Abstract

Diagnoses of ADHD in adults continue to increase, and the number of college students with ADHD has risen in particular. Qualitative research on this population has been common, but it is not clear what conclusions can be drawn from this research base. We conducted a review of the qualitative research on college students with ADHD over a 20-year period (2002–2021). A systematic search yielded 41 papers that were reviewed in detail. Studies were grouped into four topic areas, with the most researched area being the college experience for these students. Most sample sizes were small, with a median of 10 participants, and most studies used students’ self-reports of having ADHD as the sole method of diagnosis identification/verification. Very few studies (7.3%) included a comparison group of students without disabilities. These results suggest that the qualitative research base on college students with ADHD has significant limitations, including difficulties with generalization, uncertainty regarding diagnostic accuracy, and an inability to make comparative statements about students with vs. without ADHD.

1. Introduction

Adult diagnoses of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are increasingly common, with the proportion of adults in the United States with a diagnosis more than doubling between 2007 and 2016 [1]. One sizeable segment of young adults with diagnoses is college students. About 20% of college students identify as having a disability [2], and over 20% of those students with disabilities report having ADD/ADHD as a primary diagnosis, the most common primary diagnosis reported [3].

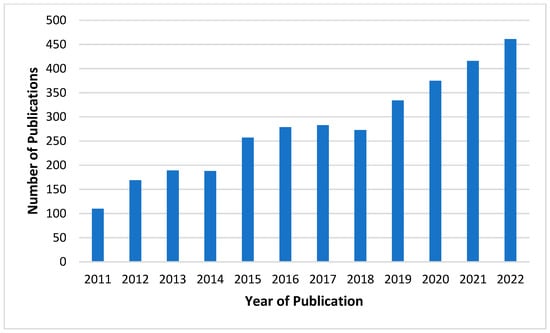

Research on college students with ADHD has expanded accordingly; as an index of this expansion, a Google Scholar search showed a continuous increase in the number of publications from 2011 to 2022 that included the phrase “college students with ADHD” (see Figure 1). Much of this literature has been quantitative in nature, either experiments involving interventions for those with ADHD or correlational studies examining various characteristics of this population. For instance, research has found that college students with ADHD have lower GPAs than their nondisabled peers [4], they are more likely to have problems with anxiety [5], and they generally benefit from cognitive behavioral therapy [6]. They have also been shown both to benefit from the proper use of ADHD medication and to misuse the medication at higher rates [7].

Figure 1.

Publications on college students with ADHD by year, 2011–2022.

1.1. Qualitative Research Methods

There have also been many qualitative studies on college students with ADHD, and this research approach has been particularly popular among doctoral students completing dissertations in education and related fields. The American Psychological Association (APA) [8] defines qualitative research as “a method of research that produces descriptive (non-numerical) data” with the goal of investigating “how individuals can perceive the world from different vantage points”. For most of scientific psychology’s history, quantitative methods have been prized for their precision and for their similarity to methods used in biology, chemistry, and other natural sciences. However, in recent years, qualitative research has become more prominent. The APA started a designated qualitative research journal in 2013 (Qualitative Psychology), and mainstream psychology journals have been publishing more qualitative work as well [9]. Now, many researchers acknowledge that quantitative and qualitative designs each have advantages and disadvantages.

There are reasons to think that qualitative research could contribute uniquely to our understanding of college students with ADHD. Open-ended and less structured methodologies may yield information on topics that researchers would not think to ask about specifically, and students might describe experiences that cannot easily be captured by quantitative ratings or the endorsement of pre-set statements. On the other hand, the small sample sizes and the types of subjectivity that are common in qualitative research may lead to difficulty in generalizing the results and even to biased conclusions due to researchers’ tendency to “see themselves” in their participants [10,11].

Like quantitative research, qualitative research studies vary greatly in terms of their specific methodologies, as well as their methodological rigor [12]. One team of researchers has suggested “quality indicators” of qualitative research, such as (a) whether the study design allowed for sufficiently in-depth investigation with, e.g., multiple participants or multiple data sources; (b) whether the write-up contains a sufficiently detailed description of the data analyses; and (c) whether findings are reported with “thick, detailed” descriptions, such as quotations from participants [13].

1.2. The Present Study

The purpose of the present study was to examine a cross-section of qualitative research on college students with ADHD, to determine how this work is typically being done, as well as to evaluate what conclusions can be drawn from this body of work. Specifically, we were interested in (a) what specific topics the qualitative literature investigated; (b) the sample size; (c) whether non-ADHD students were included as a comparison group; and (d) how the researchers operationally defined “ADHD”.

Because we reviewed studies that investigated very different types of research questions, it was not possible to perform a typical meta-analysis. Moreover, given the difficulties in summarizing even individual detailed qualitative studies (particularly when they range in topical focus), we chose to review a cross-section of the qualitative literature rather than attempting an exhaustive review.

2. Materials and Methods

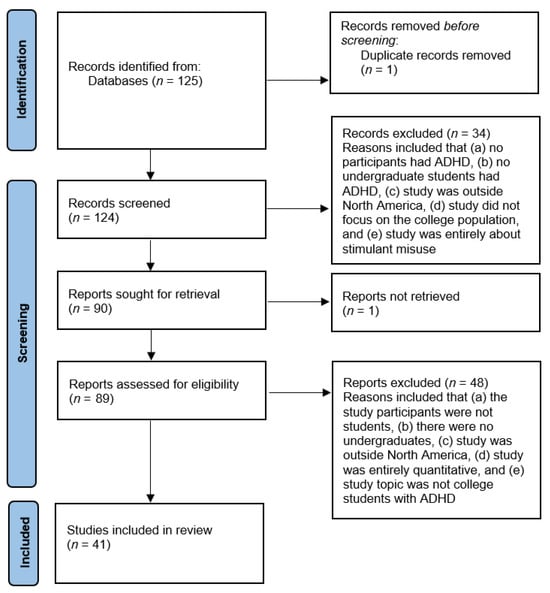

For this review, we followed the modified Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, outlined in Figure 2 below. Of note, our analyses examined a cross-section of this literature, as determined by the coding and organization of our core databases.

Figure 2.

Flow chart showing study selection process. Although 125 articles were initially retrieved from the databases, 1 was a duplicate, 34 had abstracts showing that they did not meet the inclusion criteria, and 1 other study was not available in full-text format (despite considerable efforts). Then, 89 articles were obtained in full-text format, and 48 of these were excluded due to not meeting the inclusion criteria, leaving 41 for review.

2.1. Search Strategy

Our inclusion criteria were as follows. The included studies’ participants needed to (1) include more than one individual with ADHD, (2) include undergraduate students with ADHD, and (3) be located in the US or Canada during the study; the study itself needed to (4) utilize qualitative methods, (5) focus on students in a postsecondary setting, and (6) not focus specifically on the misuse of ADHD-related medication. If the studies met these criteria, we included them, even if the studies also included students who were not undergraduates, or if the studies also included quantitative data (making them mixed methods), and regardless of which postsecondary setting the study took place in (e.g., community colleges, 4-year schools).

