Abstract

Background: Cancer-related cachexia remains a significant cause of death, particularly for undiagnosed or untreated malignancies. Lymphomas, especially in uncommon locations, may go unrecognized until their advanced stages. Methods: We report the case of a 34-year-old woman who died from cancer-related cachexia due to undiagnosed, untreated cervical non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Four months postpartum, she reported having excluded malignancy through medical investigations, which were later confirmed to have never been performed. The Judicial Authority ordered an autopsy to determine the cause of death. A narrative literature review was conducted via PubMed using the terms “Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma” and “Autopsy,” limited to English-language human studies published between January 2000 and February 2025. Results: At autopsy, marked fat depletion and a 1350 g cervical mass were found, with significant anatomical distortion and airway narrowing due to epiglottic edema. Microscopic examination identified a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of germinal center origin. A literature review on lymphoma-related autopsy findings identified common diagnostic challenges, including nonspecific symptoms, rapid clinical deterioration, the rarity of certain subtypes, and a lack of medical compliance. Conclusions: Early recognition and proper investigation of lymphoproliferative disorders are crucial to prevent fatal outcomes. Postmortem findings can offer valuable insights into missed diagnoses and inform strategies to reduce diagnostic delay.

1. Introduction

Non-Hodgkin lymphomas constitute 90% of total lymphomas and encompass a broad histological diversity [1]. Most of these malignancies arise from B lymphocytes (85–90% of cases), while the remainder derive from T lymphocytes or Natural Killer cells [2]. The typical site of onset is a lymph node, but other tissues can also be affected. The most common clinical presentation involves the development of indolent lymphadenopathy, with a possible association of B symptoms such as weight loss > 10%, fever, and night sweats [3]. Definitive diagnosis is established through tissue biopsy.

The clinical classification of NHL relies on criteria proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO). Different forms are primarily identified based on the cell of origin (B, T, or NK lymphocyte) and subsequently on morphological, immunophenotypic, genetic, and molecular criteria, integrated with clinical presentation characteristics [4]. Therapeutic approaches vary depending on the disease stage and the presence of prognostic factors, following scoring systems such as the International Prognostic Index (IPI) or the Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index. Available therapeutic strategies include chemotherapy, immunotherapy, radioimmunotherapy, and autologous stem cell transplant, and are selected based on disease and patient characteristics [5].

The 5-year survival rate for NHL in the United States is 74% [6]. Survival is strongly influenced by the stage at diagnosis and mass subtype, as well as the success of specific adopted therapies. Our study presents a rare case of the death of a young woman caused by an untreated advanced non-Hodgkin lymphoma originating from the lymph nodes of the neck, along with a literature review on delayed diagnosis for the aforementioned disease.

2. Case Report

At 5:00 a.m., a 34-year-old woman was found dead in the bedroom by her husband. She was employed as a professional nurse at the local hospital. Information gathered about the deceased’s medical history revealed the recent birth of her second daughter, approximately 4 months prior, without complications for either the mother or the newborn. A review of existing medical records did not reveal any chronic medical conditions. During a police interview, the husband reported that one month before her death, the deceased had contracted a SARS-CoV-2 infection presenting as bronchitis. He further stated that, during this period, she did not take any medication due to breastfeeding. Additionally, he reported that a swelling had appeared on the left side of her neck, about 3–4 cm in size, even before childbirth, attributed to an enlarged lymph node. The husband reported that his wife claimed to have undergone specific medical examinations, which, according to her, revealed no pathological findings, despite the rapid growth of the swelling. However, her reluctance to seek further medical advice or therapy, citing the need to prioritize her pregnancy and the breastfeeding of their second daughter, raises questions about the accuracy of her statements.

The Judicial Authority ordered an autopsy and histological examinations to determine the cause of death. The autopsy was performed 7 days after the death.

