Abstract

This study critically examines the technological feasibility, regulatory challenges, and societal acceptance of Pilotless Passenger Aircraft (PPAs) in commercial aviation. A mixed-methods design integrated quantitative passenger surveys (n = 312) and qualitative pilot interviews (n = 15), analyzed using SPSS and NVivo to capture both statistical and thematic perspectives. Results show moderate public awareness (58%) but limited willingness to fly (23%), driven by safety (72%), cybersecurity (64%), and human judgement (60%) concerns. Among pilots, 93% agreed automation improves safety, yet 80% opposed removing human pilots entirely, underscoring reliance on human adaptability in emergencies. Both groups identified regulatory assurance, demonstrable reliability, and human oversight as prerequisites for acceptance. Technologically, this paper synthesizes advances in AI-driven flight management, multi-sensor navigation, and high-integrity control systems, including Airbus’s ATTOL and NASA’s ICAROUS, demonstrating that pilotless flight is technically viable but has yet to achieve the airline-grade reliability target of 10−9 failures per flight hour. Regulatory analysis of FAA, EASA, and ICAO frameworks reveals maturing but fragmented approaches to certifying learning-enabled systems. Ethical and economic evaluations indicate unresolved accountability, job displacement, and liability issues, with potential 10–15% operational cost savings offset by certification, cybersecurity, and infrastructure expenditures. Integrated findings confirm that PPAs represent a socio-technical challenge rather than a purely engineering problem. This study recommends a phased implementation roadmap: (1) initial deployment in cargo and low-risk missions to accumulate safety data; (2) hybrid human–AI flight models combining automation with continuous human supervision; and (3) harmonized international certification standards enabling eventual passenger operations. Policy implications emphasize explainable-AI integration, workforce reskilling, and transparent public engagement to bridge the trust gap. This study concludes that pilotless aviation will not eliminate the human element but redefine it, achieving autonomy through partnership between human judgement and machine precision to sustain aviation’s uncompromising safety culture.

1. Introduction

The operational and technological architecture of commercial aviation has been transformed by progressive automation over the past half-century. Modern transport aircraft routinely rely on automated subsystems for navigation, flight management and autopilot-managed flight segments; these systems have progressively shifted crew roles from active manual control to supervisory monitoring and system management. The result is a new technical plausibility for pilotless passenger aircraft (PPAs), platforms in which the traditional on-board flight crew is either wholly absent or reduced to remote/ground oversight. However, technical feasibility does not equate to operational or societal acceptability: the transition to PPAs requires rigorous assurance of safety, certification of complex AI/automation systems, clarity on liability, and broad public trust. These intersecting constraints position PPAs not merely as an engineering challenge but as a sociotechnical problem that spans engineering, human factors, regulation and ethics [1,2,3]. Aviation’s historical record strongly privileges safety as the primary design and regulatory objective; commercial aviation today is widely regarded as one of the safest transport modes, supported by institutionalized safety management systems and continuous operational learning [1]. Nevertheless, contemporary developments in machine learning (ML), computer vision and high-integrity flight control architectures have demonstrably shifted the frontier of what autonomous airborne systems can accomplish. In this study, AI-driven flight management is defined as an adaptive perception–planning–control architecture capable of managing taxi, take-off, climb, cruise, descent, approach, and landing, with potential responsibility for emergency decision-making escalation during non-nominal events. Industry demonstrations such as Airbus’s Autonomous Taxi, Take-Off and Landing (ATTOL) program have achieved vision-based automated take-off and landing trials, illustrating that tasks previously assumed to require continuous human judgement can be automated under controlled conditions [2]. Similarly, research programs focused on high-assurance architectures for unmanned systems (for example, ICAROUS) have produced algorithmic suites intended to enable reliable, safety-centric autonomous operations in complex airspace [3]. These demonstrations show technical progress but also highlight that incremental validation and system assurance remain essential prerequisites for any wider operational deployment.

Major regulatory authorities and safety organizations are actively responding to the challenge of integrating AI into aviation. The U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and UK/EU regulators have articulated roadmaps and guidance for AI safety assurance, emphasizing incremental approaches, collaboration with industry, and reuse of existing certification paradigms where possible [4,5]. The FAA’s recent roadmap for AI safety assurance recommends a principled, evidence-based safety case for any learning-enabled system and underlines that AI should be treated as an engineering artifact subject to rigorous verification, validation and configuration management [4]. At the same time, European regulatory activity, including the development of “U-space” rules to manage higher-density unmanned traffic, signals that institutional frameworks for unmanned operations are maturing even as passenger-carrying autonomy remains in an earlier phase of regulatory consideration [6]. Technical progress relevant to PPAs spans several interdependent domains: (a) perception and sensor fusion (multi-sensor navigation and computer vision), (b) high-integrity flight control and fault-tolerant architectures, (c) robust autonomy and decision logic (including collision avoidance and contingency management), and (d) resilient communications and cybersecurity. Advances in onboard computer and algorithmic safety (including formally verified or assurance-oriented components) make complex autonomy more realistic than a decade ago; for example, integrated architectures such as ICAROUS bundle safety-centric path planning, detect-and-avoid, and robust navigation for operations in controlled airspace [3]. Research and industrial prototypes have also demonstrated remote/autonomous control of transport-category aircraft in cargo contexts, and startups plus established manufacturers are investing in trials that expand operational envelopes for autonomy (e.g., remotely piloted cargo flights and vision-based ATTOL experiments) [2,7]. These developments reduce the technical gap, but they do not eliminate the need for exhaustive verification across the full operational design domain (ODD) that PPAs would occupy.

