Abstract

Electrospinning has emerged as a powerful technique for fabricating customised nanofibrous materials with integrated functional nanostructures, offering significant advantages for electrochemical energy applications. This review highlights recent advances in using electrospun nanofibres directly as active components in devices such as batteries, supercapacitors, and fuel cells. The emphasis is on the role of composite design, fibre morphology and surface chemistry in enhancing charge transport, catalytic activity and structural stability. Integrating carbon-based frameworks, conductive polymers, and inorganic nanostructures into electrospun matrices enables multifunctional behaviour and improves device performance. The resulting nanofibrous composite materials, often after heat treatment, can be used directly as electrodes or self-supporting layers, eliminating the need for additional processing steps such as size reduction or preparation of slurries and inks for creating functional nanofibre-based deposits. The importance of composite nanofibres as an emerging strategy for overcoming challenges related to scalability, long-term durability, and interface optimisation is also discussed. This review summarises the key results obtained to date and highlights the potential of electrospun nanofibres as scalable, high-performance materials for next-generation energy technologies, outlining future directions for their rational design and integration.

1. Introduction

Electrospinning is a powerful and versatile technique for producing nanostructured fibres with diameters ranging from tens of nanometres to a few micrometres. Although originally developed for textile and filtration applications, it has evolved into a key method in several material science fields [1,2].

At its core, ES relies on applying a high-voltage electric field to a polymer solution or melt. The setup typically comprises a syringe pump to control the flow rate of the polymer solution, a spinneret (usually a metallic needle), a high-voltage power supply, and a grounded collector. When the electric field overcomes the surface tension of the polymer droplet at the needle tip, a Taylor cone forms and a charged jet is ejected. This jet then undergoes stretching and whipping instabilities, resulting in the formation of ultrafine fibres that solidify and deposit on the collector.

The morphology and quality of the resulting fibres depend on various parameters. These include solution properties such as viscosity, conductivity, surface tension and polymer concentration; operational parameters such as the applied voltage, the flow rate and the distance between the needle and the collector; and environmental conditions such as temperature and humidity. Fine-tuning these variables enables control over fibre diameter, alignment, porosity and surface functionality, thus allowing materials to be designed for specific applications [3].

This outstanding technique offers several advantages over conventional fibre fabrication methods. From a processing perspective, it is relatively simple, cost-effective and scalable. It can be used with a wide range of polymers, including synthetic, natural and biodegradable varieties, as well as composite systems incorporating nanoparticles, metal precursors (MOFs and metal salts) and conductive polymers [4]. Electrospun products—typically nonwoven mats composed of randomly oriented or aligned fibres—exhibit a high surface area-to-volume ratio, interconnected porosity, and mechanical flexibility.

ES can be used to create different fibre architectures and material systems for various applications. Nanofibre mats, which are composed of randomly oriented fibres, are commonly used in filtration and energy storage applications. Aligned fibres, produced using rotating collectors or patterned electrodes, are used in electronics and tissue engineering. Coaxial electrospinning enables the production of core–shell fibres for use in drug delivery and multilayered energy devices. Composite fibres incorporating metal compounds, carbon nanotubes, or conductive polymers possess enhanced mechanical and electrochemical performance [5,6].

Considering the reported scenario, electrospun nanofibres offer several advantages for energy applications (e.g., supercapacitors, batteries and hydrogen-based systems), where efficient charge transport, ion diffusion and active surface interactions are essential [7,8,9]. Indeed, conventional electrode materials suffer from limitations related to sluggish ion transport, poor cyclability due to structural instability and inefficient use of active-materials. Conversely, nanofibres have emerged as a promising platform for advancing next-generation electrochemical energy devices, especially in terms of scalability, long-term durability and interface optimisation.

In terms of scalability, electrospinning can be extended from laboratory research to pilot and industrial production [10,11,12]. This is facilitated by the inherently continuous and modular nature of the process, which can be implemented using multi-nozzle or free-surface systems to enhance throughput. The technique boasts broad material compatibility: polymers, composites and solutions containing oxides, metals or ceramic precursors can all be successfully converted into nanofibres without any fundamental changes to the protocol being necessary. Another key factor is the low production costs, as the equipment is comparatively simple and operates efficiently at room temperatures or pressure. A significant advantage is the ability to produce self-standing electrodes, which eliminates or reduces the need for conductive binders and metallic current collectors, thus greatly simplifying the production process. In summary, electrospinning enables the large-scale manufacturing of high-porosity, large-surface-area electrodes while maintaining precise morphological control. In terms of long-term durability and stability, electrospun electrodes significantly enhance the operational stability of devices over time. Their interconnected fibrillar structures can distribute mechanical and electrochemical stresses uniformly throughout the material, thus preventing failure mechanisms such as fracture or delamination [13,14]. Controlled porosity is essential for efficient management of mass transport, thereby mitigating clogging and degradation caused by the accumulation of undesirable reaction products [15]. Furthermore, structural reinforcements can be integrated, such as ceramic nanofibres or carbon scaffolds, which can substantially enhance the thermal and chemical resistance of the components. Finally, the uniform distribution of active sites and the more homogeneous current distribution contribute to superior stability at the electrode–electrolyte interface [16]. The key advantage is that the fibrous microstructure provides superior mechanical strength and exceptional electrochemical stability, significantly extending the operational service life of the device.

Finally, it is worth noting that electrospun layers offer a distinctive approach to enhancing interfacial efficiency, a critical factor in high-performance applications such as fuel cells, supercapacitors and batteries [13,17,18]. The inherently high specific surface area of the nanofibres directly increases the density of catalytic or active sites, which is beneficial for several applications. Electrospinning enables highly controllable interfaces to be created, allowing precise modulation of fibre diameter, surface functionalisation and gradual composition, as well as core–shell structures. The natural hierarchical porosity (micro-, meso- and macropores) of these fibrous mats improves electrolyte access and reduces diffusion resistance. Furthermore, incorporating conductive fibres (e.g., carbonised fibres) improves contact between the active phase and the conductor, optimising electronic percolation within the electrode. Ultimately, the fibrous architecture creates more efficient interfaces, reducing both ohmic and charge-transfer resistances and thus boosting overall device performance.

Numerous polymers can be used for the ES process. Those that can be transformed into porous, conductive carbon supports represent a significant advancement in the design of high-performance energy materials [19,20,21]. Polymers such as PAN and PVP are particularly valuable due to their ability to undergo controlled thermal treatment resulting in carbon-based structures with tailored porosity, conductivity and mechanical integrity. One of the key advantages of these carbonisable polymers is their processability. They can be electrospun into nanofibrous mats with a high surface area and interconnected pore networks, facilitating mass transport and enhancing electrochemical interactions. Upon carbonisation, these mats retain their fibrous morphology while acquiring electrical conductivity and chemical stability. This makes them suitable for use as electrodes, catalyst supports or current collectors in electrochemical devices.

Moreover, the porosity of the resulting carbon structures can be adjusted by altering the polymer composition, spinning parameters, and thermal treatment conditions. This tunability enables the optimisation of ion diffusion pathways, active surface exposure, and mechanical flexibility—critical factors in achieving high energy and power densities. Additionally, doping these polymers with heteroatoms (e.g., nitrogen, sulphur, or phosphorus) before carbonisation can enhance their electrochemical performance further by introducing pseudocapacitive behaviour or improving catalytic activity [22,23,24]. Furthermore, electrospun fibres can be functionalised during or after fabrication, enabling the incorporation of electroactive species, dopants, or structural reinforcements [25,26,27].

As mentioned above, the unique properties of electrospun fibres make them ideal for a variety of energy applications. Their high surface area, tunable porosity and customisable composition enable them to improve the performance of devices such as supercapacitors, batteries and hydrogen systems. Electrospun nanofibres are widely used in supercapacitor electrodes due to their capacity to enable rapid charge/discharge cycles and high power density. Carbon nanofibres derived from the pyrolysis of electrospun PAN offer excellent electrical conductivity and surface area. Incorporating transition metal compounds into the fibre matrix can enhance pseudocapacitive behaviour and increase energy density [28]. Conductive polymers such as PANI and PPy can also be incorporated to provide redox-active sites and mechanical flexibility. Furthermore, the porous structure of electrospun mats enables efficient ion transport and their mechanical robustness supports the development of flexible and wearable energy devices [29,30].

