Abstract

Blood pressure prediction in adolescents continues to remain a major challenge for health practitioners. In classical regression, many factors are found to be statistically significant based on p-values due to large sample sizes, but they may not be equally important predictors for an outcome variable. Machine learning methods provide non-linear and non-parametric approaches with superior predictive performance and a lower chance of model misspecification. Therefore, we employed a leave-one-covariate-out (LOCO) method, a novel variable importance measure, in addition to linear mixed-effects models integrated within random forest for prediction of longitudinal blood pressure. We used health markers such as BMI and dietary habits of 2379 Black and White adolescent girls, tracked yearly from ages 9 and 10 until 19 in the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Growth and Health Study (NGHS, USA). Age, BMI, waist circumference, and dietary cholesterol were consistently the most quantitatively important variables for prediction of systolic blood pressure (SBP). However, age, BMI and waist circumference were consistently the most quantitatively important covariates for prediction of diastolic blood pressure (DBP). The study findings demonstrate the importance of understanding how dietary habits and health markers influence blood pressure.

1. Introduction

On a global scale, hypertension is the leading cause of death and disability-adjusted life years lost. It is responsible for more fatalities than any other risk factor that can be modified, and is second only to cigarette smoking in terms of preventable causes of mortality in the United States [1]. High blood pressure in children is typically asymptomatic until issues arise; however, it may have negative effects on future cardiovascular health, in part due to early unfavorable vascular alterations, as well as the misidentification of high blood pressure values from childhood into adulthood [2,3]. Although blood pressure does not closely follow other cardiovascular risk factors, like body fat and dietary cholesterol, longitudinal studies have shown that childhood blood pressure is predictive of adult hypertension, a cardiovascular disease risk factor [4,5,6,7]. Blood pressure prediction in adolescents continues to remain a major challenge for clinicians.

Recent work applying machine learning to adolescent blood pressure prediction has reported improved performance over traditional models [8,9]. With advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), state-of-the-art models such as neural networks and random forests (RFs) are being utilized for illness prediction in healthcare. Methods of ML have provided non-linear and non-parametric approaches with superior predictive performance and a lower chance of model misspecification [8]. Random forests with mixed effects combine the benefits of regression forests with the capability of modeling hierarchical dependencies [9]. In classical regression, we identify significant predictors using p-values, but with large sample sizes many covariates can attain very small p-values (e.g., <0.001) despite having negligible effect sizes. This makes it difficult to distinguish the relative predictive importance of different covariates. This research will enable us to identify quantitatively significant predictors with their relative importance for the prediction of an outcome variable. Random forests possess inevitable variability due to stochasticity, but an appropriate number of trees leads to model stability [10]. Ongoing developments in AI, machine learning, and explainable AI provide new approaches for generating stable and interpretable results [11]. In this research, we evaluate a mixed-effects random forest with leave-one-covariate-out (LOCO) importance to quantify and rank covariates for adolescent SBP and DBP in NGHS, both overall and by race.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

The data used in this manuscript were obtained from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Growth and Health Study (NGHS) [12]. The study enrolled 2379 adolescent girls, of whom 1213 identified as Black and the remaining participants identified as White. The study was conducted across the University of California, Berkeley, the University of Cincinnati/Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and Westat-Rockville, Maryland during the study period, from 1985 to 2000. Regions with a wide range of family income and parental education within each race were chosen using census tract data [12]. The main conditions for admission were an entering age of 9 or 10 years, self-identification as Black or White girls, and ethnically consistent parents or guardians [12]. Participants provided their assent once parental or guardian approval was obtained in writing. The study was approved by institutional review committees from all partnering institutions. The observational research was overseen by a group of impartial observers. At the three clinical sites, the health biomarkers and dietary habits of Black and White adolescent girls were tracked yearly, from the ages of 9 and 10 to 19. Health risk factors related to cardiovascular disease and obesity were recorded, including race, dietary factors, and other aspects of general health-related factors. The NGHS also sought to identify significant modifiable health risk factors to inform future disease prevention efforts. To identify quantitatively significant covariates for the prediction of diastolic blood pressure (DBP) and systolic blood pressure (SBP), 17 health risk factors were chosen based on previous longitudinal NGHS studies: age, potassium, calcium, polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA), monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA), sucrose, sodium, starch, total carbohydrates, dietary cholesterol, waist circumference, magnesium, dietary fiber, body mass index (BMI), caffeine, total fat, and total calorie intake [13,14].

