Abstract

In Aso Kujyu National Park, grassland landscapes are being conserved through volunteer activities to support controlled burns of fields, and the current status of grasslands is being assessed through surveys of natural resources. In discussing the continuation of grassland management in the future, it is necessary to investigate the reasons and factors that lead pastoral associations to request volunteers for managed burning. On the other hand, there are no studies on the reasons why pastoral associations choose to request volunteers to support controlled burns, or the factors behind this choice. Thus, to support multi-stakeholder management of national parks, this study investigates the mechanisms of volunteer engagement in pastoral-led prescribed burning initiatives in Aso Kujyu National Park and key drivers facilitating their engagement involvement. A questionnaire survey was conducted among 161 pastoral associations in the Aso area regarding the introduction of volunteers to support controlled burns. A total of 52 associations responded to the survey, corresponding to a 32% response rate. The results of a discriminant analysis revealed that the pastoral cooperatives that had introduced volunteers did not have enough workers and did not oppose the participation of outsiders, while those that had not employed volunteers had a sufficient number of workers and felt resistance towards the participation of outsiders.

1. Background and Purpose

Grasslands provide a wide range of ecosystem services that contribute to human well-being. Grasslands are among the most extensive and ecologically significant terrestrial ecosystems, covering approximately 30% of the Earth’s land surface and supporting nearly one-third of terrestrial biodiversity [1]. Despite their ecological, cultural, and socio-economic importance, grasslands have historically been undervalued in global conservation agendas. Compared to forests and wetlands, grassland ecosystems have received considerably less protection, and their degradation continues at an alarming pace. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has emphasized that the conservation and restoration of grasslands are essential for achieving international biodiversity targets, including those outlined in the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework [1,2].

In recent years, there has been active research aimed at estimating the economic value of these services [3]. Richard et al. [4] noted that improved grassland management practices and conversion from arable to grassland can improve soil carbon storage. Malin et al. [5] reported that grazing and mowing operations contribute to biodiversity. Pere et al. [6] noted that fire-based grassland management provides habitat for birds. Grasslands and semi-natural grasslands provide a variety of ecosystem services. Semi-natural grasslands have been maintained through traditional agricultural practices such as controlled burning, mowing, and grazing. Allart et al. [7] demonstrates that farmers’ perceptions of permanent grasslands, along with their intentions to adapt to climate change, significantly shape their resilience strategies. Those who attribute high ecological and functional value to diverse grassland ecosystems are more inclined toward sustainable and conservation-oriented management practices. The findings underscore the importance of incorporating farmers’ experiential knowledge, values, and adaptive intentions into policy and practice to enhance the long-term conservation of grassland landscapes under changing climatic conditions.

However, in recent years, the decline of the livestock industry and the aging of rural populations have made the maintenance and management of these grasslands increasingly challenging [8]. The cessation of disturbance-based management has been reported to trigger vegetation succession, leading to shrub encroachment and the loss of species diversity in grasslands. Grassland management will contribute to biodiversity as well as carbon-related issues. In order to continue grassland management that contributes to carbon and biodiversity, it is necessary to accumulate research on the aging and shortage of human resources related to the maintenance of grassland management, which exists as an issue in Japan, and on the decision-making and network of human resources that support grassland management.

National parks are natural reserves designated by the Ministry of the Environment under Natural Parks Law and managed directly by the national government. In 2014, the Ministry of the Environment presented a “Proposal to Promote Collaborative Management and Operation in National Parks“ and stated that in order to conserve the natural environment and promote the use of national parks, it is necessary to promote management and operation in which all parties concerned, including land owners, local governments and park operators, work together [9]. Prior to this, in 2003, the park management organization system was established as a “general incorporated association, non-profit organization, or company with a certain capacity”, designated by the Minister of the Environment in the case of national parks and by prefectural governors in the case of quasi-national parks [10]. Currently, there are a total of seven park management organizations in national parks, but it is stated that the number of designated organizations is limited due to a lack of awareness of the benefits of designation, the inability to designate organizations for profit, and other current conditions. The Aso Green Stock Foundation (hereinafter referred to as Aso GS) was designated as the first national park management organization in 2003. As part of its duties as a park management organization, Aso GS conducts surveys to understand the current status of grasslands, including conservation of grassland landscapes and surveys of natural resources through support activities such as controlled burns by volunteers (hereinafter referred to as “volunteers” [11]. In Aso Kujyu National Park, which is pioneering such collaborative management efforts, maintenance of natural resources and landscape management is being carried out mainly by pastoral cooperatives, Aso GS and volunteers. However, it is reported that the number of pastoral associations is decreasing year by year.

Some of the previous studies on grassland maintenance and management in Aso stated that it is difficult for pastoral associations to secure labor for grassland burning work, and that the aging of the workforce has become significant [12], while others articulated that the burden of cutting the land in rotation, which is a highly labor-intensive part of the grassland burning work, has become too heavy [13]. Furthermore, the volunteer system which started in 1999, has contributed to the reduction in the burden of controlled burn related work and to the effective maintenance of the current situation for pastoral associations [14]. Also, as factors that motivate volunteers to continue their work, it is mentioned that they can share the meaning and joy of their activities revolving around grassland conservation with their peers and that it provides them with an opportunity for social interaction [15]. Another factor that has contributed to the continuation of the system is the risk management system that has been established through many years of activities, based on past cases [16]. These are the key highlights of studies on the current status of pastoral associations and factors that contribute to the continuation of volunteer activities.

