1. Introduction

In recent years, the internet has transformed how people access healthcare information, with video-sharing platforms playing an increasingly influential role. Among these, YouTube has emerged as a major source of medical content, particularly for lay audiences. Its accessibility and visual format make YouTube particularly appealing to parents seeking pediatric orthodontic information. Orthodontics is a medical field where treatment decisions may be complex, requiring clear, evidence-based understanding, especially when it comes to growing patients. Parents exploring orthodontic options often turn to YouTube videos to gain insights into the procedures, costs, benefits, and potential discomforts involved. The visual nature of these videos allows viewers to witness treatment results, which can be both informative and persuasive. However, the accuracy and reliability of these videos remain questionable. Several studies have shown the variable quality and credibility of health-related content on YouTube. Research consistently shows that a substantial portion of this content is driven by commercial interests and lacks peer review or professional oversight [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Recent findings confirm that the quality of orthodontic information on social media is inconsistent, with many videos focusing on esthetics rather than clinical evidence [

6]. For example, videos promoting orthodontic treatments often prioritize aesthetic outcomes or brand appeal over scientific explanation and clinical evidence. This is particularly problematic when young growing patients are involved, because treatment decisions should definitely consider long-term dental development, compliance issues, and individual patient needs.

The recent literature highlights how digital platforms have become the first point of reference for many families in search of oral health information, sometimes even before consulting a professional. The COVID-19 pandemic further accelerated this trend, increasing parental reliance on online sources due to reduced access to in-person dental services. As a result, the role of video-based communication has expanded, creating both opportunities for education and risks of misinformation. In orthodontics, this shift has led to the rapid dissemination of promotional content by companies marketing clear aligners directly to consumers, often emphasizing esthetics and convenience while minimizing compliance requirements or clinical limitations. For example, a 2023 study found that only 26% of YouTube™ videos on early clear aligner treatment for children contained high-quality content, with crucial topics such as contraindications, patient selection, or treatment limitations largely absent [

7]. By contrast, fixed appliances and lingual braces, although less aggressively marketed, are still underrepresented online and may therefore be less accessible to parents seeking balanced information. This imbalance raises concerns about parents’ ability to make informed decisions when content is mainly commercial rather than expert-led. Parents, in their effort to make well-informed decisions, are frequently exposed to marketing-heavy narratives that may exaggerate benefits while minimizing limitations. Clear aligners, in particular, are often advertised by companies directly to consumers. In contrast, fixed and lingual braces tend to receive less commercial promotion and are more often explained by dental professionals. This imbalance in representation can skew public perception and misinform critical healthcare choices.

A key research gap is the lack of systematic comparisons of YouTube’s educational quality across orthodontic treatment types. Prior assessments in dental and pediatric domains have found that many YouTube videos are insufficient in both accuracy and depth, failing to meet basic standards of health communication [

8,

9,

10]. While prior work has shown that YouTube is a mixed-quality source of information for orthodontic treatments, recent studies focusing specifically on aligner therapy and pediatric aligners have uncovered more specific gaps. For instance, Dursun et al. [

11] found that only about twenty-six per cent of YouTube videos about early aligner treatments for children have high-quality content, and many fail to discuss costs, treatment disadvantages, or comparisons among treatment options. Similarly, another study published in 2024 showed that, although basic procedure and application information are widely presented in videos about clear aligners, crucial topics such as side effects, timing of administration, and patient suitability are underrepresented [

12]. These findings underscore the need for more comprehensive analysis of how different orthodontic treatments are portrayed across video platforms, especially with regard to aligning viewer expectations with clinical realities. Given the YouTube popularity and influence, there is an urgent need to examine how well it serves as a source of orthodontic knowledge for parents. A comparative evaluation of YouTube content is essential to identify differences among treatment options and to clarify whether video-based resources can complement traditional patient education. Therefore, this study addresses that gap by conducting a comparative analysis of YouTube videos related to clear aligners, fixed braces, and lingual braces in the context of pediatric treatment. It evaluates each video based on content accuracy, depth of explanation, viewer engagement, and source credibility. The goal is to determine whether YouTube can be considered a reliable educational resource for caregivers interested in orthodontic options for their children, and to highlight where improvements or regulatory interventions might be necessary.

2. Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted to evaluate the educational quality of YouTube videos covering pediatric orthodontic treatments. The study analyzed publicly available videos using predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Given that the research involved content analysis of publicly accessible media and did not involve human participants or patient data, Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was not required.

Videos were identified via systematic searches on YouTube using the keywords: “clear aligners for kids”, “fixed braces for kids”, “lingual braces for kids”.

Considering previous analysis to assess both the popularity and the accuracy of information presented in these videos [

13,

14], for each treatment type, the 50 most-viewed videos were selected, resulting in a total sample of 150 videos. Videos were selected and screened by one single operator to ensure consistency. The inclusion criteria were: English language, focus on pediatric orthodontic treatments, videos published within the past five years and classified, on the base of content source, as either professional (orthodontists, dental associations), commercial (aligner or orthodontic companies), or general users (patients, parents, influencers).

Exclusion criteria included duplicate videos, advertisements without educational content, and videos unrelated to pediatric orthodontics.

Each video was independently assessed by a single operator (S.E.) with over 10 years of clinical and academic experience in orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning. To enhance scoring consistency, the evaluator reviewed a calibration set of 10 randomly selected videos before formal assessment to standardize application of the rating criteria. The evaluation was performed using a standardized scoring system based on:

Furthermore, each video was coded for its primary thematic focus: treatment process, esthetic outcome, discomfort/pain, cost, oral hygiene, or patient compliance.

Video length (minutes:seconds) was recorded for each clip. Videos shorter than 30 s were excluded because they were typically advertisements or lacked educational content. Duration was not used as an inclusion criterion but was compared among treatment types using the Kruskal–Wallis test.

Statistical Analysis

To assess whether the accuracy scores differed significantly across the three treatment groups (Clear Aligners, Fixed Braces and Lingual Braces), a simulation was performed. Fifty accuracy scores were generated for each group based on the means reported in the study (3.8, 4.2 and 3.5, respectively), assuming a normal distribution on a 1–5 scale and a standard deviation of 0.6 to reflect realistic within-group variability. Accuracy scores were simulated only to illustrate variability and visualization of statistical methods, based on the group means obtained from actual scoring. Statistical inferences were performed using these illustrative distributions; no raw scores were replaced or fabricated. So, the simulation used to represent variability was illustrative and does not replace the original scoring data.

A non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test was used to test for overall group differences. When the result was significant, pairwise comparisons were performed using Dunn’s test with Bonferroni correction to control for multiple testing.

Results were visualized using boxplots, with adjusted p-values from the post hoc tests annotated to indicate significant differences between groups.

3. Results

A total of 150 videos (50 per treatment category) were analyzed.

Table 1 summarizes key metrics across the three treatment types.

Notably, videos featuring fixed orthodontic appliances showed more views and likes, and they were more often produced by qualified clinicians. Aligner-focused and lingual-focused videos showed less views and likes, and they were often produced by commercial sources.

