Abstract

As known in forensics, heat stroke deaths diagnosis is made by exclusion. In fact, in heat-related deaths, the gross and histologic postmortem findings are not pathognomonic, and biochemical investigations are not specific. Therefore, in such cases, a detailed examination of the circumstantial data and autopsied findings is necessary to exclude other possible causes of death. A case of fatal heat stroke of an elderly woman is reported. This case was diagnosed by examining the above elements in combination with immunohistochemical detection of heat shock proteins (HSPs). We then performed a narrative review of the literature on the subject to compare our case with similar ones. In view of the diagnostic complexity of heat-related deaths, we consider it essential to outline the state of the art on this topic. Our results may be a useful tool to orient forensic investigations into these types of deaths.

1. Introduction

Heat stroke (HS) is a condition of sudden and significant increase in body temperature. It may be due to exposure to high environmental temperature (“non-exertional HS”) and/or to intense physical exercise (“exertional HS”) [1]. In both cases, if the body fails to dissipate the heat, it can trigger multi-organ damage that can be irreversible and at times lethal.

Due to climate change, the risk of heat stroke death is increasing in all regions of the world. As recently highlighted by the World Health Organization, scientific evidence has shown that between 2000 and 2019 there were approximately 489,000 heat-related deaths each year, of which 45% were in Asia and 36% were in Europe [2]. In the summer of 2022, there was a record number of deaths from heat stroke, and Italy ranked first among European countries, with more than 18,000 deaths. [3]. In addition, despite increased awareness and prevention on the issue, child heat stroke deaths in vehicles remain frequent. According to a report published by the National Safety Council, in 2023 there were 29 cases in the United States [4].

The “National Association of Medical Examiners Ad Hoc Committee on the Definition of Heat-Related Fatalities” suggests the use of two different terms to indicate fatal heat strokes. It is preferable to use the term “heat stroke death” or “hyperthermia death” only for cases where an antemortem body temperature is ascertained to be ≥40.6 °C (≥105 °F). Instead, the Association recommends the use of the definition “heat-related death” in cases where the antemortem body temperature is unknown, but circumstantial data suggest prolonged exposure of the decedent to high ambient temperature, and another independent cause of death cannot be identified [5]. Although the extension of the definition was crucial to reducing the risk of underestimating deaths (body temperature at collapse can rarely be established and therefore cannot be considered as the sole diagnostic element), the risk of underestimation remains substantial. In fact, the ambient temperature is also often not detected or is not indicative; moreover, in these types of deaths, there are no macroscopic or microscopic findings with pathognomonic value, and they are variable depending on the type and duration of exposure to heat. Postmortem biochemical investigations—e.g., myoglobin or pituitary hormones levels—have also been shown to be nonspecific [6] and only useful as a diagnostic confirmation in the presence of other suggestive elements [7]. Consequently, the diagnosis of heat-related death results from a combination of circumstantial antemortem data, investigative and forensic observations, and nonspecific autopsy findings. Although heat deaths remain diagnoses of exclusion, postmortem immunohistochemical detection of heat shock proteins (HSPs) can be a useful support. HSPs are intracellular chaperones of variable molecular weight induced by stress conditions [8]. HSPs can be induced in response to various physiological and pathological conditions, such as hyperthermia, infection, cancer, ischemic stimuli, hypertension, and atherosclerosis, as well as exposure to toxic substances [9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Because HSPs are not specific heat-related death markers, their use in forensics is discussed. They are most often used as vitality markers for exposure to high temperatures. In other words, the immunohistochemical representation of HSP expression could be useful in differentiating between vital and postmortem heat exposure [16].

2. Case Report

We report the case of a 75-year-old woman who was found dead in August at around 19:00 p.m. in the outskirts of Rome. At the place of discovery, the vegetation was abundant and varied but not high enough to create shaded areas. According to local weather reports, the outside temperature on that day was 30 degrees, with peaks of 35 degrees and a humidity rate > 60%.

According to the testimony of her children, the woman lived alone about 2 miles away from the place of discovery. Presumably, that morning, the woman had left the house after having breakfast. This hypothesis was based on the finding of food residues on the dining table that were absent the night before. The day before, one of the children had gone to his mother’s house to assist her. The next morning, the children tried unsuccessfully to contact their mother, so they alerted the police.

