Highlights

Patients with controlled hypertension may experience hemodynamic changes during dental extractions. Oxygen saturation and systolic blood pressure were the parameters that showed the greatest alterations compared to controls.

What are the main findings?

- Patients taking antihypertensive drugs may experience alterations in vital signs during dental extractions, although in most cases there are no serious clinical repercussions.

- There are differences between controlled hypertensive patients and healthy controls in oxygen saturation, systolic blood pressure, and heart rate before, during, and after administration of vasoconstrictor anesthetic for dental extraction.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- Monitoring blood pressure, oxygen saturation, and heart rate is crucial for managing hypertensive patients during dental procedures, especially those involving anesthesia.

- The use of anesthetic with vasoconstrictor alters hemodynamic parameters in the medically controlled hypertensive patient, but without clinical repercussions; therefore, the use of two cartridges seems effective and safe.

Abstract

Background: The progressive aging of the population has led to an increased prevalence of chronic diseases and polypharmacy, with arterial hypertension representing one of the most frequent conditions. Consequently, the management of vital signs during dental interventions, such as tooth extractions, has acquired particular clinical relevance. The present study aimed to analyze the hemodynamic impact of vasoconstrictors (VAs) used in local anesthesia (LA) at different procedural stages in patients with pharmacologically controlled hypertension, as well as to compare these effects with those observed in normotensive individuals. Additionally, the study evaluated the influence of antihypertensive medication on hemodynamic responses during dental extraction. Methods: A case–control study was conducted at Dr. Peset University Hospital (Valencia, Spain), including 254 patients—148 hypertensive (controlled with type 1 and 2 antihypertensive therapy) and 106 normotensive controls. Hemodynamic parameters—systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), heart rate (HR), and oxygen saturation (SO2)—were recorded at four time points: baseline (T1), five minutes post anesthesia with 4% articaine and epinephrine (T2), upon completion of extraction (T3), and one week postoperatively (T4). Results: The SBP remained more stable in normotensive patients, while both groups exhibited a slight DBP decrease at T2, with recovery by T3. In hypertensive patients treated with angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), DBP decreased further. Tooth extraction under controlled hypertension conditions caused a mild, clinically insignificant increase in HR. Conclusions: Significant fluctuations in SBP, DBP, and SO2 occurred during dental extraction, underscoring the necessity for vigilant intraoperative monitoring and individualized management of hypertensive patients.

1. Introduction

Tooth extraction involves the complete removal of the tooth or separation of the dental root from its socket, with the aim of achieving effective analgesia and minimizing trauma to adjacent tissues. Local anesthetics (LAs) combined with vasoconstrictors (VAs) are widely used in clinical practice to provide profound, predictable, and sustained anesthesia, thereby reducing intraoperative pain and stress. VAs constitute an exogenous source of catecholamines that augments the endogenous sympathoadrenal response typically triggered by procedural anxiety [1].

The progressive aging of the population has increased the prevalence of multimorbidity and polypharmacy, with arterial hypertension (HTA) remaining one of the most common chronic conditions. Consequently, the rigorous assessment and management of vital signs during dental extractions have become increasingly relevant. Current recommendations from the American Heart Association (AHA) and the American Dental Association (ADA) endorse the use of adrenergic anesthetics—such as epinephrine or norepinephrine-containing formulations—in patients with controlled cardiovascular disease, with a maximum of 2–3 cartridges per procedure [2]. Additional evidence [3] further supports the safe use of LA–VC combinations in clinically stable hypertensive patients.

The 2019 AHA guidelines define hypertension as a sustained systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 80 mmHg across three separate measurements spaced more than one week apart, or a single reading of SBP > 210 mmHg or DBP > 120 mmHg [4]. As one of the leading global risk factors for mortality—associated with stroke, myocardial infarction, and target-organ damage—HTA requires early identification of individuals with potentially hazardous blood pressure elevations [3].

Dental procedures may elicit significant physiological stress capable of altering hemodynamic parameters, particularly in hypertensive individuals. These alterations may arise from nociceptive stimuli, anxiety, the pharmacodynamic effects of VAs, or the activation of the sympathetic nervous system [5]. Given their reduced cardiovascular reserve and autonomic reactivity, hypertensive patients may experience clinically relevant increases in blood pressure or heart rate. Therefore, continuous and systematic hemodynamic monitoring is essential to ensure timely detection of adverse responses and to optimize procedural safety [6].

