Abstract

Background/Objectives: Despite decades of technological progress, the diagnosis of dental caries still depends largely on subjective, operator-dependent assessment, leading to inconsistent detection of early lesions and delayed intervention. Artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a transformative approach capable of standardizing diagnostic performance and, in some cases, surpassing human accuracy. This scoping review critically synthesizes the current evidence on AI for caries detection and examines its true translational readiness for clinical practice. Methods: A comprehensive literature search was conducted in PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science (WoS), covering studies published from January 2019 to June 2024, in accordance with PRISMA-ScR guidelines. Eligible studies included original research evaluating the use of AI for dental caries detection, published in English or Spanish. Review articles, editorials, opinion papers, and studies unrelated to caries detection were excluded. Two reviewers independently screened, extracted, and charted data on imaging modality, sample characteristics, AI architecture, validation approach, and diagnostic performance metrics. Extracted data were summarized narratively and comparatively across studies using tabulated and graphical formats. Results: Thirty studies were included from an initial pool of 617 records. Most studies employed convolutional neural network (CNN)-based architectures and reported strong diagnostic performance, although these results come mainly from experimental settings and should be interpreted with caution. Bitewing radiography dominated the evidence base, reflecting technological maturity and greater reproducibility compared with other imaging modalities. Conclusions: Although the reported metrics are technically robust, the current evidence remains insufficient for real-world clinical adoption. Most models were trained on small, single-source datasets that do not reflect clinical diversity, and only a few underwent external or multicenter validation. Until these translational and methodological gaps are addressed, AI for caries detection should be regarded as promising yet not fully clinically reliable. By outlining these gaps and emerging opportunities, this review offers readers a concise overview of the current landscape and the key steps needed to advance AI toward meaningful clinical implementation.

1. Introduction

Dental caries remains a major public health problem in Chile, affecting 73.9% of 15-year-olds and 99.2% of adults aged 35 to 44 years [1]. Traditionally, its detection and diagnosis have been based on conventional methods such as visual inspection [2], dental probing [3], and radiographic imaging [3]. Although these approaches remain widely implemented in daily practice, they show inherent limitations in sensitivity, reproducibility, and standardization. Within this context, artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a promising technological innovation, based on algorithms capable of simulating human learning and decision-making processes [4] for the analysis of a wide range of dental images [5].

The integration of AI into dentistry has demonstrated multiple advantages, including shorter diagnostic times [5], lower error rates [6], and greater diagnostic accuracy [7]. These improvements contribute to optimized treatment planning [8], enhanced clinical efficiency [3], and the reduction in risks associated with diagnostic uncertainty [7]. More specifically, techniques such as machine learning (ML), artificial neural networks (ANN) and convolutional neural networks (CNN) have exhibited the ability to process and analyze large volumes of data with high precision [9], accelerate evaluation processes [5,10], minimize inter-professional variability [4], facilitate the early identification of incipient lesions that allow for minimally invasive interventions [11], and ultimately improve the overall efficiency of dental practice [12].

Nevertheless, despite its considerable potential, the implementation of AI in dentistry still faces significant challenges. The quality, diversity, and representativeness of training data are decisive factors, since biased or insufficient datasets may compromise the performance and generalizability of algorithms [4]. Moreover, appropriate technological infrastructure and professional training are indispensable for the effective adoption of these tools [13]. In parallel, the establishment of robust regulatory frameworks is required to promote responsible and ethical integration of AI, ensuring both patient safety and the preservation of professional standards. This context helps explain the heterogeneity observed in the existing literature, which complicates the systematic synthesis of knowledge in this emerging field.

