Abstract

Two-dimensional (2D) metal halide perovskites have attracted considerable interest for their markedly improved environmental stability and versatile compositional tunability compared to their three-dimensional (3D) counterparts. Nevertheless, the anisotropic charge transport caused by insulating organic spacers often leads to inefficient charge transport and limiting device performance. Precise control over crystallographic orientation, particularly achieving vertical alignment of the inorganic layers, is essential to facilitate out-of-plane charge transport and enhance device efficiency. This review systematically summarizes recent advances in understanding and controlling the crystallographic orientation of 2D perovskites, emphasizing manipulating strategies such as processing optimization, composition engineering, spacer design, solvent selection, and additive assistance to promote vertical alignment of inorganic layers and improve interlayer charge transport. We also discuss the influence of phase distribution, quantum well width, and crystal growth kinetics on device performance. Finally, we outline prevailing challenges and future opportunities for achieving the ideal microstructure and high-efficiency 2D perovskite solar cells.

1. Introduction

Over the past decade, metal halide perovskite solar cells (PSCs) have achieved tremendous progress in the field of photovoltaics, with their certified power conversion efficiency (PCE) soaring from 3.8% to 27.5% [1,2]. This remarkable improvement can be attributed to their excellent photoelectric properties, such as an adjustable band gap, a high absorption coefficient (≈105 cm−1) [3,4] and a long carrier diffusion length (>1 µm) [5]. These characteristics position single-junction metal halide PSCs as promising candidates for surpassing the efficiency limit of single-junction silicon solar cells [6]. Such achievements demonstrate the rapid development of metal halide PSCs and their gradually emerging commercial value [7].

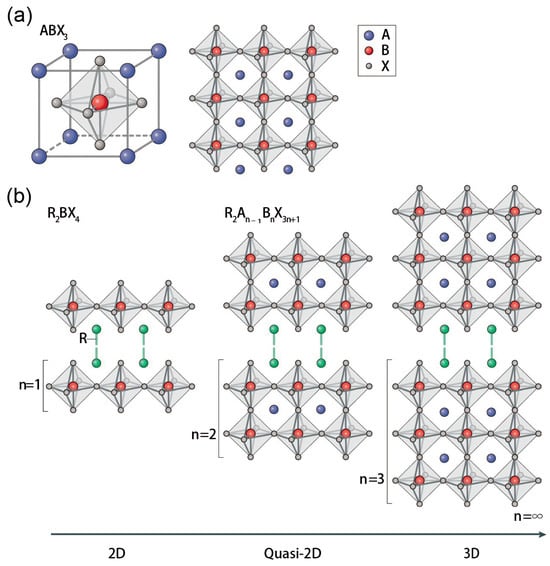

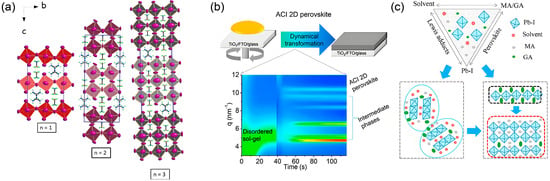

Three-dimensional metal halide PSCs have been the research focus of scientists because of their small band gap and low exciton binding energy [8,9,10]. These 3D perovskites typically adopt an ABX3 structure, where A represents an organic cation (for example, MA+, CH3NH3+; FA+, (HC(NH2)2+), Cs+, or Rb+; B is a metal cation, such as Pb2+ or Sn2+; and X is a halide (I−, Br−, F−, Cl−). Generally, 3D perovskites adopt a cubic structure composed of corner-sharing [BX6]4- octahedra, as shown in Figure 1a. In this framework, the A-site cation must be sufficiently small to occupy the interstitial voids within the lattice of corner-sharing [BX6]4− octahedra. However, a major limitation of 3D perovskites is their relatively poor environmental stability, which stems from their sensitivity to moisture, oxygen, and high temperatures [11,12]. This instability poses a fundamental challenge for practical applications. For instance, degradation associated with the α-to-δ phase transition is frequently observed in 3D perovskite devices under ambient conditions [13]. This phase transition is less frequently discussed in MA-based perovskites because the α-phase has a low formation energy and is highly stable. In contrast, FA-based perovskites have been more extensively studied in this context because they exhibit a reversible phase transition, forming the photoactive α-phase above ~150 °C and converting to a non-perovskite δ-phase below this temperature. These stability issues have significantly hindered the commercialization of 3D PSCs.

2D perovskites have recently attracted intense interest due to their superior environmental stability [14,15,16]. These low-dimensional perovskites generally adopt the structural formula of R2A(n−1)BnX(3n+1), where R represents a large-sized alkyl ammonium cation, such as n-butylamine (BA) [15,16,17] or phenethylamine (PEA) [18], which acts as a spacer between inorganic sheets. The value of n corresponds to the number of inorganic layers. Structurally, these layered compounds are formed by inserting bulky organic cation spacers into frameworks of corner-sharing [BX6] octahedra [19], creating inorganic layers that are confined between organic barriers. This configuration results in a multiple quantum well structure, where the inorganic layers act as the wells and the organic dielectric layers serve as barriers, as depicted in Figure 1. Perovskites with n values between 1 and 4 are typically defined as 2D perovskites, while those with n values range from 5 to ꝏ are referred to as quasi-2D perovskites.

The enhanced stability of 2D perovskites is largely attributed to their bulkier, hydrophobic organic molecules and the associated van der Waals (vdW) interactions [20,21]. Specifically, compared to their 3D counterparts, the introduction of large organic spacer cations not only improves moisture and oxygen resistance but also effectively suppresses the migration of small organic cations and halide ions within the lattice, thereby further boosting structural stability. Moreover, 2D perovskites exhibit superior film-forming properties, enabling the fabrication of high-quality thin films more readily than 3D perovskites. In particular, while typical 3D perovskite systems often require anti-solvent assistance to achieve desirable film morphology [22,23], high-quality 2D perovskite films can be fabricated without such complex processing. Owing to these combined advantages in stability and processability, 2D perovskites represent a more promising pathway toward commercialization.

Figure 1.

Structure diagrams of (a) 3D and (b) 2D perovskite. The 2D perovskite structure is formed by inserting large-sized organic cation spacers (R) between the inorganic sheets of the corner-sharing [BX6]4− octahedron. R is a large-sized organic cation spacer, the green lines between is the vdW force, A is an organic cation, B is a metal cation, X is a halide. Reprinted from Ref. [24], Copyright (2019) Springer Nature.

Although 2D perovskites exhibit superior device stability, their PCEs remain considerably lower than those of 3D perovskites. This limitation is primarily attributed to the intrinsic insulating nature of the organic spacer layers in 2D perovskites, which hinder vertical charge carrier transport and thus significantly depress device performance [19,25]. Thermodynamically, the [BX6]4− inorganic octahedral units tend to adopt a preferential parallel orientation to the substrate. This structural anisotropy, combined with the presence of insulating large-sized organic cations, facilitates in-plane charge conduction but severely impedes interlayer transport [26]. The resulting charge recombination leads to significant losses in final device performance, thereby curtailing the progress of 2D PSCs.

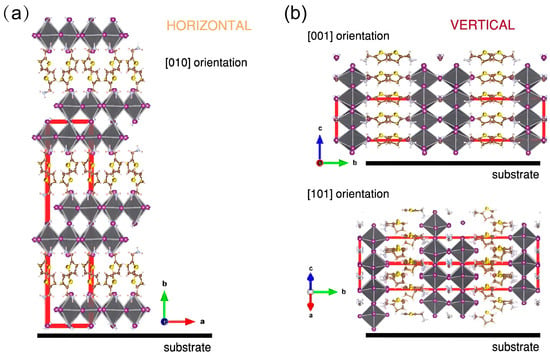

A key requirement for high-performance 2D perovskite optoelectronic devices is to align the 2D perovskite layer perpendicular to the substrate. As depicted in Figure 2, this specific orientation yields superior crystallinity and uniform thin films, which collectively establish continuous charge-transport channels [27]. These channels enable highly mobile photogenerated carriers to traverse the 2D slabs between device electrodes efficiently, without obstruction from the intrinsic insulating spacer layers. Furthermore, compared to horizontally or randomly oriented films, vertically aligned crystallites exhibit improved film coverage, enlarged grain size, and a reduced density of grain boundaries [28]. Since defects at grain boundaries and within the bulk are major sources of nonradiative recombination that severely shorten carrier lifetime [29], this optimized microstructure is crucial for enhancing device performance. At present, numerous research efforts are now dedicated to controlling crystal growth orientation and promoting vertical alignment, with the goal of further boosting the PCE of the 2D and quasi-2D PSCs.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagrams illustrating the orientation of 2D perovskite films. (a) Horizontally oriented structure, where the inorganic layers align parallel to the substrate. (b) Vertically oriented structure, achieved through the out-of-plane alignment of the inorganic layers. Reprinted from Ref. [27], Copyright (2024) Springer Nature.

Here, we summarize and discuss the principles underlying the vertically oriented growth of 2D perovskite films from both thermodynamic and kinetic perspectives, covering the mechanisms of nucleation and crystal growth. We also provide a comprehensive overview of various fabrication strategies, including the hot-casting method [15,30], antisolvent application [31,32,33], vapor treatment [34,35], solvent engineering [36,37], additive assistance [38,39,40] and organic cation spacers modulation [41,42,43,44]. Furthermore, the correlation between preferential crystal orientation and the resulting photoelectric properties of the films is examined. Notably, beyond a mere compilation of literature, we offer our own insights into the control of crystal orientation, informed by our previous research in this field.

