Abstract

Traditional shipping in Indonesia, known as Pelra (Pelayaran Rakyat), plays an important role in connecting the archipelago and supporting inter-island economic activities. However, this sector faces significant challenges due to the low competency levels of human resources, particularly among ship crews. The examination system, including mechanisms and competency standards for traditional shipping crews, has not been updated for the past three decades, while shipping technology has advanced considerably. This study analyzes the competency levels of Pelra ship crews in South Sulawesi, focusing on certification compliance, technical proficiency, and navigational skills. Both quantitative and qualitative approaches were applied, utilizing Spearman correlation and gap analysis to assess crew competency levels. The findings indicate that engine crews face difficulties in meeting certification requirements for Chief Engineer and Motorman positions, while deck crews struggle to fulfill crewing demands as the vessel size increases. Engine crew competencies remain weak in engine maintenance, repair, and installation, whereas deck crews show limitations in compass use, seamanship, and understanding currents and tides. These gaps negatively affect technical performance, safety, and operational efficiency. The study highlights the urgent need for a revised training system, an updated technical curriculum aligned with industry demands, and adaptive policies harmonized with national competency standards to strengthen professionalism and competitiveness in the traditional shipping industry.

1. Introduction

Around 80% of the volume of international trade in goods is carried by sea, and the percentage is even higher for most developing countries []. This industry continues to grow rapidly through the adoption of digital technologies, automation, and environmentally friendly energy sources []. However, despite these advancements, the gap in maritime human resource competency remains a critical challenge, particularly in developing countries [].

In the global context, traditional shipping—referring to vessels utilizing simpler technology—holds unique importance in supporting coastal communities and preserving maritime culture. In countries like Indonesia and the Philippines, traditional shipping not only facilitates inter-island trade but also contributes to maritime heritage []. Nonetheless, limited access to formal education and training often leaves crew members relying on informal, experience-based knowledge without adequate competency in safety and efficiency practices [].

Indonesia, as an archipelagic nation with over 17,500 islands, relies heavily on traditional shipping (locally known as Pelayaran Rakyat or Pelra) to connect remote areas and support logistics, tourism, and essential services [,]. The Pelra system is vital in reaching underserved regions and has been integrated into the national Sea Toll program to enhance inter-island connectivity and reduce regional disparities [,,].

Despite its strategic role, traditional shipping faces numerous challenges, such as competition with commercial fleets, operational limitations, and heightened safety risks due to outdated practices [,]. Many crew members lack formal training, and human error remains a leading cause of maritime accidents [,]. Informal recruitment, hereditary knowledge transfer, and insufficient access to maritime education, especially in remote regions, have resulted in a workforce that is underqualified to meet modern shipping demands [,,,].

This competency gap is compounded by a lack of institutional support and professional development systems. Family-based management structures often prioritize loyalty over skill, which hampers innovation and safety compliance [,]. Without structural reform, traditional shipping companies will struggle to compete within a global maritime industry that increasingly demands standardization and regulatory adherence [].

Presidential Regulation No. 74 of 2021 highlights the Indonesian government’s recognition of this issue and calls for improving human resource capacity through training, certification, and modernization efforts []. Yet, implementation remains constrained by funding, community access, and limited awareness among industry actors.

Although prior research has explored the socio-economic and cultural dimensions of traditional shipping [,], few studies have examined crew competency levels, certification fulfillment, and the operational challenges faced by traditional vessels, particularly in South Sulawesi. Therefore, this study seeks to answer the following research question: what are the competency and certification gaps among traditional shipping crew members in South Sulawesi, and how do these gaps affect technical operations and maritime safety?

By addressing this question, the study aims to analyze human resource characteristics in Pelra shipping, focusing on certification attainment and technical competencies. The findings are expected to inform policy recommendations and contribute to the design of industry-relevant training programs, thereby enhancing the professionalism and competitiveness of Indonesia’s traditional shipping sector.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

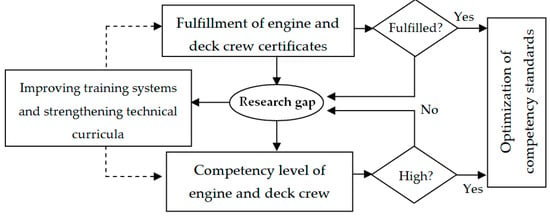

This study uses a qualitative approach to evaluate the characteristics of the crew and the level of fulfillment of the certification of the crew of the deck and engine departments of Pelra ships. A quantitative approach is used to analyze the relationship between education level, ship size, and type of position on the ship with the fulfillment of the crew certificate, as well as to analyze the level of competence of Pelra ship crews with gap analysis. The research flow of thought can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research flow.

