Abstract

The development of sustainable self-compacting concrete (SCC) requires alternative binders that minimise ordinary Portland cement (OPC) consumption while ensuring long-term performance. This study investigates sulfate-activated SCC (SA SCC) incorporating high volumes of industrial by-products, whereby 72% ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBS) and 18% fly ash (FA) were activated with varying proportions of OPC and gypsum. Quarry dust was used as a fine aggregate, while granite and electric arc furnace (EAF) slag served as coarse aggregates. Among all formulations, the binder containing 72% GGBS, 18% FA, 4% OPC, and 6% gypsum was identified as the optimum composition, providing superior mechanical performance across all curing durations. This mix achieved slump flow within the EFNARC SF2 class (700–725 mm), compressive strength exceeding 50 MPa at 270 days, and flexural strength up to 20% higher than OPC SCC. Drying shrinkage values remained below Eurocode 2 and ASTM C157 limits, while EAF slag increased density, but slightly worsened shrinkage compared to granite mixes. Microstructural analysis (SEM-EDX) confirmed that strength development was governed by discrete C-S-H and C-A-S-H gels surrounding unreacted binder particles, forming a dense interlocked matrix. The results demonstrate that sulfate activation with a 4% OPC + 6% gypsum blend enables the production of high-performance SCC with 94–98% industrial by-products, reducing OPC dependency and environmental impact. This work offers a practical pathway for low-carbon SCC.

1. Introduction

The cement industry is a major contributor to anthropogenic CO2 emissions due to the high clinker content in ordinary Portland cement (OPC). Although the clinker-to-cement ratio is projected to decrease from 0.71 in 2020 to 0.50 by 2050, this reduction is insufficient to achieve the net-zero targets required by mid-century [1]. To accelerate decarbonisation, alternative cementitious binders have been developed to reduce clinker use and to incorporate industrial by-products. Geopolymer and alkali-activated binder systems have shown considerable promise, as they can incorporate large volumes of iron slag and fly ash (FA), thereby reducing reliance on natural resources and diverting waste from landfills [2,3,4,5]. However, their practical application remains limited because these binders require chemical alkali activators to react effectively. The most common activators are alkali hydroxides, carbonates, and silicates, either alone or in combination [2,3,4,5]. In addition, such systems often require high-temperature curing and involve the synthesis of strongly alkaline media, both of which increase energy consumption and limit industrial scalability [5,6].

By contrast, sulfate-based activators are less frequently studied, as their low alkalinity resembles neutral salts. Compared with alkali silicates and hydroxides, their use has been associated with slower early-age strength development [6]. Nonetheless, sulfates are readily available as by-products from chemical industries [7], and several compounds, including calcium sulfate anhydrite (CaSO4) [8] and its derivatives such as gypsum and hemihydrate, sodium sulfate (Na2SO4) [9,10,11,12,13], magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) [14], and potassium sulfate (K2SO4) [15] have been investigated. Gypsum, in particular, can activate slag binders at dosages as low as 2% by mass [16]. Such binders often show significant strength development beyond 28 days [16,17], sometimes surpassing OPC or Portland slag cement [17]. Early strength can also be improved when gypsum is combined with other calcium sources such as quicklime or OPC [8]. Unlike CaSO4 and its derivatives, Na2SO4 activation is highly pore-dependent; supersaturation is reached more quickly in finer-pored systems, but if not properly controlled, it can induce internal stress and cracking during prolonged curing [18,19].

Research on self-compacting concrete (SCC) with geopolymer or alkali-activated binders remains limited due to the complex interactions among chemical activators, superplasticizers (SP), and viscosity-modifying agents. Compared with conventional concrete, alkali-activated SCC requires both high concentrations of activators and high SP dosages, typically 2–7% of binder mass [20,21,22] and 8–14 M NaOH solutions [21,23,24,25,26]. These requirements hinder practical implementation and increase embodied energy. In parallel, recent studies have investigated heavyweight aggregates such as steel slag [27], copper slag [28], basalt, and magnetite [24]. While these aggregates have been applied in conventional heavyweight concretes, only limited studies have explored their use in alkali-activated SCC [24,29,30], largely due to the risk of segregation arising from their high density.

Although numerous studies have examined alkali-activated binders and slag–fly ash systems, investigations on sulfate-activated self-compacting concrete (SA-SCC) remain limited, particularly those integrating multiple industrial by-products such as GGBS, fly ash, and EAF slag aggregates within a single system. This study advances current knowledge by (i) developing a sulfate-activated binder composed almost entirely of industrial waste, (ii) employs a dual-activator system consisting of OPC and gypsum, (iii) comparing its performance across two aggregate systems (granite vs. EAF slag), and (iv) establishing a relationship between mechanical performance and microstructural evolution over long-term curing. These contributions fill a critical gap in understanding the performance of non-alkali-activated SCC formulations that achieve self-compaction and strength gain through sulfate–calcium synergy rather than high-alkali chemistry. The use of sulfate-activated (SA) slag-FA binders offers a promising pathway to overcome these challenges by reducing dependence on high-alkalinity chemical activators while promoting large-scale utilisation of industrial by-products. This approach not only reduces reliance on natural resources but also mitigates the environmental issues associated with iron and steel slag disposal. Therefore, this study investigates the development of SA SCC incorporating high volumes of FA, iron slag, and steel slag. The fresh and hardened properties of the produced mixes were systematically evaluated to establish their suitability as a sustainable alternative to OPC-based SCC.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

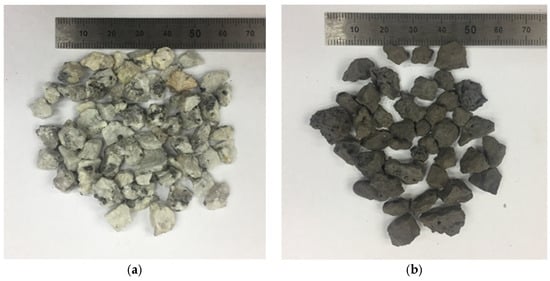

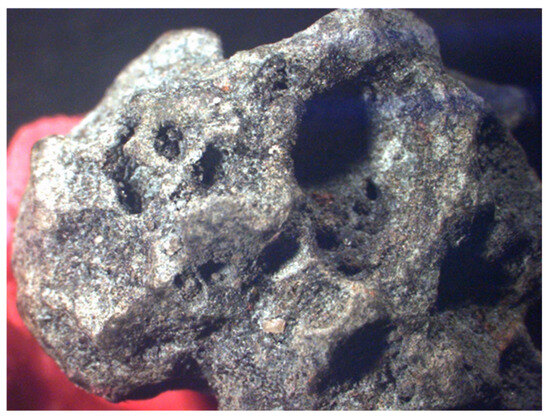

The ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBS), fly ash (FA), ordinary Portland cement (OPC) and gypsum used in this study are shown in Figure 1a–d. The GGBS used had a specific gravity of 2.89, while Class F FA had a specific gravity of 2.22. OPC (CEM I 42.5 N) with a specific gravity of 2.80 and gypsum (95% CaSO4·2H2O) with a specific gravity of 2.40 were employed as the sulfate activator components. The oxide compositions of gypsum were determined by XRF and are summarised in Table 1. Coarse aggregates used in this study were crushed granite with a specific gravity of 2.70 and electric arc furnace (EAF) slag with a specific gravity of 3.20. Both coarse aggregates had a maximum grading size of 10 mm. The water absorption rate of EAF slag is 2.3% and 0.6% for crushed granite, and the EAF slags were soaked in water overnight and dried to the saturated surface dry condition before use. The EAF slag aggregates were pre-soaked and oven-dried to a saturated surface-dry (SSD) condition to mitigate variable water absorption during mixing, ensuring consistent workability [31]. The geometry of the crushed granite was observed to have angular geometry with well-defined edges, as shown in Figure 2a, similar to EAF coarse aggregate, as shown in Figure 2b, with the addition of rough and honeycombed surface textures, as shown in Figure 3. Fine aggregates were quarry dust (QD) with a specific gravity of 2.68 and a maximum aggregate size of 5 mm. The QD was sieved and washed to eliminate the fine particles with a diameter of less than 75 µm and subsequently dried to saturated surface dry conditions prior to fabrication of the mixes. Polycarboxylate-based SP was used as a water-reducing agent and locally available tap water as mixing water for all mix designs.

Figure 1.

(a) GGBS, (b) FA, (c) OPC and (d) gypsum.

Table 1.

The chemical compositions of gypsum via XRF analysis.

Figure 2.

(a) Crushed granite and (b) EAF slag.

Figure 3.

The image of EAF slag under 1.5× magnification level.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Mixture Proportioning

The binder content used for SCC was fixed at 550 kg/m3 and the fine-to-coarse aggregate ratio was maintained at 0.4: 0.6. The GGBS and FA were kept at 72% and 18% by total binder weight, which corresponds to the ratio of 4:1. The ratio was selected based on prior optimisation work on supersulfated self-compacting concrete systems, which demonstrated that this proportion provides higher strength and reactivity [31]. The remaining 10% of the binder was filled with OPC-gypsum activator at 2 to 10% with a step increment of gypsum or reduction in OPC by 2%. Thus, the mix design with 0% gypsum and 10% OPC was designated as PC0WG2. The SP dosage was fixed at 0.6% by total binder weight. 14 mix designs are classed in series G and series E, differentiated by the type of coarse aggregate used. Series G and series E used crushed granite and EAF slag as coarse aggregates, respectively. The mix design shown in Table 2 was performed using the modified absolute volume method prescribed in ACI 211.1 [32] to achieve the desired slump flow requirement of SF class 2 of BS EN 206 [33].

Table 2.

Final mix design for long-term testing of SCC containing granite stone (Series G) and EAF slag (Series E) coarse aggregate.

2.2.2. Mixing, Forming and Curing

The SCC mix was homogenised using a standard epicyclic mixer with a maximum capacity of 80 litres. The mixing process started with dry mixing all binder constituents and aggregates at a low mixing speed for 5 min. Water was gradually added throughout the mixing process, up to a maximum of 5 min. Following the addition of 90% of total water, the remaining water with SP was added. A further mixing was carried out for another 2 min before being tested for fresh properties. The SCC was later cast into their respective mould without vibrating and demoulded after 24 ± 2 h. The SCC was left cured by wrapping in a plastic sheet and stored at a room temperature of 27 ± 2 °C with a relative humidity range from 60 to 70% except for specimens used for the drying shrinkage test. These procedures were applied identically to both granite–aggregate (Series G) and EAF–slag–aggregate (Series E) SCC mixes.

