1. Introduction

Internal migration has become the dominant process of demographic change in most European countries, functioning as the primary mechanism that reshapes urban systems and influences the development of socioeconomic structures at regional and municipal levels [

1,

2]. With the decrease in spatial variations in fertility and mortality rates, internal migration now drives the redistribution of populations across regions and urban systems, fundamentally altering the demographic landscape of contemporary Europe [

3,

4]. The significance of internal migration extends beyond simple population redistribution, as it underpins the efficient functioning of the economy by enhancing labor market flexibility and allowing people to choose the most desired locations [

5,

6]. As individuals move, they redistribute human capital and resources, producing uneven patterns of growth and decline across regions, which have profound implications for regional development and urban planning policies. Internal migration operates across multiple scales, from movements between regions shaped by economic disparities to shifts within the rural–urban continuum, such as relocations from non-metropolitan rural peripheries to metropolitan regions or suburban areas [

7]. The urban hierarchy framework, which organizes settlements by size and function, provides a crucial lens for understanding how small towns and peripheral rural areas relate to larger urban centers within these complex migration systems [

8,

9].

In post-socialist Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), the dynamics of internal migration have been particularly pronounced and shaped by the legacy of centralized planning, rapid economic restructuring, and integration into the European Union [

10]. The transition to a market economy has led to a complex and often contradictory set of urban transformations, characterized by both intensive urban sprawl and significant population decline [

11]. While large metropolitan areas, particularly capital cities, have often emerged as primary growth poles, attracting a significant share of internal migrants, many smaller cities and towns have struggled to adapt to new economic realities, leading to population decline and demographic aging [

12,

13]. This process of spatial polarization, where a few dominant urban centers grow at the expense of peripheral regions, is a common feature of many CEE countries [

14,

15]. However, the specific patterns of migration and their impact on different levels of the urban hierarchy vary considerably across regions, highlighting the need for detailed country-specific analyses [

2].

Within this context, small towns occupy a paradoxical position. While the past two decades have witnessed a renaissance of large metropolitan cores and extensive scholarly attention to metropolitan growth and suburbanization processes, small towns remain critical yet understudied components of national settlement systems [

16,

17]. These settlements often combine affordable housing, access to natural amenities and essential services, and strong local networks, factors that can counterbalance their limited labor market depth and potentially attract specific population groups [

18]. While they may not attract large volumes of in-migrants compared to major metropolitan regions and cities, their relatively small populations mean that even modest in-migration and out-migration can profoundly alter local demographic structures, labor market conditions, and the demand for public services [

19]. This characteristic makes small towns particularly sensitive to migration flows and renders their study essential for understanding broader spatial and socioeconomic transformations. The role of small towns in national migration systems is far from uniform and reflects the diversity of local contexts and regional dynamics. Some serve as intermediate stages in stepwise moves towards the metropolis, whereas others operate as destinations for both the surrounding rural hinterlands and selective in-migration, promoting rural gentrification [

20,

21]. Previous studies confirm the heterogeneity of internal migration: the acceleration of suburbanization and counter-urbanization movements down the urban hierarchy alongside the out-migration of mostly younger people from rural areas and small towns, both of which have significant implications for population distribution and local development [

22,

23].

Despite the growing recognition of the importance of internal migration in shaping contemporary demographic changes and population redistribution across regions and settlement systems, significant gaps remain in our understanding of the role of small towns in migration systems. The migration literature has extensively examined metropolitan growth, suburbanization, and population redistribution in major urban agglomerations, with less scholarly attention devoted to the specific impact on smaller settlements [

24,

25]. This gap is particularly surprising given the outsized demographic effects that even modest flows can have in small-town settings, where population changes can fundamentally alter community resilience and development prospects. Second-tier cities and small towns in the ‘urban age’ are often perceived as a homogeneous category, requiring a more complex understanding of their role and significance within national settlement systems [

26]. This oversimplification fails to capture the diversity of small-town experiences and the varied functions they serve within the migration systems.

These processes underscore the need to examine contemporary internal migration patterns and their effects on the development of small towns. This study aims to explore the patterns of internal migration in Latvia, with a specific focus on the role of small towns and the characteristics of residents who have decided to move to these urban areas. This study addresses the identified gaps in studies on small towns and internal migration by providing a comprehensive analysis of migration flows and migrant composition using high-quality administrative and census data.

This study contributes to the literature on internal migration in CEE by providing a detailed analysis of migration patterns in Latvia, with a specific focus on the role of small towns. Latvia provides a compelling case study for several reasons. First, it has a highly monocentric urban system, with Riga and its metropolitan region concentrating a large share of the country’s population and economic activity. This makes it an ideal case for examining the dynamics of migration in a highly centralized urban hierarchy. Second, like many other CEE countries, Latvia has experienced significant demographic challenges, including population decline and aging, which are closely linked to both international and internal migration patterns. Third, Latvia has a dense network of small towns with diverse historical and economic functions, providing a rich context for exploring the varied roles that these settlements play in the national migration system. Four percent of Latvia’s population lives in 39 small towns. Many of them came into being as historical merchant towns along trade routes, ‘service towns’ for agricultural areas, and centers of Soviet rural industrialization, such as mono-industrial towns. Over the last few decades, several administrative reforms have significantly reduced the number of municipalities in Latvia, and most non-metropolitan small towns have lost their administrative status. Nevertheless, the settlement system creates distinctive migration dynamics that offer insights into how small towns function within a highly centralized urban hierarchy.

Despite the growing body of research on internal migration in CEE, there remains a need for more detailed studies examining the specific dynamics of migration to and from small towns. Much of the existing literature has focused on the growth of large metropolitan areas or the decline of industrial regions, with less attention paid to the more nuanced patterns of migration that shape the demographic and socioeconomic landscape of smaller settlements. This study addresses this gap by providing a comprehensive analysis of internal migration flows in Latvia using high-quality administrative and census data to examine the patterns of migration to and from small towns, the characteristics of migrants, and the changes that have occurred over the past decade.

Specifically, we seek to address the following set of questions:

What role do small towns play for internal migration stocks, flows, and net migration?

How has internal net migration changed the demographic structure of small towns within the context of the urban hierarchy in Latvia between 2011 and 2021?

Who are the individuals relocating to these small towns and in what ways has their composition evolved over the decade?

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 provides a detailed examination of Latvia as a case study, including its urban hierarchy and patterns of population distribution and change.

Section 3 describes the materials and methods, detailing the use of Population Register data (2011–2021) for analyzing migration patterns and individual-level census data for examining migrant composition, along with the binary logistic regression methodology employed.

