Abstract

Background: Quantitative gait analysis is essential in both clinical and research contexts; however, traditional marker-based motion capture systems are costly and burdensome. Advances in three-dimensional markerless motion capture (3D-MMC) offer more accessible alternatives; however, they lack standardized protocols. Objectives: The present study aimed to establish a standardized protocol and procedures for 3D MMC-based gait analysis using OpenCap and to quantify the reliability and within-session precision of key spatiotemporal gait parameters. Methods: Fifty healthy university students (mean age = 22.15 ± 2.12 years) completed walking trials along a 10 m walkway under single-task (ST) and five dual-task (DT) conditions of varying cognitive complexity. Gait data were collected using a two-camera OpenCap 3D-MMC system, with standardized calibration, lighting, clothing, and trial segmentation. Spatiotemporal parameters were extracted, and within-session relative reliability was quantified using two-way mixed-effects intraclass correlation coefficients, and absolute reliability was quantified using general linear model–derived within-subject error (standard error of measurement, SEM) and minimal detectable change (MDC). Repeated-measures ANOVA with Bonferroni corrections were used to examine condition-related differences. Results: Of 500 trials, 491 (98.2%) were successfully processed. Within-subject test–retest reliability ranged from moderate to excellent for all variables, with gait speed, stride length, and cadence showing the highest ICCs and smallest SEM and MDC values, and step width and double support exhibiting larger measurement error. Conclusions: This study establishes a standardized 3D-MMC protocol for gait analysis using OpenCap and demonstrates good to excellent within-session relative and absolute reliability for most spatiotemporal gait parameters in healthy young adults. Dual-task walking is used here to illustrate how trial-averaged OpenCap measurements and their SEM/MDC can be used to determine which condition-related changes in gait exceed measurement error.

1. Introduction

Quantitative gait analysis is a cornerstone of movement science, rehabilitation, and clinical neurology, providing objective measures of locomotor function that support diagnosis, prognosis, and intervention evaluation. Traditionally, three-dimensional (3D) motion capture has relied on marker-based optical systems, which are considered the gold standard for kinematic analysis; however, they are constrained by high costs, specialized infrastructure, and participant burden [1,2]. Advances in computer vision and machine learning have enabled the emergence of markerless motion capture (MMC), which derives body kinematics from standard video streams using human pose estimation algorithms. 3D-MMC systems are significantly decreasing the expenses associated with traditional motion capture, as machine learning reduces the reliance on specialized cameras and equipment. Open-source pose estimation is a valid and reliable method for measuring gait parameters (kinematics and spatiotemporal), comparable to that of a laboratory-based 3D Motion Capture system using markers [3,4,5]. Thus, the 3D-MMC approach offers greater accessibility and scalability by reducing setup complexity and facilitating data collection in both laboratory and real-world environments [4,6].

Recent systematic reviews have consistently demonstrated that 3D-MMC achieves good to excellent validity and reliability for spatiotemporal gait parameters compared to marker-based systems, with intraclass correlation coefficients often exceeding 0.90 for metrics such as walking speed, cadence, and step length [1,4,7]. However, kinematic accuracy is joint and plane-dependent: sagittal hip and knee angles show moderate to good agreement, while ankle kinematics and non-sagittal planes remain less reliable [1,2,4]. These findings underscore the importance of adhering to rigorous methodological practices to optimize measurement quality and ensure comparability across studies. Several reviews emphasize that outcomes are susceptible to factors such as camera configuration, calibration procedures, participant setup, and trial segmentation, yet standardized protocols for MMC gait analysis remain scarce [2,8]. The most recent systematic review and meta-analysis specifically focusing on OpenCap has determined that validity and reliability are generally good to excellent, but that there is greater heterogeneity in the methodological framework and a lack of standardized procedures [7].

Dual-task (DT) gait paradigms are widely used to probe the interaction between locomotion and concurrent cognitive demands, and DT-related changes in spatiotemporal parameters are frequently interpreted as indicators of cognitive–motor interference. However, meta-analytic work also emphasizes substantial methodological heterogeneity in DT protocols and outcome definitions, which complicates comparisons across studies and limits the interpretability of DT cost metrics [9,10,11,12,13]. In this context, markerless motion capture protocols that are explicitly documented and accompanied by quantitative estimates of reliability and measurement error may provide a useful foundation for more reproducible DT gait research.

Therefore, the primary objective of the present study was to establish a standardized protocol and procedures for 3D-MMC-based gait analysis using OpenCap and to quantify the within-session relative and absolute reliability of key spatiotemporal gait parameters obtained with this protocol. By documenting procedures for camera positioning, calibration, lighting, participant setup, and trial segmentation, this work aims to advance reproducible, comparable MMC practices. As a secondary, illustrative objective, we applied this protocol to a set of simple cognitive dual-task walking conditions and used the intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs), standard error of measurements (SEMs), and minimal detectable change (MDC) values to determine which dual-task-related changes in gait parameters can be distinguished from measurement error.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Fifty healthy university students (N = 50; age range: 18–28 years; mean age = 22.15 ± 2.12 years; 26 females, 24 males) voluntarily participated in this study. All participants reported no known neurological, musculoskeletal, or cognitive impairments that could affect walking or cognitive task performance. Written informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its updates, and the study protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committee (UCAM—TC/05-24).

