Abstract

Given the undoubtable similarities between the dynamic behavior of the vehicular traffic flow in terms of its response to boundary condition alterations dictated in the form of obstacles, and the specific case of supersonic compressible fluid flow fields, the current manuscript addresses developing a target trajectory for the overtaking maneuver of autonomous vehicles. The path-planning is pursued in analogy to the governing principles of the supersonic compressible fluid flow fields, with the specific definition of a physically meaningful dimensionless group, namely the Traffic Mach number (MT), which grants the initial access point to the said set of fundamental equations. This practical application is a follow-up to the primarily established proof-of-concept level introduction and analysis of the more general case of collision avoidance for autonomously driven vehicles in accordance with the supersonic compressible fluid flow field, where the Traffic Mach number was first introduced. The proposed trajectory is then taken to the next block of the investigation, namely the tracking and control aspects of the maneuvering vehicle’s dynamics. The path tracking controller is designed based on sliding mode control technique and the algorithm is applied on a 7-DOF simulation model, used for validation and discussion of results. The proposed method is shown to be suitable for overtaking maneuvers of autonomous vehicles, whilst meeting the criteria for a relative velocity from the constant-velocity vehicle ahead of the road in the supersonic regime based on the defined Traffic Mach number. The results are then presented, first, in the scope of the aerodynamics field configuration and their verifications, followed by the vehicle dynamics remarks showing the practicality of the proposed method in terms of vehicle motion. It is observed that the distance corresponding to the delayed maneuver maximizes at highest velocities of the ego vehicle, consistent with the highest MT values, yet in all simulated cases, the control system of the vehicle model was capable of performing the maneuver based on the assigned trajectories through the present model.

1. Introduction

The inevitable analogy between the flow of traffic and that of fluids has triggered numerous research studies on modeling and predicting the former using the established principles of the latter. More specifically, the analogy is seen, and investigated in the current study, between the traffic flow and supersonic compressible fluid flow between traffic flow and supersonic compressible fluid flow is examined in the current study [1]. The following is a brief literature survey on the relevant works addressing this subject matter.

Bellomo et al. [2] investigated the driver behavior by providing a mathematical model based on hydrodynamics. Bonzani and Musson [3] used stochastic modeling of traffic flow with analytical and computer-aided approaches. The same ansatz was used later in Jabari and Liu [4]. In an early work, Daganzo [5] studied the second-order fluid approximations of traffic flow.

Hoogendoom et al. [6,7] addressed the pedestrian flow as a simplified form of traffic flow, with higher degrees of freedom, using continuum assumptions. Marques and Mendez [8] applied the Chapman–Enskog expansion and Grad’s moment method for modeling traffic flow in the context of kinetic theory of vehicular traffic flow, while Coscia et al. [9] used discrete velocity kinetic models.

Shi et al. [10] introduced the concept of equilibrium traffic pressure, linking the physical state representations of fluid flow and discrete traffic flow, using the Lattice Boltzmann model. Ma and Cui [11] developed statements for traffic flow density distribution, using FEM, leading to further coupling of thermodynamic/gas dynamic parameters and macroscopic behavior of traffic flow. The viscosity of traffic has been addressed as a consequence of speed variation in Li et al. [12]. This is while the mathematical theory of non-uniform gases, concerning the theory of viscosity, thermal conduction, and diffusion, was presented in Chapman and Cowling [13].

The dynamics of normal shock waves on highways as an emergent phenomenon was addressed in Richards [14]. On the same subject matter, Chen et al. [15] investigated the role of driver characteristics on the periodicity of traffic oscillations and their corresponding capacity drop. Zhang [16] introduced traffic viscosity and general insights on viscous vehicular traffic flow as a means for modeling traffic flow. Further information regarding a vast majority of relevant works on this subject matter was also gathered as a review paper by Darbha et al. [17].

Taking a distinct approach, Amini and Milani [1] address the issue of analogy between vehicular traffic flow and supersonic compressible fluid flow; however, with the modified target of trajectory planning, instead of modeling per se.

In accordance with the previously established thermodynamic state properties for the vehicular flow of traffic, Amini and Milani [1] introduce an analogous statement for the Mach number corresponding to the traffic flow. The so-called traffic Mach number considers the geometric length scale of the distance between two consecutive vehicles, a time scale they will encounter in the case of a sudden braking maneuver in the leading vehicle before reaching the same point on the road, the reflection time/delay of the driver/vehicle and friction coefficient of the tire-road contact patch, leading to the maximum braking deceleration. The resulting Mach number could then be input into compressible fluid flow equations, as the entire range and critical phases of the Mach number variation in a fluid system are shown to coincide with those of the introduced MT.

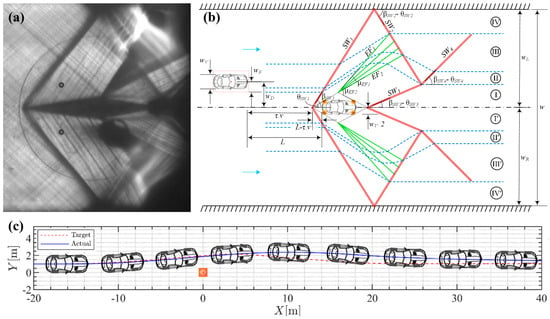

Thereafter, the specific case of a sudden stationary obstacle appearing ahead of the following vehicle has been solved, using the fundamental principles of supersonic compressible flow, leading to a path-planning algorithm for the purpose of collision avoidance. Figure 1a,b shows the accuracy and correspondence of the analogy in the actual fluid flow field and that of the vehicular traffic.

Figure 1.

Traffic and supersonic compressible flow analogies, (a) Mach number and sample flow trajectories plotted for the double wedge profile, adapted from [18], (b,c) Proposed trajectory for collision avoidance, adapted from [1].

The overtaking or obstacle avoidance maneuver in the highway scenario could be viewed as a double-lane-change maneuver in which the initiation time and the duration of staying in the overtaking lane are affected dynamically by the position and velocity of the vehicles involved. Therefore, the problem of dealing with such maneuvers may be broken down into two separate single lane-change maneuvers that need their respective path-planning and path-tracking strategies. Since the main focus of this paper is on the path-planning strategy, the tracking of the generated reference path is performed using previously proven effective methods described in the next sections. Path-planning for lane-changing has been studied from different perspectives, among which the most significant studies are reviewed here.

Shiller and Sundar [19] investigated an emergency lane-change scenario for the obstacle avoidance problem through finding the longitudinal distance threshold at which an evasive lane-change is feasible, considering vehicle dynamics. The lane-change path is constructed based on cubic B-splines, and the problem is formulated as an optimization problem over the steering and traction force as inputs to the vehicle. The vehicle model is constructed using a 3 DOF bicycle model with the rear tire being under a combined-slip condition and modeled using the Dugoff tire force model to account for the tire force limits. The optimization problem is solved with the help of inverse dynamics formulation, and the limit of the emergency lane-change maneuver is obtained as a metric to define the latest time to perform the lane-change in order to avoid a collision. Although the path is already assumed to be constructed by cubic B-splines, the time of the maneuver is investigated, which is also a part of the path-planning procedure. Note that this initiation time may be converted into a distance to the obstacle, according to the relative velocity between the preceding vehicle and the obstacle (e.g., a slower-moving vehicle).

You et al. [20] considered using polynomials for path planning due to their simplicity to work with, as well as their potential to produce a curvature-continuous path when tuned properly. They have also used a parameter space in which obstacles could be mapped, and the resulting optimized parameter set automatically ensures the obstacle avoidance objective. The longitudinal and lateral positions are assumed to be 6-degree and 5-degree polynomial functions of time, respectively. The polynomial parameters are solved through a set of constraint equations describing the initial and the final conditions, as well as keeping a certain distance from the obstacle. The use of polynomials has also been shown to be successful for emergency maneuvering in He et al. [21].

Chen et al. [22] used a piecewise quadratic Bezier curve to smooth the desired path of motion for lane-change maneuvers, due to its tangent and curvature continuity and simplicity of formulation, which is favorable for real-time implementation. The results show that the target path provides passenger comfort while satisfying the vehicle dynamics.

Cesari et al. [23] assumed the lane-change path to be constructed using the Sigmoid function, and since the driver’s lane change style was of interest, the Sigmoid function was approximated by Taylor series expansions at different sections for the calculations to have closed-form solutions.

