Abstract

Biofuels represent a viable alternative to fossil fuels due to their lower greenhouse gas emissions, potential for large-scale production, and renewable nature. Orange oil, turpentine, and their hydrogenated derivatives have emerged as promising candidates for biofuel components. Efficient design and operation of internal combustion engines require knowledge of biofuel density and viscosity as functions of temperature; however, experimental data on these properties remain limited. In this work, the densities and viscosities of turpentine, orange oil, hydrogenated turpentine, and hydrogenated orange oil were measured at atmospheric pressure over the temperature range (293.15–373.15) K. The measurements were performed with uncertainties below 0.05 kg·m−3 for density and 0.3 mPa·s for viscosity. The experimental data were correlated as a function of temperature using a quadratic function for density and the Andrade equation for viscosity, with absolute average relative deviations of 0.01% for density and 0.5% for viscosity. For all substances, both viscosity and density decrease with increasing temperature, and they are lower than the values for biodiesel. Orange oil and turpentine exhibited higher densities but lower viscosities than their hydrogenated counterparts, which can be attributed to differences in molecular size and packing efficiency. Finally, the measured density and viscosity values are compared with the limit values specified in the European and American biodiesel standards. The analysis shows that blending these essential oils with conventional biodiesel could result in biofuel mixtures that meet both standards.

1. Introduction

Global energy consumption is increasing rapidly, while traditional energy sources such as petroleum, coal, and natural gas are limited, non-renewable, and not easily accessible in all locations. Furthermore, rising emissions from these fuels contribute significantly to greenhouse gases and climate change. In fact, crude oil combustion is a major contributor to global greenhouse gas emissions; in 2024, global CO2 emissions from energy combustion and industrial processes grew by 1% (357 Mt) to reach a new all-time high of 37.8 Gt [1]. Consequently, there is growing interest in identifying alternative renewable fuel sources. Biofuels represent a viable alternative to fossil fuels due to their lower greenhouse gas emissions, potential for large-scale production, worldwide availability, and renewable nature. Biomass resources for biofuel production include agricultural residues (such as corn stover and straws), forestry products (including logging slash and pulping liquors), and other biomass sources (such as waste oils, industrial waste, vegetable oils, and plant oils) [2].

Vegetable oils from soybean, rapeseed, and sunflower cannot be used directly in direct-injection diesel engines because they cause coking after several hours of use. To make vegetable oils suitable for engine use, the fatty acids in these oils must be converted to fatty acid esters (FAEs) through transesterification, which is a process involving the reaction of fatty acids with an alcohol; the resulting product is known as biodiesel [3]. A less common alternative is the use of essential oils, which can be extracted from leaves, wood, grass, resins, and fruit peels. Essential oils have several key properties that differ considerably from biodiesel. While biodiesel contains mainly fatty acid esters (FAEs), essential oils contain terpene-related hydrocarbons and oxygenated compounds. Essential oils have a lower viscosity and similar heating value compared to biodiesel, which makes them an interesting prospect as a fuel alternative. Among these, orange oil and turpentine have been recently studied in the literature [4].

Turpentine is a bio-based product obtained mainly from pine species such as Pinus palustris (longleaf pine) and Pinus sylvestris (Scots pine), consisting primarily of terpenes—mainly α-pinene and β-pinene—whose proportions vary depending on its origin. It is obtained through two main processes. The first involves vacuum distillation of pine resin (a secondary product of the resin industry), producing turpentine as the distillate and a residue called rosin, whose main components are diterpenes (C20) with carboxylic acid functionality [5]. The second process produces crude sulphate turpentine (CST) as a by-product of the kraft pulping process, where wood chips are processed to produce pulp for paper manufacturing [6]. Although turpentine has traditionally served as a solvent for paints and varnishes, it qualifies as an advanced biofuel because it originates from by-products of paper and forest-based industrial processes. Orange oil, composed of over 90% d-limonene, is extracted from orange peels—a by-product of the juice industry—using cold pressing, solvent extraction, or steam distillation; it is employed as raw oil in the nutraceutical industry as an additive [7], and has recently been proposed as a biofuel, since it originates from the residual orange peel [4].

Studies in the literature have examined the performance and emissions of diesel engines using turpentine [8,9], orange oil [10,11], and their blends with diesel and biodiesel [12], as well as the fuel properties of these mixtures for automotive applications [12,13]. In addition, turpentine and orange oil have been blended with jet fuel, and their properties have been investigated as bio-based components for aviation fuels [14,15]. However, the presence of unsaturated hydrocarbons and cyclic molecular structures in orange oil and turpentine tends to promote the formation of solid carbon (soot) particles during combustion, which is a disadvantage for their use as biofuels. Therefore, several studies in the literature have proposed various modification strategies—such as hydrogenation [13] and oxyfunctionalization [8]—for these essential oils to mitigate this issue. Nevertheless, essential oils and their blends with biodiesel or diesel can enhance engine performance, likely due to improved atomisation from lower viscosity. They may also increase thermal efficiency and reduce hydrocarbon and CO emissions, depending on oil composition, blend ratio, and injection pressure [4,9].

Biofuel thermodynamic properties, such as density and viscosity, affect engine design, operating parameters, performance, combustion behaviour, and emissions. Density is significant because fuel injection systems deliver a fixed volume of fuel, while combustion depends on the mass of fuel in the fuel–air ratio. Higher-density fuels also contain more energy per unit volume under optimal combustion conditions [16]. However, higher-density fuels may require earlier injection timing, which can raise cylinder temperatures and increase emissions of NOx, soot, CO, and hydrocarbons [17,18]. On the other hand, the viscosity of fuel affects both the fuel pump and injector behaviour, and the atomisation process in the fuel injector nozzle holes [19]. High-viscosity fuels impede atomisation, producing larger droplets and leading to poor mixing that result in slower, incomplete combustion, increased emissions of particulate matter, and unburned hydrocarbons. Low-viscosity fuels can lower emissions but may raise NOx levels due to higher combustion temperatures [4]. Therefore, optimal viscosity promotes effective spray and mixing, resulting in improved efficiency of the combustion [3]. Consequently, to ensure optimal engine performance, international standards establish reference values for biofuel density and viscosity under specified temperatures and atmospheric pressure. The European biodiesel specification EN 14214 [20] prescribes a density range of 860–900 kg/m3 at 288.15 K and a kinematic viscosity range of 3.5–5.0 mm2/s at 313.15 K.

