Abstract

The global secondhand apparel industry, valued at USD 256B in 2025, is expanding rapidly. The growing acceptance of secondhand fashion and advancements in retail technology have driven millions of individuals to resell, yet little research has analyzed the motivations behind these decisions. Guided by Consumption Values Theory and Goal-Framing Theory, this qualitative study uses ten in-depth interviews with experienced resellers to examine why individuals participate in apparel reselling. Analysis of the participants’ narratives indicates that financial gain is the dominant driver of participation, followed by the convenience provided by reselling platforms and channels, emotional satisfaction, and contributing to sustainability. Conceptually, the study integrates value-based and goal-based lenses to offer an extensive explanation of reseller motivations, shifting focus from the buyer perspective that has dominated prior research. Practically, the findings suggest that resale platforms can encourage participation by reducing visible fees, enabling faster payout, and simplifying the reselling process, while also making community and environmental benefits more visible. In all, these insights help retailers and sustainability advocates better design approaches that support individual resellers and sustain growth in apparel resale.

1. Introduction

Growing societal pressure, the rise in social media marketing, and ongoing global crises have heightened consumer expectations for corporate social responsibility (CSR). In response, many companies have made visible efforts to act more ethically and address stakeholder concerns (He & Harris, 2020). Nevertheless, the retail sector, particularly fashion, still shows considerable room for improvement. As Thorisdottir and Johannsdottir (2020) argue, true sustainability in apparel retailing requires not only environmental protection but also social equity, economic development, and responsible resource use. As consumers become more vocal about environmental degradation and labor rights violations, fashion retailers face increasing pressure to demonstrate meaningful CSR. Notably, this shift coincides with the growing consumer interest in secondhand apparel, with U.S. consumers purchasing secondhand clothing at increasing rates that are projected to continue over the coming decade (Gazzola et al., 2020).

However, despite rising CSR expectations and growing secondhand demand, the motivations of individual consumers who resell (as vendors) remain underexamined, with prior work emphasizing buyer behavior rather than the seller’s decision process. This study attempts to address that gap by exploring why individuals choose to resell. The investigation is especially timely because, in parallel with this consumer trend, many retailers have launched branded recommerce programs to manage buying and selling of used items (Shulman & Coughlan, 2007) and are experimenting with repair, refurbishment, and resale initiatives that extend product lifecycles and support economic gains in the resale market (Ertz et al., 2016; ThredUp, 2025). As online resale platforms continue to grow in number and scale, competition among platforms has intensified. Understanding the goals of individual vendors can help companies such as The RealReal and ThredUp profile sellers more effectively, refine marketing, reduce participation frictions, and strengthen competitive positioning. Accordingly, to contribute to both academia and industry, this study uses Consumption Value Theory and Goal-Framing Theory as interpretive lenses to describe and organize the motivations for apparel reselling. The guiding research questions are (1) Which consumption values are predominantly activated when an individual decides to participate in apparel resale?, (2) Which goal frames motivate participation in apparel resale?, and (3) What roles, if any, do emotional values play during the apparel resale decision-making process?

2. Literature Review

Building on the increasing consumer interest in secondhand apparel and the expanding resale market, this section begins by reviewing literature on secondhand consumers in general, then shifts toward the seller perspective through discussions of collaborative apparel consumption, apparel resale as a sustainability practice, and branded recommerce. It then introduces two theoretical frameworks (Consumption Values Theory and Goal-Framing Theory) that guide this study’s investigation into the motivations behind individual apparel reselling.

2.1. A New Generation of Secondhand Consumers

The U.S. fashion resale market is an established industry and has been a common practice among consumers for decades (Ertz et al., 2016). Fast forward to the present day, researchers estimate that the U.S. online apparel resale market is expected to double in the next five years to reach USD 77 billion, a rate that is 11 times faster than the fashion industry (B. Wang et al., 2022). Annual report from ThredUp (2025), a secondhand retailer, confirms this rapid growth, adding that the global secondhand market is expected to reach USD 367 billion by 2029 (ThredUp, 2025). The report also notes that one in every three garments purchased between 2022 and 2023 was secondhand, with most sales occurring online.

While various factors may have contributed to this surge, studies suggest that a significant portion is driven by shifting consumer perceptions, particularly the replacement of the once negative stigma surrounding used clothing with a desire for originality, variety, and fluidity in personal wardrobe expression (Ahmad et al., 2015), as well as increased participation among younger consumers. For instance, Kim-Vick and Yu (2023) examined the relationship between online resale platforms and luxury purchase intentions among Generation Z participants. Their study revealed that Generation Z consumers who already owned secondhand luxury items were significantly more likely to repurchase secondhand luxury goods compared to those who owned only new luxury items or none at all. These findings align with previous research crediting Generation Z with driving the rapid growth of the women’s apparel resale market (Shrivastava et al., 2021). Millennials and Generation Z now represent more than half of the global consumer base and are responsible for most purchasing decisions worldwide (Medalla et al., 2020; ThredUp, 2025).

Collectively, these studies not only indicate that the surge in the fashion resale market is due to the participation of younger consumers but also show that younger consumers’ engagement with secondhand apparel extends beyond financial considerations to encompass symbolic, emotional, and identity-driven motives. However, the remaining gap is that the motivations underlying this enthusiasm remain debated and incompletely understood. For example, while some studies highlight sustainability or self-expression as key drivers, B. Wang et al. (2022) found that Chinese consumers born between 1990 and 2000 were motivated instead by the excitement and “treasure-hunting” experience of shopping secondhand. These differing findings suggest the need for a more integrated understanding of the values and decision processes driving apparel reselling, a topic explored further in the next section on technology and collaborative apparel consumption (CAC).

2.2. Impact of Technology on CAC

The recent expansion of secondhand resale can be further understood within the broader context of CAC, which includes not only resale but also rental, swapping, and consignment (Park & Joyner Armstrong, 2019). Studies note that a key driver of the recent prevalence of CAC can be attributed to the rapid advancement of digital technology, which has transformed collaborative consumption from a localized, store-based activity into a large-scale online marketplace. Specifically, technological innovation in retailing has reduced participation barriers and made CAC more convenient, efficient, and socially connected (Park & Joyner Armstrong, 2019). Popular resale channels such as Facebook Marketplace, eBay, Amazon, and Etsy have simplified peer-to-peer transactions (Shrivastava et al., 2021), while online consignment platforms, rental services, and brand-operated secondhand programs have further diversified the ways consumers engage in apparel exchange. Beyond technology, existing research on CAC highlights a variety of motivational factors that parallel those discussed earlier in this study. Motivations uncovered in these studies, including sustainability concerns, social connection, variety seeking, enjoyment, and cost saving (N. L. Kim & Jin, 2020; Hamari et al., 2016), closely mirror the economic, emotional, and social benefits discussed earlier as key drivers of resale participation. Taken together, because resale is a modality within CAC, it may be assumed that the same technology-enabled reductions in friction and increases in convenience are likely to shape individuals’ decisions to participate in apparel resale.

