Abstract

Road transport across Asia is undergoing rapid motorisation and exemplifies growing road safety challenges, with rising accident rates closely linked to driver behaviour. Recent reports indicate that Vietnamese drivers often perceive risk as manageable and enforcement as inconsistent, contributing to habitual violations such as speeding, signal ignoring, and risky manoeuvres, particularly when traffic is light. Evidence shows that riders, especially young adults, feel confident controlling their vehicles and frequently disregard safety warnings. This study investigates traffic safety awareness among motorcyclists and car drivers in Hanoi, based on a questionnaire survey of 393 respondents. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was used to group 11 attitudinal statements into key components influencing road safety perceptions, identifying five: non-compliance with traffic regulations (Component 1), aggressive driving behaviour (Component 2), traffic signal issues (Component 3), road quality and infrastructure (Component 4), and preventive measures (Component 5). Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) and two-step cluster analysis (TCA) were then applied to determine user clusters by socio-demographic characteristics, producing three groups: young adults in employment riding motorcycles (Cluster 1), young adults in education riding motorcycles (Cluster 2), and mature adults in employment driving cars (Cluster 3). Finally, Multinomial Logistic Regression (MLR) was applied to assess variations in road safety perceptions across the different groups (clusters). Mature adults driving cars (Cluster 3) identified the first four components as significant, with Components 1 and 2 showing negative associations and Components 3 and 4 positive associations.

1. Introduction

With population growth and urbanisation, transportation systems are continually evolving to meet the rising travel demands of people. While transportation offers significant economic and social benefits, road safety remains a critical global challenge. According to the World Health Organization (2015) [1], approximately 1.3 million people die and around 50 million suffer from permanent disabilities each year due to road traffic accidents. The causes of motorised vehicle accidents are multifaceted but are largely influenced by driver-related factors such as speeding [2], alcohol consumption [3], inexperience [4], and risk-taking behaviour [5]. Previous studies have suggested that driver behaviour contributes to over 90% of traffic crashes [6]. This high percentage may be attributed to the fact that human drivers are inherently susceptible to errors and violations, both intentional and unintentional.

In recent decades, Southeast Asian countries such as Indonesia, Vietnam, and Thailand have experienced rapid growth in motorisation. As reported in 2021, the road traffic crash fatality rate in Vietnam stood at 17.7 per 100,000 population, higher than the Asia-Pacific average of 15.2 and the Southeast Asia average of 14.4 [7]. In the Southeast Asian region, motorised two- and three-wheeler riders represent the highest proportion of road traffic fatalities among vulnerable road users, accounting for 43%, while fatalities involving four-wheeled vehicles constitute 16%. As reported by Asian Transport Observatory [7], the corresponding figures for Vietnam were 57% for two- or three-wheeled vehicles, 35% for four-wheeled vehicles, and the remaining 7% for other road users. Furthermore, the World Health Organisation (2018) [8] reported that over 90% of road traffic deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries, highlighting the urgent need for targeted safety interventions in these regions.

The human factor is widely recognised as the most significant contributor to traffic collisions, alongside vehicle-related and environmental factors [9]. Among the various components of human factors, road user behaviour has been identified as the most influential [10]. Motorcyclist behaviours such as speeding and manoeuvring through congested traffic can negatively affect other vehicles and may contribute to a disproportionately high rate of motorcycle accidents and injuries [10]. Consequently, road safety education and behaviour change have become key priorities within policy frameworks [7]. Research on road user behaviour is therefore essential for developing effective strategies to reduce traffic crashes. Understanding the factors that shape individuals’ perceptions of road safety is critical for evaluating their awareness and attitudes toward traffic risks. This insight enables the formulation of targeted interventions that address specific behavioural issues, ultimately enhancing overall road safety.

This research aims to assess transport users’ awareness of road safety issues in Hanoi, the capital city of Vietnam, with a particular focus on the motorised vehicle user group.

The specific objectives of this study are as follows:

- To identify key human factors influencing road safety through a comprehensive literature review and to design a structured questionnaire to collect data on transport users’ attitudes and perceptions toward traffic safety in Hanoi.

- To conduct detailed analyses to uncover underlying patterns and insights related to transport users’ awareness and perceptions of road safety.

- To identify priority areas for policy interventions that can effectively improve traffic safety for road users in Hanoi.

Using Hanoi as a case study, this research provides valuable insights into road user behaviour and traffic safety awareness within a rapidly motorising urban environment. The findings not only contribute to a deeper understanding of road user behaviour in Vietnam but also offer implications for traffic safety strategies in other developing countries, particularly in relation to strengthening public awareness and adherence to safety norms.

2. Literature Review

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) and Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member countries have expressed serious concern over the alarming state of road safety in the ASEAN region, primarily composed of developing countries, and its adverse effects on societal development [11]. Vietnam, the focus of this research, is a Southeast Asian country and a member of ASEAN. It falls within the low- to middle-income category according to global economic classifications (2017) and continues to face severe road safety challenges. Each year, Vietnam records approximately 14,000 road traffic fatalities, with most victims aged between 25 and 49 years. Notably, motorcyclists account for nearly 59% of these fatalities, highlighting their extreme vulnerability on the roads. This is especially concerning given the dominance of motorcycles in the country’s vehicle fleet, a common trend in many developing nations where motorcycles are the most affordable and flexible mode of transport [12]. In addition to the high fatality rate, concerns have been raised about the effectiveness of Vietnam’s traffic laws and enforcement mechanisms [8]. Despite government efforts and increasing attention to road safety in recent years, the number of traffic accidents remains persistently high. Motorcyclists are particularly at risk, with head injuries being the leading cause of death or serious injury in crashes [13]. These patterns underscore the urgent need for targeted interventions and robust policy enforcement to improve road safety in Vietnam and similar contexts.

2.1. Factors Influencing Road Safety

Dissanayake and Wedagama [14] define pedestrian safety as arising from four interconnected domains: individual characteristics, vehicle and driver attributes, road design features, and environmental/land use factors. Given the critical importance of road safety and existing research gaps, this study focuses on factors influencing road safety. A summary of the previous literature is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary table of research and factors considered.

A recent study used data from the Integrated Road Safety Management System (IRSMS) and performed descriptive analysis by crash type, road configuration, geometric road type, and road surface condition [15]. Lee et al. [16] developed an interpretable machine-learning framework to identify roadway infrastructure factors that influence road accident likelihood. They found that the factors that decrease accident likelihood are lane width (e.g., wider lanes reduce accident probability) and shoulder width (e.g., wider shoulders lower the risk).

Akgun et al. [17] investigated how the geometric design features of roundabouts influence cyclist casualty severity, using UK STATS19 national collision data. They found that the number of lanes on approach and entry path radius increase the odds of serious injury. Azin et al. [18] analysed 320 Utah urban arterial segments to assess how lane width affects speed and crash likelihood. Their findings support the use of narrower lanes to enhance safety and promote sustainable urban transport. One study from Bali, Indonesia, revealed that reckless or careless driving/riding significantly contributes to pedestrian accidents during both day and night. Junctions and pedestrian crossings were perceived as the most dangerous locations compared to footpaths. The study also found that motorcycles pose a greater risk to pedestrians than cars [19]. In Japan, notice failure and bicycle stunts were the strongest predictors of violations among cyclists, while instrumental attitude and conformity tendency influenced pedestrian behaviour [20]. In Thailand, traffic errors and motorcycle stunts were the most significant factors for motorcycle users, and pedestrian violations were shaped by instrumental attitude, descriptive norms, and conformity tendency [20].

Recent research by Doan and Hobday [21] examined 352 hospitalised motorcyclists in Ho Chi Minh City to identify crash characteristics and factors associated with injury severity. Severe injuries occurred in 6.8% of cases. Unlicensed vehicles, speeding, not wearing helmets, and using mobile phones were noted as the causes for serious injuries. One study in the USA [22] concluded that injury severity stems from interactions between driver behaviour (especially speeding), roadway design, vehicle characteristics, and environmental conditions. This highlights the need for improved driver training, speed management, and roadway design interventions to reduce speeding-related harm.

Sohaee & Bohluli [23] examined how a wide spectrum of socioeconomic, demographic, and technological variables collectively influences the frequency of fatal traffic accidents in the USA. Using a Lasso-based polynomial regression model, the authors analysed demographic indicators such as income, education, unemployment rates, and family size, alongside socioeconomic variables like GDP per capita, inflation, minimum wage, and government spending on transportation. They also incorporated technological aspects including vehicle advancements. The analysis identified several key contributors to fatal accident rates, including alcohol consumption, unemployment, minimum wage levels, and vehicle miles travelled (VMT). Panumasvivat et al. [24] conducted a study on rural motorcyclists in Thailand using binary logistic regression. Key factors contributing to accidents included drunk driving, changing lanes without signalling, listening to music while riding, and failure to wear helmets. Research by Jima & Sipos [25] explored how road geometry (such as bends, straight segments, and crossroads) is linked to the distribution of traffic crashes, associated economic losses, and the assessment of the severity levels of different road segments. Thibenda et al. [26] examined drivers’ attitudes toward road safety in Jakarta and Hanoi using large-scale surveys and advanced statistical methods. They emphasised that drivers’ perceptions of what affects road safety vary significantly across socio-demographic groups and between cities.

This review indicates that most studies have relied on variables readily available from existing data or surveys, primarily focusing on casualties. Only a few studies have examined user perceptions [19,20,26]. Dissanayake and Wedagama [14] emphasised the importance of considering both actual and perceived safety risks in policymaking. The present research will focus on driver perceptions to contribute to ongoing studies in developing countries.

2.2. Motorcyclists’ Behaviour in Developing Countries

Statistical evidence indicates that motorcycles dominate the vehicle fleet in many developing countries, and this dominance is often linked to higher rates of traffic collisions. Factors such as the loss of rider balance during travel and the small size of motorcycles, which increases their vulnerability to being overlooked or struck by larger vehicles, significantly contribute to crash risks [27]. A study examining the factors influencing motorcycle speed on Malaysian roads identified rider characteristics and riding behaviour as the two most critical determinants [28]. At the global level, helmet use has been shown to significantly reduce the risk of serious injury and death in motorcycle crashes by up to 72%, according to [13]. Studies of traffic risk behaviours among Thai motorcyclists emphasised that accurate risk perception plays a vital role in helmet usage, with correct and consistent use being a key protective factor [24].

With regard to motorcycle helmet usage in Vietnam, Hung et al. [29] argued that there are many factors linked to the usage of helmets, such as the law of helmet usage officially being put into legislation or outside weather conditions which may impact riders’ willingness to wear helmets. Interestingly, in a survey, this research found that although up to 95% of riders using motorcycles agreed that wearing helmets could help lower the chances of suffering from severe injuries, they still thought it undesirable to wear them during a short trip. The same authors, hence, concluded that it is imperative for the government to make helmet wearing mandatory during road travel and put further emphasis on education to lessen negative attitudes towards helmet usage, especially in uncomfortable weather conditions. Vietnamese researchers [30] discovered that motorcycle riders often either wear low-quality helmets or wear helmets the wrong way, reducing their effectiveness in protecting wearers’ heads.