2.2. Research Location

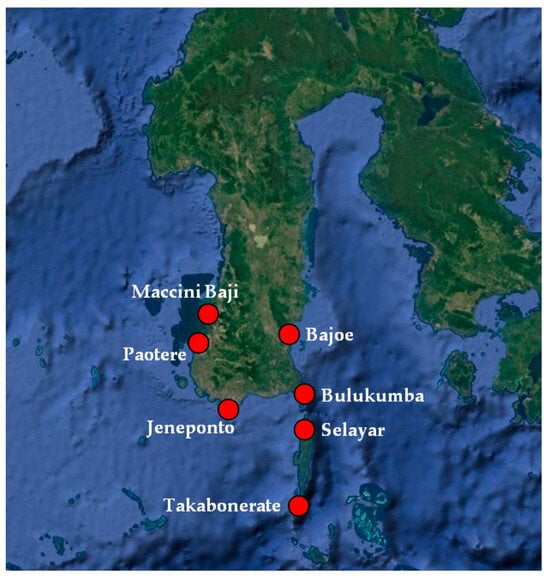

The research was conducted at Pelra Paotere Port (Makassar City), Takabonere Port and Selayar Port (Selayar Regency), Jeneponto Port (Jeneponto Regency), Bajoe Port (Bone Regency), Maccini Baji Port (Pangkep Regency), and Bukulumba Port (Bulukumba Regency) in South Sulawesi. The location of the ports can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Research location.

South Sulawesi was selected as the research location due to its long-standing role as a hub of traditional shipping in Eastern Indonesia. The region has a high concentration of Pelra activity and diverse ship sizes, making it a representative area to examine operational practices and crew competency. However, it is important to note that findings from this region may not fully reflect the conditions of traditional shipping in other parts of Indonesia with different socio-economic and maritime profiles.

2.3. Research Sample

This study was conducted on 33 Pelra ships operating across seven ports in South Sulawesi. The selection was carried out from a list of vessels registered with local port authorities and that were active during the survey period. While the initial design intended to apply random sampling, in practice, the selection was influenced by ship availability and crew willingness to participate, making it closer to a convenience sampling approach. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted with caution in terms of generalizability beyond the sampled region.

The ship sizes varied from 7 GT to 500 GT. The most common were vessels sized between 25 GT and 100 GT (55%), while only 3% of the sample consisted of ships sized 200–315 GT. The total number of crew members sampled was 128, comprising 48 deck crew and 80 engine crew members. In terms of age distribution, the largest groups were those aged 31–42 years and 43–55 years, each comprising 39.8% of the sample. Regarding experience, 43.8% had worked as Pelra crew members for over four years. Education-wise, 46.1% had completed senior high school, followed by junior high school (34.4%) and elementary school (19.5%). More detailed respondent characteristics are shown in Table 1. By clarifying the sampling procedure and limitations, this section acknowledges that while the data reflect the characteristics of Pelra crews in South Sulawesi, they may not fully represent the national population of traditional shipping crews in Indonesia.

Table 1.

Characteristics of research respondents.

2.4. Data Collection Methods and Research Instruments

Data collection was conducted through semi-structured surveys and interviews, in stages, distributing questionnaires to obtain data related to the crew’s experiences and challenges in fulfilling certification and training. The research instrument used a questionnaire with a 4-point Likert scale (1 = unable, 2 = less able, 3 = quite able, 4 = able) and interview guidelines. The questionnaire was compiled based on seven assessment indicators by the testing procedure system established by the Director General of Sea Transportation with the number PY.68/I/5-86 for each type and level of crew skills. The engine crew had 25 questions, and the deck crew had 35 questions. For the engine crew, indicators included (1) skills on the working principles of combustion engines, (2) propulsion motor installations, (3) fuel installations, (4) engine maintenance and repairs, (5) lubrication systems, (6) cooling systems, and (7) engine operation. Meanwhile, for the deck crew, indicators included (1) basic navigation skills (positioning), (2) maps, (3) currents and tides, (4) collision prevention regulations, (5) sailor skills, (6) loading procedures, and (7) safety. Reliability was tested separately for engine and deck crew instruments: Cronbach’s alpha for the engine crew scale (25 items) was 0.72, while the deck crew scale (35 items) showed 0.79, both of which indicate good internal consistency.