2.2.3. Fresh, Hardened and Microstructure Properties

The slump flow test was conducted based on the method prescribed in BS EN 12350: Part 8 [34] to test the flowability of SCC to achieve the slump flow of 660 to 750 mm. Bulk density was determined on 100 × 100 × 100 mm3 cubes following BS EN 12390-7 [35]. Concrete prisms with edge dimensions of 40 × 40 × 160 mm3 were fabricated and tested under BS EN 197: Part 1 [36] to determine the compressive and flexural strength of the hardened SCC.

The drying shrinkage test was conducted based on BS ISO 1920: Part 8 [37] with 75 × 75 × 285 mm3 mould size. All tests were conducted after cured at 7, 28, 56, 91, 182, and 270 days with additional testing at 1, 3 and 112 curing days for shrinkage. Specimens were stored in a controlled laboratory environment throughout the drying period. The microstructure of selected SA SCC was examined in terms of morphology and composition changes at curing ages of 7 and 182 days by scanning electron microscopy (SEM)and energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) (FEI Quanta FEG 650, FEI Company, Eindhoven, The Netherland) spectroscopy. Samples were solvent-stopped, vacuum-dried, impregnated with epoxy and polished prior to SEM imaging. EDX spot and area analyses were used to determine Ca/Si and Ca/Al ratios of the main hydration products. At least three samples per mix for all testing ages were reported, as well as the mean value.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Slump Flow Test

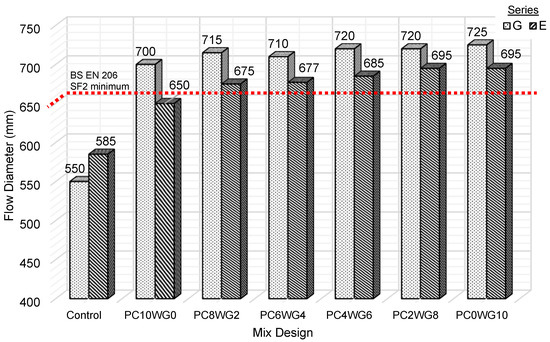

According to BS EN 206 [33], the SCC with workability class of SF2 should have a diameter range from 660 to 750 mm and suitable for SCC applications. Based on Figure 4, all mix designs fall between the SF2 workability class except control G and E SCC. The mixes could not achieve the required flow diameter of the SF2 workability class even with a significantly higher w/b ratio of 0.47. A further increase in the w/b ratio of both control mixes only cause severe bleeding and segregation. The smooth surface of GGBS particles, rather than the angular and rough surface OPC particles, was credited with the exceptional workability of SA SCC mixes [38]. In comparison, SCC in series G exhibited a higher flow diameter than series E. The SA SCC in series G exhibited a flow diameter of 700 to 725 mm, while series E exhibited relatively lower flow values in the range from 650 to 695 mm. The porous and rough surface EAF slags result in a stronger bonding, thus enhancing the aggregates and binder paste interface. However, it provided an inadequate lubricating effect and high-friction resistance that reduced workability [39]. Increasing the gypsum activator while lowering the OPC also increases the flow diameter for both series. The lower slump flow of control SCC compared to SA SCC was also due to the lower relative density of its binder combination. The low relative density of GGBS, FA and gypsum increases the total paste volume, which subsequently improves the workability of the SA SCC mix [40].

Figure 4.

Slump flow diameter for control and SA SCC for series G and E.

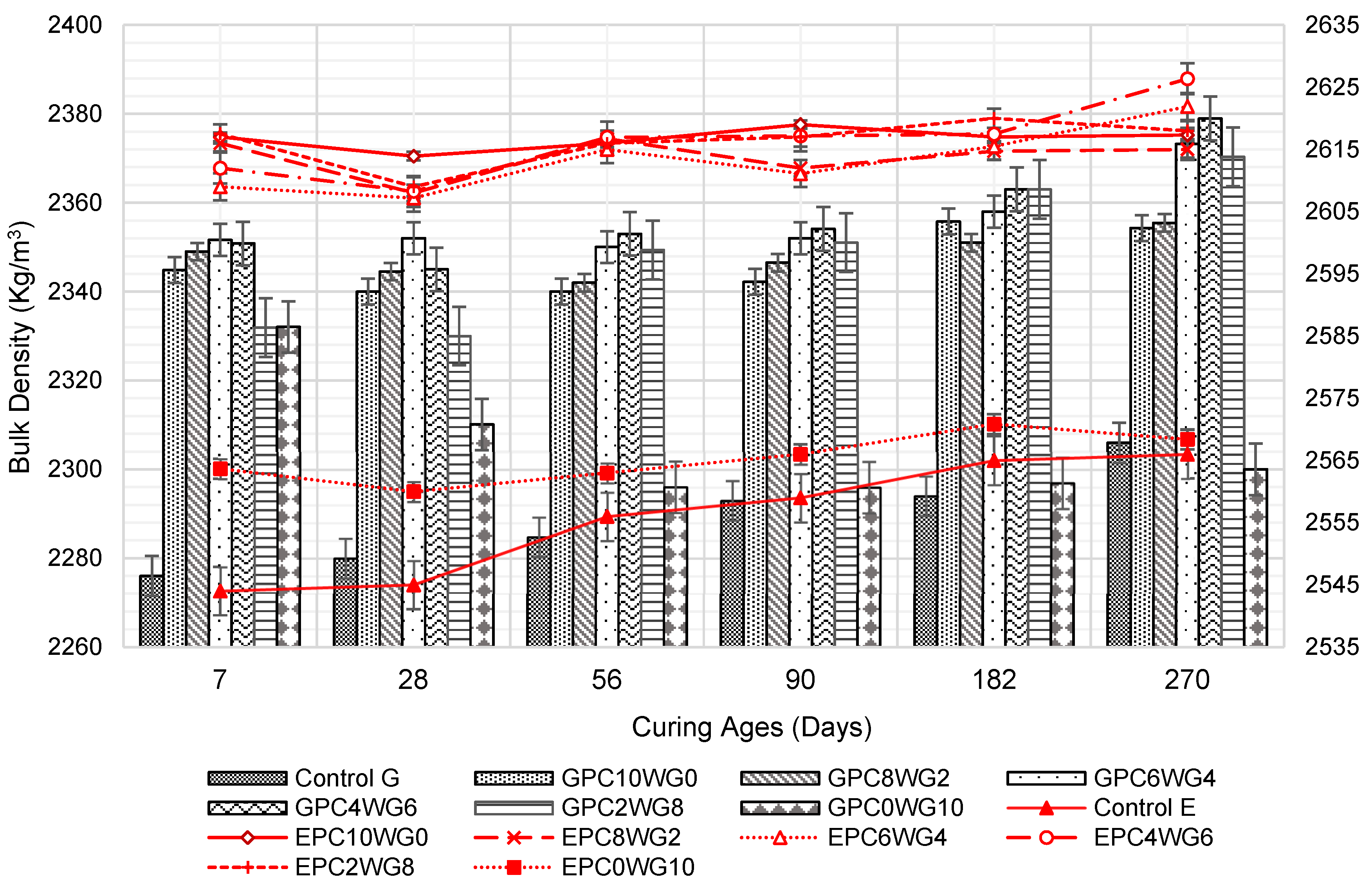

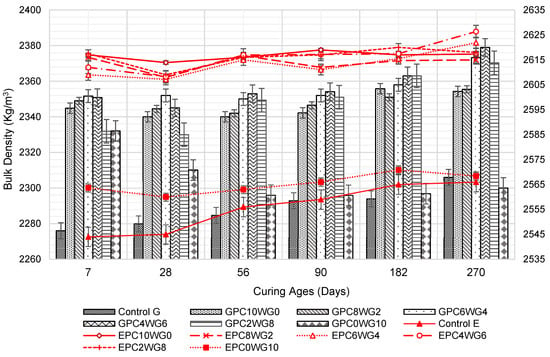

3.2. Bulk Density

At all curing ages, the bulk density of the SCC mixes shown in Figure 5 is within the normal-weight concrete range, and it is lower when crushed granite is used as coarse aggregate rather than EAF slag. It was predominantly due to the high density of EAF slag coarse aggregate [41,42]. Control G and E show the relatively low bulk density at the testing ages up to 180 days before surpassing GPC0WG10 at 270 days due to the high-water content of the mix that resulted in the high porosity of the SCC. Nevertheless, the bulk density of the mix shows a significant increase in prolonged curing duration. Between 7 and 28 days, there was a modest decrease in bulk density, which gradually increased when the curing time was extended from 28 to 270 days. The loss of moisture from the specimens caused the bulk density of the mixtures to drop. The SCC mix design contained a high volume of GGBS, and FA and composition are known for its slow hydration process, which delayed forming the dense C-S-H gel framework to prevent moisture loss at an early age [43]. GPC4WG6 exhibited the highest bulk density in series G, with 2363 and 2379 kg/m3 at 182 and 270 days, respectively.

Figure 5.

Bulk density of control and SA SCC for series G and E.

A similar trend was observed in series E whereby a marginal decline in bulk density was observed in all SA mixes between 7 days and 28 days for the same reason as discussed earlier. However, when the curing duration was extended from 28 days to 270 days, the bulk density of the mixes increased marginally. The EAF slag SCC had the highest bulk density at all curing ages up to 270 days. The observation is consistent with series G mixes. The increase in bulk density for SA SCC 2–4% of OPC and 8–6% gypsum was due to the rise in packing capacity between particles, and this can influence the mechanical properties of SCC whereby the same mix designs also provide higher strength performance.

