Abstract

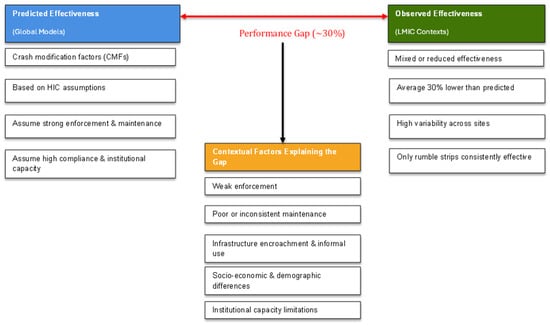

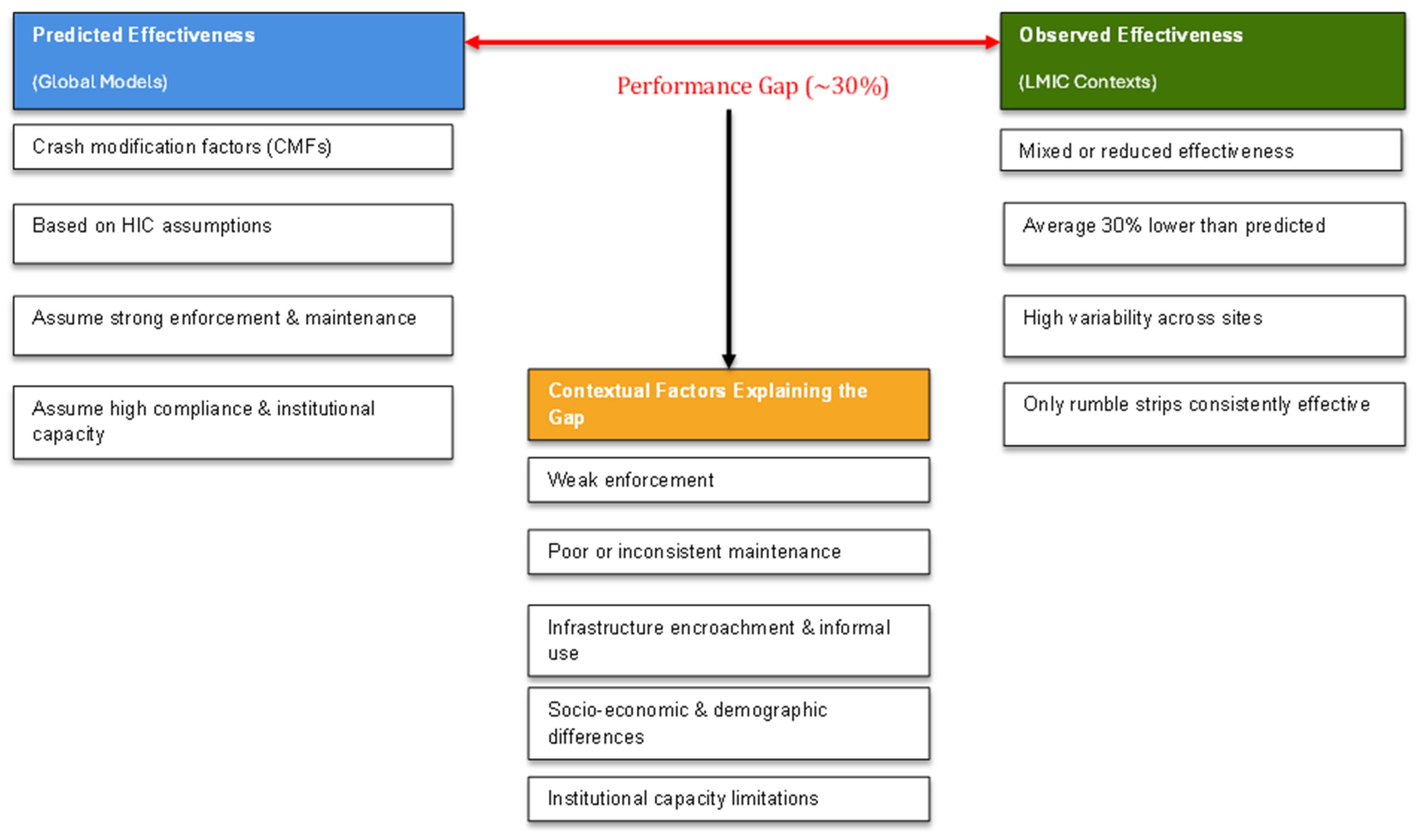

Pedestrian safety remains a pressing challenge in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where global predictive models often misrepresent local realities. This study tests the hypothesis that global predictive models, such as the International Road Assessment Programme (iRAP), overestimate countermeasure effectiveness in LMICs because key contextual factors are omitted. The two-phase research combined a PRISMA-based systematic literature review (SLR) with a quantitative iRAP performance gap analysis of the countermeasures implemented in the candidate studies of the SLR. The review systematically evaluated the effectiveness of pedestrian safety countermeasures, with an emphasis on their application in LMIC contexts. Following PRISMA 2020 guidelines, 14 longitudinal before–after studies were selected from 1911 records and screened with EPPI-Reviewer 4 software. The analysis identified 33 contextual factors shaping countermeasure performance across both high- and low-income settings; of these, 23 were specific to LMICs, and 13 are not accounted for in the iRAP model. The findings show that iRAP systematically overestimates countermeasure effectiveness in LMICs due to weak enforcement, poor maintenance, and informal road use. Transverse rumble strips were the only intervention consistently effective across diverse LMIC settings. A novel performance gap analysis of five LMIC case studies revealed an average discrepancy of 30.9% (SD = 29.7%) between predicted and observed outcomes. A risk of bias assessment showed that most LMIC studies were of moderate to serious risk, reflecting systemic data limitations and a frequent reliance on proxy outcomes. These findings highlight the urgent need for recalibrated, context-sensitive frameworks that incorporate enforcement, maintenance, and socio-economic variables. Policy implications include prioritising affordable and scalable countermeasures, pairing infrastructure with enforcement and education, and strengthening crash data systems to support more realistic, evidence-based road safety planning.

1. Introduction

Road crashes are a major global public health problem, causing more than 1.35 million deaths every year and around 50 million injuries [1]. Pedestrians, cyclists, and motorcyclists account for about half of these fatalities, with pedestrians particularly vulnerable in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where more than 90 percent of pedestrian-related deaths occur [2]. The economic costs are substantial. Road traffic injuries cost LMICs between one and five percent of their gross domestic product (GDP) [3,4].

Crashes do not occur by chance, but are the outcome of unsafe acts, unsafe conditions, or both [5,6]. Pedestrian crashes are influenced by a variety of interrelated factors, including inadequate infrastructure, excessive vehicle speeds, user impairment, and human errors during planning, design, road use, and the maintenance of infrastructure [7,8]. Pedestrian safety has been studied for over a century, and numerous theories have been advanced to explain crash risk, ranging from human factor approaches to behavioural theories and traffic calming concepts [9]. This long history of research highlights the persistent complexity of protecting pedestrians, the most vulnerable group of road users.

In recognition of the urgent need for stronger action, the United Nations (UN) has promoted the Safe System approach, which emphasises multimodal transport and land use planning, safe road infrastructure, safe road use, safe vehicles, and post-crash response. Building on this framework, the UN declared a second Decade of Action for Road Safety (2021–2030), with the goal of halving road traffic deaths and injuries worldwide by 2030 [10]. Complementing this strategy, countermeasures are often grouped under the four Es concept of Education, Engineering, Enforcement, and Emergency response. Some road safety frameworks have proposed expanding this to include additional Es such as Enablement, Economics, and Ergonomics, for example, in the 7 Es approach [11].

High-income countries (HICs) have achieved substantial progress in reducing crashes and fatalities through reliable crash data systems, robust enforcement regimes, and well-resourced infrastructure programmes [9,12]. Interventions in these settings, such as pedestrian crossings, continuous sidewalks, and speed control devices (e.g., low-speed zones, traffic calming), have been field-tested and consistently shown to improve pedestrian safety [13].

In LMICs, however, the picture is different. Reliable crash data are often unavailable due to underreporting [14], which can reach up to 84 percent in some low-income settings [15]. Imported solutions from HICs have often proved ineffective in LMICs [16] because of context differences, including road conditions, user behaviour, vehicle fleets, enforcement capacity, technology, levels of awareness, funding priorities, and political stability [17,18,19].

To address the challenge of limited crash data, predictive models such as crash modification factors (CMFs) and the International Road Assessment Programme (iRAP) have been promoted. The iRAP methodology, introduced by the World Bank, was intended to assist LMICs in assessing road safety conditions and identifying appropriate countermeasures. Yet its application has sometimes produced costly recommendations and may overestimate benefits, especially when based on results from high-income country contexts [13,20]. As a result, the expected gains from pedestrian infrastructure in LMICs have frequently not been achieved, particularly in environments with weak enforcement, poor maintenance, and infrastructure encroachment.

This analysis is grounded in the Safe System and harm reduction frameworks, which emphasise system-level design, human error tolerance, and injury severity mitigation. These theoretical foundations inform the interpretation of contextual factors and guide the performance gap analysis by linking infrastructure risk, behavioural compliance, and institutional capacity within an integrated safety system.

The purpose of installing countermeasures is to remove the conflict by separating pedestrians from vehicular traffic, improving visibility, and reducing speeds [21].

This study, therefore, seeks to achieve the following:

- Identify the contextual factors that affect the effectiveness of pedestrian countermeasures implemented in LMICs through a systematic literature review (SLR).

- Identify appropriate countermeasures that consistently reduce pedestrian–vehicle fatalities in LMICs through a systematic literature review (SLR).

- Quantify the gap between the actual and expected effectiveness of countermeasures implemented in SLR’s selected LMIC case studies using the iRAP framework, and identify the contextual factors excluded from the current assessment model using comparative analysis.

