Abstract

The purpose of this work was to study water-soluble platinum complexes as potential therapeutic agents. We used water-soluble platinum(II) complexes containing sulfonated N-heterocyclic carbene ligands (NHC), applied on two human cell models: human NB4 acute promyelocytic leukemia and PC3 prostatic cancer cells. We studied the toxic effects on these two types of human tumor cells. We analyzed metabolic activity, membrane damage, cell cycle, DNA fragmentation and programmed cell death. In human NB4 leukemia cells, the water-soluble dimethyl NHC complex 5Me proved highly toxic. It extinguished cell metabolism at 1 mM for 24 h. This treatment gave rise to the presence of fragmented DNA (subdiploid DNA). This compound promoted programed cell death in 60% of the cells. At longer times, the treatments produced neither higher fragmentation of DNA nor augmented apoptosis. 5Me complex, at 100 µM, showed slight toxicity on NB4 cells. In PC3 cells, dimethyl complex 5Me (1 mM for 24 h) is less toxic (reduced DNA fragmentation and programmed cell death) than in NB4 cells. Mono-NHC complexes 4 and 5 treatments at a high concentration for 24 h on PC3 cells produced apoptosis (30% of the cells) but their damage on cell permeability and DNA fragmentation was weak. Thus, PC3 cells are more resistant to NHC platinum(II) complexes than NB4 cells.

1. Introduction

Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) is a pathology of white blood cells. It proceeds with accumulation of immature cells (promyelocytes) in peripheral blood and bone marrow. NB4 is an established human acute promyelocytic leukemia cell line with a t(15;17) chromosomal translocation [1]. NB4 cells are resistant to treatments with all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) and arsenic trioxide (ATO). Consequently, other cytotoxic treatments are under investigation for one that might overcome malignant progression and resistance [2,3,4].

The prostate is an organ that can show hypertrophic growth. Monitoring of the gland is relevant in order to prevent malignant tumor development. Human malignant prostatic tumor PC3 cells overcome hormone-dependent therapy. Metastatic human prostate cancer is therapy-resistant [5]. The PC3 cell line, which does not express androgen receptors and shows features of an aggressive cancer [6], can hence be applied for exploring therapies against resistant human prostate carcinomas [7].

Cisplatin (cis-[diamminedichloroplatinum(II)]) is a common antitumor drug [8,9,10,11]. The antitumor action and effects of cisplatin and other platinum-containing drugs have been widely studied, and their effectiveness has given rise to an extensive use in therapy against cancer. It is accepted that cisplatin acts following a mechanism that involves an initial exchange of the chloride ligands by water, followed by the binding of the platinum to DNA. Subsequently, the DNA becomes distorted, preventing transcription and eventually inducing apoptosis of the tumor cells. This mechanism also applies to related complexes such as carboplatin and oxaliplatin [10,11,12,13].

Therapy treatment with cisplatin does not affect only the cancer cells, giving rise to some deleterious effects (infertility, anemia, nephrotoxicity, etc.). Additionally, some cancer cells exhibit both intrinsic and acquired resistance to therapeutic drugs [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. Cisplatin and derived complexes (carboplatin, oxaliplatin and others) are currently useful in the therapeutic treatment of several kinds of cancer showing diverse cytotoxicity and resistance [24]. It is the general aim of cancer research to synthesize and develop platinum complexes that result in more efficient and selective treatment, in order to reduce both the dosage and time in treatment and thus lower the risk of acquiring resistance.

Therefore, new alternative Pt complexes should be developed to reduce toxicity and avoid persistent resistance to antitumor treatments. Different strategies concerning the design of such complexes consider the presence of different groups in the molecule, the mechanisms of action and the type of ligands bound to the molecule [10,11,18,19,20,21,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35].

Here, we explore the cytotoxicity induced by some sulfonated water-soluble N-heterocyclic carbene platinum(II) complexes [36,37] on two human tumor cell lines (NB4 and PC3). We comparatively study the cytotoxic effects in relation to cell viability, membrane permeability, DNA degradation and apoptosis. This work can provide relevant knowledge about the therapeutic efficacy of platinum derivatives as antitumor compounds in leukemias and prostatic neoplasms.

2. Materials and Methods

Compounds

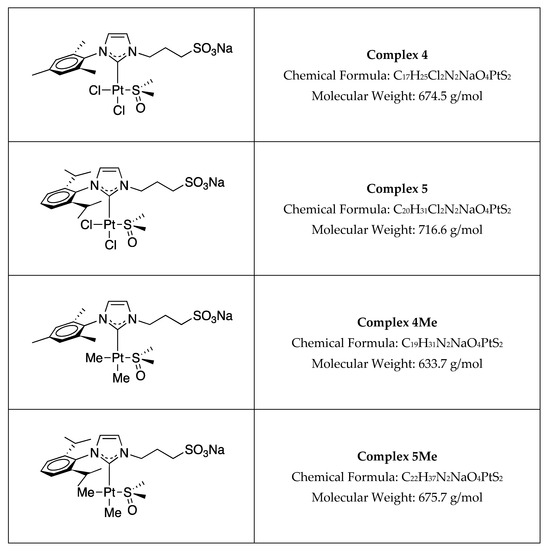

Sulfonated water-soluble N-heterocyclic carbene platinum(II) [NHC Pt(II)] complexes (Figure 1) were prepared as previously reported [36,37].