2.5. Analysis Method

This study uses Spearman correlation analysis to measure the relationship between education level, ship size, and crew position and the certification fulfillment level required for each position according to ship size. This technique was chosen because it is suitable for ordinal and non-parametric data, providing an understanding of the strength and direction of the relationship between variables []. Gap analysis is used to identify differences between the actual level of crew competency and the expected competency standards []. The results of this analysis determine the future direction of the types of skills that need to be prioritized and further policies for developing competencies to improve the safety and operational efficiency of traditional shipping.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with ethical research standards and received formal approval from the Ethical Committee on Social Studies and Humanities, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN). The approval is documented under Ethical Clearance Approval No. 199/KE.01/SK/02/2025, issued on 14 February 2025. All participants were informed about the purpose of the research, their voluntary involvement, and the right to withdraw at any time without penalty. Informed consent was obtained from each respondent prior to the survey and interviews. The anonymity and confidentiality of participant data were strictly maintained throughout the study.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characteristics of the Ship’s Crew

3.1.1. Reasons for Becoming Ship Crew

The choice to become a crew member of Pelra is influenced by economic conditions, cultural heritage, and personal motivation. The dominant reason, at 33%, is the limited job opportunities in other sectors. This reflects the limited labor market conditions in the industrial sector. In total, 29% of participants chose this career to continue the family business. This shows the strong family ties in the maritime community in South Sulawesi, where sailing skills are passed down from generation to generation, especially in the operation of Pelra ships, which are part of the maritime identity in South Sulawesi. In addition to economic and traditional factors, other reasons are intrinsic motivation and financial considerations. As many as 29% of respondents chose to be sailors because they have an interest and pleasure in working as sailors, which reflects the importance of maritime culture in people’s lives. This shows that despite various operational challenges, such as an aging fleet of ships, an informal employment structure, and uncertain income, many individuals still find personal satisfaction in becoming crew members. Only 9% of respondents chose this job because the income is higher than working on the land. This relatively small percentage indicates that although there are economic incentives, these factors are not the main drivers for most Pelra crew members. This condition also reflects the instability of income in the Pelra sector, which is influenced by fluctuations in transportation demand, limited government support, and minimal access to financial services. This finding indicates that socio-economic factors in the employment of the Pelra sector have implications for the sustainability of the workforce and the need for policy intervention to improve the welfare of ship crews.

3.1.2. Experience Working on Ships

Most (44%) crew members have more than 4 years of work experience on Pelra vessels, 32% have between 2 and 4 years of experience, and 24% have worked for less than 2 years. The proportion of crew members with more than 4 years of experience shows that this sector is still able to retain workers for a relatively long period of time, despite challenges in terms of welfare and working conditions. The high number of crew members with less than 4 years of service indicates a significant level of workforce turnover, caused by factors of income instability, difficult working conditions, or better job opportunities in other sectors. It was also found that 44% of crew members plan to work on Pelra vessels for 2–5 years, and 32% plan to work for more than 10 years. This shows that although this sector is still attractive to some workers in the long term, the majority of crew members see it as temporary work before moving on to other professions or improving their standard of living through more stable work. The low average of crew members planning to work in the short term (1–2 years, only 8%) can also be interpreted in that most workers are still considering the relative advantages offered by the shipping sector compared to other alternatives. Only 16% of crew members intend to stay for 5–10 years. The Pelra industry faces challenges in the long term of workforce sustainability, which can impact operational stability and workforce regeneration. Therefore, it is necessary to increase the attractiveness and welfare of workers so that the Pelra industry can survive and develop amidst the ever-changing economic and social dynamics.