This study contributes to the literature by integrating evidence synthesis with model-based performance evaluation, providing one of the first systematic assessments of pedestrian countermeasure effectiveness in LMICs. By quantifying the divergence between empirical outcomes and predictive models, it identifies critical calibration needs for context-specific safety tools and strengthens the evidence base for adapting global frameworks such as iRAP to developing country conditions.

This study tests the hypothesis that global predictive models such as iRAP systematically overestimate countermeasure effectiveness in LMICs due to omitted contextual factors and introduces an integrated framework that combines a PRISMA-based systematic review with a quantitative iRAP performance gap analysis specifically contextualised for LMIC pedestrian safety.

2. Methods

2.1. Systematic Literature Review Protocol

2.1.1. Search Strategy

A systematic search was conducted across 6 electronic databases, 23 organisational websites, and Google Scholar using key concepts and synonyms (see Table 1). The systematic search was carried out in March 2023, covering all listed databases and organisational sources. Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” [22] refined the search. Snowball/convenience sampling technique [23] was used to explore references from expert recommendations. Databases and search strings are detailed in Appendix A.1 and Appendix A.2.

Table 1.

Core concepts and their synonyms.

The systematic review protocol followed the PRISMA 2020 guidelines for transparent reporting [24] (see Supplementary Materials). However, the protocol was not prospectively registered on PROSPERO [25] or the Open Science Framework (OSF) [26]. This was due to the absence of a registry category covering transport safety reviews at the time of initiation [2023]. To ensure transparency, the complete protocol, including search strings, inclusion criteria, and screening logs, is provided in Appendix A. Future updates will be registered on OSF or PROSPERO once eligible categories become available.

2.1.2. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria:

- Focused on pedestrian road infrastructure or engineering countermeasures;

- Used a before-and-after observational design [27].

- Evaluated countermeasures over a minimum of one year before and after implementation [28,29].

- Were peer-reviewed or published by reputable organizations, in English.

- Were published between 2010 and 14 March 2023 and aligned with the UN’s Safe System Approach and the Decade of Action [30]. The selected date range (2010–2023) corresponds to the United Nations Decade of Action for Road Safety (2011–2020) and its extension to 2030, ensuring that included studies reflected interventions and policy contexts consistent with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) framework. The search covered publications up to March 2023, the point of database access.

Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) were defined according to the World Bank income classification (2024 revision), which includes all countries designated as low- or middle-income based on gross national income (GNI) per capita [31].

Studies unrelated to pedestrian safety or published in other languages were excluded.

2.1.3. Data Screening

Following PRISMA guidelines [24], all retrieved records were imported into EPPI-Reviewer 4 data management software for duplicate removal, title/abstract screening, and full-text review. Selection was guided by the criteria in Section 2.1.2. Studies were also appraised for methodological quality, analytical design, and relevance to the review’s objectives, ensuring high-quality, context-specific evidence for an adaptation framework informed by the iRAP methodology.

2.1.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

Data from eligible studies were extracted using a standardised Excel template, capturing variables such as countermeasure type, study location, design, outcome measures (e.g., crash/injury reduction), implementation duration, and contextual factors (e.g., enforcement, speed limits, user behaviour).

The data were analysed through thematic grouping and pattern recognition to identify recurring factors affecting countermeasure effectiveness. A narrative comparative analysis [rather than a meta-analysis] was employed to qualitatively compare findings between developed and developing countries. This approach was chosen because of the substantial methodological heterogeneity among included studies, including differing outcome metrics (crashes, conflicts, star ratings, speeds), intervention types, and contextual factors. Risk of bias was also assessed, and only peer-reviewed or reputable technical reports were included.

2.1.5. Study Quality Appraisal (Risk of Bias Assessment)

The fourteen included before-and-after or quasi-experimental studies were critically appraised against ROBINS-I domains (confounding; selection; intervention classification; deviations; missing data; outcome measurement; selective reporting) [32]. Disagreements in appraisal results between the two reviewers were resolved by discussion. Outcomes included both crash/injury measures and validated proxy measures (e.g., traffic conflicts; infrastructure risk/star ratings). It is important to note that this review protocol was not prospectively registered in PROSPERO or OSF, which is acknowledged as a limitation.

This structured approach ensured a robust evaluation of countermeasure effectiveness and their potential for adaptation in developing country contexts.

2.2. Evaluating Performance Gap of Case Studies from Developing Countries

Five case studies from developing countries were evaluated to quantify the performance gap between the expected (iRAP-predicted) and actual effectiveness of countermeasures. These case studies came from Ghana, Mexico, Tanzania, India, and Ghana (school zones). To ensure uniformity, the reported effectiveness data from each study, expressed using diverse units, were harmonised using crash modification factors (CMFs), consistent with the iRAP residual risk methodology.

2.2.1. Harmonisation of Different Metrics to CMFs

Various metrics, including percentage crash reduction, traffic conflicts, speed reduction, and star rating improvements, were systematically translated into CMF values in line with the iRAP methodology. This structured approach ensured consistency and comparability. The effectiveness measures from each study were aligned with corresponding CMF values by interpreting their influence on crash risk through the following methods:

- i.

- Percentage Crash Reduction → CMF

If a study reported the effectiveness as a percentage reduction in crashes or injuries, then

For example, a 21% reduction in crashes corresponds to the following:

- ii.

- Speed Reduction → Crash Reduction (Nilsson’s Power Model)

For studies reporting mean speed changes, the Nilsson Power Model was used to estimate crash reduction [33,34]:

where

and are the average vehicle speeds after/before the intervention;

= 2 for injury crashes, and = 4 for fatal crashes.

The Nilsson (2004) Power Model was adopted due to its established use in global safety assessments and integration within the iRAP predictive framework. Although Elvik [35] proposed an exponential formulation with an improved fit across severity levels, its calibration constants are data-dependent and have not been validated for LMIC contexts. This is acknowledged as a limitation, and future research could explore the Elvik model once sufficient local speed–crash datasets become available.

The Nilsson Power Model assumes a non-linear relationship between mean speed and crash occurrence, with crash risk increasing approximately with the square of speed for injury crashes and the fourth power for fatal crashes.

While this model has been widely validated in high-income country (HIC) contexts, its transferability to LMICs may vary because of differences in traffic composition, enforcement intensity, and crash-reporting accuracy.

This assumption and its contextual limitations are acknowledged and discussed in Section 4.5.

- iii.

- Conflict Rate Reduction → Crash Reduction → CMF

In cases where effectiveness was reported as a reduction in pedestrian–vehicle conflict rates, the following approximation was used:

Crash Reduction (%) ≈ Conflict Reduction (%)

This is a conservative approximation, consistent with established surrogate safety practice, where traffic conflict measures are internationally recognised proxies for crash data in the absence of reliable crash records. Previous studies have demonstrated that reductions in observed conflicts are correlated with reductions in crash frequency [36,37,38]. The approach is widely applied in LMIC research where high-quality crash databases are limited.

- iv.

- iRAP Star Rating Improvement → CMF

When safety effectiveness was reported as an improvement in iRAP star ratings, the corresponding CMF was estimated from the proportional change changes in residual risk classes, as follows:

This is a conservative, harmonising approximation that assumes that each incremental improvement in star rating corresponds to a proportional reduction in crash or fatal injury risk. Empirical research supports this inverse relationship: Ayuningtyas, Kusumawati [39] analysed Indonesian toll road data and found that the iRAP star rating score (SRS) was significantly and negatively associated with crash counts, crash rates, and fatality rates (Equations (2)–(5)). Their results confirm that roads with higher star ratings (lower SRS) experience substantially fewer crashes and fatalities.

Hence, while Equation (4) simplifies the exact non-linear SRS–risk relationship into a linear proportional form, it remains directionally consistent with observed empirical evidence and provides a reasonable, transparent means of expressing safety benefits as CMFs when direct before–after crash data are unavailable.

- v.

- Percentage Traffic Injury (RTI) Reduction → CMF

In some studies, effectiveness was expressed in terms of reductions in road traffic injuries (RTIs) rather than crashes.

To enable comparison across outcomes, the proportional injury reduction was first computed as follows:

and the corresponding crash modification factor was then approximated by the following:

This assumes that changes in injury frequency reflect proportional changes in total crash occurrence, a relationship supported by the extensive road safety literature.

Numerous meta-analyses, e.g., [27,40,41], have shown that injury-based and crash-based indicators are strongly correlated, particularly when evaluating infrastructure and speed management interventions.

Injury counts are widely used as proxy crash measures when detailed crash disaggregation or exposure data are unavailable, an accepted practice in LMIC safety analyses.

Accordingly, Equation (6) provides a conservative, harmonised approximation consistent with the established CMF methodology.

2.2.2. Calculating Combined Effectiveness Using iRAP’s Residual Risk Model

At the core of the iRAP framework is the concept of residual risk, defined as the proportion of crash risk that remains after implementing all countermeasures [3,40]. This is believed to reflect the persistent danger posed by factors such as human behaviour, demographic changes, and infrastructural limitations [41].

The effectiveness (E) of a countermeasure is calculated as follows:

where CMF represents the proportion of crash risk remaining after a specific intervention [42]. For example, a CMF of 0.7 indicates a 30% crash reduction.

The iRAP model does not sum countermeasure effectiveness additively due to the overlap in impact. Instead, it uses a multiplicative model of residual risk:

For multiple countermeasures implemented together, the combined residual risk is the product of the individual risks:

The combined effectiveness is then: the following

where

is the combined residual risk;

Effectiveness of individual countermeasures (e.g., speed humps, speed limit reduction, etc.), based on the iRAP toolkit [43].

The residual risk method ensures mathematically plausible outcomes and avoids double-counting overlapping effects [44,45].

2.2.3. Justification for Using the iRAP Residual Risk Method

The iRAP residual risk method was selected for its balance between analytical rigour and simplicity, making it especially suitable for data-scarce environments where extensive crash data are unavailable [13,41]. The residual risk method does not fully capture synergistic effects, overlapping risks, or potential errors from sequential application. However, it remains widely accepted due to its computational efficiency and use of empirically derived CMFs [27].

