Head-to-Head: AI and Human Workflows for Single-Unit Crown Design—Systematic Review

Abstract

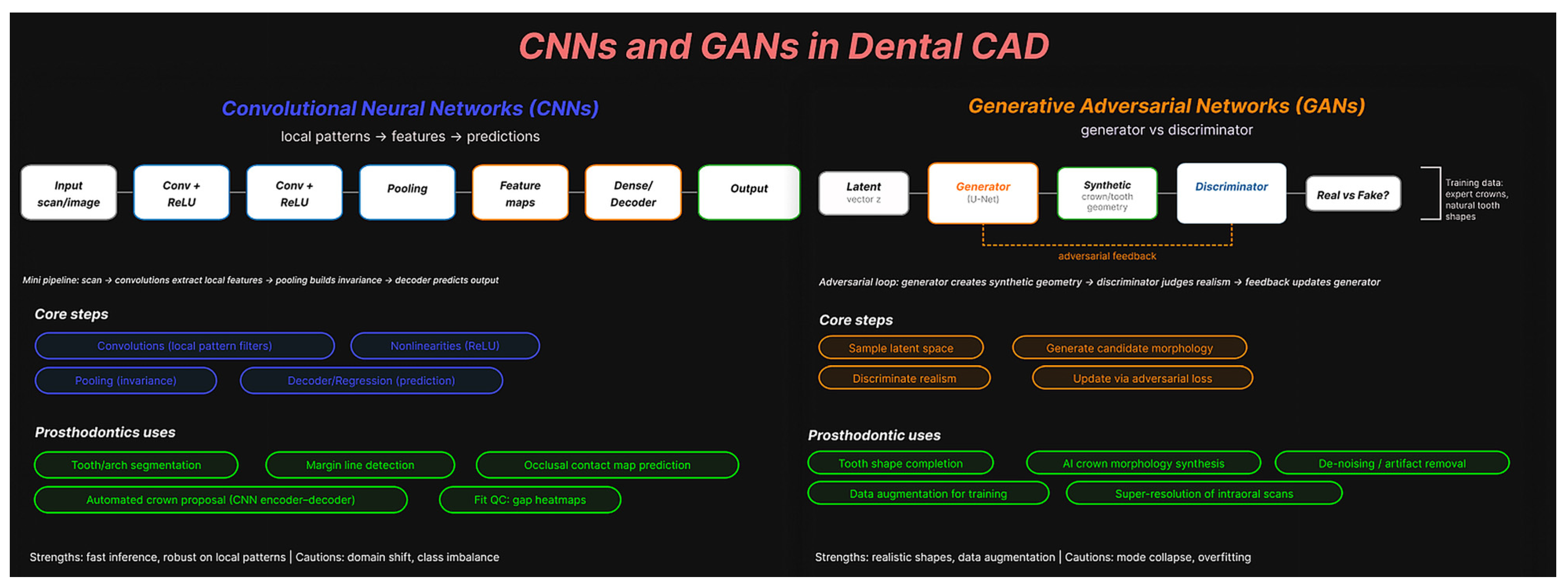

1. Introduction

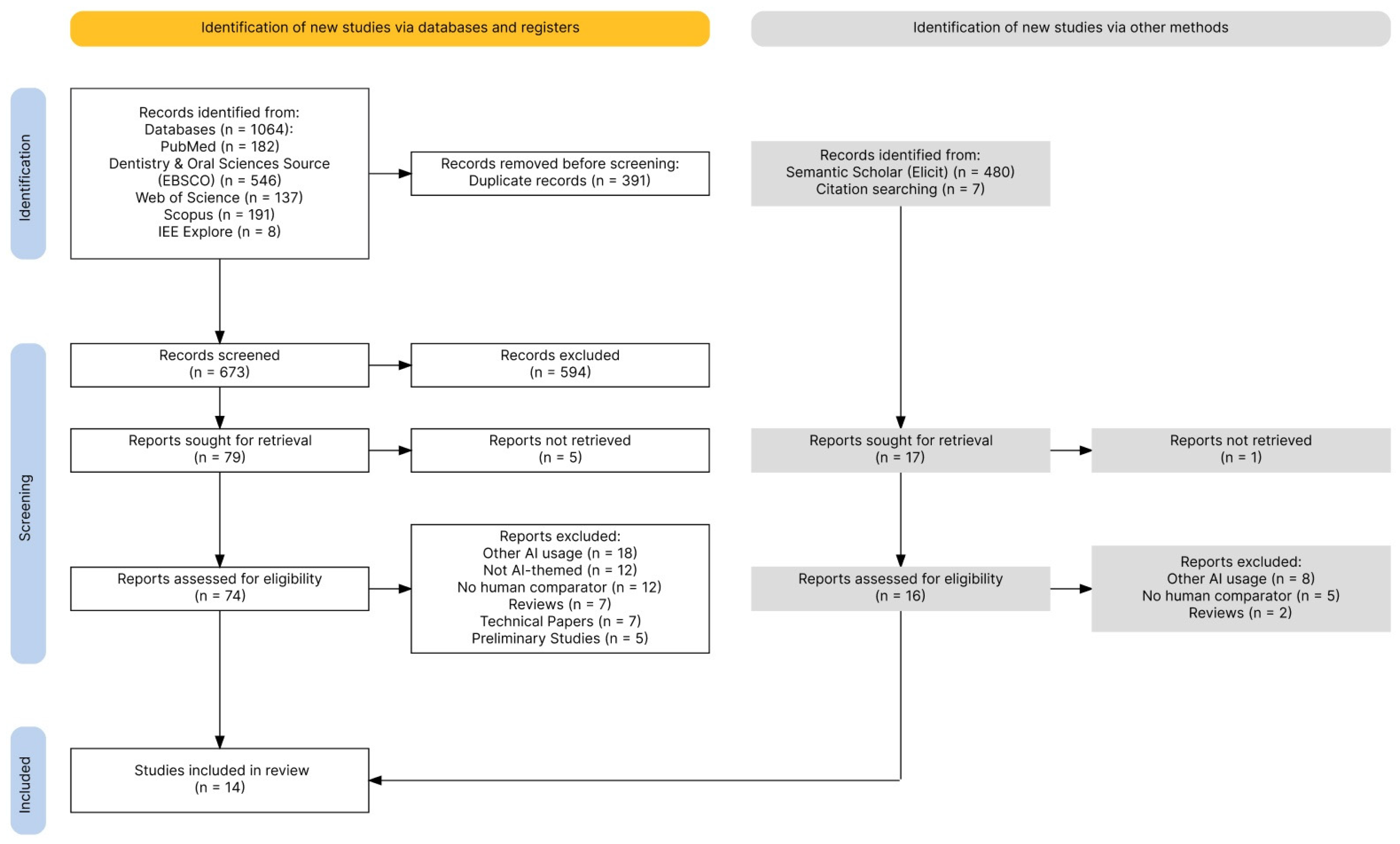

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. PICO Process Design

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Data Collection Process

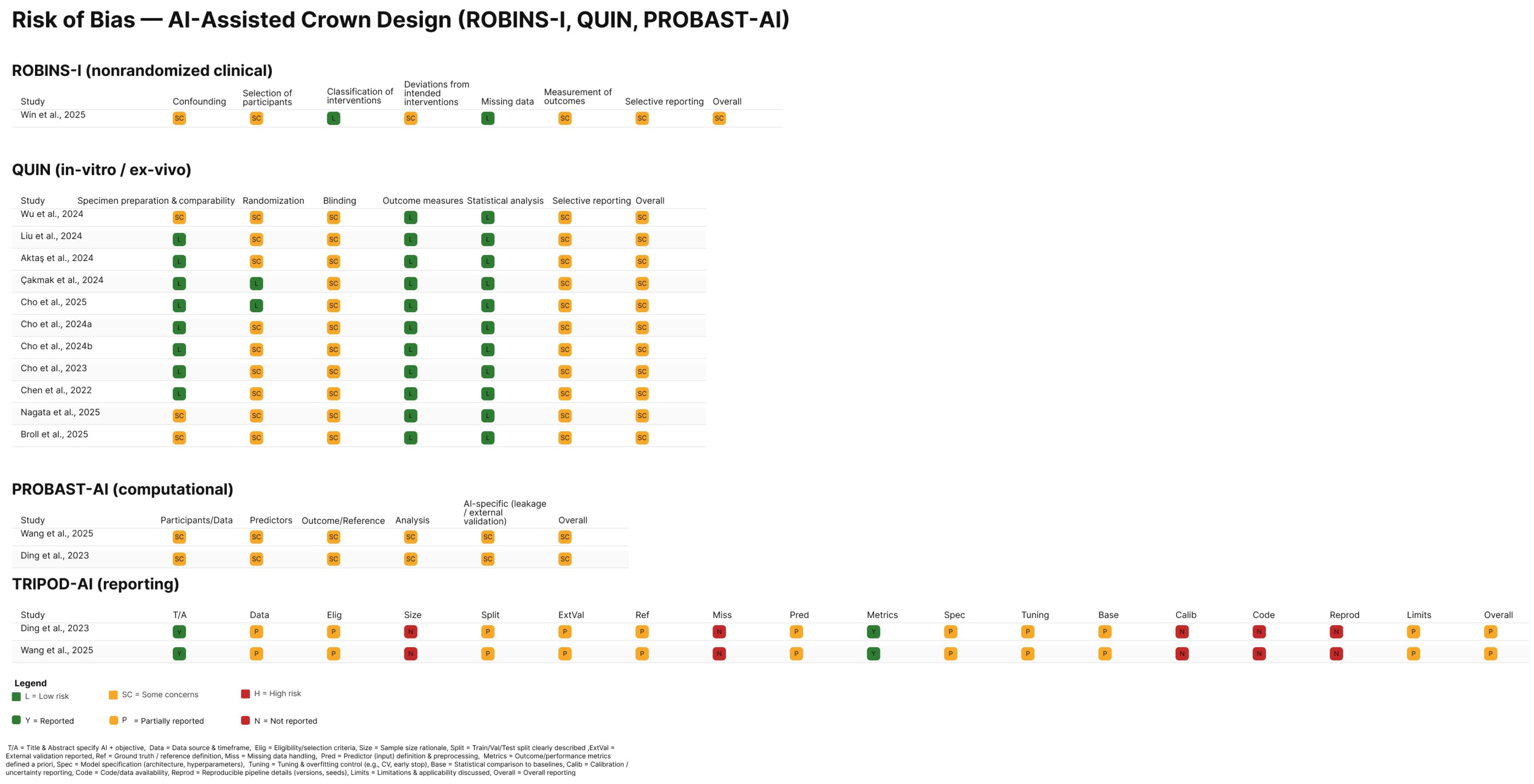

2.4. Risk of Bias and Reporting-Quality Appraisal

2.5. Evidence Synthesis and Handling of Heterogeneity

2.6. Reviewers and Use of Automation and AI-Assisted Tools

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

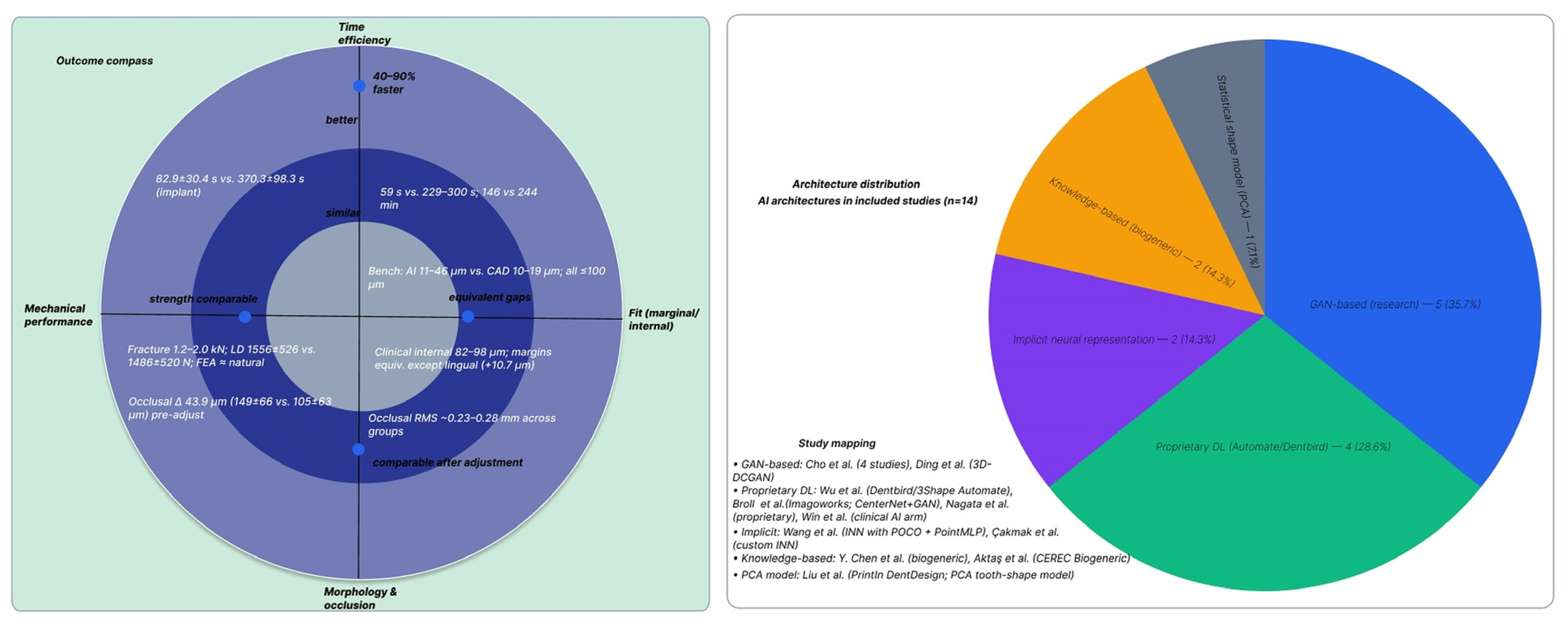

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Risk of Bias in Included Studies

3.4. Morphological and Occlusal Accuracy Outcomes

3.4.1. Morphological Accuracy

3.4.2. Occlusal Accuracy and Contacts

3.4.3. Marginal and Internal Fit Outcomes

