Geotourism: From Theoretical Definition to Practical Analysis in the Sohodol Gorges Protected Area, Romania

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

3. Materials and Methods

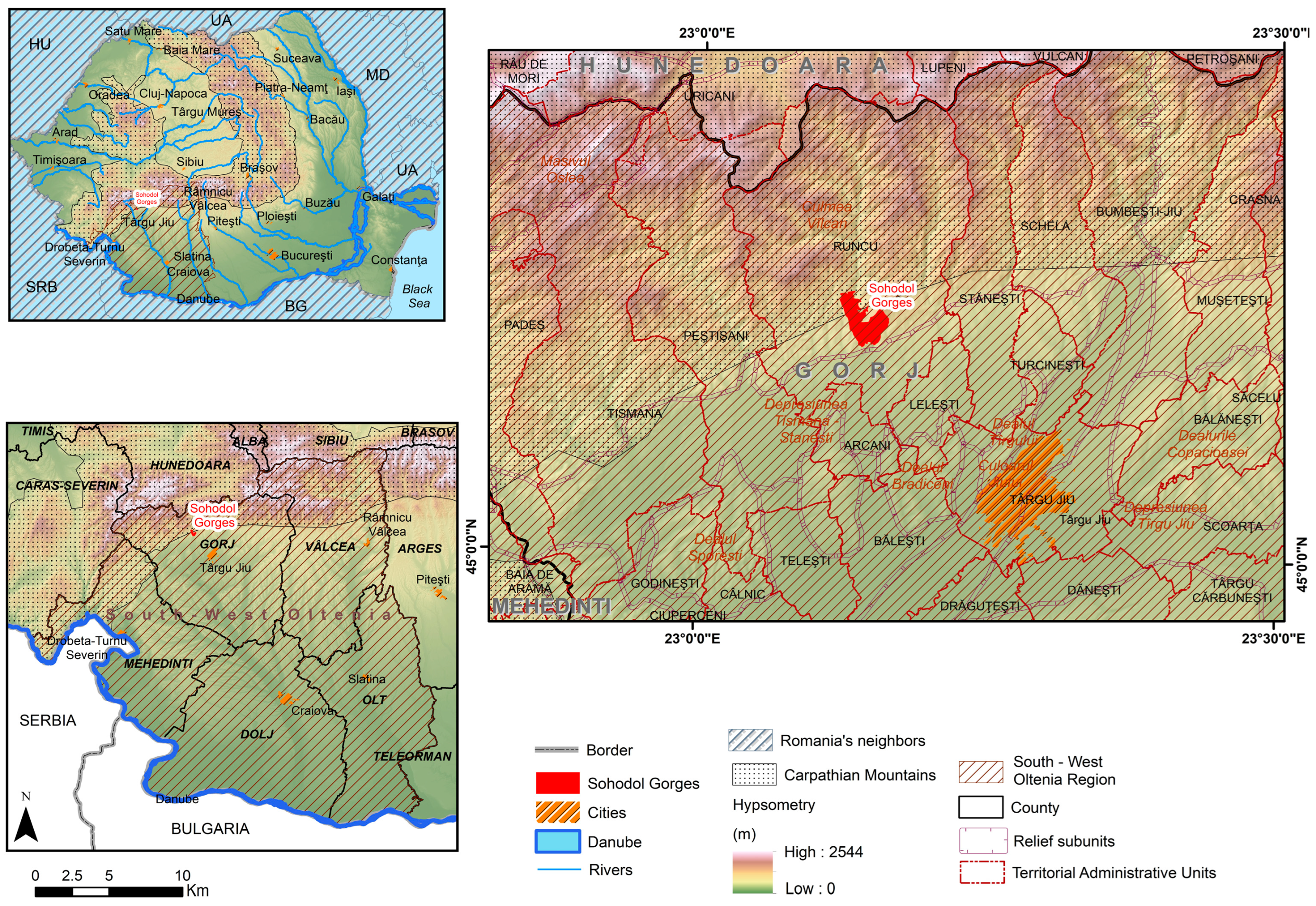

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Data Sources

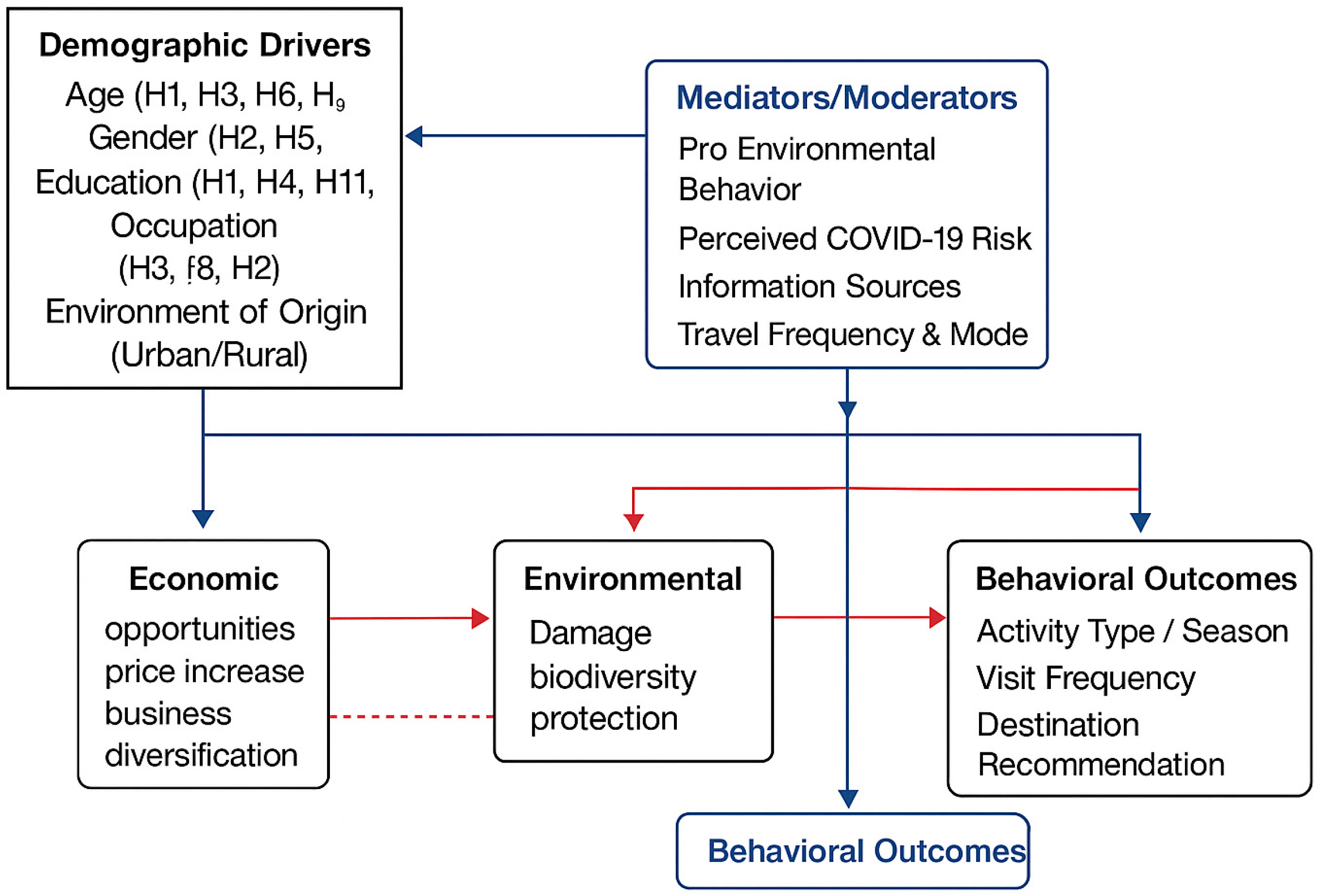

3.3. Analyzing Research Hypotheses

3.4. Variables Used in the Research

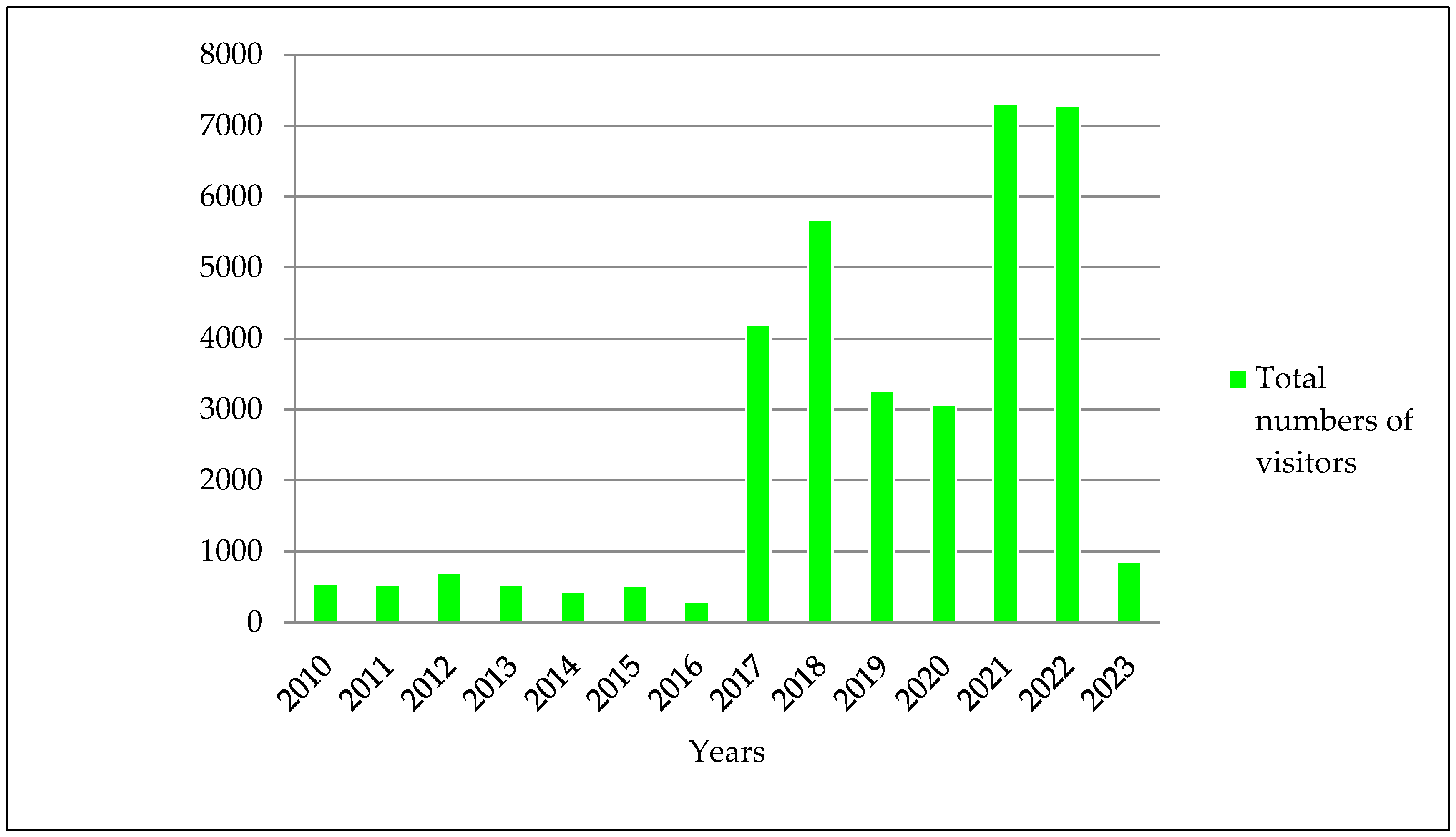

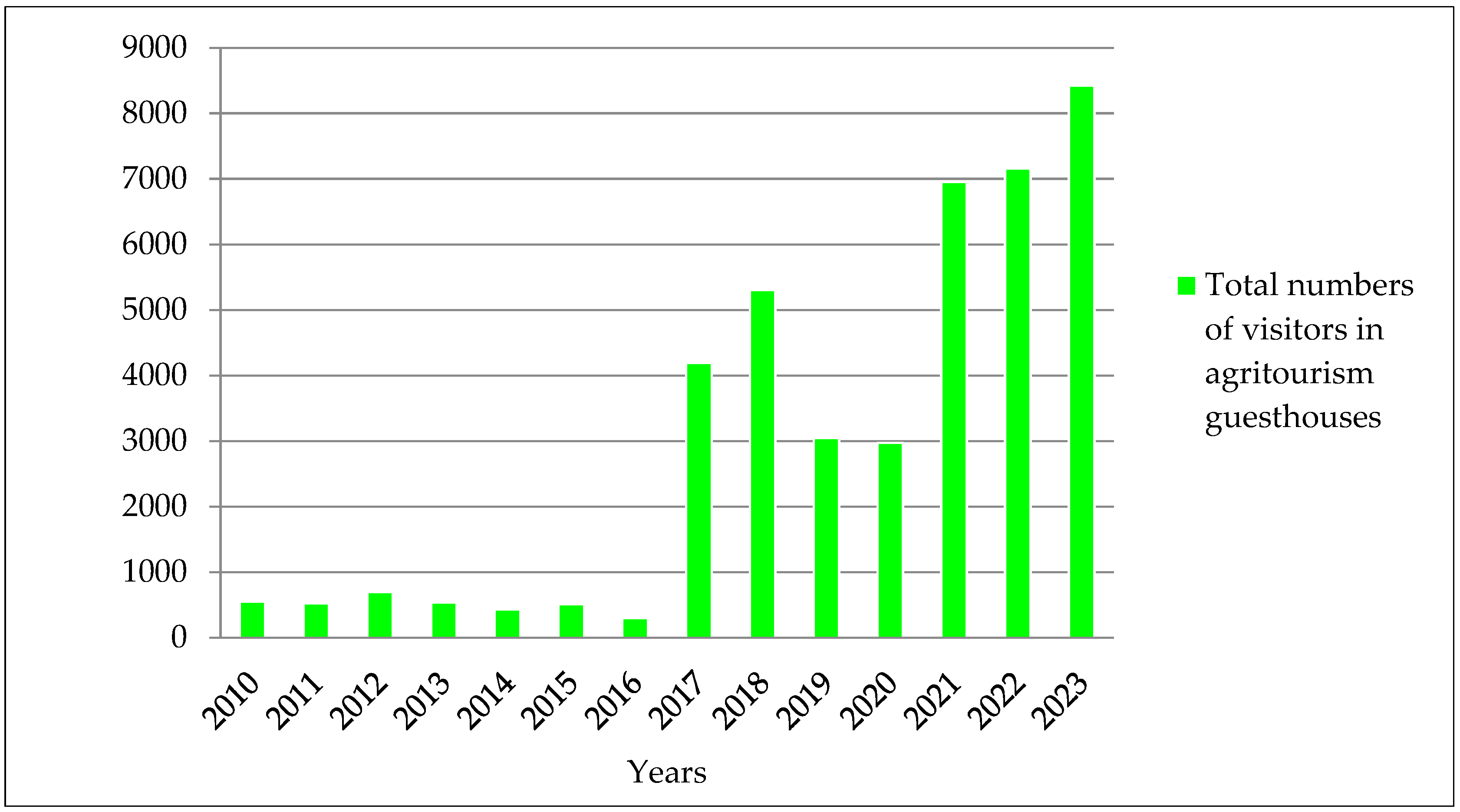

4. Results

4.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics

4.2. Questionnaire Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| UGGps | UNESCO Global Geoparks |

| GIS | Geographic Information System (Software) |

| DMO | Destination Marketing Organization |

| SM | Social media |

| GGN | Global Network of Geoparks |

| EGN | European Geoparks Network |

| IUCN | International Union for Conservation of Nature |

| EViews | Statistical analysis software package |

| NIS | National Institute of Statistics |

| PLS-SEM | Partial least squares structural equation modeling |

| TLS | Terrestrial laser scanner |

| DEM | Digital elevation model |

Appendix A

- I.

- Sample group data.

- Your gender?

- Male

- Female

- Which age category do you fit into?

- 18–30 years

- 31–45 years

- 46–65 years

- Over 65 years

- Your residence?

- Rural

- Urban

- Level of education?

- Secondary school studies

- High school studies

- Post-secondary studies

- Higher education (bachelor’s degree, master’s degree, doctorate)

- Your occupation?

- Student

- Employee

- Unemployed

- Self-employed

- Retiree

- II.

- Evaluation of the aspects related to the development of geotourism post-pandemic.

- 1.

- Economic impacts

| Item. No. | Research Variable | Totally Disagree | Partially Disagree | Neutral | Partially Agree | Totally Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Geotourism increases opportunities in the development of the local economy (employment and investment). | |||||

| 2 | Geotourism stimulates an increase in prices in accommodation units and traditional products. | |||||

| 3 | Geotourism diversifies businesses for locals. |

- 2.

- Impact on the environment

| Item. No. | Research Variable | Totally Disagree | Partially Disagree | Neutral | Partially Agree | Totally Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Geotourism causes damage to the natural environment of ecosystem development and the rural environment. | |||||

| 2 | The natural diversity of the protected area must be exploited and protected to reduce the impact on the environment. | |||||

| 3 | Geotourism must be developed in harmony with the natural and cultural environment of the protected area. |

- 3.