Based on medical records of the attending physician, the woman was in perfect physical health. However, she had been diagnosed with dementia (of unspecified origin) two years earlier. The woman was assisted by her children at a distance and often by a neighbor who was away on summer holidays. Based on the testimonies collected, the woman needed assistance because in recent months she had experienced serious memory gaps and spatial and temporal disorientation.

The subject was found supine and wearing only a cotton tank top and cotton underpants. No personal objects were found next to the body. They were all found at the house.

Rigor mortis was widespread in all muscles. The hypostases were pinkish, fixed, and located on the back side of the body. The body temperature was not measured.

The external examination of the corpse showed skin slippage and erythema in the areas exposed to direct sunlight and not covered by clothes. These signs were compatible with superficial sunburn. Only early signs of decomposition were found such as clouding of the cornea and greenish discoloration of the skin of the anterior abdominal wall.

The examination of the body was negative for defensive and offensive injuries.

A complete autopsy was performed.

The body was 155 cm long and weighed about 40 kg (Body Mass Index of about 16.6 kg/m2).

The brain was edematous and congested. The lungs were edematous and congested, and petechial hemorrhages were detected over pleural surfaces. The heart walls were free of lesions. Serial sectioning of the coronary arteries showed widespread calcifications and no critical stenosis (≤50%).

The gastric mucosa, the spleen, and the renal surface bilaterally showed petechial hemorrhages. The stomach and the bladder were empty. The gross examination of other organs was unremarkable.

A routine microscopic histopathological study was performed by using formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sectioned at 4 µm and stained with hematoxylin–eosin and Weigert elastic.

In addition, immunohistochemical investigations of the scalp, brain, left arm skin, and right arm skin samples were performed utilizing monoclonal antibodies anti-heat shock protein (HSP 27, 70, 90).

Samples of skeletal muscle were taken from the biceps brachii and pectoralis major muscles. A histological examination of striated muscles showed only marked edema in the absence of necrosis and structural alterations.

The liver was also widely congested, and only disseminated erythrocytes were found in the perifollicular area of the spleen.

The kidneys showed signs of acute tubular necrosis and neutrophil infiltration.

The microscopic structure of the lungs was characterized by acute emphysema with rupture of the alveolar septa. Red blood cells and macrophages were present.

The toxicology test, performed on a blood sample, was negative for drugs, alcohol, and the most common psychotropic drugs.

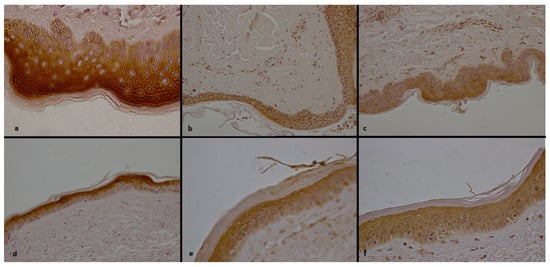

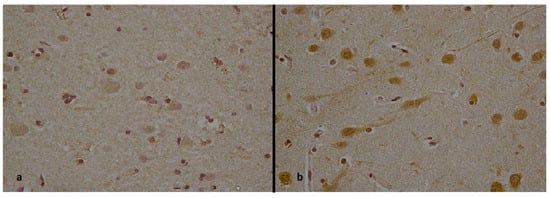

The cutaneous heat injury was confirmed by the positive results to the immunohistochemical reaction for HSP 27, 70, and 90 (Figure 1). Instead, the immunohistochemical reaction of the brain was only positive for HSP 70 and 90 (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Heat-related changes in epithelium of the skin of the left arm ((a) HSP 27; (b) HSP 70; (c) HSP 90) and the right arm ((d) HSP 27; (e) HSP 70; (f) HSP 90).

Figure 2.

Heat-related changes in the brain ((a) HSP 70; (b) HSP 90).

The cause of death was attributed to acute cardiorespiratory failure caused by heat stroke.