3.5. Mechanical Performance Outcomes

3.5.1. Fracture Resistance

3.5.2. Fatigue Performance and Failure Endurance

3.6. Time Efficiency Outcomes

3.7. Chairside Adjustments

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Main Findings

4.2. Robustness of Evidence and Key Considerations

4.3. Comparison with Existing Literature

4.4. Limitations of the Review

4.5. Clinical Implications

4.6. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AA | 3Shape Automate AI group |

| AD | Dentbird AI group |

| AI | artificial intelligence |

| CAD | computer-aided design |

| CAD/CAM | computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing |

| CE | conventional experienced (technician) |

| CNN | convolutional neural network |

| CN | conventional novice (technician) |

| CT | computed tomography |

| CEREC Biogeneric | knowledge-based morphology library (Dentsply Sirona) |

| DB | Dentbird as-generated (no technician edits) |

| DL | deep learning |

| DM | Dentbird after brief technician optimization |

| FE | finite element |

| FPD | fixed partial denture |

| GAID | generative AI-assisted design |

| GAN | generative adversarial network |

| IG | internal gap |

| INN | implicit neural network |

| IoU | intersection over union |

| IOS | intraoral scanner |

| ISC | implant-supported crown |

| MG | marginal gap |

| ML | machine learning |

| N/A | not available |

| NC | non-AI comparator (experienced technician digital CAD) |

| NS | not significant |

| PCA | principal component analysis |

| p | p-value |

| POCO | point-convolution operator |

| PointMLP | point-cloud multilayer perceptron branch |

| PICO | Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PROBAST-AI | Prediction model Risk Of Bias ASsessment Tool—AI extension |

