Differences in Health Status between People with and without Disabilities in Ecuadorian Prisons

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Variables

2.4. Data Processing and Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

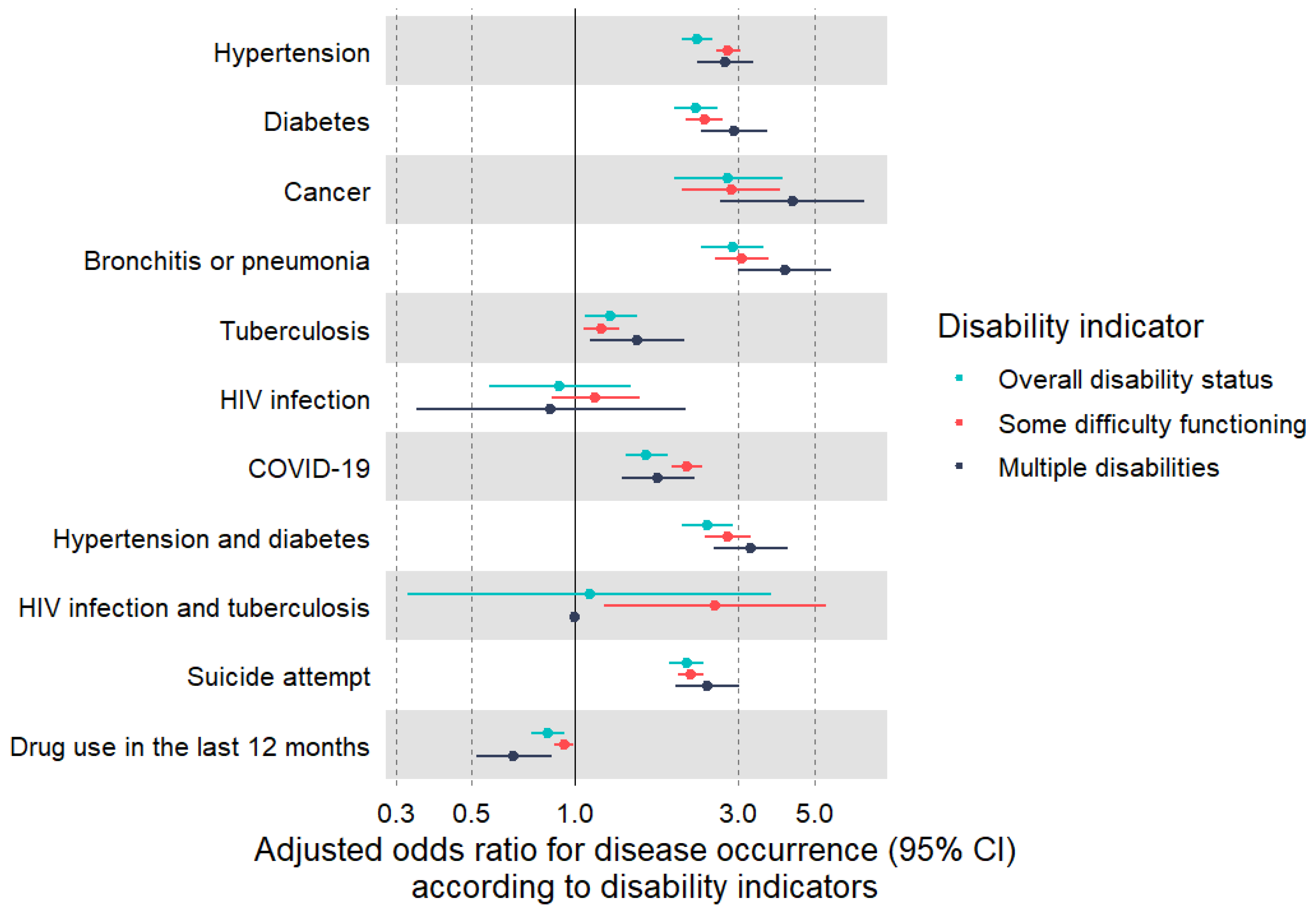

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Novisky, M.A.; Nowotny, K.M.; Jackson, D.B.; Testa, A.; Vaughn, M.G. Incarceration as a Fundamental Social Cause of Health Inequalities: Jails, Prisons and Vulnerability to COVID-19. Br. J. Criminol. 2021, 61, 1630–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Fact Sheet—Health in Prisons (2020). Available online: https://www.who.int/andorra/publications/m/item/fact-sheet---health-in-prisons-(2020) (accessed on 23 February 2024).

