Abstract

Heat exposure in summer increases the risk of heat strain during work and rest, highlighting the need for effective cooling strategies. This study evaluated the cooling effectiveness of a fan-cooling jacket (FC) and a thermoelectric neck cooler (NC) under resting conditions in a hot and humid environment. Six healthy males completed three trials (no cooling, FC, and NC) in an environmental chamber (35 °C, 70% RH). Thermophysiological responses (mean skin temperature, armpit temperature, sweat volume) and psychological ratings (thermal comfort, wetness sensation) were simultaneously assessed. FC significantly reduced mean skin temperature, attenuated the rise in axillary temperature, and decreased sweat volume while also improving thermal comfort and wetness sensation. In contrast, NC provided only transient improvements in comfort and did not suppress the rise in axillary temperature; wetness sensation deteriorated over time, likely due to its localized and limited cooling area. These findings indicate that, under low-activity conditions, broad-area forced convection cooling is more effective for mitigating heat stress than localized neck cooling. The results highlight the practical utility of fan-cooling garments for rest periods and other low-intensity scenarios.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the progression of global warming and the urban heat island effect have heightened the risk of heatstroke during work or exercise in high-temperature environments during summer [1,2,3]. In contexts such as outdoor labor, sports competitions, and disaster response activities, prolonged exposure to hot and humid conditions is often unavoidable. This exposure has been associated with decreased work efficiency, impaired judgment, and even life-threatening situations due to increased core body temperature and dehydration [4,5,6]. From the perspective of heatstroke prevention, establishing effective cooling methods to mitigate the rise in body temperature and reduce heat stress is imperative.

One countermeasure that has garnered significant attention is the use of wearable cooling devices that can be affixed to clothing or directly to the body. This technology is distinguished by its exceptional portability and flexibility, enabling its application not only during work but also during breaks or rest periods.

Personal wearable cooling technologies have been developed in various forms [7]. Among the non-electric variants are latent heat cooling systems utilizing ice or phase change materials (PCM), as well as radiative cooling methods. These technologies offer the advantages of simplicity and the absence of a power supply requirement. However, challenges persist regarding the duration and magnitude of cooling, as well as comfort-related issues such as weight and flexibility. Electric-powered variants include garments equipped with fans that utilize airflow, liquid cooling systems that circulate refrigerants, and cooling mechanisms employing thermoelectric devices. While these technologies provide enhanced cooling performance, they are associated with increased structural complexity, additional weight, and concerns regarding energy efficiency.

Recent investigations into wearable cooling technology have concentrated on fan-cooling garments (FC) [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Evidence suggests that these fan-integrated wearables, which incorporate fans into jackets, facilitate heat dissipation through evaporation and effectively mitigate increases in core body temperature, even in environments where the ambient temperature surpasses body temperature [16]. Further research has explored the placement of fans and the distribution of airflow across the torso, revealing that ventilation design significantly affects both local and overall cooling efficacy [17]. Hybrid systems that integrate phase-change materials (PCM) with forced convection have underscored the potential for augmenting cooling efficiency and prolonging thermal relief [18]. Recent advancements include the development of compact fan panels and lightweight ventilation structures, which aim to enhance thermal comfort during everyday use [19].

In applied research conducted within workplace settings, the practicality and efficacy of FC have been validated through simulated tasks. Such clothing has been shown to decrease the heat stress index and evaporative resistance in occupational environments [20]. Furthermore, investigations utilizing sweating thermal manikins have corroborated that physiological heat load can be mitigated in warm and dry conditions [21]. These findings underscore the FC as a promising strategy for mitigating occupational heat stress. Concurrently, thermoelectric neck cooler (NC), which are widely employed in sports, labor, and daily life, have been assessed as practical cooling interventions [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. Local neck cooling can affect thermal sensation and exercise performance, although its impact on core body temperature remains unclear.

Collectively, these studies have advanced our understanding of FC and NC systems; however, their evaluations have typically been conducted in isolation, utilizing distinct cooling protocols, environments, and participant cohorts. Consequently, it remains challenging to draw definitive conclusions regarding the relative advantages, limitations, and mechanisms of FC and NC based solely on existing evidence. Furthermore, most research has concentrated on cooling efficacy during exercise or work, with significantly fewer studies examining these devices during rest, despite the fact that rest periods often represent the most practical opportunity for recovery and thermoregulation in occupational or daily activities. Notably, a systematic comparison of convective whole-torso cooling (FC) and localized conductive cooling (NC) under identical heat loads is lacking.

