Abstract

Chest X-ray radiology report generation is a challenging task that involves techniques from medical natural language processing and computer vision. This paper provides a comprehensive overview of recent progress. The annotation protocols, structure, linguistic characteristics, and size of the main public datasets are presented and compared. Understanding their properties is necessary for benchmarking and generalization. Both clinically oriented and natural language generation metrics are included in the model evaluation strategies to assess their performance. Their respective strengths and limitations are discussed in the context of radiology applications. Recent deep learning approaches for report generation and their different architectures are also reviewed. Common trends such as instruction tuning and the integration of clinical knowledge are also considered. Recent works show that current models still have limited factual accuracy, with a score of 72% reported with expert evaluations, and poor performance on rare pathologies and lateral views. The most important challenges are the limited dataset diversity, weak cross-institution generalization, and the lack of clinically validated benchmarks for evaluating factual reliability. Finally, we discuss open challenges related to data quality, clinical factuality, and interpretability. This review aims to support researchers by synthesizing the current literature and identifying key directions for developing more clinically reliable report generation systems.

1. Introduction

Chest radiography [1] is the most frequently performed medical imaging procedure worldwide [2]. However, its central role is increasingly challenged by a global lack of radiologists and rising workloads. The capacity of specialists to interpret medical images is often surpassed by demand in many areas [3]. In the United States, the high volume of imaging examinations is reported to surpass the current capacity of radiologists [3]. In resource-limited countries, the situation is more severe. For instance, in 2015, Rwanda had only 11 radiologists for a population of 12 million people [4], and similarly, Liberia had just two practicing radiologists for its population of four million [5]. This lack of radiologists contributes to reporting delays and makes the diagnosis prone to human error. Consequently, there is an increasing interest in using deep learning solutions to assist with radiological interpretation. To reduce human error and reporting delays, the use of automated medical reporting systems is a promising solution [3].

The development of deep learning for creating chest X-ray reports has seen significant progress lately. It is largely due to vision–language models that simultaneously analyze images and generate reports. These are essentially computer vision systems combined with advanced natural language processing techniques that are able to understand the X-ray images and generate their clinical report to ensure it closely mimics the radiologist’s workflow [6,7]. Advanced approaches have been developed recently, such as transformer-based architectures [8], contrastive vision-text learning [9,10,11], models enhanced with medical knowledge bases [12], memory-enhanced models [13], anatomically and expert-guided models [14,15], and Multi-View and longitudinally guided models [16].

While significant progress has been made, generating reliable and clinically accurate reports is still difficult. Current models are susceptible to hallucinations (producing findings absent from the image) and the omission of clinically significant abnormalities [17,18]. Many models are trained and evaluated on a limited number of public datasets, such as MIMIC-CXR, IU X-rays, and CheXpert [19,20,21]. Although useful, these datasets represent certain demographic and reporting patterns and thus cannot be effectively generalized to other institutions. Furthermore, the training of most current systems is primarily performed on the frontal. As a result, these models show limited performance with lateral views. This reduces their applicability in real-world clinical workflows [22]. The evaluation methodology is another major limitation. Standard natural language generation metrics such as BLEU (Bilingual Evaluation Understudy) or ROUGE (Recall-Oriented Understudy for Gisting Evaluation) are still widely used, but they correlate poorly with clinical accuracy and often fail to capture factual errors. Despite the availability of multiple clinically oriented metrics like CheXbert F1 [17], RadGraph F1 [23], and other studies on LLM evaluation [22], there is no consensus on a robust and standardized framework for evaluation. Finally, a persistent challenge of these models is their interpretability and trustworthiness. The lack of transparency of deep learning models makes it challenging for clinicians to verify the reasoning behind generated reports. Also, variable accuracy across different datasets and patient subgroups remains a major barrier to clinical adoption.

Multiple reviews of radiology report generation for chest X-rays have been published recently. While early studies discussed general diagnostic tasks [24], more recent reviews have focused more specifically on radiology report generation [3,25]. Some studies specifically addressed multi-modal inputs [6], or gave a global overview of current practices and future directions [26]. However, the need for an updated review is motivated by the rapid evolution of the field and the emergence of new strategies to improve the clinical factuality of the generated reports. Our work provides an analysis with a focus on the most recent architectures (2024–2025), different improvement strategies, and evaluation practices. It also discusses the current challenges and future perspectives, complementing the existing reviews.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- We describe the key public datasets and benchmarks, including their characteristics, strengths, and limitations, as well as details on dataset diversity and the availability of multi-view or follow-up data.

- We review the evaluation metrics and methodologies, including standard natural language metrics like BLEU and ROUGE, clinically oriented ones such as RadGraph and CheXbert, and LLM-based evaluation protocols. We also discuss their correlation with human and radiologist judgment.

- We present the latest architectures and approaches used in current vision–language models with a focus on encoder-decoder architectures, joint image-text generation, and large vision–language models (LVLMs). We cover key approaches such as transformer-based models, contrastive learning, knowledge augmentation, memory, and variants guided by anatomy, experts, and multi-stage or conversational methods.

- We investigate recent key methodologies proposed to improve factual accuracy and domain adaptation. This includes retrieval-augmented generation, bootstrapping of large language models, and automated preference-based alignment.

- We discuss actual persistent challenges and gaps, including generalization across institutions, limitations of using only frontal X-rays, reliance on single or non-longitudinal exams, interpretability, and clinical trust.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the overall review methodology. Section 3 reviews the public datasets and benchmarks used for chest X-ray report generation. The evaluation metrics and methodologies are discussed in Section 4. Section 5 presents deep learning-based architectures. Recent methodologies designed to improve factuality and domain adaptation are described in Section 6. In Section 7, current challenges and open research directions are highlighted. Finally, Section 8 concludes the review and outlines perspectives for future work. Additional details on the mathematical formulations of NLG metrics and complementary evaluation metrics are provided in Appendices Appendix A and Appendix B.

2. Methodology

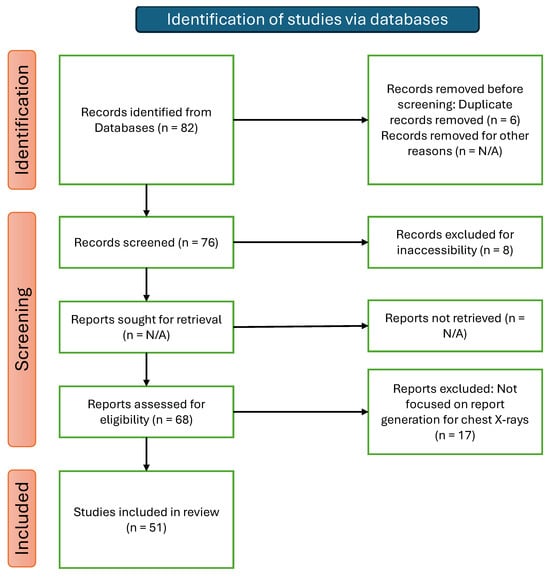

In the process of reviewing the literature, we conducted searches on Google Scholar, PubMed, IEEE Xplore, arXiv, and the ACL Anthology using wide combinations of keywords such as radiology report generation, chest X-ray, medical vision–language models, multimodal learning, evaluation metrics, and clinical factuality. Combinations of these keywords were used to retrieve the articles, including “chest X-rays + radiology report generation”, “vision-language model + chest X-rays”, “CXR + deep learning”, “radiology report generation + LLM + chest X-rays”, “report generation + evaluation metrics” and “retrieval-augmented generation + radiology report generation + chest X-rays”. Our review focuses on the period from 2018 through September 2025, with particular attention to 2024–2025. This focus captures the recent shift to large, transformer-based vision–language models and methods designed to improve clinical factuality. For inclusion, we selected peer-reviewed papers and influential preprints that reported clear methods and quantitative experiments on public or institutional datasets. We included studies addressing report generation for chest X-rays written in English and publicly available. Work on non-medical captioning without text generation, such as unimodal classification, segmentation, and detection, was excluded. Non-English papers, duplicates, and inaccessible articles were also removed. To reduce bias, we first removed duplicates across databases. We then expanded our coverage by tracing references and papers that cited key studies. From each study, we extracted key information such as model family, training data and scale, and pretraining or alignment strategies. We also noted the evaluation setup and metrics, clinical factuality checks, expert or radiologist evaluation, and data availability. A total of 82 records were initially identified across all databases. This large number of articles was then refined by deleting duplicates (n = 6); 76 articles remained. During the screening phase, we eliminated articles that were not publicly available (n = 8) and out-of-scope (n = 17). A total of 51 studies were included in the final review. The PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) summarizes the identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and final inclusion of studies.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of records identification and selection for this review.

3. Medical Datasets for Report Generation

An important component of recent advances in automatic chest X-ray radiology report generation is public, large-scale, annotated datasets. The most popular used datasets contain chest X-rays paired with free-text or structured radiology reports of specialists and radiologists. This data is required for the training and validation of the models and also for the comparative evaluation across diverse clinical tasks, including visual question answering (VQA) and report generation. The design and performance of generation models are influenced by the differences in dataset size, report format, annotation quality, and pathology coverage. In this section, we will review the most widely used public datasets used for radiology report generation. Characteristics such as size, content, and clinical relevance are presented. A summary table (Table 1) reports key properties of each discussed dataset.

