Abstract

Background: Estimating the postmortem interval (PMI) is complicated by extrinsic environmental and intrinsic individual factors. Methods: Improved accuracy may be achieved through a better understanding of desiccation. This study examines moisture loss and desiccation in human remains in western North Carolina, validating previous research in central Texas. Ten donated individuals were placed across three seasonal trials at Western Carolina University’s Forensic Osteology Research Station (FOREST). Soft tissue moisture measurements were recorded from 20 locations on the body using a Delmhorst RDM-3TM meter, and environmental data were recorded on-site. Results: Moisture content declined rapidly until ~500 accumulated degree days (ADD), after which patterns became highly variable. Linear mixed-effects models identified temperature as the strongest predictor of moisture loss, particularly in spring and fall, while precipitation was the most influential in summer, coinciding with rapid skeletonization. Compared to central Texas, western North Carolina exhibited less consistent moisture loss patterns and greater environmental variability. Fixed effects explained 36–63% of moisture variation across body regions, with conditional R2 values modestly higher when accounting for individual differences. Conclusions: These findings highlight the importance of region-specific research for PMI estimation.

1. Introduction

Estimating the postmortem interval (PMI) of unidentified human remains presents a persistent challenge as rate and pattern of decomposition are influenced by a wide array of extrinsic factors (e.g., weather, environment, and geography) and intrinsic variables (e.g., weight, body composition, and presence of trauma). While the stages of decomposition (“fresh,” “active,” “advanced,” and “skeletal”) are well established, the duration and progression of each stage remain highly variable and complex [1]. Additionally, decomposition stages do not always occur in strict sequence, as features of multiple stages often overlap [2,3]. Processes such as desiccation and mummification complicate PMI estimations, as they can arrest decomposition leaving remains in an “advanced” state of decomposition for prolonged intervals ranging from weeks to years [2,3].

While often used interchangeably, desiccation and mummification represent distinct processes. Desiccation refers to the general loss of moisture that occurs throughout decomposition and, like decomposition more broadly, follows recognizable stages of gross soft tissue change including patterned drying, color changes, alterations in soft tissue quality, change in soft tissue layer thickness, and interactions with moisture [3]. Mummification describes the arrest of decomposition resulting from dehydration of soft tissues, which prevent progression to complete skeletonization [2,3,4,5].

Much of the literature on mummification has historically focused on ancient remains (e.g., [6,7,8,9]). Research addressing modern or forensically significant cases is more limited, often comprising isolated case studies [5,10,11] or methodological studies aimed at identification of mummified decedents [12,13,14,15,16]. More recently, efforts have shifted toward understanding the mummification process itself, including retroactive analyses of cases with well-documented PMI data [2,17] and prospective studies conducted at human decomposition research facilities [3,18,19,20]. The need for regionally specific decomposition research has long been recognized in forensic anthropology, given the strong influence of environmental conditions on the PMI [3,21]. Lennartz and colleagues [20] investigated whether patterns of desiccation and mummification could be established in central Texas, which environmental variables impacted affected the process, and whether the rate of mummification could serve as a reliable indicator of the PMI [20]. The authors collected moisture data from five donated individuals at the Forensic Anthropology Research Facility, as well as environmental data over a three-month period. The results demonstrated that desiccation followed a predictable, asymptotic pattern, with temperature emerging as the primary driver factor of moisture loss. Limb and extremity measurements provided the most consistent indicators for PMI estimation.

Natural mummification occurs most often under specific environmental conditions, typically prolonged high temperatures, low humidity, and intense solar exposure [2,11,20]. By contrast, surface soft tissue desiccation is a hallmark of the “active” stage of decomposition and can occur across a wide range of environments [22,23]. Clarifying the duration of desiccation and its potential progression to mummification is critical for the development of accurate, regionally specific PMI models. Building on the pilot research conducted by Lennartz and colleagues [20], this study tests their findings in a distinct climatic region while expanding the dataset through a larger sample size and longer study duration. The goal of this project was to investigate patterns of desiccation and mummification in human soft tissue in relation to the PMI. The objectives of this study were to (1) determine whether desiccation and mummification follow predictable patterns in western North Carolina; (2) identify which environmental factors assessed in this study (e.g., temperature, relative moisture, rainfall, and solar radiation) most strongly influence these processes; (3) assess the role of seasonality in desiccation and mummification; and (4) compare the findings in western North Carolina with those observed in central Texas, particularly with respect to asymptotic moisture loss and environmental drivers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Location

Western Carolina University’s Forensic Osteology Research Station (FOREST), located in Cullowhee, North Carolina, USA, at an elevation of approximately 670 m in the Blue Ridge Mountains, is classified as a warm temperature, fully humid, warm summer climate (Cfb) under the Köppen–Geiger map. This distinguishes it from both the surrounding regions and central Texas, which are categorized as warm temperature, fully humid, hot summer climates (Cfa) [24]. Both western North Carolina and central Texas are warm temperature, fully humid climates with similar latitudes, providing a common ecological framework for comparison. Western North Carolina’s higher elevation and cooler, mild summer contrasts with central Texas’ lower elevation with hotter more arid conditions. Comparing the two regions is therefore valuable for refining PMI models and understanding how subtle climatic differences affect decomposition within broadly similar environments. The study was conducted over a 10-month period (March 2021–January 2022) to capture potential seasonal variation. The study consisted of three seasonal trials: Trial 1 (Spring, March–July 2021), Trial 2 (Summer, June–September 2021, and Trial 3 (Fall, October 2021–January 2022). The trials overlap because data collection continued for each donor until skeletonization; however, the primary decomposition phase aligned with the season of the trial donors were placed in. A winter trial was not possible due to the lack of donors during that interval.

