A Botanical Analysis and Price Comparison of Wildflower “Seed Bombs” Available in Ireland

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Obtaining Seed Bombs

2.2. Seed Extraction and Identification

2.3. Calculations and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Seed Bombs: General Properties and Price Comparison

3.2. Taxonomic Composition of Seed Bombs

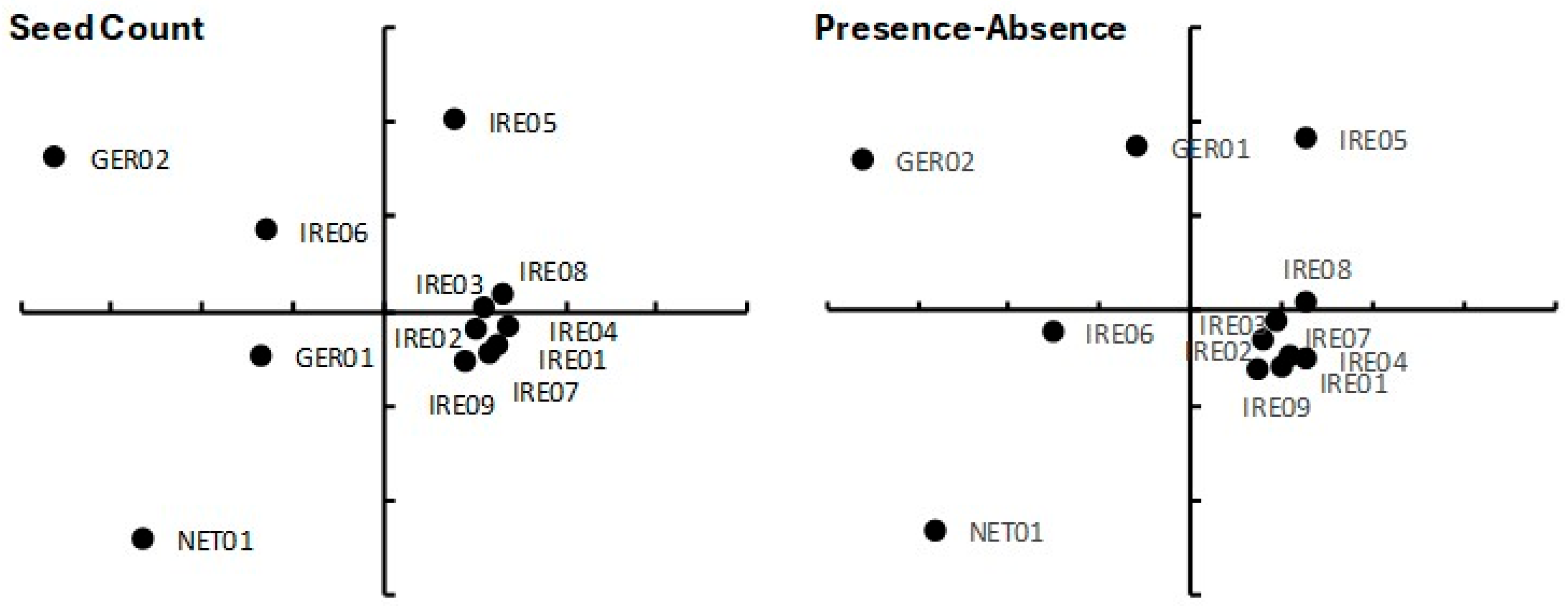

3.3. Multivariate Analysis of Seed Species Composition

4. Discussion

4.1. Seed Bombs: Species Composition and Prevalence of Non-Native Plant Species

4.2. Seed Bombs: Invasive Species, Weeds, and Anomalies

4.3. Seed Bombs: Price and Social Value

4.4. Seed Bombs: Recommendations

4.5. Seed Bombs: Final Words and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Family | Species | Native | Family | Species | Native |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amaranthaceae | Amaranthus blitum | No | Fabaceae | Lathyrus pratensis | Yes |