2. Formation Process of Preferential Orientation

2D perovskites exhibit a unique ability to self-assemble into high-quality, highly oriented films with minimal grain boundaries, a characteristic rooted in their layered nature and distinct from their 3D counterparts. These crystalline films can develop with random, parallel, or perpendicular orientation relative to the substrate [45,46]. While parallel orientation benefits in-plane carrier transport in devices like photodiodes [47,48,49], it impedes vertical charge transport across the sandwiched structure of PSCs due to the insulating organic spacers. Consequently, achieving a vertical crystallographic orientation is critical for facilitating efficient charge transfer through the conductive inorganic layers. Understanding and controlling the crystal growth to realize this preferred orientation is thus vital for advancing 2D PSCs. This review delves into the mechanisms behind vertical orientation from combined thermodynamic and kinetic perspectives, offering profound insights into the nucleation and crystal growth processes to guide future development.

2.1. Preferential Oriented Nucleation

A fundamental understanding of the origins and driving forces behind preferential orientation is essential for its rational control in 2D perovskites. The crystal growth process, governed by the interplay of thermodynamics and kinetics, primarily consists of two stages: nucleation, which is the formation of initial crystal seeds, and subsequent crystal growth [50]. Reaching a state of supersaturation is the fundamental prerequisite, providing the thermodynamic driving force for crystallization.

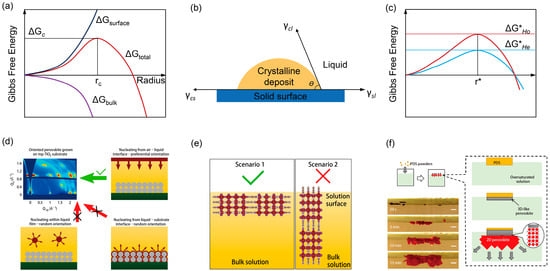

Thermodynamically, the formation of a crystal nucleus from a supersaturated solution is described by the change in Gibbs free energy, ΔG. For homogeneous nucleation within the bulk solution (Figure 3a), ΔGtotal is the sum of the unfavorable surface free energy and the favorable bulk free energy decrease [51].

where r is the nucleus radius, γ is the interfacial surface energy, and ΔGbulk is the free energy change per unit volume, which is negative and related to the supersaturation ratio S (S = C/Cs, where C is the concentration and Cs is the equilibrium solubility) by:

Here, kB is Boltzmann’s constant, T is the temperature, and Vm is the molar volume. As shown in Figure 3a, ΔGtotal first increases with radius r and then decreases. The critical nucleation barrier, ΔGc, and the critical radius, rc, occur at the maximum of ΔGtotal:

Nuclei smaller than rc dissolve, while those larger are stable and grow. The strong inverse dependence of on lnS highlights the crucial role of supersaturation.

For heterogeneous nucleation at an interface (Figure 3b,c), the presence of a substrate reduces the nucleation barrier. The energy barrier is modified by a geometric factor f(θ) that depends on the contact angle θ between the nucleus and the substrate:

For 0° < θ < 180°, f(θ) < 1, making heterogeneous nucleation thermodynamically favored over homogeneous nucleation. The liquid–air interface, with its specific wettability and surface energy, provides such a preferential site with a lowered energy barrier.

Kinetically, the nucleation rate J follows an Arrhenius-type relationship with the nucleation barrier:

where A is a pre-exponential factor related to molecular collision frequency. This equation quantitatively shows that even a small reduction in ΔGc at an interface leads to an exponential increase in the nucleation rate at that location, dominating the nucleation process.

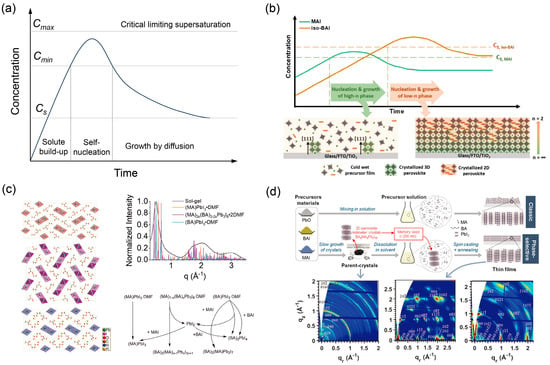

Once stable nuclei form, crystal growth proceeds. The growth rate can be limited either by monomer diffusion to the surface or by the surface integration reaction. The surface-reaction controlled growth rate often depends on the supersaturation at the interface. As illustrated in Figure 4a, in many crystallization processes, the interplay between nucleation and growth is elegantly captured by the LaMer model [52]. This model delineates three stages: (I) a gradual increase in monomer concentration (C) below the minimum nucleation concentration (Cmin); (II) a short “burst nucleation” event when C exceeds the critical supersaturation concentration (Cs), rapidly depleting monomers; and (III) a focused growth stage where C falls below Cs, nucleation ceases, and existing particles grow. The temporal separation of nucleation and growth stages is key to achieving monodisperse particles and, in the context of thin films, large, oriented grains.

Figure 3.

(a) Illustration of the free energy change ΔGtotal with particle radius during homogeneous nucleation. (b) Illustration of the contact angle (θ) for heterogeneous nucleation. (c) Free energy plot for homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation. (d) Possible scenarios for different nucleation sites: air-liquid interface, within bulk liquid and substrate–liquid interface. (e) Two scenarios of crystallographic orientation at the liquid–air interface. Reprinted from Ref. [53], Copyright (2018) Springer Nature. (f) Illustration and optical photos of the crystal nucleation at the liquid surface of the supersaturated precursor solution. Reprinted from Ref. [54], Copyright (2020) Springer Nature.

Classical nucleation theory, governed by thermodynamic and kinetic principles, primarily elucidates the location and rate of nucleus formation. In perovskite systems, heterogeneous nucleation is generally favored over its homogeneous counterpart due to a lower energy barrier. However, the theory itself does not inherently bridge the connection between the site of nucleation and the eventual crystallographic orientation of the film. While supersaturation serves as the fundamental driving force for nucleation and growth, the specific mechanism through which it directs the formation of a preferentially oriented crystal ensemble remains unclear.

As illustrated in Figure 3d,e, Chen et al. provide a critical insight by demonstrating that nucleation occurring specifically at the liquid–air interface can lead to highly oriented films [53]. Their in situ characterization revealed the formation of a vertically oriented “top crust” at the solution surface, while the bulk beneath remained uncrystallized. This phenomenon indicates that the anisotropic environment of the liquid–air interface can promote the formation of nuclei with a specific orientation. The proposed model in Figure 3e suggests that this configuration, which allows the hydrophobic organic spacers to remain immersed in the solution, is energetically favorable, thereby defining the orientation for subsequent crystal growth.

Based on the observed phenomenon of interface-mediated orientation, Yuan et al. achieved a mechanistic breakthrough by precisely identifying the structure of the critical nuclei involved [54]. This work revealed that the primary nuclei forming at the forefront are not the layered perovskites themselves, but “3D-like” perovskite phases. They demonstrated that the layered perovskite does not nucleate independently; instead, its nucleation is templated by the preformed, crystallographically defined “3D-like” nuclei. The lattice matching between this 3D-like template and the incipient 2D structure dictates the orientation of the layered perovskite from the very moment of its nucleation.

In summary, Chen et al. [53] identified the liquid–air interface as a critical location for oriented nucleation, while Yuan et al. [54] uncovered the essential structural identity of the nuclei at that location, specifically the 3D-like templates, and introduced a general chemical approach using AX additives to enforce this templated nucleation pathway. Collectively, these works shift the focus from nucleation sites to the paramount importance of the nature and crystallographic character of the initial nucleus.

Figure 4.

(a) LaMer model for the nucleation and growth of perovskite thin films. Cs is the supersaturation concentration of the precursor solution. Cmin is the minimum concentration for nucleation. (b) 2D perovskite nuclei with preferential orientation evolve at substrate–liquid interface. Reprinted from Ref. [55], Copyright (2020) American Chemical Society. (c) Origin of 2D perovskite nuclei from solvent intermediates ((MA)PbI3·DMF, (MA)2x(BA)2₍1−x₎Pb3I8·2DMF, (BA)PbI3·DMF) and their transformation pathways into 2D perovskite nuclei upon thermal annealing in the presence of sufficient organic ammonium salts (BAI/MAI) Reprinted from Ref. [56], Copyright (2020) Wiley. (d) Schematic diagrams and Grazing-Incidence Wide-Angle X-Ray Scattering (GIWAXS) patterns comparing nucleation via conventional solvent-intermediate conversion into 2D seeds vs. pre-synthesized BA2MA2Pb3I10 seeds, and their resulting film orientation. The * identify the n = 4 and n = 2 impurity phases. Reprinted from Ref. [57], Copyright (2021) Wiley.

While Chen and Yuan et al. highlighted the liquid–air interface [53,54], Jang et al. demonstrated that the substrate-liquid interface is an equally potent [55], if not more critical, platform for generating such oriented templates. Their key contribution lies in elucidating how the kinetics of nucleation can be manipulated to favor the formation of the desired 3D-like oriented nuclei at this buried interface. By employing a cold antisolvent bath, they deliberately retarded the crystallization process. This kinetic control creates a temporal window where the less soluble small organic cations preferentially reach supersaturation and nucleate at the substrate, forming the crucial 3D-like nuclei with a definitive (111) out-of-plane orientation. The subsequent, slower incorporation of the bulky spacer cations then builds the 2D structure upon this pre-oriented foundation. Thus, this work provides a dynamic, process-oriented complement to the chemical templating strategy of Yuan et al., demonstrating that precise kinetic control is pivotal in steering the oriented growth of the initial nuclei [54]. This conclusively shows that the vertical orientation of the final film is ultimately determined by the formation of highly oriented nuclei at the initial stage.