2.2. Design

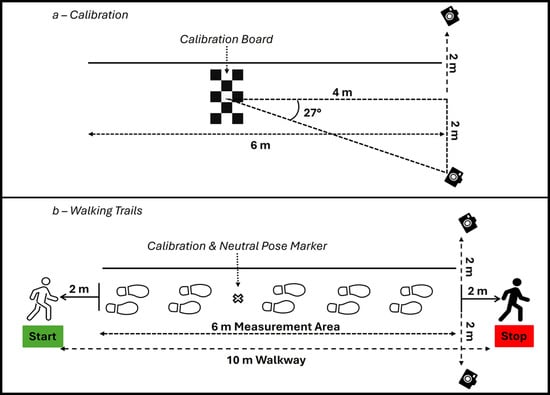

Gait analysis was conducted along a straight 10 m walkway, with the first and last 2 m designated for acceleration and deceleration, respectively. The middle 6 m constituted the “measurement area” [14]. A two-camera 3D-MMC system (OpenCap, iOS series 10 and 12) was used to record spatiotemporal gait parameters [15,16]. Each device was mounted on a tripod at a height of 80 cm and positioned 2 m laterally from the walkway’s midline (4 m between cameras), aligned with the end of the 6 m measurement area. A fixed floor marker, located 4 m from the camera centerline, served as the reference for calibration checkerboard placement and participant neutral pose positioning. This setup yielded a 27-degree angle off centerline of the walkway, providing standardized and comparable data across trials (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic for calibration and walking trials.

The laboratory was equipped with fixed overhead lighting, composed of evenly spaced (2 m on center) LED ceiling panels, which provided consistent ambient illumination throughout the capture space. Lighting measurements were recorded at multiple locations, including the calibration board, camera positions, and throughout the start and stop points of the walkway. Illumination levels were assessed using a digital lux meter (MT-912, Shenzhen Flus Technology Co., Shenzhen, China). The illumination measurements averaged 963.8 lux with a standard deviation of 108.2 lux, indicating sufficient brightness for laboratory settings, according to the European Standard (EN 12464-1:2011) for lighting of workplaces [17]. This uniform lighting environment was maintained to ensure optimal video quality, reduce shadowing, and support accurate skeletal tracking during data collection.

During recruitment and before data collection, participants were instructed to wear form-fitting exercise-type clothing of darker shades (i.e., shorts, leggings, or form-fitted pants, a form-fitting t-shirt or top that did not fall below the hips, and tennis shoes or sneakers). The darker shades were in contrast to our grayish data collection area (our laboratory floor and walls are colored in light gray or beige tones), as suggested in the OpenCap best practices published online [15]. If participants attended data collection wearing light-colored or loose-fitting clothing, we asked them to change into black leggings that were provided by the research staff.

2.3. Procedures

Each session began with the calibration of the OpenCap system. A calibration board (Calib.io; a 4 × 5 grid of 35 mm black-and-white checkered squares) was mounted at a height of 80 cm on a rigid (wooden) whiteboard equipped with wheels for ease of positioning. The board was aligned with the fixed floor marker to ensure consistent calibration across sessions. The two-camera system captured images of the checkerboard to compute intrinsic and extrinsic camera parameters and establish a shared 3D coordinate system for data collection.

Following camera calibration, participants completed a neutral pose calibration by standing over the fixed marker in a relaxed anatomical posture: feet hip-width apart, arms at their sides (not touching the body), and facing forward. The neutral pose was captured simultaneously by both cameras to allow the OpenCap software (www.opencap.ai) to initialize the participant’s biomechanical model. This step ensured accurate mapping of joint centers and segment orientations relative to the calibrated 3D space, providing a reference for subsequent motion tracking during walking trials.

Each trial was conducted over the full 10 m walkway, with the middle six meters designated as the measurement area. Instructions for all the walking trials were standardized and were as follows: “You will complete a series of walking trials at a comfortable walking pace. A ‘comfortable’ walking pace is your everyday walking pace, which you would typically use in your normal activities when not in a rush. Walk at a comfortable walking pace all the way through this white line (the investigator signals to the marked line at the end of the 6-m measurement area, directly in line with the iOS cameras). The instructions will be “comfortable walking pace, all the way through the white line, Ready, Set, GO! Only start after I say GO.” Participants were then asked if they had any questions or concerns that the investigator needed to clarify. Prior to each walking trial (single-task and dual-task), the instructions “comfortable walking pace, all the way through the white line, Ready, Set, GO!” were continually repeated.

Once the participant clearly understood the instructions, they would then complete five (5) single-task, comfortable walking trials (ST-CW). For the cognitive dual-tasks tests, participants performed five (5) trials, four (4) serial counting trials (DT(1,2,3,4)-SC), and one (1) dual-task multiplication trial (DT-MULT). They were instructed to walk and perform the cognitive task concurrently, prioritizing the walking task to avoid creating stop-and-go movements that might interfere with the markerless motion caption system. DT1-SC involved counting up in odd/even numbers, DT2-SC involved counting down in odd/even numbers, DT3-SC involved counting up in sets, and DT4-SC involved counting down in sets. In the dual-task multiplication condition (DT-MULT), participants were presented with a single-digit number and a single-digit multiplier. The dual-task instructions were presented immediately prior to each walking trial to ensure a cognitive load during the gait trial, as the cognitive task could not be practiced beforehand. Participants were instructed to immediately raise a hand in the air as if they had a question when they did not understand the dual-task instruction. As an example, one of the two options for DT1-SC was as follows: “Count in odd numbers starting from 1… (slight pause to allow the participant time to process and raise a hand if necessary) ready? Comfortable walking pace, all the way through the white line, Ready, Set, GO!” If the participant raised their hand for clarification, a second and possibly a third dual-task was assigned, ensuring that the participant could not practice the task in advance. Refer to Table 1 for the complete list of dual-task instructions and descriptions. Participants were allowed to count in the language that was most comfortable for them to complete the task (native or otherwise).