Figure 1.

Structure of the complexes used in this study.

Cell culture

We obtained PC3 cell lines from the ATCC (American Type Cell Collection, Manassas, VA, USA; CRL-1435). They were cultured for about 24 h prior to treatment, at 37 °C under a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2, in RPMI 1640 medium with GlutaMAXTM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Merck Life Science, S.L.U., Madrid, Spain), 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin and 0.25 μg/mL amphotericin B.

We obtained NB4 human acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) cells from the American Type Culture Collection [38,39]. They were maintained in culture at a density of 5 × 105 cells/mL in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 0.02 mg/mL gentamicin, at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Treatments

NB4 cells (5 × 105/mL) and PC3 cells (8 × 103/cm2) were treated with either 100 μM or 1 mM of different compounds, listed in Figure 1, for 24 h and 48 h (NB4) or 24 h and 72 h (PC3).

Cell viability study. Cell viability of NB4 and PC3 cells was determined by measuring the impermeability to propidium iodide (PI) by flow cytometry. After treatments, 2.5 × 105 cells were washed with 500 μL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in 300 μL PBS. Then, 15 μL propidium iodide (Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany) was added and the fluorescence was measured using a FACScalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA).

The characteristic loss of DNA (sub-G0/G1 peak) in the apoptotic process was analyzed by flow cytometry on permeabilized (0.1% Nonidet-P40) and PI-stained (50 μg/mL PI) cells.

Metabolic activity. We tested the cell metabolic activity using the MTT (3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) colorimetric assay that detects mitochondrial succinate dehydrogenase activity. After treatments, cells seeded in 96-well microplates were incubated with 10 μL MTT labeling reagent (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) for 4 h and then 100 μL of solubilization solution was added. A microplate reader (ELx800, BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA) rendered measurements of absorbance which correlates to the number of viable cells.

Cytotoxicity. Cell death by necrosis was determined by flow cytometry through the permeability to propidium iodide (PI, 20 μg/mL) in a FACScan (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA). The loss of DNA (sub-G0/G1 peak) characteristic of the apoptotic process was analyzed by flow cytometry of permeabilized (0.1% Nonidet-P40) and PI-stained (50 μg/mL PI) cells.

Apoptosis. Apoptosis was measured by the Annexin-V-FITC cytometry assay (Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit, BioVision, Mountain View, CA, USA). After treatments, 2.5 × 105 cells were centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 5 min and incubated with 500 μL 1× Annexin V Binding Buffer and 1 μL Annexin V-FITC for 5 min at room temperature in the dark. Then, 10 μL PI was added and cell fluorescence was measured using a flow cytometer. The results were processed using WinMDI 2.8 software.

Statistical analysis. Data are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean from at least three independent experiments. Treated samples were compared to control untreated cells using Student’s t-test (one tail, heteroscedastic). Differences were considered significant for p values below 0.05.

3. Results

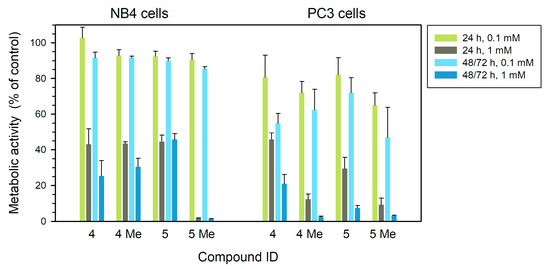

In human NB4 leukemia cells, the water-soluble dimethyl NHC complex 5Me showed high toxicity at 1 mM, abolishing the metabolic activity after a 24 h treatment (p < 0.0001). At a lower concentration (100 µM), the reduction in metabolic activity accounted for 10–15%, giving results down to 85–90% of the initial metabolic activity after treatments for 24 h or longer (p < 0.05 and p < 0.001, respectively) (Figure 2, left panel). Complex 4 and its methylated derivative 4Me at 1 mM both showed similar effects, reducing metabolic activity down to around 45% and 30% in treatments for 24 h and 48 h, respectively (Figure 2, left panel). In all these cases, the reduction with respect to controls is significant with values of p < 0.001 or p < 0.0001.

Figure 2.

Metabolic activity (% related to control) measured by MTT assay of human leukemia NB4 (left) and tumor prostatic PC3 (right) cells treated with each of the four compounds at different concentrations for 24 h, 48 h (NB4) or 72 h (PC3). Statistical significance is set at p = 0.05 or lower, calculated by comparing treated and control untreated samples.