In comparison, the ASTM D6751 [21] standard defines a broader kinematic viscosity range of 1.9–6.0 mm2/s at 313.15 K and does not specify density limits [8]. Furthermore, understanding how the density and viscosity of biofuels vary with temperature is essential for designing an efficient internal combustion engine. Hence, numerous empirical correlations have been proposed to describe the density and viscosity of biodiesel as functions of temperature using some parameters [22]. However, to develop these correlations, experimental density and viscosity data as a function of temperature are required. To date, only a limited number of studies have investigated the temperature dependence of the density of orange oil [23,24] and turpentine [24]. Similarly, only one study has reported the viscosity of orange oil as a function of temperature [23], while no viscosity data are available for turpentine. Furthermore, no information exists on the variation in density or viscosity with temperature for hydrogenated turpentine or hydrogenated orange oil.

In this context, the present work aims to provide novel experimental data on viscosity and density as functions of temperature for orange oil, turpentine, hydrogenated orange oil, and hydrogenated turpentine, with views on their potential application as biofuel components. In addition, the variation in viscosity and density with temperature has been correlated using empirical equations that can be implemented in engineering simulation software for property prediction. The results were compared with limited published data on these essential oils to validate our measurements. Finally, the measured density and viscosity are critically evaluated against automotive fuel standards (EN 14214 and ASTM D6751) to determine whether these novel biofuels are suitable for combustion engine applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Orange oil, 78% hydrogenated orange oil, and 98% hydrogenated turpentine were generously provided by Dr David Donoso (Grupo de Combustibles y Motores, Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, Ciudad Real, Spain) and used as received. The composition of the turpentine and orange oil was reported by Donoso et al. [13,14,15]. Table 1 represents the main components of the turpentine and orange oil. Compositions of 59% hydrogenated turpentine and 51% hydrogenated orange oil were also reported by Donoso et al. [13,14,15] and the main components of those are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The main components of orange oil, hydrogenated orange oil, turpentine, and hydrogenated turpentine in per cent of mass (mass%) [13,14,15].

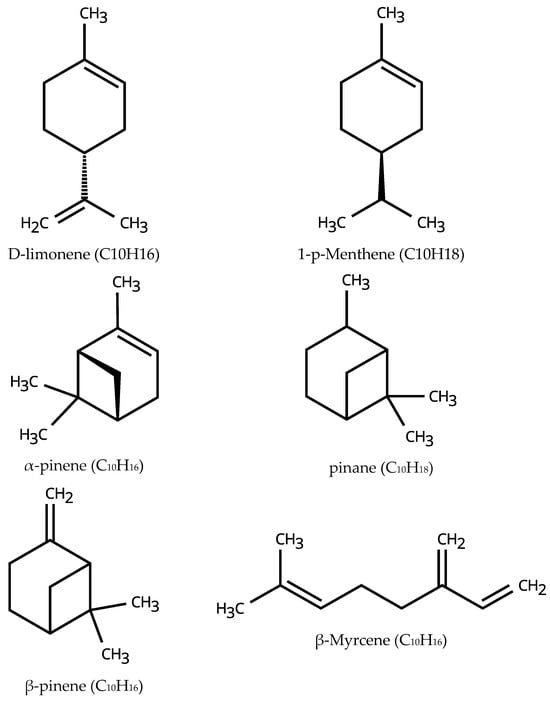

98% Hydrogenated turpentine and 78% hydrogenated orange oil were not analysed. Nevertheless, the primary constituents are expected to be pinane for 98% hydrogenated turpentine and 1-p-menthene for 78% hydrogenated orange oil, respectively, as subsequent hydrogenation would exclusively saturate the remaining carbon–carbon double bonds of the unsaturated species. Figure 1 represents the chemical structure of the main components of the oils. General Purpose Viscosity Standard oil, N2500, Paragon Scientific Ltd., sourced by Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), was used to validate the densimeter and viscometer. Further validation of the densimeter was performed using ethanol (99%, extra pure, Fisher Chemical, Waltham, MA, USA).

Figure 1.

The chemical structure of the main components of orange oil, hydrogenated orange oil, turpentine, and hydrogenated turpentine.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Densimeter

An Anton Paar DMA 4501 [25] vibrating tube (Graz, Austria) digital densimeter was used to measure the density of each oil. The oscillating U-tube method measures the density of liquids and gases by electronically detecting the oscillation frequency of a U-shaped glass tube filled with the sample. Based on the mass–spring model, the tube’s eigenfrequency, influenced by the samples mass, is used to calculate density. The tube oscillates perpendicular to its branches, with only the sample volume between the bearing points affecting the frequency, ensuring precise density measurements when filled to these points [26]. Before performing the measurements, the densimeter was calibrated in situ using air and distilled water (MilliPore Q, resistivity > 18 MΩ·cm at T = 298.15 K). The working equation obtained from the calibration was reported in previous studies [27].

Initially, the oil sample was sonicated in an ultrasonic bath for 10 min at ambient temperature to degas the oil. In the meantime, the vibrating tube was washed with ethanol and flushed with air several times. Then, the air density at atmospheric pressure and 293 K was measured to ensure that the tube was sufficiently clean to provide reliable data. Once oil was degassed and the tube was clean, one millilitre of oil was injected into the U-tube using the 5 mL syringe that remained attached to the instrument during measurements. Once a stable temperature was achieved, oscillation periods were automatically recorded at temperatures from 293 K to 373 K in 5 K intervals at atmospheric pressure, 0.1 MPa. The oscillation periods and temperatures were recorded with an accuracy of ±0.01 μs and ±0.01 K, respectively. After the measurements, the temperature was decreased to 293 K, and the sample was flushed with ethanol several times until all sample material was removed. Again, the air density was measured to ensure the cleanest state of the tube. For each oil, the measurements were performed for at least two samples. The density was calculated using the calibration working equation with the measured oscillation period and temperature [27]. Density measurements were repeated three times for each sample, and the repeatability of density was 0.009 kg·m−3.

Uncertainty Analysis. The total uncertainties for the reported densities were estimated following GUM guidelines [28]. Density uncertainties arise from multiple sources, including temperature and oscillation period measurements, initial calibration procedures, and random errors associated with thermal stability and vibration effects. The oscillation period was measured with an accuracy of 0.01 μs across a range of 2500.00 to 3700.00 μs. Temperature control maintained an uncertainty of ±0.01 K throughout the measurements. Random uncertainties were quantified using the standard uncertainty formula uR(η) = s/√n, where s represents the standard deviation and n is the number of repetitions. The combined uncertainty approach was used and expressed in the following equation:

where ρ is density; τ is period of oscillation; and T is temperature.