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Autopsy Technique and Histological Analysis of Post-Mortem Specimens

Autopsy was performed according to a standardized protocol, including systematic external and internal examination of all body regions, organ dissection, and sampling for histopathological analysis. A bimastoid incision was made, and the scalp with the underlying soft tissues was exposed. The cranial bones were sectioned, and the calvarium was removed to expose the meninges and brain The neck dissection was carried out through a mento-pubic incision, followed by an anatomical layer-by-layer exploration of the cervical structures. The mass was then carefully resected en bloc, encompassing all adjacent structures involved by the lesion.

For microscopic examination, the samples collected during autopsy were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Standard hematoxylin–eosin staining and targeted immunohistochemical analyses were subsequently performed.

3.2. Literature Review Strategy

In addition to recording all relevant case details, a narrative review of the scientific literature was performed. The search was conducted on PubMed using the query: (“Lymphoma, Non-Hodgkin”[Mesh]) AND “Autopsy”[Mesh], focusing on studies published in English involving human subjects from 1 January 2000 to 31 July 2025. For the purpose of this study, only articles written in English and describing cases involving human subjects were included. Publications in other languages or referring to experimental or animal studies were excluded. No filters were applied to exclude specific types of articles. Studies that did not focus on delayed or missed diagnosis, as well as those without full-text availability, were excluded from the review. Two independent reviewers screened the abstracts and, when necessary, the full texts to identify reports describing the reasons for delayed diagnosis of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in individuals who underwent autopsy. The literature search strategy was specifically designed not only to identify the main causes of fatal diagnostic delay—subsequently grouped into four thematic categories described below—but also to include studies directly comparable to our case, with the essential inclusion criterion of a documented and complete autopsy examination.

4. Results

4.1. Autopsy Findings

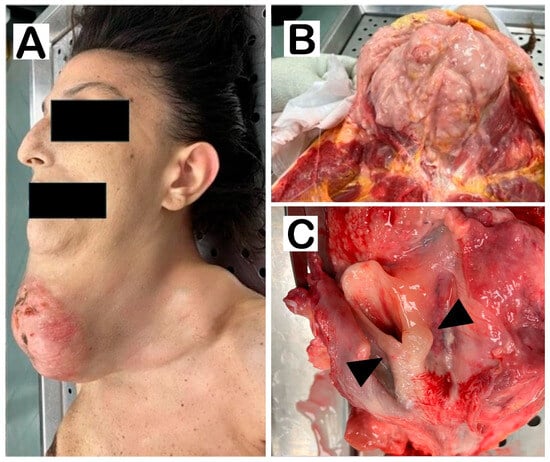

External examination revealed a 34-year-old female, 172 cm in height, in poor general condition. The subcutaneous adipose tissue was sparsely represented, and there was a widespread hypotrophy of the muscle masses. Upon inspection of the neck, signs of traumatic injury were absent. In the mid-paramedian and right anterior cervical region, a round swelling was noted, with a hard consistency, measuring 20 cm × 20 cm × 11 cm, accompanied by erythematous and ulcerated overlying skin. Additionally, a concurrent presence of hard swelling in the lateral cervical and bilateral supraclavicular regions was noted (Figure 1A), causing distortion of normal neck anatomy (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

(A). External examination of the neck, lateral view. Note skin distension with ulcerations. (B). Dissection of the neck shows a large grayish-white mass. (C). At the opening of the esophagus, the neck organs appear compressed, with slight displacement of the trachea. Note how the upper edge of the laryngeal cavity is edematous with irregularities in the closing edge of the epiglottis (arrowheads). No thyroid portions are observed.

Physical examination of the chest and abdomen revealed a marked reduction in subcutaneous adipose tissue and asymmetry in breast volume, with the left breast appearing larger than the right. Diffuse muscle hypotrophy was observed in both upper and lower limbs. An extensive putrefactive greenish discoloration across all abdominal quadrants was noted. Additionally, bilateral cyanosis of the hands was noted.