2.3. Variance and Standard Deviation Analysis

To quantify the variability of the differences between iRAP’s predicted and the actual effectiveness, the mean, variance, and standard deviation are computed.

The standard deviation (σ) is computed from the following equation:

To quantify uncertainty around the mean performance gap, 95% confidence intervals were calculated using Student’s t-distribution with n − 1 degrees of freedom, given the small sample size (n = 5). The confidence interval limits were derived as follows:

where μ is the mean difference and σ is the standard deviation of the observed differences.

This approach provides a statistically robust measure of variability and was used to produce the interval reported in Section 3.5.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Demographics

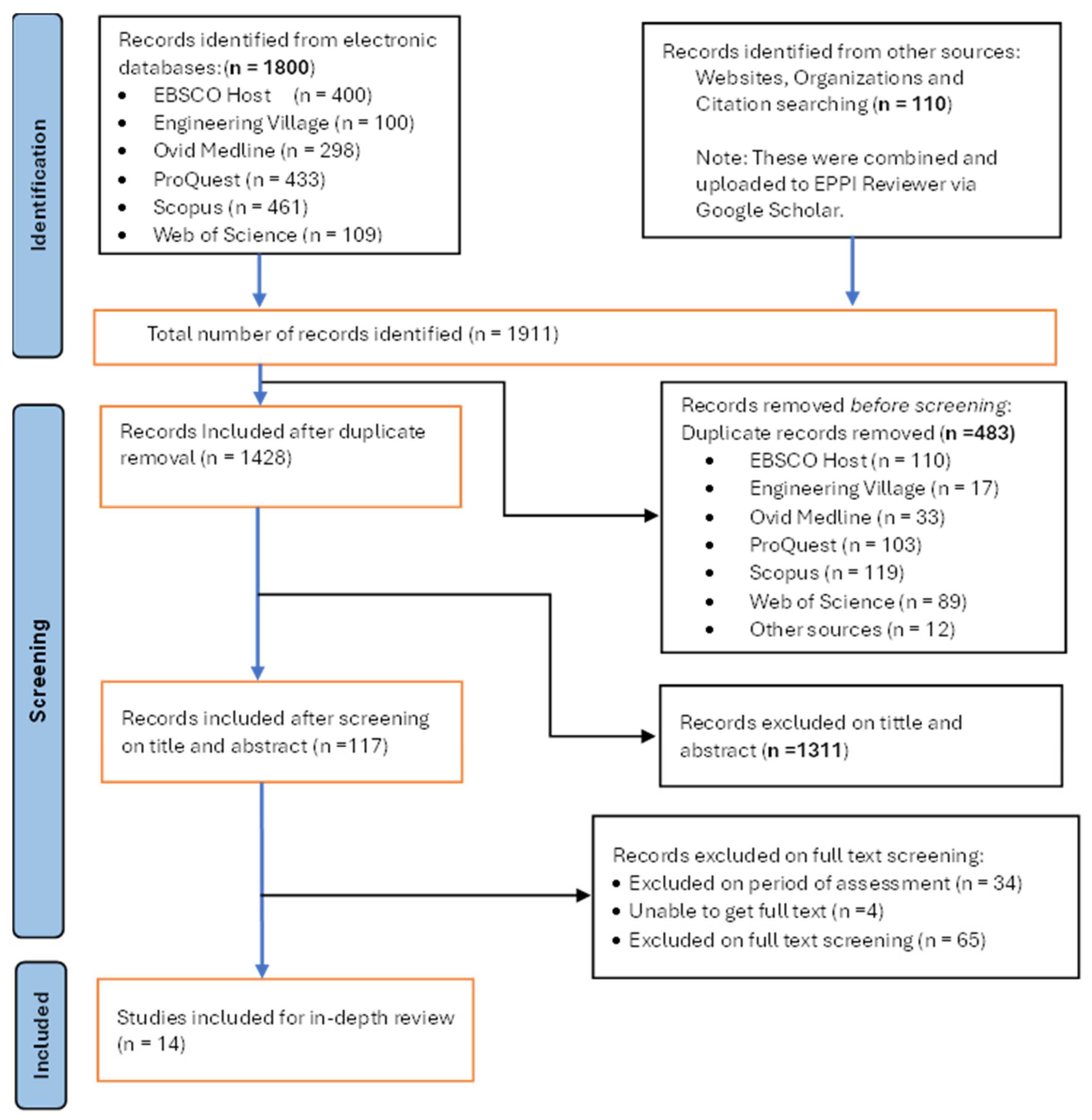

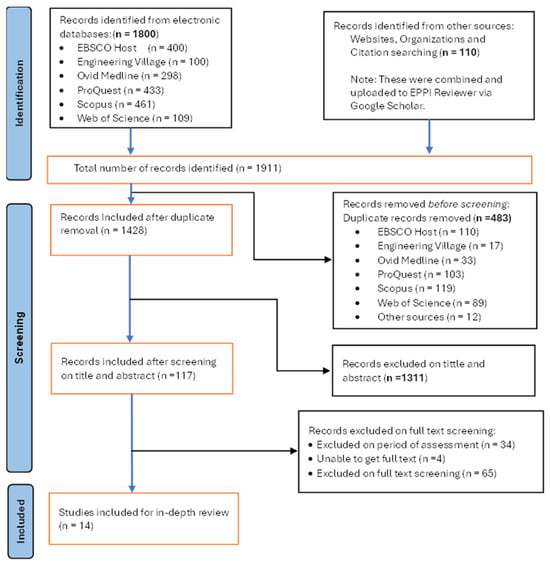

Out of 1911 initial records, 14 studies met the selection criteria for in-depth reviews (see Figure 1), evenly split between high-income countries (HICs) and low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). The dataset was geographically uneven. Six of the seven HIC studies were from the USA and one was from Poland, representing only 2.5% of all HICs globally, while the LMIC studies covered twelve countries, representing about 9% of LMICs worldwide. The LMICs included Brazil, China, Colombia, Ethiopia, Ghana, India, Indonesia, Mexico, the Philippines, Tanzania, Thailand, and Vietnam. This asymmetry may bias cross-country comparisons and reflect broader disparities in research capacity.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart for screening of studies. Adapted and modified from [24].

3.2. Factors Influencing Countermeasure Effectiveness

From the selected studies, 33 unique contextual factors influenced countermeasure effectiveness in both sets of countries. These factors were grouped into four categories, suggested by [46,47] (see Table 2), specifically the following:

Table 2.

Factors affecting the effectiveness of road infrastructure countermeasures from selected studies.

- Fourteen factors were categorised under traffic exposures and operational factors,

- Six factors under the land use and planning factors,

- Seven factors under demographic factors, and

- Six factors under the infrastructure and roadway factors.

Among these, 23 factors were specifically found to influence countermeasure effectiveness in developing countries. The grouping of factors was based on thematic similarities and their relevance to the success of countermeasures.

3.2.1. Developed Countries

A review of studies from developed countries revealed several key factors influencing countermeasure effectiveness. Boateng, Kwigizile [49] examined the effectiveness of Pedestrian Countdown Signals (PCSs) with and without push buttons and found that both traffic volume and the design of the signals significantly influenced their effectiveness. Similarly, Chen, Chen [51] developed a framework assessing 13 junction-based and segment-based countermeasures in New York City and identified exposure, conflict, speed, road users, and the built environment as critical considerations. The study emphasised that signal-based engineering measures perform better when installed at appropriate locations and noted that pedestrian behaviour could negatively impact their effectiveness.

Szagala, Brzezinski [55], using the traffic conflict method, evaluated the effectiveness of safety treatments at dual carriageway pedestrian crossings and reported that active pedestrian crossings impacted driver behaviour by influencing compliance with signal lights. Lizarazo, Hall [54] applied econometric modelling to evaluate the initial implementation of the Safe Routes to School Program in Indiana. Their findings identified several influential factors: vehicle kilometres travelled (VKT), median age of residents, school enrolment, median household income, and average annual precipitation. Specific quantified results include a 0.110 yearly increase in crash frequency for each unit increase in the log of VKT, a reduction of 0.013 crashes per year for every one-year increase in median age, and an average yearly increase of 0.05 crashes per 1000 additional students. Crashes decreased by 0.07 per $1000 increase in median income and by 0.0008 per year per 1 mm increase in precipitation. Non-infrastructure countermeasures, however, showed statistically non-significant effects.

Goughnour, Carter [50] found that pedestrian volume was a key factor in the effectiveness of the protected left-turn phasing treatment, with volumes needing to exceed 5500 pedestrians per day for effectiveness to be observed.

3.2.2. Developing Countries

In developing countries, the effectiveness of road safety countermeasures was found to be shaped by a wide range of contextual and operational constraints. Liu, Huang [56] assessed transverse rumble strips in rural China and reported significant mean speed reductions of 9.2 km/h and 11.9 km/h for roads with 60 km/h and 80 km/h speed limits, respectively. The influencing factors included posted speed limits, traffic volume, design quality, coverage area, weather conditions, and driver behaviour.

Cárdenas-Cárdenas, Gutiérrez [57] studied the Pasos Seguros Programme in Mexico and identified traffic volume, pedestrian volume, the pedestrian-to-traffic volume ratio, and hierarchical road classification as relevant determinants. Additional factors included the age, gender, hospital proximity, and the local employed population.

Damsere-Derry, Ebel [58] evaluated traffic calming measures in Ghana and found that a lack of maintenance over five years led to 80% of vehicles exceeding the posted speed limits. Factors such as the time of day, pedestrian age and gender, traffic volume (AADT), location of countermeasures, operating speed, and road classification were all influential. The adjusted odds ratio for pedestrian fatalities was 1.78 times higher in areas without countermeasures. Other limiting factors included encroachment by street vendors, improper location, and the ad hoc implementation of countermeasures.