Table 1.

Dual-task list and instructions.

After data collection, spatiotemporal gait parameters were extracted from the built-in Advanced Overground Gait Analysis system in OpenCap. The analysis identifies the last viable right leg stride and computes the spatiotemporal parameters based on that stride alone. The following spatiotemporal gait parameters were extracted for each trial: walking speed (m/s), stride length (m), step width (cm), cadence (steps/min), and double support (% gait cycle). The five ST-CW trials for each participant were also used to evaluate reliability. These trials were collected under identical conditions, with no intervening tasks or recalibration between recordings, and were used to quantify the trial-to-trial consistency of spatiotemporal gait parameters derived from the OpenCap system. Furthermore, the mean of the five ST-CW trials served as the baseline comparator for the DT(1,2,3,4)-SC and DT5-MULT conditions.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

A priori power analysis using G Power (version 3.1.9.7) was conducted for a within-factors repeated measures ANOVA with six measurements (1 by 6), an effect size of 0.25 (medium), alpha = 0.05, desired power (beta) = 0.95, a correlation among repeated measures of 0.5, and no nonsphericity correction (ε = 0.55). The analysis indicated that a minimum total sample size of 43 participants would be required. With an actual sample size of 43 participants, the achieved power was ≥0.95, indicating that the study was sufficiently powered to detect within-subject differences across conditions [18].

Data was analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics are presented as mean (M) ± standard deviation (SD) and were computed for each variable. To quantify the within-session relative reliability of the OpenCap-derived spatiotemporal gait variables, we used the five ST-CW trials per participant. A two-way mixed-effects, single-measure, absolute-agreement intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC(3,1)) was used to assess relative reliability [19,20,21]. This model was selected because the same fixed system and procedures were used to measure all trials/participants, and the goal was to evaluate absolute agreement across five repeated measurements. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (95% CI) for ICCs were calculated using the F-distribution method. In addition, the average-measure (ICC (3,k)), where k = 5 trials, was used to estimate the reliability of the mean of five trials, representing the precision of the averaged data used in subsequent analyses [20,21]. Next, we quantified absolute reliability (precision) using the within-subject error from a repeated-measures general linear model (GLM). For each outcome, a GLM was fitted with five trials as a within-subject factor. The within-subject mean square error from this model (MSe) was used to compute the within-subject standard deviation as:

This represents the typical trial-to-trial variability for a single ST-CW trial in the original measurement units. In the reliability literature, this quantity is equivalent to the standard error of measurement (SEM) or “typical error” for a single measurement. However, for transparency, we also derived a manual SEM calculation from the classical ICC-based formula [22,23]. For each outcome, a pooled single-trial standard deviation was obtained by combining the five trial-wise SDs:

SEM for a single trial was then calculated as:

These SEM (1) values were used to compute the minimal detectable change (MDC) for a single trial at the 95% confidence level as:

MDC (1) represents the smallest between-session difference in two single-trial measurements that can be interpreted as real (exceeding measurement error). Because the primary analytical outcome was the mean of five ST-CW trials per participant, we also expressed precision for the averaged scores. The SEM for the 5-trial mean was calculated as:

The corresponding minimal detectable change for the 5-trial mean at the 95% confidence level (MDC (5)) was computed as:

A within-subjects repeated measures ANOVA was used to assess the effect of task condition on spatiotemporal gait parameters across six walking conditions: mean of five ST-CW, DT1-SC, DT2-SC, DT3-SC, DT4-SC, and DT5-MULT. Condition related differences in spatiotemporal parameters were interpreted in conjunction with the SEM and MDC values derived from the single-task reliability analysis, to distinguish changes that likely exceed measurement error. Mauchly’s test of sphericity was conducted, and violations were corrected using Greenhouse–Geisser adjustments. Post hoc comparisons with Bonferroni correction were performed where applicable. Significance was set at α = 0.05. Partial eta-squared (η2) was used to report effect sizes for the ANOVA repeated measures, which were interpreted as follows: small (η2 = 0.01), medium (η2 = 0.06), and large (η2 = 0.14) [24]. Cohen’s d was used for pairwise comparisons to estimate effect size, which was interpreted using Cohen’s definitions of small (0.2), medium (0.5), and large (0.8) effect sizes [25].

3. Results

In total, 500 walking trials were performed (50 participants × 10 trials), and 491 trials (98.2%) were successfully processed using the OpenCap gait analysis program. Nine trials (1.8%) failed to process due to technical errors (2 trials failed to upload, 7 trials failed to process overground gait analysis) and were therefore excluded from the statistical analysis. The nine failed trials affected data for a total of 7 participants; 1 trial/participant was excluded from the ST-CW data, and 8 trials for 6 participants from the DT data. This left complete data for 49 participants in the reliability analysis and 43 participants for the dual-task analysis. Participant baseline demographics are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Participant baseline demographics—presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Within-subject test–retest reliability across the five ST-CW trials demonstrated good to excellent relative reliability as represented in Table 3. ICC (3,1) ranged from 0.50 to 0.89, with the highest reliability observed for gait speed, stride length, and cadence. Step width exhibited good reliability, while double-support time showed moderate reliability. When the mean of all five ST-CW trials was analyzed, the average-measure ICC (3,5) values showed excellent reliability in gait speed, stride length, cadence, and step width; double-support time demonstrated good to excellent reliability.

Table 3.

Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for within-subject test–retest ST-CW trials.