- Fazel, S.; Baillargeon, J. The Health of Prisoners. Lancet 2011, 377, 956–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndeffo-Mbah, M.L.; Vigliotti, V.S.; Skrip, L.A.; Dolan, K.; Galvani, A.P. Dynamic Models of Infectious Disease Transmission in Prisons and the General Population. Epidemiol. Rev. 2018, 40, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowotny, K.M.; Rogers, R.G.; Boardman, J.D. Racial Disparities in Health Conditions among Prisoners Compared with the General Population. SSM-Popul. Health 2017, 3, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atabay, T.; Vereinte Nationen (Eds.) Handbook on Prisoners with Special Needs; Criminal Justice Handbook Series; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-92-1-130272-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi, G.; Wickenden, M.; Bright, T.; Kuper, H. Barriers to Accessing Primary Healthcare Services for People with Disabilities in Low and Middle-Income Countries, a Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Studies. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 1207–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacinto, M.; Vitorino, A.S.; Palmeira, D.; Antunes, R.; Matos, R.; Ferreira, J.P.; Bento, T. Perceived Barriers of Physical Activity Participation in Individuals with Intellectual Disability—A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetherill, M.S.; Duncan, A.R.; Bowman, H.; Collins, R.; Santa-Pinter, N.; Jackson, M.; Lynn, C.M.; Prentice, K.; Isaacson, M. Promoting Nutrition Equity for Individuals with Physical Challenges: A Systematic Review of Barriers and Facilitators to Healthy Eating. Prev. Med. 2021, 153, 106723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gormley, C. The Hidden Harms of Prison Life for People with Learning Disabilities. Br. J. Criminol. 2022, 62, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, N.; Vélez-Grajales, V. Dentro de Las Prisiones de América Latina y El Caribe: Una Primera Mirada al Otro Lado de Las Rejas; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- García-Guerrero, J.; Marco, A. Sobreocupación En Los Centros Penitenciarios y Su Impacto En La Salud. Rev. Esp. Sanid. Penit. 2012, 14, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupers, T.A. Trauma and Its Sequelae in Male Prisoners: Effects of Confinement, Overcrowding, and Diminished Services. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 1996, 66, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bixby, L.; Bevan, S.; Boen, C. The Links between Disability, Incarceration, and Social Exclusion: Study Examines the Links between Disability, Incarceration, and Social Exclusion. Health Aff. 2022, 41, 1460–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, D.; Magasi, S.; Novak, C.; Harniss, M. Conducting Accessible Research: Including People with Disabilities in Public Health, Epidemiological, and Outcomes Studies. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 2137–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-kassab-Córdova, A.; Cornejo-Venegas, G.; Gacharna-Madrigal, N.; Baquedano-Rojas, C.; De La Borda-Prazak, G.; Mejia, C.R. Factores Asociados al Consumo Frecuente de Marihuana En Jóvenes Antes de Su Ingreso a Centros Juveniles de Diagnóstico y Rehabilitación En Perú. Adicciones 2021, 35, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Culquichicón, C.; Zapata-Castro, L.E.; Soto-Becerra, P.; Silva-Santisteban, A.; Konda, K.A.; Lescano, A.G. Contributing Factors for Self-Reported HIV in Male Peruvian Inmates: Results of the 2016 Prison Census. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1241042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos Censo Penitenciario 2022. Available online: https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/censo-penitenciario-2022/ (accessed on 23 February 2024).