At the cranial region section, the leptomeningeal vessels appeared congested, with mild flattening of the cerebral sulci consistent with edema. At the neck section, the right sternocleidomastoid muscle and thyroid gland were engulfed but still identifiable. The larynx, esophagus, trachea, and neurovascular bundles were compressed and markedly deviated to the left by the mass. Severe laryngeal and epiglottic edema with airway narrowing was noted; however, the degree of obstruction was not deemed fatal (Figure 1C). Multiple enlarged lymph nodes were present in the left lateral cervical and ipsilateral supraclavicular areas. The neoformation, weighing a total of 1350 g, was isolated and sectioned revealing abundant necrotic/liquefactive material. The lungs were bilaterally congested and edematous, with bronchopneumonic foci and purulent exudate expressed upon compression; no gross evidence of neoplastic lesions was identified. No other significant pathological findings were observed in the remaining organs.

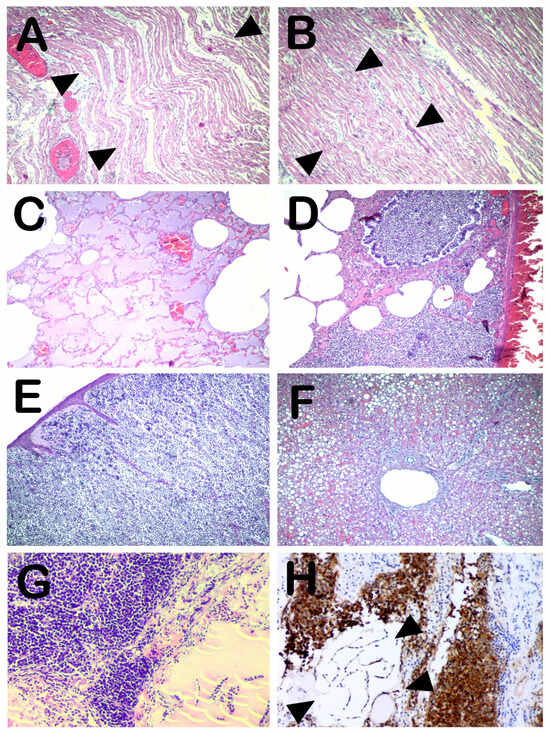

Histological examination showed diffuse cerebral edema and congestion. Further analysis revealed terminal cardiac ischemia with myocardial fiber undulation, without evidence of myocarditis (Figure 2A,B). Lung tissue showed marked congestion with catarrhal bronchitis, as well as pulmonary edema. Some samples showed initial involvement of alveoli around intermediate-to-small-sized bronchi with involvement of polymorphonuclear leukocytes, suggesting incipient bronchopneumonic foci with bacterial etiology. The interstitium was thin with an appearance consistent with the subject’s age and was not infiltrated by inflammatory elements. No findings suggestive of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) were observed (Figure 2C,D). The skin overlying the neck mass was infiltrated by neoplastic lymphoid elements (Figure 2E). Additional findings included hepatic steatosis (Figure 2F), splenic and renal congestion. The microscopic appearance of the mass was consistent with a lymphatic neoplasm, showing ‘geographic map’ necrosis and monomorphic small-to-intermediate lymphoid cells with non-cleaved nuclei, without evidence of Reed–Sternberg cells. The neoplasm involved both intra- and extrathyroidal tissues, lacked a capsule, and infiltrated lateral cervical lymph nodes with capsular breach, surrounding adipose tissue invasion, and skin ulceration. Findings were consistent with a germinal center-derived diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), likely originating from the lateral cervical lymph nodes and extending to the thyroid and adjacent tissues (Figure 2G,H). Immunohistochemistry confirmed CD20 and CD10 positivity in the neoplastic cells, while infiltrated thyroid tissue was negative.

Figure 2.