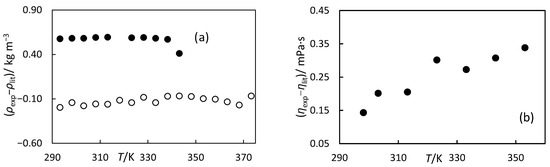

Validation: The calibration and methodology were validated by measuring the density of general purpose standard oil N2500 from Paragon Scientific and ethanol at temperatures from 298 K to 373 K, as shown in Table 2. The experimental data for the standard oil were compared with the data provided by the Paragon; they have an expanded relative uncertainty of ±0.01% for k = 2 with 95% confidence. The measured ethanol densities were compared against calculated values from the equation developed by Schroeder et al. [29] as implemented in REFPROP10 [30]. This equation has a reported density uncertainty of 0.2%. Table 2 and Figure 2 show the relative deviation and deviation between the experimental data and reference data, respectively. As seen in Table 2, the experimental data for the standard oil and ethanol are in good agreement with the data reported by the manufacturer and the standard equation, respectively. The absolute average deviation (AAD) and absolute average relative deviation (AARD) are defined as follows:

where x is the measured property, N is the number of experimental data points, the superscript ‘exp’ indicates experimental data, and superscript ‘cal’ indicates calculated data from the equation or literature values. The AARD for the standard oil was 0.02%, while the AARD for ethanol was 0.07%. These deviations for both substances fell within both the reported uncertainties and our experimental uncertainties, also given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Densities, ρexp, of N2500 standard oil and ethanol, temperatures, T, and densities reported, ρlit for N2500 standard oil by manufacturers and for ethanol by Schroeder et al. [29].

Figure 2.

(a) Difference in density measurements, ρexp, in this work and values, ρlit, for N2500 standard oil (○) reported by Paragon Scientific and for ethanol (●) from the equation proposed by Schroeder et al. [29]. (b) The difference between the measured viscosity ηexp in this work and the values reported, ηlit, by Paragon Scientific.

2.2.2. Viscometer

An ROTAVISC lo-vi Complete digital viscometer from IKA (Oxford, UK), with a cylinder chamber of 6.7 mL, VOLS-1, was used to measure the viscosity data. A heating circulator HRC-2 from IKA, attached to a heat jacket that encased the cylinder chamber, was used to control the temperature from 253.2 K to 373.2 K with an uncertainty of ± 0.1 K. The water recirculates through the jacket at 2000 rpm, ensuring uniform temperature control. The temperature of the fluid is measured by a Pt-100 temperature sensor attached to the cylinder chamber. The spindle used was designed to measure viscosity from 1.5 mPa∙s to 30,000 mPa∙s with an accuracy of 2% for the ROTAVISC lo-vi viscometer. The viscometer operates on the principle that a rotating spindle immersed in the fluid experiences viscous drag forces proportional to the fluid’s viscosity. This rotational resistance generates a measurable torque, which is quantified through a calibrated spring mechanism. The experimental method proceeded as follows. Approximately 6.5 mL of oil was loaded into the viscometer chamber, and the initial temperature was set to 293 K. The spindle was then immersed in the oil sample, and the rotational speed (rpm) was adjusted to maintain shear stress within the operational range of 10–100%. Viscosity measurements were taken from 293 K, with 5 K intervals, until the temperature at which the oil’s viscosity dropped below 1.5 mPa·s and the percentage of shear stress was lower than 10%. At each temperature point, three viscosity measurements were recorded over 10 min. The data recorded included viscosity, shear stress, shear strain rate, RPM, percentage of shear stress, and temperature. The measurements were performed for two samples of oils to ensure measurement reliability. The repeatability of the viscosity measurements was determined to be less than 2%.

Uncertainty analysis. Viscosity uncertainty was evaluated following the methodology outlined in the Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement (GUM) [28]. The uncertainty in viscosity measurements originates from several sources. The primary contribution comes from the direct measurement process, which exhibits an uncertainty of approximately 3% full-scale range according to manufacturer specifications (. Temperature variations represent an additional source of measurement uncertainty. Random uncertainties also influence the overall measurement accuracy, encompassing factors such as sample preparation, spindle alignment, thermal instability, mechanical vibrations, and other operational variables. These random uncertainties were quantified using the standard uncertainty equation: uR(η) = s/√n, where s represents the standard deviation of repeated measurements and n denotes the number of repetitions. Following GUM guidelines, the combined uncertainty in viscosity measurements was determined using the uncertainty propagation equation:

Validation The Ika viscosimeter was validated by measuring the viscosity of N2500 standard oil, whose viscosity is certified by ISO 17,034 [31] and UKAS ISO/IEC17025 [32] and it covers viscosity from 4 mPa s−1 to 1 mPa s−1 with an expanded uncertainty of ±0.1%. Table 3 shows our measured viscosity data and Paragon Scientific’s reference values. The combined uncertainty in viscosity measurements is also given in Table 3. The differences between the two datasets are presented in Table 3 and Figure 2b. As seen from the table and figure, AAD between both sets of data were about 0.25 mPa∙s. These values were within our uncertainty.

Table 3.

The viscosity of the N2500 standard oil measured in this work, ηexp, and the standard reference values, ηlit, are reported by Paragon Scientific. (ηexp − ηlit) is the difference between the two values.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Density

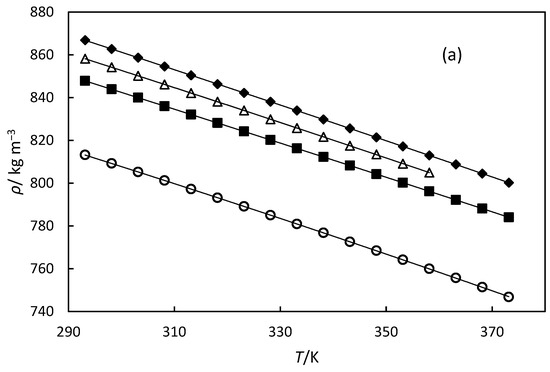

The densities of orange oil, 78% hydrogenated orange oil, turpentine, and 98% hydrogenated turpentine were measured at 0.1 MPa over temperature ranges of 293–373 K, and they are shown in Table 4 and Figure 3. We were unable to measure density beyond 385 K for 98% hydrogenated turpentine, as we observed higher uncertainty in the measurements of this oil. This may be due to some components of the hydrogenated turpentine beginning to boil at that temperature. The uncertainty of the measurements is also presented in the table, indicating that the measurements have excellent accuracy. The density values for the four oils decrease linearly with increasing temperature, as seen from Figure 3. Turpentine and hydrogenated turpentine display higher densities compared to orange oil and hydrogenated orange oil, respectively. This suggests that α-pinene and β-pinene, and pinane, which are the main terpene constituents of turpentine oils, and 98% hydrogenated turpentine, respectively, pack more efficiently than limonene (the predominant terpene in orange oil) and 1-p-menthene (the main component of hydrogenated orange oil).

