Abstract

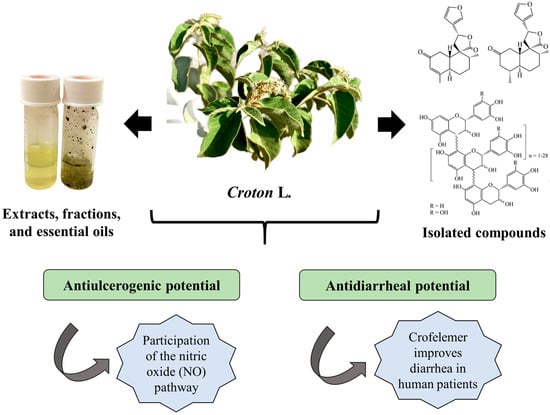

Gastrointestinal disorders negatively affect populations worldwide. Considering the side effects of synthetic drugs, natural products can be a safe and effective alternative to help treat gastric ulcers and diarrhea. In this context, the present study reviewed the antiulcerogenic and antidiarrheal activities of species of the genus Croton (Euphorbiaceae). The scientific documents were retrieved from different databases, covering publications from the first report on the topic in 1998 to October 2025. Although the genus Croton comprises approximately 1200 species, only 11 have been evaluated for their antiulcerogenic and antidiarrheal potential in in vivo and in vitro studies. Among the identified bioactive constituents, the diterpenes trans-dehydrocrotonin and trans-crotonin, isolated from Croton cajucara, demonstrated significant antiulcerogenic activity in several experimental models in vivo. Similarly, the compound crofelemer, isolated from the latex of the bark of Croton lechleri, has shown promising results in several clinical trials for the treatment of diarrhea. Furthermore, flavonoids including rutin and quercitrin have been detected in Croton campestris. Regarding gastroprotective mechanisms, evidence suggests that extracts and essential oils obtained from Croton species may act through the nitric oxide pathway, promoting an antiulcerogenic effect. Additional studies are needed to investigate the gastroprotective and antiulcerogenic potential of at least 17 Croton species used empirically in traditional medicine for the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders but still without scientific validation.

1. Introduction

Digestive tract diseases have a high global prevalence, representing an important cause of morbidity and mortality. These conditions not only cause significant suffering to patients but can also progress to potentially fatal conditions [1]. In 2019, the global burden of digestive diseases recorded an incidence rate of 95,582 cases per 100,000 person-years in 204 countries, which corresponded to approximately 7.3 billion new cases [2]. Among the most common gastrointestinal disorders are inflammatory bowel disease, gastric ulcers, Helicobacter pylori infections, colorectal cancer, diarrhea, constipation, and gastroesophageal reflux disease [3]. Estimates indicate that, in 2019, the global prevalence of peptic ulcers reached around 8 million cases, representing an increase of 25.82% compared to 1990 [4]. Although the global burden of diarrhea has decreased in recent decades, certain population groups, especially children under five and older adults over 60, continue to be disproportionately affected [5]. In 2021, it was reported that the global burden of diarrheal diseases in childhood remained considerably high, totaling approximately 25,190,229 cases [6].

Among the synthetic drugs most used in the treatment of gastric ulcers, omeprazole stands out. However, studies have indicated that prolonged use of this medication may be associated with adverse effects, including cardiovascular changes [7,8]. Similarly, loperamide, widely used in the management of diarrhea, has also been associated with adverse cardiac events [9]. Given these limitations, the search for effective natural therapeutic alternatives with a greater safety margin becomes relevant for the management of gastrointestinal disorders, such as gastric ulcers and diarrhea.

Several representatives of the Euphorbiaceae Juss. family have been widely studied due to their pharmacological potential, with emphasis on the genera Euphorbia L. [10,11,12,13], Jatropha L. [14,15], and Croton L. [16,17,18]. In traditional medicine, Croton species are widely used in the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders, such as gastritis and diarrhea, especially Croton urucurana Baill. [19,20], Croton blanchetianus Baill. [21,22], and Croton macrostachyus Hochst. ex Delile [23,24]. Consequently, the in vivo gastroprotective and antidiarrheal potential of Croton species has been widely documented [25,26,27]. Studies have shown that the antiulcerogenic mechanisms of products obtained from Croton campestris A.St.-Hil. [28,29] and Croton rhamnifolioides Pax & K.Hoffm. [30] involve the modulation of nitric oxide (NO) pathways. Furthermore, the diterpenes trans-dehydrocrotonin [31] and trans-crotonin [32] isolated from the bark of Croton cajucara Benth., demonstrated antiulcerogenic activity in several experimental models in vivo. The compound crofelemer, an oligomeric mixture of proanthocyanidins, isolated from the bark latex of Croton lechleri Müll.Arg., showed promising results in clinical trials aimed at treating diarrhea in human patients [33,34,35,36,37].

In this context, the present study aims to comprehensively review the available scientific evidence regarding the antiulcerogenic and antidiarrheal activities of species of the genus Croton, as well as to identify those used in traditional medicine for the treatment of gastrointestinal diseases, but which still lack detailed scientific investigation.

2. Methodology

2.1. Database Search

The review was conducted based on searches in Google Acadêmico, PubMed®, Scopus®, and Web of Science™ databases. The following descriptors and keyword combinations were used: “Croton AND gastrointestinal disorders”, “Croton AND digestive problems”, “Croton AND dysentery”, “Croton AND diarrhea”, “Croton AND antidiarrheal”, “Croton AND gastroprotection”, “Croton AND gastric ulcer”, “Croton AND antiulcer”, “Croton AND phytochemistry”, and “Croton AND acute toxicity”.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Original articles presenting experimental data on the gastroprotective and/or antidiarrheal potential of species of the genus Croton were included, covering publications from the first report by Brito et al. [31] to October 2025. Ethnobotanical studies describing the traditional use of Croton species for the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders were also considered. The exclusion criteria applied to secondary literature (review articles, e-books, and book chapters), academic dissertations (theses and monographs), and conference proceedings. Furthermore, studies were eliminated if they did not provide reliable experimental data or if species identification was only performed at the genus level [38]. The scientific nomenclature of the species was confirmed in the World Flora Online (WFO) database (https://wfoplantlist.org/ (accessed on 23 December 2025)). All chemical structures were generated using the ChemDraw Ultra 12.0 software.

2.3. Data Screening and Information Categorization

In total, 26 articles were analyzed that addressed antiulcerogenic and antidiarrheal activities, chemical constituents and acute toxicity of products obtained from Croton species. Additionally, 21 ethnomedicinal studies were included. The results were organized into four main categories: (1) Antiulcerogenic and antidiarrheal activities of Croton species; (2) Major and/or isolated compounds from Croton species; (3) Acute toxicity of Croton species; and (4) Croton species used in traditional medicine to treat gastrointestinal diseases.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Antiulcerogenic and Antidiarrheal Activities of Croton Species

A total of 11 Croton species with reports of antiulcerogenic and/or antidiarrheal activity were identified (Table 1). Gastroprotective activities were evaluated using different in vivo models, including gastric ulcers induced by indomethacin, ethanol, HCl/ethanol, histamine, reserpine, pylorus ligation, hypothermic restraint stress, and acetic acid. The antidiarrheal potential was investigated using castor oil-induced diarrhea models, intestinal transit tests, and in vitro fluid transport and intestinal signaling assays. The leaves and stem bark were the most used parts to obtain extracts, fractions, and essential oils. Furthermore, compounds isolated from species of the genus Croton, such as trans-dehydrocrotonin and trans-crotonin from C. cajucara, crofelemer from C. lechleri, and polyalctic acid from C. reflexifolius, were also investigated for their antiulcer and antidiarrheal activity (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Antiulcerogenic and antidiarrheal activity of products obtained from Croton species and possible mechanism of action.