- Socio-cultural impacts

| Item. No. | Research Variable | Totally Disagree | Partially Disagree | Neutral | Partial Agreement | Totally Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | The development of geotourism in Sohodol Gorges increases road traffic congestion. | |||||

| 2 | Geotourism in the Sohodol Gorges causes overcrowding of public and leisure spaces. | |||||

| 3 | The development of geotourism in the Sohodol Gorges would improve the quality of the roads and the agreement spaces. | |||||

| 4 | Geotourism in the Sohodol Gorges has a positive impact on the cultural identity of the local population. | |||||

| 5 | Geotourism intensifies social-cultural interactions between tourists and locals and between hotel managers and tourists. |

- 4.

- Where have you travelled post-COVID-19?

- In Romania

- Outside the country

- 5.

- How often have you travelled to Sohodol Gorges post-COVID-19?

- Only once

- 2–3 times

- More than 3 times

- 6.

- How did you most frequently travel after the COVID-19 pandemic in Sohodol Gorges?

- 7.

- What is the season when you visit the Sohodol Gorges?

- 8.

- What sources of information do you use to document yourself about the Sohodol Gorges?

- 9.

- What geotourism activities have you carried out post-COVID-19 in Sohodol Gorges?

- Nature and wildlife (wilderness camping, bird watching, wildlife watching)

- Adventure (Caving, Climbing)

- Walking and hiking (hiking, nature walk)

- Other

- 10.

- On a scale of 1 to 5, how likely are you to recommend Sohodol Gorges to others?

| Certainly not | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Very likely |

Appendix B. The Results of the Regression Analysis for Hypothesis 1

| Dependent Variable: IMPACT_ECONOMIC_OPPORTUNIES | ||||

| Method: Least Squares | ||||

| Date: 27 September 2024 | ||||

| Time: 18:15 | ||||

| Sample: 1400 | ||||

| Included observations: 400 | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Error Standard | t-Statistic | Probability (Prob.) |

| C | 1.172782 | 0.362161 | 3.23829 | 0.0013 |

| AGE_CATEGORY | −0.115688 | 0.080973 | −1.42873 | 0.1539 |

| STUDY_LEVEL | 0.568877 | 0.095113 | 5.98103 | 0.0000 |

| BUSINESS_ECONOMIC_IMPACT | 0.228818 | 0.044190 | 5.17807 | 0.0000 |

| R-squared | 0.153663 | Mean dependent var | 3.850000 | |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.147251 | S.D. dependent var | 1.462137 | |

| S.E. of regression | 1.350202 | Akaike info criterion | 3.448335 | |

| Sum squared resid | 721.9256 | Schwarz criterion | 3.488249 | |

| Log-likelihood | −685.6669 | Hannan–Quinn criterion | 3.464141 | |

| F-statistic | 23.96620 | Durbin–Watson stat | 1.667800 | |

| Prob (F-statistic) | 0.000000 | |||

Appendix C. The Results of the Regression Analysis for Hypothesis 2

| Dependent Variable: IMPACT_ECONOMIC_INCREASE_PRICES | ||||

| Method: Least Squares | ||||

| Date: 27 September 2024 | ||||

| Time: 18:23 | ||||

| Sample: 1400 | ||||

| Included observations: 400 | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Error Standard | t-Statistic | Probability |

| C | 4.127483 | 0.254953 | 16.18916 | 0.0000 |

| SEX | −0.737659 | 0.384837 | −1.916808 | 0.0560 |

| ENVIRONMENT_PROVENIENCE | 0.151587 | 0.151206 | 1.002521 | 0.3167 |

| SEX*ENVIRONMENT_ORIGIN | 0.29441 | 0.227758 | 1.292642 | 0.1969 |

| R-squared | 0.032613 | Mean dependent var | 4.2575 | |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.025284 | S.D. dependent var | 1.113235 | |

| S.E. of regression | 1.099071 | Akaike info criterion | 3.036758 | |

| Sum squared resid | 478.3512 | Schwarz criterion | 3.076672 | |

| Log-likelihood | −603.3516 | Hannan–Quinn criterion | 3.052564 | |

| F-statistic | 4.450009 | Durbin–Watson stat | 1.537746 | |

| Prob (F-statistic) | 0.00433 | |||

Appendix D. The Results of the Regression Analysis for Hypothesis 3

| Dependent Variable: IMPACT_ENVIRONMENT_DAMAGE | ||||

| Method: Least Squares | ||||

| Date: 27 September 2024 | ||||

| Time: 18:47 | ||||

| Sample: 1400 | ||||

| Included observations: 400 | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Error Standard | t-Statistic | Probability |

| C | 2.797111 | 0.199719 | 14.00525 | 0.0000 |

| AGE_CATEGORY | −0.047056 | 0.079297 | −0.593412 | 0.5532 |

| OCCUPATION | 0.091445 | 0.057501 | 1.590315 | 0.1126 |

| IMPACT_ENVIRONMENT_HARMONY | 0.314804 | 0.038487 | 8.179547 | 0.0000 |

| R-squared | 0.162231 | Mean dependent var | 4.3375 | |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.155884 | S.D. dependent var | 0.990478 | |

| S.E. of regression | 0.910009 | Akaike info criterion | 2.659226 | |

| Sum squared resid | 327.9343 | Schwarz criterion | 2.699104 | |

| Log-likelihood | −527.8452 | Hannan–Quinn criterion | 2.675032 | |

| F-statistic | 25.56129 | Durbin–Watson stat | 1.630223 | |

| Prob (F-statistic) | 0.000000 | |||

Appendix E. The Results of the Regression Analysis for Hypothesis 4

| Dependent Variable: IMPACT_ENVIRONMENT_PROTECT_DIVERSITY | ||||

| Method: Least Squares | ||||

| Date: 27 September 2024 | ||||

| Time: 19:02 | ||||

| Sample: 1400 | ||||

| Included observations: 400 | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Error Standard | t-Statistic | Probability |

| C | 2.175053 | 0.28059 | 7.751705 | 0.0000 |

| ENVIRONMENT_PROVENIENCE | 0.100527 | 0.108541 | 0.92616 | 0.3549 |

| EDUCATION_LEVEL | 0.534794 | 0.069907 | 7.650077 | 0.0000 |

| R-squared | 0.14236 | Mean dependent var | 4.295 | |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.13804 | S.D. dependent var | 1.107267 | |

| S.E. of regression | 1.028007 | Akaike info criterion | 2.900592 | |

| Sum squared resid | 419.5488 | Schwarz criterion | 2.930528 | |

| Log-likelihood | −577.1185 | Hannan–Quinn criterion | 2.912447 | |

| F-statistic | 32.94915 | Durbin–Watson stat | 1.626902 | |

| Prob (F-statistic) | 0.00000 | |||

Appendix F. The Results of the Regression Analysis for Hypothesis 5

| Dependent Variable: SOCIO_CULTURAL_TRAFFIC_IMPACT | ||||

| Method: Least Squares | ||||

| Date: 27 September 2024 | ||||

| Time: 19:05 | ||||

| Sample: 1400 | ||||

| Included observations: 400 | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Error Standard | t-Statistic | Probability |

| C | 2.906420 | 0.230304 | 12.61995 | 0.0000 |

| SEX | −0.094251 | 0.090553 | −1.040844 | 0.2986 |

| STUDY_LEVEL | 0.418111 | 0.059604 | 7.014863 | 0.0000 |

| R-squared | 0.116632 | Mean dependent var | 4.395000 | |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.112182 | S.D. dependent var | 0.949330 | |

| S.E. of regression | 0.894498 | Akaike info criterion | 2.622364 | |

| Sum squared resid | 317.6503 | Schwarz criterion | 2.652300 | |

| Log-likelihood | −521.4727 | Hannan–Quinn criterion | 2.634219 | |

| F-statistic | 26.20816 | Durbin–Watson stat | 1.618870 | |

| Prob (F-statistic) | 0.000000 | |||

Appendix G. The Results of the Regression Analysis for Hypothesis 6

| Covariance Analysis: Ordinary | ||||

| Date: 27 September 2024 | ||||

| Time: 19:34 | ||||

| Sample: 1400 | ||||

| Included observations: 400 | ||||

| Covariance | CATEGORY_ AGE | IMPACT_SOCIO _CULTURAL_ INFRASTRUCTURE | IMPACT_SOCIO _OVERAGGREGATION | OCCUPATION |

| Correlation | ||||

| CATEGORY_AGE | 0.775994 | |||

| 1.000000 | ||||

| IMPACT_SOCIO_ CULTURAL_ INFRASTRUCTURE | 0.221056 | 1.320494 | ||

| 0.218376 | 1.000000 | |||

| IMPACT_SOCIO _OVERAGGREGATION | 0.102194 | 0.397756 | 0.858994 | |

| 0.125170 | 0.373468 | 1.000000 | ||

| OCCUPATION | 0.815788 | 0.395412 | 0.132587 | 1.489775 |

| 0.758731 | 0.281917 | 0.117205 | 1.000000 | |

Appendix H. The Results of the Regression Analysis for Hypothesis 7

| Dependent Variable: SOCIO_CULTURAL_IMPACT_CULTURAL_IDENTITY | ||||

| Method: Least Squares | ||||

| Date: 27 September 2024 | ||||

| Time: 22:35 | ||||

| Sample: 1400 | ||||

| Included observations: 400 | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Error Standard | t-Statistic | Probability |