In contrast, a study that investigated the implementation of co-management involving Tibetan pastoralists in China’s first national park, Sanjiangyuan, through focus group discussions revealed challenges in gaining full acceptance of the role of “volunteer conservation rangers” among residents in peripheral areas. The study concludes that sustained and meaningful community participation requires fair and inclusive management policies, along with appropriate support for local residents [17].

While the number of pastoral associations in Aso grassland management has been decreasing year by year due to a lack of leaders, demonstrating that the role of volunteers has been increasing. In fact, the number of pastoral associations requesting volunteers from Aso GS is increasing every year (Aso Greenstock). In order to promote the conservation and management of Aso grasslands in the future, it is necessary to clarify the relationship between volunteers and pastoral associations and promote continuous collaborative management. Thus to support this effort, it is necessary to clarify the reasons why pastoral associations choose to request volunteers and the factors behind these choices.

Collaborative management in national parks increasingly integrates stakeholders, institutional innovation, and volunteerism to address complex conservation and social challenges. Adewumi et al. [18] conducted a cross-national comparison of Germany, Japan, Nigeria, and Vietnam, identifying barriers such as fragmented legal frameworks, unclear stakeholder responsibilities, and centralized governance that hinder effective co-management. The study highlights the value of cross-national learning to enhance volunteer engagement and participatory governance. Kwiatkowski et al. [19] documented volunteer-driven ecological restoration and citizen science in Denmark’s Wadden Sea National Park, reflecting a shift towards hybrid governance. Foster [20] analyzed advisory committees in the U.S. National Park Service (NPS), emphasizing their role in fostering transparency, trust, and community–agency linkages. Zhao [21] identified legal frameworks, multi-actor collaboration, and sectoral coordination as key to sustaining Yellowstone’s volunteer system.

Gokita [22] evaluated consensus-building mechanisms using Stakeholder-Targeted Indicators (STIs) in Oku-Nikko, revealing both the promise and practical difficulties of inclusive decision-making in national parks. Ishihara and Tanaka [23] critically assessed Japan’s public–private partnership frameworks—namely Park Management Organizations and Scenic Area Protection Agreements—highlighting persistent transaction costs and limited legal incentives that constrain collaborative governance effectiveness. Jones, Beeton, and Cooper [24] offered a notable case from Mount Fuji, where UNESCO World Heritage inscription served as a catalyst for multi-stakeholder collaboration, exemplified by the development of standardized multilingual trail signage. This case underscores how international designation can galvanize cooperation among multiple landowners and agencies in complex governance contexts. Collectively, these studies emphasize that sustainable conservation outcomes in national parks depend on legally supported, transparent, and inclusive governance structures that effectively engage volunteers and diverse stakeholders, particularly in multi-ownership landscapes characteristic of Japan. Hirasawa [25] points out that consensus building and cooperation with local residents beyond the administrative framework are important for maintaining the landscape of national parks in Japan.

This study aims to contribute to the maintenance of grasslands and the promotion of collaborative management by examining the factors that influence the introduction of external volunteers by local pastoral associations, as well as the associations’ perceptions of the labor involved in grassland management, in the context of a shortage of human resources and the growing need for cooperative maintenance efforts.

Thus, to support multi-stakeholder management of national parks, this study investigates the mechanisms of volunteer engagement in pastoral-led prescribed burning initiatives in Aso Kujyu National Park and key drivers facilitating their engagement involvement.

2. Survey Subjects and Methods

2.1. Research Subject

In this study, the Aso area of Aso Kujyu National Park was selected as the study site because of its pioneering efforts as a national park management organization. Aso-Kujyu National Park was designated in 1934, and is located in the Aso area in northern Kumamoto Prefecture and the Kujyu mountain range and Yufudake in central Oita Prefecture, covering an area of 73,017 ha [26]. The Aso area has one of the world’s largest calderas, extending 18 km from east to west and 25 km from north to south, with a beautiful grassland landscape and a wide variety of flora and fauna. The Aso Outer Rim in Aso Kujyu National Park has a circumference of approximately 128 km [26].

The research subjects of this study were pastoral cooperatives, Aso GS, and volunteers in the Aso area of Aso Kujyu National Park. The number of pastoral cooperatives in Aso Kujyu National Park has been decreasing due to the stagnation of the livestock industry caused by the liberalization of the beef industry in recent years and the aging of the cattle industry, etc. The number of pastoral cooperatives in the Aso area has decreased by about 20 from 175 in 1998 to 156 in 2021.

Aso GS was established with the objective of “positioning the green land of Aso (grasslands, forests, and farmland) as a vital asset (green stock) shared by the people at large and passing it on to future generations through the cooperation of four parties: rural communities, cities, businesses, and governments” [11]. Volunteer activities began in the spring of 1999 with the aim of restoring grasslands that had been lost. While initially 290 people participated in the activities, by 2020, the number of participants has increased to 2306, with people coming both from within and outside Kumamoto prefecture [27].