Croton cajucara stood out as the most investigated species. According to Hiruma-Lima et al. [39], the essential oil of the bark administered orally to mice and rats (100 mg/kg) showed significant inhibition of the formation of gastric lesions induced by pylorus ligation (87%), ethanol (86%), hypothermic stress (47%), and indomethacin (47%). Subsequent studies confirmed the gastroprotective effect in different models [40,41]. It was reported that oral administration of C. cajucara bark essential oil at a dose of 100 mg/kg for 14 consecutive days accelerated the healing of acetic acid-induced gastric ulcers in rats, with healing rates of 32.3% compared to the control group [41]. The proposed mechanism involves increased expression of epidermal growth factor (EGF) and somatostatin, as well as reduced plasma gastrin levels [42].

Other species also demonstrated gastroprotective effects, such as C. zehntneri and C. rhamnifolioides, whose essential oils significantly reduced ethanol-induced gastric lesions in mice. The essential oil of C. zehntneri, for example, at doses of 30, 100 and 300 mg/kg inhibited the areas of gastric lesions in mice by up to 39, 78 and 96%, respectively [43]. According to Vidal et al. [30], oral administration of the essential oil from the leaves of C. rhamnifolioides (200 mg/kg) significantly reduced absolute ethanol-induced gastric lesions in mice. The observed effects were attributed to the modulation of NO-dependent pathways and opioid receptors.

Similarly, the participation of the NO pathway in antiulcerogenic effects has also been reported for other plant extracts. A study by Júnior et al. [28] observed that the hydroalcoholic extract from C. campestris leaves provided a protective effect against acute gastric injury induced in mice by absolute ethanol, acidified ethanol, or indomethacin. This discovery indicates that the cytoprotective action of the extract occurs through the potentiation of the NO/intracellular guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (cGMP) pathway. Júnior et al. [29] reported that the antiulcerogenic effect of the hydroalcoholic extract of C. campestris roots depends on the NO and prostaglandin pathways, possibly due to its ability to stimulate NO synthesis and activate endogenous prostaglandin production.

At doses of 50, 100 and 250 mg/kg, the methanolic extract of C. urucurana bark administered to male Wistar rats significantly reduced ethanol-induced gastric lesions by up to 70.25, 95.40 and 98.71%, respectively [44]. In the indomethacin model, doses of 50, 100, and 250 mg/kg of this extract significantly reduced gastric damage by up to 67.85, 82.50, and 71.01%, respectively. The gastroprotective effect of C. urucurana extract was not related to endogenous NO activity, but was dependent on sulfhydryl compounds, which increased mucus production and decreased gastric acidity [44]. According to Dantas et al. [26], a reduction of up to 45.56, 51.56 and 69.45% was observed in ethanol-induced gastric lesions in mice pretreated with spray-dried extract of C. blanchetianus at doses of 50, 100 and 200 mg/kg, respectively. In this study, the authors did not evaluate the possible mechanisms of action involved with the gastroprotective action.

In addition to antiulcerogenic activity, some Croton species have also been evaluated for their antidiarrheal potential. Degu et al. [45] conducted a study using the castor oil-induced diarrhea model in mice and found that the chloroform fraction (300, 400, and 500 mg/kg) and the methanolic fraction (400 and 500 mg/kg) derived from C. macrostachyus leaves significantly mitigated diarrhea. This effect, demonstrated by a delayed onset of diarrhea and decreased stool frequency, was observed to be dose-dependent. On the other hand, the aqueous fraction of this plant did not show significant antidiarrheal activity. Furthermore, it was observed that the chloroform fraction of C. macrostachyus significantly inhibited the gastrointestinal transit time of charcoal flour in mice at doses of 300, 400 and 500 mg/kg compared to the control [45]. Oral administration of the ethanolic extract of aerial parts of C. grewioides (7.81, 15.62, 31.25, 62.5, 125 and 250 mg/kg) in mice significantly and dose-dependently inhibited the accumulation of intestinal fluid induced by castor oil. The inhibition values were 9.9, 14.7, 31.7, 45.5, 64.6, and 67.5%, respectively [46].

Table 1.

Antiulcerogenic and antidiarrheal properties of Croton species.

Table 1.

Antiulcerogenic and antidiarrheal properties of Croton species.

| Species | Part of the Plant | Products | Doses | Methods | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Croton blanchetianus Baill. | Leaves | Spray-drier extract, effervescent pre-formulation | 50, 100 and 200 mg/kg | Ethanol-induced ulcer | At a dose of 200 mg/kg, the spray-drier extract and the effervescent pre-formulation reduced damage to the gastric mucosa of mice by up to 69.45 and 82.17%, respectively. | Dantas et al. [26] |

| Croton cajucara Benth. | Barks | trans-Dehydrocrotonin | 100 mg/kg | Shay ulcer, indomethacin-induced ulcer, ethanol-induced ulcer, restraint-hypothermic stress ulcer | The observed antiulcerogenic effect may be related to the increase in mucosal defense mechanisms, such as the production of prostaglandins. | Brito et al. [31] |

| Stem bark | Essential oil | 100 mg/kg | HCl/ethanol-induced ulcer, indomethacin-induced ulcer, hypothermic restraint stress ulcer, Shay ulcer | The essential oil exhibited a significant antiulcerogenic effect, probably due to increased mucosal defense mechanisms, such as prostaglandin production. | Hiruma-Lima et al. [39] | |

| Stem bark | Essential oil | 100 mg/kg | Shay ulcer, HCl/ethanol-induced ulcer, restraint hypothermic stress ulcer | The essential oil prevented gastric lesions induced by hypothermic restraint stress and HCl/ethanol; furthermore, in the pyloric ligation model, a significant increase in pH and gastric volume was observed. | Hiruma-Lima et al. [40] | |

| Stem bark | Essential oil | 100 mg/kg | Acetic acid-induced ulcer | The gastroprotective effects of the essential oil resulted mainly from increased PGE2 release and gastric mucus formation. | Hiruma-Lima et al. [41] | |

| Bark | trans-Crotonin | 100 mg/kg | HCl/ethanol-induced ulcer, indomethacin-induced ulcer, hypothermic restraint-stress ulcer, Shay ulcer | The isolated compound showed a significant antiulcerogenic effect probably related to its anti-secretory and gastroprotective properties. | Hiruma-Lima et al. [32] | |

| Stem barks | Essential oil | 100 mg/kg | Shay ulcer, indomethacin-induced ulcer | The antiulcerogenic mechanism of the essential oil is related to increased production of PGE2 and mucus. | Paula et al. [47] | |

| Stem barks | Essential oil | 100 mg/kg | Ethanol-induced ulcer, acetic acid-induced ulcer | The antiulcerogenic activity of the essential oil was mediated by increased somatostatin secretion and expression of Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF) mRNA. | Paula et al. [42] | |

| Stem barks | Essential oil | 100 mg/kg | Ethanol-induced ulcer | The essential oil prevented gastric ulcers, reduced epithelial desquamation, and glandular damage. | Rozza et al. [48] | |

| Leaves | Polysaccharide fraction (25R) | 0.02 and 0.2 mg/kg | Ethanol-induced ulcer | The polysaccharide fraction was able to reduce gastric ulcers in rats, preserving mucus and glutathione (GSH) levels. | Nascimento et al. [49] | |

| Croton campestris A.St.-Hil. | Leaves | Hydroalcoholic extract | 50, 75, 125, 250, 500 and 750 mg/kg | Ethanol-induced ulcer, HCl/ethanol-induced ulcer, indomethacin-induced ulcer | The gastroprotective action of the extract in all gastric ulcer models evaluated may be involved with the nitric oxide pathway. | Júnior et al. [28] |

| Roots | Hydroalcoholic extract | 50, 75, 125, 250, 500 and 750 mg/kg | Ethanol-induced ulcer, HCl/ethanol-induced ulcer, indomethacin-induced ulcer | The antiulcerogenic activity of the extract seems to be mediated by the stimulation of endogenous prostaglandins and release of nitric oxide that lead to an increase in microcirculation. | Júnior et al. [29] | |