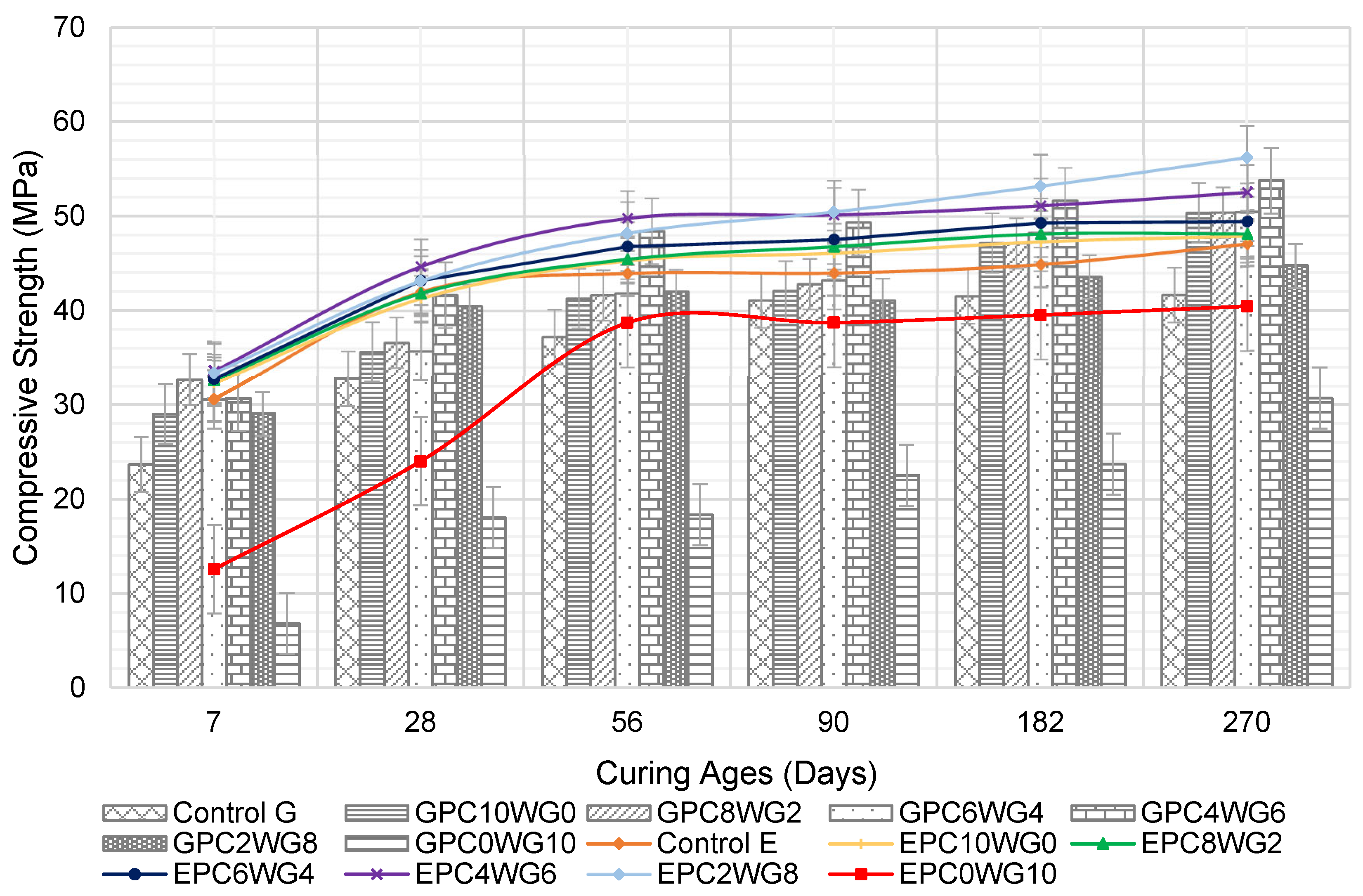

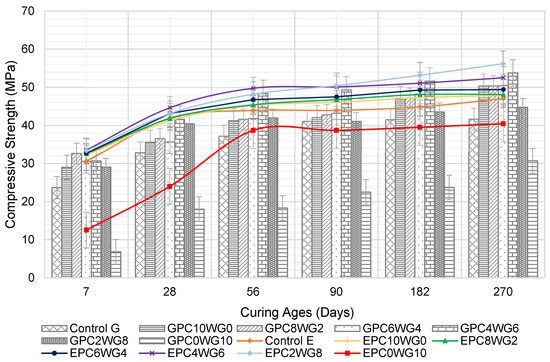

3.3. Compressive Strength

The compressive strength development for SCC for the curing period up to 270 days is presented in Figure 6. At 7 days, the partial substitution of OPC with 2% gypsum in the SA SCC resulted in increased compressive strength for GPC8WG2 with 32.65 MPa. It resulted from the sufficient hydroxyl ions released during OPC hydration, which dissolved and degraded the glassy GGBS structure, resulting in increased hydration [44]. When the gypsum content was increased to between 4% to 8% with a corresponding reduction in OPC content, a marginal decrease in 7 day compressive strength was observed. However, GPC0WG10 exhibited the lowest compressive strength of 6.83 MPa, which was only 28.9% of the compressive strength of control G. The absence of OPC results in no CaOH available to hydrolyse GGBS and FA glass content, simultaneously developing a solid C-S-H network from the primary hydration [45].

Figure 6.

Compressive strength of control and SA SCC for series G and E.

A substantial increase in compressive strength was observed for the GPC4WG6 mix at 28 days with 41.66 MPa. It could be due to the excess calcium sulfate available, which acted as inert fillers [46]. Regardless, the 28 day compressive strength of GPC2WG8 declined from peak value to 40.48 MPa. The compressive strength decreased sharply to 18.02 MPa when the OPC was entirely replaced by gypsum in mix GPC0WG10. Despite this, GPC0WG10 showed a drastic increase in strength at 28 days compared to 7 days. Other SA SCC in series G demonstrated substantial strength development at 28, 56, 90, 182 and 270 days, while a minimal increase in strength was observed for control SCC for curing ages of 90 days up to 270 days. Mix GPC4WG6 had the highest strength at 270 days, while GPC0WG10 had the lowest at 30.75 MPa. All mix designs except GPC0WG10 outperformed control G due to the high-water content required to achieve the predefined flow. As demonstrated in Table 2, the high water content of the control mix increased the porosity of the cured concrete, lowering its strength [47].

The compressive strength development of SA SCC with EAF slag had equivalent or higher compressive strength than control E at all ages up to 270 days except EPC10WG0. All SCC has exhibited a significant increase in strength on prolonged curing durations from 7 to 56 days. EPC4WG6 had the maximum compressive strength for the same curing period, until being overtaken by EPC2WG8 after 90 days. The sudden increase could result from the reaction of calcium carbonate precipitate available on the mesoporous surface of EAF slag on prolonging the curing age [48]. The compressive strength of series E is relatively higher than series G for the first 90 days. It could be due to the interconnected pores within EAF slag particles that supported the self-curing regime of SCC. The water absorbed within these pores supported the growth of hydration products of OPC and also SA binder on the early curing ages [49]. However, as the curing duration increased beyond 90 days, there was only a marginal increase in compressive strength for series E. The same trend was also recorded in the study by Rondi et al. [50], where, when 100% EAF slag was utilised in concrete, the concrete reached its maximum strength capacity at 120 days. At 182 days, the strength performance for series E was equivalent to series G but surpassed series G upon reaching the final curing ages of 270 days. Hence, it could be concluded that the aggregates’ density does not necessarily result in better long-term strength performance.

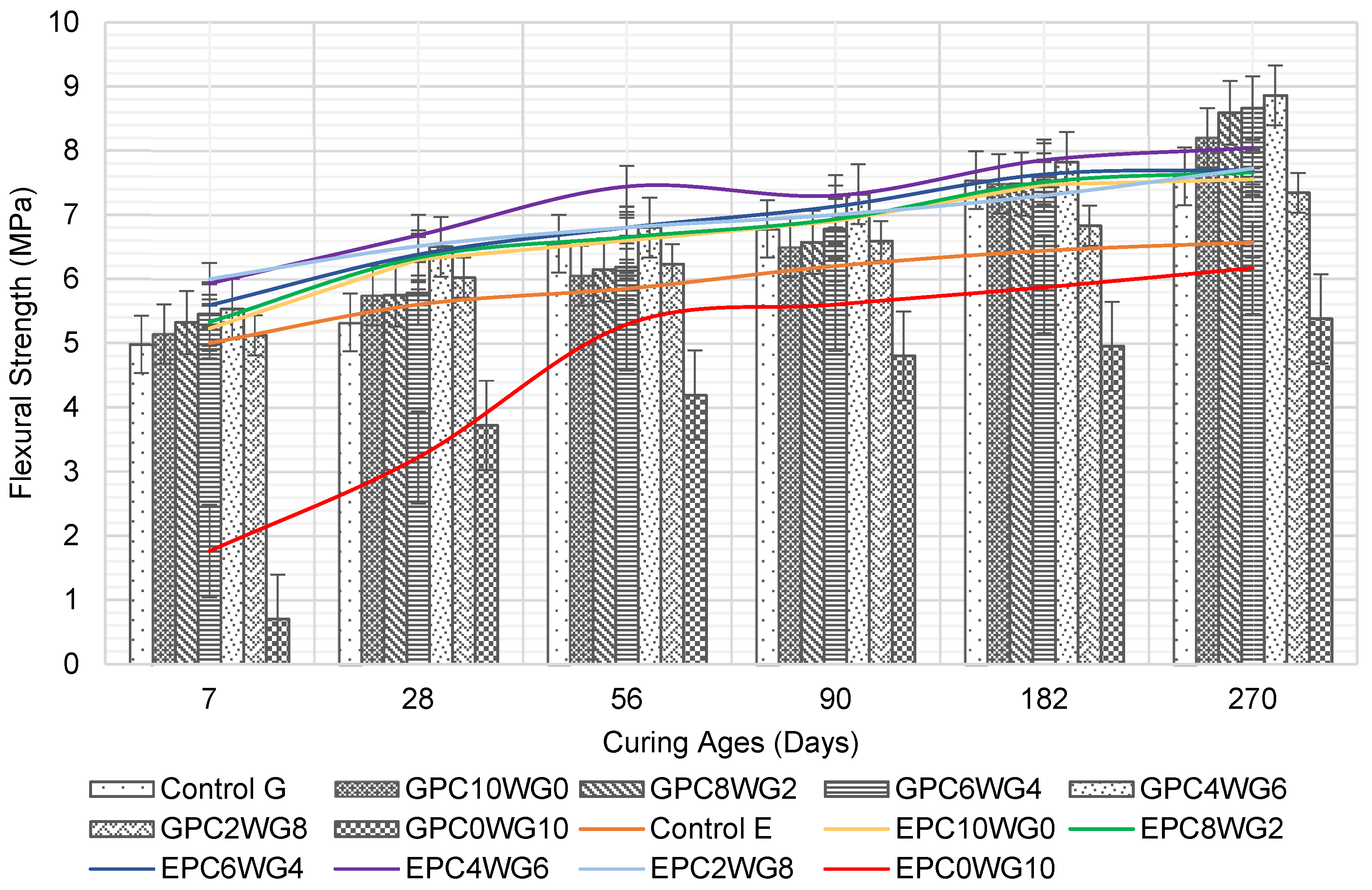

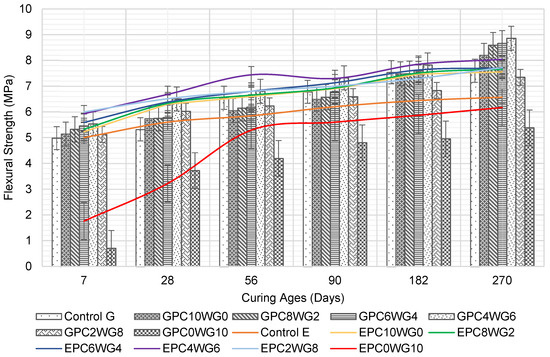

3.4. Flexural Strength

The flexural strength of SCC containing SA binder with various OPC and gypsum contents was compared with that of fully OPC SCC in Figure 7. GPC4WG6 consistently exhibited the highest flexural strength in series G. In contrast, GPC0WG10 exhibited the lowest flexural strength for all curing ages up to 270 days. Overall, all specimens in series G show a considerable increase in flexural strength as the curing age increases. At the age of 7 days, a gradual stepped replacement of OPC with gypsum up to 6% by mass (GPC4WG6) resulted in a corresponding increase in the flexural strength of 11.04% higher than control SCC. The flexural strength declined from the peak level with a further rise in gypsum content above 6% but was still higher than control SCC at 8% gypsum content. However, GPC0WG10 exhibited a sharp decline in flexural strength to 0.70 MPa or 86.94% lower than control SCC. A similar trend was observed for the flexural strength of the mixes at 28 days. At 56 and 90 days, control SCC demonstrated equivalent or slightly higher strength than SA SCC except for GPC4WG6. On a prolonged curing period of 182 days, the flexural strength of SA SCC with 0% to 6% gypsum outperformed control SCC. The hydration process of concrete containing 100% OPC had reached its plateau [51] while the GPC4WG6 was still ongoing.

