Abstract

This work deals with the comparative analysis of fluoride coatings, i.e., 5 wt.% AlF3 and LiF, applied as surface layer of Li-rich Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 (LNCM) layered oxides synthesized via facile and cost-effective sol–gel route. The detailed structural and morphological characterizations demonstrate that AlF3 and LiF deposits have a pivotal role in enhancing the electrochemical properties of LNCM. These electrochemical properties include galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD), differential capacity (dQ/dV), electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), and area-specific impedance (ASI). A much lower decay of the discharge capacity of 0.22 and 0.25 mAh g−1 per cycle was obtained for AlF3- and LiF-coated LMNC, respectively, after 100 charge/discharge cycles at 0.1 C compared with 0.42 mAh g−1 per cycle for pristine LNCM. Results evidence the non-evolution of the charge transfer resistance, enhanced lithium-ion kinetics and stabilization of electrode/electrolyte interface during cycling.

1. Introduction

Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) and lithium-metal batteries (LMBs) have emerged as promising alternatives to conventional combustion engines, offering a means to reduce fossil fuel consumption and mitigate global warming. These battery technologies are being developed primarily for electric vehicles (EVs) and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs), as well as for various portable electronic applications such as smartphones and laptops [1]. LIBs possess several advantageous properties, including high operating voltage, excellent energy density, large specific capacity, and the absence of a memory effect [2].

Currently, widely used cathode materials—such as olivine-type LiFePO4, spinel-type LiMn2O4, and layered oxides including LiCoO2, LiNi1−y−zCoyMnzO2, and LiNi0.8Co0.15Al0.05O2—typically exhibit specific capacities below 200 mAh g−1. These values fall short of meeting the energy and power density requirements for next-generation EVs [3]. This limitation has motivated the exploration of lithium-rich layered oxide cathodes with the general formula yLi2MnO3∙(1 − y)LiMO2 (0 < y < 1, M = Mn, Co, Ni, Cr, Fe, Ni1/2Mn1/2, Ni1/3Co1/3Mn1/3, etc.). These materials can be described as atomic-scale intergrowths of rhombohedral LiMO2 phase (R-3m space group) with the monoclinic Li2MnO3 phase (C2/m space group, Li[Li1/3Mn2/3]O2 in layered notation). Owing to their structural integration and chemical tunability, these compounds are regarded as cost-effective and high-performance cathode candidates, capable of delivering specific capacities exceeding 250 mAh g−1 and energy densities approaching 1000 Wh kg−1 [4]. These exceptional properties originate from the activation of the Li2MnO3 component at high operating voltages [5].

Among these materials, the lithium-rich manganese-based cathode Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 (LNCM, 0.5Li2MnO3·0.5LiNi1/3Co1/3Mn1/3O2 in the two-component notation) demonstrates excellent electronic conductivity, robust structural stability, high discharge capacity, moderate cycling performance, and favorable rate capability. These attributes arise from the synergistic interaction between the Li2MnO3 and LiNi1/3Co1/3Mn1/3O2 components, as well as the beneficial presence of Co ions [6].

However, a major drawback of this material is the substantial irreversible capacity loss during the first cycle, leading to a low initial Coulombic efficiency (CE). This phenomenon is primarily attributed to oxygen anion oxidation and Li2O evolution, which generate oxygen vacancies at high states of charge. As a consequence, transition metal (TM) cations migrate from the TM layers into vacant Li sites via tetrahedral intermediates to maintain structural equilibrium. The resulting cation disorder hinders lithium reinsertion during discharge, reducing the reversible capacity. Continuous TM migration further accelerates voltage and capacity fading by inducing phase transitions from the layered structure to spinel and rock-salt phases [7]. Additionally, surface structural reconstruction increases interfacial resistance, while electrolyte oxidation at high voltages leads to the formation of a passivation layer—known as the cathode–electrolyte interphase (CEI)—on the particle surface. This CEI layer impedes Li+ diffusion kinetics, thereby degrading rate capability and overall electrochemical performance [8].

Several strategies have been proposed to address the aforementioned challenges, including (i) partial substitution of cations or oxygen anions (doping) [9,10], (ii) the use of electrolyte additives [11], and (iii) surface coating or surface modification [12]. To date, surface modification has been widely explored using various coating materials such as metal oxides (TiO2, Al2O3, SnO2, WO3, etc.) [13,14,15], metal phosphates (Li3PO4, AlPO4) [16,17], vanadates (Li3VO4) [18], and titanates [19]. In particular, extensive research efforts have focused on coating Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 with metal fluorides to enhance its electrochemical stability and performance, e.g., AlF3 [20,21,22,23,24,25,26], CaF2 [27,28,29], CeF3 [30], LiF [31,32], MgF2 [33], NaF [34], YF3 [35,36], SmF3 [37], FeF3 [38]. These coatings have attracted significant attention owing to their high chemical stability, strong electronegativity, and wide electrochemical stability window. They act as robust protective layers that mitigate parasitic reactions between the cathode surface and the electrolyte, effectively suppressing electrolyte decomposition and oxygen release at high voltages. Moreover, fluoride coatings reduce transition metal dissolution and migration by maintaining the structural integrity of the cathode during repeated cycling. The formation of a uniform and ionically conductive interfacial layer facilitates stable Li+ transport while minimizing impedance growth. Consequently, coated Li-rich layered oxides exhibit improved initial Coulombic efficiency, enhanced rate capability, and superior long-term cycling stability compared to their uncoated counterparts.

However, a comprehensive characterization of these composites—specifically, the correlation among their structural, morphological, and electrochemical properties (including charge–discharge behavior, impedance response, and kinetic characteristics)—remains insufficiently explored. Liu et al. [28] reported that the capacity retention (CR) of Li1.2Mn0.54Ni0.13Co0.13O2 increased to 91.2% at 0.2 C after 80 cycles following surface modification with CaF2. Sun et al. [33] demonstrated that MgF2 coating enhanced the CR to 86%, compared with 66% for the pristine material after 50 cycles. Abdel-Ghany et al. [39] deposited an AlF3 coating on Li1.2Ni0.2Mn0.6O2 nanoparticles, achieving a discharge capacity of approximately 250 mAh g−1 over 55 cycles at a rate of 0.1 C. Furthermore, Ding et al. [34] investigated the in situ formation of LiF surface decoration on Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2, which exhibited an enhanced CR of 93% after 1000 cycles at a high current rate of 10 C.

Metal fluorides—particularly AlF3 and LiF—have been widely recognized as effective protective coating layers due to their favorable physicochemical properties for energy storage applications. Aluminum is a lightweight, abundant, and cost-effective element, and the Al3+ ion is electrochemically inert, remaining stable under typical battery operating conditions [40]. LiF, on the other hand, contributes to interfacial stability by isolating the active material from the electrolyte and suppressing undesirable side reactions [32]. Both AlF3 and LiF serve additional functions as buffer layers: they effectively protect the aluminum current collector from corrosion induced by conventional LiPF6-based electrolytes, act as HF scavengers, and mitigate (i) the dissolution of active materials, (ii) the disproportionation of Mn3+, and (iii) the phase transformation from layered to spinel structures [41].

Based on the above considerations, the novelty of the present study lies in a comparative analysis of two fluoride-based surface modification layers—5 wt.% AlF3 and LiF—applied to enhance the electrochemical performance of Li-rich Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 layered oxides synthesized via the same green sol–gel route. Comprehensive microscopic and structural characterizations were conducted to gain an in-depth understanding of the modified nanoparticles using X-ray diffraction (XRD) coupled with Rietveld refinement, Raman scattering (RS) spectroscopy, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX), Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area analysis, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM). Electrochemical performance was evaluated through galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD) cycling, differential capacity (dQ/dV) analysis, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), and area-specific impedance (ASI) measurements. The results demonstrate that the AlF3 and LiF coating layers play a crucial role in improving the electrochemical behavior of Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2. This is achieved by suppressing the evolution of charge-transfer resistance, enhancing the lithium-ion kinetics, and stabilizing the electrode/electrolyte interface during cycling.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials Synthesis

Li-rich layered Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 powders were prepared by green synthesis, i.e., sol–gel method (SGM) assisted by citric acid as chelate [42]. The precursor was fabricated using acetate salts and citric acid as a chelating agent. Stoichiometric amounts of CH3COOLi∙2H2O, Ni(CH3COO)2∙4H2O, Co(CH3COO)2∙4H2O and Mn(CH3COO)2∙4H2O (analytical grade, 99.99%, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) were used as starting materials for all samples. The stoichiometric amounts were mixed together and were then dissolved in deionized water by stirring for 1 h. An excess of 7 mol.% Li was employed to account for potential mechanical and volatilization losses during subsequent transportation and calcination. The molar ratio of the chelating agent (citric acid) to the total metal ions was adjusted to unity and then added step-by-step wisely into the stirred aqueous solution of all the metal cations at a well-defined pH concentration and temperature. The pH of the solution was adjusted at ≈7 using an alkaline solution of ammonium hydroxide maintained at the temperature of 80 °C. Subsequently, the prepared solution was stirred using magnetic stirring to evaporate until a viscous transparent gel was obtained. With further evaporation, the gel transforms into a xerogel. Next, the obtained xerogel was dried in oven at 120 °C for 12 h. The resulting precursors calcined at 450 °C for 5 h, and then ground and recalcined at 800 °C for 20 h in air with intermittent grinding to obtain the final products. Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 is hereafter referred to as LNCM.

