Improvement of Structural, Elastic, and Magnetic Properties of Vanadium-Doped Lithium Ferrite

Abstract

1. Introduction

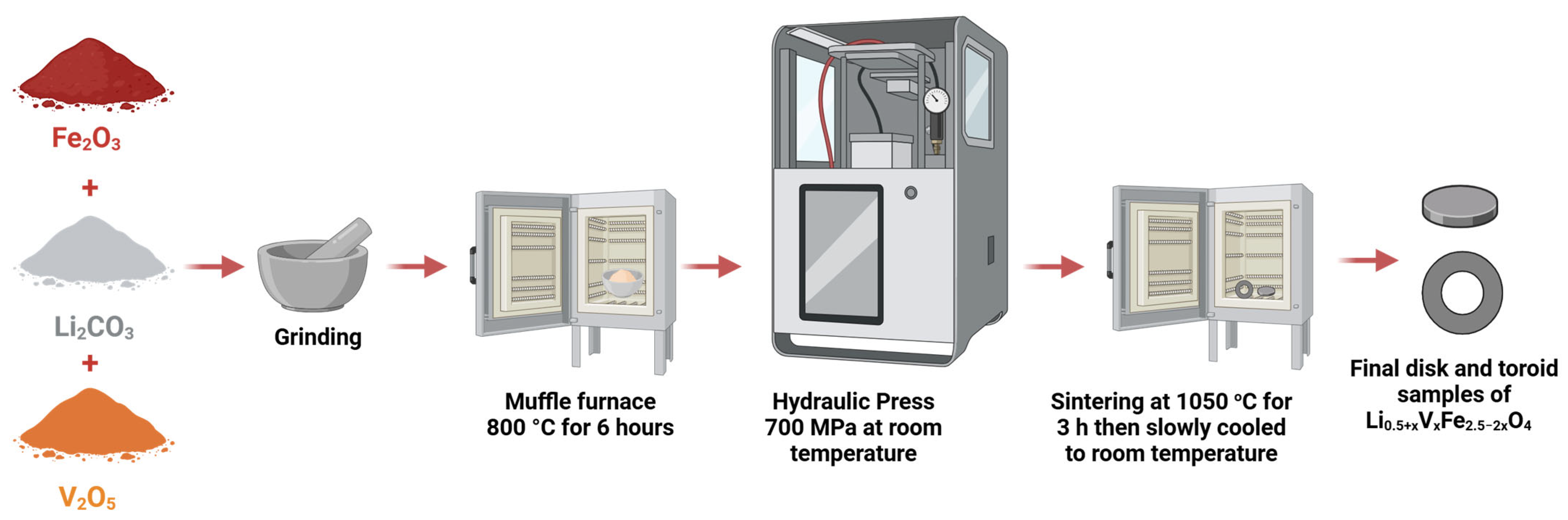

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Samples

2.2. Measurements and Calculations

3. Results

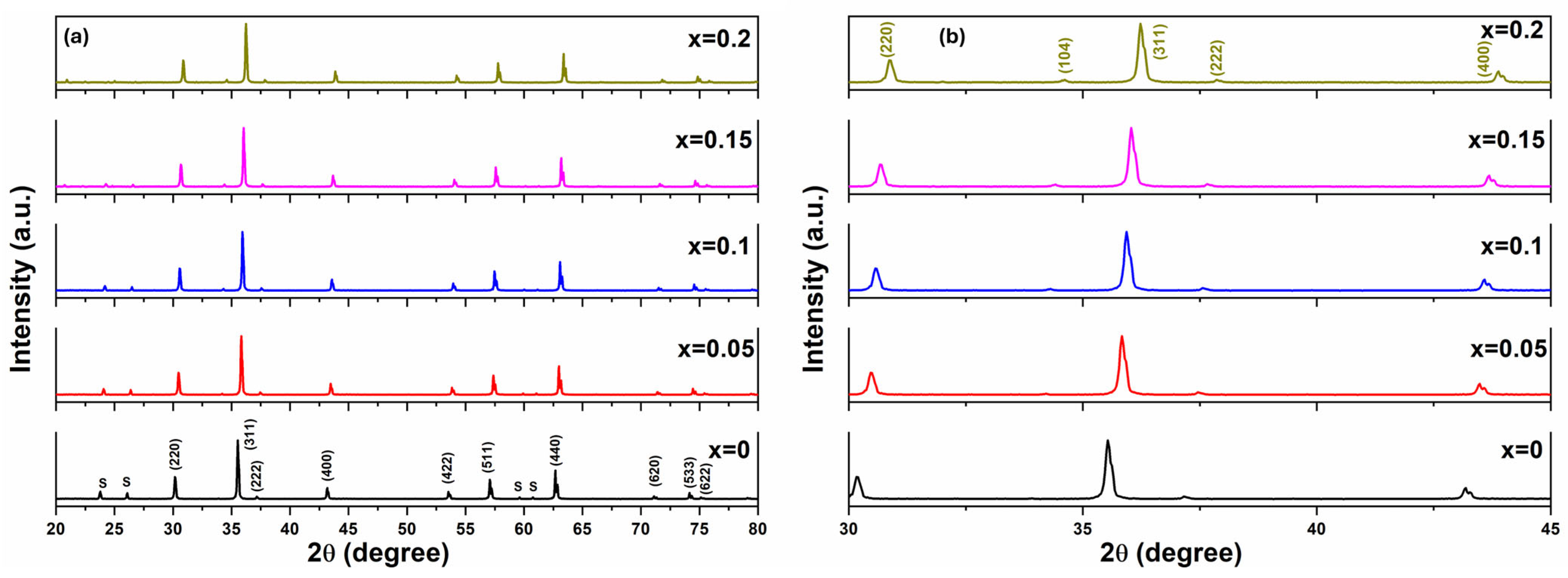

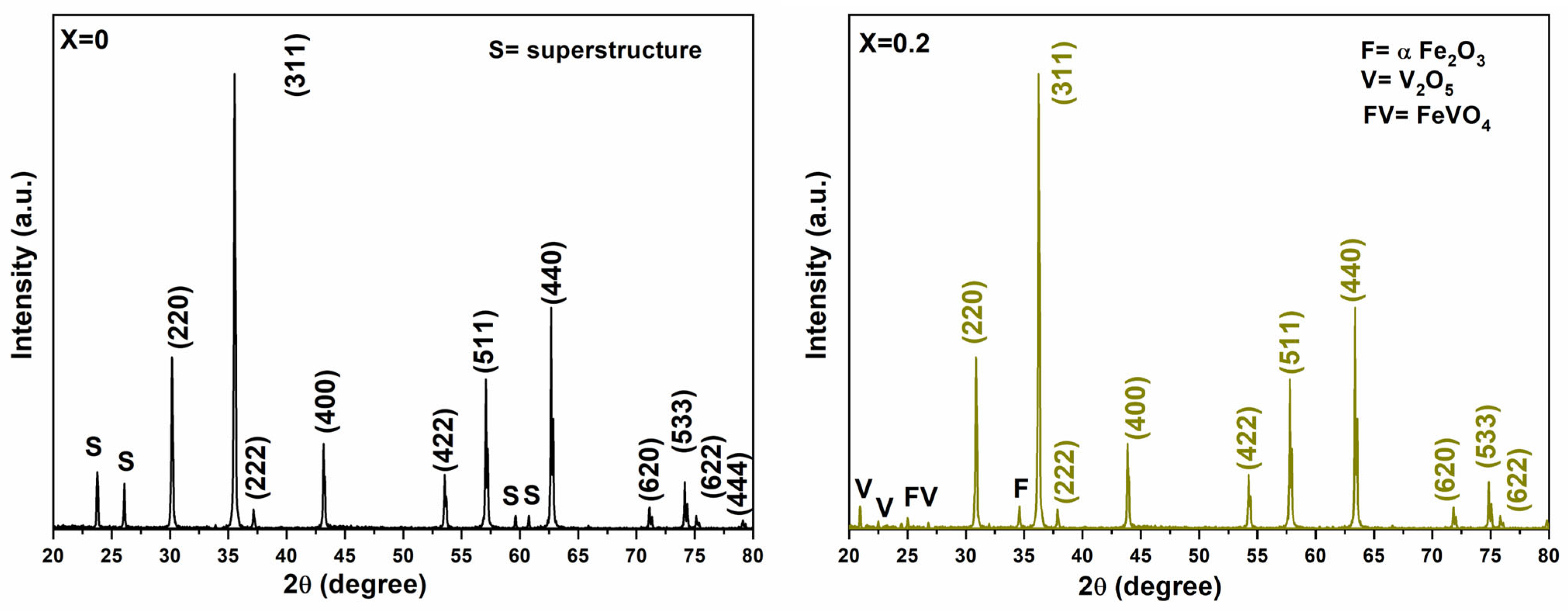

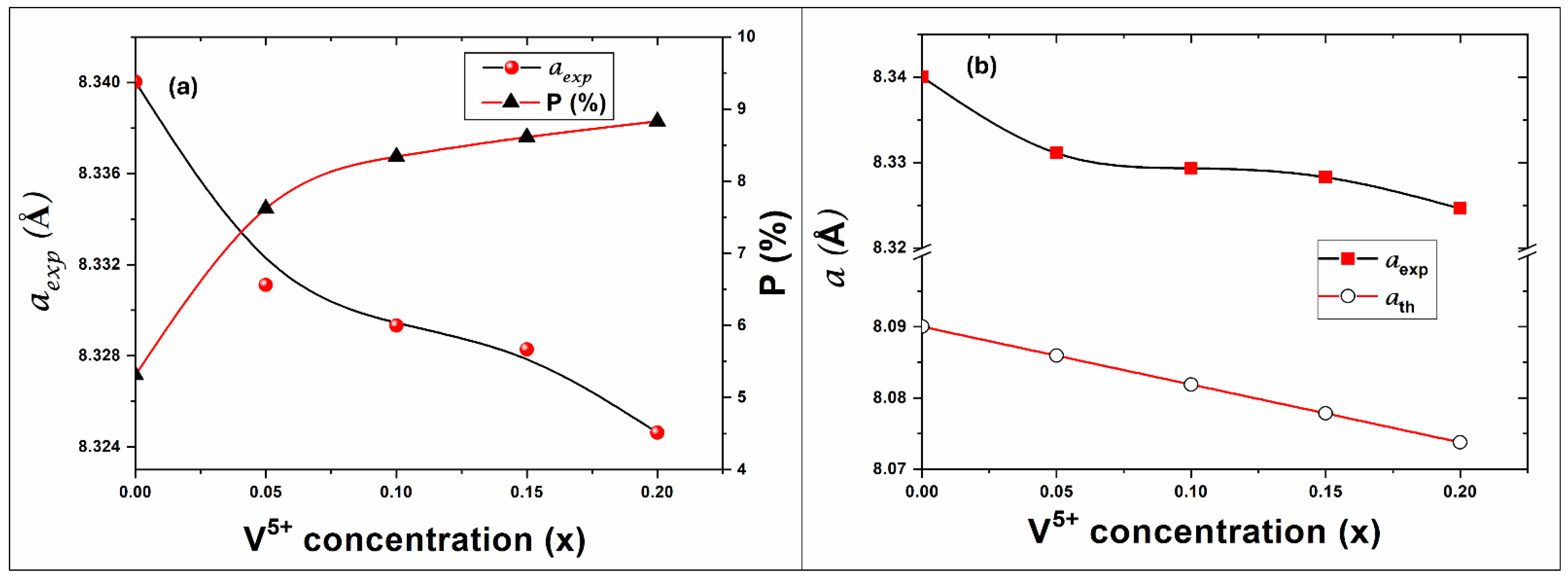

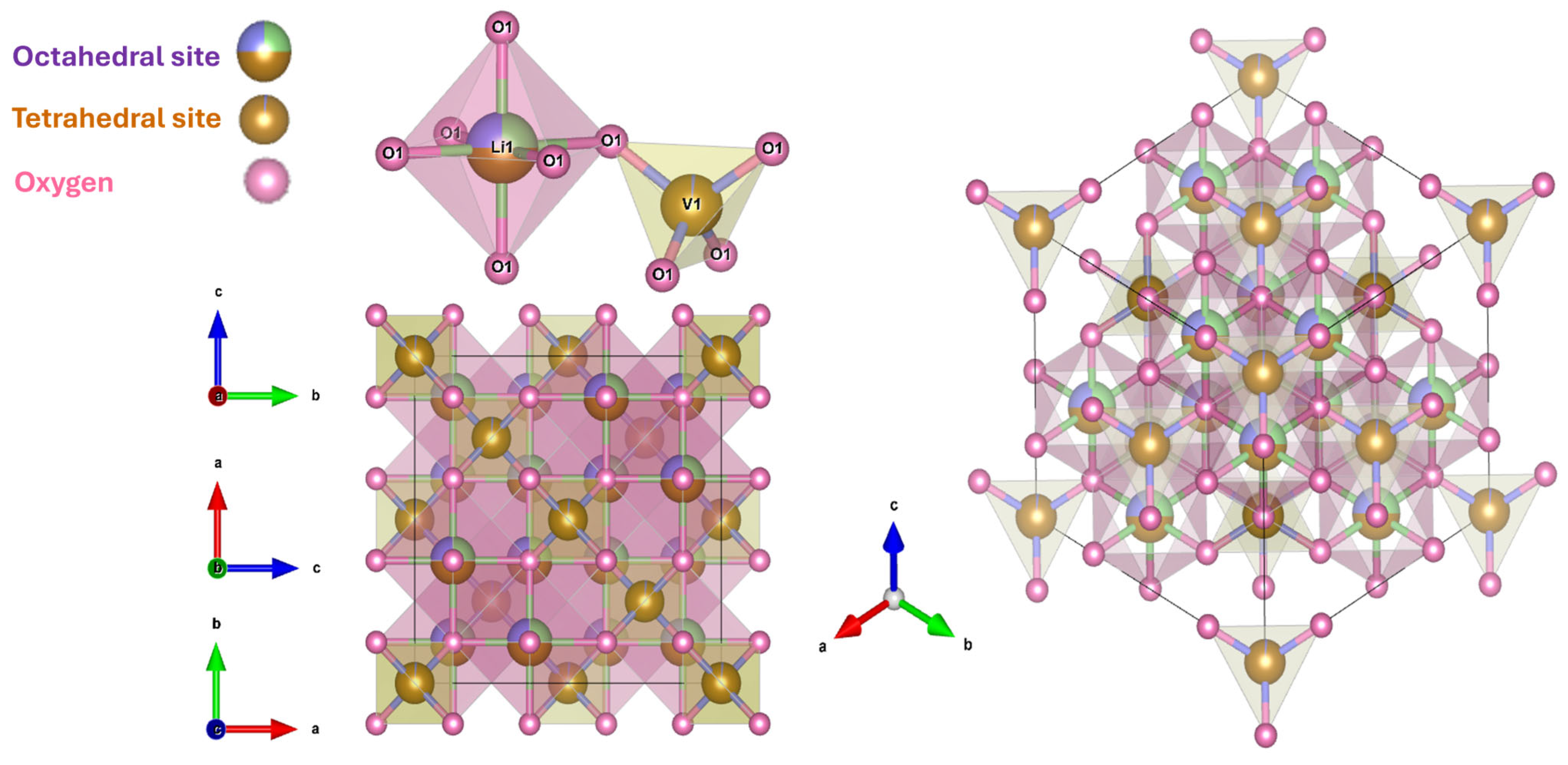

3.1. Structure and Physical Properties

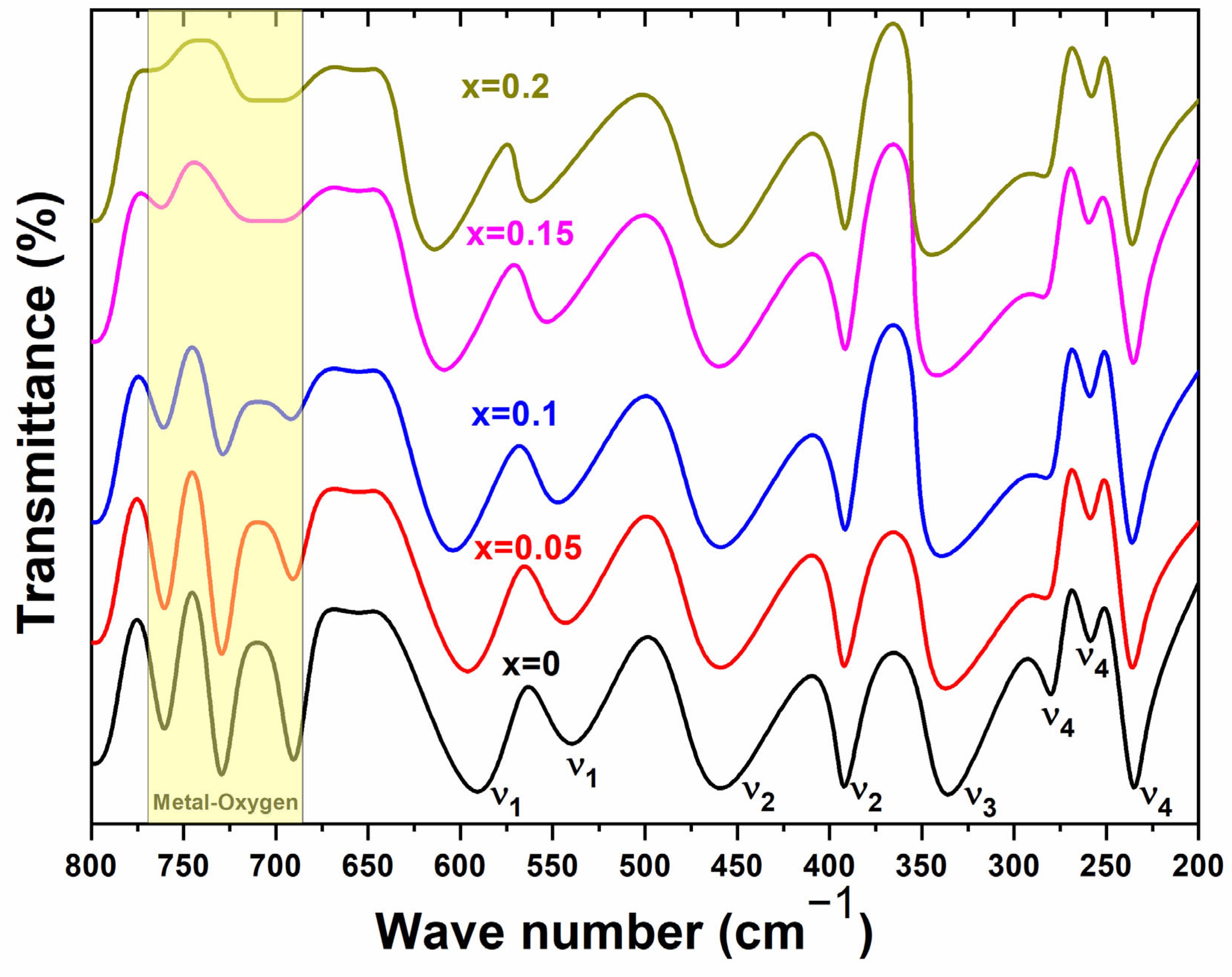

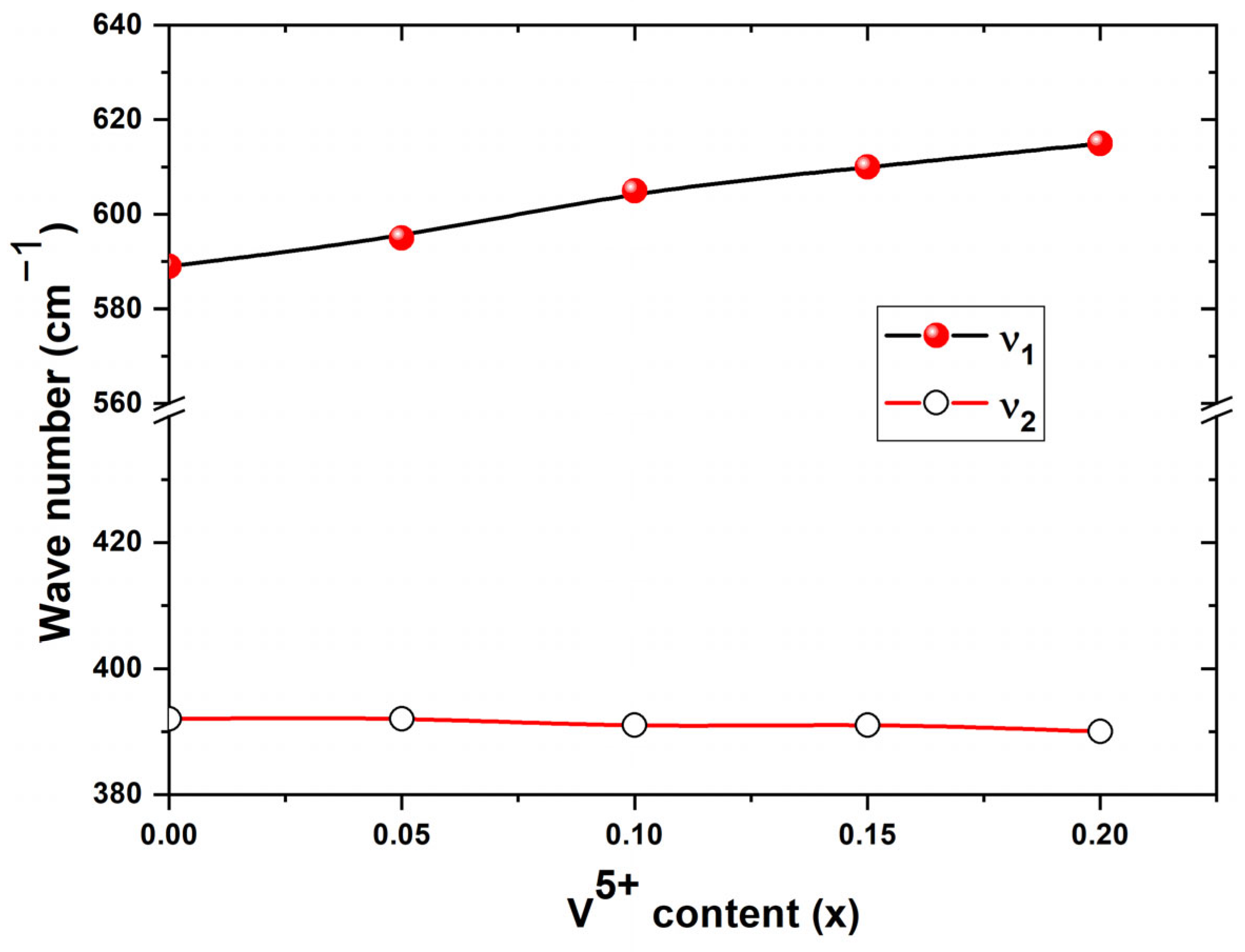

3.2. Infrared Spectroscopic Analysis

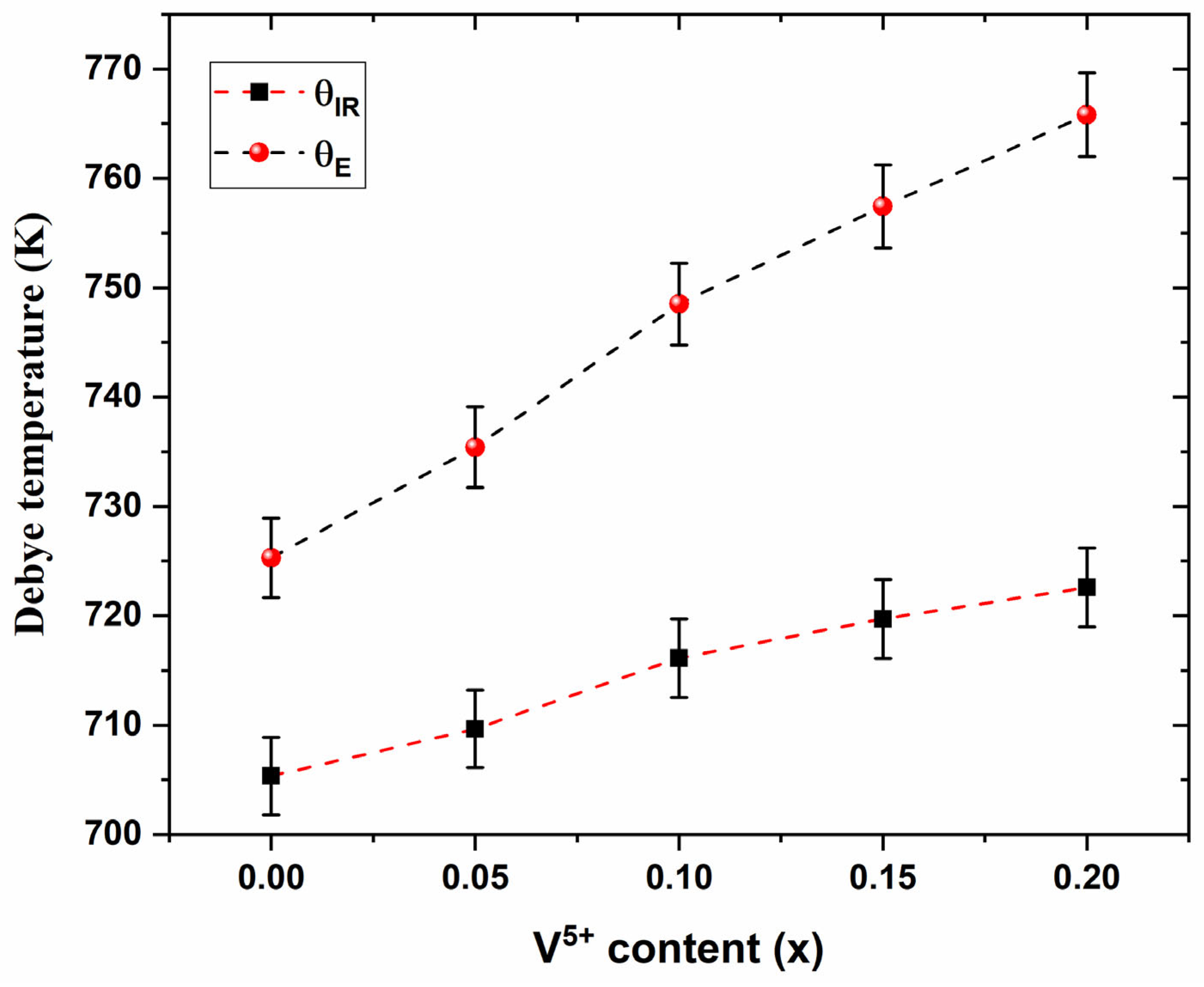

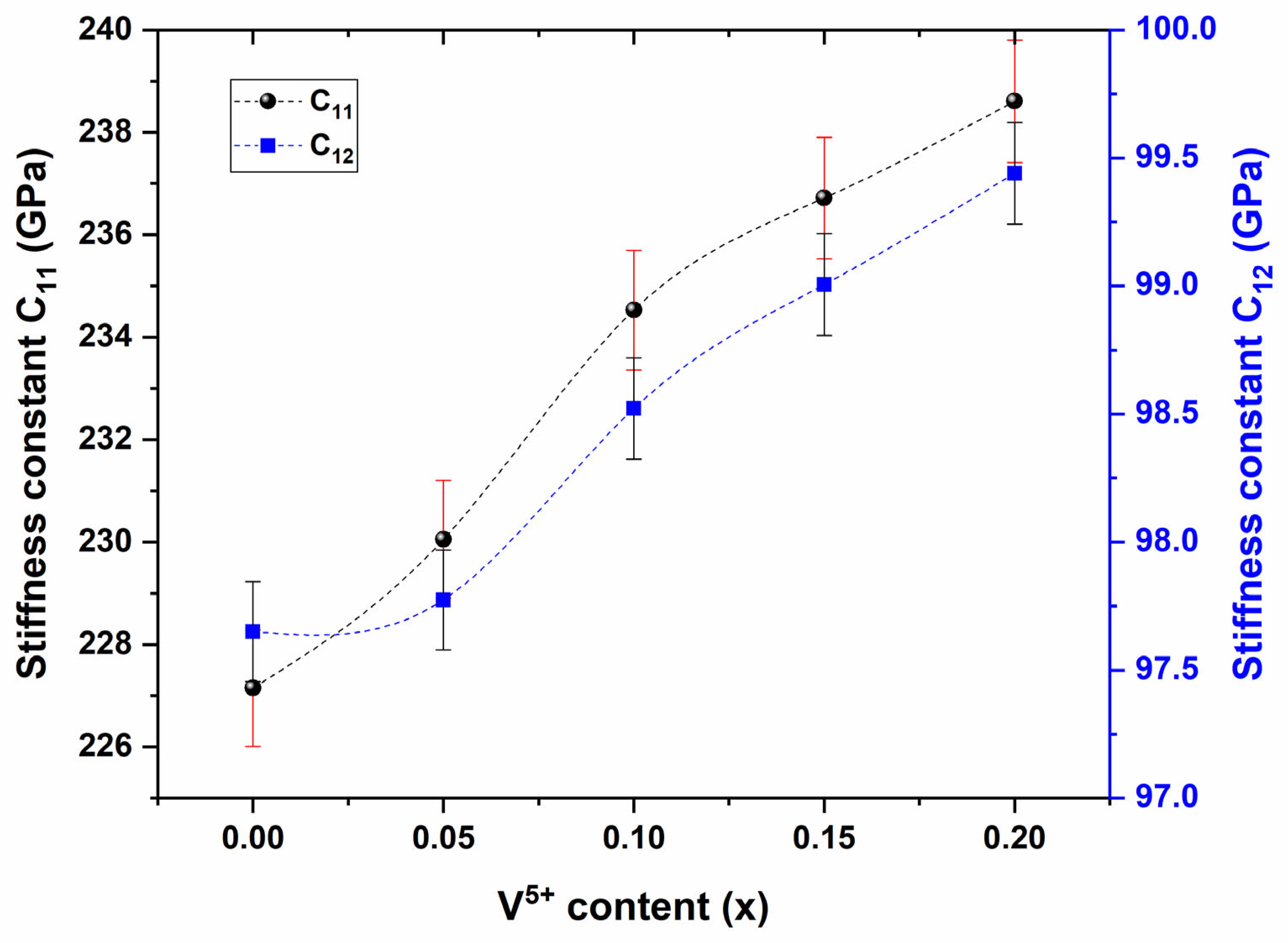

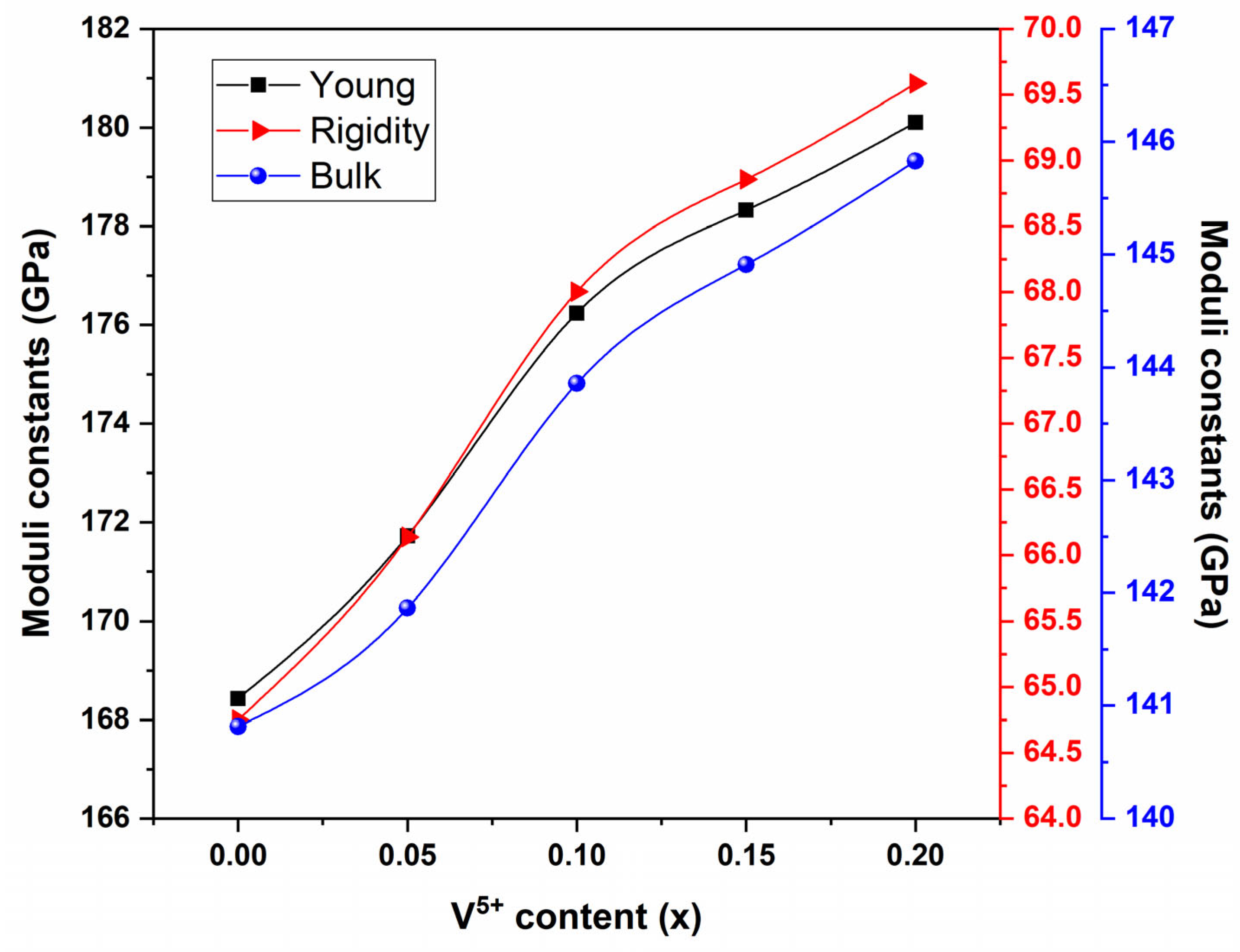

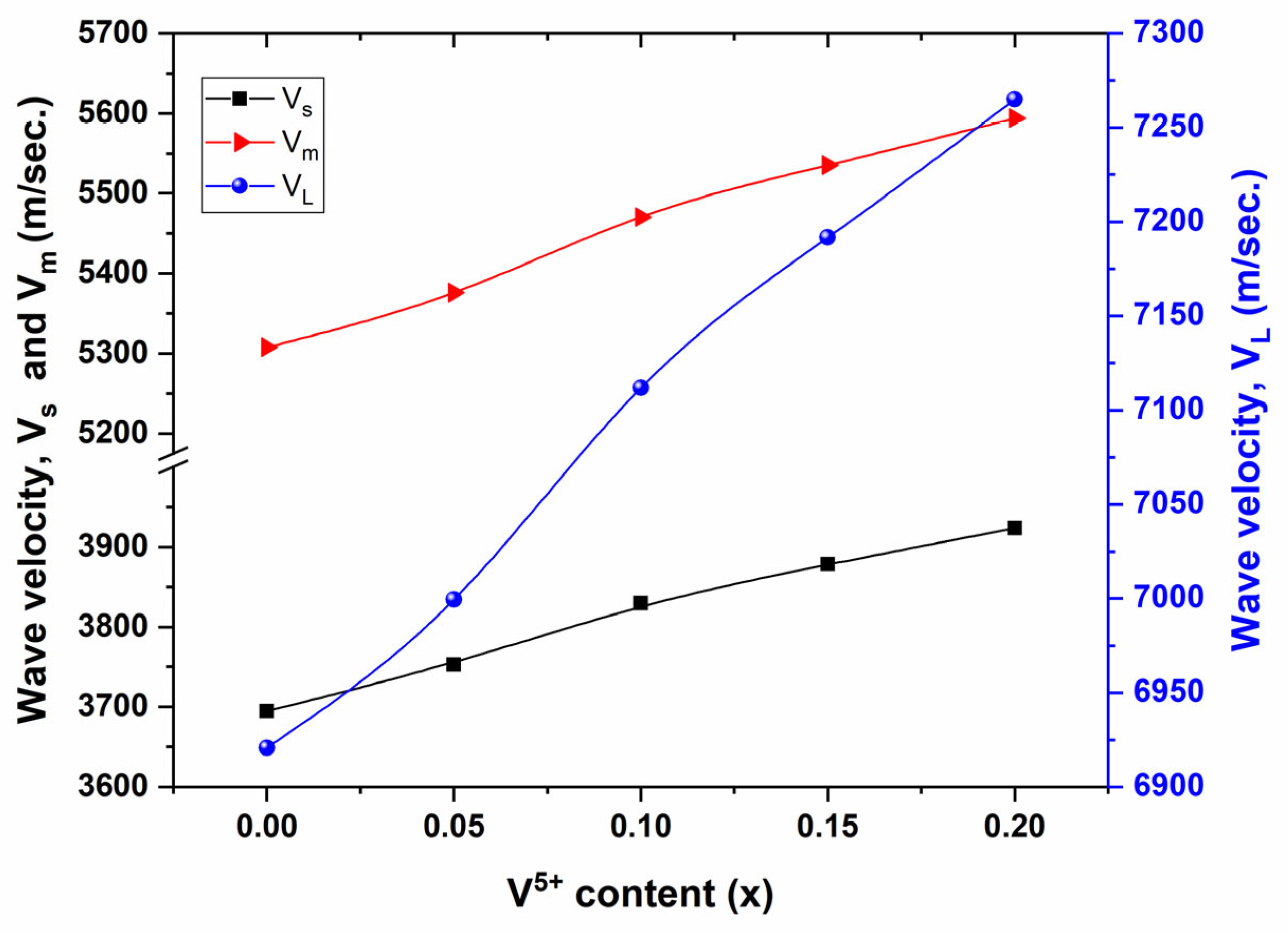

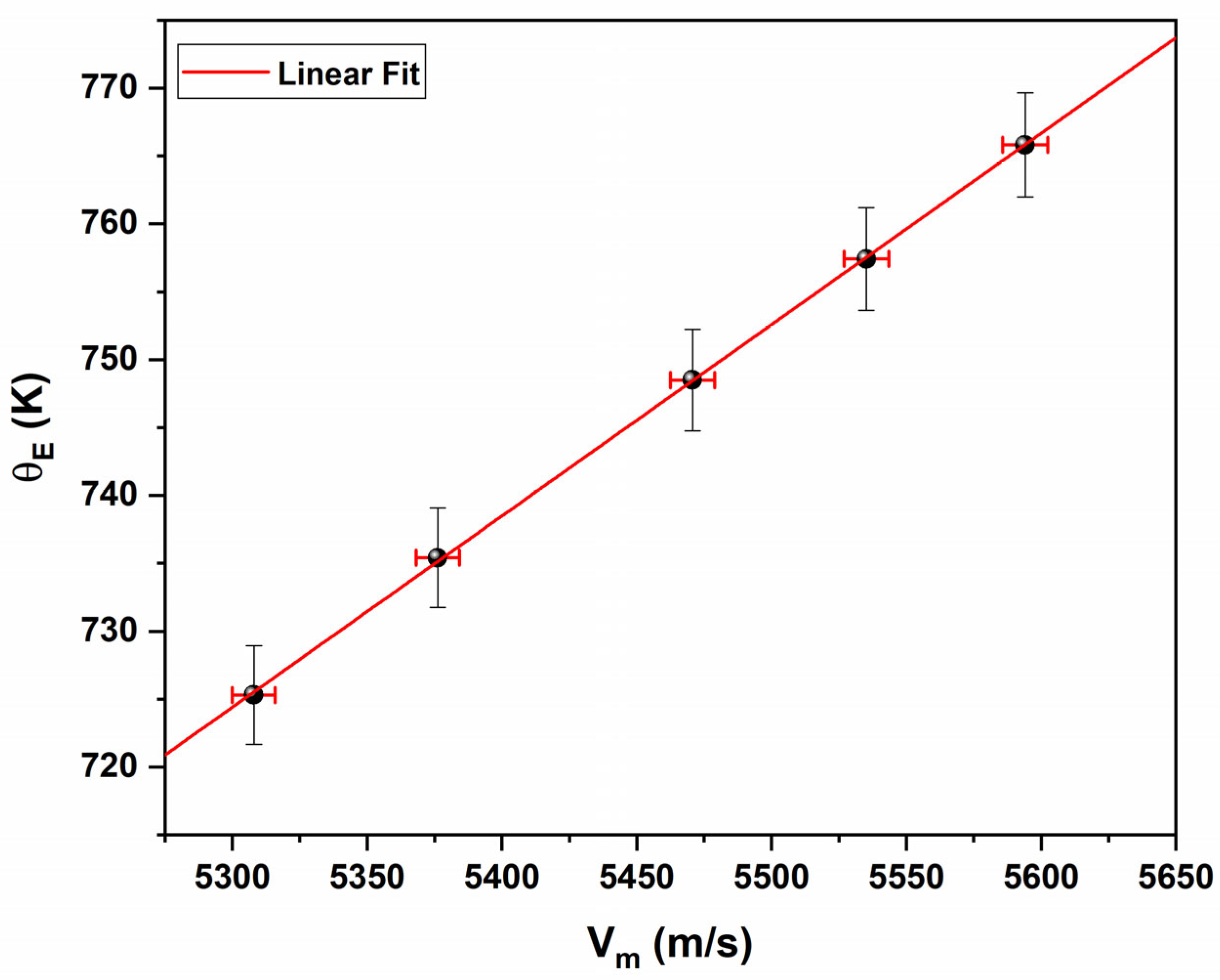