(A,B). Heart—left (A) and right ventricle (B). Area of myocardial fiber undulation indicating recent cardiac ischemia (arrowheads). No signs of myocardial inflammation are observed (H&E, 40×). (C). Lung—edematous fluid in the alveoli (H&E, 40×). (D). Lung—Catarrhal bronchitis with initial involvement of the closest alveoli, similar to an incipient bronchopneumonic focus. The presence of polymorphonuclear cells suggests a bacterial rather than viral etiology. No signs of ARDS are observed (H&E, 40×). (E). Skin—the skin overlying the neck mass is distended and thinned, massively infiltrated by neoplastic lymphoid elements (H&E, 40×). (F). Liver—the structure is preserved. Moderate steatosis with large hepatocyte liver droplets is observed (H&E, 40×). (G). Cervical mass—a compact proliferation of moderately differentiated, relatively monomorphic lymphoid elements is observed. The neoplasm infiltrates the thyroid tissue, which appears atrophic with follicles containing a small amount of cracked colloid fluid (bottom right) (H&E, 40×). (H). On immunohistochemistry, the lymphoid neoplastic population was uniformly and strongly positive for CD20 and CD10 (data shown in the Supplementary Materials). The infiltrated thyroid tissue is negative (arrowheads). The IHC results indicate the diagnosis of germinal center-related diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

4.2. Literature Review Findings

The literature search using the selected strategies revealed 124 results. Of these, 58 studies were excluded as not pertinent to the aim of our investigation, and 9 were excluded due to the unavailability of full-text access. Despite the application of dedicated filters, two additional studies had to be manually excluded—one written in a non-English language and one based on animal research.

From our comprehensive analysis, four main factors contributing to delayed diagnosis in non-Hodgkin lymphoma were identified: the frequent occurrence of nonspecific manifestations that are difficult to interpret or mimic other clinical conditions (21 articles); the possibility of an aggressive clinical course leading to death before a diagnosis can be established (19 articles); the rarity of certain lymphoma subtypes (14 articles); and the patient’s refusal to undergo further diagnostic investigations (1 article).

5. Discussion

Our case report highlights a case of a young woman who passed away due to neoplastic cachexia from an extensive non-Hodgkin lymphoma originating from the lateral cervical lymph nodes. Autopsy and histological examination revealed a severe overall state of compromise, characterized by marked depletion of subcutaneous and muscular adipose tissue. In addition, the presence of polymorphonuclear leukocytes suggested incipient bronchopneumonic foci of bacterial origin, and laryngeal edema was also observed. The most notable finding was the neoplastic mass, whose macroscopic and microscopic features—including its considerable size—resulted in complete disruption of cervical anatomy and partial compromise of respiratory function, although not to a degree sufficient to cause death. Another factor that may have exacerbated the precarious clinical conditions of the oncological patient was a previous SARS-CoV-2 infection, reported approximately one month before death and clinically symptomatic as bronchitis. Histological and gross examination of the lungs indicated an active bacterial infection at the time of death, consistent with a superimposed process. We therefore concluded that death was caused by severe cachexia, most likely precipitated by a pulmonary infection, as confirmed by both the autopsy and the histological analyses. Importantly, the absence of classical signs of asphyxia—such as conjunctival and visceral petechiae, cyanosis, and marked visceral congestion [7]—supports the interpretation that death was primarily attributable to the underlying neoplastic disease rather than to acute respiratory failure. It is nonetheless important to emphasize that non-Hodgkin lymphomas may lead to progressive airway obstruction, particularly when located in the retropharyngeal [8] or mediastinal regions [9]. In such cases, early surgical management is crucial to prevent potentially fatal outcomes. Other causes of death associated with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, in addition to the inevitable progression of the disease itself, may include infectious, circulatory, or respiratory complications [10]; however, none of these were identified in the present case.

In our patient, the post-mortem investigation revealed a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), which represents one of the most common B-cell subtypes among head and neck lymphomas [11]. That the lymphoma, discovered at post-mortem, was neither diagnosed nor adequately treated during the patient’s lifetime may be attributed to various reasons. The literature analysis highlighted the below motivations.

