Abstract

The Eurasian Griffon Vulture (Gyps fulvus) is the most abundant obligate scavenger in Europe. It depends on wild and domestic carcasses whose availability and location are relatively unpredictable in terms of space and time, but also on predictable sources of anthropogenic origin. In this study, satellite and accelerometer data from 10 adult individuals captured in the Basque Country (N Spain) were analysed with the aims of identifying feeding sites and determining the types of resources used. The annual cycle of the species was subdivided into three phases: pre-laying and incubation (December–March), rearing (April–July) and post-rearing (August–November). Our results showed that 64% of trophic resources were consumed in mountain pastures and on extensive or semi-extensive livestock farms, highlighting the importance of these farming systems for the species in the study area. However, 36% of the resources were exploited in more predictable anthropic environments, such as landfills and supplementary feeding stations and, to a much lesser extent, intensive farms. Individual variability was detected in terms of trophic behaviour. On semi-extensive farms, the most consumed carcasses were sheep (48%) and horses (37%), while on intensive farms, it was pigs (81%). During the pre-laying and incubation phase, feeding events detected in landfills were reduced, with vultures focusing on resources close to the colony. We observed that the population studied differed from other Spanish populations in its greater use of trophic resources from extensive and semi-extensive livestock farms, as expected from their spatial-temporal distribution and local availability.

1. Introduction

Obligate scavenger birds constitute a functional group that provides highly relevant ecosystem services by recycling necromass and nutrients, thereby contributing to reducing pathogen transmissibility, the prevalence of epizootics and the abundance of mesopredators in the environment [1,2,3]. In this regard, although the regulatory service they perform through the efficient consumption of vertebrate carcasses has been highlighted frequently [4,5,6], other benefits have also been described, such as the reduction in economic costs and greenhouse gas emissions associated with the transport and destruction of carcasses [7,8]. In addition, cultural services through ecotourism, linked to birdwatching activities in mountain environments, have also been quantified, providing important economic benefits to areas inhabited by avian scavengers [9,10].

Within the group of obligate avian scavengers in Europe, the Griffon Vulture is the most abundant species [11,12]. This long-lived species is a colonial breeder on rocky cliffs and exploits resources on a very large spatial scale [13,14], so that the conservation of its populations and of the above mentioned services often requires transboundary approaches [6,15,16]. The Griffon Vulture breeds throughout the southern Palearctic, including north-western Africa, southern Europe, the Middle East and Central Asia [17]. Although the global population size of this species is not well known, the European population has been better quantified (70,000–90,000 mature individuals [18]), with approximately 90% (31,000–37,000 pairs) breeding in Spain [19].

Many Griffon Vulture populations have experienced prolonged declines and even regional extinctions, especially in Africa, South-eastern Europe, the Middle East and Asia [20,21]. In Western Europe, the population size of the species declined significantly during the second half of the 20th century but subsequently recovered and is currently classified as a species of ‘least concern’ on the IUCN Red List [21]. As with other long-lived raptor species, the main determinant of population growth and stability for this species is adult survival [22,23].

The Griffon Vulture’s diet is based mainly on the carcasses of medium-to-large domestic and wild ungulates [24,25,26], although it also covers part of its trophic needs in open landfills, where birds feed on organic rubbish [27,28,29]. In Spain, over the last two decades, there has been a drastic reduction in the food supply for the species due to the implementation of sanitary regulations and the consequent removal of livestock carcasses from the countryside [29,30,31], as well as the progressive reduction in extensive livestock farming in many regions [32,33]. To address this trophic deficit, more flexible regulations were enacted, allowing livestock carcasses to be left accessible to scavenger birds in specific areas [30], if certain requirements are met on the farms of origin (Regulation EC/1069/2009, Regulation EU/142/2011 and Royal Decree 1632/2011).

However, the consequences of these restriction-mitigation processes for the demographics of Griffon Vulture populations have not been clearly evident [27,34]. Although the installation of supplementary feeding stations (predictable in space and time) has traditionally been considered a tool for the conservation of avian scavengers in general and griffon vultures in particular [35], some studies have described negative effects [15,36]. In general, the relative importance of these predictable feeding points for griffon vulture populations has not been characterised regarding more natural trophic availability conditions linked to livestock activities [37]. Given the lack of information, identifying and quantifying the main food sources of griffon vultures would contribute to: (1) improving knowledge about the pressures on their populations arising from variations in the availability of trophic resources, (2) modulate the application of conservation measures such as supplementary feeding, (3) rationalise and optimise the management of livestock by-products, and (4) describe in detail the regulatory ecosystem services provided by the species.

Most studies on the diet of the Griffon Vulture have been based on direct field observations, pellet and isotope analysis, with restricted spatial scope, so knowledge of the trophic niche and its possible intra- and inter-population variations is limited [24,27,38]. Consequently, a lack of heterogeneity and specialisation regarding the Griffon Vulture diet has been traditionally assumed [39]. The recent use of GPS satellite transmitters and accelerometry is allowing more complete data to be obtained on the foraging ecology of this species, opening up the possibility of investigating its diet in a more systematic and meaningful way [26,39]. In this study, we analysed positional data provided by GPS/GPRS-GSM transmitters placed on 10 griffon vultures, with the aim of identifying individual feeding events and classifying them according to the type of resource used. Considering the local abundance of livestock and the predominant extensive farming systems in the study area, which provide accessible carcasses, we hypothesised that the population studied mainly uses trophic resources from nearby livestock farms. This would be associated with relatively limited home ranges, because vultures would not need to travel long distances to forage and meet their energetic requirements.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Species and Capture Site

The individuals were captured in the Aizkorri-Aratz Natural Park (42°59′ N, 2°25′ W; Basque Country, Northern Spain; Figure 1). The census in 2018 yielded 860–875 breeding pairs for the regional population in the Basque Country, and 126 for the five specific colony sites at Aizkorri-Aratz [19]. This protected area of 19,500 ha comprises a group of mid-elevation mountain ranges (maximum altitude 1550 m). The climate is Atlantic, with annual rainfall of around 1100–1300 mm. The terrain is predominantly rugged, with a good supply of limestone outcrops. Forests cover 65% of the area, but the upper mountain sector comprises large pasturelands (5500 ha) that are used for grazing sheep, cattle and horses, with an authorised livestock population in 2022 of 11,550 sheep, 1266 mares, 1041 cows and 204 goats, staying there mainly between April and December [40].