3.3. Elastic Properties

3.4. Magnetization

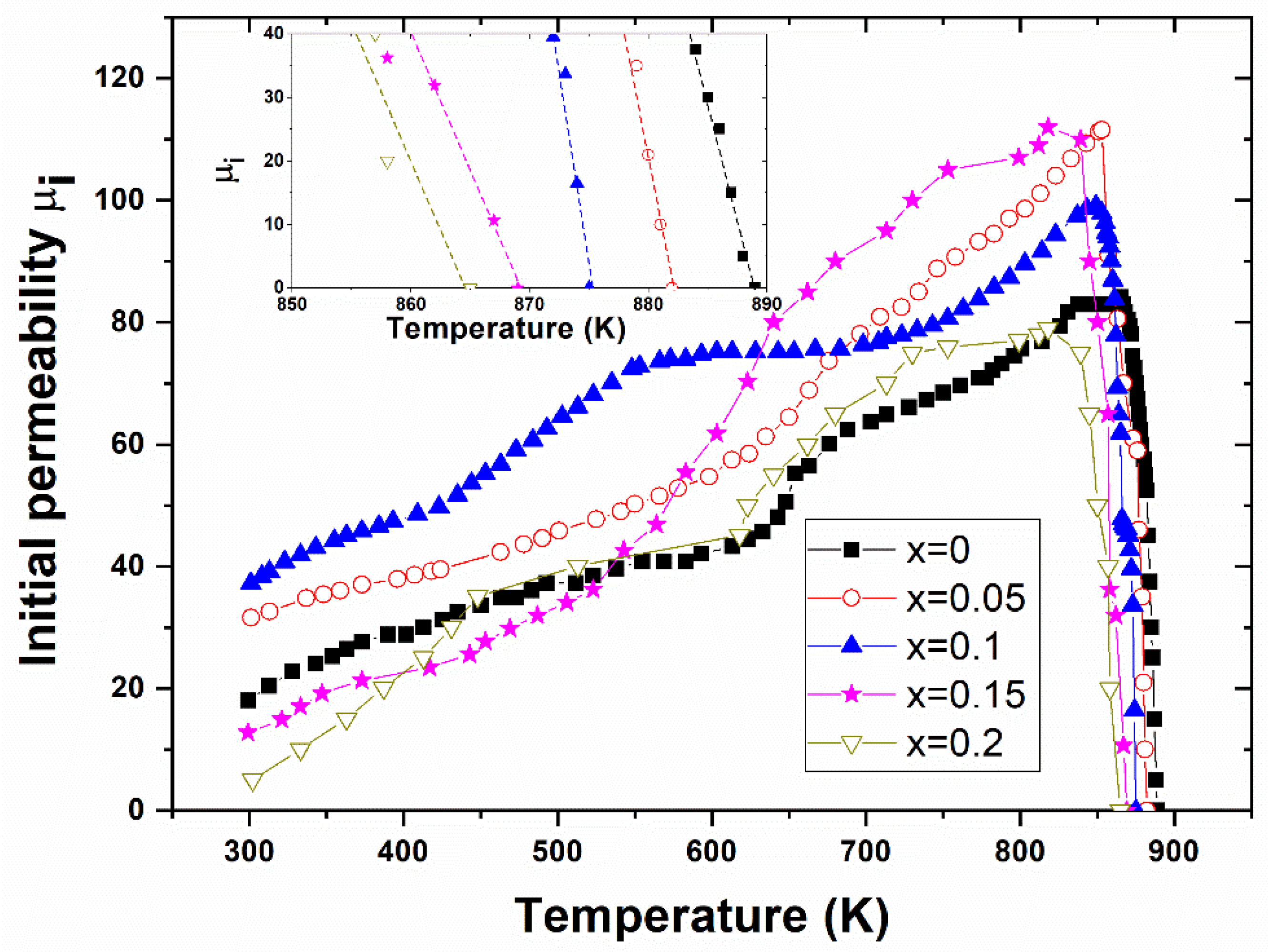

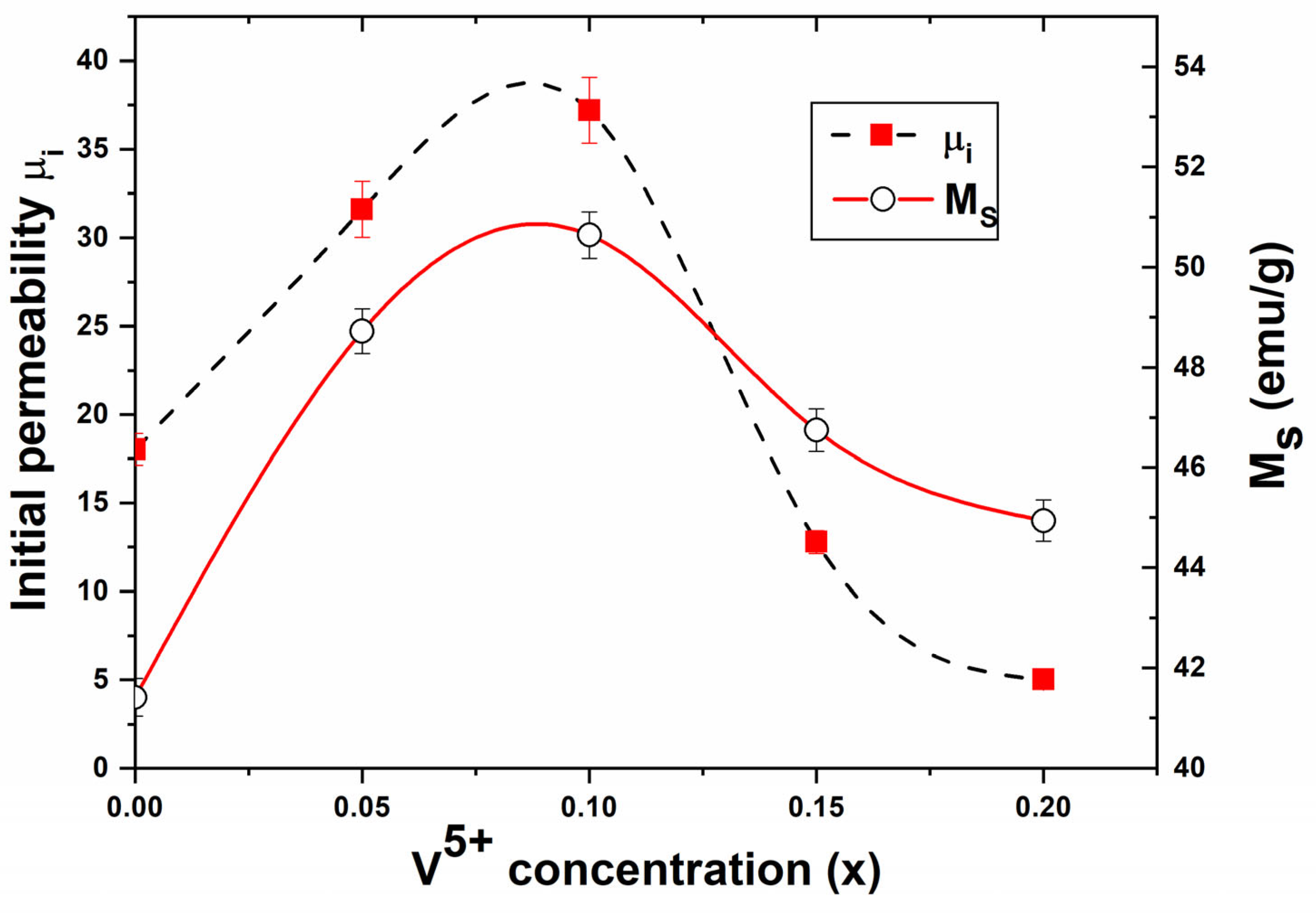

3.4.1. Initial Permeability

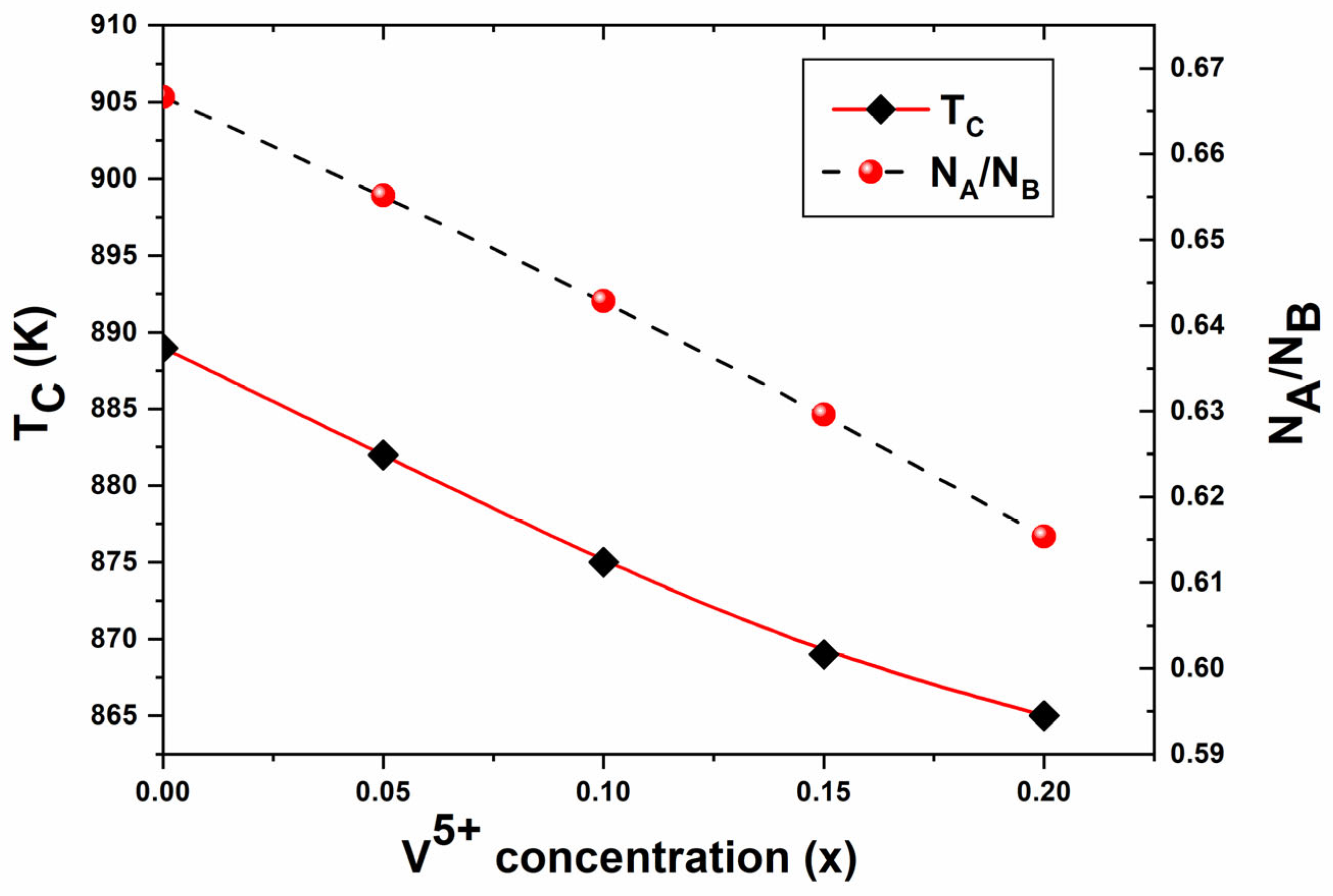

3.4.2. Curie Temperature (TC)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sahu, M.K.; Mallick, P.; Satpathy, S.K.; Behera, B. Structural, Dielectric, and Electrical Study of Bismuth Ferrite-Lithium Vanadate. Eur. Phys. J. Appl. Phys. 2022, 97, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-naggar, A.M.; Mohamed, M.B.; Aldhafiri, A.M.; Heiba, Z.K. Effect of Vacancies and Vanadium Doping on the Structural and Magnetic Properties of Nano LiFe2.5O4. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 16435–16444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zonkol, M.G.; Faramawy, A.M.; Allam, N.K.; El-Sayed, H.M. Improvement