| C | 1.960059 | 0.393704 | 4.978508 | 0.0000 |

| ENVIRONMENT_PROVENIENCE | 0.395232 | 0.152297 | 2.595136 | 0.0098 |

| STUDY_LEVEL | 0.338976 | 0.098088 | 3.455823 | 0.0006 |

| R-squared | 0.056826 | Mean dependent var | 3.840000 | |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.052074 | S.D. dependent var | 1.481515 | |

| S.E. of regression | 1.442425 | Akaike info criterion | 3.578000 | |

| Sum squared resid | 825.9941 | Schwarz criterion | 3.607957 | |

| Log-likelihood | −712.6000 | Hannan–Quinn criterion | 3.589535 | |

| F-statistic | 11.95956 | Durbin–Watson stat | 1.645415 | |

| Prob (F-statistic) | 0.000009 | |||

Appendix I. The Results of the Regression Analysis for Hypothesis 8

| Covariance Analysis: Ordinary | ||

| Date: 27 September 2024 | ||

| Time: 22:40 | ||

| Sample: 1400 | ||

| Included observations: 400 | ||

| Covariance | IMPACT_SOCIO_CULTURAL _INTERACTIONS | OCCUPATION |

| Correlation | ||

| IMPACT_SOCIO_ CULTURAL_INTERACTIONS | 1.192344 | |

| 1.000000 | ||

| OCCUPATION | −0.120437 | 1.489775 |

| −0.090365 | 1.000000 | |

Appendix J. The Results of the Regression Analysis for Hypothesis 9

| Covariance Analysis: Ordinary | |||

| Date: 27 September 2024 | |||

| Time: 22:44 | |||

| Sample: 1400 | |||

| Included observations: 400 | |||

| Covariance | AGE_CATEGORY | FREQUENCY_ SOHODOL_ GORGES | TRAVEL_MODE |

| Correlation | |||

| AGE_CATEGORY | 0.775994 | ||

| 1.000000 | |||

| FREQUENCY_ SOHODOL_GORGES | 0.191600 | 0.494400 | |

| 0.309334 | 1.000000 | ||

| TRAVEL_MODE | 0.015906 | 0.055500 | 0.893594 |

| 0.019102 | 0.083499 | 1.000000 |

Appendix K. The Results of the Regression Analysis for Hypothesis 10

| Dependent Variable: POST_PANDEMIC_DESTINATIONS | ||||

| Method: Least Squares | ||||

| Date: 27 September 2024 | ||||

| Time: 22:46 | ||||

| Sample: 1400 | ||||

| Included observations: 400 | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Error Standard | t-Statistic | Probability |

| C | 1.093413 | 0.039309 | 27.81605 | 0.0000 |

| SEX | 0.018869 | 0.021504 | 0.877426 | 0.3808 |

| INFORMATION_SOURCES | −0.010934 | 0.00755 | −1.44819 | 0.1484 |

| R-squared | 0.006668 | Mean dependent var | 1.047500 | |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.001663 | S.D. dependent var | 0.212972 | |

| S.E. of regression | 0.212795 | Akaike info criterion | −0.249504 | |

| Sum squared resid | 17.97683 | Schwarz criterion | −0.219568 | |

| Log-likelihood | 52.90073 | Hannan–Quinn criterion | −0.237649 | |

| F-statistic | 1.332411 | Durbin–Watson stat | 1.103095 | |

| Prob (F-statistic) | 0.265018 | |||

Appendix L. The Results of the Regression Analysis for Hypothesis 11

| Dependent Variable: GEOTOURISTIC_ACTIVITIES | ||||

| Method: Least Squares | ||||

| Date: 27 September 2024 | ||||

| Time: 22:48 | ||||

| Sample: 1400 | ||||

| Included observations: 400 | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Error Standard | t-Statistic | Probability |

| C | 2.139280 | 0.294078 | 7.274542 | 0.0000 |

| SEASON | 0.231376 | 0.082983 | 2.788254 | 0.0056 |

| STUDY_LEVEL | 0.081910 | 0.064853 | 1.263018 | 0.2073 |

| R-squared | 0.024020 | Mean dependent var | 2.940000 | |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.019103 | S.D. dependent var | 0.986831 | |

| S.E. of regression | 0.977359 | Akaike info criterion | 2.799547 | |

| Sum squared resid | 379.2268 | Schwarz criterion | 2.829483 | |

| Log-likelihood | −556.9094 | Hannan–Quinn criterion | 2.811402 | |

| F-statistic | 4.885293 | Durbin–Watson stat | 1.540314 | |

| Prob (F-statistic) | 0.008017 | |||

Appendix M. The Results of the Regression Analysis for Hypothesis 12

| Dependent Variable: RECOMMEND_DESTINATION | ||||

| Method: Least Squares | ||||

| Date: 27 September 2024 | ||||

| Time: 22:52 | ||||

| Sample: 1400 | ||||

| Included observations: 400 | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Error Standard | t-Statistic | Probability |

| C | 4.129074 | 0.178917 | 23.07815 | 0.0000 |

| OCCUPATION | 0.075608 | 0.032228 | 2.346054 | 0.0195 |

| TRAVEL_MODE | 0.006353 | 0.041612 | 0.152674 | 0.8787 |

| R-squared | 0.013693 | Mean dependent var | 4.4125 | |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.008725 | S.D. dependent var | 0.789876 | |

| S.E. of regression | 0.786422 | Akaike info criterion | 2.364826 | |

| Sum squared resid | 245.5287 | Schwarz criterion | 2.394762 | |

| Log-likelihood | −469.9653 | Hannan–Quinn criterion | 2.376681 | |

| F-statistic | 2.755881 | Durbin–Watson stat | 1.665161 | |

| Prob (F-statistic) | 0.064769 | |||

References

- Guo, Y.; Jiang, J.; Li, S. A sustainable tourism policy research review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, G.V.; Grama, V.; Sonko, S.M.; Boc, E.; Băican, D.; Garai, L.D.; Blaga, L.; Josan, I.; Caciora, T.; Gruia, K.A.; et al. Online information premise in the development of Bihor tourist destination, Romania. Folia Geogr. 2020, 62, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Aluculesei, A.-C.; Nistoreanu, P.; Avram, D.; Nistoreanu, B.G. Past and Future Trends in Medical Spas: A Co-Word Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, G.V.; Banto, N.; Herman, L.M.; Ungureanu, M.; Kostilníková, K.; Josan, I. Perception, reality and intent in Bihorean tourism, Romania. Folia Geogr. 2022, 64, 86–103. [Google Scholar]

- Petrişor, A.-I.; Hamma, W.; Nguyen, H.D.; Randazzo, G.; Muzirafuti, A.; Stan, M.-I.; Tran, V.T.; Aştefănoaiei, R.; Bui, Q.-T.; Vintilă, D.-F.; et al. Degradation of Coastlines under the Pressure of Urbanization and Tourism: Evidence on the Change of Land Systems from Europe, Asia and Africa. Land 2020, 9, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schvab, A.; Văidianu, N.; Sîrodoev, I.; Ratkajec, H.; Skolka, M.; Tudor, M.; Cracu, G.; Paraschiv, M.; Sava, D.; Florea-Saghin, I.; et al. Tourism impact models as sustainable development planning tools for local and regional authorities. J. Urban Reg. Anal. 2022, 14, 211–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, R.; Newsome, D. Geotourism: Definition, characteristics and international perspectives. In Handbook of Geotourism; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2018; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjanović, M.; Tomić, N.; Antić, A.; Tomić, T. Travel Behaviour Insights among Geotourists in Serbia—Case Study of Zaječar District. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Hernández, Y.M.; Ríos-Reyes, C.A.; Villarreal-Jaimes, C.A. Geotourism and Geoeducation: A Holistic Approach for Socioeconomic Development in Rural Areas of Los Santos Municipality, Santander, Colombia. Geoheritage 2024, 16, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornecká, E.; Molokáč, M.; Gregorová, B.; Čech, V.; Hronček, P.; Javorská, M. Structure of Sustainable Management of Geoparks through Multi-Criteria Methods. Sustainability 2024, 16, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, R.K. Global geotourism–An emerging form of sustainable tourism. Czech J. Tour. 2013, 2, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tometzová, D.; Jesenský, M.; Molokáč, M.; Kornecká, E. Nostalgic Geotourism as a New Form of Landscape Presentation: An Application to the Carphatian Mountains. Land 2024, 13, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeever, P.J.; Zouros, N.C.; Patzak, M. The UNESCO global network of national geoparks. In Geotourism; Newsome, D., Dowling, R.K., Eds.; The Tourism of Geology and Landscape; Good Fellow Publishers Limited: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 221–230. [Google Scholar]