| QC | quality control |

| QUIN | Quality Assessment Tool for In Vitro Studies |

| RCTs | randomized controlled trials |

| ReLU | rectified linear unit |

| RMS | root-mean-square (deviation) |

| SD | standard deviation |

| StyleGAN | style-based generator |

| T-Scan | computerized occlusal analysis system |

| U-Net | encoder–decoder CNN with skip connections |

| μm | micrometers |

| |dev| | absolute deviation |

| exp. tech | experienced technician |

| z | latent noise vector |

| 3D-DCGAN | 3D deep convolutional GAN |

References

- Bernauer, S.A.; Zitzmann, N.U.; Joda, T. The Use and Performance of Artificial Intelligence in Prosthodontics: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2021, 21, 6628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Huang, Y.; He, J.; Chen, K.; Wang, W.; Li, X. Automatic restoration and reconstruction of defective tooth based on deep learning technology. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljulayfi, I.S.; Almatrafi, A.H.; Althubaitiy, R.O.; Alnafisah, F.; Alshehri, K.; Alzahrani, B.; Gufran, K. The Potential of Artificial Intelligence in Prosthodontics: A Comprehensive Review. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2024, 30, e944310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, H.N.; Win, T.T.; Kim, H.S.; Pae, A.; Att, W.; Nguyen, D.D.; Lee, D.H. Deep learning and explainable artificial intelligence for investigating dental professionals’ satisfaction with CAD software performance. J. Prosthodont. 2025, 34, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rokaya, D.; Jaghsi, A.A.; Jagtap, R.; Srimaneepong, V. Artificial intelligence in dentistry and dental biomaterials. Front. Dent. Med. 2025, 5, 1525505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, H.-J.; Kim, Y.-L. Accuracy of Artificial Intelligence-Designed Dental Crowns: A Scoping Review of In-Vitro Studies. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeslam, H.E.; Freifrau von Maltzahn, N.; Nassar, H.M. Revolutionizing CAD/CAM-based restorative dental processes and materials with artificial intelligence: A concise narrative review. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjumand, B. The Application of artificial intelligence in restorative Dentistry: A narrative review of current research. Saudi Dent. J. 2024, 36, 835–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, M.; Perieanu, V.S.; Burlibașa, M.; Vorovenci, A.; Malița, M.A.; Petri, D.-C.; Ștețiu, A.A.; Costea, R.C.; Costea, R.M.; Burlibașa, A.; et al. Comparative Cost-Effectiveness of Resin 3D Printing Protocols in Dental Prosthodontics: A Systematic Review. Prosthesis 2025, 7, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghauli, M.; Aljohani, W.; Almutairi, S.; Aljohani, R.; Alqutaibi, A. Advancements in digital data acquisition and CAD technology in Dentistry: Innovation, clinical Impact, and promising integration of artificial intelligence. Clin. Ehealth 2025, 8, 32–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najeeb, M.; Islam, S. Artificial intelligence (AI) in restorative dentistry: Current trends and future prospects. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlaing, N.; Çakmak, G.; Karasan, D.; Kim, S.J.; Sailer, I.; Lee, J.H. Artificial Intelligence-Driven Automated Design of Anterior and Posterior Crowns Under Diverse Occlusal Scenarios. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. Off. Publ. Am. Acad. Esthet. Dent. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Șerbănescu, C.M.; Perieanu, V.Ș.; Malița, M.A.; David, M.; Burlibașa, M.; Vorovenci, A.; Ionescu, C.; Costea, R.C.; Eftene, O.; Stănescu, R.; et al. Nanofeatured Titanium Surfaces for Dental Implants: A Systematic Evaluation of Osseointegration. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albano, D.; Galiano, V.; Basile, M.; Di Luca, F.; Gitto, S.; Messina, C.; Cagetti, M.G.; Del Fabbro, M.; Tartaglia, G.M.; Sconfienza, L.M. Artificial intelligence for radiographic imaging detection of caries lesions: A systematic review. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baena-de la Iglesia, T.; Navarro-Fraile, E.; Iglesias-Linares, A. Validation of an AI-aided 3D method for enhanced volumetric quantification of external root resorption in orthodontics. Angle Orthod. 2025, 95, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iosif, L.; Țâncu, A.M.C.; Amza, O.E.; Gheorghe, G.F.; Dimitriu, B.; Imre, M. AI in Prosthodontics: A Narrative Review Bridging Established Knowledge and Innovation Gaps Across Regions and Emerging Frontiers. Prosthesis 2024, 6, 1281–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnik, A.P.; Chhajer, H.; Venkatesh, S.B. Transforming Prosthodontics and oral implantology using robotics and artificial intelligence. Front. Oral Health 2024, 5, 1442100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsheghri, A.; Zhang, Y.; Ghadiri, F.; Keren, J.; Cheriet, F.; Guibault, F. Mesh-based segmentation for automated margin line generation on incisors receiving crown treatment. Math. Comput. Simul. 2026, 239, 716–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, N.; Chertov, S.; Jafarov, R.; Karavan, Y.; Belikov, O. The use of CAD/CAM technologies in minimally invasive dental restorations: A systematic review. Rom. J. Oral Rehabil. 2025, 17, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Wu, J.; Zhao, W.; Matinlinna, J.P.; Burrow, M.F.; Tsoi, J.K.H. Artificial intelligence in dentistry—A review. Front. Dent. Med. 2023, 4, 1085251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Win, T.T.; Mai, H.N.; Rana, S.; Kim, H.S.; Pae, A.; Hong, S.J.; Lee, Y.; Lee, D.H. User experience of and satisfaction with comput-er-aided design software when designing dental prostheses: A multicenter survey study. Int. J. Comput. Dent. 2025, 28, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Ye, X.; Dai, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, W.; Zheng, Y. Comparison of the Efficacy of Artificial Intelligence-Powered Software in Crown Design: An In Vitro Study. Int. Dent. J. 2025, 75, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawangsri, K.; Bekkali, M.; Lutz, N.; Alrashed, S.; Hsieh, Y.-L.; Lai, Y.-C.; Arreaza, C.; Nassani, L.M.; Hammoudeh, H.S. Acceptability and deviation of finish line detection and restoration contour design in single-unit crown: Comparative evaluation between 2 AI-based CAD software programs and dental laboratory technicians. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2025, 134, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheth, V.H.; Shah, N.P.; Jain, R.; Bhanushali, N.; Bhatnagar, V. Development and validation of a risk-of-bias tool for assessing in vitro studies conducted in dentistry: The QUIN. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2024, 131, 1038–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moons, K.G.M.; Damen, J.A.A.; Kaul, T.; Hooft, L.; Andaur Navarro, C.; Dhiman, P.; Beam, A.L.; Van Calster, B.; Celi, L.A.; Denaxas, S.; et al. PROBAST+AI: An updated quality, risk of bias, and applicability assessment tool for prediction models using regression or artificial intelligence methods. BMJ 2025, 388, e082505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, G.S.; Moons, K.G.M.; Dhiman, P.; Riley, R.D.; Beam, A.L.; Van Calster, B.; Ghassemi, M.; Liu, X.; Reitsma, J.B.; van Smeden, M.; et al. TRIPOD+AI statement: Updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods. BMJ 2024, 385, e078378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.H.; Yi, Y.; Choi, J.; Ahn, J.; Yoon, H.I.; Yilmaz, B. Time efficiency, occlusal morphology, and internal fit of anatomic contour crowns designed by dental software powered by generative adversarial network: A comparative study. J. Dent. 2023, 138, 104739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.H.; Çakmak, G.; Yi, Y.; Yoon, H.I.; Yilmaz, B.; Schimmel, M. Tooth morphology, internal fit, occlusion and proximal contacts of dental crowns designed by deep learning-based dental software: A comparative study. J. Dent. 2024, 141, 104830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, J.H.; Çakmak, G.; Choi, J.; Lee, D.; Yoon, H.I.; Yilmaz, B.; Schimmel, M. Deep learning-designed implant-supported posterior crowns: Assessing time efficiency, tooth morphology, emergence profile, occlusion, and proximal contacts. J. Dent. 2024, 147, 105142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, J.H.; Çakmak, G.; Jee, E.B.; Yoon, H.I.; Yilmaz, B.; Schimmel, M. A comparison between commercially available artificial intelligence-based and conventional human expert-based digital workflows for designing anterior crowns. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagata, K.; Inoue, E.; Nakashizu, T.; Seimiya, K.; Atsumi, M.; Kimoto, K.; Kuroda, S.; Hoshi, N. Verification of the accuracy and design time of crowns designed with artificial intelligence. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2025, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broll, A.; Hahnel, S.; Goldhacker, M.; Rossel, J.; Schmidt, M.; Rosentritt, M. Influence of digital crown design software on morphology, occlusal characteristics, fracture force and marginal fit. Dent. Mater. 2025, 42, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Li, N.; Lin, W.S.; Tan, J.; Chen, L. Feasibility and accuracy of single maxillary molar designed by an implicit neural network (INN)-based model: A comparative study. J. Prosthodont. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakmak, G.; Cho, J.H.; Choi, J.; Yoon, H.I.; Yilmaz, B.; Schimmel, M. Can deep learning-designed anterior tooth-borne crown fulfill morphologic, aesthetic, and functional criteria in clinical practice? J. Dent. 2024, 150, 105368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-M.; Lin, W.-C.; Lee, S.-Y. Evaluation of the efficiency, trueness, and clinical application of novel artificial intelligence design for dental crown prostheses. Dent. Mater. 2024, 40, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lee, J.K.Y.; Kwong, G.; Pow, E.H.N.; Tsoi, J.K.H. Morphology and fracture behavior of lithium disilicate dental crowns designed by human and knowledge-based AI. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2022, 131, 105256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktaş, N.; Bani, M.; Ocak, M.; Bankoğlu Güngör, M. Effects of design software program and manufacturing method on the marginal and internal adaptation of esthetic crowns for primary teeth: A microcomputed tomography evaluation. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2024, 131, 519.e1–519.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Cui, Z.; Maghami, E.; Chen, Y.; Matinlinna, J.P.; Pow, E.H.N.; Fok, A.S.L.; Burrow, M.F.; Wang, W.; Tsoi, J.K.H. Morphology and mechanical performance of dental crown designed by 3D-DCGAN. Dent. Mater. 2023, 39, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Win, T.T.; Mai, H.-N.; Kim, S.-Y.; Cho, S.-H.; Kim, J.-E.; Srimaneepong, V.; Kaenploy, J.; Lee, D.-H. Fit accuracy of complete crowns fabricated by generative artificial intelligence design: A comparative clinical study. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2025, 17, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcov, E.-C.; Burlibașa, M.; Marcov, N.; Căminișteanu, F.; Ștețiu, A.A.; Popescu, M.; Costea, R.-C.; Costea, R.M.; Burlibașa, L.; Drăguș, A.C.; et al. The Evaluation of Restored Proximal Contact Areas with Four Direct Adherent Biomaterials: An In Vitro Study. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rokhshad, R.; Khosravi, K.; Motie, P.; Sadeghi, T.S.; Tehrani, A.M.; Zarbakhsh, A.; Revilla-León, M. Deep learning applications in prosthodontics: A systematic review. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joda, T.; Balmer, M.; Jung, R.E.; Ioannidis, A. Clinical use of digital applications for diagnostic and treatment planning in prosthodontics: A scoping review. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2024, 35, 782–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broll, A.; Goldhacker, M.; Hahnel, S.; Rosentritt, M. Generative deep learning approaches for the design of dental restorations: A narrative review. J. Dent. 2024, 145, 104988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaraj, A.; Nagai, T.; AlQallaf, H.; Lin, W.S. Race to the Moon or the Bottom? Applications, Performance, and Ethical Considerations of Artificial Intelligence in Prosthodontics and Implant Dentistry. Dent. J. 2024, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangde, P.; Kale Pisulkar, S.; Beri, A.; Das, P. Comparative evaluation of marginal and internal fit of zirconia crown designed using artifical intelligence and CAD-CAM software: A systematic review. Int. Arab J. Dent. 2025, 16, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, S.; Rana, M.; Chakraborty, A.; Majumder, S.; Roy, S.; RoyChowdhury, A.; Datta, S. Design of patient specific basal dental implant using Finite Element method and Artificial Neural Network technique. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part H J. Eng. Med. 2022, 236, 1375–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, M.; Malița, M.; Vorovenci, A.; Ștețiu, A.A.; Perieanu, V.Ș.; Costea, R.C.; David, M.; Costea, R.M.; Ștețiu, M.A.; Drăguș, A.C.; et al. Wet vs. Dry Dentin Bonding: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Adhesive Performance and Hybrid Layer Integrity. Oral 2025, 5, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Definition for This Review | Inclusion Decision (Yes/No Questions) | Data Items |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | (i) Clinical adults requiring single-unit indirect restorations (crowns, inlays, onlays, overlays) on teeth or implant abutments; (ii) Ex vivo/in silico standardized models of prepared teeth/abutments. | P1. Clinical adults and/or standardized ex vivo/in silico models? P2. Single-unit restoration (not multi-unit/FPD)? P3. Tooth-borne or implant-supported within scope? | Study context (clinical/ex vivo/in silico); tooth/abutment type and location; prep features (finish line, reduction, taper); scanner model and software/version; scan resolution/point density. |