Weather data were collected from an on-site weather station that recorded hourly temperature, precipitation, humidity, and solar radiation. Donors were placed in the original FOREST surface enclosure (~465 square meters) which is in a densely wooded area enclosed by a privacy fence [25]. The small size of the enclosure minimized variation in donor placement and ensured proximity (~12 m) to the weather station.

2.2. Donors

A total of ten individuals (seven males, three females), donated to Western Carolina University (WCU) through the Willed Body Donation Program, were included in this study, ranging in age from 61 to 86 years, height from 170.18 to 187.96 cm, and weight from 47.63 to 95.25 kg (Table 1). Sex and age were obtained from death certificates, while height and weight were recorded from self-reported pre-donor registration questionnaires when available. Donors with visible trauma, including autopsy damage, were not enrolled in this study.

Table 1.

Biological Information of Donors.

Between March 2021–January 2022, donors were distributed across three trials designed to assess seasonal differences in desiccation and mummification. Three donors (WCU 1–3) were assigned to Trial 1 (March 2021–July 2021), three donors (WCU 4–6) were assigned to Trial 2 (June 2021–September 2021), and four donors (WCU 7–10) were assigned to Trial 3 (October 2021–January 2022) (Table 1).

2.3. Data Collection

When donors arrived at WCU, all of their clothing was removed, and an intake procedure was performed to collect baseline moisture measurements and to record initial photographs. Donors were placed within a month of death and stored in disaster pouches within a mortuary cooler, kept between 35 and 36 °C, until placement. Within each trial, donors were placed within one month of one another and remained uncovered in a supine position, permitting natural scavenger and insect access. All donors were placed within 12 m of each other.

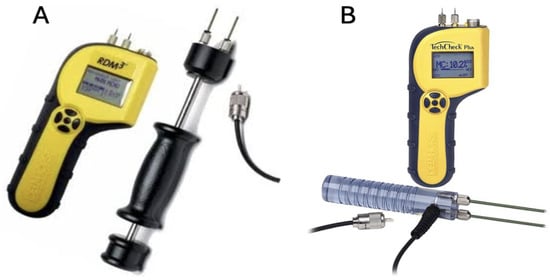

Delmhorst moisture meters (Delmhorst Instrument Company, Towaco, NJ, USA), commonly used to measure moisture in a variety of materials including biological substrates such as wood, were used in this study as they offered the greatest potential to capture the moisture variation in human soft tissues during decomposition [20]. The device measures electrical resistance between the electrodes and converting this into a percent saturation level displayed on the instrument’s screen [21,26]. Therefore, moisture values between 0 and 100 were used for data analysis. Measurements were collected with a Delmhorst RDM-3TM moisture meter with 26-E and 22-E electrodes with insulated tips (Figure 1). The pointed electrodes did not penetrate the skin but were limited to measuring moisture from external soft tissues.

Figure 1.

(A) Delmohorst RDM-3 moistureTM meter with 26-E electrodes; (B) Delmohorst RDM-3 moistureTM meter with 22-E electrodes.

