Abstract

People with Down Syndrome often experience more barriers to achieving a good quality of life compared to people without disabilities. A lot of the existing research has focused on the views of parents and professionals, rather than directly including the voices and perspectives of people with Down Syndrome themselves. We wanted to find out how this might be done. At the 2024 World Down Syndrome Conference, over 140 adults with Down Syndrome came together at a one-day Forum to talk about their lives—aspects that are going well and what could be better. The goal was to hear directly from them. This article explains how the Forum was run so that others with Down Syndrome can use a similar process. We describe how Artificial Intelligence (AI) was used to assist the authors in organising and sharing the information from participants, such as grouping what people said into different themes and helping to create plain language reports. This process worked. Eight key themes were found that could help people to have a good life, such as having good relationships with family and friends; having a job; making personal choices; and being respected and included. The list was longer than previously reported in other studies. The Forum gave valuable insights and helped us think of new ideas for supporting people with Down Syndrome to speak up for themselves. Used thoughtfully, AI (Artificial Intelligence) could be a helpful tool in the future to help these people share their experiences and needs. More research is needed to understand how people with Down Syndrome can be more involved in making changes through advocacy projects where they take an active role.

1. Introduction

This is not a formal research paper. We wanted to devise and test a process for gathering information from people with Down Syndrome. We wanted to know how they felt about their lives. The information was collected at a one-day Forum for people with Down Syndrome. The article is written in simple, plain language. We have added some drawings and diagrams to help explain things. Two people with Down Syndrome helped write this article. We want to make it easier for everyone—not just academics—to understand. We hope this kind of study helps to collect useful ideas for future research.

Also, we believe that people with disabilities, along with their families and support workers, should have access to information. This article is just one modest example of how universities and researchers can do a better job of sharing what they learn with people who could create a better life for people with Down Syndrome.

1.1. The Rights of Persons with Down Syndrome

People with disabilities—whether physical, sensory, or intellectual—don’t always get the same chances as others. For example, people with Down Syndrome often miss out on education, job opportunities, and friendships [1]. This isn’t just in one country—it happens all over the world and has for many years.

In response, people with disabilities began speaking up for themselves and working for change. Many groups from different countries worked together to write a list of rights for people with disabilities. People with Down Syndrome and their families were involved. The United Nations, which includes 195 countries, also supported this work.

About 20 years ago, most countries agreed to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [2]. By early 2025, 192 countries had signed on. This means that people with disabilities can now use this agreement to ask for their rights from governments and service providers. But they still need support to learn about these rights and how to stand up for themselves [3].

People with intellectual disabilities, including those with Down Syndrome, often rely on others—like parents or teachers—to speak up for them. While this can help, sometimes people with Down Syndrome want to make their own choices, even if they’re different from what others expect. One review looked at 39 studies on the quality of life of adults with Down Syndrome. Only 8 studies actually asked people with Down Syndrome directly about their views—and most had small numbers and were from the USA [4]. These studies focused more on health and less on things like friendships or inclusion. This may reflect what professionals think is important, rather than what people with Down Syndrome want.

Two other studies from Australia [5,6] found that people with Down Syndrome wanted more relationships, more chances to be part of the community, and more independence—especially with work and where they live. Again, the number of people who took part was small.

Self-advocacy—speaking up for yourself—is not very common among people with intellectual disabilities, and even less so for people with Down Syndrome. But there’s growing evidence that it can work and make a real difference for people who take part in it [7]. Organisations like Down Syndrome International are trying to encourage this, and they have shared useful ideas [8].

But how can we collect the views of more people with Down Syndrome so that they can be shared with others? At the 2024 World Down Syndrome Congress in Brisbane, Australia (organised by Down Syndrome International and Down Syndrome Australia), over 1000 people attended. The day before the main event, there was a Forum just for people with Down Syndrome. It was a chance to hear from more people than ever before from different countries. The goal was to test a method that could be used again in other places to gather feedback from people with Down Syndrome or other intellectual disabilities.