ES plays a critical role in the development of advanced battery electrodes. For example, high-capacity anodes of lithium-ion batteries with improved cycle stability can be made using electrospun CNFs doped with silicon nanoparticles, tin-based nanoparticles (NPs) or NPs based on transition metal compounds. LIB cathodes made from electrospun CNFs integrated with Li-based NPs have been reported to have great potential in terms of improved ion transport and structural integrity compared to corresponding bulk materials [31,32]. Furthermore, electrospun pyrolysed carbon fibres integrated with various nanostructures are promising anode materials for sodium-ion batteries, which are emerging as an alternative to LIBs due to the abundance and low cost of sodium. In lithium-sulphur batteries, composite or decorated electrospun carbon nanofibres are used to confine sulphur and mitigate the polysulfide shuttle effect, thereby improving utilisation and extending the life cycle of the active material. Separators are another important element of electrochemical energy devices that could benefit from electrospinning technology. Their high porosity enables high electrolyte uptake, ensuring good ionic conductivity. Furthermore, their fibrous structure provides excellent mechanical and thermal stability. Electrospun materials are increasingly being used in hydrogen-related technologies, such as water electrolysis, fuel cells and hydrogen storage. Electrospun fibres embedded with electrocatalysts such as platinum, iridium, or transition metals (e.g., nickel or cobalt) can serve as highly efficient electrodes for HER, OER and ORR [33]. Their high surface area and porosity facilitate gas release and mass transport, thereby improving overall efficiency. Electrospun PEMs made from sulfonated polymers or composite systems have high ionic conductivity and mechanical durability. This makes them suitable for use in both alkaline and proton-exchange membrane electrolysers [34]. In fuel cells, electrospun CNFs act as a catalyst support, providing a conductive, porous matrix for catalyst dispersion. Furthermore, electrospun GDLs enhance reactant transport and water management, thereby improving cell performance and longevity [35]. In hydrogen technologies, carbonised polymer supports offer excellent conductivity and corrosion resistance, providing robust platforms for electrocatalysts in water electrolysis and fuel cells. Their lightweight nature and structural versatility also make them ideal for use in portable energy systems. Finally, electrospun fibres incorporating MOFs, CNTs, or activated carbon are being explored for hydrogen storage via physisorption. Their high surface area and tunable porous structure enable efficient hydrogen uptake and release under moderate conditions [25].

This review summarises the latest findings on using electrospinning to produce components for direct use in electrochemical energy devices. This means that the electrospun materials used as electrodes and free-standing layers have not undergone additional preparation steps, such as size reduction, slurry/ink preparation or melting, nor have they had other components added to them, such as binders or conductive carbon, that could interfere with electrochemical behaviour. Fibres or mats are typically prepared by electrospinning composite polymer solutions and/or heat treating them after deposition to create nanofibres containing active elements or compounds on or within their surfaces. Where conductive materials are required, such as for electrodes, polymer mats are subjected to heat treatments to carbonise them. For other applications, such as separators or solid electrolytes, they can be used as prepared. The tables included in this review highlight the electrospinning materials and the subsequent treatments, as well as the main electrochemical characteristics of the materials and of the devices in which the produced mats were used.

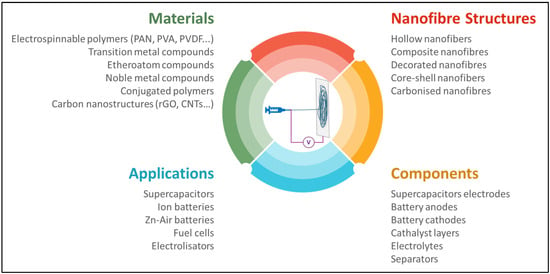

Figure 1 summarises the various aspects considered in this review. These include the materials that can be used to obtain nanofunctionalised electrospun nanofibres with different structures and morphologies, as well as the applications and device components that can be produced using the discussed technology.

Figure 1.

Characteristics and potentialities of the ES process.

2. Supercapacitor Electrodes

Supercapacitors can be considered green energy storage devices because they are typically made from inexpensive, sustainable and recyclable materials, and have a long cycle life and low maintenance costs. However, compared with batteries, SCs have lower electrical energy density and higher power density [36].

To be considered ‘super’, a capacitor must have a specific capacitance and a power density that is at least one hundred times greater than that of a conventional capacitor. These two characteristics essentially relate to the surface area of the electrodes exposed to the electrolyte and the electrical resistance of the entire electrode system, respectively. Therefore, the active material that constitutes the SC electrode must have a high specific surface area and low electrical resistance in order to minimise potential drops with the current collector [37]. There are two mechanisms of SC charge storage: electric double layer capacitance (EDLC), which is typical of carbon nanostructures and is based on the principle of the electrical double layer (EDL); and pseudocapacitive (PC) behaviour, which involves chemical processes including charge transfer through reduction-oxidation (redox) reactions [37]. Charge transfer rates in pseudocapacitive electrodes are higher than in batteries due to the thinner layers of redox material being used or lower ion penetration from the electrolyte into the structure. Furthermore, pseudocapacitors have higher capacitance values than electrochemical double-layer capacitors due to multiple processes acting to store charge.

SC electrodes are typically produced using straightforward coating methods such as slot-die coating, doctor blading, bar coating and dipping and drying. However, the uniformity and reproducibility of the coating thickness depend on the viscoelastic properties of the slurry, and solution wastage is often high. ES is a key technique for producing nanofibrous electrodes, particularly carbon-based ones made from pyrolysed PAN, PVA or PMMA mats. ES nanofibres can be functionalised with conducting polymers and nanostructured materials during electrospinning and/or subsequently using appropriate growth methods. Transition metal compounds can be introduced as metal salts or MOFs, or directly as metal-based NPs, during the electrospinning process. Similarly, different types of metal compounds can be grown on the nanofibres, such as MOFs, oxide NPs (which are sometimes followed by sulphurisation, selenisation and other treatments), layered double hydroxides, and so on. Moreover, when an electrospun nanofibrous mat containing carbonaceous or redox materials is used as an electrode, problems relating to thickness and compositional homogeneity are resolved.

A nanofibrous mat obtained by ES has specific properties that make this technique particularly advantageous for preparing an SC electrode. Firstly, the electrode material can be deposited directly onto the SC current collector, ensuring high adhesion and eliminating the need for binders. This simplifies the electrode structure and avoids the detrimental effect of binders on the electrical conductivity of massive electrodes. Secondly, its high intrinsic porosity facilitates the diffusion of electrolyte ions into the active material, thus favouring charge storage over a large surface area. Thirdly, it can be used to produce large-area, flexible devices at a relatively low cost and in a short processing time. Despite the significant benefits of using an electrospun mat for electrode production, achieving good cyclic stability remains a challenge.

In light of this, researchers are focusing increasingly on developing hybrid and/or composite electrodes that combine the advantages of different materials through synergistic effects. The aim is to introduce nanostructuring to improve the kinetics of ion and electron exchange.

Table 1 shows the most recent results relating to the development of self-supporting composite electrodes based on electrospun nanofibres functionalised with various types of nanostructures. The table reports data on the composition of the solution used in the electrospinning process, the post-electrospinning treatment conditions (in order of application), the specific capacitance measured on a single electrode, the device structure formed with the developed electrode, and finally, the measured energy density of the device (if applicable). It is worth noting that using the ES technique to obtain free-standing composite electrodes offers advantages in terms of processability, as layered structures can be created in fewer steps.

Table 1.

Materials that constitute the SC electrode and the electrospun suspension used; the sequence of post-electrospinning steps; and the characteristics of the single electrode and the device prepared using the electrospun mat as an electrode. SSC: Symmetric supercapacitor.

Transition metal oxides and sulphides are widely used in supercapacitor electrode technology. Manganese oxides are of particular interest due to their high specific capacitance, affordability, and environmental friendliness. Kim et al. [40] reported on the production of a CNF/(CNF/MnO2)/CNF sandwich structure via sequential electrospinning and carbonisation. In this structure, the MnO2 nanoparticles were not directly exposed to the electrolyte, and the CNF shells enhanced electrical conductivity due to their high surface area. The PMMA used in the interlayer electrospinning solution decomposed during thermal treatment, forming hollow channels along the fibre and promoting ion diffusion. Furthermore, PMMA was employed as a stabiliser in the formation of PMMA-Mn2+, resulting in smaller MnO2 NPs forming after heat treatment. These elements together confer good capacitance (220 @ 1 A/cm2) and excellent cyclability (94% retention rate after 10,000 cycles) to the prepared electrode.