- Washington Group on Disability Statistics. Creating Disability Severity Indicators Using the WG Short Set on Functioning (WG-SS) (Stata); Washington Group on Disability Statistics: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, M.A.; Schroeder, R.; Casebolt, M.T.; Laureano, B.I.; Wilson-Beattie, R.L.; Ralph, L.J.; Kaller, S.; Adler, A.; Gichane, M.W. Access to Reproductive Health Services among People with Disabilities. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2344877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comisión Interamericana de Derechos—Personas Privadas de Libertad en Ecuador. Available online: https://www.oas.org/es/cidh/informes/pdfs/Informe-PPL-Ecuador_VF.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2024).

- World Health Organization. Global Report on Health Equity for Persons with Disabilities; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; ISBN 92-4-006360-9. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240063600 (accessed on 23 February 2024).

- Orellano-Colón, E.M.; Suárez-Pérez, E.L.; Rivero-Méndez, M.; Boneu-Meléndez, C.X.; Varas-Díaz, N.; Lizama-Troncoso, M.; Jiménez-Velázquez, I.Z.; León-Astor, A.; Jutai, J.W. Sex Disparities in the Prevalence of Physical Function Disabilities: A Population-Based Study in a Low-Income Community. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakral, M.; Lacroix, A.Z.; Molton, I.R. Sex/Gender Disparities in Health Outcomes of Individuals with Long-Term Disabling Conditions. Rehabil. Psychol. 2019, 64, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisdom, J.P.; McGee, M.G.; Horner-Johnson, W.; Michael, Y.L.; Adams, E.; Berlin, M. Health Disparities between Women with and without Disabilities: A Review of the Research. Soc. Work Public Health 2010, 25, 368–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, E.M.; Van Voorhis, P.; Salisbury, E.J.; Bauman, A. Gender-Responsive Lessons Learned and Policy Implications for Women in Prison: A Review. Crim. Justice Behav. 2012, 39, 1612–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atabay, T. Handbook for Prison Managers and Policymakers on Women and Imprisonment; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 92-1-130267-6. [Google Scholar]

- Horner-Johnson, W.; Dobbertin, K.; Lee, J.C.; Andresen, E.M. Disparities in Chronic Conditions and Health Status by Type of Disability. Disabil. Health J. 2013, 6, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Bemd, M.; Schalk, B.W.M.; Bischoff, E.W.M.A.; Cuypers, M.; Leusink, G.L. Chronic Diseases and Comorbidities in Adults with and without Intellectual Disabilities: Comparative Cross-Sectional Study in Dutch General Practice. Fam. Pract. 2022, 39, 1056–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine. The Future of Disability in America; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; p. 11898. ISBN 978-0-309-10472-2. [Google Scholar]

- Vancampfort, D.; Schuch, F.; Van Damme, T.; Firth, J.; Suetani, S.; Stubbs, B.; Van Biesen, D. Prevalence of Diabetes in People with Intellectual Disabilities and Age- and Gender-matched Controls: A Meta-analysis. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2022, 35, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Winter, C.F.; Bastiaanse, L.P.; Hilgenkamp, T.I.M.; Evenhuis, H.M.; Echteld, M.A. Cardiovascular Risk Factors (Diabetes, Hypertension, Hypercholesterolemia and Metabolic Syndrome) in Older People with Intellectual Disability: Results of the HA-ID Study. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 33, 1722–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosetti, I.; Kuper, H. Do People with Disabilities Experience Disparities in Cancer Care? A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0285146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alene, K.A.; Wangdi, K.; Colquhoun, S.; Chani, K.; Islam, T.; Rahevar, K.; Morishita, F.; Byrne, A.; Clark, J.; Viney, K. Tuberculosis Related Disability: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Med. 2021, 19, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newell, V.; Phillips, L.; Jones, C.; Townsend, E.; Richards, C.; Cassidy, S. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Suicidality in Autistic and Possibly Autistic People without Co-Occurring Intellectual Disability. Mol. Autism 2023, 14, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, S.; Ware, R.S.; Kinner, S.A.; Lennox, N.G. Physical Health Outcomes in Prisoners with Intellectual Disability: A Cross-sectional Study. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2013, 57, 1191–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, L.C.; Coman, E.; Wakefield, D.; Trestman, R.L.; Conwell, Y.; Steffens, D.C. Functional Disability, Depression, and Suicidal Ideation in Older Prisoners. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 266, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravo-Cucci, S.; Cruz-Gonzales, G.; Medina-Espinoza, R.; Paca-Palao, A. The Comorbidity of Diabetes-Depression and Its Association with Disability amongst Elderly Prison Inmates. Rev. Esp. Sanid. Penit. 2022, 24, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Vásquez, A.; Rojas-Roque, C. Diseases and Access to Treatment by the Peruvian Prison Population: An Analysis According to Gender. Rev. Esp. Sanid. Penit. 2020, 22, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Addressing Health Inequities Faced by Persons with Disabilities to Advance Universal Health Coverage. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/addressing-health-inequities-faced-by-persons-with-disabilities-to-advance-universal-health-coverage (accessed on 23 February 2024).