Figure 7.

Flexural strength of control and SA SCC for series G and E.

The flexural strength for series E exhibited an almost similar order of magnitude as series G. All the SA SCC in series E, except EPC0WG10, outperformed the control SCC at all ages. At 7 days, the increase in the gypsum content in replacement of OPC increased the flexural strength up to 8% by mass of gypsum. EPC2WG8 achieved the highest flexural strength value of 6.0 MPa, 20% higher than the control SCC, while EPC4WG6 achieved the second-highest flexural strength value of 5.93 MPa. In subsequent ages of the concrete up to 270 days, EPC4WG6 consistently attained the peak flexural strength among all the concrete tested. EPC0WG10 continues to show a steady strength development from 28 days onward and by the age of 270 days, the flexural strength of EPC0WG10 was only 9.45% lower than the control SCC. The same mix design in series G was recorded as being 36.03% lower than their respective control mix at the same curing ages. On the final curing age, all SCC in series E had higher flexural strength than their counterpart mixes in series G. One of the main reasons for improved strength in series E was that the failure plane passed through the aggregate instead of the aggregate-paste interfacial zone during the compressive strength test. The observation is congruent with a previous related study [52], which was due to the higher angularity of the EAF slag that increased the bond strength between aggregates and the paste [53].

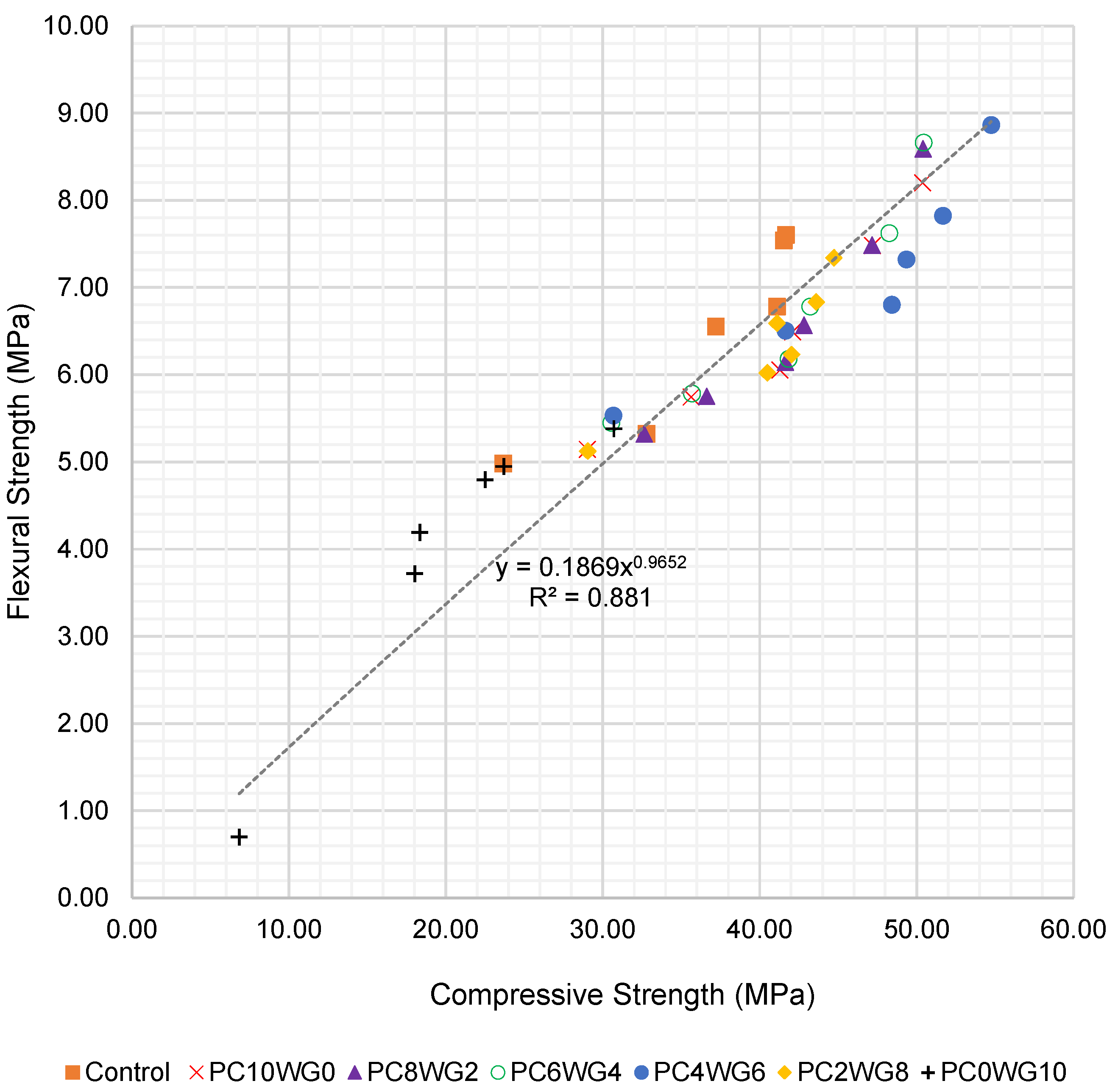

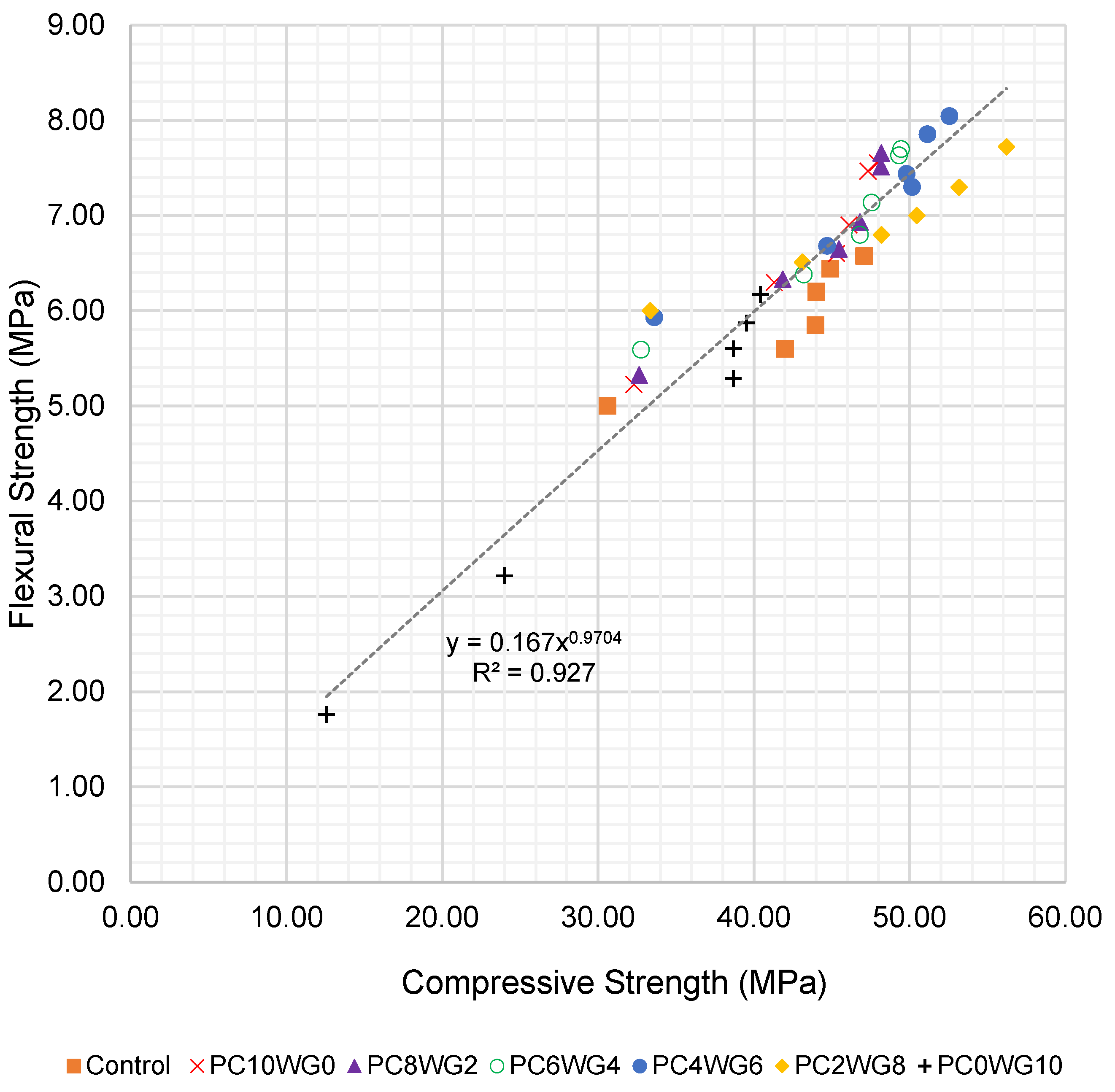

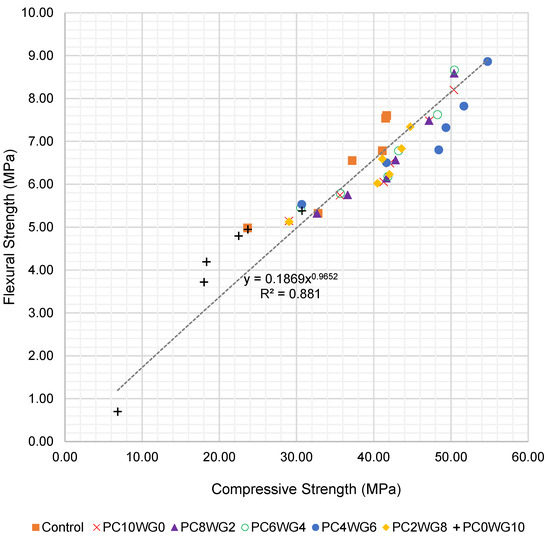

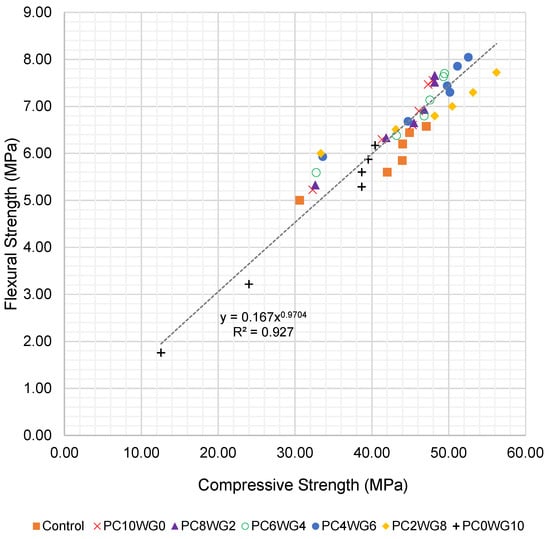

To further evaluate the relationship between compressive and flexural strength, an empirical correlation was derived using all test data from 7 to 270 days for both series G and E. The flexural strength fcf (MPa) was expressed as a power function of the corresponding compressive strength fcu (MPa), as shown in Equation (1):

where and are regression coefficients obtained by a least-squares fitting of the experimental data. For SCC with granite coarse aggregate (series G), the best-fit relationship is given in Equation (2):

fcu = kfcua

fcf = 0.187fcu0.965 (R2 = 0.881)

The corresponding regression for SCC with EAF slag coarse aggregate (series E) is given in Equation (3):

fcf = 0.167fcu0.970 (R2 = 0.927)

The regression curves for series G and series E are presented in Figure 8 and Figure 9, respectively. The exponents in Equations (2) and (3) are close to unity, indicating an almost proportional increase in flexural strength with compressive strength over the investigated range. The slightly higher coefficient of determination for series E (R2 = 0.927) suggests a tighter correlation between compressive and flexural strength when EAF slag aggregates are used. Overall, the high R2 values confirm that the proposed expressions can be used to reasonably predict flexural strength from compressive strength or vice versa for the sulfate-activated SCC mixes investigated in this study.

Figure 8.

Regression curve of compressive strength and flexural strength of SCC for series G up to 270 days.

Figure 9.

Regression curve of compressive strength and flexural strength of SCC for series E up to 270 days.