Within-subject variability from the GLM (SD (within)) and manually derived SEM (1) values were virtually identical for all spatiotemporal variables, confirming consistency between the two absolute reliability approaches. For single trials, the corresponding MDC (1) values indicated that relatively modest changes in gait speed and stride length, but larger changes in step width, cadence, and double support, are required to exceed measurement error at the 95% confidence level. When outcomes were expressed as the mean of five trials, both SEM (5) and MDC (5) were markedly reduced for all variables, indicating a clear gain in measurement precision when multiple trials are utilized; this was especially evident for gait speed, stride length, and cadence, whereas step width and double support remained comparatively less precise but still benefited from multiple trials. Table 4 reports the calculations described in the methods section for each spatiotemporal variable’s absolute reliability.

Table 4.

Absolute reliability of spatiotemporal gait variables.

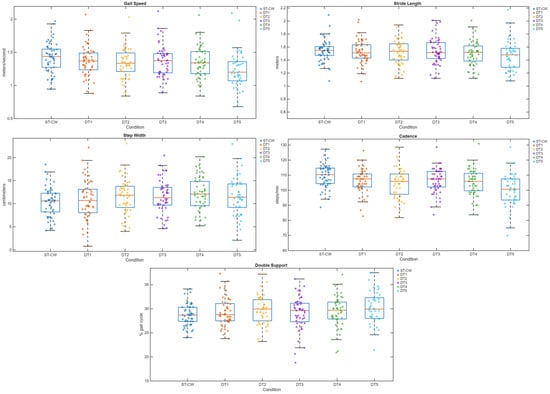

Descriptive statistics for the ANOVA analysis for gait parameters across the six task conditions are presented in Table 5 (n = 43). Gait speed was highest during ST-CW (1.42 ± 0.22 m/s) and lowest during DT5-MULT (1.24 ± 0.28 m/s). Stride length was longest during ST-CW (1.53 ± 0.17 m) and decreased progressively across dual-task conditions, with the shortest observed in DT5-MULT (1.45 ± 0.22 m). Step width increased under dual-task conditions, with ST-CW demonstrating the narrowest mean width (10.19 ± 3.31 cm) and DT4-SC the widest (12.00 ± 3.62 cm). Cadence followed a similar but negative pattern, being highest in ST-CW (109.99 ± 7.51 steps/min) and decreasing notably in DT5-MULT (101.13 ± 11.22 steps/min). Double support time was lowest during ST-CW (28.67 ± 2.35%) and increased slightly in the dual-task conditions, peaking during DT5-MULT (30.41 ± 3.41%). Figure 2 presents a visualization of the data with box and scatter plots for the five gait variables for all six conditions.

Table 5.

Descriptive data for variables by trial are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Figure 2.

Box and scatter plots for five gait variables by six trial conditions. Box and scatter plots of gait speed (m/s), stride length (m), step width (cm), cadence (steps/min), and double support (% gait cycle) for the average of five single-task walking conditions (ST-CW) and the five dual-task conditions (DT1–DT5). Boxes represent the interquartile range (25th–75th percentile), horizontal lines within boxes indicate the median, and whiskers extend to 1.5 × the interquartile range. Scatter points show individual observations for each condition, illustrating the distribution of participant-level data around the group mean.

The multivariate test revealed a significant main effect of task condition on the combined spatiotemporal gait parameters (Pillai’s Trace = 0.501, F(25, 1050) = 4.67, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.100; Wilks’ Lambda = 0.552, F(25, 767) = 5.31, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.112) indicating that task condition accounted for a substantial proportion of the variance in the multivariate outcome.

Mauchly’s test indicated that the assumption of sphericity was violated for all dependent variables: speed (W = 0.308, p < 0.001), step length (W = 0.370, p < 0.001), step width (W = 0.525, p = 0.028), cadence (W = 0.169, p < 0.001), and DS (W = 0.213, p < 0.001). Therefore, Greenhouse–Geisser corrections were applied to the univariate analyses. The univariate analyses showed that task condition had a significant effect on gait speed, F(3.34, 140.37) = 17.97, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.300; stride length, F(3.7, 155.25) = 8.03, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.161; step width, F(4.05, 170.18) = 7.51, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.152; cadence, F(3.28, 137.88) = 19.35, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.315; and DS, F(2.86, 119.97) = 4.96, p = 0.003, partial η2 = 0.106.

Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise comparisons showed that gait speed during ST-CW was significantly greater than during DT1-SC (p = 0.011), DT2-SC (p = 0.001), DT4-SC (p < 0.001), and DT5-MULT (p < 0.001), with no significant difference compared to DT3-SC (p = 0.053). Gait speed during DT5-MULT was significantly slower than all other trials. There was no significant difference in gait speed between all DT-SC trials. Furthermore, the stride length during ST-CW was significantly greater than during DT5-MULT (p = 0.002). Step width was significantly narrower during ST-CW than during DT2-SC (p = 0.002), DT3-SC (p < 0.001), DT4-SC (p = 0.002), and DT5-MULT (p < 0.001). Cadence during ST-CW was significantly greater than during DT1-SC (p = 0.002), DT2-SC (p < 0.001), DT3-SC (p < 0.001), DT4-SC (p < 0.001), and DT5-MULT (p < 0.001). Lastly, double support time during ST-CW was significantly less than during DT2-SC (p < 0.001) and DT5-MULT (p = 0.002).

To determine whether these condition-related differences exceeded measurement error, we compared the observed changes in mean spatiotemporal parameters with MDC(5) derived from the single-task reliability analysis (Table 4). For gait speed, the reduction from ST-CW (1.42 m/s) to DT5-MULT (1.24 m/s) was 0.18 m/s, which exceeds the MDC(5) of 0.091 m/s. Similarly, reductions in cadence from ST-CW (110.0 spm) to all DT conditions exceeded the MDC(5) of 3.48 spm. In contrast, increases in step width and double support between ST-CW and several DT conditions were of smaller magnitude and were closer to or below their respective MDC(5) values.

4. Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to establish a standardized protocol and procedures for 3D MMC-based gait analysis using OpenCap and to quantify the reliability and within-session precision of key spatiotemporal gait parameters obtained. By providing detailed documentation of our setup, including camera positioning, calibration procedures, participant alignment and preparation, and trial segmentation, we aimed to establish a replicable framework for future studies that utilize markerless technology in gait analysis, both within and outside laboratory settings.

OpenCap’s published best practices highlight key elements for ensuring high-quality data capture during overground trials, including maximizing camera field-of-view overlap, minimizing occlusion, providing stable and consistent camera placement, and performing thorough calibration across the capture volume [15]. In alignment with these recommendations, we positioned two iOS cameras laterally at a consistent height (80 cm) on stable tripods at a 27-degree angle off-centerline. This setup allowed participants to be within both camera views when they started the walking trials and remain in view until the end of the six-meter measurement area. In turn, the last viable stride captured was clearly within the measurement area, providing certainty that the stride was not taken during an acceleration or deceleration phase of the 10 m walkway, which aligns with the best practices of general 10 m walking tests [14].

In terms of calibration, our protocol adhered closely to OpenCap’s recommendations by using a rigid, matte-finish calibration board (the exact checkerboard available on OpenCap’s best practices website). The board was placed at the same location within the measurement area, aligned with a fixed floor marker to ensure reproducibility across trials and sessions. OpenCap emphasizes the importance of calibrating across the whole capture area and using high-contrast, non-reflective calibration tools, both of which were integral to our protocol. Additionally, our use of a standard neutral pose calibration positioned over the same fixed marker within the measurement area ensured accurate biomechanical model initialization, further reducing variability in spatiotemporal and kinematic data.

We specifically mounted the calibration checkerboard at or near the same height as the cameras (80 cm). Although the camera height in comparison to the calibration board height is not mentioned in OpenCap’s best practices, our preliminary trials before the study’s onset indicated a higher rate of failed gait analysis in the OpenCap software when the cameras were positioned higher than the calibration board, and vice versa. The authors of the current research believe that this is an important distinction that warrants further study to verify our assumptions.

Regarding lighting, OpenCaps’ best practices simply state “a well-lit environment with even lighting across the calibration board and capture space.” Theia 3D, an alternative MMC platform, has published a blog post suggesting a minimum of 500 lux and a standard of 1000 lux as best practice [26]. The lighting in our laboratory was measured across multiple sessions, with average illumination values consistently ranging from approximately 950 to 1080 lux, including the calibration board, camera zones, and walkway endpoints. Lighting uniformity was mostly satisfactory, with standard deviations between 9 and 40 lux in most zones; however, localized variability was observed at the calibration board (954 ± 125 lux) and the start of the walkway (872 ± 135 lux), suggesting minor inconsistencies in those regions possibly due to the laboratory having a half-vaulted ceiling (LED lighting further from measurement area) and multiple windows on the far west side (start of the walkway), which led to fluctuation in lighting depending upon the amount of sunlight coming in from the outside (owing to the time of day or cloudy/sunny conditions). Despite these variations, the overall mean illuminance was 963.8 ± 108.2 lux, indicating a well-lit environment that supports stable video capture. These results suggest that the laboratory’s fixed overhead LED lighting system provides a reliable illumination environment for markerless motion analysis. However, minor improvements in uniformity at specific locations may further enhance tracking accuracy. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, no scientific research has been conducted on this topic. It would be of great interest for future research to compare different lighting scenarios and determine the appropriate lighting ranges for 3D-MMC.

Beyond adhering to the best practices published on the OpenCap webpage [15], our study contributes further structure by formalizing trial segmentation (designating acceleration, measurement, and deceleration zones) and participant instructions to minimize inter-trial variability. A recent systematic review by Cheng et al. (2025) has highlighted that, among current computer vision-based motion capture systems, OpenCap holds the most promise for clinical gait analysis [4]. Additionally, the current detailed documentation and schematic (Figure 1) serve not only as a record of our protocol but also as a proposed template for researchers seeking to further standardize OpenCap gait analysis procedures.

OpenCap records video on iOS devices and uploads this data to a cloud-based server over Wi-Fi, where the spatiotemporal parameters are generated once the user selects the appropriate secondary processing option (overground or treadmill gait). In the present study, 500 normal and dual-task walking trials were recorded, of which 491 (98.2%) were successfully uploaded, processed, and passed our quality checks. Two trials (0.4%) failed at the upload stage, most likely due to unstable Wi-Fi in our laboratory location compared with other areas on campus. The remaining seven failed trials (1.4%) were successfully uploaded but failed to complete overground gait processing. We suspect that atypical movement-related events during these trials may have challenged the underlying tracking and segmentation algorithms. This cannot be confirmed because OpenCap does not currently provide detailed error diagnostics. We suggest that reporting such capture and processing metrics become standard in research using OpenCap, as it provides transparent information on data completeness, highlights potential procedural shortfalls, and offers a practical benchmark for the robustness of processing protocols.

Relative and absolute reliability analyses show that our standardized protocol and procedures for 3D MMC (OpenCap) yield good-to-excellent relative reliability and relatively small absolute errors for key spatiotemporal gait parameters. Single-measure ICC (3,1) values ranged from poor to excellent, and the corresponding ICC (3,5) coefficients for the mean of five ST-CW trials were predominantly excellent, indicating highly stable individual measurements under the proposed protocol. Gait speed, stride length, and cadence show good to excellent test–retest reliability for single measurements (ICC(3,1)). When averaged over five trials (ICC(3,5)), the relative reliability of the scores demonstrates even higher excellent ratings, with only DS reporting a good-excellent rating. This data should serve as a reminder to collect data across multiple trials when using 3D-MMC systems to improve measurement reliability.

