid Southern Highbush (SHB) lines incorporated morphological traits favorable for mechanical harvesting pedicel length, cluster compactness, and growth habit thus reducing costs and labor dependence [30]. Meanwhile, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) promotes sanitary certification programs to prevent the spread of pathogens such as Phytophthora ramorum and Blueberry Shock Virus (BlShV). Its Vaccinium clonal collection, comprising 600 accessions, was relocated to pots under controlled conditions of substrate, pruning, and propagation [31].

Overall, innovations in blueberry propagation and breeding reflect the convergence of biotechnology, plant health, and climate adaptation. However, significant challenges remain: the limited functional characterization of genes related to fruit quality and stress resistance, the scarce multiyear validation of micro propagated clones, and the lack of international standardization of in vitro protocols. The integration of molecular tools with agronomic evaluation, phytosanitary control, and genetic traceability is essential to advance toward a globally harmonized and resilient blueberry production system.

4.3. Advances in Agronomic Practices and Cultural Management Strategies for Optimizing Blueberry (Vaccinium spp.) Cultivation

The cultural management of blueberries (Vaccinium spp.) encompasses a set of agronomic decisions that determine productivity, fruit quality, and system sustainability [32]. Factors such as substrate preparation, planting system, mulching, shading management, and phenological cycle regulation are key to the technical and economic success of commercial plantations. In Slovenia, three varieties were evaluated under raised beds and pots placed in high tunnels or under hail nets. The tunnels advanced fruit ripening by 6–18 days but reduced yield and bioactive compound content. In contrast, hail nets improved fruit quality and antioxidant concentration, while pot cultivation did not affect firmness or growth, validating its suitability for intensive systems. The study suggests that hail nets represent a sustainable management practice under climate change conditions [33].

Blueberry production occurs both in open fields and under controlled-environment greenhouses, enabling continuous fruit supply. To maintain high commercial quality, good management practices should include proper soil preparation, balanced nutrient supply, and the use of organic or mineral amendments to prevent physiological deficiencies [32]. In Oregon (USA), different substrates were compared for pot cultivation, including mixtures of peat moss, coconut fiber, and fir bark. Media containing peat (peat) or coir favored growth and moisture/nutrient retention, whereas high bark proportions increased desiccation and reduced nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) uptake, affecting vegetative development. Thus, peat and coir are consolidated as optimal substrates for intensive and greenhouse production [34].

In China, the expansion of cultivation in acidic soils has faced challenges related to inadequate site selection, limited availability of high-quality planting material, and low varietal diversity. The establishment of demonstration plantations is recommended as training and knowledge transfer spaces aimed at strengthening sustainable production systems [35]. Similarly, the introduction of biodegradable mulches such as the biopolymer Mater-Bi (derived from plant oils and starches) has shown positive effects on moisture conservation, soil fertility, and weed control, while replacing conventional plastics and reducing waste pollution [36]. This material, which naturally decomposes, represents a cultural practice aligned with circular economic principles applied to horticulture.

The use of shade nets of different colors and opacities also influences production planning. White and red nets with moderate coverage (40–60%) delayed harvest by a few days without affecting yield or quality, allowing better commercial management and preventing radiation and heat stress damage. In contrast, excessive shading reduced fruit size and sweetness [37]. Another greenhouse study evaluated the induction of flowering using hydrogen cyanamide (CH2N2) and mineral oil (MO) in three varieties. Results showed earlier and more uniform flowering in ‘Georgiagem’ and ‘Climax’, although high doses caused bud necrosis and reduced yield, highlighting the need for precise regulator management [38]. This practice is useful for synchronizing production cycles when winter chill accumulation is insufficient.

Overall, advances in planting and cultural management practices for blueberry show a trend toward technological sustainability, combining innovation in substrates, coverings, mulches, and physiological regulators. However, the systematic review reveals significant gaps: most studies lack multi-year analyses, regional comparisons, and standardized environmental performance metrics. Despite observed progress, challenges remain regarding energy balance optimization in protected crops, life-cycle assessment of biodegradable materials, and the integration of sustainability indicators into management systems. Therefore, it is proposed to advance toward a cultural management model based on quantitative and eco-physiological evidence that links productivity, water-use efficiency, and climate resilience, consolidating blueberry as a reference crop in global sustainable horticulture.

4.4. Integrated Irrigation, Fertigation, and Mineral Nutrition Strategies in Blueberry (Vaccinium spp.) Cultivation

Water and nutrient management in blueberry (Vaccinium spp.) have shifted toward more efficient and sustainable production schemes, integrating mineral nutrition, precision irrigation, and smart technologies. Among evaluated strategies, the use of mineral biostimulants such as silicon (Si) has shown notable physiological and biochemical effects. Comparative studies found that potassium silicate (K2SiO3) exhibited higher absorption than wollastonite (CaSiO3), reaching foliar concentrations of up to 370 ppm in the cultivar ‘Bluegold’, whereas ‘Earliblue’ and ‘Liberty’ reached only 34–35% of the overall average. This increase was associated with higher levels of phenolic compounds and microbial enzymatic activity, highlighting the potential of silicon to enhance fruit functional and antioxidant quality [39].

Nitrogen (N) type and source have a decisive influence on crop physiology and productivity. Exclusive ammonium (NH4+) supply promoted the accumulation of N, phosphorus (P), magnesium (Mg), sulfur (S), copper (Cu), manganese (Mn), and boron (B) in leaves and increased chlorophyll a and total sugars compared with nitrate (NO3−). In a split-root system, nitrogen use efficiency doubled: half the NH4+ dose produced yields equivalent to the full supply, confirming the combined influence of nitrogen source and application mode on crop physiology [40].