Table 4.

Experimental densities (ρ) of the orange oil, the 78% hydronated orange oil, turpentine, and 98% hydrogenated turpentine at different temperatures, T, and atmospheric pressure (P = 0.10 MPa). u (ρ) represents density uncertainty.

Figure 3.

(a) Experimental densities versus temperature. The line represents the fitting of Equation (5) with the parameters of Table 5. (b) Deviations between experimental densities and those calculated by Equation (5) versus temperature. For (a,b), the symbols denote the different oils: orange oil (■), 79% hydrogenated orange oil (○), turpentine (◆), and 98% hydrogenated turpentine (△).

Additionally, orange oil and turpentine exhibited higher densities than their respective hydrogenated counterparts. During hydrogenation, the double bonds present in molecules such as limonene or α-pinene undergo saturation, yielding primarily saturated derivatives of compounds such as 1-p-Menthene or pinane. Unsaturated molecules exhibit greater molecular volume compared to their saturated counterparts (see Figure 1). Therefore, hydrogenation increases molecular size and reduces packing efficiency, resulting in a higher volume for the same mass, and consequently, lower density. Notably, hydrogenation has a more substantial effect on orange oil than on turpentine oil, suggesting that unsaturated molecules in hydrogenated orange oil exhibit less effective molecular packing.

Modelling. The experimental density values were fitted as a function of temperature using a polynomial equation of the following form:

where ρ is density in kg m−3, and T is temperature in K. The values of parameters A, B, and C for all oils are presented in Table 5, along with the AAD and AARD between the experimental and calculated data. The polynomial correlation is illustrated in Figure 3a. Figure 3b shows the deviations in the experimental density data from the values calculated using this correlation. These deviations are comparable to the experimental uncertainty, indicating that Equation (5) provides a good representation of the data. We also modelled the data with a linear correlation, but the ADD and AARD values exceeded the experimental uncertainty of our measurements.

Table 5.

Parameters A, B, and C of Equation (5) for various oils and the absolute average deviation (AAD), absolute average relative deviation (AARD), and root mean square error (RMSE) between the experimental and calculated data.

The composition of orange oil and turpentine varies depending on citrus or pine species, seasonal variations, and extraction methodology. As a result, direct quantitative comparison between our density data and literature values cannot be made with certainty. However, approximate comparisons remain feasible given that the main components, limonene and (α-pinene and β-pinene), are the same for orange oil and turpentine, respectively. Table 6 presents literature density values for different orange oils, turpentine oils, hydrogenated orange oil, and hydrogenated turpentine, and the major components of those oils, including limonene, α-pinene, β-pinene, and pinane.

Table 6.

Literature density (ρ) data versus temperature (T) for orange oil, hydrogenated orange oil, turpentine, hydrogenated turpentine, limonene, α-pinene, β-pinene, and pinane. The main components of these substances are presented in mass per cent.

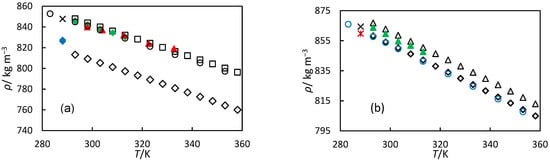

Our experimental data for orange oil are compared with the selected literature data in Figure 4a. As seen from the figure and Table 3 and Table 6, our data are in good agreement with literature values. The observed differences may be attributed to variations in orange oil composition, as well as the apparatus used in the measurements. For hydrogenated orange oil, we only found a datum for 51% hydrogenated oil and 47% hydrogenated d-limonene at 288 K from Donoso et al. [15]. Their data are presented in Figure 4a and given in Table 6. These data also follow the same trend as our data for 78% hydrogenated orange oil. Their density values are slightly higher than our trend line, which is logical since our oil has higher hydrogenation and therefore should exhibit lower density. It would be interesting to compare our data with density values for 1-p-menthene, which is the main component of hydrogenated oil, but unfortunately, no data are available for this compound.

Figure 4.

Experimental densities versus temperature: (a) for orange oil (☐) and 79% hydrogenated orange oil (◇) from this work. Literature density data are shown for orange oil from (◆) Tavares Sousa and Nieto de Castro [24], (❌︎) Donoso et al. [15], (▲) Fortunatti–Montoya et al. [23], and for d-limonene from (○) Clara et al. [33], and for 51% hydrogenated orange oil and 47% hydrogenated d-limonene (◆) from Donoso et al. [15]; (b) shows turpentine (△) and 98% hydrogenated turpentine (◇) in this work. Literature density data for turpentine from (▲) Tavares Sousa and Nieto de Castro [24], and (❌︎) Donoso et al. [14], as well as for pinane reported by (○) Wu et al. [35] and for 59% hydrogenated turpentine from (✱) Donoso et al. [14].

Our experimental turpentine density data are compared with the literature values in Figure 4b. As seen from Figure 4b, our data are in good agreement with literature values reported by Tavares Sousa and Nieto de Castro [24]. The observed differences may be attributed to variations in oil composition. Donoso et al. reported density measurements for the same turpentine as the one measured here and 59% hydrogenated turpentine at 288 K (Figure 3, Table 6) [14]. Their values are lower than ours, likely due to different measurement methodologies and higher experimental uncertainties in their data. Comparison with pinane density data is particularly relevant since it represents the primary component of hydrogenated turpentine. Figure 4b shows this comparison, and good agreement is observed between pinane densities measured by Wu et al. [35] and our measurements for 98% hydrogenated turpentine. This suggests that at 98% hydrogenation of turpentine, essentially all α-pinene and β-pinene were converted to pinane. This demonstrates that the composition of the 98% hydrogenated turpentine is predominantly pinane.

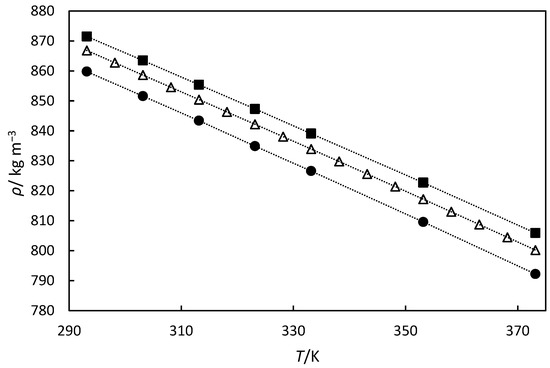

Given that the literature density data exists for the major turpentine components α-pinene and β-pinene [30], we compared these values with our turpentine density measurements in Figure 5. We can see that our data fall between these component values, although β-pinene comprises only 21% of the composition. This might indicate that the other components of the oil, which represent approximately 12%, have higher densities. This also demonstrates that we cannot predict turpentine density using only the two major components.