The current data demonstrate that SD (within) and SEM (1) were nearly identical across all spatiotemporal outcomes, indicating that the variance components extracted from the repeated-measures GLM and the classical ICC-based SEM calculations shown in the methods section and presented in Table 4 capture the same underlying trial-to-trial error. This internal consistency supports the use of SD (within) as a straightforward GLM-derived precision metric and SEM and MDC as complementary, clinically interpretable indices of absolute reliability. These data also confirm that the trial-to-trial noise/variance in the OpenCap software is minimal when standardized procedures are used, and it achieves precision comparable to other validated gait technologies [1,22,23,27,28,29,30,31]. However, questions arise regarding the step width and DS variables, where the variance attributable to measurement error is much greater and should be interpreted with caution.

Furthermore, within classical test theory (Lord & Novick, 1968) and more recently noted by Borsboom & Mellenbergh (2022) [32,33], reliability is defined as the ratio of true-score variance to observed-score variance, such that the proportion of variance attributable to measurement error equals . In our case, the standard error of measurement (SEM) was computed as . It follows directly that , and thus represents the percentage of the observed variance that is due to measurement error. Using this approach, our single-trial OpenCap measurements suggest that measurement error accounts for 11.40% of the observed variance in gait speed, 12.4% in stride length, 21.7% in step width, 11.9% in cadence, and 50.3% in double support (DS). When the mean of five trials is used (), the proportion of variance attributable to measurement error is significantly reduced, to 2.28% for gait speed, 2.48% for stride length, 4.34% for step width, 2.38% for cadence, and 10.06% for DS. Equally, reliability for each variable can be expressed as . Essentially, coming back full circle, a 2.28% error variance for gait speed implies an ICC of approximately 0.975 when averaged over five trials, as reported in the ICC tables.

As a secondary objective, we used dual-task conditions to illustrate how the reliability estimates obtained under the standardized protocol can inform the interpretation of condition-related changes. When the DT data were examined in light of the MDC (5) values derived from the single-task reliability analysis, reductions in gait speed, stride length, and cadence between ST-CW and DT conditions consistently exceeded their respective MDC (5), indicating that these changes are unlikely to arise from measurement error alone. In contrast, increases in step width and double support were smaller relative to their MDC (5) values and therefore should be interpreted more cautiously. This is not surprising as most validity and reliability research to date has found that frontal plane variables demonstrate greater variance than criterion measures [1,2,4]. These findings demonstrate that, under a rigorously standardized 3D-MMC protocol, OpenCap is sufficiently precise to detect relatively small experimental manipulations at the group level, while also highlighting which gait variables are less suitable for detecting subtle changes.

Prior research has utilized serial counting in 3 s and/or 7 s, usually counting down, but not exclusively [34,35,36,37,38,39]. However, the authors developed the current DT protocols with the progression of complexity in mind. We approached the serial counting method by counting up (DT1-SC and DT3-SC), counting down (DT2-SC and DT4-SC), and multiplying (DT5-MULT); within that model, we asked the participants to count in different ways, such as odd or even numbers, in sets/groups, and multiplying with progressively larger numbers. Although the data is not explicitly presented here, there were no statistical differences in the dual-tasks questions within the same class (i.e., counting up in odd (DT1.1) or even numbers (DT1.2) or counting down in sets by 20 (DT4.1), 50 (DT4.2), or 100 (DT4.3)). In the current model, counting down appears to be more cognitively demanding than counting up, regardless of the number or pattern (odds vs. evens, 3 s vs. 7 s, etc.). The current data help support the argument that serial counting down in 3 s and/or 7 s is a functional cognitive DT test for detecting changes in spatiotemporal gait analysis in healthy young adults. However, future research should further examine this hypothesis to determine the hierarchical structure of serial-counting dual-task. A recently published paper by Almutari et al. attempted to answer a similar question using six different dual-tasks; yet, only two of those tasks involved serial counting, and the study found no significant differences between the six observed dual-tasks [38].

Importantly, our study design minimized methodological variability that might otherwise confound these results. Standardized trial instructions, consistent calibration procedures, and strict task delivery ensured that observed differences in gait were attributable to cognitive load rather than inconsistencies in data collection or participant understanding. This methodological rigor complements meta-analytic evidence that dual-task costs scale with cognitive task complexity [37]. The markerless motion capture’s sensitivity in detecting small changes in gait speed, stride length, and cadence, as demonstrated here, underscores its utility for advancing dual-task gait research, especially when standardization procedures are strictly followed.

Our results contribute to the growing body of evidence that even simple cognitive tasks, when performed concurrently, can significantly affect spatiotemporal gait parameters in healthy college-age adults, and this effect is not exclusive to an aging population. This work highlights the importance of establishing standardized protocols in dual-task gait analysis to facilitate comparisons across studies and populations. Future research should explore how different categories of cognitive tasks, as well as task prioritization strategies, further modulate gait, and how MMC systems can be optimized to support large-scale, multi-site investigations. The authors believe that baseline data should be collected in younger, healthy adult populations to standardize the baseline cost of cognitive dual-tasking, which can then be compared in aging and/or diseased populations.