3.1.3. Level of Technological Literacy

The gap in the development of the shipping industry is the low technological literacy among the Pelra crew members. It can be explained that 55% of crew members do not have computer skills, while 63% are not familiar with the concept of virtual accounts, so they still rely on traditional customary systems in shipping operations, which affects the mastery of technology, potentially hindering shipping efficiency and effectiveness. In particular, technology related to GPS-based route monitoring, electronic recording, and digital payment systems would be of significant use. This limitation can also slow down the Pelra industry’s adaptation to government policies that increasingly encourage the use of technology in maritime transportation, including the implementation of digital-based reporting systems and non-cash transactions to increase transparency and financial security for ship crews. In total, 5% of ship crew members do not yet have the ability to use smartphones. Although this percentage is relatively small, limited access to mobile technology can limit workers’ ability to access weather information, digital navigation, or more effective communication with land parties. In fact, in the modern maritime era, the use of application-based technology has become an integral part of improving the safety and efficiency of ship operations. This low level of digital literacy can also worsen the Pelra industry’s lag compared to other shipping industries that have previously adopted technology to increase competitiveness.

3.1.4. Accident Aspects

Incidents of accidents in traditional shipping transportation remain a serious problem. The survey indicated that 34% of respondents reported having experienced work-related accidents on Pelra ships, and 29% reported involvement in more than one incident. This suggests that accidents are not isolated events but recurring challenges in Pelra operations. Commonly reported types of incidents included occupational injuries (e.g., falls, being struck by equipment, or being crushed by cargo), shipboard fires often linked to non-marine electrical systems, and collisions and groundings resulting from limited navigation skills, inadequate equipment, and unpredictable weather. While these findings highlight safety concerns and coincide with identified competency gaps among engine and deck crews, they should be interpreted with caution. Because the data are perception-based and self-reported, they indicate possible associations between lower competency and accident involvement but do not establish causality within the scope of this study.

3.2. Certification of Traditional Shipping Crews

The fulfillment of the certification of deck and engine crew members shows the competency standards of Pelra’s industry human resources. The reference for determining certification standards for Pelra crew members is based on the Decree of the Director General of Sea Transportation No. PY.66/1/2-02 of 2002 concerning Safety Requirements for Kapal Layar Motor (KLM). The research findings show that of the 80 engine crew members, only 46.2% meet the certification standards according to these provisions, while 53.8% have not met the requirements set. On the other hand, of the 48 deck crew members (Captain, Officer, and Helmsman), 68.7% meet the certification requirements, while 31.3% have not met the requirements. Although there has been an increase in the fulfillment of certification for deck crew members, the significant gap in the certification of engine crew members remains a major concern. The low level of certification for engine crew members can increase the potential for operational risks, especially in terms of the technical safety of the ship. Uncertified engine crews are likely to have limitations in implementing ship operational procedures, as well as handling and maintaining engines according to standards, including handling emergencies. This affects the operational performance of the ship, increasing the chances of engine damage, fires, or accidents caused by the technical negligence of incompetent crews. Meanwhile, although deck crew certification shows a better level of compliance, the potential risk of accidents caused by the lack of understanding and inability of deck crews to navigate safely, especially in busy shipping lanes or bad weather, cannot be avoided. This condition has a long-term impact on the Pelra industry, because non-compliance with the certification stipulated in the regulations can reduce the competitiveness of Pelra ships in facing increasingly tight global competition in the maritime sector. The limitations of crew competency certificates can also have an impact on increasing accidents, financial losses, and damage to the reputation of the Pelra industry, which will further reduce the trust of the public and users of marine transportation services. Furthermore, without adequate certification, the Pelra sector will have difficulty adapting to the modernization trend and increasing safety standards expected by the government.

3.3. Relationship Between Education Level, Position on Ship, and Ship Size with Fulfillment of Crew Certificate

The low level of fulfillment of Pelra crew certificates for both engine and deck crews is caused by the variables of crew education, position level on the ship, and ship size. Between variables, there is a level of correlation with the level of fulfillment of crew certificates. The results of the Spearman correlation analysis on engine crews show that there is a significant negative correlation between the position of engine crews and the level of fulfillment of engine crew certification (r = −0.627, p = 0.000). This finding indicates that the higher the position of an engine crew on a Pelra ship, the more difficult it is to fulfill the certificate (Table 2). In the context of the Pelra industry in Indonesia, this can be associated with the limited number of workers who have sufficient certification and experience to fill high positions in the ship’s crew system. Higher engine crew positions, such as the head of the engine room, require a more complex level of technical expertise, as well as longer work experience.