The origin and nature of these critical nuclei are further elucidated in recent studies. As depicted in Figure 4c, the nuclei of 2D perovskites can originate from dimethylformamide (DMF) intermediate complexes, such as (MA)PbI3·DMF, (MA)2x(BA)2(1−x)Pb3I8·2DMF, and (BA)PbI3·DMF [58]. These intermediates, which are formed during the sol–gel stage of film processing, can directly transform into 2D perovskite nuclei upon thermal annealing, provided sufficient organic ammonium salts are present to complete the conversion and avoid non-perovskite byproducts like PbI2. Complementing this, Figure 4d provides a striking comparison between two nucleation sources: conventional nucleation derived from the stochastic conversion of these solvent intermediates versus the use of pre-synthesized, phase-pure BA2MA3Pb3I10 “memory seeds” [57]. The GIWAXS patterns and schematics clearly demonstrate that films grown from pre-formed seeds exhibit a dramatically enhanced out-of-plane orientation compared to those formed via the conventional route. This collective evidence underscores that both the source and inherent structure of the crystalline nuclei, along with their nucleation site, critically govern the crystallographic orientation of the final film.

Based on the analysis presented above, a clear conclusion emerges: precise control over the initial nuclei, encompassing their location, chemical origin, and inherent structure, serves as the prerequisite for achieving highly oriented 2D perovskite films. This signifies an evolution in the research paradigm, shifting from exploring the site of nucleation to the precise design and regulation of the nucleating entity itself.

The physicochemical foundation for inducing crystal orientation by manipulating the nucleation process has thus been established. This logically leads to a more proactive and generalizable strategy: templated directional crystallization. By employing built-in or external templates to actively guide the entire process from nucleation to growth, precise control over film orientation and phase purity can be achieved, paving a new avenue for developing next generation, high-performance 2D perovskite optoelectronic devices.

2.2. Template-Guided Vertical Growth

Building upon the understanding of nucleation mechanisms, the subsequent crystal growth, particularly the attainment of vertically oriented perovskite films, is fundamentally governed by a template-guided vertical growth mechanism. This process relying on the formation of well-defined structural templates that dictate the crystallographic orientation throughout the film.

Crystal growth theory posits that the kinetic pathway of crystal growth is often driven and sustained by supersaturation. Figure 5b schematizes a supersaturation-driven growth mechanism where controlled solvent evaporation builds supersaturation at the interface [59]. This thermodynamic driving force is consumed by crystal growth through a two-step process: solute diffusion to the interface followed by surface reaction. When this kinetic pathway is coupled with a structural template, it ensures that the incoming material is incorporated in a specific orientation, reinforcing the vertical growth mode.

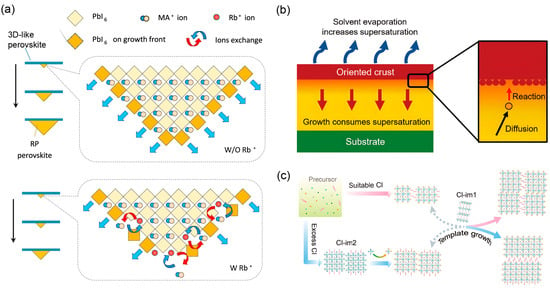

Figure 5.

(a) Schematic illustration of Rb+ ions retarding crystal growth through surface binding, thereby promoting vertical crystal orientation. Reprinted from Ref. [60], Copyright (2020) Wiley. (b) Supersaturation-driven growth mechanism, where solvent evaporation builds supersaturation that is consumed via solute diffusion to the interface followed by surface reaction. Reprinted from Ref. [59], Copyright (2019) American Chemical Society. (c) Two Cl-related intermediates serve as templates directing the orientational growth of the 2D perovskite films. Reprinted from Ref. [61], Copyright (2022) American Chemical Society.

Furthermore, the evolution of crystal morphology is determined by the relative growth rates of different crystallographic faces, which can be selectively modulated by external directors. In the context of 2D perovskites, the introduction of specific additives or the control of intermediate phases can create such a directing environment. As illustrated in Figure 5a, the incorporation of Rb+ ions serve as a powerful template [60]. These ions adsorb onto specific crystal surfaces, retarding their growth kinetics. This selective retardation favors the rapid vertical growth of perovskite crystals along the (111) direction, effectively guiding the overall film orientation from its earliest stages. Most significantly, the critical role of chemically derived intermediates as inherent templates has been clearly demonstrated. As revealed in Figure 5c, two distinct Cl-related intermediates serve as structural templates that directly direct the orientational growth of the 2D perovskite films [61]. These coordinated intermediates, with their specific chemical composition and pre-organized structure, act as internal templates that steer the crystallization pathway toward a uniformly oriented morphology, effectively suppressing the formation of randomly oriented grains.

In conclusion, the vertical growth of 2D perovskite films is not a spontaneous outcome but a meticulously guided process. It is orchestrated by structural templates, which can be exogenous additives like Rb+, or chmically derived intermediate phases such as the Cl-related complexes. These templates operate within a kinetic framework defined by supersaturation and interfacial reactions, selectively promoting growth along the desired out-of-plane direction. This theoretical framework of template-guided vertical growth underscores that precise control over both the template nature and the crystallization kinetics is paramount for achieving highly oriented perovskite films for high-performance 2D PSCs.

3. Formation Methods of Vertical Orientation

The crystallographic orientation of 2D perovskites is critically important to the performance of their resulting photovoltaic devices. Considerable research efforts have therefore been dedicated to achieving precise control over preferential orientation. As a rapidly evolving field, the underlying mechanisms and optimal methodologies are still under active investigation. Guided by the emerging understanding of these formation mechanisms, targeted strategies spanning film fabrication techniques, precursor composition, solvent engineering, and additive assistance can be custom designed. These approaches collectively guide the crystallographic orientation by controlling key factors such as solution supersaturation and ion coordination.

3.1. Film Processing Technologies

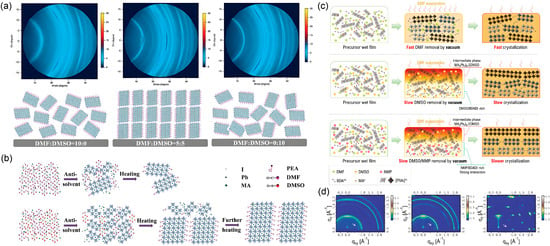

Conventional one-step solution processing often yields 2D perovskite films with random crystal orientation, resulting in unsatisfactory device performance. To address this limitation, several enhanced one-step strategies have been developed, notably the hot-casting method [15,30,62], antisolvent application [31,32,33] and solvent vapor-assisted (SVA) process [34,35].

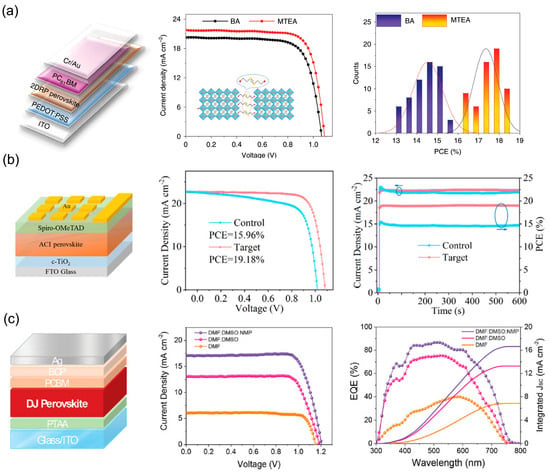

The hot-casting technique is a refined one-step solution process for fabricating high-quality perovskite films. As schematically shown in Figure 5a, the precursor solution is dispensed onto a preheated substrate and subsequently spin-coated. The applied thermal energy induces instantaneous solvent evaporation, visually marked by the rapid darkening of the wet film. This rapid color change signifies the fast formation of the perovskite phase. The elevated temperature increases precursor solubility, leading to a lower supersaturation level upon cooling. This condition suppresses random nucleation while accelerating crystal growth, thereby promoting the formation of large, oriented crystalline domains in the final film.

In conventional spin-coating processes conducted at room temperature, the precursor diffusion rate is relatively low. The isotropic environment in solution promotes uniform nucleation but results in randomly oriented crystal growth. At the same time, elevated temperatures may adversely affect the intrinsic properties and stability of the material. Moreover, high temperature accelerates solvent evaporation, leading to a rapid increase in supersaturation. Once this supersaturation surpasses a critical threshold, it triggers excessive nucleation, which disrupts ordered crystal growth and diminishes the degree of preferential orientation. Therefore, precise temperature control and judicious selection of perovskite precursor materials are of great importance. Tsai et al. successfully prepared smooth, highly covered thin films of (BA)2(MA)3Pb4I13 (n = 4) by precisely controlling stoichiometry and employing a hot-casting method [15]. As illustrated in Figure 6b, as the hot-casting temperature increases, the film color transitions from yellow to brown, and finally to a dark black film at the preheating temperature of 150 °C, indicating progressive crystallization. Unlike the randomly oriented perovskite films typically obtained by room temperature spin coating, the hot casting method promotes rapid crystallization at elevated temperatures, followed by further growth during annealing, yielding perovskite films with large grain size and strong crystallinity.

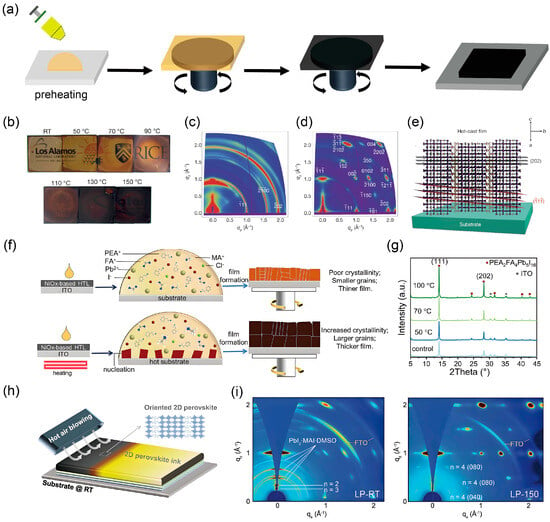

Figure 6.