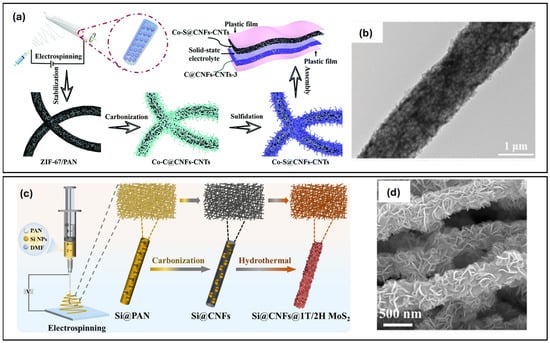

Yao et al. [54] demonstrated the applicability of a ‘tube-on-fibre’ hierarchical structure consisting of carbon nanotubes (CNTs), carbon nanofibres (CNFs) and cobalt sulphide (Co4S3), as an SC electrode. Figure 2a shows the preparation process, which involved the following steps: electrospinning PAN and Co(MOF), melamine-assisted calcination, and vulcanisation. The resulting nanofibres exhibited a porous structure, as can be seen in the TEM image shown in Figure 2b. This morphology ensured that the transition metal compounds were well exposed and able to catalyse the growth of CNTs. Subsequent vulcanisation led to the formation of Co-S bonds from Co-C bonds. This structure offered several advantages: the 3D ‘tube-on-fibre’ structure facilitated ion and electron transmission, and hierarchical nanostructuring provided numerous active sites to improve contact between the electrolyte and electrode materials. Moreover, good pseudocapacitance was achieved by incorporating Co4S3 into the fibres to prevent agglomeration and enhance mechanical and electrochemical stability. As a result, a specific capacitance of 416.5 F/g at 0.2 A/g was achieved with this “tube-on-fibre” structure.

Figure 2.

(a) Scheme of the fabrication of Co-S@CNF-CNT as a flexible electrode in supercapacitors. (b) TEM images of Co–S@CNF–CNT. (c) Scheme of the fabrication of Si@CNFs@1T/2H MoS2 film as an electrode for lithium-ion batteries. (d) SEM Image of Si@CNFs@1T/2H MoS2 film. (a,b) Reproduced with permission [54]. Copyright 2022, Royal Society of Chemistry. (c,d) Reproduced with permission [69]. Copyright 2022, Royal Society of Chemistry.

Another valid approach to improving SC electrode performance is to use metallic multi-phase materials in composite/hybrid electrodes. Acharya et al. [56] synthesised a dual-phase cobalt sulphide/cobalt oxyhydroxide using a hydrothermal growth process on Fe3C/PCNFs obtained via electrospinning and carbonisation. Adding PMMA to the electrospinning solution created pores and roughness in the mat after carbonisation, facilitating the growth of cobalt oxyhydroxide on its surface. Furthermore, they demonstrated that incorporating Fe3C, which was derived from the MIL-88A MOF, into the PCNFs enhanced the electrode’s capacitive behaviour and electrochemical activity. The resulting electrode was reported to have an outstanding specific capacitance of 1724 F/g at 1 A/g, and the corresponding device exhibited a maximum energy density of 65.68 Wh/kg at 752.7 W/kg.

Due to their high surface area, porosity and large number of active sites, MOFs show good potential as supercapacitor electrode materials through a battery-like charge storage mechanism. This storage mechanism can positively affect cyclic stability and rate capability, demonstrating that developing hybrid electrodes with carbon-based materials is a valid strategy. Jeong et al. [59] synthesised NiCo MOF nanorods on the surface of metal nanoparticle-enriched carbon nanofibres (NiCo CNFs). The metal nanoparticles were integrated with the CNFs to improve the efficiency of the hydrothermal growth of the NiCo MOF. The resulting morphology and chemical composition offered significant advantages in terms of enhanced charge transfer and storage kinetics. The specific capacitance of the resulting electrode was 2126.8 F/g at 1 A/g and the asymmetric SC exhibited a maximum energy density of 45.4 Wh/Kg at 800 W/Kg.

LDHs are another interesting class of material for use in supercapacitor applications. Their unique two-dimensional structure provides them with a high surface area and good redox properties. However, their use as a supercapacitor electrode is limited due to their low conductivity and the risk of agglomeration when used as a single material. To overcome these disadvantages, a supercapacitor electrode was prepared by loading NiCo-LDHs onto the surface of Co/CoO-CNFs [61]. Specifically, the Co/CoO-CNFs were obtained via electrospinning and carbonisation to improve the efficiency with which electrons are transported at the interfaces of the carbon matrix. The introduction of Co-based nanoparticles improved the degree of graphitisation of the CNFs and increased the porosity of the material. Subsequently, NiCo-LDHs were grown on the surface of these nanofibres via a hydrothermal process. Due to the difference in the Fermi levels of the Co/CoO-CNFs and the NiCo-LDHs, electrons are rapidly transferred from the LDH component to the fibres. This gives the material an excellent specific capacitance of 2055 F/g at 1 A/g.

Another approach to exploiting the potential of LDHs was recently reported by Liu et al. [62]. This approach involved creating a hierarchical multishell structure based on graphene-coated electrospun carbon nanofibres (GCNFs). The nanofibres acted as a substrate for the in situ synthesis of polyaniline (PANI), which was then subjected to hydrothermal growth of the NiCo-LDHs. The PANI intermediate layer facilitated the anchoring of the NiCo-LDH, resulting in a unique, flower-like morphology and a very high specific capacitance of 2499 F/g at 1 A/g.

The electrochemical characteristics of electrospun CNFs can also be improved by using graphene-based materials. Wang et al. [65] proposed a strategy involving electrostatic self-assembly and a “dipping and drying” strategy to anchor reduced graphene oxide (rGO) onto the surface of SnCl2-modified CNFs obtained via PAN electrospinning. SnCl2 was introduced to create an electrostatic attraction between the modified-PAN and the GO, enabling GO to assemble on the CNFs. SnCl2 also acted as a reducing agent for GO, converting the poor conductivity of the CNFs into a good conductivity in the PAN@rGO fibres. Finally, PPy was deposited on the PAN@rGO surface as a pseudocapacitive material, resulting in the PAN@rGO@PPy structure with its good electrochemical performance.

Another type of nanostructured material that can be used to engineer high-performance hybrid electrodes based on electrospun CNFs is carbon quantum dots. Zou et al. [68] produced a binder-free, freestanding electrode consisting of CNF, PANI, and CQD. The CNFs and PANI were produced via electrospinning, carbonisation and subsequent in situ polymerisation. Finally, a stable PANI/CQD heterostructure was formed by anchoring the CQDs onto the PANI surface through a chemical interaction between their functional groups. This unique three-dimensional network improves ion migration into the electrode, thereby enhancing its charging and discharging performance. The resulting electrode exhibited a specific capacitance of 756.5 F/g at 0.5 A/g and the corresponding symmetric SC achieved a maximum energy density of 6.86 Wh/Kg at 100 W/kg.

3. Battery Electrodes

3.1. Ion Batteries (Li, Na, K, Zn)

Alkali-ion batteries, which store energy using lightweight, highly mobile ions to store energy, have high energy density and good reversibility. Although lithium-ion technology is currently the most widespread and mature, the high cost and limited availability of some of the elements used in its production have led to increased interest in sodium and potassium ion batteries. However, it is necessary to develop increasingly efficient materials and electrodes for these batteries [70,71]. Unlike lithium-ion batteries, the use of a graphite-based anode is not advantageous in SIBs and PIBs, mainly due to the large dimensions of the intercalating ions (Na+ and K+), which hinder the effective intercalation in graphite layers and reduce the effective capacity [72]. Therefore, the performance of new generation anode materials with high capacity, such as those based on Si, Sn, Sb, Bi, Ge and transition metals, is being investigated [73,74,75,76,77]. These materials are promising candidates for the creation of high-performance anodes in alkali-ion batteries. However, their use is currently limited by several critical issues, including poor electrical conductivity and significant volumetric expansion during charge/discharge cycles [78,79]. The latter can generate substantial mechanical stress, favouring the formation of microfractures in the electrode and compromising the device’s cyclic stability.

To overcome these drawbacks, research is focusing on developing nanocomposites in which materials with a high specific capacity can be nanostructured and integrated into a porous carbon matrix [80,81,82]. This approach involves nanostructuring to reduce the transport distance of the ions, thereby promoting the kinetics. The presence of a porous carbon matrix allows for a greater electronic conductivity and enables adaptation to volume variations.

As illustrated in the previous paragraphs, ES appears to be a very promising technique for depositing porous nanofibrous structures, typically carbon-based, that can be appropriately functionalised and/or decorated with different types of nanostructures to exploit the synergy between the components of the nanocomposite material. Moreover, unlike traditional techniques, which necessitate the preparation of slurries containing additives and other substances that may affect the properties of the electrode, electrospinning enables the production of flexible and self-supporting electrodes. Table 2 shows some recent results relating to the development of self-supporting anodes for alkali-ion batteries. These anodes have a structure based on electrospun nanofibres that are enriched with additional nanostructures that confer the proper functionality. As in the previous table, this one reports data on materials, post-electrospinning treatments, and electrochemical performance.

Table 2.

Materials constituting the ion-battery anode and the used electrospun suspension; the sequence of post-electrospinning steps; the specific application; and the corresponding cyclability performance of the electrode.