2.3. Apparel Resale as a Vehicle for Sustainability

The environmental impact of the apparel industry has been widely documented and is now a growing concern among consumers. To mitigate the negative effects of overproduction and over-consumption, many consumers have begun embracing slow fashion. Slow fashion represents a shift in the consumer zeitgeist from a quantity-dominant culture to one that prioritizes quality (Jung & Jin, 2014). This slower method of production emphasizes attention to detail and care for each garment, contributing to a more sustainable product. However, while previous studies have explored the characteristics of the slow-fashion consumer, very little research has been performed to address the other side of the coin—the apparel reseller (Jung & Jin, 2016).

Although consumers often express a desire to dispose of unwanted garments sustainably, practical barriers such as convenience and accessibility limit their ability to do so (Laitala, 2014). As a result, most post-consumer textiles still end up in landfills, with less than 15% being recycled (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017). Even well-intentioned donation practices are imperfect, with only about 20% of donated garments resold domestically, while the remainder are exported or downcycled (I. Kim et al., 2021). To address this issue, scholars have proposed a textile waste hierarchy that prioritizes source reduction, reuse, and recovery before recycling and disposal (I. Kim et al., 2021). From this perspective, apparel resale represents a practical and scalable form of reuse that directly extends product lifecycles and reduces waste. Recent studies support this view by showing that perceptions of sustainability positively influence consumer attitudes and purchase behavior toward secondhand clothing (Styvén & Mariani, 2020). In all, these findings suggest that sustainability is likely an important motivation for participating in apparel resale and that resale should be examined not only as an economic activity but also as a sustainability practice.

2.4. Branded Recommerce

With a strong existing customer base and substantial potential for growth, apparel companies must find a way to make fashion resale an important part of their future. This is important not only for financial but also for sustainability reasons. Industry reports and academic studies note that marketing these eco-friendly resale initiatives can lead to economic benefits compared to less sustainable options (Mackey & Sisodia, 2012). From 2007 to 2012, “conscious corporations” outperformed the global market by a ratio of 10.5-to-1, achieving over 1600% in total returns, while the overall market saw just 150% (Mackey & Sisodia, 2012). As the resale sector grows, it is estimated that a 10% increase in secondhand apparel sales could save 4% of water and reduce carbon emissions by 3% per ton of clothing (Styvén & Mariani, 2020). These financial and sustainability incentives create strong pressure for retailers to participate directly in resale rather than allowing independent platforms to dominate.

Indeed, some apparel companies have already seen billions of dollars’ worth of their merchandise resold on peer-to-peer platforms (i.e., Depop, Etsy, Poshmark), and have decided to take back some control of the resale market (Statista Research Department, 2024). In doing so, many retailers have entered, or plan on entering, the “branded resale market,” meaning that they will be controlling the buying and selling of their own merchandise to their consumers (Herman & Kim-Vick, 2023; Lee & Rhee, 2021). What remains unresolved, however, is how retailers can effectively redirect consumer attention from peer-to-peer platforms to branded recommerce programs. Clear guidance on this question is limited, making it an important challenge that retailers face. Addressing this gap requires understanding the motives and decision processes that drive the decision to resell, including how perceived benefits map onto consumer goals. The next section introduces the study’s theoretical frameworks to analyze how consumption values and goal frames shape participation in apparel reselling.

2.5. Theoretical Frameworks—How Values Impact Goals

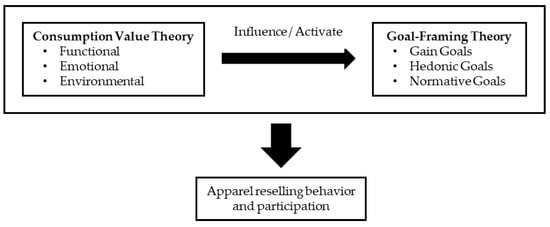

To examine the underlying motivations that influence individuals’ participation in apparel reselling, this study adopts two complementary theoretical perspectives: Consumption Values Theory (Sheth et al., 1991) and Goal-Framing Theory (Lindenberg & Steg, 2007). These frameworks together provide a multidimensional lens through which consumer decisions can be understood. Consumption Values Theory proposes that consumer choice is guided by multiple value dimensions that extend beyond functional utility. The original framework includes functional, social, emotional, epistemic, and conditional values. However, it is important to note that the relative salience of each value varies depending on the context (Sheth et al., 1991), meaning that a value found to be relevant in one context may not be relevant in another. Guided by this principle, epistemic and conditional values are excluded for this study because they are more likely to be applicable to single or first-time engagement (e.g., curiosity about trying resale, decisions driven by a temporary situation) than to the sustained participation, which is the focus of this study. In addition, social value is replaced by environmental value, which is commonly used in perceived-value research within green consumption contexts (e.g., Haws et al., 2013; Yan et al., 2021). This modification reflects that social motives associated with apparel reselling are often closely linked to ecological motives, such as gaining approval for acting sustainably. In this sense, environmental value is included to capture both participation motivated by the perception that reselling is environmentally responsible and participation motivated by the social recognition that accompanies sustainable behavior.

Goal-Framing Theory complements the above perspective by focusing on how values translate into motivational goals that shape behavior. First introduced by Lindenberg and Steg (2007), the Goal-Framing theory outlines the various motivations associated with an individual’s decision-making process. This theory is frequently cited in academic literature related to consumer behavior and expresses similar themes to the consumption values theory. Through their research, Lindenberg and Steg (2007) proposed the following goal frames, which were also included in this research: (1) gain goals, (2) hedonic goals, and (3) normative goals. All three proposed values were deemed relevant to this research and will allow for a proven structure to be applied to the goals of fashion resellers.