In the case of human prostate cancer PC3 cells (right panel of the figure), the methylated forms of compounds, 4Me and 5Me, are highly toxic at 1 mM even in short 24 h treatments (p < 0.0001), with a reduction down to 3% of metabolic activity after a long treatment. At 100 µM during 72 h, both methylated forms 4Me and 5Me reduced metabolic activity to 60% and 45% of the control, respectively (p < 0.05) (Figure 2, right panel). Compounds 4 and 5 showed a significant reduction in metabolic activity after treatments at 1 mM for 72 h, down to around 20% and 10%, respectively (p < 0.05 and p < 0.0001, respectively).

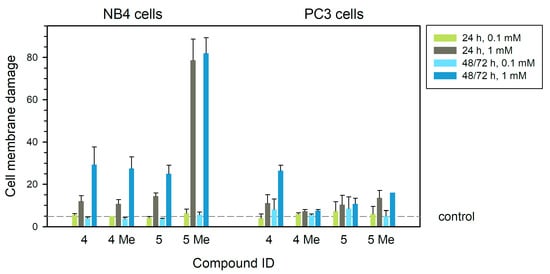

With respect to membrane permeability, the 5Me compound showed a strong effect at 1 mM on NB4 cells producing 78–80% of cells with membrane damage (measured as permeability to propidium iodide) at 24 h or longer (p < 0.01). Compounds 4, 4Me and 5 induced membrane damage accounting for 25–29% in treatments at a concentration of 1 mM for 48 h (Figure 3, left panel) (p < 0.05). In PC3 cells, alteration of membrane permeability was not so relevant, with the greatest effect produced by compound 4 (1 mM) at 72 h (26% of cells altered) (p < 0.01) (Figure 3, right panel). Compounds 4Me and 5 produced less membrane damage (7.5–10.7%, Figure 3) either at low or high concentration. The toxic effects of these compounds on membrane damage are more relevant in human NB4 leukemia cells (Figure 3, left panel) than in PC3 prostate cells (Figure 3, right panel).

Figure 3.

Cell membrane damage studied by permeability to PI assay (% tumor cells that incorporated PI) of human leukemia NB4 (left) and tumor prostatic PC3 (right) cells treated with each of the four compounds at different concentrations for 24 h, 48 h (NB4) or 72 h (PC3). Dashed line is drawn at the average value of controls (treatment without any compounds). Statistical significance is set at p = 0.05 or lower, calculated by comparing treated and control untreated samples.

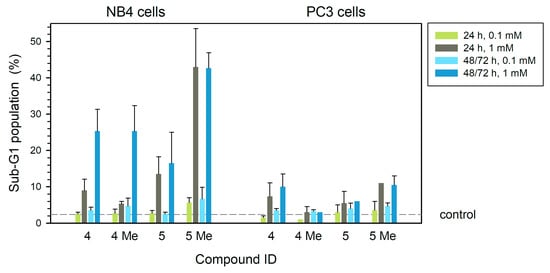

These treatments produced DNA fragmentation evidenced by the presence of subdiploid DNA, being particularly important in the case of NB4 cells treated with 1 mM compound 5Me at 24 h (43%, left panel in Figure 4) (p < 0.05). Compounds 4 and 4Me produced 25% of cells in sub-G1 phase showing DNA fragmentation after treatments at 1 mM for 48 h (p < 0.05). In PC3 cells, the effect of these compounds was not so relevant since the compound 5Me produced just 10% of fragmented DNA at 1 mM when applied for 24 h (p < 0.05) or longer (Figure 4, right panel).

Figure 4.

DNA fragmentation in human leukemia NB4 (left) and tumor prostatic PC3 (right) cells (% cells in sub-G1 phase of the cell cycle) after treatment with each of the four compounds at different concentrations for 24 h, 48 h (NB4) or 72 h (PC3). Dashed line is drawn at the average value of controls (treatment without any compounds). Statistical significance is set at p = 0.05 or lower, calculated by comparing treated and control untreated samples.

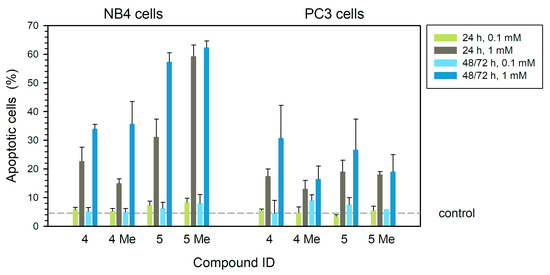

Apoptosis induction by these complexes affects 60% of the total cell population in NB4 cells treated with 5Me compound for 24 h at 1 mM (p < 0.01) (Figure 5, left). In longer treatments, the apoptosis level was slightly higher (64%, p < 0.001) (left panel in Figure 5) (p < 0.001). At 100 µM, toxic effects were reduced (Figure 5, left). Complex 5 also produced significant apoptosis in treatments for 24 h (p < 0.01) or longer (p < 0.001) at a concentration of 1 mM (Figure 5, left). At 1 mM, complex 5 showed high apoptosis levels (around 58%) after long treatments (p < 0.001), while shorter treatments produced 30% apoptotic cells (Figure 5, left panel) (p < 0.01). The complexes 4 and 4Me at 1 mM rendered 35% apoptosis at 48 h (Figure 5, left) (p < 0.001 and p < 0.05, respectively). In PC3 cells, complexes 4 and 5 showed the highest apoptotic effect (around 30 and 25%, respectively) at 1 mM and 72 h (Figure 5, right). The methylated 4Me and 5Me compounds gave less than 20% apoptotic cells in long treatments. (Figure 5, right).