Antihypertensive drugs reduce blood pressure through diverse mechanisms, including modulation of the renin–angiotensin system, autonomic blockade, vascular smooth muscle relaxation, or diuresis. Major drug classes include beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), diuretics, and direct vasodilators. The selection of an antihypertensive regimen—or combination therapy—must consider prior therapeutic response, comorbid conditions, potential pharmacological interactions, and patient-specific cardiovascular risk profiles, while ensuring adequate efficacy, tolerability, and safety [7]. Recommendations from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Society of Hypertension emphasize individualized drug selection guided by comorbidity burden, side-effect profile, cost, and quality-of-life impact [8].

The present study aims to evaluate the influence of VC-containing LA formulations on multiple hemodynamic variables (diastolic blood pressure [DBP], systolic blood pressure [SBP], heart rate [HR], oxygen saturation [SO2], and pulse rate [PR]) at several operative time points in pharmacologically controlled hypertensive patients (cases) compared with normotensive individuals (controls). Additionally, it seeks to determine whether hemodynamic responses vary according to the specific antihypertensive drug class prescribed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A case–control study was conducted at Hospital Universitario Doctor Peset (Valencia, Spain). Patient recruitment began in December 2018 and concluded in November 2022. The study was approved by the local Research Ethics Committee (date 29 March 2018, code: 82/17) and was carried out in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki on human medical research.

The sample consisted of 254 patients undergoing tooth extraction. Two main groups were established based on their hypertension diagnosis: the control group (106 subjects, 41.7% normotensive) and the hypertension group (148 subjects, 58.3% hypertensive). The sample included 134 men (52.8%) and 120 women (47.2%). Groups were also categorized according to the antihypertensive medications prescribed, with emphasis on ACEIs and beta-blockers. In total, eight antihypertensive regimens were identified—ARB, ACEI, BETA, BETA + ACEI, BETA + diuretic, BETA + ARB + diuretic, ARB + diuretic, and ARB + calcium antagonist + diuretic—prescribed by each patient’s cardiologist and included in the analysis.

The inclusion criteria were patients with stage I–II hypertension (case group) or normotensive individuals (control group), aged ≥ 18 years. Exclusion criteria included allergy to articaine, blood pressure > 180/110 mmHg, history of cardiovascular disease within the previous six months, current oncological treatment, kidney transplantation, hyperthyroidism, pheochromocytoma, ASA classification > III, substance abuse (cocaine or amphetamines), or insufficient cognitive capacity to complete the questionnaires or provide informed consent.

2.2. Hemodynamic Parameters

Systolic blood pressure (SBP [mmHg]), diastolic blood pressure (DBP [mmHg]), and heart rate (HR [bpm]) were recorded with an electronic sphygmomanometer (Omron M3, Kyoto, Japan) on the left arm. Oxygen saturation (SO2 [%]) and pulse rate (PR [bpm]) were measured using the Fingerchip PulseFoxy PM-50® pulse oximeter (Shenzhen Mindray Bio-Medical Electronics Co., Atlanta, GA, USA), with the probe placed on the patient’s left index finger and ensuring the absence of nail polish.

The same investigator assessed each patient’s medical history, radiographic examination, and the tooth scheduled for extraction. SBP, DBP, HR, SpO2, and PR were recorded at four timepoints: T1 (baseline, before surgery); T2 (5 min after administration of local anesthesia with 4% articaine and epinephrine 1:200,000 as VC [Ultracain, Normon S.A., Madrid, Spain], using a block or infiltration technique according to the site, with a maximum of 2–3 cartridges); T3 (immediately after completion of the extraction); and T4 (one week post-surgery, at the time of suture removal).

The Modified CORAH/MDAS, Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HARS) were used in the present study as anxiety assessment instruments [9]. Although these scales are well established for evaluating different dimensions of anxiety that may influence hemodynamic parameters—ranging from dental-specific anxiety to general somatic and psychic symptoms—they were not the primary focus of this investigation No statistically significant differences were observed between anxiety levels and the hemodynamic variables analyzed.