| Croton grewioides Baill. (Syn. Croton zehntneri) | Leaves | Essential oil | 10, 30, 100 and 300 mg/kg | Ethanol-induced ulcer, indomethacin-induced ulcer, cold-restraint stress-induced ulceration | The antiulcerogenic effect of essential oil may be related to the production of gastric wall mucus, an important gastroprotective factor. | Coelho-de-Souza et al. [43] |

| Aerial parts | Ethanolic extract | 7.81–500 mg/kg | Castor oil-induced diarrhea, intestinal transit | The extract showed a significant antidiarrheal effect in mice with a reduction in the frequency and number of liquid feces, in addition to reducing intestinal fluid. | Silva et al. [46] | |

| Leaves | Essential oil | 200 and 400 mg/kg | Ethanol-induced ulcer | At doses of 200 and 400 mg/kg, the essential oil inhibited gastric lesions in mice by up to 38.20 and 68.27%, respectively. | Leite et al. [50] | |

| Croton kinondoensis G.W.Hu, Ngumbau & Q.F.Wang | Leaves | Dichloromethane-methanol extract | 100, 200 and 400 mg/kg | Castor oil-induced diarrhea | Although not as potent as the standard drug loperamide, the extract exhibited moderate antidiarrheal effects. | Noor and Terefe [27] |

| Croton lechleri Müll.Arg. | Bark latex | Crofelemer | 1.5–500 µM | In vitro models of intestinal fluid transport and signaling processes | The cellular antisecretory action of crofelemer seems to involve two distinct Cl– channel targets on the luminal membrane of epithelial cells lining the intestine. | Tradtrantip et al. [51] |

| Croton macrostachyus Hochst. ex Delile | Root | Hydromethanolic extract, aqueous fraction, ethyl acetate fraction, chloroform fraction | 100, 200 and 400 mg/kg | Pyloric ligation-induced ulcer, HCl/ethanol-induced ulcer | The hydromethanolic extract exhibited significant antiulcer activity. The chloroform fraction also demonstrated efficacy, while the aqueous fraction showed no antiulcer activity. | Mekonnen et al. [25] |

| Leaves | Chloroform fraction, methanolic fraction, aqueous fraction | 300, 400, 500 and 1000 mg/kg | Castor oil-induced diarrhea | The chloroform and methanol fractions significantly delayed the onset of diarrhea, reduced stool frequency and weight. While the aqueous fraction did not show a significant effect. | Degu et al. [45] | |

| Croton reflexifolius Kunth | Leaves | Polyalthic acid | 30 mg/kg | Ethanol-induced ulcer | The gastroprotective mechanism of the isolated compound involved the participation of nitric oxide and endogenous sulfhydryl groups. | Reyes-Trejo et al. [52] |

| Croton rhamnifolioides Pax & K.Hoffm. | Leaves | Essential oil | 100, 200 and 400 mg/kg | Ethanol-induced ulcer, HCl/ethanol-induced ulcer, indomethacin-induced ulcer | The essential oil showed gastroprotective activity through mechanisms involving the participation of the nitric oxide and opioid pathways. | Vidal et al. [30] |

| Croton urucurana Baill. | Bark | Methanolic extract | 50, 100 and 250 mg/kg | Ethanol-induced ulcer, indomethacin-induced ulcer, acetic acid-induced gastric ulcer | The antiulcerogenic potential of the extract may involve sulfhydryl compounds, increasing mucus production and reducing gastric acidity. | Cordeiro et al. [44] |

| Bark | Red sap | 400, 600 and 800 mg/kg | Castor oil-induced diarrhea, intestinal transit | The red sap caused marked inhibition of the diarrheal response and significantly inhibited intestinal transit. There was no participation of endogenous opioids in its mechanism. | Gurgel et al. [53] | |

| Croton zambesicus (Croton gratissimus var. gratissimus) | Leaves | Essential oil | 5 and 10 mg/kg | Indomethacin-induced gastric ulcer | Low antiulcerogenic potential | Akinlolu et al. [54] |

| Leaves | Methanolic extract | 250 and 500 mg/kg | Indomethacin-induced gastric ulcer | Low antiulcerogenic potential | Akinlolu et al. [54] | |

| Leaves | Ethanolic extract | 200, 400 and 600 mg/kg | Indomethacin-induced ulcer, ethanol-induced ulcer, histamine-induced ulcer | The extract significantly inhibited ulcers induced in rats in all models evaluated. | Okokon et al. [55] | |

| Root | Ethanolic extract | 27, 54 and 81 mg/kg | Indomethacin-induced ulcer, ethanol-induced ulcer, reserpine-induced ulcer | The extract showed significant dose-dependent effects against the different gastric ulcer models evaluated. | Okokon and Nwafor [56] |

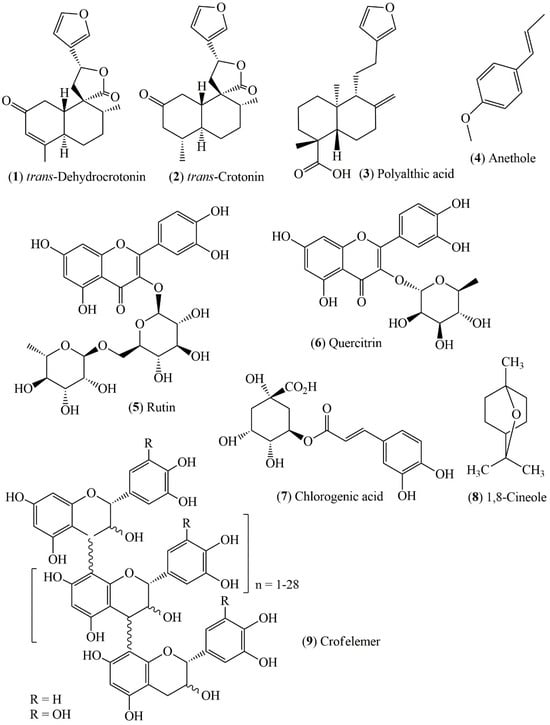

3.2. Major and/or Isolated Compounds from Croton Species

Although 26 studies have reported the antiulcerogenic and antidiarrheal potential of species of the genus Croton, only seven have investigated the chemical composition or isolated bioactive compounds from these plants. A total of nine substances belonging to the classes of diterpenes, phenylpropanoids, flavonoids, phenolic compounds, monoterpenes, and oligomeric proanthocyanidins were identified (Figure 2 and Table 2). Among these compounds, the diterpenes trans-dehydrocrotonin [31], trans-crotonin [32], and polyalctic acid [52], isolated from C. cajucara and C. reflexifolius, demonstrated significant antiulcerogenic activity in different in vivo models.

Figure 2.

Compounds from Croton species with antiulcerogenic and antidiarrheal potential. Structures drawn in ChemDraw Ultra 12.0 software.

According to Brito et al. [31], oral administration of 100 mg/kg of trans-dehydrocrotonin, isolated from the bark of C. cajucara, inhibited the formation of gastric lesions induced by stress due to hypothermic restraint, ethanol, and pylorus ligation in male Wistar rats. The best gastroprotective effect was observed in gastric ulcer models induced by hypothermic stress (64.8%) and ethanol (54%). The mechanism of gastroprotective action of polyalctic acid, isolated from the leaves of C. reflexifolius, was evaluated by Reyes-Trejo et al. [52]. In this study, concomitant administration of L-NAME (Nω-Nitro-L-arginine methyl ester) abrogated the gastroprotective effect of polyalctic acid, as well as that of the positive control carbenoxolone, suggesting that the nitric oxide (NO) pathway is directly involved in the gastroprotection induced by this diterpene and carbenoxolone.