Swanson, Draisin [59] used the pedestrian–vehicle conflict technique in Ghanaian school zones, identifying traffic speed, compliance, pedestrian behaviour, and the time of day as influential elements.

Hendrie, Lyle [60] evaluated road safety interventions under the Bloomberg Philanthropies initiative in 12 developing countries. They reported that infrastructure maintenance had a greater impact than new construction, reducing the death rate by 0.025 per 1000 euros invested. Combined non-engineering measures like legislative reform, social marketing, and police enforcement were credited with 57% of lives saved. Additional relevant factors included enforcement levels, pedestrian volume, and pedestrian-to-vehicle ratios.

Bhavsar, Tharakan [61] using the iRAP methodology on a 56 km corridor in India, identified factors such as traffic speed, enforcement level, public awareness, driver education, time of day, countermeasure design, and maintenance as essential to effectiveness.

Poswayo, Kalolo [62] examined a paediatric road safety intervention in Tanzania. Infrastructure elements included speed bumps, rumble strips, signage, zebra crossings, and bollards. The time of day (particularly mornings), vehicle age/technology, countermeasure design, and maintenance were all significant factors affecting countermeasure effectiveness.

3.3. Appropriate Countermeasures Implemented to Improve Pedestrian Safety

A total of 28 engineering and 5 non-engineering countermeasures were identified across the reviewed studies as contributing to improved pedestrian safety (see Table 3). Seven engineering countermeasures were signal-based, including Pedestrian Countdown Signals (PCSs), Lead Pedestrian Intervals (LPIs), all-pedestrian phases, increased pedestrian signal time, and signalised intersections. Other infrastructure measures included high-visibility crosswalks, painted road diets, transverse rumble strips, median refuge islands, speed tables, speed humps, road signs, crash barriers, shared bike lanes, sidewalk widening, school zone flashers, lane narrowing, posted speed limit reductions, and road markings.

Table 3.

Implemented countermeasures in each study.

Five non-engineering countermeasures were identified in developing countries: road safety education, legislative changes, social marketing, enhanced police enforcement, and improved post-crash response.

3.3.1. Developed Countries

In developed countries, statistical evidence demonstrates the effectiveness of several interventions. Boateng, Kwigizile [49] reported a 29% reduction in total pedestrian crashes and a 30% reduction in fatal/injury crashes after implementing PCSs in Michigan, USA. Goughnour, Carter [50] found a 13% reduction in vehicle–pedestrian crashes with the use of LPIs. Chen, Chen [51] reported reductions from high-visibility crosswalks (48%), all-pedestrian phases (35%), and increased pedestrian crossing times (51%).

Kitali and Sando [52] observed a 10% reduction in overall collisions and a 7.8% decrease in rear-end crashes due to PCSs. Lim and Fontaine [53] found that road diets reduced segment crashes by 38%, signalised intersection crashes by 47%, and fatal/injury crashes by 64% and 59%, respectively. Lizarazo, Hall [54] observed a reduction of 0.077 crashes per year for children near schools with shared bike lanes, sidewalk widening, and school zone flashers. Szagala, Brzezinski [55] reported an 11.5% reduction in mean speed due to lane narrowing and supported pedestrian footbridges and traffic lights as sustainable measures.

3.3.2. Developing Countries

In developing countries, Liu, Huang [56] found that transverse rumble strips led to a 25% reduction in crash frequency in rural China. Cárdenas-Cárdenas, Gutiérrez [57] reported a 21% reduction in pedestrian crashes through a combination of physical infrastructure and awareness campaigns in Mexico, although effectiveness was significantly (3-times) lower than iRAP predictions.

Damsere-Derry, Ebel [58] found that towns without speed tables had three-times higher pedestrian fatalities. Speed tables outperformed speed humps and bumps but lacked supporting pedestrian exposure data. The iRAP-estimated effectiveness exceeded the observed results by over 10%.

Swanson, Draisin [59] reported a 22% reduction in pedestrian–vehicle conflicts at school zones in Ghana using multiple measures, including reduced speed limits and site-specific education. iRAP’s predicted effectiveness was over 60% higher than the actual results.

Hendrie, Lyle [60] estimated 5111 lives saved through infrastructure and non-infrastructure measures across 11 countries using iRAP and World Resources Institute (WRI) methodologies. Differences of 13% were observed between methods, and the results lacked comparable control sites.

Bhavsar, Tharakan [61] implemented traffic calming and multi-sectoral measures in India, reporting increases in 3-star-or-better safety ratings for pedestrians (from 1% to 49%). Concerns were raised regarding the cost and health impacts of median refuge islands and speed humps.

Ref. [62] documented a decrease of 0.96 road traffic injuries (RTIs) per 100 person-years post-intervention in Tanzania. However, concerns about the sustainability of natural earth speed bumps and potential recall bias may affect the outcome.

3.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

Across the fourteen studies, nine were rated as moderate overall risk of bias and five were rated serious (see Table 4). Common strengths included the use of comparison groups, before-and-after designs, and EB, FB, or DiD methods to reduce the regression to the mean. Common weaknesses were non-random site selections, short follow-ups, an incomplete control of time-varying confounding related to exposure, enforcement, and maintenance, and a reliance on proxy outcomes such as traffic conflicts and infrastructure star ratings in several evaluations from LMICs. Studies in these settings ranged from moderate, such as controlled before-and-after designs with community controls and road traffic injury outcomes, to serious, such as estimates based on proxies or models. Examples include Swanson [59] on proxy conflicts, Hendrie [60] on modelled lives saved, Bhavsar [61] on star ratings, and Poswayo [62] on a controlled before-and-after study with self-reported road traffic injuries.

Table 4.

Quality appraisal of studies using ROBINS-I risk of bias domains.

3.5. Performance Gap Analysis of Case Studies from Developing Countries

Some case studies implemented multiple countermeasures simultaneously (e.g., speed humps combined with signage). These were analysed using the iRAP residual risk method described in Section 2.2.2, which combines overlapping effects multiplicatively. When individual contributions could not be disaggregated, the total effect was reported as a composite (combined effectiveness) in Table 5.

Table 5.

Implemented countermeasures from case studies and their combined effectiveness.

Table 5 summarises the countermeasures implemented in each case study from developing countries, showing the combined residual risk, iRAP’s predicted overall effectiveness, the actual observed effectiveness, and the resulting difference between expected and actual outcomes. The performance gap analysis is exploratory and intended to illustrate methodological feasibility rather than to derive population-level inference; the small sample size (n = 5) limits statistical power and generalisability, as acknowledged in Section 5.

The observed differences in effectiveness across five case studies ranged from −13.47% to 63.65%. The mean difference (μ) between iRAP’s predicted effectiveness and actual effectiveness across the five studies is 30.89%, with a standard deviation (σ) of 29.68%. A 95% confidence interval was computed for the mean performance gap (μ = 30.9%, SD = 29.7%), resulting in a 95% CI of [−1.5%, 63.3%], indicating a substantial variability across LMIC case studies.

A comparative analysis shows that 13 contextual factors were not included in the current iRAP assessment framework (see Table 6).

Table 6.

LMIC contextual factors excluded from the current iRAP framework as per iRAP [63].

4. Discussion

4.1. Contextual Factors Shaping Effectiveness

The review underscores the diverse contextual influences on pedestrian countermeasure performance. In high-income countries (HICs), signal-based interventions such as Pedestrian Countdown Signals and protected phases demonstrated significant crash reductions when aligned with pedestrian volumes and user behaviour [49,50,51]. These successes are enabled by advanced data systems, systematic urban planning, and strong enforcement regimes.

In LMICs, effectiveness was shaped by a broader set of constraints. Poor infrastructure quality, weak enforcement, inadequate maintenance, and encroachment by informal activities such as street vending were consistently reported as limiting factors [58,60]. Socio-economic and demographic variables including income, gender, vehicle technology, and pedestrian age further influenced safety outcomes [57,62]. These findings confirm earlier observations that LMICs face structural challenges in enforcement, governance, and data systems that differ fundamentally from those in HICs [4].

These contextual factors (as highlighted in Table 2) guided the interpretation of the performance gap analysis, allowing the identification of which unmodeled variables most likely explain the observed discrepancies between predicted and actual effectiveness.

4.2. Appropriate Countermeasures in Different Contexts

Distinct patterns emerge between contexts. In HICs, countermeasures such as road diets, protected intersections, and countdown signals delivered consistent and statistically significant results [51,53,55]. By contrast, LMICs recorded a mixed effectiveness. Transverse rumble strips stood out as the only countermeasure producing consistent crash reductions across settings [56]. Other interventions such as speed humps, median refuges, and school zone improvements showed a variable effectiveness, often falling short of iRAP predictions [51,61]. Concerns about unintended consequences, including the link between speed humps and spinal injuries [64,65], raise questions about sustainability and transferability. Furthermore, the sustainability of natural earth speed bumps and the potential recall bias in the Poswayo, Kalolo [62] study raises more concerns on the outcomes.

4.3. The Role of Non-Engineering Countermeasures

Several studies highlight the importance of non-engineering measures such as enforcement, education, and public awareness in enhancing the effectiveness of infrastructure-based countermeasures [59,60]. Evidence from LMICs shows that, when such measures are implemented alongside engineering solutions, they lead to significant reductions in pedestrian–vehicle conflicts and are likely to translate into fewer injuries and fatalities. This aligns with the Safe System approach, which is grounded in a harm reduction philosophy that seeks to minimise serious outcomes from crashes rather than relying on perfect compliance [16]. The reviews of LMIC interventions further confirm that infrastructure alone rarely delivers the anticipated benefits unless supported by institutional and behavioural change, with enforcement and policy interventions often proving the most impactful [20,66,67].