The possibility and safety of a lane-change maneuver in terms of the surrounding traffic, i.e., the leading and trailing vehicles in the current and the target lane, has been studied in Chandru et al. [24], and the safe lane-change decision making is attributed to some imposed constraints on a model predictive controller with a simplified point-mass vehicle model. The resulting target path is set to be optimized to satisfy the safe driving zones while minimizing input requirements.

In the present research, the path-planning strategy would automatically consider obstacle-avoidance and optimality in the sense of “least traffic disruption”, as well as comprising simple mathematics for real-time applicability.

In contrast to optimization-based path-planning approaches that rely on iterative numerical procedures—such as model predictive control (MPC) or nonlinear trajectory-optimization methods—the approach developed here leverages the analytical structure of compressible-flow relations. The governing equations yield closed-form expressions that depend only on the obstacle geometry and the prevailing ‘flow’ conditions, enabling direct computation of admissible trajectories without discretization or repeated optimization cycles. As a result, the computational demand is minimal, and the resulting paths are inherently smooth, non-intersecting, and compatible with vehicle dynamic constraints.

The problem of lane change control may also be defined based on other objectives, such as passenger comfort; Hatipoglu et al. [25] proposed a lane-change controller based on time-optimal control aiming at minimizing the lateral acceleration and jerk. The reference signal to be tracked by the controller is extracted as a reference yaw angle and yaw rate, which are followed by a sliding mode controller. The results were experimentally validated to be effective through a wide range of vehicle speeds.

Although many attempts have been made in order to formulate the lane change, and consequently the overtaking maneuver, there is still room for development of the process with further helpful objectives, such as minimizing traffic disruption, which is becoming a critical demand nowadays with the increased number of vehicles on the roads. The indispensable similarities between traffic flow and compressible fluid flow provide an ideal platform for investigating the effect of using such analogies at the system level for the individual autonomous and semi-autonomous vehicles capable of performing automated lane-keeping and lane-changes.

The concept of “minimum disturbance to traffic flow” is not tied to the resolution or scale of the simulation, but to the inherent physics of shockwave systems. In a supersonic flow field, fluid elements move faster than the speed at which pressure disturbances—through which information about obstacles or boundaries is transmitted—can propagate. As a result, the fluid remains unaware of the obstacle until it reaches a point where deflection becomes unavoidable.

A shockwave forms as the geometric locus of these points: the nearest positions to the obstacle where the flow must change direction to avoid penetration. Its local strength adjusts such that the post-shock flow has the necessary properties (pressure, temperature, velocity) to enable the deflection in time. This same principle applies across any oblique shock surface, including regions offset laterally from the obstacle, whose downstream trajectories must also be redirected accordingly.

Consequently, the proposed method yields the least disturbance to the flow field, as it allows the motion to remain fully supersonic—retaining its regime and velocity—until the last possible moment before a maneuver becomes dynamically unavoidable. In other words, the shockwave system naturally embodies a minimal-disturbance solution: it preserves the upstream flow state as long as possible, introducing abrupt adjustment only at the final point where boundary conditions demand it.

This similarity has been of interest mostly in the context of transportation design and planning, for a cluster of vehicles; however, as the current study reveals, it may also be applied to individual vehicles in a decentralized scheme. This paper investigates such a possibility as a practical application of the proposed methodology for the overtaking maneuver of an autonomous vehicle. The proposed strategy provides the late-but-safe lane-change path and the best path to follow in terms of less traffic flow disruptions in an integrated approach with minimal calculations required, making it ideal for real-time implementation. The relative path planning with respect to the slow vehicle also provides a practical approach in terms of vehicle instrumentation, as common on-board sensors, e.g., RADARs, LIDARs, and cameras, can be directly used to identify the vehicle position within the relative coordinate frame discussed here.

Having the relative target path calculated using the supersonic compressible fluid flow analogy, the rest of the paper discusses a smoothing process on the target path to make it tracking-ready according to vehicle dynamics limits. A path-tracking control algorithm is then suggested, which is able to follow the desired path with considerable accuracy. The designed controller is then applied to different overtaking scenarios at different relative speeds, which are simulated through a 7 DOF vehicle model, validating the proposed path-planning strategy and the performance of the suggested controller. Finally, the results are discussed in Section 4.

2. Aerodynamic Methodology

As the bedrock of the methodology utilized in the current research, the aerodynamic aspects of the compressible fluid flow analogies with those of the traffic are discussed in this section. The section goes further with a brief introduction to the defined Mach number for the special case of traffic flow, referring to previous work for more detailed analysis on the concept and mathematical derivations. Furthermore, required governing equations from the field of gas dynamics and high-speed aerodynamics, leading to the geometric definition of the case for the ‘overtaking maneuver’ as the setup on which the fluid flow analogous methodology of trajectory planning for vehicular flow is to be implemented. Finally, the computational algorithm for the decentralized calculations of the case geometry and flow-field configurations is discussed.

2.1. Compressible Flow Field Analogies

By considering vehicles in traffic flow as individual particles or point representatives of traffic bulk, one reaches the undeniable analogy between traffic flow and a specific type of fluid flow, namely, supersonic compressible flow. The compressibility of a flow of moving or queuing traffic can be defined based on the geometric definition of the concept of compressibility, with respect to the longitudinal distance between vehicles. It is observed that most accelerations lead to alterations in the mentioned distance, which is also consistent with the density change quality of a compression/expansion [1].

As observed from the vehicle’s frame of reference, an acceleration propagated in the flow might be seen primarily as a change in distance, although infinitesimally small, which could be noted as a tendency to change the distance between the reference vehicle and the one ahead of the road. To keep the flow at a constant density, the same acceleration should be reproduced on the reference vehicle, to compensate for the differential change in distance, and keep the said distance as before. However, the process to sense the alteration in speed, namely the acceleration, or the alteration in density, which is compressibility for that matter, along with mental processing for human drivers, or a much faster but still non-zero-time duration of computer processing for autonomously driven vehicles, introduces a time lag to the system of two consecutive vehicles. As a result of the delayed command to the vehicle, followed by a delayed execution of the command, the reference vehicle might be subjected to the same acceleration; however, with a temporal, and therefore a spatial delay, hence the compression/expansion of the flow.

Since the same phenomenon occurs in a compressible fluid flow configuration, as the forefront of the flow might not react to the changes in pressure, which is the kinetic representative of the acceleration in the kinematic realm, the accumulation of the flow particles through collision with the upcoming and unforeseen obstacle is the grounds for compression, as discussed above.

2.2. Traffic Mach Number

In order to quantify the sources and effects of such alterations in density throughout the flow field, Mach number has been introduced in gas dynamics. The dimensionless group is the ratio between the characteristic speed of the bulk of the flow to the speed of sound in the medium. This is due to the fact that the speed of sound could be considered as the velocity by which the pressure waves propagate through the fluid domain, and therefore, the information regarding the existence of an obstacle ahead of the stream travels through the medium. On the other hand, the velocity of the flow is to be compared with the velocity of the information propagating downstream, to which the flow field should adjust itself and take updated trajectories, i.e., accelerate or change the velocity field.

Having M = 0, i.e., either stationary flow/fluid at rest, or infinite velocity of information transfer in the flow, lead to incompressible premise, as at the very first instance a pressure wave is propagated; therefore, there is a need for acceleration to catch up with the flow without changing distances between the particles and maintaining a constant density, and the upstream is informed and able to update trajectories to avoid colliding with the obstacle.

M = ∞, however, means a certain collision of all flow trajectories to the obstacle that emerged suddenly within the flow field, as no information is transferred to the particles in the upstream. M = 1 is the critical point, where the speed of data transfer within the flow field equals the velocity of the flow particles moving towards the obstacle.

To extend the concept behind such a dimensionless group to the flow of vehicles in traffic, one might think of using the same ratio between the speed of traffic flow to the speed of information transfer in the flow, that is, the speed of processing, a need for acceleration, commanding it, and fully deployment of the corresponding actuators. However, since the reflection speed of the driver/car is not essentially a ‘velocity’ derived from dividing a distance by its time duration, the rearranging of the same parameters gives one a better index for compressibility; namely the time needed to go through all abovementioned sources of delay, up to successful deployment of the actuators in charge of the acceleration, over the characteristic time scale of the problem in a kinematic perspective.

Deriving the kinematics of the problem, Amini and Milani [1] proposed the following statement for the traffic Mach number, as a dimensionless group with the same spectral and critical points as the one customarily used for fluid flow problems:

where τ is the reaction time delay of the vehicle/driver combination, L and υ are the characteristic length and velocity of the reference vehicle, and μ and g represent the coefficient of friction of the tires to the road and acceleration of gravity, respectively. A more detailed derivation and discussion on the mathematical aspects of the traffic Mach number can be found in Amini and Milani [1].

