Abstract

This study aims to fabricate magnesium-doped SiOx materials through the integrated application of physical vapor deposition and chemical vapor deposition techniques, with the objective of developing high-performance anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. With the macroscopic particle size held constant, this study endeavors to explore the impact of variations in the size of microscopic silicon crystals on the properties of the material. Under the effect of magnesium doping, the influence mechanism of different microscopic grain sizes on the reaction kinetics behavior and structural stability of the material was systematically studied. Based on the research findings, a reasonable control range for the size of silicon crystals will be proposed. The research findings indicate that both relatively small and large silicon crystals are disadvantageous for cycling performance. When the silicon crystal grain size is 5.79 nm, the composite material demonstrates a relatively high overall capacity of 1442 mAh/g and excellent cycling stability. After 100 cycles, the capacity retention rate reaches 83.82%. EIS analysis reveals that larger silicon crystals exhibit a higher lithium ion diffusion coefficient. As a result, the silicon electrodes show more remarkable rate performance. Even under a high current density of 1C, the capacity of the material can still be maintained at 1044 mAh/g.

1. Introduction

Silicon-based materials, particularly silicon oxide (SiOx) anodes, are considered an ideal choice for the novel lithium-ion battery (LIB) energy storage devices in the future [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. In comparison with silicon, the most significant advantage of silicon oxide lies in the formation of electrochemically inactive lithium silicate and lithium oxide (Li2O) phases during the lithiation process. Through its buffering effect, volume changes can be effectively mitigated, and cycling stability can be enhanced. Simultaneously, there are several challenges that impede its practical applications. Firstly, issues related to insulation and low electrical conductivity persist. Secondly, residual volume changes remain a concern. Finally, the formation of irreversible Li2O and lithium silicate during the initial cycling process results in a relatively low initial Coulombic efficiency (ICE) [8,9,10].

In recent years, in order to tackle the multitude of challenges encountered by silicon oxide-based anode materials in the practical applications of LIBs, both the academic community and industry have invested substantial research resources. Researchers have successfully fabricated a diverse range of composite-structured materials through a variety of methods, including high-energy ball milling (HEBM), etching, chemical vapor deposition (CVD), pyrolysis, disproportionation reactions, melt solidification, mechanical alloying, spray drying, chemical reduction, electrochemical synthesis, and melt spinning. Simultaneously, techniques such as size modulation, morphology engineering, surface encapsulation, composite fabrication, element doping, and pre-lithiation have been extensively reported [11,12,13,14,15].

The synergistic integration of silicon-based materials and carbon materials in one-dimensional, two-dimensional, and three-dimensional architectures can effectively enhance the performance of these materials. Specifically, one-dimensional architectures consist of silicon nanowires (SiNWs) and silicon nanotubes (SiNTs), two-dimensional architectures include silicon nanosheets and silicon thin films, and three-dimensional architectures involve porous silicon and silicon foams. Nevertheless, the precise and controllable synthesis of these micro-and nano-scale architectures still poses significant technological hurdles. The silicon matrix mainly encompasses elemental silicon (Si), silicon dioxide (SiO2), non-stoichiometric silicon oxide (SiOx), and silicon oxycarbide (SiOC), among others. Surface coating techniques can significantly prolong the battery cycle life. This is achieved by suppressing the pulverization of materials and the collapse of structures, as well as cushioning the stress resulting from volume changes during the charge–discharge process. Commonly employed carbon coating forms include carbon nanofibers, carbon nanotubes, amorphous carbon layers, graphite, and graphene. Furthermore, the introduction of heteroatom doping into the carbon layer not only aids in alleviating the volume expansion of the internal materials but also increases the number of surface active sites and enhances the reaction kinetics rate [16,17,18,19]. The incorporation or doping of SiOx with metals, metal oxides, and other functional materials represents a significant focus of current research. Nevertheless, during the preparation process, the introduction of certain metal elements may give rise to an overabundance of magnetic impurities or trace elements within the material. This, in turn, can exert an adverse influence on both the cycling performance and safety of the battery. One of the effective approaches to enhancing the ICE of silicon oxide-based anodes is the implementation of pre-lithiation techniques. The primary methods reported thus far encompass lithium metal supplementation, chemical pre-lithiation, electrochemical pre-lithiation, and the utilization of pre-lithiation additives. However, these methods commonly encounter issues such as intricate processes and elevated costs. Moreover, the development of high-performance, multifunctional electrolytes, conductive agents, and binders is of equal significance in enhancing the overall cycling stability [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. A detailed comparison of the properties of materials obtained through various preparation methods and modification techniques can be found in Table S3 (Supporting Information).

Integrating the synthesis of SiOx with carbon coating techniques has emerged as the mainstream process in contemporary industrial manufacturing. Nevertheless, the majority of existing synthesis methods still encounter substantial challenges in achieving large-scale production. The precursor preparation technology remains one of the pivotal bottlenecks impeding its industrial scalability. In recent years, the “magnesium doping” technique has witnessed progressive development and drawn significant attention within the academic and industrial communities.

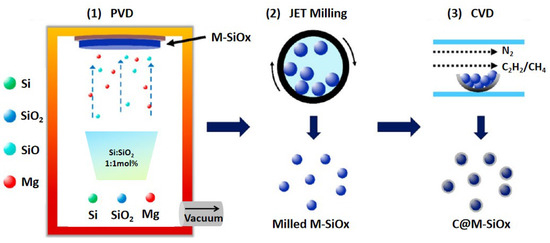

In this study, physical vapor deposition (PVD) was utilized to facilitate an in situ reaction between the magnesium source and silicon–oxygen components at elevated temperatures, leading to the formation of magnesium-doped SiOx. This approach effectively ensures the rapid and homogeneous distribution of magnesium within the material matrix, thereby overcoming the issues of non-uniform dispersion and local agglomeration typically associated with traditional mechanical mixing methods. Simultaneously, through the optimization of the reaction pathway, the occurrence probability of side reactions was markedly diminished, enhancing the controllability of the modification process. This reaction not only enables the incorporation of magnesium but also serves as a purification step, facilitating the acquisition of high-quality composite materials with enhanced compositional homogeneity and reduced structural defects. Subsequently, chemical vapor deposition (CVD) was employed to integrate the synthesized SiOx with a carbon framework. This integration successfully achieved the synergistic combination of multiple key techniques, including size regulation, structural design, element doping, disproportionation reactions, surface encapsulation, and multi-phase composite formation.

Although the magnesium doping strategy has demonstrated notable effectiveness, existing research has predominantly concentrated on optimizing the types of magnesium sources, their addition amounts, and process parameters [34,35]. There is a lack of in-depth exploration regarding how the key structural parameters of SiOx materials themselves, especially the mechanism of the doping process on grain size and its size-dependent behavior, the multi-scale coupling mechanism between grain size, MgSiO3 phase formation, and pore structure evolution, as well as the role played by grain boundaries (such as their influence on reaction activity and phase transformation). The microscopic structure of a material is the fundamental determinant of its macroscopic properties. SiOx materials are composites in which nanoscale silicon grains are uniformly dispersed within a silica matrix [36,37,38]. The size of the internal silicon grains directly impacts the material’s specific surface area, reactivity, and volume change behavior. In previous studies, the factors of microscopic silicon grain size and macroscopic particle size have often been conflated. This is because alterations in the preparation process typically result in concurrent changes in both, making it challenging to distinguish their individual mechanisms [14,39,40,41,42]. In light of this, this study innovatively endeavors to isolate the interfering factor of macroscopic particle size. Through precise process control, a series of magnesium-doped SiOx model materials with similar macroscopic particle size distributions but significantly different microscopic silicon grain sizes were prepared. The aim was to independently unveil the influence of the microscopic silicon grain size, a core structural parameter, on the magnesium doping and the performance of the resultant products.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

The raw material silicon powder (Si) is a crystalline silicon material. The silica powder (SiO2) used is a white powder composed of irregularly shaped amorphous micrometer-sized particles. The particle size of both materials is approximately 10 μm. Magnesium powder (Mg) is produced by cutting magnesium ingots and simple spheroidization treatment. It appears as a silver-white powder and can pass through a 60-mesh sieve (approximately 250 μm).

