Abstract

Background/Objectives: Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) is a serious complication of antiresorptive and antiangiogenic drugs with no consensus on optimal treatment. This study aimed to evaluate the clinical outcomes of MRONJ patients managed at a tertiary referral center over a 15-year period. Methods: We conducted a retrospective cohort study of 130 patients diagnosed with MRONJ (per AAOMS criteria) at a single tertiary hospital between 2006 and 2021. Data on demographics, underlying disease, drug history, MRONJ stage, triggering events, and treatment (conservative vs. surgical) were collected from medical records. Treatment outcomes were categorized as complete resolution, stable disease, or progression. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to identify predictors of resolution. Results: Most patients (84.6%) had an underlying malignancy. The primary causative agents were zoledronic acid (47.7%) and denosumab (30.0%), the most frequent site was the mandible (66.2%), and the main trigger was dental extraction (59.2%). Crude resolution rates were 20.3% for conservative management versus 83.6% for surgical management. Treatment was stage-driven, with surgery common in advanced stages. At 12 months, 43.1% of all patients achieved complete resolution, and 52.3% remained stable. Multivariate analysis confirmed surgical treatment as the only independent predictor of complete resolution (OR = 20.1, 95% CI: 8.1–50). Conclusions: In this cohort, conservative care was generally sufficient for Stage I disease, while surgical intervention was the strongest predictor of healing and provided reliable outcomes for advanced MRONJ. These findings support an individualized, stage-appropriate treatment strategy.

1. Introduction

Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) is a serious and complex condition, primarily associated with the use of antiresorptive and antiangiogenic drugs. These medications are commonly prescribed for malignant diseases, osteoporosis, hypercalcemia, Paget’s disease, giant cell tumor of bone [1] and for the prevention of skeletal-related events. Recent epidemiological data indicate that MRONJ affects approximately 1–8% of cancer patients receiving high-dose intravenous bisphosphonates or denosumab, and less than 0.01% of osteoporotic patients treated with oral antiresorptives [2,3]. The condition predominantly affects women over the age of 60, reflecting the underlying demographics of osteoporosis and breast cancer. There are four main categories of patients considered at risk of Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw (MRONJ): (i) those on low-dose antiresorptive therapy for non-malignant conditions, (ii) those on long-term oral antiresorptive therapy or with concurrent glucocorticoid use, (iii) cancer patients receiving high-dose antiresorptive or anti-angiogenic drugs, and (iv) individuals with a prior history of MRONJ.

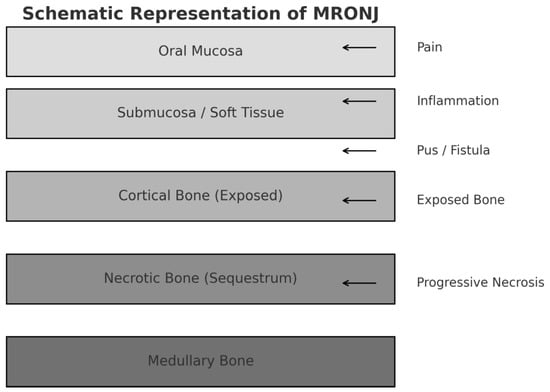

Since the first reported case of MRONJ in 2003 [4], extensive research has been conducted to better understand its pathogenesis and to develop effective treatment strategies. The main clinical features include pain in the affected necrotic bone, signs of local infection, paresthesia or hypoesthesia of the lower lip, tooth mobility, and foul odor (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of MRONJ showing the anatomical layers involved and the major associated clinical signs and symptoms.

Diagnosing MRONJ requires distinguishing it from other forms of osteonecrosis. The American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS) recently updated its definition in 2022 [3], outlining the following diagnostic criteria:

- Current or previous treatment with antiresorptive therapy, either alone or in combination with immunomodulators or antiangiogenic agents.

- Exposed bone or bone that can be probed through an intraoral or extraoral fistula in the maxillofacial region, persisting for more than eight weeks.

- No history of radiation therapy to the jaws or evidence of metastatic disease to the jaws.

AAOMS defined –then- bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws (BRONJ) on 2007 criteria [5] and updated subsequently on 2009 [6], 2014 [7] and 2022. The 2009 position paper introduced the staging and proposed strategies for management [6].

Despite two decades of research, the pathophysiology of MRONJ remains a topic of debate. One prominent theory involves the suppression of bone turnover, as antiresorptive agents like bisphosphonates (BPs) and denosumab (DMB) inhibit osteoclast formation, differentiation, and function through distinct mechanisms [8]. Infection is another proposed contributing factor, particularly in cases following tooth extraction, where pre-existing periapical disease is commonly observed [9]. Inhibition of angiogenesis may also play a role, particularly in patients with multiple myeloma who receive antiangiogenic agents in combination with steroids [10]. Additionally, immune dysfunction—either innate or acquired—has been implicated in MRONJ development, especially in the context of chemotherapy, corticosteroids, and immunosuppressive agents [11,12]. While early studies suggested a potential genetic predisposition [13], recent research has provided only limited support for this theory [14]. Collectively, these findings support the current understanding of MRONJ as a multifactorial disease [15].

The incidence of MRONJ is significantly lower in patients treated for osteoporosis than in those receiving treatment for malignancy. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ) in osteoporosis patients has an estimated incidence of 0.001% to 0.06% [16]. In contrast, among cancer patients treated with zoledronate, MRONJ occurs in 1–8% of cases with bone metastases, and in 0–1.8% when used as adjuvant therapy [17].

For denosumab, the FREEDOM and FREEDOM extension trials reported an incidence of 5.2 cases per 10,000 patient-years [18,19]. According to the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, MRONJ occurs in 0.7–6.9% of cancer patients treated with denosumab for bone metastases, while no cases were reported in those receiving it for cancer treatment-induced bone loss [16].

The vast majority of MRONJ cases are linked to BPs and denosumab, whether administered orally or intravenously. However, associations with other drugs have also been reported, including chemotherapeutic agents, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, angiogenesis inhibitors, mTOR inhibitors, immunotherapies [12], and even methamphetamine abuse [20].