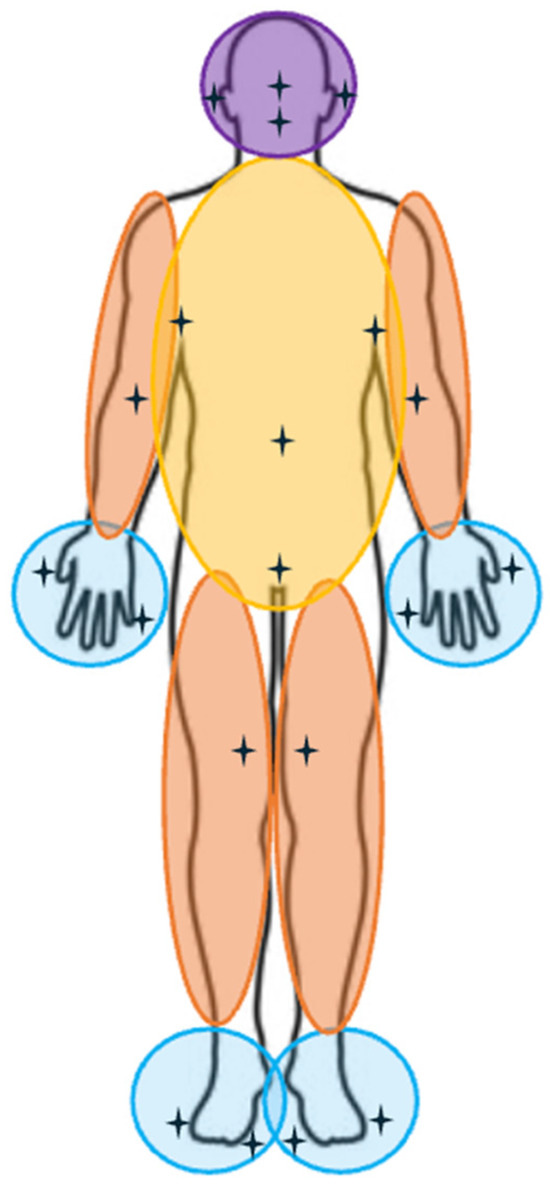

Following the protocol outlined by Lennartz et al. [20], 20 data points were collected from each donor at intake and on weekdays during the trial period, until all points were deemed “inaccessible” due to skeletonization. Data were collected by the first, third, fourth, and fifth authors of this manuscript. Four of the data points were located along the midline (nose, lip, navel, groin), and eight points each were recorded from the left and right sides of the body (Figure 2). Paired data points included the ears, axilla, elbows, first and fifth digits of the hands, mid-thighs, and first and fifth digits of the feet (Figure 2). Each site was also photographed to document decomposition and visible changes in soft tissue moisture. Prior to analysis, data were grouped into four body regions: head, torso, limbs, and extremities (Figure 2). The head region comprised mean measurements from the nose, lip, and ears. The torso included the means from the axilla, navel, and groin. Limb values were calculated from mean elbow and mid-thigh measurements, while extremity values were derived from the mean measurements of the first and fifth digits of the hands and feet. Upper and lower limb and extremity values were subsequently combined and averaged to evaluate symmetry in desiccation.

Figure 2.

Data collection locations and averaged body regions for analytical categorization. Data collection locations are represented with a four-point star. Colored overlays denote each region: the head is indicated in purple; the torso is in yellow; the limbs (both upper and lower) are in orange; and the extremities are in blue.

For each donor, ADD were calculated using a modified version of the method developed by Megyesi and colleagues [27]. ADD quantifies the cumulative thermal energy available to drive biological processes such as soft tissue decomposition. Rather than using the max and min temperature to calculate daily means, the recorded hourly temperatures were averaged, and the resulting mean was used in the calculation of ADD. 0 °C was used as the zero point in the calculation of ADD, and any temperature values below 0 °C were treated as 0. Mathematically, ADD was calculated as:

where = mean daily temperature (°C) on day i; = baseline temperature (0 °C); and n = number of days between placement and end of data collection.

Weather data were collected using a remote HOBO® weather station (Onset Computer Corporation, Bourne, MA, USA), which recorded hourly rainfall, temperature, solar radiation, and relative humidity across all three trials. For analysis, hourly values were condensed into daily (24 h) means (Table 2). The data collected were also visualized in scatterplots using accumulated degree days (ADD) as a standardized scale [27].

Table 2.

Weather data by trial.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted in R version 4.3.1 (R Core Team, 2023). Following the statistical approach outlined by Lennartz and colleagues [20], moisture content for each individual was plotted against ADD as the standardized scale. To visualize the shape of this relationship, a locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOWESS) curve was applied to better capture the trajectory of moisture loss without assuming linearity. This exploratory visualization aids in evaluating whether transformations (e.g., Log transformation) should be included in subsequent regression models.

To evaluate within-individual dependency and justify the use of mixed-effects models, intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were calculated from null models of moisture outputs for each body region. The head exhibited moderate clustering (ICC = 0.37), whereas the torso (0.05), limbs (0.08), and extremities (0.01) showed minimal within-individual correlation, indicating that most variation occurred within rather than between donors. These results supported the inclusion of a random intercept for donors but confirmed that individual-level effects contributed minimally to overall variance in most regions. ADD data were subsequently log-transformed (natural log) to account for the nonlinear relationship between ADD and moisture content and to improve model fit.

Using the log-transformed ADD (logADD), mean daily humidity, mean daily solar radiation, and daily precipitation, mixed-effects models were developed for each body region. Separate models were constructed for each trial as well as for the full dataset. Given the strong correlation among the fixed effects, humidity and solar radiation were mean centered to reduce collinearity, consistent with standard multilevel modeling practices [20,28].

Linear mixed-effects models were then employed to model both fixed environmental effects and random individual effects, accommodating repeated measures on the same donor. This approach partitions variance into within- and between-individual components, capturing shared donor-level variability while testing the effects of environmental predictors on moisture loss. Each model included logADD, mean daily humidity mean solar radiation, and daily rainfall as fixed effects representing environmental drivers of decomposition (Table 3). A random intercept for each donor accounted for baseline differences between individuals due to factors such as body composition or microenvironmental exposure.

Table 3.

Fixed effect coefficients, separated by trial.

Model parameters were estimated using restricted maximum likelihood for variance components and maximum likelihood for model comparison. Residuals and quantile–quantile plots were inspected to ensure assumptions of normality, homoscedasticity, and independence of random effects. Fixed-effect estimates were evaluated using Satterthwaite’s approximation for degrees of freedom, as implemented in the lmerTest package. Model fit was assessed using Akaike Information Criterion and Bayesian Information Criterion to compare relative model performance.