Figure 5.

Experimental densities versus temperature for turpentine (△) in this work, and β-pinene (■) and α-pinene (●) from Grozdanić et al. [34] The dashed line is to guide the eye.

3.2. Viscosity

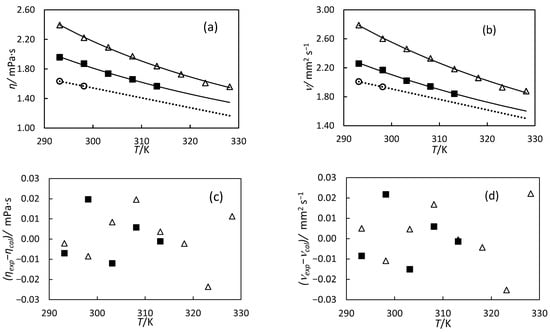

The dynamic viscosity measurements are presented in Table 7 and Figure 6a for turpentine oil at temperatures ranging from 293 to 313 K, 98% hydrogenated turpentine oil at temperatures ranging from 293 to 328 K, and 78% hydrogenated orange oil at temperatures of 293 K and 298 K. Measurements could not be obtained for pure orange oil using our viscometer, and measurements for the other oils could not be extended beyond the temperatures reported in the table. This limitation arose because the torque percentage (M%) of the viscometer’s motor fell below 10% when measuring orange oil and when measuring the other oils at temperatures above those reported. The M% reflects the motor’s effort to rotate the spindle and is used to calculate viscosity. When M% drops below 10%, the torque is too low for the viscometer’s sensor to provide accurate and reproducible results due to insufficient sensitivity and signal-to-noise issues. Consequently, the experimental dataset contains limited viscosity measurements for the turpentine and hydrogenated oils and no data for pure orange oil, as their viscosity values fell outside the measurable range of our viscometer. As shown in Figure 6, the viscosities of three oils decrease with increasing temperature, as expected. As the temperature increases, the thermal energy increases, allowing molecules to overcome intermolecular forces more easily, so molecular motion increases, reducing the “stickiness” between molecules.

Table 7.

Experimental viscosities (η), density (ρ), and kinematic viscosity (ν) for turpentine, 98% hydrogenated turpentine, and 78% hydrogenated orange oil at different temperatures, T, and at atmospheric pressure (0.10 MPa).

Figure 6.

(a) Experimental viscosity, η, versus temperature, T. The line represents the fitting of Equation (7) with the parameters of Table 8. (b) Experimental kinematic viscosity, ν, versus temperature, T. The line represents the fitting of Equation (8) with the parameters of Table 8. (c) Deviations between experimental viscosity and those calculated by Equation (7) versus temperature. (d) Deviations between experimental kinematic viscosity and those calculated by Equation (8) versus temperature. For all graphs, the symbols denote the different oils: 79% hydrogenated orange oil (○), turpentine (■), and 98% hydrogenated turpentine (△). The dotted line is to guide the eye.

The viscosity measurements reveal that both turpentine oil and hydrogenated turpentine oil exhibit higher viscosity than hydrogenated orange oil. This difference can be attributed to the structural characteristics of their constituent molecules: the bicyclic structures of α-pinene and β-pinene in turpentine are more rigid and compact than the monocyclic structure of limonene in orange oil, leading to stronger intermolecular interactions and increased resistance to flow. In contrast to density behaviour, the viscosity of hydrogenated turpentine is higher than that of pure turpentine oil. This increase in hydrogenation occurs because the conversion of double bonds to single bonds (α-pinene and β-pinene, C10H16 → pinane, C10H18) adds hydrogen atoms, slightly increasing the molecular weight, and that might increase viscosity.

The kinematic viscosity was calculated from the experimental dynamic viscosity and density values obtained in this study using the following equation:

where ν is the kinematic viscosity, η is the dynamic viscosity, and ρ is the density. The kinematic viscosity as a function of temperature is presented in Figure 6b. The kinematic viscosity follows the same trend as dynamic viscosity, decreasing with increasing temperature. Hydrogenated turpentine exhibits the highest kinematic viscosity, while orange oil shows the lowest kinematic viscosity.

Modelling. The Andrade equation [36] was used to fit the dynamic viscosity and kinematic viscosity of turpentine and hydrogenated turpentine oils. The equation is as follows for the following:

Dynamic viscosity:

Kinematic viscosity:

where η is dynamic viscosity, ν is kinematic viscosity, T is absolute temperature in Kelvin, A is the pre-exponential factor related to viscosity at infinite temperature, and b is the activation energy parameter related to the energy barrier for the molecular motion. The Andrade equation was used to model viscosity because it effectively describes the exponential temperature dependence of liquid viscosity over moderate temperature ranges. The Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm was used to minimise the sum of squared differences between experimental and calculated viscosities. The correlations and the differences between the calculated and experimental data are shown in Figure 6. The adjusting parameters, along with the AAD and AARD, are presented in Table 8. The 98% hydrogenated turpentine shows a slightly higher activation energy compared to the non-hydrogenated sample, suggesting an increased barrier to molecular mobility. This results in a higher viscosity and a stronger dependence of viscosity on temperature. The equation satisfactorily represents the data, with AAD values lower than our experimental uncertainty for both oils. The deviations between experimental and calculated viscosities are also lower than our uncertainty, as shown in Figure 6c,d.

Table 8.

Parameters A and b of Equations (7) and (8) for the dynamic and kinematic viscosities of both oils, along with the absolute average deviation (AAD), absolute average relative deviation (AARD) of the fitting, and root mean square error (RMSE).

Although the composition of orange oil and turpentine varies, preventing direct comparison of viscosity values, approximate comparisons can be performed based on their similar major components, as discussed previously. Table 9 presents the literature viscosity values for orange oils, turpentine oils, hydrogenated orange oil, hydrogenated turpentine, and their major components, including limonene, α-pinene, β-pinene, and pinane. As seen from the table, fewer viscosity data are available for these components compared to density data.

Table 9.

Literature dynamic viscosity (η) and kinematic viscosity (ν) data at different temperatures (T) for orange oil, hydrogenated orange oil, turpentine, hydrogenated turpentine, limonene, α-pinene, β-pinene, and pinane. The principal components of these substances are presented in mass per cent.