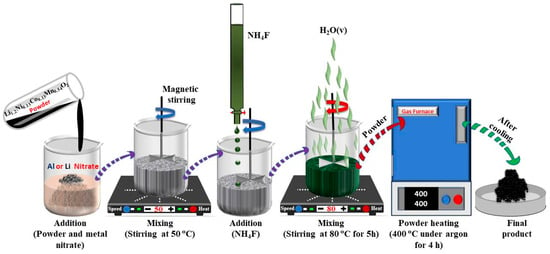

The AlF3 or LiF-coating layer was fabricated using a chemical deposition method as illustrated in Figure 1. The as-prepared Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 powders were immersed in a diluted aqueous solution of Al(NO3)3 or LiNO3, heated to 50 °C, and vigorously stirred. A dilute NH4F solution was then added dropwise. The molar ratio of Al to F and Li to F was controlled to be 1:3 and 1:1 for AlF3 and LiF, respectively, corresponding to the 5 wt.% coatings of AlF3 or LiF. The mixed solution was stirred at 80 °C for 5 h, followed by drying at 60 °C in a vacuum oven. The obtained powders were then heated at 400 °C in an Ar atmosphere for 4 h to prevent the formation of Al2O3 and ensure the successful formation of coatings. AlF3- and LiF-coated Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 are hereafter referred as LNCM/A and LNCM/L, respectively.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the AlF3/LiF coating process of Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 nanoparticles.

2.2. Materials Characterization

The phase and structure of the final product was analyzed by XRD using Philips X’Pert apparatus (Shenzhen, China) equipped with a CuKα X-ray source (λ = 1.54056 Å). Data were collected in the 2θ range 10°–80° at a step of 0.05°. The obtained XRD patterns were refined using the FULLPROF software (Toolbar Fullprof suit program (3.00), version June-2015) [43]. The surface morphology and composition of the fabricated samples were investigated by scanning electron microscopy Zeiss model Ultra 55, equipped with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDX, Shenzhen, China). HRTEM images were obtained using an electronic microscope JEOL model JEM-2010 (Akishima, Japan). The Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area and pore size distribution of synthesized samples were determined from N2-adsorption experiments using (Belsorp max version 2.3.2). The BET surface area was determined from adsorption isotherms in the relative pressure range of 0.02–0.4 (P/P0). Raman spectra were acquired using a micro-Raman spectrophotometer (Horiba, Singapore) equipped with an optical microscope. Measurements were performed with a 633 nm He–Ne laser excitation line, recorded at a spectral resolution of 1.6 cm−1 and an acquisition time of 30 s. A 100× microscope objective was used to focus the laser beam and collect the scattered light, resulting in a laser spot size of approximately 1 μm in diameter. To prevent photo-decomposition of the samples, a low excitation power density of 100 W cm−2 was employed. The wavenumber calibration was routinely verified using the characteristic Raman peak of silicon at 520 cm−1 as a reference. Electrochemical measurements were carried out using CR2025-type coin cells. The cathode slurry was prepared by mixing 80 wt.% active material, 10 wt.% carbon black (conductive agent), and 10 wt.% poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) binder in N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) solvent until a homogeneous mixture was obtained. The resulting slurry was uniformly coated onto an aluminum foil current collector and dried at 80 °C for 2 h to remove residual solvent, followed by pressing. Electrode films were then punched into 10 mm-diameter disks and further dried under vacuum at 80 °C for 12 h. The typical cathode loading was approximately 2 mg cm−2. The cells were assembled in an argon-filled glove box (H2O and O2 ≤ 5 ppm) using lithium metal as the counter electrode, a Celgard 2500 or 2300 separator, and an electrolyte consisting of 1 mol L−1 LiPF6 dissolved in a 1:1 (v/v) mixture of ethylene carbonate (EC) and dimethyl carbonate (DMC) (LP30, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Galvanostatic charge–discharge tests were conducted using a potentiostat/galvanostat (VMP3, Bio-Logic, Seyssinet-Pariset, France) within the potential range of 2.0–4.8 V.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Structure and Composition

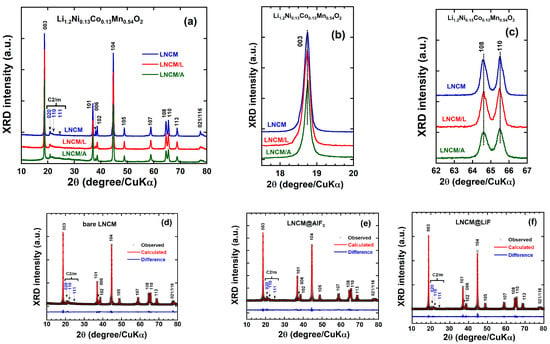

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns with indexed Miller planes of pristine Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 and surface-modified samples with 5 wt.% AlF3 and 5 wt.% LiF are presented in Figure 2a. The diffractograms indicate that the synthesized materials consist of two coexisting layered phases: a high-symmetry rhombohedral phase corresponding to LiNi1/3Mn1/3Co1/3O2 and a low-symmetry monoclinic phase corresponding to Li2MnO3. The major diffraction peaks can be assigned to the rhombohedral phase with space group R-3m (JCPDS card No. 50-0653) [44]. Based on the α-NaFeO2 prototype structure, the principal reflections of the as-prepared samples are characteristic of the O3-type layered LiNi1/3Mn1/3Co1/3O2 oxide [45]. Additional weak peaks observed between 20° and 25°, indexed as (020), (110), and (111), are mainly attributed to the monoclinic Li2MnO3 phase with space group C2/m (JCPDS card No. 84-1634) [46]. The emergence of this monoclinic phase may originate from short-range Li–Mn ordering in the transition-metal layers, where lithium ions partially occupy transition-metal sites [27]. The presence of Li2MnO3 will be further confirmed by Raman spectroscopy, which is particularly effective in probing local structural order, as discussed in the following section. For the fluoride-coated oxides (AlF3- or LiF-modified), no shift in the main diffraction peaks is observed (Figure 2a), indicating that no additional crystalline phases were formed during the surface modification process. The enlarged XRD pattern of the (003) reflection (Figure 2b) reveals that the surface coating does not alter the (003) d-spacing relative to the pristine LNCM bulk. This observation indicates that Al, Li, or F atoms do not diffuse into the bulk lattice and that the coating treatment preserves the structural integrity of the Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 core.

Figure 2.

(a) XRD patterns of LNCM, LNCM/A and LNCM/L samples recorded using a CuKα source (λ = 1.5406 Å), (b) magnified peak of (003), (c) magnified splitting peaks of (018)/(110) and (d–f) Rietveld refinement results.

Moderate-temperature annealing, typically at 400 °C under an argon atmosphere, is widely employed for the preparation of fluoride-coated LNCM materials. For instance, Sun et al. [20] synthesized AlF3-coated Li-rich oxides by heating the samples at 400 °C for 5 h under flowing nitrogen. Using a similar protocol, Zheng et al. [22] combined S/TEM and EELS analyses to elucidate the functional mechanism of the AlF3 coating. Their results show that the surface layer consists of AlOxFγ species formed during the wet-chemical coating step followed by thermal treatment. The lithiation of the AlOxFγ layer is believed to facilitate rapid Li-ion transport across the surface, thereby reducing electrode polarization and mitigating CEI formation.

The absence of distinct fluorine-related crystalline phases in the XRD patterns (Figure 2) is characteristic of conformal LiF and AlF3 coatings, which are typically thin (5–15 nm), amorphous, and confined to the particle surface. This observation is consistent with TEM-EDS analyses reported for similar systems, where nanoscale amorphous coatings effectively modify the surface chemistry without generating detectable XRD reflections [47,48,49]. This confirms that the coating functionality arises from surface-chemistry modification rather than bulk lattice incorporation. The stability and surface confinement of the coating in our system can be attributed to the low loading (5 wt.%) and the intrinsically poor crystallinity of the AlF3 and LiF layers [23]. The beneficial role of the coating becomes evident after high-temperature annealing at 400 °C in argon—conditions that typically promote oxygen loss and structural degradation in layered oxides. Remarkably, all coated samples retain a clear splitting of the (006)/(012) and (108)/(110) peak pairs (Figure 2c), indicative of a well-ordered hexagonal structure and the absence of spinel-like features, which are widely recognized as signatures of oxygen-loss-induced degradation [10,50,51,52].

To gain deeper insight into the structural effects of the surface coating on the Li-rich cathode material, Rietveld refinements were performed using the (Toolbar Fullprof suit program (3.00), version June-2015) [43]. FullProf Suite software. The full XRD patterns were refined based on a hexagonal structure with space group R-3m, where the Mn and Co occupancies were fixed while the Ni occupancies on both the transition-metal and lithium sites were allowed to vary. The Rietveld refinement results for the pristine and coated LNCM samples are presented in Figure 2d–f, and the corresponding refinement parameters are summarized in Table 1. As shown in these figures, the calculated and experimental XRD patterns exhibit excellent agreement, with minimal differences between the observed and refined profiles. The refinement parameters (characterized by low Rp, Rwp, and χ2 values) confirm the high quality of the fits and indicate that the Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 materials can be represented by the composite formula yLi2MnO3·(1 − y)LiNi1/3Mn1/3Co1/3O2, with y = 0.5. The refined lattice parameters (a = 2.8512(0) Å and c = 14.2428(4) Å) are nearly identical for all samples and are consistent with values previously reported in the literature, within an accuracy of 0.07% [46].

Table 1.

Results of Rietveld refinements of XRD patterns of LNCM, LNCM/A and LNCM/L.

