Death as Rising Entropy: A Theory of Everything for Postmortem Interval Estimation

Abstract

1. Introduction

Why “Theory of Everything”

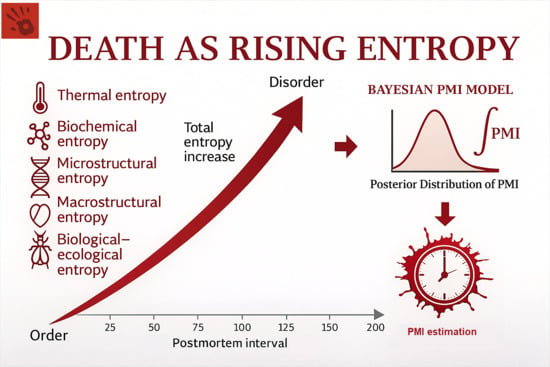

2. Death as Rising Entropy

2.1. Entropy as Progressive Loss of Biological Order

2.2. Why Entropy Provides an Integrative Framework for PMI Estimation

2.3. Translating Empirical Measurements into an Entropic Scale

3. Entropic Domains of Postmortem Transformation

- (1)

- Thermal entropy—dissipation of residual metabolic heat;

- (2)

- Biochemical entropy—diffusion and equilibration of metabolites and ions;

- (3)

- Microstructural entropy—molecular and subcellular degradation (DNA, RNA, proteins);

- (4)

- Macrostructural entropy—loss of tissue and organ coherence observable through imaging;

- (5)

- Biological–ecological entropy—incorporation of the body into the environmental energy flow.

3.1. Methods: Deriving and Comparing Entropy Across Domains

- (1)

- Thermal entropy (S1)—reduction in temperature differentials between body and environment, normalized by the initial gradient (ΔT0).

- (2)

- Biochemical entropy (S2)—equalization of metabolite and ion concentrations, e.g., vitreous potassium or lactate.

- (3)

- Microstructural entropy (S3)—molecular disorganization quantified from fragment-size or conformational distributions.

- (4)

- Macrostructural entropy (S4)—tissue-level disintegration measurable by radiomic or texture-based entropy.

- (5)

- Biological–ecological entropy (S5)—microbial diversification and ecological succession describing the body’s integration into environmental energy flow.