Table 9 shows that the dynamic and kinematic viscosities of limonene and orange oil are below 1 mPa·s and 1 mm2·s−1, respectively. These values fall below our viscometer’s measurement range, which has a lower limit of 1.5 mPa·s. For hydrogenated orange oil, only kinematic viscosity data for 51% hydrogenated orange oils and 47% hydrogenated limonene at 313 K were found in the literature [15]. Both literature values are lower than those measured for our 79% hydrogenated orange oil at 298 K. This is expected because viscosity decreases with increasing temperature and increases with the degree of hydrogenation. Therefore, the data reported by Donoso et al. [15] at higher temperature and lower hydrogenation levels are reasonably lower than our measurements.

Donoso et al. measured the kinematic viscosity of the same turpentine at 313 K under the same conditions employed in this study. [14] Their reported value of 1.35 mm2·s−1 is lower than our measured value of 1.84 mm2·s−1. However, considering the experimental uncertainties (0.4 mm2·s−1 for our measurements versus 0.01 mm2·s−1 for theirs), the two values show reasonable agreement. Donoso et al. [14] also measured the kinematic viscosity of 59% hydrogenated turpentine at 313 K, reporting a value of 1.70 mm2·s−1, which is lower than our measured value of 2.18 mm2·s−1 for 98% hydrogenated turpentine. This difference is expected since viscosity increases with the degree of hydrogenation. Since our turpentine was hydrogenated to 98%, it is expected that all β-pinene and α-pinene were converted to pinane. Therefore, we compared our viscosities of 98% hydrogenated turpentine with the literature data for pinane [35] in Figure 7a. Our data show good agreement with the literature values, with differences attributable to the experimental uncertainties. Finally, in Figure 7b, we compared the viscosity values for the turpentine with the main components of turpentine, α-pinene, and β-pinene, measured in the literature [33,37]. Our data are closer to the β-pinene values, which show higher viscosity. The viscosity of α-pinene is lower than our measured values. These differences may be attributed to variations in measurement methods, compositional differences in the samples, and experimental uncertainties.

Figure 7.

Experimental dynamic viscosity versus temperature (a) for 98% hydrogenated turpentine △ from this work and the literature data for pinane reported by (▲) Wu et al. [35]. (b) shows turpentine (☐) in this work. Literature data for α-pinene (●) reported by Clara et al. [33] and β-pinene (●) by Francesconi et al. [37]. The dotted line is to guide the eye.

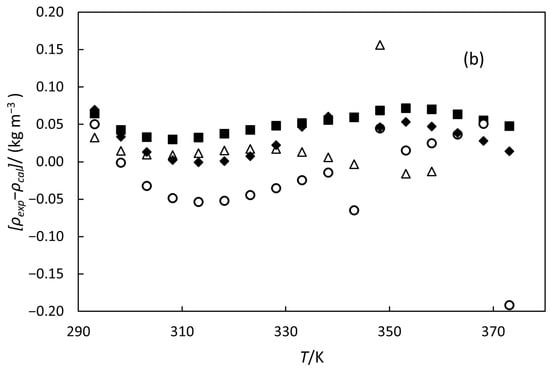

3.3. Comparison with Standards

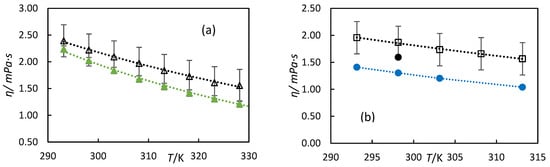

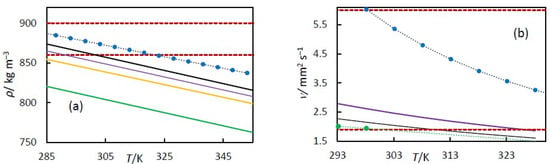

Higher-density biofuels can improve engine performance by providing more energy per unit volume. However, if the fuel is too dense, it may decrease efficiency and increase emissions due to the need for earlier injection timing, which raises cylinder temperatures. To optimise these properties and ensure consistent engine performance, international standards have established reference values for biofuel density. According to the European biodiesel specification EN 14214 [20], the acceptable density range is 860–900 kg/m3 at 288.15 K. Figure 8 presents the densities measured in this study alongside the limits defined by EN 14214. Only turpentine and 98% hydrogenated turpentine fall within the specified range. For comparison, the density of SoyA biodiesel reported by Pratas et al. [38] is also shown in the figure and lies between the limits of the EN 14214 standard. Therefore, blends of turpentine and 98% hydrogenated turpentine with this biodiesel would comply with the European standard across the entire composition range, as previously reported in the literature [13].

Figure 8.

(a) Densities versus temperatures for different biofuels. The solid line represents the fitting density of Equation (5) for essential oils in this work. The blue circle symbol represents the experimental density of soyA biodiesel reported by Pratas et al. [38]. The dashed red lines are the density limit for biodiesel established by EN 14214. (b) Kinematic viscosity versus temperatures for different biofuels. The solid lines represent the fitting kinematic viscosity of Equation (8) for essential oils in this work. The blue circle symbol represents the kinematic viscosity of soyA biodiesel reported by Freitas et al. [39]. The dashed red lines are the kinematic viscosity limits for a biodiesel established by ASTM D6751. For (a,b), the colours of the solid lines represent orange oil (orange), 79% hydrogenated orange oil (green), turpentine (black), and 98% hydrogenated turpentine (purple) in this work. The dotted line is to guide the eye.

However, as seen in Figure 8a, orange oil and hydrogenated orange oil do not comply with the EN 14214 standard on their own and therefore need to be blended with biodiesel. To determine the appropriate proportion of each oil in the blend, Kay’s mixing rule for density can be applied [35]. This rule states that the density of a mixture can be obtained by summing the products of the component densities and their corresponding volume fractions, as expressed by the following:

where fvi is the volume fraction, and ρi is the density of component i. In this case, the two components are soyA biodiesel and orange oil (or hydrogenated orange oil). The density of soyA biodiesel can be taken from the experimental data reported by Pratas et al. [33] and shown in Figure 8, with a value of 884.7 kg·m−3 at 288.15 K. The densities of orange oil and hydrogenated orange oil, calculated using Equation (5) at 288 K, are 851.78 kg·m−3 and 817.17 kg·m−3, respectively. According to EN 14214, the minimum acceptable density for biofuel is 860 kg·m−3. Applying Kay’s rule using these data, the maximum volume fractions of the essential oil in the blend with soyA biodiesel that meet this requirement EN 14214 are approximately 0.75 for orange oil and 0.37 for hydrogenated orange oil. This estimation assumes that excess volumes of mixing are negligible and that each component is itself a complex mixture. Although this is a simplification, it provides a valid approximation of the required blending ratios to meet the standard. In the literature, even lower volume fractions of orange oil and hydrogenated orange oil blended with biodiesel have been reported [12,15].