The aviation literature emphasizes that automation changes the nature, rather than the level, of human contribution to safety. Human factors research documents automation bias, loss of situational awareness, and skill degradation as potential side effects of higher automation levels; consequently, safe integration often requires redesigning crew roles, interfaces and training [8,9]. Pilots and safety practitioners therefore frame autonomy as a system property that must be supported by layered redundancies, transparent decision logic, and human–machine interaction designs that preserve operator comprehension during off-nominal events. In short, the “last-resort” decision-making required in rare but high-consequence emergencies remains an open question for fully autonomous passenger operations. Empirical studies on public attitudes also show that perceived risk, a psychological construct influenced by dread, familiarity, and perceived control, strongly affects willingness to accept autonomous transport modes; lay risk perception often diverges from technical risk assessments, complicating adoption pathways [10,11]. Public acceptance is arguably the single largest barrier to widespread PPA adoption. Several empirical investigations indicate that while many passengers recognize potential benefits (cost reductions, efficiency gains), a sizeable proportion are reluctant to fly without an on-board pilot, citing safety and trust concerns [11]. The structure of passenger attitudes is complex and shaped by framing, prior exposure to autonomous systems, cultural factors, and incident narratives; acceptance is more likely to grow through staged exposure (e.g., successful cargo operations, demonstrable reliability records) than via immediate introduction of full autonomy for passengers [11,12]. Lessons from autonomy in other transportation domains (e.g., automated driving) show that transparent communication, incremental service rollouts, and visible safety cases are central to shifting public opinion over time [13].

Regulatory authorities face multiple concurrent tasks: (i) defining certification methodology for learning-enabled and data-driven systems, (ii) establishing operational rules for mixed-traffic airspace that includes manned and unmanned aircraft, and (iii) clarifying liability and accountability in the event of failure. The FAA and other regulators explicitly prioritize development of AI safety assurance processes, stressing reuse where possible but acknowledging that new normative artifacts will be needed for continuous-learning systems or those that adapt in-service [4]. European U-space regulation provides a governance model for dense unmanned traffic corridors, but the certification of passenger-carrying autonomous systems will require bespoke requirements for levels of redundancy, verification against abnormal scenarios, and human factors integration [6]. Ethically, replacing human pilots raises questions about distributive impacts (job displacement), moral responsibility in algorithmic decisions, and the societal acceptability of delegating life-critical choices to machines; these are matters that sit at the interface of technology, law and public policy and demand cross-disciplinary solutions [14,15]. From an economic standpoint, airlines could theoretically realize operating cost reductions through lower crew costs, optimized fuel consumption enabled by advanced flight management systems, and increased utilization enabled by reduced crew-rest constraints. Yet these potential gains are moderated by certification costs, necessary investments in cybersecurity, infrastructure changes (airspace management and ground control facilities) and the uncertain impact of passenger demand for pilotless services [16]. Moreover, as studies show, public reluctance can blunt the anticipated market benefits unless adoption follows a measured pathway that addresses trust and regulatory acceptance [11]. The operational trade-offs therefore couple direct cost calculus with strategic considerations about brand, trust and regulatory timing.

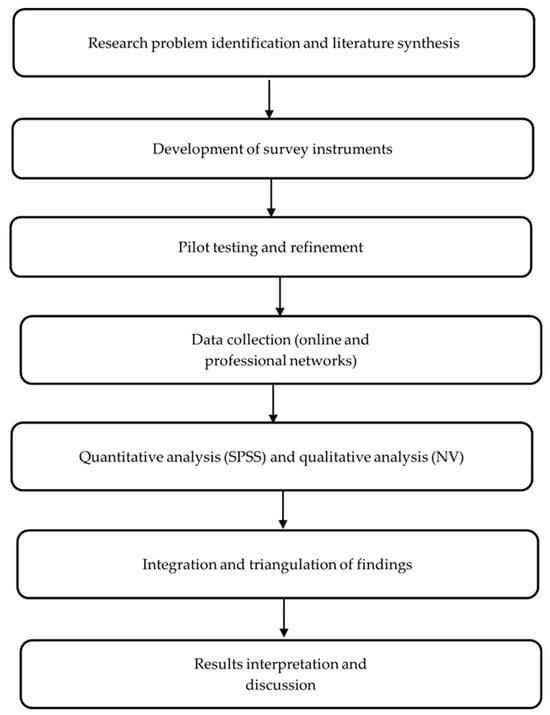

A recurring theme across industry roadmaps, regulatory guidance and empirical studies is the endorsement of an incremental adoption pathway. Practical paths begin with lower-risk operational domains, e.g., cargo flights, military applications or restricted regional services, where the absence of passengers or different mission profiles lowers societal risk and allows technology maturation under operational conditions [7,17]. From these foundations, the gradual introduction of reduced-crew operations (with robust remote oversight and enhanced human–machine teaming) creates opportunities for trust-building, standards development, and workforce transition. Hybrid models in which AI acts as an active co-pilot rather than a full replacement may reduce perceived risk while delivering many of the efficiency and safety benefits associated with automation. Such transitional architecture also permits regulators to evolve certification frameworks in parallel with operational experience [2,4]. Despite the rapid technological progress and regulatory attention, several research gaps persist. First, comparative analyses that synthesize technical feasibility, public acceptance data and regulatory readiness into an operational roadmap for PPAs are limited in number. Second, while industry pilots and prototypes demonstrate potential, there is a shortage of large-sample empirical studies that couple passenger attitudes with pilot perspectives, workforce impacts and cost–benefit modelling. Third, normative and legal frameworks for assigning liability in AI-mediated flight decisions remain underdeveloped. This paper aims to address these gaps by (i) synthesizing the technical, regulatory and social literatures on pilotless passenger flight; (ii) presenting empirically derived stakeholder perspectives (passengers and pilots); and (iii) proposing a pragmatic, phased adoption pathway that balances innovation with safety, ethics and social acceptability (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Methodological Workflow Diagram.