More recently, a paradigm shift towards surgical intervention, even in earlier stages, has gained traction, with the goal of removing all necrotic bone to achieve primary healing. Despite this trend, the optimal timing, extent, and benefit of surgery versus conservative care, especially for different MRONJ stages, remain highly debated. This uncertainty is compounded by the unpredictable nature of the lesions themselves, which can remain stable for long periods or suddenly worsen, making it difficult to select the most appropriate strategy for an individual patient. This persistent evidence gap highlights the critical need for long-term cohort studies to evaluate the real-world effectiveness of different management strategies and identify predictors of successful outcomes.

Therefore, the primary aim of this 15-year retrospective cohort study was to evaluate and compare the long-term clinical outcomes of conservative versus surgical management of MRONJ in a tertiary center. A secondary aim was to identify key patient and disease-related factors that predict successful treatment resolution. The null hypothesis of this study was that conservative and surgical treatment approaches would result in comparable clinical outcomes in patients with MRONJ.

2. Patients and Methods

This retrospective study included patients diagnosed with medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) who were examined or hospitalized at the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University Hospital of Heraklion, Greece, between August 2006 and October 2021. The diagnosis was made according to the criteria defined by the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS) in 2007, 2009, 2014 and reaffirmed in the 2022 update. This observational cohort study was reported in accordance with the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines, and a completed STROBE checklist is provided as Supplementary Material. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Scientific and Research Ethics Committee of the University Hospital of Heraklion, Crete, Greece (Approval Code: 745/17-1-2018). This retrospective database-based observational study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and institutional policies for patient data protection.

A retrospective cohort identification process was conducted using the institutional medical database, yielding an initial cohort of 157 patients with suspected MRONJ. After rigorous application of the predefined inclusion criteria—conformity with the AAOMS diagnostic criteria, availability of a complete medical record, and the existence of at least one panoramic radiograph for assessment—130 patients qualified for final analysis. As the exposure of this cohort study was presentation with osteonecrosis, patients with MRONJ resulting from both low-dose and high-dose regimes were included. The study cohort represented a comprehensive recruitment framework encompassing multiple referral sources: internal referrals from our tertiary hospital’s departments; external referrals from other hospitals; and cases from private practices. All referred cases underwent thorough diagnostic validation before study inclusion.

The following parameters were recorded for each patient: age, gender, primary indication for therapy, drug type, duration and route of administration, drug holiday status, anatomical site of necrosis, triggering event, AAOMS stage, comorbidities, alcohol and smoking habits, diabetes mellitus, treatment type, outcome, and follow-up duration.

Microbiological cultures were obtained only in hospitalized patients presenting with acute infection, since routine sampling was not part of the diagnostic protocol. Information on pre-treatment oral hygiene status prior to initiation of antiresorptive therapy was not systematically available, because all patients were referred after MRONJ had already developed.

To maximize data inclusion, our analysis handled missing information on a per-variable basis. If a patient’s record was missing a specific data point, they were omitted only from calculations involving that variable. This approach accounts for the discrepancies in total patient numbers as shown in the tables in Section 3. Conservative treatment included intensive oral hygiene instruction and close clinical follow-up to monitor disease progression. Systemic antibiotics were administered empirically in cases with clinical signs of local infection, including pain, suppuration, erythema, edema of the surrounding soft tissues, or fistula formation. Chlorhexidine 0.12% mouthwash was also used three times daily, but only in conjunction with antibiotic therapy, for a duration of two weeks. A total of 72 patients received antibiotics; in 65 of them, the route of administration was oral, whereas in 7 patients with more prominent symptoms, accompanied by trismus and fever, intravenous administration with hospitalization was preferred. When bone spicules caused irritation, they were smoothed under local anesthesia (superficial debridement). This was done firstly with a round burr, followed by hand manipulation with a rongeur.

Surgical treatment was categorized as follows:

- Sequestrectomy—removal of the necrotic sequestrum along with the surrounding involucrum

- Saucerization—excision of necrotic bone along with a surrounding margin of viable bone

- Marginal osteotomy—bone removal while preserving the mandibular lower border or the floor of the maxillary sinus

- Segmental osteotomy—was reserved strictly for Stage III patients with either radiological evidence of full-thickness cortical necrosis extending to the mandibular lower border or maxillary sinus floor, or the presence/imminent risk of pathological fracture, in whom radical surgical debridement was required to control infection and achieve healthy borders.

Sequestrectomy was classified as a surgical procedure, as it involved the targeted removal of necrotic bone segments with clear borders of separation from viable bone, consistent with AAOMS treatment principles. Procedures limited to removal of minor bone spicules without addressing the necrotic core were considered conservative management.

Patients considered for marginal osteotomy or segmental resection underwent additional imaging with cone beam computed tomography (CBCT), and in resection cases, conventional CT was also performed. All surgically removed specimens were submitted for histopathological examination as per institution practice requirements.

For patients undergoing surgical treatment, a drug holiday was implemented after consultation with the prescribing physician (oncologist, orthopedic surgeon, or endocrinologist). The duration of drug discontinuation was three months for patients with osteoporosis and six months for those treated for malignancies.

Treatment outcomes were assessed at the last recorded follow-up visit and categorized into three mutually exclusive states based on the following explicit clinical and radiographic criteria:

- Complete Resolution: Defined as the complete closure of the mucosal defect with no remaining exposed bone, elimination of all signs of infection (e.g., purulent drainage, swelling, erythema), and the complete relief of symptoms such as pain or paresthesia.

- Stable Disease: Characterized by no change in the size of the exposed bone, the absence of worsening symptoms, and no new signs of active infection compared to the baseline assessment. This category represents successful disease management without full resolution.

- Progressive Disease: Defined as any increase in the size of the bone exposure, worsening pain or other symptoms, or the appearance of new signs of infection, such as an abscess or fistula.

All outcomes were determined by a senior maxillofacial surgeon based on a review of clinical examination notes and panoramic radiographs to ensure consistency in evaluation.