| Apiaceae | Anethum graveolens | No | Melilotus officinalis | No | |

| Coriandrum sativum | No | Ornithopus sativus | No | ||

| Daucus carota | Yes | Pisum sativum | No | ||

| Asteraceae | Achillea millefolium | Yes | Trifolium alexandrinum | No | |

| Anthemis arvensis | No | Trifolium pratense | Yes | ||

| Centaurea cyanus | Yes | Trifolium repens | Yes | ||

| Centaurea nigra | Yes | Trifolium resupinatum | No | ||

| Glebionis segetum | No | Vicia sativa | No | ||

| Helianthus annuus | No | Gentianaceae | Gentiana verna | Yes | |

| Leucanthemum vulgare | Yes | Hypericaceae | Hypericum perforatum | Yes | |

| Matricaria chamomilla | No | Lamiaceae | Prunella vulgaris | Yes | |

| Rudbeckia hirta | No | Salvia officinalis | Yes | ||

| Silybum marianum | No | Thymus serpyllum | No | ||

| Tagetes erecta | No | Linaceae | Linum grandiflorum | No | |

| Tripleurospermum inodorum | Yes | Lythraceae | Lythrum salicaria | Yes | |

| Boraginaceae | Borago officinalis | No | Malvaceae | Malva sylvestris | No |

| Phacelia tanacetifolia | No | Onagraceae | Epilobium tetragonum | No | |

| Brassicaceae | Arabidopsis thaliana | Yes | Papaveraceae | Papaver rhoeas | No |

| Camelina sativa | No | Papaver somniferum | No | ||

| Cardamine parviflora | No | Plantaginaceae | Digitalis purpurea | Yes | |

| Cardamine pratensis | Yes | Plantago lanceolata | Yes | ||

| Matthiola longipetala | No | Veronica chamaedrys | Yes | ||

| Caprifoliaceae | Knautia arvensis | Yes | Poaceae | Lolium perenne | Yes |

| Caryophyllaceae | Agrostemma githago | No | Polygonaceae | Fagopyrum esculentum | No |