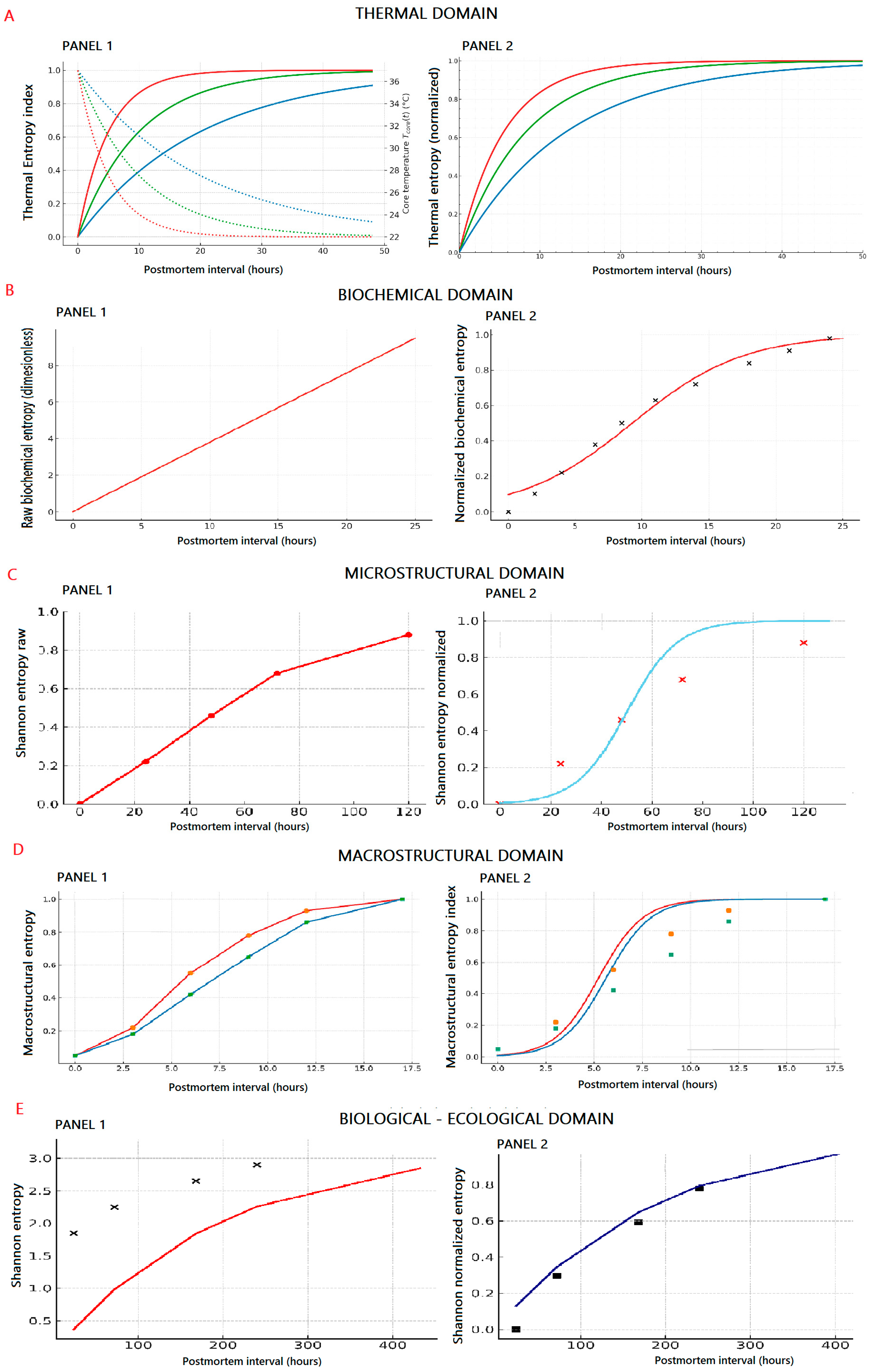

3.2. Thermal Domain: Dissipation of Residual Heat

3.3. Biochemical Domain: Collapse of Metabolic Equilibrium

3.4. Microstructural Domain: Macromolecular Disorganization

3.5. Macrostructural Domain: The Geometry of Disintegration

3.6. Biological Entropy: From Microbial Drift to Ecological Equilibrium

4. Bayesian Integration of Entropic Domains

4.1. Simplified Bayesian Formulation

4.2. Computational Implementation

5. Perspectives and Future Directions

Limitations and Next Steps

6. Concluding Remarks

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADD | Accumulated Degree Days |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| OCT | Optical Coherence Tomography |

