Abstract

Background/Objectives: Endometriosis is a chronic inflammatory condition that often requires laparoscopic examination for definitive diagnosis. Automated analysis of laparoscopic images using Deep Learning (DL) may support clinicians by improving diagnostic consistency and efficiency. This study aimed to develop and evaluate explainable DL models for the binary classification of endometriosis using laparoscopic images from the publicly available GLENDA (Gynecologic Laparoscopic ENdometriosis DAtaset). Methods: Four representative architectures—ResNet50, EfficientNet-B2, EdgeNeXt_Small, and Vision Transformer (ViT-Small/16)—were systematically compared under class-imbalanced conditions using five-fold cross-validation. To enhance interpretability, Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) were applied for visual explanation, and their quantitative alignment with expert-annotated lesion masks was assessed using Intersection over Union (IoU), Dice coefficient, and Recall. Results: Among the evaluated models, EdgeNeXt_Small achieved the best trade-off between classification performance and computational efficiency. Grad-CAM produced spatially coherent visualizations that corresponded well with clinically relevant lesion regions. Conclusions: The study shows that lightweight convolutional neural network (CNN)–Transformer architectures, combined with quantitative explainability assessment, can identify endometriosis in laparoscopic images with reasonable accuracy and interpretability. These findings indicate that explainable AI methods may help improve diagnostic consistency by offering transparent visual cues that align with clinically relevant regions. Further validation in broader clinical settings is warranted to confirm their practical utility.

Keywords:

endometriosis; laparoscopic imaging; deep learning; medical imaging; explainable AI; Grad-CAM; SHAP 1. Introduction

1.1. Overview of Endometriosis

Endometriosis is a chronic, estrogen-dependent inflammatory disorder characterized by the presence of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterine cavity, commonly affecting pelvic structures such as the ovaries and peritoneum [1,2]. It affects approximately 10% of women of reproductive age and is associated with symptoms including chronic pelvic pain, menstrual irregularities, and infertility. While non-invasive imaging techniques such as transvaginal ultrasound and MRI aid in detecting endometriomas and deep infiltrating lesions, laparoscopy remains the gold standard for definitive diagnosis due to its ability to enable direct visualization and histological confirmation [3,4].

A notable challenge in endometriosis is its clinical and visual heterogeneity. Lesions may appear as red, black, brown, or white spots, as well as clear or subtle plaques, reflecting different stages of vascularization, bleeding, and scarring. This variability complicates recognition during laparoscopy, even for experienced surgeons, and partly explains the average diagnostic delay of 7–10 years reported worldwide [5,6]. The delay is further compounded by the non-specific nature of symptoms and overlap with other conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome or interstitial cystitis. Beyond pelvic pain and infertility, endometriosis is increasingly recognized as a systemic condition with a profound impact on quality of life, psychological wellbeing, and socio-economic participation [7].

Management strategies remain focused on symptom control, as no curative therapy is currently available. Hormonal treatments—such as oral contraceptives, progestins, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists—are widely used to suppress ovarian function and reduce lesion activity, while surgical excision of implants is considered for more severe cases or when fertility is a priority [8,9]. However, even after surgery, recurrence is common, with up to 50% of patients experiencing symptom relapse within five years [8]. This highlights the chronic and relapsing nature of the disease and underscores the need for improved diagnostic and monitoring strategies. In this context, Machine Learning (ML) and explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) hold promise for supporting timely diagnosis, reducing inter-observer variability, and enhancing the interpretability of laparoscopic image analysis.

Despite these advances, challenges remain in timely diagnosis, individualized treatment planning, and disease monitoring. In this context, ML, and particularly XAI, holds promise for improving diagnostic accuracy, visual interpretability, and clinical decision support. By enhancing model transparency, XAI techniques can foster clinician trust and facilitate personalized care pathways for patients with endometriosis [10,11].

1.2. Research Gaps

Recent advances in Deep Learning (DL) have enabled automated image-based detection across multiple medical domains, including laparoscopic image analysis for endometriosis [12,13]. However, most existing studies share several limitations. First, the datasets used are generally small and imbalanced, restricting generalizability and leading to potential overfitting. Second, reproducibility is rarely addressed, with many works reporting results for a single train–test split rather than systematic cross-validation. Third, prior studies often focus on a single architecture, limiting comparisons across different models.

A further gap lies in the area of explainability. While DL methods have shown promise in classifying endometriosis, few studies have integrated post hoc interpretability techniques, and even fewer have quantitatively assessed how well explanation maps align with expert-annotated lesions. Without such validation, clinical trust in these models remains limited. Moreover, current explainability methods typically produce coarse heatmaps, which may highlight only parts of lesions or surrounding context, raising questions about their diagnostic relevance.

Taken together, these limitations hinder the clinical adoption of AI-based approaches for endometriosis. There is therefore a need for research that (i) systematically evaluates multiple architectures under robust validation settings; (ii) addresses class imbalance explicitly; and (iii) combines explainability techniques with quantitative metrics to assess their alignment with clinical annotations. This study aims to address these gaps by benchmarking diverse models on the GLENDA dataset and introducing a reproducible framework for both classification performance and explainability evaluation.

1.3. Aims and Contributions of the Study

This study aims to develop a robust and interpretable DL framework for the binary classification of endometriosis from laparoscopic images. Leveraging the publicly available GLENDA dataset, we systematically evaluate a diverse range of architectures while addressing the challenges of class imbalance and model transparency.

Our contributions are threefold. First, we benchmark four representative DL models, including a classical convolutional network (ResNet50), an efficient compound scaling network (EfficientNet-B2), a modern lightweight CNN–Transformer hybrid (EdgeNeXt_Small), and a pure Vision Transformer (ViT-Small/16), providing a comprehensive comparison across different paradigms. Second, we perform extensive experiments under different training setups, exploring image resolution, sampling strategies, loss functions, and the effect of pretrained weights. This systematic evaluation identifies EdgeNeXt_Small as achieving the strongest balance of performance and efficiency. Third, we integrate explainability methods to enhance clinical interpretability. Grad-CAM and SHAP are applied to interpret model predictions, and we quantitatively evaluate their alignment with expert-annotated lesion masks using Intersection over Union (IoU), Dice coefficient, and Recall.