The antiulcerogenic potential of anethole, a phenylpropanoid, has also been reported in the literature [43]. In a model of ethanol-induced gastric ulcer, anethole administered at doses of 30, 100 and 300 mg/kg promoted reductions of 42, 75 and 87%, respectively, in the injured area. In an indomethacin-induced ulcer model, the same doses reduced gastric lesions by 36, 69 and 85%, respectively. These authors suggested that anethole increases the production of gastric mucus, a fundamental factor for protecting the stomach mucosa. According to Yu et al. [57], trans-anethole attenuated lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammation by suppressing the TLR4/NF-κB pathway in intestinal epithelial cells (IEC-6), which may also contribute to its protective role in the gastric mucosa. In addition, anethole has been reported to inhibit the growth of multidrug-resistant strains of Vibrio cholerae, an etiological agent of cholera [58]. These findings indicate that anethole isolated from Croton zehntneri may represent a promising alternative for the treatment of gastric ulcer and diarrheal diseases.

The compound crofelemer isolated from the bark latex of C. lechleri [51], has been widely studied in randomized clinical trials due to its antidiarrheal properties [33,34,35,36,37]. In HIV-seropositive patients on stable antiretroviral therapy, oral administration of 125 mg crofelemer twice daily resulted in a significant reduction in the frequency of watery bowel movements and improvement in daily stool consistency, when compared with placebo [36]. Crofelemer showed low systemic absorption, good tolerability, and a safety profile similar to placebo [36]. In a phase II clinical study conducted by Pohlmann et al. [37], the use of crofelemer (125 mg, orally, twice daily) was evaluated in the prevention of chemotherapy-induced diarrhea in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer treated with trastuzumab, pertuzumab, and taxane. The results demonstrated that patients who received crofelemer were 1.8 times more likely to experience clinical improvement and had a lower frequency of watery diarrhea compared to the control group.

Regarding its mechanism of action, crofelemer acts through dual inhibition of fluid and chloride secretion mediated by the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) and calcium-activated chloride channels (CaCCs) [33]. In addition, crofelemer may be highly effective against diarrhea caused by certain bacterial species, including Vibrio cholerae and Escherichia coli. These pathogens produce enterotoxins that increase the production of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), which stimulates the CFTR chloride channel and consequently enhances chloride and fluid secretion [59].

Table 2.

Major and/or isolated compounds from Croton species with antiulcerogenic and antidiarrheal potential.

Table 2.

Major and/or isolated compounds from Croton species with antiulcerogenic and antidiarrheal potential.

| Majority or Isolated Compound | Class | Species | Activity of the Compound Reported in the Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) trans-Dehydrocrotonin | Diterpene | Croton cajucara [31] | Antiulcerogenic activity [31,60] |

| (2) trans-Crotonin | Diterpene | Croton cajucara [32] | Antiulcerogenic activity [32] |

| (3) Polyalthic acid | Diterpene | Croton reflexifolius [52] | Antiulcerogenic activity [52] |

| (4) Anethole | Phenylpropanoid | Croton zehntneri [43] | Antiulcerogenic activity [43] |

| (5) Rutin | Flavonoid | Croton blanchetianus [26] | Antiulcerogenic activity [61,62], antidiarrheal activity [63,64] |

| (6) Quercitrin | Flavonoid | Croton campestris [29] | Antidiarrheal activity [65,66] |

| (7) Chlorogenic acid | Phenolic compound | Croton campestris [29] | Antiulcerogenic activity [67,68,69] |

| (8) 1,8-Cineole | Monoterpene | Croton rhamnifolioides [30] | Antiulcerogenic activity [70,71], antidiarrheal activity [72] |

| (9) Crofelemer | Oligomeric proanthocyanidin | Croton lechleri [51] | Antidiarrheal activity [51] |

3.3. Acute Toxicity of Croton Species

Several studies have demonstrated the biological safety of extracts and essential oils obtained from Croton species with gastroprotective and antidiarrheal potential. According to Hiruma-Lima et al. [40], oral and intraperitoneal administration of the essential oil extracted from the bark of C. cajucara in mice showed LD50 values of 9260 and 680 mg/kg, respectively. Similarly, Vidal et al. [30] reported that oral administration of the essential oil from the leaves of C. rhamnifolioides at doses lower than 2000 mg/kg did not cause mortality or evident clinical signs of toxicity, indicating an LD50 higher than 2000 mg/kg and, therefore, low acute toxicity.

Cordeiro et al. [44] observed that the single administration of 2000 mg/kg of the methanolic extract of C. urucurana bark by gavage in rats did not cause changes in food consumption, water intake or behavior (tremors, convulsions, salivation, diarrhea, lethargy or sleep) during 14 days of observation. Consistently, Júnior et al. [28] reported the absence of signs of acute toxicity in Swiss mice treated orally with the hydroalcoholic extract of C. campestris leaves, whose LD50 was estimated as greater than or equal to 5000 mg/kg. Similarly, Silva et al. [46] found that doses of 2500 and 5000 mg/kg of the ethanolic extract of the aerial parts of C. grewioides administered orally did not induce behavioral changes or mortality in male and female mice. However, intraperitoneal administration of 2000 mg/kg resulted in lethality in all females evaluated, indicating dependence on the route of exposure [46].

The acute toxicity of C. macrostachyus fractions and extracts has also been extensively investigated. Degu et al. [45] reported that the chloroformic, methanolic and aqueous fractions of the leaves, administered at doses of 2000 and 5000 mg/kg, did not cause mortality or clinical signs of toxicity, such as lacrimation, anorexia, tremors, piloerection, salivation or diarrhea during the initial 24 h and over the subsequent 14 days, suggesting a LD50 greater than 5000 mg/kg. Similar results were described by Mekonnen et al. [25], who observed no mortality in mice treated with 2000 mg/kg of the hydromethanolic extract of C. macrostachyus root during the same experimental period.

In the case of the spray-dried extract of C. blanchetianus, Dantas et al. [26] observed that, in the first 30 s after a single oral administration of 2000 mg/kg, the animals showed aggressive behavior, agitation, stereotyped movements, itching, and reflux, possibly associated with the odor or taste of the extract. However, no changes were detected in body weight gain, water and food consumption in relation to the control group over 14 days. Hematological and biochemical parameters also remained within normal physiological values [26].

Taken together, this evidence indicates that products derived from Croton species have low acute toxicity and are biologically safe when administered orally at doses equal to or greater than 2000 mg/kg in rodents. However, further toxicokinetic and toxicological investigations are still needed to confirm the safety of using these preparations in pharmacological or therapeutic applications.

3.4. Croton Species Used in Traditional Medicine to Treat Gastrointestinal Diseases

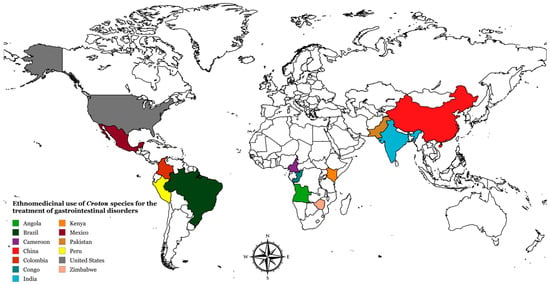

As mentioned in Section 3.1, to date, only 11 species of the genus Croton have been evaluated for their antiulcerogenic and antidiarrheal potential in in vivo and in vitro models. However, in traditional medicine, the number of species of this genus used in the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders is substantially greater, although most still lack scientific validation regarding their gastroprotective and antidiarrheal activities. According to ethnobotanical and ethnopharmacological surveys, although scientific validation is lacking, at least 17 species of Croton are popularly used to treat various digestive conditions, including stomach ache, upset stomach, diarrhea, indigestion, internal ulcers, gastritis, belly ache, colitis, constipation, swollen stomach, and dysentery (Table 3). These plants are used by traditional communities in countries in South America, North America, Asia, and Africa (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Ethnomedicinal use of Croton species for the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders in different countries. Created with mapchart.net.