| Cerastium fontanum | Yes | Rumex acetosa | Yes | ||

| Gypsophila elegans | No | Ranunculaceae | Caltha palustris | Yes | |

| Gypsophila vaccaria | No | Nigella sativa | No | ||

| Silene dioica | Yes | Ranunculus acris | Yes | ||

| Silene flos-cuculi | Yes | Ranunculus bulbosus | Yes | ||

| Silene latifolia | No | Rosaceae | Sanguisorba minor | Yes | |

| Rubiaceae | Galium verum | Yes |

References

- Balfour, N.J.; Ollerton, J.; Castellanos, M.C.; Ratnieks, F.L. British phenological records indicate high diversity and extinction rates among late-summer-flying pollinators. Biol. Conserv. 2018, 222, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunet, J.; Fragoso, F.P. What are the main reasons for the worldwide decline in pollinator populations? CABI Rev. 2024, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicks, L.V.; Breeze, T.D.; Ngo, H.T.; Senapathi, D.; An, J.; Aizen, M.A.; Basu, P.; Buchori, D.; Galetto, L.; Garibaldi, L.A.; et al. A global assessment of drivers and risks associated with pollinator decline. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 5, 1453–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweiger, O.; Biesmeijer, J.C.; Bommarco, R.; Hickler, T.; Hulme, P.E.; Klotz, S.; Kühn, I.; Moora, M.; Nielsen, A.; Ohlemüller, R.; et al. Multiple stressors on biotic interactions: How climate change and alien species interact to affect pollination. Biol. Rev. 2010, 85, 777–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulson, D.; Nicholls, E.; Botías, C.; Rotheray, E.L. Bee declines driven by combined stress from parasites, pesticides, and lack of flowers. Science 2015, 347, 1255957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaux, C.; Ducloz, F.; Crauser, D.; Le Conte, Y. Diet effects on honeybee immunocompetence. Biol. Lett. 2010, 6, 562–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dance, C.; Botías, C.; Goulson, D. The combined effects of a monotonous diet and exposure to thiamethoxam on the performance of bumblebee micro-colonies. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017, 139, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIPP. All-Ireland Pollinator Plan 2021–2025. National Biodiversity Data Centre, Series No. 25. 2021. Available online: https://pollinators.ie/aipp-2021-2025 (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Donkersley, P.; Witchalls, S.; Bloom, E.H.; Crowder, D.W. A little does a lot: Can small-scale planting for pollinators make a difference? Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 343, 108254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerch, D.; Blüthgen, N.; Mody, K. Home sweet home: Evaluation of native versus exotic plants as resources for insects in urban green spaces. Ecol. Solut. Evid. 2024, 5, e12380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, C.; Hodge, S. You Reap What You Sow: A Botanical and Economic Assessment of Wildflower Seed Mixes Available in Ireland. Conservation 2023, 3, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackmore, L.M.; Goulson, D. Evaluating the effectiveness of wildflower seed mixes for boosting floral diversity and bumblebee and hoverfly abundance in urban areas. Insect Conserv. Divers. 2014, 7, 480–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths-Lee, J.; Nicholls, E.; Goulson, D. Sown mini-meadows increase pollinator diversity in gardens. J. Insect Conserv. 2022, 26, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witter, L.; Jones, L.; Lowe, A.; Ritchie, W.; Dennis, P.; Beatty, G.; Vere, d.N. The pick of the plot: An evidence-based approach for selecting and testing suitable plants to use in annual seed mixes to attract insect pollinators. Plants People Planet 2025. [CrossRef]