- Henriques, M.H.; Brilha, J. UNESCO Global Geoparks: A strategy towards global understanding and sustainability. Episodes 2017, 40, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsani, N.T.; Coelho, C.O.A.; Costa, C.M.M.; Amrikazemi, A. Geo-knowledge management and geoconservation via geoparks and geotourism. Geoheritage 2014, 6, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molokáč, M.; Babicová, Z.; Pachinger, P.; Kornecká, E. Evaluation of geosites from the perspective of geopark management: The example of proposed Zemplín Geopark. Geoheritage 2023, 15, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molokáč, M.; Alexandrová, G.; Kobylanska, M.; Hlavňová, B.; Hronček, P.; Tometzová, D. Virtual Mine—Educational model for Wider Society. In Proceedings of the 2017 15th International Conference on Emerging eLearning Technologies and Applications (ICETA), Košice, Slovenia, 26–27 October 2017; pp. 307–312, ISBN 978-1-5386-3294-9. [Google Scholar]

- Molokáč, M.; Tometzová, D.; Alexandrová, G.; Kobylanska, M.; Babicová, Z. Virtual Mine–Successful story of education in raw materials. In Proceedings of the 2019 17th International Conference on Emerging eLearning Technologies and Applications: Information and Communication Technologies in Learning (ICETA), Starý Smokovec, Slovakia, 21–22 November 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 536–539, ISBN 978-1-7281-4967-7. [Google Scholar]

- Newsome, D.; Dowling, R. Geoheritage and geoturism. In Geoheritage; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morante-Carballo, F.; Gurumendi-Noriega, M.; Cumbe-Vásquez, J.; Bravo-Montero, L.; Carrión-Mero, P. Georesources as an alternative for sustainable development in COVID-19 times—A study case in Ecuador. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome, D.; Dowling, R.K. (Eds.) Geotourism: The Tourism of Geology and Landscape; Goodfellow Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Telbisz, T.; Gruber, P.; Mari, L.; Kőszegi, M.; Bottlik, Z.; Standovár, T. Geological heritage, geotourism and local development in Aggtelek National Park (NE Hungary). Geoheritage 2020, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjanović, M.; Tomić, N.; Radivojević, A.R.; Marković, S.B. Assessing the geotourism potential of the Niš city area (Southeast Serbia). Geoheritage 2021, 13, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomić, N.; Antić, A.; Tešić, D.; Đorđević, T.; Momčilović, O. Canyoning and geotourism: Assessing geosites for canyoning activities in Western Serbia. Turizam 2021, 25, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumanapala, D.; Wolf, I.D. Introducing Geotourism to Diversify the Visitor Experience in Protected Areas and Reduce Impacts on Overused Attractions. Land 2022, 11, 2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brđanin, E.; Milanović, M.; Malinović-Milićević, S.; Tomić, N.; Vujović, F.; Ćulafić, G. Geosite assessment as the first step for the development of canyoning activities in North Montenegro. Open Geosci. 2024, 16, 20220698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ólafsdóttir, R.; Tverijonaite, E. Geotourism: A systematic literature review. Geosciences 2018, 8, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antić, A.; Vujičić, M.D.; Dragović, N.; Cimbaljević, M.; Stankov, U.; Tomić, N. Show cave visitors: An analytical scale for visitor motivation and travel constraints. Geoheritage 2022, 14, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Wu, W. Geoparks and geotourism in China: A sustainable approach to geoheritage conservation and local development—A review. Land 2022, 11, 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selem, K.M.; Khalid, R.; Tan, C.C.; Sinha, R.; Raza, M. Geotourism destination development: Scale development and validation. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2024, 46, 100763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsan, S.; Begum, R.A.; Leman, M.S. Competitive advantage of geotourism market in Malaysia: A comparison among ASEAN Economies. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 219, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miśkiewicz, K. Geotourism Product as an Indicator for Sustainable Development in Poland. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdowsi, S.; Tavana, M.; Heydari, R.; Štrba, Ľ. Geoeducation: The key to geoheritage conservation in tourism destinations. Int. Geol. Rev. 2025, 67, 1674–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehata, A.E.; Khan, M.A.; Khalid, R.; Raza, M.; Selem, K.M. Consequences of paradoxical leadership in the hotel setting: Moderating role of work environment. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2023, 32, 670–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batabyal, D.; Halam, H.; Sen, S.K.; Chakma, M.K.; Sinha, R.; Selem, K.M. Circuit development approach to geotourism and geoparks in Northeast India. GeoJournal 2023, 88, 6161–6173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R.; Batabyal, D.; Bagchi, G.; Selem, K.M. Establishing the nexus between library and tourism: An empirical approach. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2023, 26, 1006–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, V.C.; Sharma, V.R. Geotourism in Kachchh, Gujarat: Unveiling Benefits and Empowering Local Communities. In Sustainable Strategies for Managing Geoheritage in a Dynamic World; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R. Managing Tourism—A Missing Element Gestión turística asignatura pendiente. PASOS Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2022, 20, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmi, E.; Che Rose, R.A.; Awang, A.; Abas, A. Innovative and Competitive: A Systematic Literature Review on New Tourism Destinations and Products for Tourism Supply. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanović, M.; Lukić, T.; Milentijević, N.; Bojović, V.; Valjarević, A. Assessment of geosites as a basis for geotourism development: A case study of the Toplica District, Serbia. Open Geosci. 2023, 15, 20220589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glossary: Tourist-Statistics Explained—Eurostat. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Glossary:Tourist (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Smith, M.A.; Kingston, S. Demographic, attitudinal, and social factors that predict pro-environmental behavior. Sustain. Clim. Change 2021, 14, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Aquino, R.S.; Hall, C.M.; Chen, N.; Fieger, P. Is Gen Z really that different? Environmental attitudes, travel behaviours and sustainability practices of international tourists to Canterbury, New Zealand. J. Sustain. Tour. 2025, 33, 1016–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giachino, C.; Pattanaro, G.; Bertoldi, B.; Bollani, L.; Bonadonna, A. Nature-based solutions and their potential to attract the young generations. Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargisson, R.J.; De Groot, J.I.; Steg, L. The relationship between sociodemographics and environmental values across seven European countries. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robina-Ramírez, R.; Martín-Lucas, M.; Dias, A.; Castellano-Álvarez, F.J. What role geoparks play improving the health and well-being of senior tourists? Heliyon 2023, 9, e22295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Lin, Y.; Cheng, X.; Ahn, Y.-j.; Chi, X. An Investigation into the Formation of Tourists’ Pro-Environmental Behavior in Geotourism: Balancing Tourism and Ecosystem Preservation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Huang, L.; Whitmarsh, L. Home and Away: Cross-Contextual Consistency in Tourists’ Pro-Environmental Behavior. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1443–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfandiar, K.; Dowling, R.; Pearce, J.; Goh, E. What a Load of Rubbish! The Efficacy of Theory of Planned Behaviour and Norm Activation Model in Predicting Visitors’ Binning Behaviour in National Parks. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 46, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-F.; Wu, J.-C.; Deng, S. The Effect of Destination Social Responsibility on Tourists’ Pro-Environmental Behavior. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 27, 1233–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J.; Huang, L.M.; He, M.; Ye, B.H. Understanding Pro-Environmental Behavior in Tourism: Developing an Experimental Model. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 57, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Chi, X.; Han, H. A Complexity Theory in Geotourism: Traveler Environmentally Sustainable Behaviors in Global Geoparks. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2024, 41, 1021–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, C.; Lu, S.; Zhu, Y. Research on Popular Science Tourism Based on SWOT-AHP Model: A Case Study of Koktokay World Geopark in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Pang, X.; Zhou, C.; He, X. Coupling Coordination Degree between the Socioeconomic and Eco-Environmental Benefits of Koktokay Global Geopark in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudla, M.; Javorská, M.; Vašková, J.; Čech, V.; Tometzová, D. Inventory and evaluation of geosites: Case studies of the Slovak Karst as a potential geopark in Slovakia. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, B. Sustainability assessment of geotourism consumption based on energy–water–waste–economic nexus: Evidence from Zhangye Danxia National Geopark. Land 2024, 13, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesada-Román, A.; Torres-Bernhard, L.; Ruiz-Álvarez, M.A.; Rodríguez-Maradiaga, M.; Velázquez-Espinoza, G.; Espinosa-Vega, C.; Rodríguez-Bolaños, H. Geodiversity, geoconservation, and geotourism in Central America. Land 2021, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubalíková, L.; Bajer, A.; Balková, M.; Kirchner, K.; Machar, I. Geodiversity action plans as a tool for developing sustainable tourism and environmental education. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.A.; Ritchie, B.W. A farming crisis or a tourism disaster? An analysis of the foot and mouth disease in the UK. Curr. Issues Tour. 2003, 6, 150–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rittichainuwat, B.N.; Chakraborty, G. Perceived travel risks regarding terrorism and disease: The case of Thailand. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosselló, J.; Santana-Gallego, M.; Awan, W. Infectious disease risk and international tourism demand. Health Policy Plan. 2017, 32, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, C.-S. Developing a Conceptual Model for the Post-COVID-19 Pandemic Changing Tourism Risk Perception. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazilu, M.; Niță, A.; Băbăț, A.; Drăguleasa, I.A.; Grigore, M. Risk and Sustainable tourism resilience in the Post Economic Crisis and COVID-19 pandemic period. Present Environ. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 18, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichel, A.; Fuchs, G.; Uriely, N. Perceived risk and the non-institutionalized tourist role: The case of Israeli student ex-backpackers. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karl, M.; Reintinger, C.; Schmude, J. Reject or select: Mapping destination choice. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 54, 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.D. Responding to global infectious disease outbreaks: Lessons from SARS on the role of risk perception, communication and management. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 63, 3113–3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M.; Crotts, J.C.; Law, R. The impact of the perception of risk on international travellers. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2007, 9, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perpiña, L.; Prats, L.; Camprubí, R. Image and risk perception: An integrated approach. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maturkanič, P.; Čergeťová, I.T.; Králik, R.; Hlad, Ľ.; Roubalová, M.; Martin, J.G.; Judák, V.; Akimjak, A.; Petrikovičová, L. The Phenomenon of Social and Pastoral Service in Eastern Slovakia and Northwestern Czech Republic during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Comparison of Two Selected Units of Former Czechoslovakia in the Context of the Perspective of Positive Solutions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pröbstl-Haider, U.; Gugerell, K.; Maruthaveeran, S. COVID-19 and outdoor recreation–lessons learned? Introduction to the special issue on “outdoor recreation and COVID-19: Its effects on people, parks and landscapes”. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2023, 41, 100583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferhati, K.; Chouguiat Belmallem, S.; Burlea-Schiopoiu, A. The Role of the COVID-19 Crisis in Shaping Urban Planning for Improved Public Health: A Triangulated Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doiciar, C.; Cretan, R. Pandemic populism: COVID-19 and the rise of the nationalist AUR party in Romania. Geogr. Pannonica 2021, 25, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrache, L.; Stănculescu, E.; Nae, M.; Dumbrăveanu, D.; Simion, G.; Taloș, A.M.; Mareci, A. Post-Lockdown Effects on Students’ Mental Health in Romania: Perceived Stress, Missing Daily Social Interactions, and Boredom Proneness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemteanu, M.-S.; Dabija, D.-C. The Influence of Internal Marketing and Job Satisfaction on Task Performance and Counterproductive Work Behavior in an Emerging Market during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popescu, L.; Vîlcea, C. General population perceptions of risk in the COVID-19 pandemic: A Romanian case study. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2021, 29, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vătămănescu, E.M.; Dabija, D.C.; Gazzola, P.; Cegarro-Navarro, J.G.; Buzzi, T. Before and after the outbreak of COVID-19: Linking fashion companies’ corporate social responsibility approach to consumers’ demand for sustainable products. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 321, 128945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemțeanu, S.-M.; Dabija, D.-C.; Gazzola, P.; Vătămănescu, E.-M. Social Reporting Impact on Non-Profit Stakeholder Satisfaction and Trust during the COVID-19 Pandemic in an Emerging Market. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pripoaie, R.; Cretu, C.-M.; Turtureanu, A.-G.; Sirbu, C.-G.; Marinescu, E.Ş.; Talaghir, L.-G.; Chițu, F.; Robu, D.M. A Statistical Analysis of the Migration Process: A Case Study—Romania. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinerean, S.; Budac, C.; Baltador, L.A.; Dabija, D.-C. Assessing the Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on M-Commerce Adoption: An Adapted UTAUT2 Approach. Electronics 2022, 11, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cehan, A.; Iațu, C. Government policies for tourism in Romania during the COVID-19 pandemic: A stakeholders’ perspective. East. J. Eur. Stud. 2023, 14, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemțeanu, M.-S.; Dabija, D.-C. Negative Impact of Telework, Job Insecurity, and Work–Life Conflict on Employee Behaviour. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Ren, L.; Jia, G. Compensatory travel in the post COVID-19 pandemic era: How does boredom stimulate intentions? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 54, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comănescu, L.; Nedelea, A. The assessment of geodiversity–a premise for declaring the geopark Buzăului County (Romania). J. Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 121, 1493–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Necheş, I.M.; Erdeli, G. Geolandscapes and geotourism: Integrating nature and culture in the Bucegi Mountains of Romania. Landsc. Res. 2015, 40, 486–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovreiu, A.B.; Bărsoianu, I.A.; Comănescu, L.; Nedelea, A. Capitalizing of the geotourism potential and its impact on relief. Case study: Cozia massif, Romania. Geo J. Tour. Geosites 2019, 24, 212–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comănescu, L.; Nedelea, A. Geoheritage and geodiversity education in Romania: Formal and non-formal analysis based on questionnaires. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milu, V. Preliminary Assessment of the Geological and Mining Heritage of the Golden Quadrilateral (Metaliferi Mountains, Romania) as a Potential Geotourism Destination. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma, C.; Seghedi, A.; Popa, R.G. Salt is the Seed of Life: A Geotourism Potential Analysis of Salt Areas in Buzău Land, Romania. Geoheritage 2022, 14, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, G.C.; Grecu, F. Analysis of the Scientific Importance and Vulnerability of the Sarea lui Buzău Geosite Within the Buzău Land UNESCO Global Geopark, Romania. Geoheritage 2023, 15, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desculțu Grigore, M.-I.; Niță, A.; Drăguleasa, I.-A.; Mazilu, M. Geotourism, a New Perspective of Post-COVID-19-Pandemic Relaunch through Travel Agencies—Case Study: Bucegi Natural Park, Romania. Sustainability 2024, 16, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niță, A.; Drăguleasa, I.-A. Perception and development of rural tourism in Vâlcea county. Ann. Univ. Craiova. Ser. Geogr. 2022, 23, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drăguleasa, I.-A.; Niță, A.; Mazilu, M. Capitalization of Tourist Resources in the Post-COVID-19 Period—Developing the Chorematic Method for Oltenia Tourist Destination, Romania. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drăguleasa, I.-A.; Popescu, A.A.; Constantinescu, E.; Mazilu, M. Rural Tourism-Realistic Solution for Sustainable Socio-Economic Development: Case Study of Vâlcea County, Oltenia Region. Manag. Mark. J. 2024, 22, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Călina, A.; Călina, J.; Stan, I. Research regarding the sustainable development of agritourism in the neighbouring area of Cozia national park, Romania. AgroLife Sci. J. 2017, 6, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Călina, J.; Călina, A.; Iancu, T.; Vangu, G.M. Research on the Use of Aerial Scanning and Gis in the Design of Sustainable Agricultural Production Extension Works in an Agritourist Farm in Romania. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Călina, J.; Călina, A. Study on the development and evolution of the sustainable agritourism activity at a boarding house in Crasna Municipality—Gorj, Romania. Sci. Pap. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2024, 24, 249–258. [Google Scholar]