Figure 5.

Apoptosis in human leukemia NB4 (left) and tumor prostaticPC3 (right) cells as analyzed by annexin V-PI (% apoptotic cells) after treatment with each of the four compounds at different concentrations for 24 h, 48 h (NB4) or 72 h (PC3). Dashed line is drawn at the average value of controls (treatment without any compounds). Statistical significance is set at p = 0.05 or lower, calculated by comparing treated and control untreated samples.

In summary, in PC3 prostatic cells, the toxic effects of the dimethyl 5Me complex at a high concentration (1 mM) are less strong than in leukemia cells. In these PC3 cells, treatments with mono-NHC complexes 4 and 5 at a high concentration for 24 h induced apoptosis but their effects on cell membrane permeability and DNA fragmentation were weak (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

4. Discussion

Chemotherapy is a general approach to treat cancer and metastases [40]. The prevention of tumor development and cell proliferation uses different chemotherapy compounds. Among them, cisplatin is extensively applied, being the first Pt-based anti-cancer compound used in therapy [41] which has proved effective on breast, testis, ovary, lung and colorectal cancers. However, it exerts general toxicity in tissues when applied for long time periods.

To overcome systemic toxicity, several cisplatin analogs are available nowadays, such as carboplatin or oxaliplatin. Moreover, the development of other new derivatives aims to achieve a higher effectivity and a reduced general toxicity [42,43]. Thus, newly formulated cisplatin derivatives have been recently developed and tested for clinical application and therapy. The final aim is to achieve therapy with higher efficacy and to reduce cellular toxicity and resistance [44,45,46].

We have thus tried to understand how alternative chemotherapy compounds related to cisplatin may be applied in these two cancer cell line models. We have tested several sulfonated water-soluble NHC platinum(II) complexes. The types of complexes were chosen because of the relative inertness, lack of coordinating capability of the hydrophylic moiety (i.e., the sulfonate group) and the well-known robustness of the NHC–metal bonds [47,48].

We tested the metabolic viability by MTT assay (Figure 2). In human leukemia NB4 cells, the compound 5Me at 1 mM abolished metabolic activity at 24 h of treatment. Thus, 5Me seemed to act as a highly effective inhibitor of metabolic activity in this APL cell line.

In prostatic tumor PC3 cells, the compounds 4Me and 5Me showed a clear reduction in metabolic activity (measured by MTT assay) in treatments at 1 mM even at 24 h, while at 0.1 mM they reduced metabolic activity by 30–35% (Figure 2).

In brief, none of the tested compounds showed relevant membrane damage (studied by permeability to PI) after treatments at 0.1 mM or 1 mM concentrations in human prostate tumor PC3 cells (Figure 3). Only complex 4 showed around 28% of membrane damage after the addition to PC3 cells in culture at 1 mM for 72 h.

In human leukemia NB4 cells, however, compounds 4, 4Me and 5 all showed around 20–30% of membrane damage when used at 1 mM for 48 h. In leukemia NB4 cells, compound 5Me produced higher damage (80% PI permeability) at 1 mM in treatments for 24 h (Figure 3). Thus, compounds 4, 4Me and 5 seemed to alter cell membranes to a more reduced extent than complex. 5Me complex showed an actual toxic effect on leukemia cells when treated for 24 h or longer.

With respect to DNA fragmentation (Figure 4), compounds 4 and 5Me showed the highest effect on PC3 cells at 1 mM, while compounds 4Me and 5 showed a very low effect.

In NB4 cells, all the tested compounds at 1 mM produced some DNA fragmentation, being more relevant in treatments for 48 h. Compound 5Me at 1 mM already showed relevant effects at 24 h treatments (43% of sub-G1 population) (Figure 4).

The induction of apoptosis was clearly visible in both cell lines when they were treated with sulfonated water-soluble N-heterocyclic carbene platinum(II) [NHC Pt(II)] complexes at a concentration of 1 mM. One could not observe significant levels of apoptosis in treatments at a concentration of 0.1 mM, neither in PC3 cells nor in NB4 cells.