Model explanatory power was summarized using pseudo R2 values for each body region, both by trial and across the full dataset (Table 4). Marginal R2 (R2 M) values represent the variance in moisture loss explained by fixed effects of this study (temperature, humidity, solar radiation, and rainfall), while Conditional R2 (R2 C) values additionally account for the fixed effects and random effects reflecting individual variation between donors (Table 4).

Table 4.

Pseudo R2 values separated by trial.

3. Results

3.1. Weather Data

The weather data were separated by trials, and the results for each trial are in Table 2. Trial 1 (8 March–8 July 2021) experienced temperatures ranging from 2.67 °C to 22.40 °C, with a mean of 15.57 °C. Relative humidity fluctuated widely between 48.39% and 99.30%, averaging 76.06%. Precipitation was sporadic but occasionally heavy, reaching 28.97 mm, though the mean daily rainfall was only 1.65 mm. Mean solar radiation was 109.94 W/m2, with daily values spanning 6.51 to 382.55 W/m2.

Trial 2 (8 June–20 September 2021) temperatures ranged from a low of 15.90 °C and a maximum of 22.56 °C (mean = 20.23 °C). Humidity remained high throughout the trial period (74.88–100%, mean = 92.82%), and precipitation was minimal, averaging 0.04 mm. Solar radiation was also low, averaging 15.61 W/m2 (range = 1.93–51.51 W/m2).

Finally, Trial 3 (11 October 2021–27 January 2022) represented the coolest interval, with temperatures spanning –1.93 °C to 19.69 °C (mean = 7.59 °C). Humidity levels were comparable to those observed in Trial 1 (54.41–99.53%, mean = 77.95%), and mean precipitation was 1.69 mm, with occasional peaks up to 23.62 mm. Mean solar radiation increased to 139.33 W/m2 (range = 4.85–268.08 W/m2).

3.2. Head Observations

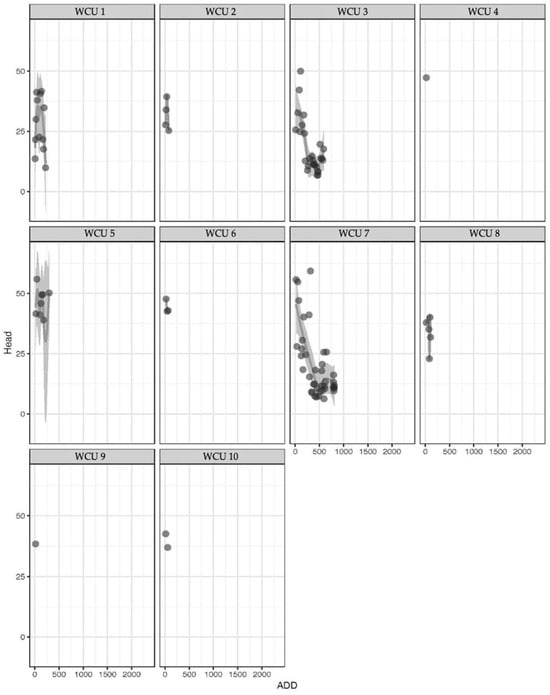

For the head region, R2 M values ranged from 0.59 to 0.63 across individual trials, with 0.58 for the full dataset. R2 C values ranged from 0.63 to 0.67 across individual trials and were 0.63 for combined head data (Table 4). Fixed-effect coefficients were −0.990 to −0.645 for temperature, 0.127 to 0.749 for humidity, −0.065 to 0.044 for solar radiation, and −32.405 to −0.032 for precipitation (Table 3). A scatterplot with a LOWESS curve illustrating head moisture content is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Scatterplot with LOWESS curve of head measurements. The y-axis represents moisture content, while the x-axis represents ADD. The shaded area represents statistically smoothed data.