Using the EBSCO library, on 3 October 2022, we searched psychology (PsycINFO) and education (ERIC) databases for articles that included terms surrounding ADHD and college students (“ADHD” or “attention deficit disorder” or “attention deficit hyperactivity disorder” and “college students” or “university students” or “postsecondary students”). We limited our search to documents written in English that were published during a 20-year period between 1 January 2002 and 31 December 2021. Finally, given our interest in qualitative studies, we leveraged database categorization to limit the results to those tagged as a qualitative study, interview, or focus group. After removing duplicates (n = 1), our final search yielded 124 results.

2.2. Study Selection

To further narrow our review to articles that included research on college students with ADHD, we reviewed the abstracts of the initial 124 results and applied six additional criteria: the studies’ participants needed to (1) include more than one individual with ADHD, (2) include undergraduate students with ADHD, and (3) be located in the US or Canada during the study; the study itself needed to (4) utilize qualitative methods, (5) focus on students in a postsecondary setting, and (6) not focus specifically on the misuse of ADHD-related medication. Ninety of the 124 articles met these criteria, meriting the review of the full paper. One of these articles was inaccessible, despite considerable efforts, leading to a reviewed sample of 89 studies.

A coding process was used to make decisions about whether to include articles in the literature review (i.e., whether the article met the inclusionary criteria). The coders had advanced graduate training in ADHD and/or substantial experience with diagnostic documentation. Coding was completed under the supervision of a licensed psychologist with extensive experience in publishing ADHD research. The coders determined whether the inclusion criteria were met in an “all-or-nothing” style; articles that met all inclusion criteria were coded “yes”, but, if any of the criteria were not met, we coded the article “no” and noted which criteria were not met. Coding reliability was determined through the “percent agreement” of an initial set of 18 articles (20% of article set). Of the 18 coded files, we calculated the percentage of the 20 values that agreed across the two coders. The researchers placed both sets of variables in the same SPSS file and ran a “crosstabs” analysis. Once the percent agreement was deemed sufficient (>90%), the remainder of the articles were single-coded. During this stage of the review, most studies that were excluded were removed because they lacked qualitative designs. Please see Figure 2 for a complete flow chart showing the study selection process; the flow chart is derived from documents developed by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) consortium [14].

2.3. Variable Identification

The authors identified several categories of variables to collect from each article, including (a) the paper publication characteristics (dissertation/journal article/book chapter, publication year), (b) the sample characteristics (sample size of students with ADHD; sample composition regarding gender, ethnicity, undergraduate status; inclusion of non-disability comparison group; exclusive focus on ADHD vs. inclusion of students with other disabilities), and (c) the method of determining the ADHD status (self-reported diagnosis, unstandardized self-reported symptoms, clinical evaluation performed during research process, registration with disability services, objective performance measures given, historical records reviewed, standardized self-reports of disability-related symptoms).

A very similar coding process to the one described above in Section 2.2 was used again to ensure the reliable recording of the variables mentioned. However, because it was often somewhat unclear exactly how the reviewed studies had determined that their participants had ADHD, this variable was double-coded for all studies, and disagreements were resolved by discussion and consultation with the senior researcher.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Results

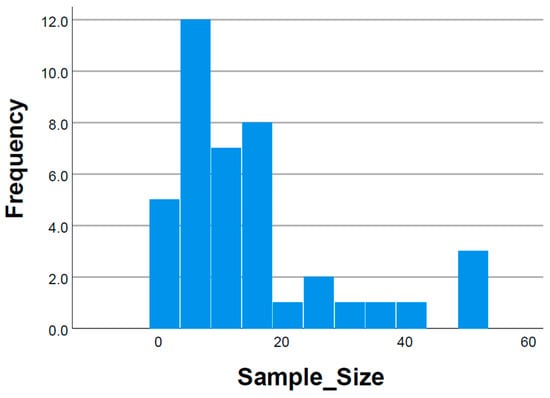

Forty-one studies were included in the final set. Of these results, 63.4% were dissertations/theses and 36.6% were journal articles. The studies had a mean sample size of 15.1 (standard deviation = 13.4; median = 10), with smaller sample sizes for dissertations (mean = 10.6) and larger sample sizes for journal articles (mean = 22.9). Figure 3 shows the distribution of the sample sizes.

Figure 3.

Total sample sizes of each qualitative study analyzed by our review.

Nearly all (95.1%) studies presented demographic information on the gender composition of the sample (mean sample composition = 41.6% male), yet only 80.5% included racial demographic information (n = 33). The most frequent racial/ethnic groups represented in the samples were White (n = 29), Hispanic/Latino (n = 17), Black/African American (n = 14), and Asian/AAPI (n = 10). The average percentages of the sample compositions were 65.4% White, 15.7% Hispanic/Latino, 23% Black/African American, and 14.9% Asian/AAPI.

In our review of these studies on ADHD in college students, over a third (39%) had samples of college students who had ADHD and another disability. However, only 7.3% of these studies included a comparison group of students without disabilities. In determining participants’ ADHD status, 41.5% of studies used more than one determination method (mean = 1.6). Over 73% of the reviewed studies used recruitment through or registration with either disability services or an on-campus clinic as an indicator of an ADHD diagnosis. Meanwhile, 53.6% of the included studies used self-reported diagnosis alone to determine the ADHD status. Moreover, 14.6% of studies used standardized self-reports of ADHD symptoms to determine participant inclusion. The study researchers conducted their own clinical evaluations to determine the ADHD status for inclusion in only 7.3% of studies. Only 2.4% of studies used objective performance measures outside of clinical evaluations to determine participants’ ADHD status.

3.2. Qualitative Results

Using the abstracts of these 41 studies and the data collected on each variable, the investigators identified broad themes stretching across these studies for preliminary grouping. The investigators then discussed and collaborated to create four core thematic groups: (1) the college experience of students with ADHD (n = 18), containing the subgroups of college transition (n = 5), ADHD as an identity (n = 8), and identity-based subgroups (n = 5; specifically, examining students from different ethnic groups and those at community colleges); (2) interventions (n = 9), with the subgroups of coaching (n = 4), strategies (n = 2), and medication (n = 3); (3) cognitive and academic functioning (n = 5); and (4) self-functioning (n = 9).

Given the differences in the methods, research questions, and presentation of results across studies, we wrote a qualitative summary of each study to assist readers in understanding what has been learned (see Appendix A). However, we also provide below a synthetic summary of all studies.

3.2.1. The College Experience of Students with ADHD

The largest group of documents that we found described qualitative studies investigating the college experience of students with ADHD (n = 18). Several of these documents discussed the process of transitioning to college (typically from high school). The studies reported that students with ADHD needed specialized self-management strategies, benefited from family support, and looked forward to the increased independence of college. Across the papers on the transition to college, the positive effects of relationships with family members—parents in particular—appeared to be the most prominent theme.

Other studies of the college experience focused on the students’ ADHD as being an identity and how this identity impacted students’ subjective experience of college. These studies noted the ambivalence that students felt about utilizing disability accommodations (feeling that the accommodations were needed and yet worrying about the stigma of using them); the impact of formal disability documentation requirements on their identity; and how students who had been diagnosed with ADHD earlier in life had the opportunity to experience more parental support but also had less control over the students’ understanding of ADHD.

Finally, five of the studies on the college experience examined specific subgroups of students. Studies of African American students with ADHD documented that many of the phenomena observed in other studies held true for African American students as well. Two other studies also extended previous findings to students with ADHD who were studying at community colleges. Finally, a study of Chinese American college students with ADHD suggested that cultural factors sometimes prevent students’ families from seeking early treatment for ADHD.