Silicon is one of the most promising materials for use in lithium-ion battery anodes, but it suffers from volumetric expansion and low electronic conductivity. The Si@void@C yolk-shell structure is a promising anode candidate for lithium-ion batteries because the void space can accommodate volume expansion and minimise cracking [113,114,115]. Xie et al. [86] incorporated the Si@void@C structure directly into a CNF network via electrospinning, followed by carbonisation to produce a freestanding anode for LIBs. Si@void@C is obtained by removing the SiO2 template from a Si@SiO2@C structure, creating a void about 50 nm wide. In these nanoparticles, the carbon coating on NPs facilitated fast ion and electron transport, while simultaneously protecting the silicon core from corrosion caused by the electrolyte and preventing the formation of a solid electrolyte interphase (SEI). The CNFs network offered additional benefits to the final electrode: nitrogen doping provided more sites for storing lithium ions, the porous structure allowed electrolyte infiltration, and the voids in the porous structure could accommodate volumetric changes while preserving structural integrity. As a result, a good cyclability is achieved with a capacity of 627.5 mAh/g at 0.1 A/g after 100 cycles.

Two-dimensional transition metal sulphides are another class of materials with a high lithium storage capacity. Du et al. [69] prepared a Si@CNFs@1T/2H MoS2 film by electrospinning a mixture of PAN and Si NPs, followed by carbonisation and hydrothermal vertical growth of 1T/2H MoS2 nanosheets on the CNFs surface, as illustrated in Figure 2c. The MoS2 nanosheets anchored on the Si@CNFs surface are well visible in the SEM image shown in Figure 2d. This composite has numerous advantages. CNFs provide good mechanical properties and act as a propagation path for electron transport. They can also incorporate Si NPs effectively, thereby increasing conductivity and reducing volumetric expansion. The mixed 1T/2H MoS2 phase forms at an atomic level with a disordered, defect-rich structure that ensures excellent electrical conductivity and improved electrochemical energy storage capacity compared to single phases. The composite material is supplied as a self-supporting electrode, eliminating the need for further preparation processes. The final electrode retains a capacity of 976.1 mAh/g at 0.1 A/g after 100 cycles.

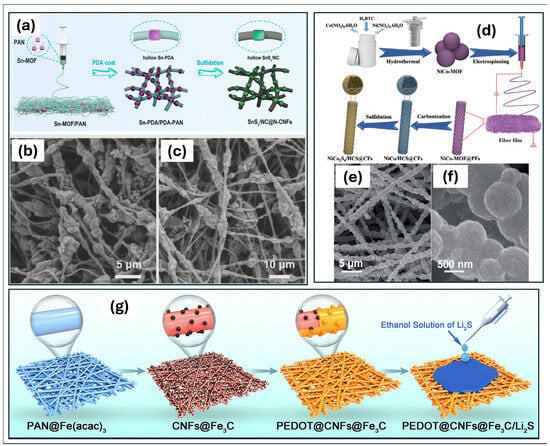

Regarding SIB anodes, although SnS has an impressive theoretical specific capacity, volume expansion and electrode cyclability remain problematic. Recently, an anode with ultralong cycling performance was prepared through electrospinning, PDA coating and calcination, as shown in Figure 3a [104]. This anode is a bean pod cube-shaped SnSx/NC@N-CNFs. First, cube-shaped Sn-MOFs were produced by electrospinning a PAN/Sn-MOF mixture, which distributed them uniformly across the nanofibres. This resulted in a Sn-MOF/PAN bead pod cube structure. Subsequently, the Sn-MOF acted as a self-sacrificing template to generate the hollow structure. During the PDA coating process, dissociation of the Sn-MOF and self-polymerisation of the dopamine occurred, forming a hollow Sn-PDA/PDA-PAN structure. The protrusions along the fibre, visible in Figure 3b, are due to the formation of hollow structures covered with PDA. The final SnSx/NC@N-CNFs, visible in Figure 3c, were obtained by sulphurisation. The hollow SnSx/NCs were well integrated into the nitrogen-doped carbon nanofibre network, maintaining the dimensions and morphology observed in the previous step (Figure 3d). This structure effectively encapsulated the SnSx nanoparticles within a hollow, nitrogen-doped carbon shell, thereby minimising volume expansion during cycling. Furthermore, the 3D nanofibrous network formed by electrospinning offered favourable mechanical properties for the electrode and facilitated the transfer of electrons and ions, thereby enhancing the reaction kinetics. This structure resulted in an outstanding cyclability with a capacity of 328 mAh/g at 2 A/g after 3500 cycles.

Figure 3.

(a) Scheme of the fabrication of Bean Pod Cube Hollow MOF-SnSx/NC@N-CNFs as an electrode for sodium-ion batteries. SEM images of (b) Sn-PDA/PDA-PAN and (c) MOF- SnSx/NC@N-CNFs. (d) Scheme of the fabrication of self-standing NiCo2S4/HCS@CF film as an electrode for zinc-ion batteries. (e,f) SEM images of NiCo2S4/HCS@CF at different magnifications. (g) Preparation route of the PEDOT@CNFs@Fe3C/Li2S composite cathode for Li–S batteries. (a–c) Reproduced with permission [104]. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society. (d–f) Reproduced with permission [116]. Copyright 2022, Royal Society of Chemistry. (g) Reproduced with permission [117]. Copyright 2025, Royal Society of Chemistry.

Yan et al. [111] reported a similar approach to developing a freestanding PIB anode based on nickel selenide (NiSe)/tin selenide (SnSe) NCs. A mixture of hollow NiSn(OH)6@PDA cubes, selenium powder, PAN and PVP was electrospun, and the resulting mat was thermally treated to undergo selenisation/carbonisation. The aim was to produce an H-NiSe/SnSe@NC film. Using selenium powder in the electrospinning solution ensured the rapid selenium diffusion during thermal treatment, resulting in the uniform selenide distribution throughout the composite material. The resulting freestanding electrode featured a nanofibrous conductive network that provided good conductivity. The hollow selenide NCs could accommodate volume changes during device operation, ensuring good cyclability, with a capacity of 226.3 mAh/g at 2 A/g after 1000 cycles.

Molybdenum-based materials are widely used in alkali-ion storage. Molybdenum phosphide (MoP) exhibits high capacity, good conductivity, fast reaction kinetics and stability, making it an ideal anode material for SIB/PIB. To address the issue of volumetric expansion in MoP-based anodes, Liu et al. [105] developed a porous, ribbon-like, Cu-modified MoP/SnO2 carbon fibre composite (MCPS). This composite material was produced by electrospinning a solution containing PMo12, pyrrole, phytic acid, SnCl2, CuSO4 and PVP, followed by carbonisation of the resulting mat. PMo12 and phytic acid were used as the MoP precursor. PMo12 also triggered the polymerisation of pyrrole, which acted as a dispersing agent. An amorphous tin oxide buffer phase was obtained by adding a tin salt to the solution, which improved the composite’s flexibility. Finally, the addition of copper sulphate induced the formation of pores along the fibres, thereby improving the composite electrochemical properties. The final electrode exhibited good cyclability, with a capacity of about 120 mAh/g at 1 A/g after 1000 cycles.

Several materials have been developed for the cathode of alkali-ion batteries according to the type of ion used. These include layered oxides (e.g., LiCoO2, LiNiO2, NaxCoO2, KxCoO2), spinel-structured oxides (e.g., LiMn2O4, LiNi0.5Mn1.5O4, NaMn2O4, KMn2O4), prussian blue analogues, and polyanions [118,119,120,121]. Although electrospinning and the preparation of freestanding nanofibrous composite electrodes could be relevant to cathode development, the available literature on this topic is much more limited than that relating to the anode. These approaches are also often simpler and less innovative. Some recent results are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3.

Materials constituting the ion-battery cathode and the electrospun suspension used; the sequence of post-electrospinning steps; the specific application; and the corresponding cyclability performance of the electrode.

Although LiFePO4 is one of the most widely used cathode materials at an industrial level in LIBs, its low conductivity and low lithium-ion diffusion coefficient present significant limitations. One potential solution to these issues is the application of conductive coatings and nanostructuring. Liu et al. [31] developed a flexible cathode by using electrospinning and pyrolysis to create LiFePO4@rGO/CNFs. This approach ensured the nanofibres had uniform dimensions, the LiFePO4 NPs were homogeneously distributed in the CNFs, and a good connection was established between the rGO sheets and the CNFs. The combination of rGO and CNFs creates a 3D conductive network that facilitates ion transport. Furthermore, rGO is a highly conductive material that provides an effective path for electron conduction. Similarly, Ren et al. [125] reported on the development of a self-supporting cathode for SIBs. This was achieved by combining Na4Fe3(PO4)2(P2O7) and CNFs via electrospinning and pyrolysis.