Section 4 presents comprehensive results on internal migration stocks, flows, and net migration patterns, followed by an analysis of the probability of internal migration to small towns.

Section 5 discusses the findings, considering international evidence and its implications for understanding migration patterns and socio-demographic selectivity.

Section 6 concludes by summarizing the main contributions and identifying implications for local and regional development policies in the context of demographic decline and spatial polarization.

3. Materials and Methods

This study used two primary datasets. First, data from the Population Register spanning 2011 to 2021 capture the key characteristics of internal migration stocks, flows, and net migration within Latvia. This administrative data source reflects annually recorded information on residents’ declared places of residence at the beginning of each year, enabling the analysis of migration dynamics across territorial units and at different levels of the urban hierarchy.

In addition, this study investigates the demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of internal migrants residing in small towns across Latvia using individual-level data derived from the 2011 and 2021 Population Census tracts. Such datasets are crucial for population research because they provide the most reliable information on population composition at the individual level [

27] and contain the necessary information regarding residents’ place of residence, age, gender, ethnicity, and education. Therefore, in the context of Latvia, the census data include details regarding individuals’ permanent place of residence one year before the census date, thereby enabling the identification of one-year internal migrants if the residence municipality had been changed from to 2010–2011 or 2020–2021.

Population composition analysis was performed using binary logistic regression to assess the impact of demographic (gender, age, ethnicity, and family status) and socioeconomic variables (education, economic activity, and year of arrival in Latvia) among non-metropolitan small-town residents’ mobile and non-mobile cohorts.

The mobile group used for this analysis, namely those residents who had in-migrated to a small town within one year of the 2011 or 2021 Census taking place, in both observed years constituted slightly around 3% of the total population (

Table 2), with a total of 1.9 thousand one-year in-migrants in 2011, and 3.1 in 2021.

Therefore, we created two regression models for each year by adding a set of factors to the analysis. As a statistical method, binary logistic regression has applications in various fields, including social sciences and geography, with the intention of understanding the factors that influence a dichotomous outcome. Therefore, this statistical method is commonly used in the analysis of population groups, particularly in migration studies [

28,

29,

30]. Binary logistic regression is a frequently used econometric method to measure the relationship between a categorical target variable (e.g., migration status) and one or more covariates or predictor variables. The analysis is useful for situations in which the outcome for a target variable is binary and can have only two possible outcomes, for instance, being categorized as migrant or non-migrant.

Binary logistic regression models were expressed using the following equation:

where

p(Yi = 1) is the probability of event Y for resident i being equal to 1.

where is the intercept term (constant).

are the coefficients associated with each predictor value .

For every regression model, odds ratios (β) were calculated, which refer to the coefficients associated with the covariates in the logistic regression equation. These coefficients determine the contribution of each predictor variable to the log odds of an event. For example, a positive odds ratio indicates a higher probability of engaging in migration than the reference group.

For each year, the data were incrementally built for every model by adding a new set of characteristics. The first model for each year consisted of demographic variables, while the second added socioeconomic characteristics as a precursor to engaging in the process of internal migration.

Consequently, the analysis yields β coefficients that indicate the contribution of each explanatory variable to the process in terms of log-transformed odds (log-likelihood). A negative coefficient signifies a lower probability of migration than the reference group, whereas a positive coefficient reflects an increased likelihood of migration. In parallel, statistical significance was tested to determine whether group differences from the reference category were meaningful. The models are also supplemented with explanatory values, namely the Nagelkerke R2 and −2 Log likelihood.

Individuals in the pre-working-age group (0–14 years) were excluded from the analysis, as this age group is commonly understood in migration literature to be dependent on the mobility patterns of older family members [

31]. Moreover, the results were interpreted in conjunction with educational level and employment status, given that younger children are not independently active in the labor market.

Overall, binary logistic regression is particularly well-suited for studies regarding population composition for several reasons, as it is specifically designed to model the relationship between a set of predictor variables and a dichotomous outcome. Logistic regression can handle this mix of variable types without requiring any transformations and allows interpretation in terms of odds ratios, which provide a measure of the association between each predictor variable and the likelihood of the outcome occurring.

Despite the strengths of the data and methods used in this study, it is important to recognize their limitations. First, the Population Register records only officially declared changes in residence. As a result, short-term or temporary moves may go unreported, potentially leading to an underestimation of internal migration. Nevertheless, because residents in Latvia are legally required to register their place of residence, we consider the register data to provide a reasonably accurate reflection of long-term migration patterns. Second, census data are collected only once every ten years and include a measure of residence change for the year preceding the census. This restricts the individual-level data analysis to a single year prior to each census. Third, although binary logistic regression is a powerful method for examining migration determinants, it assumes that the independent variables are not highly correlated. We tested for multicollinearity in our model and found it to be negligible. It is also important to note that odds ratios from binary logistic regression cannot be directly compared across years [

32]. Therefore, we analyzed each year separately and compared patterns rather than coefficients. Finally, because our study relied on observational data, we could identify associations, but not causal relationships. For example, while we found that individuals with a certain level of education are more likely to move to a small town, we cannot conclude that education itself causes this relocation.

Compared with alternative approaches, such as the linear probability model, which can yield predicted probabilities outside the 0–1 range [

33], or modified Poisson regression, which is more common in epidemiology [

34], logistic regression offers greater interpretability and methodological consistency in population studies [

35]. Probit regression was also considered; however, because it yields substantively similar results, but coefficients are less readily interpretable [

36], it was not adopted. Finally, the very large sample size of the census data ensures that logistic regression produces efficient and stable parameter estimates, further supporting its suitability for this analysis [

35].

4. Results

4.1. Internal Migration: Stocks, Flows and Net-Migration

Latvia’s politics, economy, and society underwent a complete transformation after the collapse of the Soviet regime and the introduction of neoliberal market reforms in the 1990s. The market reforms resulted in significant changes in the former centrally planned economy, with the hardest hit areas being those linked to the industrial and agriculture sectors, including large cities, mono-industrial towns, and former centers of Soviet farming. In the early 2000s, the country’s move towards closer integration with the European market and its accession to the European Union in 2004 led to an influx of foreign direct investment and, subsequently, integration into global production networks. However, significant differences emerged between the Riga Metropolitan Region and non-metropolitan regions in terms of economic development, investment, wages, and labor and housing markets. Moreover, these regional disparities have only deepened over time, affecting internal migration within the country, with a clear dominance of the capital city and its suburbs.

