Abstract

Background: The positive identification of a source of tissue as human plays an important role in various contexts. It is particularly important for investigations concerning tissue and organ trafficking, since unequivocal confirmation is required for legal proceedings involving such cases. While deoxyribonucleic (DNA) methods are considered the gold standard for tissue identification, issues such as degraded DNA or the presence of chemical preservatives can hinder performance and positive identification using DNA techniques. Objectives: The aim of this study was to develop a simple method for presumptive identification of human tissue using standard bottom-up proteomics data. Methods: We identified proteins isolated from human kidney, lung and spleen tissues by bottom-up proteomics and database search using Proteome Discoverer and Sequest HT algorithms. The list of identified proteins was sorted based on liquid chromatography (LC)–mass spectrometry (MS) data metrics such as the number of unique peptides used to identify each protein and the % sequence coverage of an identified protein to determine if any parameter would cluster proteins annotated as human in a distinct category. We found that eliminating proteins identified with fewer than two unique peptides and those with less than 5% sequence coverage resulted in a final list where at least half of the remaining proteins are annotated as human. We applied this data filtration process to blinded LC–MS/MS data from 26 previous experiments to assess accuracy. Results: Using bottom-up proteomics data and the filtration rules established, we identified tissue samples (n = 10), including kidney, spleen, lung, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded uterus, frozen breast tissue, dry blood and dry saliva as human, and tissue (n = 16) from rat, mouse, bovine, and sheep as non-human, resulting in 100% sensitivity and specificity. Conclusions: The results demonstrate that the list of identified proteins following a standard bottom-up proteomics experiment could be filtered and potentially used as a fast and simple method for presumptive human tissue identification.

1. Introduction

The acts of acquiring, stealing and trading in human organs and body parts are common practices in many parts of the world [1]. This activity, which is largely illegal, is driven by the worldwide need for organs and tissue for transplant, biomedical research and fetishism [1]. Human tissues that are legally available can only satisfy about 10% of the global demand [1,2], thus, many are procured illegally, and this makes illegal trafficking one of the most surreptitious forms of human trafficking in the world [1,3].

One of the first steps to determine whether a crime has been committed is to prove that the source of a questioned tissue or organ linked to a suspect is human or prohibited [3]. This will be prerequisite in most jurisdictions to formally charge the suspect and launch a full-scale investigation to confirm and individualize the source. It is essential to promptly establish clear evidence that a crime has occurred, as many jurisdictions impose strict time limits on how long a suspect may be detained without formal charges. While short tandem repeat (STR) DNA analysis is widely accepted as the gold standard for identification of human and animal tissue, because it utilizes an approach that is scientifically and statistically valid [4], STR DNA analysis may not be feasible if (a) appropriate primers for the species are not available for the amplification step by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), (b) the extracted DNA is insufficient or significantly degraded, or (c) a DNA laboratory is not available. DNA is prone to damage, and environmental, chemical, and biological factors could render DNA isolated from a sample unsuitable for production of usable genotype information by nuclear DNA, mitochondria DNA or single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis [4]. Currently, if common DNA analysis methods or next-generation sequencing (NGS) are not possible, there are very few simple alternatives available to rapidly determine the origin of a tissue sample that has been cut into unrecognizable pieces or treated with chemicals that prevent DNA analysis [4].

Proteomics, an approach that does not rely on DNA, involves the large-scale analysis of proteins with the specific goal of identifying, characterizing and quantifying proteins in a biological sample [5]. It is extensively used in many applications, including cancer and other complex disease research [5,6]. Proteomics relies on several technologies and techniques, which include liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (aka LC–MS/MS), statistics and bioinformatics [5]. Rapid advances in this field have enabled quick analysis of peptides and proteins from various types of biological samples, like what is achieved in NGS [6]. This large-scale protein analysis technique, which provides information at the global level [5,7], is generating significant interest in forensic science [6] because (a) it is a quantifiable and statistically valid method of biological sample analysis that can produce genetic information and (b) has the potential to provide forensic biologists with answers to questions that DNA alone cannot answer, such as differentiating cells recovered from different parts of the body, which has been impossible or difficult to elucidate using DNA information [6]. Specifically, proteomics has been investigated as a quantifiable method for human identification using the hair shaft proteome as a tool to study fingermark (latent fingerprints) aging in forensics [7] and a method for discovery of biomarkers for forensic postmortem interval (PMI) estimation [8,9]. It is also being investigated as a tool that can be used to identify tissue and organ types, a feat that is not possible by STR DNA analysis [9]. It is specifically considered advantageous compared to DNA methods in biological trace analysis due to the abundance and stability of proteins when compared to DNA [10]. The dominating component of forensic evidence is generally protein, and it is the matrix that contains other forensically relevant biological molecules [11].

Considering that proteins are more diverse and structurally complex compared to DNA, it is unlikely that all proteins in a tissue sample will be damaged by the same chemicals, handling and environmental conditions that render DNA unusable [12]. This means that proteomic analysis of biological samples could yield useful information at the molecular level in the absence of a useful DNA template. Bunger et al. [13] report that proteomics can be used in human identification just like DNA because there are single amino acid polymorphisms (SAPs) in proteins that result from non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms (nsSNPs) [13]. Apparently, the genetic variations in the form of SAPs, which can be obtained from detecting genetically variant peptides, are a quantifiable measure that can be used for human identity discrimination [4]. Genetically variant peptides (GVP), that is, peptides that contain SAPs, have been identified by proteomics and used as the basis to infer SNP genetic profiles independent of a DNA template [13,14,15].