- AIPP. Why We Don’t Recommend Wildflower Seed Mixes. National Biodiversity Data Centre. Online Article. 2022. Available online: http://pollinators.ie/wildflower-seed (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Buckley, Y. Why ‘Wildflower’ Seed is a Prickly Issue. National Biodiversity Data Centre. Online Article. 2021. Available online: http://pollinators.ie/why-wildflower-seed-is-a-prickly-issue/ (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Fitzpatrick, Ú. Why I Don’t Plant Wildflower Seed. Online Article. 2021. Available online: www.pollinators.ie/why-i-dont-plant-wildflower-seed (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Johnson, A.L.; Fetters, A.M.; Ashman, T.L. Considering the unintentional consequences of pollinator gardens for urban native plants: Is the road to extinction paved with good intentions? New Phytol. 2017, 215, 1298–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, N. Spreading Seeds of Doubt—Fake ‘Wildflower’ Mixes. Online Article. 2021. Available online: http://pollinators.ie/spreading-seeds-of-doubt-fake-wildflower-mixes/ (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- DNFC. Dublin Naturalists’ Field Club: The Case Against ‘Wildflower’ Seed Mixtures. 2021. Available online: http://dnfc.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Wildflower-Mixtures-LR.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Smyth, N. Shades of Green—‘wildflowers’ and Biodiversity Urban Planting Considerations. Acta Hortic. 2023, 1374, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nota, G.; Falla, N.M.; Scariot, V.; Lonati, M. An evaluation of ‘pollinator-friendly’ wildflower seed mixes in Italy: Are they potential vectors of alien plant species? NeoBiota 2024, 94, 205–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, A.; Vanni, I. Planty Design Activism: Alliances with Seeds. Des. Cult. 2022, 15, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikadze, V. Ephemeral Urban Landscapes of Guerrilla Gardeners: A Phenomenological Approach. Landsc. Res. 2015, 40, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parenti, I. Seeds of Resistance: Examining Guerrilla Gardening as a Method of Anti-Capitalism and Neoliberal Defiance. LAS J. Undergrad. Scholarsh. 2023, 16, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, E.C.; Minor, E.S. Assessing Four Methods for Establishing Native Plants on Urban Vacant Land. Ambio 2000, 50, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alton, K.; Ratnieks, F.L.W. Caveat Emptor: Do Products Sold to Help Bees and Pollinating Insects Actually Work? Bee World 2020, 97, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streeter, D.; Hart-Davies, C.; Hardcastle, A.; Cole, F.; Harper, L. Collin’s Wild Flower Guide, 2nd ed.; Harper Collins: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Seawright, J. Irish Wildflowers. 2008. Available online: www.irishwildflowers.ie/index.html (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Devlin, Z. The Wildflowers of Ireland: A Field Guide, 2nd ed.; Collins Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Warzecha, D.; Diekötter, T.; Wolters, V.; Jauker, F. Attractiveness of wildflower mixtures for wild bees and hoverflies depends on some key plant species. Insect Conserv. Divers. 2018, 11, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, R.N.; Goulson, D.; Holland, J.M. The best wildflowers for wild bees. J. Insect Conserv. 2019, 23, 819–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RHS. Royal Horticultural Society: Plants for Pollinators. British Wildflowers. Online Article. 2019. Available online: www.rhs.org.uk/science/pdf/conservation-and-biodiversity/wildlife/plants-for-pollinators-wildflowers.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Nikolić, M.; Stevović, S. Family Asteraceae as a sustainable planning tool in phytoremediation and its relevance in urban areas. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teagasc. Beware of Wildflower Mixes as you Might Get More than You Paid For. 2021. Available online: www.teagasc.ie/news--events/news/2021/blackgrass.php (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- European Commission. An Introduction to the Invasive Alien Species of Union Concern; v2022; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2779/791022 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Teagasc. Common Horticultural Weeds. 2020. Available online: https://teagasc.ie/wp-content/uploads/media/website/crops/horticulture/Common-Horticultural-Weeds_2020.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Teagasc. Illustrated Guide to Tillage Weeds. 2014. Available online: https://teagasc.ie/wp-content/uploads/media/website/publications/2014/Guide_to_identifying_Tillage_Weeds_2014.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Lawrence, N. Ecological Benefits of Gardening Wildflowers. Online Article. 2014. Available online: https://phys.org/news/2014-05-ecological-benefits-gardening-wildflowers.html (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Pokorny, K. Guerrilla Gardeners Lob Seed Bombs Bought from Candy Dispensers. Online Article. 2011. Available online: www.oregonlive.com/kympokorny/2011/08/guerilla_gardeners_lob_seed_bo.html (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Hess, C. DIY Seed Bomb STEM Project for Kids. Online Article. 2025. Available online: http://hessunacademy.com/diy-seed-bomb/ (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Kerr, K.C.R.; Harricharan, A.K. Assessing the impact of complimentary wildflower seed packets as an outreach tool for promoting pollinator conservation at a zoo. Appl. Environ. Educ. Commun. 2021, 20, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitts, A.K.; Trost, B.; Trost, N.; Hand, B.; Margulies, J. Learning with the seed bomb: On a classroom encounter with abolition ecology. J. Political Ecol. 2022, 29, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács-Hostyánszki, A.; Piross, I.S.; Shebl, M.A. Non-native plant species integrate well into plant-pollinator networks in a diverse man-made flowering plant community. Urban Ecosyst. 2022, 25, 1491–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenstein, D.M.; Matteson, K.C.; Minor, E.S. Evaluating the dependence of urban pollinators on ornamental, non-native, and ‘weedy’ floral resources. Urban Ecosyst. 2019, 22, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlaepfer, M.A.; Sax, D.F.; Olden, J.D. The potential conservation value of non-native species. Conserv. Biol. 2011, 25, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano, S.; Romano, D.; Lazzeri, V.; Leotta, L.; Bretzel, F. How Can Plants Used for Ornamental Purposes Contribute to Urban Biodiversity? Sustainability 2025, 17, 4061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIPP. Top Ten Pollinator Plants for Different Situations. National Biodiversity Data Centre, Series No. 29. 2023. Available online: http://pollinators.ie/top-10-pollinator-friendly-plants-for-different-situations (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Havens, K.; Vitt, P. The importance of phenological diversity in seed mixes for pollinator restoration. Nat. Areas J. 2016, 36, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlew, R. Seed Bombs: Reasons Why a Clever Idea Barely Works. Online Article. 2015. Available online: www.honeybeesuite.com/why-seed-bombs-dont-work/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Sarma, H.H.; Paul, A.; Kakoti, M.; Goswami, A.; Talukdar, N.; Borkotoky, B.; Dutta, S.K.; Hazarika, P. The aerial genesis: Seed bombing for nurturing earth and ecosystem renaissance-A review. Pharma Innov. J. 2023, 12, 1719–1723. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, M.D.; Davies, K.W.; Williams, C.J.; Svejcar, T.J. Agglomerating seeds to enhance native seedling emergence and growth. J. Appl. Ecol. 2012, 49, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrini, S. A novel multi-species seed pelleting method to improve the efficiency of seed-based ecological restoration. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1595530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Brand Code | Product Name | Date of Purchase | Origin | Website | Composition | Extract Method | Extraction Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRE01 | Faerly | 3 January 2024 | Ireland | https://www.faerly.ie | C + SL | SK | 99 |