In both professional environments and everyday scenarios, effectively cooling the body during rest periods can mitigate accumulated heat stress, facilitate the recovery of body temperature, and contribute to maintaining performance and safety in subsequent activities. Consequently, assessing the cooling effects of wearable devices during rest periods is of significant practical importance, as it directly pertains to real-world cooling opportunities.

In this study, we examined the thermoregulatory effects and subjective comfort of the FC and NC under resting conditions in a hot and humid environment. By evaluating physiological indicators (mean skin temperature, armpit temperature, and sweat volume) and psychological indicators (comfort/discomfort and dryness/wetness) in an integrative manner under standardized conditions with the same subjects, the objective was to provide valuable insights into the effectiveness and characteristics of cooling methods under static conditions.

2. Methods

Three distinct cooling methodologies were employed as experimental conditions: (1) cooling via fan-cooling jacket (FC condition), (2) thermoelectric neck cooler (NC condition), and (3) a control condition without cooling interventions.

2.1. Participants

This study involved six healthy male university students aged 18 years or older, all of whom satisfied the following criteria: stature ranging from 160 to 180 cm, no prior experience of skin irritation from adhesive tape, and no history of heatstroke. The participants’ ages and anthropometric data are presented in Table 1. All participants reported no history of cardiovascular or respiratory diseases, no previous incidents of heatstroke, and self-reported their ability to engage in light-to-moderate physical activity in hot environments. Prior to participation, all individuals were thoroughly briefed on the research objectives, procedures, potential risks, and anticipated benefits, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Human Research at Shinshu University (Approval Number: 394).

Table 1.

Age and body measurements of participants.

2.2. Samples

Among the wearable cooling devices, KAZEfit (KF1SV, Yamazen Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was selected as the fan-cooling jacket (FC), and the Neck Cooler Slim (TKNNC22, THANKO, Tokyo, Japan) was selected as the thermoelectric neck cooler (NC). The characteristics and rationale for the adoption of each device are delineated below. Initially, in selecting the fan-cooling jacket (FC), this study utilized a commercially available model featuring fans installed on the lower back, specifically around the waist area. In recent years, most commercially available fan-cooling jacket has adopted a configuration with two intake fans positioned on the lower back. This design has become prevalent owing to considerations of safety, mobility, and weight distribution at worksites. This arrangement facilitates the intake of air into the clothing from the waist area, allowing it to flow upward throughout the garment, thereby creating effective forced convection across a broad torso area. Furthermore, Zhao et al. [17] reported that the positioning of the fans influences cooling efficiency, and that with fans located at the waist, the latent heat of evaporation from the torso can be utilized more effectively. In light of this, the present study employed a commercially available product with fans positioned on the lower back, as this design is the most widely used in practical applications and offers high comparability with previous studies. Conversely, Neck Cooler Slim (TKNNC22, THANKO Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) is a conductive cooling device that employs a thermoelectric (Peltier) element. When activated, the cooling plate side becomes cold, providing localized cooling upon contact with the neck sides. This device lacks a mechanism to circulate air with a fan but is designed to cool blood around the carotid arteries through direct conductive cooling. During operation, the metal cooling plate comes into direct contact with the skin surface, and the heat transfer action of the Peltier element reduces the neck surface temperature. Additionally, the cooling area of this device is relatively small; therefore, although its local cooling performance is high, its direct impact on heat dissipation from the torso and humidity inside the clothing is considered limited.

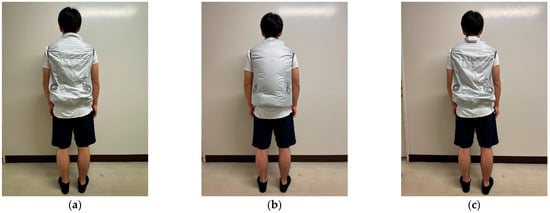

To ensure consistent device performance during the experiment, the fan-cooling jacket was operated at its maximum airflow setting (70 m3/h). The neck cooler was also used at its maximum intensity, beginning one minute prior to the onset of cooling, at which time the surface temperature of the cooling plate was 23 °C. The attire was designed to replicate summer conditions: a short-sleeved shirt (88% polyester, 12% polyurethane), shorts (80% polyester, 20% nylon), underwear (93% cotton, 7% polyurethane), and socks (47% acrylic, 29% cotton, 18% nylon, 4% polyester, 2% polyurethane), with the fan-cooling jacket worn as outerwear. In the FC condition, the fan was activated, whereas in the NC condition, a thermoelectric neck cooler was used. The clothing configuration for each condition is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Clothing styles by condition. (a) Non-cooled condition. (b) FC condition. (c) NC condition.