Despite accumulating literature that indicates that proteomics can be used to analyze tissue to obtain individualizing genetic information, there is a paucity of literature concerned with the use of proteomics routinely as a method for presumptive tissue identification in forensic science practice. Recently, Alex et al. reported that the substantial potential of proteomics in forensic science remains insufficiently understood, leading to this advanced analytical method being both underexplored and underutilized within the forensic discipline [10].

Experience in our protein forensic laboratory suggested that annotation of the proteins identified by bottom-up proteomics could provide insights into the source of the tissue. Based on the hypothesis that “tissue of human origin will have more proteins annotated as human”, we screened the list of proteins identified in three human samples following “mammalian” and “human” database searches with LC–MS/MS data and empirically established a set of data filtration rules that removed most, if not all, proteins on the list that were annotated as non-human. We applied the criteria to the list of proteins identified in 26 anonymized proteomics datasets and successfully identified all the specimens as either human or non-human.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Source of Samples

All the investigations involving human specimens were conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (1975, revised in 2013). The reference human kidney (RHK), spleen (RHS), lung (RHL), formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded uterus (FFPE1-FFPE3) and optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound-embedded breast tissue samples (OCT1, OCT2) used were collected between 2003 and 2005 under an Institutional Review Board-approved biobanking protocol: the Windber Tissue Repository initiative, at the Windber Research Institute (Protocol #: Pro 00009470), which allowed for their use without personal identifiers in research. Except for the FFPE samples, all samples were frozen at −80 °C or lower until used for this study. The dried blood spot samples (GPB1-GPB3) were collected in 2010 from staff volunteers and stored in GenPlates (GenTegra LLC, Pleasanton, CA, USA) in the dry state at room temperature until used for the study. Informed consent was secured through ITSI Biosciences Research Consent Form No. ITSI-RCF-001. Fresh human blood (DHB1) and saliva (DHS1) samples were obtained from staff volunteers at the time the experiment was conducted, with informed consent secured through ITSI Biosciences Research Consent Form No. ITSI-RCF-001 for their use in research. For this experiment, human blood and saliva from a volunteer were also deposited on a laboratory bench surface and recovered using the dry and wet-swabbing protocol after 24 h.

Non-human LC–MS/MS datasets from bovine (B1, B2), sheep (S1), rat (R1–R6) and mouse (M1–M7) were used for method validation. All the datasets were legacy proteomic datasets derived from tissue samples submitted to our laboratory as part of routine analytical services. Thus, no new animal tissue was collected specifically for this research. The datasets were randomly selected from our internal database and used only in aggregate form. All records were fully anonymized and contained no identifiable information. Since the data came from non-human sources, were anonymized, and could not be connected to specific projects, the internal ethics committee decided that formal ethical approval was not required or relevant for use of the LC–MS/MS data for independent validation of the method developed for human tissue identification based on LC–MS/MS data filtration.

The chemically treated tissue of unknown origin was submitted by an investigating police officer as an evidentiary sample (ES1–ES4) for testing to determine if it was of human origin.

2.2. Proteomics Analysis

All proteomic analyses were performed at ITSI Biosciences, Johnstown, PA, USA using a standard bottom-up proteomics workflow that involves protein isolation, tryptic digestion, tandem mass spectrometry and database search for protein identification [5,16].

2.2.1. Questioned and Known Human Samples

Protein extracts were prepared from the known human (RHK, RHL, RHS) and questioned samples (ES1–ES4) by homogenizing a known weight of each tissue in 1× RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris base, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% NP40, 0.5% Deoxycholate, pH 8.0) [17]. The weights of RHK, RHL, and RHS used were 58.7 mg, 18.2 mg and 220.7 mg, respectively, whereas the weight of the questioned tissues, ES1, ES2, ES3 and ES4 used were 160 mg, 205 mg, 123 mg and 105 mg, respectively. The volume of RIPA buffer used per milligram of tissue was 4.4 mL. Each homogenate was centrifuged at 15,000× g for 10 min, and the supernatant was carefully transferred to a clean tube without disturbing the precipitate. Total protein assay was performed with the ToPA protein assay kit (ITSI Biosciences, Johnstown, PA, USA) as previously described [17].

2.2.2. Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) Tissue

Proteins were isolated from FFPE human uterus samples (FFPE1–FFPE3) using the ToPI-F2 kit and protocol (ITSI Biosciences, Johnstown, PA, USA). Briefly, 5 curls (8–10 mm each) were transferred to microfuge tubes and processed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Protein assay was performed using the ToPA protein assay kit [17]. The isolated proteins were stored at −20 °C until analyzed.

2.2.3. Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT) Compound-Embedded Tissue

Proteins were isolated from OCT-embedded human breast tissue samples (OCT1, OCT2) using the ToPI-DIGE kit and protocol (ITSI Biosciences, Johnstown, PA, USA). Briefly, 2 tubes containing 8–10 shavings were removed from the freezer, and 200 mL of ice-cold ToPI-DIGE lysis buffer was immediately added to each. tube. The tubes were incubated on ice for 45 min. During the incubation, the tubes were vortexed 4 times and sonicated for 10 s twice. After incubation, the tubes were spun at 12,000 rpm in a refrigerated micro centrifuge for 10 min. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and a protein assay was performed using the ToPA protein assay kit [17].

