Layer-by-Layer Hybrid Film of PAMAM and Reduced Graphene Oxide–WO3 Nanofibers as an Electroactive Interface for Supercapacitor Electrodes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis of WO3 Nanofibers

2.3. Preparation of GO–WO3 Dispersion

2.4. Fabrication of Multilayer Films via Layer-by-Layer Assembly

2.5. Electrochemical Reduction in GO

2.6. Characterization Techniques

3. Results and Discussion

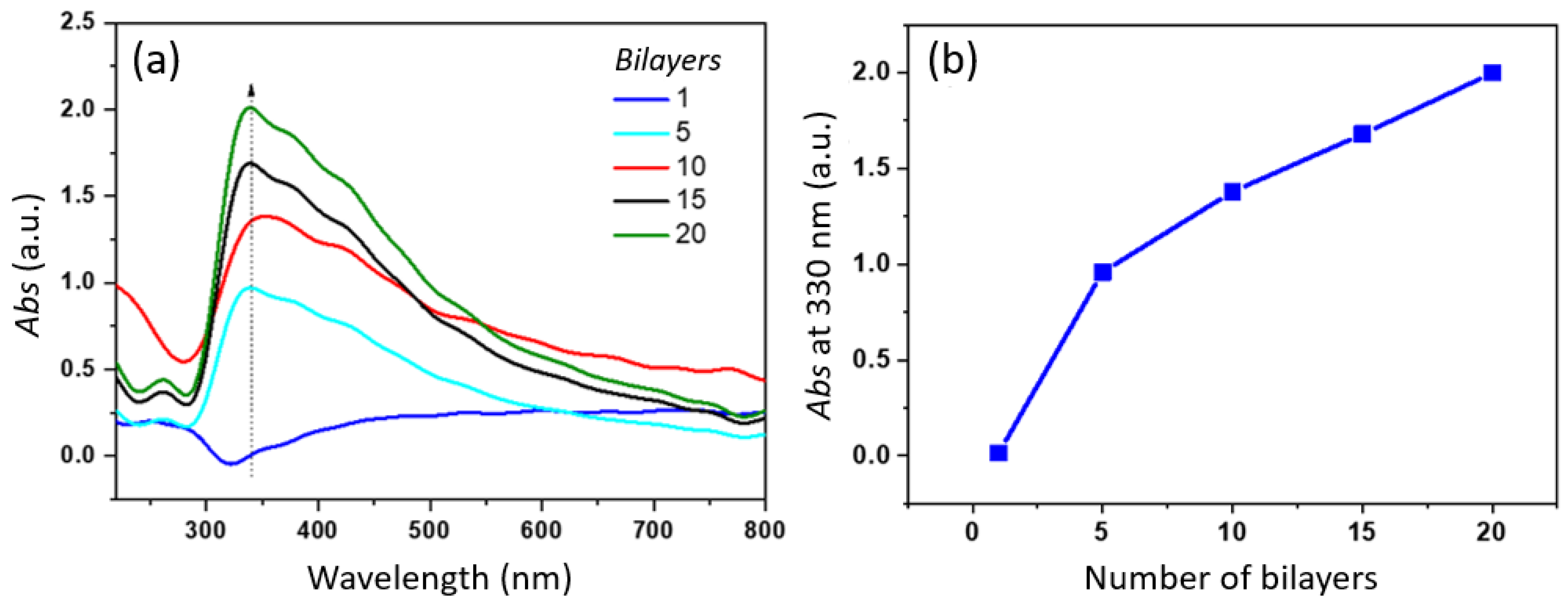

3.1. Optical Growth and Structural Characterization

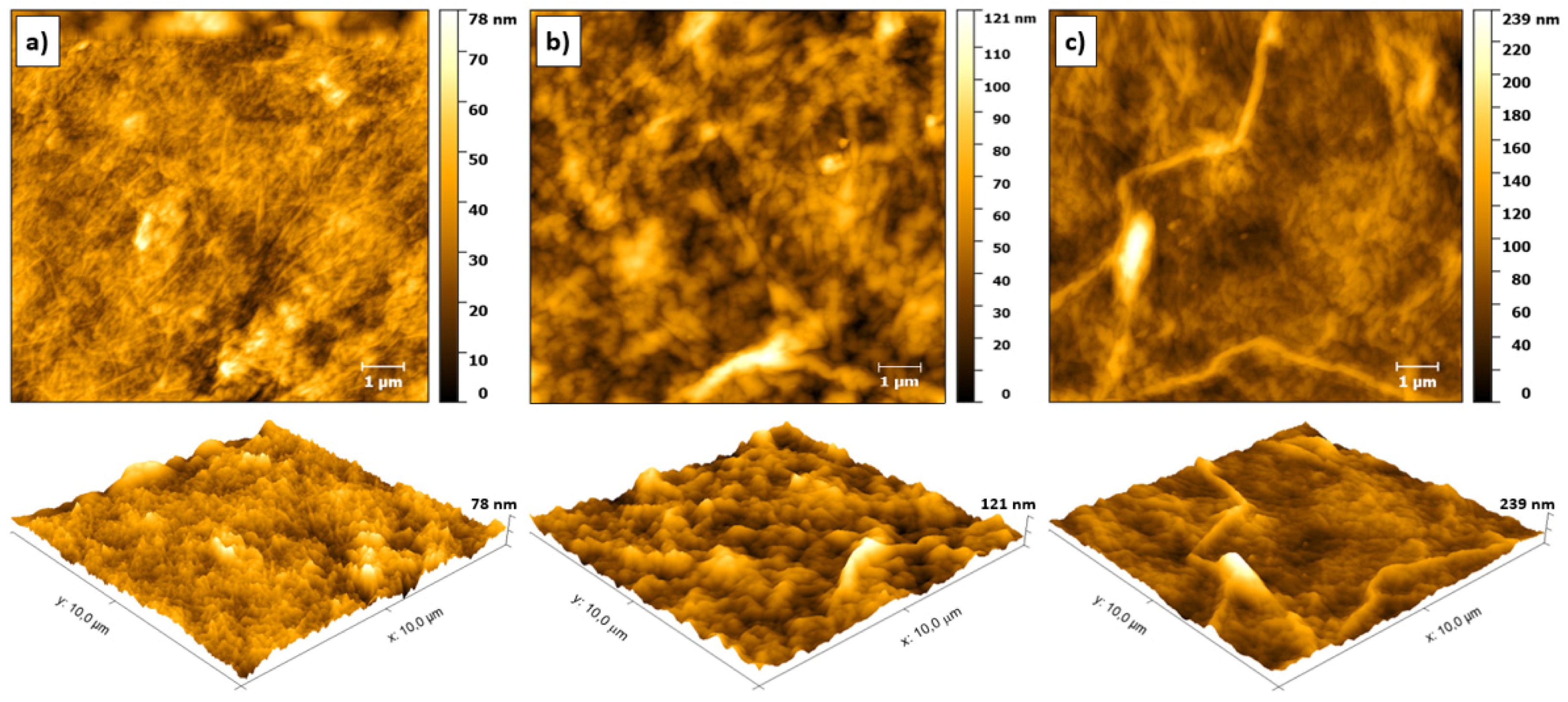

3.2. Morphological Analysis

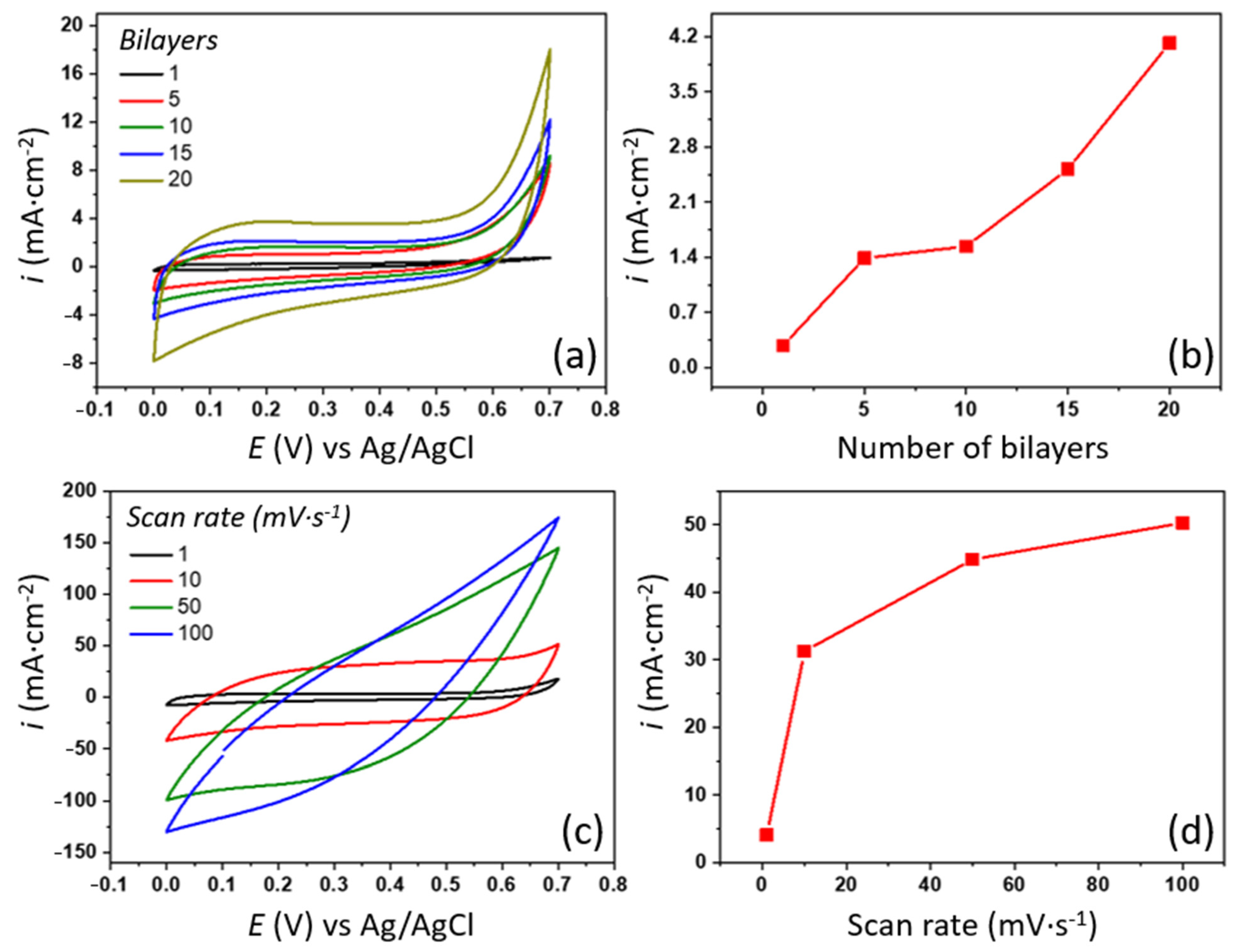

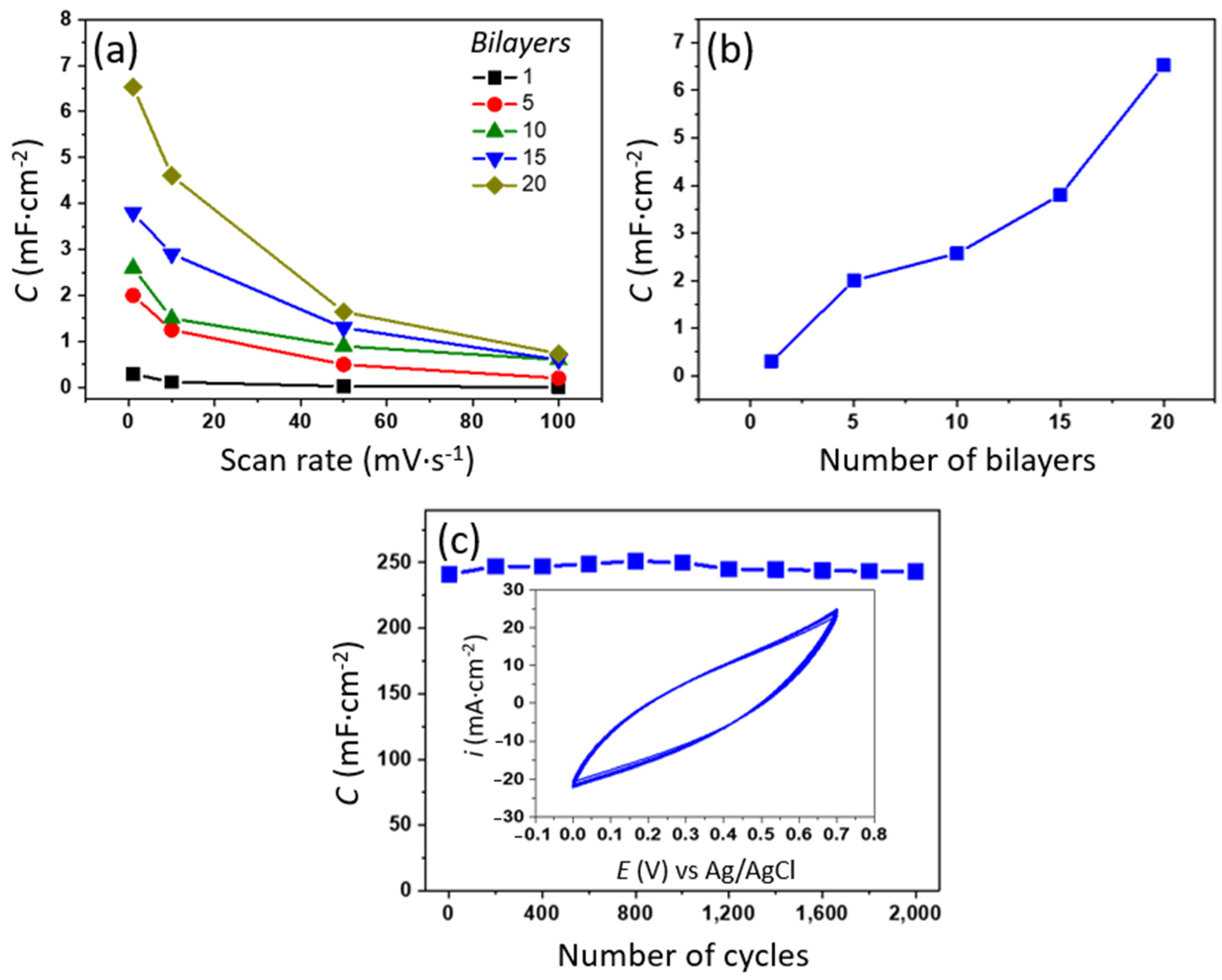

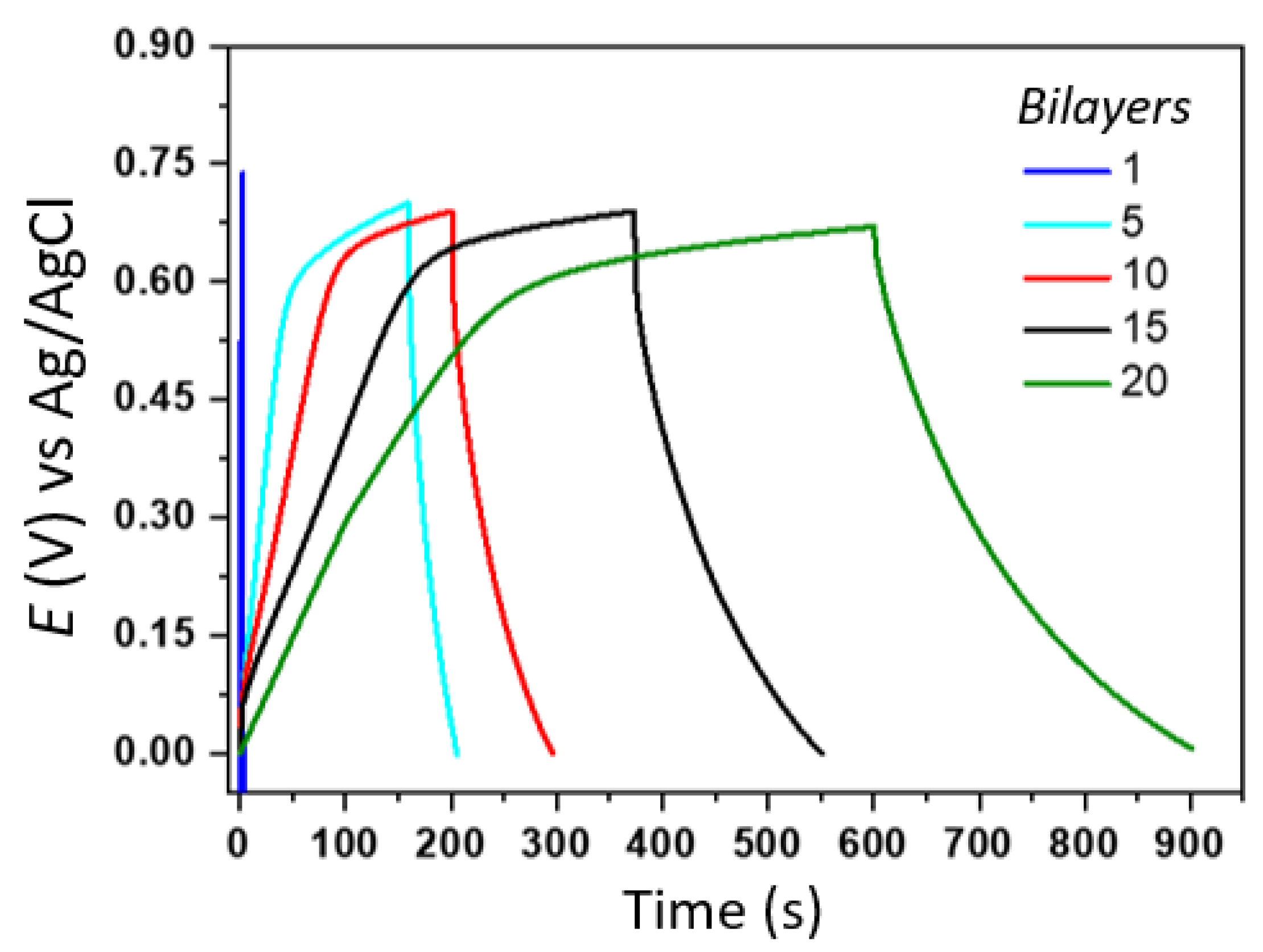

3.3. Electrochemical Characterization of (PAMAM/rGO-WO3)n LbL Films