2.2. Handling Missing Data

Because repeated assessments accumulate incomplete fields, we first evaluated the missing data mechanism. Prior NGHS work often proceeded under MCAR-type assumptions [13,14]. We formally tested MCAR using Little’s test and found strong evidence against MCAR (p < 0.0001) [15,16]. To preserve sample size while avoiding model extrapolation, we used k-nearest neighbors (KNN) imputation for incomplete predictors. Continuous predictors were z-scored prior to distance calculation; distances were computed with Euclidean distance over the predictor set, excluding the outcomes (SBP, DBP). We imputed within analysis strata (overall, Black, White) to respect distributional differences by race. We set k = 10 and conducted a small sensitivity analysis with k ∈ {5, 10, 15}; variable importance rankings and model performance were unchanged across these values. We report per-variable missingness in a Supplementary Table S1. We did not use “convergence” as a diagnostic for KNN (which is a deterministic procedure given the data and k); instead, we assessed robustness via the k-sensitivity, described above.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

In this analysis, a random forest was combined with a linear mixed-effects framework (RF-LME) to counteract the lack of flexibility induced by the parametric assumptions of linear mixed-effects models [9]. Moreover, random forest can produce accurate results without the risk of overfitting, even when trained on a large number of random samples [11]. Because of the stochastic properties of random forests, model stability and interpretability can be challenging. To promote stability, a random forest of 10,000 trees was used [17]. Additionally, separate iterations containing tree sizes of 200, 400, 800, 1600, 3200, and 6400 were computed to demonstrate the increase in result stability and variance reduction as tree size increases [18]. Analyses were repeated across multiple random seeds to summarize variability. Out of all participants, a portion of the data (40%) was randomly selected for training to reduce the computational cost of repeated LOCO refits; performance was evaluated using out-of-bag (OOB) error for the remaining 60% test data. Models were fit for the whole cohort and separately within Black and White participants using the same procedure. To account for repeated measures, we included participant-level random intercepts so that within-participant correlation across visits is modeled while allowing non-linear covariate effects to be learned by the forest.

Analyses were conducted in R (version 4.3.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Mixed-effects models were implemented using the lme4 package, and forest components with the leave-one-covariate-out (LOCO) procedure were coded via custom R scripts. Figures were generated with ggplot2. On our R (v4.3.1) workstation, the full LOCO sweep, refitting forests across 17 covariates × 3 strata (overall, Black, White) × 7 forest sizes (200–20,000 trees) with OOB evaluation, required approximately five days of wall-clock time.

It has been demonstrated that p-values are susceptible to misinterpretation, particularly when dealing with increasing numbers of sample size and covariates [19]. Moreover, they are incapable of evaluating the predictive contributions of covariates to outcome variables [20]. To avoid these limitations, we incorporated a leave-one-covariate-out (LOCO) approach within random forests to ensure reproducible and interpretable findings. Developed by Lei et al. (2018), LOCO is a method of calculating variable importance that is similar to leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV), except that it leaves out a covariate, rather than an observation [21]. Because SBP and DBP are continuous outcomes, model performance is measured using mean absolute error (MAE). For each covariate, we compared the benchmark model (with all 17 covariates) against a partial model excluding that covariate and defined variable importance as the increase in error when the covariate was left out, as follows:

Equivalently, is the mean increase in MAE attributable to excluding covariate j. Variables were ranked by the mean across repetitions. We also report the standard deviation (SD) of across repetitions and tree sizes as an uncertainty/stability measure; SD is not used for ranking.