2.2. Survey Method

First, interviews were conducted in order to understand the organizational structures, roles, and relationships of each entity involved in controlled burn operations. A questionnaire survey was conducted to clarify the factors that led to the introduction of volunteers in pastoral associations. Aso GS, volunteer leaders for controlled burn support (hereafter referred to as “volunteer leaders”), and local government bodies, Aso City and Minami Aso Village were selected as organizations involved in grassland conservation and management as subjects for the interview survey. Aso City was selected for the survey because it covers the largest area in the Aso region and has the largest number of pastoral associations, while Minami Aso Village was selected because of its uniqueness: the village mayor is responsible for any accidents that may occur during controlled burn operations. Table 1 presents the interview targets and the roles of each stakeholder in the implementation of controlled burning. Structured interviews with each entity were conducted with volunteer leaders on 6 March 2023 and 29 August 2023 and with Aso GS on 29 August 2023. Since the situation and roles of each entity involved in grassland maintenance and management are different, we interviewed them about the outline of their organizations, their objectives, the number of people involved, the historical evolution of their activities, key points of consideration when conducting activities, especially in terms of the organization of safety management, and cooperation with and positioning of other organizations. On 29 August 2023, we visited the Aso Kujyu National Park Management Office and interviewed the local pastoral cooperative. On 29 August 2023, we visited the Aso Kujyu National Park Management Office to confirm the status of policies of Aso Kujyu National Park and to schedule a questionnaire survey in advance. On 29 August 2023, we conducted a pilot implementation and confirmed the questionnaire forms with the staff of the Aso Kujyu National Park Management Office, the secretariat of the Aso Greenstock Foundation, and the volunteer leaders for grassland burning.

Table 1.

Interview targets and the roles of each stakeholder in grassland burning implementation.

A questionnaire survey was administered to pastoral associations with the aim of identifying factors that contribute to the adoption of volunteers by pastoral associations. The survey was conducted in two ways: face-to-face or mail-in questionnaire. The face-to-face survey was administered to the members of the council (pastoral associations) who participated in the Aso Grassland Restoration Council (hereafter referred to as “the Council”) held on 31 August 2023 (face-to-face distribution and collection, or mail-in collection). Questionnaires were also distributed to pastureland associations that were not members of the Council but participated in a meeting of wardens at the Minamiaso Village Office on 6 December 2023. The mail survey was conducted over the period of about one month from 13 September 2023 targeting pastureland associations that are members of the Aso Grassland Restoration Council (face-to-face distribution and collection, collection by mail). In addition, a questionnaire survey was conducted by mail for about one month for pastoral associations that had not been received in person at the wardens’ meeting attended on 6 December 2023. The questionnaire survey questions are shown in the Supplementary Data (Table S1). Item 1 shows the basic attributes of the pastoral associations or wards, which are known from the Aso Grassland Maintenance and Restoration Basic Survey conducted by Kumamoto Prefecture once every five years, and in consideration of the respondent’s burden, the respondents were asked to select the name of the pastoral association or district (ward) and the organization that is the main body of activities. The district (ward) refers to an administrative district. The district (ward) was selected based on interviews showing that controlled burning is sometimes initiated by the district as well as the pastoral cooperative. In order to clarify the factors that led to the introduction of volunteers, questions were asked based on the literature survey and interviews regarding the pastoral associations’ perceptions of controlled burn operations. In addition, we set up questions for the pastoral associations that have introduced volunteers to evaluate the volunteers and Aso GS, referring to the evaluation indices [28] of forestry enterprises that involve hazardous work as well as controlled burn work. Referring to Kohroki [29], who applies an axis of labor evaluation with respect to forestry enterprises that involve hazardous work as well as wildland fire work, questions about organizational sustainability, labor security, labor safety, and sociality were set up to clarify the evaluation of volunteers in pastoral associations. Questionnaires were simply tabulated, and the decision-making process regarding the introduction of volunteers was analyzed using a discriminant analysis applying a stepwise method with SPSS Statistics.

3. Results

3.1. Interview Survey Results

3.1.1. Structures of Volunteer Organizations Based on Interviews

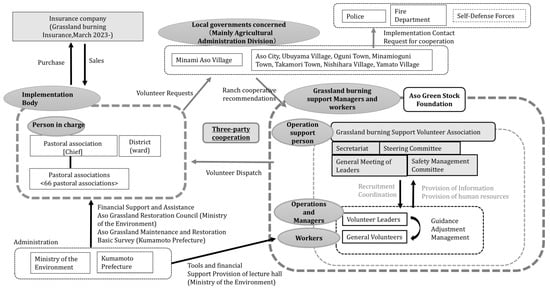

Figure 1 shows the functions of the various entities involved in the support of controlled burn activities based on interviews with the Aso GS, the local government, and volunteers supporting controlled burns. There are two ways for pastoral associations to employ volunteers: first, they make a direct request to the Aso GS; second, the Aso GS asks each municipality (Aso City, Minami-Oguni Town, Oguni Town, Sanzan Village, Takamori Town, Minamiaso Village, Nishihara Village and Yamato Town) to recommend a pastoral association in need of volunteers; and third, each municipality asks the Aso GS to recommend a pastoral association in need of volunteers to the Aso GS. Each municipality then conducts a survey of pastoral associations to determine whether or not they need volunteers, and then compiles a list of pastoral associations in need of volunteers. After the compilation, each municipality recommends pastoral associations in need of volunteers to the Aso GS, and the Aso GS then dispatches volunteers to the pastoral associations in need of volunteers in response to the requests.

Figure 1.

Roles and relationships of each entity involved in grassland burning operations. Source: interview transcript.