We picked a broad topic: what makes life good for people with Down Syndrome? We thought that information technology—like the Internet and Artificial Intelligence (AI)—could help people with intellectual disabilities speak up and share their ideas more clearly [9]. After the Forum, we thought of different ways to help advocacy groups organise and share what was said. The “Method and Findings” sections below show how these reports could be written and used, for example, by people who fund or provide services.

1.2. Our Goals

We had three main goals for the self-advocates Forum at the 2024 Congress:

- To listen to adults with Down Syndrome about what they enjoy in life and what could make it better.

- To try out a method for collecting this kind of information that others could use in their own countries or communities.

- To explore how tools like the Internet and Artificial Intelligence (AI) could help people with Down Syndrome or other intellectual disabilities, gather and share their ideas and needs more easily.

2. How We Ran the Forum

The day before the 2024 World Down Syndrome Congress, we held a meeting just for people with Down Syndrome. It was called a Self-Advocates Forum. The event lasted all day, with breaks for food and rest. Almost 140 people from 7 countries came. Most were from Australia and New Zealand, but others came from England, Canada, the USA, Singapore, and Germany. There was a good mix of men and women. Nearly everyone was under 40, with most in their 20s or 30s.

We used a large room with round tables (see Figure 1: ChatGPT Image was used to convert photographs to drawings).

Figure 1.

The Room Layout.

Each table had about 6 to 8 people, with a mix of men and women. Some people brought a support person, who sat with them and helped if needed. Supporters helped in different ways—for example, repeating instructions, clarifying what the person said, translating into different languages, or using communication tools (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Using a Communication Aid.

At each table, there was another person who guided the discussion. People were very keen to talk, so they had to take turns and not talk over each other.

2.1. What We Did

The Forum was planned by a team led by Rachel (Down Syndrome Australia), Ruth (Down Syndrome Queensland), and Robin (Down Syndrome International).

To start the day, people did some fun activities at their tables to help everyone feel comfortable. Rachel and Ruth explained what the Forum was about and what we would be doing. They explained some ‘rules’ to guide the Forum and wanted to check if people would agree (consent) to them. We would write down what people said, but no one would be named, we would take photos so that others could see what we did, and afterwards, we would tell others what had happened. If anyone did not want to take part, they could stay and listen. People could ask questions, and Robin brought them a microphone so everybody in the room could hear. The facilitators at each table checked if people wanted to join in. All were happy to take part.

Roy gave a short talk about rights for people with Down Syndrome. Others joined him to show why speaking up for yourself is important.

Then Rachel introduced the first activity. The question was: “What are the good things in your life?” Everyone who wanted to share could do so, and supporters helped write answers on big sheets of paper. These were placed on tables so everyone could see their ideas being written down (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Recording What Was Said at Each Table.

When all the tables had finished, Robin and Andrew (a self-advocate leader from New Zealand) went around the tables, asking some people to share things they had written down. Other tables raised their hands if they had written the same thing.

After a short break, we started the second activity: “What things in your life could be better?” At each table, people explained why these things mattered to them, what made them hard to get, and what could help. Again, supporters wrote the answers on large sheets. Then it was time for lunch and rest.

During lunch, Rachel, Robin, Roy, and a few others read through all the answers and grouped similar ideas together into topics (themes). They wrote summaries on new sheets and put them on the walls around the room.

In the afternoon, groups of people walked around to read the summary sheets, then went back to their tables to talk. Robin and Andrew asked if anyone wanted to tell a personal story or share their wishes for a better life. Many people spoke—at least one from each table.

Then, people were given stickers (dots) and asked to vote by placing a dot on the ideas that mattered most to them. Later, we counted the dots to see which ideas were the most important. (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Summary of Themes.

In the final part of the day, volunteers at each table read out the top ideas, and everyone cheered if they agreed. We ended the day with songs and a group photo.

2.2. Sharing What Happened

On the final day of the Congress, five self-advocates and three supporters spoke on stage in a panel session. The audience included professionals, family members, and other people with Down Syndrome: everyone who had attended the Congress. Roy asked the panel questions so they could tell everyone what happened at the Forum and what people said would make their lives better. They finished by inviting everyone to sing and dance to the song “Roar” by Katy Perry, which has the line: “You held me down but I got up, ‘cause I am a champion and you’re gonna hear me roar!”. This song was chosen by the Forum participants.

