Abstract

This study examines Panama’s 2023 mining restrictions to illuminate persistent legitimacy crises in extractive governance. Employing a qualitative case study, it draws on 25 semi-structured interviews with government officials, industry representatives, Indigenous leaders, local communities, mining critics and other civil society actors, alongside policy and document analysis. Findings suggest that legitimacy reconstruction relies on four interdependent conditions: procedural justice, institutional trust, epistemic legitimacy, and relational governance. Stakeholders consistently emphasized transparency, capacity building, and inclusive engagement as essential for future mining activity, underscoring that technical standards alone are insufficient without credible institutions. Building on—but extending beyond—frameworks such as Social License to Operate (SLO) and Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC), this paper offers Social Legitimacy for Mining (SLM) as a provisional, co-produced framework. Developed through literature synthesis and refined by diverse stakeholder perspectives, SLM is applied in Panama as an illustrative proof of concept that may inform further research and practice, while recognizing the need for additional adaptation across jurisdictions.

1. Introduction

The future of mining governance is no longer defined solely by economic performance or legal compliance. Its viability increasingly depends on ensuring procedural justice (procedural justice refers to the perceived fairness, transparency, and inclusivity of decision-making processes, especially as experienced by stakeholders involved in governance arrangements [,]), and institutional credibility to sustain public trust, especially in contested scenarios amid rising environmental and social pressures []. With growing global demands for a just energy transition and environmental sustainability, resource-rich countries face heightened scrutiny over how extractive projects align with diverse interests, knowledge systems, and evolving norms of legitimacy [,].

Across Latin America—and particularly in Panama—mining has long been characterized by institutional fragility, shifting political priorities, and limited citizen participation. For decades, the sector remained small and fragmented, constrained by weak regulation, inconsistent policy continuity, and public skepticism toward extractive development [,]. The commissioning of Cobre Panama (Cobre Panamá is operated by Minera Panamá S.A., a subsidiary of First Quantum Minerals Ltd., a Canadian mining company.)—one of the largest open-pit copper mines in Latin America—became a turning point: it symbolized economic opportunity but, against a backdrop of low institutional trust, also triggered deep public opposition over opaque decision-making, environmental concerns and perceptions of unequal benefit distribution [,].

Tensions escalated sharply following the approval of Law 406 in October 2023, which renewed the mining contract for Cobre Panamá and provoked widespread social unrest and nationwide protests. In response, the Supreme Court of Panama later declared the law unconstitutional [], and the government subsequently enacted Law 407, prohibiting metallic mining concessions nationwide []. This reactive reversal exposed structural weaknesses in Panama’s governance system—fragile institutions, limited transparency, and eroded public trust—that transformed a sectoral dispute into a national legitimacy crisis with global resonance [,].

While frameworks such as the Social License to Operate (SLO) and Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) have advanced dialogue and rights recognition, they often fail to address systemic, multi-level legitimacy breakdowns where distrust extends beyond individual projects to the state itself [,]. The Panamanian case illustrates this shift: the question is no longer about obtaining consent for one mine, but about rebuilding confidence in both the industry and the institutions responsible for governing the sector.

This study positions Panama as a critical case for examining how mining legitimacy erodes and under what conditions it can be reconstructed. Based on 25 in-depth interviews with stakeholders who influence or are affected by mining operations (including critical voices), supplemented by document review and policy/legal analysis, the research pursues four aims:

- Diagnose the institutional, political, and social factors that produced Panama’s 2023 mining legitimacy crisis;

- Interpret how diverse stakeholders perceive fairness, accountability, and institutional credibility;

- Identify governance mechanisms and minimum conditions that could rebuild trust across extractive development in polarized scenarios;

- Propose the Social Legitimacy for Mining (SLM) framework as a multi-actor, governance-oriented model for restoring trust in post-crisis contexts.

Empirically, the paper amplifies stakeholder perspectives to explain the roots of Panama’s mining conflict. Conceptually, it advances SLM as a systemic alternative to project-level models such as SLO and FPIC. Practically, it identifies pathways for governments, industry, and civil society to align extractive governance with environmental stewardship, institutional credibility, and social justice.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Rethinking Legitimacy in Mining

Contemporary debates in mining governance recognize legitimacy and trust as distinct but interrelated foundations of effective resource management. Legitimacy reflects perceptions that authority is exercised appropriately and fairly, grounded in shared norms and values [,], whereas trust indicates expectations of competent, reliable, and equitable action [,]. Although intertwined, legitimacy may endure despite fragile trust, particularly in contexts marked by institutional weakness or historical conflict [], but the lack of trust erodes legitimacy.

Within mining, legitimacy and trust operate across two axes: institutional trust in regulatory systems and relational trust between firms and local communities. While companies often prioritize community-level trust-building, evidence shows that local approval cannot substitute for sector-wide legitimacy—illustrated by the closure of Cobre Panama despite project-level relationships [,].

Building on Suchman’s [] framework, legitimacy is understood as multidimensional, encompassing pragmatic (stakeholder self-interest), moral (ethical validity), cognitive (cultural comprehensibility), and increasingly, epistemic legitimacy—the recognition of diverse knowledge systems, particularly Indigenous and local epistemologies [,,]. Extractive projects often face challenges when failing to respect these dimensions. Hence, long-term legitimacy depends not only on legal compliance but also on transparent, inclusive governance that integrates plural knowledge and mediates competing expectations across local, national, and transnational arenas [,].

2.2. Governance, Good Governance, and Its Role in Legitimacy

Governance refers broadly to the mechanisms through which authority and accountability are structured, while good governance emphasizes transparency, inclusivity, responsiveness, and rule of law—all critical for legitimacy [,]. In mining, these ideals must be translated into practices that protect rights, ensure fairness, and build both institutional and relational trust. Research demonstrates that perceptions of procedural justice often outweigh material benefits in determining acceptance, while gaps between formal rules and weak enforcement foster conflict [,].

Achieving good governance requires both institutional strengthening and capacity development across state and non-state actors. Distinctions between capacity for development and capacity development [] highlight that this involves not only resource mobilization and technical expertise, but also the empowerment of stakeholders to participate meaningfully in decision-making. Where capacity is weak, processes are often perceived as unfair and exclusionary; where it is nurtured, legitimacy improves through more informed, participatory, and accountable governance []. Good governance therefore underpins both input legitimacy—the fairness and inclusivity of decisions—and output legitimacy—the justice and effectiveness of institutional outcomes.

2.3. Translating Good Governance into Mining Mechanisms

A variety of governance tools have emerged over the past two decades. These include global principles such as the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights []; binding regulatory standards such as the IFC Performance Standards []; and voluntary disclosure frameworks such as the Global Reporting Initiative []. While these instruments signal progress, their effectiveness is undermined by inconsistent enforcement and selective adoption, reducing them to symbolic or procedural exercises [,]. More recent initiatives, such as the ICMM’s commitment to “No Net Loss/Net Gain of Biodiversity” [], aspire to move beyond harm mitigation toward positive ecological legacies. Yet critical scholarship cautions that without strong domestic governance and institutional accountability, such measures risk becoming technocratic or reputational strategies [,]. Similarly, voluntary frameworks like IRMA explicitly map their standards to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). However, achieving SDG-aligned outcomes—justice, transparency, inclusive participation—ultimately depends on robust legal enforcement, credible multi-stakeholder engagement, and cross-sectoral collaboration [,].

Participatory mechanisms have also become central, with two examples particularly influential in the extractive scenario, facing significant limitations when operationalization remains weak or disconnected from context-specific governance realities [,]. They are as follows:

- The Social License to Operate (SLO) is an informal, dynamic form of community approval grounded in trust and engagement rather than legal compliance []. It has influenced ESG standards and corporate practice globally, but risks devolving into a narrow reputation management tool that overlooks structural power asymmetries and the role of state institutions [,].

- Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC), rooted in ILO Convention 169 and UNDRIP [], codifies Indigenous peoples’ right to consent to projects affecting their territories. While fundamental to Indigenous rights, FPIC has limitations in pluralistic contexts where it risks becoming a procedural box-checking exercise, insufficient to address inequities or incorporate non-Indigenous stakeholders [,].