Soil and substrate management also play a key role in system productivity. In the Mekong Delta, ancient, degraded soils (AA) achieved only 81% of the yield recorded in recent fertile soils (RA). Nitrogen omission reduced yield by 47% (RA) and 39% (AA), as well as stem biomass (70% and 42%) and leaf biomass (59% and 46%), confirming the critical role of nitrogen fertilization [41]. In container systems, coconut coir showed limitations due to initial salinization: fertilization with calcium nitrate (1.75 g·L−1) or monoammonium phosphate (2.38 g·L−1) did not reduce sodium (Na) levels or improve biomass in the ‘Snowchaser’ cultivar [42]. In contrast, organic management without mineral nitrogen fertilization and with 20% organic matter in the substrate (S2) enhanced canopy volume, leaf area, and photosynthetic efficiency in the ‘Climax’ cultivar, validating organic management under protected conditions as a sustainable alternative [43].

Under hydroponic conditions, the cultivar ‘Biloxi’ achieved maximum yield at an electrical conductivity (EC) of 1.5 dS·m−1 and a NO3−/NH4+ ratio of 30/70, with soluble solids of 14.4–15.4 °Brix. Smaller fruits accumulated more anthocyanins (141 mg·100 g−1) than larger ones (85 mg·100 g−1), reinforcing the relationship between mineral nutrition and functional fruit quality [44].

Water management has been addressed through deficit irrigation and pulse optimization strategies. In sandy soils with pine bark, increasing irrigation frequency from 2 to 10 pulses per day reduced leaching fraction from 46% to 30%. The ‘Jewel’ cultivar showed losses below 20%, compared with ‘Emerald’ (>50%), due to a denser root system [45]. Applying controlled deficit irrigation (80% of evapotranspiration) under plastic tunnels improved firmness and soluble solids without reducing commercial quality, though with a slight decrease in titratable acidity [46]. Moreover, water restriction increased phenolic compound synthesis, particularly delphinidin-3-acetylhexoside, emphasizing the role of moderate water stress as a driver of functional quality [47].

Technological developments have enabled the consolidation of smart fertigation strategies. In China, the implementation of Internet of Things (IoT)-based automatic systems reduced water consumption by 35–45%, fertilizer use by 25–35%, increased yield by 10–15%, and reduced labor by over 60%, while also lowering agricultural pollution [48]. In mountain orchards, a decision-support system with moisture sensors and water balance algorithms calculated transpiration and irrigation volume in real time, activating emitters automatically without human intervention [49]. Additionally, plant bioelectrical potentials have been explored as physiological indicators: signals between −50 and −250 mV, responding within milliseconds, correlated with stomatal closure and reduced conductance, constituting an early water stress detection system for fruit crops such as blueberry, avocado, and olive [50]. Foliar nutrition also plays a decisive role in postharvest quality. Preharvest applications of 7.8 g·L−1 calcium (Ca2+) increased Ca content in leaves and fruits of blueberries grown under tunnels, establishing a direct correlation between Ca concentration and fruit firmness. This effect was associated with an increase in low-methoxyl pectin (LMP), a key component of fruit texture, demonstrating that both dosage and cultivation environment (tunnel, net, or open field) directly influence commercial quality and shelf life [51].

In summary, integrated irrigation, fertigation, and mineral nutrition strategies for blueberry demonstrate a convergence between physiological efficiency and technological sustainability. Scientific evidence confirms that synchronization between nutrient source and application method, irrigation frequency, and water management technology are key determinants of productivity and fruit quality. However, knowledge gaps remain regarding long-term evaluation of combined nutritional and water management effects on environmental footprint, energy efficiency, and system resilience. Advancing toward models based on integrated physiological indicators and real-time monitoring technologies will optimize resource use and strengthen sustainable production systems in the face of climatic and water availability constraints.

4.5. Integrated Approaches for the Sanitary and Phytosanitary Management of Blueberries (Vaccinium spp.)

Sanitary and phytosanitary management of blueberry (Vaccinium spp.) is a fundamental pillar for crop sustainability, given the rise in fungal, bacterial, and viral diseases, as well as the emergence of new pests that threaten productivity and fruit quality. Recent literature shows a global effort to identify key pathogens, develop integrated management strategies, and strengthen both molecular diagnostics and the genetic resistance of cultivars. In Chile, application of Koch’s postulates enabled the first identification of Chondrostereum purpureum as the causal agent of silver leaf disease and xylem necrosis in the cultivar ‘Brigitta Blue’. The pathogen spread rapidly between 2005 and 2006, affecting 21 orchards and causing whole-plant death with high economic impact [52]. In parallel, in China, Botryosphaeria dothidea was detected as the causal agent of shoot blight and dieback, a pathogen previously associated with species such as sycamore and olive [53]. In Georgia (USA), Xylella fastidiosa subsp. fastidiosa was confirmed as the cause of bacterial leaf scorch (BLS), while Ectophoma multirostrata was reported as a new causal agent of stem canker, establishing V. corymbosum as a global host [54,55].

Likewise, Phytophthora cinnamomi was detected in 2014 as the causal agent of root and crown rot in young blueberry plants in China [56]. Resistance screening identified tolerant cultivars (‘Aurora’, ‘Legacy’, ‘Liberty’, ‘Reka’, ‘Overtime’, and ‘Clockwork’) and susceptible ones (‘Bluetta’, ‘Bluecrop’, ‘Bluegold’, ‘Blue Ribbon’, ‘Cargo’, ‘Draper’, ‘Duke’, ‘Elliott’, ‘Last Call’, ‘Top Shelf’, and ‘Ventura’), the latter being discouraged in clayey or poorly drained soils [57]. In parallel, protocols were developed to assess germplasm and the efficacy of chemical and biological agents for controlling root rot [58,59]. Among foliar diseases, leaf rust caused by Thekospora minima was documented in Oregon (USA), affecting nurseries and greenhouses and causing early defoliation; this disease is considered a quarantine pest in the European Union, restricting international trade [60]. In Europe, Pucciniastrum vaccinii was also reported, with differences in cultivar susceptibility and natural resistance observed in V. cylindraceum [61]. In Canada, Exobasidium vaccinii, the causal agent of red leaf, showed limited incidence thanks to cultural practices such as pruning and the natural resistance of lowbush blueberry [62].