The diversity of study designs, imaging modalities, and AI architectures in this emerging field precludes a quantitative synthesis or meta-analysis. Therefore, a scoping review approach was adopted to systematically map the extent, range, and nature of the available evidence rather than to generate pooled estimates of diagnostic performance. This design enables the identification of knowledge gaps, methodological trends, and translational barriers that can guide future research toward clinically robust and generalizable AI applications in dentistry. Addressing these challenges is needed to harness the demonstrated benefits of AI and to advance its integration into dental practice. A structured synthesis of the current literature is thus necessary to enhance the clinical applicability of AI-based diagnostic tools and contribute to the broader improvement of oral healthcare. Accordingly, this study aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the current landscape of AI applications for dental caries detection in human populations, emphasizing its potential to reshape diagnostic paradigms and strengthen evidence-based decision-making in clinical dentistry. Therefore, this scoping review addresses the following question: “Which AI-based methods have been used for dental caries detection, and what is known about their diagnostic performance and clinical readiness?” Specifically, this scoping review aims to: (i) compile and map the scientific evidence published over the past five years on AI-based tools for caries detection across different imaging modalities; (ii) compare the architectures and analytical approaches used in the development of these algorithms; (iii) examine their reported diagnostic performance and validation strategies; and (iv) identify the preprocessing methods and contextual factors that influence their applicability to real-world dental practice.

2. Materials and Methods

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [14]. Because protocol registration is not mandatory for scoping reviews, no formal protocol was submitted; instead, the study followed a predefined methodological framework to ensure transparency and reproducibility. The completed PRISMA-ScR checklist is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

The present review included academic publications and peer-reviewed scientific articles published within the last five years, indexed in PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science (WoS), and available up to June 2024. This timeframe was selected to capture the most recent developments in AI model architectures and their clinical applications while ensuring consistency during data extraction. Eligible studies were required to investigate the use of AI for the detection or classification of dental caries in humans. For clinical precision, we clarify that the review adopted the general concept of dental caries, irrespective of lesion location, as defined in the original articles. Additional inclusion criteria were full-text availability and publication in English or Spanish. In contrast, opinion pieces, editorials, review articles, and studies employing AI for educational or non-diagnostic purposes were excluded, as were articles focused primarily on periodontics, endodontics, or oral oncology.

The database search was performed in June 2024 across PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science (WoS) using standardized Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms: “Artificial Intelligence” AND “Dental Caries”. After removing duplicates, records were screened by title and abstract to identify potentially relevant studies. The remaining publications underwent full-text assessment, and those not meeting the predefined inclusion criteria or lacking full-text access were excluded.

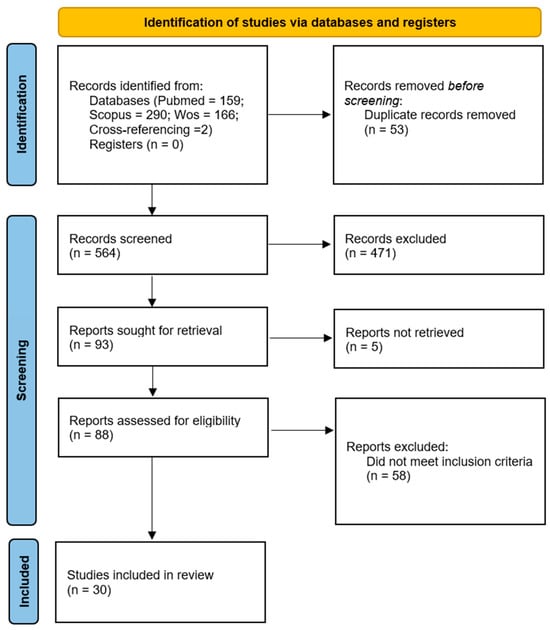

All retrieved records were imported into a reference management tool to remove duplicates before screening. The selection process occurred in two stages: (i) title and abstract screening, and (ii) full-text eligibility assessment. Two authors independently conducted both stages, resolving any discrepancies through discussion with a third reviewer. Only studies directly addressing the research question were retained for full-text review, following predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure methodological consistency. The overall selection workflow and the number of records excluded at each stage are presented in the PRISMA-ScR flow diagram (Figure 1). The final pool of studies underwent critical appraisal in accordance with the TRIPOD-AI guidelines [15], with particular emphasis on methodological rigor, ethical compliance, and the clarity and reproducibility of reported results. This framework was used to support bias control and ensure that the included studies provided transparent, reliable, and verifiable evidence regarding the development and validation of AI models. The appraisal results were not used as exclusion criteria, but rather to contextualize the narrative synthesis and identify common reporting gaps and methodological limitations across the literature.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram [14] illustrating the selection process of studies included in the systematic review, from the initial identification of 617 records to the final inclusion of 30 publications.