Taken together, these experiences highlight that governance tools alone cannot secure legitimacy. Scholars emphasize that meaningful legitimacy emerges only when such frameworks are embedded in broader systems of capacity development, institutional strengthening, and inclusive governance capable of mediating competing claims across multiple scales [,].

2.4. Beyond Procedural Frameworks

Mining prohibitions in Latin America illustrate how legitimacy crises in extractive governance extend beyond procedural limitations to encompass normative, ethical, and epistemic dimensions [,]. Such measures carry institutional, financial, and reputational consequences for states and companies, underscoring how fragile legitimacy becomes when diverse knowledge systems and social demands are not adequately incorporated [,].

Plural governance forces—activism, Indigenous resistance, and faith-based advocacy—have been especially influential in reframing extractive debates around moral and social values. The Catholic Church, through initiatives such as Pastoral Minera, invokes principles of human dignity, justice, and stewardship, offering an ethical perspective to extractive debates, sometimes contrasting with state narratives and past industry negative impacts [,,]. These interventions highlight that extractive legitimacy is shaped not only by regulatory compliance but also by collective values, symbolic authority, and societal expectations.

Peru, Costa Rica, Guatemala, and El Salvador are examples where mining restrictions were catalyzed by community opposition, environmental activism, and contested consultation processes, demonstrating how governance breakdowns intersect with normative pressures to reshape extractive development [,,]. Notably, El Salvador’s pioneering 2017 prohibition on metal mining [] was reversed in 2024 [], reflecting ongoing tensions between environmental protection and economic imperatives. These cases underscore that legitimacy restoration cannot rely solely on procedural reforms but must also address deeper normative and epistemic dimensions.

2.5. Advancing Social Legitimacy for Mining

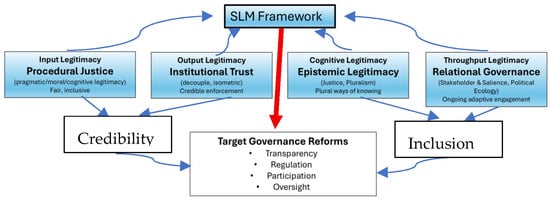

Addressing the limitations of procedural and governance-focused frameworks discussed above requires a more integrated and adaptive conceptual approach. This study draws on legitimacy theory complemented by institutional theory, in addition to stakeholder and stakeholder salience theories, and political ecology, to scaffold a multi-dimensional understanding of legitimacy in post-crisis extractive governance proposed by the Social Legitimacy for Mining (SLM) framework (as displayed in Figure 1 below).

Figure 1.

Theoretical Framework for Social Legitimacy for Mining (SLM). Arrows represent iterative feedback loops between legitimacy dimensions and governance reforms, emphasizing the interdependence of credibility and inclusion in sustaining legitimacy.

While legitimacy theory provides a normative and perceptual lens, institutional theory complements it by explaining how legitimacy becomes structurally embedded within organizational and regulatory systems. According to Meyer and Rowan [] and DiMaggio and Powell [], institutions are not only formal entities, but also social systems governed by taken-for-granted norms, rules, and cultural expectations that shape organizational behavior. These pressures—coercive, mimetic, and normative—help explain why mining governance often reproduces established practices even when they lose societal credibility. In this sense, Panama’s crisis reflects a moment of institutional decoupling, in which formal compliance and procedural legality (as seen in the approval of Law 406) diverged from public perceptions of fairness and legitimacy, exposing a broader gap between formal structures and societal expectations.

To operationalize this, the framework draws on Stakeholder Theory, which maps how a wide range of actors shape governance outcomes [,], and Stakeholder Salience Theory [,], which clarifies how differences in power, legitimacy, and urgency determine whose interests are advanced or marginalized. This lens makes it possible to move beyond static lists of “stakeholders” to offer a dynamic, comparative approach that recognizes how shifting actor salience and institutional contexts affect governance trajectories.

Finally, political ecology further integrates attention to historical legacies, material grievances, and the embeddedness of environmental values and justice claims in broader systems of governance [,]. It reminds us that extractive conflicts are not only institutional disputes but also struggles over knowledge, identity, and environmental meaning—especially acute following governance crises where postcolonial fault lines and structural inequalities exist either currently or historically.

Mapping SLM to Theories

SLM connects four dimensions to canonical theories and groups them into two meta-pillars—Credibility (procedural, institutional: can rules be trusted?) and Inclusion (epistemic, relational: whose knowledge and voice count?). The innovation is to render legitimacy as a system-level, auditable architecture with minimum conditions and sequencing rules that can be verified before scaling activity.

- Pillar I—Credibility

- Procedural justice → Input/throughput legitimacy; Suchman’s pragmatic–moral–cognitive lenses [].Focus: fair, transparent, reasons-giving procedures; predictable timelines; accessible remedy.Contribution: translates “fair process” into auditable practices (publication of technical reports, written reasons, grievance service levels).

- Institutional trust → Institutional theory: Meyer & Rowan (decoupling); DiMaggio & Powell (isomorphism) [,].Focus: alignment between formal rules and enforcement across electoral cycles.Contribution: explains why compliance without credibility fails; specifies continuity mechanisms (statutory oversight, budgeted mandates, independent review).

- Pillar II—Inclusion

- Epistemic legitimacy → Extension of cognitive legitimacy; epistemic justice/knowledge pluralism.Focus: recognition and co-production of scientific, Indigenous, and local knowledge in baselines, assessment, and monitoring.Contribution: makes “whose knowledge counts” measurable (co-produced baselines, joint monitoring, open data).

- Relational governance → Stakeholder & stakeholder-salience (power/legitimacy/urgency); polycentric governance; political ecology.Focus: how state, industry, Indigenous authorities, communities, NGOs, faith-based actors, and media co-produce acceptance across scales; how histories, material ecologies, and justice claims shape contestation.Contribution: embeds multi-actor oversight and participation ladders as durable interfaces; surfaces distributional/territorial justice dynamics (political ecology).

SLM shifts legitimacy from a company–community attribute to a multi-scalar, system-level property and expresses it as minimum, auditable conditions that can be sequenced and verified before expansion of extractive activity. It (i) integrates institutional theory to diagnose collapse (decoupling; isomorphic adoption without capacity) and guide reconstruction (continuity, enforcement, verification); (ii) adds an explicit epistemic dimension to legitimacy (plural knowledge authorities and co-production); and (iii) couples analysis to operational levers (indicators/oversight design, participation gradations).

The framework is used in this study to guide deductive codes (four SLM dimensions), allow inductive themes to emerge, and then tie policy recommendations to the SLM dimension(s) and empirical findings they reinforce.

2.6. Research Gap and Justification

Building on the preceding review, legitimacy remains a central yet problematic concept within extractive sector governance. While frameworks such as SLO and FPIC have advanced standards for participation and consent, both the literature and stakeholder interviews reveal critical shortcomings—especially when crises move beyond the project level and entail complex, multi-actor dynamics [,,]. The 2023 suspension of metallic mining in Panama exemplifies this, with localized grievances rapidly expanding into wider institutional and societal disruption.

Stakeholder interviews conducted for this research provided first-hand evidence of these limitations, highlighting gaps such as unclear responsibilities, insufficient integration of public and state actors, and challenges in creating responsive, inclusive engagement mechanisms. These insights extend the literature’s critique, emphasizing that addressing legitimacy requires approaches attuned to political, institutional, and societal complexity—rather than narrow project-level compliance [,,].

Empirical studies from post-crisis contexts underscore the necessity of embedding good governance principles and robust capacity-building across all levels [,]. Guided by these findings and informed by stakeholder perspectives, this study proposes the Social Legitimacy for Mining (SLM) as an evolving framework designed to analyze and respond to legitimacy deconstruction, contestation, and reconstruction throughout governance crises. Situated at the intersection of local, national, and transnational forces, the framework provides a context-responsive tool for examining how legitimacy can be dismantled and potentially rebuilt in the extractive sector. Its application to Panama is intended as a proof of concept rather than a definitive global model. The framework will require further testing and co-development with stakeholders in other jurisdictions to evaluate its broader applicability and adaptability to different governance contexts.