Firstly, clinical manifestations of the disease may be nonspecific and challenging to interpret. In such cases, the diagnostic and therapeutic delay can lead to the patient’s death, making a post-mortem diagnosis possible only through autopsy [12]. It is essential to highlight that deaths initially appearing to be post-traumatic—for example, due to a delayed splenic rupture—may, in fact, conceal an underlying oncologic condition [13].

Atypical clinical presentations can act as confounding factors, masking the true nature of the disease. Similar scenarios have been documented in cases where clinical signs closely mimic other pathological conditions, leading to misdirected or ineffective treatment approaches. For instance, anaplastic large-cell lymphoma has been reported to mimic TAFRO syndrome—a variant of idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease characterized by Thrombocytopenia, Anasarca, Fever, Reticulin fibrosis of the bone marrow, and Organomegaly [14]. Likewise, cardiac lymphomas have presented with features suggestive of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, with a definitive diagnosis established only through histopathological examination [15].

Another common reason for post-mortem lymphoma diagnosis is the aggressive clinical course of the disease, which may lead to death before a diagnosis can be established [16]. This is particularly true for cardiac involvement, where certain lymphomas—such as diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma—may first present with fatal complications like sudden cardiac death or acute heart failure [17]. The scientific literature also identified cases in which the fatal outcomes were attributed to acute liver failure caused by diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. Notably, the diagnoses were established only post-mortem, following thorough autopsies and subsequent histopathological examinations [18,19].

Additionally, there are exceptionally rare forms belonging to the lymphoma class. Examples include panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma [20] or lymphomas with atypical localization, such as the gynecologic tract, which is rarely involved as the primary or secondary localization [21]. Lastly, another cause of post-mortem lymphoma diagnosis is the patient’s refusal to undergo diagnostic assessments and the necessary therapies. In these cases, the refusal of treatment leads to an inevitable progression of the lesion, ultimately leading to death. In all these cases, it is possible to examine advanced neoplastic forms, even in indolent neoplasms with a good prognosis, such as bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (BALT). These are slow-growing lesions with a good response to chemotherapy and surgery, with 5-year survival rates that can reach 100% [22].

Our case clearly falls into the latter category. The exceptional size of the mass appears to be a consequence of the patient’s refusal to undergo diagnostic investigations. Medical record screening conducted after death did not reveal any specific medical consultations for this condition. It is hypothesized that the woman, aware of the anomaly occurring, decided not to seek medical care. The state of pregnancy may have played a role in this decision.

Interestingly, the literature analysis revealed only one case comparable to ours, involving a 76-year-old woman who presented with a progressively worsening neurological condition that began with paraparesis [23]. She underwent several medical investigations that raised the suspicion of a lymphoproliferative disorder. However, the patient declined a hepatic biopsy, and the diagnosis of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma was therefore established only post-mortem. This case is only partially comparable to ours, as the 76-year-old woman had nonetheless sought medical evaluation and ultimately died in a hospital setting due to multi-organ failure.

In contrast, our case is characterized by a complete refusal of medical contact throughout the course of the illness, which precluded any possibility of timely diagnosis or therapeutic intervention. This aspect is of relevance, as it highlights how patient behavior and delayed medical evaluation may critically influence disease progression and outcome.

The fatal outcome observed in the present case might have been preventable with a timely therapeutic approach. Today, such management benefits not only from well-established scientific knowledge but also from the development of highly efficient decision-support tools based on machine learning. These technologies can generate diagnostic scoring models aimed at the early identification of high-grade lymphomas [24].

6. Conclusions

This case highlights the unusual scenario in which a cervical non-Hodgkin lymphoma was allowed to progress undiagnosed and untreated due to the patient’s complete avoidance of medical evaluation. Post-mortem findings revealed that the cause of death was advanced neoplastic cachexia, further exacerbated by upper airway narrowing and ongoing pulmonary changes consistent with a superimposed bacterial infection, likely occurring in the context of prior SARS-CoV-2 infection. Although the degree of airway obstruction alone would not generally be sufficient to cause death, the combined effects of progressive systemic decline and respiratory compromise proved fatal. The patient’s reluctance to seek medical attention underscores the complex challenges that individual choices and personal beliefs can pose in the diagnostic and therapeutic process. When patients avoid or delay medical consultation, critical opportunities for early diagnosis and intervention may be lost. This case highlights the urgent need to strengthen health education initiatives, especially among postpartum and breastfeeding individuals.