Pest control has been another major research front. In Canada, the midge Dasineura oxycoccana showed reproductive isolation between V. corymbosum and V. macrocarpon populations due to differences in sex pheromones [63]. In Poland, the management of soft scales (Parthenolecanium spp.) using mechanically acting products within Integrated Pest Management (IPM) showed efficacy equal to or greater than neonicotinoid insecticides, consolidating a sustainable strategy [64]. The bacterium Xylella fastidiosa, transmitted by the glassy-winged sharpshooter (Homalodisca vitripennis, GWSS), exhibited varietal differences in infection intensity [65]; moreover, strains of subspecies multiplex and pauca were detected in Spain and Italy with host-shift potential [66]. Advances in molecular diagnostics have enabled the identification of the distribution of these subspecies [67] and whole-genome sequencing [68]. For its control, zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles Zinkicide™ TMN110 (ZnK) reduced BLS severity under controlled conditions [69].

Fungi of the genus Colletotrichum pose a growing threat. In Poland, C. fioriniae was reported for the first time as an anthracnose agent in 2016 [70], and C. acutatum showed a low correlation between foliar and fruit symptoms [71]. In China, premature defoliation caused by Corynespora cassiicola was linked to high humidity and temperature in greenhouses [72,73]. Fruit brown rot caused by Monilinia vaccinii-corymbosi remains the primary phytosanitary problem in North America. Sources of resistance have been identified in wild diploid populations [74], along with floral resistance mechanisms in the gynoecial canal [75]. Chemical control with fenbuconazole, azoxystrobin, and triforine showed variable efficacy depending on phenology [76,77], while early pollination has been proposed as a preventive measure [78]. In addition, the germination of pseudosclerotia and the development of apothecia depend on the host cultivar and its phenological stage [79,80].

In Mexico, Neofusicoccum parvum was identified as the causal agent of stem blight under tunnels and in greenhouses [81], and in China a new species, Lasiodiplodia vaccinii, adapted to warm conditions, was described [82]. In trials with Botryosphaeria, fertilization increased lesion length, whereas fungicide use significantly reduced it [58,59]. Transcriptomic analysis of Pestalotiopsis microspora revealed 727 transcription factors, of which 200 were associated with defense mechanisms and 45 with cellular regulation, highlighting seven genes involved in α-(1,3)-glucan biosynthesis, a key component in immune response [83].

Among plant-parasitic nematodes, the ring nematode Mesocriconema ornatum was found to exacerbate blueberry replant disease (RBD), with higher reproduction rates under low initial inoculum [84]. Likewise, Paratrichodorus renifer and Pratylenchus penetrans reduce yield in susceptible cultivars [85]. In biological control, Steinernema scarabaei showed effectiveness comparable to neonicotinoids against Anomala orientalis [86], while Clonostachys rosea was effective against Botrytis cinerea in V. angustifolium, including bee-vectored dissemination [87,88]. In Chile, Steinernema australe was proposed as a biocontrol agent for the weevil Aegorhinus superciliosus [89], and the endophytic fungi Codinaeella EC4 and Schizophyllum commune showed potential against Diaporthe vaccinii and Fusarium commune, respectively [90,91]. The application of organic nitrogen sources reduced wilt caused by Fusarium solani in the ‘Legacy’ cultivar [92].

For the southern red mite (Oligonychus ilicis), the predators Phytoseiulus persimilis and Neoseiulus californicus were identified as promising species under greenhouse conditions [93]. Studies of relative insecticide toxicity showed that broad-spectrum products severely affect biological control agents such as Aphidius colemani, Orius insidiosus, Chrysoperla rufilabris, and Hippodamia convergens, whereas inputs approved for organic agriculture are compatible [94]. In Canada, red sorrel pollen was observed to enhance germination of Botrytis cinerea, although pronamide application did not improve productivity [95]. Finally, spectral fluorescence analysis enabled nondestructive detection of B. cinerea in fruit during harvest and postharvest through infrared reflectance variations associated with mycelial growth [96].

Taken together, research demonstrates significant progress toward a comprehensive plant health approach that combines molecular diagnostics, genetic resistance, biological control, and the rational use of agrochemicals. However, key challenges persist limited multiyear evaluation of the efficacy of biological agents, a shortage of studies on microbiome–pathogen interactions, and the need to quantify the environmental impacts of chemical strategies. Advancing toward health management based on principles of microbial ecology, early molecular surveillance, and field pathophysiological validation will strengthen the phytosanitary resilience of blueberries in the face of climate change and new scenarios of production intensification.

4.6. Crop Physiology and Eco-Physiological Regulation Under Controlled Environments

The study of eco-physiological responses of blueberries (Vaccinium spp.) under protected systems is essential to optimize productivity, quality, and adaptation to climate change and to variations in radiation, temperature, and water availability. Light, thermal, and phenological manipulation together with biostimulants and emerging technologies has become a set of tools for synchronizing vegetative and reproductive cycles and enhancing the crop’s physiological resilience.

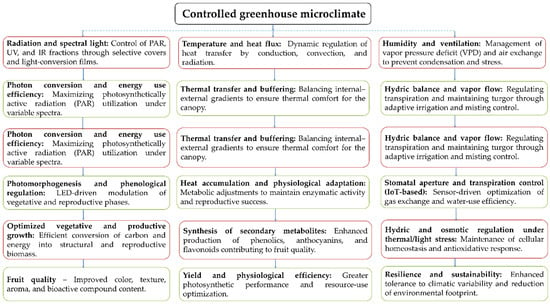

Within this framework, light down-conversion has proven effective in modifying the spectral quality under cover conditions. In controlled tunnels over one growing season, films enriched in red wavelengths significantly increased biomass in the ‘Duke’ cultivar and suggested a positive effect on yield, in addition to favoring the accumulation of carbohydrate reserves for the following cycle. However, its adoption requires multi-year validation with adequate replication to confirm physiological benefits and cost–benefit relationships [97]. In this context, the eco-physiological engineering framework of blueberry cultivation under controlled environments (Figure 4) integrates the dynamic interactions between microclimate and crop physiology, emphasizing how energy, water, and radiation fluxes regulate key processes such as photomorphogenesis, transpiration, and secondary metabolite synthesis, which directly influence fruit quality and production efficiency. This systemic perspective underscores the need for coordinated management of spectral radiation, ventilation, and humidity, together with thermal and water control strategies, to achieve a functional balance between growth, yield, and physiological sustainability.