Treatment outcomes were evaluated through clinical examination and postoperative panoramic radiographs. All patients were followed closely to monitor for complications. Surgical cases were followed twice a month for the first three months, then every two months for the remainder of the first year. Conservatively managed patients were followed monthly for one year. For patients with multiple follow-ups, the most recent assessment was used for the primary outcome analysis. Long-term outcomes beyond one year were captured in the ‘resolution’ or ‘stable’ categories if they persisted.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics and frequencies were obtained for all variables. The normality of quantitative variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Pearson’s Chi-Square was used for classification tables. Non-parametric Spearman’s rho correlations were obtained.

Relative risks were calculated for dichotomous variables. Crude and adjusted odds ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated by univariate and multivariate logistic regression, respectively. Forward inclusion and backward elimination were used.

In the present study, for a hypothetical examined variable that would separate the cohort in two 60 patient groups, assuming a failure rate among the first group of interest is 0.5 and a true relative risk of failure for the second group of interest relative to the first one, is 1.5, we will be able to reject the null hypothesis that this relative risk equals 1 with probability (power) 0.816. The Type I error probability associated with this test of this null hypothesis is 0.05. We used the uncorrected chi-squared statistic to evaluate this null hypothesis.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis were used as a preliminary screening step to identify potential predictors of time-to-event outcomes. These predictors were then evaluated in a multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model to assess the effects of covariates on interval duration.

Kaplan–Meier analysis was used to estimate drug survival probabilities. The alpha level was set at 0.05, and an alpha level of 0.20 was used as a cut-off for variable removal in the automated model selection for multivariate logistic regression. All p-values were derived from two-sided tests, and statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

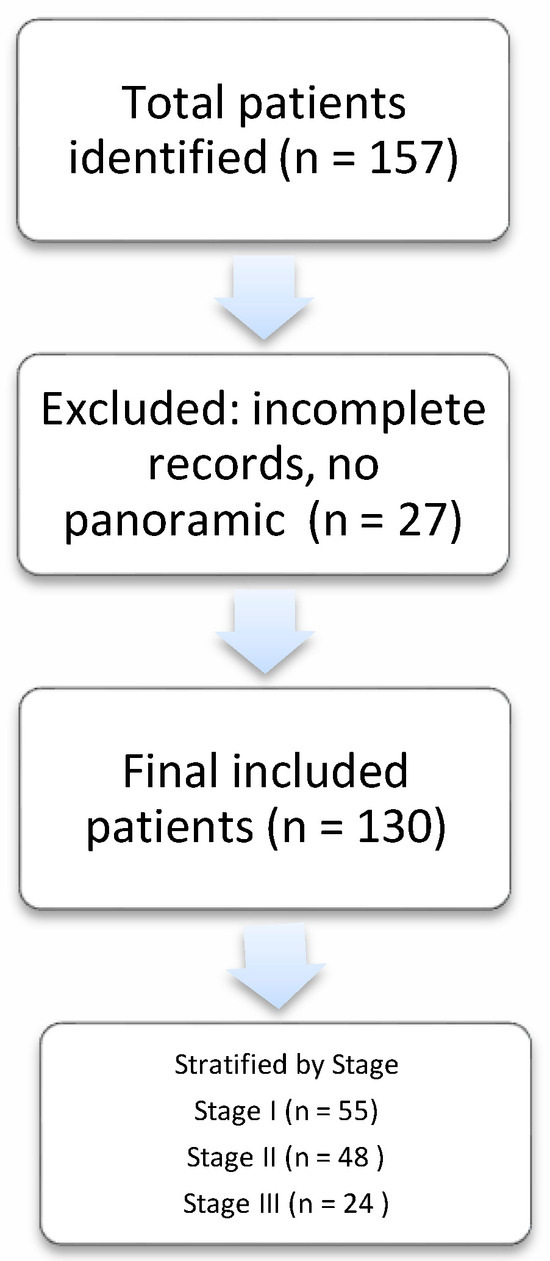

A total of 130 patients with medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) were evaluated. The mean age of our sample was 66 years old, with the vast majority of them having a known neoplastic condition (110/130, 84.6%). Sixty-three point eight (63.8%) percent of them were women. Breast cancer was the primary diagnosis for 40.8% of the cases. A flow chart of patient selection and inclusion is presented in Figure 2. The histopathology picture consisted of necrotic bone surrounded by various degrees of inflammation, distortion of the bony architecture and almost in all samples copious amounts of Actinomyces were detected. The location of osteonecrosis was primarily the mandible (66.2%), with stage I, II, and III of osteonecrosis accounting for 42.3%, 36.9% and 18.5% of cases, respectively. Zoledronic acid and denosumab were the most frequent drugs associated with the adverse effect of osteonecrosis (47.7% and 30.0%, respectively, of the study population). Notably, 59.2% of cases occurred following a dental extraction (Table 1a).

Figure 2.

Flowchart illustrating the patient selection process and inclusion criteria.

Table 1.

(a) 130 patients with MRONJ. Demographic and clinical variable descriptive statistics. (b) Descriptive Statistics for Continuous Variables.

3.2. Treatment Outcomes

Conservative treatment (mainly antibiotics) was selected for 74 patients (55.4%), while 55 patients (43.1%) were managed surgically. Of those who were managed surgically, 56 patients (43.1%) had complete resolution of the lesion at 6 months while 68 patients (52.3%) remained stable during the first 6 months of surveillance (Table 1a). In 6 (4.6%) patients MRONJ progressed despite treatment. The same percentages applied for the first year of surveillance. Another 5 patients obtained completed resolution in their follow-up period after the first year. Conservative treatment yielded a 20.3% resolution rate as opposed to surgical which yielded an 83.6%. Follow-up ranged from 1 to 144 months. Mean time of follow-up was, 20.5 ± 20.8, 24.11 ± 26.8 and 34.8 ± 36.5 months for Stage I, II and III patients, respectively. Conservative treatment was more frequently employed in Stage I patients (Pearson’s Chi Square, p < 0.001, Table 2). A sub-analysis of surgical approach by stage revealed a preference for less invasive procedures (sequestrectomy, saucerization) in early-stage disease, while more extensive resections (marginal, segmental osteotomy), were predominantly reserved for advanced stages. Surgical complications were observed only in 7 patients −5 cases of wound dehiscence, 1 case of late abscess and 1 case of fracture (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical variables per MRONJ AAOMS Stage.