Taken together, Consumption Value Theory and Goal-Framing Theory provide a holistic theoretical foundation for understanding apparel reselling as a complex, value-driven, and goal-oriented behavior. Consumption Value Theory identifies what consumers value in reselling, while Goal-Framing Theory explains how those values guide motivation and action. Integrating the two frameworks thus allows for a more comprehensive interpretation of the multifaceted motives behind apparel reselling, encompassing functional, emotional, and environmental dimensions as well as gain, hedonic, and normative goals. Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual model linking these frameworks to the study’s research questions.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

3. Method

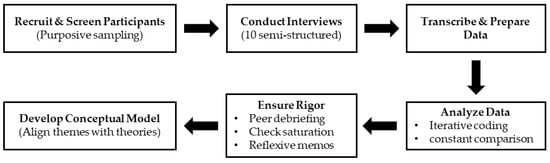

Qualitative research was deemed appropriate for this study due to its ability to uncover complex processes (Maxwell, 2008). Specifically, a phenomenological qualitative design was adopted (Armour et al., 2009). In-depth personal interviews were conducted to capture participants’ accounts of why they participate in apparel reselling and how they describe their motivations and goals. The analysis incorporated grounded-theory techniques (e.g., iterative coding, constant comparison) to develop themes systematically, without following grounded theory’s full protocol (e.g., theoretical sampling, theory generation). Figure 2 illustrates the overall research process.

Figure 2.

Qualitative Research Process.

Participants were selected through purposive sampling (Etikan et al., 2016). Following IRB approval, participants were recruited via personal contacts and screened with questions about their reselling experience over the past two years. The sample varied in age and experience, with approximately 70% belonging to Generation Z (born 1995–2010). Although Generation Z may appear overrepresented, this composition mirrors the current resale market, where younger consumers are prominent (ThredUp, 2025), thereby enhancing ecological validity and relevance of the findings. In this regard, and consistent with qualitative aims, this study does not seek generalization, and the findings are interpreted in light of the sample’s demographic composition.

3.1. Data Collection

Ten personal interviews were conducted between December 2022 and February 2023. All participants volunteered without compensation. Interviews were conducted via Microsoft Teams, allowing participants to join from a location of their choice to foster a relaxed environment. Consent forms and verbal confirmations were obtained before each interview. All sessions were video-recorded and transcribed. Semi-structured interviews were used, guided by predetermined open-ended questions (Given, 2008). Confidentiality was emphasized throughout the process, and each interview lasted between 15 and 30 min. The experienced apparel resellers were selected through purposive sampling. Ages ranged from 22 to 57, with six participants identifying as female and four as male. Resale experience ranged from one-time sellers to resale entrepreneurs, offering a broad view of reselling behaviors. To protect participant identity, pseudonyms were assigned. Table 1, shown below, includes demographic information and resale experience to enhance the richness and validity of the findings.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Participants Participated in the Reselling of Apparel as a Vendor.

3.2. Data Analysis

After each interview, the transcript generated by Microsoft Teams was manually corrected using the original audio and video recordings. Each transcript was then read multiple times and thematically coded following the method outlined by Naeem et al. (2023). The analysis proceeded iteratively and used constant comparison across transcripts. In the first cycle, salient passages were highlighted to establish broadly relevant codes, then in the second cycle, these codes were refined into more specific subthemes, with ongoing comparison of incidents within and across interviews. This process yielded 16 refined themes, which were then grouped into broader categories based on shared characteristics. A thematic index was created to reflect these higher-order themes. Both inductive and deductive coding were used to guide theme development.

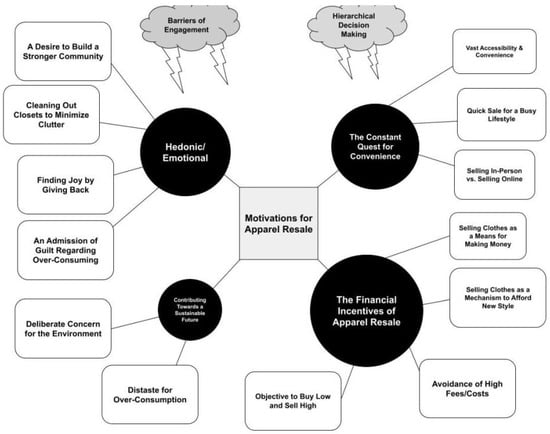

To ensure analytical rigor, coding reliability was strengthened through peer debriefing, in which a second researcher independently reviewed a subset of transcripts and codes to assess intercoder consistency, with minor discrepancies resolved through discussion. Thematic saturation was achieved by the ninth interview, as no new themes emerged in subsequent transcripts. Reflexivity was maintained through memo writing and regular discussions during the analysis. These steps helped identify potential researcher biases, ensuring that interpretations were grounded in participants’ own narratives rather than researcher expectations. Finally, a conceptual model was constructed to illustrate the relationships between the broader themes and their corresponding sub-themes (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Emerging Themes and Sub-Themes of the Individual Participating in the Reselling Motivations of Apparel.

4. Findings and Discussion

As shown in Figure 3, the following four major themes and 13 sub-themes were developed: (1) financial incentives of apparel resale, (2) constant quest for convenience, (3) hedonic and emotional motivations for reselling secondhand apparel, and (4) contribution towards a sustainable future. Each of these four buckets consists of a handful of sub-themes, grouped by shared characteristics, that allow the researchers to better articulate the core findings of the dataset.

4.1. Financial Incentives of Apparel Resale

4.1.1. Objective to Buy Low and Sell High

All ten participants identified financial gain as a primary motivation for reselling apparel, even without prompting. When describing positive experiences, respondents cited resale as a way to “get money from things I knew I wasn’t wearing” (Mrs. Teitelbaum, 55) and a path toward “financial freedom” (Mr. Hughes, 22). Many highlighted entrepreneurial motives, such as “buying low and selling high” (Mr. Hughes, 22) or “starting a secondhand business” (Ms. Lifshitz, 25). Others elaborated on strategies like “buying clothing as an investment” (Mr. Osborne, 26) or seeking out deals with resale in mind (Mr. Lawrence, 58). Although selling anything is inherently lucrative, it is important to note that all 10 respondents mentioned making money as a motivational factor for reselling used clothing. In a similar sense, some participants emphasized maximizing profit, often choosing resale platforms based on lower transaction fees. For example, Ms. Lifshitz preferred Poshmark over Depop because it was “cheaper,” while Mr. Lawrence chose eBay to “keep a big percentage of the profit.” Younger resellers, particularly those born between 1997 and 2000, were especially fee-conscious. Interestingly, participants born between 1997 and 2000 were more deliberate regarding their distaste towards high resale fees. Rather than paying a “30% commission fee on a $20 piece, after paying for shipping” (Mr. Hughes, 22), younger resellers may begin to direct their business towards other resale channels that allow for a higher return on investment.