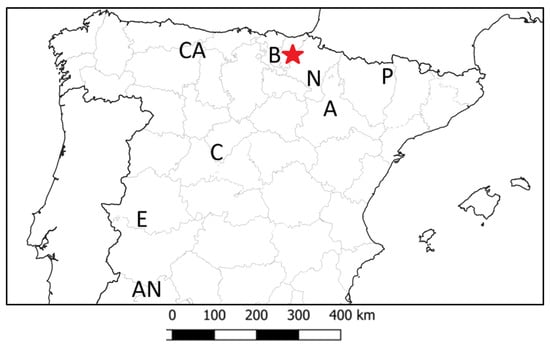

Figure 1.

Map of Spain indicating provincial divisions and the administrative and geographic regions mentioned in the text. The red star marks the capture site of the ten griffon vultures tagged with GPS/GPRS-GSM transmitters. B (Basque Country), N (Navarre), A (Aragón), C (Castile), E (Extremadura), AN (Andalusia), CA (the Cantabrian mountains) and P (the Pyrenees). A graphical scale (km) is shown.

2.2. Data Collection

The griffon vultures were captured in June 2019 using a portable cage (4.5 × 7 × 1.7 m) with a self-locking door made of tilting metal rods. The trap was set up 1 km from the largest colony in the study area. The individuals were equipped with OrniTrack-50 GPS/GPRS-GSM 50 g transmitters (https://www.ornitela.com/50g-transmitter, accessed on 1 November 2025), with an accelerometer sensor and solar panel charging. The devices were programmed to store GPS positions every 10 min when the battery charge remained >75%, every hour if it was between 50 and 75%, and every 3 h if it fell <50%, to reduce energy demand and prevent discharge. Between sunset and sunrise, position acquisition was programmed every three hours. The vultures were ringed with metal and PVC rings, although two of them had been wearing remote-readable wing bands since 2017. The individuals were sexed using molecular techniques [41], resulting in 11 males and 1 female.

The period analysed extended from 1 July 2019 to 30 June 2022. Two griffon vultures died during this interval, so complete data were available for 10 individuals. To assign an annual reproductive status to each specimen, the tri-axial values ‘x’, ‘y’, ‘z’ of the accelerometer were reviewed through the Ornitrack control panel (https://www.glosendas.net/cpanel/, accessed on 1 November 2025) in order to detect periods of inactivity lasting at least 48 h during the breeding period and at suitable nesting sites, which were interpreted as being linked to the incubation process. Both sexes of the species incubate and different studies have quantified individual incubation sessions ranging from 12 h to 6 days, with average values of 35 h [17]. Therefore, our 48 h threshold seems to be a reliable indicator of this behaviour.

2.3. Identification of Potential Feeding Events (PFEs)

Using a Geographical Information System (GIS) modelling, successive filtering criteria were applied to the data obtained. Thus, all positions with low satellite accuracy (HDOP > 3.0) were eliminated. Data collected with a battery charge <50% were also eliminated, since under these conditions the interval programmed for the acquisition of successive GPS positions was >2 h. Records corresponding to night-time rest between 18:00 and 09:00 (UTC time) were also excluded, because Griffon Vultures only forage during daylight, except under extraordinary circumstances [6,42]. Feeding activity was considered if the instantaneous ground speed was ≤7 km/h. This attribute was available in the GPS dataset as a discrete quantitative variable, so a conservative threshold was applied to identify vultures on the ground, either standing passively near a carcass or making short bursts of running or hopping towards it while interacting aggressively with other vultures. Some studies have defined non-static positions (i.e., flight) as cases where instantaneous ground speed exceeds 14 km/h [43], so our threshold is reasonable. By spatially overlapping the 1:2500 scale SIGPAC 2024 land use layer from the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/agricultura/temas/sistema-de-informacion-geografica-de-parcelas-agricolas-sigpac-/default.aspx, accessed on 1 November 2025), the positional data lying inside areas classified as ‘watercourse and water surface’, ‘road or path’, ‘urban’ and ‘forest’ were eliminated, assuming that carcasses deposited in these locations are not accessible to griffon vultures. In the case of the ‘forest’ class, it was assumed that the visibility of carcasses for a prospecting vulture is severely reduced [6,44]. Points located on rocky cliffs were also excluded by overlapping orthophotos and 1:1000 scale slope maps (https://pnoa.ign.es/pnoa-imagen/visualizadores-y-servicios-web; https://www.geo.euskadi.eus/geobisorea, accessed on 1 November 2025), considering that they corresponded to sites used for resting. Finally, points associated with bathing and plumage cleaning activities were excluded, as they coincided with watering holes, springs, ponds and pools [26]. These were filtered using a GIS layer of livestock watering holes produced by Hazi Foundation (http://www.lifeorekamendian.eu/documentacion/?csrt=2400701700404959943, accessed on 1 November 2025) and through manual review of orthophotos.

Once the above filters were applied, a PFE was identified when the individual had remained in the same place for >20 consecutive minutes. This conservative criterion was adopted because it corresponds to the average time spent by an individual at a given carcass in 100 monitored events at supplementary feeding stations [45], whereas other researchers have used 15 min as a minimum time [26]; shorter feeding events are very infrequent [43]. Therefore, if the transmitter battery was >75% charged, a feeding event was identified if there was a cluster of at least three temporally consecutive points separated by <100 m between them; if the battery charge was between 50–75%, at least two temporally consecutive points with the same spatial separation were clustered. Each group of points representing a PFE was summarised by its centroid. Subsequently, to increase the independence of the events, if two PFEs were separated temporally by <4 days between them and spaced <1 km, they were considered as one.

2.4. PFE Categorisation

The locations where the identified feeding events took place were classified into five categories:

- Mountain pasture, usually on communal land. These are extensively managed farms that make use of natural pastures and generally provide little supplementary food for livestock.

- Semi-extensive livestock farming. These are farms that use both natural pastures and external food to feed their livestock. They are generally located in valleys and the animals’ access to the natural environment is limited to specific states (‘caseríos’ or ‘granjas’). The georeferenced layers of the General Register of Livestock Farms (REGA, Spanish acronym) of the regional Spanish governments were consulted, complemented by visual classification using orthophotos. Whenever possible, the livestock species farmed (sheep/goats, pigs, cattle, horses and poultry) was determined, based on the official records in the REGA.

- Intensive livestock farming, where animals are housed and confined in enclosures and, therefore, all food resources come from outside. The data sources mentioned for the previous class were used for the identification and characterization of the species farmed.