3.2.2. Interventions

The next largest group of studies examined various types of interventions for college students with ADHD (n = 9). Of these, the intervention studied most often was coaching. Coaching studies found that coaching was a generally effective intervention, but it was less clear which specific components of the coaching relationship (e.g., providing students with tools and resources vs. providing praise and consequences) were most effective. Other studies examined a more general set of strategies that were associated with success for college students with ADHD, finding that the support of others—family members, teachers, and peers—was perceived as extremely important, both in enabling students to enter college and allowing them to succeed once there.

Finally, three studies examined medication as an intervention for college students with ADHD. Students reported ambivalence about ADHD medication, citing benefits for academic performance but also a variety of concerns: stigma about medication use, the side effects of the drugs, and worries that they were not their “authentic” selves while on medication.

3.2.3. Cognitive and Academic Functioning

Five studies examined the cognitive and academic functioning of college students with ADHD. These studies investigated a remarkably diverse set of aspects of functioning. One study examined how college students with ADHD learned a mathematical concept, finding that the abstract aspects of math were more difficult to learn. Other studies found that students taking computer-based tests would prefer to have only one question on the screen at a given time; that students reported avoiding difficult tasks due to those tasks having insufficient structure; that students actually preferred tests to other assessment methods in courses; and that students checked the time very frequently due to anxiety about losing time.

3.2.4. Self-Functioning

Finally, eight articles examined the “self-functioning” (i.e., personality and general psychological functioning) of college students with ADHD. This set of articles was also quite diverse in terms of the topics studied. The findings from these studies included the following: students often doubted their abilities and their decision to attend (or stay at) college; students described what one set of researchers called the “chaotic” effects of their ADHD symptoms on their lives and experiences; students reported generally high self-efficacy but indicated needing more time to complete tasks; and students reported longer-term projects to be more difficult, thus making choices to set short-term interim goals to maximize their chances of success.

4. Discussion

The purpose of the present review was to examine qualitative research on college students with ADHD. We found that most qualitative studies on this topic had small sample sizes (with a median of 10 participants), and a substantial number of the reports (almost 20%) failed to report the racial/ethnic identities of the participants. Notably, less than 10% of studies had a nondisabled comparison group, and most studies did not conduct their own assessments to validate students’ self-reports of an ADHD diagnosis. The specific topics of the studies were organized into four groupings. The most common topic area was the college experience, followed by interventions, self-functioning, and finally cognitive and academic functioning.

Several years ago, Madaus et al. [15] reviewed the extant literature on postsecondary disability services and arrived at a negative conclusion, describing that the research “lacks significant depth, has poor sample and setting descriptions, and lacks methodological rigor” (p. 133). To be clear, these scholars were not singling out qualitative research but were commenting more generally about the literature. In a later article, Madaus et al. [16] offered suggested research guidelines with “quality indicators”. It is interesting to interpret our results through the lens that these two papers provide. In particular, Madaus et al.’s [16] first set of quality indicators involved the complete description of samples, including clear and detailed information about race and ethnicity (an aspect that we found lacking).

As Madaus et al. [15] noted, qualitative research studies tend to have small sample sizes, and, while understandable (since each participant generates rich and detailed data), this decreases their generalizability. Many qualitative researchers explicitly state that generalizable conclusions are not their goal (instead, understanding their particular sample in detail is the goal), but this limitation means that practitioners may not be able to learn as much about their own college students with ADHD by reading the qualitative research literature.

A different limitation is presented by the fact that so few studies included any nondisabled comparison participants. Many studies concluded with claims about what college students with ADHD “are like”, with the implication being that the participants’ ADHD was associated with these characteristics. For instance, various studies that we reviewed noted that students with ADHD avoid difficult tasks, use self-rewards to motivate themselves, and experience challenges in adjusting to college life initially. All these claims may be true and may even generalize beyond the researchers’ samples to be typical features of students with ADHD. However, without a nondisabled comparison group, there is little reason to suspect that these phenomena are caused by ADHD or even associated with it. Students without ADHD may exhibit the same phenomena and with the same frequency. Indeed, large-scale quantitative research has shown that many ADHD symptoms and related academic complaints are “high-base-rate” occurrences in college students. In other words, many students with and without ADHD describe these symptoms and complaints. For instance, Lewandowski et al. [17] found that most college students reported being easily distracted, and Suhr and Johnson [18] found that two thirds of college students reported at least sometimes not performing well on exams, even when they were familiar with the material. If only college students with ADHD were sampled and these phenomena were reported, the researchers might erroneously conclude that these features are associated with ADHD.

A final limitation of the literature base is related to how the samples in these studies were selected. Most of the time, the researchers simply relied on students self-identifying as having ADHD. The researchers in these studies did not even obtain self-reports of specific symptoms, use objective performance measures, or conduct (or inspect) comprehensive evaluation reports. At the very least, relying on self-identification as having ADHD would be expected to yield a very heterogenous group of participants, since different identification techniques will yield widely varying groups of students [19]. Some self-identified students likely completed comprehensive diagnostic evaluations, whereas others may not have. Given concerns about the overdiagnosis of ADHD [20], more rigorous methods of sample identification would seem preferable.

5. Conclusions

Studying college students with ADHD using qualitative methods appears to be a relatively popular undertaking, and the resulting research reports may provide interesting information about the students in these samples. However, there are significant limitations to the qualitative literature base, including small sample sizes (limiting generalizability), few nondisabled comparison groups (preventing even correlational conclusions), and a lack of rigor in the definition of ADHD (yielding heterogenous samples).

Two limitations to the present literature review should be considered, and they point to future research directions as well. First, we only reviewed qualitative research, and so none of our findings should be construed as providing a comparative judgment about qualitative vs. quantitative research in this area. We did not review quantitative research and cannot speak to its nature in this area. Further research might make such a comparison. Second, even within the qualitative literature, we did not compare studies that came from different methodological traditions (e.g., methodology, grounded theory, etc.) to examine if and why there may be a relationship between these traditions and the variables that we recorded. This would be another direction for future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L.C., K.S., and B.J.L.; methodology, S.L.C., K.S., and B.J.L.; formal analysis, S.L.C., K.S., and B.J.L.; writing—original draft preparation S.L.C., K.S., and B.J.L.; writing—review and editing, S.L.C., K.S., and B.J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Summaries of Included Studies

Appendix A.1. The College Experience of Students with ADHD

Among the studies in our literature review, 17 pertained to the college experience of students with ADHD: five on the transition to college, three on race, two on community colleges, and seven on ADHD as an identity.

Appendix A.1.1. College Transitions

Five of the studies in our sample examined the experience of transitioning to college for students with ADHD. Meaux et al. [21] studied the lived experience of 15 students with ADHD who were attending college and living away from their parents. Semi-structured interviews yielded three global themes that each had hindering factors and helpful factors: (1) gaining insights about ADHD; (2) managing life; and (3) utilizing sources of support. While many students transitioning to college experience a trial-and-error approach to finding self-management strategies that work for them, Meaux et al. argued that students with ADHD required more extreme self-management strategies, often learned after a negative experience. As students became increasingly aware and accepting of their ADHD diagnosis, they were better able to manage their symptoms. Additionally, students also transitioned from viewing their parents as primary sources of information to their peers, which parallels the developmental changes in students without ADHD.