Fabrication strategy and structural characterization of highly oriented 2D perovskite films via thermal-assisted processes. (a) Schematic illustration of the hot-casting process. (b) Optical images of 2D perovskite films fabricated at temperatures ranging from room temperature (RT) to 150 °C. GIWAXS patterns of the perovskite films prepared by (c) room-temperature casting and (d) hot-casting. (e) Schematic representation of the (101) orientation, along with the (1) and (202) planes of the hot-casting perovskite. Reprinted from Ref. [15], Copyright (2016) Springer Nature. (f) Schematic diagram illustrating the formation of (PEA)2FA4Pb5I16 perovskite films via hot-casting. (g) XRD patterns of (PEA)2FA4Pb5I16 films fabricated at temperatures from RT to 100 °C. Reprinted from Ref. [30], Copyright (2025) Wiley. (h) Schematic illustration of the hot-air-assisted blade-coating process. (i) GI-XRD patterns of 2D perovskite films prepared with RT air-assisted and 150 °C air-assisted. Reprinted from Ref. [62], Copyright (2023) Wiley.

Structural characterization further highlights the benefits of hot casting. GIWAXS patterns reveal that the room temperature cast film (Figure 6c) exhibits a largely isotropic polycrystalline structure with random orientation, whereas the hot cast film (Figure 6d) shows distinct diffraction spots, indicating enhanced out-of-plane orientation. Figure 6e schematically illustrates the preferential growth along the (101) orientation, together with the (202) and other planes in hot cast perovskite crystals, which facilitates vertical charge transport.

Similarly, in the study by Wu et al. on (PEA)2FA4Pb5I16 perovskite, thermal regulation via substrate preheating was employed [30]. As depicted in Figure 6f, when the perovskite precursor solution contacts the preheated substrate, heterogeneous nucleation preferentially occurs at the thermal interface, serving as seeds for subsequent growth during spin coating and annealing. This results in a thicker, more crystalline, and preferentially oriented film. XRD patterns (Figure 6g) confirm that as the substrate temperature increases from room temperature to 100 °C, the diffraction peak intensities strengthen, indicating improved crystallinity and a higher degree of orientation particularly along the (202) plane, which favors vertical carrier transport.

Another advanced method, hot air assisted blade coating, has also been demonstrated to enhance the orientation of 2D perovskite films [62]. As sketched in Figure 6h, this technique uses heated air flow during deposition to promote rapid solvent removal and directional crystal growth. GI-XRD patterns in Figure 6i reveal that compared to the RT air assisted film, the 150 °C hot air-assisted film exhibits sharper and more intense diffraction peaks, suggesting superior crystallographic alignment and reduced defect density.

In summary, thermal regulation strategies, whether through hot casting, substrate preheating, or hot air assistance, effectively promote rapid nucleation and directional crystal growth by modulating precursor diffusion and solvent evaporation dynamics. These methods consistently yield 2D perovskite films with larger grains, higher crystallinity, and preferred orientation, which are crucial for efficient charge transport and high-performance optoelectronic devices.

Antisolvent treatment is widely employed in high-performance three-dimensional PSCs [63,64]. This technique has also proven highly effective in achieving vertically oriented 2D perovskite films. The process entails the rapid introduction of a poor solvent during spin-coating, prompting immediate solvent extraction and triggering fast nucleation. In the study by Dong et al., a precursor-assisted crystal growth (PACG) technique was developed using isopropanol (IPA) as the antisolvent medium [31]. As illustrated in Figure 7a, a dilute IPA solution containing ThFAI, MAI, and MACI in the same ratio as the precursor was applied as the antisolvent during spin-coating. This method promoted heterogeneous nucleation and vertical growth, yielding a compact, large-grained, and highly oriented (ThFA)2MA2Pb3I10 film, in stark contrast to the rough and randomly oriented morphology obtained with pure IPA antisolvent. Structural characterization underscores the advantages of the PACG method. XRD and GIWAXS patterns in Figure 7b reveal that the PACG-processed film exhibits enhanced diffraction peak intensities and a higher (202)/(111) intensity ratio, indicating improved crystallinity and preferential vertical orientation of the inorganic slabs. The GIWAXS pattern shows sharp Bragg spots, confirming a highly oriented structure, whereas the control film displays polycrystalline rings indicative of random orientation.

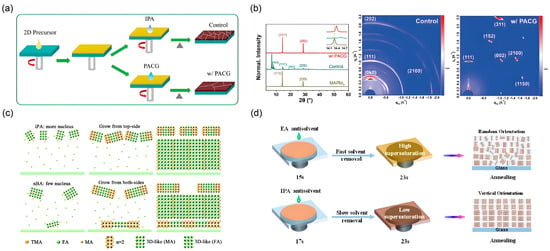

Figure 7.

Fabrication strategy and structural characterization of highly oriented 2D perovskite films via antisolvent process. (a) Schematic diagram of the fabrication process for 2D perovskite films processed with IPA and PACG antisolvents. (b) XRD patterns and corresponding GIWAXS images of the films processed with IPA and PACG antisolvents. Reprinted from Ref. [31], Copyright (2020) Wiley. (c) Schematic diagrams of the 2D perovskite films formation process of IPA and nBA antisolvent. Reprinted from Ref. [32], Copyright (2022) Royal Society of Chemistry. (d) Crystallization mechanism illustrating randomly oriented and vertically oriented perovskite films induced by EA and IPA antisolvents, respectively. Reprinted from Ref. [33], Copyright (2023) Elsevier.

Liang et al. systematically investigated the role of different alcoholic antisolvents, comparing IPA and n-butanol (nBA) [32]. The schematic in Figure 7c depicts their distinct film formation processes. The IPA-processed film forms a unique reverse gradient quantum well structure, where low-n-value phases concentrate at the top surface, while high-n-value phases dominate the interior. This configuration facilitates directional charge transport. In contrast, the nBA-processed film exhibits a sandwich-like distribution of quantum wells, with low-n phases present at both top and bottom interfaces, which disrupts carrier transport and leads to inferior device performance.

Furthermore, the crystallization mechanism is highly dependent on the antisolvent’s properties. As illustrated in Figure 7d, the strong polarity and specific solubility of IPA promote rapid nucleation of low-n phases at the film surface, guiding the subsequent growth of vertically aligned perovskite layers. In contrast, antisolvents like ethyl acetate (EA) lead to uncontrolled nucleation and random crystal orientation, resulting in disordered microstructures and inefficient charge transport [33].

In summary, antisolvent strategies, whether through sophisticated methods like PACG or careful selection of solvent type such as IPA, effectively manipulate crystallization kinetics by inducing rapid nucleation and modulating phase distribution. These approaches can produce 2D perovskite films with enhanced crystallinity, preferred vertical orientation, and controlled quantum well structures, which are paramount for achieving efficient charge transport and high performance in optoelectronic devices.

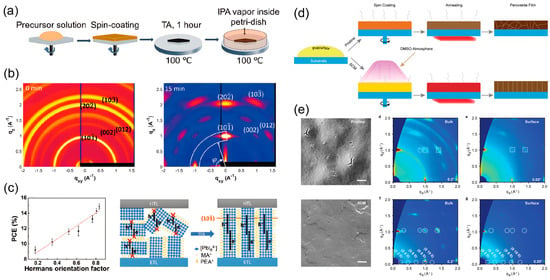

Despite their sophistication, techniques such as hot-casting and antisolvent processing are susceptible to variations introduced by manual operation, which greatly limits the reproducible fabrication of highly oriented perovskite films. To address this limitation, SVA post-treatment methods have emerged as promising alternatives. As illustrated in Figure 8a, Zhao et al. developed a post-deposition SVA strategy in which the as-deposited film is exposed to solvent vapors such as isopropanol [34]. This treatment plasticizes the perovskite layer, facilitating substantial grain reorganization and crystal reorientation. The corresponding GIWAXS patterns (Figure 8b) and structural evolution diagrams (Figure 8c) of (PEA)2(MA)4Pb5I16 perovskite films clearly demonstrate the transition from a randomly oriented to a vertically aligned morphology after SVA, thereby significantly enhancing charge transport. Building on this, Chen et al. proposed an in situ surface crystallization modulation (SCM) approach by maintaining a controlled dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) solvent vapor atmosphere during spin-coating (Figure 8d) [35]. This method promotes the direct formation of a stoichiometric, oriented 2D perovskite layer at the vapor-liquid interface, which subsequently templates the growth of the bulk film. As shown in Figure 8e, the SCM-treated film exhibits highly vertical orientation and large grains, with corresponding 2D GI-XRD patterns confirming the preferential alignment of both 2D and 3D-like phases. These solvent vapor-assisted strategies, whether applied post-deposition or in situ, effectively decouple the crystallization process from operator-dependent variables, enabling more reproducible fabrication of vertically oriented 2D perovskite films with enhanced charge transport properties.

Figure 8.

Fabrication strategy and structural characterization of highly oriented 2D perovskite films via the solvent vapor-assisted (SVA) process. (a) Schematic illustration of the post-deposition SVA treatment process for 2D perovskite films. (b) GIWAXS patterns and (c) corresponding schematics of structural evolution for (PEA)2(MA)4Pb5I16 perovskite films before and after SVA treatment. Reprinted from Ref. [34], Copyright (2020) American Chemical Society. (d) Schematic illustration of the film formation process via DMSO solvent vapor annealing. (e) SEM images of the as-deposited (left) and surface-crystallization modulated (right) films (scale bars: 1 μm), with the corresponding 2D GI-XRD patterns from the bulk and surface regions. Dashed squares and circles mark the diffraction signals originated from the 3D-like and 2D perovskites, respectively. Reprinted from Ref. [35], Copyright (2024) Wiley.