4.1.2. Avoidance of High Fees/Costs

Financial gain is directly correlated to functional values, which are a defining characteristic of the consumption values theory (Sheth et al., 1991). While the financial gain was certainly a common motivator towards the decision to resell used apparel, many respondents expressed concerns regarding the “ever-increasing” commission rates (Mr. Hughes, 22). When asked why they chose to sell using a particular sales channel (i.e., eBay or Etsy), half of all respondents chose the channel that offered “lower fees” (Ms. Lifshitz, 25), while trying to limit the “unexpected fees that go into it [apparel resale] (Mr. Hughes, 22). This finding is in line with the literature reporting that functional values are the single most important factor in determining a consumer’s choice (e.g., Gonçalves et al., 2016). This belief often trickles down economically, leading fashion-resale practitioners to consistently seek the maximum functional value at the lowest possible cost (Awuni & Du, 2016; Hur et al., 2012). Financial motivation can also be explained by the Goal-Framing Theory (Lindenberg & Steg, 2007), particularly gain goals, which are activated when a person desires more of a resource, such as money, than they currently possess. As financial frustration or perceived discrepancies increase, so does the motivation to act (Sheth et al., 1991). In apparel resale, gain goals are expressed when resellers look for the highest ROI (Awuni & Du, 2016; Guiot & Roux, 2010; Williams & Paddock, 2003).

4.1.3. Selling Clothes as a Mechanism to Afford a New Style or to Make Money

The notions of keen price awareness and commitment to online apparel resale are well documented in the previous literature (Kim-Vick & Yu, 2023). In alignment with existing research, this study proposes that the desire to obtain some form of financial compensation is heavily correlated with the decision to resell apparel products. While initially many participants seemed reluctant to outwardly express their monetary motivations, all 10 eventually went on to demonstrate a deliberate intent to receive the best return on their investment. As illustrated by the occasional reseller Ms. Gonzales, “The one [resale channel] that I end up choosing usually takes more and offers more money”. As the interviews progressed, the respondents appeared to become more self-assured, leading them to reveal that they “usually take the money to buy new updated styles (Ms. Garcia, 25). This allocation of funds towards the purchase of new apparel is supported by Gazzola et al. (2020), stating that 77% of all fashion resale practitioners consider the resale value of a product when purchasing a full-priced item. This belief is explored further in a study conducted by Ertz et al. (2016), who identified economic gain as one of the key determinants for online resale motivation. Reselling used apparel allows individual vendors to alleviate financial stress by giving their products a second life, in exchange for a profit (Guiot & Roux, 2010; Williams & Paddock, 2003). Researchers Park and Joyner Armstrong (2019) allude to readily available technology as the main driver for “connecting a vast number of resale customers much more easily and less costly.” Online peer-to-peer resale platforms have increased the ease of economic gain for individual vendors (Chu & Liao, 2007, 2010). This has led to a hyper-awareness of a garment’s resale value when purchasing new products. Turunen et al. (2020) found that selling secondhand luxury goods involves sellers’ detachment from the past symbolic meanings and financial gain. Secondly, they also gain social status as sellers of reputable items, as well as environmentally conscious consumers, to take part in the circular economy. The variation between the literature and our findings may stem from the type of apparel and cultural context. For instance, Turunen et al. (2020)’s findings are grounded in the selling of the secondhand luxury goods category among European consumers, while our participants shared their narratives on selling various product categories at different price points in the US.

4.2. Constant Quest for Convenience

Convenience emerged as the second most prominent theme among respondents, following financial motivation. Six out of ten participants mentioned the importance of a quick sale when reflecting on their most positive resale experiences. As Mr. Lawrence (58) explained, “a very convenient [resale] format would probably make me sell more.” While participants were transparent about their monetary goals, many also emphasized the critical role of convenience in shaping their resale behavior.

Yeah. So, I mean, when you go to like a Plato’s Closet, they obviously don’t give you enough, you know, for what it’s worth. But you do get that immediate gratification. The eBay process is more (about) waiting to see if someone’s gonna buy it. And maybe haggling on price a little bit, and probably not getting exactly what you would like to get for it.(Mrs. Teitelbaum)

This desire for immediacy was echoed by others who acknowledged the effort and time required to resell online. Mr. Lawrence (58) noted that many sellers choose “convenience over profit,” and Ms. Garcia (25) stated that “it takes a lot of work to try and sell clothes.” Despite the higher returns associated with online apparel resale, participants often found the process too time-consuming and inefficient. As Ms. Teller explained, “It’s just because the money difference is so significant, even though the convenience of selling online is not up to par.” In some cases, this inconvenience discouraged resale altogether. Mr. Lawrence (58) admitted to donating “a lot that is probably sellable, just because it’s inconvenient for me to sell”. Several participants compared online and in-person methods, expressing a clear preference for the simplicity of consignment stores. Ms. Gonzales (25) noted, “So I have done other methods like I’ve sold stuff online before, but I’ve found that like going to the store in person is faster… And I was just lazy.”

Yet, opinions were not entirely one-sided. Some respondents acknowledged frustrations with consignment stores, citing “stipulations” (Ms. Gonzales, 25) and the “significant money difference” (Ms. Teller, 25) when compared to online resale. Nevertheless, when asked whether they preferred reselling in person or online, most leaned toward the former. Ms. Teller (25) summarized this sentiment:

I mean, if everything was equal, I’d much rather do it in person. Just because you’re making one trip, you’re dropping everything off. You’re probably doing it in larger units. It’s not like you’re individually bringing one piece at a time. I feel like.(Ms. Teller, 25)

When asked to describe their ideal resale experience, six respondents prioritized convenience, despite acknowledging that consignment stores “don’t give you enough” (Mrs. Teitelbaum, 55). This trade-off between convenience and financial return reflects conditional values, as described in the Consumption Values Theory (Sheth et al., 1991). Conditional values are activated by specific situational factors, such as time pressure or physical effort, and can shift preferences accordingly. Hur et al. (2012) support this notion, suggesting that physical and psychological conditions influence the perceived value of sustainable products.

The findings also support predictions by Chu and Liao (2007), who anticipated that the rise in peer-to-peer marketplaces would disrupt traditional consignment by increasing seller responsibility. Ertz et al. (2016) reinforce this, noting that online recommerce has produced a “thin” and “concentrated” market in which resale is slower and more complex. Although none of the participants reported discarding clothing, this study’s findings also parallel those of Joung and Park-Poaps (2013), who observed that convenience often leads consumers to throw away unwanted garments rather than resell or donate them. Ultimately, this study confirms that convenience frequently acts as the deciding factor in whether and how individuals engage in apparel resale.