2. Research Design, Sampling Strategy, and Data Collection Procedures

2.1. Research Design and Sampling Strategy

This study adopted a mixed-methods design, integrating both quantitative and qualitative approaches to comprehensively explore the feasibility and acceptability of pilotless passenger aircraft (PPAs). The rationale for this design lies in the need to examine not only numerical trends in passenger and pilot attitudes but also the underlying motivations, perceptions, and contextual factors influencing those attitudes. Quantitative methods capture measurable variables (e.g., willingness to fly, safety perceptions), while qualitative insights reveal the reasons behind these preferences. Mixed-methods research enhances the validity and reliability of findings through triangulation, the use of multiple data sources to corroborate results [18,19]. Previous aviation research on public perception, risk communication, and technology acceptance supports this approach as particularly effective for examining complex socio-technical systems [7,20]. Thus, the study design integrated two distinct but complementary datasets: (i) a structured questionnaire distributed to passengers and (ii) an open- and closed-question survey administered to professional pilots.

Two primary participant groups were targeted: passengers representing the general travelling public, and commercial pilots representing aviation professionals. A total of 312 passenger responses were collected, representing a broad demographic cross-section. Participants were primarily between 18 and 34 years old (93%), reflecting younger generations more likely to adopt technological innovations. This concentration of younger respondents introduces a sampling bias and does not represent the full demographic distribution of commercial air travelers; therefore, generalizability is limited. Gender distribution was approximately 66% male and 33% female, and most respondents (85%) reported flying between one and five times annually. The pilot survey comprised 15 professional pilots with diverse experience ranging from 0 to 5 years (33%) to 21+ years (26%), drawn from both commercial and private aviation sectors. Given the small number of pilot respondents (n = 15), these results are treated as expert opinion rather than statistically representative findings. The study did not collect detailed information on pilot flight hours, aircraft type experience, or specific operational categories (e.g., long-haul, regional). This omission is recognized as a limitation affecting the depth of interpretation. This sample allowed for a balanced view of early-career and veteran professionals, enhancing insight into occupational perspectives and risk perceptions. Sampling employed a purposive, convenient approach, appropriate for exploratory studies in emerging domains [21]. Passenger surveys were distributed online via Microsoft Forms and through social media platforms, while pilot surveys were conducted through professional aviation networks. The study prioritized diversity of perspectives over representativeness, consistent with early-phase exploratory research.

2.2. Data Collection Procedures

Two distinct survey instruments were used; each tailored to its respective group. The passenger instrument included closed-ended and Likert-scale questions capturing demographic information, flight frequency, purpose of travel, and attitudes toward PPAs. Key dimensions measured included perceived safety, trust in automation, cost–benefit trade-offs, and willingness to fly in an autonomous aircraft. Likert items employed a five-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), enabling ordinal analysis. Survey questions were adapted from validated instruments used in studies of technology adoption in aviation and autonomous vehicles [11,13]. Microsoft Forms was selected for its accessibility, scalability, and compatibility with quantitative export to IBM SPSS Statistics Version 29.0.1.0 (171) for analysis. The pilot instrument employed a semi-structured format, combining categorical and open-ended questions. Themes addressed included operational safety, automation benefits and limitations, perceptions of PPAs, and anticipated impacts on career sustainability. These open-ended questions were designed to elicit richer professional perspectives on AI-enabled flight management, emergency handling expectations, and regulatory confidence. The open responses provided qualitative depth, which was subsequently analyzed using thematic analysis. Both questionnaires underwent pilot testing (n = 10) to assess clarity, question flow, and completion time. Feedback from test respondents resulted in minor wording adjustments to reduce ambiguity and cognitive load, following standard survey refinement practices [22].

Data analysis followed distinct but complementary procedures for quantitative and qualitative components. Quantitative passenger data was exported from Microsoft Forms to SPSS for statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages, and cross-tabulations) summarized demographic distributions and attitude measures. Data visualization was produced using bar and pie charts for clarity. Inferential statistical analysis was intentionally limited due to the exploratory nature of the study and demographic imbalance. The use of SPSS ensured precision and reproducibility of results and allowed transparent documentation of analytical processes. Qualitative responses from pilot surveys were coded and analyzed thematically using NVivo. Following Braun and Clarke’s (2006) framework [23], a six-phase approach was employed: (1) familiarization with data, (2) generation of initial codes, (3) theme searching, (4) theme review, (5) theme definition, and (6) report production. Codes were data-driven but guided by the study’s research objectives (safety, trust, operational feasibility, and ethical concerns). Coding was conducted by a single coder. No inter-coder reliability statistics (e.g., Cohen’s kappa) were generated. The absence of a second coder is acknowledged as a methodological limitation. No numeric code counts are reported, as these were not part of the original dataset.

Ethical integrity was central to the research design. The study complied with Kingston University’s Research Ethics Framework and broader principles of the British Educational Research Association (BERA) [24]. Participation was voluntary, with informed consent obtained prior to data collection. Respondents were assured of anonymity and confidentiality, and no personally identifying data was stored. All data handling complied with the UK Data Protection Act (2018) and General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) [25,26]. Participants were permitted to withdraw responses at any stage prior to data submission. Given the minimal risk associated with anonymous survey participation, ethical approval was granted under low-risk research classification.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Passenger Questionnaire Results

A total of 312 passenger questionnaires were completed. Respondents were predominantly young adults, with 93% aged 18–34 years, 6% aged 35–54 years, and fewer than 1% over 55, as shown in Table 1. The gender split was 66% male and 33% female, while 1% identified as other or preferred not to say. Flight frequency data showed that most participants flew one to five times per year (85%), with 10% travelling six to ten times and 5% more than ten times annually. These demographic findings mirror prior studies showing that early-career, digitally literate travelers dominate public-acceptance surveys of emerging aviation technologies [10,11]. The age concentration in the 18–34 band indicates a sampling bias relative to global air-travel demographics; the findings therefore reflect a technology-proximal cohort rather than a fully representative passenger population.