Administrative work related to controlled burns is handled by the administrative department in charge. When the pastoral cooperative conducts a controlled burn operation, it submits an application for burning to the Agricultural Affairs Division, which in turn grants permission to the pastoral cooperative to conduct the controlled burn. Prior to the implementation of the controlled burn, the Aso Police Station is notified in advance. In 2022, there were several dangerous incidents due to the large number of grassland burning spectators, so Aso City and others have imposed restrictions since 2023. The hours of regulation are from 9:00 to 15:00, and the police patrol the area and warn people in case there are onlookers. On the day of the burn, fire departments around the Aso area, as well as the Self-Defense Forces and fire departments of other cities and villages are always on standby. Fire departments from Oita and Miyazaki prefectures are also on standby. The administration is in charge of notifying fire departments of controlled burns and of requesting the dispatch of the Self-Defense Forces. Aso GS was not directly involved in firefighting activities or alerting the public, but was positioned to assist the firefighters and police. Therefore, the pastoral cooperative or the district (ward) was responsible for conducting the controlled burns.

Other related issues include contracts with insurance companies. Since controlled burns are hazardous operations that frequently cause accidents, and compensation costs are high in the event of an accident, a contract with Mitsui Sumitomo Insurance has been in place since March 2023. The pastoral cooperatives are not directly related to the insurance company, but each municipality to which the pastoral cooperative belongs pays a contribution to Aso GS according to the area of land burned in the meadows. In the event of an accident, the head of each pastoral cooperative is responsible, but in Minamiaso Village, the village mayor has been responsible since 2005. When the villages merged, the village asked the pastoral cooperative to continue controlled burns, and since the village needed to provide support for the continuation of controlled burns, the village mayor became the responsible party. Minamiaso Village has its own insurance policy, which was put in place when it was still called Hakusui Village, before the municipal merger.

3.1.2. Safety Management at Aso GS and Its Transformation

The number of staff at Aso GS was 12 at the time of the survey, and the number is reported to be increasing year by year. The current composition of the staff was 11 full-time staff, 4 staff involved with volunteers, and 4 staff from GS Corporation.

Regarding the volunteers, at the beginning of the project, the work related to volunteers and their dispatch was managed by a two-person team, but the administrative workload increased as the number of volunteers exceeded 100 in the third year of the controlled burn support volunteer activities. At the time when volunteers were first introduced at Aso Greenstock, there were no cell phones, so all communication was carried out via the landlines at the Aso Greenstock office. Even when a controlled burn was canceled on the day of the event, the coordination had to be done using only two telephone lines. In addition to this administrative work, it was necessary for staff members to accompany the volunteers to the burn sites, so in the third year, a leader was appointed from among the volunteers. In the volunteer leader training, the volunteer leaders received training from SDF alumni and active firefighters (current volunteer association presidents) on first aid in case of accidents and on how to deal with injuries, etc. The leaders were also involved in the dispatch of volunteers.

Volunteer leaders are “individuals who have been recommended by volunteer leaders from among general volunteers and have completed the necessary training” [29]. The decision to dispatch volunteers to support controlled burns on the scheduled day is made by the pastoral cooperative members, who check the areas to be burned in the morning (checking and taking into consideration the effects of rain, wind and other climatic conditions). Wind was the most important factor in the decision-making process, with the reason being that the fire could not be stopped in case the wind became too strong (controlled burns would not be conducted if the wind speed was 8 to 10 m per second or stronger). The head of the pastoral cooperative or ward head contacts the Aso GS, and the Aso GS contacts the participants of the day between around 6:30 and 7:00 a.m., which is at least two hours before the controlled burn. Volunteer leaders check the list of participants and ascertain their attendance, and call participants who do not show up by the time, considering the possibility of accidents on the way. The responsible volunteer leader is selected from among the volunteer leaders in the area, and the responsible leader (selected from among the local volunteer leaders) explains to the participants (volunteers) the precautions to be taken when conducting the controlled burn operation. The responsible volunteer leader was not assigned to a different area every year, but was in charge of the same area for many years, so that he or she could understand the topography and other characteristics of the area, which led to improved work efficiency and the prevention of accidents.

As for safety management, following the death of a volunteer leader in 2012, a safety committee was formed with volunteer leaders who have knowledge of firefighting and lifesaving. In March 2022, an accident involving a volunteer burning in the field occurred, resulting in three burn injuries, two of which were serious. This accident was the second serious accident following the one in 2012, and as a result, the Aso GS recommended that volunteers wear fire-resistant clothing. Before participating in the controlled burn, volunteers underwent basic training for controlled burn support volunteers, where they learned about the value of grasslands and the role of volunteers, and were instructed on how to use fire sticks and backpack water tank for firefighting in the form of a hands-on training. After the controlled burns, the volunteer leaders hold a de-brief with the participating volunteers to hear about “dangers” and report them to the secretariat, where they are discussed at the leaders’ meeting. These leaders’ meetings are held four times a year before and after the controlled burns, and cases of accidents are verified; in February, the last year’s accidents and their findings, the list of pastoral associations were distributed and the schedule was confirmed; and in April, after the controlled burn was conducted, the troubles related to the controlled burn were checked and reported to the pastoral associations and the administration.