2.3. What We Did After the Forum

After the Forum, we wondered how we could tell others about how the Forum was run, and also the things that people had identified that would make their lives better. Here’s what we did: we took photos of the big paper sheets.

- There were 20 sheets about the good things in people’s lives.

- There were 24 sheets about what could be better.

We read the words out loud into a voice recorder on a smartphone. This took about an hour.

Then we used a free website called TurboScribe to turn the recording into written words. It only took about two minutes. We couldn’t record the table conversations because the room was so loud and busy. But a recording on a smartphone could be done in smaller groups in the future.

To help organise the information, we used ChatGPT 5.0 (an example of Artificial Intelligence: ‘AI’). We uploaded the text and asked it to group the answers into themes. The people who invented ChatGPT (https://chatgpt.com/share/69078716-2d9c-800c-a537-0b22efb3b0e7, accessed on 15 August 2025) describe an approach that is very similar to when humans make a thematic content analysis of what people say or have written down [10]. AI gave us clear lists and examples in just a minute. We did the same thing for both sets of answers:

- What people liked about their lives

- What they wanted to improve

Roy double-checked the AI results with the original paper notes and the grouping of themes made at the Forum. He prepared a summary of the themes and examples from the sheets and asked first Rachel and Leigh, and then Robin and Catherine (the authors of this article) to check the information and how it had been written. They felt that the words used were sometimes difficult to understand. AI (Microsoft Co-Pilot) was used to create a plain English version. All the authors checked that this was correct.

We realised that other people with Down Syndrome, for example, might find it hard to read the written list. So, we tried out a free AI tool called Amazon Polly (https://aws.amazon.com/polly/, accessed on 15 August 2025) to turn the words into speech. People could listen to what was written instead of reading the words.

We also tried an AI tool called NotebookLM (https://notebooklm.google/, accessed on 15 August 2025), which turned the written notes into a conversation between two people (like actors). This could be helpful for training sessions in the future.

3. Our Findings—What Matters in the Lives of People with Down Syndrome

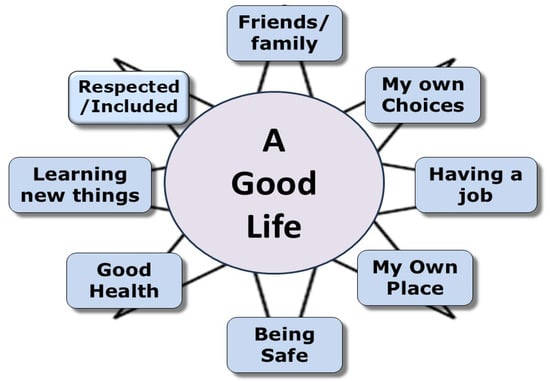

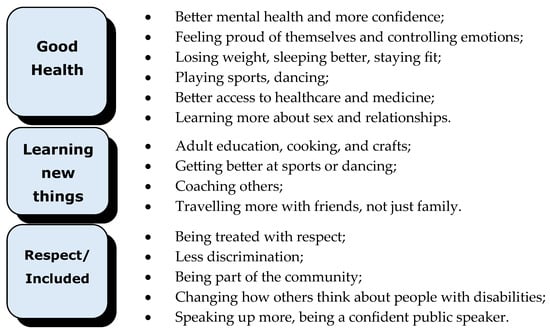

We felt the Forum had been successful. One way of judging this is to describe the information that had been gathered from the people with Down Syndrome who took part. Figure 5 shows the eight big topics people talked about most.

Figure 5.

The eight things that made life good.

Everyone had different ideas—what made one person happy was not always the same for someone else.

Some people talked about just one thing that would make their life better, while others spoke about many ways life could be better. A few people said they couldn’t think of anything they would change.