- Drăguleasa, I.-A.; Niță, A.; Mazilu, M.; Constantinescu, E. Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage in Vâlcea County, South-West Oltenia Region: Motivations, Belief and Tourists’ Perceptions. Religions 2024, 15, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drăguleasa, I.A.; Bănuț, M.M.; Vasile, M.D. Turismul verde regional–un concept de conservare a zonei Oltenești. In Proceedings of the Conferința Instruire Prin Cercetare Pentru O Societate Prosper 10, Chişinău, Moldova, 18–19 March 2023; pp. 66–71. Available online: https://ibn.idsi.md/vizualizare_articol/179344 (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Călugăru, I.V.; Giugea, N.; Mărăcineanu, L. Oenotourism-a new form of manifestation of tourism in Oltenia. Ann. Univ. Craiova Ser. Biol. Hortic. Food Prod. Process. Technol. Environ. Eng. 2016, 21, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Vlăduț, A.Ș.; Licurici, M.; Burada, C.D. Viticulture in Oltenia region (Romania) in the new climatic context. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2023, 154, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragan, A.; Crețan, R.; Terian, M.I. Landscapes of Watermills: A Rural Cultural Heritage Perspective in an East-Central European Context. Heritage 2024, 7, 4790–4813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragan, A.; Crețan, R.; Lungu, M.A. Neglected and peripheral spaces: Challenges of Socioeconomic Marginalization in a south Carpathian area. Land 2024, 13, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nistoreanu, P.; Dorobanţu, M.R.; Ţuclea, C.E. The trilateral relationship ecotourism–sustainable tourism–slow travel among nature in the line with authentic tourism lovers. Rev. Tur.-Stud. Cercet. Tur. 2011, 11, 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Tănase, M.O.; Dina, R.; Isac, F.-L.; Rusu, S.; Nistoreanu, P.; Mirea, C.N. Romanian Wine Tourism—A Paved Road or a Footpath in Rural Tourism? Sustainability 2022, 14, 4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tănase, M.O.; Nistoreanu, P.; Dina, R.; Georgescu, B.; Nicula, V.; Mirea, C.N. Generation Z Romanian Students’ Relation with Rural Tourism—An Exploratory Study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nistoreanu, P.; Aluculesei, A.-C.; Dumitrescu, G.-C. A Bibliometric Study of the Importance of Tourism in Salt Landscapes for the Sustainable Development of Rural Areas. Land 2024, 13, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragan, A.; Creţan, R.; Jucu, I.S.; Oancea, O.A. Rural Landscapes as Cultural Heritage and Identity along a Romanian River. Heritage 2024, 7, 4354–4373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovič, F.; Maturkanič, P. Urban-Rural Dichotomy of Quality of Life. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agenția Națională pentru Protecția Mediului. Available online: http://apmgj.anpm.ro/ (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- National Institute of Statistics, TEMPO. Available online: http://statistici.insse.ro:8077/tempo-online/#/pages/tables/insse-table (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Monografia turistică a Comunei Runcu, Județul Gorj. Available online: https://runcugorj.ro/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Monografie-turistica-Runcu.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Ferguson, M.D.; McIntosh, K.; English, D.B.K.; Ferguson, L.A.; Barcelona, R.; Giles, G.; Fraser, O.; Leberman, M. The outdoor renaissance: Assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic upon outdoor recreation visitation, behaviors, and decision-making in New England’s national forests. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2022, 35, 1063–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, M.D.; Lynch, M.L.; Evensen, D.; Ferguson, L.A.; Barcelona, R.; Giles, G.; Leberman, M. The nature of the pandemic: Exploring the negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic upon recreation visitor behaviors and experiences in parks and protected areas. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2023, 41, 100498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Templeton, A.J.; Goonan, K.; Fyall, A. COVID-19 and its impact on visitation and management at US national parks. Int. Hosp. Rev. 2021, 35, 240–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, S.; Eykelbosh, A. COVID-19 and outdoor safety: Considerations for use of outdoor recreational spaces. Natl. Collab. Cent. Environ. Health 2020, 829, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Chavarria, M.E.; Gutiérrez, A.; Saladié, Ò. Managing visitor flows in protected areas in a context of changing mobilities: An analysis of challenges, responses, and learned lessons during the pandemic in Tarragona Province (Spain). Int. J. Geoherit. Parks 2024, 12, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Călina, J.; Călina, A. Analysis of the indicators characterizing the activity of rural tourism and agritourism in vâlcea county from the perspective of the total quality. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2021, 21, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Simeanu, C.; Andronachi, V.-C.; Usturoi, A.; Davidescu, M.A.; Mintaș, O.-S.; Hoha, G.-V.; Simeanu, D. Rural Tourism: A Factor of Sustainable Development for the Traditional Rural Area of Bucovina, Romania. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turtureanu, A.-G.; Crețu, C.-M.; Pripoaie, R.; Marinescu, E.Ș.; Sîrbu, C.-G.; Talaghir, L.-G. Sustainable Development Through Agritourism and Rural Tourism: Research Trends and Future Perspectives in the Pandemic and Post-Pandemic Period. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Deng, F. How to Influence Rural Tourism Intention by Risk Knowledge during COVID-19 Containment in China: Mediating Role of Risk Perception and Attitude. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adom, D.; Alimov, A.; Gouthami, V. Agritourism as a preferred travelling trend in boosting rural economies in the post-COVID-19 period: Nexus between agriculture, tourism, art and culture. J. Migr. Cult. Soc. 2021, 1, 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bacter, R.V.; Gherdan, A.E.M.; Dodu, M.A.; Ciolac, R.; Iancu, T.; Pîrvulescu, L.; Brata, A.M.; Ungureanu, A.; Bolohan, R.M.; Chebeleu, I.C. The Influence of Legislative and Economic Conditions on Romanian Agritourism: SWOT Study of Northwestern and Northeastern Regions and Sustainable Development Strategies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harisiad, E.; Brînzan, N.; Mocioi, I.; Adam, I.; Bădescu, N.; Băleanu, C.; Brînzan, N.; Ciobanu, I.; Ciobanu, R.; Corlan, I.; et al. Gorj; Monografie, Editura Sport—Turism: Bucharest, Romania, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Amaro, S.; Chaves, N.B.; Henriques, C.; Barroco, C. Motivation-based segmentation of visitors to a UNESCO Global Geopark. Geoheritage 2023, 15, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation coefficients: Appropriate use and interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics: And Sex and Drugs and Rock “N” Roll, 4th ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA; London, UK; New Delhi, India, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 7th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2019; Available online: https://www.pearson.com/en-us/subject-catalog/p/using-multivariate-statistics/P200000003097/9780137526543 (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Wooldridge, J.M. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach, 7th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.cengage.uk/c/introductory-econometrics-a-modern-approach-7e-wooldridge/9781337558860/ (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991; Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1991-97932-000 (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Ryan, C.; Glendon, I. Tourism Management. Butterworth-Heinemann. 1998. Available online: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=1901609 (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Pearce, P.L. The Ulysses Factor: Evaluating Visitors in Tourist Settings; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1988; Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-1-4612-3924-6 (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Cohen, E. Towards a sociology of international tourism. Soc. Res. 1972, 39, 164–189. [Google Scholar]