3.2. Results of the Questionnaire Survey

3.2.1. Basic Attributes

Fifty-two cooperatives responded to the questionnaire, making it a response rate of 32% (52/161). The number of respondents included the heads of pastoral associations as well as the heads of districts. The survey was conducted in 161 pastoral associations, using the Aso Grassland Maintenance and Restoration Basic Survey, 2021. The Aso area includes eight regions (Aso City, Minami-Oguni Town, Oguni Town, Sanzan Village, Takamori Town, Minami-Aso Village, Nishihara Village, and Yamato Town), and Table 2 below shows the percentage and number of these pastoral cooperatives by region. About 40% of the data were collected from Aso City, which has the largest number of pastureland associations, and 80% from Minamiaso Village. There is no significant difference between the number of pastoral associations and the number of questionnaires collected in the Aso region; questionnaires were generally collected from pastoral associations.

Table 2.

Number of pastoral associations in Aso area (n = 161) and number of associations that administered questionnaires (n = 52).

Twenty-seven of the pastoral associations (heads) and 21 of the districts (heads of wards) were the main entities implementing the activities. The respondents with the longest experience of performing controlled burning work were the most numerous, with 14 associations (wards) answering that they have been doing it for 50 years and 12 association for 60 years. The shortest was 7 years while the longest was 86 years.

As for equipment owned by the respondents, 18 unions answered that they owned walkie-talkies, 48 unions owned gas burners, 47 unions (wards) owned backpack water tanks for firefighting 29 unions (wards) owned grass cutters, 18 unions owned (wards) fire-resistant workwear, 13 unions (wards) leather gloves, 14 unions (wards) helmets, 9 unions (wards) goggles, 42 unions (wards) owned fire extinguishers (42 unions), power sprayers (35 unions), tractors (11 unions), and other equipment (6 unions). Other resources included wood sticks, trucks, and cell phones. Regarding tools, many of the respondent pastoral cooperatives and wards were found to have gas burners, backpack water tanks for firefighting, and fire extinguishers, which are tools used during controlled burning operations.

Regarding whether to continue controlled burning activities in the future, 7 cooperatives (wards) were undecided, 23 cooperatives (wards) agreed, and 20 cooperatives (wards) agreed strongly, with no respondents disagreeing or completely disagreeing. Regarding whether or not volunteers were employed, 21 cooperatives (districts) have employed volunteers, while 31 cooperatives (districts) have not. The pastoral cooperatives that had not introduced volunteers were asked about their intention to employ volunteers in the future. 9 cooperatives (wards) were willing to introduce volunteers, and 21 cooperatives (wards) were not willing to do so. The results showed that 30% of the pastoral associations were willing to employ volunteers, indicating that there are a certain number of pastoral associations and districts that are considering the continuation of grassland burning operations without the introduction of volunteers. As for the pastoral associations that have employed volunteers, the largest number of pastoral associations (4) employed volunteers in 1999, when the volunteer system started, followed by 3 that employed volunteers in 2016. Other years when volunteers were employed included 2003, 2010, and 2013.

3.2.2. Analysis of Volunteer Introduction Factors: Results of the Discriminant Analysis

In order to clarify the factors that contribute to the introduction of volunteers in the pastoral cooperatives, which was the purpose of this study, a discriminant analysis was conducted on the perceptions regarding controlled burn related work. In terms of the procedure, a stepwise analysis was conducted using whether or not volunteers were introduced as a grouping variable, and perceptions related to controlled burn related work (12 items) as an independent variable. As a result, among the 12 explanatory variables, two items were extracted: Q2, “There are enough workers,” and Q5, “There is resistance to the participation of outsiders”. The coefficients of determination were 0.805 for Q2 and 0.637 for Q5. A statistically significant difference was observed in task perception scores between associations that introduced volunteers and those that did not (p < 0.05). SPSS Statistics (version 26.0) statistical software was used for the analysis. The results indicate that pastoral associations that have introduced volunteers “do not have enough workers and have no objections to the participation of outsiders”. The pastoral associations that did not introduce volunteers were found to have “enough workers, but they are not willing to allow outsiders to participate in their activities”.

3.2.3. Background Study of the Factors That Led to the Introduction of Volunteers

The discriminant analysis described above revealed the characteristics of pastoral associations that have introduced volunteers, but the basic attributes of the associations that have introduced volunteers have not been clarified, so data from the Aso Grassland Maintenance and Restoration Basic Survey were used to organize the number of volunteers in terms of the area of controlled burns and the number of volunteers who work in the field.

The introduction to non-introduction ratio of volunteers in pastoral associations in the Aso area is summarized in Table 3, and the number of volunteers is shown in Table 4. The introduction of volunteers was 31% in 61 associations and 62% in 100 associations. The total and average size of controlled burn area where volunteers were not employed was 117 ha, which was larger than that of the areas that have accepted volunteers (85 ha). The number of volunteer workers for controlled burns and rangeland cutting was compared between 2016 and 2021. It was found that there was little difference in the number of volunteers for controlled burn, with a decrease in both cases.

Table 3.

Area of Controlled Burning by Presence or Absence of Volunteer Involvement (n = 54).

Table 4.

Number of volunteers working in the field (n = 54).

From these results, it was understood that pastures with introduced volunteers were significantly understaffed compared to those without volunteers, and that the area of controlled burns was larger in the case of those without volunteers. In addition, the simple aggregate results showed that for the pastoral associations and wards that employed volunteers, factors such as securing volunteer labor, the continuation of controlled burn related work, possession of necessary tools and equipment, safety activities, and mutual help were highly valued.