2.3. Protocol

The experiment was conducted over three days for each participant, with each of the three conditions—① non-cooling condition, ② FC condition, and ③ NC condition—administered on different days. The experiment commenced at a consistent time for each participant, who was required to complete their meals at least two hours prior to the start; from that point until the conclusion of the experiment, neither food nor drink was permitted. Furthermore, to mitigate the effects of habituation, the sequence of the ② FC and ③ NC conditions was randomized for each participant. Thirty minutes prior to the experiment, the participants entered the anteroom (room temperature 25 °C, humidity 50% RH), consumed 150 mL of water, and underwent a pre-experiment nude body weight measurement, after which further water intake was restricted. Participants then changed into experimental attire, equipped themselves with the measuring devices, and entered the experimental chamber simulating a hot environment (room temperature 35 °C, humidity 70% RH), where they were instructed to remain seated and at rest. For the initial 25 min, irrespective of the condition, this period was designated for acclimatization to the hot environment, and no body cooling was implemented. Following the acclimatization period, in the ② FC condition, the fans of the fan-cooling jacket were activated at maximum airflow, and in the ③ NC condition, a thermoelectric neck cooler was applied; in both scenarios, body cooling was conducted for 30 min. Upon completion of the experiment, participants promptly exited the chamber, the measuring devices were removed, and after wiping off the sweat from the skin surface, their post-experiment nude body weight was measured. The participants were then required to rehydrate with a sports drink or similar beverage. If any participant reported feeling unwell during the experiment, the procedure was immediately halted, and rehydration and body cooling were performed.

2.4. Measurement Items

To assess temporal variations in the heat load, measurements were conducted on psychological indices, sweating amount, skin temperature, and armpit temperature.

For psychological indices, participants were required to provide sensory evaluations of their comfort/discomfort and dryness/wetness sensations at 5 min intervals, commencing from the conclusion of the heat acclimation period (0 min) as outlined in the Section 2.3 protocol, and continuing until the experiment’s conclusion. Although various scales exist for thermal psychological measurements, this study selected “comfort/discomfort” and “wetness” to evaluate the efficacy of fan-cooling jacket in hot environments. The comfort/discomfort scale was developed with reference to ISO standards [30] and comprised five levels: “0: Comfortable,” “−1: Slightly uncomfortable,” “−2: Uncomfortable,” “−3: Very uncomfortable,” and “−4: Extremely uncomfortable.” It is important to note that “comfortable” on this scale signifies “not uncomfortable” and is not synonymous with “actively comfortable.” The dryness/wetness scale consisted of seven levels: “−3: Very wet,” “−2: Wet,” “−1: Slightly wet,” “0: Neither,” “1: Slightly dry,” “2: Dry,” and “3: Very dry.” These evaluations specifically targeted the “wetness sensation inside the clothing,” rather than the whole-body sensation.

The amount of sweating was determined by calculating the decrease in body weight. Specifically, the reduction in nude body weight before and after the experiment, along with the participant’s body surface area, was used to calculate body weight loss according to the formulas by Kurasumi et al. (Equations (1) and (2)). A precision body scale for humans balance (Mettler ID2 Multirange Scale, Mettler-Toledo International Inc., Greifensee, Switzerland) was used to measure body weight.

where:

B = 0.0100315 × W0.383 × H0.693

B: Body surface area (m2);

W: Weight (kg);

H: Height (cm).

where:

S = (Reduction in nude body weight (g)/(B/T)

S: Sweat volume (g/(m2·h));

R: Reduction in nude body weight before and after the experiment (g);

B: Body surface area (m2);

T: Time (h).