Table 2.

Correlation of fulfillment of engine crew certificates to education, position on ship, and ship size.

On the other hand, the variables of education level (r = −0.075, p = 0.510) and ship size (r = 0.081, p = 0.475) did not show a significant correlation with the fulfillment of the certificate of the engine crew. This means that the level of formal education of an engine crew does not correlate with the fulfillment of the workforce needs on Pelra ships. This is because the Pelra workforce recruitment and development system focuses more on practical experience and technical skills than on the level of formal education. In addition, the absence of a significant correlation between ship size and the fulfillment of the engine crew indicates that the availability of engine workers is not directly affected by the size of the ship being operated.

Meanwhile, for the deck crew (Table 3), the results of the Spearman correlation analysis showed that there was a significant negative correlation between ship size (GT) and the level of fulfillment of the deck crew certificate (r = −0.409, p = 0.010). This indicates that the larger the size of the ship, the more difficult it is to fulfill the needs of the deck crew. In the context of the Pelra industry in Indonesia, this phenomenon can be attributed to the limited workforce that has adequate certification and competence to crew larger ships. Larger Pelra ships generally require deck crews with higher levels of expertise, while the training and development system for workers in the Pelra industry has not been fully able to keep up with these needs. In addition, Pelra ships with larger GT often have more complex operational demands than smaller ships.

Table 3.

Correlation of fulfillment of deck crew certificates to education, position on ship, and ship size.

In contrast, the variables of education level (r = 0.023, p = 0.876) and position on the ship (r = 0.143, p = 0.331) did not show a significant correlation to the fulfillment of deck crew certificates. This means that the level of formal education and position level in the Pelra ship organizational structure do not directly affect the fulfillment of crew needs. This finding reflects that although education and position levels can be indicators of individual competence, other factors such as economic incentives, perceptions of career prospects, and industry competitiveness play a greater role in determining the fulfillment of deck crew personnel. In Indonesia, many maritime graduates prefer to work in the more promising shipping sector, such as foreign-flagged ships or large commercial ships, so that the Pelra sector has difficulty in attracting and retaining qualified workers.

3.4. Level of Competency of Traditional Shipping Ship Crews

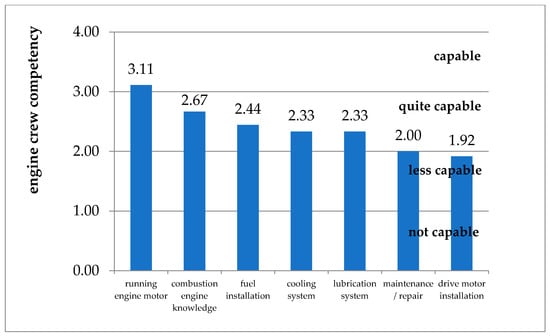

The findings of the exploratory analysis in Figure 3 indicate that the average level of technical competence of the engine crew on the Pelra ships is still in the relatively capable category. Of the seven indicators evaluated, only one showed a relatively high level of competence, namely the ability to operate a motor (score 3.11). Meanwhile, the other six indicators include knowledge of combustion engines (2.67), fuel installations (2.44), cooling systems (2.33), lubrication systems (2.33), engine maintenance and repairs (2.00), and motor or ship propulsion installations (1.92), indicating capabilities that are in the range of sufficient to less capable.

Figure 3.

Competency level of engine crew.

These results have substantive implications for the operational safety and reliability of the traditional shipping system. Competence deficits in fundamental technical aspects directly increase the potential for engine failure during shipping, especially on pioneer routes that generally have minimal emergency infrastructure support. In addition, a low capability of maintaining and installing engine components also contributes to increased ship downtime and decreased efficiency of the maritime supply chain. These consequences not only disrupt service continuity and punctuality but also increase exposure to safety risks for passengers and cargo.