3.1. MIMIC-CXR

Developed by Johnson et al. [19], MIMIC-CXR represents one of the largest publicly available datasets of chest X-ray images. It contains 377,110 images and 227,835 radiographic studies, collected from 65,379 patients between 2011 and 2016 at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, MA, USA [2]. The dataset split consists of a training set (270,790 studies), a validation set (2130 studies), and a test set (3858 studies) [27]. Each study in the dataset is paired with a free-text radiology report written by board-certified radiologists. In accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Safe Harbor requirements, the dataset is completely de-identified to protect patient privacy. Because of its size, detailed content, and real-world clinical nature, this dataset has become a reference benchmark for vision–language research in radiology, particularly for report generation and visual question answering (VQA). An extension of MIMIC-CXR was later introduced to simplify image processing and labeling: MIMIC-CXR-JPG [28].

3.2. MIMIC-CXR-JPG

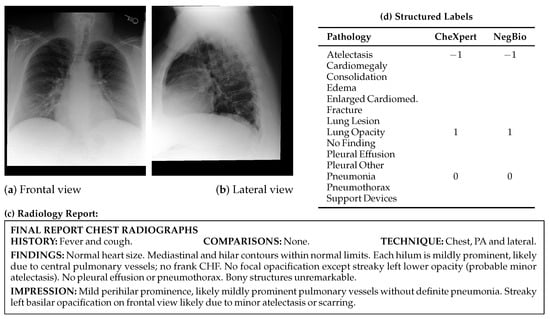

MIMIC-CXR-JPG [28,29] is a large-scale extension of MIMIC-CXR that provides 377,110 chest radiographs in JPG format, complemented with structured labels automatically extracted from 227,827 free-text radiology reports. All images are converted from DICOM format to JPG using a standardized process involving normalization, histogram equalization, and lossy compression with a quality factor of 95. Structured labels were automatically extracted from the original reports using two open-source NLP (Natural Language Processing) tools: CheXpert [20] and NegBio [30]. These labels include 14 categories, consisting of 13 pathologies such as cardiomegaly, pleural effusion, and pneumothorax, as well as the “No Finding” class. Custom Python 3.7 code was employed to identify and isolate the impressions, findings, or final sections of each report, from which labels were derived. MIMIC-CXR-JPG includes predefined training, validation, and test splits, along with metadata on view position, patient orientation, and acquisition time. The multi-modal data structure, which leverages both the free-text reports from MIMIC-CXR and the structured labels from MIMIC-CXR-JPG, is exemplified in Figure 2. It shows a single radiographic study in which the paired chest X-ray views (a,b) and the corresponding narrative report (c) originate from MIMIC-CXR, while the structured pathology labels (d) are automatically derived from the report using the tools provided in MIMIC-CXR-JPG.

Figure 2.

Illustrative example from the MIMIC-CXR dataset, including radiographic views (a) frontal and (b) lateral, (c) the corresponding full-text radiology report, and (d) structured pathology labels automatically extracted using the CheXpert and NegBio labelers from MIMIC-CXR-JPG. Label values: 1 = positive, 0 = negative, −1 = uncertain, and blank = not mentioned. “Cardiomed.” is an abbreviation for “Cardiomediastinum”.

3.3. IU X-Ray (Open-I)

The IU Chest X-ray Collection [21] is a publicly available dataset released by the U.S. National Library of Medicine. The dataset consists of 7470 frontal chest radiographs paired with 3955 de-identified radiology reports collected from two large hospital systems within the Indiana Network for Patient Care. Most reports include dedicated sections for findings, impressions, and the clinical indication for the exam. Reports were manually annotated with MeSH supplemented by RadLex [31] codes. Both DICOM and PNG versions of the images are provided. Despite its smaller scale compared to datasets like MIMIC-CXR, IU X-ray (Open-I) is frequently used due to its accessibility and real-world clinical content.

3.4. ChestX-Ray14 (NIH)

The NIH Chest X-ray dataset was first introduced as ChestX-ray8 [32]. It was later extended and re-released as ChestX-ray14, with more images and refined annotations to include six additional thoracic diseases [32]. The ChestX-ray14 dataset, collected between 1992 and 2015, consists of 112,120 frontal-view chest radiographs originating from 30,805 unique patients. The disease labels were automatically extracted from corresponding radiology reports using two automated NLP tools: MetaMap [33] and DNorm. The quality of these automated labels was validated on a subset of 900 reports that were manually annotated by two annotators [32]. Provided as 1024 × 1024 PNG files, each image is annotated with a maximum of 14 binary pathology labels. In contrast to datasets such as MIMIC-CXR or IU X-ray (Open-I), this collection does not provide the corresponding full-text radiology reports. However, no radiologist validation was performed on the full dataset, which makes its use as a benchmark potentially problematic [20].

3.5. CheXpert (Stanford)

The CheXpert dataset [20] comprises 224,316 chest radiographs from 65,240 patients, collected from Stanford Hospital between October 2002 and July 2017. Each study is annotated with labels for 14 observations, including common thoracic pathologies such as Cardiomegaly, Edema, and Pleural Effusion, in addition to a “No Finding” class. An automated, rule-based labeler was developed to extract observations from free-text radiology reports. Each mention of a finding as positive, negative, uncertain, or blank in the report is categorized by the labeler. The blank is assigned if a specific finding is not mentioned in the report. In an evaluation on a dedicated set of reports across multiple tasks, the CheXpert labeler outperformed the NIH labeler, achieving higher F1 scores [32]. This higher performance can be explained by its use of a three-phase pipeline to classify mentions and manage uncertainty in the reports. A validation and test set of 200 and 500 studies, respectively, are provided in the dataset. To establish a reliable ground-truth benchmark, the validation and test studies are manually annotated by 3 and 5 certified radiologists, respectively. The model trained on CheXpert surpassed at least two of three radiologists on four of five selected pathologies, showing higher diagnostic accuracy compared to the radiologists.

3.6. CheXpert Plus

The CheXpert Plus dataset [34] is an upgraded version of the original CheXpert dataset [20]. The dataset consists of 223,228 chest radiographs from 64,725 patients. Each image is annotated for 14 distinct clinical observations. It includes additional information, like DICOM images, radiology reports, patient demographics, and pathology labels. It contains a total of 36 million tokens, with 13 million tokens specifically from the impression sections of the reports. CheXpert Plus is the largest dataset for impression-level text-image tasks, surpassing MIMIC-CXR. Despite MIMIC-CXR containing 377,095 chest X-rays, the CheXpert Plus dataset provides a larger collection of text data, with a total of 36 million tokens versus MIMIC’s 34 million. Compared to the 8 million tokens in the impression sections found in MIMIC-CXR, CheXpert plus contains 13.4 million tokens.

3.7. PadChest

The PadChest dataset [35] is a publicly available dataset released in Alicante, Spain. The dataset includes 160,868 images from 67,625 patients, paired with 109,931 free-text radiology reports. The chest X-rays of this dataset were collected at the Hospital San Juan from 2009 to 2017. The dataset has six different types of projections and metadata on acquisition factors and patient demographics. Reports were annotated with 174 radiographic findings, 19 differential diagnoses, and 104 anatomical locations. The labels are structured in a hierarchical taxonomy and mapped to the Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) [35]. Trained physicians manually validated approximately 27% of the annotations, while the remainder were generated using a recurrent neural network with attention mechanisms. A micro-F1 score of 0.93 on an independent test set confirms the overall quality of the labels. Unlike other datasets, PadChest reports are written in Spanish, making it suitable for developing and testing models in multilingual settings.

3.8. PadChest-GR

PadChest-GR [36] extends the original PadChest dataset, facilitating research in grounded radiology report generation. The dataset contains 4555 bilingual chest X-ray studies (3099 abnormal and 1456 normal) in both Spanish and English, which makes the dataset suitable for multilingual training and evaluation. For each positive sentence, radiologists independently provided up to two sets of manual bounding-box annotations. These annotations also include categorical labels that describe the finding type, anatomical location, and progression. A key feature of this dataset is spatial grounding, where each clinical finding is linked to its precise location on the image. This level of detailed localization is largely absent from other public datasets. The spatial grounding provided by this dataset helps make report generation models more transparent and less prone to errors like hallucinations.

3.9. VinDr-CXR

Sourced from two of Vietnam’s largest hospitals: Hospital 108 (H108) and Hanoi Medical University Hospital (HMUH). VinDr-CXR [37] is a publicly available dataset of posteroanterior chest radiographs. The dataset has a training set of 15,000 images and a test set of 3000 images totaling 18,000 de-identified chest X-rays. To establish a high-quality benchmark, test set images were labeled by a consensus of five radiologists, a more rigorous process than the independent annotation by three radiologists used for the training set. Each image from the training set was annotated by three radiologists independently, while in the test set it is a consensus of five radiologists. The dataset provides both 6 global image-level diagnoses and 22 specific local abnormalities precisely annotated with bounding boxes. Images are provided in DICOM format, while their expert-generated annotations are distributed as structured CSV files. VinDr-CXR relies on manual annotations of expert radiologists, which are more trustworthy than NLP-based label extraction. In order to enhance the clinical accuracy of the final text, the combination of local and global labels makes the dataset valuable for pretraining report generation models.