4.3. Hedonic and Emotional Motivations for Reselling Secondhand Apparel

When asked to reflect on intrinsic and extrinsic motivations for reselling, participants shared personal stories that revealed sources of emotional and hedonic fulfillment. In response to prompts such as “Why is it important to you that your unwanted clothes are still getting used after you’re finished with them?” and “How does reselling your used apparel make you feel?”, four sub-themes emerged: (1) A desire to support others or build a stronger community, (2) cleaning out closets to minimize clutter, (3) finding joy from giving back, and (4) relief from guilt related to over-consumption.

4.3.1. A Desire to Build a Stronger Community

Several participants described how resale offers a way to help others. “There’s a lot of poverty” in her hometown, shared Ms. Garcia, adding that she takes pride in “selling it [clothing] to someone who needs it” (Ms. Garcia, 25). Others mentioned making clothes accessible to those who “don’t have a lot of money” (Mr. Strauss, 25) or donating suits “if somebody has a job or an interview coming up” (Mr. Lawrence, 58). Six participants expressed that resale allowed them to support “people who can’t afford clothes or aren’t as fortunate” (Mrs. Teitelbaum, 55). Some humorously summarized this with, “one man’s trash is another man’s treasure” (Mr. Hughes, 22; Mrs. Marten, 58).

If you don’t have money for clothes or for other basic necessities like, you should totally be like “Here, you can just have the clothes”. I don’t want like, why would you spend money on something that isn’t like important [clothing], like it’s not as important as food or a roof over your head or gas or whatever is, what you need to, like support you and your family so.(Mr. Strauss, 25)

4.3.2. Cleaning Out Closets to Minimize Clutter

On the topic of satisfying hedonic needs, other participants stated that “it feels good to be minimalistic” (Ms. Gonzales, 25), and that they “definitely do like that feeling of getting rid of stuff (Mrs. Teitelbaum, 55). Multiple participants complained about unwanted clothes “taking up space and clutter” (Ms. Garcia, 25) in their closets, stating that “if I don’t wear something for six months, it’s usually gotta go” (Mr. Lawrence, 58). The findings of this research also demonstrate participants’ desire to “just get rid of old clothes”, even going so far as to suggest that apparel resale is “more meaningful” (Ms. Gonzales, 25) than simply hoarding them in a closet. As the interviews continued, it became increasingly clear that the participants viewed apparel resale to be an inherently meaningful activity.

Emphasizing the social components of collaborative consumption (Shrivastava et al., 2021), participants expressed gratitude towards building a “little connection” (Mrs. Marten, 58) through the “business aspect” of apparel resale. Fashion resellers discovered a sense of “community” (Mr. Hughes, 22) with similarly styled peers online, while falling in love with “the whole social process” (Mrs. Marten, 58) of selling used clothing. These findings align with the social values component of the consumption values theory (Sheth et al., 1991). As illustrated in the consumption values theory, social values refer to the perceived utility gained when an individual decides to interact with one or more specific social groups (Sheth et al., 1991). Social values are frequently discussed in the literature relating to collaborative consumption, particularly in terms of secondhand apparel consumption. Barnes and Mattsson (2017) discovered that collaborative consumption is often driven by a need for enjoyment and a sense of belonging.

4.3.3. Finding Joy by Giving Back

An overwhelming majority of participants (7) explicitly stated that reselling used apparel provided them with some amount of personal fulfillment or joy. When describing the feelings elicited from selling used apparel, some participants expressed that their resale experiences made them “feel good” (Mr. Lawrence, 58, Mrs. Teitelbaum, 55, and Ms. Gonzales, 25), made them “happy” (Mr. Hughes, 22), or even described the experience as being “fun” (Mr. Strauss, 25). Out of the many examples of hedonic satisfaction, participants most frequently mentioned that selling clothes to “people in need” (Mrs. Teitelbaum, 55) gave them a sense of relief. These participants described selling clothes as “pushing the weight off of yourself” (Ms. Lifshitz, 26) by providing those who “aren’t as fortunate” with affordable clothing.

I don’t want to have so much stuff, so like personally it feels good to be like more minimalistic, but then on like a wider scale, I know that people are in need of clothes, so if the thing that I never wore is something that someone else can benefit from then that’s also important.(Ms. Gonzales, 25)

4.3.4. Admission of Guilt Regarding Over-Consumption

Many participants in this study admitted to leaning on apparel resale as a method to displace some of the burdens associated with over-consumption, even absolving themselves of guilt.

Umm, it’s just like, I guess, the guilt. It’s actually very funny. My friend and I’s Depop store that we have is called Not Guilty At All. That’s the name. So I just kind of like play off the guiltiness of people and then of myself when I have to throw things out and don’t know what to do with it. So just kind of like, now that I’m reflecting back to it, it is kind of a little naive and like, to do that, like it’s kind of bad to do that. I feel like, I feel bad. But it just kind of like pushes the weight off yourself.(Ms. Lifshitz, 26)

According to the statements provided by the interview participants, it was indicated that apparel resellers not only perceive themselves as individuals who care about the betterment of their communities and “less fortunate” (Mrs. Teitelbaum, 55) neighbors, but also consider the act of reselling as a “meaningful” (Ms. Gonzales, 25) method for discarding unwanted clothing. These expressions of emotion draw similarities to findings from the consumption values theory (Sheth et al., 1991). One finding from this theory is emotional values, or “the perceived utility acquired as a result of an alternative’s capacity to arouse feelings or affective states” (Sheth et al., 1991).

Findings from this research draw parallels to multiple existing studies, most notably the Goal-Framing Theory (Lindenberg & Steg, 2007). In their work, hedonic goals were identified as one of three pivotal contributing factors in cognitive decision-making. Hedonic goals represent the human desire to experience a feeling of happiness (Lindenberg & Steg, 2007). Guiot and Roux (2010) analyzed hedonic goals as a motivational framework as it pertains to second-hand clothing consumption. The researchers concluded that hedonic goals directly correlate with a desire for uniqueness, a need for originality, an aspiration for human/social interaction, and nostalgic pleasure (Guiot & Roux, 2010). The influence of hedonic motivations on repurchase intention was assessed in great detail by Guiot and Roux (2010). Their research suggests that a consumer’s role and identity play a major part in resale intention. This feeling of belonging and newfound purpose has been brought to the masses through the implementation of e-commerce (Hameed & Khan, 2020). An improved online presence has given individuals the opportunity to fulfill their hedonic goals through a widespread e-commerce and resale market community.

4.4. Contribution Towards a Sustainable Future

The findings of this study suggest that participants possess a distaste for over-consumption, compounded by their deliberate concerns for the environment. The head researcher was cognizant of abstaining from using probing words to elicit a response about sustainability. Nonetheless, several respondents pledged their commitment to creating a sustainable future, with statements such as “70% of my clothes are thrifted” (Ms. Lifshitz, 26) and “it’s important, I think, to keep clothing out of landfills” (Ms. Teller, 25). Participants described themselves as being “sustainable” (Mr. Hughes, 22), even going as far as to say they were “planet-friendly” (Ms. Teller, 25).