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design and Philosophical Orientation

This study employed a qualitative, single-case design [] to analyze legitimacy reconstruction in Panama’s mining governance. It is grounded in a critical realist ontology and an interpretivist–constructivist epistemology, recognizing that governance systems exist independently of perception and become knowable through socially constructed interpretations [,,].

The study integrates legitimacy theory [,] complemented by institutional theory [,], with political ecology [,], and stakeholder/salience theory [,,] to underpin the analytical design. This composite lens treats legitimacy as a multi-dimensional, institutionally embedded, and contested phenomenon shaped by power, norms, and knowledge systems across scales. The orientation is well-suited to Panama’s context, where extractive legitimacy is deeply contested and shaped by historical grievances, institutional narratives, and competing development visions []. To inform the development of the Social Legitimacy for Mining (SLM) framework, legitimacy was examined as a multi-scalar, plural, and dynamic process. The study examined the proposition that reconstruction depends less on technical compliance and more on institutional credibility, plural inclusion, and relational governance.

3.2. Case Selection, Boundaries, and Units of Analysis

Panama was selected as a single case study because it presents a rare convergence of environmental, geopolitical, and governance dynamics. As one of the few carbon-negative countries [], its exceptional biodiversity and strong public concern for environmental protection create a highly contested terrain for extractive industries. At the same time, Panama’s strategic position as a global transport hub, financial center, and visible actor in international debates heightens the stakes of its resource governance choices [,]. The recent mining restrictions have intensified these dynamics, illustrating how disputes over natural resource governance intersect with questions of legitimacy, institutional strength, and economic resilience []. By 2025, pressures to reconsider the prohibition—driven by economic contraction, arbitration claims, and global demand for transition minerals—further underscore Panama’s salience as a timely case for examining the future of mining governance [,].

A structural feature further shaping Panama’s governance context is its constitutional prohibition of consecutive presidential re-election. This rule ensures democratic alternation, but in practice it has meant that every electoral cycle brings a change in governing party, with power consistently alternating across political lines. While this system reinforces pluralism, it also entrenches short-termism, as each administration tends to prioritize five-year agendas over long-term policy coherence. The result is a stop–start policy environment in which new governments often dismantle or reverse the initiatives of their predecessors. This institutional dynamic has profound implications for extractive governance, where legitimacy depends on commitments that extend beyond electoral transitions and require stability across successive administrations.

Temporal and decision boundaries focus on the period spanning the approval of Law 406, the Supreme Court’s annulment, and the subsequent enactment of Law 407, which together define the post-crisis governance environment examined [,].

Units of Analysis

To capture the multi-scalar nature of legitimacy reconstruction, this study examines three interrelated units of analysis:

- Local communities—directly affected populations whose perspectives illuminate procedural justice and relational governance.

- Institutional actors—regulatory, judicial, and policy bodies central to institutional trust and credibility.

- National stakeholders—a diverse group including Indigenous leaders, business chambers, activists, academics, students, and legal/policy experts. These actors influence public discourse, generate competing knowledge claims, and shape epistemic legitimacy and broader societal acceptance.

Applying this multi-scalar lens informs the SLM framework by conceptualizing legitimacy as co-produced across local, institutional, and national levels. This approach enables analysis of how governance processes are dismantled and how they may be rebuilt through interconnected mechanisms of trust, justice, and inclusion.

3.3. Data Collection

Sources: primary materials comprised (i) semi-structured interviews and (ii) a document corpus; (iii) secondary indicators were compiled to contextualize the case.

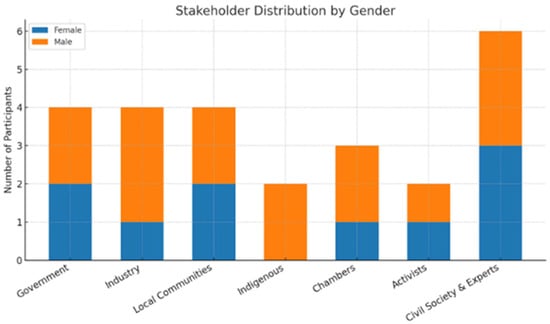

Interviews: 25 interviews were conducted in Panama, during July 2025, with diverse stakeholders—government (4), industry (4), local communities (4), Indigenous representatives (2), business chambers (3), activists (2), and civil society/experts (6) (as per Figure 2 below). No systematic differences by gender were observed in responses (see Appendix A for core themes responses by stakeholder group). Interviews were conducted in Spanish, in person, Zoom, or WhatsApp, typically 60 min, using a piloted guide aligned to the two overarching research questions (an interview guide with sample questions used during interviews is included as Appendix B).

Figure 2.

Stakeholder Distribution by Group and Gender.

Sampling and recruitment: stakeholder groups were identified through a synthesis of the literature on mining governance, the Panamanian context before and following the 2023 mining moratorium, and the researcher’s professional experience in the sector. A purposive, maximum-variation approach sought heterogeneity across power, legitimacy, and urgency [,]. Participants were identified through professional networks, snowballing, and outreach at public debates and conferences to include under-represented groups.

Saturation: the number of interviews was slightly larger than what is often cited as sufficient for reaching thematic saturation in qualitative research [], with the intention to capture cross-cutting differences in gender, position, and stance toward mining. A typology of stakeholders with its purpose is included as Appendix C. Thematic saturation was indicated by repeated patterns on transparency, institutional credibility, and inclusion across groups, occurring by interview 16, with the final interviews confirming rather than expanding the code frame [].

Ethics and data security: written or recorded informed consent was obtained prior to each interview. With permission, audio was recorded to a password-protected device, transferred the same day to an encrypted laptop, and deleted from the recorder. Transcripts were produced from Spanish audio and verified manually. Anonymization replaced names, organizations, and identifying references with pseudonyms or generalized descriptors; each transcript received a unique alphanumeric code. All materials (audio, transcripts, consent forms, field notes) were stored in password-protected folders under approved ethics protocols.

Document corpus: a structured corpus covering January 2023–August 2025 was compiled, including: (i) primary legal/policy texts (laws, contracts, court rulings, regulatory notices); (ii) government and multilateral reports; (iii) industry and civil-society materials (company disclosures, chamber statements, protest communiqués); and (iv) national/international media. Inclusion criteria were direct relevance to governance decisions around Laws 406/407, source diversity (state/industry/civil society/international), authenticity, and clear provenance.

Secondary indicators: publicly available macro-fiscal and sectoral indicators (e.g., GDP, bank reports, arbitration filings) from official statistics and multilateral databases were compiled to situate the case context.

Interview focus: questions examined (1) why Panama’s mining restrictions emerged, and (2) conditions under which mining could achieve broader societal acceptance. The inquiries explore perceptions of legitimacy, procedural fairness, trust, knowledge validation, relational experiences, power dynamics, and historical grievances. To reduce framing bias, participants were told that articulating a future without mining was as valid as supporting responsible mining; they were also invited to reflect on national and global implications. Illustrative quotations are provided in Appendix D.

3.4. Data Analysis

Analytical framework: analysis drew on a composite qualitative framework integrating legitimacy theory (procedural; pragmatic/moral; cognitive/epistemic dimensions), institutional theory (decoupling; coercive/mimetic/normative pressures), and political ecology (power, distributional conflict, environmental meanings). A resource-governance lens was operationalized via Stakeholder/Salience Theory (power, legitimacy, urgency). This framework informed construct definition, code development, and interpretation.

Corpus preparation and workflow: interview transcripts were anonymized. Spanish summaries translated into English and reflexive field notes were imported into NVivo 15 using a structured file-naming convention.

Hybrid thematic strategy: a hybrid thematic approach combined deductive and inductive logics.

- Deductive coding used sensitizing concepts from the proposed SLM framework—procedural justice, institutional trust, epistemic legitimacy, relational governance—and institutional constructs (decoupling; coercive/mimetic/normative pressures).