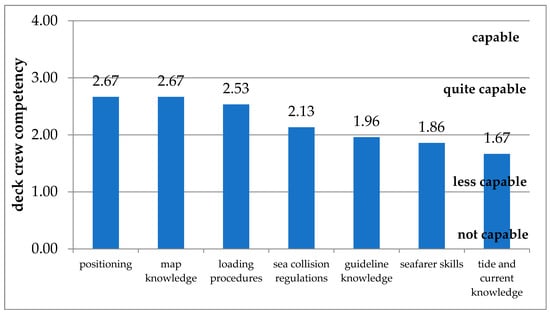

The results of the analysis of the level of competence of the deck crew in Figure 4 show that the technical ability of the crew is at a relatively less capable level (2.21). Of the seven indicators evaluated, three of them are in the fairly capable category, namely the ability to determine position (2.67), map knowledge (2.67), and knowledge of loading procedures (2.53). However, the other four indicators show a low level of competence, namely the knowledge of collision regulations at sea (2.13), knowledge of guidelines (1.96), seamanship (1.86), and knowledge of currents and tides (1.67). These findings indicate a significant gap in basic navigational aspects and seafaring skills that are fundamental to ship operations.

Figure 4.

Competency level of deck crew.

This finding is very relevant in the context of traditional shipping safety, especially in remote waters that have significant navigation challenges. A low understanding of collision regulations and ocean current dynamics can increase the risk of accidents, especially in bad weather or narrow crossings. The inability to read the guidelines and the lack of seamanship skills weaken the crew’s capacity to make critical decisions at sea. Therefore, deck crew competence is one of the key aspects that affects the reliability of Pelra ship operations and safety as a whole.

3.5. Implications of Research

The findings of this study reveal a significant gap in the competence of engine and deck crews of Pelra in Indonesia. For engine crews, there is a limited number of personnel with adequate certification and experience to assume key technical roles, such as chief engineer and machinist. This directly affects their ability to carry out engine maintenance and repair, manage fuel systems, and understand the principles of combustion engines, leading to higher operational costs and increased risk of technical failure. Similarly, deck crews face competency issues in basic navigation, seamanship, and tidal knowledge skills that are especially critical on larger vessels. The scarcity of certified, skilled personnel exacerbates these gaps as vessel size increases. These results align with Setianto et al.’s study [], which found low competence levels among engine room leaders and first engineers.

From a technical perspective, these findings underscore the urgency of reforming Pelra crew training and certification systems. Simulation-based training technologies should be adopted more widely in maritime training centers across Indonesia to improve skill acquisition and reduce human error. The CDIO (Conceive–Design–Implement–Operate) framework, proposed by Le [], could also serve as a modern instructional model to align maritime education with industry standards. Emergency simulations and training with modern equipment are essential to improve the operational reliability of Pelra vessels [].

Given that most traditional shipping operations in Indonesia are family-run and characterized by informal management systems, training initiatives should be designed to accommodate this reality. Government agencies can collaborate with Pelra associations and family-owned operators to implement localized, community-based training models. Mobile training units, on-site simulation modules, and peer mentoring systems could serve as feasible alternatives for traditional operators with limited access to formal maritime education.

From a policy standpoint, this study points to the need for more adaptive and enforceable manning regulations, as well as enhancements in the quality of competency-based maritime education. Low mastery of technical and navigation skills, especially among crews of large vessels, threatens the competitiveness of the Pelra sector in an era of increasing global safety and efficiency demands. The importance of safety training, as emphasized by Kusumawati [] and Dhany et al. [], further supports the need to strengthen curricula and engage industry stakeholders more directly in the certification process. In addition, policies should begin to integrate foundational digital skills into training programs, as the modern shipping industry increasingly relies on digital tools for navigation, communication, and compliance. The current low level of digital literacy among traditional ship crews presents a serious challenge to this transformation.

It should also be noted that this study’s focus on South Sulawesi presents a geographical limitation. While this region was chosen for its active Pelra operations and historical maritime significance, the findings may not fully generalize to all traditional shipping contexts in Indonesia. Regional variations in infrastructure, education access, and maritime policy enforcement can influence crew competency outcomes. Future studies should incorporate broader regional samples to validate and extend the conclusions drawn here.