2.2.4. Dried Blood Spots

Proteins were isolated from dried blood spot samples (GPB1–GPB3) collected on one 6 mm FTA paper in a GenPlate (GenTegra LLC, Pleasanton, CA, USA). The paper containing dried blood was punched out of the GenPlate directly into a 2 mL microfuge tube containing 200 mL of PBS. The paper was pulverized with a pipet tip, and the paper and solution were transferred to a spin basket. The spin basket was centrifuged for 30 s at 1200 rpm, and the flow-through collected. Total protein was determined in the flow-through with the ToPA protein assay kit [17].

2.2.5. Saliva and Blood from Countertops

Proteins were isolated from human saliva (DHS1) and human whole blood (DHB1) samples spotted on a countertop and allowed to dry. After 24 h, a sterile cotton swab dipped in sterile proteomics-grade water and a dry swab were used to lift each sample. After lifting, the cotton swab was detached from the holder, placed in a 2 mL microcentrifuge tube containing 100 mL of RIPA buffer, incubated on ice for 30 min, and transferred to a spin basket. The basket with the swab was then placed into a 2 mL tube and spun at 1200 rpm for 30 s. The flow-through was transferred to a new microfuge tube, and protein assay was performed using the ToPA protein assay kit [17].

2.3. Tandem Mass Spectrometry

About 5–10 mg of total protein from each sample was reduced using 5 mM TCEP and alkylated using 55 mM iodoacetamide. The samples were cleaned up using the ToPREP kit to remove interfering substances, resuspended in Triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB) buffer, and trypsin-digested [17]. Digestion was performed with 1.5 mg trypsin (2.5% of the starting protein concentration). The digest was desalted with ZipTip, dried down and resuspended in 2% acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid. LC–MS/MS was performed with a Thermo Surveyor HPLC system fitted with a picofrit C18 nanospray column (New Objective, Woburn, MA, USA). The flow rate was 600 nl/min, and the peptides were eluted from the column using a linear acetonitrile gradient from 2 to 30% acetonitrile over 60 min, followed by high and low organic washes for another 20 min into an LTQ XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) via a nanospray source with the spray voltage set to 1.8 kV and the ion transfer capillary set at 180 °C. A data-dependent Top 5 method was used for data acquisition, where a full MS scan from m/z 400–1500 was followed by MS2 scans on the five most abundant ions [17]. Each ion was subjected to collision-induced dissociation (CID) for fragmentation and peptide identification.

2.4. Database Search

All mass spectrometry raw data files containing “high confidence” peptides were searched using Proteome Discoverer 2.2 (PD2.2) and the Sequest HT search node as previously described [18,19]. During the data filtration process development, we searched both “human” and “mammalian” databases with the same MS/MS data to determine if the number and types of proteins identified would be different. We adjusted the processing workflow to be able to analyze data from low-resolution mass spectrometers such as the Thermo Scientific LTQ-XL as well as high-resolution mass spectrometers such as the Thermo Scientific Q Exactive and Orbitrap Fusion Lumos. Furthermore, we used all the default processing workflow values for the Spectrum Selector Mode in Proteome Discoverer.

The Sequest HT node settings used “human” and “mammalian” databases downloaded from UniProt on 1 November 2024, and the enzyme setting was Trypsin (full). The maximum missed cleavage sites were set to 2 and the minimum and maximum peptide lengths were set to 6 and 150 amino acids, respectively. The mass tolerance settings were 5000 ppm for the precursor and 2 Da for the fragment. The post-translational modification settings used were oxidation of Methionine and Acetylation of the N-Terminus as dynamic modifications, whereas Carbamidomethylation of Cysteine was set as a static modification. All other settings in this node were defaults. Peptides identified with “high confidence” were considered and used for protein identification. All proteins were identified when one or more unique peptides had X-correlation scores greater than 1.5, 2.0, and 2.5 for respective charge states of +1, +2, and +3 [17]. The Percolator algorithm was used for peptide spectral match (PSM) validation using the default settings [20,21]. The strict target False Discovery Rate (FDR) was set as 0.01, and the relaxed target FDR was 0.05. All validations were based on q-values.

2.5. Development of Data Filtration Rules for Human Tissue and Organ Identification

We used LC–MS/MS data from known samples (human kidney, lung and spleen) to establish data filtration rules for including or excluding the source of a questioned tissue as human. All proteins identified with “high confidence” peptides in “human” and “mammalian” database searches were inspected to identify the total number of proteins annotated as human. All identified proteins were sorted sequentially (largest to smallest) in Microsoft Excel (MS Excel), according to (a) sum posterior error probability (PEP), (b) percentage of protein sequence coverage, (c) number of peptides, (d) number of PSMs, (e) number of unique peptides, (f) number of amino acids and (g) molecular weight of the identified proteins. The purpose was to determine if any of the MS/MS metrics would place the proteins annotated as human in a distinct category or representative of the species analyzed.

The quantifiable attributes with the most effect were (a) proteins identified in “mammalian” database search using “high confidence” peptides, (b) number of unique peptides for each identified protein and (c) the percentage of sequence coverage for each identified protein.