By combining rigorous benchmarking with quantitative explainability evaluation, this work provides a reproducible framework for assessing both model accuracy and interpretability in endometriosis classification. Compared with prior studies (e.g., [12,13]) that focused on a single architecture or qualitative explanations, our approach demonstrates the value of lightweight CNN–Transformer models and establishes a foundation for clinically interpretable AI systems in laparoscopic imaging.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Machine Learning-Based Studies on Endometriosis

Endometriosis remains the clinical gold standard diagnosis by laparoscopy, yet interpretation is subject to observer variability. To improve diagnostic consistency and efficiency, several studies have applied ML and DL techniques to laparoscopic images.

Nifora et al. [12] developed a ResNet50-based classifier trained on the GLENDA dataset, reporting accuracy above 95%. While this demonstrated the potential of DL for endometriosis detection, the study was limited to a single architecture and did not address interpretability or class imbalance. Similarly, Visalaxi and Muthu [13] employed ResNet50 with OpenCV-based preprocessing and achieved 90% accuracy with an AUC of 0.78, but their work lacked a systematic evaluation of different models or data-splitting strategies.

A consistent challenge across these studies is the heterogeneity of lesions. Endometriosis can present with varied colors and textures, from “chocolate cysts” to subtle flame-like patches, complicating manual classification. While DL models show promise in capturing such variability [14], most published works are constrained by small datasets and limited evaluation strategies.

Some research has also explored lesion localization. For example, region-based CNNs (R-CNNs) and transformer-based models such as EndoViT [14] have been used to segment lesions and support intraoperative navigation. Although these approaches can highlight pathological regions, they typically require pixel-level annotations, which are scarce, and are rarely tested in real-time clinical workflows. Overall, current laparoscopic image-based studies are promising but remain limited by dataset size, reproducibility, and the absence of systematic explainability assessments.

Beyond laparoscopic imaging, ML has also been applied to other modalities in endometriosis research. Guerriero et al. [15] assessed seven classical ML models for detecting rectosigmoid deep endometriosis using transvaginal ultrasound features, with neural networks showing moderate predictive performance. In the genomics domain, Bendifallah et al. [16] integrated clinical and genomic data to develop a screening tool using classical ML techniques. Similarly, Akter et al. [17] and Zhang et al. [18] investigated transcriptomic data with ensemble models and Naïve Bayes classifiers, identifying potential biomarkers for diagnosis. These studies underscore the wider applicability of ML to endometriosis but remain distinct from the laparoscopic imaging focus of this work.

2.2. Application of Explainability Methods in Medical Imaging

Explainability methods are essential for interpreting the predictions of complex ML models, particularly in medical imaging, where clinician trust and decision support are critical. Prominent techniques include SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations), LIME (Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations), and Grad-CAM (Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping).

SHAP [19], grounded in cooperative game theory, assigns each input feature an importance score and has been widely adopted for both tabular and imaging data. LIME [20] provides local surrogate models by perturbing inputs and fitting simpler interpretable models. Grad-CAM [21], tailored for convolutional neural networks, produces heatmaps that highlight image regions most influential for prediction, making it well-suited to medical image analysis.

These methods have been increasingly applied in healthcare research. Bhandari et al. [22] used LIME and SHAP to interpret CNN predictions in renal abnormality detection, improving the transparency of models. Aldughayfiq et al. [23] applied similar methods to retinoblastoma diagnosis, showing how interpretability can aid in identifying critical biomarkers. Moujahid et al. [24] employed Grad-CAM on CNN models for COVID-19 detection from chest X-rays, demonstrating how heatmaps guided radiologists in validating AI outputs. Likewise, Dovletov et al. [25] incorporated Grad-CAM into a U-Net pipeline for synthesizing pseudo-CT images from MRI, improving radiotherapy planning.

Despite these advances, most applications remain retrospective and do not assess how well explanation maps align with expert-annotated clinical features. Furthermore, when applied to image-level labels, methods such as Grad-CAM often highlight only the most discriminative lesion areas rather than full pathological regions. This gap motivates our quantitative evaluation of explainability in endometriosis classification.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. GLENDA Dataset

The GLENDA (Gynecologic Laparoscopy ENdometriosis DAtaset) dataset [26] consists of 13,801 laparoscopic images collected from more than 120 surgical procedures performed on different patients. It includes both pathological and non-pathological cases to enable comprehensive analysis of endometriosis detection in real-world conditions.

Specifically, the dataset contains 373 annotated images depicting endometriotic lesions obtained from over 100 patients, along with 13,428 unannotated non-pathological images collected from approximately 20 control surgeries. Each annotated image includes expert-drawn region-based segmentation masks identifying one or more lesions. Four main pathological subcategories are defined in GLENDA—ovarian endometrioma, superficial peritoneal lesion, deep infiltrating endometriosis, and other pelvic abnormalities—representing the major visual and anatomical variations of the disease.

In this study, all pathological categories were merged into a single “pathological” class to enable binary classification between endometriosis-present and endometriosis-absent images. This decision reflects the clinical goal of distinguishing affected from unaffected cases rather than subtyping lesions. The class distribution is therefore highly imbalanced, with pathological images comprising roughly 2.7% of the total dataset (373 of 13,801 images). This imbalance reflects real clinical conditions, where normal laparoscopic frames are far more common than those depicting visible lesions.

GLENDA also provides considerable diversity in terms of surgical conditions and imaging environments. Images were captured using different laparoscopic systems and lighting settings, covering variations in anatomical region, instrument presence, and visual appearance (color, brightness, and tissue morphology). This diversity enhances the dataset’s representativeness and allows robust evaluation of model generalization.

All images in GLENDA are fully anonymized and made publicly available for research purposes. No personally identifiable or patient-specific metadata are included, and all use complies with the dataset’s open-access license.

3.2. Data Splitting

To obtain a reliable and unbiased evaluation of model performance, we replaced the fixed 60/20/20 proportional split originally used in prior studies with a five-fold stratified cross-validation strategy. This approach ensures that every image contributes to both training and testing in different folds while maintaining consistent class proportions across all subsets.

Given the pronounced class imbalance in the GLENDA dataset—where pathological images represent only about 2.7% of all samples—the abnormal class was divided into five equal partitions. In each fold, one subset of abnormal images was used as the test set, while an equal number of randomly selected normal images were sampled to form a balanced 1:1 test set. The remaining abnormal and normal images were allocated to the training and validation sets, with 20% of the training portion reserved for validation. To prevent data leakage and ensure robust evaluation, patient identifiers provided in the dataset were used to guarantee that images from the same patient never appeared across different folds. This approach maintained strict subject-level independence throughout the cross-validation process.