Table 1.

Passenger demographics.

With a track record of safety, the data reveal a predominantly cautious but not dismissive public stance toward pilotless passenger aircraft. When asked if passengers would consider flying pilotless (see Table 2) if there was a track record of safety better than human-operated aircraft, of the total respondents, (approximately 47%) indicated they would be “likely” to fly on such an aircraft, while (31%) were “highly likely” to do so. Conversely, respondents (15%) expressed that they were “unlikely,” with only (4%) “highly unlikely” and another (4%) “indifferent.” These proportions suggest a tentative but emerging openness to autonomous aviation, indicating that public attitudes may be more receptive than commonly assumed in earlier studies that predicted overwhelming resistance. The relatively small share of respondents who were strongly opposed highlights a potential shift in perception, possibly reflecting increased familiarity with automation technologies and their demonstrated safety in other transport domains.

Table 2.

Passengers’ willingness to fly in a pilotless aircraft if proven track record of safety compared to human-controlled aircraft.

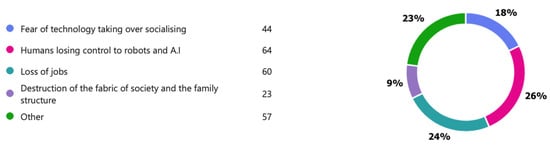

The results presented in Figure 2 highlight persistent societal anxieties regarding technological encroachment within aviation. Among the respondents, (26%) expressed concern about humans losing control to robots and AI, while (24%) feared job losses arising from automation. A further (18%) cited apprehension that increasing technological mediation could erode social interaction, and (9%) associated such advances with a perceived breakdown of societal and familial cohesion. Additionally, respondents (23%) identified other concerns, including ethical and psychological ramifications of autonomous systems. Collectively, these findings reveal that attitudes toward pilotless air travel are not shaped solely by perceptions of technical safety but also by deeper socio-cultural and existential factors.

Figure 2.

Respondents’ concerns regarding technological advancement and its perceived impact on society and aviation.

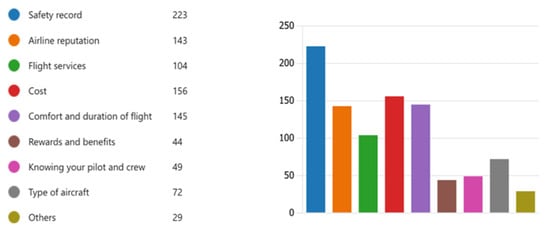

When participants were asked which factor would most influence acceptance, the leading responses were proven safety record (223 responses), cost (156 responses), comfort and duration of flight (145 responses) and airline reputation (143 responses) as indicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Factors influencing acceptance of pilotless aircraft.

These findings suggest that regulatory transparency and operational demonstration are prerequisites to social license for PPAs [4]. Overall, passengers demonstrated cautious curiosity but significant apprehension toward fully autonomous commercial flights. Quantitative indicators show that trust and perceived control remain decisive in shaping acceptance, confirming patterns observed in earlier automation studies [20]. The high proportion of respondents supporting a human-supervised model provides empirical justification for hybrid adoption strategies discussed later (Section 5).

3.2. Pilot Survey Results

Fifteen professional pilots participated (see Table 3). Experience levels ranged from early-career to senior captains: 0–5 years (33%), 6–10 years (27%), 11–20 years (14%), and 21+ years (26%). Sectoral representation included commercial airlines (53%), private/business (33%), and military (14%).

Table 3.

Pilot demographic characteristics.

Pilots generally expressed skepticism toward fully autonomous passenger operations. 93% agreed that automation has improved aviation safety, yet 80% opposed removing pilots from the cockpit entirely. Only one respondent (7%) believed PPAs could match human decision-making in emergencies (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Pilot perceptions of automation and PPAs.

Thematic analysis of open responses revealed three dominant categories of concern: system reliability, ethical accountability, and employment security. One respondent wrote, “Automation reduces workload, but total removal of the pilot removes the conscience of the flight.” Another noted that redundancy and human adaptability were essential “fail-safes” not yet reproducible by AI.

When asked what would make them accept pilotless operations, pilots ranked the following as essential (see Table 5):

Table 5.

Primary factors influencing pilot acceptance of PPAs.

- Demonstrated fail-safe redundancy (80%);

- Global regulatory approval (67%);

- Transparent safety data from operational trials (60%).

Interestingly, while most participants resisted full automation, several acknowledged that partial autonomy could reduce fatigue and enhance safety through improved monitoring. This nuanced position indicates openness to hybrid human–machine systems, consistent with emerging industry perspectives [27]. Approximately 70% of pilots perceived PPAs as a long-term threat to pilot employment. However, 40% believed that new roles, such as remote flight supervision, AI system validation, or data safety auditing, would emerge. This transition echoes the wider aviation workforce transformation predicted by regulatory bodies and trade associations [20,28]. Qualitative feedback underscored a desire for reskilling opportunities rather than opposition to technology per se. The data suggest that acceptance among professionals may increase if automation is framed as augmenting rather than replacing human expertise.