The current study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, all reliability and dual-task analyses were conducted in a single laboratory session with a relatively homogeneous sample of healthy young adults; precision and dual-task effects may differ in heterogeneous or clinical populations and across different environments and settings. Second, reliability was established for one specific OpenCap configuration (two cameras, fixed distances, lighting, and overground walkway length), so the results should not be generalized to other MMC setups without additional validation and reliability testing. Third, we focused only on spatiotemporal variables; joint-level kinematics and gait variability measures were not evaluated here. Fourth, we did not include a criterion reference system, such as a marker-based 3D motion capture system or an instrumented walkway, for direct validation of OpenCap outputs. In contrast, several previous reviews (cited in the introduction) have compared markerless or wearable systems against such gold standards. Fifth, participants’ baseline cognitive capacity was not measured, and cognitive-task performance during walking was not quantified; therefore, the dual-task analyses presented here should be viewed primarily as an illustration of how to apply the reliability metrics rather than a definitive characterization of cognitive–motor interference. Finally, although averaging the five ST-CW trials improved precision, step width and double support remained less reliable, so conclusions based on these variables should be interpreted with caution.

Importantly, while our secondary DT analyses demonstrated the sensitivity of this protocol in detecting changes, the greater contribution lies in demonstrating how MMC technology can be applied rigorously in research and clinical settings. As the field moves toward broader adoption of MMC, further dialog is needed to standardize methodologies and ensure data comparability across laboratories and studies. This work aims to initiate this conversation and provide a foundation for future methodological discourse, ultimately leading to consensus within the research community.

Given the rapid emergence of MMC, such as OpenCap, the scientific community must engage in discussions about standardized data collection procedures and best practices. Establishing shared practices will ensure that data generated using this technology is valid, reliable, and comparable across laboratories. Although our analysis of dual-task gait changes provides insight into cognitive-motor interactions, it is secondary to our primary objective of advancing transparent, rigorous methods for gait data acquisition using this promising technology.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this paper establishes a standardized protocol for gait analysis using 3D-MMC (OpenCap), providing clear guidelines for camera setup, calibration, lighting, participant preparation, and trial segmentation to enhance methodological consistency across studies. Applying this protocol, we demonstrated that OpenCap yields good to excellent within-session reliability and relatively small MDCs for gait speed, stride length, and cadence. In contrast, step width and double support are less precise and should be interpreted with greater caution. As a secondary demonstration, we showed that, under this protocol, dual-task walking induces changes in several spatiotemporal parameters that clearly exceed measurement error, illustrating how ICC, SEM, and MDC estimates can be used to critique whether experimental or clinical differences are likely to be real. These findings support the use of our standardized OpenCap protocol for reliable spatiotemporal gait assessment and provide quantitative benchmarks for interpreting condition- or intervention-related changes in future studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.J.K.; methodology, C.J.K.; software, C.J.K.; validation, C.J.K.; formal analysis, C.J.K.; investigation, C.J.K., A.T., S.J.V. and M.V.; resources, C.J.K.; data curation, C.J.K., A.T., S.J.V. and M.V.; writing—original draft preparation, C.J.K. and M.V.; writing—review and editing, C.J.K., A.T., S.J.V. and M.V.; visualization, C.J.K.; supervision, C.J.K.; project administration, C.J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local Ethics Committee of Universidad Católica San Antonio de Murcia (protocol code TC/05-24).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request by contacting the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the students at UCAM University who participated in the research, helped recruit participants, and assisted with data collection when a helping hand was needed. We would especially like to thank the student members of the Movement Analysis Laboratory (MALab) research group who are not included as authors on this publication but have contributed in one way or another.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| MMC | Markerless motion capture |