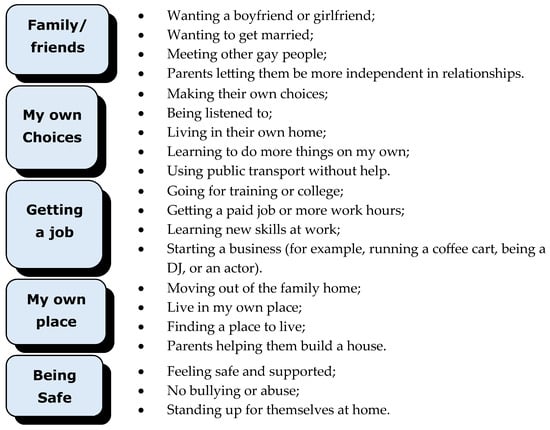

Below are examples of what people shared (Figure 6). These words are taken from the big paper sheets at the Forum. Many others were listed, but these were the more common or novel ones.

Figure 6.

Examples of Each Theme.

- Some people also shared other dreams and ideas for a better future:

- Stopping pollution and littering.

- Ending animal cruelty.

- Feeling sad when people or pets die.

- Wanting to become a motivational speaker.

- Taking leadership roles and speaking up for others with Down Syndrome.

Many more things were said at the Forum that had not been reported by previous studies.

4. Discussion—What Did We Learn?

The Forum brought together nearly 140 people with Down Syndrome from Australia and other countries. It may have been the biggest ever meeting of its kind. This was a good opportunity to listen to their voices. We worked out a plan for how to do this with such a large number of people, but we think it might work even better with smaller groups.

Certain things helped to make the plan work. The big group was divided into smaller groups sitting at a round table so that people could see and hear each other. There was a facilitator (support worker) at each table to ensure everyone was heard. People were keen to talk, and they were reminded to take turns and not to talk over each other. Those who were not so good at talking needed extra time and help from their supporters, especially if they used sign language, a communication aid or non-verbal signs.

The facilitator made sure what people said was written down. Group members volunteered to do this. The list was read out at the end of the session to remind people what had been said. If anything had been left out, it was added.

Many of the people who attended the Forum had already been part of local self-advocacy groups. They likely had strong support from family and had good education and social opportunities. And they got to travel to Brisbane for the Conference. Hence, the plan may have to be taken at a slower pace for people who are less used to speaking up and for those with communication difficulties. For example, this may need to be done over a series of sessions rather than a one-day event.

Two further tips are listed:

- Take your time. Don’t rush the process. People need time to feel comfortable and to think. Breaks help people relax and connect. Include some fun activities.

- Use visual tools. Writing and pictures help people see that their ideas have been heard. These can be saved and shared later.

4.1. Use of Artificial Intelligence

We also used Artificial Intelligence (AI) after the Forum to help organise and share what people said. As we have described, the Internet and AI helped us achieve the following:

- Turn recorded voices into written text.

- Sort ideas into themes quickly.

- Convert text into speech so people could listen instead of reading.

- Create role-play conversations from the written summary.

- Find previous research studies through use of tools such as Google Scholar.

- Write our report in plain language.

- Converted photographs to drawings.

These tools made communication easier and quicker. However, AI was used solely by the facilitators (Rachel, Robin and Roy) rather than our co-authors with Down Syndrome (Leigh and Catherine). Nonetheless, they too gained from the outcomes of our use of AI. But we know AI must be used carefully, and the outcomes from it must be double-checked with the people who provided the information [11]. In the future, people with Down Syndrome and their supporters should be encouraged to learn how to safely use AI in education, vocational training and employment settings. Then they too will benefit from its promised advantages [12].

We hope others will study how AI can be used in a good and helpful way for their voices to be heard and their knowledge and skills enhanced. For example, AI could help people with Down Syndrome to play an active part in research projects based on the model of ‘inclusive research’ teams consisting of university-based scholars and co-researchers with the lived experience of disability [13,14]. Also, research aimed at improving people’s lives—called participatory action research—needs to support people with the lived experience of disability to be active participants in their projects [15]. There are examples of people with Down Syndrome being involved in such projects [16,17]. Also, training resources have been developed to prepare people with intellectual disabilities to engage in research projects [18,19].