Figure 4.

Eco-physiological engineering diagram of blueberries under cover.

In the hydric dimension, the integration of electrodialysis and forward osmosis (EDFO) has emerged as an advanced strategy for nutrient recovery and wastewater reuse. In southern highbush blueberry, irrigation with EDFO-treated water did not alter plant growth or substrate ionic balance, maintaining pH within the optimal range (4.5–5.5) and an electrical conductivity (EC) slightly above 2 dS·m−1, which can be easily managed through periodic flushing. From a physiological standpoint, stable pH and EC favored the balanced uptake of macro- and micronutrients (particularly N, K, Ca, and Mg), preventing ionic competition and cell dehydration associated with excess salinity. Likewise, controlled ion concentrations may have enhanced leaf water potential efficiency, maintaining stomatal aperture and transpiration rate (E) within optimal ranges. The use of reclaimed water did not significantly modify stomatal conductance (gs) or CO2 assimilation (Aₙ), suggesting active osmotic adjustment that preserves membrane integrity and photosynthetic capacity under moderate EC conditions. Moreover, the EDFO system removed over 90% of pharmaceuticals and pesticides, thereby reducing pressure on freshwater sources and contributing to nutrient-cycle closure without compromising the physiological performance of the crop [98].

The gradual presentation of pollen in V. corymbosum can be exploited to schedule pollination, with bumblebees (Bombus spp.) proving more efficient than honeybees (Apis mellifera). In greenhouses, the combination of protected environments and managed hive placement increased yield and quality, improving fruit set and ripening uniformity compared with open-field conditions [99]. In phenological regulation, the application of 0.67% (v/v) hydrogen cyanamide (HC) during dormancy after fulfilling approximately two-thirds of the chilling requirement advanced budburst by 15–19 days, shortened flowering and harvest periods, and increased total yield by 21–42% (early yield by 43–163%), without detrimental effects on firmness, vitamin C, anthocyanins, or phenolics. The mixture of HC with gibberellic acid (GA3), ethephon, mineral oil, or KNO3 provided no advantages and sometimes reduced yield [100].Controlled trials with ‘Duke’, ‘Bluecrop’, and ‘Elliott’ confirmed that long days (16 h, 22 °C) promote vegetative flushes without floral induction or endodormancy, while short days (8 h) induce flower buds from week 2 and dormancy from week 4. After 900 h of chilling at 4 °C, budburst occurred approximately 6 days later, flowering at 26 days, and harvest between 65 and 130 days post-budburst, depending on cultivar supporting a darkening–vernalization protocol to induce buds and dormancy, followed by cultivar selection according to market windows and targeted pollination management [101,102].

Stomatal thermotolerance defines an operational window: stomatal function exhibited an optimum between 30 and 35 °C under moderate shading (20–30%), conditions that maximize CO2 assimilation, photosynthetic efficiency, and thermal dissipation, providing criteria for selecting heat-tolerant genotypes and designing greenhouses in warm or high-thermal-load regions [103]. In environments with high UV-B radiation (or coverings that transmit it), Vaccinium uliginosum accumulated more photoprotective compounds (“UV filters”) but showed a ~23% reduction in seasonal photosynthesis and impairment of photosystem II (PSII) and likely the Calvin cycle. Consequently, the use of UV-B-filtering plastics or nets, moderate shading, and irrigation and nitrogen adjustments are recommended to sustain chlorophyll and antioxidants while protecting photosynthetic capacity and yield [104].

Shade net management entails trade-offs: higher shading increases chlorophyll content (greener leaves) but reduces photosynthetic efficiency; fruits may grow slightly larger but ripen more slowly and have lower sugar content (°Brix). Dark shade nets intensify these effects, while white or light nets (25–50%) protect against excess radiation with minimal quality penalties, making them useful for adjusting harvest windows [105]. In source–sink balance, maintaining approximately five leaves per fruit enhances fruit filling, size, °Brix, and earliness; reinforcing pollination one day after the first pass increases seed number and fruit weight. These practices are implemented through selective pruning and scheduled thinning, improving uniformity and reproductive efficiency [106].

In warm climates, modulation of temperature and photoperiod combined with perennial management (pruning plus strategic fertilization) affects floral induction, budburst, and fruiting, allowing production to be advanced or concentrated in higher-value periods. The selection of low-chill cultivars and staggered production blocks are effective tools to align phenology with market demand [107]. In parallel, bio stimulants have shown anti-stress effects: seaweed extracts in greenhouse conditions increased antioxidant enzyme activity by up to 20% under drought, without altering chlorophyll or foliar nutrients [108], while applications of methyl jasmonate and abscisic acid enhanced fruit antioxidant content without affecting yield, improving the nutraceutical profile [109].

Taken together, the evidence supports an eco-physiological engineering framework for blueberry cultivation under protective covers: (i) prudent spectral management (light conversion) with multi-year verification, (ii) closed water and nutrient cycles (EDFO) with EC monitoring, (iii) phenological regulation based on short-day/vernalization/HC protocols and precise pollination management, (iv) microclimate design (moderate shading and UV-B filtering) that preserves PSII function, and (v) selective use of bio stimulants to mitigate abiotic stress. Prioritizing these elements calibrated to cultivar and market window enables gains in earliness and fruit quality without compromising the physiological sustainability of the production system.