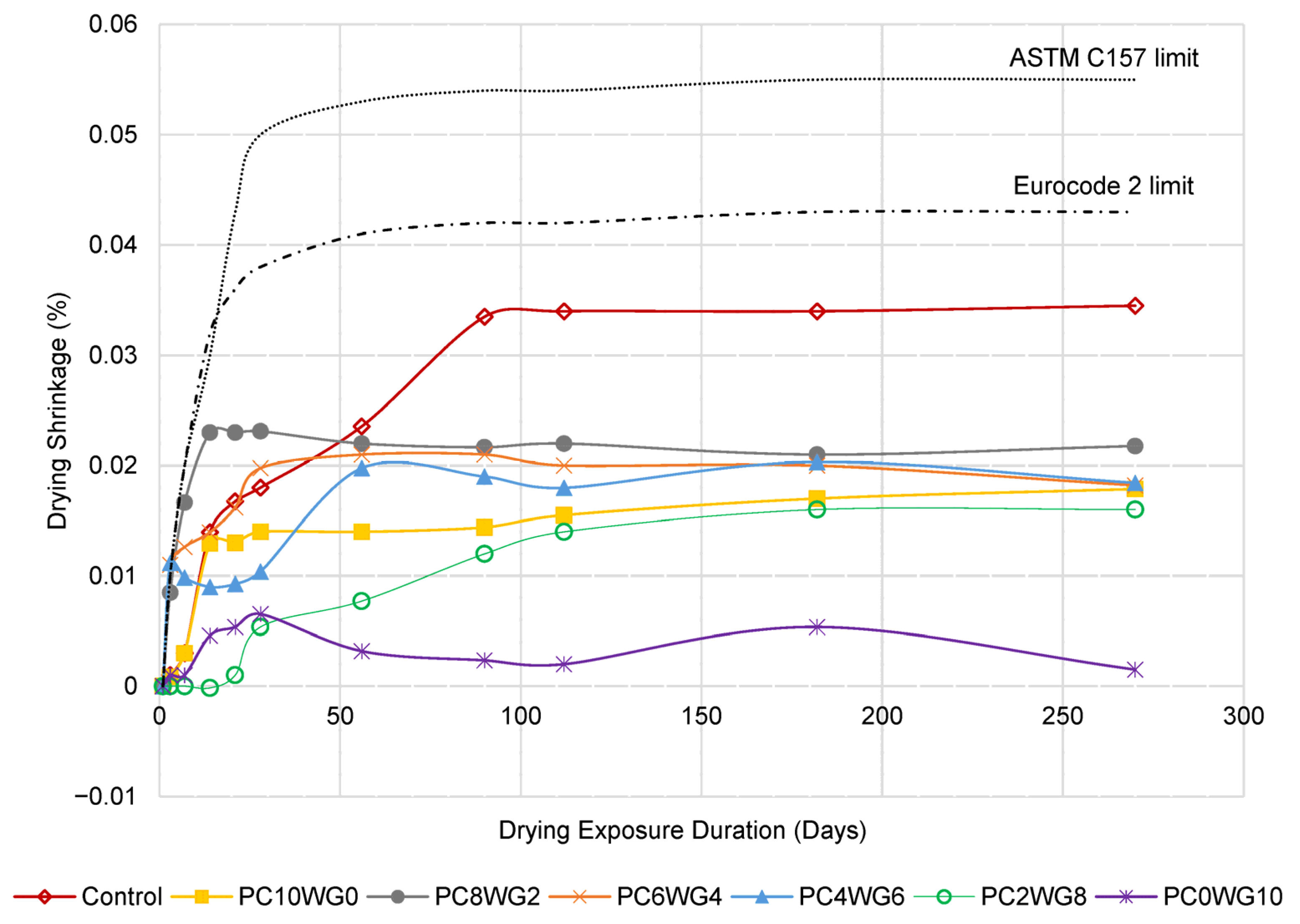

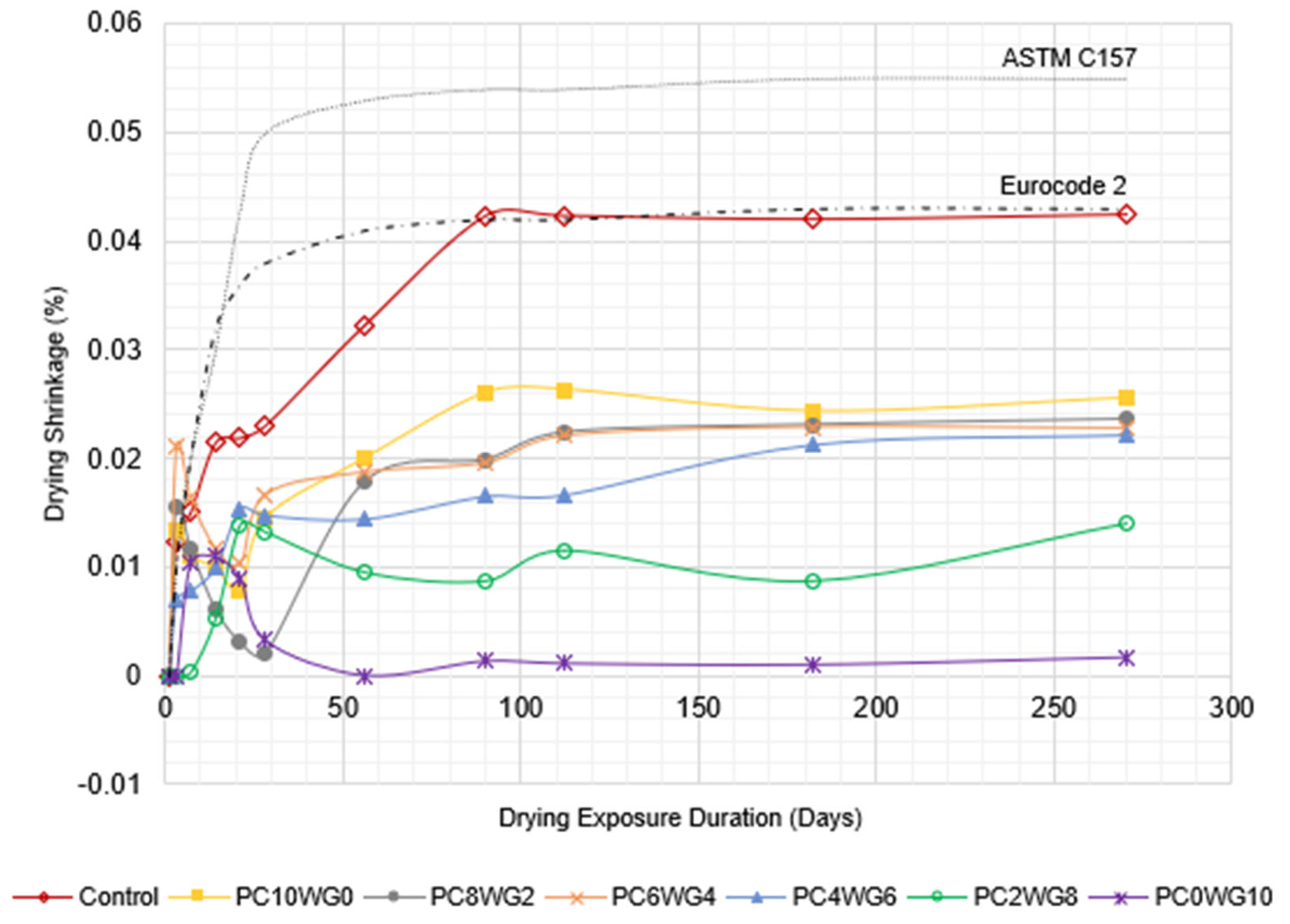

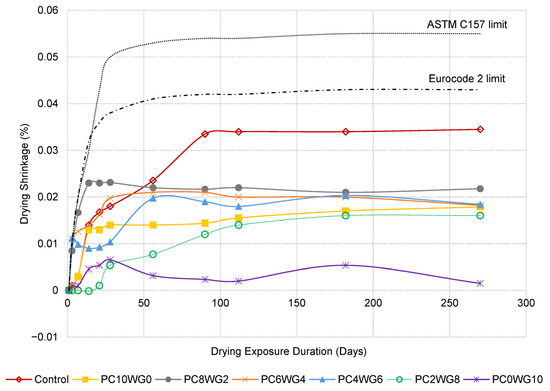

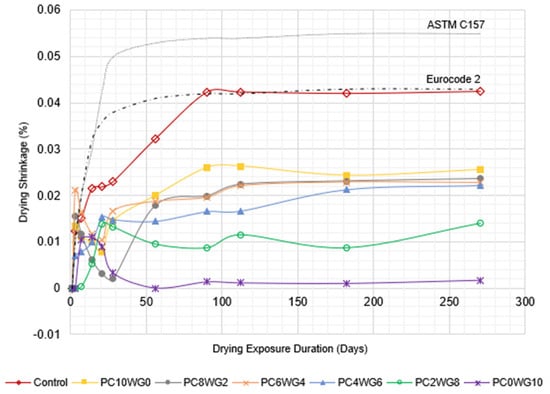

3.5. Drying Shrinkage

The drying shrinkage behaviour of SCC with varying gypsum and OPC contents for series G and E is depicted in a line graph in Figure 10 and Figure 11, respectively. The SCC mixes in both series exhibited the degree of drying shrinkage, which was well below the predefined allowable limits specified in Eurocode 2 [54] for grade 40/50 concrete at 28 days. The only exception was control SCC in series E, which marginally exceeded the predefined limits at the drying durations of 90 days and 112 days. However, the drying shrinkage of the concrete in both series was well below the allowable limits of ASTM C157 [55]. The control SCC for both series exhibited the highest shrinkage value compared to SA SCC specimens from 56 days onwards due to its higher w/b ratio. In addition, GPC0WG10 and GPC0WG10 SCC have the lowest drying shrinkage due to the higher gypsum content, which promotes ettringite formation and compensates for the drying shrinkage [56]. Ettringite formation requires large amounts of both chemically and physically bound water since it contains 32 water molecules, thus reducing the evaporated water during drying. Other SA SCC mix designs contain a small portion of OPC and thus have excess CaO to produce Ca(OH)2 when reacted with free water. However, less water demand was required for reaction with CaO compared to PC0WG10, consequently leaving more shrinkage caused by the loss of free water through evaporation [57]. In comparison, the shrinkage value of SCC in series E is higher than series G. The observation resembled the previous study [58], which concluded that higher aggregate replacement with EAF leads to the drying shrinkage worsening. It was attributed to internal water absorption by aggregates and water loss during drying exposure. As a result, there was a modest increase in shrinkage compared to the mix design with granite coarse aggregate.