2.3. Governing Equations of Compressible Flow

Considering the normal shockwave as a special case of oblique shockwave with strictly defined shock angles, the current section addresses the more general form of oblique shockwave and its corresponding relations.

Given any of the two parameters among the inflow Mach number, the shock angle, and the inward geometry convergence angle, the third parameter could be obtained as a function of the other two, given by the following statement [26]:

The inflow Mach number should be decomposed into two components, normal and tangential to the shock direction:

With the normal components determined, the rest of the calculations could be conveyed sing the less physically complicated equations for normal shockwaves [27]:

Equations (6)–(10) are, then, used to obtain the changes in density, trajectory velocity, pressure, normal Mach number, and temperature after the flow passes through the shockwave. Taking the calculated Mach number back to its original form before the decomposition process, the actual resultant Mach number, which has physical meaning, could be obtained by:

Moving on to the other end of the spectrum of possible physical phenomena, the flow should undergo an expansion when passing through a divergent geometry. The expansion fan, known as Prandtl–Meyer expansion, is bound by the two extrema given by the following statements [28]:

and is aero-thermodynamically calculated through the assignment of the Prandtl–Meyer function to the surfaces before and after the expansion occurs, as well as a reference surface at a Mach number of unity:

where

2.4. The Case—Overtaking Maneuver Geometry

The objective of the current research is to implement the introduced methodology of vehicular traffic path planning, drawing an analogy to the governing equations of supersonic compressible fluid flows [1], for the specific and practical case of a double lane-change during an overtaking maneuver.

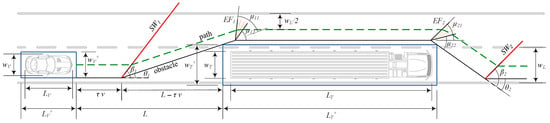

The case geometry includes a low-velocity truck followed by a high-velocity vehicle, both moving with constant, though different speeds. The road is straight, and the left lane is empty. The goal for the following vehicle (ego vehicle) is to overtake the truck, while the truck maintains its velocity. The corresponding traffic Mach number (MT) for the initial conditions of the case configuration leads to the occurrence of the first oblique shockwave (Figure 2), which has been formed in response to the virtual ramp-shaped obstacle of avoiding the corner of a safety margin around the vehicle, colliding with the opposite corner of the safety margin around the truck. The oblique shockwave, then, redirects the trajectory. The next step in trajectory segments is to return to the axial direction of the road in the left lane. Since the underlying motivation for realignment with the road axis is not the lateral barrier of the lane, but the demand to maintain mid-lane orientation while overtaking the leading vehicle, a set of Prandtl–Meyer expansion fans is considered for that matter, instead of the reflection of the very first shockwave from the border of the lane.

Figure 2.

The geometric configuration of the case.

A second expansion fan is then positioned at a longitudinal location, where its corresponding output trajectory will meet the same criteria as the aforementioned virtual ramp. This will leave enough lateral and axial safety margins for the finalization of the overtaking maneuver. A second shockwave prevents penetration of the flow trajectories into the right-side borders of the initial lane, which is then followed by a reorientation/correction maneuver to reach the initial state in terms of velocity and slight lateral displacements.

2.5. Flow Field Solution Algorithm

In accordance with the case geometry discussed in the previous sub-section, Figure 3 presents the zonal configuration and nomenclature of the case.

Figure 3.

Case configuration and zoning nomenclature. (a) Nodes on the trajectory. (b) Zones along the main and by-pass lane.

The initial obstacle is formed as a ramp with the geometrical attributes obtained through the kinematics of the vehicles (Figure 2). The bypass maneuver aligned with the surface of the ramp is dictated by an oblique shockwave oriented as a function of the initial traffic Mach number. First, the Prandtl–Meyer expansion fan aligns the flow with the lane, as the overtaking vehicle reaches the desired lateral position in the left lane. And being far from the leftmost barrier of the road, the reflection of the initial oblique shockwave does not come into play in the overtaking maneuver configuration.

To allow for a safety gap between vehicles when passing, additional safety margins are considered for the vehicles, which act as the envelope for each object. The required safety margin is calculated based on the maximum tracking error recorded in a lane-change maneuver using a similar path-tracking strategy [29], which reported a maximum tracking error of less than 0.1 m corresponding to the lateral direction in generic path-tracking maneuvers. To take conservative safety measures, a safety margin of 0.2 m around each vehicle is considered here.

Considering the absolute MT of the truck after the overtaking vehicle reaches the point ‘E’, the slope of the segment ‘NE’ is determined to reach a safe longitudinal distance between points ‘D’ and ‘E’. A final oblique shockwave reorients the flow with the initial lane when the vehicle reaches the centerline of the said lane (see Algorithm 1). It is worth mentioning that, as the two shockwaves in the case configuration are not isentropic phenomena, the final Mach number and hence the axial velocity of the overtaking vehicle are subject to an acceleration to reach the initial conditions before the maneuver.

It is worth mentioning that the traffic Mach number is defined based on the relative velocity of the two moving vehicles. This, although logical from the standpoint of fluid dynamics principles, might lead to conditions where the initial traffic Mach number is above unity, hence the supersonic premise is met, but the configuration between the triple parameters of β, θ, and the Mach number leads to a detached shock configuration. This happens when the nominal maximum half-wedge angle corresponding to the present Mach number exceeds its limit for an oblique shockwave, which is the simplified basis of the current methodology. Since in the mentioned cases the primary assumptions of supersonic, compressible flow are occurring, and the only deviation is the slight bending of the shockwave geometry from its straight oblique form, a correction procedure has been applied to address the geometric definition of the half-wedge angle leading to the detached configuration. To do that, the ratio between the maximum and that of the calculated one is also used to proportionate the modified length (L). However, the inlet traffic Mach number is to be kept at the original gas dynamics-driven one, when entering the corresponding modified geometry.

| Algorithm 1. Block Algorithm for flow field analogous trajectory |

|

3. Vehicle Dynamics and Control

3.1. Feasible Trajectory

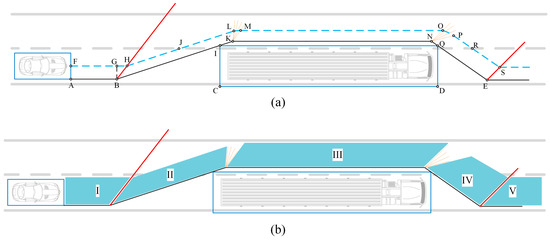

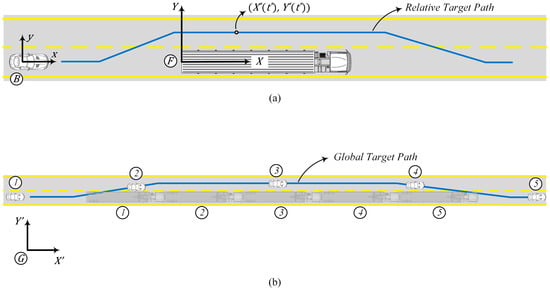

Based on the fluid flow calculations detailed above, the next step is to convert the calculated flow into a physical target path that the vehicle can feasibly follow. The first thing to consider in defining the target path for the path-tracking controller is that the coordinate frame that the path is expressed in must be identified, and the target path should obtain a final form of a sequence of coordinates to be fed into the path-tracking controller on the overtaking (ego) vehicle. The decision on a suitable coordinate frame is somewhat straightforward to make. In the proposed methodology, since the fluid flow is calculated with respect to the moving obstacle, i.e., the vehicle to be overtaken, the coordinates of the desired path may be more easily expressed in a coordinate frame attached to the obstacle and moving with it. This way, the relative position of the ego vehicle will be known to the system at each time instance. Figure 4a shows the coordinate frame used to express the target path.

Figure 4.

Coordinate frames are used to describe the target path. (a) Relative target path. (b) Global target path.

The sequence of the coordinates, however, must also incorporate a desired velocity over the target path, which may be implemented by adding time information to the sequence; in this approach, each pair of desired coordinates is attributed to a specific pseudo time which changes from 0 to 1, from initiation to completion of a single maneuver. Such pseudo-time information is achieved by scaling the real-time information to (0,1), according to the desired velocity along the path and the distance between adjacent desired points. Depending on the resolution of the target path, the number of coordinates and the time instances associated with them will vary. Therefore, at each single time step, the processed target path will be fed into the tracking controller in the form of a pair of corresponding to that specific that the vehicle is in. In this method, the ego vehicle will have path-tracking error information at each time instance in the form of longitudinal and lateral tracking error values [29].