- Inductive coding captured emergent themes, including social-movement dynamics, perceived corruption, misinformation, environmental concerns, and distributional fairness.

Coding procedure and aggregation: analysis began with open/descriptive codes (e.g., trust in institutions, transparency, legal uncertainty, environmental concerns, benefit distribution). Codes were iteratively organized into axial categories (e.g., institutional trust, governance quality, legitimacy crises) and then mapped to higher-order constructs from the analytical framework to link participant accounts to theory-informed insights. A codebook excerpt is provided in Appendix E.

Role of documents and secondary indicators: documents and indicators were used to refine code definitions, conduct convergence/divergence checks with interview narratives, and support light process-tracing of key events (approval of Law 406 → protests → annulment → Law 407→ Considerations to reopen the copper mine). Where interview claims conflicted with documentary evidence, interpretive memos recorded the adjudication rationale; for example, some participants stated that ‘mining is prohibited in Panama,’ whereas the legal texts show the prohibition pertains to the granting/renewal of metallic mining concessions under Law 407—not to mining per se. A cross-case comparative matrix of stakeholder-group perspectives (Appendix A) was compiled to conduct convergence/divergence checks across groups and to map themes to SLM dimensions and institutional mechanisms.

Rigor and quality criteria: credibility and dependability were enhanced through memoing, matrix queries, and code–recode checks; triangulation across interviews, documents, and indicators; and a transparent audit trail (confirmability). Generative-AI tools were used only to assist with theme clustering and language refinement; all coding and interpretive judgments were made by the researcher.

Interpretive lens (salience): Stakeholder Salience Theory functioned as an interpretive lens—not a coding scheme—to compare actor positions across datasets. Industry actors frequently emphasized urgency (economic contraction, arbitration risk); communities and Indigenous leaders emphasized legitimacy (rights, participation, fairness); government actors spoke from positions of power yet were often perceived as lacking legitimacy. Misalignments between power and legitimacy, and the sidelining of urgent claims, help explain crisis dynamics and motivate the need for a systemic framework such as SLM.

3.5. Reflexivity and Limitations

The author’s background in mining governance and fluency in both Spanish and English enabled privileged access to diverse perspectives but also required heightened reflexivity to minimize potential bias []. To uphold rigor throughout the research process, a reflexive journal was maintained, the researcher’s professional background was transparently disclosed to all respondents, and interview questions were deliberately designed to be neutral and open-ended. Spanish-language interviews, transcripts, and any translations were carefully checked for accuracy. Research credibility was further strengthened through member checking, peer debriefing, triangulation of interview, document, and media data, and a fully documented audit trail of analytic decisions.

Despite purposeful and snowball sampling to maximize diversity, it is acknowledged that some highly marginalized or dissenting voices may not be fully represented, and elite access was at times constrained by political sensitivity. As with qualitative research generally, the findings are context-specific and not intended for statistical generalization. All steps were taken to ensure analytic transparency, methodological integrity, and critical self-awareness throughout the study.

4. Results

To move beyond description, the findings were interpreted through four structural dynamics of Panama’s extractive sector: (1) institutional decoupling (legality vs. perceived fairness), (2) isomorphic pressures (adoption without enforcement), (3) multiscalar legitimacy gaps (project consent vs. national credibility), and (4) temporal politics (five-year cycles vs. long-horizon investments). Results are presented by the four SLM dimensions—procedural justice, institutional trust, epistemic legitimacy, and relational governance (Section 4.1, Section 4.2, Section 4.3 and Section 4.4)—followed by a cross-cutting insight (Section 4.5). Inductive themes raised during interviews are integrated throughout. Together, the analysis explains how the 25 stakeholders understood the 2023 legitimacy collapse and the conditions they consider necessary for reconstruction.

4.1. Procedural Justice: Transparency, Accountability, and Institutional Weakness

In total, 68% of the participants directly linked the 2023 mining crisis to fragile procedures and weak institutional capacity. Government respondents acknowledged gaps in regulation and oversight, while civil society, activists, and Indigenous representatives emphasized corruption, lack of accountability and the volatility of Panama’s five-year political cycles, as one business leader noted: “In an ideal world, mining could be done responsibly. But Panama needs stronger institutions and clear long-term policies, not just five-year political cycles” (Interview 01).

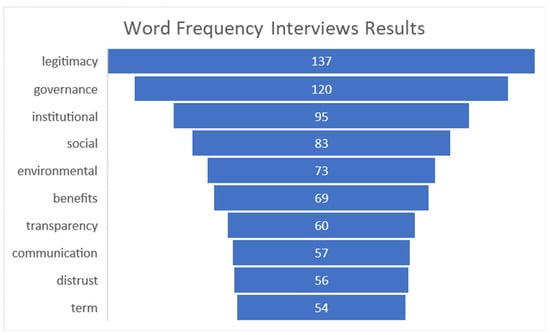

Transparency emerged as a near-universal concern (23/25; 92%). Participants described limited access to contracts, EIAs, and revenue data as creating a vacuum filled by misinformation and fear. This emphasis is reflected in term frequencies—transparency (60), communication (57), distrust (56)—as shown in Figure 3 below. As one community leader explained: “If there is no transparency, people imagine the worst. Information must be shared clearly and early” (Interview 04).

Figure 3.

Top 10 most cited words in the interviews.

Interpretive note: Decoupling & development risk. The prevalence of transparency/oversight concerns evidence decoupling between formal legality and perceived fairness. This elevates policy risk, raises the cost of capital, and favors short-cycle/speculative plays—an unfavorable mix for long-lived copper assets. Absent publicly legible procedures (reasons-giving, predictable timelines, enforceable remedies), approvals are unlikely to yield durable legitimacy or patient capital.

4.2. Trust and Institutional Credibility

Distrust in state institutions was the most pervasive finding (24/25; 96%), including among respondents broadly supportive of mining. Industry and business-chamber representatives acknowledged that weak enforcement and broken promises eroded credibility. Past experiences of limited consultation and unmet commitments were repeatedly cited as reasons communities doubt that future agreements would be honored: “The government has no credibility. People don’t believe in its ability to audit mining operations or enforce environmental protections” (Interview 13).

Ten participants (40%) pointed to the IDB-supported mining reform initiative [] as emblematic of governance fragility—a promising model that failed to consolidate, reinforcing skepticism about reform continuity. The salience of this theme is reinforced by the prominence of legitimacy (137 mentions), governance (120), and institutional (95) in the interviews (as per Figure 3).

An area of divergence concerns the time horizon to achieve the majority in social acceptance of mining. Some younger stakeholders expressed optimism that, with sustained public education and generational political renewal, mining could be reconsidered within 5–10 years. Industry actors similarly argued that institutional reform and visible benefits could help rebuild trust in the near term, with a more ambitious timeline aspiration. By contrast, pragmatic voices and activist groups contended that legitimacy, once broken, is extremely difficult—if not impossible—to restore (Interviews 24, 25). From their perspective, acceptance is either unattainable or would require profound cultural and institutional transformations extending over several decades.

Interpretive note: Credibility as a binding constraint. Near-universal distrust indicates credibility as the binding constraint on any sector restart. Developmentally, this steers Panama toward stop–start cycles (contracting → contestation → reversal), depressing reinvestment and complicating fiscal planning. It also clarifies why SLO/FPIC signals—valuable locally—did not translate into national-level acceptance.

4.3. Epistemic Legitimacy: Divergent Knowledge Claims and Environmental Concerns

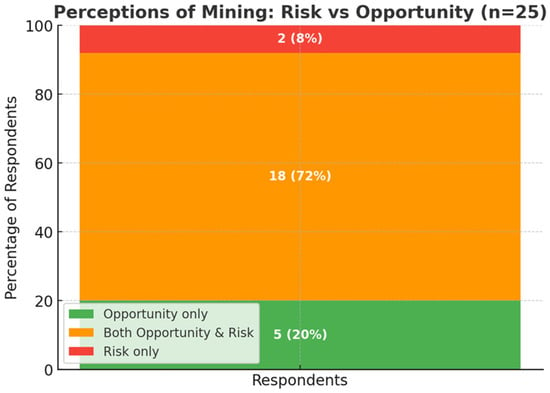

Stakeholders diverged in assessing mining’s risks and opportunities (see Figure 4 below). A total of 20% acknowledged potential opportunities, while 8% framed mining exclusively as risky, and 72% simultaneously identified mining as a source of opportunities and risks.