The viscosity of biofuels influences engine performance and operational reliability. Elevated viscosity can delay fuel flow, promote incomplete combustion, and accelerate wear of fuel pumps and injectors, thereby diminishing engine power output and overall efficiency. Conversely, excessively low viscosity may compromise fuel system lubrication, potentially leading to leakage, component degradation, and mechanical failure. According to the EN 14214 standard, biodiesel fuels should exhibit a kinematic viscosity within the range of 3.5–5.0 mm2/s at 313.15 K, whereas the ASTM D6751 specification defines a broader acceptable range of 1.9–6.0 mm2/s at 313.15 K. This standard is intended to optimise engine power, efficiency, and durability. The kinematic viscosity of the essential oils measured in this work is lower than the limit established by EN 14214. In Figure 8b, the kinematic viscosity limits prescribed by ASTM D6751 are compared with the measurements obtained in the present study and with the data for SoyA biodiesel. Only the 98% hydrogenated turpentine exhibits a kinematic viscosity within the ASTM D6751 range. The viscosity of SoyA biodiesel also conforms to this standard. Consequently, hydrogenated turpentine, either used independently or blended with SoyA biodiesel across the entire compositional range, complies with the kinematic viscosity requirements established by the ASTM D6751 specification. However, turpentine and hydrogenated orange oil do not comply with ASTM D6751 on their own, as their viscosities are too low (see Figure 8b). Therefore, they must be blended with biodiesel to achieve suitable fuel properties. To determine the appropriate proportion of each oil in the blend, the Grunberg–Nissan correlation can be applied. Assuming that biodiesel fuels and essential oils are non-associated liquids, the dynamic viscosity of the mixture can be estimated using the following equation:

where ρi and νi are the density and kinematic viscosity of the compound; ρm and νm are the kinematic viscosity of the mixture, and xi is the mole fraction. Assuming the mixture components are soyA biodiesel and turpentine, and that the target kinematic viscosity corresponds to the ASTM D6751 specification (1.9 mm2·s−1) with a density of 860 kg·m−3, we can estimate the composition as follows. The dynamic viscosity (ρi νi) is taken from our experimental data at 313.15 K, giving 1.57 mPa·s for turpentine, and from the literature for soyA biodiesel, which has a value of 3.74 mPa·s [34]. Using the above equation, the maximum mole fraction of turpentine in the mixture is approximately 0.95. Although this result is based on several simplifying assumptions, it provides an estimate of the upper limit for turpentine content. The literature used lower concentrations of turpentine in biodiesel or diesel blends to meet the ASTM D6751 viscosity requirements [13]. The same procedure has not been applied to hydrogenated orange oil, since we were not able to measure the viscosity data at 313.15 K. To summarise, the densities of turpentine and 98% hydrogenated turpentine fall within the range specified by EN 14214; however, none of the essential oils exhibit viscosity values that meet the lower limits established by EN 14214. The viscosity of hydrogenated turpentine, however, falls within the range specified by ASTM D6751, which does not include a density requirement. Therefore, hydrogenated turpentine could potentially be used as a standalone biofuel. Nevertheless, orange oil, turpentine, and hydrogenated compounds can meet the specifications of EN 14214 or ASTM D6751 when blended with biodiesel, due to biodiesel’s higher viscosity and density.

4. Conclusions

New density and viscosity data for turpentine, orange oil, hydrogenated turpentine, and hydrogenated orange oil were determined at atmospheric pressure over the temperature range of 293.15–373.15 K, with uncertainties below 0.05 kg·m−3 for density and 0.3 mPa·s for viscosity. The data agree well with the limited literature values and were successfully correlated as functions of temperature. Both properties decrease with increasing temperature for all compounds. Orange oil and turpentine show higher densities but lower viscosities than their hydrogenated counterparts due to differences in molecular structure and packing efficiency.