Moreover, the definitive diagnosis in this case was made possible only through a comprehensive post-mortem examination, including histological analysis, which revealed the underlying malignant disease that had gone undetected during life. This underscores the fundamental role of autopsy in uncovering the true cause of death in ambiguous or unexplained cases and in contributing to clinical knowledge, especially when the diagnostic pathway was never initiated or remained incomplete. Autopsy and histopathology thus remain essential tools not only in forensic investigation but also in improving public health awareness and guiding future preventive strategies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/forensicsci5040061/s1, Figure S1. Immunohistochemical staining demonstrating uniform and intense CD10 expression in the lymphoid neoplastic population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.B.; methodology, F.D.-G.; investigation, C.P., S.M., and L.C.; writing—original draft preparation, B.B.; writing—review and editing, S.M. and L.C.; supervision, F.D.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Since only normal clinical practice is described in this case report, formal ethical approval by the Independent Review Board was not required in accordance with the policy of our institution. The individual examined in the current study underwent a forensic autopsy. The collection of data, sampling, and subsequent forensic analyses were conducted with authorization from the Public Prosecutor. Informed consent was obtained through the local Prosecutor’s office, who acted in what was believed to be the best interest of the deceased. The report does not contain personal data. All data are covered by Italian Law—Data Protection Authority (Official Gazette no. 72 of 26 March 2012)—for scientific research purposes. The study complies with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration and with the requirements of European Union GDPR regarding consent.

Informed Consent Statement

The individual examined in the current study underwent a forensic autopsy. The collection of data, sampling, and subsequent forensic analyses were conducted with authorization from the Public Prosecutor. Informed consent was obtained through the local Prosecutor’s office, which acted in what was believed to be the best interest of the deceased. The report does not contain personal data. All data are covered by Italian Law—Data Protection Authority (Official Gazette no. 72 of 26 March 2012)—for scientific research purposes. The study complies with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration and with the requirements of European Union GDPR regarding consent.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study. Data, after adequate anonymization, will be available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

References

- Jamil, A.; Mukkamalla, S.K.R. Lymphoma. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: St. Petersburg, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Silkenstedt, E.; Salles, G.; Campo, E.; Dreyling, M. B-Cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas. Lancet 2024, 403, 1791–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankland, K.R.; Armitage, J.O.; Hancock, B.W. Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Lancet 2012, 380, 848–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swerdlow, S.H.; Campo, E.; Harris, N.L.; Jaffe, E.S.; Pileri, S.A.; Stein, H.; Thiele, J.; Vardiman, J.W. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues; WHO Classification of Tumours; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008; pp. 358–360. Available online: https://hero.epa.gov/reference/786623/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Ansell, S.M. Hodgkin Lymphoma: Diagnosis and Treatment. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2015, 90, 1574–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.Cancer.Org/Cancer/Types/Non-Hodgkin-Lymphoma/about/Key-Statistics.Html (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Porzionato, A.; Boscolo-Berto, R. Assessing Violent Mechanical Asphyxia in Forensic Pathology: State-of-the-Art and Unanswered Questions. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2024, 33, 905–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asoegwu, C.N.; Kanu, O.O.; Nwawolo, C.C. Upper Airway Obstruction Caused by Primary Lymphoplasmacytic Lymphoma of the Retropharyngeal Space: A Case Report. Egypt. J. Otolaryngol. 2021, 37, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, R.; Khadka, S.; Saunders, H.; Helgeson, S. Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma Causing Central Airway Obstruction: A Case Report. Cureus 2025, 17, e77507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, M.; Wang, Y.; Song, W.; Zhang, M. Primary Causes of Death in Patients with Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020, 12, 3155–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.-Y.; Shih, C.-P.; Cheng, L.-H.; Liu, S.-C.; Chiu, F.-H.; Lin, Y.-Y.; Hu, J.-M.; Chu, Y.-H. Head and Neck Lymphomas: Review of 151 Cases. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 40, 215–223. [Google Scholar]