Data from the included studies were systematically extracted in duplicate using a standardized data charting form developed by the review team. Extracted variables included author information, year of publication, country, sample size, imaging modality, AI architecture, preprocessing methods, validation approach, and diagnostic performance metrics. In Table 1, the validation approach is presented as the number of examiners or evaluators involved in each study, reflecting the human reference standard used for comparison. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus. No contact with study authors was required, as all relevant information was available in the published articles. No data imputations were performed, and any reclassifications were based solely on the information explicitly provided in the original studies.

Table 1.

Summary of the main characteristics of the studies included in this scoping review, ordered first by year of publication and then alphabetically by the first author. The table details sample size, imaging modality, AI architecture, performance metrics, and reported outcomes. All reported scores were approximated to two decimal places for consistency.

The charted data were synthesized through a narrative and descriptive approach, consistent with the objectives of a scoping review. Studies were organized into thematic categories based on AI architecture type, imaging modality and validation strategy. Quantitative indicators such as accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and Area Under the Curve (AUC) were summarized in comparative tables and figures to highlight general performance trends rather than pooled estimates. The synthesis aimed to map the breadth of evidence, identify methodological patterns, and emphasize knowledge gaps relevant to clinical translation.

3. Results

The literature search identified 617 records, including 159 from PubMed, 290 from Scopus, and 166 from Web of Science, along with two additional studies identified through manual cross-referencing (Figure 1).

After removing duplicates, the remaining records were screened by title and abstract, and studies not meeting the inclusion criteria or lacking full-text access were excluded. This process resulted in the inclusion of 30 studies that directly addressed the review objectives.

The main characteristics and findings of the included studies are summarized in Table 1, which presents the data most relevant to the review objectives—namely, the application of AI tools for dental caries detection, the comparison of model architectures, and the analysis of diagnostic performance. Each study entry details the year of publication, country, imaging modality, dataset characteristics, preprocessing methods, AI architecture, and performance metrics, all extracted directly from the original articles to ensure accuracy and comparability. As shown in Table 1, diagnostic performance demonstrated notable variability across studies, with reported sensitivity values ranging from 0.59 to 0.95, specificity from 0.57 to 0.99, and AUC values from 0.74 to 0.96, reflecting differences in imaging modality, dataset characteristics, and model architecture. These numerical ranges offer a concise overview of the diagnostic variability observed across the evidence base.

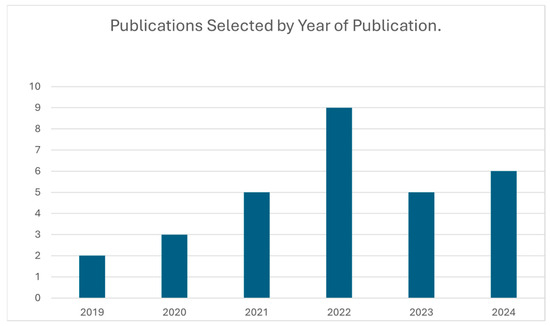

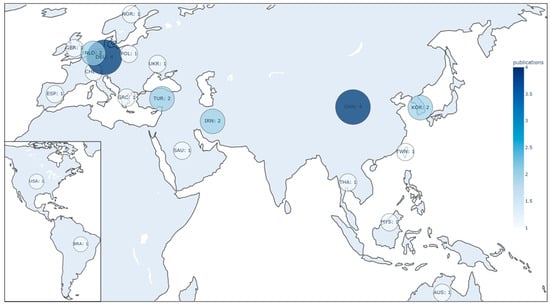

A temporal analysis revealed a steady increase in research output between 2019 and 2024, with a notable peak in 2022 (Figure 2). The geographic distribution of publications, highlighting the main contributing countries, is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

This figure illustrates the number of AI-based dental caries detection studies published each year within the review period. The trend shows a progressive increase in research activity, with a notable peak in 2022.

Figure 3.

Geographic distribution of publications by country, highlighting the regions with the highest contribution to the research field on artificial intelligence for dental caries detection.