4.7. Blueberry Harvesting: Transition to Mechanized and Assisted Systems

Harvest represents one of the most critical stages in the production chain of blueberries (Vaccinium spp.), due to its high labor demand and its direct impact on postharvest physiology and commercial fruit quality. Recent literature converges toward partial or assisted mechanization, seeking to reduce labor costs without compromising firmness, anthocyanin content, or cellular integrity of the berries. In tunnel-based systems, assisted harvesting using portable electric shakers and soft capture surfaces increased the picking rate to 81.3 berries·min−1, although with 30.6% unripe fruits. Adjusting the detachment speed to 900 rpm for 1.2 s improved overall efficiency to 80.7%, demonstrating the potential of this method to balance productivity and selectivity [110]. This hybrid approach combines the operator’s perceptual precision with the controlled force of the device, reducing physical strain and improving consistency in handling factors that directly influence the preservation of cell turgor and cuticle integrity. As shown in Table 1, electrical assistance and soft-capture mechanisms enable progress toward intermediate mechanization with minimal quality loss, while impact reduction strategies and optical sorting contribute to maintaining the structural integrity and ripeness uniformity of the fruit key elements for standardizing the harvesting system.

Table 1.

Mechanized harvesting, mechanical damage, and optical sorting.

From an applied perspective, Table 1 highlights that assisted harvesting with controlled vibration and soft-catch systems currently offers the best compromise between labor efficiency and fruit quality preservation. For mechanical damage mitigation, impact-reduction strategies (reduced drop height and padded contact surfaces) are the most effective, whereas optical selection technologies provide the highest reliability for ripeness uniformity and harvest timing in fresh-market blueberries.

The main challenge in mechanization is impact damage, which alters membrane permeability and accelerates oxidative processes. Using instrumented sensors (BIRD), it was determined that more than 30% of impacts originated from retention plates and 20% from the empty box. The inclusion of cellular silicone padding and reducing drop height from 101 to 50 cm significantly decreased bruising. In “rabbiteye” cultivars, redesigning plant architecture reduced fruit loss to the ground from 24% to 17%, highlighting the need to synchronize cluster morphology with detachment dynamics [111,112].

At the separation stage, incorporating a dual-fan plenum with in-cab speed control allowed adjustment of the airflow (~18 m·s−1), removing debris without fruit loss due to the higher terminal velocity (≈15.6 m·s−1) of berries compared with leaves and stems. This innovation reduces surface microbial contamination and, physiologically, minimizes postharvest rot risk by limiting epidermal damage and cuticular wax loss [113]. In parallel, portable optical technology has emerged as a tool for defining the optimal harvest point. A spectral index based on three wavelengths (~680, 740, and 850 nm) classified berries with >93% accuracy, correlating with physiological ripening changes: increased anthocyanins (≈1011–1060 mg·100 g−1 FW), higher soluble solids (°Brix), pH, and reducing sugars (glucose and fructose), along with decreased titratable acidity and reduced flavanols and phenolic acids, which peak in unripe fruits. These biochemical transformations reflect activation of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) and controlled pectin degradation key processes for designing predictive algorithms of physiological maturity [114].

From an economic and operational perspective, full mechanization for the fresh market remains constrained by profitability. Simulation models indicate that adoption would be feasible with combined reductions of 20–30% in price gaps, labor costs, and yield losses [115]. Progress toward efficiency depends on the convergence of innovations in mechanical design (shock-absorbing contacts, fall control, adaptive ventilation) and mechanization-oriented genetic improvement focused on open plant architecture, loose clusters, small stem scars, persistent wax, and high firmness [116]. Additionally, harvest planning can benefit from multi-objective models based on fuzzy logic and evolutionary algorithms (NSGEA) that simultaneously optimize profitability and sustainability, considering greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, waste, labor availability, and climatic variability. In Canadian systems, this approach outperformed traditional deterministic models, providing an analytical foundation for adaptive decision-making [117].

In summary, the blueberry production system is evolving toward progressive mechanization supported by four pillars: (i) intelligent human assistance as an intermediate phase, (ii) ergonomic redesign using impact-absorbing materials, (iii) optical diagnostics for determining the physiological harvest point, and (iv) mechanization-oriented breeding. This process not only reduces labor dependency but also integrates mechanical engineering and fruit physiology to achieve a balance between efficiency, postharvest quality, and technological sustainability.

4.8. Post-Harvest Technologies and Dynamics of Blueberry (Vaccinium spp.) Storage and Marketing

Non-thermal technologies and hybrid preservation methods represent the core of post-harvest innovation in blueberries. Table 2 summarizes the main treatments developed, their operating parameters, matrices, and validation scales, highlighting the trend toward gentle physical processes with high retention of bioactive compounds and energy efficiency. From an applied perspective, Table 2 indicates that the suitability of non-thermal technologies strongly depends on the dominant postharvest objective and the product format. For anthocyanin retention and preservation of bioactive compounds, high hydrostatic pressure (HHP/HPP) and manothermosonication emerge as the most promising approaches, as they consistently maintain or enhance anthocyanin levels while limiting enzymatic degradation. For microbial safety, HHP/HPP provides the most robust and broad-spectrum inactivation, while cold atmospheric plasma (CAPP) and pulsed light (PL) are particularly effective for surface decontamination of fresh fruit when dose–cultivar interactions are properly managed. In contrast, PEF/MPEF technologies are best suited for liquid matrices where continuous processing and nutrient retention are prioritized. Overall, Table 2 highlights the need to align technology selection with specific quality and safety goals rather than adopting a single universal postharvest solution.

Table 2.

Non-thermal technologies and process routes (post-harvest/processing).

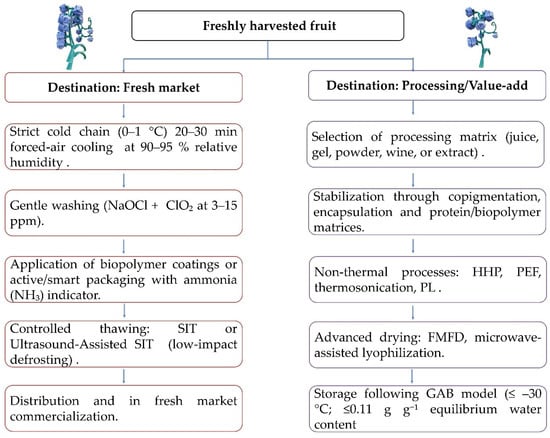

The competitiveness of fresh and processed blueberry depends on postharvest strategies that preserve texture, color, and aroma; ensure safety; stabilize phenolic pigments; and valorize by-products within a circular-economy framework. This synthesis based on a systematic review of recent and seminal studies organizes the evidence into four axes: (i) preservation of sensory quality with minimal degradation of anthocyanins and phenolics; (ii) microbiological control through low-impact physical/chemical treatments; (iii) pigment stabilization via copigmentation, encapsulation, and biopolymeric/protein matrices; and (iv) by-product valorization into active ingredients and packaging. Figure 5 summarizes the technological flows from harvest to fruit commercialization or processing, highlighting the integration of cold chains, non-thermal treatments, and by-product valorization routes under a circular-economy approach.