3. Discussion

To compare our case with similar ones and to outline the state of the art on heat stroke deaths, we performed a narrative review on the topic. Between November 2023 and January 2024, we searched case reports of heat stroke deaths in scientific databases (PubMed, Google Scholar, Web of Science) using the terms “death by heat stroke”, “death by heat”, and “fatal heat stroke”. We carried out a first selection of articles by reading the titles and abstracts; this selection was carried out individually by two authors. Then, two other authors performed the second selection by studying the articles and identifying the final study sample.

We report and summarize the salient results of a literary review of cases of fatal heat stroke in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summarized literature review on heat stroke deaths.

As our review showed, heat stroke death and heat-related death occur frequently in infants during sleep due to overlapping of clothing and blankets and/or exposure to high environmental temperature [17,22]. Our review also confirmed that fatal heat stroke is common in children who are forgotten in parked vehicles, especially on warm days and under the rays of the sun [5,26,27,35]. Zhou Y et al. and Ohshima T et al. described cases of HS deaths resulting from electric blankets use [21,31]. Fineschi et al. reported a unique case of an 8-day-old male infant found dead in an incubator from a heat stroke [29]. Only Alunni V. et al. [34] described a case of fatal heat stroke of a child confined inside an unpowered icebox in the absence of environmental hyperthermia. To assess the diagnosis of heat stroke death, the authors performed physiological experiments, which suggested that death by asphyxia was less likely. Instead, the review showed that heat-related deaths of adults are more frequently due to intense physical exertion with high ambient temperatures. In fact, the literature describes heat-related deaths occurring during or after intense physical exercise [18,19,23], strenuous working [20,32,33], military training [28], or high-intensity recreational activities [36]. In addition, in many heat-related cases, death was associated with alcohol or drug intake [24,25,36] which was sometimes considered a contributing factor to death [5,36]. Finally, the literature describes cases of heat-related deaths in circumstantial data suggestive of suicide [37].

The deceased was elderly in only one case [25]. To the best of our knowledge, there are no cases in literature of heath stroke deaths of elderly people suffering from dementia. It is also noteworthy that in most cases there were circumstantial elements which suggested a heat-related death. This showed that, in the absence of such elements, the diagnosis of heat stroke death is very complex.

There are no cases of elderly people who died in circumstances like those we have described. This result is probably because in elderly people, in cases of suspected heath stroke death, comorbidities coexist more frequently and must be excluded as alternative causes of death. Therefore, in these cases, heat stress is more often considered not as the cause of death but as a contributing condition to death. Conversely, in our case, heat stroke can be considered the only cause of death, which is also because there are no other alternative pathologies with causal value. This was demonstrated both by the woman’s medical history and by the absence of significant autoptic, histological, and toxicological findings.

As in our case, the body temperature was not available in many cases [16,17,22,25,28,29,30,35,36,37]. In other cases, the body was found in a state of decomposition, which does not allow body temperature measurement [25,37]. This detection was more reliable in cases where the death occurred in hospital [18,19,20,21,23,26,28,33,36,38].

Moreover, our study confirmed that the body temperature is dependent on the duration of exposure to heat and the time between collapse and death and between death and discovery of the body.

Relative to the external examination, the most frequent finding concerns skin burns of varying degrees [21,24,25,26,29,30,31,33,35], notably represented in cases of direct skin exposure to heat sources (such as electric blankets [21,31] or incubators [29]) or prolonged exposure to sunlight (as in the case of people found dead in parked cars [24,26,35] or working in the sun [33]). In addition, dehydration signs [26,27,29,36] are present in many cases and skin bruises in some others [5,36]. Even in our case, the corpse skin unprotected by clothing showed signs of superficial sunburns. In addition, in most cases described, there were no injuries or signs of violence on the body, as in our case.

The literature review confirmed that heath stroke deaths are not associated with autoptic or histological pathognomonic findings, particularly if the survival interval is short [39,40]. Postmortem signs are mostly nonspecific and due to antemortem agony, organ failure, and hemorrhagic diathesis, the ultimate causes of heat death.

Indeed, the most recurrent autopsy results are petechial visceral and serous hemorrhages mostly localized in the thoracic region [5,17,21,22,26,29,33,35,36,37] and confirmed by a histological examination. In our case, the autopsy showed widespread hemorrhage petechiae in many of the organs examined (lungs, stomach, spleen, and kidneys). Other nonspecific macroscopic findings were congestion and multi visceral edema.