| DT | Dual task |

| ST | Single task |

| MULT | Multiplication |

| CW | Comfortable walking |

| SC | Serial counting |

| DS | Double support |

| ICC | Intra-class correlation |

| MSe | Mean square error |

| SEM | Standard error of measurement |

| MDC | Minimal detectable change |

References

- Scataglini, S.; Abts, E.; Van Bocxlaer, C.; Van den Bussche, M.; Meletani, S.; Truijen, S. Accuracy, Validity, and Reliability of Markerless Camera-Based 3D Motion Capture Systems versus Marker-Based 3D Motion Capture Systems in Gait Analysis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sensors 2024, 24, 3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, W.W.T.; Tang, Y.M.; Fong, K.N.K. A systematic review of the applications of markerless motion capture (MMC) technology for clinical measurement in rehabilitation. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2023, 20, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Washabaugh, E.P.; Shanmugam, T.A.; Ranganathan, R.; Krishnan, C. Comparing the accuracy of open-source pose estimation methods for measuring gait kinematics. Gait Posture 2022, 97, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, X.; Jiao, Y.; Meiring, R.M.; Sheng, B.; Zhang, Y. Reliability and validity of current computer vision based motion capture systems in gait analysis: A systematic review. Gait Posture 2025, 120, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanko, R.M.; Laende, E.K.; Strutzenberger, G.; Brown, M.; Selbie, W.S.; DePaul, V.; Scott, S.H.; Deluzio, K.J. Assessment of spatiotemporal gait parameters using a deep learning algorithm-based markerless motion capture system. J. Biomech. 2021, 122, 110414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyasingh-Jacob, J.; Crook-Rumsey, M.; Shah, H.; Joseph, T.; Abulikemu, S.; Daniels, S.; Sharp, D.J.; Haar, S. Markerless Motion Capture to Quantify Functional Performance in Neurodegeneration: Systematic Review. JMIR Aging 2024, 7, e52582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çabuk, S.; Ulupınar, S.; İnce, İ.; Özbay, S. Can OpenCap deliver valid and reliable kinematic data for motion analysis? A systematic review and three-level meta-analysis. Biol. Sport 2026, 43, 555–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kaid, A.; Baïna, K. A Systematic Review of Recent Deep Learning Approaches for 3D Human Pose Estimation. J. Imaging 2023, 9, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, K.; Guzman, K.S.-M.; Peoples, B.M.; Campos-Vargas, S.; Smith, B.R.; Cifuentes, D.C.; Greer, G.; Neely, K.A.; Roper, J.A. Verbal Fluency Dual-Tasks Show Greater Age-Related Cognitive-Motor Interference: A Meta-Analysis of Walking Performance. Exp. Brain Res. 2025, 243, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzman, T.; Laurin, E.; Thibault, C.; Farrell, P.; Fraser, S. A systematic review and meta-analysis of dual-task outcomes in subjective cognitive decline. Alzheimer’s Dement. Diagn. Assess. Dis. Monit. 2025, 17, e70054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, A.; McGuckian, T.B.; Steenbergen, B.; Cole, M.H.; Wilson, P.H. How Reliable and Valid are Dual-Task Cost Metrics? A Meta-analysis of Locomotor-Cognitive Dual-Task Paradigms. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2023, 104, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishnoi, A.; Hernandez, M.E. Dual task walking costs in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Ment. Health 2021, 25, 1618–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beauchet, O.; Annweiler, C.; Dubost, V.; Allali, G.; Kressig, R.W.; Bridenbaugh, S.; Berrut, G.; Assal, F.; Herrmann, F.R. Stops walking when talking: A predictor of falls in older adults? Eur. J. Neurol. 2009, 16, 786–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, A.; Fritz, S.L.; Lusardi, M. Walking Speed: The Functional Vital Sign. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2015, 23, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delp, S.L. OpenCap Best Practices. 2024. Available online: https://www.opencap.ai/best-practices (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Uhlrich, S.D.; Falisse, A.; Kidziński, Ł.; Muccini, J.; Ko, M.; Chaudhari, A.S.; Hicks, J.L.; Delp, S.L. OpenCap: Human movement dynamics from smartphone videos. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2023, 19, e1011462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The European Committee for Standardization (CEN). Light and Lighting—Lighting of Work Places—Part 1: Indoor Work Places; The European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P.E.; Fleiss, J.L. Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol. Bull. 1979, 86, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGraw, K.O.; Wong, S.P. “Forming inferences about some intraclass correlations coefficients”: Correction. Psychol. Methods 1996, 1, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, G.; Nevill, A.M. Statistical Methods For Assessing Measurement Error (Reliability) in Variables Relevant to Sports Medicine. Sport. Med. 1998, 26, 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, W.G. Measures of Reliability in Sports Medicine and Science. Sport. Med. 2000, 30, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakens, D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: A practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Characteristics of Video Data for New Users Pt. 2—Lighting. 2024. Available online: https://www.theiamarkerless.com/blog/characteristics-of-video-data-for-new-users-pt-2-lighting (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Weir, J.P. Quantifying test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient and the SEM. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2005, 19, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobsar, D.; Charlton, J.M.; Tse, C.T.F.; Esculier, J.-F.; Graffos, A.; Krowchuk, N.M.; Thatcher, D.; Hunt, M.A. Validity and reliability of wearable inertial sensors in healthy adult walking: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2020, 17, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riazati, S.; McGuirk, T.E.; Perry, E.S.; Sihanath, W.B.; Patten, C. Absolute Reliability of Gait Parameters Acquired With Markerless Motion Capture in Living Domains. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 867474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Pinillos, F.; Jaén-Carrillo, D.; Soto Hermoso, V.; Latorre Román, P.; Delgado, P.; Martinez, C.; Carton, A.; Roche Seruendo, L. Agreement Between Spatiotemporal Gait Parameters Measured by a Markerless Motion Capture System and Two Reference Systems—A Treadmill-Based Photoelectric Cell and High-Speed Video Analyses: Comparative Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e19498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochman, M.T.; Kielar, A.; Kasprzak, M.; Kasperek, W.; Dutko, M.; Vellender, A.; Przysada, G.; Drużbicki, M. A Reliability Study of Small, Portable, Easy-to-Use, and IMU-Based Sensors for Gait Assessment. Sensors 2025, 25, 6597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, F.M.; Novick, M.R.; Birnbaum, A. Statistical Theories of Mental Test Scores; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Borsboom, D.; Mellenbergh, G.J. True scores, latent variables, and constructs. Intelligence 2002, 30, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, S.; Giladi, N.; Peretz, C.; Yogev, G.; Simon, E.S.; Hausdorff, J.M. Dual-tasking effects on gait variability: The role of aging, falls, and executive function. Mov. Disord. 2006, 21, 950–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedović, N.; Mutavdžin Krneta, S.; Jovanović, S.; Vujičić, D.; Kozinc, Ž.; Skvortsov, D. Dual-Task Gait Analysis: Combined Cognitive–Motor Demands Most Severely Impact Walking Patterns and Joint Kinematics. Life 2025, 15, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asai, T.; Doi, T.; Hirata, S.; Ando, H. Dual tasking affects lateral trunk control in healthy younger and older adults. Gait Posture 2013, 38, 830–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, H.-T.; Pearce, M.; Vas, A. Task matters: An investigation on the effect of different secondary tasks on dual-task gait in older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, J.S.; Alshewier, S.A.; Alkathiry, A.A. Ranking the difficulty of the cognitive tasks in Dual-Tasks during walking in healthy adults. Neurosciences 2025, 30, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristow, T.; Jih, C.-S.; Slabich, A.; Gunn, J. Standardization and adult norms for the sequential subtracting tasks of serial 3’s and 7’s. Appl. Neuropsychol. Adult 2016, 23, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).