It was estimated that a minimum sample of 250 patients would be required for an F-test using a general linear ANOVA model to achieve 80% statistical power to detect a small-to-medium effect size (f = 0.15) in the mean value of a parameter between two groups (normotensive controls vs. hypertensive cases), assuming a 95% confidence level.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess the normality of data distribution. Given the large sample size, parametric analyses were applied (ANOVA, Student’s t-test). A descriptive analysis of all variables was performed, including calculation of mean, standard deviation (SD), minimum, maximum, and median values for continuous variables, and absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables.

Inferential analysis was performed using a nonparametric Brunner–Langer model for longitudinal data to evaluate the effect of different antihypertensive drug combinations on hemodynamic parameters and to determine whether any regimen achieved superior hemodynamic control at specific timepoints. Student’s t-test for independent samples was applied to compare means between categorical variables. Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05, with a 95% confidence interval.

3. Results

A total of 254 patients underwent surgery (148 cases and 106 controls). In cases group, 35.1% of patients were taking beta-blockers, 23.6% were receiving calcium agonists, 29.7% were treated with ACE inhibitors, 43.2% were taking diuretics, and 7.4% were receiving vasodilators. The mean age was 58.3 ± 18.7 years (range: 14–93), and all patients were Caucasian and resided in the same geographical area. The groups were considered homogeneous, given that antihypertensive drugs are typically prescribed from approximately 50 years of age. Furthermore, a slight male predominance was observed (52.8%), introducing a gender-related variable into the analysis; however, no statistically significant differences were identified.

In the AHT group, all patients received some form of pharmacological treatment for HTA, most commonly a combination of several drugs. This multiple drug use was a critical factor in the comparative analysis between antihypertensive treatments. As an initial step, the effect of the presence or absence of drug therapy, as well as different combinations of antihypertensive drugs, was evaluated.

Regarding diuretic use (52.7% of patients), participants were categorized according to whether they were receiving a single diuretic (49.3%) or a double diuretic regimen (3.4%). The complexity arising from the concomitant use of multiple antihypertensive agents necessitated the analysis of each drug type separately, both as a binary variable (cases vs. controls) and according to drug class. Beta-blockers were the most frequently prescribed medication, particularly among patients over 60 years of age (82%) and those aged between 46 and 60 years (15%).

The combination of antihypertensive drugs was assessed using the Brunner–Langer model to analyze the five hemodynamic parameters across eight different drug combinations. This analysis revealed that none of the combinations demonstrated a superior or optimal effect on the control of hemodynamic variables; therefore, subsequent analyses focused on the most commonly prescribed drugs. The most frequent regimens consisted of two or three antihypertensive drugs (<3%), whereas only 2% of patients were receiving a combination of four drugs.