- Supplementary feeding site, feeding trough or ‘muladar’ specifically intended for the disposal of by-products for feeding scavenger birds, according to the inventories of the autonomous governments.

- Urban solid waste landfill.

From the perspective of the species’ annual cycle, three phenological phases were considered [17].

- Pre-laying and incubation (December to March). This includes the mating season, nest building and incubation, and, partially, the adults’ care of chicks that are a few days/weeks old.

- Rearing (April to July). This includes the period after hatching until the fledglings leave the nest.

- Post-rearing (August to November). After the end of reproduction, a period without reproductive demands.

2.5. PFE Validation

Field inspections were carried out on 96 PFEs (located on semi-extensive farms and mountain pastures) in the five days immediately following their detection, in order to ensure the permanence of remains that reliably proved the feeding event. All field PFE inspections confirmed the presence of remains associated with Griffon Vulture feeding behaviour (partially or fully consumed carcasses, bone remains, ruminal contents, and vulture feathers pulled out, mainly due to aggressive interactions among individuals).

Landfills and supplementary feeding sites identified by the PFE were also visited, but these cases were considered valid as their use as a trophic resource was implicit. Finally, the records of casual and independent visual controls of the two individuals wearing coded wing bands along with GPS/GPRS-GSM transmitters during the study period (July 2019–June 2022) were reviewed in order to verify the spatial and temporal coincidence between feeding events identified by GPS positioning and observations at carrion sites provided by field observers.

2.6. Data Analysis

The GPS data were managed and analysed using QGIS 3.28.3. The variables retrieved for each positional record are listed in Table 1. A linear mixed model (LMM) was fitted using Python (v3.11) and the Statsmodels library (MixedLM), with the phenological cycle phase, resource type and interaction between them as fixed effects, the individual as a random effect to control for pseudo-replication and structural heterogeneity of the data, and the number of PFEs as the dependent variable. The count data were previously transformed log10 (x + 1) and a maximum likelihood estimate was applied. The normality of the residuals of the dependent variable was previously checked using the Shapiro–Wilk test (W = 0.986, p = 0.189). The intercept in the model represents the average number of PFEs during the “rearing” phenological phase when the resource type is “supplementary feeding station”, after accounting for between-individual variation through a random intercept. This value serves as the baseline for interpreting the effects of phenological phase, resource type and their interactions. To check for individual differences in resource type utilisation, an LMM model was also fitted with a random effect dependent on resource type and individual. Data from the only female in the sample was excluded from these analyses.

Table 1.

Attributes of GPS fixes used to identify potential feeding events (PFEs).

Kernel density estimates (KDEs) for the combined PFEs were calculated using the “Model: Home Range KDE” algorithm implemented in QGIS 3.28.3. Isopleths enclosed 50%, 75% and 90% of the distribution, corresponding to core, intermediate-used and home range areas, respectively. Given that all vultures except one breed in the same colony, it was not possible to test for behavioural differences associated with the colony.

3. Results

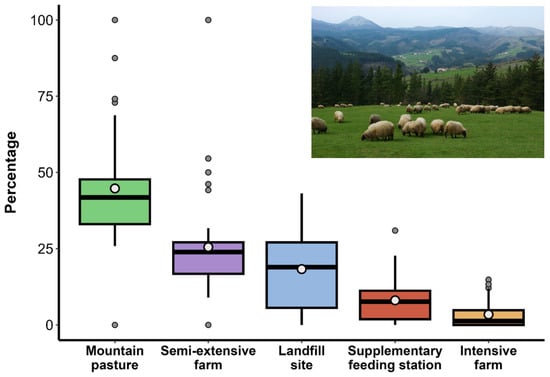

A total of 2348 PFEs were identified, with an average of 235 per individual (range: 109–354). The 302 PFEs corresponding to the only female in the sample were not included in subsequent analyses. Most PFEs occurred in mountain pastures (42%), followed by semi-extensive farms (22%), landfill sites (22%), supplementary feeding stations (9%), and intensive farms (4%; Figure 2). However, differences between individuals were observed (Table 2). During the pre-laying and incubation phase, the use of landfills and intensive farms decreased, while the exploitation of resources in mountain pastures and semi-extensive farms together accounted for 88% of PFEs (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Percentage of PFEs (n = 2046) according to the resource type exploited, including landfill sites (n = 456), supplementary feeding stations (n = 196), mountain pastures (n = 864), semi-extensive farms (n = 446), and intensive farms (n = 84) throughout the annual cycle. Boxes represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, horizontal lines indicate the medians, whiskers show the variability, and points denote outliers. The white circle indicates the mean. The inset image showcases a representative landscape near the vultures’ breeding colony and capture site. Photo: M.Arrazola/Gobierno Vasco.

Table 2.

Individual means (), standard deviations (SD) and ranges of the number of potential feeding events (PFEs) identified according to resource type and phase of the annual cycle.

Eight of the 17 feeding events that were reported in the field by independent observers, which referred to the two vultures carrying coded wing bands and GPS/GPRS-GSM transmitters, were also identified by applying the filtering criteria to the GIS positional dataset.

On semi-extensive farms, the livestock species that accounted for most PFEs were sheep (43%) and horses (37%), followed by cattle (13%). On intensive farms, PFEs were mainly attributed to pigs (81%), followed by cattle (13%) and poultry (6%, Table 3).

Table 3.

Average (), range and standard deviation (SD) of the percentage of PFEs identified by species generating the resource, differentiating between semi-extensive and intensive livestock farming.

The LMM model (Table 4) showed a significantly greater use of resources in mountain pastures (p < 0.001) and, to a lesser extent, in semi-extensive farms (p < 0.001) and landfills (p < 0.01). Intensive livestock farms showed relatively low use (p < 0.01). During the pre-laying and incubation phase, the trophic resource selection was significantly different (p < 0.001), mainly because the use of landfills decreased (p < 0.05). In contrast, during the rearing and post-rearing phases, the consumption of each type of resource was similar.

Table 4.

Results of the mixed linear model (LMM, log10 (x + 1) transformation) applied to the PFEs identified according to individual, annual phenological phase and type of resource exploited. Only significant interactions are shown. The coefficient indicates the intensity and direction of the effect; z refers to the statistical reliability of the effect (if |z| > 1.96, significant 95%).