| Intervention | AI-generated/AI-assisted design from digital scans (e.g., convolutional neural network (CNN)/generative adversarial network (GAN)/transformer or another ML pipeline; fully automated or human-in-the-loop). | I1. Is the restoration designed by AI (not only detection/segmentation)? I2. Digital input used (IOS/lab scan/CT)? | AI type; training status and dataset size/source; automation level; target parameters (cement space μm, min thickness mm, contact targets); library/prior; post-processing; software/version; hardware; inference time; total design time (AI). |

| Comparator | Expert human CAD/CAM or non-AI (rule/library-based) CAD workflow. | C1. Is there a non-AI comparator (human or rule/library CAD)? | Comparator type; software/version; designer expertise; internal gap (IG; cement space) (μm); min thickness (mm); total design time (comparator). |

| Outcomes—Clinical fit and chairside | Marginal/internal fit; adjustment burden; contact quality; short follow-up. | O1. Report marginal and/or internal fit? O2. Report clinical adjustment time/remakes/contact metrics? | Marginal gap (mean/SD/n, μm, method/timepoint); internal gap (μm); chairside adjustment time (min); remakes (n); occlusal contacts (articulating/T-Scan metrics incl. center of force, % balance); proximal contacts (shimstock/feeler). |

| Outcomes—Technical accuracy | Geometric/morphological accuracy of the designed restoration against a reference. | O3. Report at least one technical accuracy metric? (Any of: trueness/precision root-mean-square (RMS); 95th-pct/max | |dev| |

| Timepoints/Follow-up | Immediate design outputs; try-in; cementation; short-term clinical follow-up if available. | T1. Are timepoints stated (pre-cementation/after cementation/follow-up)? | Timepoint per outcome; follow-up (months); attrition. |

| Study designs (S) (added for completeness) | RCTs, non-randomized comparative clinical, prospective/retrospective cohorts, comparative ex vivo or in silico. | S1. Comparative design? S2. Not a review/editorial/case report only? | Design and setting; unit of analysis; groups/arms and n; power calc; ethics (or NA). |

| Exclusions | Out of scope. | X1. Segmentation/detection/classification without design; X2. No eligible comparator; X3. Not single-unit prosthodontic design; X4. No eligible outcomes; X5. Duplicate/overlap without unique data; X6. Non-extractable full text/language. | Record explicit exclusion code and rationale. |

| Database/Platform | Syntax/Search String Used | Fields Searched | Limits/Filters |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed (MEDLINE) | (“Artificial Intelligence”[mh] OR “Machine Learning”[mh] OR “Deep Learning”[mh] OR “Neural Networks, Computer”[mh] OR “generative adversarial network”[tiab] OR GAN[tiab] OR “diffusion model”[tiab] OR “variational autoencoder”[tiab] OR VAE[tiab] OR transformer[tiab] OR transformers[tiab] OR “convolutional neural network”[tiab] OR CNN[tiab] OR “deep learning”[tiab] OR “machine learning”[tiab]) AND (“Dental Prosthesis Design”[mh] OR “Computer-Aided Design”[mh] OR “Crowns”[mh] OR “Inlays”[mh] OR “Veneers”[mh] OR crown[tiab] OR crowns[tiab] OR inlay[tiab] OR inlays[tiab] OR onlay[tiab] OR onlays[tiab] OR veneer[tiab] OR veneers[tiab] OR endocrown[tiab] OR endocrowns[tiab] OR bridge[tiab] OR bridges[tiab] OR “fixed partial denture”[tiab] OR “fixed partial dentures”[tiab] OR “fixed dental prosthesis”[tiab] OR “fixed dental prostheses”[tiab]) AND (design[tiab] OR designs[tiab] OR “restoration design”[tiab] OR generate[tiab] OR generative[tiab] OR generation[tiab] OR reconstruct[tiab] OR reconstruction[tiab]) AND (“Dentistry”[mh] OR “Prosthodontics”[mh] OR dental[tiab] OR prosthodontic[tiab] OR prosthodontics[tiab]) | MeSH + Title/Abstract | Years: 2016–2025; Language: English; Article types: Journal Article, Review (exclude letters/editorials). |

| Scopus (Elsevier) | TITLE-ABS-KEY(“deep learning” OR “machine learning” OR “convolutional neural network” OR CNN OR “generative adversarial network” OR GAN OR “diffusion model” OR “variational autoencoder” OR VAE OR transformer OR transformers) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(crown OR crowns OR inlay OR inlays OR onlay OR onlays OR veneer OR veneers OR endocrown OR endocrowns OR “fixed partial denture” OR “fixed partial dentures” OR “fixed dental prosthesis” OR “fixed dental prostheses” OR bridge OR bridges OR pontic OR pontics) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(design OR designs OR “restoration design” OR generate OR generative OR reconstruction OR reconstruct) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(dental OR dentistry OR prosthodontic OR prosthodontics) | TITLE, ABSTRACT, KEYWORDS | Years: 2016–2025; Language: English; Document type: Article OR Review (exclude conference papers); Subject area: Dentistry. |

| EBSCOhost—Dentistry and Oral Sciences Source | TI,AB(“deep learning” OR “machine learning” OR “convolutional neural network” OR CNN OR “generative adversarial network” OR GAN OR “diffusion model” OR “variational autoencoder” OR VAE OR transformer OR transformers) AND TI,AB(crown OR crowns OR inlay OR inlays OR onlay OR onlays OR veneer OR veneers OR endocrown OR endocrowns OR “fixed partial denture” OR “fixed dental prosthesis” OR “fixed dental prostheses” OR bridge OR bridges OR pontic OR pontics) AND TI(design OR designs OR “restoration design”) AND SU(dentistry OR prosthodontics) | Title, Abstract, Subject Headings (SU) | Database: Dentistry and Oral Sciences Source; Source type: Academic Journals; Peer-reviewed; Language: English; Years: 2016–2025. |

| IEEE Xplore (IEEE) | (“deep learning” OR “machine learning” OR “convolutional neural network” OR CNN OR GAN OR “diffusion model”) AND dental AND (crown OR bridge OR “fixed partial denture” OR “fixed dental prosthesis” OR inlay OR onlay OR veneer OR endocrown) | Metadata (Title/Abstract/Author Keywords/Index Terms) | Content type: Journals and Early Access; Years: 2016–2025; Language: English. |

| Elicit (Semantic Scholar) | Keyword query (three-concept block): dentistry/prosthodontics + AI/ML/generative + restoration/design. Example: dental OR prosthodontics AND (deep learning OR machine learning OR convolutional neural network OR GAN OR diffusion model OR variational autoencoder) AND (crown OR inlay OR onlay OR veneer OR endocrown OR fixed dental prosthesis OR bridge) AND (design OR generation). Elicit converts to keywords and queries the Semantic Scholar corpus; use Elicit’s UI filters. | Title/Abstract from Semantic Scholar corpus; full text when Elicit provides it | Years: 2016–2025; Language: English; At screening: peer-reviewed journals; de-duplicated against database exports. |