| PMI | Postmortem Interval |

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| TBS | Total Body Score |

References

- Henssge, C.; Madea, B. Estimation of the time since death in the early post-mortem period. Forensic Sci. Int. 2004, 144, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madea, B. Estimation of the Time Since Death, 4th ed; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Weisensee, K.E.; Atwell, M.M. Human decomposition and time since death: Persistent challenges and future directions of postmortem interval estimation in forensic anthropology. Am. J. Biol. Anthropol. 2024, 186, e70011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz López, J.L.; Partido Navadijo, M. Estimation of the post-mortem interval: A review. Forensic Sci. Int. 2025, 369, 112412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henssge, C.; Madea, B. Estimation of the time since death. Forensic Sci. Int. 2007, 165, 182–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madea, B.; Doberentz, E. Commentary on: “An Assessment of the Henssge Method for Forensic Death Time Estimation in the Early Post-Mortem Interval” by Heinrich et al. Int. J. Legal Med. 2025, 139, 1137–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubig, M.; Muggenthaler, H.; Sinicina, I.; Mall, G. Temperature-Based Forensic Death Time Estimation: The Standard Model in Experimental Test. Leg. Med. 2015, 17, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockle, D.L.; Bell, L.S. Human Decomposition and the Reliability of a ‘Universal’ Model for Post-Mortem Interval Estimations. Forensic Sci. Int. 2015, 253, 136.e1–136.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Lázaro, S.; Castillo-Alonso, C. Accuracy of estimating postmortem interval using the relationship between total body score and accumulated degree-days: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Legal Med. 2024, 138, 2659–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, M.N.; Finaughty, D.A.; Miles, K.L.; Gibbon, V.E. Inaccuracy of Accumulated Degree Day Models for Estimating Terrestrial Post-Mortem Intervals in Cape Town, South Africa. Forensic Sci. Int. 2019, 296, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moffatt, C.; Simmons, T.; Lynch-Aird, J. An Improved Equation for TBS and ADD: Establishing a Reliable Postmortem Interval Framework for Casework and Experimental Studies. J. Forensic Sci. 2016, 61, S201–S207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marhoff, S.J.; Fahey, P.; Forbes, S.L.; Green, H. Estimating Post-Mortem Interval Using Accumulated Degree-Days and a Degree of Decomposition Index in Australia: A Validation Study. Aust. J. Forensic Sci. 2016, 48, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strete, G.; Sălcudean, A.; Cozma, A.A.; Radu, C.C. Current Understanding and Future Research Direction for Estimating the Postmortem Interval: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelderman, T.; Stigter, E.; Krap, T.; Amendt, J.; Duijst, W. The Time of Death in Dutch Court: Using the Daubert Criteria to Evaluate Methods to Estimate the PMI Used in Court. Leg. Med. 2021, 53, 101970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausius, R. Abhandlungen Über Die Mechanische Wärmetheorie; F. Vieweg und Sohn: Braunschweig, Germany, 1864. [Google Scholar]