3.10. Rad-ReStruct

Rad-ReStruct [38] was developed using the IU X-ray dataset and contains 3720 chest X-ray images paired with 3597 structured patient reports organized into a hierarchy of over 180,000 questions. MeSH and RadLex coded findings have been parsed into a multi-level template to construct each report. The template is composed of anatomical, pathological, and descriptive terms from a controlled vocabulary of 178 concepts. The dataset was partitioned using an 80%, 10%, and 10% split, representing the training, validation, and test sets, respectively. All images from a single patient were constrained to the same set in order to avoid data leakage [39].

3.11. FG-CXR

In the field of RRG (Radiology Report Generation) for chest X-rays, the interpretability of the models is one of the main challenges. To address this challenge, the FG-CXR [14] dataset has been developed, providing detailed annotations at the anatomical level instead of a full image with an entire report. The dataset consists of 2951 frontal chest X-rays. Each CXR is associated with gaze-tracking sequences from REFLACX [40] and EGDdatasets [41]. These gaze sequences are converted into both temporal coordinates and attention heatmaps. Region-specific findings, covering seven anatomical areas, such as the heart and the upper and lower lungs, are reported. These findings are either directly extracted from original reports or derived from MIMIC-CXR annotations. Multimodal annotations enable the development of gaze-supervised report generation frameworks, including Gen-XAI. The dataset is publicly available and includes predefined divisions for training, validation, and testing. Furthermore, the dataset incorporates additional data, comprising disease labels and anatomical segmentation masks.

Table 1.

Summary of public datasets used for radiology report generation.

Table 1.

Summary of public datasets used for radiology report generation.

| Dataset | Images | Reports | Labels | Data Type | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIMIC-CXR [19] | 377,110 | 227,835 | 14 1 | Free-text reports, DICOM images | PhysioNet |

| MIMIC-CXR-JPG [28] | 377,110 | – | 14 1 | JPG images, structured labels | PhysioNet |

| IU X-ray (Open-I) [21] | 7470 | 3955 | 189 [42] | Free-text reports, DICOM/PNG | Open-I |

| ChestX-ray14 [32] | 112,120 | – | 14 2 | PNG images, binary labels | NIH CC |

| CheXpert [20] | 224,316 | – | 14 3 | JPEG images, structured labels | Stanford AIMI |

| CheXpert Plus [34] | 223,228 | 187,711 | 14 3 | Free-text reports, DICOM images, structured labels | Stanford AIMI |

| PadChest [35] | 160,868 | 109,931 | 193 4 | Free-text reports (Spanish), DICOM images | BIMCV |

| PadChest-GR [36] | 4555 | 4555 | 24 | Bilingual reports, bounding boxes, spatial annotations | BIMCV |

| VinDr-CXR [37] | 18,000 | – | 22 | DICOM images, bounding boxes | PhysioNet |

| Rad-ReStruct [38] | 3720 | 3597 | 178 5 | PNG images, Structured reports, hierarchical QA pairs | GitHub |

| FG-CXR [14] | 2951 | – | 7 6 | Frontal chest X-ray, gaze-tracking, region findings | GitHub |

1 13 pathologies plus a “No Finding” class, automatically extracted from free-text reports using CheXpert and NegBio. 2 14 binary pathology labels automatically extracted using NLP tools (MetaMap, DNorm). Full-text reports are not provided. 3 14 observations extracted from reports using a rule-based labeler. Includes uncertainty labels and expert-labeled test sets. 4 Includes 174 radiographic findings and 19 differential diagnoses. 5 Comprises 178 terms categorized as anatomies, diseases, pathological signs, foreign objects, and attributes. 6 Seven anatomical regions with region-specific findings derived from MIMIC-CXR annotations and gaze-tracking data.

4. Evaluation Metrics

The problem of metric selection is very important in medical report generation. These metrics provide an evaluation of the quality of language and clinical accuracy of the generated reports. The evaluation metrics can be organized into three main families. First, Natural Language Generation (NLG) metrics such as BLEU, ROUGE, METEOR, and CIDEr are used to evaluate the surface-level lexical, semantic, and syntactic similarity between generated and reference reports. However, factual errors and clinical correctness cannot be detected by these metrics. Second, Clinical Efficacy (CE) metrics, including CheXbert-based scores, RadGraph F1, and GREEN, evaluate the correctness of medical content. These CE metrics provide a more reliable assessment of medical factuality by extracting and comparing pathology labels. Finally, to assess clinical utility, coherence, and error severity, which remain difficult to quantify automatically, human evaluations by expert radiologists and LLM-based evaluations are increasingly adopted. A robust evaluation protocol for radiology report generation requires combining these complementary metrics rather than relying on a single metric or family of metrics.

4.1. Natural Language Generation Metrics

These metrics assess the syntactic and semantic similarity between the generated report and the reference text, typically without explicitly considering clinical correctness. To assess the textual quality of generated reports, most studies adopt standard NLG metrics originally developed for tasks such as machine translation or summarization. Mathematical formulations for these metrics are provided in Appendix A. These include:

- Bilingual Evaluation Understudy (BLEU) [43]: BLEU is a widely adopted metric to evaluate the surface-level linguistic similarity of generated texts, particularly in medical report generation [23]. Originally developed for machine translation, BLEU measures the n-gram co-occurrence between generated and reference texts, which reflects the n-gram lexical overlap. As a result, BLEU tends to reward surface-level lexical similarity, leading to inflated scores for outputs that reuse reference wording, even when the clinical content is inaccurate. At the same time, it may penalize reports that are clinically accurate but use different wording because BLEU does not account for semantic or clinical correctness. This can lead to overestimating the quality of clinically incorrect outputs, and underestimating clinically valid findings expressed with alternative wording.

- Recall-Oriented Understudy for Gisting Evaluation (ROUGE) [44,45]: ROUGE, like BLEU, is a widely adopted family of evaluation metrics designed to assess the quality of generated texts by comparing them with reference texts [23]. In medical report generation, ROUGE is frequently used to quantify lexical overlap between model-generated and expert-written reports. Although ROUGE provides useful insight into lexical overlap, it does not account for semantic similarity or factual correctness, which is a major limitation in medical contexts. For instance, two clinically different findings (e.g., “no pneumothorax” vs. “pneumothorax present”) may share overlapping words but convey opposite clinical information. As noted in recent studies, high ROUGE scores do not necessarily reflect semantic or clinical correctness. Therefore, while ROUGE is commonly reported in medical report generation tasks, it is often complemented by domain-specific metrics that aim to capture clinical correctness more directly.

- Metric for Evaluation of Translation with Explicit ORdering (METEOR) [46,47]: METEOR was developed to address specific weaknesses identified in BLEU and ROUGE metrics by incorporating flexible matching strategies that are not limited to exact lexical matching, including stemmed forms, synonyms, and paraphrases [47]. METEOR demonstrates a stronger correlation with human judgment of adequacy and fluency in shared evaluation tasks [48] because of recall and flexible matching, which lowers lexical bias in favor of the exact matches. Nevertheless, its reliability in medical contexts remains limited, since it does not explicitly evaluate the clinical accuracy or factual correctness of the generated reports. Consequently, METEOR is often used in combination with domain-specific clinical metrics in medical report generation tasks.

Additional NLG metrics including CIDEr, BERTScore, and GLEU are described in Appendix B. These metrics are widely reported but are known to have limited correlation with clinical correctness, since they evaluate surface form similarity.

4.2. Clinical Efficacy Metrics

Given the limitations of text-only metrics, recent works increasingly evaluate models using clinically informed metrics. These are computed using the rule-based CheXpert labeler [20], its BERT-based successor CheXbert [17], or RadGraph [49], which extracts structured pathology labels from generated and reference reports. Specifically, the widely used Clinical Efficacy (CE) metrics, including precision, recall, and F1-score, are calculated for 14 pathologies, typically using the CheXbert labeler [17,50].

- RadGraph F1 [23,51]: RadGraph F1 is a recent automatic, clinically aware metric designed to evaluate radiology reports by computing the overlap in clinical entities and relations between a generated and a reference report. It relies on RadGraph [49], a clinical information extraction system that represents each report as a graph composed of labeled entities (findings, anatomical sites) and relations. RadGraph is trained on expert-annotated radiology reports and is specifically tailored to capture radiology-specific semantics.Two entities are matched if both their tokens and labels (entity type) match. Similarly, relations are matched if the relation type and their start and end entities match.This metric better captures the clinical correctness of radiology-specific content than traditional NLG metrics. Yu et al. [23] demonstrate that RadGraph F1 correlates more strongly with radiologist judgments than BLEU or CheXbert vector similarity, especially for identifying clinically significant errors. However, RadGraph F1 requires an accurate information extraction system and does not directly account for linguistic fluency or coherence.