3.2. Composition Manipulating

3.2.1. Management of n Value

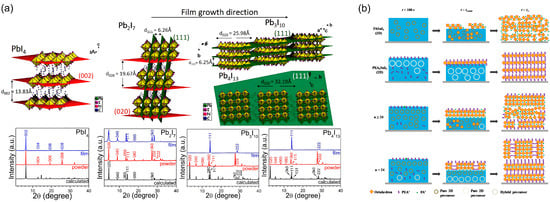

The n-value, which represents the number of inorganic layer sheets in the perovskite quantum well, can be tuned by adjusting the stoichiometric ratio of the precursor components. Since quasi-2D perovskites exhibit a multi-quantum well structure, the distribution of different n-value phases in the film is inherently accompanied by inconsistent orientation [16,65]. Taking (BA)2(MA)n−1PbnI3n+1 as an example, the transition from 3D to 2D structure involves the partial substitution of methylammonium ions by larger organic cations. When n = 1, MA is completely replaced by BA, resulting in a fully parallel crystal orientation relative to the substrate, and the bandgap shifts from 1.52 eV for MAPbI3 (n = ∞) to 2.24 eV for BA2PbI4 (n = 1). Cao et al. demonstrated that high-quality, smooth, and fully covered films with vertical crystal growth can be achieved for n = 3 and 4 phases via a one-step spin-coating method [16]. While 2D halide perovskites generally favor in-plane growth of inorganic layers on planar substrates [66], the orientation behavior varies with n. For n = 2, the coexistence of (111), (202), and (0k0) diffraction peaks indicates mixed vertical and parallel orientations. In contrast, only (111) and (202) reflections are present for n = 3 and 4, indicating highly preferential out-of-plane orientation. This growth behavior can be attributed to the competitive interaction between the large BA cations, which restrict in-plane growth, and the small MA ions, which promote out-of-plane expansion, as illustrated in Figure 9a. Therefore, the orientation of (BA)2(MA)n−1PbnI3n+1 perovskite films is strongly governed by the value of n.

Figure 9.

(a) Schematic illustrations of the crystal structures for 2D perovskites with n values from 1 to 4, indicating the increasing propensity for vertical orientation with higher n values. Reprinted from Ref. [16], Copyright (2015) American Chemical Society. (b) Proposed crystal growth mechanism and resultant phase distribution in 2D/3D hybrid Sn-perovskite films during spin-coating. Crystallization initiates at the air-solution interface, forming an oriented 3D-like top layer, while a quasi-2D phase (n = 2) with horizontally aligned inorganic slabs forms near the substrate due to the coordination of PEA+ cations after FA+ consumption. Reprinted from Ref. [65], Copyright (2020) Wiley.

While most studies focus on Pb-based perovskites, the crystallization and orientation mechanisms of Sn-based counterparts remain less understood. Dong et al. systematically elucidated the stages and mechanisms of crystal formation during the film processing of tin-based perovskites, providing key insights into orientation control [65]. The crystallization of Sn-based perovskites differs fundamentally from that of Pb-based analogs, primarily due to the absence of intermediate ordered phases; the disordered precursor transforms directly into the crystalline state. As illustrated in Figure 9b, in pure 3D FASnI3 precursor solutions, nucleation occurs within the bulk, leading to isotropic growth and randomly oriented crystallites. In contrast, introducing low-dimensional components promotes a highly aligned growth mode, with inorganic slabs orienting parallel to the substrate. The n value strongly influences crystallization behavior: PEA+ cations preferentially coordinate at crystal surfaces, guiding the (100) planes to align parallel to the substrate. Owing to the higher fraction of FA+ relative to PEA+ in the precursor, the 3D phase reaches supersaturation first, forming a highly oriented 3D-like perovskite layer at the top. As FA+ is consumed, PEA+ dominates crystallization in the bottom region, forming a quasi-2D phase (n = 2) with horizontally aligned inorganic layers and vertically oriented organic spacers. Therefore, incorporating low-dimensional components effectively mitigates the disordered orientation typical of pure 3D Sn-perovskites, promoting structural alignment that is inversely influenced by dimensionality. Achieving an optimal balance between the high charge transport efficiency of 3D motifs and the superior environmental stability of 2D structures through precise dimensionality control remains a central challenge in advancing Sn-based 2D perovskite photovoltaics.

3.2.2. Selection and Design of Organic Spacers

(1). 2D Ruddlesden–Popper-phase perovskite

Molecular tailoring of organic cation spacers has been employed to promote preferential vertical orientation in 2D Ruddlesden-Popper (RP) perovskites, as the relative rotation and tilting of Pb–I octahedral slabs are governed by the tunable chemical structure of these spacers. Organic spacers influence crystallization by modulating growth reaction kinetics [59]. To date, BA+ and PEA+ cations remain the most widely used spacers in quasi-2D perovskites. Solar cells incorporating these spacers achieve high efficiency and long-term operational stability, owing to the preferred crystal orientation and excellent film morphology of the resulting 2D RP perovskite layers [18,41].

Simply tuning the ratio of BA+ to MA+ has been demonstrated as an effective strategy for obtaining vertically oriented films such as (BA)1.6(MA)3.4Pb4I13 [41]. As illustrated in Figure 10a, in the conventional (BA)2(MA)3b4I13 structure, Pb–I octahedral layers exhibit a relatively disordered arrangement. Partial substitution of BA+ with MA+ yields a well-ordered vertical alignment of inorganic slabs, driven by the competition between BA+, which tends to confine growth in-plane, and MA+, which promotes out-of-plane orientation. Proper BA+/MA+ cations compositional ratios play a vital role in the degree of crystal orientation. With increasing MA+ content, the reduction in integrated scattering intensity at 0° and 90° for the (111) and (202) diffraction planes reflects the evolution of crystal alignment (Figure 10b). The enhanced dominant peak intensity at 0° indicates a preferred orientation with the (202) plane parallel to the substrate, while the suppression of peaks near 30° and 50° further confirms the out-of-plane alignment of the layered perovskite film.

Figure 10.

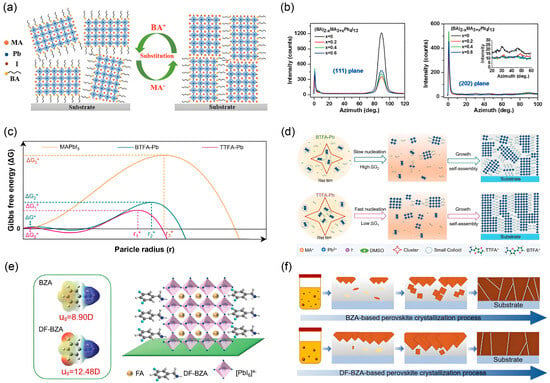

(a) Schematic of layered perovskites with preferential orientation induced by commonly used large-sized organic spacers, BA and PEA. (b) Evolution of preferred crystal orientation in (BA)2−x(MA)3+xPb4I13 perovskite films as the MA+ content (x) increases from 0 to 0.6. Reprinted from Ref. [41], Copyright (2020) Wiley. (c) Schematic free energy profiles for MAPbI3 vs. 2D RP perovskites. (d) Schematic model of the crystallization process for 2D RP perovskites incorporating BTFA and TTFA spacer cations. Reprinted from Ref. [67], Copyright (2023) Wiley. (e) Molecular structures of the BZA and DF-BZA spacers, alongside a schematic of the corresponding DF-BZA-based quasi-2D RP (n = 4) perovskite crystal structure. (f) Schematic diagram of the crystallization process for the corresponding perovskite featuring the DF-BZA spacer. Reprinted from Ref. [68], Copyright (2024) Wiley.

The spacer profoundly influences the nucleation pathway, which in turn dictates the initial stages of oriented crystal growth. As illustrated in Figure 10c, the nucleation mechanisms differ significantly between the TTFA and BTFA spacers [67]. The conjugated TTFA spacer’s strong intermolecular binding energy drives the formation of large clusters in the precursor solution. This facilitates a non-classical nucleation pathway with a drastically reduced Gibbs free energy barrier (ΔG1) compared to the classical pathway of 3D MAPbI3 (ΔG). Consequently, these large clusters readily reach the critical nucleation size, seeding crystals that preferentially favor vertical growth. In contrast, BTFA’s weaker intermolecular forces result in smaller clusters and a higher energy barrier (ΔG2), leading to less controlled and more random nucleation. The initial nucleation events directly govern the subsequent crystallization kinetics and final film orientation, as depicted in Figure 10d. For BTFA-Pb, the small clusters and high nucleation barrier result in slow, stochastic nucleation, forming numerous randomly oriented crystals that yield a discontinuous film with poor vertical alignment. Conversely, the large, low-energy clusters in the TTFA-Pb precursor facilitate the rapid formation of a high density of nuclei with a thermodynamically favored orientation. These initial, well-oriented crystals act as a template, guiding the subsequent vertical growth of the perovskite phase during solvent evaporation and leading to a highly oriented, large-grained film with excellent substrate coverage.

The molecular structure of the organic spacer is a critical determinant for directing crystal orientation. As illustrated in Figure 10e, the introduction of fluorine atoms into the benzylamine-based spacer, creating 3,5-difluorobenzylamine (DF-BZA), imposes a distinct template effect compared to its non-fluorinated counterpart (BZA) [68]. This fluorination strategy not only enhances the molecular dipole moment from 8.90 D in BZA to 12.48 D in DF-BZA but also promotes a stronger interaction with the inorganic lattice. Consequently, the DF-BZA spacer more effectively induces the crystallization of the quasi-2D perovskite with a vertical orientation, as depicted in the crystal structure schematic. This molecular-level control directly governs the crystallization pathway from solution to solid film. Figure 10f schematically compares the crystallization processes mediated by BZA and DF-BZA. The DF-BZA-based precursor solution features larger colloidal aggregates, which serve as superior nucleation sites. These low-energy nucleation centers template the subsequent growth of a dense and uniformly oriented perovskite film with a preferential vertical alignment of the inorganic slabs. In contrast, the BZA spacer, forming smaller aggregates, leads to a less controlled nucleation and growth process, resulting in a film with more random crystal orientation and inferior coverage.