Our review also showed that histological findings often merely confirmed gross results. However, in some cases, histological examinations detected renal tubular necrosis [18,20,33,37] and hepatic necrosis [28,31,37]. Signs of myolysis or muscle necrosis were found in only two cases [22,26]

In our case, the histological examination was capable of detecting microscopic signs of acute pulmonary emphysema (alveolar distension and rupture of the interalveolar septa). These histological findings—which require a differential diagnosis with asphyxia dynamics—are remarkable because they have been found only in one other case in the literature [34].

In our case, histological examinations confirmed the infiltration of erythrocytes into the tissues where gross hemorrhages were found. The kidneys showed signs of acute tubular necrosis and infiltration of neutrophil granulocytes. Our histological results are consistent with a heat stroke survival time of <12 h [41].

As our review has shown, only rarely have biochemical and physiological investigations been employed for the diagnosis of fatal heat stroke. Only in two cases was the level of myoglobin measured in blood and/or urine [34,37], and only in one case was the level of pituitary hormones measured in peripheral blood [34].

Finally, it is important to highlight the low use of immunohistochemical investigations aimed at postmortem detection of HSPs (heat shock proteins) [16,29,38]. Bazille et al. [38] described three heat-related deaths, highlighting the inverse correlation between survival time of the subjects and the brain expression of HSPs. In fact, the expression of HSP was highest in the cerebellum of the case where the subject died 28 h after heat stroke. It was mild in the case where the subject died 1 month after the heat stroke, and absent in the case where the subject survived for 2 months after the heat stroke. Wegner et al. [16] described two sauna-associated deaths and showed that, despite vital heat exposure, in the first case, no expression of HSPs was found. The authors hypothesized that this could be due to a genetic polymorphism which could have an influence on the grading of the immunohistochemically visualized heat shock protein.

In our case, the expression of HSPs was detected in the skin tissues, potentially suggestive of the exposure of the woman to very high temperatures when she was still alive. So, this immunohistochemical result—together with the circumstantial, autoptic, and toxicological findings—has contributed to the diagnosis of the cause of death.

To conclude, our study confirmed that the forensic diagnosis of heat-related deaths is based on a set of multiple data obtained from on-site inspection and study of the circumstantial data, autopsy, and toxicological examination. These data—already unspecific—are not always available, with the risk of underestimating this type of death. Especially considering that the diagnosis is still made by exclusion, it is crucial that all these data are collected accurately. Especially in cases like ours where the diagnosis is particularly complex, it is also essential to conduct a thorough investigation of the clinical history of the subject. Finally, immunohistochemical investigations are still poorly applied in such death circumstances, although they represent a tool of investigation of undoubted utility.

4. Conclusions

Our study results highlighted the complexity of diagnosing heat stroke deaths. In view of the little use of immunohistochemistry demonstrated by our review, further studies are needed to elucidate the role of HSPs in forensic diagnosis of heat-related deaths. This will be essential to understanding the actual forensic usefulness of HSP detection in these circumstances. Our study is far from conclusive in this respect but, in our opinion, can be a valid starting point.

In heat stroke deaths, there are no specific signs that allow immediate diagnosis without further investigation. On the contrary, diagnosis is the result of a set of analyses, each of which makes an important contribution. As proved by our case, the medical history of the subject and circumstantial data can help to shed light on the dynamics of death. Especially when the cause of death is suspected and there are no alternative causes of death, immunochemical investigations for specific proteins released from high temperature exposure (HSPs) may also be useful.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C. and C.C.; methodology, A.C.; validation, A.C.; formal analysis, A.C.; investigation, C.C.; data curation, C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, C.C.; writing—review and editing, A.C.; visualization, B.B. and S.D.S.; supervision, L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