- CheXbert Vector Similarity [17]: CheXbert vector similarity is an automatic clinical evaluation metric that assesses the alignment between a generated and a reference radiology report based on 14 predefined pathologies. It evaluates only the clinical content of reports without consideration for language fluency or coherence. For each report, the CheXbert model produces a 14-label vector using BioBERT [52], first fine-tuned on rule-based labels from CheXpert, then further fine-tuned on an expert-annotated set augmented via backtranslation. Each label corresponds to one of four classes: positive, negative, uncertain, or blank. For the evaluation, a 14-label vector [27,53] is extracted from the reference and the generated reports using the CheXbert labeler. This vector is then used to compute the following evaluation metrics, including precision, recall, and F1-score.

- GREEN Score [54,55]: Ostmeier et al. [54] introduced GREEN (Generative Radiology Report Evaluation and Error Notation) to handle the limitations of the actual metrics in measuring clinical correctness. The GREEN metric identifies and explains clinically significant errors by providing both quantitative and qualitative analysis in the generated reports. GREEN uses fine-tuned language models to detect and categorize six types of errors: false positives (hallucinations), omissions, localization errors, severity misassessments, irrelevant comparisons, and omitted comparisons. Unlike traditional lexical metrics, GREEN provides both a numerical score and a human-readable summary. This allows for an evaluation that is interpretable and clinically relevant. GREEN is a more reliable measure of clinical factuality because it correlates more strongly with radiologists’ error counts than existing metrics such as BLEU, ROUGE, and RadGraph F1.

- LC GREEN score [54,56]LC-GREEN (Length-Controlled GREEN) [56] was introduced to address the issue of verbosity bias in report generation. This bias can lead to an artificial overestimation of GREEN scores. As shown in the Equation (1), LC-GREEN has a length penalty.where is the length (in words) of the candidate report relative to the reference report. By penalizing reports that are too verbose, LC-GREEN offers a more robust evaluation of generated radiology reports.

4.3. Limitations and Human Evaluation

Despite these metrics, many studies still lack human evaluations by radiologists, which are critical for assessing factuality, coherence, and diagnostic utility. Few works perform expert scoring or error categorization, though these are crucial to ensure clinical deployment readiness.

Furthermore, metrics like BLEU or ROUGE may penalize medically correct but lexically diverse outputs. There is growing interest in aligning metrics with clinical needs (e.g., factual correctness, coverage of critical findings).

For instance, Lee et al. [57] also performed a human evaluation where three radiologists rated report acceptability on the following 4-point scale: (1) totally acceptable without any revision, (2) acceptable with minor revision, (3) acceptable with major revision, and (4) unacceptable. Based on this scale, they defined successful autonomous reporting as reports receiving a score of (1) or (2), and reported a success rate of 72.7 % for their CXR-LLaVA model.

4.4. LLM-Based Evaluation Protocols

Recent studies have introduced the use of large language models [55] (LLMs) such as GPT-3.5 for automatic evaluation of radiology report generation. Instead of comparing texts using lexical overlap, these models assess the semantic quality and factual coherence of generated reports via prompt-based role simulation. For instance, XrayGPT [22] uses GPT-3.5 Turbo to compare outputs from different models by asking which response is closer to the reference. This setup enables comparative evaluation based on clinical coherence and informativeness [22]. As such, they are typically used to complement, rather than replace, traditional metrics or expert-based evaluations.

5. Deep Learning-Based Report Generation Models

Deep learning models for generating radiology reports have evolved quickly. The field has progressed from classical encoder-decoder architectures to more advanced approaches that leverage alignment strategies, instruction tuning, and large vision–language models. This section provides an overview of representative approaches, grouping them by their primary methodological innovations. These include prompt- and knowledge-augmented, memory-enhanced, anatomically guided, Multi-View and longitudinally guided, transformer-based, and joint image-text generation models. We also cover more recent advancements, like conversational LVLMs, expert-guided models, and unified multimodal models. To complement this overview, the key features, datasets, and results of these models are summarized in Table 2 and Table 3.

5.1. Encoder-Decoder Architectures

Encoder-decoder models are still a key part of many systems used to generate medical reports today. First, the encoder processes chest X-rays to extract their spatial features. The decoder then generates a report based on these extracted visual features. While building on this framework, recent models also incorporate structural and clinical enhancements. Table 2 summarizes the architectures, innovations, and performance metrics of encoder-decoder models across different datasets.

5.1.1. Prompt- and Knowledge-Augmented Models

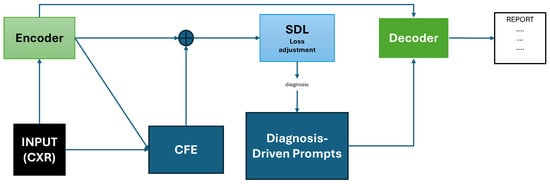

For instance, PromptMRG employs an ImageNet-pretrained ResNet-101 encoder, a BERT-base decoder [58], and three auxiliary modules: Diagnosis-Driven Prompts (DDP), Cross-Modal Feature Enhancement (CFE), and Self-adaptive Disease-balanced Learning (SDL) [27] (Figure 3). Specifically, a disease classification module operates in parallel with the encoder and outputs diagnostic labels for each pathology. These labels are converted into token-level prompts ([BLA], [POS], [NEG], and [UNC], which represent absent, positive, negative, or uncertain findings, respectively). The symbolic prompts are prepended to the decoder input sequence and learned jointly during training. Each prompt corresponds to one disease (specific pathology category) and guides the report generation of the language model toward clinically consistent output. The model also introduces a cross-modal retrieval module that uses CLIP-based embeddings to fetch similar reports and augment the classification branch and employs self-adaptive logit-adjusted loss [59] to compensate for the decoder’s inability to control disease distributions and to mitigate class imbalance during training. The decoder leverages both visual features and diagnostic prompts to generate reports that are more clinically accurate. When evaluated using the CheXpert labeler on the official MIMIC-CXR [19] test split, PromptMRG reaches CE-Precision 0.501, CE-Recall 0.509, and CE-F1 0.476, with BLEU-4 0.112, ROUGE-L 0.268, and METEOR 0.157. When evaluated on the IU X-ray (Open-I) [21] dataset, it obtains CE-Precision 0.213, CE-Recall 0.229, CE-F1 0.211, BLEU-4 0.098, ROUGE-L 0.281, and METEOR 0.160.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the PromptMRG [27] architecture adapted from Jin et al. The model includes an encoder producing visual features, a parallel classification branch with CFE (which retrieves similar reports via CLIP embeddings), Diagnosis-Driven Prompts (DDP) guiding the decoder, and Self-Adaptive Disease-balanced Learning (SDL) applied on the classification loss. Prompts and visual features are combined in the decoder to generate clinically accurate reports.

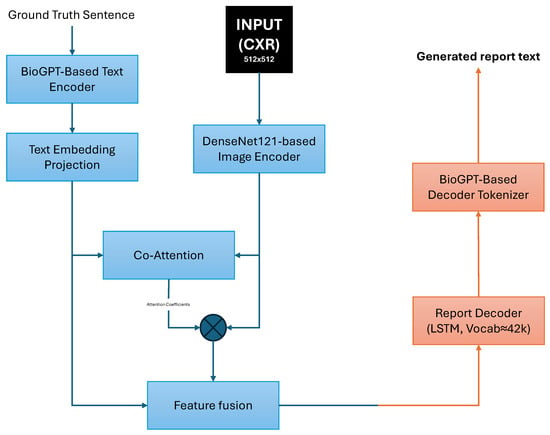

ChestBioX-Gen [60] is a CNN-RNN encoder-decoder designed for radiology report generation from chest X-ray images. The encoder uses the CheXNet model [61] (DenseNet121) to extract visual features from each image. To improve report coherence and clinical specificity, ChestBioX-Gen employs a co-attention mechanism to align visual regions of interest with textual embeddings produced by BioGPT [62], a language model pretrained on 15 million PubMed abstracts. When evaluated on the IU X-ray dataset, the model achieved BLEU-1, BLEU-2, BLEU-3, BLEU-4, and ROUGE-L scores of 0.6685, 0.6247, 0.5689, 0.4806, and 0.7742, respectively. However, to further improve performance, the authors suggest exploring transformer-based decoders and validation on larger datasets such as MIMIC-CXR. The architecture of ChestBioX-Gen is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

ChestBioX-Gen architecture overview. Visual features from a DenseNet121-based encoder and text embeddings from a BioGPT-based encoder are aligned via co-attention. The fused features are passed to an RNN decoder to generate the radiology report text.