Among these species, C. mubango Müll.Arg. stands out for its widespread use in countries on the African continent, such as Congo [73,74] and Angola [75]. On the other hand, C. sonderianus (=C. jacobinensis Baill.) is widely used by traditional communities in Northeast Brazil in the treatment of gastrointestinal diseases [76,77,78,79]. Given this ethnobotanical evidence, the need to conduct systematic experimental studies to evaluate the efficacy and possible mechanisms of action of these 17 species in models of diarrhea and gastric ulcer becomes evident. Scientific validation of these traditional uses is essential to support the development of new safe and effective herbal medicines derived from Croton species.

Table 3.

Croton species used in traditional medicine to treat gastrointestinal diseases without scientific investigation.

Table 3.

Croton species used in traditional medicine to treat gastrointestinal diseases without scientific investigation.

| Species | Part Used | Mode of Preparation and Administration | Medicinal Use | Country | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Croton argyrophylloides (=Croton tricolor Baill.) | Inner bark, root | Immersed in water, decoction, oral use | Stomach ache, upset stomach, diarrhea, indigestion | Brazil | Saraiva et al. [80] |

| Bark | - | Stomach ache | Brazil | Albuquerque et al. [76] | |

| Croton bonplandianus Baill. | Leaves | Juice | Protection of the stomach lining | Pakistan | Mahmood et al. [81] |

| Croton caudatus Geiseler | Leaves, roots | Maceration, oral use | Gastrointestinal problems | India | Kichu et al. [82] |

| Croton dichogamus Pax | Bark | Infusion, oral use | Stomach ache | Kenya | Mutie et al. [83] |

| Croton draconoides Müll.Arg. | Latex | 5 drops of latex diluted in 240 mL of water. Oral use | Internal ulcers, gastritis | Peru | Bussmann and Glenn [84] |

| Croton flavens L. | Leaves | Tea | Stomach problems | United States | Soelberg et al. [85] |

| Croton heliotropiifolius Kunth | Whole plant, leaves | Juice, decoction | Gastritis | Brazil | Castro et al. [77] |

| Croton laui Merr. & F.P.Metcalf | Leaves | Boiled, decoction, baths, oral injection | Stomach ache | China | Zheng et al. [86] |

| Croton limae A.P.S.Gomes, M.F.Sales & P.E.Berry | Bark | - | Belly ache | Brazil | Souza et al. [87] |

| Croton longiracemosus Hutch. | Seed, leaves | Decoction | Gastritis | Cameroon | Jiofack et al. [88] |

| Croton malambo H.Karst. | Leaves | Infusion, oral use | Colitis | Colombia | Duque et al. [89] |

| Croton megalocarpus Hutch. | Bark | Infusion, oral use | Constipation, stomach ache | Kenya | Mutie et al. [83] |

| Croton megalobotrys Müll.Arg. | Bark, root | Infusion, oral use | Swollen stomach (dropsy) | Zimbabwe | Maroyi [90] |

| Bark, root, leaves | - | Diarrhea | Kenya | Njoroge and Kibunga [91] | |

| Croton mubango Müll.Arg. | Stem bark, root bark | Maceration, oral use | Diarrhea, dysentery, abdominal pain | Congo | Otshudi et al. [73] |

| Leaves, stem | Decoction, drink 1 glass a day. | Diarrhea | Congo | Mbayo et al. [74] | |

| Hypogeous organ | - | Depurative for intestine, stomach ache | Angola | Urso et al. [75] | |

| Croton repens Schltdl. | Root | - | Diarrhea | Mexico | Leonti et al. [92] |

| Croton sonderianus (=Croton jacobinensis Baill.) | Inner stem bark | Tea, infusion | Digestive system disease, diarrhea | Brazil | Magalhães et al. [79] |

| Stem bark | Decoction, maceration | Diarrhea, indigestion, stomach | Brazil | Castro et al. [77] | |

| Stem | Tea, infusion | Diarrhea | Brazil | Lemos et al. [78] | |

| Bark | - | Diarrhea | Brazil | Albuquerque et al. [76] | |

| Croton texensis (Klotzsch) Müll.Arg. | Leaves | Tea | Stomach ache | Mexico | Camazine and Bye [93] |

4. Conclusions

Although the genus Croton comprises approximately 1200 species, only 11 have been evaluated for their antiulcerogenic and antidiarrheal potential to date. Among the bioactive compounds already identified, the diterpenes trans-dehydrocrotonin and trans-crotonin, isolated from C. cajucara, demonstrated significant antiulcerogenic activity in several experimental models in vivo. Similarly, crofelemer, a proanthocyanidin oligomer isolated from the bark latex of C. lechleri, has shown promising results in the treatment of patients with diarrhea in randomized clinical trials. Regarding the mechanisms of action, experimental evidence suggests that extracts and essential oils obtained from Croton species exert their gastroprotective effects, at least in part, through modulation of the nitric oxide pathway, promoting increased mucus production and reduced gastric acidity.

Regarding Croton species used empirically in traditional medicine, there remains a significant gap in knowledge about their pharmacological potential. Therefore, it is essential to carry out additional phytochemical, pharmacological, and toxicological studies to investigate the gastroprotective and antidiarrheal potential of the 17 species not yet evaluated, aiming to validate their ethnomedicinal uses and contribute to the development of new therapeutic agents of plant origin.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.J.L.B.; Methodology, J.J.L.B.; Data curation, J.J.L.B.; Formal analysis, J.J.L.B.; Investigation, J.J.L.B.; Validation, J.J.L.B.; Writing—original draft, J.J.L.B.; Writing—review and editing, A.F.M.d.O.; Supervision, A.F.M.d.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brazil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001. The first author is grateful to the Fundação de Amparo à Ciência e Tecnologia de Pernambuco (FACEPE—Brazil) (Process number: BFP-0417-2.10/24). The second author is grateful to the CNPq for the research grant (310177/2022-7).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, R.; Li, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhang, D. Global, regional, and national burden of 10 digestive diseases in 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1061453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Chase, R.C.; Li, T.; Ramai, D.; Li, S.; Huang, X.; Antwi, S.O.; Keaveny, A.P.; Pang, M. Global burden of digestive diseases: A systematic analysis of the global burden of diseases study, 1990 to 2019. Gastroenterology 2023, 165, 773–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslam, H.; Khan, A.U.; Qazi, N.G.; Ali, F.; Hassan, S.S.U.; Bungau, S. Pharmacological basis of bergapten in gastrointestinal diseases focusing on H+/K+ ATPase and voltage-gated calcium channel inhibition: A toxicological evaluation on vital organs. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1005154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Ren, K.; Zhou, Z.; Dang, C.; Zhang, H. The global, regional and national burden of peptic ulcer disease from 1990 to 2019: A population-based study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022, 22, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Song, Y.; Tao, J.; Jiang, M.; Liu, Y.; Cheong, I.H.; Kozlakidis, Z.; Chang, Z.; Wei, Q. Global trends, age-period-cohort analysis, and future projections of diarrhea burden: Findings from the global burden of disease study 2021. Biosaf. Health 2025, 7, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.Y.; Xu, F.; Zhao, W.; Wang, H.X.; Wang, H. The global burden of childhood diarrhea and its epidemiological characteristics from 1990 to 2021. Front. Pediatr. 2025, 13, 1656234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forgerini, M.; Mieli, S.; Mastroianni, P.D.C. Safety assessment of omeprazole use: A review. São Paulo Med. J. 2018, 136, 557–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzeloo-Moghadam, M.; Tavirani, M.R.; Jahani-Sherafat, S.; Tavirani, S.R.; Esmaeili, S.; Ansari, M.; Ahmadzadeh, A. Side effects of omeprazole: A system biology study. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench 2021, 14, 334. [Google Scholar]