None of the pure essential oils investigated in this study satisfies the viscosity requirements established by the European standard EN 14214. However, hydrogenated turpentine complies with the viscosity specifications of the American standard ASTM D6751. Blending these bio-based compounds with conventional biodiesel could yield fuel mixtures that meet both EN 14214 and ASTM D6751 specifications, as the higher viscosity and density of biodiesel would compensate for the lower values exhibited by the essential oils. From a thermophysical property perspective, these results demonstrate that orange oil, turpentine, and their hydrogenated derivatives are viable candidates as biodiesel blend components for internal combustion engine applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S.-V.; Methodology, B.M.; Formal analysis, B.M. and Y.S.-V.; Investigation, B.M. and Y.S.-V.; Resources, Y.S.-V.; Data curation, B.M. and Y.S.-V.; Writing—original draft, Y.S.-V.; Writing—review & editing, Y.S.-V.; Supervision, Y.S.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank David Donoso from the Grupo de Combustibles y Motores, University of Castilla la Mancha, Spain for generously providing the turpentine and orange oils used in this study. The authors also thank Simon Neville and Sam Hutchinson for their technical support. Additionally, we gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the Royal Society (UK), including Research Grant 2023 (Project Ref. RGS\R1\231141, ProNTES), which provided the densimeter and viscometer used in this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- IEA. Global Energy Review 2025, IEA, Paris. Licence: CC BY 4.0. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-review-2025 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Demirbas, A. Progress and recent trends in biofuels. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2007, 33, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmudul, H.M.; Hagos, F.Y.; Mamat, R.; Adam, A.A.; Ishak, W.F.W.; Alenezi, R. Production, characterization and performance of biodiesel as an alternative fuel in diesel engines—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 72, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalingam, K.; Vellaiyan, S.; Venkatesan, E.P.; Khan, S.A.; Mahmoud, Z.; Saleel, C.A. Challenges and Opportunities of Low Viscous Biofuel—A Prospective Review. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 16545–16560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, D.; Bustamante, F.; Alarcón, E.; Donate, J.M.; Canoira, L.; Lapuerta, M. Improvements of Thermal and Thermochemical Properties of Rosin by Chemical Transformation for Its Use as Biofuel. Waste Biomass Valorization 2020, 11, 6383–6394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, A. By-product recovery and valorisation in the kraft industry: A review of current trends in the recovery and use of turpentine and tall oil derivatives. Biomass 1982, 2, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negro, V.; Mancini, G.; Ruggeri, B.; Fino, D. Citrus waste as feedstock for bio-based products recovery: Review on limonene case study and energy valorization. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 214, 806–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, R.; García, D.; Bustamante, F.; Alarcón, E.; Lapuerta, M. Oxyfunctionalized turpentine: Evaluation of properties as automotive fuel. Renew. Energy 2020, 162, 2210–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chivu, R.M.; Martins, J.; Popescu, F.; Ion, I.V.; Krisztina, U.; Fratita, M. The use of turpentine as additive for diesel oil. A review. J. Therm. Eng. 2025, 11, 880–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purushothaman, K.; Nagarajan, G. Performance, emission and combustion characteristics of a compression ignition engine operating on neat orange oil. Renew. Energy 2009, 34, 242–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purushothaman, K.; Nagarajan, G. Experimental investigation on a C.I. engine using orange oil and orange oil with DEE. Fuel 2009, 88, 1732–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.M.A.; Van, T.C.; Hossain, F.M.; Jafari, M.; Dowell, A.; Islam, M.A.; Nabi, M.N.; Marchese, A.J.; Tryner, J.; Rainey, T.; et al. Fuel properties and emission characteristics of essential oil blends in a compression ignition engine. Fuel 2019, 238, 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoso, D.; García, D.; Ballesteros, R.; Lapuerta, M.; Canoira, L. Hydrogenated or oxyfunctionalized turpentine: Options for automotive fuel components. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 18342–18350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donoso, D.; Ballesteros, R.; Bolonio, D.; García-Martínez, M.-J.; Lapuerta, M.; Canoira, L. Hydrogenated Turpentine: A Biobased Component for Jet Fuel. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 1465–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoso, D.; Bolonio, D.; Ballesteros, R.; Lapuerta, M.; Canoira, L. Hydrogenated orange oil: A waste derived drop-in biojet fuel. Renew. Energy 2022, 188, 1049–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heywood, J. Internal Combustion Engine Fundamentals 2E; McGraw Hill LLC: Columbus, OH, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, R.K.; Rehman, A.; Sarviya, R.M. Impact of alternative fuel properties on fuel spray behavior and atomization. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 1762–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Ma, J.; Dong, F.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Ma, G.; Zheng, Z.; Yao, M. Experimental investigation of the effects of diesel fuel properties on combustion and emissions on a multi-cylinder heavy-duty diesel engine. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 171, 1787–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, R. Introduction to Internal Combustion Engines; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- CEN. EN 14214:2012+A2:2019 - Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAME) for Use in Diesel Engines and Heating Applications—Requirements and Test Methods. 2012. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/0a2c5899-c226-479c-b277-5322cc71395d/en-14214-2012a2-2019 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Standard Specification for Biodiesel Fuel (B100) Blend Stock for Distillate Fuels. 2002. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/astm/2c940cfb-8fce-4ba2-a929-2ad8232f3d0c/astm-d6751-02 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Tesfa, B.; Mishra, R.; Gu, F.; Powles, N. Prediction models for density and viscosity of biodiesel and their effects on fuel supply system in CI engines. Renew. Energy 2010, 35, 2752–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortunatti-Montoya, M.; Hegel, P.E.; Pereda, S. Density and viscosity of orange peel oil saturated with pressurized CO2. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2024, 214, 106373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares Sousa, A.; Nieto de Castro, C.A. Density of α-pinene, Β-pinene, limonene, and essence of turpentine. Int. J. Thermophys. 1992, 13, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton Paar. Density Meters. Available online: https://www.anton-paar.com/uk-en/products/group/density-meter/ (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Wikipedia Contributors. Oscillating U-tube. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Oscillating_U-tube&oldid=979631440 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Gonzalez, M.A.; Tenorio, M.J.; Bismilla, A.Z.; D’Oliveira, E.J.; Costa Pereira, S.-C.; Sanchez-Vicente, Y. Molecular dynamics simulations and experimental measurements of density and viscosity of phase change material based on stearic acid with graphene nanoplatelets. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2025, 593, 114361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JCGM 100:2008; Evaluation of Measurement Data—Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement. Joint Committee for Guides in Metrology: Paris, France, 2008.

- Schroeder, J.A.; Penoncello, S.G.; Schroeder, J.S. A Fundamental Equation of State for Ethanol. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 2014, 43, 043102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmon, E.W.; Bell, I.H.; Huber, M.L.; McLinden, M.O. NIST Standard Reference Database 23: Reference Fluid Thermodynamic and Transport Properties-REFPROP, Version 10.0; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 17034:2016; General Requirements for the Competence of Reference Material Producers. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/29357.html (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- ISO/IEC 17025 for Laboratory Testing/Calibration. Available online: https://www.ukas.com/resources/resources/soas-17025/ (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Clará, R.A.; Marigliano, A.C.G.; Sólimo, H.N. Density, Viscosity, and Refractive Index in the Range (283.15 to 353.15) K and Vapor Pressure of α-Pinene, d-Limonene, (±)-Linalool, and Citral Over the Pressure Range 1.0 kPa Atmospheric Pressure. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2009, 54, 1087–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grozdanić, N.; Simić, Z.; Kijevčanin, M.; Radović, I. High Pressure Densities and Derived Thermodynamic Properties of Pure (1R)-(+)-α-Pinene, (1S)-(−)-β-Pinene, and Linalool: Experiment and Modeling. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2024, 69, 854–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, S.; Wang, C.; Guo, Y.; Fang, W. Density and Viscosity of the Ternary System Pinane + n-Dodecane + Methyl Laurate and Corresponding Binary Systems at T = 293.15–333.15 K. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2021, 66, 2706–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, E.N.D.C. The Viscosity of Liquids. Nature 1930, 125, 309–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francesconi, R.; Comelli, F.; Castellari, C. Excess molar enthalpies of binary mixtures containing phenetole+α-pinene or β-pinene in the range (288.15–313.15) K, and at atmospheric pressure: Application of the extended cell model of Prigogine. Thermochim. Acta 2000, 363, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratas, M.J.; Freitas, S.V.D.; Oliveira, M.B.; Monteiro, S.C.; Lima, Á.S.; Coutinho, J.A.P. Biodiesel Density: Experimental Measurements and Prediction Models. Energy Fuels 2011, 25, 2333–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, S.V.D.; Pratas, M.J.; Ceriani, R.; Lima, Á.S.; Coutinho, J.A.P. Evaluation of Predictive Models for the Viscosity of Biodiesel. Energy Fuels 2011, 25, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).