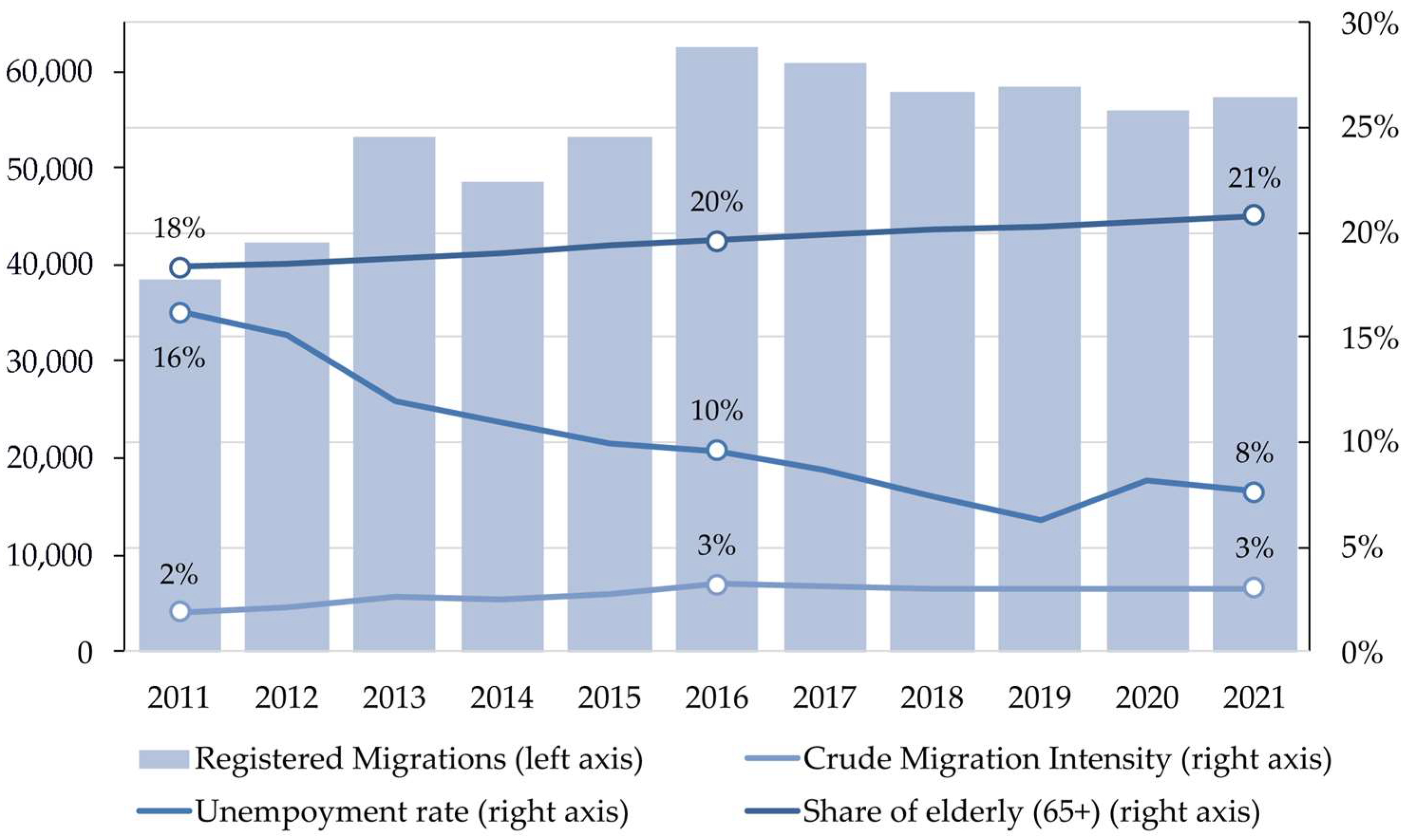

The decade spanning 2011 to 2021 was characterized by two notable periods of crisis. Initially, the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, coupled with the subsequent economic downturn, persisted until 2012 in Latvia, affecting internal migration patterns. The end of this decade was defined by the ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021, which profoundly affected human mobility during the unprecedented health crisis. Throughout this decade, internal migration stocks demonstrated variability with annual fluctuations (

Figure 2). Nonetheless, a general upward trajectory was evident over time. On average, slightly more than 53,000 registered relocations are documented annually. At the outset, the total number of registered migrations was comparatively low; however, despite the challenges posed by COVID-19, it increased by the end of the study period, with a slight deviation in 2020.

The relationship between internal migration and factors such as unemployment and aging during the decade under consideration cannot be definitively established. In Latvia, the unemployment rate has experienced a steady decline since the economic crisis at the beginning of the decade. Simultaneously, although society is gradually aging, this demographic shift has not substantially curtailed internal migration, even though it is an inherently age-selective process.