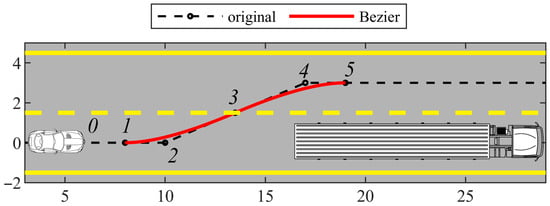

Furthermore, in the general sense of path-planning for autonomous vehicles in complex maneuvers, the feasibility of the target path mainly depends on two conditions to be met, namely the continuity of its curvature and the consistency of the maximum curvature in the path, i.e., the required centripetal acceleration to negotiate the curve, with the available friction between the vehicle tires and the road. The former is mostly significant in the design of roads [30], and the latter is critical in defining the maximum speed calculation, as the same curvature would require less centripetal acceleration to be developed at lower speeds. In the context of an overtaking maneuver, which is essentially a type of double lane-change maneuvers, these conditions tend to be more critical when the relative speed of the ego vehicle with respect to the obstacle is large, e.g., a slowly moving or stationery obstacle; such a condition might need particular attention to smoothing the sharp corners on the target path, which is basically generated by connecting straight lines causing curvature discontinuity in the target path [1]. However, in a non-emergency highway scenario, which is the main focus of this paper, the relative velocity of the ego vehicle and the obstacle is not substantially large, leading to the ego vehicle staying below the traction limits, as observed in the simulations section. Also, the heading angle of the vehicle is close to zero during the maneuvers. Figure 4b shows the target path and the vehicle’s pose in a globally fixed coordinate frame . To be on the safe side and ensure a smooth transition to the adjacent lane, approximating the linear sections with piecewise quadratic Bezier curves, similar to the approach taken in [22], is reasonable for such maneuvers. To that end, a quadratic Bezier curve is considered for each half of the lane-change maneuver which can be controlled via three points, namely the starting point of the lane-change (Point 1 in Figure 5), the corner of the deviating streamline (Point 2 in Figure 5), and the middle point between the lanes (Point 3 in Figure 5); similarly for the second half of the lane-change, the middle point (again, Point 3 in Figure 5), the second corner corresponding to the settling streamline (Point 4 in Figure 5), and the finishing point of the lane-change (Point 5 in Figure 5) are considered. The quadratic Bezier curve is easy to calculate in real-time; additionally, being piecewise, each corner of the unfiltered path can be smoothed while the slopes of the streamlines match the final resulting curve, making Bezier curve the ideal candidate for our formulation. The longitudinal and lateral coordinates are obtained for each section based on the following parametric curve equations:

where t is the independent parameter which varies between 0 and 1. An appropriate resolution of this interval, and therefore, the resulting curve should be chosen according to the computational power and the memory available.

Figure 5.

Smoothed target path using piecewise quadratic Bezier curves.

Specifically, Points 1–3 define the transition from the traveling lane onto the sloped path (the initiation of the lane-change), and Points 3–5 define the transition from the sloped path into the adjacent lane. In both curve segments, the curvature at Points 1 and 3, and at Points 3 and 5, is zero, ensuring straight-line entry and exit conditions. As a result, the two Bézier segments connect smoothly at Point 3, and the overall lane-change path maintains continuous curvature.

The beginning and end points of a single lane-change (points 1, 5 in Figure 5) may be defined with respect to the sharp corners’ locations; here, the sequence of five points is assumed to be equivalent to points G, H, J, L, and M in Figure 5, respectively. The processed target path after polynomial fitting looks like Figure 5.

3.2. Vehicle Dynamics and Control

This section outlines the design of the path-tracking controller, as well as the vehicle model, as the basis for simulations to verify the proposed methodology.

Path-Tracking Controller Design

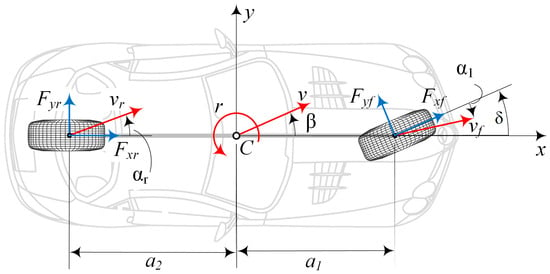

The first step towards designing a path-tracking controller is to properly model the motion of the vehicle in a relatively simple way, which can lead to mathematical relations for control laws. For the purpose of control-oriented modeling, the well-known bicycle model [31] of the ego vehicle is slightly modified to account for the relative kinematics with respect to the moving obstacle. Figure 6 shows the bicycle model with its kinematic variables, as well as the vehicle body coordinate .

Figure 6.

Bicycle model and vehicle coordinate frame.

A standard bicycle model may be presented as [31]:

where and are the variables of the system and represent the lateral and yaw velocities in the vehicle body frame, respectively. There is a third equation for the longitudinal vehicle dynamics, which may be treated as a decoupled differential equation, if the longitudinal velocity is deemed as a varying parameter of the system (17), in normal driving conditions, i.e., not very large accelerations and combined tire slips, the longitudinal dynamics are:

Table 1 summarizes the key vehicle model parameters used in this study [1]. The selection of these parameters is grounded in the dimensional analysis presented in [32], which identifies the dominant geometric, inertial, and tire-related quantities governing typical passenger-vehicle dynamics. A detailed justification of the chosen values, together with their correspondence to a representative real vehicle platform, is provided in our previous work [1].

Table 1.

List of key vehicle model parameters.

It should be noted that the 3-DOF model described in Equation (17) is used solely to formulate the error dynamics and derive the control law. All validation simulations in this study are conducted using the more sophisticated and previously validated 7-DOF vehicle model, which is detailed later in the manuscript.

According to Figure 3a and assuming the heading angle of the ego vehicle to be small and the velocity of the obstacle to be constant, the time derivatives of the longitudinal and lateral coordinates of the ego vehicle in frame become:

Equations (17) and (20) form the lateral vehicle dynamics, while (18) and (19) define the longitudinal motion of the ego vehicle, relative to the obstacle. Assuming the product of to be small, the longitudinal and lateral vehicle dynamics may be defined using the following differential equations, respectively:

Note that and are the inputs, and and in (22) are treated as varying parameters, which are readily measurable.

The input to the path-tracking controller is a pair of desired coordinates corresponding to that specific time instance according to the path-planning level. The objective of the controller is to calculate a proper steering angle and a traction force that can minimize the tracking errors. The control strategy is obtained based on the SMC technique for longitudinal and lateral directions. It is worth mentioning that in normal driving conditions and during such non-emergency overtaking maneuvers, the steering angle can be deemed as the only input affecting the lateral motion and the traction force would be affecting the longitudinal motion; therefore, the vehicle dynamics may be divided into two SISO systems in the longitudinal and lateral directions. Furthermore, the SMC provides a robust control performance which enables its application to a wide range of vehicle parameters; therefore, the control strategy may be only obtained for a nominal set of parameters, but it could be successfully applied to a range of different vehicles with bounded parameter uncertainties; this information may be used in practice in the process of tuning the SMC parameters.

For the longitudinal motion, the tracking error is , and the control input is obtained by adopting a mathematical expression representing the sliding surface as [33]:

Substituting from (18) gives the equivalent control law by setting the derivative of (23) to zero and assuming :

which guarantees stability and convergence to the desired state, if the system is on the sliding surface. However, to account for uncertainties and unmodelled dynamics, a more robust control law is obtained by adding a regulatory term to force the system to tend to the sliding surface while reducing chattering [33]:

where is the saturation function. Since the tire slips are assumed to be small, to apply this force to the vehicle, a simplified relationship between the driving torque and the traction force may be used:

In terms of the lateral control, the tracking error is defined as , and the required steering angle to minimize the lateral tracking error is obtained by defining a sliding surface represented by:

The equivalent control law for steering is obtained by substituting from (22) and assuming :

Similarly to the lateral control, the complete control law for steering becomes:

A similar SMC control design was previously applied in [34]. As an inherently nonlinear controller, SMC has been shown to remain effective even in severe driving conditions—such as drifting scenarios involving very large sideslip angles. Consequently, its capabilities exceed the requirements of the present study, where the vehicle operates well within the linear range of tire behavior.