The case described is a forensic case. Informed consent is not required for postmortem investigations.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bouchama, A.; Abuyassin, B.; Lehe, C.; Laitano, O.; Jay, O.; O’Connor, F.G.; Leon, L.R. Classic and exertional heatstroke. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2022, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Guo, Y.; Ye, T.; Gasparrini, A.; Tong, S.; Overcenco, A.; Urban, A.; Schneider, A.; Entezari, A.; Vicedo-Cabrera, A.M.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of mortality associated with non-optimal ambient temperatures from 2000 to 2019: A three-stage modelling study. Lancet Planet Health 2021, 5, e415–e425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballester, J.; Quijal-Zamorano, M.; Méndez Turrubiates, R.F.; Pegenaute, F.; Herrmann, F.R.; Robine, J.M.; Basagaña, X.; Tonne, C.; Antó, J.M.; Achebak, H. Heat-related mortality in Europe during the summer of 2022. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://injuryfacts.nsc.org/motor-vehicle/motor-vehicle-safety-issues/hotcars/ (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Donoghue, E.R.; Graham, M.A.; Jentzen, J.M.; Lifschultz, B.D.; Luke, J.L.; Mirchandani, H.G.; National Association of Medical Examiners Ad Hoc Committee on the Definition of Heat-Related Fatalities. Criteria for the diagnosis of heat-related deaths: National Association of Medical Examiners. Position paper. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 1997, 18, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, B.L.; Ishida, K.; Quan, L.; Taniguchi, M.; Oritani, S.; Kamikodai, Y.; Fujita, M.Q.; Maeda, H. Post-mortem urinary myoglobin levels with reference to the causes of death. Forensic Sci. Int. 2001, 115, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmiere, C.; Mangin, P. Hyperthermia and postmortem biochemical investigations. Int. J. Legal Med. 2013, 127, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinkmeier, H.; Ohlendieck, K. Chaperoning heat shock proteins: Proteomic analysis and relevance for normal and dystrophin-deficient muscle. Proteom. Clin. Appl. 2014, 8, 875–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinova, E.V.; Chipigina, N.S.; Shurdumova, M.H.; Kovalenko, E.I.; Sapozhnikov, A.M. Heat Shock Protein 70 kDa as a Target for Diagnostics and Therapy of Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Diseases. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2019, 25, 710–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zininga, T.; Ramatsui, L.; Shonhai, A. Heat Shock Proteins as Immunomodulants. Molecules 2018, 23, 2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.W.; Seo, J.P.; Jung, G. Heat shock protein 70 and heat shock protein 90 synergistically increase hepatitis B viral capsid assembly. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 503, 2892–2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pockley, A.G.; De Faire, U.; Kiessling, R.; Lemne, C.; Thulin, T.; Frostegård, J. Circulating heat shock protein and heat shock protein antibody levels in established hypertension. J. Hypertens. 2002, 20, 1815–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpano, F.; Giacani, E.; Moro, D.; Gurgoglione, G.; De Simone, S. Heat shock protein (HSP) and its correlation to cocaine-related death: A systematic review. Clin. Ter. 2024, 175 (Suppl. 1), 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishigami, A.; Kubo, S.; Gotohda, T.; Tokunaga, I. The application of immunohistochemical findings in the diagnosis in methamphetamine-related death-two forensic autopsy cases. J. Med. Investig. 2003, 50, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Doberentz, E.; Genneper, L.; Wagner, R.; Madea, B. Expression times for hsp27 and hsp70 as an indicator of thermal stress during death due to fire. Int. J. Legal Med. 2017, 131, 1707–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wegner, A.; Doberentz, E.; Madea, B. Death in the sauna-vitality markers for heat exposure. Int. J. Legal Med. 2021, 135, 903–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodyear, J.E. Heat hyperpyrexia in an infant (a case report). Med. Sci. Law. 1979, 19, 208–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, T.C.; Sinniah, R.; Pakiam, J.E. Acute heat stroke deaths. Pathology 1981, 13, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parnell, C.J.; Restall, J. Heat-stroke: A fatal case. Arch. Emerg. Med. 1986, 3, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central][Green Version]