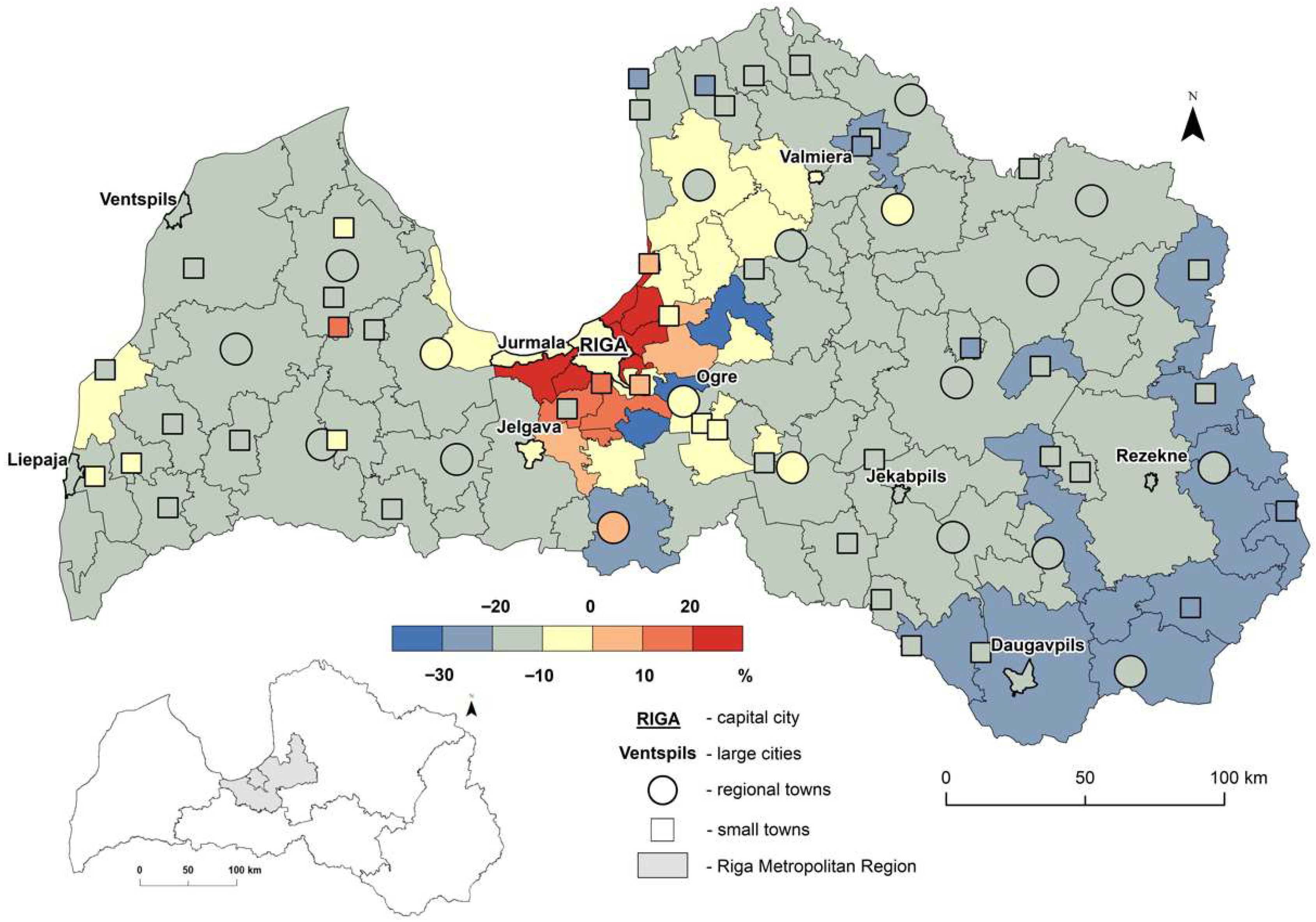

The spatial patterns of internal net-migration, illustrated in

Figure 3, demonstrate a clear core-periphery dynamic within the urban hierarchy. Net-migration varies considerably across the urban hierarchy, with positive net-migration rates concentrated in the Riga Metropolitan Region and some large cities. The map demonstrates that positive net-migration is largely confined to the suburbs of the capital city and a limited number of municipalities in proximity to major urban centers, while most non-metropolitan territories, particularly those in peripheral locations, experienced sustained population losses through out-migration.