4.2. Towards a Better Life

We learned two big lessons from the Forum:

- Like everyone else, people with Down Syndrome can have good lives.

The Forum showed that people with Down Syndrome can clearly explain what makes their lives good. This was special because the information came directly from them—not from parents or professionals who were the main informants in most published studies. Even so, the Forum members confirmed what earlier research found as noted above [4], but also gave us new insights, as the long list presented in Figure 6 shows. This may be because of the large number of people who took part. Each of them had different experiences and desires for a better life because more people from different places took part. Also, people came from many different places within the country as well as from different countries. This has rarely happened before.

- People with Down Syndrome should be listened to when decisions are made.

The eight main topics discussed at the Forum can help guide important conversations. For example, when making school or work plans [20] or when planning support through programmes like Australia’s National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) [21].

One limitation of the Forum was that we found out what matters to people, but we didn’t have time to work on how to make changes happen. That would need more time—maybe many days—and would be better done in small local groups, not at one big event.

For example, a local Down Syndrome association could help a small group of self-advocates focus on one topic (like jobs or housing). They could work on a plan to create change in their own town or region. These kinds of small groups are also a great way to learn new skills. Future World Down Syndrome Congresses should include chances for people with Down Syndrome to do action planning in small groups on the themes from this Forum.

Finally, this Forum added to what we already know about the quality of life for people with Down Syndrome in countries with developed support systems. But in many other parts of the world, people face different barriers. Even though many countries have signed the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, those rights are not always a reality. Advocacy—especially when people with Down Syndrome speak for themselves—is one of the best ways to create change. It’s not always easy, but it works. An example from South Africa showed how advocacy helped reduce unfair treatment of people with Down Syndrome [17]. We hope more of this happens around the world in the years ahead. Many people with Down Syndrome are capable of speaking for themselves.

5. Conclusions

The International Conference offered an opportunity to try out a plan for listening to the participants with Down Syndrome. The way we collected information at the Forum gave us deep and meaningful ideas. It also showed how we can support people with Down Syndrome to speak up for themselves and share their views. Artificial Intelligence (AI) proved to be a useful tool. Used thoughtfully, it can help people with Down Syndrome gather and explain what they want and need in life. It helps to rebalance existing knowledge that is currently dominated by the perceptions of parents and professionals. More research is needed to explore how people with Down Syndrome can take part in projects that aim to make real changes in their communities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S. and R.G.; Methodology, R.S., R.G. and R.M.; Data curation, R.S., R.G. and R.M.; Formal analysis, R.M.; Validation, L.C. and C.W.; Writing—original draft, R.M.; Writing—review and editing, R.S., R.G., L.C., C.W. and R.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Formal ethical approval was not required for this evaluation under UK Research and Innovation Guidance. However, this study adhered to the seventh revised version W.M.A. of the Helsinki Declaration on Medical Research involving Human Subjects issued on 19 October 2013.

Informed Consent Statement

Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants who took part in the Forum. The event was attended by over 140 persons with Down Syndrome who had registered with the conference and who came from various countries. It would have been impractical to obtain written consent from them on the day (many would have reading and writing difficulties), and still less from their parents/guardians many of whom would not have been in Brisbane at the conference. Instead we took verbal consent as described in the paper.

Data Availability Statement

The written information is available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Our thanks goes to the conference committee for the 2024 World Down Syndrome congress for arranging sponsorship for the Forum and Down Syndrome Australia for organising the Congress (https://www.downsyndrome.org.au/news-events/world-down-syndrome-congress-2024/, accessed on 15 August 2025). We are grateful to the volunteer facilitators and supporters at each table and all the participants who so enthusiastically took part in the Forum.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in relation to this article.

Disability Language/Terminology Positionality Statement

We use the term people with Down Syndrome in keeping with the United Nation Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. It was the preferred terminology of the World Congress and futher endorsed by participants at the Forum, arguing that they were people first.