Leukemia NB4 cells seemed to be more sensitive than prostate tumor PC3 cells (Figure 5). Compounds 5 and 5Me (at 1 mM) showed the highest effect on NB4, mainly in treatments for 48 h. The dimethyl NHC 5Me complex strongly induces apoptosis on NB4 cells even at 24 h, without a further increase in longer treatments. The effect is clearly visible at a concentration of 1 mM. Although this compound at 0.1 mM on NB4 cells produced a slight reduction in cell viability, there was no significant effect on permeability to PI nor on DNA degradation even in long treatments.

In prostate tumor PC3, the induction of apoptosis by either of these four compounds did not exceed 30% of the total cell population (Figure 5) even in 72 h treatments.

Thus, the effects of some of these compounds may be taken into account in eventual novel therapy treatments, mainly for APL processes. Water-soluble dimethyl NHC 5Me complex and 5 complex effectiveness might be dependent on its own structural nature, on the increased lipophilic balance (complex 5Me being more soluble than 5) in comparison with the other complexes tested, or even on the possibility that the incorporation of a methyl group could make its action easier, at least in leukemia cells.

The toxicity of these sulfonated water-soluble N-heterocyclic carbene platinum(II) [NHC Pt(II)] complexes may be compared to the effects of cisplatin on these two tumor cell lines. The toxic effects of these Pt complexes are probably dependent on their binding to DNA, similarly to cisplatin [10,11,36,37].

Cisplatin induces cytotoxicity through DNA adduct formation, oxidative stress, transcriptional factors (p53 and AP-1), cell cycle regulation, stress signaling and apoptosis in APL cells [49]. Similarly, other platinum derivative complexes arrest the cell cycle in the S and G2 phases, induce DNA damage, increase ROS production and perturb mitochondrial bioenergetics in PC3 cells [50].

We estimated the IC50 for the different [NHC Pt(II)] complexes used in this study. We used MTT results (metabolic activity) obtained in our study on PC3 and NB4 cells using different concentrations and treatments at different times, In human PC3 prostate cancer cells, we obtained data ranging from around 0.7 mM for complex 4, 0.4 mM for complex 4Me, to 0.5 mM for complex 5 and 0.3 mM for complex 5Me in treatments at 24 h. In human APL NB4 cells, the estimation of IC50 renders values of around 0.7–0.8 mM for complexes 4, 4Me, 5 and 5Me at 24 h.

Some authors have estimated the IC50 values for cisplatin in PC3 cells obtaining different results (1.23 µg/mL [51]; 98.21 µg/mL [52]). In NB4 cells, others reported the IC50 to be in the range of 0.4 and 6.2 µg/mL [49,53].

The IC50 values can be dependent on the method used for their determination, time of treatment and cell type assayed. The evaluation of the differences in IC50 must keep in mind the condition used for its determination.

In order to correlate the functional activity of the four compounds and their structural properties, we used several cheminformatic platforms to estimate molecular structure, lipophilicity, water solubility, ability to interact with P-glycoprotein or P450 cytochromes, and to induce mutations on DNA. These predictions are shown in Supplementary Material (Figures S1–S4).

Therefore, the use of the studied complexes for more advanced clinical purposes should consider the different resistance and effects shown by PC3 and NB4 cells. Moreover, further studies on these complexes could provide insight into new strategies for overcoming the death-resistance mechanisms of human tumor prostatic and leukemia cells.