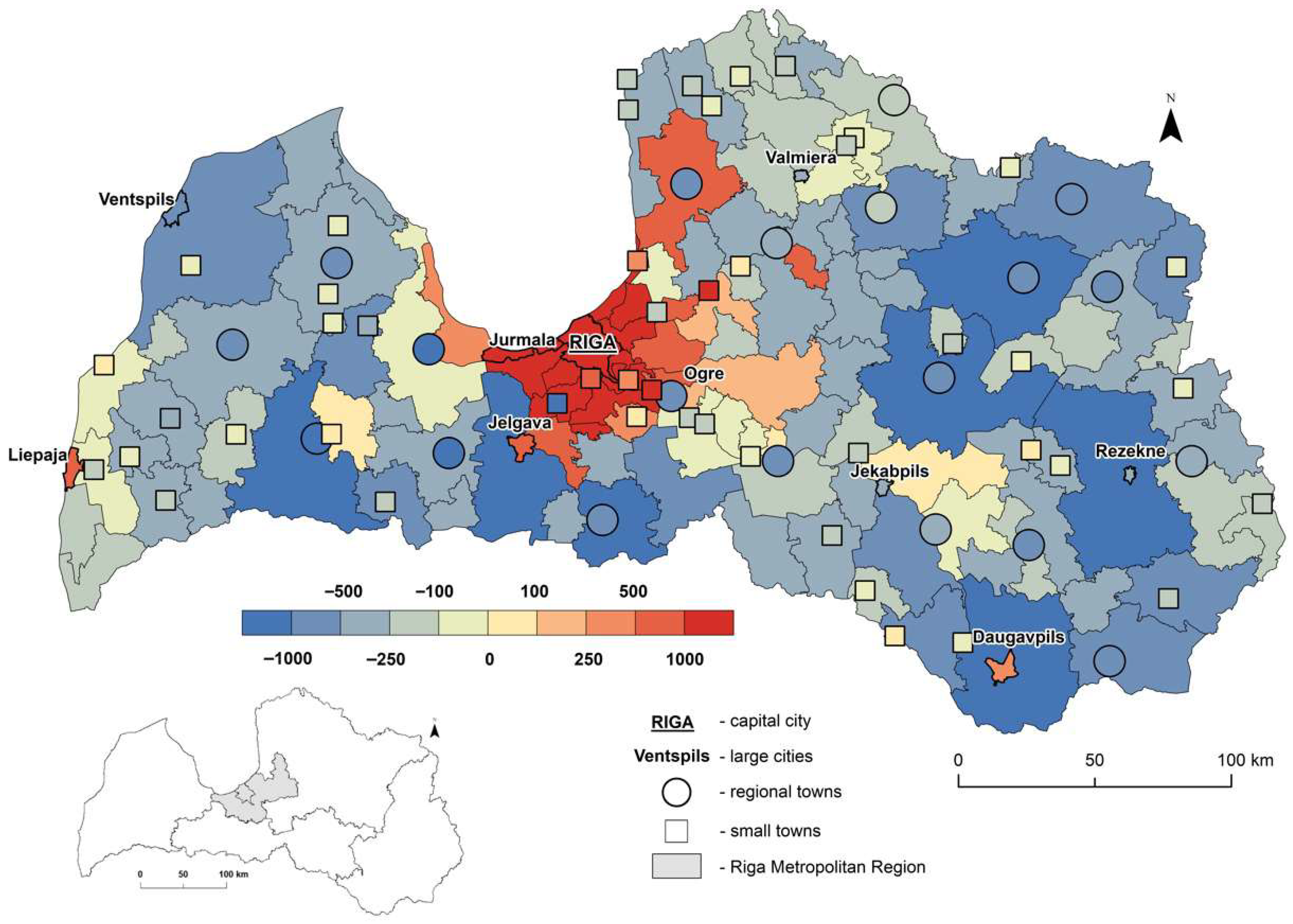

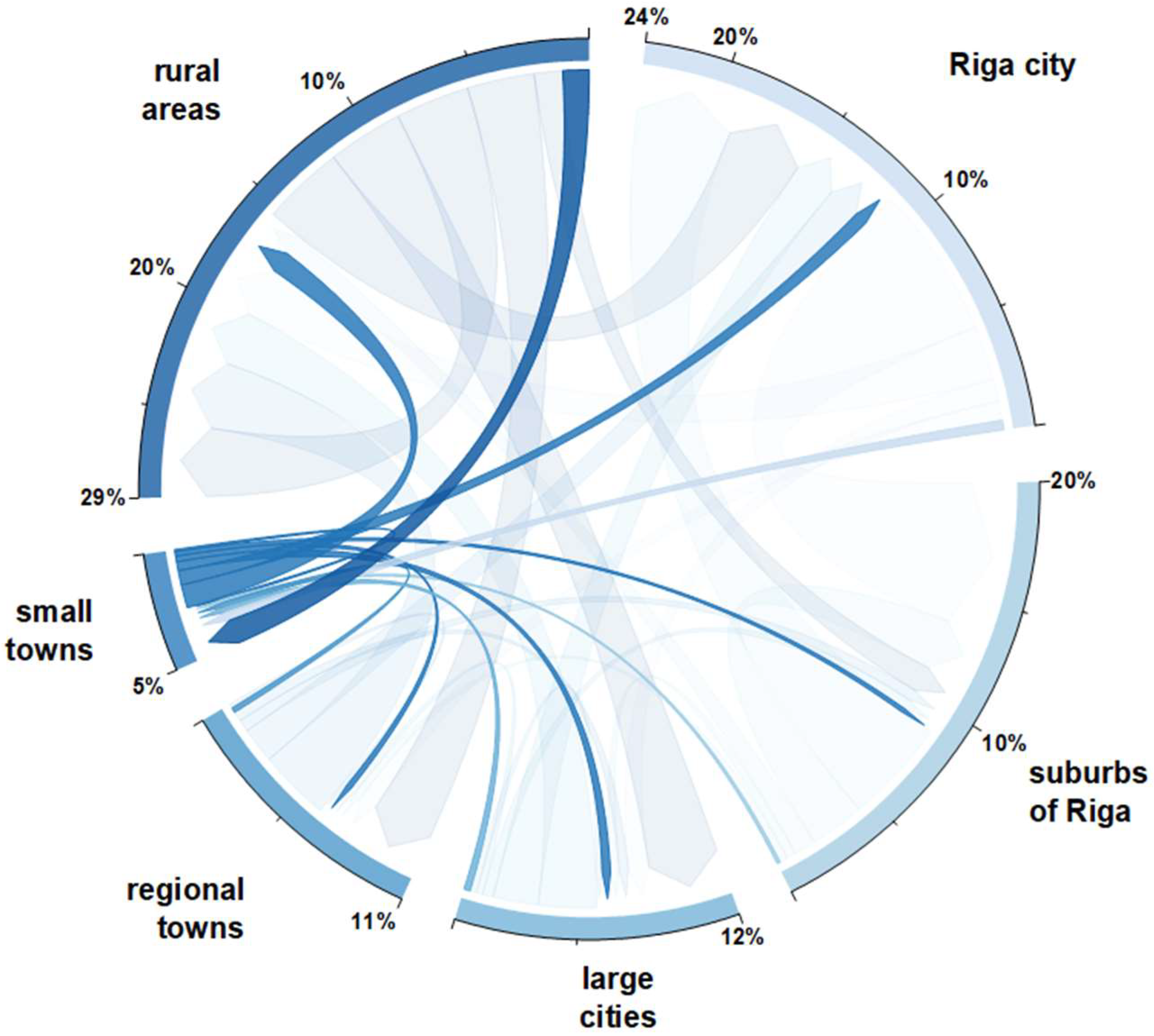

The analysis of migration flows, specifically those involving small towns, as shown in

Figure 4, reveals complex patterns of population exchange across the urban hierarchy. Over the 2011–2021 period, small towns participated in just 5% of all migration flows, with total in-migration and out-migration stocks indicating migration turnover despite relatively modest net migration losses. The circular plot of migration flows illustrates that small towns primarily lose population to higher-order urban centers, particularly Riga City, other large cities, and regional towns, while gaining residents predominantly from rural areas. Thus, small towns function as intermediate destinations within Latvia’s migration system, receiving migrants from rural areas while simultaneously losing population to the larger urban centers and suburbs of the capital city. In terms of migration stocks, the population exchange with rural areas is greater than that with higher-order urban areas.

