Navigating Higher Education Challenges: A Review of Strategies among Students with Disabilities in Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

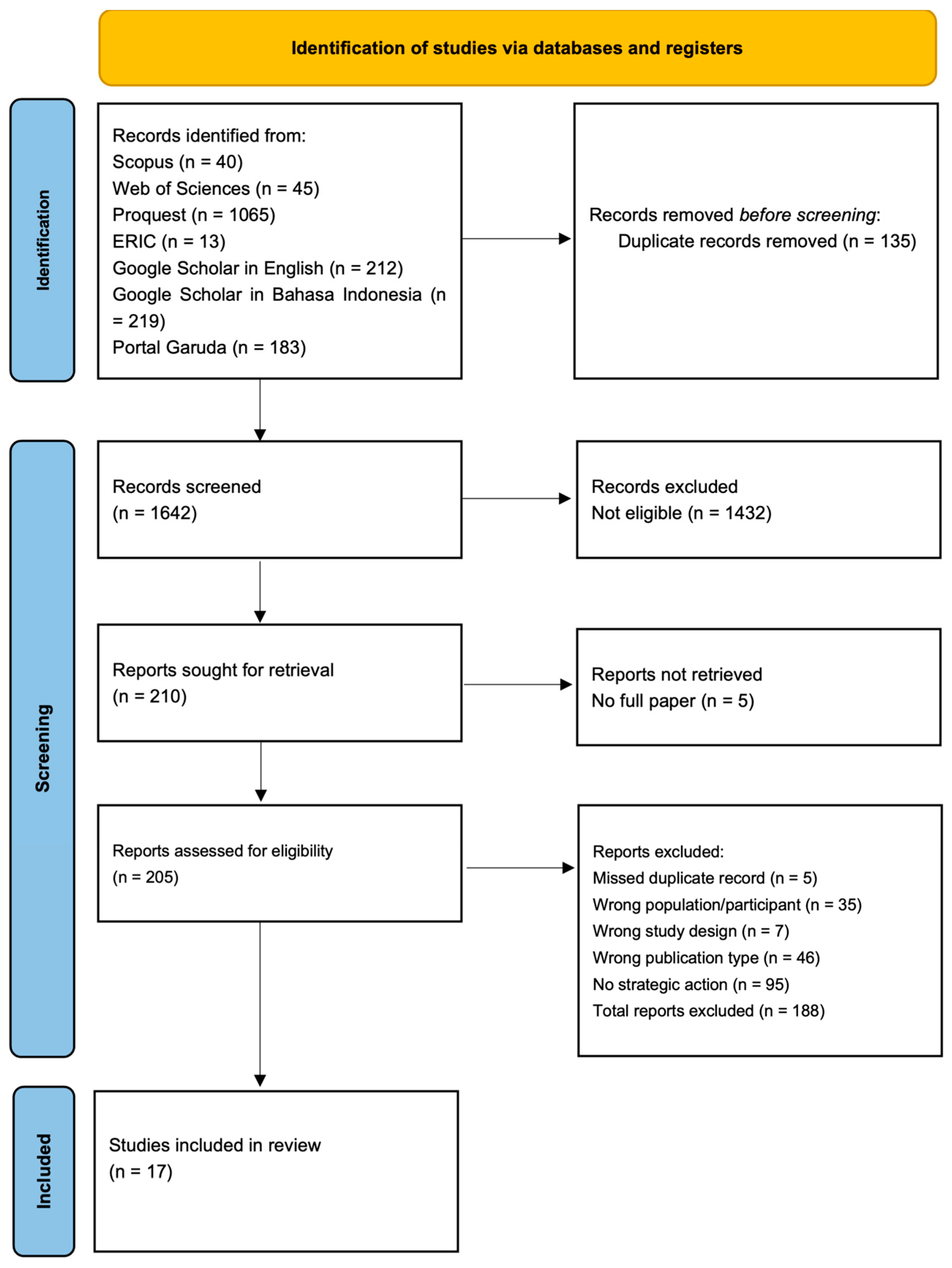

2.1. Identifying the Relevant Literature

2.2. Selecting the Literature

2.3. Charting the Data

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristic

3.2. Strategies for Navigating Challenges

3.2.1. Adaptation

3.2.2. Assistive Technology Optimization

3.2.3. Requesting Support

3.2.4. Building Relationship

3.2.5. Passive Action

4. Discussion

4.1. Adaptation

4.2. Assistive Technology Optimization

4.3. Requesting Support

4.4. Building Relationship

4.5. Passive Action

5. Recommendation for Practices and Policies

5.1. Recommendation 1: Foster Disability-Friendly Campus

5.2. Recommendation 2: Skill Development for SwD

5.3. Recommendation 3: Strengthen Policies Promoting Disability Inclusion in HE

6. Limitation

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brennan, J.; Durazzi, N.; Tanguy, S. Things We Know and Don’t Know about the Wider Benefits of Higher Education: A Review of the Recent Literature. In Department for Business Innovation and Skills; BIS Research Paper URN BIS/13/1244; LSE Consulting: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval-Lucero, E. Serving the Developmental and Learning Needs of the 21st Century Diverse College Student Population: A Review of Literature. J. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 2014, 4, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, A. Resilience in People with Physical Disabilities; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriña, A.; Biagiotti, G. Academic Success Factors in University Students with Disabilities: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2021, 37, 729–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, G.L.; Duke, J.M.; Fujita, M.; Sutton, J. “It’s a Constant Fight”: Experiences of College Students with Disabilities. J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 2019, 32, 247–261. [Google Scholar]

- Moriña, A. Inclusive Education in Higher Education: Challenges and Opportunities. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2017, 32, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yssel, N.; Pak, N.; Beilke, J. A Door Must Be Opened: Perceptions of Students with Disabilities in Higher Education. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2016, 63, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lintangsari, A.P.; Emaliana, I. Inclusive Education Services for the Blind: Values, Roles, and Challenges of University EFL Teachers. Int. J. Eval. Res. Educ. 2020, 9, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maftuhin, A.; Aminah, S. Universitas Inklusif: Kisah Sukses atau Gagal? INKLUSI J. Disabil. Stud. 2020, 7, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiyaningsih. Pertuni Tingkatkan Akses Penyandang Tunanetra ke