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yu, M.; Peng, Y.; Wang, X.; Ran, F. Emerging Design Strategies Toward Developing Next-Generation Implantable Batteries and Supercapacitors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2301877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, H.J.; Choi, C.; Lee, D.Y.; Kim, H.; Yun, J.-H.; Kim, J.M.; Kang, T.M.; Ovalle, R.; Baughman, R.H.; Kee, C.W.; et al. Biomolecule-Based Fiber Supercapacitor for Implantable Device. Nano Energy 2018, 47, 385–392. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Sun, X.; Peng, H. An Implantable Fiber Biosupercapacitor with High Power Density by Multi-Strand Twisting Functionalized Fibers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202303268. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, J.; Yin, L.; Chen, X.; Jeerapan, I.; Silva, C.A.; Li, Y.; Le, M.; Lin, Z.; Wang, L.; Trifonov, A.; et al. Wearable Biosupercapacitor: Harvesting and Storing Energy from Sweat. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2102915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, G.B.; Siqueira, J.R. Nanostructured Supercapacitors for Healthcare Devices: Advances and Perspectives. Mod. Concepts Mater. Sci. 2025, 7, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D.A.; Carvalho, G.B.; Morais, P.V.; Caseli, L.; Siqueira, J.R. Hybrid Nanostructures as Advanced Electrode Materials for Supercapacitors. In Supercapacitors: Fundamentals, Advances and Future Applications; Verma, D.K., Aslam, J., Eds.; Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2025; Volume 3, pp. 399–423. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Wei, B. Supercapacitors Based on Nanostructured Carbon. Nano Energy 2013, 2, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, M.; Xiang, C.; Li, J.; Li, M.; Wu, N. Nanostructured Carbon–Metal Oxide Composite Electrodes for Supercapacitors: A Review. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Deng, S.; Chen, G.; Li, Q.; Han, B.; Han, R.; Wang, Y. Graphene Nanosheets–Tungsten Oxides Composite for Supercapacitor Electrode. Ceram. Int. 2014, 40, 4109–4116. [Google Scholar]

- Ammar, A.U.; Stan, M.; Popa, A.; Toloman, D.; Macavei, S.; Leostean, C.; Ciorita, A.; Erdem, E.; Rostas, A.M. All-in-One Supercapacitor Devices Based on Nanosized Mn4+-Doped WO3. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, E.; Thind, S.S.; Chen, S.; Chen, A. Synthesis and Electrochemical Studies of WO3-based Nanomaterials for Environmental, Energy and Gas Sensing Applications. Electrochem. Sci. Adv. 2022, 2, e202100146. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Ding, T.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Chen, C.; Fang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Huo, K.; Dai, J. Tungsten Oxide Nanofibers Self-Assembled Mesoscopic Microspheres as High-Performance Electrodes for Supercapacitor. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 174, 728–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, G.; Liu, W.; Li, D.; Chen, R.; Zheng, F.; Ni, H. Simple Synthesis of 1D, 2D and 3D WO3 Nanostructures on Stainless Steel Substrate for High-Performance Supercapacitors. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 778, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoselov, K.S.; Fal’Ko, V.I.; Colombo, L.; Gellert, P.R.; Schwab, M.G.; Kim, K. A Roadmap for Graphene. Nature 2012, 490, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siqueira, J.R.; Oliveira, O.N. Carbon-Based Nanomaterials. In Nanostructures; Akinwande, D., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Chapter 9; pp. 233–249. [Google Scholar]