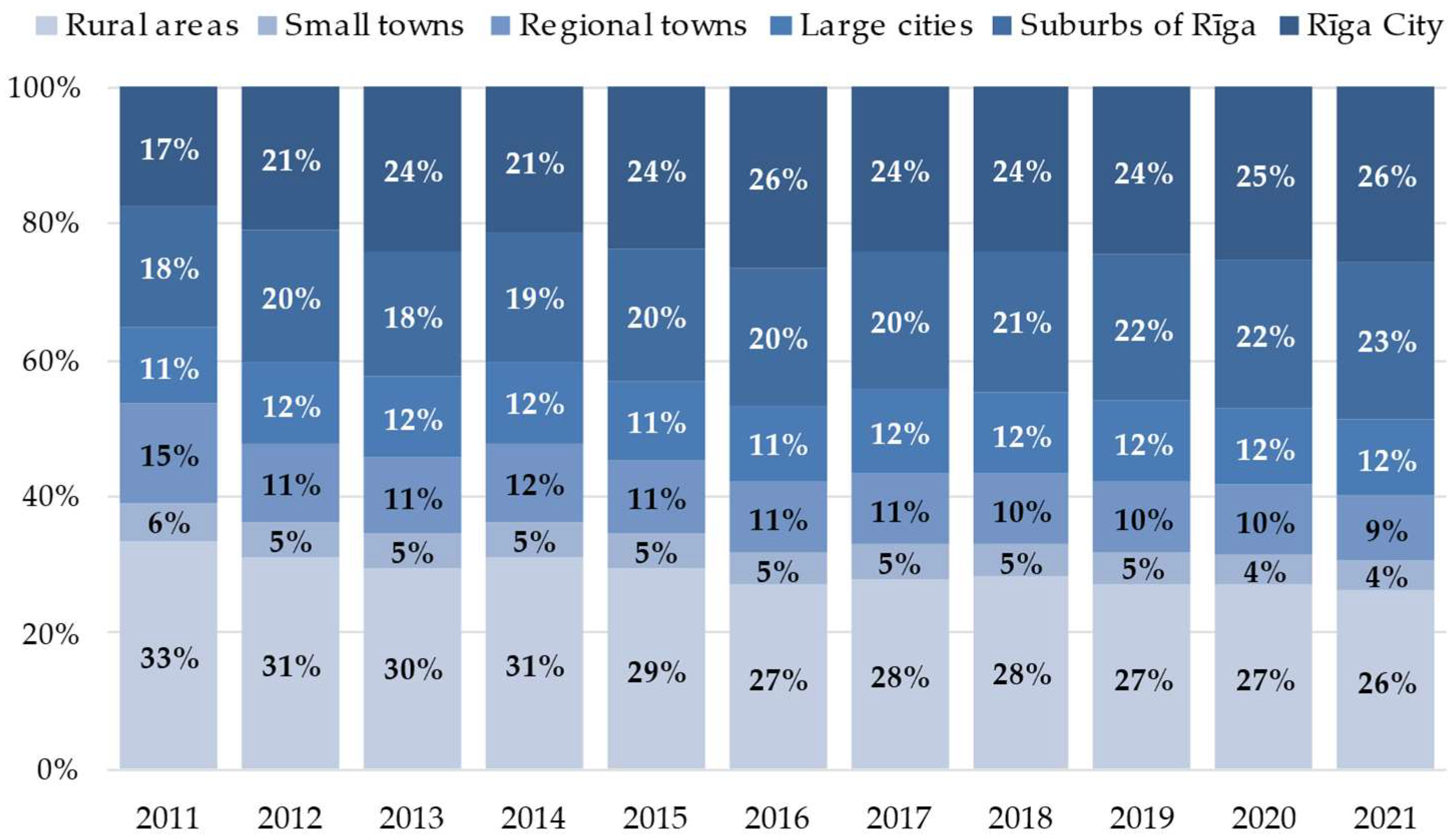

Migration flows across the urban hierarchy demonstrate a clear pattern of upward mobility within the settlement system. The interlinks between the capital city and its suburban areas in the Riga metropolitan region are also clearly visible, as migration flows in this functional urban region accounted for 44% of the total registered migration during the decade under consideration. Over the years, the total migration stock within the Riga Metropolitan Region consistently increased, whereas the proportion of rural areas declined significantly (

Figure 5).

The share of regional towns in the turnover of registered internal migration has also declined significantly, whereas the proportion of large cities and small towns has remained stable and has not changed significantly.

Table 3 presents a detailed breakdown of internal net migration by age group, revealing pronounced age-selective migration patterns across the urban hierarchy. Young adults (15–34 years) demonstrated the highest propensity for migration, with Riga city gaining 27,800 young residents, while all non-metropolitan settlement categories experienced substantial losses in this age cohort. Small towns have lost 3900 young adults, representing the most significant component of their overall migration deficit. Conversely, the suburbanization process is evident in the migration patterns of families with children and middle-aged adults. Riga’s suburbs gained across all age groups, with particularly strong gains among the 35–64 age group and children aged 0–14, indicating family oriented residential mobility. Notably, small towns demonstrated modest gains in the youngest (0–14) and oldest (65+) age cohorts, suggesting their continued role in accommodating families with young children and retirement-age populations.

Age-specific migration patterns underscore the demographic challenges faced by small towns and non-metropolitan regions. The persistent out-migration of young adults not only reduces the immediate population base but also compromises future demographic vitality through reduced birth rates and accelerated population aging. The modest in-migration of families and elderly residents to small towns while providing demographic stability is insufficient to offset losses in economically active age groups. These results collectively demonstrate that internal migration in Latvia follows a clear hierarchical pattern, with population flows predominantly directed upward through the urban system towards the Riga Metropolitan Region. Small towns, while experiencing an overall population decline, continue to play a complex role in the migration system, serving both as destinations for rural out-migrants and as sources of migrants to higher-order urban centers. The age-selective nature of these flows has profound implications for the demographic and socioeconomic sustainability of small towns and non-metropolitan regions in Latvia.

4.2. Probability of Internal Migration to Small Towns: Migrant Composition

The probability of individuals migrating into small towns was evaluated using odds ratios (β) derived from logistic regression analysis. Four models were constructed for 2011 and 2021. Models 1 and 3 (see

Table 4 and

Table 5) incorporate solely demographic variables, including gender, age (limited to individuals aged 15 and over), ethnicity, and family status. Models 2 and 4 retain these demographic factors while additionally accounting for socioeconomic characteristics of small town residents, namely educational level, economic activity status, and year of arrival in Latvia.

The in-migration odds to small towns in 2011 can be seen in

Table 4 among the demographic and socioeconomic population groups. Model 1 incorporated demographic variables exclusively, including gender, age, ethnicity, and family status. The results indicated that gender had no statistically significant association with the likelihood of migration. Age demonstrates a strong negative relationship with migration propensity, with individuals aged 35–64 years showing significantly lower odds of migration and those aged 65+ years exhibiting even more pronounced negative associations. Ethnicity has emerged as a significant predictor, with minority populations demonstrating substantially lower odds of migrating to small towns than ethnic Latvians. Family status also proved statistically significant, with married individuals showing a reduced likelihood of migration relative to single persons.

Model 2 adds socioeconomic variables, specifically educational level, economic activity status, and temporal migration patterns (year of arrival in Latvia: after 2000 as reference versus before 2000 or born in Latvia). The inclusion of these additional variables improves model fit, as evidenced by the increased Nagelkerke R2 value of 0.095 and a reduced −2 Log likelihood. The demographic variables maintained their statistical significance and directional relationships, as observed in Model 1, with some modifications in the effect sizes.

Socioeconomic variables reveal important patterns in migration behavior. Educational level demonstrated a clear gradient effect, with individuals possessing secondary education showing significantly lower migration odds than those with higher education and those with middle school education or lower exhibiting the most pronounced negative association. Economic activity status presents a more complex pattern, with unemployed individuals demonstrating a significantly higher migration propensity than employed individuals, whereas economically inactive individuals show a reduced migration likelihood. The temporal dimension of migration history is highly significant, with individuals who arrived in Latvia before 2000 or were born in the country showing substantially lower odds of in-migration to small towns.