Treatment strategies and their subsequent outcomes were strongly correlated with the AAOMS disease stage. For patients with Stage I disease, conservative treatment was the primary approach, utilized in 66.2% of cases. When surgical intervention was necessary for this early stage, it typically involved less extensive procedures such as sequestrectomy and saucerization.

In contrast, as the disease progressed to more advanced stages, the treatment approach shifted significantly towards surgery. Surgical intervention was required for 54.1% of Stage II patients and became the standard for Stage III patients (87.5%). The complexity of these surgical procedures also increased with the stage. The most invasive procedure, segmental osteotomy, was performed exclusively on Stage III patients. Furthermore, post-surgical complications, such as dehiscence and abscess formation, were only reported in patients from Stages II and III, highlighting the increased clinical challenges and risks associated with treating more advanced osteonecrosis. The amount of drug dosages that led to osteonecrosis showed no correlation with the severity of osteonecrosis (Spearman’s rho, p = 0.347). Furthermore, smoking and alcohol were not associated with the severity of osteonecrosis (Pearson’s Chi-Square p = 0.547 and p = 0.605, respectively). No association was observed between smoking or alcohol consumption and the choice of treatment (Pearson’s Chi-Square p = 0.274 and p = 0.107, respectively). Finally, being a smoker or alcohol drinker was not associated with worse treatment outcomes at one and six months postoperatively (Pearson’s Chi-Square p = 0.926 and p = 0.824, respectively).

3.3. Multivariate Analyses

Logistic regression analysis was performed to identify factors associated with complete resolution of MRONJ following treatment. In univariate analysis, surgical treatment was strongly associated with higher odds of resolution compared to conservative management (OR = 20.1, 95% CI: 8.1–50.0, p < 0.001). This association remained significant and even stronger in the multivariate model (OR = 52.5, 95% CI: 13.7–201.6, p < 0.001), after adjusting for age, sex, malignancy, substance use, lesion location, type and dose of antiresorptive drug. The exceptionally high odds ratio and wide confidence interval, while statistically significant, should be interpreted with caution as they may reflect the strong selection bias towards operating on more severe cases and the epidemiological limitations of the cohort size in subgroup analysis. No other variables—including age, sex, presence of malignancy, smoking, alcohol use, or location of osteonecrosis—were significantly associated with treatment resolution in either univariate or multivariate analysis. Similarly, no specific antiresorptive drug type showed a statistically significant effect on resolution outcomes. The number of administered doses was also not a significant predictor (univariate p = 0.312). These findings suggest that surgical intervention was the only independent predictor of complete post-treatment resolution in this patient cohort (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results from univariate and multivariate logistic regression for the prediction of post treatment resolution at any time during follow-up.

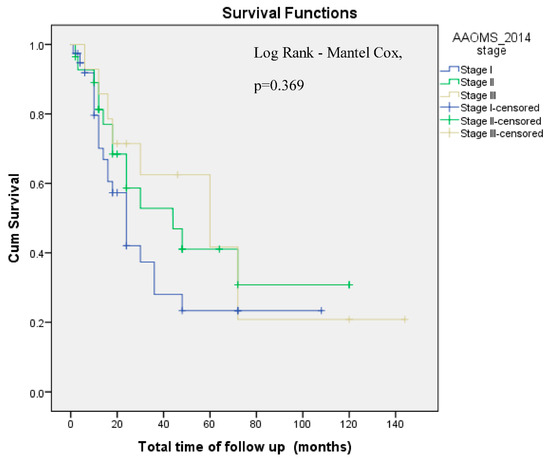

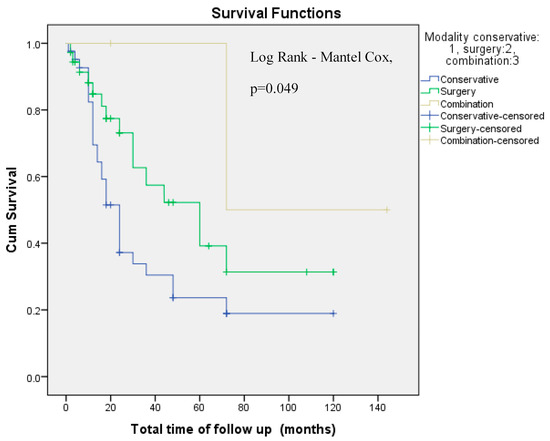

3.4. Survival Analyses

Cumulative overall survival did not differ by AAOMS ONJ Stage (Log-Rank Mantel–Cox, p = 0.369, Figure 3). Instead, cumulative overall survival differed by treatment modality (Log-Rank Mantel–Cox, p = 0.049, Figure 4). However, in a multivariate Cox regression model that accounted for patients’ age at diagnosis, sex, AAOMS stage at diagnosis, smoking, alcohol, type of antiresorptive drug, doses of antiresorptive drug and treatment modality applied, only doses of antiresorptive drug were associated with a reduced risk for death, with each dose conferring a 2.3% reduced risk for death. This paradoxical association could likely be due to confounding by indication, whereby patients who survived longer and had more stable underlying disease were able to receive more doses of therapy (Table 4).

Figure 3.

Cumulative Overall survival by AAOMS ONJ Stage (Log Rank-Mantel–Cox, p = 0.369). AAOMS: American Association of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery. Cum: Cumulative.

Figure 4.

Cumulative Overall survival by employed treatment modality (Log Rank-Mantel–Cox, p = 0.049). Cum: Cumulative.

Table 4.

Cox logistic regression on the probability of death.