Figure 4.

Perceptions of Mining: Risks vs. Opportunity.

Risks were stressed by activists, Indigenous leaders, and environmental experts, who highlighted biodiversity loss, water contamination, and tailings dam safety under Panama’s tropical climate. One activist argued: “Mining is necessary, but I aspire to a Panama that works with nature and leaves behind the destructive extractives model” (Interview 25). These findings resonate with Montoya’s [] analysis, which shows that conflicts over extractives are not only material but also epistemic, rooted in struggles over whose knowledge is recognized as legitimate in governance processes.

Opportunities were emphasized most often by government, industry, and chambers of business, portraying mining as a multisectoral driver comparable to the Panama Canal, particularly in relation to employment, fiscal revenues, and economic diversification. One stakeholder stated, “Mining needs to be seen as the multisectoral driver that it is, not only as an extractive business” (Interview 05). Such divergent framings of risk and opportunity mirror broader regional patterns in which epistemic legitimacy becomes central to contested mining governance [,].

Interpretive note: Knowledge pluralism is not a communications deficit but a governance challenge. Without co-produced baselines and joint monitoring, contestation persists and transaction costs mount, further disincentivizing long-term investment.

4.4. Relational Governance: Intermediaries, Inclusion, and Plural Voices

A total of 14 participants (56%) explicitly identified the Catholic Church, NGOs, or media as more credible than government institutions in shaping public opinion: “When the Church spoke, people listened; when the ministry spoke, they doubted.” (Interview 19) The Church was highlighted across stakeholder categories as both mediator and moral authority, framing mining as an issue of justice, dignity, and stewardship of creation.

In total, 18/25 (72%) emphasized inclusive engagement beyond symbolic consultation—capacity building was called for both state regulators and communities (19/25; 76%), while government/industry framed participation as consultation and communication, civil society stressed substantive engagement (education, informed debate), and activist/Indigenous perspectives called for pluralistic inclusion, citizen decision authority, and recognition of alternative worldviews.

Interpretive note: Distributed legitimacy & institutional redesign. Because non-state actors command higher trust, legitimacy is distributed. Progress therefore hinges on statutory, multi-actor oversight, not corporate outreach alone. Project-level engagement cannot substitute for institutional reform at the national scale.

4.5. Cross-Cutting Insight

Across dimensions, respondents stressed that legitimacy cannot be restored through technical fixes or isolated reforms, identifying transparency, institutional credibility, plural knowledge, or inclusive governance as essential preconditions for any resumption of mining. An additional layer is Panama’s considerable mineral potential. According to the Panamanian Chamber of Mining [], the country hosts a diverse portfolio of metallic and non-metallic resources that could support long-term development if managed responsibly. Geological research further confirms this potential []. Such evidence underscores that the debate is not about resources, but the governance conditions under which their extraction might be deemed socially legitimate.

Long-term legitimacy requires not just technical standards but resilient and independent institutions, as mentioned in interviews recommending a depoliticized mining authority. While Panama could leverage selective, highly governed mining of critical materials, provided robust legitimacy conditions are met, it could also aim to diversify its economic base, reducing vulnerability to commodity cycles and governance shocks.

Interpretive note: Development trajectory. Absent recoupling of legality with perceived fairness—via transparency, independent verification, and participation that survives electoral turnover—the system tilts toward volatility (higher risk premia, delayed foreign direct investment, short-term revenues). Meeting these minimum conditions is the prerequisite for any growth path that includes mining.

5. Discussion

Panama’s 2023 mining restrictions were not a contractual anomaly but the culmination of multi-layered legitimacy crises. These patterns echo wider Latin American dynamics where extractives tip into conflict when weak institutions, corruption perceptions, and environmental concerns converge [,,]. Framed by legitimacy and institutional theory, the case shows why technical compliance is insufficient, institutional trust is indispensable, and legitimacy is distributed across plural authorities rather than monopolized by the state or industry. The absence of deep governance reforms suggests Panama will face protracted instability in attracting long-term capital. Strengthened institutions and transparency are prerequisites for sustainable growth in or beyond the extractive sector.

5.1. Legitimacy Beyond Technical Compliance

Transparency and procedural weakness emerged as central themes. Compliance with formal contracts or environmental approvals was insufficient; what mattered was whether processes were perceived as transparent, inclusive, and trustworthy. This aligns with Suchman’s [] typology: pragmatic legitimacy faltered as benefits were seen as unequally distributed; moral legitimacy collapsed amid corruption perceptions; and cognitive legitimacy weakened as institutional weakness enabled misinformation and amplified environmental concerns. One interviewee noted: “Mining was not banned because of geology or economics, but because the state lost legitimacy—people no longer trusted the process. Without institutions that inspire confidence, no contract will ever be seen as acceptable.” (Interview 08).

Consistent with governance scholarship, legal procedure alone cannot secure acceptance when trust and fairness are absent [,]. In Panama, legitimacy deficits persisted even where technical or legal benchmarks were met.

Compliance needs to be visible and verifiable to the public. In practice, that means publishing contracts and key environmental documents in an accessible format, providing clear written reasons for major decisions, setting predictable timelines, and offering reliable ways to raise and resolve complaints. These measures directly reinforce SLM’s procedural justice and institutional trust dimensions and respond to the patterns identified in the results (transparency gaps, weak reasons-giving, and inconsistent timelines). Without these basic guarantees of transparency and fairness, formal approvals will not translate into durable acceptance. {SLM: Procedural justice; Institutional trust|Findings: Section 4.1 and Section 4.2.}

5.2. Trust, Institutions, and the Reconstruction of Legitimacy

Distrust in state institutions was nearly universal (96% of participants), cutting across supportive and critical stakeholders. It is interpreted as a decisive barrier to rebuilding legitimacy and a structural weakness undermining any reform, resonating with Holmes [], who shows that corporate environmental policy is shaped not only by internal choices but by external institutional pressures and stakeholder expectations. In the Panamanian context, where 68% of participants explicitly linked the 2023 mining restrictions to fragile institutions, short-termism, and regulatory weakness, these insights indicate that institutional strengthening is a legitimacy-building process, not merely a technical fix.

Institutional distrust also clarifies why existing frameworks like SLO and FPIC fall short in post-crisis contexts. As the Results highlighted, respondents did not call for new technical standards, but for durable institutions capable of credible enforcement. SLO’s company-centric approach [] and FPIC’s legal scope [] are necessary but insufficient; both require integration within broader governance reforms to rebuild institutional trust. “Institutional weakness opened the door for disinformation and extremist narratives. To restore legitimacy, Panama needs stronger institutions, effective communication, and long-term coherent policies that integrate government and industry” (Interview 02).

Credibility comes first. Reforms should prioritize institutions that endure across elections—for example, an independent oversight body established in law, protected budgets for monitoring, and rules that do not lapse with changes in government. By anchoring continuity and enforcement, these steps reduce policy risk and make future sector decisions more believable to citizens and investors. These measures directly strengthen SLM’s institutional trust (and, by stabilizing due process, procedural justice) and address the credibility constraints identified in the results. {SLM: Institutional trust; Procedural justice|Findings: Section 4.2, Section 4.1.}

5.3. Plural Voices and Uneven Influence

A total of 56% of stakeholders named the Catholic Church, NGOs, or media as more credible and influential actors, indicating that legitimacy in Panama is relational and distributed across non-state actors who command higher public trust. Interpreted theoretically, this underscores the importance of epistemic pluralism in governance: legitimacy is co-produced through overlapping authorities, not delivered solely by state or corporate actors [,,]. This interview (16) called for recognition and inclusion of multiple knowledge systems: “Mining could only return if our communities are part of the decisions, with real benefits and respect for our rights—otherwise, it will always be rejected”.