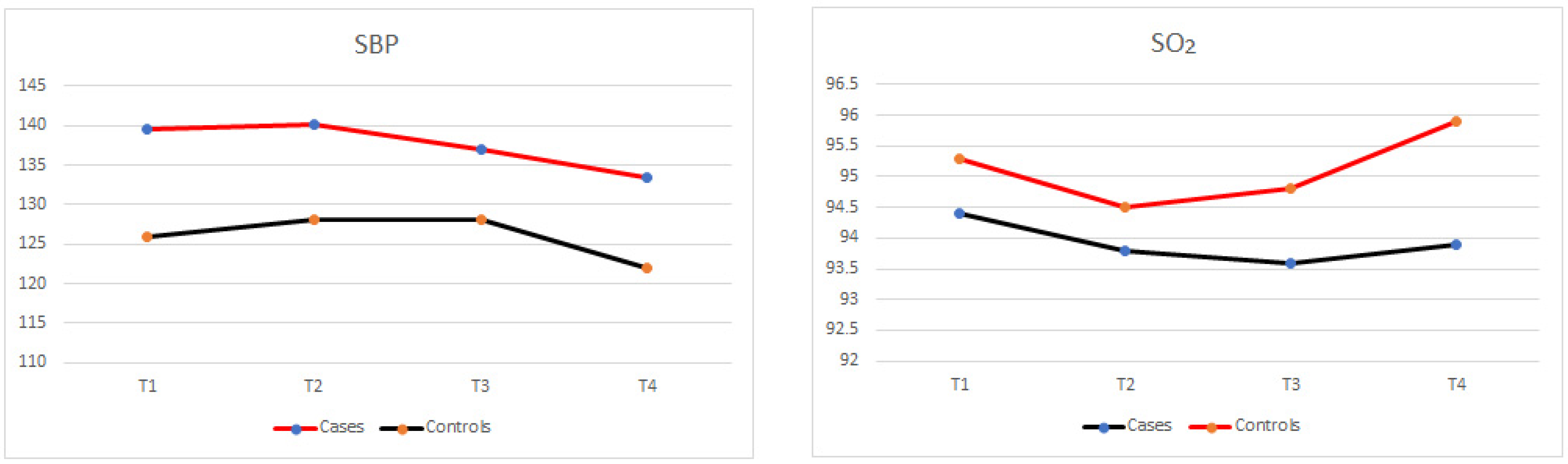

Patients assigned to the different treatment groups showed significantly different SBP values between cases and controls at T1, T2, T3, and T4 (p = 0.001), as illustrated in Figure 1 and Table 1; however, these differences were already evident at baseline. Despite the presence of a weak trend (p = 0.094), SBP did not vary significantly throughout the intervention when comparing its evolution across T1, T2, T3, and T4 within each group. Furthermore, this finding was consistent across all treatment groups (type of antihypertensive drug, p = 0.818), indicating that the specific pharmacological regimen did not result in differential changes in the evolution of hemodynamic parameters. Overall, SBP remained stable during the intervention and was comparable to preoperative baseline values.

Figure 1.

Evolution of systolic blood pressure and oxygen saturation between cases and controls being hemodynamic variables that showed statistically significant differences.

Table 1.

Comparison of the mean values of hemodynamic variables between cases and controls across the different time points analyzed.

Regarding the evolution of SBP with the different antihypertensive drug combination, no changes were recorded during the study interval (p = 0.454) in any of the 8 combination groups; the type of medication did not result in significantly different DBP values (p = 0.307). The patients treated with ARA II agents alone, ACEIs alone, ARA II agents with diuretics, or calcium antagonists with ARA II and diuretics tended to experience a change (increase or decrease) in PR after injection, followed by a return to baseline values.

3.1. SBP and DBP Parameters

The comparison of hemodynamics parameters showed that SBP increased slightly at T2 in the AHT group, and proved more stable in the control group, without clinical relevance (Figure 1). SBP showed significant differences between hypertensive and normotensive patients at all times measured (Figure 1 and Table 1). Beta-blockers, use was associated with a decrease in SBP was observed throughout the intervention, falling markedly in T3, with a very different pattern in T2–T3 (p = 0.096). Taking ACEIS or BETA did not show significant differences within the case group in the SBP means or at the different measurement times. In the case of calcium antagonists, ACEIs and diuretics, the SBP values were seen to decrease during the intervention, while higher pressures were recorded with similar values at T2 and T3, followed by a decrease at T4. The administration of more than two cartridges was seen to increase SBP between cases and controls.