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 28,703 (93.8) |

| Female | 1909 (6.2) |

| Age (years) | |

| Median [IQR] | 32.0 (26–40) |

| Age group | |

| 60 or older | 1048 (3.4) |

| 30–59 | 17,154 (56.0) |

| 18–29 | 12,410 (40.5) |

| Country of birth | |

| Ecuador | 27,449 (89.7) |

| Outside Ecuador | 3163 (10.3) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Other | 22,936 (74.9) |

| African descent | 6544 (21.4) |

| Indigenous | 1132 (3.7) |

| Educational level | |

| Up to primary | 6214 (20.3) |

| Secondary | 22,053 (72.0) |

| Higher | 2345 (7.7) |

| Time deprived of liberty | |

| <6 months | 5769 (18.8) |

| 6 months to <2 years | 10,322 (33.7) |

| ≥2 years | 14,521 (47.4) |

| Permanent difficulty walking, or going up or down stairs * | |

| No | 29,436 (96.2) |

| Yes | 1176 (3.8) |

| Permanent difficulty bathing, dressing, or feeding self * | |

| No | 30,258 (98.8) |

| Yes | 354 (1.2) |

| Permanent difficulty in speaking, communicating, or conversing * | |

| No | 30,508 (99.7) |

| Yes | 104 (0.3) |

| Permanent difficulty hearing, even when wearing a hearing aid * | |

| No | 30,261 (98.9) |

| Yes | 351 (1.1) |

| Permanent difficulty in seeing, even when wearing glasses * | |

| No | 29,535 (96.5) |

| Yes | 1077 (3.5) |

| Permanent difficulty in remembering, understanding, or concentrating * | |

| No | 30,162 (98.5) |

| Yes | 450 (1.5) |

| Male | Female | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | (n = 28,703) | (n = 1909) | (n = 30,612) |

| Permanent difficulty walking, or going up or down stairs | |||

| No difficulty | 25,080 (87.4) | 1650 (86.4) | 26,730 (87.3) |

| Some difficulty | 2541 (8.9) | 165 (8.6) | 2706 (8.8) |

| A lot of difficulty | 1007 (3.5) | 87 (4.6) | 1094 (3.6) |

| Total difficulty | 75 (0.3) | 7 (0.4) | 82 (0.3) |

| Permanent difficulty bathing, dressing, or feeding self | |||

| No difficulty | 27,499 (95.8) | 1841 (96.4) | 29,340 (95.8) |

| Some difficulty | 871 (3.0) | 47 (2.5) | 918 (3.0) |

| A lot of difficulty | 300 (1.0) | 15 (0.8) | 315 (1.0) |

| Total difficulty | 33 (0.1) | 6 (0.3) | 39 (0.1) |

| Permanent difficulty in speaking, communicating, or conversing | |||

| No difficulty | 27,916 (97.3) | 1868 (97.9) | 29,784 (97.3) |

| Some difficulty | 687 (2.4) | 37 (1.9) | 724 (2.4) |

| A lot of difficulty | 87 (0.3) | 3 (0.2) | 90 (0.3) |

| Total difficulty | 13 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 14 (0.0) |