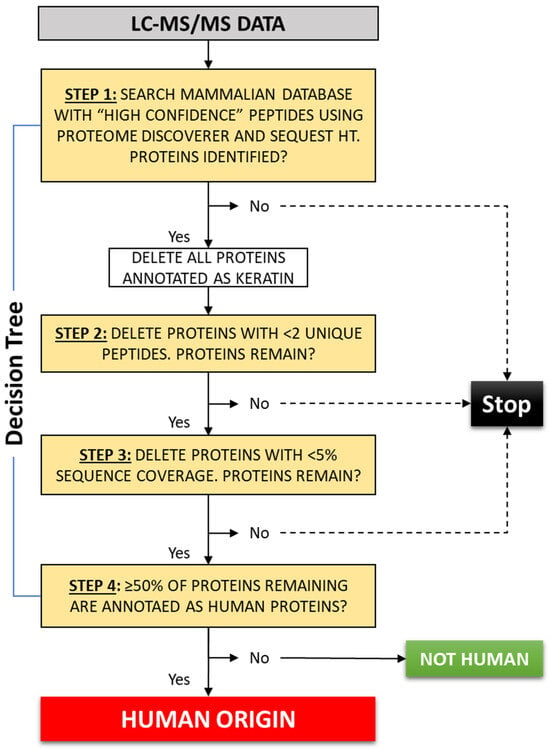

To provide an objective approach for human tissue identification using proteins identified after bottom-up proteomics, a stepwise data filtration process and decision tree were established, in which each node of the tree considers a measurable aspect of the proteomic dataset. To prevent a spurious number of human proteins on the list, all proteins identified as keratins were excluded from the list before the start of data filtration, since keratin is the most common laboratory contaminant, and any found on the list of identified proteins may have been inadvertently introduced by the tissue/organ trafficker, law enforcement officer or laboratory technician.

Each branch of the decision tree represents the outcome of the test, which ultimately leads to a decision on the inclusion or exclusion of the tissue as human. The following process was implemented for human tissue identification:

- (a)

- Step 1: Use high-confidence peptides to search a “mammalian” database with Proteome Discoverer and the Sequest HT algorithm. Export the result to MS Excel and delete any protein annotated as keratin.

- (b)

- Step 2: Delete proteins identified with less than 2 unique peptides.

- (c)

- Step 3: Delete identified proteins with less than 5% protein sequence coverage.

- (d)

- Step 4: Examine the remaining proteins on the list to determine the percentage annotated as human.

If 50% or more of the proteins remaining on the list are annotated as human, then a human cannot be excluded as the source of the tissue.

2.6. Validation of Bottom-Up Proteomics-Based Human Tissue Identification

To test the validity of the proteomic data filtration process for identification of tissue origin, we used (a) MS/MS data files (.raw) generated from 26 mass spectrometry experiments in our database to search a “mammalian” database and, (b) filtered the list of identified proteins according to the established rules in 2.5 above. The legacy LC–MS/MS data used for validation were generated with either Thermo Scientific LTQ-XL, Q Exactive or Orbitrap Fusion Lumos mass spectrometers (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The sources of tissue were human (n = 10), bovine (n = 2), mouse (n = 7), rat (n = 6) and sheep (n = 1). All were anonymized and blinded to the analyst.

3. Results and Discussion

The principal objective of this study was to develop a simple methodology for presumptive identification of human tissue, using data commonly produced in bottom-up proteomics workflow. We were motivated because such an approach will be especially useful in situations when DNA analysis is not possible due to sample breakdown, the DNA result is inconclusive, or a DNA analysis laboratory is not available. Proteins identified in biological evidence by proteomics have historically been used for body fluid, tissue and species determination as well as human identification [6,9], but none of the approaches in the literature for tissue identification involve the filtration of the list of identified proteins following a “mammalian” database search.

3.1. Proteomic Analysis of Known Human and Questioned Tissue

Proteomics analysis of known and questioned tissue was performed to determine if this approach can be used to identify tissue of human origin. The proteomics results reported in this study were obtained by procedures that have been scientifically validated in our laboratory for protein analysis using bottom-up proteomics, which involves isolation of proteins from the sample, tryptic digestion of the proteins, separation and sequencing of the resulting peptides by LC–MS/MS, and searching a species-specific database with the raw MS/MS data to identify proteins [16,17]. We presumed that if peptides in any tissue sample are sequenced accurately, then proteins can be correctly annotated following a species-specific database search. Obviously, the reliability of tissue identification by proteomics using the method described in this paper will be influenced by the accuracy of peptide sequencing and database entries.

Peptides detected in biological samples by LC–MS/MS are classified as high, medium or low confidence peptides. For peptide matching, statistical scores are calculated to estimate the probability and range of uncertainty that a given score would occur randomly [11]. In general, our laboratory uses only “high confidence” peptides in database searches for protein identification. A protein identified with “high confidence” peptides will have an FDR of 1%, those with “medium confidence” peptides will have an FDR of 5%, and those with “low confidence” peptides will have an FDR of 10%. Since high-confidence peptides were used in this experiment, the accuracy of protein identification was expected to be ≥99%.

Due to the statistical nature of the matching relationship, even spectra with confident sequence assignments retain an inherent, albeit often minimal, degree of uncertainty and the potential for a mismatch [11]. Thus, other quality parameters are considered, and independent validation is required for improved stringency. In this study, we considered also the total number of peptides, the number of unique peptides for the identified protein and the percentage of the protein sequence covered. In general, at 1% FDR, the higher the protein sequence coverage and the higher the number of unique peptides, the higher the confidence.

The level of confidence associated with peptide identification by tandem mass spectrometry is also guided by such statistical scores as q-value and PEP. The q-value estimates the rate of misclassification among a set of PSMs, and the PEP is the probability that the observed PSM is incorrect. The FDR measures the error rate associated with a collection of PSMs [22]. We used the Percolator algorithm as a post-processor statistical validator of the results from database searches to boost the number of statistically significant peptide spectrum matches [21]. Percolator provides a reliable statistical context to aid with the interpretation of mass spectrometry results [21]. Although the overall number of proteins detected in a sample is important, the accuracy of identifying individual proteins will likely have the greatest impact on correctly classifying a tissue as human or non-human.