Figure 5.

Technological flow of blueberries from harvest to marketing or processing.

(i) Preservation of texture, color, and aroma with minimal degradation of anthocyanins/phenols: The sensory and nutraceutical preservation of blueberries is highly dependent on the technological route, cultivar, and maturity stage. In juice processing, the use of pectinases simultaneously increased yield (≈91%) and anthocyanin concentration (≈4287 mg/L), although with higher astringency and acidity, requiring fine balance between extraction efficiency and sensory quality [131]. In low-sugar jams, high hydrostatic pressure (HHP) preserved vitamin C and polyphenols for 68 days at 4 °C, maintaining representative levels (vitamin C ≈ 14.17 mg/mL; phenolics ≈ 1.15 mg/mL; flavonoids ≈ 4.77 mg/mL; anthocyanins ≈ 0.45 mg/mL) [132], confirming the advantage of non-thermal technologies over HTST in preserving heat-sensitive compounds [120,125,133].

The cold chain is critical: freezing at −80 °C better preserved vacuolar water and pectin, reducing drip loss compared to −20/−40 °C or liquid N2 [134], while slow thermal induction thawing (SIT) and its ultrasound-assisted variant (UASIT) maintained anthocyanin and °Brix levels, with UASIT showing higher efficiency without sensory penalties [129]. In whole fruit for fresh consumption, pulsed light (PL, 6 J/cm2) maintained firmness and reduced decay for six weeks at 0.5 °C and 90–95% relative humidity [121], while biopolymeric coatings (chitosan/pectin) decreased decay (−33%) and weight loss (−22%) after 16 days [135]. Aromatic profiling has identified 618 VOCs, with β-ionone and 2(5H)-furanone associated with sweet/fruity notes, and carotol/1-hexanol as biomarkers differentiating wild from cultivated genotypes [136].

In dried matrices, combining microwave and assisted freeze-drying (quartz or SiC) reduced processing time by >50% while retaining >80% total monomeric anthocyanins (TMA) and >75% total phenolics [137]. Freeze–microwave freeze-drying (FMFD) outperformed spray drying (SD) in TMA and TPC when using maltodextrin and whey isolate as carriers [130]. Mixed freeze-dried powders showed stability with ≈23.9% anthocyanin loss after 12 weeks [138], and GAB models defined critical moisture and temperature conditions for storage [139,140]. Moderate dehydration prior to winemaking (≈30% weight loss) increased anthocyanins (+25.9%) and phenolics (+16.1%), improving the aromatic profile [141], confirming the process-design flexibility according to product destination.

Structural and genetic factors explain differential responses: the greater firmness of the ‘Star’ cultivar compared with ‘O’Neal’ was associated with differential expression of pectin lyase (VcPL41/VcPL65) and soluble pectin treatment with 2% CaCl2 delayed softening and abscisic acid (ABA) accumulation [142]. In terms of degradation, Raman spectroscopy revealed accelerated anthocyanin losses at elevated pH, temperatures >65 °C, or prolonged UV exposure [143]; thermosonication (600 W; 60 °C) increased total phenolic content (TPC) by +139%, flavonoids by +252%, and anthocyanins by +94% [144]. These results confirm that the “triangle” of pH–temperature–light, together with cell-wall architecture and matrix–process interactions, governs chromatic stability and texture retention.

(ii) Microbiological control using low-impact physical/chemical treatments: Pathogen and spoilage control in blueberries have evolved toward mild combination treatments that minimize chemical residues while preserving sensory attributes. Washes with sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl, 200 ppm) plus chlorine dioxide (ClO2, 3–15 ppm) reduced Listeria (≈5.5 log CFU/g) and Salmonella/STEC (≈3.0/2.6 log), with freezing doubling the effect (≈5.0 log) [145]. Sequential protocols using chlorine, lactic acid, ClO2, and ozone followed by freezing at −17 °C achieved 6.6–7.2 log reductions against Listeria and Salmonella [146]. Peracetic acid (PAA) caused ≈2.2 log reductions in wild berries prior to freezing [147], and gaseous ClO2 (≈57.46 mg/L for 10 h) reduced ≈1.5 log in 50 kg batches [148].

Among physical technologies, pulsed light (PL) inactivated microorganisms without leaving residues [122]; pulsed electric fields (PEF/MPEF) preserved vitamins and anthocyanins while reducing microbial growth for up to 30 days [123]. Manothermosonication achieved a 5.85 log reduction in E. coli O157:H7 while maintaining 97.5% of anthocyanins and only 10.9% residual PPO activity [126], whereas high-pressure processing (HPP, 200–600 MPa) preserved firmness and reduced cell collapse for 28 days at 3 °C [119]. In puree matrices, HHP ≥ 550 MPa inactivated > 4 log human norovirus without affecting color or sensory properties [118]. Cold atmospheric plasma (CAPP, 5–10 min) inhibited bacteria with minimal impact on °Brix, acidity, color, or anthocyanins [127]. At harvest level, sanitation reduced aerobic plate count (APC) by 1.2 log and yeast/mold counts (YMC) by 0.5 log compared to mechanical harvest [149], underscoring the importance of on-field biosecurity.

In antimicrobial coatings, eugenol nanoemulsions (EPS from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum) reduced Salmonella/E. coli by up to 3 log [150], and almond gum + chitosan coatings extended shelf life by ≈20 days while acting against S. aureus and P. aeruginosa [151]. Although cold plasma (CP) reduced APC by 0.8–1.6 log (up to 2.0 log after 7 days), exposures beyond 60–90 s compromised firmness and anthocyanin content, confirming the need for cultivar-specific dose–response curves [128]. The integration of rapid diagnostic tools (near-infrared, hyperspectral, and thermal imaging) enables real-time monitoring of hidden damage, bruising, and overall quality through support vector machine (SVM) models [152,153].