These findings underscore the importance of addressing behavioural and perceptual elements when formulating policies aimed at improving motorcycle safety in developing countries. Awareness campaigns to address this issue are often voluntary initiatives led by social organisations rather than mandatory measures enforced by law. To better understand road users’ behaviour, Hoekstra [31] highlighted the importance of incorporating insights from other disciplines, such as social psychology and economics, for more effective outcomes. They also stressed the critical role of education in improving road users’ awareness of traffic safety

3. Methodology

3.1. Case Study

This study was conducted in Hanoi, the capital city of Vietnam, to analyse transport users’ awareness and perception towards road safety. This is Vietnam’s leading political, economic, and cultural hub. Hanoi is the city with the second largest number of motorcycles in the world, with 653 motorcycles per 1000 citizens (Vietnam Television Online Newspaper), comprising 86% of total transport vehicles in Hanoi. The prevalence of motorcycles leads to traffic rush hours, specifically in the peak morning hours when people go to work or school and a peak in the afternoon when they return home. Figure 1 shows the peak hour at the intersection Giang Vo–Lang Ha–La Thanh–De La Thanh. Rapid vehicle growth during rush hours creates congestion hotspots in the urban area, leading to the potential for collisions to occur.

Figure 1.

Rush hour at Giang Vo–Lang Ha–La Thanh–De La Thanh intersection in Hanoi.

3.2. Data Collection

This study targeted road users, including car drivers, motorcyclists, and bus passengers, living in the central districts. The data was collected using a questionnaire survey that was designed with particular attention to the survey conducted by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) for similar research in Kampala, Uganda, in 2014. This agency is a governmental agency with the responsibility of assisting economic and social growth in developing countries and the promotion of international cooperation. Because of its purpose, the questionnaire created by JICA is suitable and realistic for a developing country like Vietnam. Therefore, it was used as a basis for the questionnaire design in this study with some adjustment to ensure its applicability in the context of Hanoi, Vietnam.

The questionnaire consisted of two main sections.

- The first section included 10 items capturing the respondents’ residential district and a range of socio-demographic details, including household characteristics (e.g., income, vehicle ownership), individual attributes (gender, age, occupation), and driving-related factors such as driving experience, frequency of driving, vehicle type, and prior exposure to traffic safety education.

- The second section focused on assessing drivers’ road safety awareness across four thematic areas: safe driving tips, driving through intersections, road traffic accidents, and road traffic safety (Table 2). Each theme was divided into 2–4 subthemes, each containing 5–10 statements designed to capture the respondents’ agreement or disagreement through dichotomous YES/NO responses.

Table 2.

The themes covered in the questionnaire survey.

Table 2.

The themes covered in the questionnaire survey.

| Themes | Questions |

|---|---|

| Safe Driving Tips |

|

| Driving through Intersections |

|

| Traffic Accidents |

|

| Traffic Safety |

|

To ensure clarity and accessibility, the questionnaire was translated into the relevant local language and subsequently back translated to identify and correct any errors before finalisation. The initial idea was to collect data using online platforms, but the method of data collection was changed to in-person data collection given the nature of the survey.

The sample size required for the questionnaire survey was estimated by the method proposed by [32].

where

p = proportion or incidence of cases. Assuming worst-case scenario, p = 0.5.

e = value of error in result; 10% error = 0.1, 5% error = 0.05.

z = standardised score for level of confidence; z = 1.96 is used for 95% confidence level.

N = total population being studied = 7,000,000 people.

Using Equation (1), the required sample size for this study was calculated as 385 respondents. With 393 fully completed questionnaires collected, the minimum sample size criterion was satisfied. This indicates that the sample is sufficiently large to be considered representative of Hanoi’s population.

A stratified random sampling approach was employed for respondent selection, with districts in Hanoi serving as the basis for stratification. This ensured proportional representation across administrative areas. Table 3 presents the distribution of the study sample in relation to the population structure, illustrating how closely the sample aligns with the demographic composition of the city.

Table 3.

Population and sample statistics.

3.3. Methodology for Data Analysis

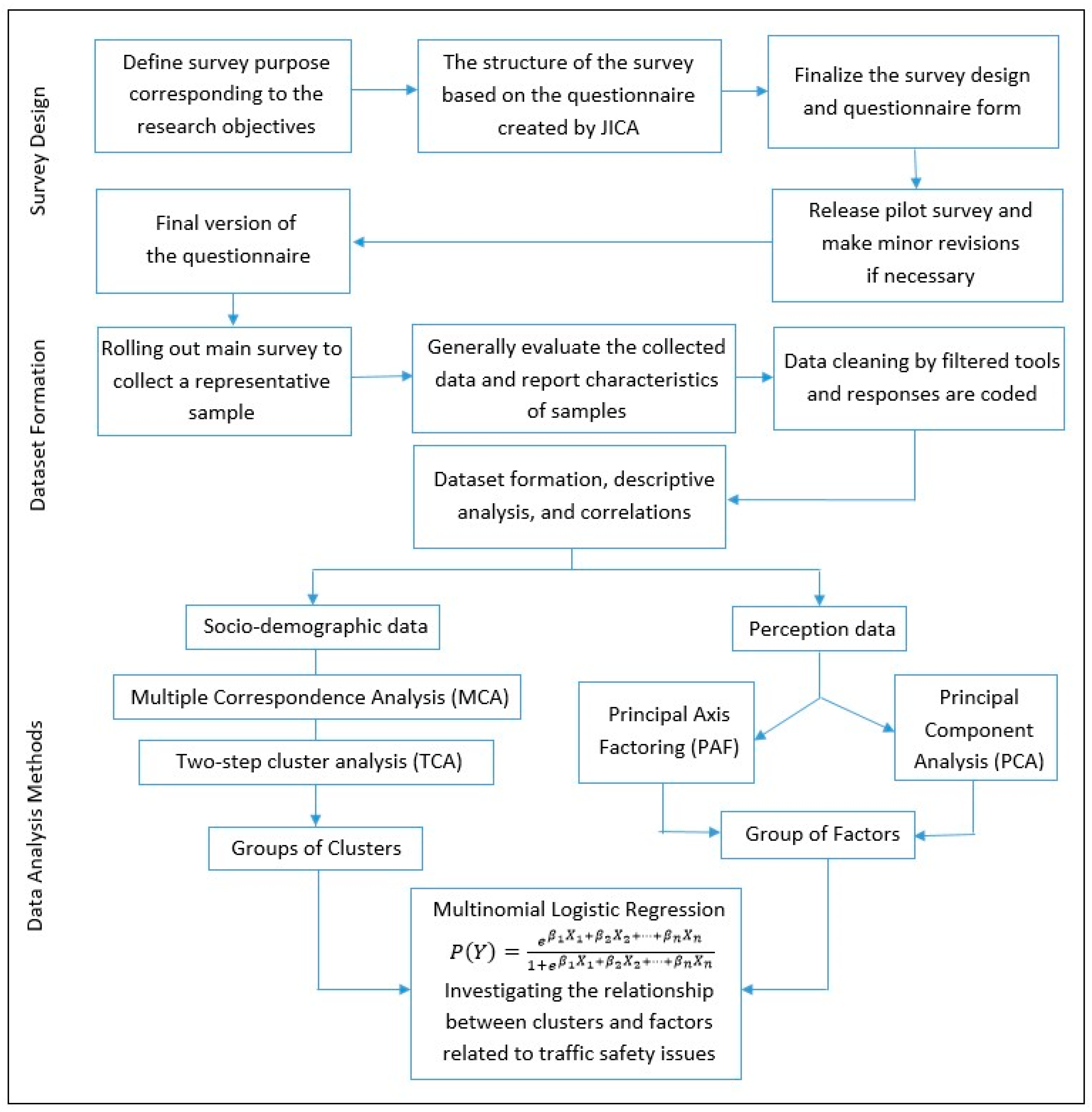

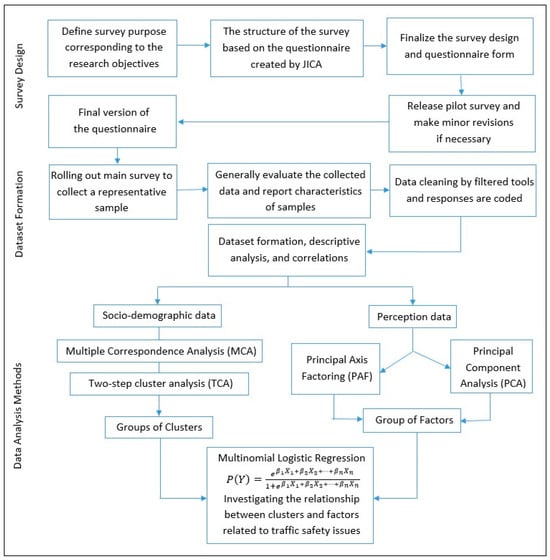

The methodology used in this study is illustrated in Figure 2. Prior to undertaking analysis, data was thoroughly checked and coded. Answers were assigned as a serial number, and this formed the primary dataset for any statistical analyses. For dichotomous questions, such as those regarding gender or road safety education, the answers were coded as “1” or “2”. Additionally, another type of question allowed respondents to choose only one answer from more than just two options to be coded in a similar way to dichotomous questions, including those regarding living district, occupation, income, driving experience, and frequency. Furthermore, for the questions that allowed responders to choose more than one answer, the ordered numbers corresponding to a respondent’s answers were as shown in the choice’s column and could be coded as “0”. Socio-demographic variables were coded as nominal data, whereas the perception of traveller variables was set as ordinal data. After the descriptive analysis, two groups including socio-demographic characteristics and perceptions were formed to gain an in-depth understanding of the data.

Figure 2.

Methodology flowchart.

3.3.1. Analysing Perception Data to Generate Factors/Components

Researchers have employed exploratory techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [26] and Principal Axis Factoring (PAF) [33] for dimension reduction, which is particularly useful when dealing with datasets containing numerous attitudinal questions or statements. Rather than examining each question individually, reducing dimensions allows for a more holistic understanding of the data. In this study, both PCA and PAF were applied, and the method yielding the highest factor/component scores was retained.

3.3.2. Analysing Socio-Demographic Data to Identify Clusters/Groups

Researchers have used Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) to uncover hidden structures and relationships within complex categorical data, reducing many variables into fewer underlying dimensions for easier visualisation and interpretation, especially when exploring associations between different types of qualitative data like demographics. Its application varies depending on research objectives. For example, Thibenda et al. [26] employed MCA to generate linear scores for hierarchical clustering, while Ali et al. [33] used MCA to create intuitive two-dimensional maps illustrating distances and relationships between categories and individuals. In this study, MCA was applied to screen variables for inclusion in the cluster analysis. This study uses two-step cluster analysis (TCA) due to the fact that socio-demographic data consists of both continuous and categorical variables.

3.3.3. Investigating How Different Clusters Respond to the Factors/Components Identified

While MCA and TCA were employed to segment travellers into groups and examine differences between them, PCA and PAF were used to reduce dimensions and consolidate perception variables into components. Subsequently, the significant relationships between these components and clusters were analysed using a Multinomial Logistic Regression (MLR) model. This approach provides a fundamental understanding of road users who express concerns about road safety. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 24.

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

4.1.1. Socio-Demographic Data

A dataset comprising 393 complete responses was used to generate the descriptive statistics presented under the thematic categories of transport mode preference, gender, age and occupation, education and awareness, vehicle ownership, and driving experience.

Transport Mode Preference

More than 60% of people chose motorcycles as their main transport mode for their daily commute, whereas only 14.56% used cars and 19.59% used buses for trips in and around Hanoi, Vietnam. The percentage of people using buses as the main mode for commuting accounts for one fifth of the total respondents, which shows that private vehicles are preferred to public transport.