5. Conclusions

Different N-heterocyclic carbene platinum(II) complexes were tested for antitumor activity in two tumor lines. Water-soluble dimethyl NHC 5Me is highly toxic in both PC3 and NB4 cells. This dimethyl NHC 5Me compound showed stronger effects on NB4 leukemia cells in comparison to PC3 tumor prostatic cells in the conditions of concentration and time used in this work. NB4 cells are more sensitive to NHC platinum (II) complexes than prostatic PC3 cells (higher effects on membrane damage, DNA fragmentation and apoptosis induction). Complex 5Me showed high effects on DNA fragmentation, membrane alteration and programmed cell death of NB4 leukemia cells.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/compounds5040053/s1, Figure S1: Geometric properties of the molecules. Molecular mass was calculated in both ChemSketch and Jmol. Volume and surface area are were measured on the solvent-excluded molecular surface computed in Jmol. Topological polar surface area (TPSA) was calculated in Swiss-ADME; Figure S2: Estimation of lipophilicity. Four algorithms (XLOGP3, WLOGP, MLOGP, Silicos-IT) were averaged in the Consensus logP provided by SwissADME. ALOGPS 2.1 method in Virtual Computational Chemistry Laboratory provided another estimate. Additionally, ALOGPS 2.1 was provided by OCHEM and Bernard Testa’s Virtual logP; Figure S3: Estimation of solubility in water. Logarithm of solubility in nmol per litreliter was estimated by several methods in prediction servers: ESOL, Ali and SILICOS-IT in Swiss-ADME; ALOGPS 2.1 method in Virtual Computational Chemistry Laboratory; ALOGPS 2.1 method in OCHEM (a) and solubility based on logP and melting point in OCHEM (b); Figure S4: Estimation of potential as substrate for glycoprotein P and inhibitor of the five major members of the cytochrome P450 family that are responsible for more than 90% of the metabolism of clinical drugs. All estimates were obtained at SwissADME. Data in the outer circle mean positive action, while those in the inner circle mean poor estimated activity. The Supplementary Materials include methods and results regarding the exploration of molecular properties of the platinum compounds (size, geometry, as well as predicted lipophilicity, solubility, mutagenicity and pharmacokinetics), which are considered in the discussion section.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.T., J.C.F., E.d.J. and J.C.D.; methodology, V.R., E.A.B., A.I.G.-P. and J.C.D.; Software, V.R. and A.H.; validation, A.H. and J.C.D.; formal analysis, A.H., M.C.T., J.C.F., E.d.J. and J.C.D.; investigation, E.A.B., V.R., M.C.T., J.C.F., E.d.J. and J.C.D.; resources, M.C.T., J.C.F., E.d.J., A.H. and J.C.D.; data curation, V.R. and A.H.; writing—original draft preparation, A.H. and J.C.D.; writing—review and editing, A.H. and J.C.D.; visualization, V.R. and A.H.; supervision, M.C.T., A.I.G.-P. and J.C.D.; project administration, J.C.D.; funding acquisition, M.C.T., A.H., A.I.G.-P. and J.C.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Financial support of this work was in part by grants from F.I.S. PI060119, CCG10-UAH/SAL-5966, PID2020-114637GB-I00 and UAH2011/BIO-006.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study. Human or animal samples being used in this study were supplied by legal commercial companies that accomplish all the requirements for their use and supply. PC3 cell line was obtained from the ATCC (American Type Cell Collection, Manassas, VA, USA; CRL-1435). NB4 human acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection [37,38]. FBS was obtained from commercial companies that accomplish all the requirements for its use and supply.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to no patients being involved in this study. PC3 cell line was obtained from the ATCC (American Type Cell Collection, Manassas, VA, USA; CRL-1435). NB4 human acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection [37,38].

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in FigShare. at 10.6084/m9.figshare.30209251.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Isabel Trabado for her technical assistance in cytometry (Unidad de Cultivos. C.A.I. Medicina-Biología. Universidad de Alcalá). Part of this work has previously been communicated [V. Rubio, E.A. Baquero, M.C. Tejedor, J.C. Flores, E. de Jesus, A. Herráez, A.I. García-Pérez, J.C. Diez. Differential cytotoxic effects of N-heterocyclic carbene platinum(II) complexes on prostatic tumor PC3 and leukemia NB4 cells] as a poster (P-08.2-28) in the 47th FEBS Congress, 8–12 July 2023, Tours, France [FEBS Open Bio 13 (Suppl.2) (2023) 210. doi: 10.1002/2211-5463.13646].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

- The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

APL, acute promyelocytic leukemia; Annexin V-FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate coupled to annexin V; MTT, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide; NHC; N-heterocyclic carbene ligand.