The Catholic Church exemplifies the multifaceted role of faith-based actors in mining governance. In Panama, the Church has often adopted a critical stance toward mining [,,], aligning with environmental and social movements in defense of creation (in Catholic social teaching, “creation” refers to the natural environment and all living beings as part of God’s creation; the phrase “defense of creation” is commonly used by the Church to frame ecological protection as both a moral and spiritual responsibility []) [,]. Elsewhere in Latin America, however, the Church has assumed a more collaborative or reform-oriented posture, engaging with industry and communities to encourage more responsible practices. Bryant [] highlights initiatives, including those of the Development Partner Institute that explore partnerships between faith-based organizations and mining companies as “unexpected collaborations for prosperity.” An example from 2025, at the Universidad Nacional de Piura, in Peru, Father Henry Yoan David, Director of the Pastoral Minera in the Archdiocese of Antioquia, emphasized that the Church’s response to mining challenges is not outright rejection but the promotion of just and responsible mining as a pathway for reform [].

An additional illustration of plural voices is found in a 2024 letter to the President of Panama by Indigenous groups. The letter, signed by four Presidents and one Cacique from Indigenous territories, stated: “…we would be willing to promote the interest of mining companies, and others to associate (joint venture) with us to propose the development of already identified mining projects within our Comarca, provided that we have a reasonable equity participation and that the due process of consultation is respected” (Indigenous Territories of Panama, personal communication, 2025). This document reveals an underexplored dimension: while many Indigenous and activist perspectives may oppose resource extraction outright, other Indigenous authorities express conditional openness to mining under frameworks of equity, partnership, and consultation [,]. Such diversity within Indigenous governance underscores the complexity of legitimacy and the uneven distribution of influence across stakeholder groups.

Because legitimacy is distributed, inclusion must be formal, not symbolic. Practical steps include multi-actor oversight, participatory monitoring that shares data openly, and sustained capacity building for regulators, communities, and Indigenous organizations. Co-producing baselines and monitoring local communities and/Indigenous knowledge lowers conflict and improves the quality of decisions. These measures operationalize SLM’s relational governance and epistemic legitimacy dimensions (and support procedural justice by making participation consequential) and directly address the trust asymmetries and knowledge disputes identified in the results. {SLM: Relational governance; Epistemic legitimacy; (supports) Procedural justice|Findings: Section 4.4, Section 4.3.}

5.4. Global Frameworks, Local Skepticism

As shown in Figure 4, respondents often framed mining simultaneously as opportunity and risk, with “environmental” and “benefits” ranking among the most cited terms (Figure 3). This duality shaped how international frameworks such as ICMM’s “Nature Positive” model are perceived. While these initiatives articulate a restorative vision for mining, stakeholders in Panama viewed them with skepticism, questioning whether voluntary frameworks could succeed in a context of weak enforcement and entrenched mistrust: “People want a voice, not a checkbox consultation. Real inclusion means being part of decisions, not just informed after” (Interview 17).

This skepticism resonates with critical scholarship on “no net loss” and “nature positive” strategies, which warns that such commitments can become technocratic or reputational exercises, obscuring power asymmetries and diluting accountability []. The results suggest that unless global frameworks are embedded in robust, context-specific governance systems—backed by independent verification and participatory oversight—they will lack legitimacy in Panama.

International standards only gain traction when embedded in domestic rules and checked by independent reviewers. A governance-first sequence is therefore advisable: establish minimum conditions (transparency, independent review, participation), show they work in practice, and only then consider selective approvals. This order rebuilds trust before scaling activity and makes global frameworks meaningful in context. These steps activate SLM’s procedural justice (transparent rules, reasons-giving), institutional trust (credible, election-resilient enforcement), and relational/epistemic dimensions (participation with co-produced knowledge and open data), directly addressing the gaps identified in the results. {SLM: Procedural justice; Institutional trust; Relational governance; Epistemic legitimacy|Findings: Section 4.1, Section 4.2, Section 4.3 and Section 4.4.}

5.5. Toward a Stakeholder-Informed Framework: Social Legitimacy for Mining (SLM)

Legitimacy in Panama’s mining sector cannot be rebuilt through cosmetic reforms, technical compliance, or external frameworks alone. Nearly all stakeholders emphasized that credible institutions, transparent processes, plural knowledge, and inclusive governance were essential preconditions for any resumption of mining. These insights form the foundation for the Social Legitimacy for Mining (SLM) framework.

Proposed as an extension to SLO and FPIC, the Social Legitimacy for Mining (SLM) framework is co-produced with stakeholders based on empirical insights from interviews, emphasizing a governance approach rooted in participatory legitimacy reconstruction. SLM reconceptualizes legitimacy as a systemic, multi-actor, and dynamic process across four interdependent dimensions: procedural justice, institutional credibility, epistemic pluralism, and relational governance. Unlike SLO and FPIC, which often operate at the project or legal level, SLM intends to respond to stakeholder experiences in Panama by situating legitimacy at multiple scales—local, institutional, and national—and by explicitly addressing governance breakdowns.

The Panamanian case also illustrates that external frameworks such as ICMM’s “nature positive” approach only gain traction when embedded in trusted, context-responsive governance. SLM proposes to address this gap by linking global normative aspirations to local legitimacy conditions, emphasizing independent verification, participatory monitoring, and recognition of Indigenous and community worldviews. In this way, SLM is not a replacement for SLO or FPIC but an integrative evolution, designed to make legitimacy resilient in volatile or post-crisis environments.

Table 1 synthesizes the comparative features of SLO, FPIC, and the proposed SLM framework. While it risks appearing aspirational, it is not intended as a fully operational model at this stage. Instead, it represents a conceptual architecture that can be tested and refined in practice.

Table 1.

Comparative Features of SLO, FPIC, and SLM (comparative analysis of frameworks: The Social License to Operate (SLO); Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC); and the proposed Social Legitimacy for Mining (SLM)).

Conceptually, SLM synthesizes insights from legitimacy theory, stakeholder theory, stakeholder salience, and political ecology, positioning legitimacy as a dynamic and rebuildable process. It does not assume full consensus or the resolution of all contestations; rather, its aim is to enhance the perceived fairness, inclusiveness, and credibility of governance, particularly in post-crisis contexts.

Distinctively, SLM:

- Frames legitimacy as ongoing and interactive, shaped through four dimensions: procedural justice, institutional trust, epistemic legitimacy, and relational governance.

- Emphasizes multi-scalar applicability, from local to national and global levels.

- Incorporates stakeholder salience to analyze how power, legitimacy, and urgency shift across crises [].

- Provides practical diagnostic tools to identify legitimacy breakdowns and chart pathways for restoration.

Table 2 outlines the theoretical anchors of SLM and illustrative lines of inquiry, showing how the framework can guide both scholarly analysis and policy practice.

Table 2.

Theoretical Framework Dimensions for Social Legitimacy for Mining (SLM).

By integrating these dimensions, the SLM framework proposes to offer a structured and adaptive lens for analyzing legitimacy in extractive governance. It intends to provide scholars and practitioners with a practical and conceptually robust approach for understanding, contesting, and reconstructing legitimacy—explicitly addressing systemic, multi-actor challenges that extend beyond project-level models.

5.6. Scope and Transferability

Panama’s experience is shaped by several distinctive factors: the prohibition of consecutive presidential terms and rapid policy turnover (small-state dynamics), the coexistence of state, church and Indigenous authorities (legal pluralism), and high political sensitivity around environmental stewardship. These features influence both the breakdown and reconstruction of legitimacy in mining governance.

While the SLM framework proposes generalizable principles for rebuilding legitimacy, certain elements—such as managing legal pluralism, navigating short electoral cycles, and engaging faith-based or traditional authorities as intermediaries—are especially prominent in Panama and may not directly apply to larger or more centralized jurisdictions.