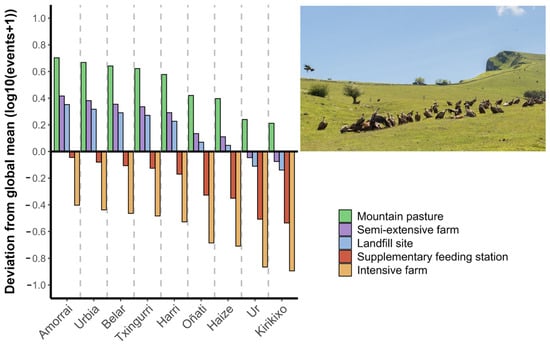

Differences in individual trophic behaviour were observed (Figure 3), as the variance explained by the random effect was high (35.1%, σ2 = 0.22).

Figure 3.

Variation in the use of resource types for each monitored male Griffon Vulture, adjusted to the annual cycle (LMM, log10 (x + 1) transformation). The length of the bars on the Y-axis represents the direction and magnitude of the deviation from the average value across all individuals (set to 0). Labels on the X-axis correspond to the identity of each individual. Inset image shows a group of vultures feeding at a carcass in a mountain pasture close to the breeding colony and capture site. Photo: P. Oliva-Vidal.

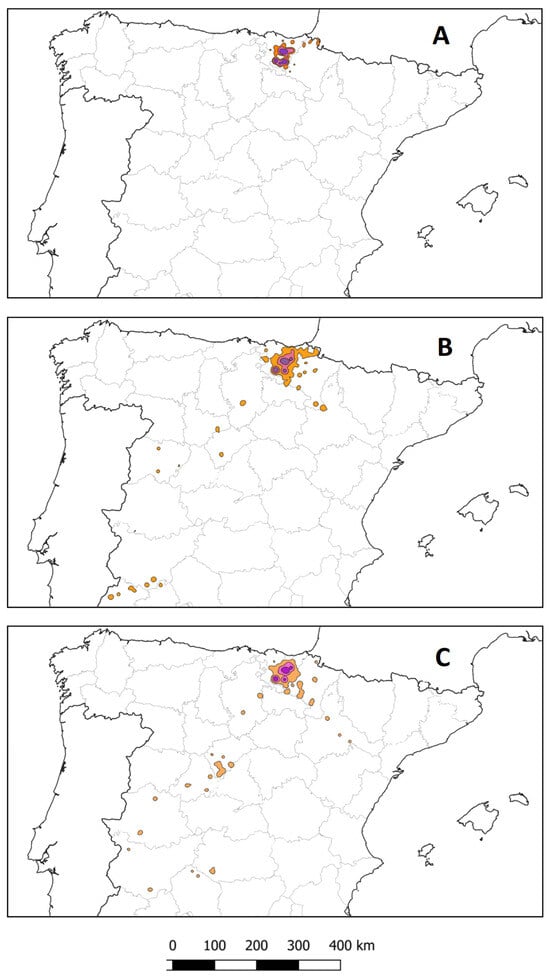

Long-distance (>200 km in a straight line from the breeding colony) and medium-distance (100–150 km) movements were observed. Five individuals made long-distance movements with PFEs identified in central (Castile) and South-western Spain (Extremadura and Andalusia); two individuals only made medium-distance movements (towards the SE, Navarre and Aragón); and three always remained within the Basque Country (Figure 4). Annual reproductive status and phenological phase influenced individual movements. In the combined number of annual cycles monitored (n = 30), long-distance movements were only detected during rearing and post-rearing. Only one of the two vultures that did not breed in a certain year undertook a long-distance movement during pre-laying and incubation. This spatial behaviour influenced the characterisation of trophic resources, as individuals that undertook long- and medium-distance movements visited intensive livestock farms to a greater extent.

Figure 4.

Kernel density estimates (KDEs) of 50% (purple), 75% (pink) and 90% (orange) of the PFEs identified (all individuals combined) during the pre-laying and incubation (A), rearing (B) and post-rearing (C) phenological phases. Maps of Spain include provincial divisions. A graphical scale (km) is shown.

4. Discussion

The confirmation rate of the PFEs assigned to semi-extensive (valley) and extensive (mountain pastures) livestock farms through field inspection was 100%. However, the available sample was small in relation to the total number of PFEs classified in these two categories (6.1%). In this regard, the PFEs identified should be interpreted as the result of a certain vulture being attracted towards a trophic resource (carcass or garbage) for intended feeding, although it cannot be totally excluded that the bird finally was not able to feed there or even that, in some cases, the interest for landing at the site was merely social.

In the case of the two vultures tagged simultaneously with wing bands and GPS/GPRS-GSM transmitters, nine out of the 17 field records at carrions that had been reported by visual observers could not be identified as PFEs by applying the filtering criteria to the GPS dataset. Notably, five of those coincided with transmitter battery charges <75%, when the position acquisition frequency was one hour, therefore reducing the sensitivity of the method to identify timely-usual stays at a carcass [45]. The rest of the omission errors (non-detection by satellite tracking of PFEs reported in the field by visual observers) could be related to feeding events that took place in locations excluded a priori (e.g., rocky and forested areas) and/or to brief stays (<20 min) near the carcass. The exclusion of forest patches, based on the reduction in scavenging activity and efficiency by griffon vultures under tree cover [6], would explain the absence of observations of consumption of wild ungulates (Roe Deer Capreolus capreolus and Wild Boar Sus scrofa), which are forest-dwellers and relatively scarce in the study area, but are known to be present in the Griffon Vulture diet elsewhere [24]. On the other hand, it has been suggested [26,29] that, in these situations, small carrions that are consumed quickly could be underestimated in the diet [6,26,29]. In short, the PFEs identified using the GIS modelling represented valid events, but not all those that occurred were thus detected. This is mainly attributed to the effect of the frequency of GPS positioning acquisition on the model sensitivity.

During the pre-laying and incubation phase, the number of PFEs detected decreased substantially. On the one hand, the lower frequency of GPS position acquisition, due to the decrease in device battery recharge, would partly explain the lower number of PFEs identified, but we must also take into account the decrease in the number of hours spent foraging by vultures, as well as the reduction in food supply due to the transfer of sheep from mountain pastures to semi-extensive farms in the valleys. This seasonal effect on the availability of food resources, which in other populations is compensated for by moving to peripheral geographic areas [16], in our case results in a proportionally increased use of local, semi-extensive farms and supplementary feeding sites. It is interesting to note that, during this phase, the importance of mountain pastures remains relatively stable since, even at this time of year, they still maintain some livestock herds (mainly mares).