3.2.4. Reasons for Continuing Controlled Burns (Open-Ended Questionnaire Responses)

The following is a summary of the free response comments regarding the reasons why pastoral associations continue to conduct controlled burns. There were 45 open-ended responses. The most common reason given was “to protect ancestral land use and landscape,” a response given by 27 cooperatives (wards). Other responses included: “To continue livestock farming”, “To prevent grassland burnings”, “Because there are livestock farmers”, “Because it is difficult to restore the land once it is turned into bush”, “Because it is difficult to maintain the grassland landscape if we stop burning the fields”, “To exterminate pests by burning the fields passed down from generation to generation”, “Because the fields will become desolate, if we do not continue to carry the burden and responsibility of burning the fields, that have been maintained for 1000 years”, “Because we can promote the Aso area by maintaining the grasslands”, “To prevent the spread of forest fires, forest fires and disasters”, “To protect the grasslands through the ages”, “Because I keenly felt the importance of protecting the grasslands of Aso”, etc. There was no difference in these responses depending on whether or not volunteers were employed.

3.2.5. Volunteer Introduction vs. Non-Introduction of Pastoral Cooperatives by Region Within the Aso Area

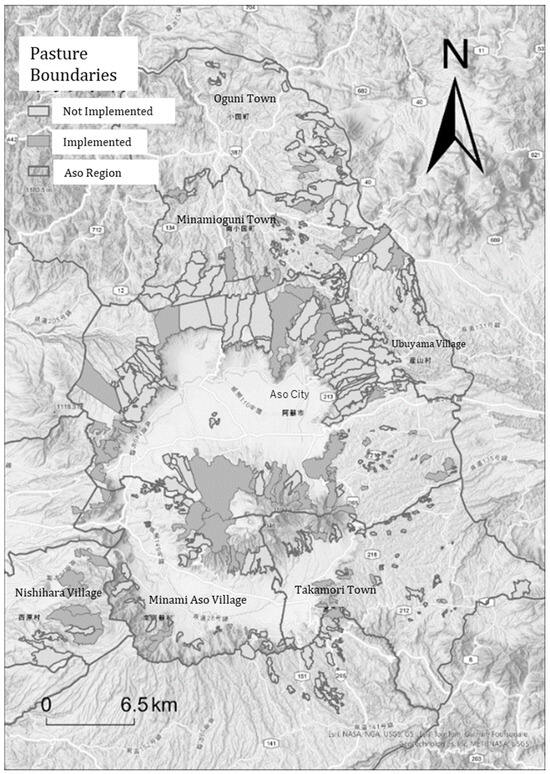

Figure 2 shows the results of the survey on the introduction or non-introduction of volunteers in the Aso area, using the basic grassland survey and the “Volunteer activities to support grassland burning—Location map of supported pastures—as of September 2023” published in the Aso GS newsletter for members. The results were classified using ArcGIS Pro 2.9 and organized by region. Table 5 shows the percentage of the introduction and non-introduction. Aso City, Minami-Oguni Town, Takamori Town, Minamiaso Village, and Nishihara Village have a higher percentage of volunteers than other areas. This result indicates that most of the pastures with volunteers are located in the southern part of the Aso area.

Figure 2.

Volunteer-Introduced and Non-Introduced Areas in Pastoral Associations of the Aso Region. Source: Aso Grassland Restoration Council, “Pasture Boundary Data” [31]. Note: Prepared by the author using the data and ArcGIS Pro 2.9.

Table 5.

Percentage of volunteers in the Aso area by region (n = 167).

4. Discussion

In this study, the roles of the entities involved in the implementation of controlled burns in Aso Kujyu National Park were ascertained through interviews. Pastoral cooperatives and wards are the main actors in the implementation of controlled burns. Due to the stagnation of the livestock industry and the lack of leaders, the main body performing controlled burn operations has shifted from the pastoral cooperatives to districts. On the other hand, in Minamiaso Village, the village mayor is responsible for any accidents that may occur during controlled burn operations, and the village was considering reducing the burden on the pastoral cooperatives and wards.

Controlled burn operations involve the financial risk of having to pay compensation for damages due to the spread of fire, etc. At the urging of Aso GS, the Ministry of the Environment, and other actors, insurance products related to controlled burn were launched and sold by Mitsui Sumitomo Insurance since March 2023, and measures were taken to mitigate the damages. The government coordinated the implementation of the burning operations, communicated with the parties concerned, and played an intermediary role in dispatching volunteers to the Aso GS, the pastoral cooperatives and districts. According to the interview with the Aso GS, the GS appreciated the fact that the administration facilitated the collection of requests from the pastoral cooperatives and districts. It became clear that safety management and smooth implementation of burning operations can be ensured by the allocation of roles and cooperation among multiple entities, including not only the Aso GS and volunteers, but also various government agencies.

The volunteer system has been in place since 1999, and the 2012 fatal accident involving a volunteer led to the establishment of a safety management committee and the preparation of a safety management manual, highlighting the increasing institutional emphasis on volunteer safety protocols, particularly after previous accidents. Volunteer leaders and the Aso GS play a major role in safety management measures. Volunteer leaders were responsible for understanding the natural and social conditions of the area, providing guidance to volunteers, and communicating and reporting on the work status. The Aso GS also judged the attributes of the volunteer leaders and considered the areas to where they need to be dispatched. The Aso GS also deepened exchanges with pastoral associations and wards, and made efforts to understand local information. Such activities of the Aso GS and volunteers may have led to the high evaluation of safety management measures by the pastoral cooperatives and wards.