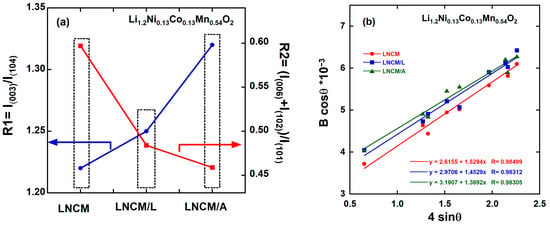

Additionally, several structural indicators can be used to evaluate the extent of cation mixing and the degree of hexagonal ordering (Table 1). First, the relative intensity ratio R1 = I(003)/I(104) is commonly used as a benchmark for assessing cation disorder in layered cathode materials with the α-NaFeO2-type structure. This disorder arises mainly from the partial occupation of Li+ sites (3a) by Ni2+ ions due to their similar ionic radii [53,54]. The I(003)/I(104) ratio increases from 1.22 for pristine LNCM to 1.25 for LNCM/L and 1.32 for LNCM/A, all exceeding the threshold value of 1.2, indicating reduced cation mixing. Second, the R2 factor, defined as (I(006) + I(102))/I(101), decreases from 0.579 (LNCM) to 0.484 (LNCM/L) and 0.459 (LNCM/A), all below 0.5. The combination of a higher R1 and lower R2 in the coated samples—particularly for LNCM/A—suggests a more well-defined hexagonal close-packed structure and a reduced degree of Li/Ni disorder compared to the pristine sample (Figure 3a) [55]. Furthermore, the ratio c/a, an indicator of hexagonal ordering, slightly increases from 4.990 (LNCM) to 4.991 (LNCM/L) and 4.995 (LNCM/A), confirming the enhanced structural ordering of the coated materials [56,57]. The observed increase in the c/a ratio reflects a well-defined hexagonal layered structure, providing wider diffusion channels that facilitate Li+ transport between oxygen layers during the lithiation/delithiation process, thereby enhancing the electrochemical performance [58,59]. This is further supported by the reduced occupancy of Ni2+ ions in the Li layers, as determined from Rietveld refinement (Table 1), which decreases from 1.68% for LNCM to 1.55% for LNCM/L and 1.43% for LNCM/A. This quantitative reduction in Ni antisite defects provides unequivocal evidence that cation mixing is suppressed in the coated samples. These results collectively confirm that the coated oxides possess a more ordered layered structure with a lower degree of cation mixing.

Figure 3.

(a) Variation in R1 and R2 factors (b) Analysis of the micro-strain <ε> from the full-width B at half-maximum of the XRD peaks using Equation (1) for LNCM, LNCM/A and LNCM/L.

The broadening of the XRD reflections was also analyzed to evaluate the strain field intensity and the associated structural disorder, following the Williamson–Hall relationship [60]:

where Bhkl is the line broadening of a Bragg reflection (hkl), K is the crystallite shape factor (assumed to be 0.9), ε is the micro-strain field, Lc is the effective crystallite size (coherence length), θ is the diffraction angle and λ is the X-ray wavelength. The plots exhibit excellent linearity, consistent with Equation (1). The microstrain (ε) was determined from the slope of the βcos θ versus 4sin θ plot (Figure 3b), while the intercept on the vertical axis provided the crystallite size. The results indicate that all three samples exhibit nearly identical crystallite sizes (Lc) within the range of 42.3–51.1 nm (average 46.7 ± 4.4 nm), suggesting that the pristine LNCM framework remains structurally intact after surface modification with LiF or AlF3. Moreover, the microstrain decreases slightly from 0.39 × 10−3 for pristine LNCM to 0.36 × 10−3 and 0.34 × 10−3 for LNCM/L and LNCM/A, respectively. This reduction in strain reflects improved structural stability in the coated samples, consistent with the lattice parameter trends and the influence of ionic radii discussed above.

Bhkl cos θhkl = (Kλ/Lc) + 4 ε sin θhkl,

This body of evidence resolves the apparent contradiction associated with the annealing conditions. In Li-rich layered oxides, the principal risk during inert-atmosphere annealing is the oxidation and subsequent loss of lattice oxygen (O2− → ½O2 + 2e−) [61,62]. Although the released electrons may provide local charge compensation, the more critical consequence is the disruption of the transition-metal coordination environment. Oxygen loss generates under-coordinated and thermodynamically unstable transition-metal cations at the surface, which readily migrate into neighboring Li layers, thereby markedly increasing cation mixing [63]. We propose that the amorphous fluoride coating functions as a sacrificial barrier that kinetically suppresses the outward diffusion of oxygen gas (O2) from the particle surface [48,64]. Owing to its dense and conformal nature, the amorphous fluoride layer forms a physical diffusion barrier that impedes O2 molecular transport while remaining permeable to Li+, thereby sustaining a higher local oxygen chemical potential at the cathode–coating interface [48,64]. This kinetic stabilization—rather than any thermodynamic modification of the bulk lattice—prevents oxygen evolution under conditions where it would otherwise be thermally activated. By preserving the surface oxygen sublattice, the coating suppresses the formation of under-coordinated transition-metal sites that serve as nucleation points for cation migration [63]. As a result, the thermal energy supplied during annealing is redirected away from oxygen-release-driven surface degradation and instead promotes beneficial thermally assisted reconstruction and ordering of the existing cation lattice. This surface-governed protection mechanism, achieved without bulk F incorporation, explains the markedly improved structural order observed across all XRD metrics [65].

3.2. Morphological Characterization

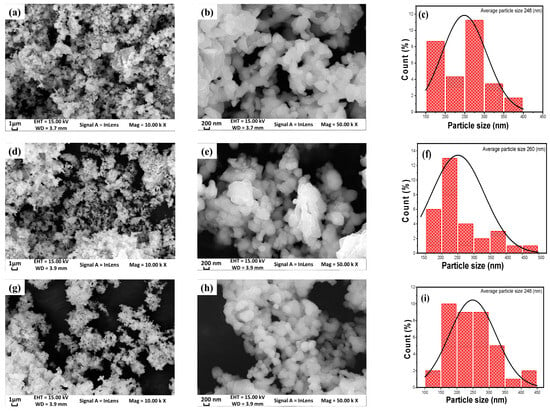

The surface morphology of the samples was examined using SEM, TEM, and HRTEM imaging. Figure 4 and Figure 5 display the SEM micrographs at two different magnifications, along with the corresponding EDX spectra for LNCM, LNCM/A, and LNCM/L powders. The SEM images reveal homogeneous, uniformly distributed, and nearly spherical grains with smooth and clean surfaces. The micrographs also show interparticle voids, which facilitate the diffusion of ions and the transport of electrons within the electrode material [66,67,68]. It has been reported that spherical particle morphology contributes to a high tap density, thereby enhancing the volumetric and gravimetric energy densities, improving powder flowability and dispersibility, and enabling the formation of a dense, uniform electrode layer [69].

Figure 4.

Morphology of LNCM (a–c), LNCM/A (d–f), and LNCM/L (g–i) samples. SEM images at magnifications of 10 k (a,d,g) and 50 k (b,e,h). Fitted particle size distribution (c,f,i).

Figure 5.

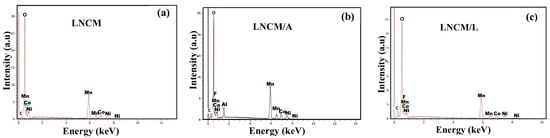

EDX spectra of (a) pristine LNCM, (b) LNCM/A and (c) LNCM/L.

The particle size distributions presented in Figure 4c,f,i show average particle sizes of approximately 248 nm, 260 nm, and 248 nm for LNCM, LNCM/A, and LNCM/L, respectively. The AlF3- and LiF-coated materials exhibit morphologies and particle size distributions nearly identical to those of the pristine LNCM sample, indicating that the coating process does not significantly alter the nanoscale morphology of the LNCM particles [12,70]. This observation suggests that the AlF3 and LiF coatings are uniformly distributed and ultrathin on the particle surfaces. The slight increase in particle size observed for LNCM/A may be attributed to partial agglomeration, which is reasonable considering that the coating thickness is only about 5–7 nm—negligible relative to the particle diameter (~250 nm)—and the coating temperature (≤400 °C) is well below the threshold for particle coalescence.

EDX analyses were performed on multiple regions of the prepared samples to determine their chemical composition and evaluate the homogeneity of the metallic cations, as well as their corresponding atomic percentages. The relative peak intensities reflect the elemental proportions present in the materials. As shown in Figure 5, the EDX spectra of the coated oxides display additional peaks corresponding to Al and F, in addition to the characteristic Ni, Co, and Mn peaks, providing direct evidence for the successful deposition of the AlF3 and LiF coating layers. The Li signal is not detected owing to its low atomic mass and weak characteristic X-ray emission. Apart from carbon—introduced during SEM sample preparation—no extraneous elements were detected, confirming the high purity of the synthesized oxides.

The experimentally determined atomic percentages are in close agreement with the theoretical values for all elements, validating the targeted stoichiometry of the composites. For the pristine LNCM sample, the atomic ratio of Ni:Co:Mn (≈1:1:3.86) corresponds well to the nominal composition Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2. Similarly, the Al content in LNCM/A matches the designed loading of 5 wt.% AlF3, as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Elemental analysis of the prepared oxides carried out by EDAX experiment.

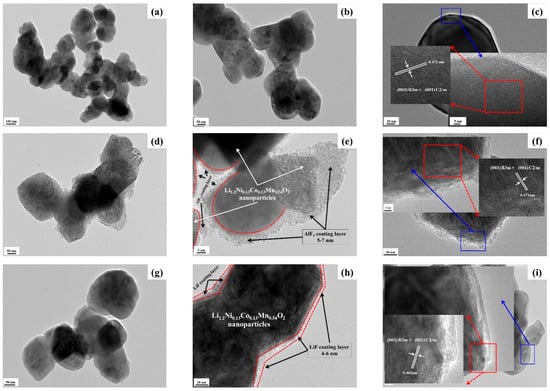

The nanostructures of both pristine and surface-modified samples were examined using TEM and HRTEM to verify the effective deposition of AlF3 and LiF coating layers on the LNCM particle surfaces. As shown in Figure 6a,d,g, all as-synthesized powders consist of homogeneous, sphere-like particles with a uniform size distribution ranging from 150 to 250 nm, indicating that the coating treatment does not affect the overall particle size. Close examination reveals that these secondary particles are formed by aggregation of smaller primary nanoparticles. Although the LNCM/A and LNCM/L samples exhibit slightly rougher surfaces compared to the pristine LNCM, no notable changes in particle shape or morphology are observed (Figure 6d,g). This suggests that the thin AlF3 and LiF coatings do not alter the structural integrity of the powders [20,70], which is consistent with the moderate temperature (400 °C) employed during the coating process.