2.2. Synthesis Method (Synthesis of M-SiOx and C@M-SiOx)

The molar ratios of silicon powder, silica powder, and magnesium powder were precisely controlled, with the corresponding molar ratio being Si:SiO2:Mg = 1.07:1:0.44. As illustrated in Scheme 1, the magnesium-doped silicon oxide (M-SiOx) samples were synthesized via the evaporation-condensation approach within a vacuum furnace (PVD, with a pressure lower than 1 Pa), obtaining products with different silicon microcrystalline structures. The silicon oxide precursors were heated at 1200 °C, 1220 °C, 1240 °C and 1260 °C, and they were then maintained at the respective target temperatures for 10 h. After condensation and deposition, block M-SiOx samples were obtained and labeled as M1-SiOx, M2-SiOx, M3-SiOx, and M4-SiOx in sequence. The M-SiOx underwent jet milling treatment to fabricate M-SiOx powders with precisely controllable particle diameters. In this study, CH4 and C2H2 were selected as carbon sources (QCH4:QC2H2 = 1:1). High-purity N2 was utilized as both the protective gas and the carrier gas. The M-SiOx samples were subjected to carbon-coating modification through chemical vapor deposition. As a result, carbon-coated M-SiOx anode materials were successfully prepared and denoted as C@M1-SiOx, C@M2-SiOx, C@M3-SiOx, and C@M4-SiOx, respectively.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis Process of Carbon-Coated M-SiOx Powder.

2.3. Material Characterization

The crystallinity of the M-SiOx and C@M-SiOx was characterized via X-ray diffraction (XRD). The grain size was calculated based on the Si (111) diffraction peak. The 2θ angle range was set from 24° to 32°. After spectral fitting, the full width at half maximum (FWHM) was obtained, and the silicon grain size was then computed using the Scherrer formula (silicon grain size = 8.2884/FWHM). Thermogravimetric (TG) analysis was performed to determine the carbon content in the samples. The samples were heated from room temperature to 800 °C in air at a heating rate of 10 °C min−1. Additionally, the carbon content was concurrently determined by the combustion-infrared absorption method. The oxygen content in the samples was measured using an oxygen-nitrogen analyzer, while the magnesium content was obtained through inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES). The particle size distribution (PSD) was measured by a Malvern Mastersizer 3000 laser particle size analyzer. The morphological characteristics of the samples were observed via scanning electron microscopy (SEM; Hitachi S-4800,Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

For the electrochemical performance tests, copper foils served as current collectors. 1.0 M lithium hexafluorophosphate (LiPF6) in ethylene carbonate (EC) and ethyl methyl carbonate (EMC) (volume ratio 1:1), with 10 vol% fluoroethylene carbonate (FEC) added as the electrolyte and a Polypropylene/Polyethylene/Polypropylene (PP/PE/PP) composite porous membrane was utilized as the separator. CR2032-type lithium-ion half-cells were assembled within an argon-filled glove box, where the contents of H2O and O2 were both maintained below 0.1 ppm. The assembly of the lithium-ion button-type half-cells was completed following the sequence: negative electrode case→nickel mesh→lithium foil→electrolyte (30 μL)→separator→ electrolyte (30 μL)→membrane→positive electrode case.

After assembly, the cells were allowed to age statically at 25 °C for 24 h before undergoing electrochemical testing. The cycling performance tests were conducted on a LAND CT2001A battery testing system at 25 °C. The voltage range was set from 0.005 to 1.5 V (vs. Li+/Li), the cell was discharged at a current of 0.1 C until the cutoff voltage of 0.05 V, and then discharged at a current of 0.01 C until the cutoff voltage of 0.005 V for fully lithiated. After, the half coin cell was charged at a current of 0.1 C until the cutoff voltage of 1.5 V. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were carried out on a CHI604D electrochemical workstation. The frequency range spanned from 106 to 10−2 Hz, and the amplitude of the AC perturbation signal was set at 5 mV.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of M-SiOx and C@M-SiOx

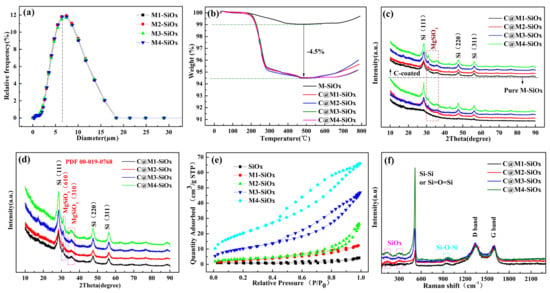

Through precise process control, magnesium-doped SiOx materials with a similar macroscopic particle size distribution were synthesized. The D50 particle size of these materials is 6.02 μm from depicted in Figure 1a. In this study, Methane and acetylene mixed gas as the gas source selected as the carbon source, it can be discerned from Figure 1b that, the carbon content was controlled at approximately 4.5%. Below 550 °C, the carbon coating and its adsorbed substances gradually oxidize and are removed, which is manifested as a continuous decrease in the sample’s mass. Subsequently, the exposed silicon oxides and magnesium-doped components undergo deep oxidation reactions with oxygen at high temperatures. During this process, the silicon in amorphous SiOx may further oxidize, accompanied by the formation of complex oxides such as magnesium silicates, resulting in an overall increase in the sample’s mass. The results obtained from the two testing methods are consistent. The composition of C@M-SiOx is presented in Table 1. The Mg content was determined by ICP testing, and its content is 8%. Magnesium doping via PVD reveals that the core mechanism of the process is neither a simple silicothermic reduction reaction nor conventional physical vapor deposition. This study infers that the mechanism is a magnesiothermic reduction-driven process that enables magnesiothermic reduction and vaporization in the high-temperature zone. During the heating of the entire system under a vacuum of 0.94 Pa, when the temperature rises to 500–600 °C, the system pressure increases by 460 Pa, indicating that magnesium begins to evaporate while the magnesiothermic reduction reaction (2Mg(g) + SiO2(s)→2MgO(s/l) + [Si]) proceeds simultaneously (Figure S1, Supporting Information). As the temperature further increases, concurrent reactions such as Si(s) + SiO2(s)↔2SiO(g) occur. The generated gaseous magnesium source, active silicon, and SiO(g) (among other species) migrate to the condensation-deposition zone as molecular clusters or metastable vapor phases under the driving force of the temperature gradient, where solid-phase reactions take place at the deposition temperature. Since temperature variations in the reaction zone affect the thermal state of the substrate via thermal radiation and conduction, the actual temperature of the condensation-deposition zone (substrate) changes passively. Thus, the substrate temperature emerges as a key variable influencing silicon grain size. At a relatively low temperature of 1200 °C, the system’s equilibrium saturated vapor pressure is extremely low, M1-SiOx contains silicon crystallites with a size of 2.43 nm, and no silicate precipitation was observed (Figure 1c). At higher temperatures, the saturated vapor pressure increases exponentially with temperature, enhancing the surface diffusion capability of Si atoms deposited on the substrate or preformed nuclei. Here, the growth process of silicon crystals dominates. Similarly to silicon grains, the formed MgSiO3 nuclei also tend to grow via a ripening mechanism at elevated temperatures. Upon heating to 1220 °C, silicon microcrystals and magnesium silicate precipitates formed simultaneously, with the crystallite size in M2-SiOx measured at 3.98 nm. At 1240 °C, the diffraction peaks corresponding to silicon and silicate phases in M3-SiOx become more pronounced, indicating a crystallite size of 5.41 nm. When the synthesis temperature reaches 1260 °C or higher, the material’s surface or interior changes color from black to yellow, the silicon crystallites grow significantly, and the crystallite size of M4-SiOx reaches 6.86 nm. The carbon-coated M-SiOx samples of XRD are presented in Figure 1d. The peaks around 28.5°, 47.0°, and 56.0° are ascribed to crystalline Si domains (PDF 01-077-2107), MgSiO3 (orthoenstatite) manifest at 31° and 35° (PDF 00-019-0768). No distinct diffraction peak characteristic of graphite was observed in the figure, indicating that the carbon formed after high-temperature coating exhibited an amorphous structure. This process did not cause significant damage to the original crystal structure. However, after carbon coating, the silicon crystallites in C@M-SiOx exhibited relative growth compared to those in the uncoated M-SiOx under high-temperature treatment, with sizes of 3.98 nm, 4.87 nm, 5.79 nm, and 8.13 nm, respectively.