Figure 10.

The length change in control and SA SCC for Series G subjected to control drying environment up to 270 days.

Figure 11.

The length change in control and SA SCC for Series E subjected to control drying environment up to 270 days.

3.6. Microstructure of Sulfate-Activated SCC Paste

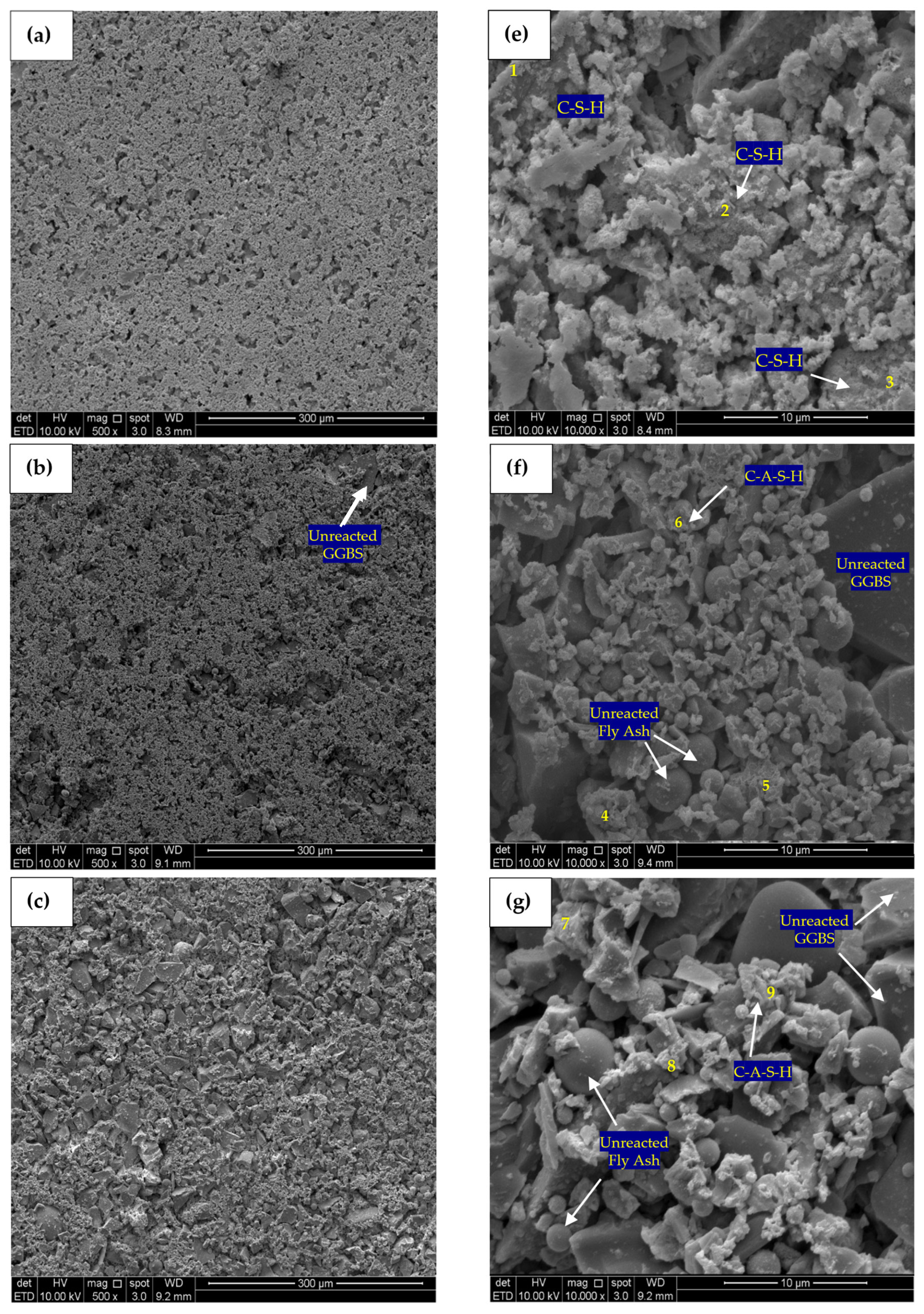

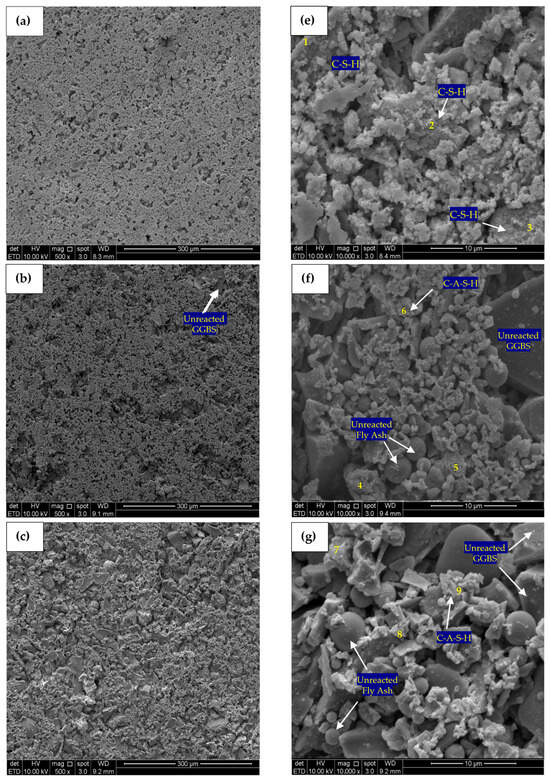

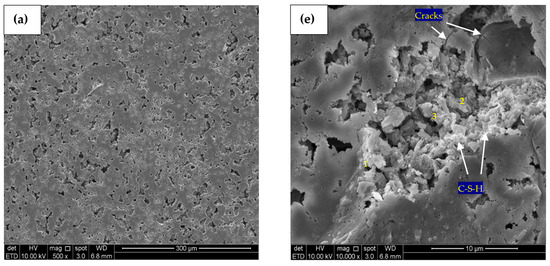

The microstructure analysis of the material was conducted using backscattered electron imaging. SEM micrographs of 500 times magnification for control, PC10WG0, PC4WG6 and PC0WG10 SA paste after 7 days of curing are presented in Figure 12a–d with the corresponding EDX analysis values as tabulated in Table 3. In Figure 12a, the control paste exhibits a porous microstructure with significant water pores. It was largely due to the high w/b ratio of the mix. All SA pastes show reduced water pore volume with many unreacted products’ microstructures, especially PC4WG6, as in Figure 12c. Based on the EDX results, the control paste exhibited the highest Ca/Si ratio of 4.52, followed by PC4WG6, PC0WG10 and PC10WG0 with Ca/Si ratios of 1.56, 1.46 and 1.22, respectively. The ratio for the control paste was considered to be remarkably high for the typical C-S-H phase, which is generally recorded in the range of 1.5 to 2.5 at current curing ages [59]. The SA binders PC10WG0, PC4WG6 and PC0WG10 exhibited a Ca/Al ratio of 3.05, 3.82, and 3.71, respectively. The Ca/Al ratio was high compared to prior literature on the SA binder [60], owing to the presence of FA that contained high amorphous alumina within the binder phase.

Figure 12.

SEM micrograph (500×) and (10,000×) of (a) Control—500×, (b) PC10WG0—500×, (c) PC4WG6—500×, (d) PC0WG10—500×, (e) Control—10,000× (f) PC10WG0—10,000× (g) PC4WG6—10,000×, (h) PC0WG10—10,000× at 7 days.

Table 3.

Atomic ratio of EDX image area at 500 times magnification for the Control, PC10WG0, PC6WG4 and PC0WG10 mixes at 7 days of curing.