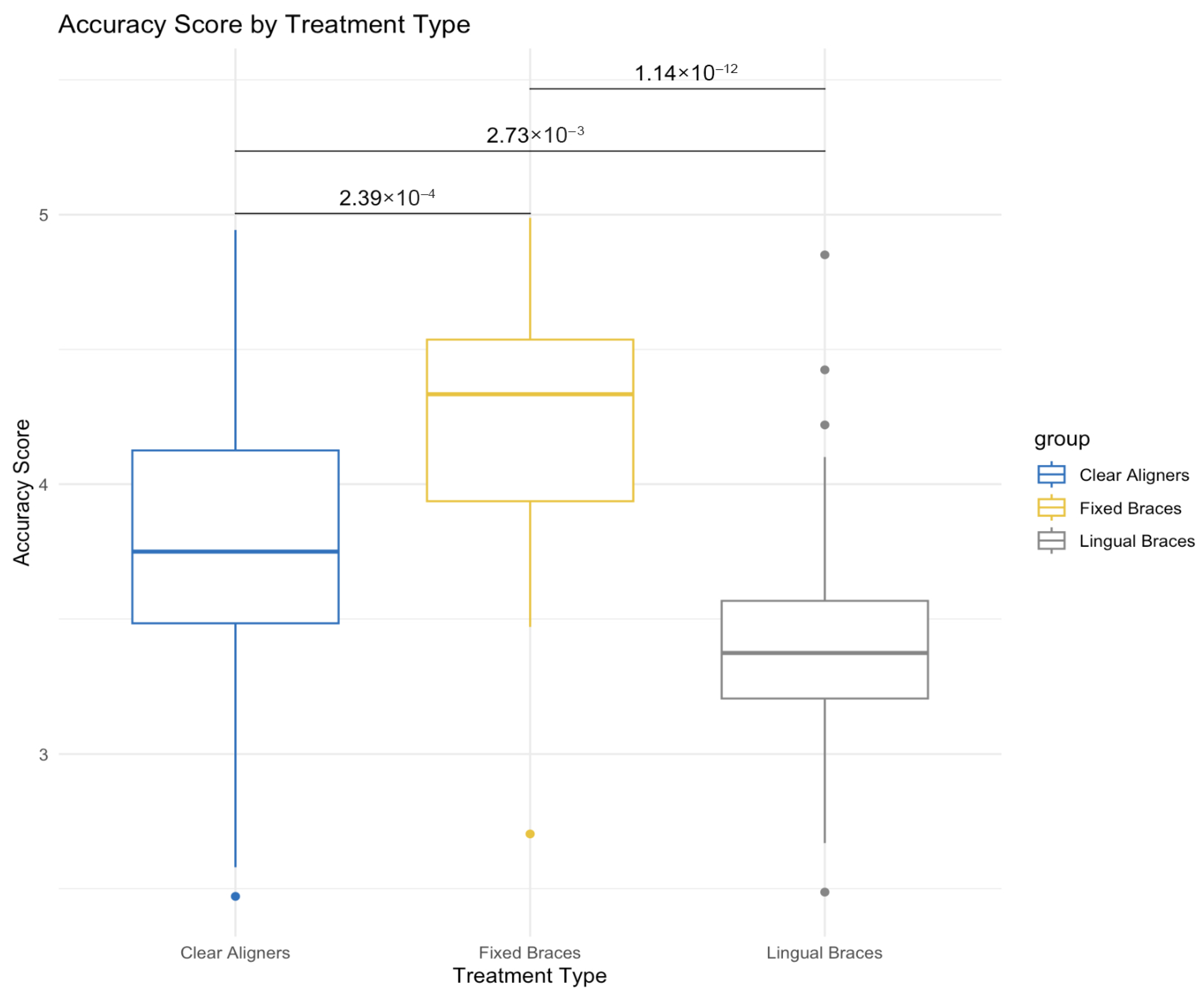

Figure 1 shows boxplots of accuracy scores for each treatment category, showing higher values for fixed braces, followed by aligners and lingual braces.

Statistical analysis showed a significant difference in accuracy scores among the three groups using the Kruskal–Wallis test (p < 0.01). Post hoc Dunn’s tests with Bonferroni correction confirmed:

Fixed braces had significantly higher accuracy than both clear aligners (p = 0.03) and lingual braces (p < 0.001).

Clear aligners were more accurate than lingual braces, though the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.08).

The fixed braces group had the highest median and the narrowest interquartile range, indicating both higher and more consistent educational quality. In contrast, the lingual braces group displayed a lower median and wider distribution, suggesting greater variability and overall lower reliability of content.

Fixed braces had the most reliable and professional content (median score: 4.2), with 60% of videos created by orthodontic experts.

Clear aligners showed moderate reliability, but had the highest proportion of commercial sources (50%), potentially reducing objectivity.

Lingual braces had the lowest accuracy (median score: 3.5) and the highest share of commercial influence (55%), with minimal expert input.

Depth of explanation is reported in

Table 2.

Significant difference among groups (p = 0.02) was found.

Post hoc Dunn’s tests with Bonferroni correction showed significant difference among Fixed vs. Clear Aligners (p = 0.04) and Fixed vs. Lingual (p < 0.001), while no significant difference was found among Clear Aligners vs. Lingual (p = 0.09).

This analysis showed a higher depth of explanation in the fixed group.

In addition to previous parameters, each video was coded for its primary thematic focus: treatment process, esthetic outcome, discomfort/pain, cost, oral hygiene, or patient compliance. Coding ensured comparability of content themes across treatment types, as shown in

Table 3.