For 2021, notable shifts in the significance and direction of the demographic predictors emerged, as shown in

Table 5. Gender, which showed no significant association in 2011, demonstrated a statistically significant positive relationship in 2021, with females exhibiting higher migration odds than males. Age maintains its strong negative association with migration propensity, with the 35–64 age group showing reduced odds and the 65+ group demonstrating even more pronounced negative effects. Remarkably, ethnicity loses its statistical significance among in-migrants in 2021, representing a substantial departure from the 2011 pattern in which minority status was a strong negative predictor. Similarly, family status became non-significant, contrasting sharply with the strong negative association observed in 2011.

The model improvement from the addition of socioeconomic variables for the 2021 data is less pronounced than that observed in 2011, suggesting potential changes in the relative importance of these factors over the decade. Gender maintained a significant positive association for females, although with a slightly reduced effect size compared to Model 3. Age relationships persisted with similar magnitudes and high statistical significance. The loss of significance for ethnicity and family status observed in Model 3 continued into the full specification.

Education level maintains its gradient relationship with migration propensity, although with somewhat attenuated effects compared to 2011. Individuals with secondary education show lower odds than those with higher education, while those with middle school education or lower continue to demonstrate a reduced migration likelihood, although the effect is considerably weaker than that in 2011. Economic activity patterns show notable changes, with unemployment losing its significant positive association with migration, whereas economic inactivity maintains a negative relationship. The temporal migration variable remains highly significant, with individuals arriving before 2000 or born in Latvia showing substantially reduced migration odds.

5. Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of internal migration patterns in Latvia, with a particular focus on the role of small towns. Our findings reveal a complex and dynamic migration landscape, characterized by the enduring dominance of the capital city, Riga, and its metropolitan region, alongside a persistent pattern of population decline in most non-metropolitan areas. The analysis of migration flows and migrant characteristics has shed new light on the processes of spatial polarization and demographic change that are shaping contemporary Latvia. In this section, we discuss the key findings of our study in relation to the broader literature on internal migration in Europe and post-socialist countries, and we consider the implications of our findings for regional development policies.

5.1. The Enduring Dominance of the Capital and the Decline of the Periphery

Our findings confirm the continued dominance of the Riga metropolitan region as a primary destination for migrants in Latvia. This is consistent with the broader pattern of spatial polarization observed in many other CEE countries, where capital cities have become the main engines of economic growth and magnets for internal migration [

12,

13]. The concentration of population and economic activity in and around Riga is a long-standing feature of Latvia’s urban system. However, our analysis shows that this trend has intensified over the past decade. The suburbs of Riga, in particular, have experienced rapid population growth, driven by a combination of out-migration from the city center and in-migration from other parts of the country. This process of suburbanization is a common feature of many European cities, but in the Latvian context, it is taking place against a backdrop of overall population decline, which makes the concentration of growth in the Riga region more striking.

The flipped side of the coin is the continued population decline in most non-metropolitan regions. Our analysis shows that all categories of non-metropolitan settlements—large cities, regional towns, and small towns—have experienced net migration losses over the past decade. This is a worrying trend, as it suggests that these areas are struggling to attract and retain residents, which could have serious consequences for their long-term economic and social viability. The decline of non-metropolitan regions is a common challenge in many parts of Europe, but it is particularly acute in post-socialist countries, where the transition to a market economy has often led to the decline of traditional industries and out-migration of young and skilled workers [

11].

5.2. The Heterogeneous Role of Small Towns in the Migration System

While the overall trend in non-metropolitan areas is declining, our analysis reveals a more nuanced picture when we look specifically at small towns. Although most small towns experience net migration losses, there is considerable variation in their migration patterns. Some small towns, particularly those located near Riga or in areas with attractive natural amenities, have managed to attract a significant number of new residents. This suggests that small towns can play a positive role in the migration system, offering an alternative to high-density living in the capital and isolation in rural areas. Our findings are consistent with studies from other European countries that have shown that small towns can be attractive destinations for certain population groups, such as families with young children and retirees [

37,

38].

The hierarchical nature of migration patterns observed in Latvia closely aligns with the established theoretical frameworks in migration research, particularly the concept of stepwise migration and the urban hierarchy model [

6,

22,

39]. The predominant upward flow of migrants through the settlement system, with the Riga Metropolitan Region capturing the majority of positive net migration, reflects the continued importance of economic opportunities, educational institutions, and urban amenities in shaping migration decisions. However, the persistence of bidirectional flows involving small towns suggests that these settlements continue to offer specific attractions that appeal to certain population segments, challenging simplistic assumptions about universal preferences for larger urban centers.

5.3. Net-Migration and the Changing Demographic Structure of Small Towns

The age-selective nature of migration patterns is one of the most significant findings of this study, with profound implications for understanding the demographic sustainability of small towns. The substantial out-migration of young adults from small towns, totaling 3900 individuals over the decade, reflects broader patterns observed across Europe, where younger populations gravitate toward metropolitan areas for educational and employment opportunities [

40]. This pattern is consistent with human capital theory, which suggests that younger, more educated individuals are more likely to migrate to locations offering greater returns on their skills and investments in education [

6].

However, the modest migration of younger age groups (0–14 years) and elderly residents to small towns reveals a more nuanced picture of migration selectivity. The positive net migration of 600 children and 500 elderly residents suggests that small towns retain certain attractions for specific life course stages, potentially related to quality-of-life considerations, housing affordability, and community characteristics. This pattern resonates with research on counter-urbanization and lifestyle migration, which highlights the importance of non-economic factors in migration decisions, particularly for households seeking alternative residential environments [

41,

42].

These demographic changes indicate a polarization trend in small towns, where the population base is aging, while simultaneously accommodating young families with children, albeit in smaller numbers. This evolution raises questions regarding the long-term socioeconomic sustainability of small towns and their capacity to meet the needs of a diversifying population.

5.4. Evolving Composition of in-Migrants to Small Towns

The temporal evolution of migration determinants, as revealed through logistic regression analysis, provides crucial insights into the changing dynamics of small-town migration. A comparison between the 2011 and 2021 migrant compositions revealed significant temporal shifts in the determinants of internal migration to small towns in Latvia. The emergence of gender as a significant predictor in 2021, with females showing higher migration propensity, suggests evolving patterns in migration behavior that may reflect changing socioeconomic conditions or labor market dynamics [

43]. The loss of statistical significance for ethnicity represents a particularly notable finding, potentially indicating reduced ethnic disparities in migration patterns or changes in the socioeconomic integration of minority populations [

44,

45].

The weakening of family status effects and the loss of significance of unemployment as a migration driver suggest that the economic and social factors influencing migration decisions may have evolved substantially [

46]. These changes occur against a backdrop of relatively stable age-related patterns and persistent educational gradients, indicating that while some demographic and socioeconomic determinants remain consistent, others have undergone significant transformation in their relationship with internal migration behavior.