To further examine the effect of imbalance on learning, we experimented with different normal-to-abnormal ratios (1:1 and 2:1) within the training set. Additionally, an oversampling parameter k ∈ {0, 1} was introduced, where k = 0 indicates no duplication of abnormal samples and k = 1 duplicates all abnormal images once, effectively doubling their count. These complementary data-level strategies allowed us to assess the influence of both sampling ratio and minority-class augmentation on model stability.

All random splits were generated with a fixed random seed to ensure exact reproducibility of the experiments. This configuration balances fairness in evaluation with the need to mitigate the skewed class distribution inherent to GLENDA, enabling a robust comparison of architectures under consistent conditions.

3.3. Data Preprocessing

Effective preprocessing is essential for improving model performance and generalization, particularly when dealing with images that vary in color, brightness, and camera settings. Separate pipelines were designed for the training/validation and test sets to ensure that augmentation improved robustness without compromising evaluation integrity.

For the training and validation phases, the following transformations were applied sequentially:

- Resizing: All images were resized to a uniform input resolution using bicubic interpolation [27]. Standardizing spatial dimensions is necessary for compatibility across CNN- and Transformer-based architectures and to ensure that anatomical detail is preserved consistently.

- Random Horizontal Flip (p = 0.5): Introduced to simulate left–right anatomical variability and enhance spatial invariance.

- Random Rotation (±10°): Used to reduce sensitivity to minor angular deviations resulting from surgical camera motion.

- Color Jitter (brightness/contrast = 0.1): Applied to mimic lighting variations across different laparoscopic systems, improving the model’s robustness to illumination changes [28].

- Normalization: After conversion to tensors, image intensities were normalized channel-wise to the range [−1, 1] using a mean and standard deviation of 0.5. This step accelerates convergence and stabilizes gradient updates during training.

For the test set, only resizing and normalization were applied. No augmentation was introduced at this stage to preserve the natural statistical distribution of unseen data and ensure that reported metrics reflect genuine generalization rather than robustness to synthetic transformations.

Additional augmentation methods—such as Gaussian blur, grayscale conversion, random erasing, and noise injection—were evaluated experimentally but did not yield consistent performance gains; therefore, they were excluded from the final pipeline.

This preprocessing strategy was selected to balance realism and variability: it mitigates overfitting to specific imaging conditions while maintaining fidelity to the visual characteristics of laparoscopic scenes used in the GLENDA dataset.

3.4. Model Architectures

To obtain a representative yet computationally efficient comparison across modern vision architectures, we selected four pretrained models that encompass the main design paradigms in medical image analysis: a classical convolutional neural network (CNN), an efficient compound-scaling CNN, a lightweight CNN–Transformer hybrid, and a pure Vision Transformer (ViT). These models are all supported in the timm library [29], come with publicly available ImageNet pretrained weights, and are fully compatible with the explainability pipeline employed in this study (Grad-CAM, SHAP, and LIME). The key characteristics of each model are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of models in terms of accuracy, parameter size, and preprocessing settings.

ResNet50 [30] is a widely adopted deep residual CNN (≈25 M parameters) that mitigates vanishing-gradient problems through identity skip connections. It serves as a high-capacity baseline and provides continuity with previous endometriosis classification work on the GLENDA dataset [26].

EfficientNet-B2 [31] employs compound scaling of network depth, width, and input resolution to achieve strong accuracy with relatively few parameters (≈9 M). Its efficiency profile makes it particularly suitable for biomedical imaging tasks in which overfitting is a concern and computational resources are limited.

EdgeNeXt_Small [32] represents a recent hybrid CNN–Transformer architecture that integrates split depth-wise transpose attention (SDTA) blocks with lightweight convolutional layers. With only ≈5.6 M parameters, it combines local and global feature extraction, enabling fine-grained contextual modelling in heterogeneous laparoscopic scenes while maintaining low computational cost.

ViT-Small/16 [33] is a compact pure Vision Transformer (≈22 M parameters) that tokenizes an image into 16 × 16 patches and captures long-range dependencies through self-attention. It was included to benchmark a transformer-only paradigm against convolutional and hybrid designs. Because its learned positional embeddings are tied to a 224 × 224 input grid, it was evaluated at that native resolution.

To preserve spatial detail in laparoscopic imagery, all CNN-based and hybrid models (ResNet50, EfficientNet-B2, EdgeNeXt_Small) were trained and tested using resized inputs of 320 × 320 pixels. The ViT-Small/16 model was fixed at 224 × 224 due to its positional encoding constraint. All images were rescaled using bicubic interpolation with centre preservation to maintain consistency across architectures.

Overall, this set of models balances architectural diversity, parameter range (≈5 M to 25 M), availability of high-quality pretrained weights, and relevance to prior medical imaging research. It provides a robust foundation for systematic benchmarking of performance and explainability in endometriosis classification.

3.5. Model Training and Optimization

All models were trained in a Transfer-Learning setting, initialized with publicly available ImageNet-pretrained weights [34]. Leveraging these pretrained representations accelerates convergence and improves downstream performance, particularly when working with limited biomedical datasets [35]. For each architecture, the entire network was fine-tuned without freezing layers to allow complete adaptation to the laparoscopic imaging domain.

Training was conducted for a maximum of 50 epochs using a mini-batch size of 32, selected to balance gradient stability and GPU memory constraints on an NVIDIA RTX 4090. To reduce overfitting associated with small and imbalanced data, early stopping was employed: training automatically terminated if validation loss failed to improve for seven consecutive epochs (patience = 7), and the weights corresponding to the best validation performance were restored for testing.

To ensure stable convergence, a small grid search was performed for each model to determine the most suitable learning rate. The explored values were (1) and for ResNet50, (2) and for EfficientNet-B2, (3) and for EdgeNeXt_Small, and (4) and for ViT-Small/16. The optimal learning rate for each configuration was selected based on the best validation performance achieved within the five-fold cross-validation procedure.