4. Conclusions

Traditional shipping (Pelayaran Rakyat or Pelra) plays a vital role in supporting maritime connectivity and inter-island economic activity in Indonesia. However, limited crew competence remains a significant challenge. Research findings indicate that engine crews possess low technical capabilities in engine maintenance, repair, and motor installation. These weaknesses are compounded by the scarcity of certified and experienced personnel in critical roles such as chief engineer and machinist, which increases the risk of technical failures and operational costs. Similarly, deck crews show deficiencies in navigation, seamanship, and understanding maritime guidelines. As vessel size increases, the shortage of competent, certified personnel becomes more acute.

These findings highlight the urgent need for reforms in simulation-based training and improvements to technical curricula aligned with industry needs. Adaptive policies that integrate national competency standards are essential to enhance the professionalism and competitiveness of the Pelra sector. Based on the findings, this study recommends the following actions: (i) For the government and regulators, provide accessible, subsidized, and regionally distributed certification programs. Strengthen inter-institutional collaboration between training centers, maritime associations, and Pelra operators. Establish routine audits and enforce safety compliance for traditional vessels. (ii) For traditional shipping companies, invest in continuous technical training for engine and deck crews. Implement a merit-based recruitment and promotion system. Begin a gradual integration of simple digital tools to improve safety and operational efficiency.

This study has several limitations. First, the geographic focus was limited to South Sulawesi Province. Second, the analysis emphasized technical and certification dimensions, while social and cultural influences on crew competence were not examined. These limitations open avenues for further research, including evaluating the effectiveness of training reforms, digital integration in Pelra operations, and stakeholder collaboration. Future studies may adopt a more holistic framework by involving maritime industry players and educational institutions to build a sustainable ecosystem for training and certification. Despite these limitations, this study provides a valuable contribution toward improving the structure of Pelra crew competency and enhancing the safety, efficiency, and competitiveness of traditional shipping in Indonesia.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.S. and M.Y.J.; methodology, O.S., T.R. and M.Y.J.; validation, O.S. and M.S.S.A.; formal analysis, O.S., T.R., M.Y.J. and M.S.S.A.; investigation, O.S.; writing—original draft preparation, O.S.; writing—review and editing, T.R. and M.Y.J.; visualization, M.S.S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethical Committee on Social Studies and Humanities, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), Approval No. 199/KE.01/SK/02/2025 (approved on 14 February 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset is available upon request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Pelra | Traditional shipping/Pelayaran Rakyat |

| GT | Gross tonnage |

| GA | Cronbach’s alpha |

| KLM | Kapal Layar Motor |

References

- UNCTAD. Trade and Development Report. 2024. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/tdr2024_en.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Babica, V.; Sceulovs, D.; Rustenova, E. Digitalization in Maritime Industry: Prospects and Pitfalls. In ICTE in Transportation and Logistics 2019. ICTE ToL 2019; Ginters, E., Ruiz Estrada, M., Piera Eroles, M., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Intelligent Transportation and Infrastructure; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsan, E.; Surugiu, F.; Dragomir, C. Factors of Human Resources Competitiveness in Maritime Transport. In Human Resources and Crew Resource Management; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016; pp. 35–38. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9780203157299/chapters/10.4324/9781315266299-9 (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Turgo, N.; Sampson, H. Modernity and Tradition at Sea: Filipino Seafarers and Their Superstitious Beliefs. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. 2024, 54, 252–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horck, J. A Mixed Crew Complement: A Maritime Safety Challenge and Its Impact on Maritime Education and Training. Bachelor’s Thesis, Malmö Högskola, Lärarutbildningen, Malmö, Sweden, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Humang, W.P. Competitiveness of Traditional Shipping in Sea Transportation Systems Based on Transport Costs: Evidence from Indonesia. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2023, 18, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunaryo, S.; Djatmiko, E.; Fariya, S.; Kurt, R.; Gunbeyaz, S. A Gap Analysis of Ship-Recycling Practices in Indonesia. Recycling 2021, 6, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahid, A.; Jinca, M.Y.; Rachman, T.; Malisan, J. Implementation of Safety Management System on Traditional Shipping for Strengthening the Blue Economy. E3s Web Conf. 2023, 425, 3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humang, W.P. Demand Model and Stakeholder Roles to Increase General Cargo Loads of Traditional Shipping Transportation. War. Penelit. Perhub. 2021, 33, 47–56. (In Indonesian) [Google Scholar]