- Barranco, R.; Roncallo, A.; Candosin, S.; Bianchi, R.; Orcioni, G.F.; Ventura, F. Histopathological and Medico-Legal Aspects in a Case of Death Related to an Undiagnosed Cerebral Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Med.-Leg. J. 2025, 93, 110–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albano, G.D.; Zerbo, S.; Spanò, M.; Grassi, N.; Maresi, E.; Florena, A.M.; Argo, A. Delayed Traumatic Rupture of the Spleen in a Patient with Mantle Cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma after an In-Hospital Fall: A Fatal Case. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akamine, K.; Hamada, R.; Makidono, A.; Okita, K.; Saito, O.; Makimoto, A.; Matsuoka, K. Autopsy-proven Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma Mimicking TAFRO Syndrome. Pediatr. Int. 2023, 65, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.W.; Woo, K.S.; Chow, L.T.C.; Ng, H.K.; Chan, W.W.M.; Yu, C.M.; Lo, A.W.I. Diffuse Infiltration of Lymphoma of the Myocardium Mimicking Clinical Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2006, 113, e662–e664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiegl, M.; Greil, R.; Pechlaner, C.; Krugmann, J.; Dirnhofer, S. Intravascular Large B-Cell Lymphoma with a Fulminant Clinical Course: A Case Report with Definite Diagnosis Post Mortem. Ann. Oncol. 2002, 13, 1503–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Martino, A.; Del Re, F.; Barzaghi, C.; Bortolotti, U.; Papi, L.; Pucci, A. Occult Primary Cardiac Lymphomas Causing Unexpected/Sudden Death or Acute Heart Failure. Virchows Arch. 2020, 477, 603–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weeraddana, P.; Odujoko, O.; Bal, S.; Mannapperuma, N.; Maslak, D.; Gupta, G. An Elusive Diagnosis: Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma Masquerading as Acute Liver Failure with Persistent Lactic Acidosis. Am. J. Case Rep. 2023, 24, e941270-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, K.; Kimura, N.; Mabe, K.; Matsuda, S.; Tsuda, M.; Kato, M. Acute Liver Failure Associated with Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: An Autopsy Case Report. Clin. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 13, 1213–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, M.; Kovarik, P.; Puttaswamy, S.; Borkowsky, S. Panniculitis-like T-Cell Lymphoma with an Unusual Clinical Presentation. Leuk. Lymphoma 2006, 47, 1696–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briese, J.; Noack, F.; Harland, A.; Horny, H.-P. Primary Extranodal NK/T Cell Lymphoma (‘Nasal Type’) of the Endometrium: Report of an Unusual Case Diagnosed at Autopsy. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 2006, 61, 164–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattedi, R.L.; Bernardi, F.D.C.; Bacchi, C.E.; Siqueira, S.A.C.; Mauad, T. Fatal Outcome in Bronchus-Associated Lymphoid Tissue Lymphoma. J. Bras. Pneumol. 2007, 33, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Fino, C.; Arena, V.; Hohaus, S.; Di Iorio, R.; Bozzoli, V.; Mirabella, M. Intravascular Large B-Cell Lymphoma Presenting as Slowly Progressive Paraparesis with Normal MRI Features. J. Neurol. Sci. 2012, 314, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zijtregtop, E.A.M.; Winterswijk, L.A.; Beishuizen, T.P.A.; Zwaan, C.M.; Nievelstein, R.A.J.; Meyer-Wentrup, F.A.G.; Beishuizen, A. Machine Learning Logistic Regression Model for Early Decision Making in Referral of Children with Cervical Lymphadenopathy Suspected of Lymphoma. Cancers 2023, 15, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).