Figure 1.

(a) PSD curves of M-SiOx, (b) TG curves of C@M-SiOx, (c) XRD Patterns of M-SiOx and C@M-SiOx, (d) Magnified XRD Patterns of C@M-SiOx, (e) N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of M-SiOx, (f) Raman spectra of C@M-SiOx.

Table 1.

Chemical compositions of C@M-SiOx.

The N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of the materials under diverse silicon crystal conditions was measured (Figure 1e). The SiOx particles exhibit a relatively low BET value of 1.5 m2/g. Subsequent to the magnesium-doped SiOx, an interesting phenomenon was noted: an increase in the size of silicon crystals was accompanied by a corresponding increase in the specific surface area. The measured specific surface area values were 6.2 m2/g, 10.87 m2/g, 19.65 m2/g, 32.21 m2/g, and 41.15 m2/g, respectively. This phenomenon can be attributed to the intricate structural rearrangement and the synergistic evolution of multi-scale pores that occur during the high temperature treatment of the materials. Specifically, during the thermal induction stage, smaller silicon nanocrystals, due to their relatively high surface energy, tend to dissolve. The silicon atoms within these nanocrystals diffuse through the magnesium silicate matrix or the amorphous silicon oxide layer. Significantly, this material migration process does not result in densification. rather, it leaves behind an abundance of intergranular pores at the original positions of the small nanocrystals and forms porous interfacial regions around the larger crystals, thereby significantly augmenting the mesopore volume. Furthermore, the magnesium doping process itself etches and reconstructs the surrounding SiOx matrix, giving rise to new phases such as magnesium silicate. The interfaces between these newly formed phases and silicon crystals typically harbor a substantial number of defects and pores. After the coating process, the BET value of C@M-SiOx was regulated to 5.7 m2/g. Figure 1f depicts the Raman spectra of C@M-SiOx. The characteristic peaks near 300 cm−1, 520 cm−1, and 935 cm−1 correspond to the phonon vibration modes of 2TA(X), F2g, and 2TO(L), respectively [43]. As the preparation temperature increases, the intensity of the characteristic peak near 520 cm−1 increases, the proportion of SiOx components changes, which also indicates that the grain size is increasing. This will directly affect its electrochemical performance. Distinct characteristic peaks emerge at around 1345 cm−1 and 1596 cm−1, these two peaks represent the D-band (sp3-hybridized disordered carbon) and the G-band (sp2-hybridized graphitized carbon) [7]. This indicates that the carbon layers within the material exhibit a high level of both ordered and disordered architectures, thus forming a sophisticated carbonaceous network.

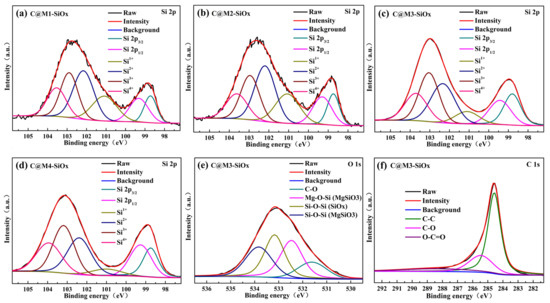

As depicted in Figure 2a–d, the Si 2p spectra of C@M-SiOx exhibit two components: amorphous SiOx and crystalline Si. Amorphous SiOx, respectively, corresponded to Si1+ (101.2 eV), Si2+ (102.5 eV), Si3+ (103 eV), and Si4+ (104 eV) [44], the binding energy peaks at 98.8 eV and 99.5 eV correspond to the two spin orbit components of crystalline Si(Si0), namely Si 2p3/2 and Si 2p1/2, respectively. As shown in Table 2, at different temperatures, the chemical vapor transport and solid-state reaction driven by magnesium thermal reduction indirectly affect the structural evolution of the substrate samples. As silicon atoms continuously precipitate from the amorphous network and undergo crystal growth, the proportion of sub-oxidized silicon species (e.g., Si1+, Si2+) decreases systematically. Concomitantly, the residual matrix becomes progressively oxidized, leading to a corresponding increase in the relative content of Si3+ and Si4+. The concentration of Si1+ is relatively low, making it prone to structural rearrangement or further reaction to transform into more stable Si0 or other intermediate oxides [45]. The binding-energy peak position of Si4+ coincides with the silicon valence states in SiO2 and MgSiO3, further validating the presence of this phase, but Si4+ reacts with Li+ to form the irreversible Li4SiO4, increasing its irreversible capacity and reducing its ICE. Clearly indicating that this material is not a simple homogeneous substance. Instead, it is a complex multiphase composite system consisting of elemental silicon, multiple subsilicon oxides, and magnesium silicate coexisting. As shown in Figure 2e, the dominant peak at 284.5 eV can be ascribed to the C-C bond. This indicates that the coated carbon layer has a relatively high content of sp2-hybridized carbon, which is beneficial for constructing a continuous conductive network. Moreover, signals of oxygen-containing functional groups such as C-O, and O-C=O were detected at 285.5 eV, and 288.6 eV, respectively [46]. These signals likely stem from incomplete pyrolysis of the carbon precursor or oxygen-containing species adsorbed on the surface of the sample. As depicted in Figure 2f, within the O 1s spectral profile, the binding energy peaks at 531.5, and 533.0 eV correspond to the C–O, and Si-O-Si bonds within SiOx, respectively. Meanwhile, the two peaks located at 533.8 eV and 532.3 eV, respectively, correspond to the Si-O-Si bond and the Mg-O-Si bond in MgSiO3. Owing to the distinct chemical environments, the binding energies of the Si–O–Si bonds in SiOx and MgSiO3 are manifested at 533.0 eV and 533.8 eV, respectively [47].

Figure 2.

(a–d) The Si2p spectra of C@M-SiOx, (e) The O1s spectra of C@M3-SiOx, (f) The C1s spectra of C@M3-SiOx.

Table 2.

XPS Si 2p deconvoluted results of C@M-SiOx.