The methodological quality of the included studies was evaluated using the TRIPOD-AI checklist, focusing on transparency, reproducibility, and risk of bias. Overall, the studies achieved an estimated 80–85% compliance with TRIPOD-AI criteria. Most publications clearly described AI architectures and validation procedures, but several recurring deficiencies were identified: (i) absence of a reliable ground truth, as most relied solely on expert consensus instead of independent histological or micro-CT verified annotations; (ii) lack of formal sample-size justification; and (iii) limited generalizability due to single-center datasets and suboptimal reporting of class imbalance. These appraisal results were not used as exclusion criteria but served to contextualize the synthesis, highlighting that the strongest models still face reproducibility and external validation gaps. Consequently, the TRIPOD-AI assessment supported the interpretative framework of this review, ensuring methodological transparency across the evidence base.

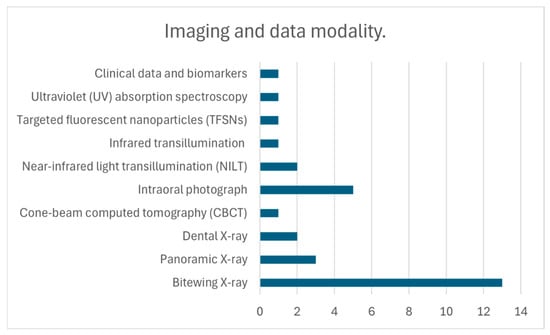

The studies included in this review assessed a wide spectrum of AI applications for dental caries detection across different imaging modalities and diagnostic techniques (Figure 4). The performance of these approaches varied depending on the type of input data, the architecture employed, and the methodological rigor of the studies. The following sections summarize the main findings by technique, emphasizing the strengths, limitations, and clinical implications of each approach.

Figure 4.

Overview of artificial intelligence applications and imaging modalities in the included studies. This figure summarizes the AI approaches, imaging modalities, and data characteristics represented in the included studies, providing a visual synthesis of their diagnostic performance, methodological features, and analytical strategies.

The analysis of intraoral photography revealed heterogeneous performance across architectures, with models such as MobileNetV2 (sensitivity 0.92; specificity 0.90) and VGG-16 (AUC 0.86; sensitivity 0.82) standing out for their accessibility and clinical potential, though their accuracy was strongly influenced by image quality [20,32,35,37]. More advanced frameworks, including Cascade R-CNN (specificity 0.96; sensitivity 0.73) and Mask R-CNN (accuracy 0.89), demonstrated higher robustness but required considerable computational resources, limiting their applicability [10]. In contrast, UV absorption spectroscopy, applied to salivary samples, achieved perfect sensitivity and specificity, highlighting its potential for noninvasive diagnosis [34].

CBCT yielded high diagnostic values (accuracy 0.95; sensitivity 0.92; specificity 0.96), though its integration into routine practice remains constrained by the high technical and resource requirements of this imaging modality [11]. Dental (periapical) radiography studies reported variable outcomes: while Faster R-CNN demonstrated moderate accuracy (0.74) with rapid processing times (0.19 s per image), Deeplabv3 achieved very high average accuracy (0.99) but poor segmentation performance (IoU mean 0.51), reflecting challenges in lesion delineation [6,33].

Emerging methods, such as TFSNs, supported by U-Net and NASNet, reported moderate diagnostic performance (sensitivity 0.80; PPV 0.76), particularly for early-stage caries [8]. In panoramic radiographs, architectures such as ResNet18 (accuracy 82.72%; sensitivity 0.85; specificity 0.88), MobileNetV2 (accuracy 0.87; specificity 0.88), and DCDNet (accuracy 0.72) showed variable but promising results for large-scale screening, with MobileNetV2 offering practical advantages for resource-limited environments [23,29,32].

NILT emerged as a radiation-free alternative, with ResNet18–ResNeXt50 combinations achieving moderate accuracy (0.69) and AUC (0.74), while U-Net with VGG-16 improved segmentation performance (mIoU 0.73). Nonetheless, the sensitivity remained relatively low (0.59), limiting its reliability despite favorable AUC values in vivo (0.78) compared to in vitro settings (0.65) [16,17,20]. Studies exploring clinical data and salivary biomarkers through neural networks also demonstrated encouraging performance, with accuracy values above 83%, reinforcing their potential role in complementary diagnosis [18].