Morgan [22] used a three-interview series to examine the college transition experiences of eight first-year students with ADHD attending a midwestern university. Like Meaux et al. [21], Morgan collected information on students living away from their parents. Morgan found that, despite the distance, families played an important role in these students’ transitions to college, including the parental management of ADHD (e.g., doctor’s appointments and medication coordination, where medication was seen as the primary form of ADHD treatment). Additionally, most students in the sample appreciated the campus resources available, but only half took advantage of them, instead relying on strategies from high school. Students reported stress in the face of new freedoms and independence, and especially in reaction to the challenge of college coursework. Medications were reported to be critical to students’ success in college.

McCall [23] considered the college transition experiences of young adults with disabilities, conducting a series of phenomenological interviews with one student with ADHD and three students with other varied disabilities. The analysis considered all four interviewees and established themes across the entire sample. Similar to our other studies, the student with ADHD in McCall’s study benefited from parental involvement in managing their ADHD and utilizing disability support services in college, including obtaining an initial diagnosis and requesting accommodations. McCall found that self-advocacy skills, inclusive educational experiences, and supportive family members were important for a successful college transition across all four participants and disabilities represented.

Denson’s [24] qualitative case study of eight students with ADHD transitioning to college involved two interviews: one at the beginning of the college transition, focused on high school preparation, and another towards the end of the first year, about the college experience. Students looked forward to the increased independence but had room to develop further self-advocacy skills to aid their success in college. Students had an awareness of the available support but found the support and accommodations to be insufficient, perfunctory, or “available but not readily available”. Students also wanted support that was specifically focused on aiding in this transition and easing into their new independence. Family played an important role in these students’ transitions, echoing Morgan [16].

Finally, Stevens [25] focused on the parental support of college students with ADHD. Leveraging an online self-report of symptoms and one-on-one interviews, Stevens examined first- and second-year students and found two core themes: parental support (both short- and long-term) and the renegotiation of the parent–child relationship. The participants were in frequent contact with their parents, which helped to provide structure. The participants in this study reported positive improvements to the parent–child relationship when the student exhibited increased self-regulation and set boundaries with their parents, as well as when the parents encouraged the participants’ increasing autonomy and also set boundaries. Nevertheless, the participants felt conflicted about how much parental involvement they wanted. Stevens suggests that this renegotiated parent–child relationship may increase students’ self-efficacy while also contributing to a sense of overwhelm as they navigate college on their own.

Appendix A.1.2. ADHD as an Identity

Eight papers explored ADHD as an identity. In 2013, Mullins and Preyde [26] explored the lived experience of “invisible disabilities”, including ADHD, among Canadian college students. Using in-depth, semi-structured interviews, the researchers found that students perceived their university to be generally accommodating and accepting. Students reported encountering social and organizational barriers in college, stemming from a lack of understanding of and negative attitudes towards invisible disabilities. Because of this, students reported that they faced challenges with the validation of their disability, negative perceptions, and a need to proactively disclose more information about their disability; some even wished for a visible disability to counteract these challenges. The study also showed students’ beliefs in the necessity of accommodations, but also their discomfort of disclosure and being “outed”, as well as the barriers that they were required to overcome to complete the accommodations request process. Students perceived that accommodations requiring faculty involvement were contingent on the faculty’s subjective judgments, leading the researchers to call for further universal instructional design.

Johnson’s [27] study examined the challenges and academic successes of eight college students with ADHD. Using questionnaires, as well as individual and group interviews, the researchers uncovered five main themes: (1) factors in academic success (e.g., family/peer support, university resources, university schedule, and small class sizes); (2) environments and learning styles (e.g., controlling distractions, hands-on learning, individual work); (3) individual factors (e.g., compensating strategies, planners, self-determination); (4) reading and study strategies (e.g., index cards/study guides, rehearsing, writing, visualizing, previewing); and (5) factors in academic challenges (e.g., focus, time management, social challenges, memory issues). Students preferred individual work and hands-on instruction to other methods of learning, with online classes being the least preferred. Most students in this study did not disclose their ADHD diagnosis to the faculty but did seek support services for accommodations. Students took responsibility for their learning and success, including navigating and utilizing the resources available at the school.

In Lux’s [28] study of eight students with ADHD and learning disabilities, through three rounds of interviews, themes emerged around the college student experience, including (1) constructing and reframing knowledge of one’s disability, (2) self-assessment through observation and comparison, (3) identifying allies and resources, and (4) moving towards increased learner autonomy. For participants diagnosed before college, the construction of their disability first came from other people and reflected collective attitudes, whereas those diagnosed in college co-constructed knowledge of their disability. Students’ conceptualizations of their disability and its role in their identity were fluid and shaped by interactions with their environments. Like many of the other studies mentioned above, these participants found resources and/or supportive individuals to be key to their college experience. Learners viewed obtaining greater autonomy—developed using self-regulation, response to external expectations, and metacognitive reflection—as their ultimate goal.

With a focus on international students with learning disabilities, Alabdulwahab’s [29] study used interviews of students, disability support staff, and international student advisors. Of the three students interviewed, one had ADHD and all three had a cultural/linguistic background that was Asian or Middle Eastern. The student with ADHD had not struggled academically prior to coming to the US, was unfamiliar with ADHD at the time of their diagnosis, and thought that perhaps their challenges stemmed from their language proficiency. Alabdulwahab found nine themes, including language proficiency, social challenges, factors impacting academic success, knowledge of available support, providing accommodations and support, disclosure, the identification of LD/ADHD, disability awareness, and self-advocacy. From the perspective of disability support staff, the unique needs of non-native English-speaking college students with LD/ADHD include additional language proficiency assistance, the identification of unique cultural challenges, and assistance in understanding and navigating resources, as well as the disclosure and accommodations processes. It can be challenging for international students with disabilities to have the proper documentation for disability registration or accommodations prior to college, and it varied widely how early these students first became aware of their disability. The college staff interviewed believed that international students with disabilities did not have strong self-advocacy skills, and their family support, disability acceptance, and willingness to disclose had significant impacts on students’ self-advocacy.

Bolourian et al. [30] interviewed students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) as well as students with ADHD. They identified nine themes related to the university experiences of these students. Overall, students reported significant social, emotional, and academic challenges in college. Among the participants with ADHD, the most frequently mentioned challenges were the disclosure of the diagnosis and self-awareness in the present. Participants with ADHD also reported faculty being unsupportive and/or dismissing ADHD as not a valid disability. Key differences between these two student groups were that students with ADHD rarely discussed negative peer interactions but did discuss medication use, whereas students with ASD did the opposite. The only statistically significant difference found in the college experiences of students with ADHD vs. students with ASD revolved around negative peer interactions.

Focusing on a very different part of the college experience—sexual and intimate partner violence in college women with mental health/behavior disabilities (including ADHD)—Bonomi et al. [31] conducted semi-structured interviews of 27 students (two with ADHD alone, three with ADHD and other disabilities) and found that sexual violence (SV) was pervasive among college women with these disabilities, in both one-time “hookups” and recurring long-term partnerships. The researchers found that chronic, disability-specific abuse (e.g., disability-specific name calling, putting down or calling a person undesirable because of their disability, blaming past SV experiences on disability) was common for participants (including those with ADHD) experiencing sexual violence in long-term relationships. The study found that negative mental health outcomes co-occurred with other adverse behavioral, physical, and academic outcomes.