(iii) Pigment stabilization: copigmentation, encapsulation, and protein/biopolymer matrices: The main anthocyanins responsible for color and part of the bioactivity in blueberries are stabilized through physicochemical routes and matrix-engineering strategies. Copigmentation with phenolic acids (caffeic, ferulic, and tannic acids) and CaCl2 increased anthocyanin content (3.38 vs. 2.79 mg/g) and reduced polymeric color (15.5–17.4%) [154]. In HHP-treated juices, gallic acid (2 g/L) reduced anthocyanin loss from 62.27% to 13.42% (20 days at 4 °C) and lowered polyphenol oxidase (PPO) activity [155]. Under 100–500 MPa, the λmax and color of anthocyanins (Mv 3 O gal, Mv 3 O ara) remained stable, with minor chromatic variations and improved copigmentation of caffeic acid (CA) with Mv 3 O gal and gallic acid (GA) with Mv 3 O ara [156].

In encapsulation, alginate–pectin hydrogels increased encapsulation efficiency (EEₘ), extended half-life (t½ from 58 to 630 h), and reduced photodegradation [157]. Polyphenol–protein complexes produced by spray drying (soy protein isolate) retained high levels of total phenolic content (TPC) and DPPH activity [158]. AEPU microcapsules embedded in starch films extended shelf life (>7 days) and were ≈95% biodegradable after 8 days [159]. Chitosan–κ-carrageenan nanocomplexes retained 94.4% of anthocyanins (pH 6, 25 °C) [160], while thermosonication and controlled acidification (pH 2.1) preserved anthocyanins during pasteurization and storage [144,161]. At the network scale, cyanidin 3-glucoside degradation under ultrasound followed first-order kinetics, showing higher stability in 20% ethanol [162]. In the presence of catechol and PPO, browning followed first-order kinetics dependent on concentration [163].

These pathways converge into design frameworks combining (a) pH adjustment and phenolic cofactors, (b) sequential modulation of pressure/temperature/light, and (c) biopolymeric or protein-based carriers with antioxidant and barrier capacity. In pigment stabilization, the combination of physicochemical adjustments and biopolymeric matrices has shown outstanding results in anthocyanin retention and color preservation during storage. Table 3 summarizes the main copigmentation, encapsulation, and pH control strategies applied to blueberry matrices, highlighting their effectiveness and operational conditions.

Table 3.

Pigment stabilization (copigmentation, pH, matrices).

From an applied and comparative perspective, Table 3 indicates that the most effective strategies for maximizing anthocyanin retention and long-term color stability are those that combine structural protection with enzymatic inhibition. In particular, HHP combined with gallic acid and chitosan–κ-carrageenan nanocomplexes show the highest anthocyanin preservation (>90%) while simultaneously limiting polyphenol oxidase activity, making them especially suitable for high-value beverages and semi-liquid matrices. For applications where photostability and extended shelf life are the primary objectives, alginate–pectin hydrogels provide the most robust protection by markedly increasing anthocyanin half-life. In contrast, phenolic copigmentation with CaCl2 and thermosonication offer flexible, process-compatible solutions for enhancing color intensity and antioxidant retention when full encapsulation is not technically or economically feasible. Overall, Table 3 highlights that optimal pigment stabilization depends on aligning the physicochemical strategy with the target matrix, processing intensity, and desired storage performance rather than relying on a single universal approach.

(iv) Valorization of by-products into functional ingredients and active packaging: The residual fraction (pomace, peel, seed, and process water) represents a key resource for antioxidant ingredients, natural colorants, and functional biomaterials. Blueberry Waste Material (BWM) processed through aqueous extraction and spray drying yielded powders with total phenolic content (TPC) of 25–30 mg GAE/g and total anthocyanin content (TAC) of 17–20 mg CyGE/g; alginate exhibited the highest encapsulation efficiency and prebiotic effect [164]. Pomace dried at 60–70 °C retained 66–75% of anthocyanins and >30% of fiber after 20 weeks [165], while extrusion at 180 °C/150 rpm increased procyanidin monomers (+84%) and reduced polymers (−40%) [166]. Peel/seed extracts (≈58.18 mg GAE/g) enabled edible films with ≈76% antioxidant capacity [167], and gelatin obtained from residues processed with microwaves shortened processing time by 30–50% while increasing DPPH/FRAP activity [168].

In “sensorial” packaging, HKGB films (hydroxypropyl methylcellulose, κ-carrageenan, gelatin) incorporating anthocyanins exhibited high antioxidant capacity (DPPH 82.92%; ABTS 86.44%), mechanical strength ≈ 5.85 MPa, and ammonia sensitivity ≈ 32.79%, compatible with mobile readout systems [169]. Chitosan–chestnut gum (CS:CH) coatings enriched with grape seed extract retained 84.8% antioxidant capacity and reduced decay, whereas formulations with lemon essential oil were less effective [170]. Meanwhile, natural deep eutectic solvents (NADES) combined with microwave-assisted (MAE) and ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) achieved 21–26 mg/g anthocyanins with antiproliferative activity against HeLa and HaCaT cells [171].

These strategies establish circular loops in which residues, ingredients, and packaging improvements contribute to enhanced product stability and safety. Within the context of functional packaging and coatings, biopolymeric and protein-based solutions have been developed with antioxidant, antimicrobial, and indicator properties designed to extend fruit shelf life and integrate freshness monitoring within the cold chain. Table 4 highlights the diversification of emerging strategies in active and intelligent packaging: antimicrobial coatings based on chitosan and natural gums, sensorial films with anthocyanins as ammonia indicators, biodegradable microcapsules with antioxidant activity, and protein matrices that enhance phenolic compound stability. These innovations strengthen the link between quality preservation and smart packaging within the circular-economy paradigm.

Table 4.