4.4. Representativeness and Risk of Bias

The risk of bias assessments revealed a clear regional divide. Among high-income country (HIC) studies, six of seven were rated moderate and only one serious, usually reflecting residual confounding or a non-random site selection [49,50,51,52,53,54,55].

In contrast, four of the seven LMIC studies were rated serious. This was driven mainly by outcome measurement, where evaluations relied on surrogate measures such as iRAP star ratings [61], traffic conflict counts [59], or speed and compliance indicators [58], and by modelling outcomes at the programme level [60]. Under ROBINS-I, a single high-risk domain determines the overall rating [68], so otherwise well-designed studies were downgraded when the primary outcomes were proxies rather than crash data.

Nevertheless, moderate-risk LMIC examples, such as controlled before–after studies with community controls [62] and difference-in-differences designs using municipal crash data [57], demonstrate that higher-quality evaluations are feasible when data are available. A short follow-up and residual confounding remain frequent challenges, however.

These patterns suggest that lower ratings in LMICs stem more from systemic data constraints than from weaknesses in design standards. The use of surrogate outcomes is established in road safety research and can be informative, but their predictive validity varies and benefits from calibration against local crash data [37,69,70]. In contexts where crash records are sparse, structured expert elicitation and consensus approaches such as modified Delphi studies have been applied to identify priorities and fill evidence gaps in road safety planning [19,71]. Strengthening crash databases while leveraging these complementary methods will be critical for improving the representativeness and credibility of LMIC evidence.

The modest number of included studies (n = 14) reflects both the limited availability of high-quality LMIC data and the strict inclusion criteria applied in this review (before–after or quasi-experimental design with at least one year of follow-up). While this small sample inevitably constrains the statistical generalizability of the findings, it also underscores the persistent evidence gap in LMIC pedestrian safety research, precisely the gap that this study seeks to highlight and address through methodological harmonisation.

Additional limitations include a potential publication bias arising from the exclusion of non-English and unpublished (grey literature) studies, as well as an incomplete control for data quality issues such as underreporting in LMIC crash databases and inconsistencies in exposure measurement. Moreover, the validity of proxy outcomes (e.g., traffic conflicts, star ratings, or compliance indicators) may vary across contexts and can influence the representativeness and external validity of the aggregated results. These factors should be considered when interpreting the findings and underscore the need for an improved data transparency and standardisation in future pedestrian safety research.

4.5. Performance Gaps in Predictive Models

A central finding of this review is the substantial performance gap between the predicted and observed effectiveness in LMICs, averaging 30% across five case studies. In practical terms, this means that the iRAP-predicted effectiveness systematically overestimates real-world crash reductions by nearly one third in LMIC contexts. Such overestimation indicates that key contextual modifiers such as enforcement, maintenance quality, and user compliance are insufficiently represented in the model’s underlying assumptions.

This gap results from the exclusion of variables such as enforcement, maintenance quality, institutional capacity, and informal road use [15,72].

Current crash modification factors are calibrated in HICs, where assumptions of strong governance, compliance, and infrastructure integrity generally hold true. In LMICs, however, these assumptions do not reflect reality. As Elvik [41] notes, the uncertainty in crash modification factors is particularly pronounced when transferring them across contexts, underscoring the need for recalibration.

Despite this overestimation, iRAP’s predictive trends remain directionally consistent: interventions that are predicted to perform better generally correspond to a higher observed effectiveness, albeit at reduced magnitudes. This consistency suggests that the iRAP framework remains a provisionally useful tool for prioritising pedestrian safety interventions in LMICs until sufficient local calibration datasets become available.

All seven studies from HICs were validated against iRAP effectiveness estimates. Since these studies primarily assessed individual countermeasures, their observed outcomes closely aligned with iRAP’s predicted effectiveness, generally within ±10–15%. This correspondence confirms that iRAP’s predictive models are well calibrated for HIC conditions, supporting the rationale for focusing this analysis on identifying performance divergences in LMIC contexts [43].

Interpretation of Mechanisms Behind the Performance Gap

The observed divergence between predicted and actual effectiveness can be attributed to several interacting mechanisms operating at the data, methodological, and contextual levels.

Data underreporting and exposure uncertainty remain key contributors in LMICs. A systemic underreporting of crashes and injuries often exceeding 50% distorts baseline frequencies, which inflates apparent post-intervention gains and complicates model calibration [15].

Site selection bias also plays a role, as demonstration or donor-funded pilot projects are often implemented in relatively better-maintained or highly visible locations. Such sites are not representative of typical urban corridors and may yield inflated short-term benefits.

Regression-to-the-mean effects, a common concern in before-and-after evaluations, were largely mitigated in the included studies through Empirical Bayes or Full Bayes adjustments [27]. Therefore, this factor is unlikely to explain the magnitude of the residual 30% performance gap observed across the case studies.

Enforcement and maintenance quality exert strong moderating effects. Countermeasures that depend on behavioural compliance, such as pedestrian crossings, speed humps, and signage, show diminishing effectiveness when enforcement is inconsistent or when maintenance lapses, conditions frequently reported in LMIC settings [72].

Finally, informal road use behaviour, including midblock crossings, roadside vending, and pedestrian encroachment, violates the assumptions embedded in iRAP’s calibration, which presumes a formal traffic discipline typical of HICs. These unmodelled behavioural and institutional dynamics together explain much of the residual bias in the model-predicted effectiveness.

In sum, the performance gap arises less from statistical artefacts and more from omitted contextual variables such as enforcement intensity, infrastructure maintenance, and socio-behavioural factors that systematically alter real-world intervention outcomes in LMICs.

4.6. Alternative Frameworks and Policy Implications

Emerging approaches offer pathways for addressing these limitations. The Theory of Change pathway, proposed in the current pedestrian safety manual [7], encourages linking interventions to intermediate- and long-term outcomes, thereby capturing the contextual influences overlooked by models such as iRAP. Similarly, a harm reduction approach [73] is aligned with the Safe System philosophy, advocating for incremental improvements that accept human error while minimising harm [16].

The evidence suggests that LMICs should avoid a direct transfer of HIC models and instead pursue locally adapted frameworks. Policymakers must invest not only in countermeasure installation but also in enforcement, maintenance, and institutional strengthening.

To establish a clearer analytical linkage between contextual factors and model structure, Table 6 maps each contextual determinant identified in this review (e.g., maintenance quality, enforcement, institutional capacity, land use, pedestrian behaviour) to the corresponding iRAP assessment parameters. This mapping highlights which contextual dimensions are currently represented, underrepresented, or absent from the iRAP framework. Although quantitative parameterisation was not feasible with the available data, this matrix provides a conceptual foundation for integrating contextual sensitivity into future model calibration and refinement.

Research should prioritise generating high-quality, context-specific evidence to refine predictive tools and inform policy decisions.

5. Conclusions

This review demonstrates that applying uncalibrated global prediction models such as iRAP in LMICs leads to a systematic overestimation of pedestrian countermeasure effectiveness. Across the reviewed studies, 23 contextual factors were identified as key modifiers of outcomes in developing countries, yet 13 of these remain largely absent from global models. Of all the interventions assessed, only transverse rumble strips consistently achieved reliable safety benefits across LMIC contexts.

The performance gap analysis (the key contribution) revealed an average discrepancy of approximately 30% between predicted and observed effectiveness, illustrating a critical mismatch between model assumptions and LMIC realities. This gap highlights the urgent need for locally calibrated frameworks that incorporate enforcement, maintenance, and socio-economic variables.

This study’s methodological limitations should be acknowledged. The analysis was based on a small number of LMIC case studies (n = 5), relied partly on surrogate metrics such as conflicts and star ratings for CMF estimation, and did not include formal meta-analytic pooling due to the heterogeneity in study designs. These constraints limit the statistical generalisability of the findings but provide a robust exploratory foundation for methodological refinement and future validation across larger, multi-country datasets.

Finally, limitations in the evidence base, including a moderate to serious bias and reliance on proxy outcomes, further reflect systemic capacity gaps in LMICs. Addressing these challenges will require improved data systems, recalibrated models, and integrated approaches that combine infrastructure with enforcement, education, and governance reform. By embedding countermeasures within broader systems of road safety management, LMICs can move towards more realistic, effective, and sustainable reductions in pedestrian deaths and injuries.

6. Recommendations

6.1. Short-Term

- LMIC policymakers should prioritise affordable and scalable interventions such as transverse rumble strips, high-visibility markings, and low-cost traffic calming before adopting expensive signal-based infrastructure.

- Pair engineering measures with enforcement and education, ensuring that interventions are supported by police monitoring, community engagement, and awareness campaigns.

- Establish maintenance and monitoring frameworks to prevent the rapid deterioration of countermeasures and sustain long-term effectiveness.

- Use sensitivity analyses anchored to the observed performance gap, reporting ranges of effectiveness rather than single-point estimates.

6.2. Long-Term Systemic Reforms

- Global tools such as iRAP should be recalibrated by integrating LMIC-specific variables including enforcement levels, maintenance quality, institutional capacity, and informal road use into predictive models.

- Invest in local data systems to improve crash reporting, surveillance, and road safety audits, reducing the reliance on proxy outcomes.

- Develop integrated, context-sensitive frameworks that combine engineering solutions with behavioural, institutional, and environmental measures.

- Expand empirical research to quantify the influence of contextual factors absent from current models (see Table 6), using methods such as expert elicitation, simulation modelling, and long-term field studies.

- Adopt harm reduction and Theory of Change approaches as complementary frameworks for planning, particularly in settings where incremental, system-wide improvements are more feasible than a reliance on individual countermeasures.

- Strengthen institutional and human capacity in road safety agencies to support evidence-based planning, enforcement, maintenance, and monitoring.