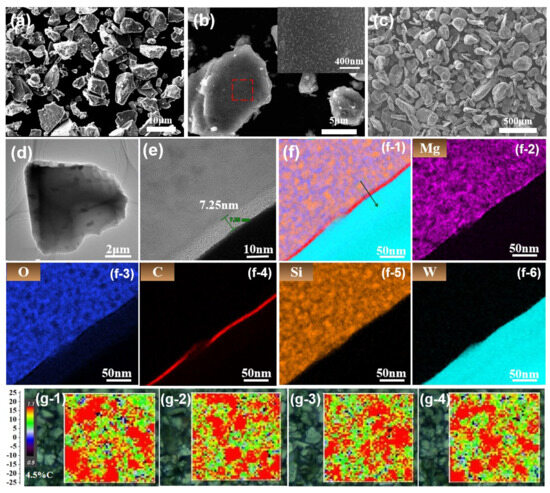

The particle size and morphology of the carbon-coated C@M3-SiOx were examined using SEM. The particle size distribution was relatively uniform from depicted in Figure 3a, with an average size of approximately 6.42 μm, which is 0.4 μm larger than the average particle size of M-SiOx (6.02 μm). This increase in size confirms the presence of a carbon layer on the material surface. Figure 3b illustrates the high-magnification SEM images of C@M3-SiOx. The surface of M3-SiOx particles is entirely encapsulated by a homogeneous carbon layer. This carbon layer is generated through chemical vapor deposition using a mixed gas source of C2H2/CH4 and features a three-dimensional porous architecture. This complete encapsulation structure is conducive to the construction of a dense and continuous conductive network, which promotes multi- point electrical contact among particles. Moreover, the carbon bridges formed between particles further strengthen the connectivity of the conductive pathways. This is beneficial for establishing a stable conductive framework, thus enhancing both the electronic transport ability and structural stability of the material simultaneously. Figure 3c shows the SEM image of magnesium powder. After simple spheroidization treatment, the magnesium powder assumes a granular morphology. Compared with flaky magnesium powder, it is more evenly dispersed when mixed with Si raw materials and exhibits a higher yield in the experimental process. Figure 3d presents the low-magnification TEM morphological image of C@M3-SiOx. Owing to the distinct contrast difference, the characteristic core–shell structure is clearly observable. At high magnification (Figure 3e), a dense carbon layer with uniform thickness is identified, with a measured thickness of approximately 7.25 nm. Figure 2f and its corresponding elemental distribution map present the EDS results of the C@M3-SiOx composite material. The carbon element signal shows a uniform shell structure, which is highly consistent with the dense carbon layer observed in the HRTEM image (Figure 3e), fully confirming the successful construction of the carbon coating and its good uniformity. The silicon and oxygen element signals are co-located within the particles, corresponding to the distribution of the SiOx-based active material. Notably, magnesium (Mg) is uniformly distributed in the core region without obvious segregation, providing direct evidence for the successful doping of Mg into the SiOx matrix (W is the test substrate).

Figure 3.

(a) SEM of C@M3-SiOx, (b) Medium-magnification SEM image of C@M3-SiOx particles (illustration: enlarged image of the red region), (c) SEM image of magnesium powder, (d) TEM of C@M3-SiOx, (e) HRTEM of C@M3-SiOx, (f) EDS elemental mapping of C@M3-SiOx, (g-1–g-4) Raman mapping images of C@M-SiOx(C@M1-SiOx、C@M2-SiOx、C@M3-SiOx、C@M4-SiOx).

Figure 3(f-1–f-6) presents the EDS elemental mapping of the C@M-SiOx sample, demonstrating the uniform distribution of Si, O, Mg, and C throughout the material. These results confirm the successful synthesis of the carbon-coated Mg-SiOx composite. Figure 3(g-1–g-4) depicts the compositional and structural characteristics of the carbon layer on the surface of C@M-SiOx. The results of Raman mapping reveal that the median ratio of ID/IG is 1.1, which was consistent with the results of Raman spectroscopy (Figure 1f). Typically, the ID peak stems from defects or edge states within the graphite lattice, whereas the IG peak corresponds to the symmetric stretching vibration mode of sp2-hybridized carbon atoms [45]. As is evident from the figure, the red and green regions are distributed alternately. The green areas indicate a higher content of long-range ordered graphene in the material, while the red areas are associated with disordered graphene layers, amorphous carbon, and sp3 hybridized carbon structures. These two regions jointly form a conductive layer with a complex network structure, which is in accordance with the SEM image results. This conductive network not only facilitates the rapid intercalation and de-intercalation of lithium ions but also effectively alleviates the stress caused by the volume expansion of silicon particles during the charge–discharge cycle. The four samples demonstrate a high degree of consistency in the structure and composition of the carbon coating, indicating that the properties of the carbon layer possess excellent reproducibility. Consequently, in the subsequent analysis of electrochemical performance, the interference arising from differences in the carbon coating can be eliminated. This enables the effective isolation and independent investigation of the single variable of silicon crystal size.

3.2. Electrochemical Properties of C@M-SiOx

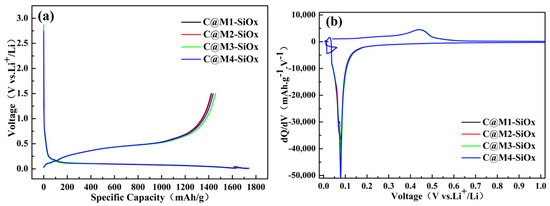

The first-cycle voltage-capacity profiles of C@M-SiOx are presented in Figure 4a. For the C@M-SiOx, as the silicon crystals increase in size, the specific capacities of the four samples were 1418 mAh/g, 1429 mAh/g, 1442 mAh/g and 1431 mAh/g, respectively. The corresponding initial Coulombic efficiencies were 82.01%, 82.94%, 83.33%, and 83.50%. According to the results, both the first-cycle capacity and the ICE increase with increasing silicon crystallite size, indicating that crystalline silicon (c-Si) contributes a higher capacity compared to the amorphous SiOx matrix. As the silicon crystallite size increases, the amount of inactive interfaces (e.g., Si/SiO2 interfaces) decreases, the lithium ion diffusion barrier is reduced, and the alloying reaction becomes more complete, thereby enhancing the overall specific capacity. Under the same carbon content, with more silicon atoms are released from the high oxidation state network during the deposition process, which significantly reduces the irreversible consumption of lithium by the first lithiation active “O” component (Combining the results of XPS analysis: the inert O increases, the Si1+ and Si2+ components decrease, while the Si3+ and Si4+ components increase), which is the main reason for the increase in the first coulombic efficiency. During the subsequent second and third cycles, the electrochemical activation process within the material progressively deepened, while the structure of the SEI film gradually evolved toward greater stability and integrity, leading to a significant reduction in lithium ion consumption. The average Coulombic efficiencies were 97.4% and 97.9%, respectively (Figure S2, Table S1, Supporting Information).

Figure 4.

(a) Voltage–capacity profiles of C@M-SiOx prepared under different silicon microcrystalline structures, (b) initial charge–discharge dQ/dV curves of C@M-SiOx.

Figure 4b shows the dQ/dV curves of C@M-SiOx during the first charge–discharge process. During the lithium-intercalation stage, the alloying reaction of the coating materials occurred below 0.25 V, while the dealloying reaction took place at approximately 0.5 V during charging. The reduction peak observed at 0.1 V corresponds to the lithium insertion process in amorphous silicon. At this stage, Li+ reacted with amorphous silicon to form the LixSi phase. During the first charging process, as the cell voltage increased, a distinct oxidation peak appeared at around 0.45 V [48,49], which corresponds to the lithium extraction process from the C@M-SiOx composite. No clear redox peaks associated with amorphous carbon were observed in the curves, which may be attributed to the overlapping of strong oxidation and reduction peaks from silicon, thereby masking the weaker signals from amorphous carbon. In the first dQ/dV curve, the number of reduction peaks is relatively small. As the cycling proceeds, the electrolyte gradually penetrates, the electrode/electrolyte interface tends to stabilize, and the active centers in the material are gradually activated and participate in multi-step alloying and dealloying reactions. Therefore, in the dQ/dV curves of subsequent cycles, more abundant and stable electrochemical characteristic peaks are presented (Figure S3, Supporting Information). It should be specifically pointed out that within the range of approximately 0.005–0.05 V, the dQ/dV curve shows a voltage hysteresis phenomenon. This is due to the discharge mechanism during the battery testing process. Specifically, after switching from a discharge rate of 0.1 C to 0.01 C, a rest process is introduced. This process leads to the emergence of several discontinuous points with increased voltage at the end of the discharge curve (Figure 4a and Figure S2). The ultra-low current discharge (0.01C) at the final stage enables more complete utilization of the material’s theoretical lithium intercalation capacity, thereby facilitating the evaluation of its maximum capacity potential. Under the conventional discharge mechanism (maintaining 0.1C lithium intercalation), the capacity decreased by 95 mAh/g. The first charge–discharge and its dQ/dV curve are shown in the Supporting Information (Figure S4, Table S2).