I find that really intriguing, and throughout fashion production, another thing, like I said, is just being sustainable. There’s a ton of clothes on the planet. Fashion is one of the top three biggest polluting industries. It makes me feel good doing my part, knowing that I’m getting a good deal on something and also not creating more waste.(Mr. Hughes, 22)

Direct correlations can be drawn between this study and the Green Values Theory (Haws et al., 2013), which was adopted using principles from the consumption values theory (Sheth et al., 1991; Yan et al., 2021). A broader definition describes environmental values as being an overarching concern for the livelihood of the environment and humanity’s interactions with it (Styvén & Mariani, 2020). Numerous wasteful practices demonstrate the disposal of garments in harmful ways, including the discarding or demolition of unwanted apparel. They (2020) stressed that to negate the damage done by the apparel industry, environmental values are brought to the forefront, thus altering a reseller’s attitude toward certain disposal practices. By keeping their garments in circulation through fashion resale, resellers can ensure that their clothing will be properly handled, beyond simply by its first owner.

Simultaneously, external pressure, such as the detrimental impacts of the apparel industry on the environment, has been well documented and has gained widespread awareness in recent years (Steg et al., 2014). To combat these wrongdoings, many individuals have taken it upon themselves to resort to reselling their used apparel. This core belief, along with a need for happiness and a sense of belonging, is the primary motivation behind apparel resale (Ferraro et al., 2016). Properly disposing of secondhand apparel provides sellers with the hedonic satisfaction that they seek by avoiding harmful alternative methods of disposal, such as landfills, burning, and forcing unwanted goods onto less fortunate societies of people.

The finding that sellers are motivated by environmental concerns aligns with broader literature on pro-environmental behavior. The correlation between normative goals and pro-environmental behaviors is covered extensively in the existing literature. Previous research has suggested that an individual will likely act upon normative, environmentally beneficial behaviors, even when hedonic and gain goals are present (Steg et al., 2014). Additionally, there is sufficient reason to believe that a desire for normative acceptance has led humanity to avoid behaviors that exude negative effects on our environment. However, the link between awareness and action is not automatic and is often mediated by a well-documented ‘knowledge-action gap’ (S. Wang et al., 2025). Our study shows that apparel resale can serve as one concrete pathway for environmentally aware individuals to bridge this gap.

Considerable nudging to conform to societal norms, parlayed with the hyper-awareness of online apparel-resale platforms (i.e., Depop, Vestiaire Collective, and Poshmark), has led to a robust population of fashion resale practitioners. According to ThredUp (2025), an industry-leading resale-as-a-service company, and their annual resale report, online marketplaces will account for over 50% of the U.S. resale market. According to Lindenberg and Steg (2007), normative goals cause an individual to behave in the correct way, contribute to a sustainable environment, and demonstrate exceptional behavior.

5. Conclusions

In summary, this study identified four central themes that describe the intertwined, yet conflicting, motivations towards apparel resale: (1) financial incentives of apparel resale, (2) constant quest for convenience, (3) hedonic and emotional motivations for reselling secondhand apparel, and (4) contribution towards a sustainable future. While some themes proved to be more relevant than others, the thematic data analysis uncovered existing symbiotic relationships among the various themes and their influences on the decision to resell clothing items and their channel choice making.

First and foremost, participants prioritized their need for peak ROI, unveiling their willingness to search for higher profits while avoiding high resale platform-related service fees. Without being deliberately provoked, each of the 10 participants stated that making a profit was an important factor in their decision to resell clothing items. Participants were initially reserved in their articulation of financial desire, but as each conversation unfolded, it became apparent that seeking financial compensation was an important prerequisite in their apparel recycling decisions. After the proverbial band-aid was removed, participants began to share gain goals that can be summarized in the following buckets: (1) selling clothes as a means for making money, (2) selling clothes as a mechanism to afford new styles, (3) avoidance of high fees and costs, and (4) an objective to buy low and sell high.

While financial motivations were prevalent, participants revealed a second theme, stating that convenience and quickness of sale are important factors when deciding to resell used apparel. All but one participant referred to some form of the hierarchical decision-making process when analyzing the various apparel resale methodologies to choose from. In the context of a constant quest for convenience, participants alluded to choosing the fastest route if they had a large volume of used clothing to offload. Most participants stressed the importance of a quick sale and credited immediate satisfaction as being an integral part of a positive resale experience. The need for convenience during the reselling experience was addressed during the interviews in the following ways: (1) vast accessibility and convenience, (2) quick sale for a busy lifestyle, and (3) reselling in-person versus reselling online.

Study participants stressed that through building a community by sharing their secondhand clothes with the community and decluttering their closet, they experienced hedonic pleasure and felt less guilty about their over-consumption. It is important to note that the social values of apparel reselling were important bases for their hedonic value that they gained from the process. Last but not least, some of our participants commented on their strong commitment to sustainable practices through thrifting and reselling behavior instead of brand-new clothing purchases. They certainly recognized the concerns for the environmental issues caused by overconsumption. Based on our findings, the conceptual model containing emerging themes and sub-themes is presented in Figure 3. Moreover, this research demonstrates that apparel resale is not merely an economic activity but also a tangible low-carbon behavior. It represents a practical means for individuals to translate abstract environmental values into action, thereby addressing the knowledge-action divide discussed in studies on sustainable consumption (S. Wang et al., 2025).

6. Implications, Limitations, and Future Research

6.1. Implications for Educators and Scholars

While there are obvious economic contributions to this research, as the fashion resale industry is expected to reach USD 1.9 billion by 2023 (Shrivastava et al., 2021), its primary impact can be measured through an increased understanding and awareness of resellers’ needs and values, from an academic standpoint. The relationship between an individual consumer and their garments seems to be shifting towards one of more temporary ownership (Lang & Armstrong, 2018). As apparel reselling becomes increasingly more prevalent and more convenient with technological advancements (Kim-Vick & Yu, 2023), the need for research that analyzes the various needs and values of resellers will become progressively more necessary. Therefore, the demand for apparel resale research from sellers’ perspectives will continue to increase, but as it currently stands, there remains a visible gap in relevant, existing literature.