3.3. Torso Observations

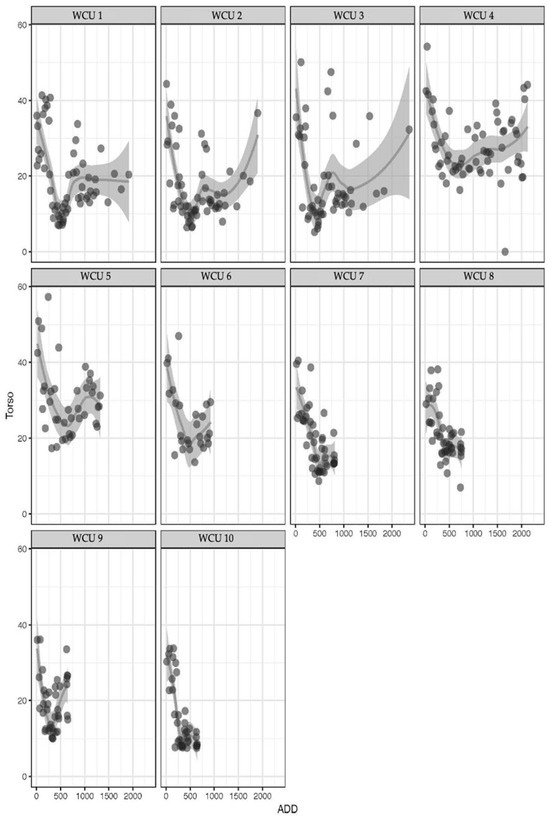

For the torso, R2 M values ranged from 0.22 to 0.48 across individual trials, with 0.36 for the full dataset. R2 C values ranged from 0.32 to 0.50 for individual trials and were 0.49 for combined torso data (Table 4). Fixed-effect coefficients were −6.718 to −4.109 for temperature, 0.319 to 0.573 for humidity, 0.011 to 0.14 for solar radiation, and −0.255 to 4.481 for precipitation (Table 3). A scatterplot with a LOWESS curve illustrating torso moisture content is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Scatterplot with LOWESS curve of torso measurements. The y-axis represents moisture content, while the x-axis represents ADD. The shaded area represents statistically smoothed data. Darker gradients represent overlapping data points.

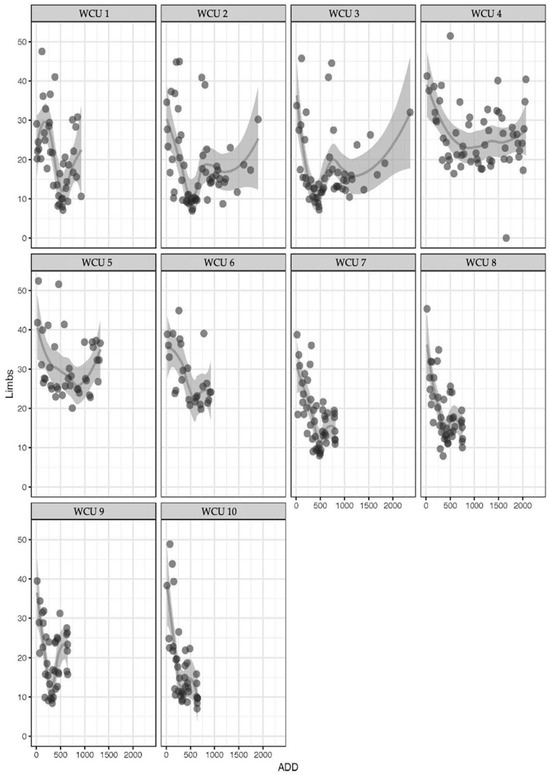

3.4. Limb Observations

For the limbs, R2 M values ranged from 0.23 to 0.51 across individual trials, with 0.37 for the full dataset. R2 C values ranged from 0.26 to 0.51 across seasonal trials, with 0.47 for combined limb data (Table 4). Fixed-effect coefficients were −5.224 to −4.163 for temperature, 0.319 to 0.597 for humidity, −0.014 to 0.041 for solar radiation, and −8.415 to 0.378 for precipitation (Table 3). A scatterplot with a LOWESS curve illustrating limb moisture content is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Scatterplot with LOWESS curve of limb measurements. The y-axis represents moisture content, while the x-axis represents ADD. The shaded area represents statistically smoothed data. Darker gradients represent overlapping data points.

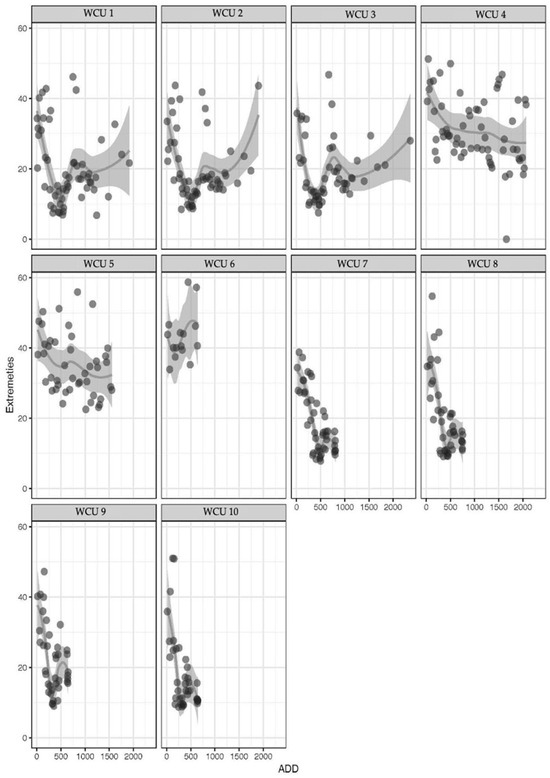

3.5. Extremity Observations

For the extremities, R2 M values ranged from 0.17 to 0.55 across the individual trials, with 0.39 for the full dataset. R2 C values ranged from 0.25 to 0.56 across the seasonal trials, with 0.56 for combined extremity data (Table 4). Fixed-effect coefficients were −6.832 to −3.534 for temperature, 0.368 to 0.621 for humidity, −0.014 to 0.041 for solar radiation, and −8.415 to 0.377 for precipitation (Table 3). A scatterplot with a LOWESS curve illustrating extremity moisture content is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Scatterplot with LOWESS curve of extremity measurements. The y-axis represents moisture content, while the x-axis represents ADD. The shaded area represents statistically smoothed data. Darker gradients represent overlapping data points.