4. Discussion

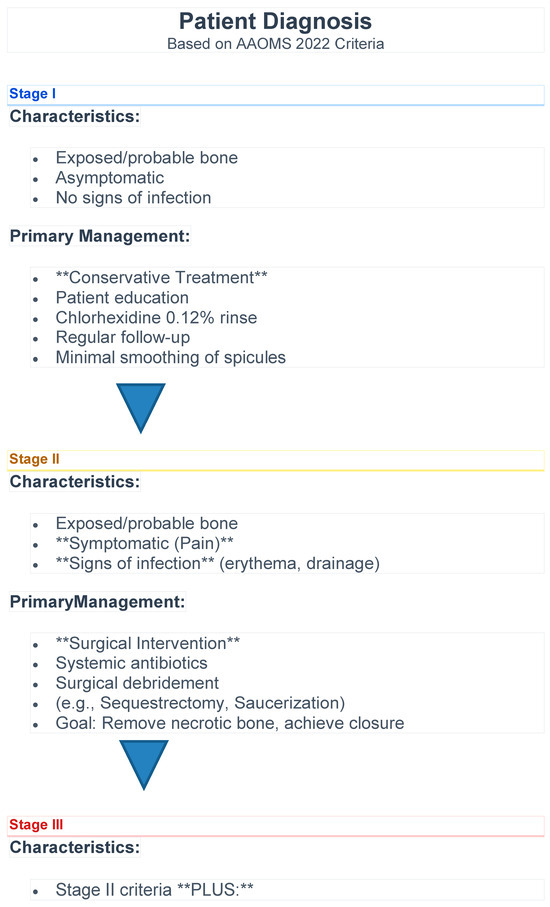

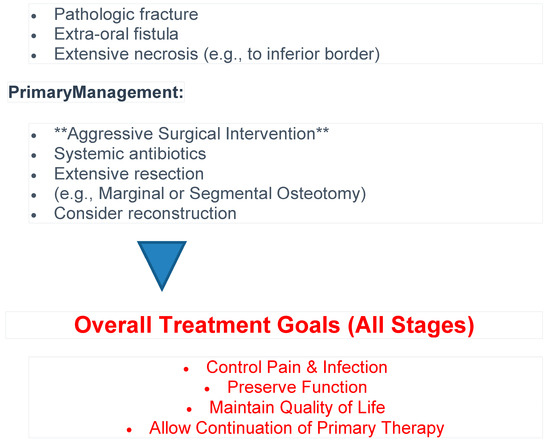

In this retrospective study of 130 patients with medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ), we provide a detailed characterization of demographic, clinical, and treatment-related variables across AAOMS ONJ stages. An algorithm for patient management according to the present study results is proposed in Figure 5. As this was a descriptive cohort with exploratory analysis of treatment outcomes, it cannot establish causality of treatment outcomes.

Figure 5.

Algorithm for patient management.

Our cohort reflects patterns similar to those reported in the literature, with a predominance of older female patients and a strong association with antiresorptive therapy used in oncologic settings—particularly breast cancer, which was the most frequent primary malignancy. Zoledronic acid and denosumab were the agents most commonly implicated, consistent with prior studies that have identified these medications as carrying the highest risk for MRONJ, especially when administered intravenously or in high doses for malignancy-related bone disease [3,12,21]. It is important to distinguish between patients receiving antiresorptives for osteoporosis (lower dose, per os) and those treated for malignancy (higher dose, IV), as their risk profiles, disease severity, and treatment goals differ significantly.

The mandible was the most commonly affected site in all ONJ stages, likely due to its anatomical and vascular characteristics that increase susceptibility to necrosis [22]. Interestingly, a majority of MRONJ cases (59.2%) followed a dental extraction, further reinforcing the established view that dentoalveolar trauma remains a significant trigger for ONJ development [23].

Early-stage disease (Stage I–II) comprised nearly 80% of cases. Conservative management predominated in Stage I, while surgical intervention rose to 87.5% in Stage III, reflecting guideline-based, stage-specific treatment approaches [8,16,24]. It is important to note that the choice of treatment was not randomized but was based on disease stage and the surgeon’s judgment, introducing a significant confounding by indication bias. Therefore, the superior outcomes associated with surgery likely reflect its application in more advanced, yet potentially more surgically amenable, cases rather than a definitive causal effect.

Surgical outcomes were favorable, with >95% of patients achieving resolution or stability at 6 and 12 months. Regression analysis identified surgery as the only independent predictor of complete resolution, even after adjusting for confounders (Table 3). These findings highlight the benefit of surgery, supporting its role in appropriately selected and advanced or refractory cases [25]. In contrast, the demographic factors (age, sex), lifestyle habits (smoking, alcohol), and specific drug-related variables (type, dosage) that we investigated were not significantly associated with resolution. This suggests that these particular factors may be less critical to treatment success than the choice of surgical intervention. However, our study did not assess other important local factors, such as the patient’s initial oral hygiene status or the presence of periodontal disease, which are well-established risk factors for MRONJ [3,12]. Given the multifactorial etiology of MRONJ, the main medication-related, local, systemic, and demographic risk factors are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of major etiological factors contributing to the multifactorial pathogenesis of MRONJ.

Achieving a ‘stable’ outcome, as defined by the MASCC/ISOO/ASCO clinical practice guideline (mucosal coverage: mild improvement, symptom/pain: mild improvement, sign of infection-inflammation: mild improvement, radiographic: no changes) [17], is a clinically significant success. This is particularly true for advanced cancer patients, where the primary goal is often palliation and maintaining quality of life to allow continuation of essential anticancer therapy. This point is critical, as this patient population is often systemically compromised. The underlying malignancy itself, or concurrent treatments such as chemotherapy, corticosteroids, and other immunomodulators, can lead to significant immune dysfunction [12,25]. In such an immunocompromised host, the necrotic bone serves as a persistent nidus for infection that the body’s compromised immune system cannot clear. Consequently, conservative measures like antibiotics, which rely on host defenses, are often insufficient to control the inflammatory process. Surgical intervention to debride the avascular, infected sequestrum is therefore essential to physically remove this bacterial reservoir, control the inflammation, and achieve a stable, symptom-free state.

Nonetheless, complications were observed in a small subset of patients, primarily in those undergoing more invasive interventions (e.g., segmental osteotomy), which were exclusive to Stage III. This underscores the importance of early diagnosis and the potential benefit of conservative approaches in the initial stages to avoid extensive surgical morbidity.