| IRE02 | Plants and Extracts | 8 February 2024 | Ireland | https://www.plantsandextracts.ie/ | C + SL | SK | 100 |

| IRE03 | Seedbomb | 14 December 2023 | Ireland | https://seedbomb.ie/ | C + SL | SK | 100 |

| IRE04 | Signature Editions | 10 April 2024 | Ireland | https://signature-editions.ie/ | C + SL | SK | 100 |

| IRE05 | Beebombs | 14 December 2023 | Ireland | https://www.beebombsireland.com/ | C + SL | PM + SK + SV | Na |

| IRE06 | We Make Good | 3 January 2024 | Ireland | https://wemakegood.ie/ | SL + PA | PM | 100 |

| IRE07 | Field Day | 1 June 2024 | Ireland | https://kilkennydesign.com/ | SL | SK | 100 |

| RE08 | Irelands Beeswax Wraps | 3 January 2024 | Ireland | https://irelandbeeswaxwraps.ie/ | SL | SK | 99 |

| IRE09 | Erva | 12 April 2024 | Ireland | https://erva.ie/?v=b2b941e46c50 | C + SL | SK | 100 |

| GER01 | Passions Products | 22 May 2024 | Germany | https://www.etsy.com/ie/shop/PassionProductsDE | PA | SK | 100 |

| GER02 | Seedball Factory | 12 April 2024 | Germany | https://seedball-factory.com/ | C + SL | PM + SK + SV | Na |

| NET01 | Naturally’s Blossombs | 8 February 2024 | Netherlands | https://www.blossombs.fr/en | C | PM + SK + SV | Na |

| Brand Code | Spp List Provided | Bombs per Pack | Bomb Weight (g) | Seeds (per Bomb) | Species (per Bomb) | Species (5 Bombs) | Native Species (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRE01 | No | 10 | 0.83 | 39.8 | 6.8 | 13 | 92 |

| IRE02 | No | 10 | 1.67 | 23.6 | 6.8 | 12 | 75 |

| IRE03 | Yes | 10 | 1.99 | 24.2 | 6.8 | 11 | 82 |

| IRE04 | No | 10 | 1.71 | 24.4 | 4.2 | 9 | 78 |

| IRE05 | Yes | 21 | 4.52 | 47.2 | 9.4 | 16 | 56 |

| IRE06 | No | 3 | 40.39 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 8 | 63 |

| IRE07 | No | 5 | 1.25 | 56.4 | 10.0 | 14 | 86 |

| IRE08 | Yes | 5 | 1.53 | 72.6 | 13.0 | 24 | 83 |

| IRE09 | Yes | 5 | 1.62 | 26.6 | 6.6 | 13 | 85 |

| GER01 | No | 10 | 2.92 | 77.4 | 15.0 | 19 | 47 |

| GER02 | Yes | 10 | 4.4 | 142.0 | 7.2 | 11 | 0 |

| NET01 | Yes | 6 | 5.7 | 77.0 | 9.2 | 11 | 25 |

| Code | Price (€) per | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pack | Bomb | Gram | Seed | Species | |