These findings underline the diversification of small town in-migration profiles and reinforce the importance of understanding migration selectivity not only by age but also by gender and ethnicity.

5.5. Implications for Migration Theory

These findings contribute to several theoretical debates in migration research, particularly regarding the role of settlement hierarchies in shaping population movements and the factors that drive migration selectivity. The persistence of hierarchical migration patterns in Latvia, despite significant economic and social transformations since the EU accession, supports the continued relevance of central place theory and urban hierarchy models in understanding contemporary migration systems [

47]. However, the complexity of migration flows involving small towns indicates that existing theoretical frameworks require further refinement to more accurately reflect the multidirectional and life course–dependent dynamics of contemporary migration systems, particularly given the heterogeneous nature of small towns within the national economic and social context [

18].

The age-selective migration patterns observed in Latvia align closely with life course perspectives on migration, which emphasizes the importance of individual and family life stages in shaping mobility decisions [

48,

49]. The concentration of young adults migrating from small towns reflects the timing of key life transitions, including the completion of secondary education, entry into higher education, and early career development. Conversely, the modest in-migration of families with children and elderly residents suggests that small towns may serve specific functions at different life-course stages, offering environments conducive to child-rearing or retirement.

A comparative analysis with other European contexts reveals both the similarities and distinctive features of Latvia’s small-town migration patterns. The dominance of metropolitan areas in capturing positive net migration mirrors trends observed across the CEE, where capital cities have emerged as primary growth poles in post-socialist urban systems [

50,

51]. However, the persistence of small towns as migration destinations, albeit with modest flows, contrasts with the more pronounced decline patterns observed in other post-socialist contexts [

52,

53]. This suggests that local institutional factors, infrastructure, or community dynamics in Latvia may moderate broader regional trends.

5.6. Policy Implications and Further Research

These findings underscore the need for regional development strategies to adopt a more nuanced understanding of the role of small towns in internal migration systems. Rather than viewing these settlements through the lens of inevitable decline, policy approaches should acknowledge their dual function as transitional nodes in rural-to-urban migration pathways and viable residential destinations for specific demographic groups [

26].

Targeted policy interventions are essential for strengthening these roles. Enhancing infrastructure, improving access to essential services, and fostering inclusive labor markets could increase the attractiveness of small towns to a wider range of population segments [

54]. In particular, a closer examination of the demographic and socioeconomic composition of in-migrant populations can provide valuable insights into how small towns might better retain economically active individuals by identifying which conditions and attributes make these areas attractive despite broader structural limitations.

Moreover, policies sensitive to life-course dynamics can help small towns retain and attract diverse population groups. Family friendly measures, along with age-inclusive urban planning, may support the settlement and long-term integration of young families and older adults. By aligning development strategies with the evolving needs of internal migrants, small towns can continue to play a meaningful role in promoting balanced territorial development and demographic resilience.

Although this study offers valuable insights into the migration dynamics of small towns in Latvia, several limitations must be acknowledged, which suggest promising avenues for further research. First, it combines elements of both stock- and flow-based approaches to internal migration over the past decade. However, the demographic composition indicators reflect a one-year snapshot, limiting the ability to draw conclusions about population change processes throughout the full ten-year period. Consequently, from a demographic structure perspective, the findings provide a static view rather than a dynamic account of compositional transformation. Second, the explanatory power of the regression models, as measured by Nagelkerke’s R2, declined in 2021 compared to 2011. This reduction suggests a diminishing role of traditional demographic and socioeconomic variables in predicting migration behaviors. It is likely that contextual, social, emotional, and environmental factors have gained greater importance in shaping migration decisions—factors that were not captured within the scope of this study and would merit dedicated exploration in future research.

Third, it is important to consider the specific characteristics of Latvia’s settlement system, particularly the hierarchical distinction between small towns located in non-metropolitan regions (the focus of this study) and those situated within the metropolitan area of the capital city. Small towns in metropolitan regions often exhibit more favorable demographic and economic characteristics. Therefore, a comparative analysis of these two categories of small towns can offer valuable insights.

6. Conclusions

This study examines the patterns and determinants of internal migration to small towns in Latvia over a transformative decade marked by economic recovery and pandemic disruption. Through a comprehensive analysis of administrative and census data, we have demonstrated that small towns occupy a paradoxical position within Latvia’s migration system, serving simultaneously as destinations for rural out-migrants and sources of population for higher-order urban centers while accounting for only 5% of the total migration turnover.

In response to our first research question, which asked about the role of small towns in internal migration, our analysis showed that small towns play a relatively minor role in terms of the overall volume of migration flows. The vast majority of internal migrants in Latvia have moved to the Riga metropolitan region, which has further consolidated its position as the country’s primary demographic and economic hub. However, our findings also show that small towns are not homogeneous. While most small towns have experienced net migration losses, some have managed to attract a significant number of in-migrants, particularly those located near Riga or in areas with attractive natural amenities. This suggests that small towns can play a positive role in the migration system, offering an alternative to both the high-density living of the capital and the isolation of rural areas.

Our second research question concerns the impact of internal migration on the demographic structure of small towns. Our analysis has shown that internal migration has a significant impact on the demographic structure of small towns, but the nature of this impact varies depending on the specific characteristics of the town. In general, the out-migration of young people is leading to demographic aging of the population in many small towns, which could have serious consequences for their long-term viability. However, in some small towns, the in-migration of families with young children helps to rejuvenate the population and ensure a more balanced demographic structure.

Our third research question focused on the characteristics of individuals relocating to small towns. Our analysis shows that migrants to small towns are a more heterogeneous group than migrants to the Riga metropolitan region. While some small towns attract highly educated professionals, others attract a more diverse range of migrants, including families with children, retirees, and individuals with lower levels of education. This suggests that small towns can play various roles in the migration system, from providing affordable housing for families to offering a peaceful and attractive environment for retirees.

These findings contribute to a broader theoretical understanding of migration systems in monocentric, post-socialist contexts, demonstrating how small towns function as intermediary spaces within highly polarized settlement systems. While they are not the primary drivers of migration flows, they are nevertheless important destinations for a significant number of migrants, and they have a significant impact on the demographic and social fabric of the country. For policymakers, these findings underscore the urgent need for differentiated approaches to small town development that recognize both their demographic vulnerabilities and residual attractiveness to specific population groups. Strategies should focus on enhancing the comparative advantages that attract families and retirees while addressing the structural factors driving youth out-migration.