3.3. Integrated Findings

A comparative synthesis of passenger and pilot responses reveals both convergence and divergence in attitudes toward pilotless aviation. Both groups identified safety assurance, system reliability, and trust in automation as decisive acceptance criteria. However, passengers expressed greater concern for personal safety and perceived control, while pilots emphasized system integrity and professional identity (see Table 6). Awareness of pilotless passenger aircraft was moderate: 58% of respondents reported having heard of the concept before the survey, primarily through online media or industry news. Despite this, expressed willingness to fly was low; only 23% stated they would “definitely” or “probably” board a pilotless aircraft, whereas 61% were “unlikely” or “very unlikely” to do so.

Table 6.

Unlikely or very unlikely Passenger awareness and willingness to fly in pilotless passenger aircraft (n = 312).

Trust emerged as the dominant determinant of acceptance. When asked to rate their confidence in full automation managing all flight phases, 68% selected “low” or “very low.” Only 12% reported high confidence, even though 42% agreed that automation generally improves flight safety. Concerns focused on technical reliability (73%), cybersecurity (62%), and emergency decision-making (55%).

Across both samples, respondents supported incremental adoption, beginning with cargo operations or limited-crew flights—an approach consistent with regulatory guidance for staged certification [5]. This pattern highlights how perceptions of risk and trust intersect to shape acceptance pathways for pilotless aircraft. Analysis of these responses further revealed four interrelated conceptual themes: trust and transparency, human oversight, regulatory assurance, and societal readiness. Participants stressed the need for transparent communication about safety performance, confidence in certified systems, and time for societal adaptation. Collectively, these findings reinforce the view that acceptance of pilotless passenger aircraft depends on demonstrated reliability, institutional legitimacy, and gradual exposure [4,29]. Triangulating quantitative and qualitative evidence confirms this dynamic. Statistical trends illustrate widespread hesitation, while narrative insights reveal emotional drivers such as fear of catastrophic failure and the loss of human control. Overall, while the technical feasibility of pilotless aviation is evident, its social license to operate remains conditionally anchored in continued proof of safety, robust oversight, and transparent certification.

4. Discussion

4.1. Safety and Reliability of Autonomous Systems

Safety remains the principal determinant of social and institutional acceptance of pilotless passenger aircraft (PPAs). In both passenger and pilot samples, the dominant concern centered on the technical reliability of fully automated flight systems. More than two-thirds of passengers expressed low confidence in autonomous control, while 80% of pilots rejected the notion that PPAs could safely operate without human oversight. This summarizes the empirical findings reported in Table 6 and Table 7, where 68% of passengers reported low or very low confidence in fully automated flights and 80% of pilots opposed complete pilot removal. These findings reinforce aviation’s deep-seated “zero-failure” culture, where even minimal uncertainty undermines legitimacy. Recent research confirms that public acceptance of AI-enabled aviation hinges on demonstrable reliability and a clear safety case [7,20]. The FAA’s 2024 AI Safety Assurance Roadmap explicitly recommends a “progressive evidence-based certification pathway” for learning-enabled systems [4], while EASA’s U-space 2024 framework introduces operational tiers that segregate risk categories to protect public confidence [6]. This regulatory alignment suggests that automation will expand only as empirical safety evidence accumulates. From a systems-engineering perspective, achieving parity with human reliability requires ultra-redundant architectures, multiple independent sensor channels, high-assurance flight control logic, and deterministic fail-safe behaviors [3]. The ICAROUS project demonstrated that autonomous detect-and-avoid algorithms can operate at high integrity, but only within predefined operational design domains [10]. In short, technical feasibility exists, yet operational reliability at airline-level safety targets (≈10−9 failures per flight hour) remains unproven [3]. These findings validate an incremental strategy: deploying autonomy first in cargo and low-risk missions where experimental evidence can be generated without endangering passengers. Demonstrated success in such domains will be a prerequisite for broader acceptance of PPAs.

Table 7.

Passenger trust and safety perceptions regarding fully automated flight*.

4.2. Human Factors and Trust in Automation

Both cohorts recognized the efficiency benefits of automation but questioned its capacity to manage the unexpected. As shown in Table 7, 68% of passengers reported low trust in fully autonomous control, echoing literature that identifies trust calibration as pivotal in human automation interaction [11,30]. Over-trust leads to complacency, and under-trust results in underutilization of safe automation. Pilots in this study emphasized the irreplaceable value of human intuition in “edge-of-envelope” scenarios such as weather avoidance and system fault management. Automation bias, loss of situational awareness, and skill decay documented across numerous cockpit studies [8,31] were cited as reasons for retaining human oversight. Thus, the profession views AI as an augmentation rather than a substitution technology.

Trust development is gradual and experiential. Evidence from automated-vehicle studies shows that repeated exposure, transparent feedback, and visible safety redundancies build confidence over time [13]. Applying these principles, early adoption of hybrid flight decks where AI handles routine control under continuous pilot supervision offers the most viable trust-building pathway. Such “human-on-the-loop” configurations preserve accountability while exploiting automation’s consistency. The data therefore converge on a central insight: technological credibility alone cannot guarantee acceptance; perceived control and transparency are equally essential. Incorporating explainable-AI interfaces that articulate decision rationale could substantially increase operator trust, aligning with current research in aviation human–machine teaming [32].