The controller parameters are listed in Table 2. The controller parameters were tuned manually with the objective of achieving stable behavior, minimal oscillations, and accurate path tracking. The tuning process was informed by insights from [1,34], which provided guidance on appropriate parameter ranges and sensitivity characteristics. Although more sophisticated optimization-based tuning methods—incorporating parameter uncertainties and formal performance criteria—could be employed, such an investigation lies beyond the scope of the present study. As the primary focus here is to establish and validate the proposed fluid-dynamic analogy for path planning, automated optimization is reserved for future work in conjunction with experimental validation of the proposed scheme.

Table 2.

Controller parameters.

It is important to note that the present study does not aim to benchmark the proposed tracking strategy against alternative control frameworks. The SMC controller is employed here primarily as a representative mechanism to validate the feasibility of tracking the trajectories generated by the fluid–dynamic analogy. A detailed quantitative comparison between this SMC design and an MPC-based lane-change controller has already been conducted in our earlier work [29], where real-time implementability and performance trade-offs were thoroughly examined. For completeness, the key conclusions of that study are summarized here to contextualize the present approach: the SMC controller offered comparable tracking accuracy to MPC while providing significantly lower computational cost, making it suitable for real-time applications.

3.3. Simulation Model

The simulations are presented in this section to validate the proposed analogy and to show the feasibility of applying it to vehicles in a more realistic vehicle dynamics environment. Although the control design was based on vehicle dynamics, the same model should not be used for validation purposes, as it would serve as a nominal condition for the system. Nevertheless, a more realistic vehicle model with consideration of combined-slip tire forces and the ability to handle high lateral and longitudinal accelerations provides a reasonably realistic environment for evaluating the proposed method. The simulation model incorporates 7 degrees of freedom, namely the longitudinal, lateral, and yaw motions, as well as the rotational dynamics of the wheels, which is adopted from [29]. The realistic magic formula tire force model for combined-slip condition [35] is used to calculate tire forces.

All simulations presented in this study were carried out in MATLAB/Simulink(2023b) using a previously developed 7-DOF vehicle dynamics model [34]. This model was originally created and validated in [34], where it demonstrated strong accuracy in reproducing real vehicle behavior across both linear and nonlinear regimes, including high sideslip and sliding maneuvers. In the present study, these maneuvers occur well within the linear tire-force region, making the validated 7-DOF model a robust and conservative platform for evaluating the proposed path-planning approach.

4. Results and Discussion

Considering the nonlinear behavior of the traffic Mach number defined in this study and the geometric constraints of the case configuration, the initial longitudinal distance between the vehicle and the truck is obtained.

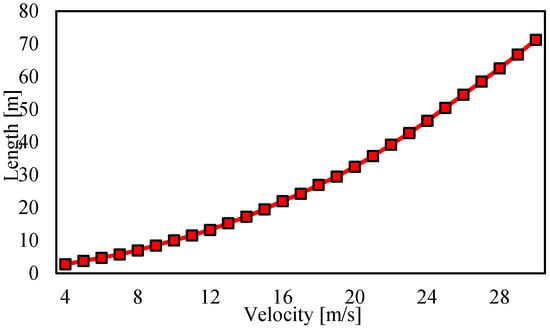

Table 3 presents the range of applicable and pragmatic values for vehicle relative velocity and distance. The calculated MT for the cases presented in Table 3 shows the behavior of the traffic Mach number in extreme, marginal areas of the cases domain. This includes a negative growth of MT with respect to relative length at constant velocities, while a positive growth is witnessed in MT with respect to relative velocity and at a constant distance from the obstacle.

Table 3.

Traffic Mach number values for the applicable V/L phase space. The Traffic Mach number values are also shown as the background colors.

It should also be noted that the magnitude of changes in MT due to slight changes in velocity is more significant than its response to chances in length scale, for an individual local point in the cases domain.

This has led to a minimum value of 1.27 reported for the MT of considered cases in the current study, and a maximum reported MT of 3.54. This ranges from the lower spectrum of non-transonic, supersonic flows up to, and within a safe margin of, hypersonic flows, which is precisely the validity range for the underlying theoretical fundamentals of this study.

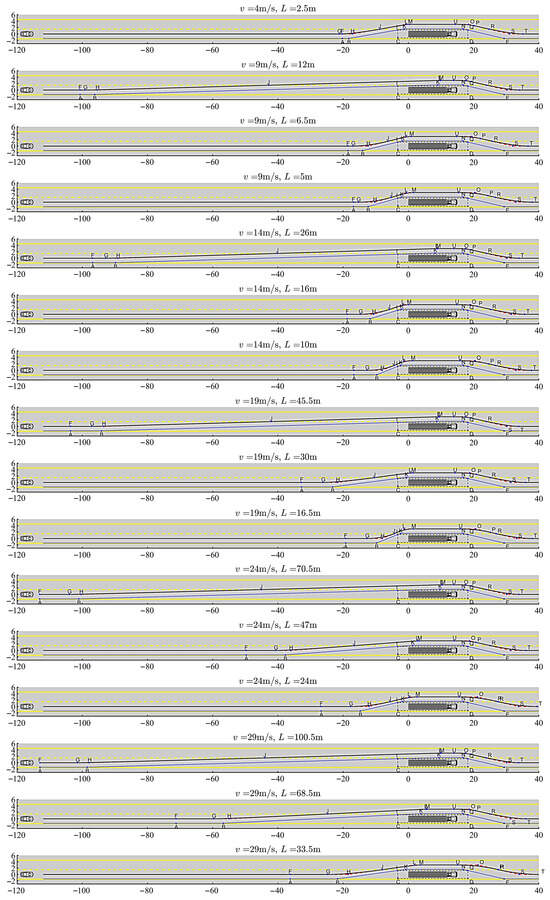

A second order curve is fitted through the average vehicle lengths as a function of their relative velocity (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Average length as a function of relative velocity.

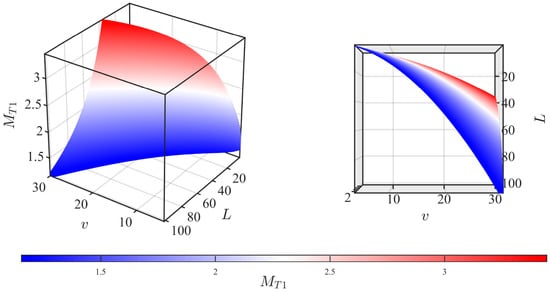

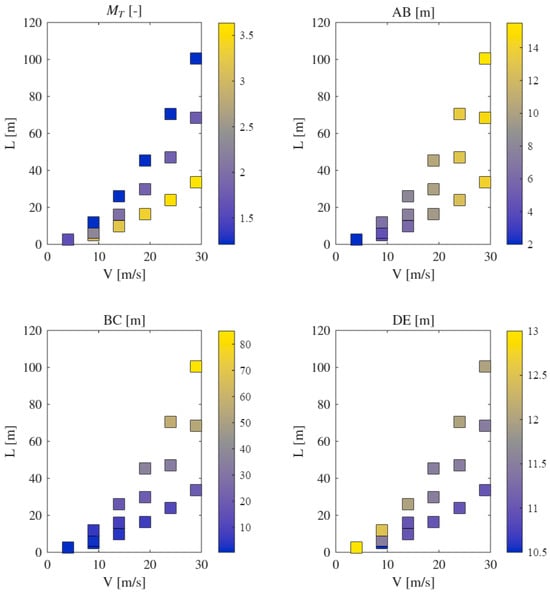

Table 4 presents the specification in the form of length scale as a function of the instantaneous, relative velocity and Mach number. The MT has been divided into three categories with 1.2 to 1.5, 1.9 to 2.1, and 2.4 to 3.6 considered low, mid, and high, respectively. The ranges of MT for different regions of the domain are also illustrated as a surface function in form of MT = f(L,V) in Figure 8.

Table 4.

Selected cases specification L [m] = f(V,MT).

Figure 8.

Surface function of MT = f(L,V).