In this study, a questionnaire survey was conducted among pastoral associations to identify the factors that led to the introduction of volunteers. The results of the aforementioned discriminant analysis revealed that a lack of manpower and resistance to the participation of outsiders were the main factors to be considered in the introduction of volunteers. The findings suggesting that those associations suffering from workforce shortages and having an open attitude toward outsider participation are more likely to accept volunteer support, whereas associations that possess sufficient internal manpower and feel hesitant or resistant towards external actors tends not to. Tsukamoto et al. [32] conducted a questionnaire survey targeting 23 communities in Tottori Prefecture, Japan, to understand local residents’ concerns regarding the involvement of external personnel. They categorized these concerns into three main factors: (1) anxiety about the personal characteristics of external individuals, (2) anxiety about whether outsiders can adapt to local customs and culture, and (3) anxiety about whether local residents and external personnel can establish an equal and cooperative relationship. This study did not track the reasons behind the resistance to outsiders through the questionnaire survey. As Tsukamoto et al. [32] pointed out, further investigation is needed to clarify the underlying reasons for such resistance toward external actors.

Moreover, there was no significant difference in the percentage of volunteers employed or not by region. During the interview survey conducted with volunteer leaders, no clear difference was found between the introduction and non-introduction of volunteers in hazardous areas with steep slopes, such as the Kurokawa Pasture, although the corresponding area was Aso City. However, at the present stage, only superficial differences in the proportion of municipalities are known, and detailed geographical distributions such as pastureland associations and districts have not been investigated. Therefore, it is necessary to examine the factors influencing the introduction or non-introduction of the system, based on the distribution of hazardous areas using GIS and the establishment of a hazard scale for grassland burning operations. In the interview with Aso GS, each pastoral cooperative stated that they perceive danger differently, because they are not connected to other pastoral cooperatives, and we believe that it is necessary to set up a shared danger scale in order to continue the controlled burning operations in the Aso area.

5. Limitations

In this study, we identified the factors influencing the introduction of volunteers in pastoral associations and clarified the perception of grassland burning tasks. Additionally, the study highlighted the functional structure of the various stakeholders involved in grassland management, which can be considered key outcomes of this research. However, the response rate of the questionnaire survey was 32%, indicating the need for improvement in response rates and for securing a sufficient sample size for analysis in future studies. Many of the pastoral association representatives are elderly, making it difficult to obtain cooperation through mail surveys. Therefore, it will be necessary to widely implement alternative methods such as collecting responses directly at meetings and other on-site opportunities.

Moreover, the current discriminant analysis was conducted using only the questionnaire items. Future analyses should incorporate explanatory variables such as the size of the pastureland, the number of members in each association, and the geographical conditions of the burning sites. Conducting such enhanced analyses will allow for a more accurate understanding of the factors influencing the introduction of volunteers. Ultimately, this will contribute to the development of research that supports the establishment of sustainable grassland management systems and relevant institutional frameworks.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/conservation5040060/s1, Table S1: Question and answer items in the questionnaire.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M., Y.O. and R.M.; methodology, M.M., Y.O. and R.M.; software, M.M. and Y.O.; validation, M.M., Y.O., R.M., H.S. and T.J.; investigation, M.M., Y.O., R.M. and H.S.; data curation, M.M. and Y.O.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M. and Y.O.; writing—review and editing, M.M., Y.O., R.M., H.S. and T.J.; visualization, M.M. and Y.O.; funding acquisition, R.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The TOYOTA Foundation 2022 Research Grant Program, grant number D22-R-0083. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to the fact that Tokyo University of Agriculture’s ethics committee, which oversees experiments and surveys involving human subjects (in line with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Ethical Guidelines for Life Science and Medical Research Involving Human Subjects), only covers research in the life sciences and medical fields—and this study does not fall under that category. Instead, to ensure compliance with research ethics, the questionnaire content was reviewed in advance and the survey was conducted under the supervision of the Ministry of the Environment and the Aso Green Stock Foundation; additionally, respondents were clearly informed of voluntary participation without obligation to respond (Tokyo University of Agriculture’s Research Ethics Policy website (https://nodai-nri.jp/promotion/compliance, accessed on 16 July 2025)).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article and Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the Aso Green Stock Foundation, volunteer members, and local municipalities for their valuable cooperation in conducting this study. In particular, we would like to thank Daisuke Washizu of the Aso Green Stock Foundation, Yuji Ueno and Yoshifumi Usui of the Noyaki Support Volunteers for their invaluable cooperation. This research was supported in part by the TOYOTA Foundation 2022 Research Grant Program (D22-R-0083).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that this study received funding from The TOYOTA Foundation. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