Perguruan Tinggi. Republika. Available online: https://www.republika.co.id/berita/nasional/umum/17/03/18/omzb0m384-pertuni-tingkatkan-akses-penyandang-tunanetra-ke-perguruan-tinggi (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Pratiwi, A.; Lintangsari, A.P.; Rizky, U.F.; Rahajeng, U.W. Disabilitas dan Pendidikan Inklusif di Perguruan Tinggi; Universitas Brawijaya Press: Malang, Indonesia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nasir, M.N.A.; Efendi, A. Thematic Analysis on the Rights of Disabled People to Higher Education. J. Educ. Soc. Sci. 2019, 12, 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Afrianty, D. Disability Rights and Inclusive Education in Islamic Tertiary Education. In Islam, Education and Radicalism in Indonesia; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 306–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amnesti, S.K.W.; Jundiani, J.; Zulaichah, S.; Mohd Noh, M.S.; Fitriyah, L. Higher Education with Disabilities Policy: Ensuring Equality Inclusive Education in Indonesia, Singapore and United States. J. Hum. Rights Cult. Leg. Syst. 2023, 3, 412–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feriani, E. Interaksi Sosial Dosen dengan Mahasiswa Difabel di Perguruan Tinggi Inklusif. INKLUSI J. Disabil. Stud. 2017, 4, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Muhibbin, M.A.; Hendriani, W. Tantangan dan Strategi Pendidikan Inklusi di Perguruan Tinggi Di Indonesia: Literature Review. J. Pendidik. Inklusi 2021, 4, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juwantara, R.A. Pemenuhan Hak Difabel di UIN Sunan Kalijaga dan Universitas Atma Jaya Yogyakarta. INKLUSI J. Disabil. Stud. 2020, 7, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, M.; Rachman, A.; Mirnawati, M. Problematik Pembelajaran Mahasiswa Berkebutuhan Khusus pada Perguruan Tinggi Inklusif. Vidya Karya 2021, 35, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunardi; Sugini; Prakosha, D.; Martika, T. The Development of an Inclusion Metric for Indonesia Higher Education Institutions. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Learning Innovation and Quality Education, Surakarta, Indonesia, 5 September 2020; ACM: Surakarta, Indonesia, 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Predicting and Changing Behavior; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, C.; dos Santos, K.B.; Pap, R. Practical Guidance for Knowledge Synthesis: Scoping Review Methods. Asian Nurs. Res. 2019, 13, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Collins, A.M.; Coughlin, D.; Kirk, S. The Role of Google Scholar in Evidence Reviews and Its Applicability to Grey Literature Searching. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the Thematic Synthesis of Qualitative Research in Systematic Reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlas.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH. Atlas.ti Mac (version 23.2.1). 2023.