- Zanchini, E.; Beretta, G.P. Recent Progress in the Definition of Thermodynamic Entropy. Entropy 2014, 16, 1547–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, O.; Schneider, E.D. The Thermodynamics and Evolution of Complexity in Biological Systems. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 1998, 120, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenreiro Machado, J.A.; Lopes, A.M. Entropy Analysis of Human Death Uncertainty. Nonlinear Dyn. 2021, 104, 3897–3911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uda, S. Application of Information Theory in Systems Biology. Biophys. Rev. 2020, 12, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladyshev, G.P. On Thermodynamics, Entropy and Evolution of Biological Systems: What Is Life from a Physical Chemist’s Viewpoint. Entropy 1999, 1, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristov, V.V.; Buchelnikov, A.S.; Nechipurenko, Y.D. The Use of the Statistical Entropy in Some New Approaches for the Description of Biosystems. Entropy 2022, 24, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailly, F.; Longo, G. Biological Organization and Anti-Entropy. J. Biol. Syst. 2009, 17, 63–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, P.; Costa, E.; Hu, J.; Sukumar, S.; Van Hemert, J.; Walia, R. Information Theory in Computational Biology: Where We Stand Today. Entropy 2020, 22, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, R.L. Entropic Dynamics in a Theoretical Framework for Biosystems. Entropy 2023, 25, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K. A Free Energy Principle for Biological Systems. Entropy 2012, 14, 2100–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyushev, L.M.; Seleznev, V.D. Maximum Entropy Production Principle in Physics, Chemistry and Biology. Phys. Rep. 2006, 426, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrokhin, Y. Two Faces of Entropy and Information in Biological Systems. J. Theor. Biol. 2014, 359, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, D.R.; Wiley, E.O. Evolution as Entropy: Toward a Unified Theory of Biology; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Madea, B.; Henssge, C.; Reibe, S.; Tsokos, M.; Kernbach-Wighton, G. Postmortem Changes and Time Since Death. In Handbook of Forensic Medicine; Madea, B., Ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 75–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Alousi, L.M. A Study of the Shape of the Post-Mortem Cooling Curve in 117 Forensic Cases. Forensic Sci. Int. 2002, 125, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Kabir, C.S. A Simplified Approach to Understanding Body Cooling Behavior and Estimating the Postmortem Interval. Forensic Sci. 2022, 2, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laplace, K.; Baccino, E.; Peyron, P.-A. Estimation of the Time Since Death Based on Body Cooling: A Comparative Study of Four Temperature-Based Methods. Int. J. Legal Med. 2021, 135, 2479–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henssge, C. Post-Mortem Body Cooling and Temperature-Based Methods. In Estimation of the Time Since Death; Madea, B., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; pp. 77–186. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich, F.; Rimkus-Ebeling, F.; Dietz, E.; Raupach, T.; Ondruschka, B.; Anders-Lohner, S. An Assessment of the Henssge Method for Forensic Death Time Estimation in the Early Post-Mortem Interval. Int. J. Legal Med. 2025, 139, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, A.E.; Lamont, I.L. Biochemistry Changes That Occur after Death: Potential Markers for Determining Post-Mortem Interval. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e82011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavolskova, M.; Senko, D.; Bukato, O.; Troshin, S.; Stekolshchikova, E.; Kachanovski, M.; Khaitovich, P. Postmortem Stability Analysis of Lipids and Polar Metabolites in Human, Rat, and Mouse Brains. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locci, E.; Stocchero, M.; Gottardo, R.; Chighine, A.; De-Giorgio, F.; Ferino, G.; Nioi, M.; Demontis, R.; Tagliaro, F.; D’Aloja, E. PMI Estimation through Metabolomics and Potassium Analysis on Animal Vitreous Humour. Int. J. Legal Med. 2023, 137, 887–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chighine, A.; Stocchero, M.; Ferino, G.; De-Giorgio, F.; Conte, C.; Nioi, M.; D’Aloja, E.; Locci, E. Metabolomics Investigation of Post-Mortem Human Pericardial Fluid. Int. J. Legal Med. 2023, 137, 1875–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chighine, A.; Stocchero, M.; De-Giorgio, F.; Nioi, M.; D’Aloja, E.; Locci, E. Translating Metabolomic Evidence Gathered from an Animal Model to a Real Human Scenario: The Post-Mortem Interval Issue. Metabolomics 2025, 21, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelentsova, E.A.; Yanshole, L.V.; Melnikov, A.D.; Kudryavtsev, I.S.; Novoselov, V.P.; Tsentalovich, Y.P. Post-Mortem Changes in Metabolomic Profiles of Human Serum, Aqueous Humor and Vitreous Humor. Metabolomics 2020, 16, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlJuhani, A.A.; Desoky, R.M.; Binshalhoub, A.A.; Alzahrani, M.J.; Alraythi, M.S.; Alzahrani, F.F. Advances in Postmortem Interval Estimation: A Systematic Review of Machine Learning and Metabolomics across Various Tissue Types. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2025, 21, 1428–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wand, A.J.; Sharp, K.A. Measuring Entropy in Molecular Recognition by Proteins. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2018, 47, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poór, V.S.; Lukács, D.; Nagy, T.; Rácz, E.; Sipos, K. The Rate of RNA Degradation in Human Dental Pulp Reveals Post-Mortem Interval. Int. J. Legal Med. 2016, 130, 615–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittner, S.; Ehrenfellner, B.; Monticelli, F.C.; Zissler, A.; Sänger, A.M.; Stoiber, W.; Steinbacher, P. Postmortem Muscle Protein Degradation in Humans as a Tool for PMI Delimitation. Int. J. Legal Med. 2016, 130, 1547–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittner, S.; Gotsmy, W.; Zissler, A.; Ehrenfellner, B.; Baumgartner, D.; Schrüfer, A.; Steinbacher, P.; Monticelli, F. Intra- and Intermuscular Variations of Postmortem Protein Degradation for PMI Estimation. Int. J. Legal Med. 2020, 134, 1775–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battistini, A.; Capitanio, D.; Bailo, P.; Moriggi, M.; Tambuzzi, S.; Gelfi, C.; Piccinini, A. Proteomic Analysis by Mass Spectrometry of Postmortem Muscle Protein Degradation for PMI Estimation: A Pilot Study. Forensic Sci. Int. 2023, 349, 111774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frederick, K.K.; Marlow, M.S.; Valentine, K.G.; Wand, A.J. Conformational entropy in molecular recognition by proteins. Nature 2007, 448, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceciliason, A.