Skin temperature was measured by attaching thermocouples (AMI-T/3K, AMI Techno Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) to four sites: the chest, upper arm, thigh, and lower legs. Data were recorded using a compact thermologger (AM-8061 K, Anritsu Meter Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The mean skin temperature was calculated using the Ramanathan four-point method (Equation (3)) using the values from each site.

where:

Mean skin temperature (°C) = 0.3 × (A1 + A2) + 0.2 × (A3 + A4)

A1: Chest temperature (°C);

A2: Upper arm temperature (°C);

A3: Thigh temperature (°C);

A4: Lower leg temperature (°C).

The armpit temperature was measured as the axillary temperature, with a thermocouple placed in the participant’s left armpit and secured under the arm throughout the experiment. The devices used were identical to those used for skin temperature measurements: a thermocouple and compact thermologger.

Skin and armpit temperatures were taken at 1 s intervals from immediately after entering the laboratory in the Section 2.3 protocol until the conclusion of the experiment. For analysis, the change from the average value over the one minute immediately preceding the end of the heat acclimation period was calculated, and the average for each 5 min interval was determined.

3. Results and Discussion

Participants who reported feeling unwell during the experiment and subsequently discontinued participation were excluded from the analysis. Specifically, Panel 6 in the FC condition and Panel 1 in the NC condition were omitted, resulting in a final analysis sample comprising: ① six participants in the non-cooling condition, ② five in the FC condition, and ③ five in the NC condition.

3.1. Psychological Indices (Thermal Comfort, Wetness Sensation)

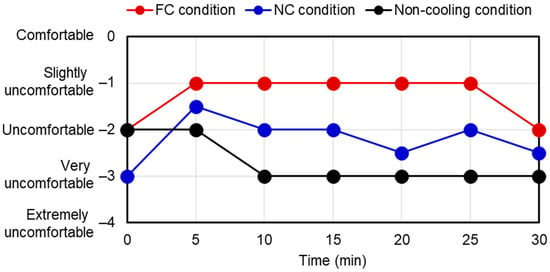

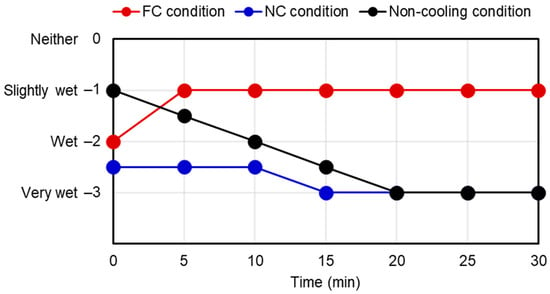

The median values of participants’ thermal comfort and wetness sensation, obtained following the heat acclimation period, are presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3. In the non-cooling condition, thermal comfort progressively declined towards discomfort as the experiment progressed, and wetness sensation also shifted towards “very wet.” This indicates an increase in psychological heat stress over time. Conversely, in the FC condition, cooling with the fan improved both thermal comfort and wetness sensation by approximately one level from the conclusion of the acclimation period (0 min) onward, confirming a reduction in psychological heat stress. Notably, thermal comfort was maintained in a favorable state for up to 25 min, and wetness sensation remained favorable until the end of the experiment, with neither showing a decreasing trend. At the 20 min mark, the FC condition demonstrated an approximately two-step greater reduction in heat stress than the non-cooling condition. In the NC condition, thermal comfort improved by approximately one level after cooling commenced, confirming a temporary reduction in heat stress. However, wetness sensation deteriorated over time, shifting towards “very wet.” This suggests that although local cooling of the neck can provide temporary comfort, it is insufficient to noticeably improve the humid environment inside the clothing.

Figure 2.

Median thermal comfort scores after heat acclimatization.

Figure 3.

Median wetness sensation scores after heat acclimatization.

3.2. Physiological Indices (Mean Skin Temperature, Armpit Temperature, Sweat Volume)

Table 2 presents the sweat volume levels of each participant. The normalized sweat volume was calculated by dividing the sweat volume under each cooling condition by the volume under the non-cooling condition. Under the FC condition, a reduction in sweat volume was observed compared to the non-cooling condition, a trend that was evident in the majority of participants. Conversely, under the NC condition, there was a general tendency for increased sweat volume; however, substantial individual variability was observed, with some participants exhibiting a decrease. Furthermore, a two-tailed t-test was conducted to assess the difference in population means of the normalized sweat volume between the non-cooling and each cooling condition. The results indicated a significant difference in trend between the non-cooling and FC conditions (p < 0.10). In contrast, no significant difference was detected between the non-cooling and NC conditions (p = 0.14).