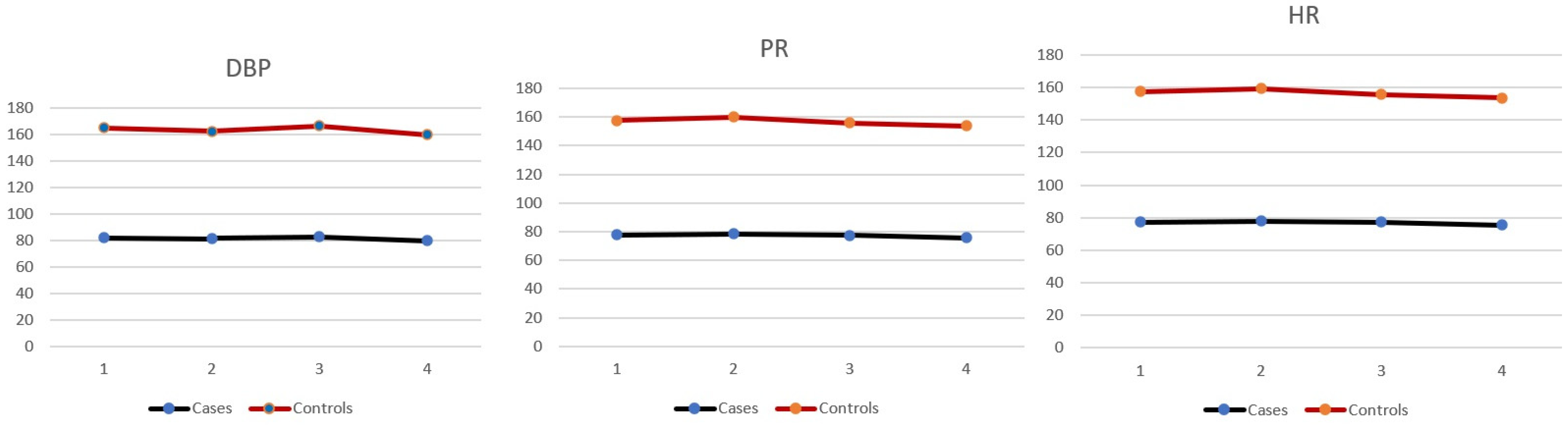

DBP remained stable with beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, ACE inhibitors, diuretics, and vasodilators, whereas treatment with ARBs was associated with a decrease in DBP between T1 and T3. However, patients receiving ARBs had higher DBP values (p: 0.048), related to the injection of more than two carpels. DBP values were lower in older individuals, over 68 years of age. The exception was hypertensive patients treated with ARBs, in whom blood pressure decreased, but without clinical implications. When comparing the average DBP values between cases and controls, there were significant differences in the T2 measurement (Figure 2 and Table 1).

Figure 2.

Evolution of hemodynamic variables that did not show statistically significant differences between cases and controls (DBP, diastolic blood pressure, PR, pulse rate and HR, heart rate).

3.2. SO2

Pulse oximetry revealed a progressive decrease in SO2 from T1 to T3, with an increase in T4 in both groups and higher SO2 values in the controls (Figure 1). In the presence of gastrointestinal disorders, the decrease in SO2 between T1 and T2 was less pronounced (Figure 1 and Table 1). SO2 levels were very similar during the intervention in all antihypertensive drug groups. Likewise, regarding the evolution of SO2 with the different antihypertensive drug combinations, no changes were recorded during the study period (p = 0.303) in any of the 8 combination groups; the type of medication did not result in significantly different SO2 values (p = 0.864). There were significant differences at all measurement times between cases and controls and between T1 and T4 of cases with AICES vs. BETA (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of the mean values of hemodynamic variables between patients receiving ACEIS and BETA across the different time points analyzed.

3.3. PR

Patients receiving beta-blockers alone showed a gradual decrease in PR, as did those receiving beta-blockers combined with diuretics, although to a lesser extent. In contrast, patients receiving beta-blockers with ACE inhibitors or beta-blockers with ARBs and diuretics showed a slight upward trend in PR. In turn, PR gradually decreased during treatment, with a pattern similar to that observed in the control group, with no significant differences within the groups, but differences between cases and controls (Table 1). An increase in PR was observed after the injection and a subsequent decrease (T3 and T4) to values even lower than those recorded at baseline. Statistically significant differences were only found at T2 between cases and controls (Table 1).

3.4. HR

Regarding HR, the control group reached a peak at T2, followed by a gradual decline, while hypertensive patients experienced virtually no changes (Table 1). It was observed that the local anesthetic with 4% articaine and 1:200,000 epinephrine CV for tooth extraction in patients with controlled hypertension may induce a slight increase in HR, although this increase is not clinically relevant. With the use of a single antihypertensive drug (calcium channel blockers, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or diuretics), an increase in HR was observed up to T2, followed by a gradual decline (p: 0.003; 0.099; 0.004; 0.004; 0.011, respectively) (Table 2), presenting a pattern identical to that observed in the control group. The use of vasodilators was associated with a decrease in HR in all cases. A statistically significant difference was found at T1 and T2 between cases and controls (Table 1).

In all the antihypertensive drug groups, the presence of endocrine disease was associated with an increased in HR, and this effect was at baseline before surgery and 5 min after the injection of the local anesthetic with vasodilators use during the intervention (Figure 2 and Table 1). Lastly, and in line with findings described above, the evolution of HR with the different antihypertensive drug combination showed no changes during the study interval (p = 0.225) in any of the 8 combination groups considered.