- Akel, T.; Bekheit, S. Loperamide cardiotoxicity: “A brief review”. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2018, 23, e12505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magozwi, D.K.; Dinala, M.; Mokwana, N.; Siwe-Noundou, X.; Krause, R.W.; Sonopo, M.; McGaw, L.J.; Augustyn, W.A.; Tembu, V.J. Flavonoids from the genus Euphorbia: Isolation, structure, pharmacological activities and structure–activity relationships. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amtaghri, S.; Akdad, M.; Slaoui, M.; Eddouks, M. Traditional uses, pharmacological, and phytochemical studies of Euphorbia: A review. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2022, 22, 1553–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Sun, L.; Kong, C.; Mei, W.; Dai, H.; Xu, F.; Huang, S. Phytochemical and pharmacological review of diterpenoids from the genus Euphorbia Linn (2012–2021). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 298, 115574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Jiménez, S.; Valladares-Cisneros, M.G.; Salinas-Sánchez, D.O.; Pérez-Ramos, J.; Sánchez-Pérez, L.; Pérez-Gutiérrez, S.; Campos-Xolalpa, N. Anti-inflammatory and cytotoxic compounds isolated from plants of Euphorbia genus. Molecules 2024, 29, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengin, G.; Mahomoodally, M.F.; Sinan, K.I.; Ak, G.; Etienne, O.K.; Sharmeen, J.B.; Brunetti, L.; Leone, S.; Di Simone, S.C.; Recinella, L.; et al. Chemical composition and biological properties of two Jatropha species: Different parts and different extraction methods. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, I.; Rizwan, K.; Saber, F.R.; Munir, S.; Soria-Lopez, A.; Otero, P. Ethnotraditional uses and potential industrial and nutritional applications of secondary metabolites of genus Jatropha L. (Euphorbiaceae): A review. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 21, 101861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coy-Barrera, C.A.; Galvis, L.; Rueda, M.J.; Torres-Cortés, S.A. The Croton genera (Euphorbiaceae) and its richness in chemical constituents with potential range of applications. Phytomed. Plus 2025, 5, 100746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, J.J.L. Anticancer potential of essential oils from Croton L. species (Euphorbiaceae): A comprehensive review of ethnomedicinal, pharmacological, phytochemical, and toxicological evidence. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2024, 175, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, J.J.L.; Ferreira, A.P.; Luz, M.A.; Santos, T.P.; Torres, M.D.C.M. Ethnomedicinal uses, antiparasitic potential, and chemical composition of essential oils from Croton species (Euphorbiaceae): A comprehensive review. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2026, 188, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, I.B.; Bonfim, F.P.; Pasa, M.C.; Montero, D.A. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal flora in the rural community Rio dos Couros, state of Mato Grosso, Brazil. Bol. Latinoam. Caribe Plantas Med. Aromát. 2017, 16, 53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Bezerra, D.G.; Souza, R.R.; Couto, E.A.P.; Novaes, V.R.; Ribeiro, M.B.; de Souza, C.G.; Rodrigues, G.A.; Melo, C.C.; Agra, E.P.; Fernandes, I.C.; et al. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used by the population in the neighborhoods South of the city of Anápolis, Goiás State, Brazil. Rev. Bras. Plantas Med. 2018, 20, 10–27. [Google Scholar]