Pirozzi [32] interviewed eight students registered with the Disability Resource Center at Northeastern University about their perceptions of their higher education experience, including how ADHD played a role. Early identification and diagnosis were important in developing a self-identity that included ADHD as an important factor in individual growth and academic success. For those with pre-college diagnoses, parental navigation played an important role in preparing for academic success (e.g., advocating for testing) and modeling how the student could later seek resources independently. Students with a strong external support system were more successful and had stronger senses of belonging, which in turn increased their self-confidence and ability to succeed. With regard to internal (psychological) resources, higher levels of self-autonomy and understanding were associated with increased self-regulation and self-advocacy. Students also experienced a heightened sense of internal motivation following consistent, positive reinforcement from faculty. When participants engaged with topics of interest and faculty kept an open dialogue, students had more intrinsic motivation and better managed their involvement.

Appendix A.1.3. Race

Within the literature on the college transitions of students with ADHD, we found three articles that focused on the experiences of particular racial groups. Poe [33] explored the lived experience of learning in eight African American college students with ADHD. Through the triangulation of open-ended interviews, demographics, and validity checks, the researchers found clustered textural themes around students’ relationships with themselves and others, bodily concerns, the structure of time, and causality. Regarding the relationship with oneself, Poe found that these African American students with ADHD tended to possess an acute level of self-awareness regarding their struggles with aspects like concentration, effort, and anxiety. Furthermore, they tended to have an understanding of their learning limitations and preferences. In terms of students’ relationships with others, there was a need for these students to reach out for help; however, simultaneously, students may experience feelings of embarrassment in doing so. In addition, there was a tendency for these African American students with ADHD to compare themselves to others without ADHD. Many students highlighted the important impact of medication on their thinking. Poe suggested that most students with ADHD need to work at a slower pace than others. Lastly, under the theme of causality, the researchers underscored that students with ADHD who desire success and have a positive perspective on their condition are more likely to have a positive learning experience.

Mills [34] built on Poe’s [33] work, similarly approaching the experiences of eight African American college students with ADHD through qualitative case studies. Mills’ findings suggest that students who understand how ADHD impacts their academic experiences are better prepared to overcome academic challenges. Mills found that, among this sample, hands-on activities, an interactive atmosphere, and instructive relationships helped the African American college students with ADHD to better learn in academic settings. Furthermore, Mills found that many students reported challenges with organization and study skills, as well as interacting with the academic environment.

Young [35] used a life history approach to conduct case studies on the psychosocial and cultural factors influencing the experiences of Chinese American college students with ADHD. Young used two in-depth interviews (the first focused on pre-college and diagnosis, the second on college experience and academics) and supplemental free association journaling. This group of students performed well in grades K-12 but encountered difficulties in college, when harder coursework with complex requirements and increased autonomy taxed their existing coping and self-regulated learning strategies. Students were also challenged to build new systems of support in college. Culturally, the familial support of Chinese American students with ADHD differed based on the parental understanding of ADHD and their acculturation into mainstream American culture. To illustrate, parents who identify with Eastern belief systems and values tend to be less willing to seek ADHD treatment for their children, attributing their behavior to characteristics such as laziness or a lack of motivation. Students in the sample shared how their parents’ reactions to their condition shaped their internal framework of ADHD and their identity.

Appendix A.1.4. Community College

Two papers focused specifically on community college students with ADHD. First, Coon [36] interviewed ten Iowa community college students with ADHD to understand the experiences and educational impacts of interactions with faculty and student support services. From two one-hour interviews, Coon found that the students in the sample had both positive and negative interactions with faculty and primarily positive interactions with student support services personnel. Students enjoyed working with personable and understanding faculty members, and student support services personnel helped the students to feel comfortable and good about themselves. Supportive and understanding interactions with both faculty and support staff were found to motivate students to achieve, and students reported a belief that they could achieve at higher rates with positive support. Students reported that faculty need regular ADHD and disability awareness training, tolerance of ADHD learning differences, and varied teaching styles to connect with students who have ADHD.

Second, Flowers [37] studied California community college students with ADHD. The students in this sample reported that the faculty and staff at their community college understood how to support those with ADHD and taught effectively using interactivity and group work. Students reported a smooth transition from high school to college due to institutional support. Students’ social capital came from family and community support, including housing and encouragement. Institutional agents helped students to navigate institutional resources. This sample found the Disability Services Center, counseling services, and reviews of their educational plans with an advisor to be key to their success.

Appendix A.2. Interventions

Nine articles in our literature review primarily focused on interventions to help students to cope with their ADHD symptomatology.

Appendix A.2.1. Coaching

Four of these articles investigated ADHD coaching. A dissertation by Reaser [38] followed a small group (n = 7) of postsecondary students (a mix of undergraduate and graduate) with ADHD as they participated in an 8-week coaching program. This particular program utilized a number of standardized rating scales, from which Reaser [38] was able to examine any changes from the baseline. The coach in this study provided students with a number of resources, including a daily planner and a to-do list log, and monitored students’ progress on a weekly basis, allotting rewards and consequences accordingly. Interestingly, the students in this study consistently reported that the rewards and consequences given by their coach were the least helpful components of the intervention, noting that they were not as motivating in reality as they were intended to be. While the students in this study varied in the achievement of their goals, all agreed that coaching was “worth the effort” and was just as effective, if not more effective, than other interventions for ADHD, including medication.

Parker et al. [39] interviewed seven students with ADHD who took part in a coaching program. This study employed the Student Self-Determination Scale (S-DSS) to track each student’s sense of autonomy across two time points. They found that coaching fostered a heightened sense of autonomy among the participants. Parker et al. also explored students’ motivations for participation in coaching. Many students wished to improve their academic performance and time management through coaching. Across all students, on-task behavior increased and stress decreased following coaching. Students also emphasized their appreciation of the personalization of the coaching process. The fact that each student worked with one of three different coaches suggests that the effects were not due to just one particularly talented coach.

Similar to Reaser [38], Prevatt et al. [40] followed students with ADHD (n = 23, a mix of undergraduate and graduate) through an 8-week coaching program. They found that most students who sought coaching held goals related to time management and academic achievement and responded best to weekly rewards and/or consequences. They found significant, positive relationships between students’ ratings of their coaches, their levels of motivation, their time management skills, and their success in the coaching program.

Kreider et al. [41] specifically studied problem-solving support by pairing undergraduate mentees with trained graduate student mentors and analyzing their reflections throughout the process. The researchers found that most mentees sought mentorship to strategize solutions for difficulties with their executive functioning, academics, and adult life skills, underscoring the importance of incorporating biopsychosocial approaches in the practice of coaching. They also posited that occupational therapists could play an important role in supporting undergraduate students with ADHD.

Appendix A.2.2. Strategies

Expanding beyond the specific intervention of coaching, Melara [42] examined a variety of factors that may affect the academic persistence of college students with ADHD. Melara found that family and peer support, medication, counseling, a sense of connection with faculty/staff, university-based resources, and overall satisfaction with academic and social experiences were all important facets in bolstering students’ academic success. These data were captured across two different universities via qualitative interviews.