| Study (Year) | Study Design | Restoration | Human Comparator | AI System (Vendor) | AI Technology Type (From Study) | Fit and Accuracy (MG/IG, RMS, etc.) | Time/Efficiency | Clinical/Functional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cho et al., 2023 [30] | Laboratory/ex vivo | Tooth-supported posterior crowns | NC: 3Shape Dental System (ET) | Dentbird Crown (Imagoworks) | CenterNet-based CNN (tooth detection/margins) + pSp encoder + StyleGAN generator (GAN) | Internal gap RMS AI better than technician CAD (p < 0.001); occlusal morphology deviation lower with AI | AI faster; ~60 s reduction at final step | Occlusion/contacts comparable to NC; fewer post-design modifications with AI |

| Cho et al., 2024a [31] | Laboratory/ex vivo | Posterior crowns | NC: 3Shape Dental System (ET) | 3Shape Automate (3Shape) and Dentbird (Imagoworks) | Automate: proprietary cloud DL (architecture N/A). Dentbird: CenterNet + pSp + StyleGAN | Internal fit: AD ≈ NC > AA (platform effect); morphology similar; contacts more favorable with NC | AD 82.9 ± 30.4 s vs. NC 370.3 ± 98.3 s | Fully automatic AI designs (no tech edits) evaluated vs. NC criteria |

| Cho et al., 2024b [32] | Laboratory/ex vivo | Single implant-supported posterior crowns (ISC) | NC: 3Shape (ET); DM: tech-optimized AI | Dentbird (Imagoworks)—DB (as-generated) and DM (with brief tech optimization) | CenterNet + pSp + StyleGAN-based DL stack | Morphology/volume deviation: DM < DB; emergence profile and functional metrics similar across groups; MG/IG N/A | DB fastest (exact times N/A) | Some contours benefited from limited technician optimization (DM) |

| Cho et al., 2025 [33] | Computational/Lab | Maxillary central incisor crowns | ET CAD design | Dentbird (Imagoworks) and 3Shape Automate (3Shape) | Dentbird: CenterNet + pSp + StyleGAN; Automate: proprietary (architecture N/A) | Esthetics and guidance non-inferior to expert designs; MG/IG N/A | N/A | Anterior guidance and esthetic proportions satisfied by AI designs |

| Wu et al., 2025 [22] | Laboratory/in vitro | Posterior crowns | ET and NT: Exocad DentalCAD | Automate (standalone) and Dentbird (web) | Dentbird: GAN + CNN; Automate: proprietary (architecture N/A) | RMS (median) Occlusal: AA 228.3 μm, AD 281.3 μm, CE 228.6 μm, CN 233.5 μm; Distal: CE best; margin line: no significant difference | AI 146 min vs. CE 244 min; Conventional 584 min | AI boosts efficiency; experienced tech still best on some occlusal/distal sites |

| Nagata et al., 2025 [34] | Laboratory/ex vivo (typodonts #15, #26) | Premolar and molar crowns | 5 ETs (3–32 yr) on 3Shape | Dentbird (Imagoworks) | Commercial DL platform (CenterNet + GAN modules; exact phrasing varies) | Marginal gap < 120 μm for AI and CAD; selected occlusal points AI 25.7 ± 13 μm vs. CAD 275.5 ± 116.8 μm | AI significantly faster (quantitative time N/A) | Margins comparable; AI favored at specific occlusal sites |

| Broll et al., 2025 [35] | Laboratory/ex vivo | Posterior crowns | ET (Exocad) | Automate (3Shape); Dentbird (Imagoworks) | Vendor systems as above (Automate architecture N/A; Dentbird CenterNet + StyleGAN) | Vertical MG 223–293 μm across AI and technician/CAD groups (NS) | N/A | Technician often best morphology; function and fracture loads comparable |

| Wang et al., 2025 [36] | Computational (in silico) | Maxillary first molar | ET | Custom INN model (research) | Implicit Neural Network with POCO point-conv + PointMLP local branch (trained on ~500 arches) | RMS AI 0.2839 ± 0.0307 mm vs. Tech 0.3026 ± 0.0587 mm (p = 0.202, NS) | N/A | Recommends adding clinically relevant metrics beyond RMS |

| Çakmak et al., 2024 [37] | Computational/Lab | Maxillary central incisor crowns | NC: Exocad 3.1 (ET); DM: tech-optimized AI | Dentbird (Imagoworks) | GAN + CNN (CenterNet + StyleGAN via pSp) | Esthetics similar; incisal path deviation higher with raw AI; length/inclination similar; MG/IG N/A | N/A | Tech tweaks (DM) improve palatal guidance without harming labial esthetics |

| Liu et al., 2024 [38] | Laboratory/ex vivo | Crowns and inlays | Manual digital and manual wax-up | PrintIn DentDesign (PrintIn Co., Taipei) | Statistical ML (PCA tooth-shape model) | MG AI 11.3–45.6 μm; Digital 10.4–18.8 μm; Wax-up 66.0–79.8 μm; AI/digital ≪ wax-up (p < 0.05) | AI 58–60 s; Digital 229–300 s; Wax-up 263–600 s | Trueness comparable AI vs. digital; both superior to wax-up |

| Chen et al., 2022 [39] | Laboratory/ex vivo | Lithium-disilicate crowns | ET and students (NT) | CEREC Biogeneric (Dentsply Sirona) | Knowledge-based library (biogeneric morphology) | MG/IG N/A (fit not primary); morphology deviation lower in human CAD; fracture behavior acceptable both | N/A | AI showed more restorable substrate damage upon failure |

| Aktaş et al., 2024 [40] | Laboratory/ex vivo | Primary molar crowns | ET (Exocad) | Dentbird (Imagoworks) | Commercial DL (Dentbird CenterNet + StyleGAN family) | MG ~54 ± 43 μm (AI-3D-printed best axial); CAD-milled best marginal; software × manufacturing interaction p = 0.004 | N/A | All groups within clinical limits |