The best learning rate for each model and configuration was selected based on validation performance within the five-fold cross-validation framework. Optimization was performed using the Adam optimizer [36] with default β parameters due to its robustness under heterogeneous batch statistics. A cosine annealing learning rate scheduler (CosineAnnealingLR) [37] was applied across epochs to allow larger exploratory updates during early training and finer adjustments toward convergence, which helps prevent overfitting when the data size is limited.

Because the GLENDA dataset is strongly imbalanced (non-pathological ≫ pathological), we evaluated three loss functions to improve minority-class learning:

- Standard Cross-Entropy (CE): The baseline loss for classification tasks [38].

- Weighted Cross-Entropy: Incorporating inverse frequency class weights per fold to upweight the minority (pathological) class [39].

- Focal Loss (γ = 2): Downweights easy majority examples and focuses training on hard or misclassified samples [39].

These loss formulations were combined with data-level strategies such as different normal-to-abnormal ratios (1:1 and 2:1) and oversampling factors (k ∈ {0,1}) to comprehensively assess how both sampling and algorithmic techniques affect model robustness.

By integrating transfer learning, grid-searched optimization, adaptive learning rate scheduling, and imbalance-aware losses, this training protocol provides a fair and reproducible framework for comparing diverse architectures on the GLENDA dataset. Alternative methods such as SMOTE [40] or focal-Tversky loss [41] were not applied, as SMOTE may not be well suited to image-space interpolation [42] and focal-Tversky is primarily intended for segmentation rather than image-level classification.

3.6. Model Explainability

To enhance model transparency and clinical interpretability, several post hoc explainability methods were evaluated on the trained models. The initial comparison included SHAP [19], LIME [20], and Grad-CAM [21], which together represent three mainstream families of interpretability techniques applicable to medical imaging.

Preliminary experiments showed that LIME produced unstable and spatially inconsistent heatmaps across repeated runs. This instability was confirmed quantitatively rather than subjectively, leading to its exclusion from further analysis. SHAP was retained for comparison because it provides pixel-wise attributions that are model-agnostic and can offer complementary interpretive insights. However, its computational cost and tendency to produce diffused activation patterns limited its spatial precision for high-resolution images.

Grad-CAM was therefore selected as the primary explainability method for detailed evaluation. It computes class-specific activation maps by back-propagating gradients through the final convolutional layer, thereby identifying the image regions most influential in a model’s decision. Grad-CAM has been widely adopted in medical imaging due to its ability to produce coherent and visually interpretable heatmaps.

To quantitatively assess how well the Grad-CAM explanations aligned with expert-annotated pathological areas, three metrics were used: (1) Intersection over Union (IoU), (2) Dice coefficient, and (3) Recall. IoU and Dice are standard segmentation metrics that jointly penalize false positives and false negatives, thereby capturing both over- and under-segmentation. In contrast, Recall measures the proportion of the annotated lesion area captured by the Grad-CAM heatmap, providing a complementary view of attention coverage. Because Grad-CAM maps are not direct segmentation outputs and often highlight only the most discriminative features, evaluating multiple metrics ensures a balanced assessment of spatial correspondence.

A binarization threshold of 0.3 was determined empirically as the optimal trade-off between activation coverage and stability of IoU and Dice scores. At this threshold, the Grad-CAM activation covered approximately 30.3% of the lesion area on average. Visual overlays combining Grad-CAM heatmaps with expert annotations were also generated for all positive cases to provide qualitative insights into whether the model’s focus corresponded to clinically meaningful regions.

Representative Grad-CAM results were also informally reviewed by a consultant gynecologist from North Bristol NHS Trust, who indicated that such visual explanations could serve as a helpful assistive tool in specific diagnostic situations. Overall, the proposed explainability protocol provides a preliminary framework for both qualitative and quantitative evaluation of model interpretability, aiming to complement classification performance with greater transparency, an important step toward potential clinical applicability of AI-assisted laparoscopic imaging.

4. Results

We conducted extensive experiments using four DL architectures under multiple configurations of loss functions, sampling strategies, and training parameters. The best performance was obtained with EdgeNeXt_Small, trained using a class-weighted cross-entropy loss, an input resolution of 320 × 320, and a 2:1 normal-to-abnormal sampling ratio without oversampling. This setup achieved an average test accuracy of 97.86% and an AUC of 99.62% across five-fold cross-validation, demonstrating a strong balance between precision and recall.

Table 2 summarizes the best performance achieved by each architecture, while Table 3 reports the average results across all hyperparameter combinations. Overall, EdgeNeXt_Small consistently outperformed the other models, followed by EfficientNet-B2, with ResNet50 and ViT-Small/16 showing comparatively lower and less stable performance.

Table 2.

Best performance (%) of each model (5-fold average across all configurations).

Table 3.

Average performance (%) of models across hyperparameter configurations (5-fold mean).

4.1. Comparison of Model Performance

Table 2 presents the best performance achieved by each model across all hyperparameter configurations. EdgeNeXt_Small achieved the highest F1-score (97.86%) and accuracy (97.86%), demonstrating a strong balance between precision and recall. Although EfficientNet-B2 produced a slightly higher AUC (99.73%), its F1-score was marginally lower, indicating minor trade-offs in overall classification consistency. ResNet50 achieved the highest precision (99.19%) but lower recall (94.63%), reflecting a tendency to favor the majority class. In contrast, ViT-Small/16, trained at a lower resolution (224 × 224), showed the weakest overall performance among the evaluated models.

Table 3 reports the mean results averaged across all hyperparameter settings. Both EdgeNeXt_Small and EfficientNet-B2 consistently achieved high scores across accuracy, F1, and AUC, confirming their robustness. The comparatively lower performance of ViT-Small/16 suggests that transformer-only architectures may be less effective for small and imbalanced medical datasets without additional domain adaptation.

Overall, these results highlight the advantage of lightweight hybrid architectures. EdgeNeXt_Small, in particular, combines high accuracy and strong generalization with minimal computational cost, making it a promising candidate for clinical deployment where efficiency and interpretability are equally important. Although EdgeNeXt_Small slightly outperformed EfficientNet-B2, the difference was consistent but not statistically tested due to the small number of folds (n = 5). Model performance was evaluated using standard metrics—accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and AUC—defined as follows:

where TP, TN, FP, and FN denote true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively. The AUC represents the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, summarizing model performance across all decision thresholds.