References

- Lanotte, M.; Martin-Thouvenin, V.; Najman, S.; Balerini, P.; Valensi, F.; Berger, R. NB4, a maturation inducible cell line with t(15;17) marker isolated from a human acute promyelocytic leukemia (M3). Blood 1991, 77, 1080–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, V.; García-Pérez, A.I.; Tejedor, M.C.; Herráez, A.; Diez, J.C. Esculetin neutralises cytotoxicity of t-BHP but not of H2O2 on human leukaemia NB4 cells. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 9491045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, V.; García-Pérez, A.I.; Herráez, A.; Tejedor, M.C.; Diez, J.C. Esculetin modulates cytotoxicity induced by oxidants in NB4 human leukemia cells. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 2017, 69, 700–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, V.; García-Pérez, A.I.; Herráez, A.; Diez, J.C. Different roles of Nrf2 and NFκB in the antioxidant imbalance produced by esculetin or quercetin on NB4 leukemia cells. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2018, 294, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavridi, F.; Karapanagiotou, E.M.; Syrigos, K.N. Targeted therapeutic approaches for hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2010, 36, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuu, C.P.; Kokontis, J.M.; Hiipakka, R.A.; Liao, S. Modulation of liver X receptor signalling as novel therapy for prostate cancer. J. Biomed. Sci. 2007, 14, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaighn, M.E.; Narayan, K.S.; Ohnuki, Y.; Lechner, J.F.; Jones, L.W. Establishment and characterization of a human prostatic carcinoma cell line (PC3). Investig. Urol. 1979, 17, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, B.; VanCamp, L.; Trosko, J.E.; Mansour, V.H. Platinum compounds: A new class of potent antitumour agents. Nature 1969, 222, 385–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.K. A histochemical approach to the mechanism of action of cisplatin and its analogues. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1993, 41, 1053–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuertes, M.A.; Castilla, J.; Alonso, C.; Pérez, J.M. Cisplatin biochemical mechanism of action: From cytotoxicity to induction of cell death through interconnections between apoptotic and necrotic pathways, Curr. Med. Chem. 2003, 10, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasari, S.; Tchounwou, P.B. Cisplatin in cancer therapy: Molecular mechanisms of action. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 740, 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartalou, M.; Essigmann, J.M. Recognition of cisplatin adducts by cellular proteins. Mutat. Res. 2001, 478, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartalou, M.; Essigmann, J.M. Mechanisms of resistance to cisplatin. Mutat. Res. 2001, 478, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruggiero, A.; Trombatore, G.; Triarico, S.; Arena, R.; Ferrara, P.; Scalzone, M.; Pierri, F.; Riccardi, R. Platinum compounds in children with cancer: Toxicity and clinical management. Anticancer Drugs 2013, 24, 1007–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manohar, S.; Leung, N. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity: A review of the literature. J. Nephrol. 2018, 31, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casanova, A.G.; Hernández-Sánchez, M.T.; López-Hernández, F.J.; Martínez-Salgado, C.; Prieto, M.; Vicente-Vicente, L.; Morales, A.I. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy of clinically tested protectants of cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 76, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolmaleki, S.; Khaksar, S.; Aliabadi, A.; Panjehpour, A.; Motieiyan, E.; Marabello, D.; Faraji, M.H.; Beihaghi, M. Cytotoxicity and mechanism of action of metal complexes: An overview. Toxicology 2023, 492, 153516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.W.; Pouliot, L.M.; Hall, M.D.; Gottesman, M.M. Cisplatin resistance: A cellular self-defense mechanism resulting from multiple epigenetic and genetic changes. Pharmacol. Rev. 2012, 64, 706–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breglio, A.M.; Rusheen, E.; Shide, D.; Fernandez, K.A.; Spielbauer, K.K.; McLachlin, K.M.; Hall, M.D.; Amable, L.; Cunningham, L.L. Cisplatin is retained in the cochlea indefinitely following chemotherapy. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojanovska, V.; McQuade, R.; Rybalka, E.; Nurgali, K. Neurotoxicity associated with platinum-based anti-cancer agents: What are the implications of copper transporters? Curr. Med. Chem. 2017, 24, 1520–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biersack, B.; Schobert, R. Current state of platinum complexes for the treatment of advanced and drug-resistant breast cancers. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1152, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashrafizadeh, M.; Zarrabi, A.; Hushmandi, K.; Hashemi, F.; Moghadam, E.R.; Owrang, M.; Hashemi, F.; Makvandi, P.; Goharrizi, M.A.S.B.; Najafi, M.; et al. Lung cancer cells and their sensitivity/resistance to cisplatin chemotherapy: Role of microRNAs and upstream mediators. Cell. Signal. 2021, 78, 109871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tendulkar, S.; Dodamani, S. Chemoresistance in ovarian cancer: Prospects for new drugs. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2021, 21, 668–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štarha, P.; Vančo, J.; Trávníček, Z.; Hošek, J.; Klusáková, J.; Dvořák, Z. Platinum(II) Iodido Complexes of 7-Azaindoles with Significant Antiproliferative Effects: An Old Story Revisited with Unexpected Outcomes. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.K.; Broomhead, J.A.; Fairlie, D.P.; Whithouse, M.W. Platinum drugs: Combined anti-lymphoproliferative and nephrotoxicity assays in rats. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 1980, 4, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippard, S.J. New chemistry of an old molecule: Cis-[Pt(NH3)2Cl2]. Science 1982, 218, 1075–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfgang, G.H.; Dominick, M.A.; Walsh, K.M.; Hoeschele, J.D.; Pegg, D.G. Comparative nephrotoxicity of a novel platinum compound, cisplatin, and carboplatin in male Wistar rats. Fundam. Appl. Toxicol. 