- A policy highlight has also been drafted and included in Appendix A.3.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/futuretransp6010029/s1, PRISMA 2020 Checklist [24].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M. and H.E.; methodology, analysis, and writing, J.M.; supervision, H.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the reported results can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the Commonwealth Scholarship Commission and the University of Birmingham for providing the necessary resources.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations and terms are used in this manuscript:

| AASHTO | American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials |

| CBA | Cost Benefit Analysis |

| CMF | Crash Modification Factor |

| DiD | Difference-in-Difference |

| EB | Empirical Bayes |

| FB | Full Bayes |

| HIC | High-Income Countries |

| iRAP | International Road Assessment Programme |

| LMIC | Low- and Middle-Income Countries |

| LPI | Lead Pedestrian Intervals |

| PCS | Pedestrian Countdown Signals |

| PDO | Property Damage Only |

| RTI | Road Traffic Injuries |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| TCT | Traffic Conflict Technique |

| UN | United Nations |

| VKT | Vehicle Kilometres Travelled |

| WB | World Bank |

| WHO | World Health Organisation |

| Glossary of Terms | |

| Term | Definition/Description |

| Actual Effectiveness | The empirically observed crash or injury reduction following the implementation of a countermeasure, derived from before-and-after studies. |

| Combined Effectiveness | The total effectiveness of multiple countermeasures applied jointly, calculated using the iRAP residual risk method. |

| Countermeasure | Any engineering, enforcement, or education intervention intended to reduce crash risk or severity. |

| Countermeasure Coverage | The proportion of sites, locations, or road lengths where a countermeasure was fully implemented relative to the planned scope. |

| Crash Modification Factor (CMF) | A multiplicative factor expressing the proportion of crash risk remaining after applying a countermeasure; (CMF = 1 − Effectiveness). |

| Crash Reduction (%) | The percentage decrease in crashes after implementing a countermeasure, used to derive CMFs. |

| Enforcement Strength | The degree to which road safety regulations (e.g., speed limits, pedestrian priority) are applied, monitored, and complied with. |

| Exposure Frequency | The rate at which road users (e.g., pedestrians, vehicles) interact with a specific pedestrian facility influencing crash likelihood. |

| Institutional Capacity | The ability of local agencies to plan, implement, and maintain road safety interventions effectively. |

| iRAP (International Road Assessment Programme) | A predictive model framework used to estimate road safety performance and star ratings based on infrastructure and traffic characteristics. |

| Maintenance Quality | The condition and upkeep of road infrastructure features (e.g., markings, signage, crossings) affecting countermeasure durability and visibility. |

| Observed Effectiveness | See Actual Effectiveness. |

| Performance Gap | The difference between iRAP-predicted and observed countermeasure effectiveness, expressed as a percentage. |

| Predicted Effectiveness | The expected crash or injury reduction estimated by iRAP models using CMFs and residual risk calculations. |

| Residual Risk (RR) | The proportion of crash risk that remains after implementing countermeasures; combined multiplicatively for multiple interventions. |

| Residual Severity | The remaining injury severity after countermeasure application, related to crash outcomes rather than crash frequency. |

| Risk of Bias | The likelihood that systematic error or study design limitations affect the validity of reported findings. |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Databases Used

- Electronic bibliographic databases

- EBSCOhost

- Geobase and Compendex (Ei Engineering village)

- Ovid—Medline and EMBASE

- ProQuest

- Scopus

- Web of Science

- Organisation websites

- AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety

- ARRB—Australian Road Research Board

- European Transport Safety Council (ETSC)

- European Union Road Federation (ERF)

- Institute of Civil Engineers (ICE) Virtual library

- International Road Federation (IRF)

- International Transport Forum (ITF)

- International Transport Research Documentation (ITRD)

- iRAP—International Road Assessment Programme

- ITE—Institute of Transportation Engineers

- Knovel

- Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) Road Safety Working Group

- NHTSA—National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, USA

- SafetyLit

- SWOV—Institute for Road Safety Research

- TØI—Norway Institute of Transport Economics

- TRL Limited—Transport Research Laboratory

- United Nations Road Safety Collaboration (UNRSC)

- US Department of Transport—Federal Highway Administration (FHWA)

- World Bank—Global Road Safety Facility (GRSF)

- WHO —World Health Organization

- PIARC—Permanent International Association of Road Congress (World Road Association)

- SSATP—Africa Transport Policy Program

Appendix A.2. Search Strings

- EBSCOhost (400 Records after removing duplicates, 14 March 2023)

((Factor* OR Agent* OR Enabler* OR Driver* OR Element* OR Component* OR Aspect* OR Characteristic* OR Cause* OR Influence* OR Contributor* OR Variable* OR Determinant* OR Parameter*)) AND ((Effectiveness OR Efficiency OR Efficacy OR Success OR Convincingness OR Performance* OR Capability* OR Potency OR Benefit* OR Impact”)) AND ((Pedestrian* road infrastructure) OR (Pedestrian infrastructure) OR (Pedestrian facilities) OR (Pedestrian -friendly infrastructure) OR (Non-motorized infrastructure) OR (Non-motorised infrastructure) OR (Walkway*) OR (Footway*) OR (Sidewalk*) OR (Footpath*) OR (Crosswalk*) OR (Shoulder*) OR (Pedestrian oriented infrastructure) OR (Human-powered transportation infrastructure) OR (Pedestrian traffic infrastructure) OR (Underpass*) OR (Overpass*) OR (Foot bridge*) OR (Overbridge*) OR (Pedestrian zone*)) AND (Countermeasure* OR Measure* OR Intervention* OR Treatment* OR Improvement* OR Safeguard* OR Precaution* OR Antidote* OR Vaccine* OR Solution*) AND ((Pedestrian safety OR Traffic safety OR Road safety OR Pedestrian road safety OR Pedestrian accidents OR Pedestrian crash risk OR Vulnerable road users OR Road transport safety OR Highway safety OR Accident prevention OR Road user safety OR Road safety engineering OR Pedestrian behavior OR Pedestrian behaviour))

- Engineering Village (100 Records, 14 March 2023)

(((((((((Factors OR Agents OR Enablers OR Drivers OR Elements OR Components OR Aspects OR Characteristics OR Causes OR Influences OR Contributors OR Variables OR Determinants OR Parameters) AND (Effectiveness OR Efficiency OR Efficacy OR Success OR Convincingness OR Performance OR Capability OR Potency OR Benefit OR Impact) AND (Pedestrian road infrastructure OR Pedestrian infrastructure OR Pedestrian facilities OR Pedestrian-friendly infrastructure OR Non-motorized infrastructure OR Non-motorised infrastructure OR Walkway OR Footway OR Sidewalk OR Footpath OR Crosswalk OR Shoulder OR Pedestrian oriented infrastructure OR Human-powered transportation infrastructure OR Pedestrian traffic infrastructure OR Underpass OR Overpass OR Foot bridge OR Over bridge OR Pedestrian zone)))) WN ALL) AND ((Countermeasure* OR Measure* OR Intervention* OR Treatment* OR Improvement* OR Safeguard* OR Precaution* OR Antidote* OR Vaccine* OR Solution*) WN KY)) AND (((Pedestrian* safety) OR (Pedestrian road safety) OR (Pedestrian crash risk) OR (Walking safety) OR (Pedestrian protection) OR (Safe walking) OR (Sidewalk* safety) OR (Vulnerable Road users) OR (Road crossing safety) OR (footpath* safety) OR (Pedestrian injury*) OR (Crosswalk safety) OR (Pedestrian fatality*) OR (safe pedestrian environment) OR (Pedestrian detection system*) OR (Safe* route*)) WN KY))) AND (((cpx or c84 OR geo) WN DB) AND (([49] OR {d) WN DT) AND ({english} WN LA)))

- Ovid Medline (298 Records, 14 March 2023)

(Factor* OR Agent* OR Enabler* OR Driver* OR Element* OR Component* OR Aspect* OR Characteristic* OR Cause* OR Influence* OR Contributor* OR Variable* OR Determinant* OR Parameter*) AND (Effectiveness OR Efficiency OR Efficacy OR Success OR Convincingness OR Performance* OR Capability* OR Potency OR Benefit* OR Impact”) AND (road infrastructure or highway infrastructure or street infrastructure or street furniture or pedestrian infrastructure or traffic engineering infrastructure or road engineering infrastructure or built environment or pedestrian facilities or infrastructure safety rating or safety infrastructure) AND (Countermeasure* OR Measure* OR Intervention* OR Treatment* OR Improvement* OR Safeguard* OR Precaution* OR Antidote* OR Vaccine* OR Solution*) AND (Pedestrian* safety OR Pedestrian road safety OR Pedestrian crash risk OR Walking safety OR Pedestrian protection OR Safe walking OR Sidewalk* safety OR Vulnerable Road users OR Road crossing safety OR Footpath* safety OR Pedestrian injury* OR Crosswalk safety OR Pedestrian fatality* OR safe pedestrian environment OR Pedestrian detection system* OR Safe* route*)

- ProQuest (433 Records, 14 March 2023)

(Factor* OR Agent* OR Enabler* OR Driver* OR Element* OR Component* OR Aspect* OR Characteristic* OR Cause* OR Influence* OR Contributor* OR Variable* OR Determinant* OR Parameter*) AND (Effectiveness OR Efficiency OR Efficacy OR Success OR Convincingness OR Performance* OR Capability* OR Potency OR Benefit* OR Impact) AND (“Pedestrian* road infrastructure” OR “Pedestrian infrastructure” OR “Pedestrian facilities” OR “Pedestrian -friendly infrastructure” OR “Non-motorized infrastructure” OR “Non-motorised infrastructure” OR “Walkway*” OR “Footway*” OR “Sidewalk*” OR “Footpath*” OR “Crosswalk*” OR “Shoulder*” OR “Pedestrian oriented infrastructure” OR “Human-powered transportation infrastructure” OR “Pedestrian traffic infrastructure” OR “Underpass” OR “Overpass” OR “Foot bridge” OR “Overbridge” OR “Pedestrian zones”) AND summary (“Countermeasure*” OR “Measure*” OR “Intervention*” OR “Treatment*” OR “Improvement*” OR “Safeguard*” OR “Precaution*” OR “Antidote*” OR “Vaccine*” OR “Solution*”) AND summary (“Pedestrian safety” OR “Pedestrian road safety” OR “Pedestrian crash risk” OR “Walking safety” OR “Pedestrian protection” OR “Safe walking” OR “Sidewalk safety” OR “Vulnerable Road users” OR “Road crossing safety” OR “footpath safety” OR “Pedestrian injury” OR “Crosswalk safety” OR “Pedestrian fatality*” OR “safe pedestrian environment” OR “Pedestrian detection system*” OR “Safe* route*”)