- Matin, B.K.; Williamson, H.J.; Karyani, A.K.; Rezaei, S.; Soofi, M.; Soltani, S. Barriers in Access to Healthcare for Women with Disabilities: A Systematic Review in Qualitative Studies. BMC Womens Health 2021, 21, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, E.; Hollmann, E.; Le Roux, C.W.; Bustillo, M.; Nadglowski, J.; McGillicuddy, D. The Lived Experience of Patients with Obesity: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Synthesis. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The PLoS Medicine. Qualitative Research: Understanding Patients’ Needs and Experiences. PLoS Med. 2007, 4, e258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destiyanti, I.C.; Halawati, F. Optimasalisasi Penggunaan TPACK: Praktik TPACK dalam Konteks Mahasiswa Disabilitas. J. Pendidik. Konseling 2022, 4, 3979–3986. [Google Scholar]

- Fikriyyah, W.R.; Fitria, M. Adversity Quotient Mahasiswa Tunanetra. J. Psikol. Tabularasa 2015, 10, 115–128. [Google Scholar]

- Grafiyana, G.A. Dinamika Resiliensi pada Mahasiswa Difabel Universitas Gadjah Mada. Psycho Idea 2018, 16, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handayani, I.P.; Achadi, M.Y.; Khairi, A.M. Pola Belajar Mahasiswa Disabilitas Netra pada Masa Pandemi COVID-19 Di UIN Raden Mas Said Surakarta. Masal. J. Pendidik. Sains 2022, 2, 406–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardini, F.; Tarigan, S.J.B.; Trang, V.T.T. Barriers and Coping Strategies of Students with Disability during Inclusive Learning in Higher Education. J. Inov. Teknol. Pembelajaran Kaji. Ris. Dalam Teknol. Pembelajaran 2022, 9, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusmawati, A.; Rahman, I.; Fauziyah, A.; Aulia, C. Konseling Kelompok Rekan Sebaya bagi Disabilitas Netra di Lingkungan Universitas Muhammadiyah Jakarta. J. Pendidik. Konseling 2023, 5, 3733–3740. [Google Scholar]