To visualize the results of the path generation algorithm, the cases listed in Table 4 are calculated using the proposed methodology and the target paths are plotted in Figure 9, with identical locations of the slow vehicle (the truck) and the overtaking one. Note that the coordinates in the figure are relative (expressed in frame F) and indicate the relative desired trajectory of the vehicle with respect to the truck. The figure shows how the traffic Mach number affects the resulting target path; at low Mach numbers, the first lane-change maneuver starts sooner, while at large Mach numbers, the vehicle moves closer to the obstacle before changing lanes. It is important to note that the configuration of the target path is dependent on both the relative velocity and the distance L, which is a design parameter and affects the traffic Mach number. As observed in the figure, a certain velocity may be paired with a range of values for L, modifying the target path’s geometry. At a constant velocity, the larger the L, the earlier the start of the first lane-change maneuver. As indicated in Figure 8 and Figure 9, there will be a lower limit for the value of L at a certain velocity, where the Mach number exponentially increases, limiting the level of proximity of the vehicle to the truck. In other words, the safe distance is automatically considered in the proposed methodology by establishing the fluid dynamics analogy. The returning maneuver is more similar in different cases due to traffic safety measures incorporated in the trajectory planning and the fact that the condition ahead of the road is almost similar in all cases. This is different in nature from the inflow condition where the vehicle is faced with a slower-moving obstacle ahead of the path, leading to the relative definition of a traffic Mach number and starting the maneuver from that initial condition.

Figure 9.

Case configurations corresponding to values listed in Table 4 for the entire maneuver—truck only shown in final position.

It should be noted that the condition at hand is different from cases where a ramp-shaped obstacle with a fixed angle is located in front of the flow, the supersonic compressible flow reaches the ramp, and acts based on the fundamentals dictating the shockwaves to be more bent towards the ramp in higher Mach numbers. In the current study, even the slope of the ramp, and hence its starting point to avoid the left corner of the truck, is obtained as a function of the inflow state. This has led to the counterintuitive outcome of lower Mach number flows taking the trajectory with gentler obliquity. The reason behind the choice of the inflow slope is discussed in detail in previous sections on the calculations regarding the formation of the maneuver case geometry.

It is also worth mentioning that the extreme lower limit case of V = 4 m/s and L = 2.5 m, with the MT roughly equal to 1.2, is showing much shorter pre-incidence length, as the flow field reaches the supersonic range boundary, and the relative velocity of the vehicles is in the range of walking pace. This condition and the safety implication of M = 1 flow fields and their correspondence to the walking zone safety velocities are discussed in depth in Amini and Milani [1].

To better summarize the geometric configurations of the results shown in Figure 9 and Figure 10, we present MT and the lengths AB, BC, and DE for the cases in Figure 9 (also see Table 4), as per the nomenclature presented in Figure 3. It is seen that for each selected velocity V, the lowest length L corresponds to the highest MT. In general, the reflection distance, denoted AB in Figure 3, is seen to peak at the highest V and L combinations, which, to a lesser degree, is consistent with the length BC. It should be noted that the length BC is primarily equal L—AB, as per Figure 3. Regarding the length DE, which is the longitudinal distance of the final placement of the ego vehicle in front of the overtaken truck, although the lowest combination of (V,L) leads to the maximum DE, all obtained lengths are in a narrow spread of the distance obtained through safety instructions.

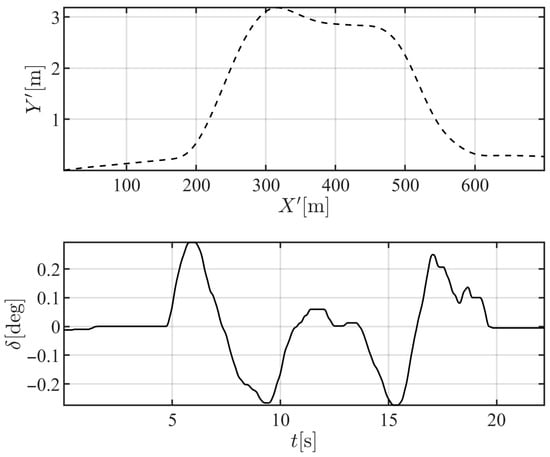

Furthermore, to compare with the natural behavior of an experienced human driver, a relative overtaking velocity of 9 m/s (32.4 km/h) is selected when the slow vehicle (obstacle) is traveling at a constant speed of 80 km/h. A driving simulator is used to record the behavior of a real human driver at that speed. Figure 11 shows the responses of the human driver, in terms of the vehicle’s mass center location in the global frame and the steering angle, indicating a relatively smooth reaction and a very small range of steering inputs. The driver naturally tends to start the maneuver gradually, as observed in the first 200 m of longitudinal travel. The maneuver is effectively completed in 15 s and within 400 m of longitudinal travel, where the vehicle is approximately located on the adjacent lane for 300 m.

Figure 11.

Human driver’s response at relative velocity of v = 9 m/s.