Multivalent ion batteries are an alternative to alkali-ion batteries. These batteries have several advantages, including a higher theoretical charge density and an abundance of constituent metals, such as zinc, magnesium, calcium and aluminium [136]. Some also operate with aqueous electrolytes, offering safety advantages [137]. While the anodes of multivalent ion batteries are metallic, the cathodes present a greater challenge, as the larger ionic radius and higher charge of multivalent ions hinder intercalation [138]. Highly conductive electrodes with wide channels are therefore required. Zinc-based batteries are currently among the most widely studied of the various types of multivalent batteries. Table 3 illustrates the development of self-supporting cathodes for aqueous zinc-ion batteries (ZIBs) obtained using electrospinning technology and nanostructured functional components.

Vanadium-based oxides are a very promising electrode material for ZIBs thanks to their high energy density and complex crystal structure. However, they have a low ion/electron transfer rate and experience capacity fading with repeated use. To address these issues, Wang et al. [131] incorporated V2O3 nanoparticles into N-doped bead-chain-like hollow carbon nanofibres using a combination of electrospinning and carbonisation processes. The ES solution contained NH4VO3 as the vanadium oxide source, PTFE as the organic pore-forming agent, and PVP as the nitrogen-containing carbon source and oxalic acid. During thermal treatment, the oxalic acid and NH4VO3 decomposed to produce reducing gases and vanadium oxide. During this process, meso- and micropores also formed in the carbon layer. The PTFE also degraded, acting as a template for the formation of meso- and macropores. The final structure exhibited a large number of pores, a high specific surface area, a three-dimensional carbon network, and a uniform distribution of V2O3 NPs. This ensured good ion and electron transport as well as mitigating volume expansion during battery operation with a capacity of 158.1 mAh/g at 20 A/g after 4000 cycles.

Ni/Co-based compounds are also a promising material for developing cathodes for ZIBs, thanks to their high theoretical capacity, operating voltage and energy density. Yu et al. [116] prepared a NiCo2S4/HCS@CFs cathode by electrospinning a PAN and NiCo-MOFsolution, subsequently undergoing carbonisation and sulfidation. Figure 3d illustrates the preparation procedure for such a cathode, while Figure 3e,f show the obtained morphology. Heat treatment following electrospinning resulted in the formation of bimetallic NiCo NPs embedded in a hollow carbon sphere (NiCo/HCS@CFs), formed when the MOF decomposed. The self-supporting NiCo2S4/HCS@CFs cathode was obtained by sulfurisation. The hollow, porous structure facilitated ionic diffusion, leading to the formation of a greater number of active sites. The NiCo2S4 nanoparticles were well dispersed in the carbon matrix, thereby increasing conductivity. The overall interconnected structure gave the electrode good structural stability and good cyclability (with a capacity of about 140 mAh/g at 5 A/g after 1000 cycles).

3.2. Metal–Sulphur Batteries

In the field of energy storage devices, metal–sulphur batteries are a promising alternative thanks to their low cost, high theoretical specific capacity, and high energy density [139]. However, their widespread use and commercialisation are currently prevented by several technical issues, including volume expansion during discharge, the formation of soluble polysulfide intermediates in the electrolyte and sluggish electrochemical reaction kinetics [139]. These factors can lead to the collapse of the sulphur cathode, induce the so-called ‘shuttle effect’, and generally result in poor device performance. Cathode design has been shown to be the most straightforward and effective way to improve sulphur electrochemistry [140]. In particular, developing ‘sulphur hosts’ to reduce dissolution while promoting the electrochemical conversion of polysulfides is a valid strategy [141]. Materials that can be used for this purpose include carbon-based porous structures, which have good electrical conductivity and can accommodate volume changes during operation. However, the non-polar nature of carbon-based materials means they have low chemical affinity with polysulphides and cannot solve all the identified problems alone [142]. Therefore, as in other cases, a valid approach is to functionalise the porous carbon structures with other types of materials, such as metals, metal oxides, sulphides, and nitrides. Thanks to their polar nature, these materials can act as more effective hosts and act as electro-catalysts, improving the kinetics of the conversion process. Electrospinning is once again a highly versatile technology for producing carbon nanofibres that can be further functionalised and/or decorated with various nanostructures to create the composite materials for use in metal–sulphur batteries.

Table 4 reports some of the most recent and interesting findings concerning the development of composite materials based on electrospun nanofibres for use as a self-standing cathode in metal–sulphur batteries.

Table 4.

Materials constituting the metal-S-battery cathode and the electrospun suspension used; the sequence of post-electrospinning steps; the specific application; and the corresponding cyclability performance of the electrode.

Pei et al. [144] reported on a ‘sulphur host’ consisting of self-supporting, electrospun CNFs containing Ni single atoms and Ni nanoparticles, with carbon dots acting as an aggregation-limiting agent. The use of CDs ensured the homogeneous dispersion of Ni NPs and regulated their size. This prevented the loss of active sites during high-temperature thermal treatment. Ni-SA and Ni-NPs exhibited excellent catalytic activity in sulphur reactions, while the CNFs had high conductivity and an “easy-to-infiltrate” structure, ensuring good wettability of the cathode towards the electrolyte. This kind of architecture ensures a good cyclability with a capacity of 823.5 mAh/g at 1C after 500 cycles.

Adsorption properties towards polysulfides can also be improved by incorporating polar functional groups and heteroatoms. Zhang et al. [146] designed free-standing nitrogen-doped electrospun CNFs functionalised with polar amide groups and combined them with spinel CoFe2O4 catalytic nanoparticles. The CNFs electrical conductivity facilitated the transfer of electrons and ions, while N-doping and the amide groups imparted polarity to the CNFs, thereby enhancing their polysulfide adsorption capability. Finally, the CoFe2O4 nanoparticles acted as catalytic sites, ensuring the rapid conversion of polysulfides and limiting the shuttle effect. The synergy between these components endowed the resulting cathode with excellent electrochemical properties (capacity retention of 690 mAh/g at 0.1 C after 450 cycles).

Shan et al. [149] recently produced a self-supporting Li-S cathode consisting of N-doped CNFs containing twin-born nickel sulphide nanoparticles (NiS2/Ni3S4@NCNFs). As is well documented, the three-dimensional CNF network is ideal for accommodating sulphur, and the incorporation of polar materials can improve both the adsorption and catalytic capabilities of polysulphides simultaneously. In this case, valence-mixed nickel sulphides exhibited exceptional absorption and catalytic properties for converting soluble polysulphides into insoluble ones. The resulting electrode exhibits excellent electrochemical properties, as evidenced by a capacity retention of 913.3 mAh/g at 0.2 C after 100 cycles.

Another interesting composite that can be used as a cathode in Li-S batteries was developed by Yang et al. [117]. They polymerised PEDOT onto the surface of CNFs@Fe3C, which was obtained via electrospinning and subsequent carbonisation and the preparation scheme is shown in Figure 3g. The dendritic structure of the PEDOT accelerated electron transfer and improved electrode wettability, while its sulphur functional groups exhibited a high affinity for polysulphides. Furthermore, PEDOT improved the electrical conductivity of the composite by connecting the dispersed Fe3C NPs along the fibre surface. Fe3C has high electrical conductivity and high catalytic activity towards polysulphides and combining it with carbon materials prevents aggregation. Thanks to its chemical and morphological characteristics, this cathode exhibited a high initial specific capacity and excellent cyclability (a capacity of 366 mAh/g at 0.5 C after 1000 cycles).

Other strategies for overcoming the challenges associated with metal–sulphur batteries include developing separator coatings and modifying the separators themselves, as well as using interlayers. The development of interlayers is a more practical approach than engineering-specific cathode materials. Recently, self-supporting interlayers have been produced using the electrospinning technique [150,151,152]. For example, Si et al. [151] produced a CNF@Ni3Se4/FeSe2 interlayer with high electrical conductivity, efficient chemisorption capabilities, numerous active sites and excellent catalytic properties. This was achieved by directly growing the Ni3Se4/FeSe2 on the electrospun CNFs. The aim is to use the Ni3Se4/FeSe2 heterostructure to catalyse the sulphur reduction simultaneously. Specifically, the authors theoretically demonstrated that FeSe2 and Ni3S4 catalyse the reduction of long- and short-chain polysulfides, respectively. This suppresses the shuttle effect and improves sulphur utilisation. Meanwhile, the interlayer on the anode side facilitates Li+ flux, thereby improving the deposition process and preventing dendrite formation.

Guan et al. [152] developed a robust interlayer consisting of N/P-codoped CNFs with semi-embedded Ni2P nanoparticles. Ni2P exhibits high electrical conductivity, strong polysulfide affinity and cost-effectiveness, making it a promising candidate for interlayer preparation in metal–sulphur batteries. The electrospinning and subsequent carbonisation processes used in the preparation technique ensured that the Ni2P nanoparticles were only partially embedded in the nanofibres. This exposed the catalytic sites while maintaining a robust and stable interface with the carbon matrix, thus preventing detachment. This interlayer exhibits fascinating properties at low temperatures, opening up new possibilities in the design of metal–sulphur batteries for use in extreme climatic conditions.

