Between Home and Investment: Airbnb Dynamics in the Latin American Heritage City of Valparaíso

Abstract

1. Introduction

Literature Review

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

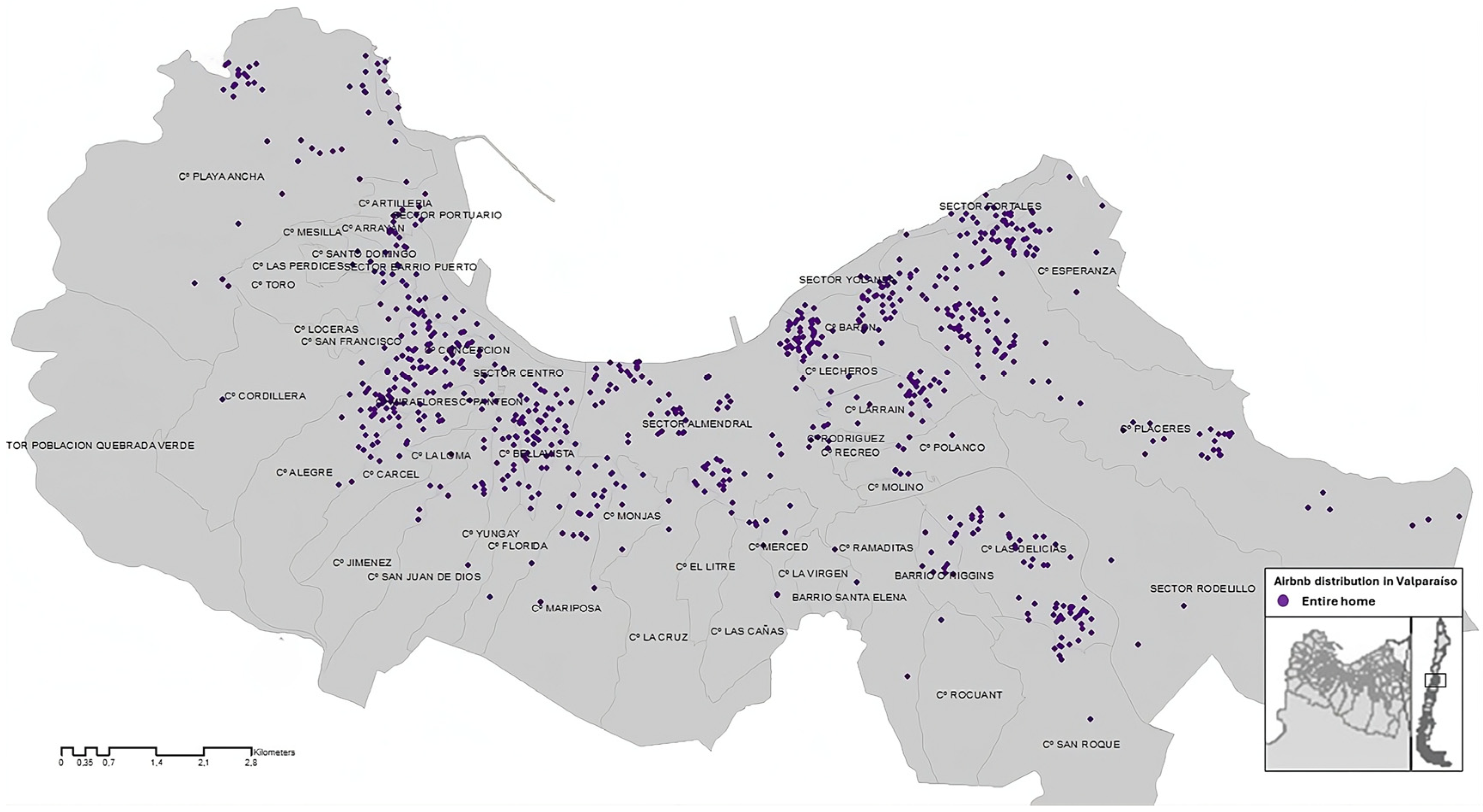

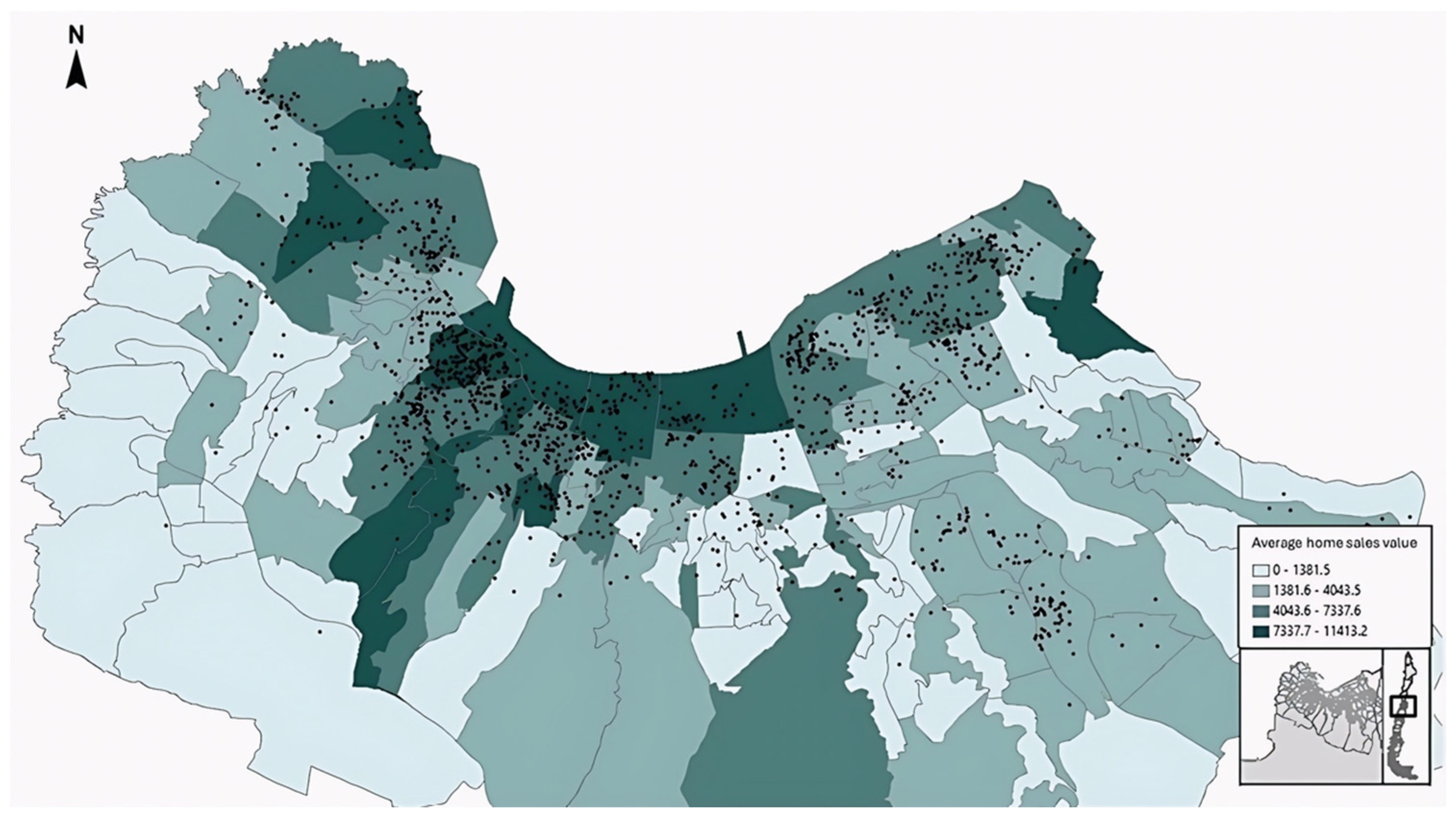

3.1. Spatial Distribution of Airbnb in Valparaíso

3.2. Host Characterization: A Dual Structure of Airbnb Supply in Valparaíso: Private Rooms and Entire Homes in Near Balance

- Landscape and heritage attributes are central drivers of Airbnb concentrations within the city.

- The spatial distribution of listings reveals a marked location bias towards the lower hillsides, areas that also coincide with proximity to essential urban services concentrated in the lower part of Valparaíso.

- In these concentrated areas, short-term rental activity demonstrates significant profitability, with daily revenues that can accumulate rapidly, highlighting the attractiveness of these zones for hosts.

- Host profiles reveal a clear divide: on one side, individual owners renting out entire properties (with minimal evidence of corporate participation); on the other, residents who rent out portions of their own homes. This dichotomy illustrates how socioeconomic disparities shape the platform’s use, separating those able to position housing as a tourism-oriented asset from those who activate it as a source of supplementary income.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barns, S. Negotiating the platform pivot: From participatory digital ecosystems to infrastructures of everyday life. Geogr. Compass 2019, 13, e12464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, G. Economía compartida: Impacto en el mercado inmobiliario de Santiago de Chile. In Proceedings of the 18ª Conferencia Internacional da LARES, São Paulo, Brazil, 26–28 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sadowski, J. Cyberspace and cityscapes: On the emergence of platform urbanism. Urban Geogr. 2020, 41, 448–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderström, O.; Mermet, A. When Airbnb sits in the control room: Platform urbanism as actually existing smart urbanism in Reykjavík. Front. Sustain. Cities 2020, 2, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerena Rongvaux, N.M.; Rodríguez, L.; Saban, L.; Guzmán, F. Los alquileres temporarios como nuevas formas de valorización inmobiliaria: Miradas desde Buenos Aires. Geo UERJ 2024, 7, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FEDETUR Chile. Impacto Arriendo Oferta Informal. Autor. 2019. Available online: https://fedetur.cl/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/20190514-Impacto-oferta-informal.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Fiscalía Nacional Económica. Estudio Sobre el Mercado del Hospedaje; Fiscalía Nacional Económica: Santiago, Chile, 2024.