It is expected that all biological specimens submitted for analysis will contain proteins that can be extracted and analyzed by mass spectrometry. In practice, if a human sample is submitted for analysis, a human database is searched for protein identification. The concentrations of proteins in RHK, RHL and RHS were 15.97 mg/mL, 22.03 mg/mL and 20.46 mg/mL, respectively, whereas those for ES1, ES2, ES3 and ES4 were 1.06 mg/mL, 0.82 mg/mL, 1.17 mg/mL and 1.08 mg/mL, respectively. The samples were individually analyzed by LC–MS/MS. The peptides identified with high confidence (p ≤ 0.01) from the MS/MS runs were used to search recently downloaded “human” and “mammalian” sequence databases for protein identification using Proteome Discoverer [18]. The search of the databases resulted in hits and returned several proteins. The total number of proteins identified in the evidentiary samples were fewer than the number identified in the known human samples (Table 1). The average number of proteins identified in the known samples ranged from 165 in the spleen sample to 246 in the kidney sample, and those identified in the questioned samples ranged from 35 in ES1 to 84 in ES2 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Total number of proteins identified in known samples (human kidney, lung and spleen) and questioned samples (ES1–ES4) after human database (HDS) and mammalian database (MDS) searches using high-confidence peptides.

The smaller quantity of proteins identified in the questioned samples is attributable to the chemical treatment because a similar trend was observed in the four questioned samples and not in the known reference samples. The unknown chemical may have caused protein crosslinking, limited solubility of proteins and/or interfered with the efficiency of protein identification by LC–MS/MS. As would be observed in the subsequent results in this paper, the low number of identified proteins in samples apparently does not affect the accurate identification of the tissue origin.

The objective of this experiment was to develop a simple and fast method for accurate human tissue identification using standard bottom-up proteomics data. The intent was not global protein profiling or individualization of the source of tissue. In view of this, a short 60 min gradient was used for peptide separation in the LC step. This could partly explain why the numbers of proteins identified even in the known untreated samples were relatively low compared to what will be expected in a standard proteomics experiment optimized for the identification of the maximum number of proteins possible.

The human and mammalian database searches returned different numbers and types of proteins. Of interest is the fact that not all the proteins identified in the mammalian database search using LC–MS/MS data from known human samples were annotated as human. Specifically, the percentage of proteins annotated as human proteins in the known samples ranged from 62% in spleen to 74% in kidney. Also, the number identified as human in the questioned samples ranged from 70% in ES3 to 74% in ES4 (Table 1). To explain why some of the proteins identified in human kidney, lung and spleen samples following mammalian database searches are annotated as non-human, we performed basic local sequence alignment between the human and non-human forms of some of the proteins using BLAST+ (version 2.16.0., https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi), accessed on 5 December 2024 and confirmed that the human and non-human forms of the proteins annotated as non-human, in human samples, are identical at the amino acid level in those regions that are conserved across the respective species.

This results in a high degree of similarity and explains why some proteins identified in human samples may be annotated as non-human when a “mammalian” database is searched. For example, tubulin, troponin and filamin identified in human kidney, lung and spleen samples were annotated as non-human when the “mammalian” database was searched. Analysis of the sequence with BLAST indicated that rat tubulin, bovine troponin C and mouse filamin are 100%, 99.4% and 98.3% identical to the human forms at the amino acid level. This information is important because it means that searching a “human” database with raw MS/MS data from tissue of an unknown origin may not yield correct tissue identification.

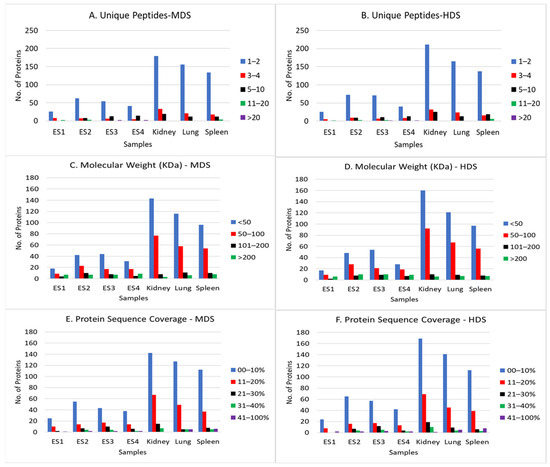

A standard mass spectrometry-based protein identification data file will provide information such as calculated molecular weight of the identified proteins, number of unique peptides and protein sequence coverage irrespective of the origin of the tissue. As shown in Figure 1, the distributions of the peptides and proteins identified in the known and questioned tissue samples following “mammalian” (MDS) and “human” (HDS) database searches have comparable trends and patterns.

Figure 1.

Distribution of unique peptides, molecular weight and protein sequence coverage of the proteins identified in known (human kidney, lung and spleen) and questioned (ES1–ES4) samples. Mammalian (MDS) and human (HDS) databases were searched. Only peptides identified with high confidence were selected. Panels (A,B) are the number of unique peptides used for identification of proteins in each sample. The bar color blue represents 1–2 peptides; red, 3–4 peptides; black, 5–10 peptides; green, 11–20 peptides, and purple, >20 peptides. Panels (C,D) are the calculated molecular weights of the proteins identified in each sample. The bar color blue represents <50 KDa; red, 50–100 KDa; black, 101–200 KDa, and green, >200 KDa. Panels (E,F) are the % protein sequence coverage of the identified proteins. The bar color blue represents 0—10% coverage; red, 11–20% coverage; black, 21–30% coverage; green, 31–40% coverage, and purple, 41–100% coverage.