Figure 12e–h shows SEM micrographs of the control, PC10WG0, PC4WG6 and PC0WG10 SA pastes after 7 days of curing, with EDX results in Table 4. The micromorphology of the control paste indicated the presence of noticeable capillary pores and non-hydrated cement grains with a size less than 5 μm. PC10WG0 and PC4WG6 exhibited similar morphology with a high quantity of unreacted GGBS and FA particles. However, the sample PC0WG10 exhibited a significantly higher degree of porosity than PC10WG0 and PC4WG6. The porous microstructure was due to the less C-A-S-H gel within the sample and resulted in the poor mechanical strength of PC0WG10, as observed and discussed earlier. The strength development of SA pastes at 7 days was due to the C-A-S-H gels that bonded the FA and GGBS particles to form an interconnected array and was not attributed to the intermixed densified matrix of gypsum that forms ettringite or AFm [15].

Table 4.

Atomic ratio of EDX point at 10,000 times magnification for Control, PC10WG0, PC6WG4 and PC0WG10 mix at 7 days of curing.

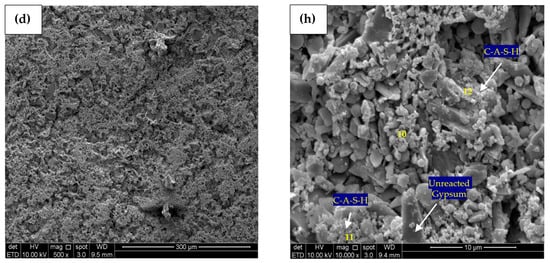

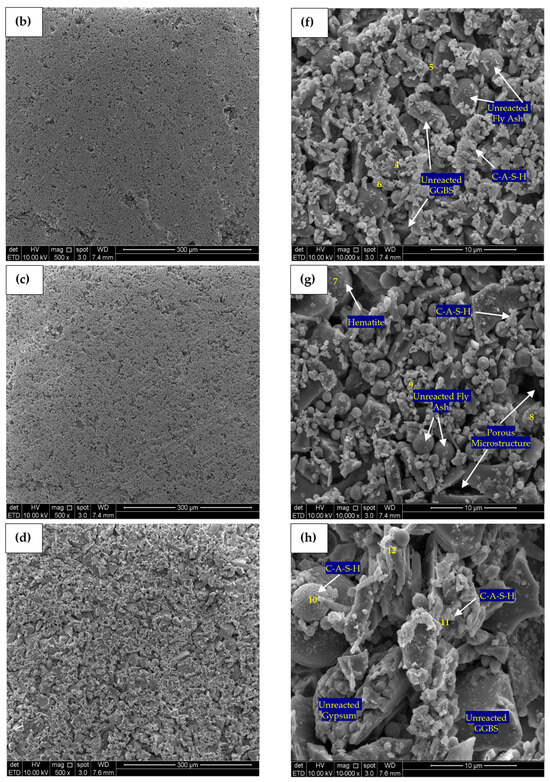

SEM micrographs of 500-times magnification for the control, PC10WG0, PC4WG6 and PC0WG10 SA pastes at 182 days is presented in Figure 13a–d. Based on the EDX analysis results, it was observed that calcium, silicon, and aluminium are the principal elements present within all SA pastes, as tabulated in Table 5. It resulted from the reaction of dissolved calcium, silicate and aluminate ions from the FA and GGBS. For the control paste, the EDX analysis shows a typical hydration product of OPC that yielded C-S-H gels with a Ca/Si ratio of 5.28. PC0WG10 paste area, as in Figure 13d, was observed to have the highest Ca/Si ratio of 1.44 among all SA pastes. Furthermore, it also has the most loosely packed GGBS and FA particles array among all pastes examined. In addition, the Ca/Si ratio for PC10WG0 and PC4WG6 was 1.21 and 1.10, respectively. On the other hand, the Ca/Al ratio recorded for the control paste under the same magnification level was 29.38, which is significantly high due to the meagre amount of amorphous alumina present. Moreover, the Ca/Al ratio from the EDX study for PC10WG0, PC4WG6 and PC0WG10 was recorded as 2.70, 2.50 and 3.36, respectively.

Figure 13.

SEM micrograph (500×) and (10,000×) of (a) Control—500×, (b) PC10WG0—500×, (c) PC4WG6—500×, (d) PC0WG10—500×, (e) Control—10,000× (f) PC10WG0—10,000× (g) PC4WG6—10,000×, (h) PC0WG10—10,000× at 182 days.

Table 5.

Atomic ratio of EDX image area at 500 times magnification for the Control, PC10WG0, PC6WG4 and PC0WG10 mixes at 182 days of curing.

SEM micrographs produced at 10,000 times magnification for the control, PC10WG0, PC4WG6 and PC0WG10 SA pastes after 182 days of curing are presented in Figure 13e–h. For the control paste in Figure 13e, there were few visible cracks observed and EDX point 1, as in Table 6, recorded carbonated area with the presence of CaCO3. Growth in the interconnected C-S-H gel network was also observed. On the other hand, the micromorphology of PC10WG0 in Figure 13f shows the presence of more C-S-H formed within the interstitial spaces of the unreacted FA and GGBS particles. EDX analysis at point 5 shows the existence of the β-larnite (β-Ca2SiO4) phase on PC0WG10 in Figure 13f, which could have formed from the latent hydration of GGBS. Based on the EDX results of point 7 on PC4WG6, as shown in Figure 13g, the crystalline phase of the hematite (Fe2O3) mineral was observed as a trace component. For PC0WG10, the C-A-S-H gel was observed surrounding the FA particles in point 10 as the FA particles act as a nucleation site [61]. Therefore, it could have contributed to the development of the strength of the material after a prolonged curing duration of 182 days.

Table 6.

Atomic ratio of EDX point at 10,000 times magnification for the Control, PC10WG0, PC6WG4 and PC0WG10 mixes at 182 days of curing.

4. Conclusions

Based on the results of the laboratory investigation, the following conclusions of the study can be derived:

- The binder composition containing 72% GGBS, 18% FA, 4% OPC, and 6% gypsum was identified as the optimum formulation. This blend consistently delivered superior mechanical properties across all curing ages, achieving compressive strength above 50 MPa at 270 days and flexural strength up to 20% higher than OPC SCC.

- SA SCC mixes exhibited slump flow within the EFNARC SF2 class, with stable workability and reduced water demand compared to OPC SCC.

- All SA SCC mixes demonstrated drying shrinkage values well below the allowable limits specified in Eurocode 2 and ASTM C157, confirming their volumetric stability. EAF slag aggregates increased density but slightly elevated shrinkage relative to granite mixes.

- Microstructural analysis (SEM–EDX) confirmed that strength development was governed by discrete C-S-H and C-A-S-H gels surrounding unreacted slag and fly ash particles. This produced a rigid particle-packed matrix, rather than a continuous hydration network, accounting for the long-term strength gain.

Overall, sulfate activation using a 4% OPC + 6% gypsum blend provides a viable and safer alternative to highly alkaline activators, while maximising resource recycling. The findings position SASCC as a promising solution for structural and infrastructure applications in aggressive service environments, such as marine and sewer systems. Future work should address long-term field performance and life-cycle environmental assessments to support large-scale implementation. Although the proposed SA-SCC achieved excellent long-term performance and volumetric stability, two key limitations were identified. First, mixes developed relatively low early-age strength, inherent to the slower formation of C-S-H and ettringite phases in low-alkali sulfate systems. However, mixtures containing EAF-slag aggregates exhibited slightly higher drying shrinkage than those with granite, due to the slag’s higher porosity and internal water absorption.

From an engineering perspective, the sulfate-activated SCC developed herein is most suitable for mass-cast elements, precast components with extended curing durations, or non-time-critical structural applications where sustainability and long-term durability take precedence over early strength. The binder system enables SCC with over 94% industrial by-products, reducing OPC dependency and providing a practical low-carbon pathway for the construction sector. Future research should evaluate field performance, durability under aggressive environments, and life-cycle environmental impact to facilitate industrial adoption.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, N.J. and C.B.C.; methodology, N.J. and C.B.C.; validation, N.J. and C.B.C.; formal analysis, N.J., C.B.C., K.H.M. and F.W.A.; investigation, N.J.; resources, C.B.C.; data curation, N.J., K.H.M. and F.W.A.; writing—original draft preparation, N.J.; writing—review and editing, C.B.C., K.H.M. and F.W.A.; visualisation, N.J. and C.B.C.; supervision, C.B.C.; project administration, C.B.C.; funding acquisition, C.B.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Ministry of Higher Education of Malaysia, grant number FRGS/1/2020/TK01/USM/02/3.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the School of Housing, Building and Planning, Universiti Sains Malaysia for supporting this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- International Energy Agency. Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2021; p. 224. [Google Scholar]

- Cheah, C.B.; Samsudin, M.H.; Ramli, M.; Part, W.K.; Tan, L.E. The Use of High Calcium Wood Ash in the Preparation of Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag and Pulverized Fly Ash Geopolymers: A Complete Microstructural and Mechanical Characterization. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 156, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ken, P.W. Geopolymer Mortar Derived from Wood Ash and Fly Ash with Sodium Silicate; School of Housing, Building and Planning, Universiti Sains Malaysia: Penang, Malaysia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Görhan, G.; Kürklü, G. The Influence of the NaOH Solution on the Properties of Fly Ash-Based Geopolymer Mortar Cured at Different Temperatures. Compos. Part B Eng. 2014, 58, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, C.B.; Tan, L.E.; Ramli, M. Recent Advances in Slag-Based Binder and Chemical Activators Derived from Industrial By-Products—A Review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 272, 121942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, S.A.; Provis, J.L.; Fernández-Jiménez, A.; Krivenko, P.V.; Kavalerova, E.; Palacios, M.; Shi, C. Binder Chemistry—High-Calcium Alkali-Activated Materials. In Alkali Activated Materials; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 59–91. [Google Scholar]