| Permanent difficulty hearing, even when wearing a hearing aid | |||

| No difficulty | 26,992 (94.0) | 1815 (95.1) | 28,807 (94.1) |

| Some difficulty | 1374 (4.8) | 80 (4.2) | 1454 (4.7) |

| A lot of difficulty | 324 (1.1) | 13 (0.7) | 337 (1.1) |

| Total difficulty | 13 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 14 (0.0) |

| Permanent difficulty in seeing, even when wearing glasses | |||

| No difficulty | 24,677 (86.0) | 1535 (80.4) | 26,212 (85.6) |

| Some difficulty | 3051 (10.6) | 272 (14.2) | 3323 (10.9) |

| A lot of difficulty | 928 (3.2) | 102 (5.3) | 1030 (3.4) |

| Total difficulty | 47 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 47 (0.2) |

| Permanent difficulty in remembering, understanding, or concentrating | |||

| No difficulty | 25,788 (89.8) | 1626 (85.2) | 27,414 (89.6) |

| Some difficulty | 2501 (8.7) | 247 (12.9) | 2748 (9.0) |

| A lot of difficulty | 401 (1.4) | 36 (1.9) | 437 (1.4) |

| Total difficulty | 13 (0.0) | 0 (0) | 13 (0.0) |

| Some difficulty functioning | |||

| No | 20,667 (72.0) | 1263 (66.2) | 21,930 (71.6) |

| Yes | 8036 (28.0) | 646 (33.8) | 8682 (28.4) |

| Overall disability status | |||

| Without disabilities | 26,277 (91.5) | 1705 (89.3) | 27,982 (91.4) |

| With disabilities | 2426 (8.5) | 204 (10.7) | 2630 (8.6) |

| Multiple disabilities | |||

| No | 28,133 (98.0) | 1864 (97.6) | 29,997 (98.0) |

| Yes | 570 (2.0) | 45 (2.4) | 615 (2.0) |

| Some Difficulty Functioning | Overall Disability Status | Multiple Disabilities | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | No | Yes | Without Disabilities | With Disabilities | No | Yes | |

| Variable | (n = 30,612) | (n = 21,930) | (n = 8682) | (n = 27,982) | (n = 2630) | (n = 29,997) | (n = 615) |

| Hypertension | |||||||

| No | 27,292 (89.2) | 20,536 (93.6) | 6756 (77.8) | 25,396 (90.8) | 1896 (72.1) | 26,928 (89.8) | 364 (59.2) |

| Yes | 3320 (10.8) | 1394 (6.4) | 1926 (22.2) | 2586 (9.2) | 734 (27.9) | 3069 (10.2) | 251 (40.8) |

| Diabetes | |||||||

| No | 29,367 (95.9) | 21,395 (97.6) | 7972 (91.8) | 27,040 (96.6) | 2327 (88.5) | 28,873 (96.3) | 494 (80.3) |

| Yes | 1245 (4.1) | 535 (2.4) | 710 (8.2) | 942 (3.4) | 303 (11.5) | 1124 (3.7) | 121 (19.7) |

| Cancer | |||||||

| No | 30,449 (99.5) | 21,867 (99.7) | 8582 (98.8) | 27,866 (99.6) | 2583 (98.2) | 29,857 (99.5) | 592 (96.3) |

| Yes | 163 (0.5) | 63 (0.3) | 100 (1.2) | 116 (0.4) | 47 (1.8) | 140 (0.5) | 23 (3.7) |

| Bronchitis or pneumonia | |||||||

| No | 30,081 (98.3) | 21,709 (99.0) | 8372 (96.4) | 27,584 (98.6) | 2497 (94.9) | 29,520 (98.4) | 561 (91.2) |