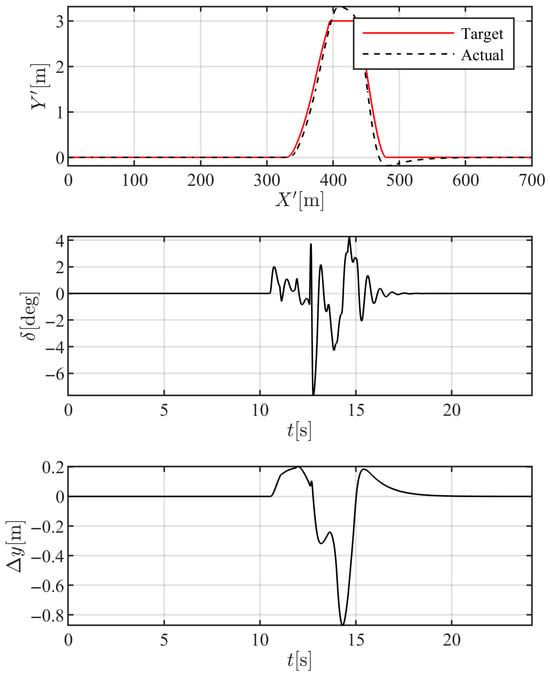

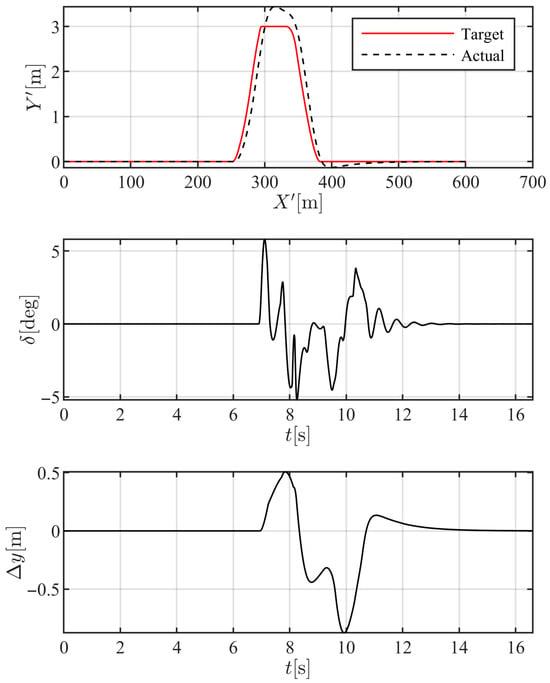

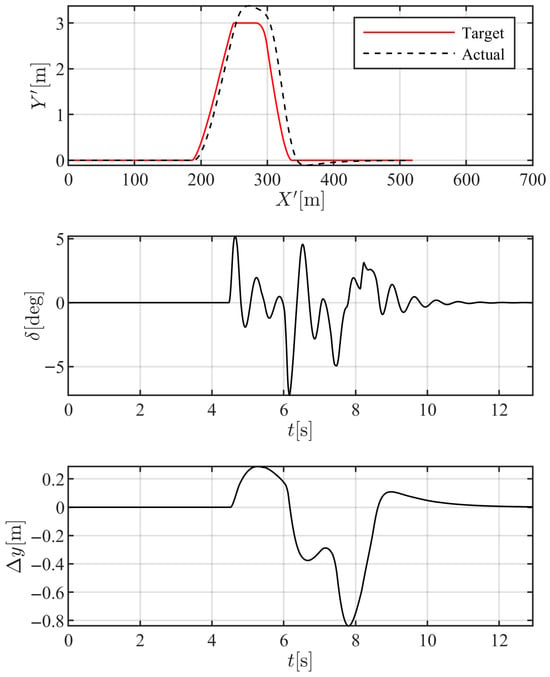

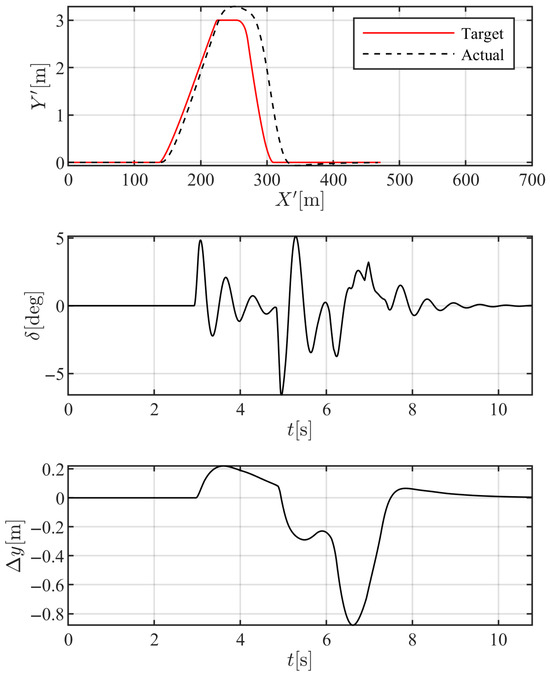

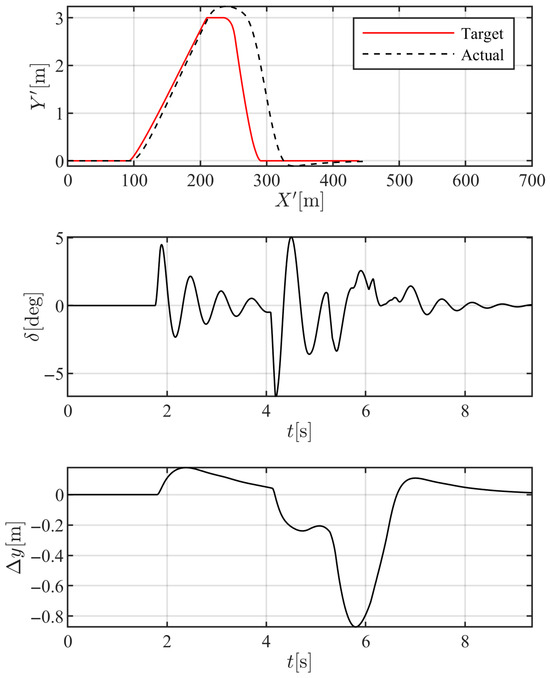

To demonstrate the performance of the proposed control scheme for autonomous driving at different speeds, the velocities and distances corresponding to the middle range of Mach numbers in Table 4 are used to simulate the vehicle motion equipped with the proposed controller, and the results are visualized in Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15 and Figure 16. Note that the vehicle trajectory is shown in global coordinates, and the axes are not in scale; therefore, a dedicated lateral tracking error plot for the autonomous vehicle is presented to show the deviation of the actual and desired vehicle locations as observed in the vehicle body coordinates. The Root-Mean-Square Error (RMSE) is also shown in the caption of each figure.

Figure 12.

Autonomous maneuver at v = 9 m/s, L = 6.5 m (RMSE = 0.185 m).

Figure 13.

Autonomous maneuver at v = 14 m/s, L = 16 m (RMSE = 0.226 m).

Figure 14.

Autonomous maneuver at v = 19 m/s, L = 30 m (RMSE = 0.235 m).

Figure 15.

Autonomous maneuver at v = 24 m/s, L = 47 m (RMSE = 0.225 m).

Figure 16.

Autonomous maneuver at v = 29 m/s, L = 68.5 m (RMSE = 0.229 m).

One may compare the resulting overtaking maneuver using the proposed scheme with that of a human driver by comparing Figure 11 and Figure 12 corresponding to the same relative velocity (9 m/s). In the autonomous maneuver of Figure 12, the maneuver is completed in about 120 m of longitudinal travel and 7 s, where the vehicle occupies the adjacent lane in approximately 100 m of the maneuver, which is one-third that of the human driver. This indicates that the proposed methodology provides an optimal solution to the overtaking problem in terms of minimizing traffic disruption and minimum maneuver time, while the physical constraints are handled through the analogy with fluid dynamics. In the case of a two-way road, the minimized overtaking time/distance also provides the best solution for minimizing the risk of collision with upcoming traffic. Although more aggressive steering inputs are applied by the autonomous driver, the controller gains may be optimized for the best combination of passenger comfort and performance, as required in the application. Also, the lateral tracking error shows a maximum of 0.8 m error in the returning maneuver, indicating a reasonable path-tracking performance of the proposed controller, as well as demonstrating the feasibility of the proposed analogy and its consistency with vehicle dynamics.

At higher relative speeds, the vehicle reaches the obstacle more quickly, and the required steering effort becomes more aggressive. Considering the fact that the middle range of Mach numbers is simulated, the overall shape of the target path with respect to the obstacle location does not change much in different scenarios, but the initiation of the first lane-change maneuver starts slightly earlier at higher speeds. The lateral tracking error is slightly larger at higher speeds, but still in a reasonable range. It is worth mentioning that a relative velocity of 29 m/s is quite a large relative velocity for overtaking; therefore, the performance of the analogy and the control system both satisfy the normal driving conditions.

5. Conclusions

Considering the fundamental analogies between the flow of traffic and supersonic, compressible fluid flow, corresponding meaningful parameters are defined for the flow of traffic to mimic and allow the implementation of some known gas dynamics principles to it. Among the most important ones, a non-dimensional group of kinematic and kinetic parameters is defined to form the equivalent of the Mach number for the traffic flow.

The traffic Mach number factor is the time delay of the driver and actuator system’s dynamics, the rheological properties of the tires and road combination, and the geometric length and time scales of the local situation, such as the velocity of the vehicle and its instantaneous distance from the obstacles/traffic ahead.

Using the Mach-dependent relations for supersonic, compressible fluid flow, the problem could be applied to different configurations and scenarios plausible on a road system. Following the previous work on the proof of concept of the core idea used also as the main methodology of the current manuscript [1], the specific case of an overtaking maneuver by an autonomous driving vehicle bypassing a slower-moving truck is addressed in this paper. The aerodynamic configuration of the case geometry dictates a certain combination of shockwaves and Prandtl–Meyer expansion fans, which are described in detail throughout the manuscript.

The resulting maneuver geometries demonstrated a promising alignment with the primary premise of supersonic, compressible fluid flow trajectories. As the next step, they are tested with vehicle dynamics approaches. The process begins by smoothing the resulting trajectory into a physically meaningful one for the vehicle using quadratic Bezier curves. The smoothed trajectory is then fed into a designed control system as the reference target path to be tracked by the autonomous driver. Simulations of typical highway scenarios demonstrated the consistency of the proposed analogy with vehicle dynamics and tire–road interaction, as well as compatibility with classical control approaches, indicating that the proposed approach may be used as a path-planning strategy for autonomous vehicles in overtaking maneuvers. Furthermore, it was shown that the proposed approach is capable of automatically considering the required safety distance between vehicles by incorporating the information regarding the system’s reaction delay.

Finally, the simulation results are compared with a human driver’s behavior in terms of steering input and the vehicle trajectory, indicating that a more efficient overtaking maneuver, i.e., less distance traveled on the adjacent lane, is achieved using the proposed methodology at the expense of more aggressive steering. However, it should be noted that the proposed approach benefits from a certain range of flexibility in parameter L, which affects the final target path, and it could be used to adjust the path according to the situation.

It should be noted that the present study considers an open overtaking lane and a straight-road scenario to demonstrate the core feasibility of the proposed fluid-dynamic path-planning concept. In more complex environments—such as when the adjacent lane is partially occupied or when multiple types of road users are present—additional factors such as traffic regulations, right-of-way rules, and safety constraints must be incorporated. These considerations can be addressed through a higher-level decision-making layer that operates above the trajectory-generation module. Such a supervisory layer can define or adapt the admissible ‘boundaries’ within which the fluid-analogy planner operates, thereby triggering different responses depending on the traffic context. Although extending the framework to multi-vehicle, regulation-aware scenarios is a natural progression, this work focuses on establishing the underlying concept, and these extensions are left for future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.A. and S.M.; methodology, K.A. and S.M.; software, S.M.; validation, K.A. and S.M.; formal analysis, K.A. and S.M.; investigation, K.A. and S.M.; resources, K.A. and S.M.; data curation, K.A. and S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, K.A. and S.M.; writing—review and editing, K.A. and S.M.; visualization, K.A. and S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the valuable assistance from Sahand Milani in developing the driving simulator used in this paper and obtaining the human driver data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Nomenclature