Figure 6.

TEM and HRTEM images of powders: (a–c) for LNCM, (d–f) for LNCM/A, and (g–i) for LNCM/L.

The corresponding HRTEM images (Figure 6c,f,i) clearly reveal well-defined lattice fringes (insets) with an interplanar spacing of approximately 0.47 nm, corresponding to the (003)ex plane of the rhombohedral LiMO2 phase and/or the (001)o plane of the monoclinic Li2MnO3 lattice. These features are characteristic of Li-rich layered oxides and demonstrate excellent structural coherence between the two phases [71,72]. This confirms that the materials consist of integrated LiMO2 (R-3m) and Li2MnO3 (C2/m) domains, forming a composite layered structure in agreement with the XRD results.

The TEM and HRTEM images of LNCM/A and LNCM/L (Figure 6e–h) confirm that the particles are uniformly coated with either an amorphous AlF3 layer or an ultrathin LiF layer. The coating thicknesses are approximately 5–7 nm for LNCM/A and 4–6 nm for LNCM/L. Importantly, the HRTEM images and SAED patterns reveal that these coatings do not form perfectly continuous films. Instead, the coatings exhibit a discontinuous, island-like morphology with discrete clusters preferentially deposited at particle surfaces and grain boundaries [73]. This partial coverage maintains accessibility to the underlying substrate while providing effective protection against interfacial degradation during electrochemical cycling. A comparison of the two coating types indicates that the amorphous AlF3 layer provides superior surface protection by effectively isolating the active material from direct contact with the electrolyte. This barrier minimizes parasitic reactions and corrosion arising from HF generated during electrolyte decomposition, thereby enhancing long-term electrochemical stability. Moreover, the amorphous nature of the AlF3 coating facilitates Li+ ion transport across the surface more efficiently than a crystalline layer [41]. In contrast, the ultrathin LiF coating offers the advantage of shortening the Li+ diffusion pathway between the active particles and the electrolyte, promoting faster interfacial kinetics [2]. Consequently, variations in the electrochemical behavior of the coated samples can be primarily attributed to the intrinsic properties of these surface layers.

3.3. Raman Spectroscopic Analysis

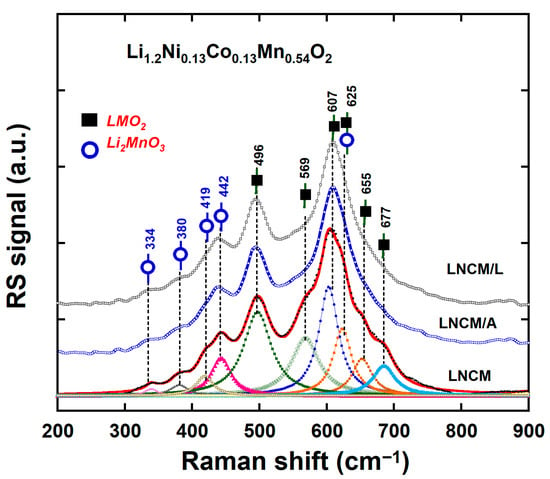

Raman spectroscopy is a non-destructive and highly effective technique for analyzing the microstructural features and surface characteristics of coating layers. It is particularly sensitive to ordered and short-range structural arrangements, making it complementary to XRD, especially for probing disordered or partially amorphous materials [74]. The Raman spectra confirm and further support the XRD findings, verifying the coexistence of two layered crystal phases—LiMO2 and Li2MnO3—in the Li-rich layered oxide materials.

The vibrational modes of layered Li-rich oxides can be characterized by two Raman-active modes (A1g + Eg species) for the layered LiMO2 phase (M = Ni, Co, Mn; R-3m space group, D3d5 symmetry) [75], and six Raman-active modes (4Ag + 2Bg species) for the layered Li2MnO3 phase (C2/m space group, C2h3 symmetry) [76]. The experimental Raman spectra of LNCM, LNCM/A, and LNCM/L (Figure 7) exhibit multiple distinct bands characteristic of both R-3m and C2/m structures, confirming the coexistence of LiMO2 and Li2MnO3 phases.

Figure 7.

Room temperature Raman spectra of LNCM, LNCM/A and LNCM/L materials recorded with the laser excitation line at 532 nm.

The two prominent peaks observed near 496 and 607 cm−1 correspond to the bending δ(O–M–O) and stretching ν(MO6) vibrations (M = Ni, Co, Mn), which are associated with the LiNi1/3Co1/3Mn1/3O2 phase [77]. Each band represents a superposition of contributions from the three transition-metal ions, giving rise to 3A1g and 3Eg modes. Additional peaks at approximately 334, 380, 419, 442, and 569 cm−1 are attributed to the Li2MnO3 phase, while the band near 673 cm−1 is assigned to the ν(Mn3+–O6) stretching vibration [76]. For the surface-modified samples, no significant peak broadening or frequency shifts were observed compared to the pristine LNCM, indicating that the AlF3 and LiF coatings do not alter the local Li-rich layered structure. Moreover, the absence of any new Raman features confirms that Li, Al, and F do not diffuse into the bulk structure, in agreement with the XRD results.

Raman spectroscopy was performed on the coated samples (as shown below). This technique is an effective tool for probing the surface of inorganic solids, as the optical penetration depth in LNCM oxides is limited to a few tens of nanometers. Raman measurements provide a direct and spatially resolved probe of the M–O bonding environment. In principle, an oxygen deficiency at the LNCM particle surface would induce a detectable shift in the A1g Raman mode associated with M–O vibrations in the LNCM lattice. However, no significant changes were observed in the vibrational spectra of the coated samples, indicating minimal surface disorder and suggesting that the coating effectively preserves the structural integrity of the particle surface, in agreement with the XRD analysis.

3.4. Electrochemical Results

The electrochemical performance of the LNCM samples was evaluated through galvanostatic charge–discharge cycling and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements. In this study, the total charge delivered by Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 was analyzed, corresponding to a theoretical specific capacity of 369 mAh g−1. This value arises from two contributions: 229 mAh g−1 from the 0.5Li2MnO3 component and 140 mAh g−1 from the 0.5LiNi1/3Co1/3Mn1/3O2 component. The combined capacity corresponds to the complete extraction of 1.2 Li+ ions per Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 formula unit [23,78].

The theoretical discharge capacity, calculated based on the mass of the discharged rock-salt phase formed after the first charge–discharge cycle, is approximately 282 mAh g−1. It is worth noting that some reports in the literature cite a lower theoretical value of ~200 mAh g−1 for similar compositions; however, the present work adopts 369 mAh g−1 as the theoretical benchmark, consistent with full lithium extraction. For clarity, all current densities are expressed in mA g−1, where 1 C corresponds to 369 mA g−1 for all electrodes.

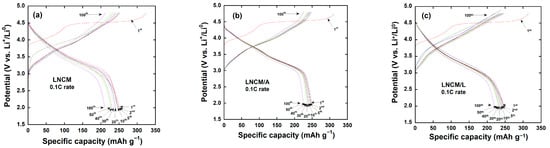

Figure 8a–c present the galvanostatic charge–discharge profiles of the LNCM, LNCM/A, and LNCM/L electrodes recorded at a C/10 rate within the voltage range of 2.0–4.8 V. The shape and evolution of the curves after the first activation cycle are consistent with previous reports [39,79,80]. The initial charge curve displays a distinct voltage plateau near 4.5 V, which corresponds to the irreversible extraction of Li2O from the Li2MnO3 component [35]. This process is associated with strong oxidation of O2− anions occurring around 4.5 V.

Figure 8.

Galvanostatic charge–discharge profiles of (a) LNCM, (b) LNCM/A and (c) LNCM/L at 0.1 C in the voltage range of 2.0–4.8 V vs. Li+/Li using 0.1 C.

The capacity contribution below 4.5 V, attributed to the oxidation of Ni2+ and Co3+ species, is approximately 118 mAh g−1 for all three electrodes, indicating that the transition-metal redox activity remains largely unaffected by the surface modification. The initial discharge capacities of the pristine LNCM and the coated samples (LNCM/A and LNCM/L) are 250.6, 248.4, and 246.2 mAh g−1, respectively, with corresponding initial Coulombic efficiencies of 76.2%, 78.8%, and 77.9%, as summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Electrochemical results of initial charge–discharge specific capacities; irreversible capacities and Coulombic efficiencies of LNCM, LNCM/A and LNCM/L.

The initial specific discharge capacities of the coated samples (LNCM/A and LNCM/L) are slightly lower than that of the pristine LNCM, which can be attributed to the electrochemically inactive nature of the AlF3 and LiF coating layers [81]. The modified materials also exhibit slightly lower irreversible capacities compared to the uncoated sample. This behavior is likely related to oxygen loss and ionic rearrangements occurring during the initial charging process, wherein a significant portion of transition-metal ions migrates from the surface toward the bulk, occupying vacancies created by the removal of Li+ and O2− ions. Consequently, during the subsequent discharge process, only part of the lithium ions can be reinserted into the crystal lattice of the cathode, leading to a higher initial irreversible capacity loss and reduced Coulombic efficiency [81,82].

The smaller irreversible capacity observed for the coated samples suggests that the surface coatings effectively mitigate parasitic side reactions, such as electrolyte decomposition and SEI film formation. The protective AlF3 and LiF layers help stabilize the surface structure, suppress interfacial degradation, and reduce charge-transfer polarization, thereby facilitating faster Li+ diffusion and improving overall electrochemical stability [22,26,83,84].