Gender, Age, and Occupation

The number of male respondents was higher than that of female respondents, corresponding to up to 55%. Sixty percent of the respondents were in the age range of 19–29 years. According to previous studies about the influence of age on road safety, younger drivers are more likely to cause collisions compared to older drivers [34]. The next two main age ranges of respondents consist of those younger than 19 years old and those from 29 to 39 years old; the people in these age ranges are the main daily commuters. Most respondents are full-time or part-time workers or students, adding up to a total of 83.71%. These dominant groups are clearly the main commuters in the urban area based on their daily activities such as going to work, shopping, etc.

Education and Awareness

The respondents’ qualification results reveal that over 60% are highly educated, having either graduated from university or completed a master’s degree. This aligns with the data collected on traffic safety education, where 75.57% of respondents indicated that they had received road safety education at school. However, a significant proportion still lacked such education. Factors such as the absence of road safety education for many drivers, combined with relatively low economic development, contribute to the prevalence of road traffic collisions [35].

Vehicle Ownership

The vehicle ownership results show that 66% of respondents own two or more than two motorcycles, as pointed out in the literature review regarding the area as Vietnam is dominated by motorcycles, and this is also a significant problem in other Asian countries [36]. These vehicle ownership patterns are symptomatic of the rapid motorisation characteristic of an emerging, middle-income economy like Vietnam. Asked about experience in riding/driving vehicles, almost 50% of respondents have 1–5 years of driving experience. The increased prevalence of young motorcyclists is intrinsically linked to the motorcycle’s function as the primary, cost-effective, and highly adaptable mode of transport for the daily commute within Hanoi’s congested urban environment.

Driving Experience

When asked whether traffic safety in Hanoi is an important issue that requires attention, respondents gave it an overall rating of 4.1 out of 5. When being asked about their behaviour related to traffic signals, 52.93% of respondents indicated that they would reduce their speed when crossing intersections when the traffic signal is green, and 77.86% of respondents answered that they would reduce their speed when they see a traffic light turn from amber to red, then wait for a red light; surprisingly, the other 22.14% would choose to cross the intersection when the light is amber even if a red light would appear a few seconds later.

Many people (78.81%) found that they experienced traffic collisions in Hanoi at least a few times per year. Then, when being asked about one to two main factors that cause traffic collisions in Hanoi, 81.42% of respondents indicated that motorcycles are the main cause, while 47.58% of people blamed cars for their mistakes regarding traffic collisions. In addition, regarding the time that collisions normally happen at, most people (36.4%) chose the time frame from 4pm to 9pm. This matches with the literature review concerning rush hour in Hanoi when people go home from work and school, which leads to a dramatic rise in travelling demand and consequently increases the potential of causing traffic collisions.

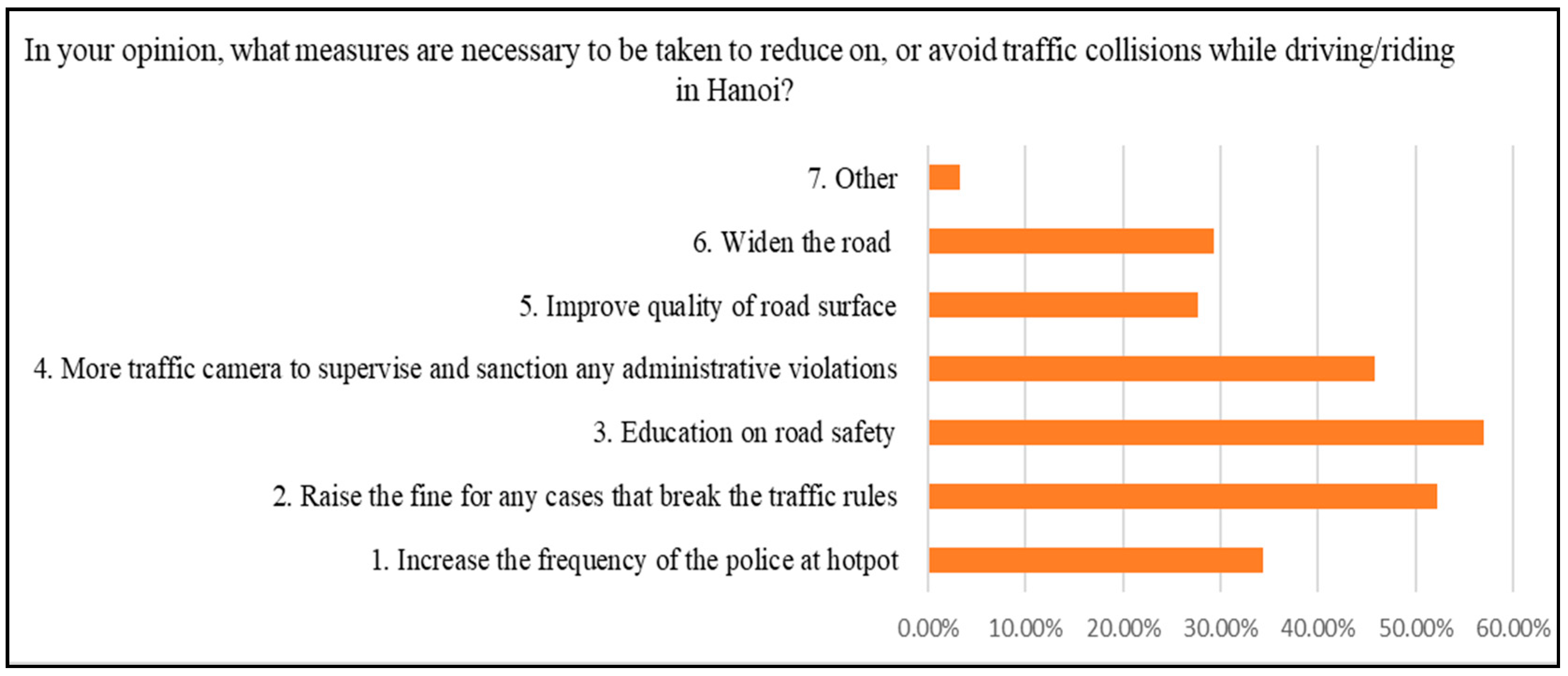

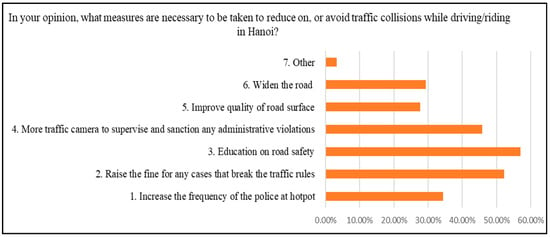

Open-ended questions allowed the respondents to suggest measures for reducing traffic collisions in Hanoi, which included awareness campaigns, stricter enforcement of traffic laws with higher fines, and improved traffic facilities like wider roads and cameras. Limiting the number of vehicles per family was also proposed. Most respondents rated Hanoi’s road safety quality as low, requiring urgent improvements.

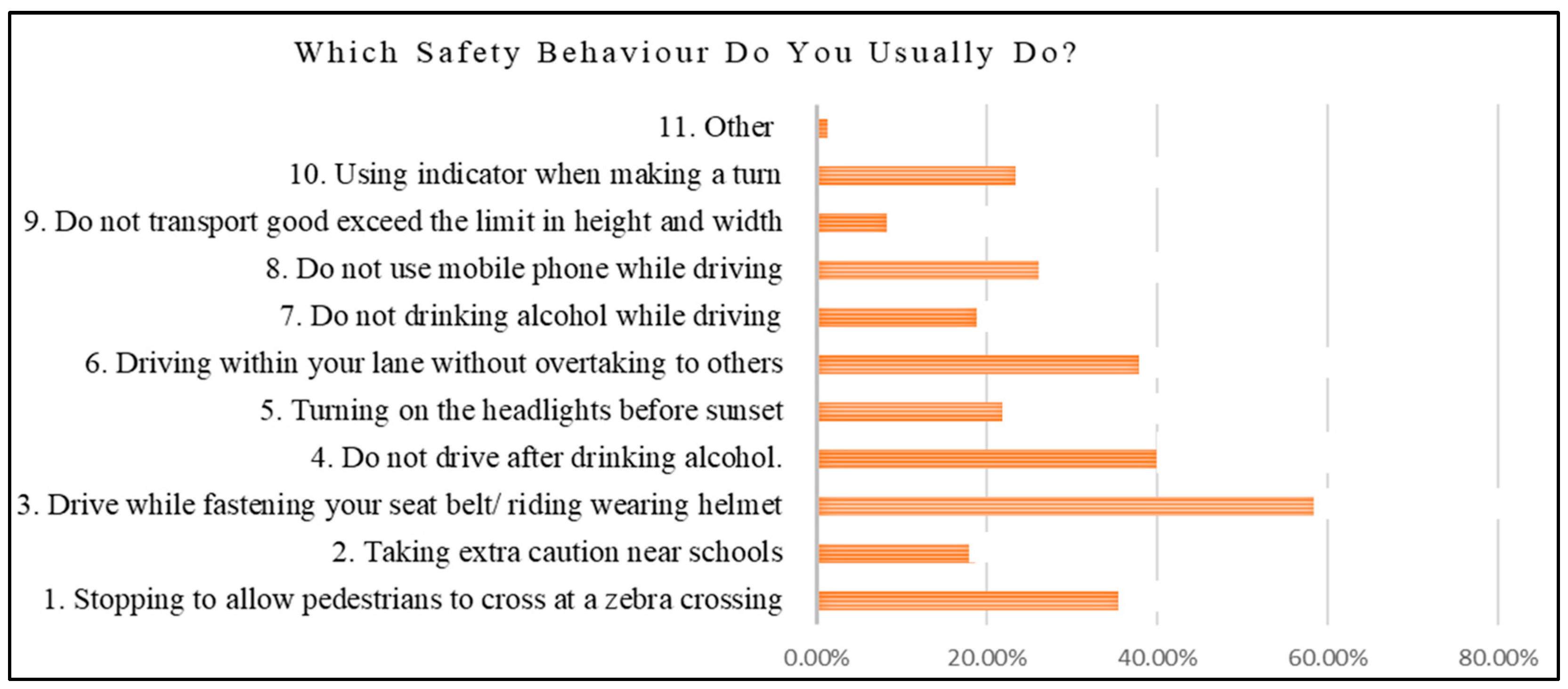

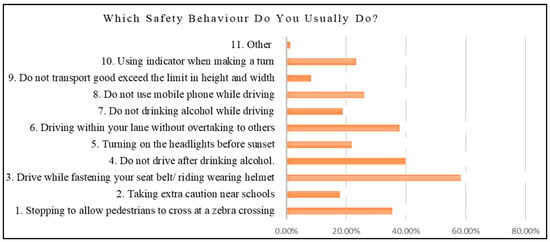

The top three traffic safety issues according to respondents’ opinions are “Driving/riding exceeding the maximum limit speed”, “Do not follow the traffic signal or police’s instruction”, and “overtaking other lanes”. For the question asking about the safety behaviours (Figure 3) that people usually follow, most answers corresponded to “Drive while fastening your seat belt/riding wearing helmet”.

Figure 3.

Safety precautions that people take.

Regarding issues related to traffic signals, most people would choose to ignore traffic signals at a frequency of one to two times a year. The reason for this violation is mostly because they are in a hurry. Furthermore, approximately 60% of the respondents suggested that the two places where collisions normally occur are intersections or roundabouts without traffic signals or traffic police and sharp-curved roads. In addition, when asked about the main reason behind traffic collisions, most referred to careless or inattentive driving/riding behaviours, such as using alcohol, using cell phones while driving/riding, and unnecessary overtaking by other vehicles.

Given the measures for tackling the remaining road traffic collision problems (Figure 4), the larger part of respondents think that the government should raise the fine for any drivers/riders that break traffic rules or regulations. Another popular opinion is that more education on road safety should be given.