- Graham, M. Regulate, replicate, and resist—The conjunctural geographies of platform urbanism. Urban Geogr. 2020, 41, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DelPrete, M. Emerging Models in Residential Real Estate or “How to Lose a Billion Dollars in Real Estate Tech”. In Bringing Digitalization Home: How Can Technology Address Housing Challenges? Harvard Joint Center for Housing: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/research-areas/working-papers/emerging-models-residential-real-estate-or-how-lose-billion-dollars (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Link, F.; Marín-Toro, A. (Eds.) Vivienda en Arriendo en América Latina: Desafíos al Ethos de la Propiedad; RIL Editores: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rolnik, R.; Marín-Toro, A.; Jasonson, E. The empire strikes back: The financialization of rental housing—A new frontier of accumulation and precarity. Urban Geogr. 2024, 45, 1707–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerena-Rongvaux, N.; Orozco, H. Alquileres a corto plazo como nuevos patrones de acumulación territorial. Airbnb en Buenos Aires y Santiago de Chile. Scr. Nova Rev. Electrón. Geogr. Cienc. Soc. 2025, 29, 141–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavolari, B. Airbnb and regulatory challenges for home sharing: Notes for a legal research agenda. In Sharing Economies and the Law; Juruá Editora: Curitiba, Brazil, 2017; pp. 259–278. [Google Scholar]

- Saban, L.; Moz, C. The Airbnb phenomenon under scrutiny: Academic studies from Latin America. Thalli. J. Geogr. Res. 2022, 7, 67–90. [Google Scholar]

- Lerena Rongvaux, N.; Rodriguez, L. Airbnb in Latin America: A literature review from an urban studies perspective. J. Urban Aff. 2024, 46, 1146–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres-Seguel, C. Valparaíso y el ciclo urbano pos-Unesco 2003–2022: Turistificación, patrimonio, y configuración de un espacio urbano elitizado. Rev. EURE–Rev. Estud. Urbano Reg. 2024, 50, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Doling, J.; Ronald, R. Home ownership and asset-based welfare. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2010, 25, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schor, J. Debating the sharing economy. J. Self-Gov. Manag. Econ. 2016, 4, 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Slee, T. What’s Yours Is Mine: Against the Sharing Economy; Or Books: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Title 1 | Min Value (USD) | Max Value (USD) | Mean Min (USD) | Median Min (USD) | Mean Max (USD) | Median Max (USD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coastal Short-Term Rental Hub | 12.62 | 164.65 | 14.30 | 10.26 | 174.05 | 135.80 |

| Touristic/Heritage Hub | 8.98 | 442.25 | 9.26 | 8.42 | 456.22 | 368.42 |

| Barrio Puerto and Lower Slopes of Adjacent Hills Hub | 32.14 | 100.33 | 48.16 | 12.63 | 125.11 | 57.89 |

| Hub in Areas Undergoing Vertical Development | 15.42 | 39.78 | 16.23 | 11.16 | 38.96 | 36.84 |

| Hub in Hills Undergoing Emerging Touristification | 11.71 | 125.08 | 13.01 | 10.53 | 118.48 | 76.69 |

| El Almendral–Plan Sector Hub | 13.17 | 147.88 | 15.37 | 11.05 | 120.01 | 63.56 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cáceres-Seguel, C.; Marín-Toro, A. Between Home and Investment: Airbnb Dynamics in the Latin American Heritage City of Valparaíso. Geographies 2025, 5, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies5040065

Cáceres-Seguel C, Marín-Toro A. Between Home and Investment: Airbnb Dynamics in the Latin American Heritage City of Valparaíso. Geographies. 2025; 5(4):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies5040065

Chicago/Turabian StyleCáceres-Seguel, César, and Adriana Marín-Toro. 2025. "Between Home and Investment: Airbnb Dynamics in the Latin American Heritage City of Valparaíso" Geographies 5, no. 4: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies5040065

APA StyleCáceres-Seguel, C., & Marín-Toro, A. (2025). Between Home and Investment: Airbnb Dynamics in the Latin American Heritage City of Valparaíso. Geographies, 5(4), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies5040065