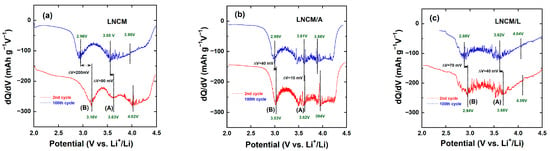

Figure 9a–c display the incremental capacity (IC) plots (−dQ/dV vs. V) derived from the discharge curves of LNCM, LNCM/A, and LNCM/L electrodes at the 2nd and 100th cycles. These plots not only reveal the characteristic reduction potentials but also provide a clear visualization of the voltage fade phenomenon. As evident from the IC profiles, the reduction peaks of all LNCM-based electrodes progressively shift toward lower potentials upon cycling. This gradual shift is typically associated with the structural transformation from a layered phase to a spinel-like phase during repeated charge–discharge processes [25,85]. After 100 cycles, the main cathodic peak (A), corresponding to the reduction of Ni4+ to Ni3+ during Li+ insertion into the layered framework, shifts by approximately 80 mV, 10 mV, and 40 mV for the LNCM, LNCM/A, and LNCM/L electrodes, respectively. The smaller peak shift observed in the coated samples, particularly in LNCM/A, suggests that the surface modification effectively mitigates the structural degradation and voltage decay typically observed in uncoated Li-rich layered oxides.

Figure 9.

Incremental capacity (−dQ/dV) plots for (a) LNCM, (b) LNCM/A and (c) LNCL electrodes at the 2nd and 100th cycle.

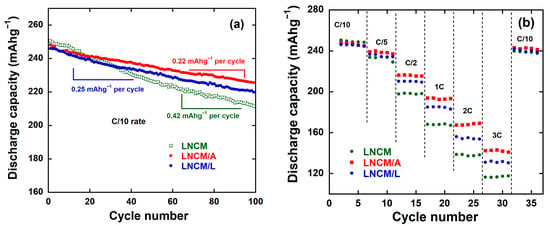

Figure 10a,b depict the cycling performance and rate capability of the LNCM, LNCM/A, and LNCM/L electrodes within the voltage range of 2.0–4.8 V. A gradual decay in specific capacity was observed upon cycling, while the characteristic S-shaped charge–discharge profile remained essentially unchanged, indicating the structural stability of the electrodes. As shown in Figure 10a, the average capacity fading rates over 100 cycles were calculated to be 0.42, 0.22, and 0.25 mAh g−1 per cycle for the LNCM, LNCM/A, and LNCM/L electrodes, respectively.

Figure 10.

(a) Cycling performance at C/10 rate and (b) Rate capability at different C-Rate for Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 electrodes.

The excellent reversibility of the coated electrodes is further evidenced by their Coulombic efficiencies, which remain close to 100% throughout the 100 cycles for both LNCM/A and LNCM/L. After 100 cycles, the capacity retention (CR) values reached 91.7% for LNCM/A and 89.6% for LNCM/L, significantly higher than that of the pristine LNCM, which retained only 84.4%. These results demonstrate that surface modification with AlF3 and LiF effectively suppresses capacity fading and enhances cycling stability.

Figure 10b presents the rate capability of the three cathode materials—LNCM, LNCM/A, and LNCM/L—tested within the voltage range of 2.0–4.8 V vs. Li+/Li at various current densities ranging from 0.1 C to 3 C. The discharge capacities were normalized to the first discharge capacity at 0.1 C for comparison. As the current rate increased, all samples exhibited a gradual decrease in discharge capacity, consistent with the kinetic limitations at higher C-rates. At low current densities, the pristine LNCM electrode delivered a slightly higher discharge capacity compared with the coated samples; however, its capacity dropped sharply at higher rates, indicating inferior rate capability. The LNCM/L electrode followed a similar trend at low C-rates but maintained higher capacities than the pristine LNCM at elevated current densities, demonstrating improved rate performance. Notably, the LNCM/A electrode exhibited the best rate capability among all samples, retaining a relatively high discharge capacity even at the highest tested rate of 3 C. This superior electrochemical behavior can be attributed to the increased surface area and reduced charge-transfer resistance of the coated material, which promote faster Li+ diffusion and enhanced electronic conductivity. Moreover, the presence of the fluoride coating, owing to its chemical stability and robust interfacial properties, effectively suppresses parasitic reactions and contributes to sustained electrochemical performance. The 5 wt.% AlF3 and LiF coatings play a crucial role in preserving the layered structure of the cathode material and protecting it from structural degradation during repeated cycling [84]. Furthermore, the surface modification effectively mitigates voltage decay by suppressing the undesired phase transformation from the layered structure to a spinel-like phase [22,25,86]. Overall, the LNCM/A electrode demonstrates superior rate capability and cycling stability, establishing it as a highly promising candidate for high-power-density lithium-ion battery applications.

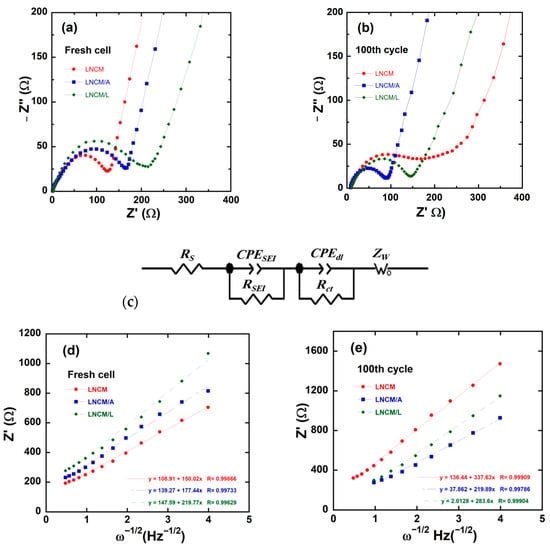

To further elucidate the influence of the AlF3 and LiF surface coatings on the electrode resistance and lithium-ion transport kinetics of LNCM, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were performed on fresh cells and after 100 charge–discharge cycles at a C/10 rate. Figure 11a–e display the corresponding Nyquist plots and the analysis of the low-frequency diffusion region. The equivalent circuit model used for fitting the EIS data is shown in Figure 11c. Experimentally, four regions can be identified in Nyquist plots: (i) The intercept at high frequency with the Z′-axis (real axis) corresponds to the uncompensated ohmic resistance of the cell (Rs); (ii) the first depressed semicircle in the high-frequency region is associated with the resistance and capacitance of the solid–electrolyte interphase (RSEI, constant-phase element (CPESEI)); (iii) the second depressed semicircle in the medium-frequency region represents the charge-transfer resistance and double-layer capacitance at the electrode/electrolyte interface (Rct, CPEdl); and (iv) in the low-frequency range, the inclined line reflects the Li+-ion diffusion process within the bulk electrode, which is characterized by the Warburg impedance, ZW(ω) = σw (1 − j) ω−1/2, where σw denotes the Warburg factor, ω is the frequency and j = √ − 1 [87]. From the Nyquist plots (Figure 11a,b), it is evident that the overall impedance decreases with progressive cycling. The internal resistances (Rs) of the fresh cells are below 10 Ω and remain nearly constant throughout the cycling process (Table 4). Measurements performed on the Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 electrodes reveal the distinct effects of the AlF3 and LiF surface coatings. Prior to cycling, the coated samples exhibit higher charge-transfer resistance (Rct) compared to the pristine electrode, indicating that the surface layers of AlF3 and LiF modify the electrode–electrolyte interface and initially impede Li+ transport. This confirms that the surface of the Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 particles is effectively modified by the coating layers. After 100 cycles, however, the semicircle in the high-frequency region becomes smaller, signifying a reduction in charge-transfer resistance, while the inclined line in the low-frequency region evolves into an arc-like shape, indicative of a finite-length Nernst diffusion process [25]. These observations suggest that the AlF3 and LiF coatings stabilize the interface, improve Li+ transport kinetics upon cycling, and suppress the accumulation of resistive surface layers that typically form in uncoated electrodes. In addition, the Rct and RSEI values decrease to even lower levels than those observed for the uncoated material, demonstrating that the coating layer effectively modifies the electrode surface by suppressing oxygen loss and preventing corrosion from electrolyte attack, which would otherwise form a resistive SEI layer [39]. Moreover, the reduction in Rct and RSEI not only minimizes cell polarization (as shown in the GCD profiles) but also enhances Li+-ion transport kinetics due to the formation of a more stable and uniform SEI film, leading to an increased diffusion coefficient. The EIS fitting parameters are summarized in Table 4. The real part of the impedance Z′(ω) is the sum of the real part of the four components:

Z′(ω) = Rs + RSEI + Rct +σw ω−1/2,

Figure 11.

EIS results for of LNCM, LNCM/A and LNCM/L electrodes. Nyquist plots (−Z″ vs. Z′ plots) of (a) fresh electrodes, (b) electrodes after 100 cycles at 0.1 C rate, (c) equivalent circuit model used to analyze EIS data. Plots of the real part of the impedance vs. ω−1/2 for (d) fresh electrodes and (e) after 100 cycles.

Table 4.

Fitting results of Nyquist plots for LNCM, LNCM/A and LNCM/L electrodes before and after 100th cycle.

Figure 11d,e present the real part of Z vs. ω−1/2 of the as-prepared and AlF3, LiF-coated Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 electrodes. From the slope of the Z vs. ω−1/2 curves, we can calculate the apparent diffusion coefficient of Li+ (DLi+) in the electrode according the following relation [88]:

in which R is the gas constant, T the absolute temperature, F the Faraday’s constant, n the number of electrons transferred, CLi is the concentration of Li+-ion inside the electrode, and A the effective surface area of the electrode. The apparent diffusion coefficients DLi+ are summarized in Table 4. For electrodes exhibiting multiphase characteristics, DLi+ represents an apparent rather than intrinsic diffusion coefficient. According to Equation (4), DLi+ is predominantly determined by the inverse of the Warburg coefficient (1/σw), where a smaller σw value indicates lower diffusion resistance and thus facilitates higher lithium-ion mobility. Prior to electrochemical cycling, as expected for the freshly prepared electrodes, the AlF3- and LiF-coated samples exhibit slightly reduced DLi+ values compared to the pristine electrode. However, after 100 cycles, the pristine electrode displays a markedly lower DLi+ than the coated counterparts. This pronounced decrease in diffusion coefficient for the uncoated sample is attributed to the accumulation of residual amorphous lithium species on the surface, which impedes Li+ transport and consequently hinders diffusion kinetics.