- Transferable elements of SLM include:

- Procedural practices (reasons-giving, open data, participatory decision making)

- Institutional designs (credible and election-resilient oversight mechanisms)

- Epistemic strategies (co-produced baselines and transparent monitoring)

- SLM applied to Panama—context-specific aspects include:

- The dynamics of five-year electoral cycles and policy discontinuity

- The strong role of faith-based organizations and Indigenous authorities as trust intermediaries

In sum, SLM should be seen as a “portable logic” adaptable to new settings, but always requiring local adaptation—rather than a one-size-fits-all model.

6. Policy and Practice Implications

The collapse of mining legitimacy in Panama reflects institutional fragility, opacity, and widespread distrust. Stakeholders in this study emphasized that transparency, capacity building, and inclusive participation are essential for restoring confidence, indicating that superficial consultation or one-off corporate responsibility initiatives are unlikely to be effective in isolation. The following recommendations outline possible policy pathways for operationalizing SLM’s core dimensions in Panama, with illustrative implementation tools (phased plan and IAP2 (IAP2 is a global association established in 1990 that promotes the practice of inclusive, transparent, and effective decision-making processes by aligning public input with decision-making authority) adaptation) provided in Appendix F and Appendix G. Recommendations are linked to SLM dimensions and findings, and shown in curly brackets {} below.

- Institutionalize Binding Commitments: full implementation of Panama’s Escazú Agreement (The Escazú Agreement (2018) is a legally binding regional treaty for Latin America and the Caribbean that guarantees rights of access to environmental information, participation, and justice, and includes provisions to protect environmental defenders) obligations—ensuring timely information access, participatory decision-making, and effective grievance mechanisms—could address core transparency and accountability concerns identified by participants. {Procedural justice; Institutional trust—aligns with Section 4.1 and Section 4.2.}

- Integrate Measurable Standards in Regulation: while interviewees expressed skepticism toward voluntary initiatives, frameworks such as Towards Sustainable Mining (TSM) (Towards Sustainable Mining (TSM) is a performance-based sustainability program created by the Mining Association of Canada in 2004 []; it requires participating companies to measure and publicly report on environmental and social performance across areas such as tailings management, community engagement, and biodiversity, with external verification to ensure transparency) formally endorsed by the Panamanian Chamber of Mines, CAMIPA, and ICMM Performance Expectations [] provide reference points for responsible practice. Their integration into public regulation, alongside independent oversight, may enhance institutional credibility. {Institutional trust; Relational governance—Section 4.2 and Section 4.4.}

- Structure participation using IAP2-inspired gradations: to demonstrate progression from informing to collaboration and shared decisions, SLM incorporates participatory gradations inspired by the IAP2 Spectrum []. {Procedural justice; Relational governance; Epistemic legitimacy—Section 4.1, Section 4.3 and Section 4.4; Appendix G.}

- Build Capacity and Empower Stakeholders: long-term legitimacy is likely to require sustained investment in technical, legal, and monitoring skills for regulators, communities, Indigenous organizations, and civil society, to ensure meaningful participation and oversight. {Epistemic legitimacy; Relational governance—Section 4.3 and Section 4.4.}

- Foster Multi-Actor Oversight Structures: aligning with SLM’s emphasis on relational governance, multi-actor oversight entities can support joint monitoring, deliberation, and accountability, but should be shaped by ongoing stakeholder input to reflect diverse perspectives and needs. {Relational governance; Institutional trust—Section 4.2 and Section 4.4.}

- Create a Depoliticized Mining Authority: to address institutional fragility and restore credibility, stakeholders emphasized the need for an autonomous, professionalized body capable of regulating the mining sector at arm’s length from partisan politics. In collaboration with the previous government (2019—2024), the IDB proposed the establishment of such a depoliticized Mining Authority in Panama to ensure consistency, technical rigor, and accountability in governance. Anchoring this authority in law—with transparent appointment processes, independent funding mechanisms, and structured stakeholder representation—could mitigate risks of political capture, strengthen institutional trust, and provide a stable foundation for long-term sector governance []. {Institutional trust; Procedural justice—Section 4.2, Section 4.1.}

Note on implementation: successful operationalization of SLM will require approaches tailored to local institutional capacities and stakeholder preferences. The IAP2 Spectrum is offered as a conceptual aid for visualizing incremental shifts from transactional to participatory engagement, not as a one-size-fits-all roadmap. In summary, while these recommendations offer practical entry points for strengthening legitimacy and trust, reforms should remain adaptive and evidence-led, building toward credible, collaborative, and context-appropriate institutions.

7. Conclusions

7.1. The Future of Mining and the Mining of the Future

Panama’s mining restrictions are more than a national controversy—they stand as a governance warning with lessons that extend far beyond its borders. The trajectory of extractive industries is increasingly shaped by the credibility of institutions, the inclusiveness of decision-making, and the trust built among stakeholders. In Panama, interviews underscored overwhelming demands for transparency, institutional credibility, and inclusive participation—not peripheral concerns, but central conditions for legitimacy.

Importantly, the consequences of weak governance extend beyond the extractive sector. The annulment of contracts and uncertainty around mining have eroded perceptions of investment security, contributed to sovereign credit downgrades, and increased the cost of government borrowing—evidence that governance failures reverberate across the entire economy, not just mining.

The Panama case advances sustainability debates by relocating legitimacy from a company–community attribute to a system property produced by public institutions and knowledge authorities, and durable across electoral cycles. It shows that “responsible mining” narratives are fragile without procedural justice, credible enforcement, and epistemic inclusion. For the energy transition, the implication is clear: mineral supply strategies must be coupled to institution-building that renders legality publicly legible, independently verifiable, and durable across political cycles.

Stakeholders worldwide are demanding that extractive projects move beyond a narrow focus on resource exploitation to become multisectoral development drivers aligned with long-term socio-economic and environmental aspirations. Ultimately, the future of mining in Panama—and other resource-rich countries alike—will not be determined by the value of ore bodies, but by the credibility of governance and the depth of social legitimacy.

7.2. Contribution and Way Forward

This research makes three contributions. Empirically, it amplifies diverse stakeholder voices, demonstrating why Panama’s mining legitimacy collapsed in 2023 and what conditions are needed for reconstruction. Conceptually, it proposes the Social Legitimacy for Mining (SLM) framework as a systemic, multi-actor alternative to project-based models like SLO and FPIC. Practically, it links findings to actionable pathways, illustrating how instruments like Escazú, TSM, ICMM, and the adapted IAP2 spectrum can be aligned within SLM to support reform. Together, these contributions highlight that legitimacy cannot be rebuilt through temporary fixes. It requires structural reforms, credible institutions, fair benefit-sharing, and long-term engagement, resilient to political and market volatility. Further research should test and refine SLM in different jurisdictions, evaluating its capacity to deliver measurable governance and social outcomes.

Funding

No external funding was received for this research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not require formal institutional ethics approval in Panama, as national regulations governing research ethics apply primarily to biomedical and health-related research []. Nonetheless, the research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided informed consent prior to interviews, were assured of confidentiality, and had the right to withdraw at any stage. Data was anonymized, securely stored, and used exclusively for academic purposes.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Summarized anonymized interview data, codebooks, and NVivo-generated tables are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. However, due to ethical considerations, the confidentiality and privacy of respondents were assured, and therefore, raw interview data provided by participants will be kept strictly confidential and cannot be shared.