| Latin Letters | ||

| Mach number | - | |

| Traffic Mach number | - | |

| Time | s | |

| Longitudinal velocity component | m/s | |

| Lateral velocity component | m/s | |

| Pressure | N/m2 | |

| Speed of sound | m/s | |

| Acceleration of gravity | m/s2 | |

| Temperature | K | |

| Heat | J | |

| Enthalpy | J | |

| Maximum breaking acceleration | m/s2 | |

| Specific heat (P = const.) | J/kg∙K | |

| Specific heat (V = const.) | J/kg∙K | |

| Molecular degree of freedom | - | |

| Traffic length scale | m | |

| Vehicle’s longitudinal and lateral velocities in the vehicle body frame | m/s | |

| Velocity of the obstacle | m/s | |

| Yaw velocity of the vehicle | rad/s | |

| Front/rear axle’s cornering stiffness | N/rad | |

| Vehicle mass | kg | |

| Vehicle yaw moment of inertia | kg∙m2 | |

| External longitudinal/lateral force on the vehicle | N | |

| External yaw moment on the vehicle | Nm | |

| Obstacle-fixed coordinate frame | - | |

| Globally fixed coordinate frame | - | |

| Vehicle body coordinate frame | - | |

| Function representing a sliding surface | m/s | |

| Torque on the driving wheels | Nm | |

| Torque on wheel | Nm | |

| Wheel radius | m | |

| Equivalent traction force for control | N | |

| SMC traction force control law | N | |

| Longitudinal force at tire | N | |

| Greek Letters | ||

| υ | Velocity | m/s |

| ρ | Density | kg/m3 |

| τ | Reaction time delay | s |

| γ | Poisson constant | - |

| θ | Wedge half angle | deg |

| β | Oblique shockwave angle | deg |

| μ | Friction coefficient | - |

| ν | Prandtl-Meyer function | deg |

| μ1 | First Mach line angle | deg |

| μ2 | Last Mach line angle | deg |

| Front/rear tire’s slip angle | rad | |

| Vehicle body side-slip angle | rad | |

| Distance from mass center to front/rear axle | m | |

| Steering angle | rad | |

| Controller parameters | - | |

| Equivalent steering angle for control | rad | |

| SMC steering control law | rad | |

| Angular velocity of wheel | rad/s | |

| Abbreviations | ||

| SW | Shockwave | |

| EF | Expansion Fan | |

| AOA | Angle of Attack | |

| SMC | Sliding Mode Control | |

| SISO | Single-Input Single-Output | |

| DOF | Degree of Freedom | |

| Subscripts | ||

| 1 | Pre-shock/expansion state | |

| 2 | Post-shock/expansion state | |

| T | Traffic | |

| V | Vehicle | |

| T | Truck | |

| R | Road | |

| L | Lane | |

| n | Normal | |

| t | Tangential | |

| ∞ | Free stream/Far field | |

| char | Characteristic | |

| + | Dimensions with safety margins | |

References

- Amini, K.; Milani, S. Path Planning for Autonomous Vehicle Control in Analogy to Supersonic Compressible Fluid Flow—An Obstacle Avoidance Scenario in Vehicular Traffic Flow. Future Transp. 2025, 5, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellomo, N.; Marasco, A.; Romano, A. From the Modelling of Driver’s Behavior to Hydrodynamic Models and Problems of Traffic Flow. Nonlinear Anal. Real World Appl. 2002, 3, 339–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonzani, I.; Mussone, L. Stochastic Modelling of Traffic Flow. Math. Comput. Model. 2002, 36, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabari, S.E.; Liu, H.X. A Stochastic Model of Traffic Flow: Theoretical Foundations. Transp. Res. Part B 2012, 46, 156–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daganzo, C.F. Requiem for Second-Order Fluid Approximations of Traffic Flow. Transp. Res. Part B 1995, 29, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogendoorn, S.P.; van Wageningen-Kessels, F.L.M.; Daamen, W.; Duives, D.C. Continuum Modelling of Pedestrian Flows: From Microscopic Principles to Self-Organised Macroscopic Phenomena. Phys. A 2014, 416, 684–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogendoorn, S.P.; van Wageningen-Kessels, F.; Daamen, W.; Duives, D.C.; Sarvi, M. Continuum Theory for Pedestrian Traffic Flow: Local Route Choice Modelling and Its Implications. Transp. Res. Procedia 2015, 7, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, W., Jr.; Méndez, A.R. On the Kinetic Theory of Vehicular Traffic Flow: Chapman–Enskog Expansion versus Grad’s Moment Method. Phys. A 2013, 392, 3430–3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coscia, V.; Delitala, M.; Frasca, P. On the Mathematical Theory of Vehicular Traffic Flow II: Discrete Velocity Kinetic Models. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 2007, 42, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Lu, W.-Z.; Xue, Y.; He, H.-D. Revised Lattice Boltzmann Model for Traffic Flow with Equilibrium Traffic Pressure. Phys. A 2016, 443, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Cui, J. Traffic Flow Density Distribution Based on FEM. Phys. Procedia 2012, 25, 939–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, H.; Chen, Q.-Y.; Ni, D. Traffic Viscosity Due to Speed Variation: Modeling and Implications. Math. Comput. Model. 2010, 52, 1626–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, S.; Cowling, T.G. The Mathematical Theory of Non-Uniform Gases: An Account of the Kinetic Theory of Viscosity, Thermal Conduction and Diffusion in Gases, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, P.I. Shockwaves on the Highway. Oper. Res. 1956, 4, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Ahn, S.; Laval, J.; Zheng, Z. On the Periodicity of Traffic Oscillations and Capacity Drop: The Role of Driver Characteristics. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2014, 59, 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.M. Driver Memory, Traffic Viscosity and a Viscous Vehicular Traffic Flow Model. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2003, 37, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darbha, S.; Rajagopal, K.R.; Tyagi, V. A Review of Mathematical Models for the Flow of Traffic and Some Recent Results. Nonlinear Anal. 2009, 69, 950–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zocca, M.; Guardone, A.; Cammi, G.; Cozzi, F.; Spinelli, A. Experimental observation of oblique shock waves in steady non-ideal flows. Exp. Fluids 2019, 60, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiller, Z.; Sundar, S. Emergency Lane-Change Maneuvers of Autonomous Vehicles. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control 1998, 120, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, F.; Zhang, R.; Lie, G.; Wang, H.; Wen, H.; Xu, J. Trajectory Planning and Tracking Control for Autonomous Lane Change Maneuver Based on the Cooperative Vehicle Infrastructure System. Expert Syst. Appl. 2015, 42, 5932–5946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Liu, Y.; Lv, C.; Ji, X.; Liu, Y. Emergency Steering Control of Autonomous Vehicle for Collision Avoidance and Stabilisation. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2019, 57, 1163–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhao, P.; Mei, T.; Liang, H. Lane Change Path Planning Based on Piecewise Bezier Curve for Autonomous Vehicle. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Vehicular Electronics and Safety; IEEE: Dongguan, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cesari, G.; Schildbach, G.; Carvalho, A.; Borrelli, F. Scenario Model Predictive Control for Lane Change Assistance and Autonomous Driving on Highways. IEEE Intell. Transp. Syst. Mag. 2017, 9, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandru, R.; Selvaraj, Y.; Brännström, M.; Kianfar, R.; Murgovski, N. Safe Autonomous Lane Changes in Dense Traffic. In Proceedings of the IEEE 20th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC); IEEE: Yokohama, Japan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hatipoglu, C.; Ozguner, U.; Redmill, K.A. Automated Lane Change Controller Design. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2003, 4, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.D. Modern Compressible Flow, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Courant, R.; Friedrichs, K.O. Supersonic Flow and Shock Waves; Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Liepmann, H.W.; Roshko, A. Elements of Gasdynamics; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Milani, S.; Khayyam, H.; Marzbani, H.; Melek, W.; Azad, N.L.; Jazar, R.N. Smart Autodriver Algorithm for Real-Time Autonomous Vehicle Trajectory Control. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 23, 1984–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzbani, H.; Jazar, R.N.; Fard, M. Better Road Design Using Clothoids. In Sustainable Automotive Technologies 2014; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Jazar, R.N. Vehicle Dynamics: Theory and Application; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, S.; Alleyne, A. Robust scalable vehicle control via non-dimensional vehicle dynamics. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2001, 36, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slotine, J.-J.E.; Li, W. Applied Nonlinear Control; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Alamdari Milani, S. Modelling, Analysis, and Control of Four-Wheel Independently Actuated Vehicles at Handling Limit. Ph.D. Thesis, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia. [CrossRef]

- Pacejka, H. Tire and Vehicle Dynamics, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).