Additionally, this research demonstrates the harmonious relationship between the two theories (Consumption Values Theory and the Goal-Framing Theory). Educators stand to benefit from this conclusion by possibly further exploring compatibility and the two theories, from a seller’s perspective, rather than the traditional consumer-focused outlook. Future researchers may explore comparative studies across various platforms regarding the users’ usage motivations. This study could help us deepen our understanding of possible differences and similarities regarding motivations among existing users of those platforms. The current research can serve as a useful launch pad for future fashion scholars, as they look to analyze the correlation between fashion resellers and their repurchase intentions post-sale. In addition, a future study may investigate the longitudinal analyses of the resale motivations who have engaged in these sustainable practices to learn how their resale motivations progress throughout their journey of apparel reselling.

6.2. Implications for the Resale Industry

The impact of this research extends beyond simple economic gain, as it contributes to the continued effort to bring much-needed sustainable practices (in our paper, apparel resale) to the fashion industry. Increased awareness and understanding of various fashion resale channels will presumably lead to consumers replacing a percentage of their wardrobes with more secondhand clothing. This has already been proven true in ThredUp’s (2025) annual resale report, as it states that secondhand apparel has surpassed fast fashion in terms of average closet share. Closet share can be defined as an overview of the contents found in one’s closet, displayed as a percentage for each category (i.e., a closet contains roughly 50% secondhand, 25% fast-fashion, 25% off-price). This trend should prove to be beneficial for the environment as well, as it has been theorized that a 10% increase in secondhand apparel consumption will save 4% of water and 3% carbon per ton of clothing (Styvén & Mariani, 2020).

Based on the findings regarding the monetary gain and convenience of platforms as two of the most significant goals when selling apparel, we recommend that the apparel resale industry stress these gain goals or functional values when promoting their platforms to their target market, especially Gen Z. In addition, a hedonic aspect-driven target market would better respond to the promotional message highlighting the feel-good factors when they choose a certain channel for their apparel resale. Last but not least, the fashion resale industry must develop a stronger strategy to persuade its target market to take action toward what the target market believes in. Per a recent study, Gen Z consumers deeply care about their normative gain, along with the financial gain, due to the current state of their disposable income level (Kim-Vick & Yu, 2023). It may be more suitable to emphasize both goals in the marketing message to win their participation in the apparel resale to advance the sustainable practices in the industry.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Although there is sufficient evidence to suggest that this study offers useful findings for both academic and industry settings, there are several limitations. First, the current study employed an interpretive approach to investigate the consumers’ motivations regarding selling their secondhand apparel in the resale industry. Thus, it has the innate subjective nature of qualitative interpretation and the potential for researcher influence. Second, the small sample size is a possible limitation found in this study. However, it should be noted that previous studies confirm the subjectivity of sample size as it pertains to qualitative research (Marshall et al., 2013), while others suggest that selecting sample size is all relative depending on the study at hand (Sandelowski, 1995). Based on the growing interests among Gen Z regarding sustainable consumption, we intended to reveal their reselling behavior and motivations to better inform academia and the industry. Because of the demographic skew where 70% of the informants are Gen Z, the findings should be carefully interpreted as well. Thirdly, limitations existed in the form of technological difficulties, with Microsoft Teams proving to be the main culprit. Microsoft Teams was used to conduct, record, and transcribe the interviews, although the transcription was oftentimes unrecognizable when compared to the original audio. Future researchers may want to consider using alternative recording equipment to avoid these issues. Fourthly, due to a lack of time, the overall scope of the study was marginally limited to fit a strict research schedule. Future research could expand upon the findings from this study using a representative sample. Getting an accurate depiction of the apparel resale industry that reflects the characteristics of the market at large will help drive the narrative of the secondhand resale boom. Last but not least, there are additional avenues that we identified for future research in relation to governmental policy. Currently, industry-standardized guidelines are designed and enforced by the Federal Trade Commission. Using a barcode or a radio frequency identification tag, the industry could explore the opportunity of an easily traceable garment lifespan. Moreover, investigating a consumer’s perception and behavioral intention toward bringing their garments back to the retailers for repair, resale, or recycling responsibly. This way, the responsibility of proper disposal is redirected back toward the ones creating the issue (the brands) for a more sustainable fashion industry down the road.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H. (Jack Herman) and J.K.-V.; methodology, J.H. (Jack Herman), J.K.-V. and J.H. (Jonghan Hyun); software, J.H. (Jack Herman); validation, J.K.-V. and J.H. (Jonghan Hyun); formal analysis, J.H. (Jack Herman) and J.H. (Jonghan Hyun); investigation, J.H. (Jack Herman); resources, J.K.-V. and J.H. (Jonghan Hyun); data curation, J.H. (Jack Herman); writing—original draft preparation, J.H. (Jack Herman); writing—review and editing, J.K.-V. and J.H. (Jonghan Hyun); visualization, J.H. (Jack Herman); supervision, J.K.-V. and J.H. (Jonghan Hyun); project administration, J.K.-V. and J.H. (Jonghan Hyun). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Kent State University Institutional Review Board (protocol code 22-529) on 6 December 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author in writing.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Jack Herman is employed by FD Finish Line. His employment does not present any financial or non-financial conflicts of interest regarding the manuscript under consideration. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ahmad, N., Salman, A., & Ashiq, R. (2015). The impact of social media on fashion industry: Empirical investigation from Karachiites. Journal of Resources Development and Management, 7, 1–8. Available online: https://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/JRDM/article/view/21748/21876 (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Armour, M., Rivaux, S. L., & Bell, H. (2009). Using context to build rigor: Application to two hermeneutic phenomenological studies. Qualitative Social Work, 8(1), 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awuni, J. A., & Du, J. (2016). Sustainable consumption in Chinese cities: Green purchasing intentions of young adults based on the theory of consumption values. Sustainable Development, 24(2), 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, S. J., & Mattsson, J. (2017). Understanding collaborative consumption: Test of a theoretical model. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 118, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H., & Liao, S. (2007). Exploring consumer resale behavior in C2C online auctions: Taxonomy and influences on consumer decisions. Academy of Marketing Science Review, 2007, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, H., & Liao, S. (2010). Buying while expecting to sell: The economic psychology of online resale. Journal of Business Research, 63(9–10), 1073–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. (2017). ERP for textiles in the USA. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/epr-for-textiles-in-the-usa#:~:text=As%20the%20rate%20at%20which,environmental%20impact%20of%20this%20waste (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- Ertz, M., Durif, F., & Arcand, M. (2016). Business in the hands of consumers: A scale for measuring online resale motivations. Expert Journal of Marketing, 4(2), 60–76. Available online: http://marketing.expertjournals.com/23446773-408/ (accessed on 13 November 2021). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, C., Sands, S., & Brace-Govan, J. (2016). The role of fashionability in second-hand shopping motivations. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 32, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzola, P., Pavione, E., Pezzetti, R., & Grechi, D. (2020). Trends in the fashion industry. The perception of sustainability and circular economy: A gender/generation quantitative approach. Sustainability, 12(7), 2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Given, L. M. (2008). Semi-structured interview. In L. M. Given (Ed.), The sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, H. M., Lourenço, T. F., & Silva, G. M. (2016). Green buying behavior and the theory of consumption values: A fuzzy-set approach. Journal of Business Research, 69(4), 1484–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiot, D., & Roux, D. (2010). A second-hand shoppers’ motivation scale: Antecedents, consequences, and implications for retailers. Journal of Retailing, 86(4), 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J., Sjöklint, M., & Ukkonen, A. (2016). The sharing economy: Why people participate in collaborative consumption. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 67(9), 2047–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, I., & Khan, K. (2020). An extension of the goal-framing theory to predict consumer’s sustainable behavior for home appliances. Energy Efficiency, 13(7), 1441–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haws, K. L., Winterich, K. P., & Naylor, R. W. (2013). Seeing the world through GREEN-tinted glasses: Green consumption values and responses to environmentally friendly products. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 24(3), 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H., & Harris, L. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on corporate social responsibility and marketing philosophy. Journal of Business Research, 116, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, J., & Kim-Vick, J. (2023). A state of fashion re-commerce: From operational perspectives. International Textile and Apparel Association Annual Conference Proceedings, 80(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W., Yoo, J., & Chung, T. (2012). The consumption values and consumer innovativeness on convergence products. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 112(5), 688–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joung, H. M., & Park-Poaps, H. (2013). Factors motivating and influencing clothing disposal behaviours. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 37(1), 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S., & Jin, B. (2014). A theoretical investigation of slow fashion: Sustainable future of the apparel industry. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 38(5), 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S., & Jin, B. (2016). Sustainable development of slow fashion businesses: Customer value approach. Sustainability, 8(6), 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I., Jung, H. J., & Lee, Y. (2021). Consumers’ value and risk perceptions of circular fashion: Comparison between secondhand, upcycled, and recycled clothing. Sustainability, 13(3), 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N. L., & Jin, B. E. (2020). Why buy new when one can share? Exploring collaborative consumption motivations for consumer goods. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 44(2), 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim-Vick, J., & Yu, U. J. (2023). Impact of digital resale platforms on brand new or second-hand luxury goods purchase intentions among US Gen Z consumers. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 16(1), 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitala, K. (2014). Consumers’ clothing disposal behaviour—A synthesis of research results. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 38(5), 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C., & Armstrong, C. M. J. (2018). Fashion leadership and intention toward clothing product-service retail models. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 22(4), 571–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. H., & Rhee, B.-D. (2021). Retailer-run resale market and supply chain coordination. International Journal of Production Economics, 235, 108089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenberg, S., & Steg, L. (2007). Normative, gain and hedonic goal frames guiding environmental behavior. Journal of Social Issues, 63(1), 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, J., & Sisodia, R. (2012). Conscious capitalism—Unleashing human energy and creativity for the greater good. DR Creative Intelligence. Available online: https://rajsisodia.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Conscious-Capitalism-Unleashing-human-energy-and-creativity-for-the-greater-good.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2021).