Our results suggest that mountain pastures (extensive livestock farming) and semi-extensive farms provide, overall, most of the trophic resources used throughout the year by our Griffon Vulture population. However, Griffon Vulture populations breeding in other regions in N Spain, like Navarre and Aragón, consume much higher proportions of resources from anthropogenic, predictable sources (feeding stations, intensive livestock farms and landfills) [27,39]. In several populations breeding in S Spain (Extremadura and Andalusia) and N Spain (the Cantabrian mountains), the appearance of wild ungulates in their diets is significant [27,39,46]. In this context of population trophic specialization [39], our vulture population would differ from all of them in making greater use of resources from extensive livestock farms on communal mountain pastures and semi-extensive farms, which are characterised by management systems that are seasonally complementary, as they are connected by short-range transhumance movements, with summer stays in the mountains and descent to farms in the valleys in winter [47].

Griffon vultures in the study area also visited urban waste landfills. The high predictability of these resources can be an ecological trap with negative effects due to the consumption of organic matter of low nutritional quality, or of pollutants, drugs and even toxins, which can be accidentally ingested [48,49,50]. The frequency of visits to supplementary feeding sites (one in particular, located 24 km from the breeding colony) highlights their importance in the diet of this population. However, the establishment of supplementary feeding stations as a conservation tool has only been recommended to overcome temporary situations of trophic deficit [30,35], since the regular provision of feeding stations and landfills reduces the ecosystem services provided by vultures and poses challenges associated with the possible modification of the spatial distribution and the behavioural and demographic patterns of the scavenger community [7,15,51,52,53].

Remarkably, the proportion of PFEs in landfills decreased significantly and consistently among individuals during the pre-laying and incubation phase, a pattern that diverges from that described in populations foraging in agricultural and humanised Spanish regions, like Navarre and Aragón [29]. The number of PFEs recorded in intensive farms during the pre-laying and incubation phase was also very low compared to the other phases. Although this interaction was not statistically significant in the LMM, the pattern was largely accounted for by the main effects of phase and resource type. As stated before, pre-laying and incubation were associated with an overall reduction in resource use, and intensive farms showed low use across all phases. As a consequence, the specific interaction term for “pre-laying and incubation × intensive farm” did not depart significantly from the additive expectation of the main effects, even though, in absolute numbers, vultures largely ceased to visit intensive farms during this phenological phase.

Seasonal differences in diet, based on the contrasting use of resources that are relatively unpredictable (mountain pastures and semi-extensive farms) and highly predictable in time and space (landfills, supplementary feeding stations and intensive farms), would be associated with smaller annual home ranges (1331 ± 1305 km2, n = 30, 95% KDE) than those of other monitored populations breeding in the north (the Pyrenees), centre and south of Spain (5027 ± 2123 km2, 95% KDE; populations combined [14]), especially during pre-laying and incubation (Figure 2). In this phase, vultures seem to prioritise the use of local resources [29], both because of their convenient proximity to the colony to perform mating and nesting activities, and the prevailing weather conditions, which do not favour long journeys [14]. Therefore, the availability of resources in mountain and semi-extensive farms would facilitate their use at this time of year. Therefore, the spatial distribution of each type of resource in relation to distance from the colonies would be the main explanatory factor [54]. However, the three landfills regularly used by the monitored individuals are located a short linear distance (<30 km) from the breeding colony, which suggests a negative selection towards them during pre-laying and incubation.

Over the last two decades, national and regional administrations have issued sanitary regulations banning the disposal of livestock carcasses in the countryside and promoted the removal and destruction of carcasses [27,30]. However, according to several published studies [29,39] and our own data, griffon vultures have continued to forage in semi-extensive and intensive farms, where prohibitions are theoretically easier to enforce [55]. These farms are usually located in heavily modified landscapes, where the risks of mortality and sublethal effects for vultures are increased and associated with the density of infrastructures, mainly power lines and wind farms [56,57], and with the exposure to veterinary drugs applied to livestock [58]. In this regard, the risk of ingesting non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is increasing, as documented in Spain [59,60]. Although the situation in Spain differs from that in Asia, where three species of vultures became virtually extinct in the 1990s [61,62], population models indicate that it could potentially have a significant impact [63].

In terms of the species consumed, sheep and horses predominated in semi-extensive farms. In industrial farms, pigs were the main resource, followed by cattle, reflecting the proportions of the national livestock housed in intensive systems. Unfortunately, it was not possible to get data on the species consumed in the mountain pastures, because livestock roam relatively free in these areas, and a certain carcass cannot be attributed to a particular herd, unless confirmed in the field.

Interpopulation variability in the diet of griffon vultures has been described based on social or “cultural” learning [39], but intrapopulation behavioural variability has been less explored. In our study, inter-individual differences were based on the contrasting use of landfills and supplementary feeding stations. Specialisation in the diet of griffon vultures has been linked to sex, males exploiting predictable resources more frequently than females [39]. In our sample, since all individuals were adult breeding males, they were expected to occupy dominant positions within the social structure of the colony and in their ability to access carrion [64,65]. However, it cannot be ruled out that the existence of internal hierarchies stimulates the emergence of displacements by subordinate individuals to compensate for the possible monopolisation of resources close to the colony by higher-ranked vultures [66]. In this sense, variability in individual spatial behaviour would condition the population’s use of trophic resources [14,67]. In our population, the small annual home range relative to others [14] is probably associated with the availability and spatial distribution of trophic resources in the mountain pastures of the study area. This fact, added to the lower dependence on predictable anthropogenic resources, could explain their high survival rate [C. Fernández and P. Azkona, pers. comm.] compared to other populations breeding and foraging in more humanized regions [23,57,68].

Individual differences in spatial behaviour influenced diet, as vultures with medium-distance movements increased the consumption of resources from intensive livestock farms. This effect is associated with the SE direction of such movements (towards Navarre and Aragón), where intensive farms are the most common livestock system. Long-range round-trip movements in a SW direction allow griffon vultures to reach the savanna-like pasturelands in the Southwestern Spanish quadrant, with high densities of extensively managed livestock and wild ungulates, which seem to attract vultures from different populations [9,13,14].