References

- IUCN. Grasslands: Essential Ecosystems for Nature and People; International Union for Conservation of Nature: Gland, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.iucn.org (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Bond, W.J.; Parr, C.L. Beyond the forest edge: Ecology, diversity and conservation of the grassy biomes. Biol. Conserv. 2010, 143, 2395–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Hou, L.; Kang, N.; Nan, Z.; Huang, J. The economic value of grassland ecosystem services: A global meta-analysis. Grassl. Res. 2022, 1, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conant, R.T.; Cerri, C.E.P.; Osborne, B.B.; Paustian, K. Grassland management impacts on soil carbon stocks: A new synthesis. Ecol. Appl. 2017, 27, 662–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tälle, M.; Deák, B.; Poschlod, P.; Valkó, O.; Westerberg, L.; Milberg, P. Grazing vs. mowing: A meta-analysis of biodiversity benefits for grassland management. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 222, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, P.; Lambert, B.; Rigolot, E. The effects of grassland management using fire on habitat occupancy and conservation of birds in a mosaic landscape. Biodivers. Conserv. 2003, 12, 1843–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allart, L.; Joly, F.; Oostvogels, V.; Mosnier, C.; Gross, N.; Ripoll-Bosch, R. Farmers’ perceptions of permanent grasslands and their intentions to adapt to climate change influence their resilience strategy. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2024, 39, e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of the Environment. National Parks in Japan: History and Institution. Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/park/about/history.html (accessed on 11 January 2024).

- Ministry of the Environment. March 2014 Proposal to Promote Collaborative Management and Operation in National Parks. Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/content/900492521.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2024).

- Ministry of the Environment. Park Management Organizations. Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/park/workers/management.html (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Aso Green Stock Public Interest Incorporated Foundation. What Is Aso Green Stock? Available online: https://www.asogreenstock.com/aboutus/ (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Mitsuhiro, T. Situation and issues concerning conservation management of grassland. Jpn. Rural. Livelihoods Res. Assoc. 2000, 444, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kenji, O. Grassland management situation in Aso area and the factors of insecurity. Jpn. Soc. Food Agric. Rural. Econ. 2000, 95, 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ryoji, C.; Matsumoto, K.; Sawaki, M. Current status and effects of volunteer participation in grassland maintenance and management activities. Abstr. Kansai Branch Conf. City Plan. Inst. Jpn. 2017, 15, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Machida, R.; Aiko, T.; Matsushima, H.; Take, M.; Shoko, Y.; Mitarai, Y.; Mikami, N. Factors affecting the continuation and constraints of secondary grassland conservation volunteer activities in Aso Kuju National Park. Landsc. Res. 2022, 85, 637–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, R.; Shimada, D. How did the controlled burn support volunteer project in Aso respond to the new coronavirus pandemic: Focusing on the factors for continuing the activity. J. Environ. Econ. Policy Stud. 2021, 14, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, X.; Lin, T.; Sun, S.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, H.; Jones, L.; Liu, W.; Huang, Y.; Lin, M.; Zhang, J.; et al. Greenspace’s value orientations of ecosystem service and socioeconomic service in China. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2022, 8, 2078225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewumi, I.B.; Funck, C.; Nguyen, V.H.; Usui, R. A cross-national comparative study on collaborative management of national parks. Parks 2019, 25, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, G.; Hjalager, A.-M.; Liburd, J.; Simonsen, P.S. Volunteering and collaborative governance innovation in the Wadden Sea National Park. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 971–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, M.K. Examining collaboration within U.S. National Park Service advisory committees. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2020, 38, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T. Volunteer Service Model in the U.S. National Park and Its Inspiration: A Case Study of Yellowstone National Park. In Proceedings of the 2024 10th International Conference on Humanities and Social Science Research (ICHSSR 2024), Xiamen, China, 26–28 April 2024; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2024; pp. 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Gokita, T. Effectiveness of consensus-building methods using Stakeholder-Targeted Indicators in Oku-Nikko, Nikko National Park. MMV Conf. Proc. 2016, 8, 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara, Y.; Tanaka, T. Governance paradox: Implications from Japan’s national parks public-private partnerships. Sustain. Sci. 2023, 18, 1995–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.E.; Beeton, S.; Cooper, M. World heritage listing as a catalyst for collaboration: Can Mount Fuji’s trail signs point the way for Japan’s multi-purpose national parks? J. Ecotourism 2018, 17, 220–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiwasaki, L. Toward sustainable management of national parks in Japan: Securing local community and stakeholder participation. Environ. Manag. 2005, 35, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of the Environment. Aso Kujyu National Park: Topography and Landscape. Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/park/aso/point/index.html (accessed on 17 January 2024).

- Aso Green Stock Public Interest Incorporated Foundation. Data on Support Activities (as of September 2023); (number of participants in Controlled Burn support volunteer activities); Aso Green Stock: Aso-City, Japan, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Aso Green Stock Public Interest Incorporated Foundation. Constitution of the Association of Volunteers for Controlled Burn Support. Available online: https://www.asogreenstock.com/activities/openburning/ (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Katsuhisa, K. Development of Forestry Enterprises and Problems of Forestry Labor. J. For. Econ. 2010, 56, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kumamoto Prefecture. FY2021 Aso Grassland Maintenance and Restoration Basic Survey; Kumamoto Prefecture: Kumamoto-City, Japan, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Aso Grassland Restoration Council. Pasture Boundary Data; Aso Grassland Restoration Council: Aso-City, Japan, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto, T.; Goda, M. Report on ‘Cooperation Measures with Outsiders’ in Maintaining Hilly and Mountainous Areas: Some Considerations on the Uneasiness Borne by the Local People. Jpn. J. Reg. Policy Stud. 2011, 9, 121–128. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).