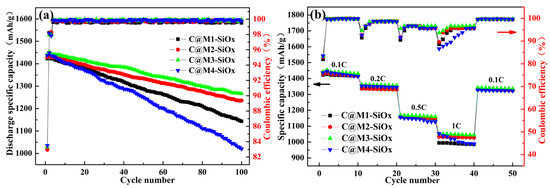

Figure 5a presents the cycling performance and Coulombic efficiency of C@M-SiOx anode materials under different silicon microcrystalline structures. When the silicon crystallite size is 3.98 nm, the relatively strong phase-boundary binding energy between the silicon crystal and the amorphous matrix may lead to Si enrichment [50], which negatively affects cycling stability. The capacity retention rate of C@M1-SiOx is 81.84%. As the silicon crystallite size increases, the combination of amorphous high-Li lithium-silicon phases (a-Li) during charging becomes relatively less significant, resulting in improved cycling performance. The capacity retention rates of C@M2-SiOx and C@M3-SiOx reach 82.54% and 83.82%, respectively. However, the capacity retention rate of C@M4-SiOx is only 75.68%, this is owing to the fact that the interior space of grains with a size of 8.13 nm is conducive to the combination of the amorphous high-Li phase, leading to premature failure of the silicon electrode. By precisely controlling the silicon crystallite size, the electrochemical performance of C@M-SiOx has been improved. Throughout the long-term cycling process, the Coulombic efficiency of the electrodes approaches 99.89%, indicating that the amount of Li+ intercalating and deintercalating between the electrodes is nearly balanced after material activation.

Figure 5.

(a) Comparison of the cycling performance and Coulombic efficiency of C@M-SiOx at 0.1C, (b) Comparison of the rate performance and corresponding coulombic efficiency of C@M-SiOx.

The elastic modulus of the silicate buffer matrix is of pivotal significance in curbing the emergence of internal cracks during the cycling of micron-scale SiOx materials and augmenting their electrochemical properties. Evidenced by research [51], in contrast to Li2SiO3 and MgSiO3 buffer matrices, Mg2SiO4 exhibits a higher elastic modulus and yield strength. Consequently, it can more effectively impede the propagation of cracks induced by silicon volume expansion. Moreover, the Li+ diffusion energy barrier of Mg2SiO4 is lower than those of Li2SiO3 and MgSiO3, which is conducive to the rapid transmission of lithium ions. Based on XRD analysis results, this study meticulously explored the impact of silicon grain characteristics on the electrochemical performance of the materials by manipulating a single variable, specifically setting the buffer matrix as MgSiO3. Therefore, notwithstanding that the achieved electrochemical performance is marginally inferior to the reported values in the literature where MgSiO3 serves as the buffer matrix, this experimental design is instrumental in elucidating the independent contribution of the silicon grain size effect. This, in turn, offers a well-defined research trajectory for optimizing the material structure.

Figure 5b depicts the comparison of the rate performance of C@M-SiOx synthesized at different silicon crystal sizes. Under a current rate of 1C, the capacity of C@M4-SiOx can still be sustained at 1044 mAh/g, whereas that of C@M1-SiOx decays to 980 mAh/g. The silicon electrodes with larger grain sizes demonstrate excellent rate performance. This is because lithium has a higher diffusion rate towards the broader grain boundaries. An increase in grain size exerts a positive influence on the rate performance. Nevertheless, when the Silicon crystal becomes excessively large, the capacity decay rate under high-rate conditions also becomes significant.

When the current density is gradually increased from a low value, during the initial 0.1C stage, the ICE is approximately 83%. Starting from the second cycle, the efficiency stabilizes and remains at a relatively high level. At the onset of each change in the current density, there is a notable decline in efficiency, which subsequently recovers gradually. As the current density increases, the stable Coulombic efficiency plateaus of various samples exhibit a gradually decreasing tendency. Specifically, under the high current density of 1C, as the silicon grain size increases, the number of cycles required for the efficiency to recover to the stable plateau lengthens, indicating a relatively slow kinetic response. The stable SEI film formed by C@M4-SiOx at low current densities may be ruptured due to the rapid intercalation and de-intercalation of lithium ions under high-current-density conditions. This leads to a reduction in interface stability, thereby influencing the rapid recovery and maintenance of its efficiency. In contrast, C@M3-SiOx, owing to its appropriate silicon grain size, not only preserves abundant lithium ion diffusion channels but also effectively alleviates the structural deterioration caused by volume expansion. During the process of current-density variation, it demonstrates superior stability of electrochemical response. It can rapidly re-establish a stable electrode/electrolyte interface under high-current-density conditions and maintain a high Coulombic efficiency. The average efficiency over 10 cycles is 96.32%, which is 4.57% higher than that of C@M4-SiOx. When the test conditions are restored to 0.1C, its Coulombic efficiency shows no significant attenuation and remains stably around 99.69%, indicating excellent reversibility and cycling stability.

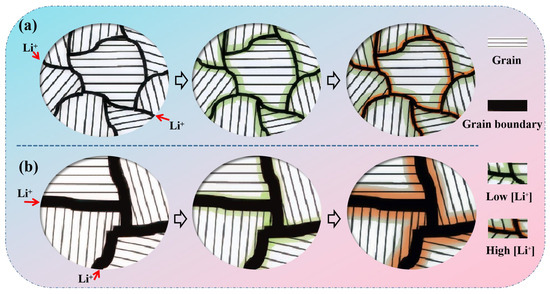

The relationship between grain size and the formation of the amorphous Li-rich (a-Li) phase can be explained as follows (Figure 6). It is assumed that the grain boundary serves as a lithium diffusion channel rather than a lithium storage site. At the initial stage of lithium insertion, lithium ions preferentially diffuse into the grain boundaries, as the activation energy for lithium diffusion into the boundary is lower than that required to enter the grain interior, resulting in the formation of a Li-depleted (lean) a-Li phase along the grain boundary. As lithium insertion progresses, lithium subsequently diffuses from the grain boundaries into the grain interior, independent of surface diffusion from the particle exterior. Meanwhile, due to the high lithium concentration near the grain boundary, silicon with larger grain size is more prone to form an a-Li-rich phase, especially when the grain boundary is relatively wide, which can lead to greater strain accumulation. In contrast, a smaller grain size can effectively suppress the formation of the a-Li-rich phase and thereby enhance the cycling stability of the material. It is important to note that this schematic diagram is speculative and lacks direct in situ experimental evidence for validation. A brief discussion can be conducted by referencing the limitations of Figure 7.

Figure 6.

Schematic of a Li storage process into (a) Small grain particle and (b) Large grain particle.

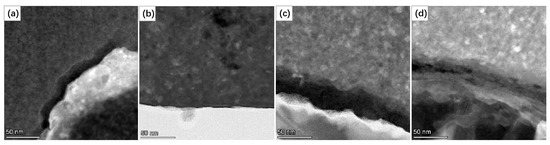

Figure 7.

STEM (DF-I) micrographs of C@M-SiOx: (a) C@M1-SiOx, (b) C@M2-SiOx, (c) C@M3-SiOx, (d) C@M4-SiOx.

Figure 7 depicts the STEM dark-field images (DF-I) of magnesium-doped SiOx with varying grain sizes. This figure showcases the microstructure of magnesium (Mg)-doped non-stoichiometric silicon oxide (SiO2) materials. The image contrast (the contrast between black and white) predominantly arises from differences in crystal orientation (diffraction conditions). The bright white regions correspond to grains that satisfy the Bragg diffraction conditions. The image vividly exhibits a distinct black-and-white contrast. Among them, the uniformly sized and well-defined white bright spots are nanocrystals formed subsequent to magnesium doping. These nanocrystals are evenly embedded within the gray-black amorphous SiO2 matrix, thereby forming a typical “nanocrystal-amorphous” composite structure. As the grain size increases, the entire gray-black region gradually transforms into a white area. This visually confirms that magnesium doping effectively triggers the precipitation of nanoscale grains in the SiOx materials and enables precise control over the grain size. The STEM characterization further validates the above findings.