of the Magnetization and Heating Ability of CoFe2O4 /NiFe2O4 Core/Shell Nanostructures. Phys. Scr. 2024, 99, 125970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malathi, S.; Sridhar, B.; Wayessa, S.G. A Study of Lithium Ferrite and Vanadium-Doped Lithium Ferrite Nanoparticles Based on the Structural, Optical, and Magnetic Properties. J. Nanomater. 2023, 2023, 6752950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikmanesh, H.; Eshraghi, M.; Karimi, S. Cation Distribution, Magnetic and Structural Properties of CoCrxFe2−XO4: Effect of Calcination Temperature and Chromium Substitution. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2019, 471, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Tian, Z.; Yu, X.; Yu, D.; Ren, L.; Fu, Y. Influence of Thermal Annealing on the Morphology and Magnetic Domain Structure of Co Thin Films. Mater. Res. Express 2021, 8, 056103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianciola, B.N.; Lima, E.; Troiani, H.E.; Nagamine, L.C.C.M.; Cohen, R.; Zysler, R.D. Size and Surface Effects in the Magnetic Order of CoFe2O4 Nanoparticles. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2015, 377, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazen, S.A.; Abu-Elsaad, N.I.; Nawara, A.S. Studies on Micro-Structure and Dc Conductivity of Polycrystalline Li0.5+0.5xSixFe2.5−1.5xO4 Spinel Ferrites. Powder Technol. 2017, 317, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Gómez, P.; Muñoz, J.M.; Valente, M.A.; Graça, M.P.F. Broadband Ferromagnetic Resonance in Mn-Doped Li Ferrite Nanoparticles. Mater. Res. Bull. 