4.3. Ethical, Societal, and Workforce Implications

Automation introduces not only engineering but also ethical and social questions. Qualitative feedback from pilots highlighted anxiety over job displacement and loss of professional identity, while passengers raised concerns about moral accountability in AI-mediated decisions. These align with broader debates on algorithmic responsibility and distributive justice in safety-critical domains [33]. From a workforce perspective, the transition to autonomous aviation is likely to reconfigure rather than eliminate employment. Forecasts by IATA (2024) project a shift towards remote operation, AI system validation, and data assurance roles [28]. Pilots themselves anticipated such re-skilling opportunities: 40% in this study expected new technical supervisory positions to emerge. This supports policies favoring adaptive workforce planning over resistance to automation. Ethically, delegating life-critical control to algorithms challenges traditional accountability models. In manned aviation, responsibility resides with the pilot-in-command; in PPAs, responsibility will diffuse across designers, operators, and regulators. Legal scholars argue for joint accountability frameworks where liability is proportionally distributed according to decision autonomy [33]. Transparent audit trails already mandated under the EU AI Act (2024) offer one mechanism for reconciling this diffusion. Societal readiness also depends on cultural narratives. Public discourse often anthropomorphizes risk, perceiving human error as more forgivable than machine failure [9]. Communicating autonomy as an extension of human capability rather than its replacement may therefore mitigate resistance. The ethical imperative is not merely to achieve safety equivalence but to maintain moral assurance that human welfare remains the ultimate design objective.

4.4. Regulatory and Certification Challenges

The regulatory landscape is simultaneously progressing and fragmenting. Although both FAA and EASA acknowledge autonomy as the next frontier, neither has yet published a complete certification basis for passenger-carrying autonomous aircraft. The FAA’s 2024 Roadmap [4] calls for modular safety cases integrating data-driven evidence, whereas EASA’s AI Concept Paper (2023) proposes a “level-of-autonomy” taxonomy analogous to that used for automated road vehicles [29]. Implementation, however, remains nascent. Surveyed pilots’ insistence on global regulatory certification as a precondition for acceptance underscores how professional endorsement depends on institutional legitimacy. The lack of harmonized international standards currently hinders confidence and investment. ICAO’s Advanced Aviation Mobility Panel (2024) has begun drafting framework provisions for remote-pilot licensing and AI assurance, signaling that multilateral alignment is forthcoming [16,34]. Certification of learning algorithms introduces technical difficulties absent from traditional deterministic systems. Continuous-learning architecture can change behavior post-certification, challenging conventional conformity assessments. Proposed solutions include frozen-weight models for certified versions or periodic re-validation cycles akin to airworthiness checks [35]. Regulatory authorities therefore face a dual mandate: to foster innovation while upholding aviation’s exceptional safety record. A staged certification approach, cargo, limited crew, and then passenger, reflects this balancing act. The empirical preference among both passengers and pilots for incremental adoption validates this emerging regulatory logic.

4.5. Economic and Operational Considerations

Economic arguments for PPAs are persuasive but conditional. Airlines could theoretically reduce operating costs by 10–15% through crew savings and optimization of flight profiles [16]. Respondents, however, remained skeptical that such savings justify safety trade-offs. The data show that perceived cost–benefit ranked below safety assurance as an acceptance driver (Section 4.1). Operationally, PPAs promise efficiency gains in scheduling and turnaround through 24 h utilization without crew-rest constraints. Yet these advantages depend on substantial infrastructure investments: high-bandwidth datalinks, ground-control centers, and robust cybersecurity frameworks. Recent analyses warn that cyber vulnerabilities could negate economic benefits by introducing new risk-mitigation costs [36]. The pilot community’s cautious openness to hybrid models offers a pragmatic route to economic viability. Semi-autonomous operations, single-pilot cockpits with ground-based support, are already under consideration by several manufacturers. Airbus’s ATTOL program demonstrated autonomous taxi, take-off, and landing under pilot supervision, achieving cost and efficiency improvements without eliminating human presence [2]. The findings here align with contemporary cost–benefit and adoption models in aviation, which treat public trust and social acceptance as constraints that can significantly affect economic viability and deployment timelines [37].

4.6. Synthesis and Implications

Integrating quantitative and qualitative insights, this study reveals a consistent tension between technological readiness and societal readiness. The technology to automate flights exists; the social license to deploy it does not yet. Both passengers and pilots predicate acceptance on three interdependent assurances:

- Demonstrated Reliability proven through incremental operational experience in non-passenger contexts.

- Transparent Oversight: regulatory certification and continuous human monitoring.

- Ethical Stewardship: clear accountability and workforce adaptation.

These pillars correspond to the emerging “Hybrid Autonomy Paradigm,” in which AI serves as a cognitive partner rather than a replacement. The model resonates with the human–machine teaming doctrine now guiding both civil and defense aviation research [38]. In empirical terms, these conditions are reflected in the passenger findings, where only 23% would board a pilotless aircraft, 61% were unlikely or very unlikely to do so, and 68% reported low confidence in full automation, as well as pilot findings, where 80% opposed full pilot removal but many supported supervised, hybrid models. This alignment between quantitative patterns and qualitative narratives reinforces the conclusion that phased, human-supervised autonomy is the only socially viable near-term trajectory.

For policymakers, the implications are threefold:

- Regulatory agencies must codify assurance methodologies for adaptive algorithms and foster data-sharing among manufacturers.

- Industry stakeholders should prioritize transparency and public engagement to narrow the trust gap.

- Academic research should focus on longitudinal studies capturing evolving attitudes as demonstrator programs mature.

Collectively, these steps define a roadmap from feasibility to societal normalization. The Discussion therefore converges on a simple but powerful proposition: pilotless aviation will succeed not by removing humans from the system, but by re-defining how humans and machines cooperate within it.