- Mattila, A.S. The role of culture and purchase motivation in service encounter evaluations. J. Serv. Mark. 1999, 13, 376–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D.; Mertig, A.G.; Jones, R.E. Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: A revised NEP scale. J. Soc. Issues 2008, 56, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R. Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1977; Available online: http://www.harryganzeboom.nl/Teaching/SocPart/Readings/Inglehart%20-%201997%20-%20Chapter%201.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- McKercher, B.; du Cros, H. Cultural Tourism: The Partnership Between Tourism and Cultural Heritage Management; Haworth Hospitality Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2002; Available online: https://bit.ly/46E5Qyy (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Pearce, P.L. Perceived changes in holiday destinations. Ann. Tour. Res. 1982, 9, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crețan, R.; Light, D.; Richards, S.; Dunca, A.M. Encountering the victims of Romanian communism: Young people and empathy in a memorial museum. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2018, 59, 632–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, D.; Creţan, R.; Dunca, A.M. Education and post-communist transitional justice: Negotiating the communist past in a memorial museum. Southeast Eur. Black Sea Stud. 2019, 19, 565–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, D.; Creţan, R.; Dunca, A.-M. Museums and Transitional Justice: Assessing the Impact of a Memorial Museum on Young People in Post-Communist Romania. Societies 2021, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niță, A.; Drăguleasa, I.-A. Empirical Investigation of the Motivation and Perceptions of Tourists Visiting Spa Resorts in the Vâlcea Subcarpathians, Romania. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Sun, T.; Lu, Y. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Tourists’ Risk Perceptions: Tourism Policies’ Mediating Role in Sustainable and Resilient Recovery in the New Normal. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caciora, T.; Herman, G.V.; Ilieș, A.; Baias, Ș.; Ilieș, D.C.; Josan, I.; Hodor, N. The Use of Virtual Reality to Promote Sustainable Tourism: A Case Study of Wooden Churches Historical Monuments from Romania. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhati, A.S.; Mohammadi, Z.; Agarwal, M.; Kamble, Z.; Donough-Tan, G. Motivating or manipulating: The influence of health protective behaviour and media engagement on post-COVID-19 travel. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 2088–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.B.; Soliman, M. COVID-19 and repeat visitation: Assessing the role of destination social responsibility, destination reputation, holidaymakers’ trust and fear arousal. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 19, 100495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassoulas, C.; Nikolakakis, E.; Staridas, S. Digital Tools to Serve Geotourism and Sustainable Development at Psiloritis UNESCO Global Geopark in COVID Times and Beyond. Geosciences 2022, 12, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoblea, F.; Delannoy, J.-J.; Jaillet, S.; Ployon, E.; Sadier, B. Digital Tools for Managing and Promoting Karst Geosites in Southeast France. Geoheritage 2014, 6, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grama, V.; Ilies, G.; Safarov, B.; Ilies, A.; Caciora, T.; Hodor, N.; Ilies, D.C.; Kieti, D.; Berdenov, Z.; Josan, I.; et al. Digital Technologies Role in the Preservation of Jewish Cultural Heritage: Case Study Heyman House, Oradea, Romania. Buildings 2022, 12, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharovskyi, V.; Németh, K. Scale Influence on Qualitative–Quantitative Geodiversity Assessments for the Geosite Recognition of Western Samoa. Geographies 2022, 2, 476–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharovskyi, V.; Németh, K. Qualitative-Quantitative Assessment of Geodiversity of Western Samoa (SW Pacific) to Identify Places of Interest for Further Geoconservation, Geoeducation, and Geotourism Development. Geographies 2021, 1, 362–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayla, N. An Overview of New Technologies Applied to the Management of Geoheritage. Geoheritage 2014, 6, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharovskyi, V.; Németh, K. Recognition of Potential Geosites Utilizing a Hydrological Model within Qualitative–Quantitative Assessment of Geodiversity in the Manawatu River Catchment, New Zealand. Geographies 2023, 3, 178–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharovskyi, V.; Németh, K. Geomorphological Model Comparison for Geosites, Utilizing Qualitative–Quantitative Assessment of Geodiversity, Coromandel Peninsula, New Zealand. Geographies 2022, 2, 609–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiago, F.; Correia, P.; Briciu, V.-A.; Borges-Tiago, T. Geotourism Destinations Online Branding Co-Creation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkáčová, H.; Pavlíková, M.; Jenisová, Z.; Maturkanič, P.; Králik, R. Social Media and Students’ Wellbeing: An Empirical Analysis during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number | Variables |