2019, 112, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.N.; Huy, T.Q.; Le, A.T. Spinel Ferrite (AFe2O4)-Based Heterostructured Designs for Lithium-Ion Battery, Environmental Monitoring, and Biomedical Applications. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 31622–31661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aepurwar, D.N.; Shirsath, S.E.; Mujasam, K.; Hadi, M.; Devmunde, B.H. Effect of Li1+ Ion on the Physico-Chemical Properties Cation Distribution of Sol-Gel Synthesized Ni-Zn Spinel Ferrite Nanoparticles. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 55658–55668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aepurwar, D.N.; Prasad, V.J.S.N.; Devmunde, B.H. Effect of Cd2+ Substitution on the Structural, Magnetic, and Dielectric Properties of Li-Ni Spinel Ferrite Nanoparticles Synthesized via Sol-Gel Method. Phys. Open 2025, 23, 100273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarale, J.R.; Pedanekar, R.S.; Patil, A.R.; Ganbavle, V.V.; Parale, V.G.; Rajpure, K.Y.; Kulkarni, S.N. Enhancing Dye Degradation with Li–Ni Ferrite: A Sol-Gel Auto-Combustion Synthesis Strategy with Temperature Tunable Properties. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2025, 338, 130628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazen, S.A.; Abdallah, M.H.; Nakhla, R.I.; Zaki, H.M.; Metawe, F. X-Ray Analysis and IR Absorption Spectra of Li-Ge Ferrite. Mater. Chem. Phys. 1993, 34, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, K.P.; Kwon, W.H.; Lee, J.-G.; Lee, S.W. Crystallographic and Magnetic Properties of Vanadium-Substituted Li-Co-Ti Ferrite. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 2010, 56, 1838–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisnam, M.; Phanjoubam, S.; Sarma, H.N.K.; Thakur, O.P.; Devi, L.R.; Prakash, C. Dielectric Properties of Vanadium Substituted Lithium Zinc Titanium Ferrites. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 2003, 17, 3881–3887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisnam, M.; Phanjoubam, S.; Sarma, H.N.K.; Prakash, C.; Devi, L.R.; Thakur, O.P. Magnetic Properties of Vanadium-Substituted Lithium Zinc Titanium Ferrite. Mater. Lett. 2004, 58, 2412–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samy, A.M. Magnetic and Electrical Studies of V, Cd and Gd Ions Substituted Li-Ferrite. J. Mater. Sci. Eng. Adv. Technol. 2011, 4, 133–147. [Google Scholar]