4. Discussion

The results of the present study showed that the local anesthetic in the form of 4% articaine with epinephrine 1:200,000 as VC used for dental extraction in patients with controlled arterial hypertensive can induce a slight increase in HR, as also reported by other authors [7,8,9], while a reactive increase in HR was observed in the control group after injection of the anesthetic with VC, followed by normalization upon completion of dental extraction. The observed stability in the hypertensive group is attributable to antihypertensive drugs, through inhibition of the effects of angiotensin, with readjustment of the baroreflex function in response to changes in arterial wall pressure and an increase in parasympathetic activity [10,11,12,13]. This is consistent with the findings of studies involving the use of ACEIs or ARA II agents [14]. Other studies have reported that HR and cortisol concentration show no significant differences between hypertensive patients and individual [15].

SBP was slightly elevated in the hypertensive group compared to controls after LA injection, and decreased minimally at the end of tooth extraction, in coincidence with the findings of other authors [16], while in the control group SBP was found to be more stable, as observed in previous studies [17,18]. DBP increased slightly throughout the intervention in both groups. The only patients in whom DBP decreased from T1 to T3 were those receiving ARA II drugs, with the administration of one or two cartridges.

This could be associated with simple dental extractions, because single-rooted teeth or teeth with mobility were involved in these cases, while in more complex extractions (e.g., molars), which require more LA, an increase in DBP was observed when the number of cartridges increased from two to three, resulting in higher DBP values from the beginning of dental treatment to the end of dental extraction.

This decrease in DBP in patients receiving ARA II drugs-observed with the minimum amount of LA with VC could be due to a mechanism of action involved, since they exert a competitive and selective blockade of the AT1 receptors, which do not modify the vasoconstriction produced by vasopressin, nor the vasodilatation produced by bradykinin, as occurs with the use of ACEIs.

Angiotensin II receptor antagonists act directly upon the kidney, inducing afferent arteriole vasodilatation does not modify the glomerular filtration rate. They also normalize noradrenergic tone, an effect that can be accompanied by circulating catecholamine levels decrease [19].

In turn, we found that SO2 decreased throughout dental extraction overall. This decrease was more evident in individuals with previous respiratory disease, as reported in other studies [17,20]. This phenomenon may be associated with a certain degree of hypoventilation caused by the semi-supine position of the patient and by air subtraction produced by powerful aspiration.

On the other hand, patients with hypertension showed no changes in SO2 with the use of beta-blockers or vasodilators, and SO2 remained stable throughout treatment.

However, certain changes were observed depending on the combination of antihypertensive drugs. Thus, patients receiving ARA II agents with diuretics, or calcium antagonists combined with ARA II agents and diuretics, experienced an increase in PR after the injection of LA with CV, followed by rapid recovery and stabilization at baseline values. Patients receiving beta-blockers with ACEIs or beta-blockers with ARA II agents and diuretics tended to show an increase in PR, whereas patients treated with beta-blockers alone tended to present lower PR levels.

According to Agani et al. [15], changes observed in patients during tooth extraction procedures may be attributed to procedural stress. In their study, a significant increase in systolic and diastolic blood pressure was observed in both hypertensive and normotensive patients, regardless of the type of anesthesia used, with or without vasoconstrictor, during tooth extraction. Particular emphasis was placed on hypertensive patients, in whom these changes were more pronounced. Regarding cortisol levels and HR, our results indicate no statistically significant differences between groups, in agreement with previous findings [15,16,17,18].

Regarding the limitations of this study, it is worth highlighting the wide variety of drugs prescribed for the treatment of high blood pressure, as well as the combinations of these drugs, which makes it difficult to unify results. However, to address this bias, cases and controls were compared and homogeneous groups were created, generating an analysis of relative effects. Furthermore, a comprehensive clinical history was taken, and vital signs were accurately monitored, facilitating patient follow-up.

Another relevant factor is the type of tooth extracted during dental exodontia, which may be associated with different postoperative complications and increased surgical duration; however, to minimize these variations, only one simple dental extraction without surgical procedures were included, all of which were completed within a single appointment lasting no more than one hour.