Table 2.

Sweat volume levels of each participant.

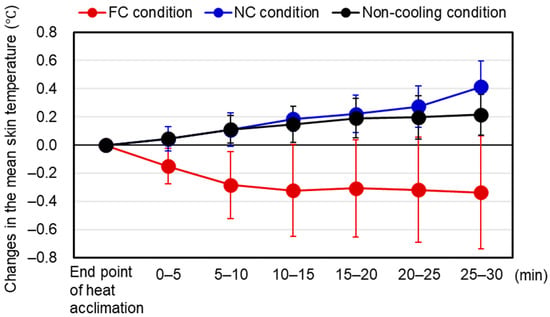

The changes in the mean skin temperature are shown in Figure 4. In the FC condition, skin temperature decreased immediately following the initiation of cooling, with significant differences (p < 0.05) from the non-cooling condition observed at all intervals after 5 min. This phenomenon is attributed to the enhancement in heat transfer at the skin surface owing to the forced convection generated by the fan, resulting in an efficient reduction in skin temperature, particularly around the trunk area. The NC condition demonstrated a pattern similar to that of the non-cooling condition, with a slight increase in skin temperature over time and no significant reduction in skin temperature.

Figure 4.

Change in mean skin temperature averaged across all participants.

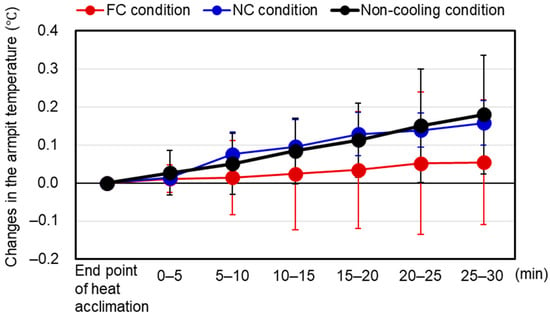

Changes in the armpit temperature are shown in Figure 5. The FC condition exhibited a slight upward trend; however, the magnitude of this increase was smaller than that observed in the non-cooling and NC conditions, with a significant difference (p < 0.05) compared to the non-cooling condition after 25 min. In contrast, the NC condition, akin to the non-cooling condition, displayed an upward trend over time, with no indication of suppression of the core temperature increase.

Figure 5.

Change in the armpit temperature averaged across all participants.

3.3. Heat Stress Reduction Effect of Wearable Cooling Devices (WD) at Rest

In this study, while all wearable cooling devices demonstrated some degree of heat stress alleviation compared to non-cooling conditions, distinct differences were observed in their mechanisms of action and the magnitude of their effects. Under the FC condition, reductions were noted in mean skin temperature, sweat volume, and thermal discomfort. Conversely, under the NC condition, improvements were limited to temporary comfort, with increases in axillary temperature and sensation of dampness not being sufficiently suppressed.

In the FC condition, forced convection from fans positioned at the waist facilitated heat dissipation and evaporation inside the clothing, effectively reducing skin temperature. This finding aligns with previous studies [7,11,12] that have shown ventilated garments enhance evaporative heat loss and mitigate heat load. The fan-cooling jacket utilized in this study follows the widely adopted commercial design of placing fans at the waist, with upward airflow from the hem toward the collar reducing sweat accumulation inside the clothing. Additionally, airflow exiting from the neck and passing over the face likely contributed to a reduction in dampness and an improvement in psychological comfort by cooling the facial skin, which is rich in temperature receptors.

In contrast, under NC conditions, although temporary improvements in comfort were achieved through conductive cooling of the neck using a Peltier device, the effect on suppressing the rise in mean skin temperature and axillary temperature was limited. This result is consistent with previous studies [23,26,29] that reported head and neck cooling primarily alleviates perceived heat sensation but does not easily lead to significant reductions in core body temperature. One possible reason for the minimal physiological effect is the relatively small cooling area. While NC is intended to cool the blood flow around the carotid arteries, in the hot and humid environment of this study (35 °C, 70% RH), the accumulation of body heat was considerable, and local cooling alone likely failed to provide sufficient heat dissipation.