- Larasati, R.P.; Noorrizki, R.D. Resiliensi pada Mahasiswa Penyandang Disabilitas di Universitas Negeri Malang. J. Penelit. Kualitatif Ilmu Perilaku 2022, 3, 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Maftuhin, A. Hambatan Inklusi Mahasiswa Difabel dalam Kuliah Kerja Nyata (KKN) UIN Sunan Kalijaga Yogyakarta. Edukasia J. Penelit. Pendidik. Islam 2018, 12, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, D. Penyelenggaraan Pendidikan Tinggi Bagi Penyandang Disabilitas Di Universitas Brawijaya. J. Herit. Archaeol. Manag. 2020, 11, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujahid, A. Psychological Well-Being pada Mahasiswa Muslim Penyandang Disabilitas Netra. Acad. J. Multidiscip. Stud. 2020, 4, 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahma, U.; Faizah, F.; Perwiradara, Y.; Ikawikanti, A.; Mayasari, B.M.; Rinanda, T.D. Analisa School Wellbeing pada Mahasiswa Disabilitas Tunadaksa, Tuli dan Tunanetra di Perguruan Tinggi Inklusi. Psikovidya 2020, 24, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnasari, D.E. Strategi Coping Mahasiswa Difabel dalam Menyelesaikan Skripsi di Masa Pandemi COVID-19. INKLUSI J. Disabil. Stud. 2021, 8, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahta, R.; Hasanah, N.; Pratiwi, A. Regulasi Emosi Mahasiswa Penyandang Tunarungu dalam Relasi dengan Kawan Sebaya. Indones. J. Disabil. Stud. 2015, 2, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ro’fah, R.; Hanjarwati, A.; Suprihatiningrum, J. Is Online Learning Accessible during COVID-19 Pandemic? Voices and Experiences of UIN Sunan Kalijaga Students with Diisabilities. Nadwa J. Pendidik. Islam 2020, 14, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosydi, R.; Dewi, D.S.E. Penyesuaian Diri pada Mahasiswa Disabilitas. PSIMPHONI 2020, 1, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, Q.Y.; Arifin, A.Z.; Sanjaya, R.; Nugraha, W.; Lessy, Z. Implementasi Kebijakan Kesejahteraan Sosial pada Adaptasi Sosial Mahasiswa Difabel dalam Proses Pembelajaran. JSHP J. Sos. Hum. Dan Pendidik. 2022, 6, 158–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudarwati, E.; Widiati, U.; Ubaidillah, M.F.; Prasetyoningsih, L.; Sulistiyo, U. A Narrative Inquiry into Identity Construction and Classroom Participation of an EFL Student with a Physical Disability: Evidence from Indonesia. Qual. Rep. 2022, 27, 1534–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witham, B.; Brewer, G. “Giving the People Who Use the Service a Voice”: Student Experiences of University Disability Services. Disabilities 2023, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, S.; Cagliostro, E.; Carafa, G. A Systematic Review of Barriers and Facilitators of Disability Disclosure and Accommodations for Youth in Post-Secondary Education. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2018, 65, 526–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdiana, A.; Post, M.W.M.; Bültmann, U.; Van Der Klink, J.J.L. Barriers and Facilitators for Work and Social Participation among Individuals with Spinal Cord Injury in Indonesia. Spinal Cord 2021, 59, 1079–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes, S.; Southgate, E.; Scevak, J.; Buchanan, R. University Student Perspectives on Institutional Non-Disclosure of Disability and Learning Challenges: Reasons for Staying Invisible. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2019, 23, 639–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. The Right to Higher Education a Social Justice Perspective; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kimball, E.W.; Moore, A.; Vaccaro, A.; Troiano, P.F.; Newman, B.M. College Students with Disabilities Redefine Activism: Self-Advocacy, Storytelling, and Collective Action. J. Divers. High. Educ. 2016, 9, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrianty, D.; Thohari, S.; Rahajeng, U.W.; Firmanda, T.H.; Mahalli, M. Perguruan Tinggi dan Praktik Akomodasi Layak Bagi Mahasiswa Penyandang Disabilitas di Indonesia di Masa Pandemi COVID-19; Australia-Indonesia Disability Research and Advocacy Network: Boston, MA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://aidran.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/perguruan-tinggi-dan-praktik-akomodasi-layak-bagi-mahasiswa-penyandang-disabilitas-di-indonesia-di-masa-pandemi-covid-19.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Layton, N.; Mont, D.; Puli, L.; Calvo, I.; Shae, K.; Tebbutt, E.; Hill, K.D.; Callaway, L.; Hiscock, D.; Manlapaz, A.; et al. Access to Assistive Technology during the COVID-19 Global Pandemic: Voices of Users and Families. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.H.; Tebbutt, E. The Informal Economy as a Provider of Assistive Technology: Lessons from Indonesia and Sierra Leone. Health Promot. Int. 2023, 38, daac005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendarwan, H.; Syaripuddin, M.; Sidik, H.; Prastama, E.; Kusumo Projo, N.W.; Nasrudin; Damanik, J.; Putri, I.; Indriasih, E.; Amannullah, G.; et al. Situation of Assistive Technology Provision in Indonesia. In Proceedings of the ICCHP-AAATE 2022 Joint International Conference on Digital Inclusio, Assistive Technology & Accessibility, Lecco, Italy, 11–15 July 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andra, M.B.; Usugawa, T. Automatic Transcription and Captioning System for Bahasa Indonesia in Multi-Speaker Environment. In Proceedings of the 2020 5th International Conference on Intelligent Informatics and Biomedical Sciences (ICIIBMS), Okinawa, Japan, 18–20 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- McNicholl, A.; Desmond, D.; Gallagher, P. Assistive Technologies, Educational Engagement and Psychosocial Outcomes among Students with Disabilities in Higher Education. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2023, 18, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, G.; Urwin, E.; Witham, B. Disabled Student Experiences of Higher Education. Disabil. Soc. 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahajeng, U.W.; Widyarini, I.; Ilhamuddin, I. Kekuatan Karakter Relawan Muda bagi Penyandang Disablilitas. INKLUSI J. Disabil. Stud. 2020, 7, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anctil, T.M.; Ishikawa, M.E.; Tao Scott, A. Academic Identity Development through Self-Determination: Successful College Students with Learning Disabilities. Career Dev. Except. Individ. 2008, 31, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, M.A.; Reiter, E.M.; Cordero, J.J.; Stanton, J.D. Inside and out: Factors That Support and Hinder the Self-Advocacy of Undergraduates with ADHD and/or Specific Learning Disabilities in STEM. CBE—Life Sci. Educ. 2021, 20, ar17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Test, D.W.; Fowler, C.H.; Wood, W.M.; Brewer, D.M.; Eddy, S. A Conceptual Framework of Self-Advocacy for Students with Disabilities. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2005, 26, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, S.; Cagliostro, E.; Carafa, G. A Systematic Review of Workplace Disclosure and Accommodation Requests among Youth and Young Adults with Disabilities. Disabil. Rehabil. 2018, 40, 2971–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnard-Brak, L.; Lectenberger, D.; Lan, W. Accommodation Strategies of College Students with Disabilities. Qual. Rep. 2014, 15, 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaks, Z. Changing the Medical Model of Disability to the Normalization Model of Disability: Clarifying the Past to Create a New Future Direction. Disabil. Soc. 2023, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfner, C.; Ott, C.; Upshaw, K.; Stowe, A.; Schwiebert, L.; Lanzi, R.G. Coping Strategies and Help-Seeking Behaviors of College Students and Postdoctoral Fellows with Disabilities or Pre-Existing Conditions during COVID-19. Disabilities 2023, 3, 62–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Language | Search Term | Database |