Our statistical analyses did not demonstrate a correlation between ONJ severity and potential risk modifiers such as cumulative antiresorptive dose, smoking, or alcohol use. MRONJ risk factors are broadly classified as medication-related, local, systemic, and demographic. In our cohort, the predominant medications were zoledronate and denosumab, consistent with existing literature [25,26]. Notably, most patients had been exposed to these drugs over an extended period—an established risk factor [25].

Dental extraction was the most common precipitating event, in accordance with the literature [3]. We also observed cases related to denture irritation and spontaneous onset. No implant-related MRONJ cases were recorded in our cohort. Patients who receive implants have been reported to have an improved level of oral hygiene [27]. Our finding that the mandible was the most commonly affected site aligns with previous reports [11]. This anatomical predisposition is multifactorial: the mandible possesses a denser, thicker cortical plate with lower intrinsic vascularity and reduced bone turnover. Compounding this, it relies on a more singular blood supply primarily from the inferior alveolar artery, whereas the maxilla benefits from thinner bone and a richer, more diffuse vascular network. This combination of dense bone and more limited perfusion likely increases its susceptibility to necrosis and impairs its reparative capacity.” A female predominance was observed, likely due to the higher incidence of osteoporosis and breast cancer—conditions often treated with antiresorptives [28]. Previous studies have also shown increased severity in younger patients (≤65 years), a finding supported by recent evidence [29].

Tobacco use is frequently cited as a risk factor for MRONJ; however, some studies have found no significant association. Drug discontinuation (“drug holidays”) remains controversial, as it may increase the risk of skeletal-related events or cancer progression [30,31]. Nonetheless, systematic reviews have suggested potential benefits in healing [32]. In our series, drug holidays were undertaken under close medical supervision, following agreement of the treating physician and did not result in adverse oncologic or skeletal events, suggesting that the protocol is safe within a multidisciplinary framework. However, the present study was not designed to measure the independent impact of the drug holiday on healing outcomes.

While the number of antiresorptive doses was not associated with disease stage, Cox multivariate survival analysis revealed a paradoxical association between increased drug doses and reduced risk of death. This finding likely reflects confounding by indication, whereby patients receiving more doses may have had better performance status or longer overall survival due to a more stable underlying disease. Importantly, overall survival did not significantly differ by MRONJ stage, but it was affected by the treatment modality employed. Although conservative treatment was associated with improved survival in univariate analysis (Figure 4), this was not maintained in the multivariate model (Table 4, p = 0.054), suggesting that treatment modality may be a proxy for disease severity or general health status rather than a direct determinant of survival.

Management of patients with medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) remains a subject of debate, despite two decades of accumulating evidence. In the early years following the initial reports of MRONJ, clinicians generally favored conservative and minimally invasive approaches to control symptoms such as pain, inflammation, and infection—particularly in the early stages of the disease [3]. This strategy aimed to alleviate symptoms and stabilize disease progression, reserving surgical intervention for cases unresponsive to conservative measures. More recently, however, there has been a paradigm shift towards early surgical intervention—even in initial disease stages—to limit the progression of necrosis and improve quality of life (QoL). Several studies have shown that surgical management may offer better disease resolution compared to conservative approaches, although further comparative trials are needed to validate these findings [24,33]. Surgical principles, such as raising full-thickness mucoperiosteal flaps to expose the entire necrotic area, resecting to bleeding bone, smoothing sharp bone edges, and achieving primary closure, should be strictly followed [34]. Demarcation between healthy and necrotic bone is essential and can be facilitated visually by identifying pinpoint bleeding areas or by using fluorescence-guided techniques when available [35]. The type of surgical procedure—sequestrectomy, saucerization, marginal, or segmental resection—depends on the extent of necrosis.

Reconstruction of osseous defects remains a controversial issue. Some authors advocate for aggressive surgery with microvascular tissue transfer [36,37,38], while others remain skeptical of this approach [39,40]. To reduce the risks associated with microvascular reconstruction, alternative methods such as segmental resection without reconstruction or plate fixation with submandibular gland transposition [22] have been proposed. Ultimately, surgical treatment must be individualized, considering the patient’s general health, treatment goals, potential complications, surgeon’s expertise, and collaboration with the broader medical team. In our study, surgical management—regardless of MRONJ stage—resulted in reliable pain control and mucosal healing, particularly among osteoporotic patients.

Adjuvant therapies—such as ozone oil, platelet-rich plasma, low-level laser therapy, pentoxifylline, tocopherol, and cilostazol—have been proposed to achieve partial or full healing in all stages, with improved results and the amelioration of many variables [41]; however, they lack robust evidence from prospective controlled trials [12,42]. Further research is needed to validate their therapeutic roles.

Limitations

This study has limitations inherent to its retrospective design. While we conducted and reported subgroup analyses, some may have been underpowered. The overall survival data could not distinguish between MRONJ-specific mortality and death from other causes, such as the underlying malignancy. Furthermore, our metric for cumulative drug exposure grouped different agents by the number of doses administered, and the follow-up duration for patients varied significantly due to the study’s 15-year recruitment period. Potential selection bias may arise from the exclusion of patients with incomplete medical records, and management protocols naturally evolved over the 15-year study period. Furthermore, our oncology-skewed referral base might underestimate the incidence of implant-related MRONJ, and we had a limited ability to fully adjust for all variations in oncologic comorbidities and systemic therapy regimens. Another limitation is the handling of drug class doses as a unique variable. However, this approach is consistent with established literature, where the duration of exposure—often quantified by the number of administrations—is recognized as a primary risk factor for MRONJ across different drug types. The AAOMS position paper explicitly identifies the duration of therapy as a key medication-related risk factor.

A further limitation is the lack of a formal assessment of inter-rater reliability for the outcome classifications. As a retrospective study, outcomes were determined based on existing medical records, and consistency was maintained by having a senior surgeon perform the final assessment. As a single-center report, our findings may have limited external validity. Furthermore, we lacked data on the patients’ pre-existing oral hygiene status before initiating antiresorptive therapy. The protocol did not include microbiological cultures to identify the specific pathogens, and thus, the conservative management relied on a standardized antibiotic regimen (amoxicillin) rather than culture-guided therapy.