| Ding et al., 2023 [41] | Computational (in silico) | Premolar crowns | ET CAD and CEREC Biogeneric | 3D-DCGAN (research) | 3D deep convolutional GAN | Morphology closest to natural tooth; favorable FE stress; MG/IG N/A | N/A | Occlusal contacts broadly similar across groups |

| Win et al., 2025 [42] | Clinical | Single complete interim crowns | Exocad DentalCAD 3.0 Galway ET (≥10-yr tech) | Dentbird Crown v3.x.x (Imagoworks)—web-based GAID | Commercial generative AI system; underlying architecture in this paper N/A | IG ~82–98 μm (NS AI vs. CAD); marginal gaps equivalent overall; lingual margin AI worse | N/A | Real-patient trial; occlusal contact discrepancy larger with AI but within limits |

| TRIPOD-AI Item (Figure 3 Abbreviation; Pragmatic Mapping) | Ding et al., 2023 [41] | Wang et al., 2025 [36] |

|---|---|---|

| T/A—Title/Abstract identifies AI model development + target task | Y (explicit aim to develop a true 3D AI algorithm for crown design). | Y (explicit feasibility aim to develop an INN model for automatic molar reconstruction/crown design). |

| Data—Data source/setting/timeframe described | P (data source and acquisition are described, but representativeness and dataset spectrum beyond “healthy personnel” is limited). | P (data source described; single-institution retrospective database; limited spectrum beyond defined criteria). |

| Elig—Eligibility/selection criteria reported | P (case description is provided, but eligibility is broad and limited to “healthy personnel” without granular criteria). | Y/P (explicit inclusion/exclusion criteria are provided, but scope is narrow to intact maxillary first molars and “desirable” morphology). |

| Size—Sample size rationale/justification | N (dataset size stated, but no justification/power rationale for model development). | P (power statement provided for RMS comparisons, but not a full model-development sample size justification). |

| Split—Train/validation/test partitioning described | P (mentions 12 additional test cases; no explicit validation strategy and limited leakage safeguards). | Y (explicit train/validation/test split ratio 7:1.5:1.5 and rationale stated). |

| ExtVal—External validation | N (only internal hold-out testing is described; no independent external dataset). | N (internal split only; no independent external validation dataset/site). |

| Ref—Reference standard/ground truth definition | P (comparators and reference natural tooth are described for evaluation, but “ground truth” for generation and reference justification are limited). | Y (original clinical crowns are isolated and used as the comparison reference for generated crowns). |

| Miss—Missing data handling | N (not described). | N (not described). |

| Pred—Predictors/inputs + preprocessing described | P (inputs and manual segmentation described; limited reproducibility detail on standardization). | P (processed arch creation and smoothing described; still limited detail on operator variability and repeatability). |

| Metrics—Performance metrics defined and reported | Y (explicit metrics including cusp angle, RMS/3D similarity, occlusal contact, and FEA-based outputs). | Y (CD, F-score, volumetric IoU, RMS deviations, plus deviation maps and statistical testing). |

| Spec—Model specification (architecture/pipeline) described | Y (generator/discriminator layer structure, filters, kernel/stride/padding, activations, BN, LeakyReLU slope). | Y (two-branch architecture described; POCO-only vs. POCO-PointMLP and training workflow described). |

| Tuning—Hyperparameter tuning/overfitting control | P (states multiple parameters were investigated; does not clearly report final selected hyperparameters or selection protocol). | P (uses validation set and reports training/validation curves; tuning process and selection criteria not fully formalized). |

| Base—Comparator/baseline clearly specified | Y (explicit comparison against natural tooth, biogeneric, and technician CAD). | Y (explicit comparison vs. technician-designed crowns and original clinical crowns). |

| Calib—Calibration/uncertainty estimates | N (not reported). | N (not reported). |

| Code—Code/weights/data availability | N (no code/weights/dataset access reported). | N (no code/weights/dataset access reported). |

| Reprod—Reproducibility assets (versions/seeds) | N (not reported). | N (not reported). |

| Limits—Limitations/applicability discussed | P (limitations and scope are discussed, but not in a TRIPOD-AI structured way). | P (limitations noted; acknowledges metric limitations and restricted tooth-type training data). |

| Overall—Overall reporting completeness | P (strong architecture/metrics; weaker eligibility granularity, split/validation structure, and reproducibility assets). | P (clear dataset criteria and splits/metrics; no external validation and no reproducibility assets). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Vorovenci, A.; Perieanu, V.Ș.; Burlibașa, M.; Gligor, M.R.; Malița, M.A.; David, M.; Ionescu, C.; Stănescu, R.; Ionaș, M.; Costea, R.C.; et al. Head-to-Head: AI and Human Workflows for Single-Unit Crown Design—Systematic Review. Oral 2026, 6, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral6010016

Vorovenci A, Perieanu VȘ, Burlibașa M, Gligor MR, Malița MA, David M, Ionescu C, Stănescu R, Ionaș M, Costea RC, et al. Head-to-Head: AI and Human Workflows for Single-Unit Crown Design—Systematic Review. Oral. 2026; 6(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral6010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleVorovenci, Andrei, Viorel Ștefan Perieanu, Mihai Burlibașa, Mihaela Romanița Gligor, Mădălina Adriana Malița, Mihai David, Camelia Ionescu, Ruxandra Stănescu, Mona Ionaș, Radu Cătălin Costea, and et al. 2026. "Head-to-Head: AI and Human Workflows for Single-Unit Crown Design—Systematic Review" Oral 6, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral6010016

APA StyleVorovenci, A., Perieanu, V. Ș., Burlibașa, M., Gligor, M. R., Malița, M. A., David, M., Ionescu, C., Stănescu, R., Ionaș, M., Costea, R. C., Eftene, O., Șerbănescu, C. M., Popescu, M., & Drăguș, A. C. (2026). Head-to-Head: AI and Human Workflows for Single-Unit Crown Design—Systematic Review. Oral, 6(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral6010016