|---|---|---|

| English | (“college student” OR “university student” OR “postsecondary education” OR “college admission” OR “higher education” OR “student affairs” OR “student services” OR “student personnel”) AND (disabilit* OR “hearing impair*” OR deaf OR disabled OR handicap OR adhd OR add OR dyslex* OR blind OR disabilities OR accommodation OR “mental illness” OR “mobility impairment” OR “visual impair*”) AND indonesia | Scopus, Web of science, Proquest, ERIC, Google Scholar |

| Bahasa Indonesia | mahasiswa AND (disabilitas OR difabel OR difable OR difabilitas) | Google Scholar, Portal Garuda |

| No | Author and Year Publication | Public/Private HE | Participant | Strategies Theme |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Destiyanti & Halawati (2022) [30] | NA | N = 3. Intellectual (1), Blind (2); Sex: NA; Age: NA | b,c |

| 2 | Fikriyyah & Fitria (2015) [31] | Public | N = 3. All Blind; Sex: NA; Age: NA | a,b,c,e |

| 3 | Grafiyana (2018) [32] | Public | N = 2. All Deaf; Sex: NA; Age: NA | d |

| 4 | Handayani et al (2022) [33] | Public | N = 2. All Blind; Sex: NA; Age: NA | b,c,d |

| 5 | Hardini et al. (2022) [34] | Private | N = 6. Blind (5), Multiple (1); Sex: Male (5), Female (1); Age: M = 22.5 | a,b,c,d,e |

| 6 | Kusmawati et al. (2023) [35] | Private | N = 6; All Blind; Sex: NA; Age: NA | b,c |

| 7 | Larasati & Noorrizki (2022) [36] | Public | N = 2; Blind (2), Physical (1); Sex: NA; Age: M = 22 | d,e |

| 8 | Michael (2020) [37] | Public | N = 8; Deaf (3), Physical (1), Blind (4); Sex: Male (6), Female (2); Age: NA | a,c,d |