-S.; Andersson, M.G.; Nyberg, S.; Sandler, H. Histological Quantification of Decomposed Human Livers: A Potential Aid for Estimation of the Post-Mortem Interval. Int. J. Legal Med. 2021, 135, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero-Urbina, C.; Fors, M.; Vásquez, B.; Fonseca, G.; Rodríguez-Guerrero, M. Histological Changes in Lingual Striated Muscle Tissue of Human Cadavers to Estimate the Postmortem Interval. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2023, 19, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nioi, M.; Napoli, P.E.; Demontis, R.; Locci, E.; Fossarello, M.; d’Aloja, E. Postmortem Ocular Findings in the Optical Coherence Tomography Era: A Proof of Concept Study Based on Six Forensic Cases. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nioi, M.; Napoli, P.E.; Demontis, R.; Chighine, A.; De-Giorgio, F.; Grassi, S.; Scorcia, V.; Fossarello, M.; d’Aloja, E. The Influence of Eyelid Position and Environmental Conditions on the Corneal Changes in Early Postmortem Interval: A Prospective, Multicentric OCT Study. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napoli, P.E.; Nioi, M.; Gabiati, L.; Laurenzo, M.; De-Giorgio, F.; Scorcia, V.; Grassi, S.; d’Aloja, E.; Fossarello, M. Repeatability and Reproducibility of Post-Mortem Central Corneal Thickness Measurements Using a Portable Optical Coherence Tomography System in Humans: A Prospective Multicenter Study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, W.M.; Kunz, T.; Hermans, K.; Bayat, A.R.; Koopmanschap, D.H.J.L.M. The Common Pattern of Postmortem Changes on Whole Body CT Scans. J. Forensic Radiol. Imaging 2016, 4, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagensveld, I.M.; Blokker, B.M.; Wielopolski, P.A.; Renken, N.S.; Krestin, G.P.; Hunink, M.G.; Oosterhuis, J.W.; Weustink, A.C. Total-Body CT and MR Features of Postmortem Change in In-Hospital Deaths. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surat, P.; Meesilpavikkai, K.; Vongpaisarnsin, K.; Nathongchai, R. The Relationship between Postmortem Interval in Advanced Decomposed Bodies and the Settling Ratio of the Liver in Postmortem CT Scan. Forensic Imaging 2023, 33, 200545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, H.; Vangelatos, A.; Gottel, N.; Osculati, A.; Visona, S.; Finley, S.J.; Gilbert, J.A.; Javan, G.T. Effects of Extended Postmortem Interval on Microbial Communities in Organs of the Human Cadaver. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 569630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaldos, M.I.; García, M.D.; Romera, E.; Presa, J.J.; Luna, A. Estimation of Postmortem Interval in Real Cases Based on Experimentally Obtained Entomological Evidence. Forensic Sci. Int. 2005, 149, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschetti, L.; Pradelli, J.; Tuccia, F.; Giordani, G.; Cattaneo, C.; Vanin, S. Comparison of Accumulated Degree-Days and Entomological Approaches in Post Mortem Interval Estimation. Insects 2021, 12, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, R.M.; Tomberlin, J.K. Environmental Factors Affecting Early Carcass Attendance by Four Species of Blow Flies (Diptera: Calliphoridae) in Texas. J. Med. Entomol. 2014, 51, 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohr, R.M.; Tomberlin, J.K. Development and Validation of a New Technique for Estimating a Minimum Postmortem Interval Using Adult Blow Fly (Diptera: Calliphoridae) Carcass Attendance. Int. J. Legal Med. 2015, 129, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, H.R.; Trinidad, D.D.; Guzman, S.; Khan, Z.; Parziale, J.V.; DeBruyn, J.M.; Lents, N.H. A Machine Learning Approach for Using the Postmortem Skin Microbiome to Estimate the Postmortem Interval. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapico, S.C.; Adserias-Garriga, J. Postmortem Interval Estimation: New Approaches by the Analysis of Human Tissues and Microbial Communities’ Changes. Forensic Sci. 2022, 2, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, J.L.; Xu, Z.Z.; Weiss, S.; Lax, S.; Van Treuren, W.; Hyde, E.R.; Knight, R. Microbial Community Assembly and Metabolic Function during Mammalian Corpse Decomposition. Science 2016, 351, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burcham, Z.M.; Belk, A.D.; McGivern, B.B.; Bouslimani, A.; Ghadermazi, P.; Martino, C.; Metcalf, J.L. A Conserved Interdomain Microbial Network Underpins Cadaver Decomposition Despite Environmental Variables. Nat. Microbiol. 2024, 9, 595–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battley, E.H. An Empirical Method for Estimating the Entropy of Formation and the Absolute Entropy of Dried Microbial Biomass for Use in Studies on the Thermodynamics of Microbial Growth. Thermochim. Acta 1999, 326, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren, A.M.; Morrison, H.G.; Lescault, P.J.; Reveillaud, J.; Vineis, J.H.; Sogin, M.L. Minimum Entropy Decomposition: Unsupervised Oligotyping for Sensitive Partitioning of High-Throughput Marker Gene Sequences. ISME J. 2015, 9, 968–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochs, M.F. Bayesian Decomposition. In the Analysis of Gene Expression Data; Parmigiani, G., Garrett, E.S., Irizarry, R.A., Zeger, S.L., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.H.; Nisbet, N.; Ehrett, C.; Tica, C.I.; Atwell, M.M.; Weisensee, K.E. Modeling Human Decomposition: A Bayesian Approach. Forensic Sci. Int. 2025, 367, 112309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaynes, E.T. Probability Theory: The Logic of Science; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pearl, J. The Book of Why: The New Science of Cause and Effect; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Entropic Domain | Experimental Variables (Study Used) | Domain-Specific Entropy Trend/Shape | Entropy Growth Formula—E(t) | PMI from Entropy—t(E) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal (Heinrich et al.) | Core temperature series: Core temperature series: Tcore(t). T0, Tamb. Fitted cooling constant k. | Increasing, exponential decay of temperature gradient. (Entropy expressed as model-based transformation of cooling curves.) | ||