- Rashad, A.M. Phosphogypsum as a Construction Material. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 732–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Park, H.; Yum, W.; Suh, J.-I.; Oh, J. Influence of Calcium Sulfate Type on Evolution of Reaction Products and Strength in NaOH- and CaO-Activated Ground Granulated Blast-Furnace Slag. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashad, A.M.; Bai, Y.; Basheer, P.A.M.; Collier, N.C.; Milestone, N.B. Chemical and Mechanical Stability of Sodium Sulfate Activated Slag after Exposure to Elevated Temperature. Cem. Concr. Res. 2012, 42, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, P.T.; Ogawa, Y.; Kawai, K. Effect of Sodium Sulfate Activator on Compressive Strength and Hydration of Fly-Ash Cement Pastes. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2020, 32, 04020119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, F.; Shen, K.; Hu, C.; Wang, F.; Yang, L.; Hu, S. Effect of Sodium Sulfate and C–S–H Seeds on the Reaction of Fly Ash with Different Amorphous Alumina Contents. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 1659–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Q.-F.; Wang, Z.-S.; Gu, L.-Y.; Chen, Y.; Shan, X.-K. Effect of Sodium Sulfate on Strength and Microstructure of Alkali-Activated Fly Ash-Based Geopolymer. J. Cent. South Univ. 2020, 27, 1691–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobasher, N.; Bernal, S.A.; Provis, J.L. Structural Evolution of an Alkali Sulfate Activated Slag Cement. J. Nucl. Mater. 2016, 468, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.; Kim, T. Investigation of the Effects of Magnesium-Sulfate as Slag Activator. Materials 2020, 13, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerra-Cossío, M.A.; González-López, J.R.; Magallanes-Rivera, R.X.; Zaldívar-Cadena, A.A.; Figueroa-Torres, M.Z. Anhydrite, Blast-Furnace Slag and Silica Fume Composites: Properties and Reaction Products. Adv. Cem. Res. 2019, 31, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, C.B.; Nurshafarina, J. Preliminary Study on Influence of Silica Fume on Mechanical Properties of No-Cement Mortars. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 513, 012025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Shui, Z.; Chen, W.; Lu, J.; Tian, S. Properties of Supersulphated Phosphogypsum–Slag Cement (SSC) Concrete. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol.–Mater. Sci. Ed. 2014, 29, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, R.M.; Franke, L.; Deckelmann, G. Phase Changes of Salts in Porous Materials: Crystallization, Hydration and Deliquescence. Constr. Build. Mater. 2008, 22, 1758–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baščarević, Z.; Komljenović, M.; Miladinović, Z.; Nikolić, V.; Marjanović, N.; Petrović, R. Impact of Sodium Sulfate Solution on Mechanical Properties and Structure of Fly Ash-Based Geopolymers. Mater. Struct. 2014, 48, 683–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuruddin, M.F.; Demie, S.; Ahmed, M.F.; Shafiq, N. Effect of Superplasticizer and NaOH Molarity on Workability, Compressive Strength and Microstructure Properties of Self-Compacting Geopolymer Concrete. Int. J. Environ. Chem. Ecol. Geol. Geophys. Eng. 2011, 5, 187–194. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, Y.J.; Shah, N. Enhancement of the Properties of Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag-Based Self-Compacting Geopolymer Concrete by Incorporating Rice Husk Ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 171, 654–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramineni, K.; Boppana, N.K.; Ramineni, M. Performance Studies on Self-Compacting Geopolymer Concrete at Ambient Curing Condition. In Proceedings of the International Congress on Polymers in Concrete, Warsaw, Poland, 16–19 September 2018; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 501–508. [Google Scholar]

- Awoyera, P.O.; Kirgiz, M.S.; Viloria, A.; Ovallos-Gazabon, D. Estimating Strength Properties of Geopolymer Self-Compacting Concrete Using Machine Learning Techniques. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 9016–9028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valizadeh, A.; Aslani, F.; Asif, Z.; Roso, M. Development of Heavyweight Self-Compacting Concrete and Ambient-Cured Heavyweight Geopolymer Concrete Using Magnetite Aggregates. Materials 2019, 12, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj, V.K.; Babu, D.L.V. Assessing the Performance of Molarity and Alkaline Activator Ratio on Engineering Properties of Self-Compacting Alkaline Activated Concrete at Ambient Temperature. J. Build. Eng. 2018, 20, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponikiewski, T.; Gołaszewski, J. The Influence of High-Calcium Fly Ash on the Properties of Fresh and Hardened Self-Compacting Concrete and High-Performance Self-Compacting Concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 72, 212–221. [Google Scholar]

- Khalaf, M.A.; Cheah, C.B.; Ramli, M.; Ahmed, N.M.; Al-Shwaiter, A. Effect of Nano Zinc Oxide and Silica on Mechanical, Fluid Transport and Radiation Attenuation Properties of Steel Furnace Slag Heavyweight Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 274, 121770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameri, F.; Shoaei, P.; Zahedi, M.; Karimzadeh, M.; Musaeei, H.R.; Cheah, C.B. Physico-Mechanical Properties and Micromorphology of AAS Mortars Containing Copper Slag as Fine Aggregate at Elevated Temperature. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 39, 102259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.; Iqbal, S.; Ali, A. Combined Influence of Glass Powder and Granular Steel Slag on Fresh and Mechanical Properties of Self-Compacting Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 178, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasrawi, H. Towards Sustainable Self-Compacting Concrete: Effect of Recycled Slag Coarse Aggregate on the Fresh Properties of SCC. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2018, 2018, 7450943. [Google Scholar]

- Jasme, N.B. Development of Supersulfated Self-Consolidating Concrete Incorporating High-Volume of Industrial By-Products. Ph.D. Thesis, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Gelugor, Malaysia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ACI 211.1-91; Standard Practice for Selecting Proportions for Normal, Heavyweight, and Mass Concrete. American Concrete Institute (ACI): Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2002.

- BS EN 206:2013; Concrete—Specification, Performance, Production and Conformity. British Standards Institution (BSI): London, UK, 2013.

- BS EN 12350-8:2010; Testing Fresh Concrete—Self-Compacting Concrete—Slump-Flow Test. British Standards Institution (BSI): London, UK, 2010.

- BS EN 12390-7:2009; Testing Hardened Concrete—Density of Hardened Concrete. British Standards Institution (BSI): London, UK, 2009.

- BS EN 197-1:2011; Cement—Composition, Specifications and Conformity Criteria for Common Cements. British Standards Institution (BSI): London, UK, 2011.

- BS ISO 1920-8:2009; Testing of Concrete—Determination of the Drying Shrinkage of Concrete. British Standards Institution (BSI): London, UK, 2009.

- Skripkiunas, G.; Dauksys, M.; Stuopys, A.; Levinskas, R. The Influence of Cement Particles Shape and Concentration on the Rheological Properties of Cement Slurry. Mater. Sci. 2005, 11, 150–158. [Google Scholar]

- Halim, N.F.; Mat Yazid, M.R.; Bastam, M.N. Application of Microscopic Techniques for Studying Microstructure of Concrete Containing Lightweight Aggregate. J. Kejuruter. 2018, 1, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, S.M. Construction Calculations Manual; Butterworth-Heinemann: Waltham, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Maslehuddin, M.; Sharif, A.M.; Shameem, M.; Ibrahim, M.; Barry, M.S. Comparison of Properties of Steel Slag and Crushed Limestone Aggregate Concretes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2003, 17, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubeša, I.N.; Barišić, I.; Fucic, A.; Bansode, S.S. Characteristics and Uses of Steel Slag in Building Construction; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cheah, C.B.; Chung, K.Y.; Ramli, M.; Lim, G.K. Engineering Properties and Microstructure Development of Cement Mortar Containing High Volume of Inter-Ground GGBS and PFA Cured at Ambient Temperature. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 122, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwankwo, C.O.; Bamigboye, G.O.; Davies, I.E.E.; Michaels, T.A. High Volume Portland Cement Replacement: A Review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 260, 119696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, C.B.; Tiong, L.L.; Ng, E.P.; Oo, C.W. Engineering Performance of Concrete Containing High Volume of Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag and Pulverized Fly Ash with Polycarboxylate-Based Superplasticizer. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 202, 909–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.-A.; Chang, T.-P.; Shih, J.-Y. Engineering Properties and Bonding Behavior of Self-Compacting Concrete Made with No-Cement Binder. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2018, 30, 04018108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-Y.; Lee, K.-M.; Bang, J.-W.; Kwon, S.-J. Effect of W/C Ratio on Durability and Porosity in Cement Mortar with Constant Cement Amount. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2014, 2014, 273460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engström, F. Mineralogical Influence on Leaching Behaviour of Steelmaking Slags; Luleå University of Technology: Luleå, Sweden, 2010; p. 210. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, T.T. Fluoride Mineralization of Portland Cement: Applications of Double-Resonance NMR Spectroscopy in Structural Investigations of Guest Ions in Cement Phases; Aarhus University: Aarhus, Denmark, 2011; pp. 1–155. [Google Scholar]

- Rondi, L.; Bregoli, G.; Sorlini, S.; Cominoli, L.; Collivignarelli, C.; Plizzari, G. Concrete with EAF Steel Slag as Aggregate: A Comprehensive Technical and Environmental Characterisation. Compos. Part B Eng. 2016, 90, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean-Michel, T.; Farid, B. Mechanical Threshold of Cementitious Materials at Early Age. In Proceedings of the Euro-C Conference on Computational Modelling of Concrete Structures, Mayrhofen, Australia, 27–30 March 2006; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Faleschini, F.; Brunelli, K.; Zanini, M.A.; Dabalà, M.; Pellegrino, C. Electric Arc Furnace Slag as Coarse Recycled Aggregate for Concrete Production. J. Sustain. Metall. 2015, 1, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasrawi, H.; Shalabi, F.; Asi, I. Use of Low CaO Unprocessed Steel Slag in Concrete as Fine Aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2009, 23, 1118–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BS EN 1992-1-1:2004; Eurocode 2: Design of Concrete Structures—General Rules and Rules for Buildings. British Standards Institution (BSI): London, UK, 2004.

- ASTM C157/C157M-17; Standard Test Method for Length Change of Hardened Hydraulic-Cement Mortar and Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- Aly, T.K.; Sanjayan, J.G. Effect of Gypsum on Free and Restrained Shrinkage Behaviour of Slag-Concretes Subjected to Various Curing Conditions. Mater. Struct. 2007, 41, 1393–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hu, L.; Tang, L.; Zhang, E.Q.; Ren, J. Shrinkage Behaviour, Early Hydration and Hardened Properties of Sodium Silicate Activated Slag Incorporated with Gypsum and Cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 248, 118704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, L.; Buoso, A.; Coffetti, D.; Kara, P.; Lorenzi, S. Electric Arc Furnace Granulated Slag for Sustainable Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 123, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, I.G.; Girão, A.V.; Taylor, R.; Jia, S. Hydration of Water- and Alkali-Activated White Portland Cement Pastes and Blends with Low-Calcium Pulverized Fuel Ash. Cem. Concr. Res. 2016, 83, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruskovnjak, A.; Lothenbach, B.; Winnefeld, F.; Figi, R.; Ko, S.-C.; Adler, M.; Mäder, U. Hydration Mechanisms of Super Sulphated Slag Cement. Cem. Concr. Res. 2008, 38, 983–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juenger, M.C.G.; Siddique, R. Recent Advances in Understanding the Role of Supplementary Cementitious Materials in Concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2015, 78, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).