4. Discussion

This study evaluated environmental factors influencing moisture loss in human remains during decomposition across three seasonal trials in western North Carolina, with an emphasis on regional variability and comparison to previously published findings from central Texas [20].

Overall, the three trials captured a wide range of environmental conditions, transitioning from moderate spring weather (Trial 1) through warm and humid summer conditions (Trial 2) to cool, clearer fall/winter conditions (Trial 3) (Table 2). Trial 1 showed moderate temperatures (mean = 15.57 °C) and variable humidity (mean = 76.06%), typical of spring weather with frequent precipitation events. Although rainfall was sometimes intense, average daily precipitation remained low, indicating sporadic but heavy storms. Solar radiation levels were moderate (mean = 109.94 W/m2), consistent with increasing daylight in the spring.

Trial 2 (June–September 2021) represented the warmest and most humid period, with stable high temperatures (mean = 20.23 °C) and persistently elevated humidity (mean = 92.82%) (Table 2). Minimal rainfall and low solar radiation were surprising patterns for western North Carolina; however, the study area was in a densely forested area, limiting the amount of rainfall and sunlight to reach the HOBO weather station.

In contrast, Trial 3 (October 2021–January 2022) captured cooler autumn and early winter conditions (mean = 7.59 °C) (Table 4). Humidity levels remained comparable to Trial 1, though solar radiation increased (mean = 139.33 W/m2), resulting from greater sunlight reaching the HOBO following the loss of foliage on the trees. Precipitation remained moderate but intermittent.

Overall, the dataset effectively captures seasonal environmental variability, which provides valuable contextual information for interpreting experimental outcomes across the trials. Linear mixed-effects models demonstrated that fixed environmental variables (temperature, humidity, precipitation, and solar radiation) collectively explained variation in moisture content across body regions, with marginal R2 values of 0.36–0.63 (36–63%) (Table 4). When individual variability was included, conditional R2 values increased slightly (0.31–0.63; 31–63%), suggesting that although donor-specific factors contributed to overall variation, environmental conditions remained the primary drivers of moisture loss (Table 3).

Moisture content declined rapidly until approximately 500 accumulated degree days (ADD; °C days), a pattern consistent across trials and body regions. After about ADD 500, moisture loss became highly increasingly variable, lacking a clear asymptotic trajectory and showing substantial inter-donor variation, particularly in later decomposition stages. These results suggest that while early desiccation is broadly predictable, long-term patterns are inconsistent in western North Carolina. Furthermore, no true cases of mummification were observed, indicating that the regional climate does not support the sustained desiccation necessary for mummification.

Among the environmental predictors, temperature had the strongest correlation with moisture loss overall, as well as in Trials 1 (Spring) and 3 (Fall) (p < 0.001), consistent with patterns observed in Lennartz et al. [20]. Both trials also exhibited prolonged periods of desiccation. In contrast, Trial 2 (Summer) displayed distinct patterns, characterized by an initial decline in moisture content followed by rehydration, likely from high humidity, and accelerated skeletonization. In this trial, precipitation was the most influential environmental factor, reflected in a strongly negative coefficient for and lower R2 values. Precipitation effects varied considerably by regions, ranging from strongly positive (e.g., extremities in Trial 2: 8.12) to strongly negative (e.g., head in Trial 2: −32.40). However, much of the rainfall occurred early in Trial 2, and skeletonization rapidly rendered data points inaccessible. Increased scavenging activity, particularly by vultures, during this period likely resulted in the expedited skeletonization that furthered weakened the predictive power of the models.

Humidity exhibited a significant positive correlation with moisture content (p < 0.001), indicating that higher ambient moisture slowed desiccation across all trials, with the strongest influence in the head region during Trials 1 and 3. This effect was less pronounced in Trial 2. Solar radiation had little correlation with moisture once temperature and humidity were included in the model. Precipitation showed the most variable influence: while episodic precipitation introduced short-term increases in surface moisture, its overall contribution to cumulative moisture loss was inconsistent.

Comparative analysis between central Texas and western North Carolina revealed significant regional differences. In both regions, moisture content declined rapidly during early decomposition; however, desiccation plateaued earlier and more consistently in Texas, where 0.50–0.55 (50–55%) variation in moisture content was explained by environmental factors. In contrast, western North Carolina trials showed greater variability (0.36–0.63; 36–63%), likely driven by higher and less predictable precipitation and humidity, which complicate desiccation and inhibit mummification.