Another approach to knowledge augmentation is proposed by He et al. [63], who introduce a framework that leverages keywords extracted from existing radiology reports to guide report generation. First, relevant keywords are predicted from chest X-ray images by a ConvNeXt multi-label classification network. Subsequently, based on these predicted words, a Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer (T5) generates the radiology report. This method adapts medical knowledge from existing reports to align the keyword setting with ground truth clinical scenarios. The predicted keywords serve as prompts to filter non-related information and guide the pre-trained language model toward generating more clinically relevant reports. The model achieves BLEU-1, BLEU-2, and BLEU-3 scores of 0.627, 0.516, and 0.440, respectively, on IU X-ray and 0.462, 0.335, and 0.257 on MIMIC-CXR.

Another framework that uses a cross-modal attention mechanism has been proposed by Li et al. [64]. It is context-enhanced and integrates clinical text context, including comparison, the reason for the examination and clinical history. The model employs a multi-label classification to identify relevant medical knowledge (14 CheXpert diseases + 100 extracted medical terms), which are then embedded to guide report generation. GPT-4 improves generated reports by incorporating the findings of a disease diagnosis. On the MIMIC-CXR dataset, the model achieved BLEU-1, BLEU-2, BLEU-3, and BLEU-4 scores of 0.411, 0.284, 0.195, and 0.138, respectively, with a ROUGE-L of 0.312 and a clinical efficacy F1 score of 0.431.

5.1.2. Memory-Enhanced and Anatomically-Guided Models

This group of models integrates significant enhancements, including relational memory for long-range coherence (AERMNet), hierarchical anatomical knowledge (HKRG), and gaze-guided supervision (Gen-XAI). AERMNet, an encoder-decoder architecture, was proposed by Zeng et al. [13] to enhance word correlation and contextual representation for medical report generation. A common issue with current models is their weak word correlation and poor contextual representation, which reduce the accuracy of the generated reports. AERMNet improves upon the AOANet baseline [65] through the addition of a dual-layer LSTM decoder, based on the Mogrifier LSTM [66]. It also includes an attention-enhanced relational memory module to better capture long-term dependencies between words. The chest X-ray features are extracted using a ResNet101 [67] pretrained on ImageNet [68]. The relational memory module is continually updated, which strengthens the correlation between the generated words. AERMNet showed higher performance than some existing models after being trained on four datasets. These include IU X-ray, MIMIC-CXR, fetal heart ultrasound, and an ultrasound dataset collected in collaboration with a hospital in Chongqing.

On the MIMIC-CXR dataset, AERMNet achieved scores of BLEU-1 = 0.273, BLEU-4 = 0.169, METEOR = 0.157, ROUGE-L = 0.232, and CIDEr = 0.253.

Another novel approach is the HKRG (Hierarchical Knowledge Radiology Generator) with its hierarchical reasoning structure. The model uses a multi-level framework to associate features in a CXR to a specific anatomical part and clinical knowledge [12]. HKRG operates in two distinct stages: first, a vision–language pretraining stage, followed by a report generation stage. To encode images, the model uses a Swin Transformer [69], and a knowledge-enhanced BERT [70] (KEBERT) for text encoding. A cross-modal attention mechanism is integrated to combine the visual and textual features. This combination is then decoded by a 12-layer Transformer decoder. This structure mimics how radiologists interpret images by systematically integrating knowledge of organs and pathologies. The model is optimized with a multi-task loss function. This function combines three objectives: masked image modeling, masked language modeling, and a contrastive loss. The HKRG model was evaluated on the IU X-ray and MIMIC-CXR datasets. On the IU X-ray dataset, the model outperformed the previous SOTA, achieving scores of 0.538 (BLEU-1), 0.213 (BLEU-4), 0.244 (METEOR), and 0.418 (ROUGE-L). On the larger MIMIC-CXR dataset, its performance was highly competitive, with scores of 0.417, 0.143, 0.167, and 0.310 for the same metrics, though it did not surpass the SOTA on all of them. This approach provides two main benefits: it significantly improves anatomical precision and reduces overgeneralization. However, its performance depends on the quality and completeness of the external knowledge bases used during training. We have included the HKRG model in the category of anatomically-guided models, even though it uses a transformer-based encoder-decoder structure. This is due to its primary contribution, which involves the hierarchical integration of information about organs and diseases.

Also, to enhance the interpretability of RRG, Pham et al. developed Gen-XAI [14]. It is a gaze-supervised encoder-decoder model based on the FG-CXR dataset. The model uses eye-tracking heatmaps and region-level textual findings as supervision signals. This design choice promotes explainable visual-textual alignment. Gen-XAI has three main components. To align with radiologist fixations, a Gaze Attention Predictor generates anatomical attention maps. The heatmaps predicted for each anatomical region are then used by a Spatial-Aware Attended Encoder to modify image features. Finally, a GPT-2-based [71] decoder produces a single sentence for each anatomical region. The model mimics the visual interpretation of anatomical areas of the radiologists by constraining specific regions. Gen-XAI outperforms the state-of-the-art (SOTA) in both clinical efficacy and Natural Language Generation (NLG) metrics. On the FG-CXR test set, its scores are BLEU-4 = 0.561, METEOR = 0.386, ROUGE-L = 0.692, CIDEr = 4.026, and F1-micro = 0.497. Another quality of the model is that it offers a region-level visual explanation.

In addition to anatomical or memory-guided methods, a new line of work leverages temporal and multi-view information to capture disease progression, which better reflects clinical workflows.

5.1.3. Multi-View and Longitudinally Guided Models

The MLRG (Multi-view Longitudinal Report Generation) [16] model was proposed by Liu et al. to address the limitations of single-image and dual-view methods. The model operates in two stages. The first stage involves a multi-view longitudinal contrastive learning framework. It includes spatiotemporal information from radiology reports. In the second stage, the missing patient-specific knowledge is managed by a tokenized absence encoding mechanism. This stage lets the generator flexibly use the available context. MLRG uses RAD-DINO [72] for vision encoding, a CXR-BERT [73] for text encoding, and a DistilGPT2-based text generator [74]. These visual and textual representations are then correlated with a multi-view longitudinal fusion network. MLRG achieves BLEU-4, ROUGE-L, RadGraph F1, and F1 scores of: 0.158, 0.320, 0.291, and 0.505 on MIMIC-CXR [2], 0.094, 0.248, 0.219, and 0.515 on MIMIC-ABN [75], and 0.154, 0.331, 0.328, and 0.501 on two-view CXR [76]. With these scores, this model outperforms prior SOTA models on all three datasets. By incorporating multi-view and longitudinal data, the model can better mimic the workflow of radiologists and generate more clinically accurate reports.

5.1.4. Transformer-Based Encoder-Decoder

CheXReport [8] architecture was designed for radiology report generation from chest X-ray images. It relies entirely on transformers. CLAHE [77] is used to pre-process the CXR images before resizing them to 224 × 224 pixels. Afterward, the local and global visual features of the input image are extracted using pretrained Swin-T, Swin-S, and Swin-B model blocks in the encoder. These features are then projected into a 256-dimensional visual embedding space. To combine the visual and textual features, GloVe [78] word embeddings and Swin Transformer blocks are integrated into the decoder. Using a beam search, the decoder suggests reports with a beam of 5. On the MIMIC-CXR dataset, the model achieved scores of 0.127, 0.286, 0.147, and 0.130 on BLEU-4, ROUGE-L, METEOR, and GLEU. CheXReport outperforms the SOTA on BLEU-4 and ROUGE-L scores. However, CheXReport does not appear to incorporate anatomical priors, disease-specific prompts, or structured medical knowledge. Furthermore, its performance is not assessed using clinical factuality metrics, such as CheXbert or RadGraph. Unlike traditional CNN-RNN methods, CheXReport uses a pure transformer-based encoder-decoder architecture. This demonstrates the effectiveness of vision–language transformer architectures for generating radiology reports.

5.1.5. Multi-Modal Data Fusion Models

Beyond visual information, a novel approach proposed by Aksoy et al. [79] uses unstructured clinical notes and structured patient data, such as oxygen saturation, acuity level, blood pressure, and temperature, in addition to chest X-ray images. Another novelty is the conditioned cross-multi-head attention module, which fuses these different data modalities. The framework uses an EfficientNetB0 CNN as an encoder and a transformer architecture with cross-attention mechanisms to generate reports conditioned on all the available patient information. The dataset used for training and evaluation was created by combining the MIMIC-CXR, MIMIC-IV, and MIMIC-IV-ED datasets. On this combined dataset, the model achieved scores of 0.351, 0.231, 0.162, and 0.107 on BLEU-1, BLEU-2, BLEU-3, and BLEU-4 metrics, respectively, and a ROUGE-L score of 0.331. The model’s factual accuracy was evaluated by a board-certified radiologist. The model got a score of 4.24/5 for language fluency, 4.12/5 for content selection and 3.89/5 for correctness and abnormal findings confirming the performance but highlighting the need for improvement.

Table 2.

Summary of Encoder-Decoder Architectures for chest X-ray report generation. metrics abbreviated: CE-F1 stands for Clinical Efficacy-F1, RG-F1 indicates RadGraph-F1. Hum. corresponds to human evaluation.

Table 2.