Figure 4.

Measures for reducing or avoiding traffic collisions.

4.1.2. Variable Correlation

Correlation factors act as a measurement of how closely variables are related to others. Among various methods, the most popular method for determining the correlation is the Pearson correlation for normally distributed data, which gives a linear relationship between two variables [37]. Because the dataset is not normally distributed, Spearman’s coefficient was chosen to measure the direction of association between two variables. In addition, Spearman’s coefficient is applicable to both continuous and discrete ordinal variables [38]. The correlation analysis of socio-demographic variables is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Correlation table of socio-demographic variables.

The relationship with a correlation at the 99% confidence level with a significance value less than 0.01 can be considered strong due to hypothesis testing. However, values which are less than 0.4 indicate weak correlations. The results show that most correlations are significant at the 0.01 level, whereas others are at the 0.05 level. Thus, the correlation between socio-demographic variables is relatively strong.

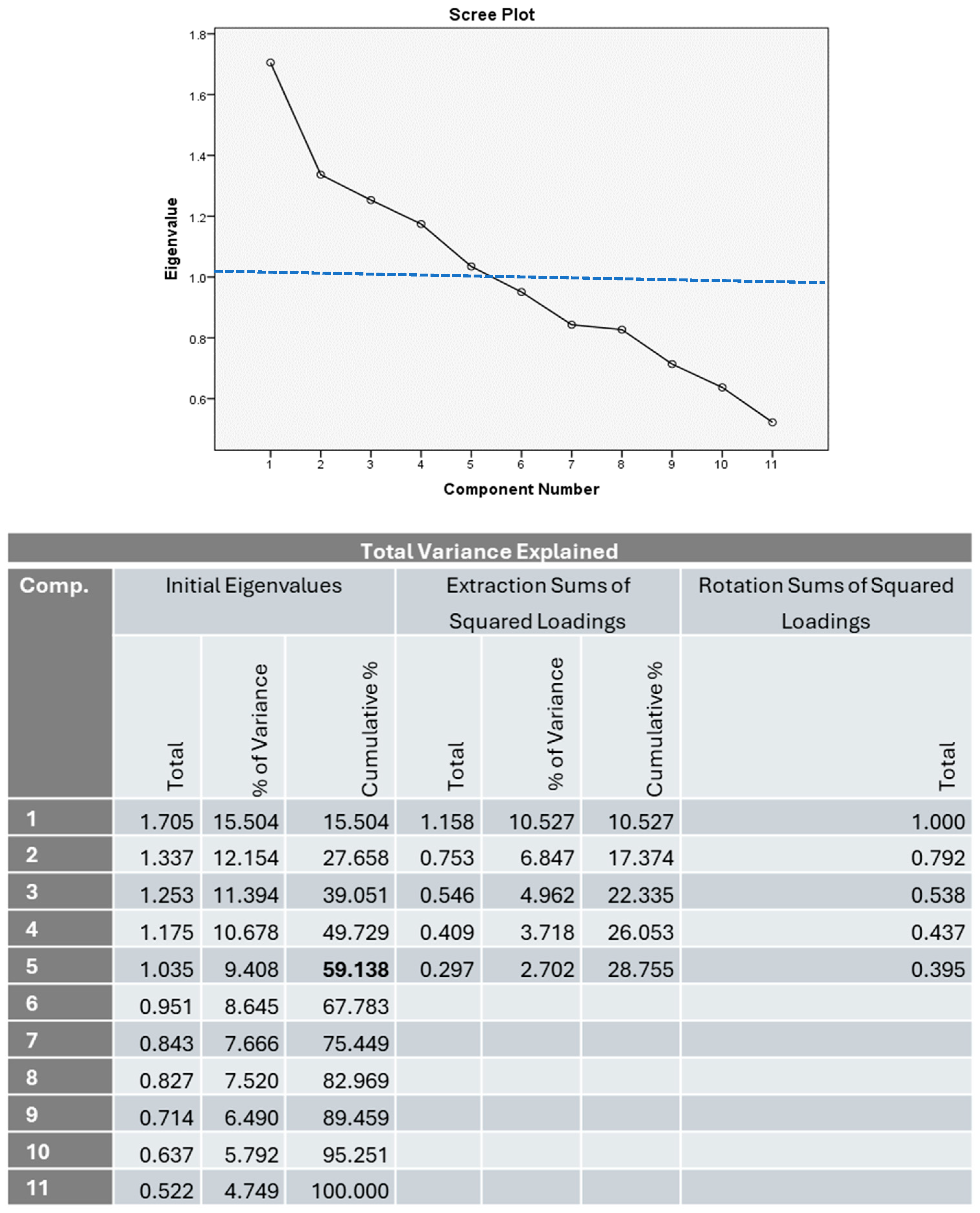

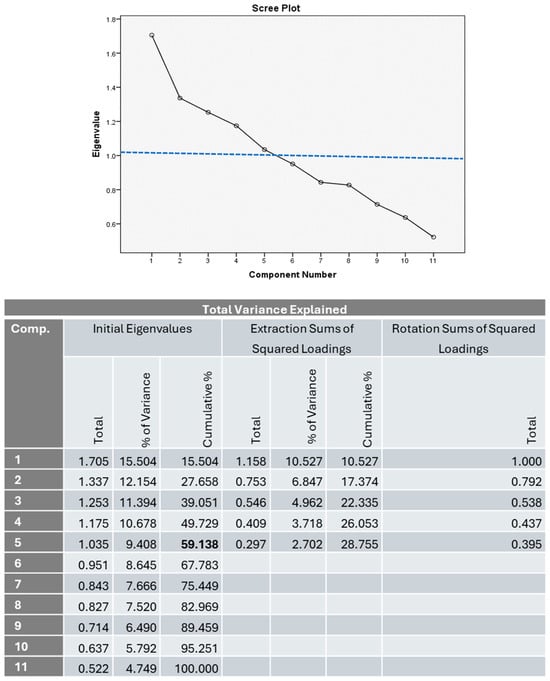

4.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

Exploratory factor analysis was used to reduce dimensions based on underlying factors or so-called “factors”. By conducting FA, representative clusters can be generated [39]. There are some common extraction methods such as Principal Axis Factoring, least squares, alpha factoring, maximum likelihood, Principal Component Analysis, generalised least squares, etc. However, previous research has demonstrated that Principal Axis Factoring (PAF) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) are the two most popular methods for data factoring [40]. Thus, these two methods were selected as they are suitable for this study. Factor analysis identifies the categories of variables that share common variance. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was used to group variables by identifying the highest factor loading value for each element. However, it was necessary to further use a rotation method to avoid ambiguity during the classification process and provide a clearer differentiation for the aim of dividing variables into groups of similar components. As for oblique rotations, Promax rotation is more advantageous in terms of its simplicity and velocity [41]. Even though Varimax is the most popular technique used in factor analysis, this study employed Promax rotation since it was suggested to use this rotation technique when the factor is larger than 3.2 [42].

Principal Axis Factoring (PAF)

The first step of factor analysis was PAF, which was used to evaluate and identify a variable found to have a significant impact on the observed variables. PAF was crucial to detect any relationships that might exist among perception variables. This research includes 393 respondents, which was considered a good sample size for PAF, as per [43]. The adequacy of sampling was assessed using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure and Bartlett’s test [44]. KMO values between 0.60 and 0.69 fall within the “mediocre” but acceptable range, and Hutcheson et al. [45] confirmed that values above 0.60 are suitable for factor analysis in applied social research. Moderate correlations are common in social science data because human attitudes and behaviour are inherently complex, multidimensional, and measured with some degree of error [46,47]. Therefore, a KMO value of 0.60 was considered acceptable and typical in behavioural and perception-based studies. In this study, a KMO value of 0.622, as shown in Table 5, was sufficient for the PAF and PCA procedures.

Table 5.

KMO and Bartlett’s test.

The eigenvalue indicates the quality score. Only components with high eigenvalues are likely to represent a real underlying factor. Based on the Kaiser criterion and the scree plot [48], the number of factors extracted was decided. All components with eigenvalues below 1.0 should be removed [49]. Currently, from the output, 11 variables seem to measure five underlying factors, and these five factors adequately represent the dataset. The scree plot was used to graph the eigenvalue against the factor number and can also be extracted from PAF (Figure 5). From the sixth factor on, the eigenvalue is smaller than one, then keeps decreasing moderately. In conceptual and behavioural terms, each factor shown in the scree plot represents an underlying construct that explains the shared variance among related variables.

Figure 5.

Scree plot and eigenvalues extracted in PAF (similarly to PCA).

The five components extracted had eigenvalues larger than 1 and explained 59.14% of the total variance (Figure 5). Thus, the factors in the scree plot represent broad conceptual themes that the variables in the dataset naturally cluster around.

A factor transformation matrix was also extracted from the model and is shown in Table 6 below:

Table 6.

Factor transformation matrix in PAF.

Since some absolute values exceeded 0.32, Promax rotation was chosen over Varimax, as recommended by [42]. Although Promax rotation is based on Varimax by using the rotated matrix from Varimax, it typically provides a more accurate reflection of the underlying structure [50]. Table 7 gives the pattern matrix in PAF. For the interpretation of the factor structure, only loadings greater than 0.30 were considered meaningful. This threshold is widely recommended in social and behavioural science research because loadings at or above 0.30 indicate the minimum acceptable level of association between an item and the underlying factor [44]. Loadings below this threshold were not interpreted and are shown in non-bold text to clearly distinguish weaker associations. Presenting all loadings, including those near zero, is standard practice when reporting the results from exploratory factor analysis [51], as it ensures transparency and helps identify items that do not meaningfully contribute to any factor.

Table 7.

Pattern matrix in PAF.

Since the factor loading was rather low in PAF (Table 7), the model was run again in PCA considering Promax as the rotation method.

4.3. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

Exploratory factor analysis was used to reduce dimensions. Previous research has demonstrated that Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a popular method for dimension reduction [33,52]. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is used to group variables by identifying the highest component loading value for each element. However, it is necessary to further use a rotation method to avoid ambiguity during the classification process and provide a clearer differentiation for the aim of dividing variables into groups of similar components. Promax was selected for component rotation since it was likely that there is a correlation between components that explain drivers’ perception towards road safety [26]. Component loading values between 0.3 and 0.4 were acceptable, even though it was preferred to have values greater than 0.5 [44].

Results of PCA

In PCA extraction, Promax rotation converged in six interactions and five components. Table 8 shows the output from PCA with component loadings.

Table 8.

Rotated component matrix in PCA.

In this study, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) produced higher loadings than Principal Axis Factoring (PAF). This outcome was expected because PCA is based on total variance, whereas PAF relies only on common variance [53]. PCA is therefore particularly useful when research aims to simplify complex datasets and generate composite components for subsequent analysis. Consequently, the PCA results were used to classify variables into groups based on the highest perception-related loadings associated with each extracted component.

As shown in Table 9, five components were identified: non-compliance with traffic regulations, aggressive driving behaviour, traffic signal issues, road quality in infrastructure and facilities, and actions and measures for prevention. To assess the internal consistency of variables within each group, a reliability test was conducted using Cronbach’s alpha. A higher Cronbach’s alpha (α) indicates a stronger correlation among items. This approach ensures the components are both meaningful and reliable, supporting the analysis of the identified groups. According to Taber [54], α values have greater variation, and the values need to be interpreted carefully. Components 1–4 have reasonable α values. The low α value related to Component 5 may be attributed to the -ve and +ve signs of the statements belonging to this component.