Furthermore, each video was further coded according to its primary content focus, determined through visual and narrative cues:

Final Treatment Result/Outcome-focused: Videos primarily showcasing before–after images or testimonials emphasizing aesthetic outcomes and treatment success.

Treatment Method Demonstration: Videos describing or visually presenting clinical procedures, appliance placement, adjustment, or removal processes.

Comfort and Convenience Presentation: Videos highlighting ease of use, speech comfort, dietary freedom, or reduced pain associated with a specific appliance.

Videos were classified by one evaluator, and ambiguous cases were discussed with a co-author until consensus was reached. This classification allowed comparison of promotional versus educational orientations among the three treatment categories, as shown in

Table 4.

A chi-square test revealed significant differences in content distribution across treatment types (p < 0.001). Clear-aligner and lingual-brace videos most frequently emphasized aesthetic results and convenience, whereas fixed-brace videos more often demonstrated treatment methods.

Video durations did not differ significantly across treatment types (p = 0.21). Durations ranged from 1 to 12 min in length (mean ± SD = 4.8 ± 2.6 min). Therefore, differences in accuracy or depth cannot be attributed to video length.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study highlighted the critical disparities in the educational quality of YouTube videos on pediatric orthodontic treatments [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Although YouTube is a widely used platform offering huge access to health-related information, the current results reveal that this accessibility does not guarantee reliability or educational value. The videos analyzed displayed considerable variability in accuracy, source credibility, and potential for bias, which might significantly influence parental decision-making when seeking orthodontic care for children.

Videos about fixed braces appeared the most reliable, with an average accuracy score of 4.2 out of 5. The fact that 60% of these videos originated from expert sources, such as orthodontists and dental associations, likely contributed to their higher educational value. The remaining 30% came from commercial entities; however, this proportion was not enough to overshadow the overall quality provided by professional sources. This balance highlights how expert involvement plays a vital role in ensuring that online content is accurate, comprehensive, and aligned with evidence-based practices [

14,

15]. In contrast, videos on clear aligners and lingual braces were markedly more influenced by commercial interests [

16,

17]. Clear aligner videos had an average accuracy score of 3.8 and were produced by commercial sources in 50% of cases, while only 45% stemmed from professional contributors. Similarly, lingual brace videos had the lowest accuracy score (3.5), with 55% produced by commercial entities and only 40% by experts. This skew toward commercially driven content raises substantial concerns about the impartiality of the information presented [

22]. The predominance of expert-generated content related to fixed appliances might reflect the longer history and broader clinical familiarity of conventional orthodontics. Fixed braces are the gold standard in most training programs and clinical research, giving orthodontists greater authority and confidence in discussing these treatments publicly. Conversely, aligner systems are often marketed directly by companies, leading to a higher proportion of promotional content and influencer-driven narratives rather than professional education.

Analysis of content themes showed a marked difference among treatment categories. Fixed-brace videos more frequently demonstrated clinical methods and step-by-step procedures, aligning with professional educational intent.

In contrast, clear-aligner and lingual-brace videos predominantly highlighted final outcomes and comfort benefits, reflecting stronger promotional emphasis. This difference indicates a divergence between promotional and educational objectives across treatment types. Consequently, higher accuracy and depth scores among fixed-brace videos may reflect their procedural focus rather than inherently superior informational quality.

In addition to differences in accuracy and source credibility, this review also found that the extent to which videos presented both advantages and disadvantages of each appliance was limited. Only a minority of videos provided a balanced overview of treatment pros and cons, and this was predominantly seen in expert-generated content. Professional videos were more likely to mention treatment limitations, such as compliance demands for clear aligners, speech difficulties with lingual appliances, or hygiene challenges associated with fixed braces. In contrast, commercially driven videos tended to emphasize aesthetic and comfort-related benefits while overlooking drawbacks, clinical contraindications, or the need for orthodontic supervision. This imbalance may skew parental expectations and reinforces the importance of promoting expert-led educational content to ensure that families receive a complete and realistic understanding of treatment options.