| Yes | 531 (1.7) | 221 (1.0) | 310 (3.6) | 398 (1.4) | 133 (5.1) | 477 (1.6) | 54 (8.8) |

| Tuberculosis | |||||||

| No | 29,175 (95.3) | 20,952 (95.5) | 8223 (94.7) | 26,698 (95.4) | 2477 (94.2) | 28,604 (95.4) | 571 (92.8) |

| Yes | 1437 (4.7) | 978 (4.5) | 459 (5.3) | 1284 (4.6) | 153 (5.8) | 1393 (4.6) | 44 (7.2) |

| HIV infection | |||||||

| No | 30,403 (99.3) | 21,794 (99.4) | 8609 (99.2) | 27,793 (99.3) | 2610 (99.2) | 29,793 (99.3) | 610 (99.2) |

| Yes | 209 (0.7) | 136 (0.6) | 73 (0.8) | 189 (0.7) | 20 (0.8) | 204 (0.7) | 5 (0.8) |

| COVID-19 | |||||||

| No | 28,866 (94.3) | 21,030 (95.9) | 7836 (90.3) | 26,511 (94.7) | 2355 (89.5) | 28,333 (94.5) | 533 (86.7) |

| Yes | 1746 (5.7) | 900 (4.1) | 846 (9.7) | 1471 (5.3) | 275 (10.5) | 1664 (5.5) | 82 (13.3) |

| Hypertension and diabetes | |||||||

| No | 29,794 (97.3) | 21,638 (98.7) | 8156 (93.9) | 27,403 (97.9) | 2391 (90.9) | 29,286 (97.6) | 508 (82.6) |

| Yes | 818 (2.7) | 292 (1.3) | 526 (6.1) | 579 (2.1) | 239 (9.1) | 711 (2.4) | 107 (17.4) |

| HIV infection and tuberculosis | |||||||

| No | 30,582 (99.9) | 21,915 (99.9) | 8667 (99.8) | 27,955 (99.9) | 2627 (99.9) | 29,967 (99.9) | 615 (100) |

| Yes | 30 (0.1) | 15 (0.1) | 15 (0.2) | 27 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) | 30 (0.1) | 0 (0) |

| Suicide attempt | |||||||

| No | 28,106 (91.8) | 20,557 (93.7) | 7549 (87.0) | 25,883 (92.5) | 2223 (84.5) | 27,609 (92.0) | 497 (80.8) |

| Yes | 2506 (8.2) | 1373 (6.3) | 1133 (13.1) | 2099 (7.5) | 407 (15.5) | 2388 (8.0) | 118 (19.2) |

| Drug use in the last 12 months | |||||||

| No | 23,446 (76.6) | 16,456 (75.0) | 6990 (80.5) | 21,245 (75.9) | 2201 (83.7) | 22,902 (76.3) | 544 (88.5) |

| Yes | 7166 (23.4) | 5474 (25.0) | 1692 (19.5) | 6737 (24.1) | 429 (16.3) | 7095 (23.7) | 71 (11.5) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vargas-Fernández, R.; Hernández-Vásquez, A. Differences in Health Status between People with and without Disabilities in Ecuadorian Prisons. Disabilities 2024, 4, 646-657. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4030040

Vargas-Fernández R, Hernández-Vásquez A. Differences in Health Status between People with and without Disabilities in Ecuadorian Prisons. Disabilities. 2024; 4(3):646-657. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4030040

Chicago/Turabian StyleVargas-Fernández, Rodrigo, and Akram Hernández-Vásquez. 2024. "Differences in Health Status between People with and without Disabilities in Ecuadorian Prisons" Disabilities 4, no. 3: 646-657. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4030040

APA StyleVargas-Fernández, R., & Hernández-Vásquez, A. (2024). Differences in Health Status between People with and without Disabilities in Ecuadorian Prisons. Disabilities, 4(3), 646-657. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4030040