- Macedo, J.G.F.; de Menezes, I.R.A.; Ribeiro, D.A.; de Oliveira Santos, M.; de Mâcedo, D.G.; Macêdo, M.J.F.; de Almeida, B.V.; de Oliveira, L.G.S.; Leite, C.P.; Souza, M.M.D.A. Analysis of the variability of therapeutic indications of medicinal species in the Northeast of Brazil: Comparative study. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 2018, 6769193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandeira, A.S.; Sousa, V.F.O.; Santos, G.L.; Rodrigues, M.H.B.S.; Maracajá, P.B.; Silva, R.A.; Santos, J.J.F.; Ribeiro, M.D.S. Ethnoknowledge: Use of medicinal plants in communities. J. Exp. Agric. Int. 2018, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damtie, D. Review of medicinal plants traditionally used to treat diarrhea by the people in the Amhara Region of Ethiopia. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2023, 2023, 8173543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankiso, M.; Asfaw, Z.; Warkineh, B.; Abebe, A.; Sisay, B.; Debella, A. Ethnoveterinary medicinal plants and their utilization by the people of Soro district, Hadiya zone, southern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2024, 20, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, A.N.; Atnafie, S.A.; Atta, M.A.W. Evaluation of antiulcer activity of 80% methanol extract and solvent fractions of the root of Croton macrostachyus Hocsht: Ex Del. (Euphorbiaceae) in rodents. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2020, 2020, 2809270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantas, T.d.S.; da Silva, W.A.V.; Machado, J.C.B.; dos Santos, E.C.F.; de Lima, J.S.; Amaral, E.V.F.D.; Ribeiro, K.A.; da Silva, M.S.; da Cruz, R.C.D.; de Souza, I.A.; et al. Gastroprotective and antifungal evaluation of spray-dried extract and effervescent pre-formulation from Croton blanchetianus Baill leaves. J. Biol. Active Prod. Nat. 2023, 13, 522–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, A.I.O.; Terefe, E.M. Evaluation of the antidiarrheal activity of dichloromethane-methanol crude extract of the aerial parts of Croton kinondoensis (Euphorbiaceae) in Mice. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0333527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Júnior, F.E.B.; de Oliveira, D.R.; Bento, E.B.; Leite, L.H.I.; Souza, D.O.; Siebra, A.L.A.; Sampaio, R.S.; Martins, A.O.P.B.; Ramos, A.G.B.; Tintino, S.R.; et al. Antiulcerogenic Activity of the Hydroalcoholic Extract of Leaves of Croton campestris A. St.-Hill in Rodents. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 579346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Júnior, F.E.; de Oliveira, D.R.; Boligon, A.A.; Athayde, M.L.; Kamdem, J.P.; Macedo, G.E.; da Silva, G.F.; de Menezes, I.R.; Costa, J.G.; Coutinho, H.D.M.; et al. Protective effects of Croton campestris A. St-Hill in different ulcer models in rodents: Evidence for the involvement of nitric oxide and prostaglandins. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 153, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, C.S.; Martins, A.O.B.P.B.; Silva, A.A.; Oliveira, M.R.C.; Ribeiro-Filho, J.; Albuquerque, T.R.; Coutinho, H.D.M.; Almeida, J.R.G.S.; Quintans Junior, L.J.; Menezes, I.R.A. Gastroprotective effect and mechanism of action of Croton rhamnifolioides essential oil in mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 89, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, A.S.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Hiruma-Lima, C.A.; Haun, M.; Nunes, D.S. Antiulcerogenic activity of trans-dehydrocrotonin from Croton cajucara. Planta Med. 1998, 64, 126–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiruma-Lima, C.A.; Toma, W.; Gracioso, J.S.; Almeida, A.B.A.; Batista, L.M.; Magri, L.; Paula, A.C.B.; Soares, F.R.; Nunes, D.S.; Brito, A.R.M.S. Natural trans-Crotonin: The Antiulcerogenic Effect of Another Diterpene Isolated from the Bark of Croton cajucara Benth. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2002, 25, 452–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crutchley, R.D.; Miller, J.; Garey, K.W. Crofelemer, a novel agent for treatment of secretory diarrhea. Ann. Pharmacother. 2010, 44, 878–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottreau, J.; Tucker, A.; Crutchley, R.; Garey, K.W. Crofelemer for the treatment of secretory diarrhea. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 6, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chordia, P.; MacArthur, R.D. Crofelemer, a novel agent for treatment of non-infectious diarrhea in HIV-infected persons. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 7, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacArthur, R.D.; Hawkins, T.N.; Brown, S.J.; LaMarca, A.; Clay, P.G.; Barrett, A.C.; Bortey, E.; Paterson, C.; Golden, P.L.; Forbes, W.P. Efficacy and safety of crofelemer for noninfectious diarrhea in HIV-seropositive individuals (ADVENT trial): A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, two-stage study. HIV Clin. Trials 2013, 14, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohlmann, P.R.; Graham, D.; Wu, T.; Ottaviano, Y.; Mohebtash, M.; Kurian, S.; McNamara, D.; Lynce, F.; Warren, R.; Dilawari, A.; et al. HALT-D: A randomized open-label phase II study of crofelemer for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced diarrhea in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer receiving trastuzumab, pertuzumab, and a taxane. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2022, 196, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, J.J.L. Pharmacological Potential of Cyperaceae Species in Experimental Models of Gastrointestinal Disorders: A Review. Sci. Pharm. 2025, 93, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiruma-Lima, C.A.; Gracioso, J.S.; Nunes, D.S.; Brito, A.S. Effects of an essential oil from the bark of Croton cajucara Benth. on experimental gastric ulcer models in rats and mice. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1999, 51, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiruma-Lima, C.A.; Gracioso, J.S.; Rodrıguez, J.A.; Haun, M.; Nunes, D.S.; Brito, A.S. Gastroprotective effect of essential oil from Croton cajucara Benth. (Euphorbiaceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2000, 69, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiruma-Lima, C.A.; Gracioso, J.S.; Bighetti, E.J.; Grassi-Kassisse, D.M.; Nunes, D.S.; Brito, A.S. Effect of essential oil obtained from Croton cajucara Benth. on gastric ulcer healing and protective factors of the gastric mucosa. Phytomedicine 2002, 9, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paula, A.C.B.; Gracioso, J.S.; Toma, W.; Hiruma-Lima, C.A.; Carneiro, E.M.; Brito, A.R.S. The antiulcer effect of Croton cajucara Benth in normoproteic and malnourished rats. Phytomedicine 2008, 15, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho-de-Souza, A.N.; Lahlou, S.; Barreto, J.E.; Yum, M.E.; Oliveira, A.C.; Oliveira, H.D.; Celedônio, N.R.; Feitosa, R.G.; Duarte, G.P.; Santos, C.F.; et al. Essential oil of Croton zehntneri and its major constituent anethole display gastroprotective effect by increasing the surface mucous layer. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 27, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordeiro, K.W.; Pinto, L.A.; Formagio, A.S.N.; Andrade, S.F.; Kassuya, C.A.L.; Cássia Freitas, K. Antiulcerogenic effect of Croton urucurana Baillon bark. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 143, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degu, A.; Engidawork, E.; Shibeshi, W. Evaluation of the anti-diarrheal activity of the leaf extract of Croton macrostachyus Hocsht. ex Del. (Euphorbiaceae) in mice model. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 16, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.D.S.; Silva, K.D.M.; Neto, J.C.; Costa, V.C.O.; Pessôa, H.D.L.F.; Tavares, J.F.; Silva, M.S.; Cavalcante, F.A. Croton grewioides Baill. (Euphorbiaceae) shows antidiarrheal activity in mice. Pharmacogn. Res. 2016, 8, 202–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula, A.; Toma, W.; Gracioso, J.; Hiruma-Lima, C.A.; Carneiro, E.M.; Brito, A.S. The gastroprotective effect of the essential oil of Croton cajucara is different in normal rats than in malnourished rats. Br. J. Nutr. 2006, 96, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozza, A.L.; Moraes, T.M.; Kushima, H.; Nunes, D.S.; Hiruma-Lima, C.A.; Pellizzon, C.H. Involvement of glutathione, sulfhydryl compounds, nitric oxide, vasoactive intestinal peptide, and heat-shock protein-70 in the gastroprotective mechanism of Croton cajucara Benth. (Euphorbiaceae) essential oil. J. Med. Food 2011, 14, 1011–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, A.M.; Maria-Ferreira, D.; Souza, E.F.J.; Souza, L.M.; Sassaki, G.L.; Iacomini, M.; Werner, M.F.P.; Cipriani, T.R. Gastroprotective effect and chemical characterization of a polysaccharide fraction from leaves of Croton cajucara. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 95, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, G.O.; Penha, A.R.S.; Silva, G.Q.; Colares, A.V.; Rodrigues, F.F.G.; Costa, J.G.M.; Cardoso, A.L.H.; Campos, A.R. Gastroprotective effect of medicinal plants from Chapada do Araripe, Brazil. J. Young Pharm. 2009, 1, 54–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tradtrantip, L.; Namkung, W.; Verkman, A.S. Crofelemer, an antisecretory antidiarrheal proanthocyanidin oligomer extracted from Croton lechleri, targets two distinct intestinal chloride channels. Mol. Pharmacol. 2010, 77, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Trejo, B.; Sánchez-Mendoza, M.E.; Becerra-García, A.A.; Cedillo-Portugal, E.; Castillo-Henkel, C.; Arrieta, J. Bioassay-guided isolation of an anti-ulcer diterpenoid from Croton reflexifolius: Role of nitric oxide, prostaglandins and sulfhydryls. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2008, 60, 931–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurgel, L.A.; Silva, R.M.; Santos, F.A.; Martins, D.T.; Mattos, P.O.; Rao, V.S. Studies on the antidiarrhoeal effect of dragon’s blood from Croton urucurana. Phytother. Res. 2001, 15, 319–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akinlolu, A.A.; Kamaldeen, G.O.; Francis, D.; Ameen, M.O. Low anti-ulcerogenic potentials of essential oils and methanolic extract of Croton zambesicus leaves. J. Intercult. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 3, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okokon, J.E.; Umoh, U.F.; Udobang, J.A.; Etim, E.I. Antiulcerogenic activity of ethanolic leaf extract of Croton zambesicus in rats. Afr. J. Biomed. Res. 2010, 13, 119–123. [Google Scholar]