1994, 22, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelland, J.L. The resurgence of platinum-based cancer chemotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2007, 7, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Li, X.; Wang, W.; Zhang, R.; Deng, L. Metal-N-heterocyclic carbene complexes as anti-tumor agents. Curr. Med. Chem. 2014, 21, 1220–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, T.C.; Suntharalingam, K.; Lippard, S.J. The next generation of platinum drugs: Targeted Pt(II) agents, nanoparticle delivery, and Pt(IV) prodrugs. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 3436–3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, R.G.; Marmion, C.J. Toward multi-targeted platinum and ruthenium drugs—A new paradigm in cancer drug treatment regimens? Chem. Rev. 2018, 119, 1058–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsvetkova, D.; Ivanova, S. Application of approved cisplatin derivatives in combination therapy against different cancer diseases. Molecules 2022, 27, 2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebwohl, D.; Canetta, R. Clinical development of platinum complexes in cancer therapy: An historical perspective and an update. Eur. J. Cancer 1998, 34, 1522–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dilruba, S.; Kalayda, G.V. Platinum-based drugs: Past, present and future. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2016, 77, 1103–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treskes, M.; van der Vijgh, W.J. WR2721 as a modulator of cisplatin- and carboplatin-induced side effects in comparison with other chemoprotective agents: A molecular approach. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 1993, 33, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baquero, E.A.; Silbestri, G.F.; Gómez-Sal, P.; Flores, J.C.; de Jesús, E. Sulfonated water-soluble N-heterocyclic carbene silver(I) complexes: Behavior in aqueous medium and as NHC-transfer agents to platinum(II). Organometallics 2013, 32, 2814–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baquero, E.A.; Flores, J.C.; Perles, J.; Gómez-Sal, P.; de Jesús, E. Water-soluble mono- and dimethyl N-heterocyclic carbene platinum(II) complexes: Synthesis and reactivity. Organometallics 2014, 33, 5470–5482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeano, E.; Nieto, E.; García-Pérez, A.I.; Delgado, M.D.; Pinilla, M.; Sancho, P. Effects of the antitumoural dequalinium on NB4 and K562 human leukemia cell lines. Mitochondrial implication in cell death. Leuk. Res. 2005, 29, 1201–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho, P.; Galeano, E.; Nieto, E.; Delgado, M.D.; García-Pérez, A.I. Dequalinium induces cell death in human leukemia cells by early mitochondrial alterations which enhance ROS production. Leuk. Res. 2007, 31, 969–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronina, T.; Bartmanska, A.; Popłonski, J.; Rychlicka, M.; Sordon, S.; Filip-Psurska, B.; Milczarek, M.; Wietrzyk, J.; Huszcza, E. Prenylated flavonoids with selective toxicity against human cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xu, C.; Gao, X.; Yao, Q. Platinum-based drugs for cancer therapy and anti-tumor strategies. Theranostics 2022, 12, 2115–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dibas, A.; Howard, J.; Anwar, S.; Stewart, D.; Khan, A. Borato-1,2-diaminocyclohexane platinum (II), a novel anti-tumor drug. Biochem. Biophy. Res. Commun. 2000, 270, 383–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Singh, V.J.; Chawla, P.A. Advancements in the use of platinum complexes as anticancer agents. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2022, 22, 821–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahsavari, H.R.; Hu, J.; Chamyani, S.; Sakamaki, Y.; Aghakhanpour, R.B.; Salmon Ch Fereidoonnezhad, M.; Mojaddami, A.; Peyvasteh, P.; Beyzavi, H. Fluorinated cycloplatinated(II) complexes bearing bisphosphine ligands as potent anticancer agents. Organometallics 2021, 40, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backman-Blanco, G.; Valdés, H.; Ramírez-Apan, M.T.; Cano-Sanchez, P.; Hernandez-Ortega, S.; Orjuela, A.L.; Alí-Torres, J.; Flores-Gaspar, A.; Reyes-Martínez, R.; Morales-Morales, D. Synthesis of Pt(II) complexes of the type [Pt(1,10-phenanthroline)(SArFn)2] (SArFn = SC6H3-3,4-F2; SC6F4-4-H.; SC6F5). Preliminary evaluation of their in vitro anticancer activity. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2020, 211, 111206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybak, L.P.; Alberts, I.; Patel, S.; Al Aameri, R.F.H.; Ramkumar, V. Effects of natural products on cisplatin ototoxicity and chemotherapeutic efficacy. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2023, 19, 635–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkinson, M.N.; Christian Richter, C.; Schedler, M.; Glorius, F. An overview of N-heterocyclic carbenes. Nature 2014, 510, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesterov, V.; Reiter, D.; Bag, P.; Frisch, P.; Holzner, R.; Porzelt, A.; Inoue, S. NHCs in main group chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 9678–9842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Tchounwou, P.B. Molecular mechanisms of cisplatin cytotoxicity in acute promyelocytic leukemia cells. Oncotarget 2025, 6, 40734–40746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafees, M.; Hanif, M.; Muhammad Asif Khan, R.; Faiz, F.; Yang, P. A dual action platinum(IV) complex with self-assembly property inhibits prostate cancer through mitochondrial stress pathway. ChemMedChem 2024, 19, e202400289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.M.; Nady, S.; Shafaa, M.W.; Khalil, M.M. Radiation and chemotherapy variable response induced by tumor cell hypoxia: Impact of radiation dose, anticancer drug, and type of cancer. Radiat. Environ. Biophys. 2022, 61, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sun, Y.; Wang, P.; Yang Ch Li, S. Reduced pim-1 expression increases chemotherapeutic drug sensitivity in human androgen-independent prostate cancer cells by inducing apoptosis. Exp. Ther. Med. 2019, 18, 2731–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, W.-C.; Chang, S.-L.; Chen, T.-Y.; Chen, J.-S.; Tsao, C.-J. Comparison of in vitro growth-inhibitory activity of carboplatin and cisplatin on leukemic cells and hematopoietic progenitors: The myelosuppressive activity of carboplatin may be greater than its antileukemic effect. Jap. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000, 30, 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).