To summarize results, we present error bar plots (Figure 1 and Figure 2) in which point heights are mean and error bars are the SD of across repetitions (and, where shown, tree sizes). A model using 20,000 trees was also run, and it demonstrated stability, with negligible differences compared to size 10,000 trees. We used the criteria that covariates with the largest mean have the greatest impacts on model performance [22].

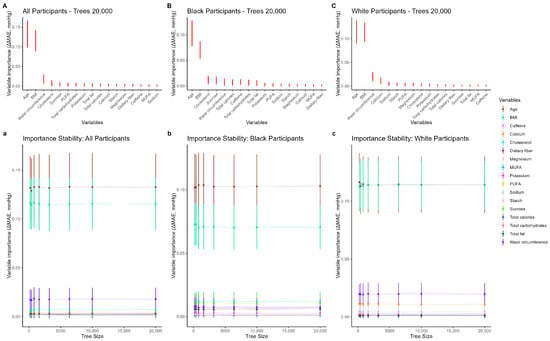

Figure 1.

Leave-one-covariate-out (LOCO) variable importance for diastolic blood pressure (DBP). Panels (A–C) show mean for each covariate, where ; taller points indicate greater importance. Error bars are SD () across repetitions (and, where shown, tree sizes) and represent uncertainty/stability, not the ranking criterion. Panels (a–c) display how importance estimates stabilize as the number of trees increases. PUFA: polyunsaturated fatty acid; MUFA: monounsaturated fatty acid.

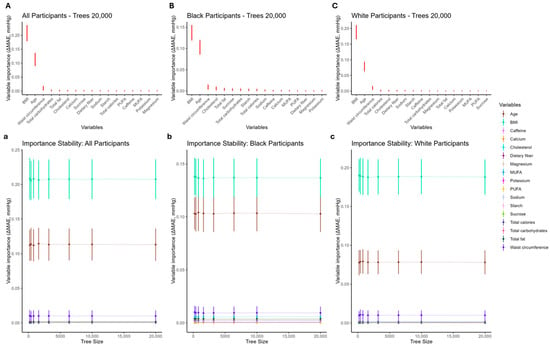

Figure 2.

Leave-one-covariate-out (LOCO) variable importance for systolic blood pressure (SBP). Panels (A–C) show mean for each covariate, where ; taller points indicate greater importance. Error bars are SD () across repetitions (and, where shown, tree sizes) and represent uncertainty/stability, not the ranking criterion. Panels (a–c) display how importance estimates stabilize as the number of trees increases. PUFA: polyunsaturated fatty acid; MUFA: monounsaturated fatty acid.

3. Results

A total of 2379 female adolescent participants were included in this analysis. The mean baseline age was 10 years; 51% were Black and 49% were White (Table 1). Baseline characteristics stratified by race are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics table containing health markers and dietary habits of Black and White National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Growth and Health Study participants at the time of enrollment.

For diastolic blood pressure (DBP), Figure 1 (panels A–C) shows variable importance from the RF-LME models using a leave-one-covariate-out approach, where importance is defined as the increase in mean absolute error (MAE) when a covariate is omitted. In the overall cohort (Figure 1A), the five most important variables were age, BMI, waist circumference (first measured at visit 2), total carbohydrates, and total fat. Lower-ranking dietary variables were similar to one another and well below the top predictors. Rankings were stable for forests with at least 6400 trees; age consistently outranked BMI across tree sizes, with differences narrowing as tree counts increased (Table 2). In race-stratified analyses (Figure 1B,C), patterns were similar: age and BMI dominated in both groups, with waist circumference and diet variables (notably dietary cholesterol and sucrose) contributing next. Electrolytes such as sodium and potassium, along with caffeine, were among the lowest-ranked predictors across tree sizes. Error bars in all panels reflect the standard deviation of the increase in MAE across repetitions (and, where shown, tree sizes).

Table 2.