The coated electrodes exhibit a marked reduction in charge transfer resistance (Rct) upon cycling, signifying enhanced interfacial charge transfer kinetics and superior rate capability. The exchange current density (I0) was determined using the linearized Butler–Volmer relationship:

This parameter represents an intrinsic electrochemical property of the electrode material, independent of the cell configuration, as well as the particle size and morphology. As summarized in Table 4, the I0 values of the coated electrodes increase notably with cycling, reflecting facilitated electrochemical reactions at the electrode–electrolyte interface. This enhancement can be ascribed to the presence of the protective coating layers, which effectively suppress impedance growth by preventing direct contact between the highly delithiated electrode surface and the electrolyte. Consequently, both the electronic and ionic conductivities of the coated electrodes improve progressively with cycling, thereby promoting faster charge transfer and enhanced long-term electrochemical stability.

In a previous study, Sun et al. [20] reported that coating lithium-rich cathode materials with carbon induced structural modifications near the surface, which were attributed to the formation of a spinel phase, as confirmed by TEM analysis. In contrast, in the present work, no evidence of spinel phase formation was observed, either by TEM or XRD measurements. It is generally recognized that the primary advantage of AlF3 or LiF coatings lies in their ability to suppress oxygen loss and reinforce the structural integrity of the material. Consequently, the coating effectively reduces the formation of the spinel phase, rather than promoting it. Furthermore, the AlF3 and LiF layers enhance the stability of the cathode–electrolyte interface by providing strong resistance to HF corrosion. Therefore, AlF3 and LiF act as stabilizing agents that protect the oxide structure from degradation, leading to improved cycling stability and prolonged electrochemical lifespan.

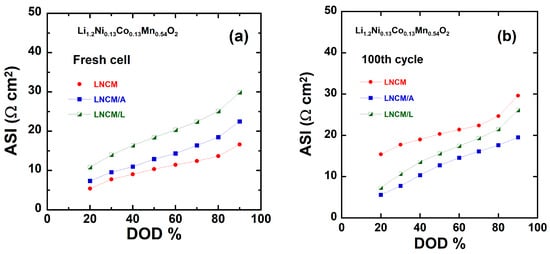

Another approach for evaluating the performance of lithium-insertion electrodes involves the determination of the area-specific impedance (ASI, in Ω cm2), which accounts for the combined effects of multiple factors influencing the overall cell potential (Figure 12). The ASI is calculated from the variation in equilibrium potential with respect to the charge passed as a function of the depth of discharge (DOD), according to the following relationship [72]:

where A represents the cross-sectional area of the electrode, ΔV = (OCV − Vcell) is the potential difference measured during a 60 s current interruption at each DOD, and I denotes the applied current. Several factors contribute to the area-specific impedance, including ohmic resistance, Li+ transport through the electrolyte, and solid-state diffusion within the electrode. Unlike electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), the area-specific impedance (ASI) technique does not require equilibrium conditions, making it a more representative method for assessing the total internal resistance during cycling. Nevertheless, the ASI results are consistent with those obtained from EIS, confirming the same electrochemical trends. As presented in Figure 12a,b, the application of a 5 wt.% AlF3 or LiF coating proves to be beneficial. At 90% depth of discharge (DOD), the ASI values for the pristine, AlF3-coated, and LiF-coated electrodes are 17, 23, and 30 Ω·cm2, respectively, in the fresh cells; after cycling, these values change to 30, 19, and 26 Ω·cm2, respectively. This variation demonstrates that the charge-transfer resistance is influenced by both the DOD and the electrode aging process. Furthermore, after 100 cycles, the increase in ASI for the pristine LNCM electrode is counterbalanced by a notable decrease in ASI for the coated LNCM/A and LNCM/L electrodes. A similar trend is observed at all depths of discharge after prolonged cycling. For instance, at 20% DOD, the ASI of the pristine LNCM electrode increases from 6 to 15 Ω·cm2, while those of LNCM/A and LNCM/L decrease from 7 and 10 to 6 and 7 Ω·cm2, respectively. This indicates that the coated electrodes exhibit improved interfacial stability and reduced impedance growth during cycling. These findings are consistent with our previous work [39] on AlF3-coated Li1.2Ni0.2Mn0.6O2 and LiCoO2-coated Li1.05Ni0.35Co0.25Mn0.4O2 cathodes, both of which demonstrated superior electrochemical performance at 90% DOD [89].

Figure 12.

Area-specific impedance (ASI) of LNCM, LNCM/A and LNCM/L electrodes as a function of depth of discharge (DOD) for (a) fresh cell and (b) after 50 cycles.

Table 5 compares the electrochemical performances of Li1.2Mn0.54Co0.13Ni0.13O2 cathode materials coated with various fluorides reported in the literature. Based on the present results, it can be concluded that the LiF and AlF3 surface modifications on Li-rich NCM materials effectively act as protective layers on the particle surface, thereby facilitating Li+ transport. Moreover, the AlF3-coated electrode exhibits superior electrochemical behavior, showing enhanced cyclic stability, higher capacity retention, and improved initial Coulombic efficiency compared to both the pristine and LiF-coated counterparts.

Table 5.

Comparison of electrochemical properties of fluoride-coated Li1.2Mn0.54Co0.13Ni0.13O2 cathode materials with the literature. CR is the capacity retention; ICE is the initial Coulombic efficiency.

4. Conclusions

In summary, uniform and ultrathin LiF and AlF3 coatings (~4–5 nm) were successfully fabricated on Li-rich layered oxide cathode materials via a facile chemical deposition method. The introduction of a controlled amount of fluoride (5 wt.%) significantly enhanced the electrochemical performance of Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2. The coated electrodes exhibited remarkable capacity stability (~220 mAh g−1 after 100 cycles at 0.1 C) and improved initial Coulombic efficiency. These enhancements are achieved through a simple, scalable, and cost-effective synthesis route that preserves the micrometer-scale particle morphology. The present findings also provide valuable insight into the contradictory reports in the literature regarding the effectiveness of fluoride coatings, highlighting that electrochemical performance is highly dependent on both the coating thickness and the synthesis approach.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.E.A.-G. and A.M.H.; methodology, A.E.A.-G.; validation, C.M.J.; formal analysis, A.E.A.-G. and S.M.A.; investigation, A.E.A.-G., A.M.H. and S.M.A.; data curation, A.E.A.-G. and S.M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.E.A.-G., A.M.H. and S.M.A.; writing—review and editing, A.M. and C.M.J.; project administration, A.M.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to authors’ rights.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASI | area-specific impedance |