Lastly, the Bartlett et al. study [43] also interviewed college students with ADHD about factors that mitigated their symptoms. Uniquely, instead of focusing on current-day strategies, this study prompted participants to reflect upon interventions that helped them to cope with their symptoms in childhood. Overwhelmingly, students described the positive impact of parents and teachers who showed an investment in their success through genuine caring and the teaching of targeted practices for focus.

Appendix A.2.3. Medication

We found three articles focused on medication for college students with ADHD. As noted in our Materials and Methods section, we excluded articles that were solely about medication misuse in college students, but we did include other articles with a medication focus.

In the earliest study, Davis-Berman and Pestello [44] interviewed 20 students and extracted five themes across their interviews, which included (1) the recruitment of the young, (2) freedom from/little personal stigma, (3) social issues surrounding stimulants, (4) the side effects of medication, and (5) the abuse of medication. College students with ADHD in the sample frequently spoke of having been diagnosed at a young age, as a result of disruptive and/or inattentive behavior in class. Interestingly, while many students denied harboring any personal stigma about their own ADHD diagnosis and/or the use of ADHD medication, they described having experienced social stigma surrounding the legitimacy of their diagnosis and/or medication use (particularly the association of their diagnosis with low intelligence levels). Davis-Berman and Pestello [44] also reported that sleep disturbances and weight loss were common side effects of ADHD medication among their sample. Finally, these researchers found that some college students with ADHD sold their medication during exam seasons for monetary gain, while others kept their prescriptions a secret to avoid any pressure to share their medication.

Similar to Davis-Berman and Pestello [44], Meaux et al. [45] recruited 15 college students with ADHD to partake in semi-structured interviews. From their study, Meaux et al. found three global themes surrounding the use of ADHD medication: (1) taking medicine in childhood, (2) side effects, and (3) abuse/misuse in college. Many participants reported feelings of embarrassment during childhood and adolescence when they had to go to the school nurse to take their ADHD medication during the school day. The discussion of side effects largely focused on the tradeoff between the positive and negative side effects that accompany ADHD medication. The negative side effects of ADHD medication often lead to college students not taking their medication on the weekends. In addition, Meaux et al. found that the abuse and misuse of ADHD medication among college students was profound.

Loe and Cuttino [46] conducted semi-structured interviews with 16 college students with ADHD and found two main themes: (1) authenticity of self while medicated and (2) academic performance while medicated. Regarding the first theme, a number of interviewees reported experiencing personality changes after taking ADHD medication. Many also reported feeling biologically different from people without ADHD, attributing much of their sense of self to the environment. In contrast to the findings of the two aforementioned studies, Loe and Cuttino found that many college students with ADHD in their sample blamed themselves for not being able to meet social expectations. Students also voiced doubts about the existence of ADHD before they were diagnosed themselves, as well as confusion over when to stop taking their ADHD medication.

Appendix A.3. Cognitive and Academic Functioning

We located five articles whose primary focus was the cognitive and/or academic functioning of college students with ADHD.

In the earliest of these studies, Judd [47] studied how three students with ADHD acquired the mathematical concept of a function, as an example of how students with ADHD learn mathematics more generally. The investigator periodically observed the students’ math classes to see how formal instruction was taking place and also interviewed the students during tutoring sessions that she conducted. Finally, Judd compared the performance of two students with ADHD to the performance of two students without ADHD on a particular math problem requiring the use of functions. From these varied sources of evidence, Judd concluded that the students with ADHD had more difficulty with abstract representations of functions (e.g., in equation form), needing to work with visual representations (either graphs or tables).

In contrast, Lee et al. [48] used a mixed-methods design in which 31 college students with ADHD were randomly assigned across four conditions while taking an exam with a passage from an introductory psychology textbook, followed by 11 multiple-choice questions. The four conditions varied along two dimensions: whether students took the test on a computer or in paper-and-pencil form and whether students had a shorter (11 min) or a longer (16.5 min) amount of time in which to answer the test questions. Quantitative analyses found that students in the computer conditions outperformed those in the paper-and-pencil conditions and that there was no significant difference across the different time limits. An open-ended question set asked students about their testing experience and preferences. Students mentioned that extended time and a quiet environment were the accommodations that they most needed, and most students reported preferring a paper-and-pencil test, most often citing the ease of writing on the test form. Finally, most students indicated that if they were to take a computer-based test, they would prefer to have only a single question on the screen at a time. As Lee et al. noted, students’ subjective preferences did not seem to align with the objective performance data on performance, although the latter were based on only a single, contrived test.

Hood [49] studied how over 20 students (a mix of undergraduate and graduate) with ADHD coped with traumatic events. Five of the students were selected for in-depth interviews. Some of the items related particularly to cognitive and academic functioning. Over half (62%) of the participants felt that they avoided challenging tasks due to the difficulties of creating structure for learning. Hood noted that most participants nonetheless reported having healthy coping skills and performing well in classes and/or life.

Nash-Luckenbach [50] used a phenomenological approach, interviewing 10 college students with ADHD about their preferred approaches to learning, studying, and being evaluated, as well as how they felt that ADHD had affected their learning. Using Kolb’s style typology, Nash-Luckenbach found that almost all of the students either preferred an “assimilation” style to learning and studying (i.e., emphasizing watching and thinking) or an “accommodation” style (i.e., emphasizing doing and feeling). Other styles, which emphasized watching and feeling or doing and thinking, were rarely, if ever, endorsed. Tests were the most commonly endorsed preference for course assessment methods, and students expressed a desire for frequent tests within a course, as a method of keeping them accountable for studying continuously. Finally, students reported believing that they needed to work harder than their peers (without ADHD) to achieve the same or similar outcomes.

In the most recently published study within this category, Rodriguez [51] conducted interviews with 14 community college students with ADHD, focusing specifically on students’ experiences with scheduling and keeping track of time, with implications for academic functioning. Students reported checking the time very frequently due to the fear that otherwise they would “lose” time and not complete the required tasks at school. They perceived their experience of time to be different from that of their (non-ADHD) peers but had difficulty in describing how. Despite their best efforts, they encountered problems with time. This was in part because, although they could create schedules, keeping to the schedule was another matter, particularly when this required mental flexibility due to scheduling changes. Therefore, planning ahead did not seem to be helpful. Many students also reported extreme motivational and even emotional problems in adhering to a schedule when the scheduled activities included ones that were not preferred. (At times, this adherence problem also extended to adhering to the use of memory strategies.) Students generally reported not using formal disability accommodations much, if at all (including accommodations for these time-related challenges), not because of any logistical difficulty in obtaining accommodations but because the students were doubtful that the accommodations were either needed or helpful.

Appendix A.4. Self-Functioning

We encountered eight articles focused on the self-functioning of college students with ADHD.

To explore the dynamics of achievement motivation in individuals with ADHD, Fox [52] conducted interviews with 10 college students with ADHD diagnoses and completed a focus group with an additional five students. The research questions were framed in terms of three core motives posited by self-determination theory: (1) autonomy, (2) competence, and (3) relatedness. Common themes in the participants’ responses to the questions included (a) doubting one’s abilities, (b) questioning the decision to be/stay in college, (c) finding the environment that works best for studying/working, (d) the perceived importance of achieving good grades, (e) struggling to stay motivated to complete assignments, (f) the beneficial effects of positive peer relationships on the motivation to learn, and (g) a preference for being alone due to having ADHD. Each of these seven themes was endorsed by at least 10 of the 15 participants and sometimes by all 15 of them.