Table 9.

Results of PCA.

Component 1, observing the breaking of traffic regulations, emerged as a key aspect of respondents’ perceptions. This includes instances where road users ignore traffic or police instructions, exceeding speed limits, or both. Such behaviour, observed objectively, highlights a significant traffic safety issue, like challenges in Thailand, where speeding is a major concern [2]. In Vietnam, this issue may stem from low enforcement levels, particularly in Hanoi. Strengthening traffic regulation enforcement is crucial, alongside raising fines and penalties for aggressive actions, to enhance compliance and improve road safety.

Aggressive driving behaviours (Component 2), including unnecessary overtaking by other vehicles and careless or inattentive driving/riding, are another important factor in road user attitudes toward road safety. The situation of sudden unnecessary overtaking by other vehicles often causes incidents for people who are moving on the street. This leads to a high potential for minor collisions. In addition, careless or inattentive driving is another factor, which can be defined as a situation when the driver/rider is distracted or not fully concentrated on driving/riding, for example, if they are consuming alcohol, using a cell phone, or speaking to another person while driving/riding.

Component 3, regarding traffic signal issues, can be explained by the increasing number of cases violating traffic signals in Hanoi. There are numerous reasons for this action, but most road users justify this as an unexpected situation caused by their hurrying. However, the action of disobeying traffic signals happens because road users do not know either the potential of being involved in a crash or how to drive safely in this situation. Therefore, the recommendation in this circumstance is to provide traffic safety education to everyone to enhance their knowledge about dangerous situations.

Road quality and infrastructure (Component 4) are related to the places where collisions normally occur in Hanoi. This component relates to traffic lights, road signage, lane markings, design geometry, and other characteristics of the road. Based on respondents’ answers, the two places that were found to be the most associated with collisions were intersections or roundabouts without traffic signals or traffic police and sharp-curved roads. This is consistent with the findings of [25], which showed that there is a relationship between accident types and road infrastructure characteristics and the potential for the occurrence of traffic collisions. This finding suggests that it is necessary to provide adequate facilities and traffic police, as well as improving road quality, to reduce the number of collisions.

4.4. Cluster Analysis

Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) and Two-step Clustering Analysis (TCA) were employed to allocate respondents into clusters based on their socio-demographic characteristics.

4.4.1. Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA)

MCA is one of the statistical approaches used to determine, represent, and model basic structures in a dataset, especially for categorical data [33,55]. The main application of MCA in this research was to identify the interrelationships between categorical variables by putting variables into continuous data based on their coordinates on a two-dimensional graph.

The numbers that variables yield for each dimension were considered and evaluated regarding whether they might cause any effect or not. Furthermore, MCA was used to calculate the correlation between socio-demographic variables, giving an insight into the relationship among these variables in this study. For this purpose, socio-demographic variables (living district, age, gender, monthly self-income, occupation, highest qualification, driving mode, driving frequency, traffic safety education) were selected to classify transport users with similar characteristics.

- (a)

- Cronbach’s alpha

Peterson [56] indicated that an acceptable alpha range is from 0.5 for a preliminary analysis to 0.9 for applied research [57,58]. The higher the inter-correlation among the scale items, the greater the reliability of the scale, and this can be supported by a high value of Cronbach’s alpha. The possible reasons that lead to a small value here include a limited number of questions and weak relationships between them [59,60].

Table 10 shows a model summary, and the MCA method yields Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.829 for dimension 1 and 0.75 for dimension 2. Thus, the mean Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is 0.794, which is close to a high satisfactory level of 0.8.

Table 10.

Model summary in MCA.

- (b)

- Discrimination measures

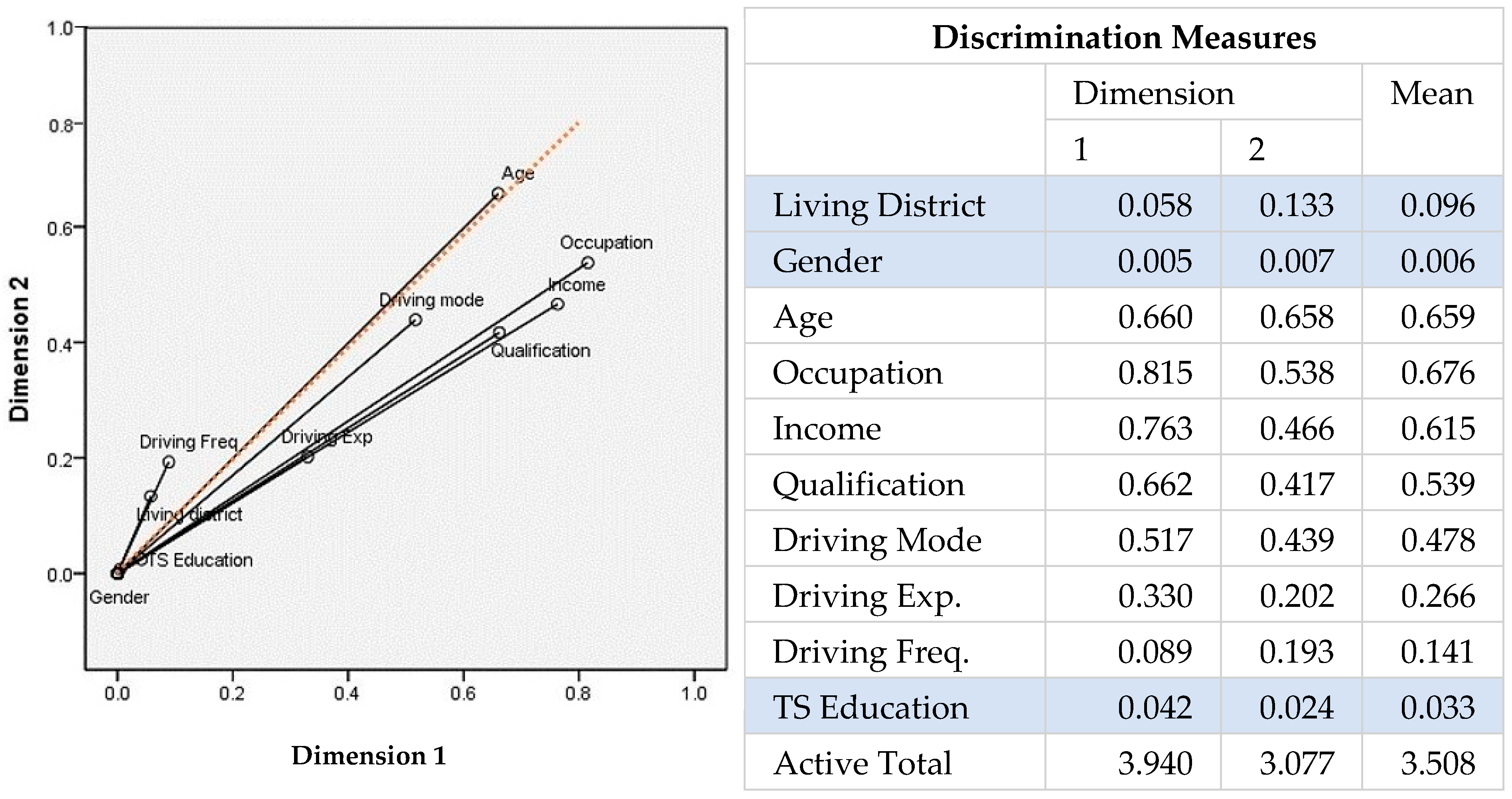

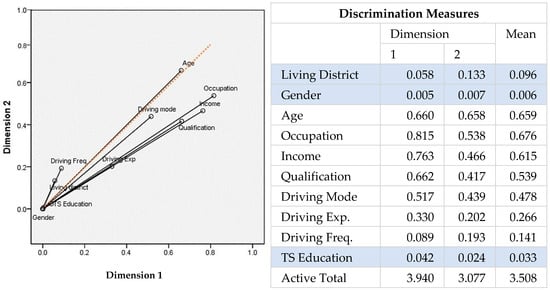

The discrimination measures extracted from MCA are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Discrimination measures (attempt 1).

The values of Living District, Gender, and TS Education were rather low, so they might not have a significant impact. Thus, after rerunning the discrimination measurement without these variables, the following results were obtained (Figure 7):

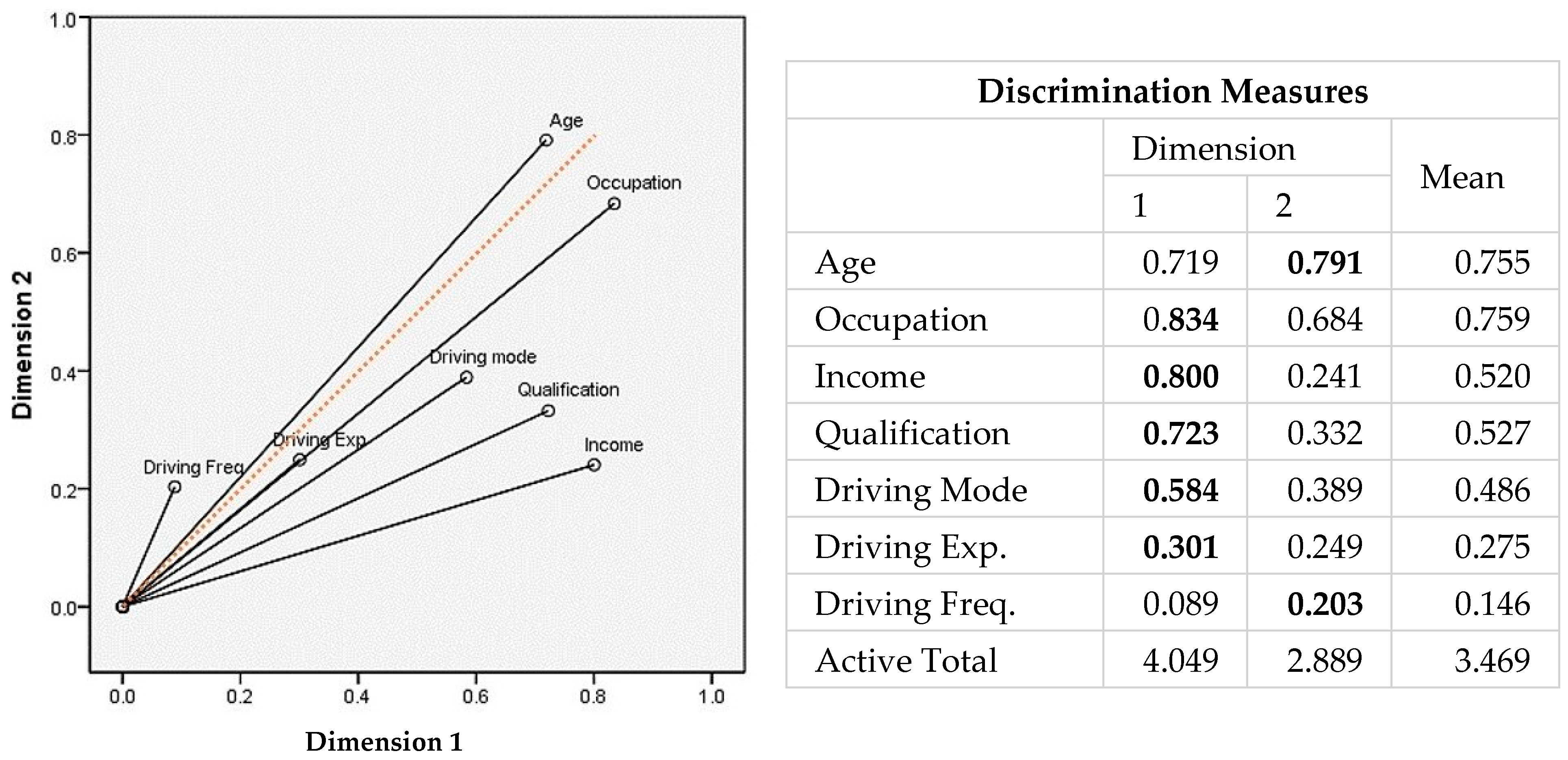

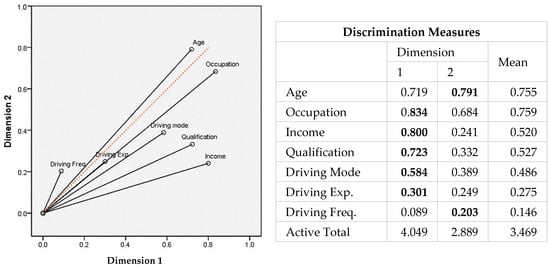

Figure 7.