In summary, these results indicate that, in hot and humid environments at rest, forced convection cooling affecting a broad area of the torso is more effective than localized conductive cooling of the neck in reducing both physiological and psychological heat stress. The effectiveness of FC supports existing studies on ventilated clothing and clearly demonstrates its benefits even during periods of low activity, such as breaks during work. In contrast, the effects of NC were limited primarily to improvements in perceived comfort and did not significantly contribute to reducing heat load.

However, this study has several limitations. These include the restriction of participants to young men only, the use of only one type of cooling intensity and design for both FC and NC, and the use of axillary temperature as an indicator of core body temperature. In the future, it will be necessary to conduct more comprehensive studies on optimal cooling strategies by targeting a wider variety of device designs, activity levels, and participant attributes.

4. Conclusions

This study compared two wearable cooling devices—a fan-cooling jacket and a thermoelectric neck cooler—under resting conditions in a hot and humid environment, using identical experimental protocols and the same group of participants. By integrating thermophysiological and psychological indices, this study highlighted key differences in their cooling effects.

Overall, the fan-cooling jacket consistently improved both thermal perception and physiological heat strain, demonstrating reductions in skin temperature, sweat volume, and the rise in axillary temperature. In contrast, the thermoelectric neck cooler provided only short-term perceptual relief and did not meaningfully slow the progression of physiological heat accumulation under resting conditions.

These findings indicate that under low-activity conditions, broad-area forced convection cooling is more effective for sustained heat stress mitigation than localized conductive cooling of the neck. This highlights the practical utility of ventilation-based garments for rest periods or tasks involving minimal physical activity.

Future work should extend these comparisons to different activity levels and cooling schedules, as well as evaluate long-term cooling sustainability and device efficiency. Such investigations will contribute to the development of optimized operational strategies for wearable cooling devices across diverse environmental and occupational settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.M.; methodology, H.M. and T.Y.; software, T.Y.; validation, H.M., T.Y. and H.K.; formal analysis, H.M. and T.Y.; investigation, T.Y.; resources, H.M. and T.Y.; data curation, T.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, H.M. and T.Y.; writing—review and editing, H.M.; visualization, H.M., T.Y. and H.K.; supervision, H.M.; project administration, H.M.; funding acquisition, H.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Human Research at Shinshu University (Approval Number: 394) on 11 July 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FC | Fan-cooling jacket |