Kreider et al. [53] examined the products of disability advocacy projects created by a sample of 52 undergraduates with learning and/or attention disorders who were majoring in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields. The projects included physical artwork, videos, and text-based projects. Most often, the projects represented the students’ own experiences, either in a neutral (non-emotional) or a negative evaluative way. Less often, the students represented disability in a positive or ambivalent (“pros and cons”) way, presented information about disability without making a personal connection, or focused on the place of disability in society. The researchers did not differentiate between ADHD and other learning-related disorders in terms of the findings.

Waite and Tran [54] conducted two lengthy interviews with 27 postsecondary students with ADHD diagnoses. The focus of the interviews was “explanatory frameworks”—the mental models that participants used to make sense of their ADHD. Male participants tended to attribute their ADHD solely to biological factors, whereas female participants were more likely to also cite environmental causes related to parenting, dietary chemicals, and trauma. Participants tended to emphasize the impairing “chaos” that their ADHD symptoms led to in many domains of life, with a rare exception being that many participants attributed creative abilities to their ADHD. Participants also repeatedly emphasized the importance of their disorder being recognized by professionals and later accepted by themselves, relieving earlier confusion and frustration. Finally, when asked about treatment, participants tended to focus on medication and discussed their ambivalence over medication use, due to side effects, concerns about addiction, and a less tangible sense of not being oneself when on medication.

Driggers [55] used a combination of interviews, written responses, and an analysis of artifacts (academic records, creative works, etc.) to study the phenomenon of psychological resilience in 10 college students with ADHD diagnoses. The research questions centered around how students with ADHD coped with challenges and managed to be successful in spite of their ADHD. Driggers classified the data into two broad classes of strategies for success: self-regulation and proactive choices. All 10 students discussed self-regulation strategies, and, as Driggers noted, this was somewhat surprising, since the ability to use these strategies might seem to undermine the presence of ADHD symptoms in the first place. These strategies ranged from exerting extra effort to “power through” activities to rewarding oneself for task completion and to acquiring self-awareness. All 10 students also discussed making proactive choices, such as choosing to sit in the front row of a classroom (to make it easier to pay attention), choosing to take medication, and choosing to access college resources for students.

Roper [56] examined self-advocacy in college students with learning and/or attention disorders through six case studies of such students. The students were taking part in a self-advocacy intervention, and Roper used data from interviews, questionnaires, measures of knowledge, and role-playing exercises administered before, during, and after the intervention to learn more about self-advocacy in this sample. Four themes were found in the data. First, participants reported extensive parental support for academics (and parental advocacy at school) during their K-12 education, but they faced considerable challenges in college since this parental support was not available anymore, at least not to the same degree. Second, participants described a developmental process during which they came to understand their unique disability conditions and related functional impairments, and, as this understanding grew, they were better able to advocate for themselves. Third, participants reported positive experiences with self-advocacy, feeling comfortable disclosing their disabilities, and professors responding positively to requests for accommodations. Finally, participants reported benefiting from the self-advocacy intervention, particularly benefiting from learning more about the laws that apply to disability discrimination.

Webb [57] interviewed 11 postsecondary students with ADHD, with a focus on self-efficacy and specifically academic self-efficacy: the degree to which students were confident in their ability to reach various academic goals. Most participants reported feeling happy or relieved when they were diagnosed with ADHD, often because the diagnosis helped to explain difficulties at school. The vast majority of participants expressed confidence in their ability to solve complex problems, but most said that they would need “plenty of time” to do so. Several participants did express that it was “challenging to persevere and accomplish goals”, particularly long-term goals. However, participants attributed their generally high self-efficacy to parent/family influences, others having high confidence in them, and prior mastery experiences. With regard to academic self-efficacy in particular, most participants described their academic history as uneven, containing significant success and failure. Grades and teachers were viewed as important influences on academic self-efficacy in this sample. Finally, most students did not take advantage of academic resources at school but used medication and believed it to be important to their academic success; Webb inferred that medication may increase academic self-efficacy.

Tse [58] conducted interviews with eight college students with ADHD, as part of a larger mixed-methods study. The focus of the study was students’ social skills and self-esteem, and the 10 “guiding questions” for the semi-structured interviews generally addressed these topics. With regard to social skills, participants reported relatively low levels of social activity and attributed this to their ADHD, stating that it was difficult for their (non-ADHD) peers to understand the nature of their disorder and that ADHD also affected their ability to schedule and have time for activities. With regard to self-esteem, participants mentioned not feeling as “smart” or as “good” as their non-ADHD classmates, needing to work harder than their peers, and experiencing a depressed mood (five of the eight students had clinical diagnoses of depression). Tse argued that low self-esteem was connected with the students’ reports of using alcohol to address negative emotions as well.

Haig [59] used a mixed-methods design to investigate the role of self-regulation strategies in the academic functioning of college students with ADHD. He interviewed 48 college students, 24 with ADHD and 24 without the diagnosis. The most common self-regulation strategies reported by students with ADHD were goal setting and perseverance. Students set achievable, short-term goals (e.g., achieving a C in a course) to maximize their chances of success and persisted in goal pursuit even when their natural motivation flagged. Fewer students with ADHD—but still a majority—endorsed each of four other self-regulation strategies: keeping notes/records, explicitly monitoring their performance in detail, planning ahead, and seeking information or assistance from their professors.

References

- Chung, W.; Jiang, S.F.; Paksarian, D.; Nikolaidis, A.; Castellanos, F.X.; Merikangas, K.R.; Milham, M.P. Trends in the prevalence and incidence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among adults and children of different racial and ethnic groups. JAMA Netw. Open 2009, 2, e1914344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digest of Education Statistics. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d21/tables/dt21_311.10.asp (accessed on 4 April 2024).

- Characteristics and Outcomes of Undergraduates with Disabilities. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2018/2018432.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2024).

- DuPaul, G.J.; Gormley, M.J.; Anastopoulos, A.D.; Weyandt, L.L.; Labban, J.; Sass, A.J.; Postler, K.B. Academic trajectories of college students with and without ADHD: Predictors of four-year outcomes. J. Clin. Child. Adolesc. Psychol. 2021, 50, 828–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Rourke, S.R.; Bray, A.C.; Anastopoulos, A.D. Anxiety symptoms and disorders in college students with ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 2020, 24, 1764–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastopoulos, A.D.; Langberg, J.M.; Eddy, L.D.; Silvia, P.J.; Labban, J.D. A randomized controlled trial examining CBT for college students with ADHD. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 89, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, A.R.; Weyandt, L.L.; Anastopoulos, A.D.; DuPaul, G.J.; Shepard, E. Outcomes and predictors of stimulant misuse in college students with and without ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 2022, 26, 779–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APA Dictionary of Psychology. Available online: https://dictionary.apa.org/qualitative-research (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Sabnis, S.V.; Newman, D.S.; Whitford, D.; Mossing, K. Publication and characteristics of qualitative research in School Psychology journals between 2006 and 2021. Sch. Psychol. 2023, 38, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, C.J.; Hardman, M.L.; Hosp, J.L. Designing and Conducting Research in Education; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schonfeld, I.S.; Mazzola, J.J. Strengths limitations of qualitative approaches to research in occupational health psychology. In Research Methods in Occupational Health Psychology: State of the Art in Measurement, Design, and Data Analysis; Tetrick, L., Sinclair, R., Wang, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 268–289. [Google Scholar]