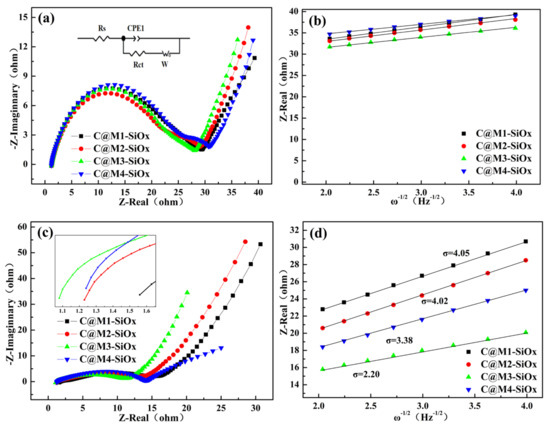

The Nyquist diagrams of C@M1-SiOx, C@M2-SiOx, C@M3-SiOx, and C@M4-SiOx are presented in Figure 8a. The first intercept on the Z-Real axis corresponds to the electrolyte resistance (Rs), the second semicircle in the medium-frequency region is attributed to the charge transfer resistance (Rct), and the sloping line in the low-frequency region is associated with the lithium ion diffusion impedance (W) within the bulk electrode [52,53]. The EIS data, obtained by fitting the corresponding equivalent circuit model using Zview 3.5 software, are summarized in Table 3. For samples with different silicon crystallite sizes, the values of Rs and Rct are slightly different, but not significantly. After the 100th cycle, the Rct value significantly decreased (Figure 8c). We speculate that this is mainly attributed to the formation of irreversible phases (such as lithium oxide and lithium silicate) in the core of the active material, which not only act as a buffering matrix to alleviate volume changes but also enhance the ionic conductivity; meanwhile, the electrode/electrolyte interface likely attains a more stable state and undergoes optimization, thereby facilitating the interfacial charge transfer kinetics.

Figure 8.

(a) Nyquist plots of C@M-SiOx after 2nd cycle, (b) Warburg factor analysis after 2nd cycle, (c) Nyquist plots of C@M-SiOx after 100th cycle, (d) Warburg factor analysis after 100th cycle.

Table 3.

Comparison of impedance fitting data of C@M-SiOx prepared under different silicon crystal conditions before and after cycling.

The plot of Z-Real versus the square root reciprocal of the lower angular frequencies (ω−1/2) is presented in Figure 8b. The calculated values of σ (interfacial resistance) and D (diffusion coefficient) are summarized in Table 3. Among all samples, the C@M4-SiOx electrode exhibits the highest diffusion coefficient (DLi+) of 1.95 × 10−10 cm2·s−1, significantly higher than those of the other three electrodes. This is because magnesium doping inherently modifies the material composition and microstructure of SiOx, forming inert lithium magnesium silicate phases. These phases not only preserve the structural integrity of the material but also generate pathways at phase interfaces that facilitate Li+ migration. Additionally, magnesium doping regulates the oxygen content and the distribution of active silicon. After 100 cycles, with the exception of C@M3-SiOx, the decrease of DLi+ is likely attributable to the progressive degradation of the material’s bulk structure (Figure 8d). For silicon with high crystallinity, its intrinsic electronic conductivity is favorable, potentially contributing to a higher initial DLi+. However, larger grain sizes tend to drive more complete phase separation, rendering the residual SiOx matrix composition closer to SiO2. Given that SiO2 inherently exhibits extremely low ionic and electronic conductivities, coupled with the formation of the inert MgSiO3 buffer phase, silicon grains are effectively encapsulated within a poorly conductive “insulating shell”, with a concomitant reduction in buffering capacity. During cycling, the pronounced volume expansion/contraction of silicon grains is more prone to inducing interfacial delamination between the grains, the matrix, and the carbon layer, thereby triggering a degradation of electrochemical performance. This mechanism accounts for the significant post-cycling decline in DLi+. In contrast, C@M3-SiOx displays incomplete phase separation, forming a nanocomposite architecture consisting of strongly coupled silicon nanocrystals and a sub-oxidized silicon-rich SiOx matrix. This structure integrates moderate ionic conductivity with a favorable elastic modulus, which not only facilitates efficient lithium ion transport but also effectively mitigates stress accumulation during cycling, providing a robust structural and chemical foundation for its exceptional cycling stability.

Micron-scale SiOx serves as a highly promising anode material for lithium-ion batteries, holding great potential in a wide range of applications. Elemental doping, recognized as an effective modification approach, can remarkably improve the ICE and cycling stability of SiOx materials. This is achieved by transforming the SiO2 component into an electrochemically inert silicate buffer matrix. Table 4 presents a comprehensive summary of the typical research advancements regarding Mg-doped SiOx anode materials in recent years. Existing literature has thoroughly investigated the impacts of various factors on material performance, including the Mg doping level, macroscopic particle size, the type and structure of the inert silicate buffer matrix, the carbon coating content, and the coating process. It should be noted that all these factors have the potential to indirectly modulate the size of silicon crystal within the matrix. However, there is currently a lack of systematic research on the size effect of silicon crystal. In this paper, with the premise of keeping the macroscopic particle size, magnesium doping amount, the type and structure of the silicate buffer matrix, and the carbon content constant, the study primarily examines the influence of different silicon grain states on electrochemical performance. Based on this investigation, the optimal range of silicon grain size within this system is thereby determined. The findings of this study clearly indicate that precisely controlling the silicon grain size is of paramount importance for optimizing the overall electrochemical performance of C@M-SiOx composite materials.

Table 4.

Recent representative advances in research on Mg-doped SiOx anode materials.