Discrimination measures (attempt 2).

The first dimension contains “Occupation”, “Income”, “Qualification”, “Driving Mode”, and “Driving Experience”. The second dimension includes “Age” and “Driving Frequency”. Two-step cluster analysis was then undertaken to group drivers with similar socio-demographic characteristics together with object scores from MCA and the number of clusters determined by hierarchical clustering. The identification of the number of clusters was a step forward in this study and was conducted before carrying out two-step cluster analysis.

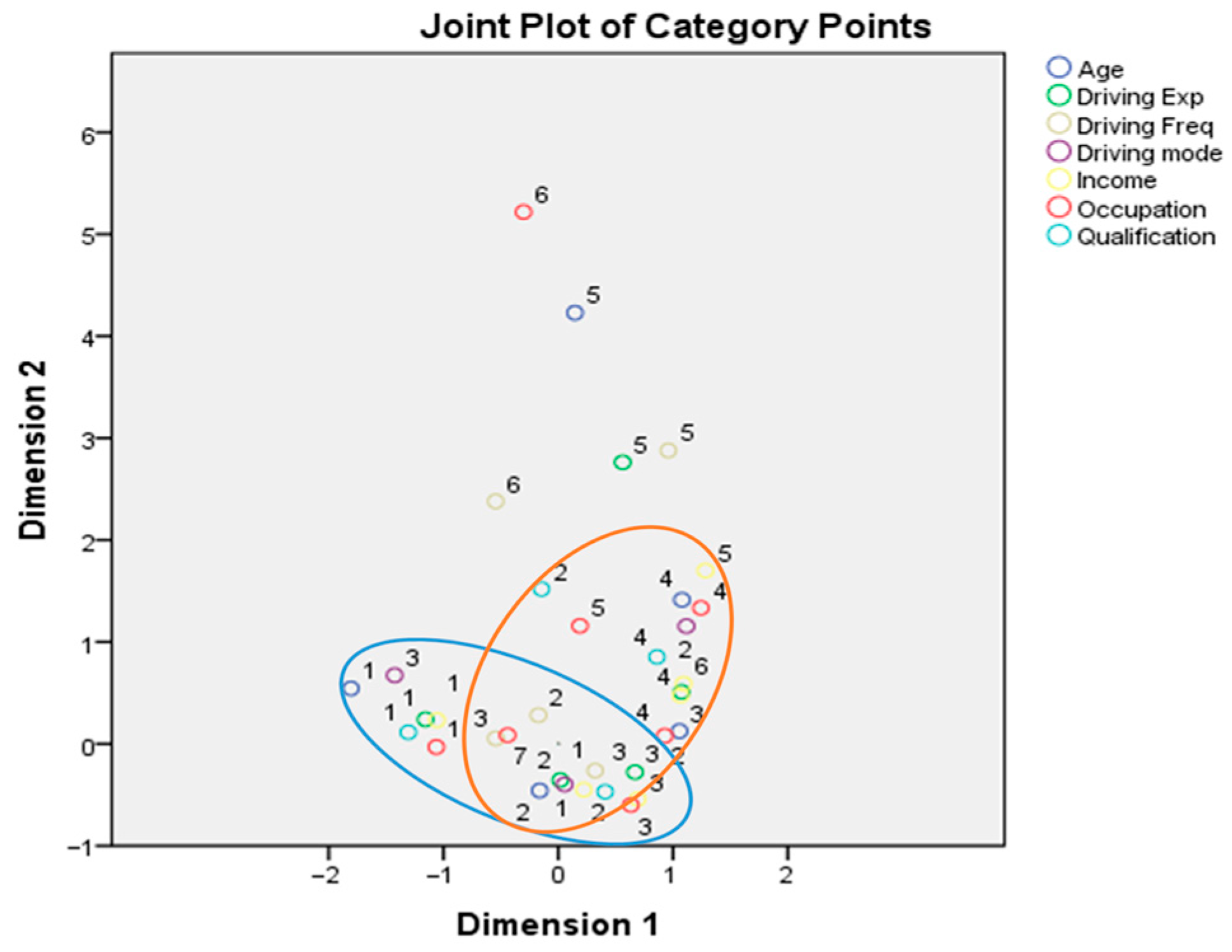

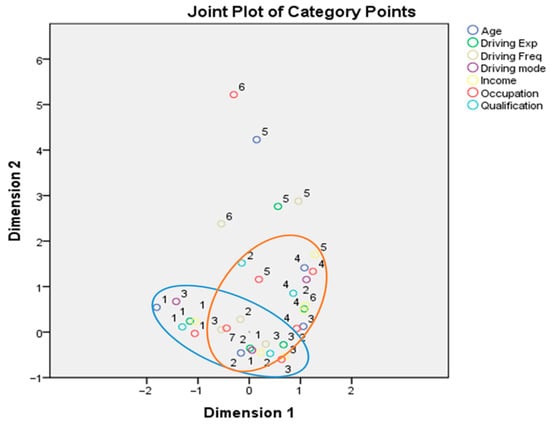

A joint plot (Figure 8) of the categories for each variable illustrates the two dimensions of “Socio-demographic variables”. From the result and joint plot, the first dimension includes “Age” and “Driving Frequency”, and the second dimension contains “Occupation”, “Income”, “Qualification”, “Driving Mode”, and “Driving Experience”. The results indicated that “Age”, “Occupation”, “Income”, and “Qualification” will have a greater effect than the other two variables.

Figure 8.

Joint plot of category points.

4.4.2. Two-Step Cluster Analysis (TCA)

Cluster analysis is a multivariate statistical technique for determining the homogenous groups of objects or cases or observations dependent on their characteristics [61]. It is widely used for identifying patterns in a dataset and one of the most essential methods for extracting useful information in a large amount of the dataset since it segregates distinctness between groups into levels. This can contribute to obtaining a more valuable understanding of the dataset [62]. The clustering technique is increasingly used in scientific research to determine heterogeneity among road users. By identifying sub-groups, it becomes simpler to analyse and reveal any relationships among the sample within and between groups.

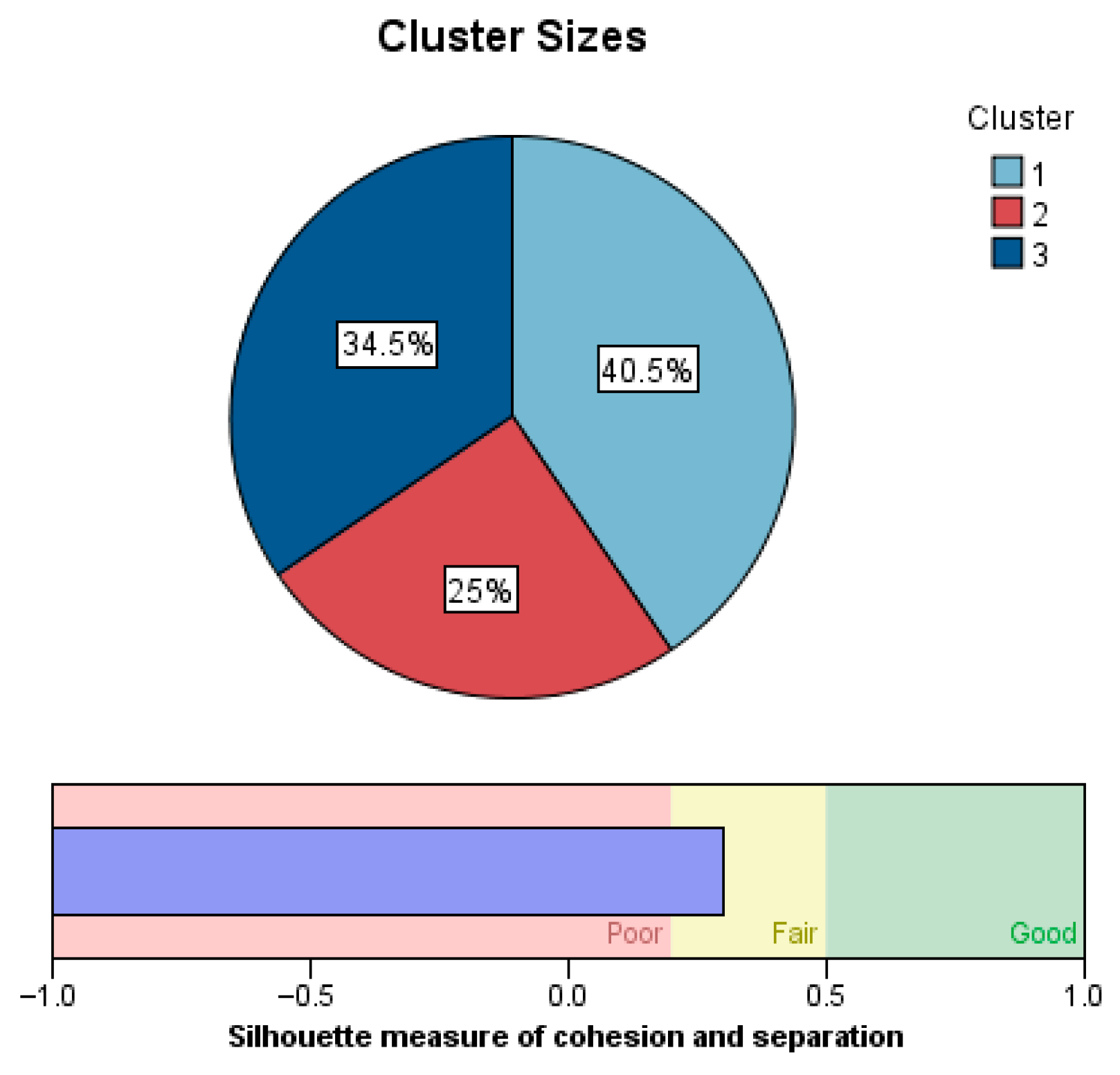

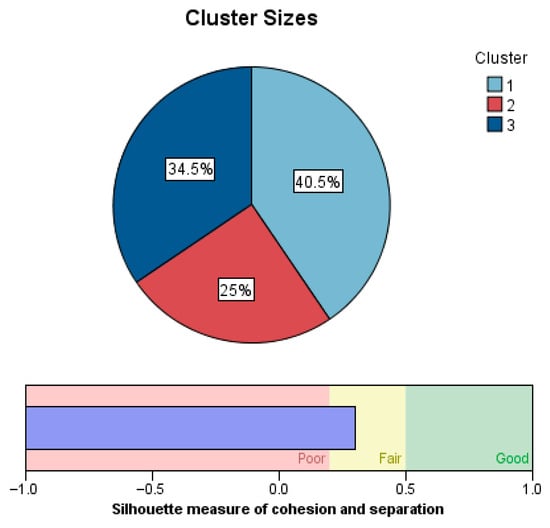

Two-step clustering was chosen for this research because of two main reasons. The first reason was that two-step cluster analysis is a statistical approach that can automatically classify similar clusters of people or objects within a dataset [63]. The second reason was that its accuracy and reliability are superior to those of other traditional clustering methods such as the technique of the mean clustering algorithm [64]. In accordance with the study of Depaire et al. [65], the clusters were analysed and named based on their variable distributions. Then, the most crucial categories within each cluster for each variable were identified, using the highest conditional probability obtained for a determined category of a variable given its membership to a specific cluster. Thus, TCA was chosen to define how the categories of each variable distribute across clusters. As shown in Figure 9, three distinct clusters were identified among respondents. The pro-portions and qualities of these cluster groups are presented below.