The numbers of proteins with 1–2 unique peptides were higher (≥70%) in both known and questioned samples, indicating that although the chemical/handling apparently affected the total numbers of proteins identified in the questioned samples, it had no effect on the percentage of unique peptides for identified proteins. The molecular weight distributions of the identified proteins in the known and questioned samples were also comparable, ranging from 6 KDa to 3992 KDa, with most weighing <50 KDa (Figure 1).

Although the sequence coverage for most of the proteins identified in the known and questioned samples was 10% or less, there were proteins in the known and questioned samples with >40% sequence coverage (Figure 1). These findings are important because they indicate that although the total number of proteins identified in samples treated with a chemical may be lower than what is obtained in untreated samples, the quality of any identified peptide may be unaffected, thereby allowing the use of a limited number of identified proteins to establish if a questioned sample is of human or non-human origin.

Considering that in this experiment, up to 38% of proteins on the list of proteins identified in known human samples were annotated as non-human following “mammalian” database search (Table 1), we empirically adjusted the thresholds for Sum PEP, PSM, number of peptides, number of unique peptides, percent sequence coverage and molecular weight of identified proteins to determine if any of these parameters could be used to objectively eliminate all proteins annotated as non-human proteins from the list. No adjustment allowed the removal of only the proteins annotated as non-human. But adjustments of (a) the number of unique peptides for each protein and (b) the percentage of protein sequence coverage had the most influence on the list of annotated proteins. Specifically, when we excluded proteins with less than two unique peptides and proteins with less than 5% protein sequence coverage from the list of identified proteins, the percentages of proteins annotated as human in the human kidney, lung and spleen samples were 83%, 76% and 65%, respectively, and those for ES1, ES2, ES3 and ES4 were 86%, 85%, 67% and 78%, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Proteins identified in known (human kidney, lung and spleen) and questioned (ES1–ES4) tissues and percentage of proteins annotated as human following the implementation of cutoffs for unique peptides and protein sequence coverage.

This means that all the samples (known and unknown) contained >50% of proteins annotated as human after the multi-step filtration process. For this reason, the sources of the four questioned samples (ES1–ES4) were identified as human. This classification was subsequently confirmed via DNA STR analysis. Based on the experimental findings, a decision tree (Figure 2) was developed to provide a standardized approach for presumptive identification of human tissue using bottom-up proteomics data.

Figure 2.

Stepwise process for presumptive identification of human tissue using the list of identified proteins following bottom-up proteomics analysis and searching a “mammalian” database with Proteome Discoverer and Sequest HT search algorithms. If 50% or more of the proteins remaining on the list after the filtration process are annotated as human, then a human cannot be excluded as the source of the questioned tissue.

It should be noted that the filtration process excluded proteins classified as both human and non-human; however, for the identified human samples, a greater proportion of non-human proteins was removed overall. This was observed in all the known and questioned samples we tested except for ES3, where the percentage of human proteins was 68% before filtration and 67% after filtration (Table 2).

Unlike DNA, the proteome is not constant, and the number and type of proteins expressed at any time will be regulated and organ, tissue, and cell type-dependent. Additionally, experience in our laboratory teaches us that the number and type of protein detected at any time by mass spectrometry will be different and affected by pre-analytical variables and the LC–MS/MS method used. Thus, we did not expect that the same numbers and types of proteins would be detected in tissue even if they were from the same source. Ponten et al. [23] performed a study to elucidate the difference in protein expression in cells with distinctly different phenotypes, including hepatocytes from the liver, neurons from the cerebral cortex of the brain, and lymphoid cells from the germinal center of the lymph nodes, and found that the cells display a highly different global protein expression pattern, with only 6% of the identified proteins expressed at the same level in all three cell types. Even when more closely related cell types were studied (glandular cells in the colon, epidermal cells from the skin, and urothelial cells from the bladder), only 17% of proteins were expressed at the same level in all three cells [23]. Taking these findings together, it is apparent that the identification of the origin of a questioned tissue does not have to depend on the specific types and total numbers of proteins identified in the sample because the numbers and types of proteins will vary from one LC–MS/MS run to another.

3.2. Identification of Human and Non-Human Tissue Using Proteomic Data

To determine if the rules established for data filtration illustrated in Figure 2 can be used to identify tissue of human origin, we tested the method with legacy proteomics data from 26 different experiments including human (n = 10) and non-human (n = 16) sources. Some of the samples were treated with formalin, embedded in paraffin and stored at room temperature, and some were embedded in OCT and frozen. This provided an opportunity to determine how chemical treatment may affect the accuracy of human tissue identification using a specific data filtration approach. Other human specimens, such as whole blood and saliva spotted on a counter surface and allowed to dry for at least 24 h, provided an opportunity to test the types of samples that could be encountered at a crime scene. The proteomics data used were produced with low- and high-resolution mass spectrometers, which provided an opportunity to determine if the type of mass spectrometer and sensitivity will affect the accuracy of human tissue identification.

As shown in Table 3, the total number of proteins identified in the samples ranged from 13 in GPB1 to 1133 in R4, and the percentage of proteins annotated as human before any filtration ranged from 13% to 92% in sample M1 and sample GBP1, respectively. After data filtration using the decision tree (Figure 2), the percentage of proteins annotated as human ranged from 0% in B1 and R5 to 100% in GPB1, GPB2, GPB3, DHS1 and DHB1 (Table 3). Using this approach, 100% of the human and non-human samples were correctly classified, demonstrating a sensitivity which we defined as the “correct identification of human tissue as human” and specificity defined as the “correct identification of non-human tissue as non-human” of 100%.