- Sherman, R.; Copes, R.; Stewart, R.K.; Dowling, G.; Guidotti, T.L. Occupational death due to heat stroke: Report of two cases. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1989, 140, 1057–1058. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ohshima, T.; Maeda, H.; Takayasu, T.; Fujioka, Y.; Nakaya, T. An autopsy case of infant death due to heat stroke. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 1992, 13, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, B.L.; Ishida, K.; Fujita, M.Q.; Maeda, H. Infant death presumably due to exertional self-overheating in bed: An autopsy case of suspected child abuse. Nihon Hoigaku Zasshi 1998, 52, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nadesan, K.; Chan, S.P.; Wong, C.M. Sudden death during jungle trekking: A case of heat stroke. Malays. J. Pathol. 1998, 20, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ng’walali, P.M.; Kibayashi, K.; Yonemitsu, K.; Ohtsu, Y.; Tsunenari, S. Death as a result of heat stroke in a vehicle: An adult case in winter confirmed with reconstruction and animal experiments. J. Clin. Forensic Med. 1998, 5, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, H.; Gilbert, J.; James, R.; Byard, R.W. An analysis of factors contributing to a series of deaths caused by exposure to high environmental temperatures. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2001, 22, 196–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krous, H.F.; Nadeau, J.M.; Fukumoto, R.I.; Blackbourne, B.D.; Byard, R.W. Environmental hyperthermic infant and early childhood death: Circumstances, pathologic changes, and manner of death. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2001, 22, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuliar, Y.; Savourey, G.; Besnard, Y.; Launey, J.C. Diagnosis of heat stroke in forensic medicine. Contribution of thermophysiology. Forensic Sci. Int. 2001, 124, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rav-Acha, M.; Hadad, E.; Epstein, Y.; Heled, Y.; Moran, D.S. Fatal exertional heat stroke: A case series. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2004, 328, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fineschi, V.; D’Errico, S.; Neri, M.; Panarese, F.; Ricci, P.A.; Turillazzi, E. Heat stroke in an incubator: An immunohistochemical study in a fatal case. Int. J. Legal Med. 2005, 119, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byard, R.W.; Riches, K.J. Dehydration and heat-related death: Sweat lodge syndrome. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2005, 26, 236–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, L.; Liu, L.; Jia, D.; Zhang, X.; Fowler, D.R.; Xu, X. Heat stroke deaths caused by electric blankets: Case report and review of the literature. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2006, 27, 324–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roccatto, L.; Modenese, A.; Occhionero, V.; Barbieri, A.; Serra, D.; Miani, E.; Gobba, F. Colpo di calore in ambito lavorativo: Descrizione di un caso con esito fatale [Heat stroke in the workplace: Description of a case with fatal outcome]. Med. Lav. 2010, 101, 446–452. (In Italian) [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gómez Ramos, M.J.; Miguel González Valverde, F.; Sánchez Álvarez, C.; Ortin Katnich, L.; Pastor Quirante, F. Fatal heat stroke in a schizophrenic patient. Case Rep. Crit. Care 2012, 2012, 924328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alunni, V.; Crenesse, D.; Piercecchi-Marti, M.D.; Gaillard, Y.; Quatrehomme, G. Fatal heat stroke in a child entrapped in a confined space. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2016, 34, 139–144, Erratum in J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2016, 38, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adato, B.; Dubnov-Raz, G.; Gips, H.; Heled, Y.; Epstein, Y. Fatal heat stroke in children found in parked cars: Autopsy findings. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2016, 175, 1249–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadesan, K.; Kumari, C.; Afiq, M. Dancing to death: A case of heat stroke. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2017, 50, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fais, P.; Pascali, J.P.; Mazzotti, M.C.; Viel, G.; Palazzo, C.; Cecchetto, G.; Montisci, M.; Pelotti, S. Possible fatal hyperthermia involving drug abuse in a vehicle: Case series. Forensic Sci. Int. 2018, 292, e20–e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazille, C.; Megarbane, B.; Bensimhon, D.; Lavergne-Slove, A.; Baglin, A.C.; Loirat, P.; Woimant, F.; Mikol, J.; Gray, F. Brain Damage After Heat Stroke. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2005, 64, 970–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, K.G. Heat-Related Deaths. J. Insur. Med. 2002, 34, 114–119. [Google Scholar]

- National Programme on Climate Change and Human Health; Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Autopsy Findings in Heat Related Deaths. 2024. Available online: https://ncdc.mohfw.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Autopsy-Findings-in-Heat-Related-Deaths_March24_NPCCHH.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- Goto, H.; Kinoshita, M.; Oshima, N. Heatstroke-induced acute kidney injury and the innate immune system. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1250457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).