- Scopus (461 Records, 14 March 2023)

((ALL (factor* OR agent* OR enabler* OR driver* OR element* OR component* OR aspect* OR characteristic* OR cause* OR influence* OR contributor* OR variable* OR determinant* OR parameter*) AND ALL (effectiveness OR efficiency OR efficacy OR success OR convincingness OR performance* OR capability* OR potency OR benefit* OR impact) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Pedestrian* road infrastructure” OR “Pedestrian infrastructure” OR “Pedestrian facilities” OR “Pedestrian -friendly infrastructure” OR “Non-motorized infrastructure” OR “Non-motorised infrastructure” OR “Walkway*” OR “Footway*” OR “Sidewalk*” OR “Footpath*” OR “Crosswalk*” OR “Shoulder*” OR “Pedestrian oriented infrastructure” OR “Human-powered transportation infrastructure” OR “Pedestrian traffic infrastructure” OR “Underpass” OR “Overpass” OR “Foot bridge” OR “Overbridge” OR “Pedestrian zones”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Countermeasure*” OR “Measure*” OR “Intervention*” OR “Treatment*” OR “Improvement*” OR “Safeguard*” OR “Precaution*” OR “Antidote*” OR “Vaccine*” OR “Solution*”))) AND (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Pedestrian safety” OR “Pedestrian road safety” OR “Pedestrian crash risk” OR “Walking safety” OR “Pedestrian protection” OR “Safe walking” OR “Sidewalk safety” OR “Vulnerable Road users” OR “Road crossing safety” OR “footpath safety” OR “Pedestrian injury” OR “Crosswalk safety” OR “Pedestrian fatality*” OR “safe pedestrian environment” OR “Pedestrian detection system*” OR “Safe* route*”))

- Web of Science (109 Records, 14 March 2023)

Factor* OR Agent* OR Enabler* OR Driver* OR Element* OR Component* OR Aspect* OR Characteristic* OR Cause* OR Influence* OR Contributor* OR Variable* OR Determinant* OR Parameter* (All Fields) and Effectiveness OR Efficiency OR Efficacy OR Success OR Convincingness OR Performance* OR Capability* OR Potency OR Benefit* OR Impact (All Fields) and “Pedestrian* road infrastructure” OR “Pedestrian infrastructure” OR “Pedestrian facilities” OR “Pedestrian -friendly infrastructure” OR “Non-motorized infrastructure” OR “Walkway*” OR “Footway*” OR “Sidewalk*” OR “Footpath*” OR “Crosswalk*” OR “Shoulder*” OR “Pedestrian oriented infrastructure” OR “Human-powered transportation infrastructure” OR “Pedestrian traffic infrastructure” OR “Underpass” OR “Overpass” OR “Foot bridge” OR “overbridges” OR “Pedestrian zones” (All Fields) and “Countermeasure*” OR “Measure*” OR “Intervention*” OR “Treatment*” OR “Improvement*” OR “Safeguard*” OR “Precaution*” OR “Antidote*” OR “Vaccine*” OR “Solution*” (All Fields) and “Pedestrian safety” OR “Pedestrian road safety” OR “Pedestrian crash risk” OR “Walking safety” OR “Pedestrian protection” OR “Safe walking” OR “Sidewalk safety” OR “Vulnerable Road users” OR “Road crossing safety” OR “footpath safety” OR “Pedestrian injury” OR “Crosswalk safety” OR “Pedestrian fatality*” OR “safe pedestrian environment” OR “Pedestrian detection system*” OR “Safe route*” (All Fields) | 109 results

Appendix A.3. Policy Highlights

Pedestrian safety remains a critical challenge in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where global predictive tools such as iRAP often overestimate the benefits of countermeasures. This review of 14 studies found that effectiveness is shaped by 23 contextual factors, including enforcement, maintenance, and informal road use, which are rarely included in global models.

Transverse rumble strips were the only countermeasure consistently effective in LMIC settings, while other interventions such as speed humps, median refuges, and school zone improvements produced mixed results. A performance gap analysis revealed that the predicted effectiveness was, on average, 30 percent higher than the observed outcomes.

To improve outcomes, LMICs should prioritise affordable and scalable measures, ensure that enforcement and maintenance accompany all interventions, and report results as ranges to reflect uncertainty. Over the longer term, recalibrating global models, strengthening crash data systems, and adopting harm reduction and Theory of Change approaches will be essential. These steps will help policymakers design interventions that are realistic, cost-effective, and locally relevant.

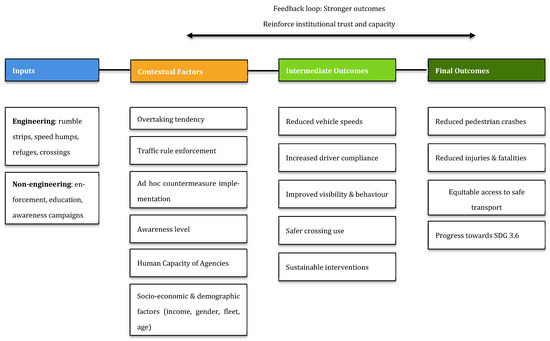

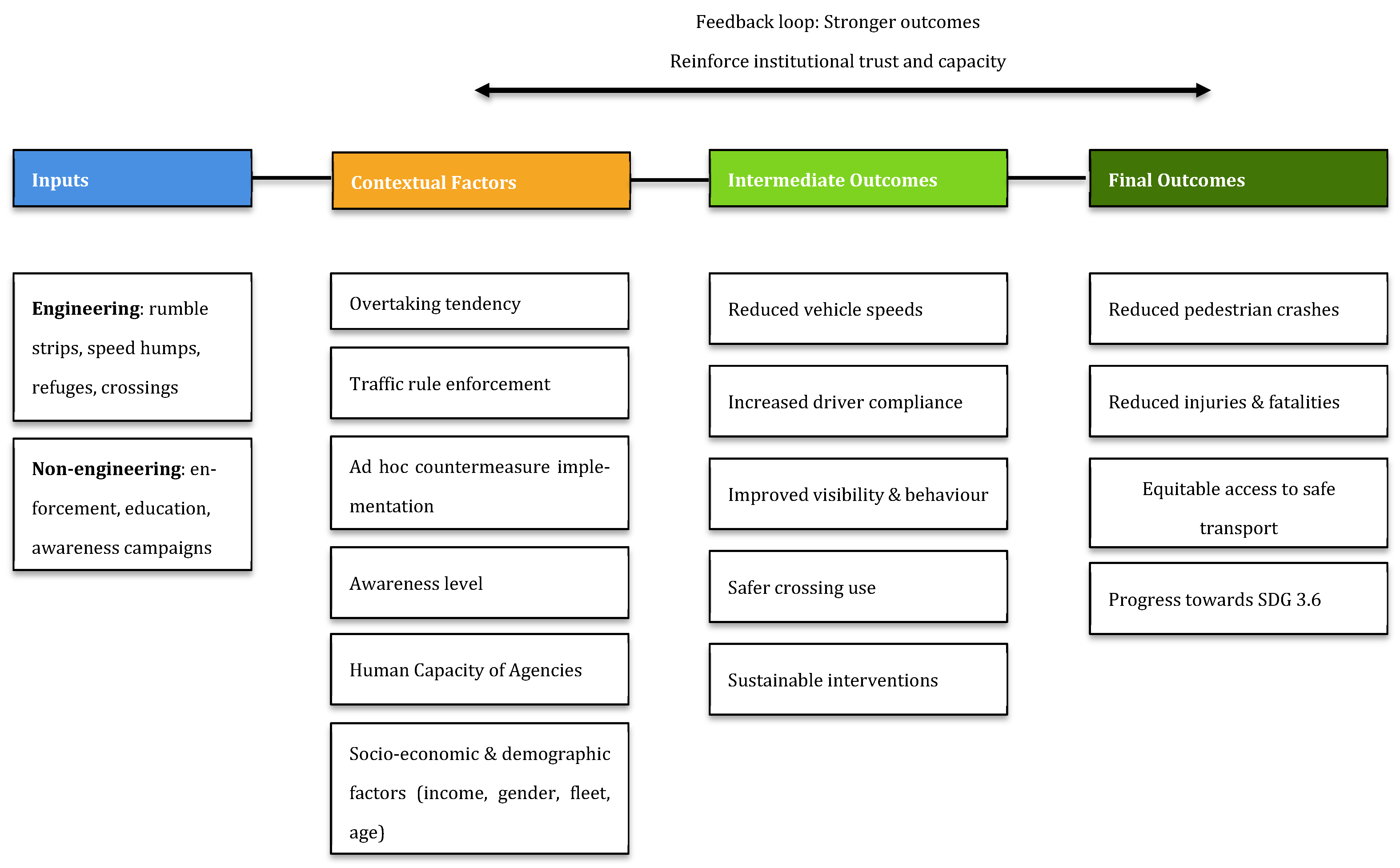

Figure A1.

Theory of Change pathway for pedestrian safety in LMICs.

Figure A1.

Theory of Change pathway for pedestrian safety in LMICs.

Here, countermeasures and interventions interact with contextual factors such as enforcement, maintenance, and socio-economic conditions. These factors shape intermediate outcomes including compliance and speed reduction, which ultimately determine the reductions in crashes, injuries, and fatalities. The feedback loop highlights how stronger safety outcomes can build institutional trust and the capacity for future interventions.