4. Electrocatalysts

Electrocatalysis plays an important role in facilitating charge transfer reactions at the electrode–electrolyte interface in electrochemical devices. It is fundamental in water splitting by electrolysis, fuel cell technology, and metal–air batteries, where the kinetics of electron transfer are intrinsically sluggish. The activity, selectivity and stability of electrocatalysts critically influence device efficiency, making their optimisation essential for advancing energy conversion and storage technologies. Electrocatalysts serve to lower activation energy barriers, thereby improving reaction rates and reducing energy losses [153,154]. In hydrogen production, electrocatalysts enable efficient HER and OER, which are critical for electrolyser performance. Similarly, in fuel cells, electrocatalysts facilitate the ORR, which directly impacts power output and system durability [155]. In Zn–air batteries, electrocatalysts also play a crucial role in enhancing the kinetics of ORR and OER, directly impacting the battery efficiency, reversibility, and overall performance [156]. Pt-, Ir-, and Ru-based catalysts are currently considered benchmarks for the aforementioned reactions. However, their high cost, limited availability, and poor long-term stability restrict their large-scale deployment. To address these issues, researchers are exploring strategies to reduce noble metal usage. The most widely investigated method is to reduce the size of the catalyst particles, resulting in a higher specific surface area and/or a specific crystallographic growth plane [157]. Another strategy is to combine noble metals with less expensive elements that exhibit moderate catalytic activity, such as Co, Ni, Fe, and others. Many researchers have investigated the use of compounds based on transition metals, such as oxides, phosphides and sulphides, as they offer excellent redox reversibility, making them attractive for HER, OER, and ORR. Their tunable bandgaps and the variety of available compositions allow for optimisation of electronic structure [158].

Whatever the approach or strategy used to avoid or decrease the use of noble metals as electrocatalysts, the main problem to solve is to maximise the catalytic efficiency and the accessibility of active sites as well as to minimise their coalescence during operational function, specifically when the electrocatalyst is used in the form of nanoparticles. A common method to solve this problem is to use conductive support (e.g., carbon) on which to disperse the catalyst nanomaterial. In hydrogen-related technologies, carbonised polymer supports offer excellent conductivity and corrosion resistance, providing robust platforms for electrocatalysts in water electrolysis or fuel cells [159]. Their lightweight nature and structural versatility also make them attractive for portable and wearable energy systems. The transformation of electrospun polymer nanofibres into porous conductive carbons bridges the gap between molecular design and functional performance, enabling the development of next-generation energy materials with superior performance.

In the context of hydrogen production and, more broadly, for porous electrodes in electrochemical devices, electrospun substrates offer distinct advantages that improve electrocatalytic performance for a variety of reasons. Firstly, electrospun CNFs derived from polymeric precursors, such as PAN, exhibit excellent electrical conductivity, mechanical strength, and chemical stability. These properties are crucial for supporting active electrocatalytic species and facilitating efficient electron transport. Secondly, the fibrous architecture generated via electrospinning provides a three-dimensional (3D) interconnected network that promotes the rapid mass transport of both reactants and products. This structural feature minimises diffusion limitations and enhances the accessibility of catalytic active sites, particularly under the high current density conditions typical of industrial-scale water electrolysis and fuel cell technology. Moreover, ES enables precise control over fibre diameter, surface roughness, and composition. This allows for the incorporation of heteroatoms (e.g., N, S, P) or transition metals (e.g., Fe, Co, Ni) into the carbon matrix, thereby tuning the electronic structure and enhancing catalytic activity. The technique also facilitates the uniform dispersion of metal NPs or MOF-derived catalysts, preventing agglomeration and ensuring long-term stability. Finally, electrospun supports can be engineered to possess hierarchical porosity, combining micro-, meso-, and macropores. This multi-scale porosity enhances electrolyte penetration and gas diffusion, both of which are essential for efficient hydrogen generation and utilization. These features mean that electrospinning has huge potential for effective use in electrocatalysis [20,160].

The structural morphology of CNFs can also contribute to improving the performance of electrocatalysts. Shin et al. [161] produced CNFs based on PAN with a core–shell structure in which the shell layer contained Co NPs. This method involved coaxial electrospinning, using a PAN solution as the core and a PAN solution containing a cobalt precursor as the shell layer. Following electrospinning and heat treatment, Co-CNFs were obtained, with Co NPs located on the surface, consequently increasing the number of catalytically active sites. By this structure, a small amount of catalyst resulted in a high bifunctional catalytic activity in ORR/OER. In fact, the Co-CNFs exhibited excellent ORR performance, with a diffusion current of approximately 6 mA/cm2 and a pathway of approximately 4e–. Additionally, the core–shell Co-CNFs exhibited a low overpotential of 322 mV at a current density of 10 mA/cm2 for the OER, demonstrating improved performance compared to Co-CNFs alone [161]. The increased electrocatalytic activity of the core–shell Co-CNFs was also attributed to the contribution of the highly conductive 1D CNFs supporting the superficial Co-NPs.

The coaxial electrospinning approach was also used for in situ synthesis and subsequent carbonisation to construct a highly integrated three-function catalyst composed of graphitic carbon-encapsulated cobalt nanoparticles embedded into one-dimensional (1D) porous hollow carbon nanofibres (CoNC-HCNFs) [162]. PAN/MeIM/PMMA nanofibres (denoted PMMNFs) were obtained by coaxial electrospinning and immersed in Zn and Co nitrate solution containing 2-methylimidazole. PMMNFs@Zn/Co-ZIF nanofibres were then obtained by growing Zn/Co-ZIF on PMMFs. After calcination in a nitrogen atmosphere, porous and hollow carbon nanofibres (denoted as HCNFs) were produced. The Co nanoparticles decorating the HCNFs were encapsulated in a multilayered graphite. Due to their hollow and porous structure and good electronic conductivity, the graphitised carbon-coated Co nanoparticles decorating the HCNFs demonstrated a low operating overpotential for HER (186 mV @ 10 mA/cm2), a potential of 1.58 V vs. RHE @10 mA/cm2 for OER and a positive half-wave potential for ORR (half-wave potential of 0.83 V vs. RHE).

Transition metal oxides are recognised as appealing bifunctional electrocatalysts due to their low cost, corrosion resistance, and high catalytic activity in alkaline solutions [163,164]. Among these transition metal oxides, Co and Fe-based oxides have demonstrated excellent intrinsic reactivity in contrast to precious metal-based catalysts. However, their poor conductivity has limited their further applications [165]. Hybrid nanostructures based on transition metal oxides can overcome these obstacles. Moreover, carbonaceous substrates decorated with metal oxides effectively improve dispersion and conductivity by optimising the electronic configuration [166,167,168]. A binder-free electrode based on a highly efficient electrocatalyst developed on a 3D skeleton as a current collector can solve the problems relating to ohmic drop and the functionality loss of active sites during use. Sun et al. [169] synthesised a flexible self-supporting Zn–air electrode (Co3O4/Fe2O3NAs@CNFs), composed of a carbon nanofibre network covered by Co3O4/Fe2O3 nanoparticles distributed on hierarchical flake nanoarrays. This structure originated from the carbonisation and subsequent oxidation of an Fe-doped Co/Zn-ZIF structure, grown on electrospun PAN nanofibres. The resulting N-doped carbon nanofibre network forms a conductive, stable, and interconnected 3D structure. Furthermore, the hierarchical flake array arrangement of Co3O4/Fe2O3NAs@CNFs anchors the Co3O4 and Fe2O3 nanoparticles on the porous N-doped carbon, enhancing conductivity and stability. Thanks to these characteristics, the so-prepared electrode demonstrated superior electrocatalytic activity for OER with an onset potential of 1.6 V and for ORR (onset at 1.01 V), as well as high performance in rechargeable aqueous Zn–air batteries and flexible solid-state batteries.

The activity of nanocatalysts results was enhanced when the nanoparticles embedded in or decorating the 3D nanostructure of CNFs are also constituted by transition metal phosphides or sulphides [170,171,172,173,174]. The good performance of these systems can be attributed to the three factors: (1) the synergistic effect between the metal transition phosphide or sulphide nanoparticles in the CNFs; (2) the presence of conductive CNFs (especially if N-doped) that not only minimises the resistance but also effectively avoids the corrosion from the electrolyte; and (3) the crosslinked carbon nanofibres that construct a conductive network, promoting the rapid transmission of electrons and limiting the agglomeration of NPs during catalytic reactions [175].