In conclusion, extensive and semi-extensive livestock farming systems, which are predominant and seasonally complementary in the study area, provide most of the trophic requirements for this Griffon Vulture population, allowing the maintenance of evolutionary processes linked to the relative unpredictability of the resource. In this context, it differs from other Iberian populations, which have been characterised by the more regular use of predictable resources in anthropised landscapes [27,39] or which exploit highly seasonal resources and wild ungulates [33,46,69]. Understanding the complex social life of vultures is critical to harmonize their conservation with anthropogenic activities [70]. Our results provide evidence of the important role played by extensive livestock farming in Northern Spain, the maintenance of which is essential to ensure the survival of these species and the important ecosystem services they provide.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, J.M.F.-G., P.O.-V. and A.M.; funding acquisition and project administration, J.M.F.-G., A.L., J.M.M. and A.M.; fieldwork, J.M.F.-G., M.O., E.I., J.U., P.O.-V. and A.M.; formal analysis and writing—draft preparation, J.M.F.-G. and N.J.; writing—review and editing, J.M.F.-G., P.O.-V. and A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the European Regional Development Fund and the Provincial Council of Gipuzkoa (POCTEFA 089/15 project). Satellite tracking was partially funded through project PID2022-142328OB-I00 of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Provincial Council of Gipuzkoa issued the legal permit for trapping and tagging the vultures (license A0095/2019) on 2 January 2019, in accordance with ethical guidelines for studies with animals approved by the Spanish Scientific National Research Council (CSIC).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data is part of an ongoing study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Officers and rangers from the Government of Navarre (E. Castién, A. Llamas, M. López), the Government of Aragón (M. Alcántara, J. L. Rivas, J. Sanz) and the Provincial Council of Gipuzkoa (I. Artola, A. Beñaran, I. Luariz, J. Vázquez) facilitated or assisted in the trapping of the vultures. C. Fernández and P. Azkona shared records about wing-tagged vultures. During the preparation of the manuscript, J.M.F.-G and N.J. used ChatGPT5 for the purpose of generating graphics. The City Council of Vitoria granted access to the municipal landfill. Í. Mendiola and M. de Francisco were responsible for project application and coordination. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication. We thank the comments of four anonymous reviewers, J. A. Gainzarain and N. Ruiz de Azua, that improved this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