Mean and SD () for DBP models by tree count (LOCO variable importance) Variables are ranked by mean ΔMAE across repetitions. SD () is reported as an uncertainty/stability measure and is not used for ranking. Abbreviations: BMI: body mass index; WC: waist circumference; CL: dietary cholesterol; SUC: sucrose; CAL: total calories; PUFA: polyunsaturated fatty acid; CARB: total carbohydrates; Ca: calcium; ST: starch; TF: total fat; K: potassium; CAF: caffeine; Mg: magnesium; DF: dietary fiber; MUFA: monounsaturated fatty acid; Na: sodium. Columns for each tree size are “ΔMAE (mean)” and “SD (ΔMAE)”.

For systolic blood pressure (SBP), Figure 2 (panels A–C) presents the corresponding importance rankings. In the overall cohort (Figure 2A), the top five variables were BMI, age, waist circumference, total calories, and cholesterol. For Black participants (Figure 2B), BMI and age were again the most influential, followed by dietary cholesterol, total fat, and sucrose. For White participants (Figure 2C), BMI and age led, with waist circumference, total calories, and dietary cholesterol completing the top tier. As with DBP, variables outside the top tier clustered closely together in importance. Rankings were already stable by 3200–6400 trees; increasing the number of trees primarily reduced uncertainty (narrower error bars), rather than changing variable ordering (Table 3). Taken together, age and adiposity (BMI and waist circumference) were the dominant predictors of blood pressure, with several dietary variables contributing modestly. The sodium and caffeine variables consistently showed low importance for DBP, whereas, for SBP, the energy-related macronutrient measures (total carbohydrates, total fat) entered the top tier in the overall cohort and the Black subgroup.

Table 3.

Mean and SD () for SBP models by tree count (LOCO variable importance) Variables are ranked by mean ΔMAE across repetitions. SD () is reported as an uncertainty/stability measure and is not used for ranking. Abbreviations: BMI: body mass index; WC: waist circumference; CL: dietary cholesterol; SUC: sucrose; CAL: total calories; PUFA: polyunsaturated fatty acid; CARB: total carbohydrates; Ca: calcium; ST: starch; TF: total fat; K: potassium; CAF: caffeine; Mg: magnesium; DF: dietary fiber; MUFA: monounsaturated fatty acid; Na: sodium. Columns for each tree size are “ΔMAE (mean)” and “SD (ΔMAE)”.

4. Discussion

Using a random forest–linear mixed-effects (RF-LME) framework with a leave-one-covariate-out (LOCO) importance metric, we balanced model flexibility with interpretability for longitudinal prediction of adolescent blood pressure. In this predictive setting, variable importance was defined as the increase in mean absolute error when a covariate was omitted, and uncertainty was summarized by the standard deviation of that increase across repetitions and tree sizes. This design allowed us to evaluate, within the overall cohort and by race, the relative predictive contributions of 17 a priori covariates to systolic (SBP) and diastolic (DBP) blood pressure, while keeping the presentation focused on reproducible rankings, rather than inferential coefficients.

For DBP in the full cohort, the highest-ranking predictors were age, BMI, waist circumference, dietary cholesterol, and sucrose. The prominent roles of BMI for both DBP and SBP are consistent with prior pediatric and adolescent findings linking adiposity to blood pressure [23,24,25]. Waist circumference has also been shown to be a strong predictor of blood pressure, even among adolescents with normal BMI [26], aligning with its high predictive contribution here. Although evidence on dietary cholesterol and adolescent blood pressure is mixed [27,28], our NGHS analysis indicates that dietary cholesterol contributed meaningfully to predictive accuracy, an observation that expands upon earlier NGHS work [12,13,14]. The importance of sucrose in our DBP models is also consistent with research implicating sugars in adolescent blood pressure [29,30].