- Camic, P.M. Qualitative Inquiry in Psychological Research, Expanding Perspectives in Methodology and Design, 2nd ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Leko, M.M.; Cook, B.G.; Cook, L. Qualitative methods in special education research. Learn. Disabil. Res. Pract. 2021, 36, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madaus, J.W.; Gelbar, N.; Dukes, L.L., III; Lalor, A.R.; Lombardi, A.; Kowitt, J.; Faggella-Luby, M.N. Literature on postsecondary disability services: A call for research guidelines. J. Divers. High. Educ. 2018, 11, 133ff. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaus, J.W.; Dukes, L.L., III; Lalor, A.R.; Aquino, K.; Faggella-Luby, M.; Newman, L.A.; Wessel, R.D. Research Guidelines for Higher Education and Disability. J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 2020, 33, 319–338. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowski, L.J.; Lovett, B.J.; Codding, R.S.; Gordon, M. Symptoms of ADHD and academic concerns in college students with and without ADHD diagnoses. J. Atten. Disord. 2008, 12, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suhr, J.A.; Johnson, E.E. First do no harm: Ethical issues in pathologizing normal variations in behavior and functioning. Psychol. Inj. Law 2022, 15, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.M.; Lovett, B.J. Assessing ADHD in college students: Integrating multiple evidence sources with symptom and performance validity data. Psychol. Assess. 2019, 31, 793–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascon, A.; Gamache, D.; St-Laurent, D.; Stipanicic, A. Do we over-diagnose ADHD in North America? A critical review and clinical recommendations. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 78, 2363–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meaux, J.B.; Green, A.; Broussard, L. ADHD in the college student: A block in the road. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2009, 16, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, K. The College Transition Experience of Students with ADHD. Ph.D. Thesis, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- McCall, Z.A. The transition experiences, activities, and supports of four college students with disabilities. Career Dev. 2015, 38, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denson, T.C. The Transitioning Experiences of First-Year Students with ADHD into College: A Case Study. Ph.D. Thesis, Northcentral University, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, A.E. Perspectives from College Students with ADHD: A Qualitative Examination of Parental Support and the Parent-Child Relationship in the Transition to College. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mullins, L.; Preyde, M. The lived experience of students with an invisible disability at a Canadian university. Disabil. Soc. 2013, 28, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, V. University Students Diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Hermeneutical Phenomenological Study of Challenges and Successes. Ph.D. Thesis, Liberty University, Richmond, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lux, S.J. The Lived Experiences of College Students with a Learning Disability and/or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Ph.D. Thesis, Iowa State University, Des Moines, IA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Alabdulwahab, R. Postsecondary Education for International Undergraduate Students with Learning Disabilities in the United States. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Northern Colorado, Greely, CO, USA, 20 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bolourian, Y.; Zeedyk, S.M.; Blacher, J. Autism and the university experience: Narratives from students with neurodevelopmental disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 48, 3330–3343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonomi, A.; Nichols, E.; Kammes, R.; Green, T. Sexual violence and intimate partner violence in college women with a mental health and/or behavior disability. J. Women’s Health 2018, 27, 359–368. [Google Scholar]

- Pirozzi, M. The Perception of the College Experience for Students with ADHD. In Proceedings of the IHSES 2022—International Conference on Humanities, Social and Education Sciences, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 21–24 April 2022; Noroozi, O., Sahin, I., Eds.; ISTES Organization: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2022; pp. 18–32. [Google Scholar]

- Poe, M.A. A Phenomenological Study of the Educational Learning Experiences of African American College Students with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Ph.D. Thesis, Capella University, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, M.C. The Learning Experiences in a College Environment for African American Students Diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): A Qualitative Case Study. Ph.D. Thesis, Capella University, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Young, E.W.D.M. Understanding the Psycho-Social and Cultural Factors that Influence the Experience of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Chinese American college students: A Systems Approach. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Coon, H.L. Community College Students with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (AD/HD): A Student Perspective. Ph.D. Thesis, Capella University, Minneapolis, MN, USA.

- Flowers, L. Navigating and Accessing Higher Education: The Experiences of Community College Students with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Reaser, A.L. ADHD Coaching and College Students. Ph.D. Thesis, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, D.R.; Boutelle, K. Executive function coaching for college students with learning disabilities and ADHD: A new approach for fostering self-determination. Learn. Disabil. Res. Pract. 2009, 24, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevatt, F.; Smith, S.M.; Diers, S.; Marshall, D.; Coleman, J.; Valler, E.; Miller, N. ADHD coaching with college students: Exploring the processes involved in motivation and goal completion. J. Coll. Stud. Psychother. 2017, 31, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreider, C.M.; Medina, S.; Koedam, H.M. (Dis)ability-informed mentors support occupational performance for college students with learning disabilities and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders through problem-solving and a focus on strengths. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2021, 84, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melara, C.A. Factors Influencing the Academic Persistence of College Students with ADHD. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, R.; Rowe, T.S.; Shattell, M.M. Perspectives of college students on their childhood ADHD. MCN Am. J. Matern. Child Nurs. 2010, 35, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis-Berman, J.L.; Pestello, F.G. Medicating for ADD/ADHD: Personal and social issues. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2010, 8, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meaux, J.B.; Hester, C.; Smith, B.; Shoptaw, A. Stimulant medications: A trade-off? J. Spec. Ped. Nurs. 2006, 11, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loe, M.; Cuttino, L. Grappling with the medicated self: The case of ADHD college students. Symb. Interact. 2008, 31, 303–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judd, A.D. Function, Visualization, and Mathematical Thinking for College Students with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Northern Colorado, Denver, CO, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.S.; Osborne, R.E.; Carpenter, D.N. Testing accommodations for university students with AD/HD: Computerized vs. paper-pencil/regular vs. extended time. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2010, 42, 443–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, M.R. A Phenomenological Study: How College Students with ADHD are Affected by Fragmentation and Dissassociation. Ph.D. Thesis, Concordia University, Portland, OR, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nash-Luckenbach, D. Exploring Learning Style Preferences of College Age Students with Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder (ADHD). Ph.D. Thesis, Seton Hall University, South Orange, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, E. Time, Schedules, and the College Student with ADHD. Ph.D. Thesis, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, K.A., Jr. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Perceived Impact on College Students’ Motivation to Learn. Ph.D. Thesis, Grand Canyon University, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kreider, C.M.; Luna, C.; Lan, M.F.; Wu, C.T. Disability advocacy messaging and conceptual links to underlying disability identity development among college students with learning disabilities and attention disorders. Disabil. Health J. 2020, 13, 100827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waite, R.; Tran, M. Explanatory models and help-seeking behavior for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder among a cohort of postsecondary students. Arch. Psychiat. Nurs. 2010, 24, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driggers, J.A.G. Resiliency in Undergraduate College Students Diagnosed with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Ph.D. Thesis, Walden University, Saint Paul, MN, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Roper, L.G. Self-Advocacy Among College Students with Learning Disabilities and/or Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorders. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, K. Self-Efficacy in College Students with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts School of Professional Psychology, Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tse, M. Social Skills and Self-Esteem of College Students with ADHD. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Haig, J.D. The Role of Self-Regulation Strategies on Two- and Four-Year College Students with ADHD. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).