As Editor-in-Chief of Conservation, A.M. declares that he has not taken part, in any form, in the review and acceptance processes of the manuscript. The rest of the authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Moleón, M.; Sánchez-Zapata, J.A.; Margalida, A.; Carrete, M.; Owen-Smith, N.; Donázar, J.A. Humans and scavengers: The evolution of interactions and ecosystem services. BioScience 2014, 64, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santangeli, A.; Lambertucci, S.A.; Margalida, A.; Carucci, T.; Botha, A.; Whitehouse-Tedd, K.; Cancellario, T. The global contribution of vultures towards ecosystem services and sustainability: An experts’ perspective. iScience 2024, 27, 109925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Reyes, Z.; Sánchez-Zapata, J.A.; Sebastián-González, E.; Botella, F.; Carrete, M.; Moleón, M. Scavenging efficiency and red fox abundance in Mediterranean mountains with and without vultures. Acta Oecologica 2017, 79, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo-Tomás, P.; Olea, P.P.; Moleón, M.; Vicente, J.; Botella, F.; Selva, N.; Viñuela, J.; Sánchez-Zapata, J.A. From regional to global patterns in vertebrate scavenger communities subsidized by big game hunting. Divers. Distrib. 2015, 21, 913–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moleón, M.; Sánchez-Zapata, J.A.; Sebastián-González, E.; Owen-Smith, N. Carcass size shapes the structure and functioning of an African scavenging assemblage. Oikos 2015, 124, 1391–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva-Vidal, P.; Sebastián-González, E.; Margalida, A. Scavenging in changing environments: Woody encroachment shapes rural scavenger assemblages in Europe. Oikos 2022, e09310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Reyes, Z.; Pérez-García, J.M.; Moleón, M.; Botella, F.; Carrete, M.; Lazcano, C.; Moreno-Opo, R.; Margalida, A.; Donázar, J.A.; Sánchez-Zapata, J.A. Supplanting ecosystem services provided by scavengers raises greenhouse gas emissions. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 7811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Reyes, Z.; Pérez-García, J.M.; Moleón, M.; Botella, F.; Carrete, M.; Donázar, J.A.; Cortés-Avizanda, A.; Arrondo, E.; Moreno-Opo, R.; Margalida, A.; et al. Evaluation of the network of protection areas for the feeding of scavengers (PAFs) in Spain: From biodiversity conservation to greenhouse gas emission savings. J. Appl. Ecol. 2017, 54, 1120–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Jiménez, R.; Pérez-García, J.M.; Morales-Reyes, Z.; Margalida, A. Economic valuation of non-material contributions to people provided by avian scavengers: Harmonizing conservation and wildlife-based tourism. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 187, 107088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Jiménez, R.; Pérez-García, J.M.; Margalida, A.; Morales-Reyes, Z. Avian scavengers’ contributions to people: The cultural dimension of the wildlife-based tourism. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 150419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margalida, A.; Colomer, M.À.; Sanuy, D. Can wild ungulate carcasses provide enough biomass to maintain avian scavenger populations? An empirical assessment using a bio-inspired computational model. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terraube, J.; Andevski, J.; Loercher, F.; Tavares, J. Population Estimates for the Five European Vulture Species: 2022 Update; The Vulture Conservation Foundation: Arhem, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-González, A.; Cortés-Avizanda, A.; Serrano, D.; Arrondo, E.; Duriez, O.; Margalida, A.; Carrete, M.; Oliva-Vidal, P.; Sourp, E.; Morales-Reyes, Z.; et al. Apex scavengers from different European populations converge at threatened savannah landscapes. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morant, J.; Arrondo, E.; Sánchez-Zapata, J.A.; Donázar, J.A.; Cortés-Avizanda, A.; De La Riva, M.; Blanco, G.; Martínez, F.; Oltra, J.; Carrete, M.; et al. Large-scale movement patterns in a social vulture are influenced by seasonality, sex, and breeding region. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 13, e9817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Avizanda, A.; Donázar, J.A.; Pereira, H. Top scavengers in a wilder Europe. In Rewilding European Landscapes; Pereira, H., Navarro, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margalida, A.; Oliva-Vidal, P.; Llamas, A.; Colomer, M.À. Bioinspired models for assessing the importance of transhumance and transboundary management in the conservation of European avian scavengers. Biol. Conserv. 2018, 228, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, A. Buitre leonado—Gyps fulvus. In Enciclopedia Virtual de los Vertebrados Españoles; Salvador, A., Morales, M.B., Eds.; CSIC: Madrid, Spain, 2016; Available online: https://www.vertebradosibericos.org/aves/gypful.html (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- BirdLife International. Gyps fulvus. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; BirdLife International: Cambridge, UK, 2021; p. e.T22695219A157719127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Moral, J.C.; Molina, B. El Buitre Leonado en España. Población Reproductora en 2018 y Método de Censo; SEO/BirdLife: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safford, R.; Andevski, J.; Botha, A.; Bowden, C.G.; Crockford, N.; Garbett, R.; Margalida, A.; Ramírez, I.; Shobrak, M.; Tavares, J.; et al. Vulture conservation: The case for urgent action. Bird Conserv. Int. 2019, 29, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buechley, E.R.; Şekercioğlu, Ç.H. The avian scavenger crisis: Looming extinctions, trophic cascades, and loss of critical ecosystem functions. Biol. Conserv. 2016, 198, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, J.M.; Serrano, D.; Tavecchia, G.; Carrete, M.; Ceballos, O.; Díaz-Delgado, R.; Tella, J.L.; Donázar, J.A. Survival in a long-lived territorial migrant: Effects of life-history traits and ecological conditions in wintering and breeding areas. Oikos 2009, 118, 580–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arévalo-Ayala, D.J.; Real, J.; Margalida, A.; Badia-Boher, J.A.; Mañosa, S.; Durà, C.; Aymerich, J.; Jiménez, J.; Martínez, J.M.; Hernández-Matías, A. Contrasting vital rate contributions across interconnected populations of a highly vagile avian scavenger: A multisite modelling approach. Biol. Conserv. 2025, 311, 111454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donázar, J.A. Los Buitres Ibéricos; Reyero, J.M., Ed.; J.M. Reyero Editor: Madrid, Spain, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Arrondo, E.; Moleón, M.; Cortés-Avizanda, A.; Jiménez, J.; Beja, P.; Sánchez-Zapata, J.A.; Donázar, J.A. Invisible barriers: Differential sanitary regulations constrain vulture movements across country borders. Biol. Conserv. 2018, 219, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkumarev, V.; Dobrev, D.; Stamenov, A.; Terziev, N.; Delchev, A.; Stoychev, S. Using GPS and accelerometry data to study the diet of a top avian scavenger. Bird. Study 2020, 67, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donázar, J.A.; Cortés-Avizanda, A.; Carrete, M. Dietary shifts in two vultures after the demise of supplementary feeding stations: Consequences of the EU sanitary legislation. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2010, 56, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, M.; Colaço, B.; Brandão, R.; Azorín, B.A.; Nicolas, O.; Colaço, J.; Pires, M.J.; Agustí, S.; Casas-Díaz, E.; Lavín, S.; et al. Assessment of the exposure to heavy metals in Griffon Vultures (Gyps fulvus) from the Iberian Peninsula. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2015, 113, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Gómez, L.; Cortés-Avizanda, A.; Arrondo, E.; García-Alfonso, M.; Ceballos, O.; Montelío, E.; Donázar, J.A. Vultures feeding on the dark side: Current sanitary regulations may not be enough. Bird. Conserv. Int. 2022, 32, 590–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margalida, A.; Colomer, M.À. Modelling the effects of sanitary policies on European vulture conservation. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margalida, A.; Moleón, M. Toward carrion-free ecosystems? Front. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 14, 183–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olea, P.P.; Mateo-Tomás, P. The role of traditional farming practices in ecosystem conservation: The case of transhumance and vultures. Biol. Conserv. 2009, 142, 1844–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrondo, E.; Guido, J.; Oliva-Vidal, P.; Margalida, A.; Lambertucci, S.A.; Donázar, J.A.; Cortés-Avizanda, A.; Anadón, J.D.; Sánchez-Zapata, J.A. From Pyrenees to Andes: The relationship between transhumant livestock and vultures. Biol. Conserv. 2023, 283, 10081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colomer, M.À.; Margalida, A. Demographic effects of sanitary policies on European vulture population dynamics: A retrospective modeling approach. Ecol. Appl. 2025, 35, e3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Opo, R.; Trujillano, A.; Arredondo, A.; González, L.M.; Margalida, A. Manipulating size, amount and appearance of food inputs to optimize supplementary feeding programs for European vultures. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 181, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrondo, E.; Cortés-Avizanda, A.; Donázar, J.A. Temporally unpredictable supplementary feeding may benefit endangered scavengers. Ibis 2015, 157, 648–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkumarev, V.; Dobrev, D.; Stamenov, A.; Terziev, N.; Delchev, A.; Stoychev, S. Seasonal dynamics in the exploitation of natural carcasses and supplementary feeding stations by a top avian scavenger. J. Ornithol. 2021, 162, 723–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baino, A.A.; Hopcraft, G.G.; Kendall, C.J.; Newton, J.; Behdenna, A.; Munishi, L.K. We are what we eat, plus some per mill: Using stable isotopes to estimate diet composition in Gyps vultures over space and time. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 12, e8726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrondo, E.; Sebastián-González, E.; Moleón, M.; Morales-Reyes, Z.; Gil-Sánchez, J.M.; Cortés-Avizanda, A.; Ceballos, O.; Donázar, J.A.; Sánchez-Zapata, J.A. Vulture culture: Dietary specialization of an obligate scavenger. Proc. R. Soc. B 2023, 290, 20221951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazi Foundation. Plan de Manejo de los Habitats Pascícolas Vinculados a Actividades Tradicionales: ZEC Aizkorri-Aratz; Project Ruratxa, Ed.; Hazi Foundation: Abadiño, Spain, 2024; Available online: https://ruraltxa.com/wp-content/uploads/A3-plan-manejo_Aizkorri_Aratz.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Wink, M. Application of DNA-Markers to Study the Ecology and Evolution of Raptors. In Holarctic Birds of Prey; Chancellor, R.D., Meyburg, B.-U., Ferrero, J.J., Eds.; ADENEX-WWGBP: Mérida, Spain, 1998; Available online: http://www.raptors-international.org/book/holarctic_birds_of_prey_1998/Wink_1998_49-71.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Mateo-Tomás, P.; Olea, P.P. Griffon Vultures scavenging at night. Trophic niche expansion to reduce intraspecific competition? Ecology 2018, 99, 1897–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiegel, O.; Harel, R.; Getz, W.M.; Nathan, R. Mixed strategies of griffon vultures’ (Gyps fulvus) response to food deprivation lead to a hump-shaped movement pattern. Mov. Ecol. 2013, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavashelishvili, A.; McGrady, M.J. Geographic information system-based modelling of vulture response to carcass appearance in the Caucasus. J. Zool. 2006, 269, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Opo, R.; Trujillano, A.; Margalida, A. Behavioral coexistence and feeding efficiency drive niche partitioning in European avian scavengers. Behav. Ecol. 2016, 27, 1041–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo-Tomás, P.; Olea, P.P. When hunting benefits raptors: A case study of game species and vultures. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2010, 56, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garmendia, E.; Aldezabal, A.; Galán, E.; Andonegi, A.; Del Prado, A.; Gamboa, G.; García, O.; Pardo, G.; Aldai, N.; Barrón, L.J.R. Mountain sheep grazing systems provide multiple ecological, socio-economic, and food quality benefits. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 42, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-García, A.; Sanz-Aguilar, A.; Aguirre, J.I. The trade-offs of foraging at landfills: Landfill use enhances hatching success but decrease the juvenile survival of their offspring on white storks (Ciconia ciconia). Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 778, 146217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherbi-Salmi, R.; Bachir, A.S.; Ghazi, C.; Doumandji, S.E. How food supply in rubbish dumps affects the breeding success and offspring mortality of cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis? Avian Biol. Res. 2022, 15, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva-Vidal, P.; Martínez, J.M.; Sánchez-Barbudo, I.S.; Camarero, P.R.; Colomer, M.À.; Margalida, A.; Mateo, R. Second-generation anticoagulant rodenticides in the blood of obligate and facultative European avian scavengers. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 315, 120385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camiña, Á. Food exploitation by Griffon Vultures: The effect of vulture restaurants in Spain. In International Conference on Conservation and Management of Vulture Populations; Houston, D.C., Piper, S.E., Eds.; Natural History Museum of Crete-WWF Greece: Thesaloniki, Greece, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cortés-Avizanda, A.; Jovani, R.; Carrete, M.; Donázar, J.A. Resource unpredictability promotes species diversity and coexistence in an avian scavenger guild: A field experiment. Ecology 2012, 93, 2570–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arévalo-Ayala, D.J.; Real, J.; Mañosa, S.; Aymerich, J.; Durà, C.; Hernández-Matías, A. Age-specific demographic response of a long-lived scavenger species to reduction of organic matter in a landfill. Animals 2023, 13, 3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Díaz, P.; Cortés-Avizanda, A.; Serrano, D.; Arrondo, E.; Sánchez-Zapata, J.A.; Donázar, J.A. Rewilding processes shape the use of Mediterranean landscapes by an avian top scavenger. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo-Tomás, P.; Gigante, F.D.; Santos, J.; Olea, P.P.; López-Bao, J.V. The continued deficiency in environmental law enforcement illustrated by EU sanitary regulations for scavenger conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2022, 270, 109558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guil, F.; Colomer, M.À.; Moreno-Opo, R.; Margalida, A. Space–time trends in Spanish bird electrocution rates from alternative information sources. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2015, 3, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrondo, E.; Sanz-Aguilar, A.; Pérez-García, J.M.; Cortés-Avizanda, A.; Sánchez-Zapata, J.A.; Donázar, J.A. Landscape anthropization shapes the survival of a top avian scavenger. Biodivers. Conserv. 2020, 29, 1411–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza, P.I.; Wiemeyer, G.M.; Lambertucci, S.A. Veterinary pharmaceuticals as a threat to endangered taxa: Mitigation action for vulture conservation. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 817, 152884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zorrilla, I.; Martínez, R.; Taggart, M.A.; Richards, N. Suspected flunixin poisoing of a wild Eurasian Griffon Vulture from Spain. Conserv. Biol. 2015, 29, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero-Villar, M.; Taggart, M.A.; Mateo, R. Pharmaceuticals in avian scavengers and other birds of prey: A toxicological perspective to improve risk assessments. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 948, 174425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oaks, J.L.; Gilbert, M.; Virani, M.Z.; Watson, R.T.; Meteyer, C.U.; Rideout, B.A.; Shivaprasad, H.L.; Ahmed, S.; Chaudhry, M.J.; Arshad, M.; et al. Diclofenac residues as the cause of population decline of vultures in Pakistan. Nature 2004, 427, 630–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, R.E.; Newton, I.; Shultz, S.; Cunningham, A.A.; Gilbert, G.; Pain, D.J.; Prakash, V. Diclofenac poisoning as a cause of vulture population declines across the Indian subcontinent. J. Appl. Ecol. 2004, 41, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, R.E.; Donázar, J.A.; Sánchez-Zapata, J.A.; Margalida, A. Potential threat to Eurasian Griffon Vultures Gyps fulvus in Spain from veterinary use of the drug diclofenac. J. Appl. Ecol. 2016, 53, 993–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosè, M.; Sarrazin, F. Competitive behaviour and feeding rate in a reintroduced population of Griffon Vultures Gyps fulvus. Ibis 2007, 149, 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Opo, R.; Trujillano, A.; Margalida, A. Larger size and older age confer competitive advantage: Dominance hierarchy within European vulture guild. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deygout, C.; Gault, A.; Duriez, O.; Sarrazin, F.; Bessa-Gomes, C. Impact of food predictability on social facilitation by foraging scavengers. Behav. Ecol. 2010, 21, 1131–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fluhr, J.; Benhamou, S.; Peyrusque, D.; Duriez, O. Space use and time budget in two populations of Griffon Vultures in contrasting landscapes. J. Raptor Res. 2021, 55, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-López, G.; Martínez, F.; Sanz-Aguilar, A.; Carrete, M.; Blanco, G. Long-term monitoring reveals sex- and age-related survival patterns in griffon vultures. J. Zool. 2025, 325, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera-Alcalá, N.; Arrondo, E.; Pascual-Rico, R.; Morales-Reyes, Z.; Gil-Sánchez, J.M.; Donázar, J.A.; Moleón, M.; Sánchez-Zapata, J.A. The value of transhumance for biodiversity conservation: Vulture foraging in relation to livestock movements. Ambio 2022, 51, 1330–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Overveld, T.; Blanco, G.; Moleón, M.; Margalida, A.; Sánchez-Zapata, J.A.; De la Riva, M.; Donázar, J.A. Integrating vulture social behaviour into conservation practice. Condor Ornithol. Appl. 2020, 122, duaa035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.