- IIMURA, T. Effect of V2O5 Additions on the Ordering of Li-Zn Ferrite. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1976, 59, 539–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faramawy, A.M.; Elsayed, H.; Agami, W.R. Correlation between Structure, Cation Distribution, Elastic, and Magnetic Properties for Bi3+ Substituted Mn-Zn Ferrite Nanoparticles. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 314, 128939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, M.K.; Raju, M.R.; Babu, K.R. Structural Observations, Density and Porosity Studies of Cu Substituted Ni-Zn Ferrite through Standard Ceramic Technique. Chem. Sci. Trans. 2015, 4, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- El-Sayed, H.M.; Agami, W.R. Improvement of the Magnetic Properties of Li–Zn Ferrite by Bi3+ Substitution. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2016, 27, 4866–4870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.C.; Zhong, X.C.; Long, K.W.; Liu, Z.W.; Ramanujan, R.V. Effective Reduction of Sintering Temperature for High-Performance Mn-Zn Ferrites via Synergistic Doping of V2O5 and Al2O3 Sintering Aids. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 41430–41444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranu, R.; Kadam, S.L.; Gade, V.K.; Desarada, S.V.; Yewale, M.A. Comparative Microstructural Analysis of V2 O5 Nanoparticles via X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Technique. Nanotechnology 2024, 35, 435701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faramawy, A.M.; Mattei, G.; Scian, C.; Elsayed, H.; Ismail, M.I.M. Cr3+ Substituted Aluminum Cobalt Ferrite Nanoparticles: Influence of Cation Distribution on Structural and Magnetic Properties. Phys. Scr. 2021, 96, 125849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faramawy, A.M.; Elsayed, H.; Sabry, M.; El-Sayed, H.M. The Effect of Opto-Electronic Transition Type on the Electric Resistivity of Cr-Doped Co3O4 Thin Films. Coatings 2023, 13, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravinder, D. Far-Infrared Spectral Studies of Mixed Lithium-Zinc Ferrites. Mater. Lett. 1999, 40, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, H.M.; Samy, A.M.; Sattar, A.A. Infra-Red and Magnetic Studies of Nb-Doped Li-Ferrites. Phys. Status Solidi 2004, 201, 2105–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazen, S.A.; Abu-Elsaad, N.I. IR Spectra, Elastic and Dielectric Properties of Li–Mn Ferrite. ISRN Condens. Matter Phys. 2012, 2012, 907257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agami, W.R.; Ashmawy, M.A. Structural, Physical, and Magnetic Properties of Nanocrystalline Manganese-Substituted Lithium Ferrite Synthesized by Sol–Gel Autocombustion Technique. Appl. Phys. A 2020, 126, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Zhao, F.; Miao, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, H.; Han, Y.; Tian, M.; Gu, H.; Ma, R. Magnetic Properties and Microstructures of a Ni-Zn Ferrite Ceramics Co-Doped with V2O5 and MnCO3. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 10028–10034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patange, S.M.; Shirsath, S.E.; Jadhav, S.P.; Hogade, V.S.; Kamble, S.R.; Jadhav, K.M. Elastic Properties of Nanocrystalline Aluminum Substituted Nickel Ferrites Prepared by Co-Precipitation Method. J. Mol. Struct. 2013, 1038, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faramawy, A.M. Role of Rare Earth Doping on Structural, Elastic, Optical, and Magnetic Properties of Co-Cu Spinel Ferrite Nanoparticles Prepared by Sol Gel Auto-Combustion (SGAC) Route. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2025, 712, 417331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, R.A.; Patange, S.M.; Tamboli, Q.Y.; Ramanathan, V.; Shirsath, S.E. Spectroscopic, Elastic and Dielectric Properties of Ho3+ Substituted Co-Zn Ferrites Synthesized by Sol-Gel Method. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 16096–16102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nessem, R.G.; Sattar, A.A.; EL-Sayed, H.M.; Faramawy, A.M. Controlling Elastic, Magnetic and Optical Properties of Mn0.7Zn0.3Fe2O4/CdxZn1−XFe2O4; x = (0–0.5) Core/Shell Nanostructures via Lattice Matching. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2025, 346, 131323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, K.B.; Chhantbar, M.C.; Joshi, H.H. Study of Elastic Behaviour of Magnesium Ferri Aluminates. Ceram. Int. 2006, 32, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, K.B. Elastic Moduli Determination through IR Spectroscopy for Zinc Substituted Copper Ferri Chromates. J. Mater. Sci. 2004, 39, 2887–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravinder, D.; Balachander, L.; Venudhar, Y.C. Elastic Behaviour of Manganese Substituted Lithium Ferrites. Mater. Lett. 2001, 49, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agami, W.R.; Ashmawy, M.A.; Sattar, A.A. Structural, IR, and Magnetic Studies of Annealed Li-Ferrite Nanoparticles. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2014, 23, 604–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askarzadeh, N.; Shokrollahi, H. Results in Chemistry A Review on Synthesis, Characterization and Properties of Lithium Ferrites. Results Chem. 2024, 10, 101679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanks, K.; Senthilarasu, S.; Mallick, T.K. Optics for concentrating photovoltaics: Trends, limits and opportunities for materials and design. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 60, 394–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, B.P.; Caltun, O.; Dumitru, I.; Spinu, L. Complex Permeability Spectra of Ni–Zn Ferrites Doped with V2O5/Nb2O5. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2006, 304, e749–e751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Joy, P.A. Magnetic Properties of Superparamagnetic Lithium Ferrite Nanoparticles. J. Appl. Phys. 2005, 98, 124312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Lattice Parameters (Å) [±0.002] | Porosity [±0.01] | X-Ray Density (g cm−3) [±0.001] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | P(%) | |||

| 0 | 8.340 | 8.090 | 5.31 | 4.742 |

| 0.05 | 8.331 | 8.086 | 7.62 | 4.695 |

| 0.1 | 8.329 | 8.082 | 8.34 | 4.637 |

| 0.15 | 8.328 | 8.078 | 8.61 | 4.577 |

| 0.2 | 8.325 | 8.074 | 8.83 | 4.521 |

| Tetrahedral Bands | Octahedral Bands | Lattice Vibration | F × 105 | σ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | ν1 | ν2 | ν3 | ν4 | Ft | Fo | |

| 0 | 589–540 | 460–392 | 335 | 235–259–281 | 2.56 | 1.23 | 0.3006 |

| 0.05 | 595–543 | 460–392 | 340 | 236–259–281 | 2.61 | 1.22 | 0.2982 |

| 0.1 | 605–548 | 460–391 | 346 | 236–259–280 | 2.69 | 1.22 | 0.2955 |

| 0.15 | 610–554 | 460–391 | 349 | 235–260–282 | 2.73 | 1.20 | 0.2949 |

| 0.2 | 615–562 | 460–390 | 352 | 236–259–279 | 2.78 | 1.19 | 0.2941 |

| x | Ms (emu/g) [±0.1] | Hc (G) [±0.05] | Br (emu/g) [±0.1] | M (g) [±0.1] | Ms (μB) [exp.] | Mag. Mom. (μB) [calc.] | ΘYK (°) | Initial Permeability ) | Tc (K) [±2] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 41.42 | 211.36 | 8.9 | 207.08 | 1.54 | 2.5 | 29.31 | 18.02 | 889 |

| 0.05 | 48.72 | 156.54 | 12 | 204.39 | 1.78 | 2.5 | 25.75 | 31.61 | 882 |

| 0.1 | 50.64 | 132.68 | 13 | 201.70 | 1.83 | 2.5 | 25.27 | 37.21 | 875 |

| 0.15 | 46.75 | 145.69 | 13 | 199.01 | 1.67 | 2.5 | 28.71 | 12.79 | 869 |

| 0.2 | 44.94 | 163.51 | 13 | 196.32 | 1.58 | 2.5 | 30.86 | 5.01 | 865 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Agami, W.R.; Elsayed, H.M.; Faramawy, A.M. Improvement of Structural, Elastic, and Magnetic Properties of Vanadium-Doped Lithium Ferrite. Compounds 2025, 5, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/compounds5040054

Agami WR, Elsayed HM, Faramawy AM. Improvement of Structural, Elastic, and Magnetic Properties of Vanadium-Doped Lithium Ferrite. Compounds. 2025; 5(4):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/compounds5040054

Chicago/Turabian StyleAgami, W. R., H. M. Elsayed, and A. M. Faramawy. 2025. "Improvement of Structural, Elastic, and Magnetic Properties of Vanadium-Doped Lithium Ferrite" Compounds 5, no. 4: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/compounds5040054

APA StyleAgami, W. R., Elsayed, H. M., & Faramawy, A. M. (2025). Improvement of Structural, Elastic, and Magnetic Properties of Vanadium-Doped Lithium Ferrite. Compounds, 5(4), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/compounds5040054