- Decher, G. Fuzzy Nanoassemblies: Toward Layered Polymeric Multicomposites. Science 1997, 277, 1232–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariga, K.; Hill, J.P.; Ji, Q. Layer-by-Layer Assembly as a Versatile Bottom-Up Nanofabrication Technique for Exploratory Research and Realistic Applications. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2007, 9, 2319–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, O.N.; Iost, R.M.; Siqueira, J.R.; Crespilho, F.N.; Caseli, L. Nanomaterials for Diagnosis: Challenges and Applications in Smart Devices Based on Molecular Recognition. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 14745–14766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D.A.; Gasparotto, L.H.S.; Siqueira, J.R. Processing of Nanomaterials in Layer-by-Layer Films: Potential Applications in (Bio)Sensing and Energy Storage. An. Acad. Bras. Ciências 2019, 91, e20181343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Pan, Q.; Rempel, G.L. Bimetallic Dendrimer-Encapsulated Nanoparticles as Catalysts: A Review of the Research Advances. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 1619–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, E.; Aval, S.F.; Akbarzadeh, A.; Milani, M.; Nasrabadi, H.T.; Joo, S.W.; Hanifehpour, Y.; Nejati-Koshki, K.; Pashaei-Asl, R. Dendrimers: Synthesis, Applications, and Properties. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, J.R.; Gabriel, R.C.; Zucolotto, V.; Silva, A.C.A.; Dantas, N.O.; Gasparotto, L.H.S. Electrodeposition of Catalytic and Magnetic Gold Nanoparticles on Dendrimer–Carbon Nanotube Layer-by-Layer Films. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 14340–14343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparotto, L.H.S.; Castelhano, A.L.B.; Gabriel, R.C.; Dantas, N.O.; Oliveira, O.N.; Siqueira, J.R. Electrogeneration of Platinum Nanoparticles in a Matrix of Dendrimer–Carbon Nanotubes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 17887–17892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasparotto, L.H.S.; Castelhano, A.L.B.; Silva, A.C.A.; Dantas, N.O.; Oliveira, O.N.; Siqueira, J.R. Dendrimer–Carbon Nanotube Layer-by-Layer Film as an Efficient Host Matrix for Electrogeneration of PtCo Electrocatalysts. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 2384–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morais, P.V.; Suman, P.H.; Silva, R.A.; Orlandi, M.O. High gas sensor performance of WO3 nanofibers prepared by electrospinning. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 864, 158745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, S.; Tyson, T.A.; Shukla, S.; Negusse, E.; Chen, H.; Bai, J. Investigation of Structural and Electronic Properties of Graphene Oxide. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 99, 013104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fávero, V.O.; Oliveira, D.A.; Lutkenhaus, J.L.; Siqueira, J.R. Layer-by-Layer Nanostructured Supercapacitor Electrodes Consisting of ZnO Nanoparticles and Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 6719–6728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D.A.; Lutkenhaus, J.L.; Siqueira, J.R. Building up Nanostructured Layer-by-Layer Films Combining Reduced Graphene Oxide–Manganese Dioxide Nanocomposite in Supercapacitor Electrodes. Thin Solid Film. 2021, 718, 138483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D.A.; da Silva, R.A.; Orlandi, M.O.; Siqueira, J.R. Exploring ZnO Nanostructures with Reduced Graphene Oxide in Layer-by-Layer Films as Supercapacitor Electrodes for Energy Storage. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 7023−7034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D.A.; Siqueira, J.R. Layer-by-Layer Films of Graphene Oxide−MnO2−NbO2 for Nanostructured Energy Storage Applications. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2025, 8, 19202−19214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Padha, B.; Verma, S.; Satapathi, S.; Gupta, V.; Arya, S. Recent Advances, Challenges, and Prospects of Piezoelectric Materials for Self-Charging Supercapacitors. J. Energy Storage 2022, 47, 103547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadoss, A.; Saravanakumar, B.; Lee, S.W.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, S.J.; Wang, Z.L. Piezoelectric-Driven Self-Charging Supercapacitor Power Cell. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 4337–4345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, H.K.; Kumar, P.; Sahu, V.; Singh, K.; Narayanan, T.N. Partially Carbonized Tungsten Oxide as Electrode Material for Asymmetric Supercapacitors. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2022, 26, 2039–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, D.C.; Raj, D.P.; Deshmukh, P.R. Performance of Chemically Synthesized Polyaniline Film-Based Asymmetric Supercapacitor: Effect of Reaction Bath Temperature. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2023, 292, 116432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periasamy, P.; Muthukumaran, B.; Rajasekaran, N. Investigation of Electrochemical Properties of Microwave-Irradiated Tungsten Oxide (WO3) Nanorod Structures for Supercapacitor Electrode in KOH Electrolyte. Mater. Res. Express 2018, 5, 085007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Li, L.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y. An Aqueous Asymmetric Supercapacitor Based on Activated Carbon and Tungsten Trioxide Nanowire Electrodes. Chin. J. Chem. 2017, 35, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulraj, S.; Jayavel, R. Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Ru- and Ce-Doped Tungsten Oxide for Supercapacitor Electrodes. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2018, 29, 13794–13802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firat, Y.E. Pseudocapacitive Energy Storage Properties of rGO–WO3 Electrode Synthesized by Electrodeposition. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2021, 133, 105938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, V.V.; Anjana, P.M.; Rakhi, R.B. One-Pot Synthesis of Tungsten Oxide Nanomaterial and Application in the Field of Flexible Symmetric Supercapacitor Energy Storage Device. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 62, 848–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kady, M.F.; Strong, V.; Dubin, S.; Kaner, R.B. Laser Scribing of High-Performance and Flexible Graphene-Based Electrochemical Capacitors. Science 2012, 335, 1326–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eustache, E.; Lethien, C.; Le Bideau, J.; Brousse, T.; Tanguy, C.; Crosnier, O. High Areal Energy 3D-Interdigitated Micro-Supercapacitors in Aqueous and Ionic Liquid Electrolytes. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2017, 2, 1700126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Electrode Composition | Specific Capacitance (F·g−1) | Reference Number |