| BET | Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) |

| CE | Coulombic efficiency |

| CEI | cathode–electrolyte interphase |

| CR | capacity retention |

| DMC | dimethyl carbonate |

| EC | ethylene carbonate |

| EDX | energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy |

| EIS | electrochemical impedance spectroscopy |

| EVs | electric vehicles |

| GCD | galvanostatic charge discharge |

| HRTEM | high-resolution transmission electron microscopy |

| ICE | initial Coulombic efficiency |

| LIBs | lithium-ion batteries |

| LMBs | lithium-metal batteries |

| LNCM | Li-rich Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 |

| LNCM/A | AlF3-coated Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 |

| LNCM/L | LiF-coated Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 |

| PHEVs | plug-in hybrid electric vehicles |

| SEM | scanning electron microscopy |

| SGM | sol–gel method |

| TM | transition metal |

| XPS | X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

References

- Goodenough, J.B.; Park, K.-S. The Li-ion rechargeable battery: A perspective. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 1167–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Yang, C.; Xiong, X.; Xiong, J.; Hu, R.; Chen, Y.; Liu, M. Nanoscale surface modification of lithium-rich layered-oxide composite cathodes for suppressing voltage fade. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 13058–13062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergus, J.W. Recent developments in cathode materials for lithium ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2010, 195, 939–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipper, F.; Nayak, P.K.; Erickson, E.M.; Francis Amalraj, S.; Srur-Lavi, O.; Penki, T.R.; Talianker, M.; Grinblat, J.; Sclar, H.; Breuer, O.; et al. Study of cathode materials for lithium-ion batteries: Recent progress and new challenges, a review. Inorganics 2017, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Yang, H.; Kou, L.; Tian, Z.; Shao, L.; Sari, H.M.K.; Wang, J.; et al. Optimized activation of Li2MnO3 effectively boosting rate capability of xLi2MnO3·(1 − x)LiMO2 cathode. Nano Energy 2021, 88, 106240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.-M.; Kim, D.; Park, M.-S.; Cho, M.; Cho, K. Underlying mechanisms of the synergistic role of Li2MnO3 and LiNi1/3Co1/3Mn1/3O2 in high-Mn, Li-rich oxides. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 11411–11421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, E.; Yu, X.; Lin, R.; Bi, X.; Lu, J.; Bak, S.; Nam, K.-W.; Xin, H.L.; Jaye, C.; Fischer, D.A.; et al. Evolution of redox couples in Li- and Mn-rich cathode materials and mitigation of voltage fade by reducing oxygen release. Nat. Energy 2018, 3, 690–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampardi, G.; La Mantia, F. Solid–electrolyte interphase at positive electrodes in high-energy Li-ion batteries: Current understanding and analytical tools. Batter. Supercaps 2020, 3, 672–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; He, B.; Li, Q.; Liu, H.; Qiu, L.; Liu, J.; Xiang, W.; Liu, Y.; Wang, G.; Wu, Z.; et al. Relieving capacity decay and voltage fading of Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 by Mg2+ and PO43− dual doping. Mater. Res. Bull. 2020, 130, 110923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Wu, X.; Yang, Y. Improved electrochemical performance of Li[Li0.2Mn0.54Ni0.13Co0.13]O2 cathode material by fluorine incorporation. Electrochim. Acta 2013, 105, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zou, F.; Xia, X.; Yu, T.; He, H.; Huang, X.; Hu, X. Improving the interfacial stability of Li1.2Mn0.54Ni0.13Co0.13O2 cathode and Li metal anode via dual electrolyte additives synergistic effect. Ionics 2024, 30, 4551–4561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Su, Q.; Zhang, C.; Huang, T.; Yu, A. Enhanced electrochemical performance of Li1.2Mn0.54Ni0.13Co0.13O2 cathode with an ionic conductive LiVO3 coating layer. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2015, 4, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Belharouak, I.; Li, L.; Lei, Y.; Elam, J.W.; Nie, A.; Chen, X.; Yassar, R.S.; Axelbaum, R.L. Structural and electrochemical study of Al2O3 and TiO2 coated Li1.2Ni0.13Mn0.54Co0.13O2 cathode material using ALD. Adv. Energy Mater. 2013, 3, 1299–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, J.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, J. The role of SnO2 surface coating in the electrochemical performance of Li1.2Mn0.54Co0.13Ni0.13O2 cathode materials. J. Power Sources 2016, 325, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Liu, H.; Hu, T.; Meng, Y.S.; Luo, J. Enhancing the electrochemical performance of Li-rich layered oxide Li1.13Ni0.3Mn0.57O2 via WO3 doping and accompanying spontaneous surface phase formation. J. Power Sources 2018, 375, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, C.; Du, C.; He, X.; Yin, G.; Song, B.; Zuo, P.; Cheng, X.; Ma, Y.; Gao, Y. Lithium-rich Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 oxide coated by Li3PO4 and carbon nanocomposite layers as high performance cathode materials for lithium ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 2634–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Wang, B.; Liu, J.; Kaliyappan, K.; Sun, Q.; Liu, Y.; Dadheech, G.; Balogh, M.P.; Yang, L.; Sham, T.-K.; et al. Highly stable Li1.2Mn0.54Co0.13Ni0.13O2 enabled by novel atomic layer deposited AlPO4 coating. Nano Energy 2017, 34, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Du, F.; Bian, X.; Wang, Y.; Yan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, K.; Chen, G.; Wang, C.; Wei, Y. Electrochemical performance and thermal stability of Li1.18Co0.15Ni0.15Mn0.52O2 surface coated with the ionic conductor Li3VO4. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 7555–7562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.-N.; Gao, X.-G.; Ma, S.-C.; Guo, X.; Zeng, Y.-P.; Tai, L.-H.; Wang, R.-S.; Xie, H.-M.; Sun, L.-Q. Enhancement of electrochemical performance of Li[Li0.2Mn0.54Ni0.13Co0.13]O2 by surface modification with Li4Ti5O12. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 115, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.-K.; Lee, M.-J.; Yoon, C.S.; Hassoun, J.; Amine, K.; Scrosati, B. The role of AlF3 coatings in improving electrochemical cycling of Li-enriched nickel-manganese oxide electrodes for Li-Ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 1192–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, T.; Shen, X.; Xi, X.; Liao, D. The effect of AlF3 modification on the physicochemical and electrochemical properties of Li-rich layered oxide. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 5397–5402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Gu, M.; Xiao, J.; Polzin, B.J.; Yan, P.; Chen, X.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J.-G. Functioning mechanism of AlF3 coating on the Li- and Mn-rich cathode materials. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 6320–6327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.M.; Zhang, Z.R.; Wu, X.B.; Dong, Z.X.; Zhu, Z.; Yang, Y. The effects of AlF3 coating on the performance of Li(Li0.2Mn0.54Ni0.13Co0.13)O2 positive electrode material for lithium-ion battery. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2008, 155, A775–A782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalraj, F.; Talianker, M.; Markovsky, B.; Burlaka, L.; Leifer, N.; Goobes, G.; Erickson, E.M.; Haik, O.; Grinblat, J.; Zinigrad, E.; et al. Studies of Li and Mn-rich Lix[MnNiCo]O2 electrodes: Electrochemical performance, structure, and the effect of the aluminum fluoride coating. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2013, 160, A2220–A2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, F.; Zhong, R.; Hong, R. AlF3 coating improves cycle and voltage decay of Li-rich manganese oxides. J. Mater. Sci. 2023, 58, 4525–4540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Xie, J.; Zhuang, H.; Liu, X.; Li, W.; Hu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, J. Improved low-temperature performance of surface modified lithium-rich Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 cathode materials for lithium ion batteries. Solid State Ion. 2020, 347, 115245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, J.; Huang, T.; Yu, A. CaF2-coated Li1.2Mn0.54Ni0.13Co0.13O2 as cathode materials for Li-ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2013, 109, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Huang, T.; Yu, A. Surface phase transformation and CaF2 coating for enhanced electrochemical performance of Li-rich Mn-based cathodes. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 163, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, X.; Duan, L.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, F.; He, D. The combined effect of CaF2 coating and La-doping on electrochemical performance of layered lithium-rich cathode material. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 275, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Wu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Chen, B.; Wu, N.; Wang, S. Cerium fluoride coated layered oxide Li1.2Mn0.54Ni0.13Co0.13O2 as cathode materials with improved electrochemical performance for lithium ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2014, 267, 682–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Li, Y.-X.; Chen, F.; He, X.-D.; Yasmin, A.; Hu, Q.; Wen, Z.-Y.; Chen, C.-H. In situ formation of LiF decoration on a Li-rich material for long-cycle life and superb low temperature performance. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 11513–11519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Peng, W.; Wang, Z.; Guo, H.; Hu, Q.; Li, X. Improving the electrochemical performance of Li-rich Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 cathode material by LiF coating. Ionics 2018, 24, 3717–3724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Wan, N.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Pan, D.; Bai, Y.; Lu, X. Surface-modified Li[Li0.2Ni0.17Co0.07Mn0.56]O2 nanoparticles with MgF2 as cathode for Li-ion battery. Solid State Ion. 2015, 278, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Li, Y.-X.; Wang, S.; Dong, J.-M.; Yasmin, A.; Hu, Q.; Wen, Z.-Y.; Chen, C.-H. Towards improved structural stability and electrochemical properties of a Li-rich material by a strategy of double gradient surface modification. Nano Energy 2019, 61, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Yang, Z. Re-understanding the function mechanism of surface coating: Modified Li rich layered Li1.2Mn0.54Ni0.13Co0.13O2 cathodes with YF3 for high performance lithium-ions batteries. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 12484–12494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, Z.; Wan, J.; Liu, S. Improved electrochemical properties of YF3-coated Li1.2Mn0.54Ni0.13Co0.13O2 as cathode for Li-ion batteries. Ionics 2017, 23, 1365–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, X.; Guo, H.; Wang, C.; Cheng, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Huo, H. Surface modification of Li1.2Mn0.54Ni0.13Co0.13O2 cathode materials with SmF3 and the improved electrochemical properties. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 29, 19207–19218. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.-D.; Xu, J.; Xia, J.-S.; Liu, W.; Xiong, X.; Zheng, Z.-A. Influences of FeF3 coating layer on the electrochemical properties of Li[Li0.2Mn0.54Ni0.13Co0.13]O2 cathode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Solid State Ion. 2016, 292, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Ghany, A.; El-Tawil, R.S.; Hashem, A.M.; Mauger, A.; Julien, C.M. Improved electrochemical performance of LiNi0.5Mn0.5O2 by Li-enrichment and AlF3 coating. Materialia 2019, 5, 100207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Qin, Y.; Amine, K.; Sun, Y.-K. Role of surface coating on cathode materials for lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. 2010, 20, 7606–7612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, L.; Dong, Z.; Yin, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yang, S.; Chen, L. In situ constructed organic/inorganic hybrid interphase layers for high voltage Li-ion cells. J. Power Sources 2018, 407, 132–136. [Google Scholar]

- Abuzeid, H.M.; Julien, C.M.; Zhu, L.; Hashem, A.M. Green synthesis of nanoparticles and their energy storage, environmental, and biomedical applications. Crystals 2023, 13, 1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Carjaval, J. Recent developments of the program FULLPROF. Commission on Powder Diffraction (IUCr). Newsletter 2001, 26, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Tewodros Aregai, G.; Vijaya Babu, K.; Vikram Babu, B.; Subba Rao, P.S.V.; Veeraiah, V. Effect of zinc substitution on structural and impedance properties of layered LiNi1/3Co(1/3−x)Mn1/3ZnxO2 (0.05 ≤ x ≤ 0.2) cathode materials. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2016, 4, 734–743. [Google Scholar]

- Yabuuchi, N.; Kawamoto, Y.; Hara, R.; Ishigaki, T.; Hoshikawa, A.; Yonemura, M.; Kamiyama, T.; Komaba, S. A comparative study of LiCoO2 polymorphs: Structural and electrochemical characterization of O2-, O3-, and O4-type phases. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 9131–9142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, C.S.; Li, N.; Lefief, C.; Vaughey, J.T.; Thackeray, M.M. Synthesis, characterization and electrochemistry of lithium battery electrodes: xLi2MnO3∙(1 − x)LiMn0.333Ni0.333Co00.333O2 (0 ≤ x ≤ 0.7). Chem. Mater. 2008, 20, 6095–6106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llanos, P.S.; Ahaliabadeh, Z.; Miikkulainen, V.; Lahtinen, J.; Yao, L.; Jiang, H.; Kankaanpaa, T.; Kallio, T.M. High Voltage Cycling Stability of LiF-Coated NMC811 Electrode. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 2216–2230. [Google Scholar]