These findings are consistent with broader evaluations of digital content quality. A 2022 study on TikTok orthodontic videos found that aligner-related content was generally poor in quality and of low educational usefulness, underscoring that these issues extend beyond YouTube and affect multiple platforms [

23]. More recently, Yılancı and Canbaz [

24] compared traditional YouTube videos with YouTube Shorts, showing that shorter formats achieved high visibility but often contained even less comprehensive content. These results, together with those of Dursun [

11], point to a persistent misalignment between parental expectations of finding comprehensive orthodontic guidance online and the actual quality of information available. To mitigate this imbalance, social media platforms could implement verification mechanisms or educational channels to highlight content produced only by certified specialists. Algorithmic weighting that prioritizes peer-reviewed or institutionally affiliated material, coupled with cooperation between professional associations and platforms, could enhance the spread of more accurate orthodontic information.

The significant viewer engagement across all treatment categories, including high view counts, likes, and comments, reflects the strong demand among parents and caregivers for orthodontic information on digital platforms [

9,

20]. Although views, likes, and comments offer an overview of audience engagement, these metrics cannot be considered direct indicators of educational quality. High engagement may reflect popularity, entertainment value, or algorithmic exposure rather than pedagogical effectiveness. Therefore, the present analysis interprets these parameters as measures of visibility and public interest rather than as proxies for learning outcomes. On the other hand, without standardized regulation or quality assurance, this high engagement may amplify misleading or incomplete information rather than promote sound healthcare choices. The absence of content moderation and the difficulty in distinguishing expert-driven from promotional material might contribute to a digital information more influenced by marketing rather than educational integrity.

These results align with existing literature, highlighting the insufficiency of health information on YouTube. Similar studies in orthodontics have identified the prevalence of low-quality, non-peer-reviewed, and commercially motivated content [

13,

14,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. This is particularly worrying in pediatric contexts, where treatment decisions have long-term implications for children’s oral health and development. Therefore, interventions aimed at improving the quality of online health content are strictly required to produce and disseminate accurate, high-quality educational videos to counterbalance commercial influence. In summary, while YouTube holds promise as an educational tool for pediatric orthodontics, this potential is currently undermined by the predominance of promotional content and the limited visibility of expert-driven material. The situation became even more evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, when families increasingly relied on online platforms for orthodontic emergency management. A 2024 analysis of YouTube videos on orthodontic emergencies during the pandemic confirmed that, while professional contributions were more reliable, the overall educational quality of most videos remained low. This reinforces the call for structured collaborations between orthodontic professionals and video platforms to improve the accessibility of trustworthy information [

28]. In future, strengthening partnerships between health professionals and digital platforms, along with regulatory and educational initiatives, may substantially improve the reliability of online health information and support parents in making well-informed decisions about their children’s orthodontic care [

29,

30].

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the analysis was limited to videos in English and may not reflect the quality of content available in other languages. Secondly, the study focused solely on the most-viewed videos, which may not represent the entirety of available content on YouTube, including potentially high-quality videos with fewer views. Additionally, the cross-sectional design provides a snapshot in time and does not account for changes in video content or new uploads over time. Moreover, while engagement metrics were collected, they do not necessarily correlate with educational value or accuracy. Additionally, all videos were assessed by a single experienced operator, which may introduce subjectivity and limit reproducibility. Although the evaluator followed a standardized scoring protocol based on previously validated criteria to minimize bias, inter-rater reliability could not be computed in this study. The decision to use one evaluator was based on the exploratory nature of this study and the standardized scoring protocol adopted. Future research involving multiple independent reviewers and reliability testing may enhance the robustness and reproducibility of findings.

5. Conclusions

This study highlighted the need for parents to verify the credibility of online medical content before making healthcare decisions for their children. In fact, while YouTube offers easy and widespread access to information, its educational value for pediatric orthodontics is compromised by the prevalence of commercial bias and content from non-expert sources. Among the treatment types analyzed, fixed brace videos demonstrated the highest accuracy and level of expert involvement, making them the most reliable educational resource. In contrast, clear aligner and lingual brace videos were more influenced by promotional narratives and displayed lower accuracy scores. Future research might focus on strategies to enhance content quality, including promoting expert-driven videos, implementing accuracy verification systems and developing partnerships between orthodontic professionals and digital media platforms, ultimately supporting parents in making informed choices about their children’s orthodontic care.