4. Conclusions

Through precise process control, magnesium doped SiOx materials with similar macroscopic particle size distributions were synthesized. During the coating process, the coating amount was kept constant to ensure the consistency of the structure and composition of the coating layer. This approach was designed to solely investigate the impact of different silicon crystal states on the performance. The study revealed that when the silicon crystal grain size was lower than 3.98 nm, the grain boundary binding energy within the amorphous matrix was relatively high. This led to silicon enrichment, which had an adverse effect on the cycling performance. When the grain size was 5.79 nm (within the range of 4.5 to 6.5nm), the formation of lithium-rich lithium-silicon alloy phases during lithiation was suppressed. As a result, the strain within the active material was reduced, and the cycling stability was enhanced. When the silicon crystal size reached 8.13 nm and above, larger silicon grains tended to facilitate the formation of lithium-rich lithium-silicon alloy phases, thereby degrading the cycling performance of the electrode. Additionally, Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) analysis demonstrated that smaller silicon grains might impede the diffusion of lithium ions due to their narrow grain boundaries. In contrast, silicon electrodes with larger grains exhibited more excellent rate performance, which could be ascribed to the enhanced Li+ diffusion in wider grain boundaries. Consequently, precise control over the silicon crystal grain size can optimize the electrochemical performance of C@M-SiOx composite materials.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/physchem6010004/s1, Figure S1: Temperature Profile of the Preparation Process (Example of 1200 °C Constant Temperature, with Pressure Curve); Figure S2: Voltage-Capacity Profiles of C@M-SiOx; Figure S3: dQ/dV Curves of C@M-SiOx; Figure S4: Voltage-Capacity Profiles of C@M-SiOx; Table S1: The de-lithiation specific capacity, lithiation specific capacity and Coulombic efficiency of the C@M-SiOx sample during the first three cycles; Table S2: Comparison of initial capacity and efficiency under the conventional charge-discharge mechanism (0.1C); Table S3: Performance comparison of SiOx-based materials obtained via different preparation methods and modification techniques.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L. and B.Z.; formal analysis, J.L.; investigation, J.L.; resources, B.Z.; data curation, J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.; writing—review and editing, J.L., J.S., C.B., X.L. and B.Z.; visualization, J.L.; supervision, J.S. and B.Z.; project administration, J.S. and B.Z.; funding acquisition, J.S. and B.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia (2020ZD17), the Basic Research Funds for Universities Directly under Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (No. 2023QNJS018) and the Basic Research Funds for Universities Directly under Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (No. 2023YKJX007).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. For additional Data supporting reporting results are available by request: 2019015003@stu.imust.edu.cn (J.L.), chaoke@imust.edu.cn (C.B.), 2021011006@stu.imust.edu.cn (X.L.).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, Z.J.; Du, M.J.; Liu, P.F.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Q.J.; Sun, H.L.; Sun, Q.J.; Wang, B. Exploring the Influence of Oxygen Distribution on the Performance of SiOx Anode Materials. J. Power Sources 2025, 625, 235720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.J.; Tan, X.; Shi, Z.Z.; Peng, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhong, Y.R.; Wang, F.X.; He, J.R.; Zhu, Z.; Cheng, X.B.; et al. SiOx Based Anodes for Advanced Li-Ion Batteries: Recent Progress and Perspectives. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2414714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.K.; Oh, S.M.; Park, E.; Scrosati, B.; Hassoun, J.; Park, M.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, H.; Belharouak, I.; Sun, Y.K. Highly Cyclable Lithium-Sulfur Batteries with a Dual-Type Sulfur Cathode and a Lithiated Si/SiOx Nanosphere Anode. Nano Lett. 2020, 15, 2863–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, K.; Park, H.; Ha, J.; Kim, Y.T.; Choi, J. Dual-Carbon-Confined Hydrangea-Like SiO Cluster for High-Performance and Stable Lithium Oon Batteries. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2021, 101, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, X.; Fu, C.K.; Li, R.L.; Du, C.Y.; Gao, Y.Z.; Yin, G.P.; Zuo, P.J. High Performance SiOx Anode Enabled by AlCl3-MgSO4 Assisted Low-Temperature Etching for Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Power Sources 2023, 557, 232537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Z.X.; Fu, R.S.; Ji, J.J.; Feng, Z.Y.; Liu, Z.P. Unveiling the Effect of Surface and Bulk Structure on Electrochemical Properties of Disproportionated SiOx Anodes. ChemNanoMat 2020, 6, 1127–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, D.; Yang, L.; Lv, D.; Song, R.; Liu, J.; Hu, W.; Zhong, C. Preparation of SiOx Anode with Improved Performance Through Reducing Oxygen Content, Controlling SiO2 Crystallization, and Carbon-Coating. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2025, 29, 2933–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.H.; Shi, L.K.; Lang, Z.M.; Jia, G.X.; Lan, D.W.; Cui, Y.F.; Cui, J.L. Selenium Element Doping to Improve Initial Irreversibility of C/SiOx Anode in Lithium-Ion Batteries. Electroanal. Chem. 2025, 977, 118878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.Y.; Huang, Z.; Fu, F.B. Enhancing Lithium Storage Performance of Carbon/SiOx Composite via Coating Edge-Nitrogen-Enriched Carbon. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 91, 1355–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Y.; Kang, T.X.; Li, S.F.; Ma, Z.; Nan, J.M. A Temperature-Controlled Chemoswitching Aqueous Binder and In Situ Binding Strategy for Stabilizing SiOx Anodes of Lithium-Ion Batteries. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 17855–17868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Liu, J.; Zhong, C.; Hu, W.B. Mg-Doped, Carbon-Coated, and Prelithiated SiOx as Anode Materials with IImproved Initial Coulombic Efficiency for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Carbon Energy 2024, 6, e421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Jo, S.; Na, I.; Oh, S.M.; Jeon, Y.M.; Park, J.G.; Koo, B.; Hyun, H.; Seo, S.; Lee, D.; et al. Homogenizing Silicon Domains in SiOx Anode During Cycling and Enhancing Battery Performance via Magnesium Doping. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 52202–52214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Jiang, T.T.; Chen, G.Z. Mechanisms and Product Options of Magnesiothermic Reduction of Silica to Silicon for Lithium-Ion Battery Applications. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 9, 651386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.X.; Zhao, Y.M.; Chen, H.X.; Lu, Z.Y.; Tian, Y.F.; Xin, S.; Li, G.; Guo, Y.G. Reduced Volume Expansion of Micron-Sized SiOx via Closed-Nanopore Structure Constructed by Mg-Induced Elemental Segregation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202401973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.X.; Du, X.F.; Liu, T.; Zhuang, X.C.; Guan, P.; Zhang, B.Q.; Zhang, S.H.; Gao, C.H.; Xu, G.J.; Zhou, X.H.; et al. Robust and Fast-Ion Conducting Interphase Empowering SiOx Anode Toward High Energy Lithium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2024, 14, 2302899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.L.; Song, R.F.; Wan, D.Y.; Ji, S.; Liu, J.; Hu, W.B.; Zhong, C. Magnesiothermic Reduction SiO Coated with Vertical Carbon Layer as High-Performance Anode for Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Energy Storage 2024, 99, 113440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, F.; Min, X.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.G.; Huang, Z.; Mi, R.; Fang, M. Recent research progress in modification strategies of silicon oxide-based anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. J. Energy Storage 2025, 127, 117132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.; Lassi, U.; Srivastava, V.; Tuomikoski, S. A review of silicon-carbon anode materials: The role of precursor and its effect on lithium-ion battery performance. J. Power Sources 2025, 641, 236879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Dong, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Zeng, X.; Yuan, Y.; Lu, J. Fundamental Understanding of the Low Initial Coulombic Efficiency in SiOx Anode for Lithium-Ion Batteries: Mechanisms and Solutions. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2405751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Li, J.; Zhao, Q.; Huang, X.; Jia, S.; Ma, J.; Ren, Y. Si-based anodes: Advances and challenges in Li-ion batteries for enhanced stability. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 2024, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zhou, J.; Wang, J.; Pathiranage, S.; Oncel, N.; Robert Ilango, P.; Zhang, X.; Mann, M.; Hou, X. In situ synthesis of graphene-coated silicon monoxide anodes from coal-derived humic acid for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2101645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, Y.; Ren, Y.; Mu, T.; Yin, X.; Du, C.; Huo, H.; Cheng, X.; Zuo, P.; Yin, G. Engineering molecular polymerization for template-free SiOx/C hollow spheres as ultrastable anodes in lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2101145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, N.; Liu, Z.; Shen, B.; Shao, W.; Wang, T.; Zhao, H.; Wang, J.; Chen, Q.; Luo, J.; Liu, Y.; et al. Carbon and MXene Dual Confinement and Dense Structural Engineering Toward Construct High Performance Micron-SiOx Anode for Li-Ion Batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2410839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Shen, H.; Ge, J.; Tang, Q. Improved cycling performance of SiOx/MgO/Mg2SiO4/C composite anode materials for lithium-ion battery. Appl. Appl. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 546, 148814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, Y.; Qian, Y.; Sun, S.; Lin, N.; Qian, Y. Deficient TiO2−x coated porous SiO anodes for high-rate lithium-ion batteries. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2023, 10, 1176–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Dong, Y.; Liu, C.; Feng, X.; Jin, H.; Ma, X.; Ding, F.; Li, B.; Bai, L.; Ouyang, Y.; et al. Design and synthesis of high-silicon silicon suboxide nanowires by radio-frequency thermal plasma for high-performance lithium-ion battery anodes. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 614, 156235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Tang, W.; Yang, Y.; Lai, G.; Lin, Z.; Xiao, H.; Qiu, J.; Wei, X.; Wu, S.; Lin, Z. Engineering prelithiation of polyacrylic acid binder: A universal strategy to boost initial coulombic efficiency for high-areal-capacity Si-based anodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2206615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Kong, L.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X. Bamboo-like SiOx/C nanotubes with carbon coating as a durable and high-performance anode for lithium-ion battery. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 428, 131060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; An, X.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, N.; Deng, J.; Peng, H.; Li, X.; Lei, Z. Boosting Conversion of the Si–O Bond by Introducing Fe2+ in Carbon-Coated SiOx for Superior Lithium Storage. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 39482–39494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wei, X.; Lai, G.; Chen, H.; Wu, S.; Luo, D.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, S. Boosting lithium storage of SiOx via a dual-functional titanium oxynitride-carbon coating for robust and high-capacity lithium-ion batteries. Sci. China Mater. 2024, 67, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, J.; Yuan, H.; Liu, J.; Zhao, N.; Hu, W.; Zhong, C. Amorphous AlPO4 layer coating vacuum thermal reduced SiOx with fine silicon grains to enhance the anode stability. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2405116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.B.; Zhao, L.; Ma, Z.F.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.S.; Lu, Z.Y.; Li, G.; Luo, X.X.; Wen, R.; Xin, S.; et al. Vertically Fluorinated Graphene Encapsulated SiOx Anode for Enhanced Li+ Transport and Interfacial Stability in High-Energ-Density Lithium Batteries. Angew. Chem. 2024, 136, e202413600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Xu, P.; Liao, M.; Lu, X.; Shen, G.; Zhong, C.; Zhang, M.; Huang, Q.; Su, Z. Amorphous SiO2 nanoparticles encapsulating a SiO anode with strong structure for high-rate lithium-ion batteries. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2024, 7, 774–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yan, Z.; Yi, S.; Jiang, J.; Yang, D.; Du, N. Regulation of Si nanodomain size and its effect on electrochemical performance in prelithiated SiO anode. J. Power Sources 2023, 570, 233021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Jung, J.Y.; Lee, C.H.; Kim, B.G.; Choi, J.H.; Park, M.S.; Lee, S.M. Swelling-Controlled Double-Layered SiOx/Mg2SiO4/SiOx Composite with Enhanced Initial Coulombic Efficiency for Lithium-Ion Battery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 7161–7170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.H.; Huang, Y.; Xie, Y.Y.; Du, X.P.; Chen, C.; Zhou, J.H.; Bi, Z.; Xuan, X.D.; Guo, Y.C.; Tang, Y.; et al. Tuning the Stable Interlayer Structure of SiOx-Based Anode Materials for High-Performance Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Mater. Sci. 2025, 60, 8449–8463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.Z.; Shea, J.; Liu, J.X.; Hagh, N.M.; Nageswaran, S.; Wang, J.; Wu, X.Y.; Kwon, G.; Son, S.B.; Liu, T.C.; et al. Comparative Study of Vinylene Carbonate and Lithium Difluoro(oxalate)borate Additives in a SiOx/Graphite Anode Lithium-Ion Battery in the Presence of Fluoroethylene Carbonate. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 7648–7656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.F.; Di, J.; Lv, D.; Yang, L.L.; Luan, J.Y.; Yuan, H.Y.; Liu, J.; Hu, W.B.; Zhong, C. Improving the Electrochemical Properties of SiOx Anode for High-Performance Lithium-Ion Batteries by Magnesiothermic Reduction and Prelithiation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 7849–7859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bie, X.; Dong, Y.W.; Xiong, M.; Wang, B.; Chen, Z.X.; Zhang, Q.C.; Liu, Y.; Huang, R.H. Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Matrix to Optimize Cycling Stability of Lithium Ion Battery Anode from SiOx Materials. Inorganics 2024, 12, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, G.Y.; Yang, H.X.; Geng, X.B.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, C.T.; Huang, L.Q.; Luo, X.T. Three-Dimensional Porous Si@SiOx/Ag/CN Anode Derived from Deposition Silicon Waste toward High-Performance Li-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 43887–43898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, K.; Jeon, S.; Ko, D.S.; Jung, I.S.; Kim, J.H.; Ito, K.; Kubo, Y.; Takei, K.; Saito, S.; Cho, Y.H.; et al. Evolving Affinity Between Coulombic Reversibility and Hysteretic Phase Transformations in Nano-Structured Silicon-Based Lithium-Ion Batteries. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domi, Y.; Usui, H.; Sugimoto, K.; Sakaguchi, H. Effect of Silicon Crystallite Size on Its Electrochemical Performance for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Energy Technol. 2019, 7, 1800946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhu, C.; Chen, S.; Chen, K. Effect of ball-milling reaction between ethanol and Si on the electrochemical performance of silicon anodes for Lithium-ion batteries. J. Energy Storage 2025, 139, 118804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.M.; Choi, W.; Hwa, Y.; Kim, J.H.; Jeong, G.; Sohn, H.J. Characterizations and electrochemical behaviors of disproportionated SiO and its composite for rechargeable Li-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. 2010, 20, 4854–4860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Zhao, H.X.; Niu, Y.B.; Zhang, S.Y.; Wu, Y.B.; Yan, H.J.; Xin, S.; Yin, Y.X.; Guo, Y.G. Insights into the pre-oxidation process of phenolic resin-based hard carbon for sodium storage. Mater. Chem. Front. 2021, 5, 3911–3917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaznova-Herzog, V.P.; Nesbitt, H.W.; Bancroft, G.M.; Tse, J.S. Characterization of leached layers on olivine and pyroxenes using high-resolution XPS and density functional calculations. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2008, 72, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhan, O.; Umirov, N.; Lee, B.M.; Yun, J.S.; Choi, J.H.; Kim, S.S. A Facile Carbon Coating on Mg-Embedded SiOx Alloy for Fabrication of High-Energy Lithium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 9, 2201426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghassemi, H.; Au, M.; Chen, N.; Heiden, P.A.; Yassar, R.S. In Situ Electrochemical Lithiation/Delithiation Observation of Individual Amorphous Si Nanorods. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 7805–7811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, M.T.; Ryu, I.; Lee, S.W.; Wang, C.M.; Nix, W.D.; Cui, Y. Studying the Kinetics of Crystalline Silicon Nanoparticle Lithiation with In Situ Transmission Electron Microscopy. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 6034–6041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.H.; Xiao, X.; Verbrugge, M.W.; Sheldon, B.W. Influence of Oxygen Content on the Structural Evolution of SiOx Thin-Film Electrodes with Subsequent Lithiation/Delithiation Cycles. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5, 13293–13306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.F.; Li, G.; Xu, D.X.; Lu, Z.Y.; Yan, M.Y.; Wan, J.; Li, J.Y.; Xu, Q.; Xin, S.; Wen, R.; et al. Micrometer-Sized SiMgyOx with Stable Internal Structure Evolution for High-Performance L-Ion Battery Anodes. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2200672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Li, J.Y.; Sun, J.K.; Yin, Y.X.; Wan, L.J.; Guo, Y.G. Watermelon-Inspired Si/C Microspheres with Hierarchical Buffer Structures for Densely Compacted Lithium-Ion Battery Anodes. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1601481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.L.; Zhao, H.L.; Lv, P.P.; Zhang, Z.J.; Zhang, Y.; Du, Z.H.; Teng, Y.Q.; Zhao, L.N.; Zhu, Z.M. Watermelon-Like Structured SiOx-TiO2@C Nanocomposite as a High-Performance Lithium-Ion Battery Anode. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1605711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, T.; Zhou, F.; He, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, H.; Liu, Y.; Yu, X.; Gao, B.; Chu, P.K.; Huo, K. Modulus-Engineered Silicates-Buffering Matrix for Enhanced Lithium Storage of Micro-Sized SiOx Anodes. Small Methods 2025, 2500556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.