Figure A2.

Performance gap framework comparing predicted effectiveness from global models with observed outcomes in LMICs.

Figure A2.

Performance gap framework comparing predicted effectiveness from global models with observed outcomes in LMICs.

Global crash modification factors, calibrated in high-income contexts, assume a strong enforcement and institutional capacity. The observed effectiveness in LMICs is on average 30% lower, with a high variability. Contextual factors such as weak enforcement, poor maintenance, and socio-economic conditions explain this gap and underscore the need for locally calibrated models.

References

- WHO. Global Status Report on Road Safety 2023; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; p. 81. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, C.R.; Job, S.; Sekerinska, L.; Bose, D.; Dahdah, S.; Raffo, V.; Burlacu, A.F. Good Practice Note: Road Safety; World Health Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/documents/health-topics/road-traffic-injuries/global-plan-for-road-safety.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Byaruhanga, B.C. Economic Optimisation of Road Network Safety Investment Programmes. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Peden, M.M. World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hemoud, A.M.; Al-Asfoor, M.M. A behavior based safety approach at a Kuwait research institution. J. Saf. Res. 2006, 37, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reason, J. Human Error; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Pedestrian Safety: A Road Safety Manual for Decision-Makers and Practitioners; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Budzynski, M.; Guminska, L.; Jamroz, K.; Mackun, T.; Tomczuk, P. Effects of Road Infrastructure on Pedestrian Safety. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 603, 042052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, R.; Tiwari, G.; Varghese, M.; Bhalla, K.; Agrawal, G.; Saini, G.; Jha, A.; John, D.; Saran, A.; White, H.; et al. Effectiveness of road safety interventions: An evidence and gap map. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2024, 20, e1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Global Plan for Decade of Action for Road Safety, 2021–2030; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Plant, K.; McIllroy, R.C.; Stanton, N.A. Taking a ‘7 E’s’ Approach to Road Safety in the UK and Beyond. Contemp. Ergon. Hum. Factors 2018, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bliss, T.; Breen, J.M. Road Safety Management Capacity Reviews and Safe System Projects Guidelines (Updated Edition); Global Road Safety Facility: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, B.; Job, S.; Mitra, S. Guide for Road Safety Interventions: Evidence of What Works and What Does Not Work; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; p. 62. [Google Scholar]

- Thierry, M.; Vet, J.; Uddin, K.B.; Wegman, F. A New Methodology for Road Crash Data Collection in Bangladesh Using Local Record Keepers. J. Road Saf. 2023, 34, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Job, R.S.; Wambulwa, W.M. Features of low-income and middle-income countries making road safety more challenging. J. Road Saf. 2020, 31, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegman, F. The future of road safety: A worldwide perspective. IATSS Res. 2017, 40, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downing, A.J. Pedestrian safety in developing countries, in Vulnerable Road User. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Traffic Safety, New Delhi, India, 27–30 January 1991; Macmillan India Ltd.: New Delhi, India, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Downing, A.J.; Sayer, I.A.; Zaheer-ul-Islam, M. Pedestrian Safety in the Developing World; Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office: Berkshire, UK, 1993.

- Heydari, S.; Hickford, A.; McIlroy, R.; Turner, J.; Bachani, A.M. Road safety in low-income countries: State of knowledge and future directions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godthelp, H.; Ksentini, A. Specific road safety issues in low- and middle income countries (LMICs): An overview and some illustrative examples. Traffic Saf. Res. 2024, 8, e000068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.; Baguley, C.; McDonald, M.; Silcock, D. Towards Safer Roads in Developing Countries: A Guide for Planners and Engineers. In A Guide for Planners and Engineers; Transport Research Laboratory: Berkshire, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Alharbi, A.; Stevenson, M. Refining Boolean queries to identify relevant studies for systematic review updates. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2020, 27, 1658–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, C.; Scott, S.; Geddes, A. Snowball sampling. In SAGE Research Methods Foundations; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York. PROSPERO: International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews. 2025. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Framework, O.S. OSF Registries. 2025. Available online: https://osf.io/registries (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Hauer, E. Observational Before/After Studies in Road Safety. Estimating the Effect of Highway and Traffic Engineering Measures on Road Safety; Emerald Publishing: Leeds, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- AASHTO. Highway Safety Mannual, 1st ed.; The American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO): Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Harwood, D.W.; Torbic, D.J.; Richard, K.R.; Meyer, M.M. SafetyAnalyst: Software Tools for Safety Management of Specific Highway Sites; Turner-Fairbank Highway Research Center: McLean, VA, USA, 2010; p. 304. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global Plan for the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2011–2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. 2024. Available online: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Jüni, P.; Loke, Y.; Pigott, T.; Ramsay, C.; Regidor, D.; Rothstein, H.; Sandhu, L.; Santaguida, P.; Schünemann, H.; Shea, B. Risk of bias in non-randomized studies of interventions (ROBINS-I): Detailed guidance. Br. Med. J. 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, M.H.; Elvik, R. Nilsson’s Power Model connecting speed and road trauma: Does it apply on urban roads. In Proceedings of the Australasian Road Safety Research, Policing and Education Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 30 September–1 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Elvik, R. The Power Model of the Relationship Between Speed and Road Safety: Update and New Analyses; Institute of Transpot Economics Norwegian Centre for Transport Research: Oslo, Norway, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Elvik, R.; Vadeby, A.; Hels, T.; van Schagen, I. Updated estimates of the relationship between speed and road safety at the aggregate and individual levels. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2019, 123, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Sayed, T.; Mannering, F. Modeling traffic conflicts for use in road safety analysis: A review of analytic methods and future directions. Anal. Methods Accid. Res. 2021, 29, 100142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gettman, D.; Head, L. Surrogate Safety Measures from Traffic Simulation Models. Transp. Res. Rec. 2003, 1840, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hydén, C. The Development of a Method for Traffic Safety Evaluation: The Swedish Traffic Conflicts Technique; Bulletin Lund Institute of Technology, Department: Lund, Sweden, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Ayuningtyas, K.; Kusumawati, A.; Pangestika, S.H.; Hadiyanti, I. The Relationships Between iRAP Star Rating Score and Various Safety Performance Indicators. Int. J. Technol. 2024, 15, 1349–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murozi, A.-F.M.; Ishak, S.Z.; Nusa, F.N.M.; Hoong, A.P.W.; Sulistyono, S. The application of international road assessment programme (irap) as a road infrastructure risk assessment tool. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 13th Control and System Graduate Research Colloquium (ICSGRC), Shah Alam, Malaysia, 22–23 July 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Elvik, R. Problems in determining the optimal use of road safety measures. Res. Transp. Econ. 2014, 47, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Abdel-Aty, M.; Lee, C. Exploration and comparison of crash modification factors for multiple treatments on rural multilane roadways. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2014, 70, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- iRAP. Road Safety Toolkit; International Road Assessment Programme (iRAP): Hampshire, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Marafi, M.N.; Somasundaraswaran, K. A review of the state-of-the-art methods in estimating crash modification factor (CMF). Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2023, 20, 100839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- iRAP. iRAP Methodology Fact Sheets. 2021. Available online: https://irap.org/methodology/ (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Lin, P.-S.; Guo, R.; Bialkowska-Jelinska, E.; Kourtellis, A.; Zhang, Y. Development of countermeasures to effectively improve pedestrian safety in low-income areas. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. (Engl. Ed.) 2019, 6, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, D.; Mitra, S. Modelling risk factors for fatal pedestrian crashes in Kolkata, India. Int. J. Inj. Control Saf. Promot. 2020, 27, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamadeh, N.; Van Rompaey, C.; Metreau, E. New World Bank Country Classifications by Income Level: 2021–2022, in Data Blog. 2021. Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/opendata/new-world-bank-country-classifications-income-level-2021-2022 (accessed on 14 March 2023).

- Atta Boateng, R.; Kwigizile, V.; Oh, J.-S. A comparison of safety benefits of pedestrian countdown signals with and without pushbuttons in Michigan. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2018, 19, 588–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goughnour, E.; Carter, D.; Lyon, C.; Persaud, B.; Lan, B.; Chun, P.; Hamilton, I.; Signor, K.; Bryson, M. Evaluation of Protected Left-Turn Phasing and Leading Pedestrian Intervals Effects on Pedestrian Safety. Transp. Res. Rec. 2021, 2675, 1219–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chen, C.; Ewing, R.; McKnight, C.E.; Srinivasan, R.; Roe, M. Safety countermeasures and crash reduction in New York City—Experience and lessons learned. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2013, 50, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitali, A.E.; Sando, P.E.T. A full Bayesian approach to appraise the safety effects of pedestrian countdown signals to drivers. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2017, 106, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, L.; Fontaine, M.D. Development of Road Diet Segment and Intersection Crash Modification Factors. Transp. Res. Rec. 2022, 2676, 660–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizarazo, C.G.; Hall, T.; Tarko, A. Impact of the Safe Routes to School Program: Comparative Analysis of Infrastructure and Noninfrastructure Measures in Indiana. J. Transp. Eng. Part A Syst. 2021, 147, 04020151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szagala, P.; Brzezinski, A.; Kiec, M.; Budzynski, M.; Wachnicka, J.; Pazdan, S. Pedestrian Safety at Midblock Crossings on Dual Carriageway Roads in Polish Cities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Huang, J.; Wang, W.; Xu, C. Effects of transverse rumble strips on safety of pedestrian crosswalks on rural roads in China. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2011, 43, 1947–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas-Cárdenas, L.M.; Gutiérrez, T.B.; Quistberg, D.A.; Chias-Becerril, L.; Martínez-Santiago, A.; Lopez, H.R.; Ferrer, C.P. One-year impact of a multicomponent, street-level design intervention in Mexico City on pedestrian crashes: A quasi-experimental study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2023, 77, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]