Acknowledgments

This article is influenced by research undertaken for the author’s proposed Doctor of Business Administration (DBA) dissertation at Royal Roads University. The author gratefully acknowledges the insights of all interview participants who contributed their time and perspectives to this study. Special thanks are given to William Holmes and Stewart Redwood for generously reviewing the paper prior to submission. The author further wishes to recognize the inspiration of industry colleagues who embody integrity and commitment to responsible mining. In particular, Ana Juárez, President of Women in Mining Central America, and Stellamaris Tile, a Panamanian role model for women in mining, are acknowledged alongside the late David J. Hall and Brian Grant, who are remembered with gratitude. Together, they represent the many individuals whose example has shaped and encouraged this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CAMIPA | Cámara Minera de Panamá (Panamanian Chamber of Mining) |

| CoNEP | Consejo Nacional de la Empresa Privada (National Council of Private Enterprise, Panama) |

| ESG | Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| FPIC | Free, Prior and Informed Consent |

| GRI | Global Reporting Initiative |

| IAP2 | International Association for Public Participation |

| ICMM | International Council on Mining and Metals |

| IDB | Inter-American Development Bank |

| IFC | International Finance Corporation |

| IGF | Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals and Sustainable Development |

| ILO | International Labour Organization |

| IRMA | Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance |

| MAC | Mining Association of Canada |

| MP3 | MPEG Audio Layer-3 (digital audio format) |

| NGO(s) | Non-Governmental Organization(s) |

| NVivo | Qualitative Data Analysis Software (QSR International) |

| Portable Document Format | |

| SDG(s) | Sustainable Development Goal(s) |

| SLO | Social License to Operate |

| SLM | Social Legitimacy for Mining |

| TSM | Towards Sustainable Mining |

| UNDP | United Nations Development Programme |

| UNDRIP | United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples |

| UNSDG(s) | United Nations Sustainable Development Goal(s) |

Appendix A. Cross-Case Comparative Matrix—Themes Summary

This matrix summarizes the perspectives of different stakeholder groups and their perceptions of legitimacy, procedural fairness, trust, knowledge validation, relational experiences, power dynamics, and historical grievances.

| Stakeholder Type | Reasons for Ban (2023) | Governance & Trust Issues | Conditions for Acceptance | Vision of Development |

| Government/Political | Public discontent with corruption, rushed contract approval, political exhaustion | Weak institutions, lack of long-term planning, corruption | Clear rules, transparency, stronger oversight, depoliticized mining authority | Mining as part of national plan if well-governed |

| Lawyers/Legal Experts | Legal uncertainty, poor communication, weak oversight, contract rushed | Improvisation, unstable regulations, lack of legal clarity | Robust legal framework, standardized contracts, stronger institutions, transparency | Mining compared to Panama Canal—potential pride if benefits are shared |

| Civil Society/Communities | Government mistrust, unfair distribution, corruption, environmental fears, social media activism | Distrust of government, misinformation, politicization, weak communication | Fair distribution, transparency, stronger institutions, engagement, safeguards | Mining accepted only if benefits are tangible and fair |

| Technical Experts | Public ignorance, misinformation, weak/obsolete laws, opportunism, short-term politics | Corruption, weak oversight, lack of continuity, outdated constitution | Mining ‘done right’, education, governance reforms, long-term planning | Cultural/educational reform needed; responsible mining possible with rehabilitation |

| Activists | Distrust of government, betrayal of sovereignty, inequality, ecological concerns | State lacks credibility, weak institutions, poor transparency | Practically impossible under current governance; hypothetical net-positive mining | Alternatives to mining: biodiversity, logistics, services; leave minerals underground |

Appendix B. Interview Guide

(tailored to specific stakeholder groups) “Thank you for taking the time to speak with me today. I’m conducting research to explore whether or how trust and legitimacy can be rebuilt in Panama’s mining sector following the 2023 ban. I’m especially interested in your views on what responsible and legitimate mining would look like in the future, and how different actors should be involved. Your insights will help develop governance recommendations that reflect diverse stakeholder perspectives. I would like to hear your perspectives of: (1) why Panama’s mining restrictions emerged and (2) conditions under which mining could achieve broader societal acceptance. You are also welcome to articulate a future without mining if that is your aspiration, and if so, please reflect on national and global implications on such scenario. This interview is voluntary and confidential, and you’re free to skip any question or stop at any time. Do you have any questions before we begin?”

- Sample of Semi-Structured Interview Guide

Section 1: Background and Role

- Can you describe your current role or experience as it relates to the mining sector in Panama?

- How have you or your organization been involved—directly or indirectly—with mining issues, decisions, or policies in the country?

Section 2: Perspectives on the 2023 Mining Moratorium

- 3.

- What is your perspective on Panama’s 2023 national ban on metallic mining?

- 4.

- In your view, what were the main drivers or turning points that led to the prohibitions in place for mining? Are there specific events or concerns you consider decisive?

- 5.

- Do you believe this decision reflected a breakdown in public trust or legitimacy? Why or why not?

Section 3: Defining Legitimacy and Responsible Mining

- 6.

- What does “legitimate” mining governance mean to you? Can you offer an example?

- 7.

- In your opinion, what makes a mining project responsible or acceptable?

- 8.

- Do you think trust in mining governance can be restored in Panama? If so, what would it take? How would you know if legitimacy had been restored?

Section 4: Stakeholder Engagement, Inclusion, and Power

- 9.

- What forms of engagement or consultation do you consider meaningful? What would make engagement feel genuine rather than tokenistic?

- 10.

- Which actors or groups should be involved in decisions about mining, and why?

- 11.

- How should Indigenous Peoples and local communities be included in mining decisions to ensure their perspectives are meaningfully considered?

- 12.

- Have you observed any power imbalances or conflicts between stakeholder groups? How do these affect trust and legitimacy?

- 13.

- Do you think gender or other aspects of identity affect whose voices are heard in mining governance?

Section 5: Governance, Reform, and Institutional Trust

- 14.

- Do you think current governance structures are capable of rebuilding trust and legitimacy? Why or why not?

- 15.

- If mining were to resume in Panama, what specific governance reforms or institutional changes would you consider essential for restoring trust and legitimacy?

- 16.

- What changes would you like to see in how government or companies engage with society?

- 17.

- What role do transparency and accountability play in regaining public trust?

Section 6: Knowledge, Values, and Social Legitimacy for Mining (SLM)

- 18.

- Whose knowledge or perspectives do you think are most valued in mining decisions? Are there voices or knowledge systems that are often overlooked?

- 19.

- Do you think Panama needs a new way of thinking about how trust and legitimacy in mining are built and maintained? Why or why not?

- 20.

- Would you support an approach that brings in the voices of different sectors of society—not just communities near mining sites? What principles or values should guide such a framework?

Section 7: Final Reflections and Recommendations

- 21.

- Is there anything else you would like to add about mining, governance, or community engagement in Panama?

- 22.

- Are there any reports, individuals, or cases you recommend I review as part of this study?

- 23.

- Would you like to receive a summary of the study’s findings (See Appendix H: Plain-language Summary Example for Post-interview Feedback Process)? If so, what is your preferred method of contact (email, WhatsApp, etc.)?

Thank you again for your time and for sharing your perspective. Your input is extremely valuable.

Appendix C. Typology of Stakeholders and Purpose

| Category | Stakeholder Examples | Purpose |

| Diversity of Perspectives | Gender, age, cultural background, socio-economic position. | Capture varied experiences that shape views on legitimacy and governance. Efforts to include underrepresented voices. |

| Local Communities | Residents, suppliers and leaders in mining areas. | Capture lived experiences, concerns, and expectations of benefits or safeguards. |

| Indigenous Groups | Authorities representing Indigenous territories. | Explore rights claims, worldviews, and experiences with extractive industries. |

| Civil Society/NGOs | Environmental groups, activists, faith-based groups, labor unions. | Reflect wider debates on environment, social justice, and democratic accountability. |

| Industry | Mining executives, business chambers, sector associations. | Understand corporate priorities, economic interests, and governance expectations. |

| Academics/Legal Experts | Lawyers, scholars, and policy specialists. | Provide analysis of legal frameworks, constitutional issues, and legitimacy debates. |

| Government Actors | Past and present representatives (mining authorities, regulatory officials, legislators) | Capture perspectives on policy design, enforcement capacity, and institutional trust. |

Appendix D. List of Additional Notable Quotes from Interviewees in No Specific Order

| Quotes |

| “The government simply does not have the capacity or credibility to monitor a project of this size. People assumed corruption, and trust collapsed.” |

| “When no clear data is available, people imagine the worst. Fear spreads faster than facts.” |

| “Mining could transform Panama’s economy if managed transparently. It brings revenues and jobs that no other sector can match.” |