Summary of Encoder-Decoder Architectures for chest X-ray report generation. metrics abbreviated: CE-F1 stands for Clinical Efficacy-F1, RG-F1 indicates RadGraph-F1. Hum. corresponds to human evaluation.

| Model | Category | Key Innovation | Dataset | BLEU-4 | ROUGE-L | METEOR | CIDER | CE-F1 | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PromptMRG [27] | Prompt/Knowledge | Diagnosis-driven | MIMIC-CXR | 0.112 | 0.268 | 0.157 | - | 0.476 | - |

| prompts, CFE | IU X-ray | 0.098 | 0.281 | 0.160 | - | 0.211 | - | ||

| ChestBioX-Gen [60] | Prompt/Knowledge | BioGPT co-attention | IU X-ray | 0.481 | 0.774 | 0.189 | 0.416 | - | - |

| AERMNet [13] | Memory-Enhanced | Relational memory, Mogrifier LSTM | MIMIC-CXR | 0.090 | 0.232 | 0.157 | 0.253 | - | - |

| IU X-ray | 0.183 | 0.398 | 0.219 | 0.560 | - | - | |||

| HKRG [12] | Anatomy-Guided | Hierarchical anatomical knowledge | IU X-ray | 0.213 | 0.418 | 0.244 | - | - | - |

| MIMIC-CXR | 0.143 | 0.310 | 0.167 | - | 0.339 | - | |||

| Gen-XAI [14] | Anatomy-Guided | Gaze supervision, eye-tracking | FG-CXR | 0.561 | 0.692 | 0.386 | 4.026 | 0.497 | - |

| MLRG [16] | Multi-View/Long. | Spatiotemporal contrastive learning | MIMIC-CXR | 0.158 | 0.320 | 0.176 | - | 0.505 | RG-F1 = 0.291 |

| MIMIC-ABN | 0.094 | 0.248 | 0.136 | - | 0.515 | RG-F1 = 0.219 | |||

| Two-view CXR | 0.154 | 0.331 | 0.178 | - | 0.501 | RG-F1 = 0.328 | |||

| CheXReport [8] | Pure Transformer | Swin Transformer encoder-decoder | MIMIC-CXR | 0.127 | 0.286 | 0.147 | - | - | GLEU = 0.130 |

| He et al. (2024) [63] | Prompt/Knowledge | Keywords extraction + Multi-label filtering | IU X-ray | - | - | - | - | - | B-1 = 0.627 |

| - | - | - | - | - | B-2 = 0.516 | ||||

| MIMIC-CXR | - | - | - | - | - | B-1 = 0.462 | |||

| - | - | - | - | - | B-2 = 0.335 | ||||

| Aksoy et al. (2024) [79] | Multi-Modal Fusion | Cross-attention fusion of clinical data | combined dataset | 0.107 | 0.331 | - | - | - | Hum. eval. |

| Context-Enhanced Framework [64] | Prompt/Knowledge | Clinical text fusion + Knowledge embedding + LLM refinement | IU X-ray | 0.209 | 0.408 | 0.212 | 0.396 | - | - |

| MIMIC-CXR | 0.138 | 0.312 | 0.203 | 0.195 | 0.431 | - |

5.2. Joint Image-Text Generation

CXR-IRGen [80] adopts a modularized structure with a vision module and a language module that jointly generates the chest X-ray radiology reports and images. The vision module is based on a latent diffusion model [81] (LDM). This conditioning strategy improves the clinical realism and diagnostic relevance of the generated images. The authors demonstrate that using the reference image improves the image quality (Fréchet Inception Distance [82], Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio, and Structural Similarity Index [83]), and increases diagnostic performance (AUROC) by about 1.84 %. The language module generates the reports using a two-stage CXR report generation method. First, a pretrained LLM (BART [84]) with an encoder-decoder architecture encodes the text into a sequence of text embeddings and then reconstructs the report from the average value of all text embeddings. Then, a prior model aligns the image and text by projecting image embeddings into the text embedding space, optimized using a joint loss combining cosine similarity and Mean Squared Error (MSE), thereby ensuring that the report aligns with the image content. Furthermore, CXR-IRGen integrates reference image embeddings into its vision module prompts to improve the clinical relevance of generated reports. However, this approach risks overfitting, as shown by abnormally high classification scores (AUROC) compared to real clinical data. Instead of using raw images as input, CXR-IRGen formats CheXpert-style disease labels into textual prompts, which are then used to condition the generation of both synthetic chest X-ray images and corresponding reports. This method combines the benefits of both image captioning and retrieval-based methods [85].

5.3. Large Vision–Language Models for Radiology

This section reviews recent large multimodal models specifically designed for chest X-ray interpretation, which often rely on encoder-decoder principles but extend them through vision–language alignment and instruction-tuned LLMs. Table 3 provides a comprehensive comparison of LVLM architectures and their performance across clinical and lexical metrics.

5.3.1. Task-Specific Models for Chest X-Ray

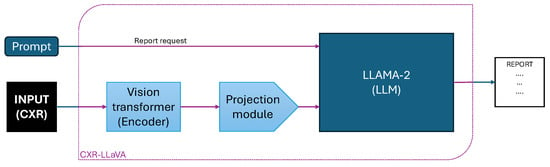

The CXR-LLaVA [57] represents a specialized open-source vision–language model designed for chest X-ray interpretation. Its architecture is influenced by the LLaVA network [86] and integrates two core components, as shown in Figure 5: a Vision Transformer (ViT-L/16) as the visual encoder and a LLaMA-2-7B [87] language model. The model is trained using a two-stage methodology, which involves visual encoder pretraining and then vision–language alignment. In the initial training stage, the visual encoder is pretrained on 374,881 image-label pairs from a public chest X-ray dataset. Then, the model uses 217,699 image-report pairs from MIMIC-CXR to perform feature alignment between the visual and textual modalities. For instruction tuning, the authors generated question answering and multi-turn dialogue samples from MIMIC-CXR reports via the GPT-4 model. During evaluation, CXR-LLaVA surpassed general-purpose models such as GPT-4-vision [88] and Gemini-Pro-Vision on multiple benchmarks, achieving an F1-score of 0.81 on MIMIC-CXR, 0.57 on CheXpert, and 0.56 on the Indiana external test set. The model demonstrates high efficacy for frequently encountered findings such as edema and cardiomegaly. In contrast, it exhibits poor performance for pneumothorax, with an F1-score of 0.05. The quality of the generated reports was evaluated through a human study, where a panel of three board-certified radiologists rated each report on a 4-point scale. Reports with scores of 1 (fully acceptable) or 2 (minor revisions) were considered successful, leading to a 72.7 % success rate for CXR-LLaVA.

Figure 5.

Schematic overview of the CXR-LLaVA architecture. The model uses a Vision Transformer encoder to process the chest X-ray image, a projection module to align visual features, and an LLM (LLaMA-2) that integrates the prompt request and visual embeddings to generate the final radiology report.

5.3.2. Conversational and Interactive Models

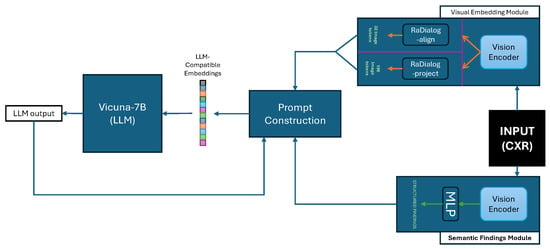

RaDialog is a dual-branch large vision–language model developed for chest X-ray report generation and conversational clinical assistance. The architecture is composed of a visual feature extractor and a structured findings extractor, as illustrated in Figure 6. Their outputs are combined within a prompt construction module to query the Vicuna-7B large language model [89], which was fine-tuned via LoRA [90]. Functionally, RaDialog includes two task-specific variants: RaDialog-align uses a BERT-based alignment module to convert visual embeddings into 32 LLM-compatible tokens, while RaDialog-project employs a direct projection of 196 image tokens via an MLP adapter. RaDialog includes two training configurations: RaDialog-rep is trained on the MIMIC-CXR dataset for report generation only, while RaDialog-ins is fine-tuned using RaDialog-Instruct, a large instruction tuning dataset comprising ten tasks such as report generation, correction, simplification, and region-grounded question answering. RaDialog-Instruct includes both real and pseudo-labeled data, and training incorporates context-dropping augmentation to enhance robustness. On MIMIC-CXR, RaDialog achieves a clinical efficacy score of 39.7 and a BERTScore of 0.40, outperforming prior medical LVLMs like CheXagent and R2GenGPT. In addition, RaDialog was preferred by radiologists in 84% of cases for report generation and 71% for conversational performance in human evaluation.

Figure 6.

Overview of the RaDialog architecture. Chest X-ray images are processed through a Visual Embedding Module, followed by either the RaDialog-align or RaDialog-project path. Simultaneously, semantic findings are extracted via a Semantic Findings Module. Both branches are merged in the Prompt Construction block to generate input sequences for the Vicuna-7B LLM, which produces the final report or dialog response.