| 9 | Michael (2020) [38] | Public | N = 4; Blind (1), Deaf (1), Physical (1), Intellectual (1); Sex: NA; Age: NA | a,b,c,d |

| 10 | Mujahid (2020) [39] | Public | N = 2; All Blind; Sex: Male (2); Age: M = 23,5 | c,d |

| 11 | Rahma et al. (2020) [40] | Public | N = 11; Physical (3), Deaf (4), Blind (4); Sex: Male (5), Female (6); Age: NA | a,b,c,d,e |

| 12 | Ratnasari (2021) [41] | Public | N = 2; Deaf (1), Physical (1); Sex: All female; Age: NA | a,b,c,e |

| 13 | Riahta et al. (2015) [42] | Public | N = 3; All Deaf; Sex: NA; Age: NA | d,e |

| 14 | Ro’fah et al. (2020) [43] | Public | N = 8; Sex: NA; Age: NA | a,b,c,d |

| 15 | Rosydi & Dewi (2020) [44] | Private | N = 3; All Physical; Sex: NA; Age: NA | c,d |

| 16 | Sari et al. (2022) [45] | Public | N = 8; Physical (1), Blind (4), Deaf (3); Sex: NA; Age: NA | a,b,c,d,e |

| 17 | Sudarwati et al. (2022) [46] | Public | N = 1; Physical; Sex: NA; Age: NA | a,c,d,e |

| Strategy | Definition | Perceived Norm | Perceived Control | Human Right Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptation | Adjustments or changes made by SwD to fit their HE environment. | Pressure to conform to HE norms that often lack inclusivity, SwD may hide or downplay their disability. | Controlling personal presentation and interactions, highlighting a gap between perceived and actual control. | Inadequacy of support systems; SwD should not have to compromise their identity to fit into the education system. |

| Assistive Technology Optimization | Utilization and optimization of technology to support academic tasks and overcome barriers. | Acceptance of assistive technology as a standard practice. | Enhance autonomy and manage academic responsibilities, improving perceived control over their learning environment. | Essential for ensuring equitable access; HE must provide necessary accommodations and support. |

| Requesting Support | Actively seek support, accommodation, and accessibility from their environment. | If Requesting Support is normalized, SwD are more likely to feel supported. If stigmatized, it can hinder effectiveness. | Seeking support to gain better control over their academic experience; success depends on the accessibility and reception of support. | Right to request and receive support without discrimination; institutions must ensure fair access to support. |

| Building Relationship | Initiation and establish connection with peers, lectures, and available support network. | Social support and connections are seen as normative; strong relationships facilitate access to help and reduce resistance. | Creates support networks that enhance control and reduce resistance, reflecting SwD’s efforts to gain influence and support in their academic setting. | Should have opportunities to form supportive relationships without feeling marginalized, supporting their right to social inclusion. |

| Passive Action | Less proactive stance, possibly due to perceived barriers and lack of resources. | If passive behavior is seen as a norm, it may lead to less encouragement for active participation. | Avoiding engagement; indicates a struggle with exerting control and utilizing available support effectively. | Should not be forced into passivity; systems should support active participation and remove barriers. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rahajeng, U.W.; Hendriani, W.; Paramita, P.P. Navigating Higher Education Challenges: A Review of Strategies among Students with Disabilities in Indonesia. Disabilities 2024, 4, 678-695. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4030042

Rahajeng UW, Hendriani W, Paramita PP. Navigating Higher Education Challenges: A Review of Strategies among Students with Disabilities in Indonesia. Disabilities. 2024; 4(3):678-695. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4030042

Chicago/Turabian StyleRahajeng, Unita Werdi, Wiwin Hendriani, and Pramesti Pradna Paramita. 2024. "Navigating Higher Education Challenges: A Review of Strategies among Students with Disabilities in Indonesia" Disabilities 4, no. 3: 678-695. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4030042

APA StyleRahajeng, U. W., Hendriani, W., & Paramita, P. P. (2024). Navigating Higher Education Challenges: A Review of Strategies among Students with Disabilities in Indonesia. Disabilities, 4(3), 678-695. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4030042