| NC | Thermoelectric neck cooler |

References

- Gibb, K.; Beckman, S.; Vergara, X.P.; Heinzerling, A.; Harrison, R. Extreme Heat and Occupational Health Risks. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2024, 45, 315–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, M.; Kjellstrom, T.; Baldasseroni, A. Impact of climate change on occupational health and productivity: A systematic literature review focusing on workplace heat. La Med. del Lav. 2018, 109, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Khayat, M.; Halwani, D.A.; Hneiny, L.; Alameddine, I.; Haidar, M.A.; Habib, R.R. Impacts of Climate Change and Heat Stress on Farmworkers’ Health: A Scoping Review. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 782811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioannou, L.G.; Foster, J.; Morris, N.B.; Piil, J.F.; Havenith, G.; Mekjavic, I.B.; Kenny, G.P.; Nybo, L.; Flouris, A.D. Occupational heat strain in outdoor workers: A comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Temperature 2022, 9, 67–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, J.; Bi, P.; Pisaniello, D.; Hansen, A. Health Impacts of Workplace Heat Exposure: An Epidemiological Review. Ind. Heal. 2014, 52, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebi, K.L.; Capon, A.; Berry, P.; Broderick, C.; de Dear, R.; Havenith, G.; Honda, Y.; Kovats, R.S.; Ma, W.; Malik, A.; et al. Hot weather and heat extremes: Health risks. Lancet 2021, 398, 698–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Han, M.; Fang, J. Personal Cooling Garments: A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 5522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Nagano, C.; Fukuzawa, K.; Hoshuyama, N.; Tanaka, R.; Nishi, K.; Hashimoto, K.; Horie, S. Mitigation of heat strain by wearing a long-sleeve fan-attached jacket in a hot or humid environment. J. Occup. Health 2022, 64, e12323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, T.; Saito, T.; Ohhashi, M.; Hayashi, S. Recovery with a fan-cooling jacket after exposure to high solar radiation during exercise in hot outdoor environments. Front. Sports Act. Living 2023, 5, 1106882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otani, H.; Fukuda, M.; Tagawa, T. Cooling Between Exercise Bouts and Post-exercise With the Fan Cooling Jacket on Thermal Strain in Hot-Humid Environments. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakakibara, K.; Kuwabara, K.; Someya, S.; Yamazaki, K.; Dempoya, A. Thermal Environment That Reduces Physiological and Psychological Burden of Walking Workers Wearing Long-Sleeved Ventilated Working Jacket. J. Environ. Eng. (Transactions AIJ) 2024, 89, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokizawa, K.; Sawada, S.; Oka, T.; Yasuda, A.; Tai, T.; Ida, H.; Nakayama, K. Fan-precooling effect on heat strain while wearing protective clothing. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2014, 58, 1919–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, B. Udayraj Effectiveness of air ventilation clothing in hot and humid environment for decreasing and intermittent activity scenarios. Build. Environ. 2023, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Shin, S.; Lim, D. Cooling performance measurements of different types of cooling vests using thermal manikin. Fash. Text. 2024, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Yang, J.; Wang, F.; Udayraj; Chan, W.C. The cooling performance of forced air ventilation garments in a warm environment: The effect of clothing eyelet designs. J. Text. Inst. 2022, 114, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, K.; Horie, S.; Nagano, C.; Hibino, H.; Mori, K.; Fukuzawa, K.; Nakayama, M.; Tanaka, H.; Inoue, J. A fan-attached jacket worn in an environment exceeding body temperature suppresses an increase in core temperature. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Gao, C.; Wang, F.; Kuklane, K.; Holmér, I.; Li, J. A study on local cooling of garments with ventilation fans and openings placed at different torso sites. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2013, 43, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesada, J.P.; Lucas-Cuevas, A.G.; Gil-Calvo, M.; Giménez, J.V.; Aparicio, I.; de Anda, R.C.O.; Palmer, R.S.; Llana-Belloch, S.; Pérez-Soriano, P. Effects of graduated compression stockings on skin temperature after running. J. Therm. Biol. 2015, 52, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Gao, C.; Wang, M. Development of Air Ventilation Garments with Small Fan Panels to Improve Thermal Comfort. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Ferraro, S.; Falcone, T.; Morabito, M.; Messeri, A.; Bonafede, M.; Marinaccio, A.; Gao, C.; Molinaro, V. A potential wearable solution for preventing heat strain in workplaces: The cooling effect and the total evaporative resistance of a ventilation jacket. Environ. Res. 2022, 212, 113475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Ferraro, S.; Falcone, T.; Morabito, M.; Bonafede, M.; Marinaccio, A.; Gao, C.; Molinaro, V. Mitigating heat effects in the workplace with a ventilation jacket: Simulations of the whole-body and local human thermophysiological response with a sweating thermal manikin in a warm-dry environment. J. Therm. Biol. 2023, 119, 103772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Lei, T.-H.; Wang, F.; Yang, B.; Mündel, T. Head, Face and Neck Cooling as Per-cooling (Cooling During Exercise) Modalities to Improve Exercise Performance in the Heat: A Narrative Review and Practical Applications. Sports Med.—Open 2022, 8, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, C.J.; Borg, D.; Brade, C.; Carter, S.; Filingeri, D.; Lee, J.; Lim, L.; Mündel, T.; Taylor, L.; Tyler, C.J. Head, Face, and Neck Cooling for Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2025, 20, 743–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyler, C.J.; Sunderland, C.; Cheung, S.S. The effect of cooling prior to and during exercise on exercise performance and capacity in the heat: A meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2013, 49, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Xin, G.; Li, H.; Ma, P.; Wang, H. Neck cooling provides ergogenic benefits after heat acclimation during exercise in the heat. Front. Physiol. 2025, 16, 1646930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, C.J.; Wild, P.; Sunderland, C. Practical neck cooling and time-trial running performance in a hot environment. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010, 110, 1063–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, C.J.; Sunderland, C. Cooling the Neck Region During Exercise in the Heat. J. Athl. Train. 2011, 46, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, C.J.; Sunderland, C. Neck Cooling and Running Performance in the Heat. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 2388–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuttell, S.A.; Kiri, V.; Tyler, C. A Comparison of 2 Practical Cooling Methods on Cycling Capacity in the Heat. J. Athl. Train. 2016, 51, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 10551:2019; Ergonomics of the Physical Environment—Subjective Judgement Scales for Assessing Physical Environments. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).