|---|---|---|

| Carbonized tungsten oxide | 31.4 | [33] |

| PANI as a cathode and tungsten oxide (WO3) as an anode | 43.0 | [34] |

| Irradiated tungsten oxide nanostructures | 44.0 | [35] |

| Activated carbon as the positive electrode and WO3 negative electrode | 51.0 | [36] |

| Ruthenium (Ru) and cerium (Ce) doped tungsten oxide (WO3) | 52.0 | [37] |

| rGO-WO3 nanocomposite | 58.3 | [38] |

| Flexible WO3 electrodes | 64.0 | [39] |

| PAMAM/rGO-WO3 | 73.6 | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gomes Junior, V.F.; Oliveira, D.A.; Morais, P.V.; Siqueira Junior, J.R. Layer-by-Layer Hybrid Film of PAMAM and Reduced Graphene Oxide–WO3 Nanofibers as an Electroactive Interface for Supercapacitor Electrodes. Nanoenergy Adv. 2025, 5, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/nanoenergyadv5040022

Gomes Junior VF, Oliveira DA, Morais PV, Siqueira Junior JR. Layer-by-Layer Hybrid Film of PAMAM and Reduced Graphene Oxide–WO3 Nanofibers as an Electroactive Interface for Supercapacitor Electrodes. Nanoenergy Advances. 2025; 5(4):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/nanoenergyadv5040022

Chicago/Turabian StyleGomes Junior, Vanderley F., Danilo A. Oliveira, Paulo V. Morais, and José R. Siqueira Junior. 2025. "Layer-by-Layer Hybrid Film of PAMAM and Reduced Graphene Oxide–WO3 Nanofibers as an Electroactive Interface for Supercapacitor Electrodes" Nanoenergy Advances 5, no. 4: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/nanoenergyadv5040022

APA StyleGomes Junior, V. F., Oliveira, D. A., Morais, P. V., & Siqueira Junior, J. R. (2025). Layer-by-Layer Hybrid Film of PAMAM and Reduced Graphene Oxide–WO3 Nanofibers as an Electroactive Interface for Supercapacitor Electrodes. Nanoenergy Advances, 5(4), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/nanoenergyadv5040022