While this study contributes valuable data on desiccation patterns in a humid temperate environment, several limitations should be considered when interpreting results. The sample size was modest (n = 10), with unequal representation across the three seasonal trials. A larger sample size would allow for greater precision in estimating variability and assessing the consistency of environmental drivers across different times of year. The demographic composition of the sample was predominantly older males (mean age = 73 years). This does not represent typical forensic cases which tend to skew young. Future research should aim to include a broader range of ages, body types, and health statuses to evaluate physiological effects on desiccation rates. The temporal resolution of data collection also presents a limitation. Measurements were restricted to weekdays which may have missed short-term environmental fluctuations. Interobserver variation represents an additional potential source of measurement error. Although standardized procedures were followed, interobserver error was not formally assessed as a part of the research design and should be included in future studies. Finally, scavenger activity was not prevented in this study. Throughout the project, several scavengers, including vultures and small mammals, accelerated soft tissue loss independent of environmental desiccation, thereby introducing additional variability. Future studies should control for scavenger activity. Together, these limitations underscore the complexity of human decomposition and highlight the need for continued, regionally specific research.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that while desiccation follows broadly predictable patterns during early decomposition, its progression in western North Carolina is highly variable after approximately 500 ADD. Temperature emerged as the strongest and most consistent predictor of soft tissue moisture loss across trials, with precipitation only having greater influence in the summer. Humidity consistently inhibited desiccation, while solar radiation contributed minimally, likely due to canopy coverage. No instances of sustained mummification were observed, indicating that the study climate does not promote prolonged desiccation sufficient to halt decomposition.

The results of this project further support the importance of regional context in PMI estimation. While desiccation in central Texas follows a more stable, asymptotic trajectory under hotter and drier conditions, western North Carolina exhibits greater environmental variability, leading to less predictable moisture loss patterns. These findings highlight the need for geographically specific PMI models that account for local climates and their seasonal changes.

Forensic investigators operating in humid, temperate environments should interpret desiccation and moisture loss with caution, as the environmental variability observed in this study can obscure the relationship between decomposition stage and the PMI. The absence of mummification in western North Carolina suggests that the persistence of soft tissue should not be assumed to represent prolonged postmortem intervals, particularly in shaded or moisture-retaining settings. Incorporating regionally validated desiccation thresholds into PMI estimation frameworks will improve accuracy, transparency, and reproducibility in forensic casework across variable climatic zones.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.N.L. and C.A.B. methodology, A.N.L. and C.A.B.; formal analysis, A.N.L.; investigation, C.A.B., C.A.M., M.M.K., C.A.U. and R.L.G.; data curation, C.A.B., C.A.M., M.M.K. and C.A.U.; writing—original draft preparation, C.A.B., A.N.L., C.A.M., M.M.K. and C.A.U.; writing—review and editing, C.A.B., C.A.M., M.M.K., C.A.U. and R.L.G., visualization, A.N.L.; supervision, C.A.B. and R.L.G.; project administration, C.A.B. and R.L.G.; funding acquisition, C.A.B. and R.L.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Western Carolina University Professional Development Grant (Grant No. 101704); Intentional Learning Plan Funding; and the Academic Project Grant.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All donors used in this project were acquired through Western Carolina University’s willed body donation program under the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act per North Carolina (https://www.ncleg.net/EnactedLegislation/Statutes/HTML/ByArticle/Chapter_130A/Article_16.html (accessed on 18 August 2025)) and US State legislation (https://drakelawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/lrvol56-3_kielhorn.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2025)). Additionally, below is a link to the federal legislation governing “human subjects” which indicates that “Human subject means a living individual about whom an investigator (whether professional or student) conducting research.” Since the individuals used in this research were deceased throughout the project period, they do not fall under the designation “human subjects” and therefore fall outside of the purview of IRB in the US (https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-45/subtitle-A/subchapter-A/part-46 (accessed on 18 August 2025)).

Informed Consent Statement

Donors included in this study were willfully donated under the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act per North Carolina State (https://www.ncleg.net/EnactedLegislation/Statutes/HTML/ByArticle/Chapter_130A/Article_16.html (accessed on 18 August 2025)) and US legislation (https://drakelawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/lrvol56-3_kielhorn.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2025)) which acquires informed consent for the decedents to be used in research after their death. Contracts for making an anatomical gift before donor’s death were obtained in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Russell Weaver, Cornell University, for his contribution to the R (version 4.3.1) code utilized for statistical analysis. The authors would like to further acknowledge the individuals who donated their remains to Western Carolina University’s Willed Body Donation Program for making this research possible. This article is a revised and expanded version of a paper entitled “Assessing Patterns of Moisture Content in Decomposing, Desiccated, and Mummified Tissue in the Southeastern United States”, which was presented at the American Academy of Forensic Sciences (AAFS), Orlando, FL, USA, 13 February–18 February 2023 [29].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PMI | Postmortem interval |