4.2. Effect of Loss Function

Table 4 summarizes the model performance under three different loss functions: standard cross-entropy (CE), class-weighted cross-entropy, and focal loss. The results show that class-weighted CE achieved the best overall balance, yielding the highest F1-score (94.60%) while maintaining stable accuracy and precision across models. Standard CE performed comparably but demonstrated slightly reduced recall, indicating a mild bias toward the majority class. In contrast, focal loss increased recall (93.60%) by focusing on harder-to-classify samples, but this came at the expense of precision and accuracy.

Table 4.

Comparison of model performance (%) under different loss functions. CE denotes standard Cross-Entropy Loss, Weighted applies class-weighted cross-entropy, and Focal denotes Focal Loss. Results are 5-fold averages over all combinations.

The relatively small performance differences across all three losses suggest that the models were generally robust to the choice of loss function. However, the consistent advantage of the weighted CE formulation highlights the importance of incorporating class priors when learning from highly imbalanced datasets such as GLENDA. Consequently, the weighted CE loss was selected as the optimal configuration for subsequent analyses.

4.3. Effect of Oversampling Abnormal Images

Table 5 presents the results of experiments evaluating whether duplicating abnormal images in the training set (oversampling) improves classification performance. Oversampling the minority class (k = 1) produced a modest increase in F1-score (from 94.23% to 94.52%) and AUC (from 98.58% to 98.79%). Although these gains were small, they indicate that duplicating pathological samples can slightly enhance model sensitivity to rare cases without negatively affecting overall accuracy or precision.

Table 5.

Effect of oversampling abnormal images during training. A value of 1 duplicates all abnormal samples once, and 0 indicates no oversampling. Results are 5-fold averages across all settings, with metrics reported as percentages (%).

The limited improvement suggests that class imbalance in the dataset can be largely mitigated through architectural robustness and loss weighting alone, reducing the necessity for aggressive oversampling. In practice, minimal oversampling (k = 1) was sufficient to stabilize learning without introducing redundancy or overfitting to the minority class.

4.4. Effect of Normal-to-Abnormal Sampling Ratio

Table 6 reports the effect of varying the ratio of normal to abnormal images in the training set. Increasing the sampling ratio from 1:1 to 2:1 consistently improved performance across all metrics, with the F1-score rising from 94.11% to 94.64% and the AUC from 98.47% to 98.90%. This improvement suggests that moderate inclusion of additional normal images enhances model generalization by exposing the network to greater variability in healthy tissue appearance.

Table 6.

Effect of normal-to-abnormal sampling ratio on model performance. A 1:1 ratio balances classes, while a 2:1 ratio includes twice as many normal images. Metrics are reported as percentages.

Excessive under-sampling of the normal class can lead to a reduced diversity of negative examples, potentially limiting the model’s ability to distinguish subtle pathological patterns. By contrast, a 2:1 ratio preserves image diversity while maintaining class balance at a manageable level. Therefore, this ratio was adopted in the final configuration, offering the best trade-off between sensitivity and generalization.

4.5. Explainability Analysis

Explainability evaluation was applied to examine how well model attention aligned with expert-annotated lesions. Among the tested methods, Grad-CAM provided the most spatially coherent and clinically interpretable results. Quantitative assessment was based on three metrics: IoU, Dice coefficient, and Recall.

The best-performing configuration (EdgeNeXt_Small with class-weighted cross-entropy) achieved an average IoU of 35.3%, Dice of 44.5%, and Recall of 57.2%. These values indicate that Grad-CAM heatmaps captured more than half of the annotated lesion areas while maintaining moderate spatial precision. Although explainability metrics are inherently lower than segmentation scores due to their coarse attention maps, the observed coverage demonstrates that the model focuses on clinically meaningful regions rather than irrelevant background structures or surgical instruments.

From a clinical perspective, these metrics offer valuable insight into model reliability and diagnostic utility. A high recall suggests that the model’s attention extends across most of the true lesion region, reducing the risk of missed pathology, which is critical for safe clinical deployment [43]. In contrast, IoU and Dice reflect how precisely the model’s highlighted areas overlap with true lesion boundaries—an important consideration for intraoperative decision support and surgical localization accuracy. The moderate Dice score observed here captures the balance between broad lesion coverage and spatial specificity typical of explainability methods in medical image analysis [44].

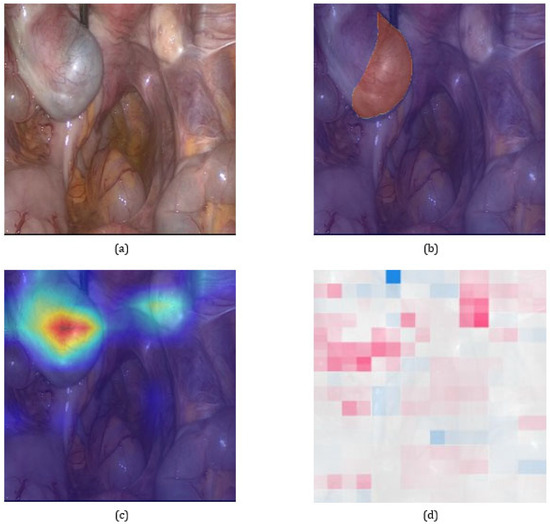

Figure 1 shows representative Grad-CAM overlays on laparoscopic images. The highlighted areas generally corresponded well with annotated lesions of different colors and textures, including superficial red and brown lesions and fibrotic white plaques. This visual consistency confirms that the model learned clinically relevant features across the heterogeneous presentation of endometriosis.

Figure 1.

Visual comparison of explainability results on a representative pathological image. (a) Original laparoscopic image. (b) Image overlaid with the expert-annotated lesion mask. (c) Grad-CAM heatmap illustrating the model’s attention to potential lesion areas. (d) SHAP explanation providing pixel-level attribution. Grad-CAM serves as the primary method in our analysis due to its stable and spatially coherent focus, as further supported by quantitative alignment with expert annotations.

Overall, these findings indicate that Grad-CAM provides not only transparency but also clinically meaningful interpretability, allowing verification that model decisions are grounded in anatomically and diagnostically relevant regions. Such alignment between model attention and lesion localization represents a crucial step toward trustworthy AI-assisted diagnosis in laparoscopic imaging.

5. Discussion

5.1. Model Performance and Comparison

Table 2 and Table 3 summarize the classification performance of the four evaluated models on the test set. Results are reported as the mean of five-fold cross-validation for both the best-performing configuration of each model and the average across all hyperparameter combinations.