|---|---|

| H1 | Age_category Study_level Economic_impact_opportunities Business_economic_impact |

| H2 | Sex Economic_impact_price_increase Provenance_environment |

| H3 | Age_category Occupation Environmental_impact_damage Impact_environment_harmony |

| H4 | Provenance_environment Study_level Impact_environment_protection_diversity |

| H5 | Sex Study_level Impact_socio_cultural_traffic |

| H6 | Occupation Age_category Impact_socio_cultural_infrastructure Impact_socio_overcrowding |

| H7 | Socio_cultural_impact_cultural_identity Provenance_environment Study_level |

| H8 | Sex Occupation Impact_socio_cultural_interactions |

| H9 | Age_category Travel_mode Sohodol_Gorges_frequency |

| H10 | Sex Information_sources Post_pandemic_destinations |

| H11 | Season Education_level Geotourism_activities |

| H12 | Occupation Travel_mode Destination_recommendation |

| Hypothesis | Statistical Method Used |

|---|---|

| H1. Younger and more educated tourists are more likely to perceive geotourism as generating positive economic opportunities and promoting local business diversification in the Sohodol Gorges. | Multiple regression analysis |

| H2. Female tourists and those from rural areas are more likely to perceive geotourism as increasing prices for accommodation and traditional local products. | Multiple regression analysis |

| H3. Younger tourists and those working in environmental or tourism-related fields are more likely to perceive geotourism as harmful to the natural environment and emphasize the need for sustainable development. | Multiple regression analysis |

| H4. Urban tourists and those with higher levels of education are more likely to support biodiversity protection in geotourism development within protected areas. | Multiple regression analysis |

| H5. Female tourists and those with higher levels of education are more likely to perceive road traffic congestion caused by geotourism as negatively impacting the quality of the tourist experience. | Multiple regression analysis |

| H6. Older tourists are more likely to perceive overcrowding in public spaces and inadequate infrastructure as negative impacts of geotourism compared to younger tourists, who are more tolerant of these issues. | Pearson correlation coefficient |

| H7. Urban tourists and those with higher education are more likely to perceive geotourism as positively contributing to the preservation and promotion of local cultural identity. | Multiple regression analysis |

| H8. Tourists working in professions that involve frequent social interaction are more likely to perceive geotourism as intensifying meaningful socio-cultural interactions with locals. | Pearson correlation coefficient |

| H9. Older tourists are slightly more likely to visit the Sohodol Gorges more frequently, while younger tourists tend to prefer more independent modes of travel in the post-pandemic context. | Pearson correlation coefficient |

| H10. Female tourists are more likely to choose safe, well-documented post-pandemic destinations using official online sources, while male tourists prefer adventurous destinations and rely more on informal sources. | Multiple correlation coefficient |

| H11. Tourists with higher levels of education are more likely to engage in educational geotourism activities in spring and autumn, while less educated tourists prefer recreational or adventure activities in summer. | Multiple correlation coefficient |

| H12. Tourists in liberal or creative professions and those traveling with family or in organized groups are more likely to recommend the Sohodol Gorges compared to solo travelers or those from technical fields. | Multiple correlation coefficient |

| Ref. No. | Question | Variable |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Your gender? | Sex |

| 2. | What age group do you fall into? | Age_category |

| 3. | Where are you from? | Medium_provenance |

| 4. | Level of completed studies? | Study_level |

| 5. | Your occupation? | Occupation |

| Economic impacts | ||

| 6. | Economic impacts [geotourism increases opportunities in the development of the local economy (employment and investment)] | Economic_impact_opportunities |

| 7. | Economic impacts [geotourism stimulates an increase in prices in accommodation units and traditional products] | Economic_impact_price_increase |

| 8. | Economic impacts [geotourism diversifies businesses for locals] | Business_economic_impact |

| Impacts on the environment | ||

| 9. | Environmental impacts [geotourism causes damage to the natural environment of ecosystem development and rural environment] | Environmental_impact_damage |

| 10. | Environmental impacts [the natural diversity of the protected area must be exploited and protected to reduce environmental impacts] | Impact_environment_protection_diversity |

| 11. | Impacts on the environment [geotourism must be developed in harmony with the natural and cultural environments of the protected area] | Impact_environment_harmony |

| Socio-cultural impacts | ||

| 12. | Socio-cultural impacts [the development of geotourism in the Sohodol Gorges increases road traffic congestion] | Impact_socio_cultural_traffic |

| 13. | Socio-cultural impacts [geotourism in Sohodol Gorges causes overcrowding of public and leisure spaces] | Impact_socio_supraaglomerarr |

| 14. | Socio-cultural impacts [the development of geotourism in the Sohodol Gorges would improve the quality of roads and recreational spaces] | Impact_socio_cultural_infrastructure |

| 15. | Socio-cultural impacts [geotourism in the Sohodol Gorges has a positive impact on the cultural identity of the local population] | Impact_socio_cultural_identity_cultural |

| 16. | Socio-cultural impacts [geotourism intensifies socio-cultural interactions between tourists and locals and between hotel managers and tourists] | Impact_socio_cultural_interactions |

| 17. | Where have you traveled post-COVID-19 pandemic? | Post_pandemic_destinations |

| 18. | How often have you traveled to Sohodol Gorges post-COVID-19 pandemic? | Frequency_Sohodol_Gorges |

| 19. | How did you most commonly travel in the Sohodol Gorges following the COVID-19 pandemic? | Travel_mode |

| 20. | What is the season to visit the Sohodol Gorges? | Season |

| 21. | What sources of information do you use to document yourself about the Sohodol Gorges? | Information_sources |

| 22. | What geotourism activities have you carried out post-COVID-19 pandemic in Sohodol Gorges? | Geotourism_activities |

| 23. | On a scale of 1 to 5, how likely are you to recommend Sohodol Gorges to others? | Recommend_destination |

| Characteristics | Categories | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 177 | 44.25 |

| Female | 223 | 55.75 | |

| Age range | 18–30 | 75 | 18.75 |

| 31–45 | 167 | 41.75 | |

| 46–65 | 120 | 30 | |

| >65 | 38 | 9.5 | |

| Residence | Rural | 153 | 38.25 |

| Urban | 247 | 61.75 | |

| Education | Secondary-school studies | 45 | 11.25 |

| High school studies | 22 | 5.5 | |

| Post-secondary studies | 8 | 2 | |

| Higher education (bachelor’s degree, master’s degree, doctorate) | 325 | 81.25 | |

| Occupation | Student | 64 | 16 |

| Employed | 243 | 60.75 | |

| Unemployed | 11 | 2.75 | |

| Self-employed | 37 | 9.25 | |

| Retiree | 45 | 11.25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Niță, A.; Drăguleasa, I.-A.; Constantinescu, E.; Bonea, D. Geotourism: From Theoretical Definition to Practical Analysis in the Sohodol Gorges Protected Area, Romania. Geographies 2025, 5, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies5040053

Niță A, Drăguleasa I-A, Constantinescu E, Bonea D. Geotourism: From Theoretical Definition to Practical Analysis in the Sohodol Gorges Protected Area, Romania. Geographies. 2025; 5(4):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies5040053

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiță, Amalia, Ionuț-Adrian Drăguleasa, Emilia Constantinescu, and Dorina Bonea. 2025. "Geotourism: From Theoretical Definition to Practical Analysis in the Sohodol Gorges Protected Area, Romania" Geographies 5, no. 4: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies5040053

APA StyleNiță, A., Drăguleasa, I.-A., Constantinescu, E., & Bonea, D. (2025). Geotourism: From Theoretical Definition to Practical Analysis in the Sohodol Gorges Protected Area, Romania. Geographies, 5(4), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies5040053