Heterostructure engineering has proven to be a key strategy for improving activity. Carbon materials, including graphene, CNTs, CNFs, and mesoporous carbon, are widely recognised for their high electrical conductivity, chemical stability, and tunable morphology. Actually, pristine carbon structures exhibit limited catalytic activity due to their inert electronic configuration and uniform charge distribution [176]. To overcome this limitation, heteroatom doping has been widely used to modify the electronic structure, introduce defects, and create active sites that are conducive to catalytic reactions. For this reason, heteroatom-doped carbon structures have emerged as a promising class of electrocatalysts, offering an attractive alternative to noble metal-based catalysts. Heteroatoms such as N, S, P, B, and F have different electronegativities and atomic radii compared to carbon. When incorporated into the carbon lattice, these atoms induce charge redistribution and variations in spin density, thereby enhancing the adsorption and activation of reactant molecules. For example, nitrogen doping introduces pyridinic-N, graphitic-N, and pyrrolic-N configurations, which are known to facilitate ORR kinetics by improving electron transfer and oxygen binding. Sulphur doping, often used in conjunction with nitrogen, contributes to the formation of thiophenic and sulfonic groups. These groups further modulate the local electronic environment and enhance catalytic activity [177].

Co-doping strategies involving combinations such as N-S or N-P have demonstrated synergistic effects, leading to enhanced onset potentials, increased current densities, and improved long-term stability under operating conditions. Moreover, heteroatom-doped carbon structures exhibit excellent tolerance to fuel crossover and CO poisoning, which are common issues in Pt-based systems. The robust chemical stability of these structures in acidic and alkaline conditions makes them suitable for a variety of electrochemical applications. Additionally, the use of earth-abundant precursors and a scalable synthesis method enhances their commercial viability.

When combined with nitrogen-doped carbon, bimetallic catalysts showed better electron transfer and synergistic effects than monometallic ones. These catalysts exhibit superior redox reaction rates and electrical conductivity, resulting in improved electrochemical performance. Recent advances have demonstrated the catalytic operability of systems in which the bimetallic active sites are encapsulated in N-doped carbon structures. Multi-layer carbon-encapsulated RuMn alloy nanoparticles loaded onto carbon nanofibres (RuMn/CNFs) were produced using an electrospinning carbonisation protocol to integrate the lower electronegativity of Mn with the higher electronegativity of Ru [178]. The intercalation behaviour of metal atoms within and outside the carbon-encapsulated core–shell structure for RuMn/CNFs was monitored by measuring the metal ion concentrations in the electrolyte. It was found that, due to the different electronegativity of the internal metals, Mn atoms migrated through the carbon layer into the electrolyte during continuous water electrolysis. This produced the formation of alloy defects that promoted the Volmer step of water adsorption and dissociation on the carbon shell, resulting in the spontaneous activation behaviour of the core–shell catalyst RuMn alloy structure. The RuMn/CNFs composite exhibited exceptional performance, demonstrating an ultralow overpotential of 80 mV@100 mA/cm2 and a Tafel slope of 46.3 mV/dec. This outperforms most reported Ru-anchoring-based catalysts. Moreover, it showed superior electrocatalytic stability at high current densities in anion exchange membrane water electrolysis systems (AEMWEs).

Due to its electronic structure being similar to that of the Pt-group metals [179,180,181], molybdenum and its compounds, including alloys, sulphides, selenides, carbides, phosphides, nitride, and oxides, have been demonstrated to be highly effective catalysts for the HER. Mo2C, having high conductivity and good stability over a wide pH range, is a worthy alternative to non-precious metal electrocatalysts. Gong et al. [182] optimises a two-step method (electrospinning followed by calcination) to fabricate flexible self-supported porous electrocatalysts based on Mo carbide. They obtained nanodimensional Mo2C-CoO particles encapsulated in N-doped carbon nanofibres (denoted as Mo2C-CoO@N-CNFs), which showed bi-functional electrocatalytic activity towards both OER and HER. The self-supported porous architecture enhanced the evolution and desorption process of formed bubbles, as well as the mass transfer. Mo2C-CoO@N-CNFs showed a low cell voltage of 1.56 V at 10 mA/cm2 when directly inserted into a full cell as both the cathode and anode, making it suitable for overall water splitting (OWS) applications.

In conclusion, the most effective strategy for increasing the active sites and improving intrinsic catalytic activity, regardless of whether pure metals or compounds are involved, is to reduce the size of the metal catalyst to nanoclusters or even single atoms, arranged homogeneously on a conductive support. This maximises the exposure of the catalytic sites, thus accelerating the evolution of kinetics. In this approach, metal-support interactions play a critical role. Indeed, metal-support electronic interactions are associated with orbital rehybridisations and charge transfer across the interface, favouring the formation of new chemical bonds and the realignment of molecular energy levels. In this way, not only can particle adhesion and material stability be improved, but also catalytic properties.

Table 5 reports various examples of enriched CNFs where opportune precursors of metal NPs, also in some case in combination, were introduced into the electrospinning solutions. The CNFs enriched with nanoparticles demonstrated remarkable performance as catalysts for OER, HER and ORR, and could potentially replace noble metals.

Table 5.

Materials constituting the electrocatalyst and the used electrospun suspension; the sequence of post-electrospinning steps; the cathalysed reaction; and the relative performance.

5. Other Components (Separators, Solid State Electrolytes)

Other components of electrochemical devices that can benefit from electrospinning technology include separators and solid electrolytes. ES is a valid deposition technology for obtaining self-supporting polymer layers that can be engineered to have specific characteristics by enriching them with various types of nanomaterial during or after deposition. The separator is one of the most important components for ensuring the stability of electrochemical energy devices. An ideal separator would be highly porous, well-wetted by the electrolyte, be chemically and thermally stable, and mechanically robust [207,208,209]. Some recent results regarding electrospun composite separators for LIBs are reported in Table 6.

Table 6.

Materials constituting the LIB separator and the preparation procedure, the electrolyte uptake, and the ionic conductivity.

Lee et al. [211] prepared a three-layer nanofibre membrane consisting of (PAN containing CuO/TiO2 nanowires)/(PVDF-HFP+PMMA)/(PAN containing CuO/TiO2) via electrospinning. This membrane is intended for use as a separator in Li-ion batteries. TiO2 is an ideal ceramic additive for improving electrochemical performance thanks to its low cost, good chemical stability, and reduced volume change during device cycling. However, due to its low conductivity and slow ionic kinetics, it is difficult to use alone and is therefore often combined with other transition metal oxides. Adding CuO increases the number of oxygen vacancies on the TiO2 surface, accelerating surface reactions and boosting ionic conductivity. Consequently, combining CuO and TiO2 improves ionic conductivity and electrochemical properties simultaneously. Adding PMMA to the PVDF-HFP polymer reduces crystallinity in the middle layer, thereby improving ionic diffusivity and wettability. However, reduced crystallinity also results in lower mechanical rigidity and brittleness. As a result, the separator exhibited an electrolyte uptake of approximately 1100% and an ionic conductivity of 2.91 mS/cm.

Jafaripour et al. [215] have recently proposed an innovative approach to developing separators using electrospinning. In light of the potential structural deformation of conventional polymer-based separators at high temperatures, the authors describe a polymer-free electrospinning process for producing a silica nanofibre membrane. This straightforward process involves electrospinning a solution of tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS), ethanol (EtOH), water and hydrochloric acid (HCl), followed by thermal processing at 300 °C. The resulting separator exhibits thermal and mechanical stability, ultra-high electrolyte uptake (1566%), and significantly higher ionic conductivity (3.59 mS/cm) than classic polypropylene separators.

Another important component of an electrochemical device is the electrolyte. For safety and performance reasons, there has recently been an increasing trend towards developing full solid-state devices [216,217,218]. In this context, the role of the solid electrolyte is paramount. An effective solid electrolyte must have good intrinsic ionic conductivity, as well as good chemical, thermal, and mechanical stability. Table 7 shows some examples of electrospun solid electrolytes enriched with nanomaterials.

Table 7.

Materials constituting the solid/gel electrolyte and the preparation procedure, the specific application and the ionic conductivity.

In the field of water-based batteries, a high-performance gel electrolyte for zinc-ion batteries has been developed [222]. This involves electrospinning a poly(m-phenylene isophthalamide) solution to create a nanofibre membrane, growing ZnO nanorods on its surface using a hydrothermal method, and filling the membrane with a PVA/zinc bis(trifluoromethanesulfonimide) (Zn(CF3SO3)2) solution to form the gel electrolyte. In this composite material, the PMIA nanofibres and ZnO nanorods provide channels for Zn2+ transport. The gel-like nature of the electrolyte also endows the material with excellent mechanical properties and ensures good adhesion to the electrode. This electrolyte can also prevent the oxidative decomposition of the zinc anode, offering significant advantages in terms of device cyclability.