Among all candidates, EdgeNeXt_Small demonstrated the best overall performance, achieving an accuracy and F1-score of 97.86% and an AUC of 99.62%. Its strong balance between precision and recall, combined with a compact architecture (5.6 M parameters), makes it well suited for small-scale medical imaging tasks where computational resources are limited. Notably, it also achieved the highest average F1-score (96.43%) across all configurations, indicating stable and robust behavior regardless of hyperparameter variation.

EfficientNet-B2 followed closely, achieving a slightly higher AUC (99.73%) in its best configuration and competitive performance overall. Its compound scaling strategy likely contributed to improved generalization, making it a strong secondary candidate. ResNet50, while achieving the highest precision (99.19%), exhibited lower recall (94.63%) and a considerably larger parameter count (~25 M), which may increase the risk of overfitting and explain its performance drop under average-case conditions.

ViT-Small/16 consistently underperformed relative to CNN-based models, with accuracy and F1-score remaining lowest in both best-case (95.30%) and average-case (90.22%) scenarios. This gap likely arises from two factors: (1) its lower input resolution (224 × 224) compared with the 320 × 320 used in other models, which reduces spatial detail; and (2) the transformer’s dependence on large-scale data, making it less effective for small and imbalanced medical datasets without extensive domain-specific pretraining. Higher input resolutions were not tested, as ViT-Small/16 relies on fixed positional embeddings tied to a 224 × 224 grid, and modifying this would require retraining from scratch, compromising comparability with pretrained weights.

Across all CNN-based architectures, precision generally exceeded recall, suggesting a mild bias toward the majority (normal) class. This behavior likely reflects the underlying data distribution, where normal images are more visually consistent and thus easier to model than abnormal cases. In contrast, ViT-Small/16 was the only model with recall exceeding precision, possibly due to its attention mechanism being more responsive to rare or sparse lesion features, though at the cost of overall stability and accuracy. In summary, EdgeNeXt_Small offers the best trade-off between performance and efficiency and was therefore selected as the backbone for subsequent ablation studies and further explainability analysis.

Collectively, these observations suggest that integrating a lightweight CNN–Transformer architecture with a quantitative evaluation of explainability may provide a useful direction for improving both performance and interpretability in endometriosis classification. Previous studies analyzing laparoscopic images have primarily used convolutional neural networks with qualitative visual explanations to illustrate model attention (e.g., [45,46]). The present study may be considered as a step further by combining a hybrid architecture with quantitative Grad-CAM assessment, offering preliminary insights into how explainability metrics might complement accuracy measures in evaluating AI systems for laparoscopic imaging.

5.2. Effectiveness of Imbalance Mitigation Strategies

To address the class imbalance inherent in the GLENDA dataset, three mitigation strategies were systematically evaluated: (1) customized loss functions, (2) oversampling of abnormal images, and (3) adjustment of the initial sampling ratio between normal and abnormal classes.

As presented in Table 4, the class-weighted cross-entropy yielded the best overall balance across evaluation metrics, achieving an F1-score of 94.60%, marginally higher than standard cross-entropy (94.48%) and focal loss (94.04%). While focal loss increased recall (93.60%), it led to a reduction in precision and accuracy, likely due to its aggressive weighting toward hard examples. In contrast, class weighting improved stability and provided a more even trade-off between sensitivity and specificity, making it the most effective loss formulation for the GLENDA dataset.

Duplicating the minority-class images once (oversampling factor = 1) produced a modest improvement in F1-score—from 94.23% to 94.52%, as well as slight gains in accuracy and AUC (Table 5). These results indicate that limited duplication of pathological samples can enhance model sensitivity to rare lesion appearances without compromising specificity or inducing overfitting.

Adjusting the normal-to-abnormal image ratio from 1:1 to 2:1 resulted in the highest overall F1-score (94.64%), mainly due to an increase in precision (Table 6). This finding suggests that allowing a mild imbalance in favor of the normal class improves generalization by exposing the model to a broader representation of healthy tissue patterns.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that all three approaches contributed to mitigating the effects of class imbalance to varying degrees. However, the best performance was achieved through a combined strategy integrating class-weighted loss, moderate oversampling, and a 2:1 sampling ratio, which formed the basis of the final optimal configuration used in subsequent experiments.

5.3. Explainability and Interpretability

To enhance model transparency and foster clinical trust, two widely used explainability techniques—Grad-CAM and SHAP—were applied to interpret the model’s decision-making process. As illustrated in Figure 1, Grad-CAM generated spatially coherent heatmaps that aligned closely with the annotated lesion regions, highlighting the areas most influential in the model’s classification. SHAP similarly identified diagnostically relevant regions but produced lower-resolution and more diffuse attribution patterns, consistent with its model-agnostic nature.

These differences arise from the distinct computational principles of each method. Grad-CAM, designed for convolutional architectures, computes class-specific activation maps by backpropagating gradients through the final convolutional layers, thereby capturing focused spatial attention. SHAP, in contrast, estimates local feature contributions using perturbation-based sampling and aggregation, which can lead to broader or less spatially precise patterns when applied to high-dimensional image data. Although IoU and Dice scores were moderate, this behavior was expected for attention-based explanations, and the resulting coarse localization remained clinically informative by confirming that the model presented plausible lesion regions rather than unrelated background areas.

An important observation is that both methods often highlighted regions extending beyond the precise lesion boundaries or displaying blurred contours. This behavior is expected, as the models were trained with image-level binary labels rather than pixel-wise annotations. Consequently, the resulting explanations capture learned contextual associations that may include surrounding tissues or peripheral visual cues relevant to classification decisions. From a clinical perspective, such contextual attention can be valuable, as it reflects patterns that surgeons often consider when identifying subtle or complex lesions [44,47].

These findings underscore both the potential and the limitations of current explainability tools in medical imaging. While Grad-CAM and SHAP provide meaningful qualitative insights into model attention, their outputs should not be interpreted as precise diagnostic localization. Instead, they serve as supportive visual evidence for understanding model reasoning and for validating whether AI attention corresponds to clinically relevant areas. Future research could explore weakly supervised or multi-task learning approaches to better align model attention with true lesion boundaries, thereby improving both interpretability and diagnostic confidence.