Figure 9.

Proportion of cluster groups.

Three clusters were identified, and the details of the three clusters are shown in Table 11.

Table 11.

Cluster characteristics for all respondents aggregated.

From Table 11, variables with the highest frequency or the highest proportion were selected, and the classifications of each cluster are given in Table 12:

Table 12.

Classification of clusters.

Cluster 1 (Young Adult in Employment Riding Motorcycles) was dominated by young adults who use motorbikes as the mode for their daily commute and have 1–5 years of riding experience. They have already graduated from college and are privately employed with an average monthly income of VND 5 to 10 million.

Cluster 2 (Young Adult in Education Riding Motorcycles) was similar to Cluster 1 as it also comprises predominantly young adult motorcyclists who ride daily and have 1–5 years’ experience in riding. The differences are that they are mostly still studying in college with a wage of less than VND 5 million per month.

Cluster 3 (Mature Adult in Employment Driving Cars) is represented by mature adult drivers using cars as their daily transport mode and with relatively long experience in commuting from 5 to 10 years. They have bachelor’s degrees and currently work in the public domain and earn VND 15–30 million a month.

4.5. Multinomial Logistic Regression (MLR)

MLR was undertaken to explore the relationship between three clusters obtained from clustering analysis and five components obtained from factoring analysis. Because the characteristics between Cluster 1 (Young Adult in Employment Riding Motorcycles) and Cluster 2 (Young Adult in Education Riding Motorcycles) are quite similar, Cluster 1 and Cluster 3 were considered as reference categories for the MLR model. The R-Square values were relatively small for all methods (Cox and Snell: 0.131; Nagelkerke: 0.148; McFadden: 0.065). However, as shown in Table 13, with a value of p lower than 0.05, the model was statistically significant and acceptable.

Table 13.

Likelihood ratio test.

Table 14 shows the results of the MLR for Model 1. It benchmarks Cluster 1 (young adult in employment riding motorcycles) as a reference category and yields a better output with more significant parameters at either the 95% or 90% level of significance.

Table 14.

Model 1—results of MLR (Cluster 1 as reference category).

The MLR results presented in Table 14 show that, relative to Cluster 1 (young adults in employment riding motorcycles), respondents in Cluster 2 (young adults in education riding motorcycles) perceived “traffic signal issues” as having a significant influence on road safety in Hanoi. In contrast, Cluster 2 respondents did not view “aggressive driving behaviour” as a significant safety concern.

Additionally, when compared with Cluster 1, respondents in Cluster 3 did not recognise the importance of “non-compliance with traffic regulations” or “aggressive driving behaviour” in improving road safety in Hanoi. However, Cluster 3 did acknowledge the significance of “traffic signal issues” and the “quality of infrastructure and facilities” as key contributors to enhancing road safety in the city. This outcome can be explained by the increasing number of cases involving violations of traffic signals in Hanoi. Although this issue is related to the first component, it reflects a more subjective form of non-compliance, as it involves road users who knowingly fail to observe traffic lights. While there may be various reasons for this behaviour, many road users justify it as an unavoidable reaction to being in a hurry. However, such actions also occur because drivers often lack an awareness of the potential crash risks associated with disobeying traffic signals or do not fully understand how to respond safely in these situations. Therefore, a key recommendation is to strengthen traffic safety education and enhance public knowledge regarding hazardous situations, particularly the dangers associated with violating traffic signals.

The quality of infrastructure and facilities encompasses that of traffic lights, road signage, lane markings, road geometry, and other design elements. Respondents identified intersections or roundabouts lacking traffic signals or police presence and sharp-curved roads as the most frequent collision sites. These findings align with previous research by Gomes [66] and Kaygisiz and Yildiz [67], which established a strong link between inadequate road infrastructure and the likelihood of traffic accidents. To mitigate collisions, it is crucial to enhance road quality, provide sufficient traffic management facilities, and ensure the presence of traffic police at critical locations. Ahmed [68] also confirmed that roadway and roadside parameters were significantly linked to road crash occurrence and severity. Car drivers (Cluster 3) do not perceive non-compliance with traffic regulations (Component 1) as a safety concern.

Table 15 shows the results, taking Cluster 3 as a reference.

Table 15.

Model 2—results of MLR (Cluster 3 as reference category).

According to the results presented in Table 15, and relative to Cluster 3 (mature adults in employment driving cars), respondents in Cluster 1 (young adults in employment riding motorcycles) perceived “traffic signal issues” and the “quality of infrastructure and facilities” as being less likely to influence road safety. In contrast, they considered “non-compliance with traffic regulations” and “aggressive driving behaviour” to have a significant impact on road safety in Hanoi. Similarly, respondents in Cluster 2 (young adults in education riding motorcycles) perceived “non-compliance with traffic regulations” as an important consideration in the road safety agenda in Hanoi.

4.6. Discussion on Relationship Between Clusters and Factors

The results of the MLR analysis clearly indicate that “non-compliance with traffic regulations” is perceived as the most significant factor influencing road safety across all three clusters. This reflects situations in which travellers frequently observe other road users failing to follow traffic rules or police instructions, exceeding speed limits, or engaging in both behaviours simultaneously. Such findings align with the situation reported in Thailand, where speed limit violations are also recognised as a critical safety concern that requires targeted intervention [2]. The prominence of this issue in the Hanoi context may be linked to the relatively low level of traffic law enforcement, as suggested by the high number of recorded violations in the National Police Department’s online data. Strengthening the enforcement of traffic regulations is therefore likely to be particularly impactful for road users in Hanoi. Additionally, increasing fines and penalties for aggressive or non-compliant behaviour may serve as an effective complementary measure to improve overall road safety.

Aggressive driving behaviours including unnecessary overtaking by other vehicles and careless or inattentive driving or riding represent another important dimension of road user perceptions of safety, as all three clusters showed associations with this component. Sudden and unnecessary overtaking commonly creates unexpected conflicts for road users, increasing the likelihood of minor collisions. Careless or inattentive driving is equally critical, referring to situations where drivers or riders are distracted or not fully focused, as seen in behaviours such as consuming alcohol, using mobile phones, or engaging in conversations while operating a vehicle. Drunk driving is a major contributor to road crashes, with similar patterns observed in Japan [3]. Nishitani’s study recommends strengthening public education on alcohol consumption, conducting more frequent random blood alcohol tests, and strictly enforcing penalties for offenders. Beyond alcohol use, mobile phone distraction remains a key concern for policymakers worldwide [69], and it is especially prevalent among younger road users in Vietnam [70]. Mobile phone use reduces situational awareness through cognitive distraction, and while existing research has focused predominantly on car drivers [71], the risk is substantially higher for motorcyclists, who often ride with one hand, thereby increasing crash likelihood. To address these issues, targeted awareness campaigns should emphasise the dangers of alcohol use and mobile phone distraction while driving or riding.

Issues related to traffic signals are also found to be important among the three cluster groups. This can be explained by the increasing number of cases of violating traffic signals in Hanoi. This is also related to the first component, but this is a subjective breaking of traffic regulations as the respondent is the one who does not observe traffic lights. There are numerous reasons for this action, but most road users justify this as an unexpected situation caused by their hurrying. However, the action of disobeying traffic signals happens because road users do not know either the potential of being involved in a crash or how to drive safely in this situation. Therefore, the recommendation in this circumstance is to provide traffic safety education to everyone to enhance their knowledge about dangerous situations.

Road quality, including that of infrastructure and related facilities, is a significant component influencing collision hotspots in Hanoi, particularly for Clusters 1 and 3. This component encompasses the quality of traffic lights, road signage, lane markings, road geometry, and other design elements. Respondents identified intersections or roundabouts lacking traffic signals or police presence and sharp-curved roads as the most frequent collision sites. These findings align with previous research [66], which established a strong link between inadequate road infrastructure and the likelihood of traffic accidents. To mitigate collisions, it is crucial to enhance road quality, provide sufficient traffic management facilities, and ensure the presence of traffic police at critical locations.

5. Conclusions

This study focuses mainly on the awareness of drivers and motorcycle riders and aspects that are associated with their perception regarding road safety issues. This research considered a case study in Hanoi, Vietnam. The respondents who filled out the questionnaire survey came from a variety of parts of Hanoi and have several years of driving and/or riding experience, so they have different knowledge and backgrounds and various points of view on traffic safety issues. They are either students or employees, the two groups that are the main daily commuters. As per the results, the most popular mode of transport used and owned is motorcycles. Additionally, most responders pointed out that they have at least two motorbikes in their house. The number of respondents that have not had any road safety education at school remains relatively high. However, regarding the traffic safety issue in Hanoi, most people think that it is important and a cause for concern. According to most respondents’ opinions, traffic safety education should be provided for every rider and driver in Hanoi. This is followed by the opinion that it is the most important to provide this education for motorcyclists, which, as has been stated, is the largest group of road users in Hanoi.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA), two-step cluster analysis (TCA), and Multinomial Logistic Regression (MLR) were employed as analytical methods. By performing PCA, the key components related to road safety issues based on respondents’ perceptions were revealed: non-compliance with traffic regulations, aggressive driving behaviour, traffic signal issues, quality in roads and infrastructure and facilities, and preventive measures.

MCA and TCA classified 393 respondents into three socio-demographic clusters: (1) young adults in employment riding motorcycles, (2) young adults in education riding motorcycles, and (3) mature adults in employment driving cars. The relationships between components and clusters were analysed using MLR. These findings provide valuable insights into road safety perceptions and challenges from users’ perspectives.

Overall, the results of this study provide significant insight into road users’ awareness of traffic safety in Hanoi, which is presented as a case in a developing country. To summarise, after considering the analysis results and the open-ended questions, the level of public awareness of road safety in Hanoi lies between low and moderate. The factors above still present a gap in the acknowledgement of how to enhance the safety of road users in Hanoi. Thus, from the results of this research, there are several solutions that were recommended to improve the current situation. Focusing on the violation of traffic regulations could be considered as one of the important tasks that should contribute to improving road safety issues. Thus, actions from the government should be employed to raise the community awareness of the importance of complying with traffic policies and regulations. Additionally, most respondents emphasised that drivers and riders should be the primary focus of safety strategies, but education and public awareness campaigns targeting all road users are essential to reducing traffic collisions and improving safety. Furthermore, improved road conditions and facilities and transport user behaviour in signalised junctions are important to enhance road safety in Hanoi.