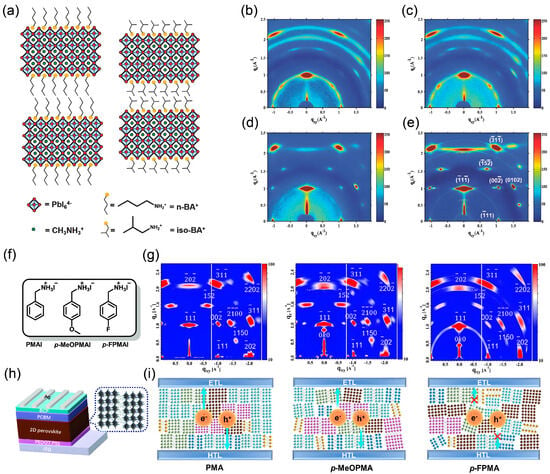

Building upon the discussion of the relationship between spacer molecular nucleation pathways and crystal orientation, Chen et al. and Lai et al. systematically regulated the molecular configuration and electronic properties through rational functional group design, using simple BA and benzylamine (PMA) as molecular prototypes, thereby achieving highly oriented growth of 2D RP perovskites [42,69]. As illustrated in Figure 11a, taking linear n-BA and branched-chain iso-BA as examples, subtle differences in their molecular structures significantly influence crystal stacking behavior: the branched-chain iso-BA, due to its steric hindrance and superior molecular packing ability, promotes a reduction in the interlayer spacing of inorganic slabs, enhances crystallinity, and induces preferential out-of-plane crystal growth. GIWAXS results (Figure 11b–e) further confirm that iso-BA-based perovskites, whether prepared at room temperature or via hot-casting, exhibit distinct Bragg spots, indicating a highly ordered vertical crystal alignment. In contrast, linear n-BA-based samples show continuous diffraction rings, suggesting random crystal orientation.

Figure 11.

(a) Crystal structures of (n-BA)2(MA)3Pb4I13 and (iso-BA)2(MA)3Pb4I13 perovskites with linear and branched butylamine spacers. (b–e) GIWAXS patterns of RT (n-BA)2(MA)3Pb4I13, HC (n-BA)2(MA)3Pb4I13, RT (iso-BA)2(MA)3Pb4I13 and HC (iso-BA)2(MA)3Pb4I13perovskites. Reprinted from Ref. [69], Copyright (2017) Wiley. (f) Molecular structures of the PMAI, p-MeOPMAI and p-FPMAI spacers. (h) The device structure of quasi-2D PSCs. GIWAXS patterns (g) and schematic diagrams (i) of quasi-2D perovskite films based on various organic spacers. Reprinted from Ref. [42], Copyright (2023) Wiley.

Similarly, introducing different substituents into the PMA (Figure 11f), such as para-methoxy (p-MeOPMA) or fluorine (p-FPMA), markedly alters molecular polarity and interfacial interactions. The unsubstituted PMA, with its moderate molecular size and symmetry, facilitates the formation of large, low-energy-barrier pre-nucleation clusters, guiding rapid nucleation and growth of crystals along the vertical direction, thus resulting in highly crystalline, low-defect films (Figure 11g,i). In contrast, the steric hindrance of the methoxy group in p-MeOPMA and the strong electronegativity of fluorine in p-FPMA, while modulating hydrophobicity, disrupt the ideal matching between the organic spacer and the inorganic framework. This leads to an increased nucleation barrier and disordered crystal orientation, ultimately resulting in significantly degraded device performance (Figure 11h).

Therefore, by introducing branched-chain structures into BA or modifying the type and position of substituents on the phenyl ring in PMA, the nucleation pathway and crystal growth kinetics can be effectively optimized. Key design principles include enhancing intermolecular interactions to form large pre-nucleation clusters, tuning molecular dipole moments to strengthen bonding with the inorganic layers, and maintaining molecular symmetry with appropriate spatial volume. Such molecular engineering strategies provide clear and feasible material design directions for realizing highly oriented and efficient 2D RP perovskite.

Beyond the use of single bulky cations, mixed-cation strategies have also been developed to regulate crystal orientation in 2D perovskites. For instance, Chen et al. demonstrated that combining BA+ and PEA+ as binary spacers enhances the vertical orientation of 2D RP perovskite films, facilitating improved out-of-plane charge transport [70]. The PEA0.8BA0.2 system exhibits stronger (111) and (202) Bragg spots in 2D GIWAXS compared to pure PEA-based films, indicating superior crystal alignment. However, the mechanism behind the synergistic effect of PEA and BA remains unclear, especially considering that BA alone typically promotes horizontal alignment. Molecular design strategies based on classic spacers such as BA and PEA, including branching, functional group substitution, and mixed cation blending, effectively regulate crystal orientation in 2D RP perovskites by modulating nucleation pathways and intermolecular interactions. While branched iso-BA and binary PEA-BA systems have demonstrated enhanced vertical alignment compared to their linear or single component counterparts, the fundamental mechanisms governing spacer synergy and orientation control require further investigation to establish clearer structure-property relationships.

(2). 2D Dion–Jacobson-phase perovskite

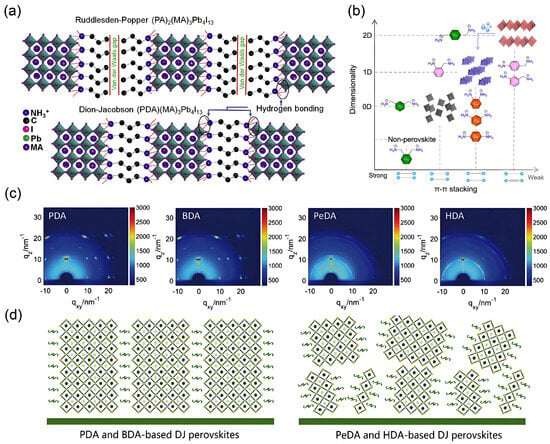

In addition to 2D RP phase perovskite, organic spacer cation also plays critical role in 2D Dion–Jacobson (DJ) phase halide perovskites, in which vdW gap between organic layers are removed and hydrogen bonds are formed on both sides of diammonium cations. For one thing, compared to weak interactions of vdW between interlayers of monovalent organic spacers, stronger interlayer bonding induced by diammonium cations could shorten the distance between the inorganic layers, thereby enhancing structural stability. For another thing, the reduction of organic components also facilitates efficient charge transport properties.

Ahmad et al. fabricated 2D DJ phase (PDA)(MA)3Pb4I13 (n = 4) film with improved crystallinity and preferable vertical orientation in combination with hot-casting method. The inorganic layer is preferred aligned out of plane, forming continuous charge-transport channels and leading to desirable charge transport properties [43]. Typically, 2D RP phase perovskite based on organic spacer only interact with the inorganic perovskite layer on one side, consequently vdW gap exists between organic cations [71]. The use of 1,3-propanediamine+ (PDA+) in DJ phase perovskite could eliminate vdW gap and the hydrogen bonding formed at both sides of PDA+ cations (Figure 12a). The formation of a stable 2D DJ structure is highly dependent on the molecular design of the organic spacer. As summarized in Figure 12b, Guo et al. demonstrated that the molecular symmetry and resultant intermolecular π-π stacking behavior of aromatic diammoniums are decisive factors of HDA [72]. Their work reveals that asymmetric cations suppress π-π stacking, favoring the formation of stable 2D phases. In contrast, highly symmetric cations promote strong π-π interactions, which compete with the inorganic framework formation, leading to dimensional reduction into 1D or 0D structures or causing the degradation of metastable 2D phases under humid conditions. This establishes a crucial structure-property relationship for designing stable DJ perovskites.

Figure 12.

Schematic illustrations and structural characterization of DJ phase 2D perovskites. (a) 2D RP (PA)2(MA)3Pb4I13 and DJ (PDA)(MA)3Pb4I13. Reprinted from Ref. [43], Copyright (2019) Elsevier. (b) The correlation between perovskite dimensionality and the extent of π–π stacking interactions between aromatic diammonium spacers. Reprinted from Ref. [72], Copyright (2024) American Chemical Society. (c,d) GIWAXS patterns and corresponding schematic models depicting the crystal orientation and phase distribution in DJ-phase perovskite films prepared with PDA, BDA, PeDA, and HDA spacer cations. Reprinted from Ref. [73], Copyright (2019) Wiley.

Zheng et al. found that little was known about the effect of large-sized cations with different chain lengths on crystal orientation. To this end, they systematically studied the influence of organic diammonium cations with varying chain lengths, including PDA, 1.4-butanediamine (BDA), 1.5-pentamethylenediamine (PeDA), 1.6-hexamethylenediamine (HAD) [73]. GIWAXS analysis was performed to evaluate the crystal growth orientation based on organic spacers with different chain lengths. PDA2+ and BDA2+ with shorter chains induce preferential crystallographic orientation, whereas longer-chain spacers like PeDA2+ and HAD2+ result in completely random orientation. Furthermore, long-chain amines such as PeDA+ and HAD+ exhibit low solubility in DMF solvent, leading to the preferential formation of low-n-value phases and hindering the growth of high-n-value phases. Additionally, the lower lattice energy of low-n phases makes them thermodynamically favored, further increasing their prevalence in long-chain diamine-based perovskites [73]. Based on previous studies of 2D RP-phase perovskites, these materials tend to exhibit strong horizontal orientation in low n-value phases [16,74]. In this case, the random orientation of the thin film might originate from a large amount of low n-value phases in the film based on the long-chain amine.

Molecular structure design was also extensively applied in 2D DJ perovskites. Zhao et al. employed an asymmetric alkyl diammonium cation, 3-(dimethylammonium)-1-propylammonium (DMAPA2+), as a spacer in n = 4 DJ perovskites [75]. The vertical crystal orientation of the thin film was primarily governed by the formation of a solvent-induced intermediate phase during the crystallization process. The formation and decomposition of the intermediate phase, combined with the structural suitability of the DMAPA2+ spacer, were found to collectively facilitate the transformation from the solvent-induced intermediate phase to the perovskite structure.