6. Future Work

Building on the findings of this study, future work should focus on a few key areas that can strengthen the performance, interpretability, and clinical applicability of AI models for endometriosis classification.

- Dataset expansion and diversity: The GLENDA dataset provides a valuable foundation but remains limited in scale and class balance. Expanding data collection to include a larger and more heterogeneous cohort from multiple centers, covering varied anatomical regions, imaging settings, and disease severities, would help improve model robustness and generalization [48]. Future datasets should also aim to reduce potential sources of bias arising from differences in laparoscopic equipment and the absence of demographic metadata, thereby enhancing fairness and representativeness in model evaluation.

- Incorporating spatial supervision: The current models were trained with image-level labels only. Introducing weakly or semi-supervised learning techniques, such as pseudo-mask generation or region-based attention constraints, could guide the model to focus more precisely on lesion-relevant areas while maintaining classification performance [49].

- Refining explainability evaluation: While this study quantitatively assessed Grad-CAM outputs using IoU, Dice, and Recall, these metrics remain limited proxies for clinical interpretability. Future work should involve systematic evaluation with domain experts to determine whether highlighted regions correspond to diagnostically meaningful cues and to develop more clinically grounded explainability metrics [44].

- External validation and clinical integration. The current framework has not yet been validated on independent datasets. Cross-institutional testing and real-world deployment studies are essential to ensure reliability under diverse imaging conditions and to evaluate how such models could integrate into surgical decision-support systems. In practice, explainable AI tools should complement, rather than replace, clinician judgment in the diagnostic process.

7. Conclusions

This study investigated the use of deep learning for the classification of endometriosis from laparoscopic images using the GLENDA dataset. Among the four evaluated architectures, the lightweight CNN–Transformer hybrid EdgeNeXt_Small achieved the most balanced performance under class-imbalanced conditions, combining strong accuracy with computational efficiency. The systematic comparison and cross-validation setup ensured fair evaluation across models and improved the robustness of the reported results.

Beyond classification, the study applied a quantitative evaluation of post hoc explainability using Intersection over Union (IoU), Dice, and Recall metrics to assess Grad-CAM activation maps against the reference lesion masks provided in the GLENDA dataset. In this setting, Grad-CAM produced spatially coherent and clinically interpretable visualizations, whereas SHAP generated more diffuse and less localized attributions, consistent with its broader feature-based explanation approach.

Overall, these findings suggest that combining compact hybrid architectures with metric-based explainability assessment can enhance transparency and reliability in AI-assisted laparoscopic imaging. While broader validation on external datasets remains necessary, this work offers a step toward developing interpretable and resource-efficient tools to support endometriosis diagnosis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z. and M.E.; methodology, Y.Z.; software, Y.Z.; validation, Y.Z. and M.E.; formal analysis, Y.Z.; investigation, Y.Z.; resources, M.E.; data curation, Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, M.E.; visualization, Y.Z.; supervision, M.E.; project administration, M.E.; funding acquisition, M.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the UWE Summer Research Internship Programme.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve human participants or animals. All experiments were conducted on a publicly available anonymized dataset (GLENDA).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve human participants or the collection of new patient data.

Data Availability Statement

The GLENDA dataset (Gynecologic Laparoscopy Endometriosis Dataset) used in this study is publicly available at https://ftp.itec.aau.at/datasets/GLENDA/ (accessed on 1 June 2025). No new data were created or analyzed in this study. The code is publicly available at https://github.com/Mahmoud-Elbattah/glenda-xai (accessed on 4 November 2025).

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-4, June 2025 version) for assistance in language refinement. The authors have reviewed and edited the AI-assisted content and take full responsibility for the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| ViT | Vision Transformer |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| LIME | Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations |

| Grad-CAM | Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping |

| GLENDA | Gynecologic Laparoscopy Endometriosis Dataset |

| SDTA | Split Depth-wise Transpose Attention |

References

- World Health Organization. Endometriosis. WHO Fact Sheets. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/endometriosis (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Zondervan, K.T.; Becker, C.M.; Missmer, S.A. Endometriosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1244–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giudice, L.C. Clinical Practice. Endometriosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 2389–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, N.P.; Hummelshoj, L.; World Endometriosis Society Montpellier Consortium; Abrao, M.S.; Adamson, G.D.; Allaire, C.; Amelung, V.; Andersson, E.; Becker, C.; Birna Árdal, K.B.; et al. World Endometriosis Society Montpellier Consortium. Consensus on Current Management of Endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2013, 28, 1552–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapron, C.; Marcellin, L.; Borghese, B.; Santulli, P. Rethinking Mechanisms, Diagnosis and Management of Endometriosis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 666–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.K.; Chapron, C.; Giudice, L.C.; Laufer, M.R.; Leyland, N.; Missmer, S.A.; Singh, S.S.; Taylor, H.S. Clinical Diagnosis of Endometriosis: A Call to Action. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 220, 354.e1–354.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missmer, S.A.; Tu, F.F.; Sanjay, K.A.; Chapron, C.; Soliman, A.M.; Chiuve, S.; Eichner, S.; Flores-Caldera, I.; Horne, A.W.; Kimball, A.B.; et al. Impact of endometriosis on life-course potential: A narrative review. Reprod. Sci. 2021, 14, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veth, V.B.; Keukens, A.; Reijs, A.; Bongers, M.Y.; Mijatovic, V.; Coppus, S.F.; Maas, J.W. Recurrence after surgery for endometrioma: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Fertil. Steril. 2024, 122, 1079–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunselman, G.A.J.; Vermeulen, N.; Becker, C.; Calhaz-Jorge, C.; D’Hooghe, T.; De Bie, B.; Heikinheimo, O.; Horne, A.W.; Kiesel, L.; Nap, A.; et al. ESHRE Guideline: Management of Women with Endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2014, 29, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Gomez, C.; Huang, C.-M.; Unberath, M. Explainable medical imaging AI needs human-centered design: Guidelines and evidence from a systematic review. npj Digit. Med. 2022, 5, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salahuddin, Z.; Woodruff, H.C.; Chatterjee, A.; Lambin, P. Transparency of deep neural networks for medical image analysis: A review of interpretability methods. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 140, 105111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nifora, C.; Chasapi, L.; Chasapi, M.K.; Koutsojannis, C. Deep Learning Improves Accuracy of Laparoscopic Imaging Classification for Endometriosis Diagnosis. J. Clin. Med. Surg. 2023, 4, 1137–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visalaxi, S.; Muthu, T.S. Automated Prediction of Endometriosis Using Deep Learning. Int. J. Nonlinear Anal. Appl. 2021, 12, 2403–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batić, D.; Holm, F.; Özsoy, E.; Czempiel, T.; Navab, N. EndoViT: Pretraining vision transformers on a large collection of endoscopic images. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2024, 19, 1085–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerriero, S.; Pascual, M.; Ajossa, S.; Neri, M.; Musa, E.; Graupera, B.; Rodriguez, I.; Alcazar, J.L. Artificial intelligence (AI) in the detection of rectosigmoid deep endometriosis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2021, 261, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendifallah, S.; Puchar, A.; Suisse, S.; Delbos, L.; Poilblanc, M.; Descamps, P.; Golfier, F.; Touboul, C.; Dabi, Y.; Daraï, E. Machine learning algorithms as new screening approach for patients with endometriosis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Xu, D.; Nagel, S.C.; Bromfield, J.J.; Pelch, K.E.; Wilshire, G.B.; Joshi, T. GenomeForest: An ensemble machine learning classifier for endometriosis. AMIA Jt. Summits Transl. Sci. Proc. 2020, 2020, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, H.; Yang, H.; Shuid, A.N.; Sandai, D.; Chen, X. Machine learning-based integrated identification of predictive combined diagnostic biomarkers for endometriosis. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1290036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 4765–4774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. “Why Should I Trust You?”: Explaining the Predictions of Any Classifier. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD’16), San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-CAM: Visual Explanations from Deep Networks via Gradient-Based Localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV 2017), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; IEEE: Venice, Italy, 2017; pp. 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, M.; Yogarajah, P.; Kavitha, M.S.; Condell, J. Exploring the capabilities of a lightweight CNN model in accurately identifying renal abnormalities: Cysts, stones, and tumors, using LIME and SHAP. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldughayfiq, B.; Ashfaq, F.; Jhanjhi, N.Z.; Humayun, M. Explainable AI for retinoblastoma diagnosis: Interpreting deep learning models with LIME and SHAP. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moujahid, H.; Cherradi, B.; Al-Sarem, M.; Bahatti, L.; Eljialy, A.B.A.M.Y.; Alsaeedi, A.; Saeed, F. Combining CNN and Grad-CAM for COVID-19 disease prediction and visual explanation. Intell. Autom. Soft Comput. 2021, 32, 1235–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovletov, G.; Pham, D.D.; Lörcks, S.; Pauli, J.; Gratz, M.; Quick, H.H. Grad-CAM guided U-Net for MRI-based pseudo-CT synthesis. In Proceedings of the 44th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Glasgow, UK, 11–15 July 2022; pp. 2071–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibetseder, A.; Kletz, S.; Schoeffmann, K.; Keckstein, S.; Keckstein, J. GLENDA: Gynecologic Laparoscopy Endometriosis Dataset. In MultiMedia Modeling: 26th International Conference, MMM 2020, Daejeon, South Korea, 5–8 January 2020; Proceedings, Part II; Ro, Y.M., Cheng, W.-H., Kim, J., Chu, W.-T., Cui, P., Choi, J.-W., Hu, M.-C., De Neve, W., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 11962, pp. 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, R.C.; Woods, R.E. Digital Image Processing; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Shorten, C.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. A survey on image data augmentation for deep learning. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wightman, R. PyTorch Image Models (timm). 2019. Available online: https://github.com/huggingface/pytorch-image-models (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q.V. EfficientNet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; pp. 6105–6114. [Google Scholar]

- Maaz, M.; Khan, S.; Khan, F.S.; Van Gool, L. EdgeNeXt: Efficiently amalgamated CNN-transformer architecture for mobile vision applications. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16 × 16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L.J.; Li, K.; Fei-Fei, L. ImageNet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Miami, FL, USA, 20–25 June 2009; pp. 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosinski, J.; Clune, J.; Bengio, Y.; Lipson, H. How transferable are features in deep neural networks? Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. (NeurIPS) 2014, 2, 3320–3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), San Diego, CA, USA, 7–9 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. SGDR: Stochastic Gradient Descent with Warm Restarts. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Toulon, France, 24–26 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: Synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2002, 16, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, N.; Khan, N.M. A novel focal tversky loss function with improved attention u-net for lesion segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 16th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI 2019), Venice, Italy, 8–11 April 2019; IEEE: Venice, Italy, 2019; pp. 683–687. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Liu, W.; Wu, J.; Cao, L.; Meng, Q.; Kennedy, P.J. Training deep neural networks on imbalanced data sets. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–29 July 2016; IEEE: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2016; pp. 4368–4374. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.H.; Han, K.; Jang, H.Y.; Park, J.E.; Lee, J.-G.; Kim, D.W.; Choi, J. Methods for clinical evaluation of artificial intelligence algorithms for medical diagnosis. Radiology 2023, 306, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzinger, A.; Langs, G.; Denk, H.; Zatloukal, K.; Müller, H. Causability and Explainability of Artificial Intelligence in Medicine. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2019, 9, e1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leibetseder, A.; Schoeffmann, K.; Keckstein, J.; Keckstein, S. Endometriosis detection and localization in laparoscopic gynecology. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 6191–6215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netter, A.; Noorzadeh, S.; Duchateau, F.; Abrao, H.; Canis, M.; Bartoli, A.; Bourdel, N.; Desternes, J.; Peyras, J.; Pouly, J.L.; et al. Initial results in the automatic visual recognition of endometriosis lesions by artificial intelligence during laparoscopy: A proof-of-concept study. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montavon, G.; Samek, W.; Müller, K.-R. Methods for Interpreting and Understanding Deep Neural Networks. Digit. Signal Process. 2018, 73, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litjens, G.; Kooi, T.; Bejnordi, B.E.; Setio, A.A.A.; Ciompi, F.; Ghafoorian, M.; van der Laak, J.A.W.M.; van Ginneken, B.; Sánchez, C.I. A Survey on Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis. Med. Image Anal. 2017, 42, 60–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Khosla, A.; Lapedriza, A.; Oliva, A.; Torralba, A. Learning Deep Features for Discriminative Localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2921–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).