Table 3.

Identification of tissue as human or non-human using bottom-up proteomics data.

The motivation for conducting this experiment stems from the frustration encountered when attempting to identify an evidentiary tissue sample of unknown origin submitted to our laboratory as part of a ritual killing and tissue trafficking investigation. The specimen was immersed in an unknown chemical, which made conventional DNA methodology workflow, including rapid DNA technology [24], unsuccessful. Although a limited number of alleles were eventually recovered using traditional organic extraction and STR DNA techniques, the process required over 2 weeks, multiple extractions, and repeated analyses on the ABI 3500, ultimately recovering only 10% of the targeted alleles. In contrast, the bottom-up proteomics method described here allowed presumptive identification of the source in less than 48 h, and from a single run.

The rationale for choosing 50% as cutoff for this presumptive test is to prevent a false exclusion (false negative) of a questioned tissue sample as human, which is more likely to occur with degraded or chemically treated samples. In the context of tissue and organ trafficking investigations, it is our opinion that because it is a presumptive test, the evidentiary standard for inclusion of a questioned tissue as possibly human should be set at a high level to minimize the risk of false negative results. For instance, if a higher cutoff like 60% were used, the formalin-treated human sample no. 4 (FFPE1, Table 3, 60%) would be considered borderline or inconclusive, whereas the OCT-treated human sample no. 10 (OCT2, Table 3, 59%) would not be considered as being of human origin.

4. Limitations and Perspectives

Despite these and other reported promising proteomics results, especially the rapidly growing relevance of proteomics in forensic science, proteomics will require validation and standardization to ensure reproducibility and legal acceptance of proteomic evidence in court [25]. The proteomic data filtering approach we describe has the potential to provide an objective means of distinguishing between human and non-human specimens quickly, thereby influencing forensic practice. It must, however, be acknowledged that there are important limitations that must be considered before it is universally adopted. For example, the minimum number of proteins that must be identified in different types of samples that enable accurate classification of a sample will need to be determined. This is important because protein detection can be influenced by sample quality, degradation, environmental exposure, and pre-analytical handling, all of which may affect the number of proteins that meet the filtering threshold.

The accuracy of taxonomic assignment depends on the completeness of reference databases, which remain limited for many non-human species. This study exclusively relied on data from UniProt; therefore, it would be beneficial to assess the robustness of the method by using other databases such as the NCBI database.

Forensic proteomics still lack standardized operating procedures similar to DNA, inter-laboratory validation studies, and established error-rate estimates, all of which are critical for reproducibility and eventual legal acceptance. Access to mass spectrometry instrumentation and specialized expertise may further limit the implementation of this approach routinely in many forensic laboratories.

Clearly, the ability to quickly identify the source of tissue can greatly impact forensic practice by offering a fast, alternate or supplementary method to DNA techniques. This will enable crime laboratories to handle larger numbers and types of cases by supporting triage decisions, guiding downstream testing, and assisting investigations involving trafficked tissues, wildlife crime, or highly processed biological materials, where DNA may be degraded or unavailable. Although the method may not be feasible in all forensic contexts, such as samples with severe degradation, complex mixtures, or limited material, continued improvements in workflows, database coverage, and standardization are likely to expand its applicability and acceptance. With further validation, this method can emerge as a valuable complementary tool for rapid and reliable identification of biological materials encountered in tissue/organ trafficking cases and other forensic casework.