Recent research introduces another conversational VLM that summarizes chest X-ray reports named XrayGPT [22]. The model involves a Vicuna-based LLM and a medical image encoder (MedCLIP [9]), which are aligned by a lightweight transformation layer. This alignment allows joint vision–language learning. The model is trained in two stages. First, 213,514 image-report pairs from MIMIC-CXR [19] are used for training, and then 3000 high-quality summaries from the IU X-ray (Open-I) dataset [21] are used for fine-tuning. During the preprocessing of the summaries, GPT-3.5 Turbo is used to remove incomplete phrases, historical comparisons, and technical metadata. A specific prompt schema is followed in order to simulate a medical dialogue for multiple radiological tasks. XrayGPT achieved scores of 0.3213, 0.0912, and 0.1997 for ROUGE-1, ROUGE-2, and ROUGE-L, respectively. It outperforms the MiniGPT-4 baseline by 19% in the ROUGE-1 score. An automatic comparison using GPT-3.5 Turbo showed that XrayGPT was preferred in 82% of the cases compared to 6% for the baseline. 72% of the generated reports by the model were judged as factually accurate by certified medical doctors, with an average score of 4 out of 5. In comparison, the baseline got only 20% factual accuracy with an average score of 2 out of 5. The authors noted that one of the limitations is that the performance is lower on lateral views, probably because of the dominance of frontal images in the training data. XrayGPT demonstrates that vision–language alignment and LLM-based simulation of clinical dialogue can enhance the coherence and reliability of radiology report generation.

RadVLM [91] is a compact multitask conversational vision–language model designed for interpreting chest X-rays. Based on the LLaVA-OneVision-7B backbone [92], the model combines a SigLIP vision encoder [93] with a Qwen2 language model [94], linked by a two-layer MLP adapter. To enhance representation quality, the model encodes multiple patches of the input image at various resolutions, including the full image, using the Higher AnyRes strategy [95]. These patches are then concatenated before being processed by the language model. The vision encoder, adapter, and language model are all jointly fine-tuned end-to-end using the curated instruction dataset. With a dataset of more than one million image-instruction pairs, the model was trained to perform tasks, including report generation, abnormality classification, visual grounding, and multi-turn conversational interactions. The dataset for the report generation task comprises 232,344 image-report pairs from MIMIC-CXR and 178,368 pairs from CheXpert Plus. The generated reports were evaluated using both lexical metrics (BERTScore and ROUGE-L) and clinical metrics (RadGraph F1 and GREEN). Using the MIMIC-CXR test set, RadVLM achieved the best lexical results with a BERTScore of 51.0 and a ROUGE-L of 24.3, while also scoring 17.7 on RadGraph F1 and 24.9 on GREEN. While RadVLM outperforms baseline models like RaDialog and MAIRA-2 [96] on both lexical and clinical metrics, CheXagent maintains a lead in clinical correctness.

5.3.3. Expert-Guided Models

Recent research introduces VILA-M3 [15] as a novel method that uses expert-guided mechanisms. It is designed in a four-stage scheme: (1) vision encoder pretraining, (2) vision-language pretraining, (3) instruction fine-tuning (IFT), and (4) a specialized IFT stage that injects outputs from medical expert models. The innovation of this architecture is that VILA-M3 can activate external expert models during inference. This technique, which is not used in previous models such as Med-Gemini [97], improves model reasoning by using the expert models’ outputs. For segmentation, MONAI-BraTS [98] and VISTA3D [99] tools are used, and for chest X-ray classification, TorchXRayVision [100] is used. Conversational prompts are made from the outputs of the expert models, which are used by VILA-M3 to refine its generated text with structured clinical information. On different tasks, including classification on CheXpert, RRG on MIMIC-CXR, and multiple VQA datasets, VILA-M3 outperforms the previous SOTA Med-Gemini by nearly 9%. In the RRG task on MIMIC-CXR, the model shows a BLEU-4 score of 21.6 where Med-Gemini achieves only 20.5. The F1 score for the classification task on CheXpert is 61.0 versus 48.3. VILA-M3 achieved an average score of 64.3, outperforming Med-Gemini’s 55.7. The clinical accuracy improvement is partly due to the guidance of the VLMs by the clinical signals from expert models. Finally, ablation studies confirm that the model’s performance is improved by both expert-model prompts and domain-aligned instruction tuning. These results demonstrate that the combination of modular expert components with instruction-tuned LLMs improves the clinical accuracy of RRG models.

5.3.4. Multi-Stage Vision–Language Models

The first large-scale benchmark created using the CheXpert Plus dataset [34] is CXPMRG-Bench [10]. It investigates 19 report generation algorithms, with 14 LLMs and 2 VLMs. Various pre-training strategies have been followed, including supervised fine-tuning, self-supervised autoregressive generation and contrastive learning for X-ray and report pairs. First, chest X-ray scans are divided into patches, which are then processed using autoregressive generation by a vision model based on Mamba. This improves perception efficiency with complexity. The second step involves aligning image and report pairs using contrastive learning. For this, the model uses language encoders such as Bio-ClinicalBERT [101] or LLaMA2 [87]. In the final stage, the model undergoes supervised fine-tuning using downstream datasets and is then evaluated on the IU X-ray, MIMIC-CXR, and CheXpert Plus datasets. The large variant, MambaXray-VL-L, achieved SOTA results on CheXpert Plus. It achieved 0.112 on BLEU-4, 0.276 on ROUGE-L, 0.157 on METEOR, 0.139 on CIDEr, 0.377 on precision, 0.319 on recall, and 0.335 on F1.

5.3.5. Unified Medical Vision–Language Models

Unlike prior LVLMs in radiology that mainly focus on specific tasks, such as report generation or VQA, HealthGPT is introduced as the first unified medical LVLM capable of addressing both multimodal comprehension and generation across diverse medical tasks via H-LoRA, HVP, and a three-stage learning strategy (TLS). This training method separates the tasks of understanding and creating information to avoid task conflict and improve efficiency. HealthGPT adopts the LLaVA architecture [102] for its simplicity and portability. It integrates CLIP-L/14 [103] to extract visual features, and subsequently combines shallow (concrete) and deep (abstract) features with alignment adapters. Furthermore, three variants were developed: HealthGPT-M3, HealthGPT-L14, and HealthGPT-XL32, which are based on Phi-3-mini (3.8 B) [104], Phi-4 (14 B) [105], and Qwen2.5-32B (32 B), respectively. The vocabulary was expanded with 8192 VQ indices derived from VQGAN-f8-8192 [106], serving as multi-modal tokens. The model was trained on VL-Health, a dataset curated by the authors to unify seven comprehension and five generation tasks. It includes medical VQA datasets like VQA-RAD [107], SLAKE [108], PathVQA [109], MIMIC-CXR-VQA [110], LLaVA-Med [86], and PubMedVision [111]. It also integrates generation datasets, specifically MIMIC-CXR for text-to-image, IXI [112] for super-resolution, SynthRAD2023 [113] for modality conversion, and LLaVA-558k [114] for image reconstruction. The evaluation was limited to comprehension and generation tasks, excluding radiology report generation metrics. Experimental results nevertheless demonstrated performance gains compared to the SOTA.

Table 3.

Summary of Large Vision–Language Models (LVLMs) for chest X-ray report generation. metrics abbreviated: CE-F1 stands for Clinical Efficacy-F1, RG-F1 indicates RadGraph-F1, Hum. corresponds to human evaluation.

Table 3.

Summary of Large Vision–Language Models (LVLMs) for chest X-ray report generation. metrics abbreviated: CE-F1 stands for Clinical Efficacy-F1, RG-F1 indicates RadGraph-F1, Hum. corresponds to human evaluation.

| Model | Category | Base LLM | Vision Enc. | Dataset | BLEU-4 | ROULE-L | BERTScore | CE-F1 | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CXR-LLaVA [57] | Task-Specific | LLaMA-2-7B | ViT-L/16 | MIMIC-CXR | - | - | - | 0.81 | - |

| CheXpert | - | - | - | 0.57 | - | ||||

| IU X-ray | - | - | - | 0.56 | Hum. = 72.7% | ||||

| RaDialog-align [39] | Conversational | Vicuna-7B | BERT-based | MIMIC-CXR | 0.097 | 0.271 | 0.40 | 0.394 | - |

| IU X-ray | 0.102 | 0.310 | 0.47 | 0.226 | - | ||||

| RaDialog-project [39] | Conversational | Vicuna-7B | MLP adapter | MIMIC-CXR | 0.094 | 0.267 | 0.36 | 0.397 | - |

| IU X-ray | 0.110 | 0.304 | 0.45 | 0.231 | - | ||||

| XrayGPT [22] | Conversational | Vicuna | MedCLIP | MIMIC-CXR | - | 0.200 | - | - | R-1 = 0.321 Hum. = 72% |

| RadVLM [91] | Conversational | Qwen2 | SigLIP | MIMIC-CXR | - | 0.243 | 0.510 | - | RG-F1 = 0.177 GREEN = 0.249 |

| VILA-M3 [15] | Expert-Guided | - | - | MIMIC-CXR | 0.216 | 0.322 | - | - | GREEN = 0.392 |

| CheXpert | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| MambaXray-VL-L [10] | Multi-Stage | - | Mamba-based | CheXpert Plus | 0.112 | 0.276 | - | 0.335 | METEOR = 0.157 CIDEr = 0.139 |

| MambaXray-VL-B [10] | Multi-Stage | - | Mamba-based | CheXpert Plus | 0.105 | 0.267 | - | 0.273 | METEOR = 0.149 CIDEr = 0.117 |

| HealthGPT [115] | Unified | Phi-3/4, Qwen2.5 | CLIP-L/14 | Multi-datasets | - | - | - | - | Multimodal comprehension + generation |

5.4. Critical Analysis and Performance Comparison

A comparison of architectures for chest X-ray radiology report generation based on clinical metrics shows clear performance patterns.