| Biochemical (Chighine et al.) | Aqueous humor metabolomics: amino acids, nucleotides, and energy intermediates. | Logarithmic → sigmoidal saturation. (Entropy modeled from metabolite drift trends described in the study.) | ||

| Microstructural (Battistini et al.) | Proteomic degradation kinetics (LC–MS/MS): titin, desmin, vinculin; fitted km, t0. | Sigmoidal increase reflecting collapse of structural order. (Model-based representation of proteomic breakdown kinetics.) | ||

| Macrostructural (Nioi et al.) | Corneal OCT (open vs. closed eyes): intensity histogram pi; Shannon entropy H = −Σ pi log pi | Quasi-linear → logistic/exponential increase as image contrast decays. (Entropy modeled from OCT-derived texture changes.) | ||

| Biological–ecological (Lutz et al.) | Postmortem microbiome (Lutz dataset): Shannon diversity H′ vs. time; fitted rate kb. | Exponential growth toward equilibrium (diversity increase). (Entropy derived from ecological succession patterns.) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nioi, M.; d’Aloja, E. Death as Rising Entropy: A Theory of Everything for Postmortem Interval Estimation. Forensic Sci. 2025, 5, 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5040076

Nioi M, d’Aloja E. Death as Rising Entropy: A Theory of Everything for Postmortem Interval Estimation. Forensic Sciences. 2025; 5(4):76. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5040076

Chicago/Turabian StyleNioi, Matteo, and Ernesto d’Aloja. 2025. "Death as Rising Entropy: A Theory of Everything for Postmortem Interval Estimation" Forensic Sciences 5, no. 4: 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5040076

APA StyleNioi, M., & d’Aloja, E. (2025). Death as Rising Entropy: A Theory of Everything for Postmortem Interval Estimation. Forensic Sciences, 5(4), 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci5040076