6. Recommendation for Future Research

Further studies are necessary to fulfil the limitations of this research. Because the survey in this research was conducted based on the knowledge and perceptions of road users about components related to road safety in the central districts of Hanoi, it is necessary to widen the case study area to the surrounding areas of central business districts. In addition to this, the human component plays an important role in road safety issues, so it is necessary to undertake a study to understand significant components and solutions to raise awareness for other types of road users including pedestrians, cyclists, and bus passengers. The way data is collected should also be improved to achieve better accuracy. When it comes to future research in the same field of study, research should be conducted in other cities in developing or developed countries. As explained by Cavus et al. [72], using multiple datasets, rather than relying on a single cross-sectional dataset, will enhance the credibility of the study. When it comes to future research in the same field of studies, the research would be applied in other cities in developing or developed countries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, N.T.H.H. and D.D.; methodology, N.T.H.H. and D.D.; software, N.T.H.H.; validation, N.T.H.H.; formal analysis, N.T.H.H.; investigation, N.T.H.H.; resources, N.T.H.H.; data curation, N.T.H.H.; writing—original draft preparation, N.T.H.H., S.A. and D.D.; writing—review and editing, N.T.H.H., S.A., S.B., P.W. and D.D.; supervision, D.D.; project administration, N.T.H.H. and D.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Newcastle University (Ref. 10720/2018 and 7 February 2019) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TCA | Two-Step Cluster Analysis |

| ADB | Asian Development Bank |

| ASEAN | Association of Southeast Asian Nations |

| JICA | Japan International Cooperation Agency |

| KMO | Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin |

| MCA | Multiple Correspondence Analysis |

| MLR | Multinomial Logistic Regression |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

References

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Road Safety 2015; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kanitpong, K.; Jiwattanakulpaisarn, P.; Yaktawong, W. Speed management strategies and drivers’ attitudes in Thailand. IATSS Res. 2013, 37, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishitani, Y. Alcohol and traffic accidents in Japan. IATSS Res. 2019, 43, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartt, A.T.; Shabanova, V.I.; Leaf, W.A. Driving experience, crashes and traffic citations of teenage beginning drivers. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2003, 35, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolison, J.J.; Hanoch, Y.; Wood, S.; Liu, P.J. Risk-taking differences across the adult life span: A question of age and domain. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2014, 69, 870–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petridou, E.; Moustaki, M. Human factors in the causation of road traffic crashes. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2000, 16, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asian Transport Observatory. Viet Nam Road Safety Profile 2025; Asian Transport Observatory: Quezon, Philippines, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Road Safety 2018; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Yau, K.K.; Chen, G. Risk factors associated with traffic violations and accident severity in China. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2011, 59, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedagama, P.; Dissanayake, D. Analysing Motorcycle Injuries on Arterial Roads in Bali using a Multinomial Logit Model. In Proceedings of the Eastern Asia Society for Transportation Studies, Surabaya, Indonesia, 16–19 November 2009; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Asian Development Bank. Road Safety Action Plan—Implementation of Sustainable Transport Initiative: Mainstreaming Road Safety in ADB Operations; Asian Development Bank: Manila, Philippines, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mounts, A.; Nolen, L.D.; Sugerman, D. Changes in motorcycle-related injuries and deaths after mandatory motorcycle helmet law in a district of Vietnam. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2018, 19, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.C.; Ivers, R.; Norton, R.; Boufous, S.; Blows, S.; Lo, S.K. Helmets for preventing injury in motorcycle riders. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2008, 1, CD004333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, D.; Wedagama, P. Pedestrian safety. In Elgar Encyclopedia of Transport and Society; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanan, T.; Sjafruddin, A.; Idris, M. The characteristics of road crashes on Indonesian national roads based on integrated road safety management system data. Period. Polytech. Transp. Eng. 2025, 53, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, S.; Heo, T.-Y.; Lee, D. Identifying the roadway infrastructure factors affecting road accidents using interpretable machine learning and data augmentation. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgün, N.; Dissanayake, D.; Thorpe, N.; Bell, M.C. Cyclist casualty severity at roundabouts: To what extent do the geometric characteristics of roundabouts play a part? J. Saf. Res. 2018, 67, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azin, B.; Ewing, R.; Yang, W.; Promy, N.S.; Kalantari, H.A.; Tabassum, N. Urban arterial lane width versus speed and crash rates: A comprehensive study of road safety. Sustainability 2025, 17, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedagama, D.M.P.; Bennett, S.; Dissanayake, D. Analyzing pedestrian perceptions towards traffic safety using discrete choice models. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2020, 10, 2394–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katanararoj, N.; Choocharukul, K.; Kunihiro, K. A comparative study of road traffic violation between Thai and Japanese teenagers. IATSS Res. 2024, 48, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, H.T.N.; Hobday, M.B. Characteristics and severity of motorcycle crashes resulting in hospitalization in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2019, 20, 732–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Hosseini, P.; Kakhani, A.; Jalayer, M.; Patel, D. Unveiling the risks of speeding behavior by investigating the dynamics of driver injury severity through advanced analytics. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohaee, N.; Bohluli, S. Nonlinear analysis of the effects of socioeconomic, demographic, and technological factors on the number of fatal traffic accidents. Safety 2024, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panumasvivat, J.; Kitro, A.; Samakarn, Y.; Pairojtanachai, K.; Sirikul, W.; Promkutkao, T.; Sapbamrer, R. Unveiling the road to safety: Understanding the factors influencing motorcycle accidents among riders in rural Chiang Mai, Thailand. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jima, D.; Sipos, T. Road geometry-related crash distribution, economic losses, and an alternative severity level analysis approach using combined parameters utilizing relative percentage share. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2025, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibenda, M.; Wedagama, D.M.P.; Dissanayake, D. Drivers’ attitudes to road safety in the Southeast Asian cities of Jakarta and Hanoi: Socio-economic and demographic characterisation by multiple correspondence analysis. Saf. Sci. 2022, 155, 105869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuri, M.G.; Isab, K.A.M.; Tahir, M.P.M. Children, youth and road environment: Road traffic accident. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 38, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manan, M.M.A.; Ho, J.S.; Arif, S.T.; Ghani, M.R.A.; Várhelyi, A. Factors associated with motorcyclists’ speed behaviour on Malaysian roads. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2017, 50, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, D.V.; Stevenson, M.R.; Ivers, R.Q. Barriers to, and factors associated with, observed motorcycle helmet use in Vietnam. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2008, 40, 1627–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trinh, T.A.; Le Tuan, P. Motorcycle helmet usage to improve road traffic safety in Vietnam. Inj. Prev. 2010, 16, A137–A138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra, T.; Wegman, F. Improving the effectiveness of road safety campaigns: Current and new practices. IATSS Res. 2011, 34, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortúzar, J.D.D.; Willumsen, L.G. Modelling Transport, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, F.; Dissanayake, D.; Bell, M.; Farrow, M. Investigating car users’ attitudes to climate change using multiple correspondence analysis. J. Transp. Geogr. 2018, 72, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, A.J.; McKnight, A.S. Young novice drivers: Careless or clueless? Accid. Anal. Prev. 2003, 35, 921–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wambulwa, W.M.; Job, R.F.S.; Turner, B.M. Guide for Road Safety Opportunities and Challenges: Low- and Middle-Income Country Profiles; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, T.P.; Dao, N.X.; Ahmad, F.M.S. A comparative study on motorcycle traffic development of Taiwan, Malaysia and Vietnam. J. East Asia Soc. Transp. Stud. 2003, 5, 179–193. [Google Scholar]

- Gogtay, N.J.; Thatte, U.M. Principles of correlation analysis. J. Assoc. Physicians India 2017, 65, 78–81. [Google Scholar]

- Khamis, H. Measures of association: How to choose? J. Diagn. Med. Sonogr. 2008, 24, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.O.; Ahtola, O.; Spector, P.E.; Mueller, C.W. Introduction to Factor Analysis: What It Is and How to Do It; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, P. An Easy Guide to Factor Analysis, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, H. Factor rotations in factor analyses. In Encyclopedia of Research Methods for the Social Sciences; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 792–795. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S.; Ullman, J.B. Using Multivariate Statistics, 5th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Comrey, A.L.; Lee, H.B. A First Course in Factor Analysis; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics; Sage: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hutcheson, G.; Sofroniou, N. The Multivariate Social Scientist: Introductory Statistics Using Generalized Linear Models; Sage: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- DeVellis, R.F. Scale Development: Theory and Applications, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ledesma, R.D.; Valero-Mora, P.; Macbeth, G. The Scree Test and the Number of Factors: A Dynamic Graphics Approach. Span. J. Psychol. 2015, 18, E11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salkind, N.J. Principal component analysis. In Encyclopedia of Research Design; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod, L.D.; Swygert, K.A.; Thissen, D. Factor analysis for items scored in two categories. In Test Scoring; Thissen, D., Wainer, H., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 189–216. [Google Scholar]

- Costello, A.B.; Osborne, J.W. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2005, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Saw, Y.Q.; Dissanayake, D.; Ali, F.; Bennett, T. Passenger satisfaction towards metro infrastructures, facilities and services. Transp. Res. Procedia 2020, 48, 3980–3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I.T.; Cadima, J. Principal component analysis: A review and recent developments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A. 2016, 374, 20150202. [Google Scholar]

- Taber, A.S. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotet, C.; Bösehans, G.; Dissanayake, D. Exploring the factors shaping attitudes and intentions towards automated buses: Empirical evidence from Northeast England. J. Transp. Geogr. 2025, 123, 104024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R.A. A meta-analysis of Cronbach’s coefficient alpha. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, J.M. What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griethuijsen, R.A.L.F.; Eijck, M.W.; Haste, H.; den Brok, P.J.; Skinner, N.C.; Mansour, N.; Gencer, A.Y.; BouJaoude, S. Global patterns in students’ views of science and interest in science. Res. Sci. Educ. 2014, 45, 581–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenthal, K.M. An Introduction to Psychological Tests and Scales, 2nd ed.; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.A.; Wichern, D.W. Applied Multivariate Statistical Analysis, 6th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mooi, E.; Sarstedt, M. Cluster Analysis. A Concise Guide to Market Research; Mooi, E., Sarstedt, M., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2011; pp. 273–324. [Google Scholar]

- Everitt, B.S.; Landau, S.; Leese, M.; Stahl, D. Cluster Analysis, 5th ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Norušis, M.J. IBM SPSS Statistics 19 Statistical Procedures Companion; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Norušis, M.J. SPSS 16.0 Advanced Statistical Procedures Companion; Prentice Hall Press: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Depaire, B.; Moussaoui, A.; Eeckhoudt, V. Profiling high-risk car drivers using cluster analysis. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2008, 40, 182–190. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, S.V. The influence of infrastructure characteristics on urban road accident occurrence. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2013, 60, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaygisiz, Ö.; Yildiz, A. Co-location analysis of pedestrian accident attributes for Ankara. Int. J. Inj. Control Saf. Promot. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I. Road infrastructure and road safety. Transp. Commun. Bull. Asia Pac. 2013, 83, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Mobile Phone Use: A Growing Problem of Driver Distraction; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gras, M.E.; Cunill, M.; Sullman, M.J.M.; Planes, M.; Aymerich, M.; Font-Mayolas, S. Mobile phone use while driving in a sample of Spanish university workers. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2007, 39, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajesh, R.; Srinath, R.; Sasikumar, R.; Subin, B. Modeling safety risk perception due to mobile phone distraction among four-wheeler drivers. IATSS Res. 2017, 41, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavus, M.; Ayan, H.; Bell, M.; Oyebamiji, O.K.; Dissanayake, D. Deep charge-fusion model: Advanced hybrid modelling for predicting electric vehicle charging patterns with socio-demographic considerations. Int. J. Transp. Sci. Technol. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.