- Marshall, B., Cardon, P., Poddar, A., & Fontenot, R. (2013). Does sample size matter in qualitative research? A review of qualitative interviews in IS research. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 54(1), 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, J. A. (2008). Designing a qualitative study. In L. Bickman, & D. J. Rog (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of applied social research methods (pp. 214–253). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medalla, M. E., Yamagishi, K., Tiu, A. M., Tanaid, R. A., Abellana, D. P. M., Caballes, S. A., Jabilles, E. M., Himang, C., Bongo, M., & Ocampo, L. (2020). Modeling the hierarchical structure of secondhand clothing buying behavior antecedents of millennials. Journal of Modelling in Management, 15(4), 1679–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M., Ozuem, W., Howell, K., & Ranfagni, S. (2023). A step-by-step process of thematic analysis of a conceptual model in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 22, 16094069231205789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H., & Joyner Armstrong, C. M. (2019). Is money the biggest driver? Uncovering motives for engaging in online collaborative consumption retail models for apparel. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 51, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelowski, M. (1995). Sample size in qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health, 18(2), 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J. N., Newman, B. I., & Gross, B. L. (1991). Why we buy what we buy: A theory of consumption values. Journal of Business Research, 22(2), 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, A., Jain, G., Kamble, S. S., & Belhadi, A. (2021). Sustainability through online renting clothing: Circular fashion fueled by Instagram micro-celebrities. Journal of Cleaner Production, 278, 123772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, J. D., & Coughlan, A. T. (2007). Used goods, not used bads: Profitable secondary market sales for a durable goods channel. Quantitative Marketing and Economics, 5, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista Research Department. (2024, October 1). U.S. apparel and footwear resale market—Statistics & facts. Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/5161/apparel-and-footwear-resale-in-the-us/#topicOverview (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Steg, L., Bolderdijk, J. W., Keizer, K., & Perlaviciute, G. (2014). An Integrated Framework for Encouraging Pro-environmental Behaviour: The role of values, situational factors and goals. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 38, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styvén, E. M., & Mariani, M. M. (2020). Understanding the intention to buy secondhand clothing on sharing economy platforms: The influence of sustainability, distance from the consumption system, and economic motivations. Psychology & Marketing, 37(5), 724–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorisdottir, T. S., & Johannsdottir, L. (2020). Corporate social responsibility influencing sustainability within the fashion industry. A systematic review. Sustainability, 12(21), 9167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ThredUp. (2025). ThredUp resale report 2025. Available online: https://cf-assets-tup.thredup.com/resale_report/2025/ThredUp_Resale_Report_2025.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Turunen, L. L. M., Cervellon, M. C., & Carey, L. D. (2020). Selling second-hand luxury: Empowerment and enactment of social roles. Journal of Business Research, 116, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B., Fu, Y., & Li, Y. (2022). Young consumers’ motivations and barriers to the purchase of second-hand clothes: An empirical study of China. Waste Management, 143, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Mbanyele, W., Feng, T., Khan, S., & Fan, S. (2025). Bridging the knowledge-action divide: Environmental awareness and low-carbon behaviors of Chinese university students. Humanities & Social Sciences Communication, 12, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C. C., & Paddock, C. (2003). The meanings of informal and second-hand retail channels: Some evidence from Leicester. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 13(3), 317–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L., Keh, H. T., & Wang, X. (2021). Powering sustainable consumption: The roles of green consumption values and power distance belief. Journal of Business Ethics, 169(3), 499–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).