5. Conclusions and Future Work Directions

This study examined the feasibility, challenges, and societal readiness of pilotless passenger aircraft (PPAs) through combined perspectives of public perception and professional expertise. Employing a mixed-methods design—integrating quantitative passenger survey data (n = 312) with qualitative pilot interviews (n = 15)—the research revealed a nuanced picture of conditional acceptance. Passengers expressed cautious curiosity toward pilotless flight. While recognising automation’s potential for efficiency and cost-effectiveness, the majority raised concerns regarding safety, technical reliability, and the loss of human oversight. Trust and perceived control emerged as decisive determinants of willingness to fly. In contrast, pilots largely acknowledged automation’s contribution to safety and workload management but emphasized the irreplaceable role of human judgment during emergencies and the need for redundancy, transparency, and accountability. Both groups supported incremental implementation, beginning with cargo and hybrid crewed operations, rather than abrupt adoption of full autonomy. These findings collectively highlight the central tension between technological capability and societal readiness: although autonomous flight functions are maturing, their deployment remains constrained by passenger trust deficits and pilot scepticism, particularly in emergency-management scenarios. These findings reinforce the emerging consensus that sustainable automation in aviation depends on maintaining public trust and regulatory legitimacy [7,20]. Several methodological limitations should be noted. The relatively small pilot sample (n = 15) constrains statistical generalisability, although qualitative richness offsets this limitation by providing contextual depth. Furthermore, the absence of detailed pilot metrics (e.g., flight hours, aircraft categories flown) limits the ability to contextualise expert judgments. The passenger sample, predominantly younger and UK-based, may not represent broader demographic or cultural variations. The passenger sample, predominantly younger and UK-based, may not represent broader demographic or cultural variations, a concern consistent with prior research on public attitudes to automation [39]. Moreover, the cross-sectional design offers only a temporal snapshot, and attitudes may evolve with technological exposure and regulatory progress [4,40]. Self-reported responses are also susceptible to social desirability bias. Nonetheless, the triangulation of quantitative and qualitative methods enhances the study’s credibility and establishes a robust foundation for future longitudinal research.

Looking forward, several directions for research and practice are recommended. First, phased implementation of AI-enabled aviation should begin with cargo and limited-crew operations, accompanied by transparent disclosure of safety performance metrics to strengthen public confidence, in line with strategic forecasts from aviation regulators [4,40]. Second, hybrid human–AI flight models should be prioritised, allowing AI to function as a supervised copilot—combining computational precision with human adaptability, an approach widely advocated to mitigate safety and thical risks associated with full autonomy [13,41]. Third, global regulatory harmonisation across the FAA, EASA, and ICAO is essential to ensure consistent standards for AI certification, assurance, and data governance [4,40]. Fourth, attention must be given to ethical and workforce transitions, including structured reskilling programmes for pilots and embedding ethical oversight within certification frameworks to uphold accountability in AI decision-making [13,41]. Finally, public engagement and education should be advanced through transparent communication, simulation-based demonstrations, and community outreach to foster understanding and acceptance of autonomous aviation, reflecting evidence that trust in automation is shaped by familiarity, perceived control, and societal context [39]. Future studies should adopt longitudinal designs to capture evolving attitudes as demonstrator projects mature and cross-cultural comparisons to understand how societal context shapes trust in automation [39]. Simulation-based behavioural research could further quantify cognitive and emotional responses to AI-driven decision-making in flight scenarios. Interdisciplinary collaboration—linking aerospace engineering, psychology, and ethics—will be critical to developing comprehensive models of human–machine trust [41].

Conceptual innovations such as Embraer and Bombardier’s AI-controlled, cockpit-free sustainable jet designs [41] and Tatarenko Nikolaevich’s detachable cabin concept [39] exemplify potential future trajectories in PPA development. Integrating operational data from pilotless cargo trials will enhance risk assessment and cost–benefit modelling, thereby bridging existing evidence gaps and informing scalable deployment strategies. The advent of pilotless passenger aircraft represents a transformational milestone in aviation—comparable to the introduction of the jet engine or digital avionics. Yet, this transition will only succeed if technological innovation progresses in step with societal readiness, ethical reflection, and regulatory stewardship. The study affirms that technical feasibility does not equate to social licence. Acceptance of PPAs will depend on a triad of demonstrated reliability, transparent oversight, and meaningful human inclusion within autonomous systems. When these criteria are met, PPAs may achieve not only operational viability but also societal legitimacy, enabling aviation to evolve toward intelligent, cooperative flight systems without compromising its foundational commitment to safety. Ultimately, the future of commercial aviation will not be pilotless—it will be differently piloted: defined by a partnership between human judgment and machine precision that sustains aviation’s central commitment to safety above all.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.E.; methodology, O.E.; validation, O.E. and O.D.; formal analysis, O.E.; investigation, O.E.; resources, O.E.; data curation, O.E. and O.D.; original draft preparation, O.E.; review and editing, O.D.; supervision, O.D.; project administration, O.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kingston University London (protocol code ME7761, date of approval 3 July 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| FMS | Flight Management Systems |

| VTOL | Vertical Take-Off and Landing |

| PPAs | Pilotless Passenger Aircraft |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicles |

| ICAROUS | Integrated Configurable Algorithms for Reliable Operations of Unmanned Systems |

| ATTOL | Autonomous Taxi, Take-Off, and Landing |

| FAA | Federal Aviation Administration |

| ML | Machine learning |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

References

- International Air Transport Association (IATA). 2023 Safety Performance—2024 Press Release. IATA. Available online: https://www.iata.org/en/pressroom/2024-releases/2024-02-28-01/ (accessed on 28 February 2024).

- Airbus. Airbus Concludes ATTOL with Fully Autonomous Flight Tests. Airbus Press Release. Available online: https://www.airbus.com/en/newsroom/press-releases/2020-06-airbus-concludes-attol-with-fully-autonomous-flight-tests (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- Consiglio, M.; Muñoz, C.; Hagen, G.; Narkawicz, A.; Balachandran, S. ICAROUS: Integrated Configurable Algorithms for Reliable Operations of Unmanned Systems. NASA Technical Reports Server; 2016. Available online: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20170001936 (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Roadmap for Artificial Intelligence Safety Assurance. FAA. Available online: https://www.faa.gov/media/82891 (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Reliable Robotics. News: Successful uncrewed Cessna 208B Flight (Remote/Autonomous Cargo). Reliable Robotics. Available online: https://reliable.co/news (accessed on 21 November 2023).