5. Conclusions

While this study investigated a limited number of samples and conditions, it is, to our knowledge, the first report demonstrating that the list of identified proteins generated through standard bottom-up proteomics may be filtered and used for presumptive identification of tissue as human or non-human. Using this approach, it was observed that (a) the condition of the tissue examined and (b) the types and total number of proteins identified in each sample did not affect the accuracy of tissue classification as human or non-human. This could be a valuable method for tissue identification when DNA techniques are impossible and individualization of the source of tissue is not necessary. It could serve as an alternative method for human tissue identification when DNA methods fail due to chemical treatment of tissue, because proteins may remain unaffected by chemicals that impede DNA amplification. The approach does not require the detection of specific amino acids or specific protein types, so it can also provide independent confirmation in cases of failed or inconclusive DNA results. Even though these results are promising, it is important to note that only the Proteome Discoverer, SEQUEST HT search algorithms and UniProt database have been evaluated. It is expected that additional testing will be conducted by independent laboratories using a range of sample types, such as skin and mummified specimens, along with varied sample handling procedures, mass spectrometry methods, and search algorithms. This process will help ensure reliability and reproducibility, which are essential prior to routine implementation in fields such as forensics where the accuracy and legal admissibility of evidence are critical.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.I.S.; methodology, S.J.R., J.F. and S.B.S.; formal analysis, S.J.R. and J.F.; writing: original draft preparation, R.I.S.; review and editing, R.I.S. and S.B.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Windber Research Institute (WRI, Protocol #: Pro 00009470), effective from 2002 and re-approved on 2 April 2025 by Advarra IRB.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study through WRI Pro 00009470 and ITSI Biosciences Research Consent Form No. RCF-001.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors R.I.S., S.J.R. and J.F. are currently employed by ITSI Biosciences LLC, Johnstown, PA, USA. The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Negri, S. Transplant ethics and the international crime or organ trafficking. Int. Crim. Law Rev. 2016, 16, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, M. Trafficking and Organs, Tissues, and Cells: An Examination of European and UK Legislation and Gaps European. J. Crime Crim. Law Crim. Justice 2024, 32, 32–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshelemiah, J.C.A.; Lynch, R.E. The Cause and Consequence of Human Trafficking: Human Rights Violations; The Ohio State University Pressbook: Columbus, OH, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, G.J.; Leppert, T.; Anex, D.S.; Hilmer, J.K.; Matsunami, N.; Baird, L.; Stevens, J.; Parsawar, K.; Durbin-Johnson, B.P.; Rocke, D.M.; et al. Demonstration of Protein-Based Human Identification Using the Hair Shaft Proteome. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0160653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somiari, R.I.; Sullivan, A.; Russell, S.; Somiari, S.; Hu, H.; Jordan, R.; George, A.; Katenhusen, R.; Buchowiecka, A.; Arciero, C.; et al. High-throughput proteomic analysis of human infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the breast. Proteomics 2003, 3, 1863–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duong, V.-A.; Park, J.-M.; Lim, H.-J. Proteomics in Forensic Analysis: Applications for Human Samples. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oonk, S.; Schuurmans, T.; Pabst, M.; de Smet, L.C.P.M.; de Put, M. Proteomics as a new tool to study fingermark ageing in forensics. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, K.M.; Zissler, A.; Kim, E.; Ehrenfellner, B.; Cho, E.; Lee, S.I.; Steinbacher, P.; Yun, K.N.; Shin, J.H.; Kim, J.Y.; et al. Postmortem proteomics to discover biomarkers for forensic PMI estimation. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2019, 133, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boroumand, M.; Grassi, V.M.; Castagnola, F.; De-Giorgio, F.; D’aLoja, E.; Vetrugno, G.; Pascali, V.L.; Vincenzoni, F.; Iavarone, F.; Faa, G.; et al. Estimation of postmortem interval using top-down HPLC–MS analysis of peptide fragments in vitreous humour: A pilot study. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2023, 483, 116952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alex, S.; Shehata, T.P.; Gergely, A.I.; de Puit, M. Proteomics in forensics: From source attribution to reconstruction of events. Sci. Justice 2025, 65, 101320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G.J.; McKiernan, H.E.; Legg, K.M.; Goecker, Z.C. Forensic proteomics. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2021, 54, 102529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadsworth, C.; Buckley, M. Proteome degradation in fossils: Investigating the longevity of protein survival in ancient bone. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. RCM 2014, 28, 605–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bunger, M.K.; Cargile, B.J.; Sevinsky, J.R.; Deyanova, E.; Yates, N.A.; Hendrickson, R.C.; Stephenson, J.J.L. Detection and validation of non-synonymous coding SNPs from orthogonal analysis of shotgun proteomics data. J. Proteome Res. 2007, 6, 2331–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheynkman, G.M.; Shortreed, M.R.; Frey, B.L.; Scalf, M.; Smith, L.M. Large-scale mass spectrometric detection of variant peptides resulting from nonsynonymous nucleotide differences. J. Proteome Res. 2014, 13, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mason, K.E.; Anex, D.; Grey, T.; Hart, B.; Parker, G. Protein-based forensic identification using genetically variant peptides in human bone. Forensic Sci. Int. 2018, 288, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastwa, E.; Somiari, S.B.; Czyz, M.; Somiari, R.I. Proteomics in human cancer research. Proteom. Clin. Appl. 2007, 1, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somiari, R.I.; Renganathan, K.; Russell, S.; Wolfe, S.; Mayko, F.; Somiari, S.B. A Colorimetric Method for Monitoring Tryptic Digestion Prior to Shotgun Proteomics. Int. J. Proteom. 2014, 2014, 125482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rispoli, L.A.; Edwards, J.L.; Pohler, K.G.; Russell, S.; Somiari, R.I.; Payton, R.R.; Schrick, F.N. Heat-induced hyperthermia impacts the follicular fluid proteome of the periovulatory follicle in lactating dairy cows. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0227095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The UniProt Consortium. UniProt: The universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D158–D169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Käll, L.; Canterbury, J.D.; Weston, J.; Noble, W.S.; MacCoss, M.J. Semi-supervised learning for peptide identification from shotgun proteomics datasets. Nat. Methods 2007, 11, 923–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The, M.; MacCoss, M.J.; Noble, W.S.; Käll, L. Fast and Accurate Protein False Discovery Rates on Large-Scale Proteomics Data Sets with Percolator 3.0. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2016, 27, 1719–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Käll, L.; Storey, J.D.; MacCoss, M.J.; Noble, W.S. Posterior Error Probabilities False Discovery Rates: Two Sides of the Same Coin. J. Proteome Res. 2008, 7, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontén, F.; Gry, M.; Fagerberg, L.; Lundberg, E.; Asplund, A.; Berglund, L.; Oksvold, P.; Björling, E.; Hober, S.; Kampf, C.; et al. A global view of protein expression in human cells, tissues, and organs. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2009, 5, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turingan, R.S.; Brown, J.; Kaplun, L.; Smith, J.; Watson, J.; Boyd, D.A.; Steadman, D.W.; Selden, R.F. Identification of human remains using Rapid DNA analysis. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2019, 134, 863–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, T.A.; Aravind, G.B.; Arun, M.; Aneesh, E.M. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics in forensic investigations: A focused review of LC MS applications. Egypt. J. Forensic Sci. 2025, 15, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).