From a clinical perspective, the use of up to two cartridges of local anesthetic containing epinephrine appears to be safe in patients with controlled hypertension. Although transient fluctuations in hemodynamic parameters were observed—particularly in systolic blood pressure and oxygen saturation—these changes were not clinically significant in the study population. These findings highlight the importance of continuous monitoring of patients before, during, and after dental extractions to ensure safe and effective clinical management [21,22,23].

Management should be individualized in patients receiving combinations of more than two medications or those with polypharmacy for other medical conditions, particularly when medications that may affect hemodynamic variables are involved (e.g., diuretics, sedatives, antiarrhythmics, hypnotics) [22,23,24,25].

5. Conclusions

The hemodynamic parameters SBP, DBP, and SO2 showed non-significant changes throughout the dental extraction procedure in patients receiving antihypertensive drugs. In addition, and depending on the level of patient anxiety, changes in hemodynamic parameters may be masked during the extraction, so the dentist should record the pre-treatment values and ensure correct management of the hypertensive patient during the treatment and in terms of the use of AL with VC up to a maximum of three cartridges with controlled arterial hypertension. Studies with a randomized controlled design are necessary to further investigate this topic.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by F.J.S., C.F.M.-A., J.S.-R. and B.G.-L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the local Research Ethics Committee (date 29 March 2018, code:82/17) and was carried out in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki on medical research in humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Stomatology Service at the Dr. Peset University Hospital of Valencia for their collaboration in the administrative procedures.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACEIs | Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors |

| ARAII | The most common agiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors |

| DBP | Diastolic blood pressure |

| LA | Local anesthesia |

| HR | Heart rate |

| SBP | Systolic blood pressure |

| SO2 | Oxygen saturation |

| VAs | Vasoconstrictors |

References

- Balasubramaniyan, N.; Rayapati, D.; Puttiah, R.; Tavane, P.; Singh, S.; Rangan, V. Evaluation of anxiety induced cardiovascular response in known hypertensive patients undergoing prospective study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2016, 10, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancia, G.; De Backer, G.; Dominiczak, A.F.; Cifkova, R.; Fagard, R.; Germano, G.; Grassi, G.; Heagerty, A.M.; Kjeldsen, S.E.; Laurent, S.; et al. Guías de práctica clínica para el tratamiento de la hipertensión arterial 2007. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2007, 60, 968–994. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, H.; Svensson, M.; Bergh, H. The cost-effectiveness of a two-step blood pressure screening programme in a dental health-care setting. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Padial, L.; Segura Fragoso, A.; Alonso Moreno, F.J.; Arias, M.A.; Villarín Castro, A.; Rodríguez Roca, G.C. Impacto de la guía de HTA en la frecuencia y la necesidad de tratamiento de la hipertensión arterial. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2019, 72, 677–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shobha, E.S.; Anagha, M.D.; Rangan, V.; Raj, Y.N.; Patil, M.; Ramnarayan, B.K. Evaluation of Anxiety-Induced Hemodynamics Response in Known Hypertensive Patients Undergoing Surgical Removal of Impacted Mandibular Third Molar Surgery: An Observational Study. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2025, 17, S1817–S1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Özmen, E.E.; Taşdemir, İ. Evaluation of the effect of dental anxiety on vital signs in the order of third molar extraction. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mancia, G.; Fagard, R.; Narkiewicz, K.; Redon, J.; Zanchetti, A.; Bohm, M.; Christiaens, T.; Cifkova, R.; De Backer, G.; Dominiczak, A.; et al. Guía de práctica clínica de la ESH/ESC 2013 para el manejo de la hipertensión arterial. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2013, 66, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragulat, E. Tratamiento farmacológico de la hipertensión arterial: Fármacos antihipertensivos. Med. Integral 2001, 37, 215–221. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, J.M.; Lizaranzu, M.C.N.; Rodríguez, D.C.; Flores, J.G. ¿Por qué se le tiene miedo al dentista?: Estudio descriptivo de la posición de los pacientes de la Sanidad Pública en relación a diferentes factores subyacentes a los miedos dentales. RCOE Rev. Ilustre Cons. Gen. Col. Odontólogos Estomatólogos España 2004, 9, 165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Konukoglu, D.; Uzun, H. Endothelial dysfunction and hypertension. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 956, 511–540. [Google Scholar]