First, MLRG [16] shows strong clinical performance with a CE-F1 of 0.505 on MIMIC-CXR, outperforming encoder-decoder baselines like PromptMRG [27] (CE-F1 = 0.476). This suggests that multi-view and longitudinally-guided models improve factual accuracy compared to the other encoder-decoder architectures by incorporating temporal information and multiple views.

Second, some models are difficult to compare due to their evaluation on NLG metrics only. For example, ChestBioX-Gen [60] achieves high scores of BLEU-4 (0.481) and ROUGE-L (0.774) on IU X-ray. Similarly, CheXReport [8] reports competitive lexical scores but lacks clinical efficacy metrics, which makes it difficult to evaluate the clinical accuracy and utility of these models. The NLG metric scores do not always correlate with clinical accuracy, and hallucinations and clinical errors are not often detected by these metrics.

Finally, large vision–language models show competitive performance on clinical efficacy metrics. CXR-LLaVA [57] achieves CE-F1 = 0.81 on MIMIC-CXR but only 0.57 and 0.56 on CheXpert and IU X-ray datasets, while RadVLM [91] achieves BERTScore = 0.510. These models show variable performance across different clinical tasks and datasets.

This analysis shows that clinical accuracy is highly impacted by architectural choices. Models with clinical grounding—through multi-view information, longitudinal data, or anatomical knowledge outperform standard encoder-decoder architectures on clinical metrics. However, future work should prioritize a unified evaluation protocol for both NLG and clinical correctness for a better comparison between architectures.

6. Methodologies for Factuality and Domain Adaptation

In addition to the core model architectures reviewed in the previous sections, certain methodological strategies have been proposed to improve factual accuracy and domain adaptation in radiology report generation.

These techniques are model-agnostic and can be integrated into diverse frameworks, including encoder-decoder systems, joint image-text generation pipelines, and large vision–language models.

6.1. RULE: A Retrieval-Augmented Generation Framework

One emerging strategy for enhancing the factual consistency of radiology report generation involves retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) frameworks, as demonstrated by RULE [116]. To minimize hallucinations, RULE uses image features and textual prompts to retrieve pertinent radiology reports with its multimodal RAG architecture. The system’s final report is guided by the external knowledge from these retrieved reports. Even with its performance on NLG metrics showing that the method is promising for reducing lexical inconsistencies, its clinical reliability remains difficult to quantify, since its evaluation lacks domain-specific metrics such as CheXbert or RadGraph. Integrating retrieval-based mechanisms with clinically grounded supervision can be a reliable approach for increasing the factuality and quality of RRG. RULE adopts a retrieval method without relying on fine-grained visual grounding or anatomical supervision. The combination of clinical supervision and retrieval-augmented frameworks can be a promising path for further future improvements.

6.2. Bootstrapping General LLMs to RRG

The adaptation of general-domain large language models to the medical domain remains a persistent challenge in RRG. A method proposed by Liu et al. [11] to address this challenge is bootstrapping LLMs specifically for this task. Coarse-to-fine decoding (C2FD) and in-domain instance induction (I3) are combined in this approach. Contrastive semantic ranking and related instance retrieval are used to adapt the LLM during the induction phase. Related instance retrieval provides in-domain reports from the training data and public medical corpora to serve as task-specific and ranking-support references. The LLM is instructed to create intermediate reports that are semantically close to high-ranking instances by the contrastive semantic ranking component. To refine intermediate reports, the coarse-to-fine decoding process uses a text generator. This generator takes the visual representation, a refinement prompt, and the intermediate report to produce the final output. When tested on the IU X-ray and MIMIC-CXR datasets, this method showed superior performance over baselines and reached SOTA results. For example, on the IU X-ray dataset, applying the full bootstrapping approach (I3 + C2FD) to a fine-tuned MiniGPT-4 improves the BLEU-4 score from 0.134 to 0.184, demonstrating a gain in linguistic quality.

6.3. Preference-Based Alignment Without Human Feedback (CheXalign)

To solve the problem of getting costly radiologist feedback, CheXalign [56] introduces an automated preference fine-tuning pipeline for chest X-ray report generation. The method uses large public datasets like MIMIC-CXR and CheXpert Plus. In these datasets, radiologist reports are paired with metrics like GREEN and BERTScore to create preference pairs. The authors introduced LC-GREEN, a version of the GREEN metric with explicit length control, to solve the problem of reward hacking caused by excessive verbosity. The results on the MIMIC-CXR and CheXpert Plus test set show that preference fine-tuning improved the performance of the baseline CheXagent model. The best configuration (Kahneman-Tversky Optimization [117] with GREEN Judge) raised the GREEN score from 0.249 to 0.328 (+31.9%), the LC-GREEN score from 0.218 to 0.293 (+34.1%), and the BERTScore from 0.856 to 0.867 (+1.27%). On the CheXpert Plus test set, this fine-tuning process raised the GREEN score from 0.248 to 0.341 (+37.2%), the LC-GREEN score from 0.202 to 0.266 (+31.4%), and the BERTScore from 0.851 to 0.863 (+1.42%). For the stronger baseline CheXagent-2, preference fine-tuning with Direct Preference Optimization [118] and GREEN Judge further improved performance on the MIMIC-CXR test set. The scores rose from GREEN = 0.326, LC-GREEN = 0.297, and BERTScore = 0.888 to 0.387 (+18.9%), 0.339 (+14.1%), and 0.891 (+0.30%), respectively. Similarly, on the CheXpert Plus test set, the CheXagent-2 baseline had scores of 0.349, 0.304, and 0.892. After DPO fine-tuning, these scores improved to 0.387 (+10.9%), 0.320 (+5.34%), and 0.888 (−0.38%). Finally, the clinical effectiveness was confirmed using CheXbert scores. On MIMIC-CXR, CheXalign improved CheXagent’s macro-F1 score from 38.9 to 44.0 and the micro-F1 score from 50.9 to 58.0.

7. Discussion and Open Challenges

Building on the previous analysis of datasets, metrics, and models, this section identifies key challenges and suggests a roadmap for future work in chest X-ray report generation. Our analysis is structured around six topics: data quality and supervision, factuality and generalization, methodological innovations, interpretability and clinical integration, the consequences and risks of LLM generation, and future perspectives.

7.1. Data Quality and Supervision

The dataset content composition and the quality of supervision signals can highly affect the performance of RRG models. The supervision quality in RRG is improved when techniques such as LLM-assisted preprocessing (XrayGPT [22]) and domain-specific pretraining (ChestBioX-Gen [60]) are applied. Also, handling the class imbalance led to an improvement of the absolute F1 score by 8% on rare pathologies (minority class) with the PromptMRG model [27], showing the importance of macro-averaged metrics. Nevertheless, the dominance of datasets with English language reports and the lack of lateral view radiographs mean that the models still have some limitations in generalization across various institutions and demographics.

7.2. Factuality and Generalization

For the clinical adoption of AI, the factual reliability of RRG models must be maximized. For instance, the accuracy of the generated reports may be limited if the training relies on visual features without clinical priors. In contrast, relational memory improves coherence across datasets, as illustrated by AERMNet [13]. Another recent method, demonstrated in CXR-IRGen [80], generates images and reports simultaneously with diffusion-based conditioning. However, the model is probably overfitting, since the AUROC scores on synthetic data are inflated. During an expert evaluation, LVLMs, including XrayGPT [22] and LLaVA [57], achieve approximately 72% factual accuracy with poor performance on the lateral views and uncommon pathologies, which represent the minority classes in the dataset. A recent study showed that RRG models capture pathology evolution and generate more clinically reliable reports with the incorporation of multi-view and temporal information [16]. The remaining challenges are achieving more robust generalization and ensuring factual consistency.

7.3. Beyond Architectures: Optimizing Factuality

The reliability and the clinical factuality of chest X-ray RRG are not necessarily improved with new designs and architectures. It can also be improved with techniques including alignment and optimization methods. Model hallucinations and factual errors can be reduced by including information from external datasets, using retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) frameworks, such as RULE [116]. Retrieving relevant instances and then using a coarse-to-fine decoding process is a bootstrapping technique that helps to adapt LLMs to the radiology field. Another preference-based optimization method, CheXalign [56], improves factual alignment. Even if its validation remains limited to a few datasets, this approach avoids costly radiologist feedback.

7.4. Interpretability and Clinical Integration