| IRE01 | 6.39 | 0.64 | 0.77 | 0.016 | 0.09 |

| IRE02 | 10.00 | 1.00 | 0.60 | 0.042 | 0.15 |

| IRE03 | 8.00 | 0.80 | 0.40 | 0.033 | 0.12 |

| IRE04 | 10.00 | 1.00 | 0.58 | 0.041 | 0.24 |

| IRE05 | 7.99 | 0.38 | 0.08 | 0.008 | 0.04 |

| IRE06 | 8.00 | 2.66 | 0.07 | 0.532 | 0.89 |

| IRE07 | 13.00 | 2.60 | 2.08 | 0.046 | 0.26 |

| IRE08 | 4.25 | 0.85 | 0.56 | 0.012 | 0.07 |

| IRE09 | 5.00 | 1.00 | 0.62 | 0.038 | 0.15 |

| GER01 | 3.30 | 0.33 | 0.11 | 0.004 | 0.02 |

| GER02 | 4.90 | 0.49 | 0.11 | 0.003 | 0.07 |

| NET01 | 13.50 | 2.25 | 0.39 | 0.029 | 0.24 |

| Family | IRE01 | IRE02 | IRE03 | IRE04 | IRE05 | IRE06 | IRE07 | IRE08 | IRE09 | GER01 | GER02 | NET01 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amaranthaceae | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - |

| Apiaceae | - | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Asteraceae | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Boraginaceae | - | ✓ | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | ✓ | ✓ |

| Brassicaceae | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | - | ✓ |

| Caprifoliaceae | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - |

| Caryophyllaceae | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ |

| Fabaceae | ✓ | - | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ |

| Gentianaceae | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - |

| Hypericaceae | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | - | - |

| Lamiaceae | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | - |

| Linaceae | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - |

| Lythraceae | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | - |

| Malvaceae | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - |

| Onagraceae | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Papaveraceae | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Plantaginaceae | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | ✓ |

| Poaceae | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - |

| Polygonaceae | ✓ | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - |

| Ranunculaceae | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ |

| Rosaceae | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | - | - |

| Rubiaceae | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | - | - |

| Rank | Species | Seed Count | Species | Brands |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Phacelia tanacetifolia Benth. | 517 | Papaver rhoeas L. | 10 |

| 2 | Trifolium repens L. | 411 | Phacelia tanacetifolia Benth. | 9 |

| 3 | Prunella vulgaris L. | 262 | Trifolium alexandrinum L. | 8 |

| 4 | Lythrum salicaria L. | 244 | Lythrum salicaria L. | 7 |

| 5 | Papaver rhoeas L. | 214 | Leucanthemum vulgare Lam. | 7 |

| 6 | Malva sylvestris L. | 91 | Papaver somniferum L. | 6 |

| 7 | Linum grandiflorum Desf. | 85 | Matthiola longipetala (Vent) DC | 6 |

| 8 | Trifolium alexandrinum L. | 68 | Achillea millefolium L. | 6 |

| 9 | Centaurea cyanus L. | 67 | Caltha palustris L. | 6 |

| 10 | Papaver somniferum L. | 63 | Veronica chamaedrys L. | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prior, E.; Hodge, S. A Botanical Analysis and Price Comparison of Wildflower “Seed Bombs” Available in Ireland. Conservation 2025, 5, 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation5040061

Prior E, Hodge S. A Botanical Analysis and Price Comparison of Wildflower “Seed Bombs” Available in Ireland. Conservation. 2025; 5(4):61. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation5040061

Chicago/Turabian StylePrior, Emma, and Simon Hodge. 2025. "A Botanical Analysis and Price Comparison of Wildflower “Seed Bombs” Available in Ireland" Conservation 5, no. 4: 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation5040061

APA StylePrior, E., & Hodge, S. (2025). A Botanical Analysis and Price Comparison of Wildflower “Seed Bombs” Available in Ireland. Conservation, 5(4), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation5040061