Our results support a preference for conservative treatment for Stage I patients. The sample size, derived from a single center, yielded some high odds ratios with very wide CIs, which could be due to limited statistical power for some subgroup analyses. Thus, the large 50-fold OR for surgical intervention may reflect limited statistical power rather than a true epidemiological magnitude. Finally, the inverse association between antiresorptive drug doses and mortality should not be interpreted as the drug being protective against mortality, but rather as a proxy for longer overall survival and better performance status owing to plausible survival bias.

5. Conclusions

Our study is non-randomized, with a predominance of oncology cases over osteoporosis, thereby skewing the treatment approach toward surgical intervention, which was more likely to obtain resolution of the MRONJ. The decision for treatment was stage-driven, also influenced by patient age and underlying conditions, aiming to reduce disease severity and facilitate the resumption of anticancer therapies; therefore, findings of the present study should be interpreted with caution. Surgical decision-making was influenced by the experience of the treating surgeon, introducing potential selection bias. Stage I patients were, for the most part, sufficiently managed conservatively, while among Stage II and III patients who underwent surgery, almost half had achieved resolution and the remainder had stable disease. Treatment success has been reported to range between 50 and 80% [41].

Given the current lack of strong evidence supporting a standardized treatment protocol and the variable resolution results for surgical treatment, prevention and early intervention—through multidisciplinary collaboration—remain essential strategies. A coordinated team approach, involving dentists, oral surgeons, oncologists, and primary care physicians, is crucial to optimize outcomes and enhance the quality of life in patients with MRONJ. The findings support that individualized and stage-appropriate surgical intervention provides reliable outcomes for advanced cases.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/oral6010003/s1, STROBE checklist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.N.R., S.A. and E.K.; methodology, G.N.R., D.I. and D.D.; software, A.K. and C.Z.; validation, G.N.R., A.K. and E.K.; formal analysis, A.K., C.Z. and G.K.; investigation, G.N.R., D.I. and D.D.; resources, G.N.R. and E.K.; data curation, G.N.R. and D.D.; writing—original draft preparation, G.N.R.; writing—review and editing, A.K., D.I. and G.K.; visualization, A.K. and G.K.; supervision, G.N.R.; project administration, G.N.R. and S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Scientific and Research Ethics Committee of the University Hospital of Heraklion, Crete, Greece (Approval Code: 745/17-1-2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available due to ethical and privacy restrictions. The data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Raimondi, A.; Simeone, N.; Guzzo, M.; Maniezzo, M.; Collini, P.; Morosi, C.; Greco, F.G.; Frezza, A.M.; Casali, P.G.; Stacchiotti, S. Rechallenge of denosumab in jaw osteonecrosis of patients with unresectable giant cell tumour of bone: A case series analysis and literature review. ESMO Open 2020, 5, e000663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciobanu, G.A.; Mogoantă, L.; Camen, A.; Ionescu, M.; Vlad, D.; Staicu, I.E.; Munteanu, C.M.; Gheorghiță, M.I.; Mercuț, R.; Sin, E.C.; et al. Clinical and Histopathological Aspects of MRONJ in Cancer Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruggiero, S.L.; Dodson, T.B.; Aghaloo, T.; Carlson, E.R.; Ward, B.B.; Kademani, D. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons’ Position Paper on Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaws—2022 Update. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 80, 920–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, R.E. Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronate (Zometa) induced avascular necrosis of the jaws: A growing epidemic. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2003, 61, 1115–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Advisory Task Force on Bisphosphonate-Related Ostenonecrosis of the Jaws. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2007, 65, 369–376. [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, S.L.; Dodson, T.B.; Assael, L.A.; Landesberg, R.; Marx, R.E.; Mehrotra, B. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons Position Paper on Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaws—2009 Update. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2009, 67, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruggiero, S.L.; Dodson, T.B.; Fantasia, J.; Goodday, R.; Aghaloo, T.; Mehrotra, B.; O’Ryan, F. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw--2014 update. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 72, 1938–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, C.B.; Dagar, M. Osteoporosis in Older Adults. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 104, 873–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, S.; Pautke, C.; Van den Wyngaert, T.; Niepel, D.; Schiødt, M. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: Prevention, diagnosis and management in patients with cancer and bone metastases. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2018, 69, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltarella, I.; Altamura, C.; Campanale, C.; Laghetti, P.; Vacca, A.; Frassanito, M.A.; Desaphy, J.F. Anti-Angiogenic Activity of Drugs in Multiple Myeloma. Cancers 2023, 15, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmer, F.; Andersson, G.; Götrick, B.; Warfvinge, G.; Anderud, J.; Bjørnland, T. Prevalence, initiating factor, and treatment outcome of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw—A 4-year prospective study. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2018, 126, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolatou-Galitis, O.; Schiødt, M.; Mendes, R.A.; Ripamonti, C.; Hope, S.; Drudge-Coates, L.; Niepel, D.; Van den Wyngaert, T. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: Definition and best practice for prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2019, 127, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Hamadeh, I.S.; Katz, J.; Riva, A.; Lakatos, P.; Balla, B.; Kosa, J.; Vaszilko, M.; Pelliccioni, G.A.; Davis, N.; et al. SIRT1/HERC4 Locus Associated With Bisphosphonate-Induced Osteonecrosis of the Jaw: An Exome-Wide Association Analysis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2017, 33, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.; Cui, W.; Que, L.; Li, C.; Tang, X.; Liu, J. Pharmacogenetics of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 49, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaloo, T.; Hazboun, R.; Tetradis, S. Pathophysiology of Osteonecrosis of the Jaws. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 27, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasilakis, A.D.; Pepe, J.; Napoli, N.; Palermo, A.; Magopoulos, C.; Khan, A.A.; Zillikens, M.C.; Body, J.-J. Osteonecrosis of the Jaw and Antiresorptive Agents in Benign and Malignant Diseases: A Critical Review Organized by the ECTS. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 107, 1441–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarom, N.; Shapiro, C.L.; Peterson, D.E.; Van Poznak, C.H.; Bohlke, K.; Ruggiero, S.L.; Migliorati, C.A.; Khan, A.; Morrison, A.; Anderson, H.; et al. Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw: MASCC/ISOO/ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 2270–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bone, H.G.; Wagman, R.B.; Brandi, M.L.; Brown, J.P.; Chapurlat, R.; Cummings, S.R.; Czerwiński, E.; Fahrleitner-Pammer, A.; Kendler, D.L.; Lippuner, K.; et al. 10 years of denosumab treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: Results from the phase 3 randomised FREEDOM trial and open-label extension. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017, 5, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyrgidis, A. Denosumab, osteoporosis, and prevention of fractures. New Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabst, A.; Castillo-Duque, J.; Mayer, A.; Klinghuber, M.; Werkmeister, R. Meth Mouth—A Growing Epidemic in Dentistry? Dent. J. 2017, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magopoulos, C.; Karakinaris, G.; Telioudis, Z.; Vahtsevanos, K.; Dimitrakopoulos, I.; Antoniadis, K.; Delaroudis, S. Osteonecrosis of the jaws due to bisphosphonate use. A review of 60 cases and treatment proposals. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2007, 28, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Feng, Z.; An, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y. Combined reconstruction plate fixation and submandibular gland translocation for the management of medication-related osteonecrosis of the mandible. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 49, 1584–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyrgidis, A.; Vahtsevanos, K.; Koloutsos, G.; Andreadis, C.; Boukovinas, I.; Teleioudis, Z.; Patrikidou, A.; Triaridis, S. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: A case-control study of risk factors in breast cancer patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 4634–4638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Rabbany, M.; Lam, D.K.; Shah, P.S.; Azarpazhooh, A. Surgical Management of Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw Is Associated With Improved Disease Resolution: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 77, 1816–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.L.; Tu, M.M.; Ibrahim, M.F.K.; Basulaiman, B.; McGee, S.F.; Srikanthan, A.; Fernandes, R.; Vandermeer, L.; Stober, C.; Sienkiewicz, M.; et al. Long-term impact of bone-modifying agents for the treatment of bone metastases: A systematic review. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 29, 925–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, R.; Cameron, D.; Dodwell, D.; Bell, R.; Wilson, C.; Rathbone, E.; Keane, M.; Gil, M.; Burkinshaw, R.; Grieve, R.; et al. Adjuvant zoledronic acid in patients with early breast cancer: Final efficacy analysis of the AZURE (BIG 01/04) randomised open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 997–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogrel, M.A.; Ruggiero, S.L. Previously successful dental implants can fail when patients commence anti-resorptive therapy—A case series. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 47, 220–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.-X.; Zhao, S.; Chen, J. Risk Factors for Developing Osteonecrosis of Jaw in Advanced Cancer Patients Underwent Zoledronic Acid Treatment. Future Oncol. 2019, 15, 3503–3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Z.; An, J.; Zhang, Y. Factors Influencing Severity of Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw: A Retrospective Study. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 79, 1683–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamid, A.; Thomas, S.; Bell, C.; Gormley, M. Case series of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) patients prescribed a drug holiday. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2023, 61, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, N.; Seoudi, N. Management of Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw: An Overview of National and International Guidelines. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2024, 62, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramaglia, L.; Guida, A.; Iorio-Siciliano, V.; Cuozzo, A.; Blasi, A.; Sculean, A. Stage-specific therapeutic strategies of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the drug suspension protocol. Clin. Oral Investig. 2018, 22, 597–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Rabbany, M.; Sgro, A.; Lam, D.K.; Shah, P.S.; Azarpazhooh, A. Effectiveness of treatments for medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2017, 148, 584–594.e582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, F.; Heufelder, M.; Winter, K.; Hendricks, J.; Frerich, B.; Schramm, A.; Hemprich, A. The role of surgical therapy in the management of intravenous bisphosphonates-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endodontology 2011, 111, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pautke, C.; Bauer, F.; Otto, S.; Tischer, T.; Steiner, T.; Weitz, J.; Kreutzer, K.; Hohlweg-Majert, B.; Wolff, K.-D.; Hafner, S.; et al. Fluorescence-Guided Bone Resection in Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaws: First Clinical Results of a Prospective Pilot Study. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2011, 69, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldroney, S.; Ghazali, N.; Dyalram, D.; Lubek, J.E. Surgical resection and vascularized bone reconstruction in advanced stage medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 46, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, R.; Umar, G.; Guerra, R.C.; Akintola, O. Evaluation of segmental mandibular resection without microvascular reconstruction in patients affected by medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: A systematic review. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 59, 648–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, R.; Sacco, N.; Hamid, U.; Ali, S.H.; Singh, M.; Blythe, J.S.J. Microsurgical Reconstruction of the Jaws Using Vascularised Free Flap Technique in Patients with Medication-Related Osteonecrosis: A Systematic Review. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 9858921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, T.; Neirinckx, V.; Rogister, B.; Gilon, Y.; Wislet, S. Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw: New Insights into Molecular Mechanisms and Cellular Therapeutic Approaches. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 8768162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raguse, J.-D.; Trampuz, A.; Boehm, M.S.; Nahles, S.; Beck-Broichsitter, B.; Heiland, M.; Neckel, N. Replacing one evil with another: Is the fibula really a dispensable spare part available for transfer in patients with medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws? Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2020, 129, e257–e263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fede, O.; Canepa, F.; Panzarella, V.; Mauceri, R.; Del Gaizo, C.; Bedogni, A.; Fusco, V.; Tozzo, P.; Pizzo, G.; Campisi, G.; et al. The Treatment of Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw (MRONJ): A Systematic Review with a Pooled Analysis of Only Surgery versus Combined Protocols. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heifetz-Li, J.J.; Abdelsamie, S.; Campbell, C.B.; Roth, S.; Fielding, A.F.; Mulligan, J.P. Systematic review of the use of pentoxifylline and tocopherol for the treatment of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2019, 128, 491–497.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.