- Triantoro, W. Comparative Cost Analysis of Domestic Container Shipping Network: A Case Study of Indonesian Sea-Toll Concept. J. Penelit. Transp. Laut 2020, 22, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetiawan, A.; Zainuri, M.; Wijayanto, D. Integration of Traditional Shipping in the Marine Toll of Indonesia: Determining the Priority and Management Strategy. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 750, 12051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Febriansyah, F.; Febriani, M.; Agustini, E. Maritime Safety and Security Policies to Support Marine Transportation Systems. Iwj Inland Waterw. J. 2020, 2, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batalden, B.M.; Sydnes, A.K. Maritime Safety and the ISM Code: A Study of Investigated Casualties and Incidents. Wmu J. Marit. Aff. 2013, 13, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T. Building a Fusion Information System for Safe Navigation. Int. J. Fuzzy Log. Intell. Syst. 2014, 14, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesar, L.D. Emerging Dynamics of Training, Recruiting and Retaining a Sustainable Maritime Workforce: A Skill Resilience Framework. Sustainability 2023, 16, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adikwu, F.E.; Esiri, A.E.; Aderamo, A.T.; Akano, O.A.; Erhueh, O.V. Evaluating Safety Culture and Its HR Implications in Maritime Operations: Current State and Future Directions. Int. J. Manag. Entrep. Res. 2024, 6, 3755–3777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, R.M.; Boyle, A.J. The maritime environment: A comparison with land-based remote area health care. Aust. J. Rural. Health 1998, 6, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Praetorius, G.; Hult, C.; Österman, C. Maritime Resource Management: Current Training Approaches and Potential Improvements. TransNav Int. J. Mar. Navig. Saf. Sea Transp. 2020, 14, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakasnaki, M. The Impact of Quality Management Systems (ISO Standards, ISM Code, TQM) on the Management and Performance of Shipping Companies. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Piraeus, School of Maritime and Industrial Studies, Department of Maritime Studies, Pireas, Greece, 2016. Available online: http://didaktorika.gr/eadd/handle/10442/40382 (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Pemerintah Republik Indonesia. Presidential Regulation No. 74 of 2021 Concerning the Empowerment of Traditional Shipping. 2021. Available online: https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Details/175383/perpres-no-74-tahun-2021 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Malisan, J.; Puriningsih, F.S. Empowerment of Traditional Shipping for Inter-Island Transportation in the Framework of Developing the Archipelago Region in Eastern Indonesia. War. Penelit. Perhub. 2019, 27, 1. (In Indonesian) [Google Scholar]

- Malisan, J. Safety of Maritime Transportation of Traditional Shipping: Case Study of Phinisi Fleet. Ph.D Thesis, Universitas Hasanuddin, Makassar, South Sulawesi, Indonesia, 2013. (In Indonesian). [Google Scholar]

- Lalla, M. Fundamental Characteristics and Statistical Analysis of Ordinal Variables: A Review. Qual. Quant. 2017, 51, 435–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazhari, S. Competency of Merchant Ship Officers in the Global Shipping Labour Market: A Study of the ‘Knowing-Doing’ Gap. Ph.D. Thesis, Cardiff University, Cardiff, Wales, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Setianto, T.; Wisudo, S.H.; Imron, M.; Wiyono, E.S.; Novita, Y. Competency Evaluation of Non-Convention Fishing Vessel Crew (Case Study: 30–100 Gt Purseiner in Pati Regency and Pekalongan City). IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1147, 12023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.Q. Approaching CDIO to Innovate the Training Program for Seafarers to Meet the Requirements of the Industrial Revolution 4.0. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2019, 9, 648–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muslim, A.; Hanik, K.; Astriawati, N. The Effect of Plan Maintenance System and Crew Readiness on the Smooth Operation of MV. Asike Global at PT. Pelayaran Korindo Jakarta. Brill. Int. J. Manag. Tour. 2022, 2, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumawati, E. Analysis of the Improvement of Maritime Safety through Seafarer Skills Training Cooperation between Poltekpel Surabaya and the Main Shipping Office of Tanjung Perak. Devotion 2023, 4, 2300–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhany, M.; Azhmy, M.F.; Pasaribu, F. Analysis of The Role of Safety Training in Improving the Quality of Human Resources Onboard Mv. Golden Competence. J. Manag. Entrep. Tour. 2024, 2, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).