- Okokon, J.E.; Nwafor, P.A. Antiulcer and anticonvulsant activity of Croton zambesicus. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2009, 22, 384–390. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; Wang, D.; Li, Q.; Tong, Y.; Yang, Z.; Wang, T. Trans-anethole ameliorates LPS-induced inflammation via suppression of TLR4/NF-κB pathway in IEC-6 cells. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 108, 108872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahid, M.S.H.; Awasthi, S.P.; Hinenoya, A.; Yamasaki, S. Anethole inhibits growth of recently emerged multidrug resistant toxigenic Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor variant strains in vitro. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2015, 77, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, T.S.; Crutchley, R.D.; Tucker, A.M.; Cottreau, J.; Garey, K.W. Crofelemer for the treatment of chronic diarrhea in patients living with HIV/AIDS. HIV AIDS 2013, 5, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.A.; Hiruma-Lima, C.A.; Souza Brito, A.R. Antiulcer activity and subacute toxicity of trans-dehydrocrotonin from Croton cajucara. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2004, 23, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Casa, C.; Villegas, I.; De La Lastra, C.A.; Motilva, V.; Calero, M.M. Evidence for protective and antioxidant properties of rutin, a natural flavone, against ethanol induced gastric lesions. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2000, 71, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaleye, M.T.; Akinmoladun, A.C. Comparative gastroprotective effect of post-treatment with low doses of rutin and cimetidine in rats. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 27, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrau, U.; Saleh, M.I.A.; Alhassan, A.W.; Babale, A.I.; Saminu, S.; Dogara, K.J. Studies on antidiarrhoeal activities of rutin in mice. Niger. J. Sci. Res. 2019, 18, 389–395. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.; Zhou, B.; Liu, H.; Chen, S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, T.; Wang, C. Dietary rutin improves the antidiarrheal capacity of weaned piglets by improving intestinal barrier function, antioxidant capacity and cecal microbiota composition. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 6262–6275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvez, J.; Crespo, M.E.; Jimenez, J.; Suarez, A.; Zarzuelo, A. Antidiarrhoeic activity of quercitrin in mice and rats. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1993, 45, 157–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvez, J.; Medina, F.S.; Jimenez, J.; Torres, M.I.; Fernandez, M.I.; Nunez, M.C.; Ríos, A.; Gil, A.; Zarzuelo, A. Effect of quercitrin on lactose-induced chronic diarrhoea in rats. Planta Med. 1995, 61, 302–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimoyama, A.T.; Santin, J.R.; Machado, I.D.; Silva, A.M.O.; Melo, I.L.P.; Mancini-Filho, J.; Farsky, S.H. Antiulcerogenic activity of chlorogenic acid in different models of gastric ulcer. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2013, 386, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, M.A.; Mohanad, M.; Ahmed, A.A.; Aboulhoda, B.E.; El-Awdan, S.A. Mechanistic insights into the protective effects of chlorogenic acid against indomethacin-induced gastric ulcer in rats: Modulation of the cross talk between autophagy and apoptosis signaling. Life Sci. 2021, 275, 119370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonyong, C.; Angkhasirisap, W.; Kengkoom, K.; Jianmongkol, S. Different protective capability of chlorogenic acid and quercetin against indomethacin-induced gastrointestinal ulceration. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2023, 75, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.A.; Rao, V.S.N. 1,8-cineol, a food flavoring agent, prevents ethanol-induced gastric injury in rats. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2001, 46, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldas, G.F.R.; Oliveira, A.R.D.S.; Araújo, A.V.; Lafayette, S.S.L.; Albuquerque, G.S.; Silva-Neto, J.D.C.; Costa-Silva, J.H.; Ferreira, F.; Costa, J.G.M.; Wanderley, A.G. Gastroprotective mechanisms of the monoterpene 1,8-cineole (eucalyptol). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalilzadeh-Amin, G.; Maham, M. The application of 1,8-cineole, a terpenoid oxide present in medicinal plants, inhibits castor oil-induced diarrhea in rats. Pharm. Biol. 2015, 53, 594–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otshudi, A.L.; Vercruysse, A.; Foriers, A. Contribution to the ethnobotanical, phytochemical and pharmacological studies of traditionally used medicinal plants in the treatment of dysentery and diarrhoea in Lomela area, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2000, 71, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbayo, K.M.; Kalonda, M.E.; Tshisand, T.P.; Kisimba, K.E.; Mulamba, M.; Richard, M.K.; Sangwa, K.G.; Mbayo, K.G.; Maseho, M.F.; Bakari, S.; et al. Contribution to ethnobotanical knowledge of some Euphorbiaceae used in traditional medicine in Lubumbashi and its surroundings (DRC). J. Adv. Bot. Zool. 2016, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Urso, V.; Signorini, M.A.; Tonini, M.; Bruschi, P. Wild medicinal and food plants used by communities living in Mopane woodlands of southern Angola: Results of an ethnobotanical field investigation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 177, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, U.P.; Medeiros, P.M.; Almeida, A.L.S.; Monteiro, J.M.; Neto, E.M.D.F.L.; Melo, J.G.; Santos, J.P. Medicinal plants of the caatinga (semi-arid) vegetation of NE Brazil: A quantitative approach. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 114, 325–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, K.N.C.; Wolschick, D.; Leite, R.R.S.; Andrade, I.M.; Mayo, S.J. Ethnobotanical and ethnoveterinary study of medicinal plants used in the municipality of Bom Princípio do Piauí, Piauí, Brazil. J. Med. Plants Res. 2016, 10, 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, I.C.S.; Silva, L.G.; Delmondes, G.A.; Lima, C.N.F.; Fernandes, G.P.; Barbosa, R.; Menezes, I.R.A.; Kerntopf, M.R. Natural resource use in traditional community for the treatment of diarrheal diseases in children from the Northeast of Brazil. J. Med. Plants 2016, 4, 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Magalhães, K.D.N.; Guarniz, W.A.S.; Sá, K.M.; Freire, A.B.; Monteiro, M.P.; Nojosa, R.T.; Bieski, I.G.C.; Custódio, J.B.; Balogun, S.O.; Bandeira, M.A.M. Medicinal plants of the Caatinga, northeastern Brazil: Ethnopharmacopeia (1980–1990) of the late professor Francisco José de Abreu Matos. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 237, 314–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, M.E.; Ulisses, A.V.R.d.A.; Ribeiro, D.A.; de Oliveira, L.G.S.; de Macêdo, D.G.; Sousa, F.d.F.S.d.; de Menezes, I.R.A.; Sampaio, E.V.d.S.B.; Souza, M.M.d.A. Plant species as a therapeutic resource in areas of the savanna in the state of Pernambuco, Northeast Brazil. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 171, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, A.; Qureshi, R.A.; Mahmood, A.; Sangi, Y.; Shaheen, H.; Ahmad, I.; Nawaz, Z. Ethnobotanical survey of common medicinal plants used by people of district Mirpur, AJK, Pakistan. J. Med. Plants Res. 2011, 5, 4493–4498. [Google Scholar]

- Kichu, M.; Malewska, T.; Akter, K.; Imchen, I.; Harrington, D.; Kohen, J.; Vemulpad, S.R.; Jamie, J.F. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants of Chungtia village, Nagaland, India. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 166, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutie, F.M.; Gao, L.L.; Kathambi, V.; Rono, P.C.; Musili, P.M.; Ngugi, G.; Hu, G.W.; Wang, Q.F. An ethnobotanical survey of a dryland botanical garden and its environs in Kenya: The Mutomo hill plant sanctuary. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2020, 2020, 1543831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussmann, R.W.; Glenn, A. Plants used for the treatment of gastro-intestinal ailments in Northern Peruvian ethnomedicine. Arnaldoa 2010, 17, 255–270. [Google Scholar]

- Soelberg, J.; Davis, O.; Jäger, A.K. Historical versus contemporary medicinal plant uses in the US Virgin Islands. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 192, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.L.; Wei, J.H.; Sun, W.; Li, R.T.; Liu, S.B.; Dai, H.F. Ethnobotanical study on medicinal plants around Limu Mountains of Hainan Island, China. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 148, 964–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, R.K.D.; Silva, M.A.P.; Menezes, I.R.A.; Ribeiro, D.A.; Bezerra, L.R.; Souza, M.M.A. Ethnopharmacology of medicinal plants of carrasco, northeastern Brazil. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 157, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiofack, T.; Fokunang, C.; Guedje, N.; Kemeuze, V.; Fongnzossie, E.; Nkongmeneck, B.A.; Mapongmetsem, P.M.; Tsabang, N. Ethnobotanical uses of some plants of two ethnoecological regions of Cameroon. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2009, 3, 664–684. [Google Scholar]

- Duque, M.; Gómez, C.M.; Cabrera, J.A.; Guzmán, J.D. Important medicinal plants from traditional ecological knowledge: The case La Rosita community of Puerto Colombia (Atlántico, Colombia). Bol. Latinoam. Caribe Plantas Med. Aromát. 2018, 17, 324–341. [Google Scholar]

- Maroyi, A. Garden Plants in Zimbabwe: Their ethnomedicinal uses and reported toxicity. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2012, 10, 045–057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoroge, G.N.; Kibunga, J.W. Herbal medicine acceptance, sources and utilization for diarrhoea management in a cosmopolitan urban area (Thika, Kenya). Afr. J. Ecol. 2007, 45, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonti, M.; Vibrans, H.; Sticher, O.; Heinrich, M. Ethnopharmacology of the Popoluca, Mexico: An evaluation. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2001, 53, 1653–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camazine, S.; Bye, R.A. A study of the medical ethnobotany of the Zuni Indians of New Mexico. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1980, 2, 365–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.