Race-stratified DBP models showed broadly similar patterns, with age and BMI consistently dominating, followed by waist circumference and selected dietary factors. Reports in the literature have emphasized potential roles for calcium and sodium in adolescent blood pressure; for example, increased dairy intake has been associated with lower SBP among White adolescents [31], and higher calcium intake has been linked to SBP differences in younger children [32]. Sodium is widely cited as deleterious for blood pressure [33], yet NGHS intake measures may under-capture discretionary salt use (e.g., at the table or in food preparation), which can attenuate predictive value [13]. Moreover, population differences in sodium sensitivity have been described [34], which may contribute to heterogeneity across cohorts. Within our predictive framework, sodium and caffeine ranked among the lower-importance variables for DBP, whereas adiposity and a small set of dietary factors carried most of the predictive signal. The stability of the LOCO-based importance rankings across tree sizes that we observed is consistent with previous work on random forest variable-importance stability [10,18,35].

For SBP, the overall cohort’s top predictors were BMI and age, followed by waist circumference, total calories, and cholesterol. In subgroup analyses, BMI, age, and waist circumference again dominated: among Black participants, dietary cholesterol and total fat rounded out the top tier; among White participants, waist circumference, total carbohydrates, and total fat joined BMI and age. These patterns are compatible with prior work suggesting a role for carbohydrate intake in blood pressure regulation [36,37], and with studies highlighting the relevance of total fat in adolescent blood pressure [38,39]. Notably, variables outside the top tier clustered closely in importance, indicating that the macronutrient and adiposity signals dominated SBP prediction in this cohort.

Across outcomes and strata, increasing the number of trees primarily reduced uncertainty in the importance estimates and produced stable rankings by approximately 3200–6400 trees. This behavior is consistent with the known stability gains of larger forests [10,18,35], and it supports the practical choice to probe stability across tree sizes as part of model quality control.

This study has limitations. The NGHS sample comprises female adolescents identifying as Black or White, which constrains generalizability; future work in other populations is needed to broaden inference. The LOCO procedure requires repeated refitting, which can be computationally intensive as the number of covariates grows; pragmatically, focusing on a prespecified, study-motivated covariate set can balance scope and feasibility. We quantified predictive contribution using mean absolute error; while this is appropriate for continuous outcomes and directly tied to model performance, LOCO importance reflects predictive value, rather than causal effect. Finally, beyond average SBP and DBP, it may be informative to examine extreme quantiles using random forests with LOCO to assess whether the importance structure differs in the tails of the blood pressure distribution.

In conclusion, to identify quantitatively significant covariates, we evaluated the variable importance of 17 clinical variables and built a linear mixed-effects model integrated with a random forest, quantified using leave-one-covariate-out. Utilizing RF-LME models with LOCO, we presented a novel approach to validate the variable importance in predictive modeling. With this strategy, we were able to deliver easily interpretable and reproducible model results. Through a similar combination of variable importance measures with machine learning models, researchers could arrive at reliable and interpretable results in the validation of variable importance in predictive modeling.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/adolescents5040081/s1, Table S1: Per-variable missingness (overall and by race). Note that this missing data is based on 10 years follow-up data not only in baseline.

Author Contributions

R.J.L.: first draft of the manuscript and statistical analysis; M.C.: concept of the study and review and editing; M.K.A.: review and editing that significantly improved the manuscript; N.A. and A.F.R.: overall supervision, analysis plan, revision, and editing of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable as we did not produce any new data for this study. We used data from The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Growth and Health Study (NGHS). The data is available upon request from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of each of the participating sites.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was waived as this paper used secondary data from The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Growth and Health Study (NGHS).