Gao et al. [224] developed a solid electrolyte for solid-state lithium batteries consisting of PAN nanofibres loaded with MOFs, obtained by coaxial ES. This deposition technique ensures a uniform distribution of MOFs on the PAN nanofibres, resulting in a high ionic conductivity of 1.29 mS/cm. In addition, the chemical and mechanical properties of the membrane are enhanced by the effective encapsulation of PAN nanofibres by MOF nanoparticles. This results in uniform lithium-ion deposition and prevents dendrite formation.

6. Conclusions

Electrospun nanofibres with integrated functional nanostructures are a versatile and promising class of material for direct use in electrochemical energy devices. Their unique combination of high surface area, tunable porosity, and hierarchical architecture enables enhanced mass transport, efficient charge transfer, and improved electrochemical stability. This article reviews recent advances in material design, from carbon-based frameworks and conductive polymers to hybrid composites incorporating metal oxides, sulphides, or MOFs, which have demonstrated significant improvements in device performance across batteries, supercapacitors, and fuel cells.

The direct use of electrospun nanofibres, without extensive post-processing or structural modification, offers a streamlined pathway towards scalable and cost-effective integration into energy systems. This approach aligns with the growing demand for sustainable and high-performance materials, particularly for applications requiring lightweight, flexible, and multifunctional components. Moreover, the ability to customise fibre morphology, composition, and surface functionality at the nanoscale creates new opportunities for optimising electrode/electrolyte interfaces and enhancing catalytic activity.

Despite these advances, several challenges remain. These include achieving uniformity and reproducibility in large-scale electrospinning, ensuring long-term operational stability under harsh electrochemical conditions, and integrating nanofibre-based architectures into commercial device formats. Additionally, a deeper mechanistic understanding of structure–property relationships and the synergistic effects between nanostructured components will be essential for rational design of materials.

In conclusion, electrospun nanofibres with functional nanostructures have immense potential for next-generation electrochemical energy technologies. Continued interdisciplinary efforts in materials science, electrochemistry, and device engineering will be key to unlocking their full potential and translating laboratory-scale innovations into real-world applications.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript (in alphabetical order):

| [Mo2C/C]//[Ni/C]-NMCFs | Mo2C, Ni embedded in porous N-doped multi-channel Janus carbon fibres |

| [Ni/C]@[MoC/C]-PCNFs | one-dimensional honeycomb coaxial CNFs with MoC shell and Ni core layer |

| 2-MI | 2-methylimidazole |

| 3DHPCNF | three-dimensional hollow and porous carbon nanofibre |

| AC | Activated carbon |

| AEMWE | anion exchange membrane water electrolysis |

| ATP | attapulgite |

| BIT | Bi4Ti3O12 |

| CA | Cellulose acetate |

| C-CFs | coal-based carbon fibres |

| C-CNFs | coal-based carbon nanofibres |

| CD | Ciclodestina |

| CDs | Carbon dots |

| CF | carbon fibres |

| CFC | carbon fibre cloth |

| CFO@PNCFM | CoFe2O4 nanoparticles in situ encapsulated in porous N-doped carbon nanofibres membranes |

| CFOANF | amide groups modified nitrogen-doped carbon nanofibres (ANF) combined with spinel CoFe2O4 (CFO) nanoparticles |

| CL-NCNF | Cross linked NCNF |

| CMNO | cobalt-manganese-nickel-oxide |

| CNFs | Carbon Nanofibres |

| CNS | Carbon nanosheets |

| CNTs | Carbon nanotubes |

| CoNC | carbon encapsulated Co nanoparticles |

| CPAN | electrospun carbon fibre |

| CPCNF | cavity-interconnected porous carbon nanofibres |

| CPZ | coaxial PAN@ZIF-8 nanofibre membrane |

| CQD | carbon quantum dot |

| CSNF | core–shell structured nanofibre |

| CTS | Carbon thermal shock |

| CVD | Chemical vapour deposition |

| DA | dopamine |

| EDL | Electrical Double Layer |

| EDLC | Electric Double Layer Capacitance |

| ES | Electrospinning |

| FCOS | partially sulphurised iron–cobalt oxide |

| FOCNF | Fe2O3-embedded highly graphitised carbon nanofibres |

| F-RGO | Freeze-dried reductive graphene oxide |

| GCNF | graphene-coated electrospun carbon nanofibres |

| GDLs | Gas diffusion layers |

| GO | graphene oxide |

| GOP | surface-modified PP nonwoven fabric |

| H2BDC | 1,4-benzenedicarboxylic acid |

| HCNF | hollow CNF |

| HCS | Hollow carbon hybrid spheres |

| HER | Hydrogen evolution reaction |

| H–NiSe/SnSe@NC | hollow NiSe/SnSe nanocubes within nitrogen-doped carbon nanofibres |

| HPC | hierarchical porous carbon nanofibre |

| HTMAB | hexadecyl trimethyl ammonium bromide |

| KMF-ES | electrospun prussian blue K2Mn[Fe(CN)6] electrode |

| LCNFs | Lignin/polymer CNFs |

| LDHs | Layered Double Hydroxides |

| LFP | LiFePO4 |

| LIBs | Lithium-ion batteries |

| LLTO | Li0.33La0.557TiO3 |

| MCF | multichannel carbon nanofibres |

| MCPS | Cu-mediated MoP/SnO2 carbon fibre |

| MeIM | 2-methylimidazole |

| MNCNF | N-doped CNFs with multi-channels |

| MOFs | Metal Organic Frameworks |

| M-PI CFMs | modified-polyimide composite fibrous membranes |

| MX | Mxene |

| NA | Nano arrays |

| Nb(BTC)MOF | niobium (benzene 1,3,5-tricarboxylic acid) MOFs |

| NC | nanocubes |

| NC@Ge | N-doped carbon nanofibre@germanium |

| NCF | N-doped carbon nanofibre |

| NCNFs | N-doped CNFs |

| NCNFs-H | N-doped hollow CNFs |

| NCNT | N-enriched CNT |

| NF-FTO | FeTiO3 nanoparticle-impregnated porous multichannel N-doped carbon nanofibres |

| NHCNFs | nitrogen-doped bead-chain-like hollow carbon nanofibres |

| NM@CCNF | nickel-based MOF decorated over cobalt oxide-embedded CNFs |

| NOCNF | NiO-embedded highly graphitised carbon nanofibres |

| NOPCNFs | N/O co-doping porous carbon nanofibres |

| NPC | nanoporous carbon nanostructures |

| NPCN | nitrogen-doped porous carbon nanofibres |

| NPCNF | nitrogen/phosphorus co-doped carbon fibres |

| NPs | Nanoparticles |

| NPV | Na3V2(PO4)3 |

| NRs | nanorods |

| NS | NS-co-doped |

| N-TCF/CNT | N-doped TiN/carbon composite nanofibres with carbon nanotubes |

| NWs | Nanowires |

| OC | oxidised coal |

| OER | Oxygen evolution reaction |

| ORR | Oxygen reduction reaction |

| OWS | overall water splitting |

| PA | Phytic acid |

| PAA | polyamide acid |

| PAF | Nanofibre composite separator |

| PAMAM | polyamidoamine dendrimer |

| PAN | Polyacrylonitrile |

| PANI | Polyaniline |

| PB | Prussian blue |

| PC | Pseudocapacitive |

| PCNF | porous carbon nanofibres |

| PCNFM | porous N-doped carbon nanofibre membrane |

| PDA | polydopamine |

| PEDOT | Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) polystyrene sulfonate |

| PEMs | Proton exchange membranes |

| PEO/PEG | Polyethylene glycol |

| PH | PVDF-HP |

| PIB | Potassium ion battery |

| PMIA | poly(m-phenylene isophthalamide) |

| PMMA | poly(methylmethacrylate |

| PMMNFS | PAN/MeIM/PMMA |

| PMnG(γ) | γ-CD/graphene-based porous CNF with MnO2 |

| PPy | polypyrrole |

| PS | polystyrene |

| PSN | Polymer-less silica nanofibres |

| PTA | terephthalic acid |

| PTFE | Polytetrafluoroethylene |

| PVA | polyvinyl alchohol |

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene fluoride |

| PVDF-CTFE | poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-chlorotrifluoroethylene) |

| PVDF-HFP | Poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene) |

| PVP | Polyvynilylpirrolidone |

| Py | pyrrole |

| rGO, RGO | reduced graphene oxide |

| RHE | Reference Hydrogen Electrode |

| RSF | Regenerated silk fibroin |

| SA | Single atoms |

| SBR | Carboxylic butadiene-styrene layex |

| SCs | Supercapacitors |

| SEI | Solid electrolyte interphase |

| SFN | SPEEK, SrFeO3-NH2 nano needles composite obtained by electrospinning |

| SIBs | Sodium-ion batteries |

| SN | Succinonitrile |

| SPEEK | Sulfonated poly(ether ketone) |

| SSC | Symmetric supercapacitor |

| SSE | Solid state electrolytes |