- Uzeda, M.J.; Moura, B.; Louro, R.S.; Da Silva, L.E.; Calasans-Maia, M.D. A randomized controlled clinical trial to evaluate blood pressure changes in patients undergoing extraction under local anesthesia with vasopressor use. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2014, 25, 1108–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronzo, A.L.; Cardoso, C.G.; Ortega, K.C.; Mion, D. Felypressin increases blood pressure during dental procedures in hypertensive patients. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2012, 99, 724–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galván, L.; Jáuregui-Renaud, K.; Márquez, M.F.; Hermosillo, A.G.; Cárdenas, M. Efecto de la inhibición de la acción de la angiotensina sobre la respuesta al ortostatismo en pacientes con hipertensión arterial sistémica. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2002, 55, 1137–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guasti, L.; Petrozzino, M.R.; Mainardi, L.T.; Grimoldi, P.; Zanotta, D.; Garganico, D.; Diolisi, A.; Simoni, C.; Grandi, A.M.; Gaudio, G.; et al. Autonomic function and baroreflex sensitivity during angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition or angiotensin II AT-1 receptor blockade in essential hypertensive patients. Acta Cardiol. 2001, 56, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agani, Z.B.; Benedetti, A.; Krasniqi, V.H.; Ahmedi, J.; Sejfija, Z.; Loxha, M.P.; Murtezani, A.; Rexhepi, A.N.; Ibraimi, Z. Cortisol level and hemodynamic changes during tooth extraction at hypertensive and normotensive patients. Med. Arch. 2015, 69, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Mostafa, N.; Aldawssary, A.; Assari, A.; Alnujaidy, S.; Almutlaq, A. A prospective randomized clinical trial compared the effect of various types of local anesthetics cartridges on hypertensive patients during dental extraction. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2015, 7, e84–e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvestre, F.J.; Martinez-Herrera, M.; García-López, B.; Silvestre-Rangil, J. Influencia de la ansiedad y los vasoconstrictores en los parámetros hemodinámicos durante los procedimientos dentales en pacientes hipertensos y no hipertensos controlados. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2021, 13, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Aguilar, J.; Guillén, I.; Sanz, M.T.; Jovani-Sancho, M. La ansiedad dental preoperatoria del paciente está relacionada con la presión arterial diastólica y la necesidad de analgesia postoperatoria. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9717. [Google Scholar]

- Tamargo, J.; Caballero, R.; Gómez, R.; Nuñez, L.; Vaquero, M.; Delpón, E. Características farmacológicas de los ARA-II. ¿Son todos iguales? Rev. Española Cardiol. Supl. 2006, 6, 10C–24C. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padma, R.; Goel, S.; Shriniwas, M.; Shreedhara, A.; Malagi, S.; Radhika, B. Evaluación comparativa de los niveles de saturación de oxígeno mediante puliometría durante la terapia periodontal no quirúrgica y quirúrgica en pacientes con periodontitis crónica. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2012, 13, 661–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Z.; Liu, D.; Wang, T.; Wang, H.; Pan, J. Benefits and risks of sleep medication in individuals with hypertension and sleep disturbance: Evidence from a large population-based study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2025, 25, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xiao, F.; Xu, L.Q.; Yan, H.Y.; Zhou, S.; Fan, J.M.; Liu, L. Comparison of Hemodynamic Status with Three Different Doses of Lidocaine as an Adjunct to Propofol-Remifentanil During Endotracheal Intubation in Elderly Female Patients: A Prospective Randomized Study. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2025, 19, 6461–6468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, D.; Li, S.; Zhang, R. Effects of dental anxiety and anesthesia on vital signs during tooth extraction. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kumar, S.; Ram, H.; Atam, I.; Atam, V.; Sonkar, S.K.; Patel, M.L.; Kumar, A. Detection of undiagnosed and inadequately treated high blood pressure in dentistry by screening. Natl. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 11, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ouchi, K.; Jinnouchi, A. Calcium channel blockers, angiotensin II receptor antagonists and alpha-blockers accentuate blood pressure reducing caused by dental local anesthesia. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021, 25, 4879–4886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.