Data Availability Statement

The data is available upon request from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA, https://biolincc.nhlbi.nih.gov/studies/nghs/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Whelton, P.K.; Carey, R.M.; Aronow, W.S.; Casey, D.E., Jr.; Collins, K.J.; Dennison Himmelfarb, C.; DePalma, S.M.; Gidding, S.; Jamerson, K.A.; Jones, D.W.; et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: Executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2018, 71, 1269–1324. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, J.H.; Hong, Y.M. Blood pressure trajectories from childhood to adolescence in pediatric hypertension. Korean Circ. J. 2019, 49, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Y. Tracking of blood pressure from childhood to adulthood: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Circulation 2008, 117, 3171–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twisk, J.W.; Kemper, H.C.; van Mechelen, W.; Post, G.B. Tracking of risk factors for coronary heart disease over a 14-year period: A comparison between lifestyle and biologic risk factors with data from the Amsterdam Growth and Health Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1997, 145, 888–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juhola, J.; Magnussen, C.G.; Viikari, J.S.A.; Kähönen, M.; Hutri-Kähönen, N.; Jula, A.; Lehtimäki, T.; Åkerblom, H.K.; Pietikäinen, M.; Laitinen, T.; et al. Tracking of serum lipid levels, blood pressure, and body mass index from childhood to adulthood: The Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. J. Pediatr. 2011, 159, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamoen, M.; Vergouwe, Y.; Wijga, A.H.; Heymans, M.W.; Jaddoe, V.W.V.; Twisk, J.W.R.; Raat, H.; A de Kroon, M.L. Dynamic prediction of childhood high blood pressure in a population-based birth cohort: A model development study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e023912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forouzanfar, M.H.; Afshin, A.; Alexander, L.T.; Anderson, H.R.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Biryukov, S.; Brauer, M.; Burnett, R.; Cercy, K.; Charlson, F.J.; et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016, 388, 1659–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellagatti, M.; Masci, C.; Ieva, F.; Paganoni, A.M. Generalized mixed-effects random forest: A flexible approach to predict university student dropout. Stat. Anal. Data Min. 2021, 14, 241–257. [Google Scholar]

- Krennmair, P.; Schmid, T. Flexible domain prediction using mixed effects random forests. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C Appl. Stat. 2022, 71, 1865–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genuer, R.; Poggi, J.-M.; Tuleau-Malot, C. Variable selection using random forests. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2010, 31, 2225–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, S.; Tran, T.Q.B.; Dominiczak, A.F. Artificial intelligence in hypertension: Seeing through a glass darkly. Circ. Res. 2021, 128, 1100–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Obesity and cardiovascular disease risk factors in black and white girls: The NHLBI Growth and Health Study. Am. J. Public Health 1992, 82, 1613–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obarzanek, E.; Wu, C.O.; Cutler, J.A.; Kavey, R.-E.W.; Pearson, G.D.; Daniels, S.R. Prevalence and incidence of hypertension in adolescent girls. J. Pediatr. 2010, 157, 461–467.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haskin, S.; Kimitei, S.; Chowdhury, M.; Rahman, A.K.M.F. Longitudinal predictive curves of health risk factors for American adolescent girls. J. Adolesc. Health 2022, 70, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, R.J.A. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1988, 83, 1198–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.M.; Zhao, P.; Yang, Y.H.; Wang, J.X.; Yan, H.; Chen, F.Y. Simulation study on missing data imputation methods for longitudinal data in cohort studies. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 2021, 42, 1889–1894. [Google Scholar]