Coatings, packaging, and packaging intelligence.

From an applied perspective, Table 4 indicates that the most mature and immediately transferable strategies for extending shelf life of fresh blueberries are antimicrobial biopolymer coatings based on chitosan and natural gums, which consistently reduce decay and weight loss while remaining compatible with existing cold-chain logistics. For applications requiring real-time freshness monitoring, anthocyanin-based sensorial films offer the greatest potential due to their high antioxidant activity and reliable response to ammonia as a spoilage indicator. In contrast, active microcapsules and protein–polyphenol carriers are especially promising for processed products and functional ingredients, where controlled release, antioxidant stability, and biodegradability are prioritized over immediate antimicrobial action. Overall, Table 4 highlights that successful by-product valorization and active packaging design depend on matching material functionality with the intended product form and supply-chain requirements rather than adopting a single universal packaging solution.

Non-thermal technologies (HHP/HPP, PL, PEF/MPEF, thermosonication), combined with a strict cold chain and smart coatings/packaging, are emerging as the most robust levers to extend blueberry shelf life while preserving nutraceutical value. Anthocyanin stabilization via copigmentation/encapsulation and the use of biopolymeric/protein matrices help maintain color and functionality in juices, gels, powders, and wines. By-product valorization enables active ingredients and packaging within a circular framework. To bridge the lab–industry gap, real-environment kinetics, methodological standards, and comprehensive scale-up assessments (energy, cost, environmental footprint) are required by cultivar and processing route [120,131,164,169].

4.9. Modeling, Computer Vision, and Precision Agriculture in Blueberry Cultivation

The recent literature reveals a strong convergence between computer vision, spectroscopy, and precision agriculture as foundational pillars of intelligent modeling applied to blueberry (Vaccinium spp.). These tools address bottlenecks across the production cycle from maturity detection and yield estimation to plant health diagnostics, postharvest management, and input optimization consolidating a predictive, data-driven paradigm. For yield prediction, object-detection algorithms have proven highly effective. The YOLOv8 (You Only Look Once, version 8) model, used to differentiate between ripe and unripe berries, achieved a mean Average Precision at Intersection over Union (mAP50) of 0.708. When integrated with 42 agronomic regressors, a gradient boosting model obtained a coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.80, whereas excluding genotype reduced the fit to R2 = 0.47, confirming the genetic relevance in productivity [172]. Under low-light conditions, the YOLOv11-BSD model optimized with bidirectional attention and multiscale fusion improved accuracy to 89% (+5.4 pp) and mAP@[0.50:0.95] to 80.8% (+5.7 pp) [173]. In mechanical harvesting, YOLOv5 enhanced with saturation in CIE Lu′v′ color space increased precision (+3%), recall (+2%), and mAP (+2.6%) [174], while YOLOv3-spp trained with 4220 images classified three maturity stages (green, red, and blue) with a recall of 91% and inference times of 28.3 s [175]. Aerially, Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) equipped with RGB cameras achieved R2 = 0.89 for yield prediction, with flights at 30 m being more efficient than at 5 or 15 m (RMSE = 542.01; MAE = 379.94) [176].

Non-destructive evaluation of internal quality using spectroscopy and deep learning has enabled accurate prediction of key physiological variables. In the visible–NIR range (400–1000 nm), Partial Least Squares (PLS) and interval PLS (iPLS) models predicted Soluble Solids Content (SSC) and Firmness Index (FI) with prediction coefficients (Rp) of 0.90 and 0.78, respectively [177]. In the NIR range (900–1700 nm), a pushbroom system applied to ‘Bluecrop’ achieved calibration and validation coefficients (RC = 0.911; RV = 0.871 for firmness; RC = 0.891; RV = 0.774 for sugars) [178]. Using FT-NIR and FT-IR (Fourier Transform Near/Mid Infrared) in ‘Brigitta’ and ‘Duke’, minimum prediction errors were obtained (RMSEP = 0.36% for SSC and 0.18 mg·g−1 for total phenolics) [179]. Portable Vis–NIR spectrophotometers (450–980 nm) achieved correlations of r = 0.80–0.92 for SSC, firmness, and functional compounds [180]. In the terahertz (THz) range (0.5–10 THz), a Gaussian-kernel Support Vector Machine (SVM) classified four ripening stages with 84.3% accuracy, confirming the submillimeter spectrum’s capacity to characterize epidermal and turgor properties [181].

In postharvest, the combination of computer vision and spectroscopy showed high sensitivity for quantifying mechanical damage. A web application based on MobileNet SSD/UNet detected berries with average precision (AP) of 0.977 and segmented bruises with Intersection over Union (IoU) of 0.773, processing 50 berries per image in under 30 s [182]. In NIR hyperspectral spectra (950–1650 nm), band ratios (R1112.6/1470.9) and the MT-COA algorithm identified mechanical damage 30 min post-impact (IoU = 70.1%) [182], correlating R2 = 0.78–0.83 with human evaluation [183]. Pulsed thermography achieved accuracies of 88% and 79% depending on cultivar (‘Farthing’, ‘Meadowlark’) [184], enabling the detection of thermal and conductivity alterations as early physiological indicators of impact damage.

In plant health, deep learning models span from leaf analysis to remote sensing. Geometric algorithms segmented herbivory damage with high robustness [185]. Through transfer learning, FCDCNN networks achieved 98% accuracy and reduced computation time by 25% [186], while EfficientNetB3 and ResNet (Residual Network) maintained 98.1% accuracy in multi-species classification, including blueberry [187,188]. Lightweight models (~2.6 M parameters) classified plants with 98.1% accuracy [189] and detected infestations with 84% accuracy [190]. For flower detection, a compact YOLOv10n (CSP_MSEE + HS-FPN + SFF + LSDECD) reached recall = 84.0% and mAP50 = 89.5% with only 1.3 M parameters, suitable for embedded systems and UAVs [191]. For internal infections, NIR spectrophotometers (650–1700 nm) exceeded 80% accuracy, while hyperspectral models (400–1000 nm) combined with Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLSDA) identified 100% of healthy and 99% of diseased plants [192].