In conclusion, strategies for multiple molecular design was extensively applied both in 2D RP and DJ systems [69,75,76], numerous possibilities remain unexplored, such as spacer cations incorporating electron-rich thiophene groups or varying chain lengths. Moreover, the evolution of intermediate phases plays a critical role in the film formation process, as will be discussed in the following section.

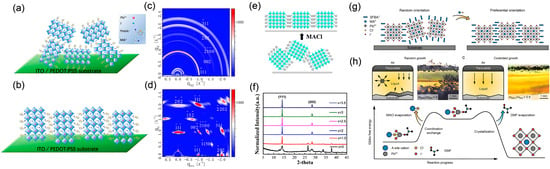

(3). 2D alternating cations in the interlayer space of the perovskite

Beyond the 2D RP and DJ phases, the 2D perovskites with alternating cations in the interlayer space form a distinct structural type, denoted as ACI. The ACI phase exhibits a distinct structural motif and crystallization mechanism that profoundly influences its out-of-plane orientation. As depicted in Figure 13a, the specific ordering of small cations like guanidinium (GA+) and methylammonium (MA+) tightens the interlayer packing, creating a structural predisposition for favorable charge transport pathways [77].

Figure 13.

Schematic illustrations and structural characterization of ACI-phase 2D perovskites. (a) Unit cell structure of the ACI-phase 2D perovskite. Reprinted from Ref. [77], Copyright (2017) American Chemical Society. (b) Schematic illustrations and in suit GIWAXS patterns of the formation process for 2D ACI perovskites. (c) Schematic model illustrating the self-assembly of the 2D ACI perovskite. Reprinted from Ref. [44], Copyright (2019) American Chemical Society.

The formation of ACI perovskite films is a complex process involving dynamical transformation through intermediate phases. In situ GIWAXS analysis was employed to trace the transformation pathway from a disordered sol–gel precursor to the ACI perovskite, revealing that this process undergoes key intermediate phases including crystalline solvates and the 2D GA2PbI4 phase [44]. The preferential vertical orientation in the final film is governed by the nature and evolution kinetics of these intermediate phases. Further investigation through various processing methods confirmed the crystallization kinetic pathways of vertically oriented ACI 2D perovskites.

In antisolvent-processed films, rapid solvent extraction effectively suppresses random nucleation of PbI2 while promoting the formation of a specific intermediate scaffold structure. This scaffold acts as a template guiding the subsequent growth of the ACI phase, enabling the inorganic slabs to align perpendicular to the substrate. In contrast, hot-cast films follow a different pathway where fast solvent evaporation under heating conditions excessively stabilizes the randomly oriented 2D GA2PbI4 intermediate phase, ultimately leading to multiple competing crystal orientations in the final ACI perovskite film.

Therefore, achieving controlled orientation in 2D ACI perovskites requires precise regulation of intermediate phase transformations to form highly oriented templates. This approach aligns with the previously discussed concepts of highly oriented nucleation and template-guided crystallization, further validating the key scientific questions addressed in this review and providing valuable guidance for research on oriented growth of 2D ACI perovskites.

3.3. Solvent Engineering

Based on the understanding of nucleation and crystal growth mechanisms, solvent engineering emerges as a powerful strategy to precisely control these processes by modulating solution thermodynamics and crystallization kinetics. The choice of solvent directly influences the coordination chemistry, intermediate phase formation, and solvent evaporation rate, thereby dictating the nucleation pathway and the final crystal orientation. Previous studies on 3D PSCs revealed that the strongly coordinating solvents like DMSO could form stable solvated intermediates, which significantly increase the perovskite formation energy barrier [78,79]. When considering 2D perovskite systems, intermediate phases similarly serve as a crucial transitional stage that governs both crystal characteristics and charge transport properties. The coordination strength between solvent molecules and perovskite precursors represents a key governing factor, as it determines the initial state of the solvent-induced intermediate phase and directs the subsequent crystal growth pathway.

Soe et al. developed an approach, complementary to hot casting, that utilizes a DMF/DMSO mixed solvent to achieve predominant vertical growth in 2D RP perovskite films [80]. In presence of DMF alone, rapid solvent volatilization promotes homogeneous nucleation within the precursor solution, resulting in degraded film crystallinity and poor crystallographic orientation. However, films prepared by employing DMF/DMSO solvent with appropriate ratio could slow down the solvent volatilization rate and induce heterogeneous nucleation. The subsequent recrystallization during annealing then proceeds analogously to seed-induced growth [57]. The stronger hydrogen bonding capability of DMSO further facilitates the assembly of these nuclei into a preferentially oriented structure. However, an excess of DMSO can be detrimental. The overly stabilized intermediates require more energy to decompose, which can hinder the complete reaction between Pb2+ and organic cations (MA+, PEA+), leading to the formation of disordered, low-n-value phases that favor parallel orientation, as evidenced by low-angle XRD peaks [81]. This underscores the delicate balance in solvent engineering: sufficient coordination is needed to guide nucleation, but excessive coordination can arrest growth.

The solvent evaporation rate is another critical kinetic lever, as it directly controls solution supersaturation. A rapid evaporation rate causes a sharp spike in supersaturation, triggering excessive homogeneous nucleation within the bulk solution. This results in a high density of randomly oriented crystallites and films with poor orientation. In contrast, a slow evaporation rate maintains a low and sustained supersaturation level. This condition favors the growth of existing nuclei over the formation of new ones, allowing for the development of large, vertically aligned grains. The slow kinetics allow the system to find the thermodynamically favored configuration, often guided by the anisotropic liquid–air interface, leading to the observed preferential orientation.

Gao et al. simulated the crystal growth process through antisolvent extraction [36]. As illustrated in Figure 14a,b, in pure DMF solvent, weak coordination leads to the simultaneous presence of perovskite phases and disordered solvent intermediates after antisolvent dripping. The coexistence of perovskite phase and solvent-induced intermediate phase ((MAI)x(PEAI)yPbI2(DMF)z after antisolvent extraction results in inferior film crystallinity and relatively random orientation during subsequent annealing. A properly formulated solvent system can promote the formation of a specific intermediate complex that templates the growth along the (110) direction, yielding a vertically oriented structure. Chen et al. similarly employed a ternary solvent strategy to control crystallization kinetics in blade-coated DJ perovskites [37]. As illustrated in Figure 14c, the ternary solvent (DMF:DMSO:NMP) enables a more retarded and controlled crystallization compared to the binary system, facilitating the formation of a graded phase distribution with small-n phases preferentially located near the bottom and large-n phases enriched at the top. More importantly, the GIWAXS patterns in Figure 14d reveal that the film processed from the ternary solvent exhibits sharp Bragg spots, confirming a high degree of vertical crystal orientation. In contrast, the diffraction rings observed in films from pure DMF or the binary solvent are attributed to a random crystallite orientation. This vertically aligned structure, combined with the graded phase distribution, significantly enhances out-of-plane charge transport.

Figure 14.

Solvent engineering for vertical orientation control in 2D perovskite films. (a) Schematic illustration of crystal growth and corresponding 2D GIWAXS patterns for (PEA)2(MA)4Pb5I16 films prepared with different DMF/DMSO ratios, demonstrating enhanced orientation and crystallinity from the mixed solvent. (b) Schematic illustration of 2D perovskite crystal growth in pure DMF solvent and mixed solvent DMF/DMSO. Reprinted from Ref. [36], Copyright (2019) Wiley. (c) Schematic illustration of the 2D perovskite film formation from solvent systems of increasing complexity: DMF, DMF:DMSO, and DMF:DMSO:NMP. (d) GIWAXS patterns of the resulting 2D perovskite films processed from DMF, DMF:DMSO, and DMF:DMSO:NMP solvent systems. The white arrows indicate the presence of low-dimensional phases. Reprinted from Ref. [37], Copyright (2022) Wiley.

In summary, solvent engineering transcends simple solvent selection. It is a deliberate strategy to manipulate the crystallization kinetics and intermediate phase chemistry to favor a template-guided, vertical growth mode. By carefully balancing solvent coordination strength and evaporation rate, researchers can effectively control nucleation density, suppress random nucleation, and steer the growth of 2D perovskite films toward a highly oriented morphology.

3.4. Additive Assistance

Introducing additives into the precursor solution has emerged as a powerful strategy for achieving preferential crystallographic orientation in perovskite films. While widely used to enhance crystallinity in 3D perovskites, additives have recently been shown to similarly benefit 2D perovskite systems by improving crystal growth, reducing grain boundaries, extending charge carrier diffusion length, and prolonging carrier recombination lifetime [14].

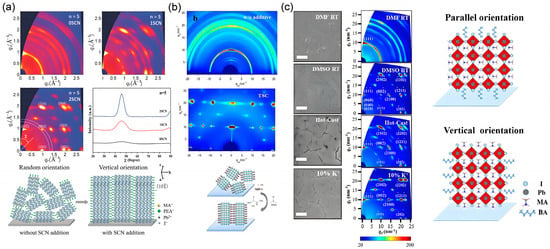

Additives containing an SCN group were widely reported as a pronounced additive for vertical crystal orientation of 2D perovskite film [38], in which SCN- ions played a critical role during the crystallization process. Jiang et al. proposed that the lone pairs of electrons from S and N atoms in linear SCN- could strengthen its interaction with Pb2+ ions, a mechanism that contributes to desired film crystallization in 3D CH3NH3Pb(SCN)2I based perovskite [82]. Zhang et al. demonstrated that incorporating NH4SCN into the (PEA)2(MA)4Pb5I16 system yielded highly crystalline, vertically aligned films [38]. GIWAXS characterization revealed a transition from continuous diffraction rings in the pristine film to sharp Bragg spots after NH4SCN addition, confirming preferred vertical orientation with the (101) planes parallel to the substrate (Figure 15a). The coordination between SCN− and Pb2+ facilitates the perpendicular alignment of [PbI6] octahedra to the substrate, creating direct charge transport pathways between the charge transport layers and enhancing carrier mobility. This orientational control, attributed to the strong Pb2+ coordination and the comparable size of SCN− to I−, has been consistently observed in other systems like (BA)2(MA)n−1PbnI3n+1, where NH4SCN addition transforms randomly oriented films into vertically aligned structures with enlarged grain size [83].