- Tsipouras, M.G.; Tsouros, D.C.; Smyrlis, P.N.; Giannakeas, N.; Tzallas, A.T. Random forests with stochastic induction of decision trees. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 30th International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence (ICTAI), Volos, Greece, 5–7 November 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Behnamian, A.; Millard, K.; Banks, S.N.; White, L.; Richardson, M.; Pasher, J. A systematic approach for variable selection with random forests: Achieving stable variable importance values. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2017, 14, 1988–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cote, M.P.; Lubowitz, J.H.; Brand, J.C.; Rossi, M.J. Misinterpretation of P values and statistical power creates a false sense of certainty: Statistical significance, lack of significance, and the uncertainty challenge. Arthroscopy 2021, 37, 1057–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenland, S. Valid P-Values Behave Exactly as They Should: Some Misleading Criticisms of P-Values and Their Resolution With S-Values. Am. Stat. 2019, 73, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; G’Sell, M.; Rinaldo, A.; Tibshirani, R.J.; Wasserman, L. Distribution-free predictive inference for regression. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2018, 113, 1094–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Wang, M.; Xu, S.; Huang, Z.; Grant, P.W. The unsupervised feature selection algorithms based on standard deviation and cosine similarity for genomic data analysis. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 684100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chorin, E.; Hassidim, A.; Hartal, M.; Havakuk, O.; Flint, N.; Ziv-Baran, T.; Arbel, Y. Trends in adolescent obesity and the association between BMI and blood pressure: A cross-sectional study in 714,922 healthy teenagers. Am. J. Hypertens. 2015, 28, 1157–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mendalawi, M.D. Impact of body mass index on high blood pressure among obese children in the western region of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2018, 39, 426–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Mo, L.; Pang, Y. Hypertension in adolescents: The role of obesity and family history. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2021, 23, 2065–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazin, D.C.; da Luz Kaestner, T.L.; Olandoski, M.; Baena, C.P.; de Azevedo Abreu, G.; Kuschnir, M.C.C.; Bloch, K.V.; Faria-Neto, J.R. Association between abdominal waist circumference and blood pressure in Brazilian adolescents with normal body mass index. Glob. Heart 2020, 15, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, M.; Stamler, J.; Miura, K.; Brown, I.J.; Nakagawa, H.; Elliott, P.; Ueshima, H.; Chan, Q.; Tzoulaki, I.; Dyer, A.R.; et al. Relationship of dietary cholesterol to blood pressure: The INTERMAP study. J. Hypertens. 2011, 29, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, J.A.S.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Appel, L.J.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Meyer, K.A.; Petersen, K.; Polonsky, T.; Van Horn, L.; Arteriosclerosis, T.C.O.; et al. Dietary cholesterol and cardiovascular risk: A science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020, 141, e39–e53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhangi, M.A.; Nikniaz, L.; Khodarahmi, M. Sugar-sweetened beverages increase the risk of hypertension among children and adolescents: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, I.J.; Stamler, J.; Van Horn, L.; Robertson, C.E.; Chan, Q.; Dyer, A.R.; Huang, C.C.; Rodriguez, B.L.; Zhao, L.; Daviglus, M.L.; et al. Sugar-sweetened beverage, sugar intake of individuals, and their blood pressure: International study of macro/micronutrients and blood pressure. Hypertension 2011, 57, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DellaValle, D.M.; Carter, J.; Jones, M.; Henshaw, M.H. What is the relationship between dairy intake and blood pressure in black and white children and adolescents enrolled in a weight management program? J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e004593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillman, M.W. Inverse association of dietary calcium with systolic blood pressure in young children. JAMA 1992, 267, 2340–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.J.; Marrero, N.M.; Macgregor, G.A. Salt and blood pressure in children and adolescents. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2008, 22, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svetkey, L.P.; McKeown, S.P.; Wilson, A.F. Heritability of salt sensitivity in black Americans. Hypertension 1996, 28, 854–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yang, F.; Luo, Z. An experimental study of the intrinsic stability of random forest variable importance measures. BMC Bioinform. 2016, 17, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosner, B.; Cook, N.R.; Daniels, S.; Falkner, B. Childhood blood pressure trends and risk factors for high blood pressure: The NHANES experience 1988–2008. Hypertension 2013, 62, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unwin, D.J.; Tobin, S.D.; Murray, S.W.; Delon, C.; Brady, A.J. Substantial and sustained improvements in blood pressure, weight and lipid profiles from a carbohydrate restricted diet: An observational study of insulin-resistant patients in primary care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Evans, C.E.L.; Cade, J.E. Dietary fat intake and blood pressure in UK adolescents: A longitudinal study. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2018, 77, E209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinikoski, H.; Jula, A.; Viikari, J.; Rönnemaa, T.; Heino, P.; Lagström, H.; Jokinen, E.; Simell, O. Blood pressure is lower in children and adolescents with a low-saturated-fat diet since infancy: The Special Turku Coronary Risk Factor Intervention Project. Hypertension 2009, 53, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).