- Julien, C.M.; Mauger, A. Functional behavior of AlF3 coatings for high-performance cathode materials for lithium-ion batteries. AIMS Mater. Sci. 2019, 6, 406–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, J.; Xiong, H.; Li, W.; Guo, P.; Yang, Z.; Xie, M. Enhanced cyclic stability of LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2 (NCM811) by AlF3 coating via atomic layer deposition. Ionics 2022, 28, 4547–4554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhou, L.; Cheng, Z.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Du, T. Recent Advances on F-Doped Layered Transition Metal Oxides for Sodium Ion Batteries. Molecules 2023, 28, 8065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.; Mu, Y.; Zou, L.; Wu, F.; Yang, L.; Feng, Y.; Zeng, L. Oxygen Release in Ni-Rich Layered Cathode for Lithium-Ion Batteries: Mechanisms and Mitigating Strategies. ChemElectroChem 2024, 11, e202300653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Feng, Z.; Cheng, T.; Lyu, Y.; Guo, B. Effect of Fluorine Substitution on Electrochemical Property showing F-substitution suppresses irreversible oxygen release and mitigates Mn valence reduction. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2021, 38, 088201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, R.D. Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides. Acta Cryst. A 1976, 32, 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipper, F.; Bouzaglo, H.; Dixit, M.; Erickson, E.M.; Weigel, T.; Talianker, M.; Grinblat, J.; Burstein, L.; Schmidt, M.; Lampert, J.; et al. From surface ZrO2 coating to bulk Zr doping by high temperature annealing of nickel-rich lithiated oxides and their enhanced electrochemical performance in lithium ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 8, 1701682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wu, B.; Li, N.; Mu, D.; Zhang, C.; Wu, F. Rod-like hierarchical nano/micro Li1.2Ni0.2Mn0.6O2 as high performance cathode materials for lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2013, 240, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Z.; Qiao, Q.Q.; Li, G.R.; Ye, S.H.; Gao, X.P. Surface modification of Li rich layered Li(Li0.17Ni0.25Mn0.58)O2 oxide as cathode material for lithium-ion battery. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 13104–13109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Chen, D.; Liao, Y.; Zhong, X.; Li, W.; Zhang, Y. Layered lithium-rich oxide nanoparticles doped with spinel phase: Acidic sucrose-assistant synthesis and excellent performance as cathode of lithium ion battery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 4575–4584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, W.; Schwarz, B.; Knapp, M.; Senyshyn, A.; Missiul, A.; Mu, X.; Wang, S.; Kübel, C.; Binder, J.R.; Indris, S.; et al. (De) lithiation mechanism of hierarchically layered LiNi1/3Co1/3Mn1/3O2 cathodes during high-voltage cycling. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, A5025–A5032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, L.; Dong, S.; Zeng, J.; Shen, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, X.; Ma, L.; Hai, C.; Zhou, Y. Improving the electrochemical performances of Li-rich Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 through cooperative doping of Na+ and Mg2+. Electrochim. Acta 2022, 414, 140169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, G.K.; Hall, W.H. X-ray line broadening from filed aluminium and wolfram. Acta Metallur. 1953, 1, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathiya, M.; Rousse, G.; Ramesha, K.; Laisa, C.P.; Vezin, H.; Sougrati, M.T.; Doublet, M.-L.; Foix, D.; Gonbeau, D.; Walker, W.; et al. Reversible anionic redox chemistry in high-capacity layered-oxide electrodes. Nat. Mater. 2013, 12, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, R.; Morasch, R.; Karayaylali, P.; Phillips, K.; Maglia, F.; Stinner, C.; Shao-Horn, Y.; Gasteiger, H.A. Effect of Ambient Storage on the Degradation of Ni-Rich Positive Electrode Materials (NMC811) for Li-Ion Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2018, 165, A132–A141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; Zheng, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, B.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J.-G. Tailoring grain boundary structures and chemistry of Ni-rich layered cathodes for enhanced cycle stability of lithium-ion batteries. Nat. Energy 2018, 3, 600–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthiram, A. A reflection on lithium-ion battery cathode chemistry. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-N.; Li, Q.; Ouyang, C.; Yu, X.; Ge, M.; Huang, X.; Hu, E.; Ma, C.; Li, S.; Xiao, R.; et al. Trace doping of multiple elements enables stable battery cycling of LiCoO2 at 4.6 V. Nat. Energy 2019, 4, 594–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wu, M.; Zong, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Y.; Yang, G. Synthesis and structural properties of xLi2MnO3·(1−x)LiNi0.5Mn0.5O2 single crystals towards enhancing reversibility for lithium-ion battery/pouch cells. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 770, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Li, J.; Wu, X.; Liu, Z.; Xiong, L.; Yin, Z. Improved electrochemical performance of Li1.2Ni0.2Mn0.6O2 cathode material for lithium ion batteries synthesized by the polyvinyl alcohol assisted sol-gel method. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 2320–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Li, G.; Guan, X.; Zheng, J.; Li, L. Composites Li1+xMn0.5+0.5x Ni0.5−0.5xO2 (0.1 ≤ x ≤ 0.4): Optimized preparation to yield an excellent cycling performance as cathode for lithium-ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2012, 61, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Banis, M.N.; Wang, C.; Wu, B.; Huang, Y.; Cao, S.; Li, J.; Jamil, S.; Lin, X.; Zhao, F.; et al. Tailoring bulk Li+ ion diffusion kinetics and surface lattice oxygen activity for high-performance lithium-rich manganese-based layered oxides. Energy Storage Mater. 2021, 37, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, B.-J.; Wang, C.-J.; Chen, C.-H.; Tsai, Y.-W.; Venkateswarlu, M. Electrochemical properties of Li [NixLi(1−2x)/3Mn(2−x)/3]O2 (0 ≤ x ≤ 0.5) cathode materials prepared by a sol–gel process. J. Power Sources 2005, 146, 658–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, D.; Sefat, A.S.; Kalnaus, S.; Li, J.; Meisner, R.A.; Payzant, E.A.; Abraham, D.P.; Wood, D.L.; Daniel, C. Investigating phase transformation in the Li1.2Co0.1Mn0.55Ni0.15O2 lithium-ion battery cathode during high-voltage hold (4.5 V) via magnetic, X-ray diffraction and electron microscopy studies. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 6249–6261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.B.; Liu, H.; Liu, Z.; Xiao, P.; Lai, M.O.; Lu, L. High rate capability caused by surface cubic spinels in Li-rich layer-structured cathodes for Li-ion batteries. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 3094. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, L.A.; Van Atta, S.; Cavanagh, A.S.; Yan, Y.; George, S.M.; Liu, P.; Dillon, A.C.; Lee, S.-H. Electrochemical effects of ALD surface modification on combustion synthesized LiNi1/3Mn1/3Co1/3O2 as a layered-cathode material. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 3317–3324. [Google Scholar]

- Julien, C.M.; Mauger, A. In situ Raman analyses of electrode materials for Li-ion batteries. AIMS Mater. Sci. 2018, 5, 650–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, A.M.A.; Abdel-Ghany, A.E.; Eid, A.E.; Trottier, J.; Zaghib, K.; Mauger, A.; Julien, C.M. Study of the surface modification of LiNi1/3Co1/3Mn1/3O2 cathode material for lithium ion battery. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 8632–8637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien, C.M.; Massot, M. Lattice vibrations of materials for lithium rechargeable batteries. III. Lithium manganese oxides. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2003, 100, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Chen, L.; Su, Y.; Tan, J.; Bao, L.; Lu, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, R.; Chen, S.; Wu, F. An interfacial framework for breaking through the Li-ion transport barrier of Li-rich layered cathode materials. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 24292–24298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Lai, M.O.; Lu, L. Influence of Ru substitution on Li-rich 0.55Li2MnO3·0.45LiNi1/3Co1/3Mn1/3O2 cathode for Li-ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2012, 80, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.-H.; Kempgens, P.; Greenbaum, S.; Kropf, A.J.; Amine, K.; Thackeray, M.M. Interpreting the structural and electrochemical complexity of 0.5Li2MnO3·0.5LiMO2 electrodes for lithium batteries (M = Mn0.52−xNi0.52−xCo2x, 0 ≤ x ≤ 0.5). J. Mater. Chem. 2007, 17, 2069–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, A.M.; Abdel-Ghany, A.E.; El-Tawil, R.S.; Mauger, A.; Julien, C.M. Effect of Na doping on the electrochemical performance of Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 cathode for lithium-ion batteries. Sustain. Chem. 2022, 3, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, T.; Qi, W.; Liu, X.-S.; Wu, X.-Q.; Fan, D.-H.; Guo, S.-H.; Wang, L. Improvement of the electrochemical performance of Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 cathode material by Al2O3 surface coating. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2020, 859, 113845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Zhang, X.; Liu, T.; Xu, X.; Huang, Y.; Wang, G.; Yang, X. Hierarchically structured lithium-rich layered oxide with exposed active {010} planes as high-rate-capability cathode for lithium-ion batteries. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 8970–8981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, C.; Zhao, J.; Chen, J.; Cao, C. Li-rich nanoplates of Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 layered oxide with exposed {010} planes as a high-performance cathode for lithium-ion batteries. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 734, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Ren, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Z.; Jia, S. Enhanced electrochemical properties of Li1⋅2Ni0⋅13Co0⋅13Mn0⋅54O2 coated with Al2O3 nano-film. Vacuum 2021, 183, 109757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Ghany, A.; Hashem, A.M.; Mauger, A.; Julien, C.M. Lithium-rich cobalt-free manganese-based layered cathode materials for Li-ion batteries: Suppressing the voltage fading. Energies 2020, 13, 3487. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, T.; Han, Y.; Song, D.; Shi, X.; Zhang, L.; Bie, L. Enhanced electrochemical performance of Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 by surface modification with the fast lithium-ion conductor Li-La-Ti-O. J. Power Sources 2017, 364, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.; Raistrick, I.D.; Huggins, R.A. Application of a-c techniques to the study of lithium diffusion in tungsten trioxide thin films. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1980, 127, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiderska-Mocek, A.; Lewandovski, A. Kinetics of Li-ion transfer reaction at LiMn2O4, LiCoO2, and LiFePO4 cathodes. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2017, 21, 1365–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]