References

- Down Syndrome International. About Down Syndrome’ Information Pack. Available online: https://ds-int.org/about-down-syndrome/ (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. 2006. Available online: http://www.un.org/disabilities/ (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Frawley, P.; Bigby, C. Reflections on being a first generation self-advocate: Belonging, social connections, and doing things that matter. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 40, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijezie, O.A.; Healy, J.; Davies, P.; Balaguer-Ballester, E.; Heaslip, V. Quality of life in adults with Down Syndrome: A mixed methods systematic review. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, M.; Foley, K.-R.; Bourke, J.; Leonard, H.; Girdler, S. “I have a good life”: The meaning of well-being from the perspective of young adults with Down Syndrome. Disabil. Rehabil. 2014, 36, 1290–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jevne, K.W.; Kollstad, M.; Dolva, A.-S. The perspective of emerging adults with Down Syndrome—On quality of life and well-being. J. Intellect. Disabil. 2021, 26, 839–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilley, E.; Strnadová, I.; Danker, J.; Walmsley, J.; Loblinzk, J. The impact of self-advocacy organizations on the subjective well-being of people with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review of the literature. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2020, 33, 1151–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Down Syndrome International. Self-Advocacy Group Guide. 2025. Available online: https://ds-int.org/self-advocacy/ (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Birhane, A.; Isaac, W.; Prabhakaran, V.; Díaz, M.; Elish, M.C.; Gabriel, I.; Mohamed, S. Power to the People? Opportunities and Challenges for Participatory AI. 2024. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/2209.07572 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qual. Psychol. 2022, 9, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Regional Information Centre for Western Europe. Building an Accessible Future for All: AI and the Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities. 2024. Available online: https://unric.org/en/building-an-accessible-future-for-all-ai-and-the-inclusion-of-persons-with-disabilities/ (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Chubb, J.; Cowling, P.; Reed, D. Speeding up to keep up: Exploring the use of AI in the research process. AI Soc. 2022, 37, 1439–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, P.; Garcia Iriarte, E.; Mc Conkey, R.; Butler, S.; O’Brien, B. Inclusive research and intellectual disabilities: Moving forward on a road less well-travelled. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St John, B.; Mihaila, I.; Dorrance, K.; DaWalt, L.S.; Ausderau, K.K. Reflections from co-researchers with intellectual disability: Benefits to inclusion in a research study team. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2018, 56, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevenson, M. Flexible and Responsive Research: Developing Rights-Based Emancipatory Disability Research Methodology in Collaboration with Young Adults with Down Syndrome. Aust. Soc. Work 2010, 63, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccarino, F.; Vaccarino, Z.; Armstrong, D.; Borkin, E.; Hewitt, A.; Oswin, A.; Quick, C.; Smith, E.; Glew, A. Self-advocates with Down Syndrome research the lived experiences of COVID-19 lockdowns in Aotearoa New Zealand. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2023, 36, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGlinchey, E.; Fortea, J.; Vava, B.; Andrews, Y.; Ranchod, K.; Kleinhans, A. Raising awareness and addressing inequities for people with Down Syndrome in South Africa. Int. J. Equity Health 2025, 24, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuffrey-Wijne, I.; Lam, C.K.K.; Marsden, D.; Conway, B.; Harris, C.; Jeffrey, D.; Jordan, L.; Keagan-Bull, R.; McDermott, M.; Newton, D.; et al. Developing a training course to teach research skills to people with learning disabilities: “It gives us a voice. We CAN be researchers!”. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 2020, 48, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research Engagement and Advocacy for Diverse Individuals (READI) Curriculum. Available online: https://ausderau.waisman.wisc.edu/hret/readi/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Alkahtani, M.A.; Kheirallah, S.A. Background of Individual Education Plans (IEPs) Policy in Some Countries: A Review. J. Educ. Pract. 2016, 7, 5–26. [Google Scholar]

- Understanding the National Disability Insurance Scheme. 2025. Available online: https://www.ndis.gov.au/understanding/how-ndis-works (accessed on 15 August 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).