Figure 15.

(a) Additive engineering for vertical orientation control in 2D perovskite films. (a) 2D GIWAXS patterns of (PEA)2(MA)4Pb5I16 films without and with NH4SCN additive, showing the transition from random rings to sharp Bragg spots with corresponding crystal alignment schematic. Reprinted from Ref. [38], Copyright (2018) Wiley-VCH. (b) Schematic of the precursor aggregation and crystallization process induced by the synergistic effect of DMSO and TSC additives, alongside GIWAXS patterns of (BA)2(MA)3Pb4I13 films without and with additives. Reprinted from Ref. [40], Copyright (2020) Elsevier. (c) SEM images and corresponding schematics of quasi-2D perovskite films prepared without and with K+ incorporation, showing the improved pinhole-free morphology and vertical orientation. Reprinted from Ref. [39], Copyright (2019) American Chemical Society.

Beyond thiocyanate-based additives, synergistic effects between additives and the incorporation of alkali metal ions have also proven effective. Zheng et al. showed that a combination of DMSO and thiosemicarbazide (TSC) acts as a mixed additive, inducing precursor aggregation into large pre-nucleation clusters [40]. This reduces nucleation density and promotes the growth of vertically oriented (BA)2(MA)3Pb4I13 films. The S-donor and –NH2 groups in TSC interact with PbI2, BAI, and MAI, facilitating this aggregation. Consequently, crystals grow preferentially from these clusters, minimizing random nucleation in the solution and leading to a preferentially oriented layered perovskite film, as confirmed by GIWAXS (Figure 15b).

Similarly, Kuai et al. reported a simple yet effective method by incorporating potassium ions (K+) into the precursor solution [39]. The doped K+ ions significantly altered the crystallization dynamics, directly promoting the formation of a vertically oriented quasi-2D phase without intermediate compounds, as revealed by in situ synchrotron-based GIWAXS (Figure 15c). This approach not only achieved high orientation but also narrowed the phase distribution and suppressed trap states, leading to efficient and stable solar cells.

Beyond the non-volatile additives discussed above, volatile additives, particularly methylammonium chloride (MACl) and ammonium chloride (NH4Cl), have demonstrated a more dynamic and powerful capability in regulating the crystallization process of 2D perovskites. Their high volatility allows them to participate actively in the formation of intermediate phases and guide crystal growth, before eventually escaping the film during annealing, thus minimizing detrimental incorporation into the final lattice and enabling the production of high-quality, oriented films.

As illustrated in Figure 16a, Lai et al. demonstrated that incorporating MACl into the precursor solution of (ThMA)2(MA)2Pb3I10 (n = 3) 2D perovskite drastically improved the film morphology and crystal orientation [84]. Film without MACl showed random crystallite alignment and poor photovoltaic performance approximately equal to 1.74%. In contrast, with an optimal MACl/MAI weight ratio of 0.5, a dense nanorod-like structure with near-single-crystalline quality was formed, where the inorganic slabs aligned perpendicular to the substrate. This vertical orientation facilitated efficient charge transport, resulting in a remarkable PCE exceeding 15%. The GIWAXS patterns clearly showed a transition from diffuse rings to sharp Bragg spots, confirming the enhanced vertical alignment.

Figure 16.

Volatile additive engineering for vertical orientation control in 2D perovskite films. (a–d) Schematic diagrams and 2D GIWAXS patterns of (ThMA)2(MA)2Pb3I10 films without and with MACl additive, showing the transition from random orientation to vertically aligned crystals. Reprinted from Ref. [84], Copyright (2018) American Chemical Society. (e) Schematic of the MACl-induced intermediate phase formation and crystallization process without antisolvent treatment. (f) XRD patterns of (PEA)2(MA)4Pb5I16 films with varying MACl contents, demonstrating enhanced crystallinity and preferred orientation. Reprinted from Ref. [85], Copyright (2020) Elsevier. (g) Schematic of randomly oriented crystallites (left) and crystallites oriented vertically relative to the substrate (right) with MACl additive. (h) Schematic illustration and corresponding optical images demonstrating how MACl guides crystallization via preferential nucleation at the liquid–air interface, suppressing random crystallite formation in the bulk solution. Reprinted from Ref. [86], Copyright (2023) Wiley.

Similarly, Huang et al. achieved high crystallinity and vertical orientation in (PEA)2(MA)4Pb5I16 (n = 5) films using MACl additive without anti-solvent treatment (Figure 16e) [85]. MACl additive induced the formation of an intermediate phase composed of perovskite crystals even before annealing, which directly transformed into vertically aligned films upon thermal treatment. XRD patterns revealed intensified (111) and (202) peaks with reduced full width at half maximum (FWHM), indicating improved crystallinity and preferred orientation. The resulting solar cells achieved a PCE of 9.74%, significantly higher than the 0.66% efficiency of devices without MACl.

Furthermore, the mechanism behind MACl-induced vertical orientation has been elucidated in recent studies [86]. As illustrated in Figure 16g, the addition of MACl transforms randomly oriented crystallites into vertically aligned ones relative to the substrate. This alignment is driven by the preferential nucleation at the liquid–air interface, as depicted in Figure 16h. Specifically, MACl forms a stable coordination complex with PbI2 and the A-site cation in the precursor solution, which suppresses uncontrolled crystallization in the bulk or at the substrate interface. Upon heating, the volatile MACl evaporates preferentially from the liquid–air interface, leaving behind a thermodynamically less stable intermediate. This metastable complex readily nucleates at the interface, guided by surface tension, and promotes the growth of highly oriented perovskite crystals as the solvent evaporates. This process effectively suppresses random crystallite formation in the bulk solution, leading to dense, pinhole-free films with near-single-crystalline quality. The understanding of this nucleation-guided mechanism not only explains the enhanced crystallinity and vertical orientation but also provides a general strategy for controlling perovskite crystallization using volatile additives, contributing to the development of efficient and stable perovskite optoelectronics.

In summary, the assistance of additives, both non-volatile and volatile, has become a cornerstone strategy for achieving vertical orientation in 2D perovskite films. These additives tailor the crystallization kinetics, promote anisotropic growth, and enhance the alignment of inorganic slabs, thereby facilitating efficient charge transport and reducing recombination losses. As a result, additive-assisted vertical orientation has significantly boosted the performance and stability of 2D PSCs, bringing them closer to commercialization. Future efforts should focus on elucidating the universal mechanisms of additive-directed crystallization and exploring novel additive combinations for further improvements.

3.5. Unique Crystallization in 2D/3D Perovskite Heterostructures

Beyond the vertical alignment in pure 2D or quasi-2D perovskite systems, recent studies have explored unique crystallization behaviors in 2D/3D perovskite heterostructures to synergistically combine high efficiency and superior stability.

A notable example is the growth of a phase-pure 2D layer atop a 3D perovskite film via a rational solvent design strategy, which constitutes a complete spin-coating process for bilayer heterostructures [87]. The key was to use a solvent, such as acetonitrile (MeCN), with a high dielectric constant (εr > 30) to dissolve the 2D perovskite precursors, and a moderate Gutmann donor number (5 < DN < 18 kcal/mol). This specific solvent property window prevents the dissolution of the underlying 3D film during the coating process, allowing the deposition of a “seed” solution. Upon annealing, these seeds crystallize into a defined 2D perovskite layer. GIWAXS analysis revealed that the resulting 2D layer exhibits a mixed orientation with a significant fraction of vertically aligned crystals. This mixed texture creates pathways for efficient vertical charge transport, enabling a high PCE of 24.5%. In a complementary approach, Garai et al. demonstrated the formation of a 2D-3D graded heterostructure through surface recrystallization induced by a multifunctional molecule, 4-(aminomethyl)benzoic acid hydrogen bromide (ABHB) [88]. When spin-coated onto 3D perovskite film, the ABHB molecule facilitates a surface reaction. The amine group promotes the formation of a thin 2D perovskite capping layer, while the bromide ions fill iodide vacancies in the underlying lattice, and the carboxylic acid group passivates uncoordinated Pb2+ defects. XRD depth profiling confirmed the formation of a 2D phase predominantly at the top surface, which diminished with increasing penetration depth, confirming the graded nature of the heterostructure.

These works highlight the potential of spontaneous self-assembly in 2D/3D heterostructures during crystallization, offering promising strategies for designing next-generation perovskite optoelectronic devices with balanced performance and durability.

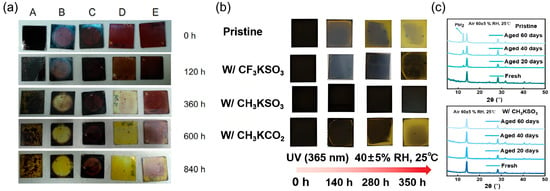

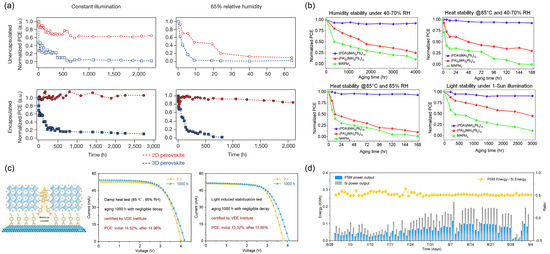

4. Impact of Vertically Oriented 2D Perovskite Film on Device Performance