| FOREST | Forensic Osteology Research Station |

| ADD | Accumulated Degree Days |

| WCU | Western Carolina University |

| ICC | Interclass Correlation |

| logADD | Logarithmically transformed ADD |

References

- Emmons, A.L.; Deel, H.; Davis, M.; Metcalf, J.L. Soft tissue decomposition in terrestrial ecosystems. In Manual of Forensic Taphonomy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 41–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ceciliason, A.-S.; Käll, B.; Sandler, H. Mummification in a forensic context: An observational study of taphonomic changes and the post-mortem interval in an indoor setting. Int. J. Legal Med. 2023, 137, 1077–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, M.; Baigent, C.; Hansen, E.S. Measuring desiccation using qualitative changes: A step toward determining regional decomposition sequences. J. Forensic Sci. 2019, 64, 1004–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schotsmans, E.M.J.; Van De Voorde, W.; De Winne, J.; Wilson, A.S. The impact of shallow burial on differential decomposition to the body: A temperate case study. Forensic Sci. Int. 2011, 206, e43–e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, F.; Portunato, F.; Pizzorno, E.; Mazzone, S.; Verde, A.; Rocca, G. The need for an interdisciplinary approach in forensic sciences: Perspectives from a peculiar case of mummification. J. Forensic Sci. 2013, 58, 831–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriaza, B.T.; Salo, W.; Aufderheide, A.C.; Holcomb, T.A. Pre-Columbian tuberculosis in Northern Chile: Molecular and skeletal evidence. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 1995, 98, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Najjar, M.Y.; Mulinski, T.M.; Reinhard, K. Mummies and Mummification Practices in the Southern and Southwestern United States; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, M.P.; Chamberlain, A.; Craig, O.; Marshall, P.; Mulville, J.; Smith, H.; Chenery, C.; Collins, M.; Cook, G.; Craig, G.; et al. Evidence for mummification in Bronze Age Britain. Antiquity 2005, 79, 529–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rosso, A.M. Mummification in the ancient and new world. Acta Medico-Hist Adriat. 2014, 12, 329–370. Available online: https://hrcak.srce.hr/file/199074 (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Harding, B.E.; Wolf, B.C. The phenomenon of the urban mummy. J. Forensic Sci. 2015, 60, 1654–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mileva, B.; Tsranchev, I.; Georgieva, M.; Goshev, M.; Alexandrov, A. A rare phenomenon of natural precocious mummification. Cureus 2023, 15, e45626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Yang, C.; Chen, C.; Lee, H.C.; Wang, S. Comparison of rehydration techniques for fingerprinting the deceased after mummification. J. Forensic Sci. 2017, 62, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, R.; Molina, D.K. A novel approach for fingerprinting mummified hands. J. Forensic Sci. 2008, 53, 952–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loreille, O.M.; Parr, R.L.; McGregor, K.A.; Fitzpatrick, C.M.; Lyon, C.; Yang, D.Y.; Speller, C.F.; Grimm, M.J.; Irwin, J.A.; Robinson, E.M. Integrated DNA and fingerprint analyses in the identification of 60-year-old mummified human remains discovered in an Alaskan glacier. J. Forensic Sci. 2010, 55, 813–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, L.O.; Johnson, M.; Cornelison, J.; Isaac, C.; Dejong, J.; Prahlow, J.A. Two novel methods for enhancing postmortem fingerprint recovery from mummified remains. J. Forensic Sci. 2019, 64, 602–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, W.R.; Leone, L. Digital UV/IR photography for tattoo evaluation in mummified remains. J. Forensic Sci. 2012, 57, 1134–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leccia, C.; Alunni, V.; Quatrehomme, G. Modern (forensic) mummies: A study of twenty cases. Forensic Sci. Int. 2018, 288, 330.e1–330.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deo, A. Natural Mummification in Human Carcasses and Analogues in a Temperate Australian Environment. Available online: https://opus.lib.uts.edu.au/handle/10453/178162 (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Finaughty, D.A.; Morris, A.G. Precocious natural mummification in a temperate climate (Western Cape, South Africa). Forensic Sci. Int. 2019, 303, 109948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lennartz, A.; Hamilton, M.D.; Weaver, R. Moisture content in decomposing, desiccated, and mummified human tissue. Forensic Anthropol. 2020, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wescott, D.J. Recent advances in forensic anthropology: Decomposition research. Forensic Sci. Res. 2018, 3, 278–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, A.M.; Passalacqua, N.V.; Bartelink, E.J. Forensic Anthropology: Current Methods and Practice; Academic Press: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Galloway, A.; Birkby, W.; Jones, A.; Henry, T.; Parks, B. Decay rates of human remains in an arid environment. J. Forensic Sci. 1989, 34, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottek, M.; Grieser, J.; Beck, C.; Rudolf, B.; Rubel, F. World map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated. Meteorol. Z. 2006, 15, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, R.L.; Zejdlik, K.; Messer, D.L.; Passalacqua, N.V. The John A. Williams Human Skeletal Collection at Western Carolina University. Forensic Sci. 2022, 2, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurenzi, P. How Does a Pin-Type Moisture Meter Work? Delmhorst Instrument Company Blog. Available online: http://www.delmhorst.com/blog/bid/274196/How-Does-a-Pin-Type-Moisture-Meter-Work (accessed on 16 July 2020).

- Megyesi, M.S.; Nawrocki, S.P.; Haskell, N.H. Using accumulated degree-days to estimate the postmortem interval from decomposed human remains. J. Forensic Sci. 2005, 50, 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finch, W.H.; Bolin, J.E.; Kelley, K. Multilevel Modeling Using R; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, C.A.; Lennartz, A.N.; Klemm, M.M.; Privette, C.A.; Unger, C.; George, R.L. Assessing Patterns of Moisture Content in Decomposing, Desiccated, and Mummified Tissue in the Southeastern United States. In Proceedings of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences (AAFS), Orlando, FL, USA, 13–18 February 2023. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).