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). Easy Access Rules for U-space (Regulation (EU) 2021/664). EASA. Available online: https://www.easa.europa.eu/en/document-library/easy-access-rules/easy-access-rules-u-space-regulation-eu-2021664 (accessed on 29 May 2024).

- Bennett, R.; Vijaygopal, R. Air passenger attitudes towards pilotless aircraft. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2021, 41, 100656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, S. The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error; Ashgate: Derbyshire, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Slovic, P. The Perception of Risk; Foundational Text on Public Risk Perception and the “Dread/Unknown” Dimensions; Earthscan: Barcelona, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, L.Y.; Yuen, K.F. Public acceptance of autonomous vehicles: Examining the joint influence of perceived vehicle performance and intelligent in-vehicle interaction quality. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2023, 178, 103864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chancey, E.T.; Politowicz, M.S. Public trust and acceptance for concepts of remotely operated urban air mobility transportation. Proc. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. Annu. Meet. 2020, 64, 1044–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vascik, P.D.; Hansman, R.J. Evaluation of key operational constraints affecting on-demand mobility for aviation in the Los Angeles basin: Ground infrastructure, air traffic control and noise. In Proceedings of the 17th AIAA Aviation Technology, Integration, and Operations Conference, Denver, CO, USA, 5–9 June 2017; p. 3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakidis, M.; Happee, R.; de Winter, J.C.F. Public opinion on automated driving: Results of an international questionnaire among 5000 respondents. Transp. Res. F 2015, 32, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, D. Single-pilot airline operations: Designing the aircraft may be the easy part. Aeronaut. J. 2023, 127, 1171–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y. Pilots in the evolving urban air mobility: From manned to unmanned aviation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Warsaw, Poland, 6–9 June 2023; pp. 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Smith, H. Review and prospect of supersonic business jet design. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2017, 90, 12–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reliable Robotics. Reliable Robotics Performs Automated Cargo Deliveries for U.S. Air Force. Business Wire. 23 August 2024. Available online: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20240823677064/en/Reliable-Robotics-Performs-Automated-Cargo-Deliveries-for-U.S.-Air-Force (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.B.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J. Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educ. Res. 2004, 33, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepylo, N.; Straubinger, A.; Laliberte, J. Public perception of advanced aviation technologies: A review and roadmap to acceptance. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2023, 138, 100899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillman, D.A.; Smyth, J.D.; Christian, L.M. Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Educational Research Association (BERA). Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research, 5th ed.; BERA: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- UK Parliament. Data Protection Act 2018; The Stationery Office: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament; Council of the European Union. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 (General Data Protection Regulation); European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Matalonga, S.; White, S.; Hartmann, J.; Riordan, J. A Review of the Legal, Regulatory and Practical Aspects Needed to Unlock Autonomous Beyond Visual Line of Sight Unmanned Aircraft Systems Operations. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2022, 106, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IATA. Future of Aviation Workforce Report 2024; International Air Transport Association: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). Artificial Intelligence Concept Paper v2.0; EASA: Cologne, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.D.; See, K.A. Trust in automation: Designing for appropriate reliance. Hum. Factors 2004, 46, 50–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endsley, M.R. Toward a theory of situation awareness in dynamic systems. Hum. Factors 1995, 37, 32–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokadlı, G.; Dorneich, M.C. Comparison and synthesis of two aerospace case studies to develop human-autonomy teaming characteristics and requirements. Front. Aerosp. Eng. 2023, 1, 1214115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). EASA Artificial Intelligence Roadmap 2.0: A Human-Centric Approach to AI in Aviation; EASA: Cologne, Germany, 2023; Available online: https://www.easa.europa.eu/en/document-library/general-publications/easa-artificial-intelligence-roadmap-20 (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). Advanced Air Mobility Study Group (AAM SG) [Online]; ICAO: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2024. Available online: https://www.icao.int/UA/advanced-air-mobility-study-group-aam-sg (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Perez-Cerrolaza, J.; Abella, J.; Borg, M.; Donzella, C.; Cerquides, J.; Cazorla, F.J.; Englund, C.; Tauber, M.; Nikolakopoulos, G.; Flores, J.L. Artificial intelligence for safety-critical systems in industrial and automotive: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukwandu, E.; Ben-Farah, M.A.; Hindy, H.; Bures, M.; Atkinson, R.; Tachtatzis, C.; Andonovic, I.; Bellekens, X. Cyber-security challenges in aviation industry: A review of current and future trends. Information 2022, 13, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vascik, P.D.; Hansman, R.J.; Dunn, N.S. Analysis of urban air mobility operational constraints. J. Air Transp. 2018, 26, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). Human–Machine Teaming Research Program; DARPA: Arlington, VA, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.darpa.mil/news/2019/trusted-human-machine-partnerships (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Morvan, H. Why a Detachable Cabin Probably Won’t Save Your Life in a Plane Crash. The Conversation. 2022. Available online: https://theconversation.com/why-a-detachable-cabin-probably-wont-save-your-life-in-a-plane-crash-53532 (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Koo, T.T.; Molesworth, B.R.; Dunn, M.J.; Lodewijks, G.; Liao, S. Trust and user acceptance of pilotless passenger aircraft. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2022, 45, 100876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bate, A. AI IN THE SKY Incredible Plan for World’s First AI Passenger Plane with NO PILOT Where Travellers Can Sit in Cockpit & Enjoy the View. The Sun. 2 October 2024. Available online: https://www.thesun.co.uk/tech/30816923/incredible-plan-ai-passenger-plane-pilot-cockpit/ (accessed on 2 January 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.