Bitewing radiographs, the most frequently studied modality (13 publications), confirmed the versatility of deep learning architectures. U-Net models consistently reached high accuracy (0.95) and F1-scores (0.88), while AlexNet (accuracy 0.90) and VGG19 (accuracy 0.94) underscored the potential of classical CNNs [21,30,31,35]. Advanced models such as Faster R-CNN and VGG-16 reported robust metrics (accuracy 0.86; specificity 0.96; AUC 0.95), and DarkNet-53 achieved strong discriminatory power (AUC 0.96; specificity 98.18%) despite a lower sensitivity (72.26%) [7,19,25]. RetinaNet, YOLOv5, and EfficientDet applied in the HUNT4 Oral Health Study reached a mean Average Precision (mAP) of 0.65, supporting the utility of large datasets for model validation [4]. Finally, Mask R-CNN obtained consistent AUC values (>0.80) for both primary and secondary caries, with data augmentation improving sensitivity and robustness across clinical conditions [12].

Collectively, the results reveal consistent diagnostic accuracy across CNN-based architectures but also persistent limitations in dataset diversity and external validation, aspects further examined in the Discussion.

4. Discussion

This scoping review highlights a rapidly expanding research field, driven by technological progress and growing interest in clinical integration. A clear multidisciplinary effort is evident to identify the most effective AI applications through diverse imaging techniques and analytical approaches. While bitewing radiographs remain the most frequently used modality, there is an increasing trend toward exploring novel imaging technologies that enable earlier and more noninvasive detection of dental caries.

The analyzed studies underscore the transformative potential of AI, particularly CNN-based architectures, in enhancing the accuracy and efficiency of caries diagnosis. Deep learning (DL) algorithms such as U-Net, Faster R-CNN, and Mask R-CNN consistently demonstrated substantial diagnostic improvements, with U-Net achieving notably higher sensitivity (0.75) compared to dental professionals (0.36) in specific contexts. These automated systems can also differentiate between primary and secondary caries, detect incipient lesions with higher precision than conventional methods, and optimize clinical workflows by directing attention toward the most relevant regions of interest.

The premise of this scoping review regarding the ability of AI models, such as the U-Net architecture, to surpass clinical performance is validated by the literature, which consistently reports that AI enhances the accuracy and sensitivity of dentists [38,39]. For example, AI sensitivity (0.75) has been shown to be significantly higher than the average dentist sensitivity (0.36) in the detection of proximal caries on bitewings [5,38]. This improved sensitivity is particularly relevant, as AI assistance has been observed to substantially increase clinicians’ ability to identify initial or moderate lesions (the categories most easily overlooked) with significant improvements in sensitivity for these subgroups [37].

However, this high diagnostic precision must be interpreted cautiously. AI often exhibits lower sensitivity and AUC values for caries detection compared to other dental pathologies, such as residual roots or crowns, in both panoramic radiographs and CBCT [39,40]. For instance, in a multidiagnostic framework, AI achieved specificity = 0.99 but sensitivity = 0.55 for caries, with an AUC lower than that of experienced clinicians [41]. Consistent with the methodological issues identified in this review, the literature highlights the absence of a reliable ground truth, as histological or micro-CT validation was rarely performed, and most models were trained on expert consensus, introducing potential human bias [5,39,41]. Generalizability remains limited by the predominant use of single-source datasets [41]. Unlike the earlier review by Mohammad-Rahimi et al. [40], which emphasized promising yet methodologically weak evidence, our work not only applies TRIPOD-AI standards to mitigate bias but also provides clinically oriented insights into the real-world applicability of AI tools for caries detection.

Beyond the optimization described above, eye-tracking studies confirm that dentists assisted by AI demonstrate more efficient visual behavior, focusing on relevant regions (caries and restorations) in significantly less time [39]. This efficiency translates into substantial time savings, for example, one AI system for panoramic radiographs achieved an average diagnostic time of 1.5 s per image, compared with 53.8 s for human clinicians [41]. Finally, although AI enhances diagnostic precision, cost-effectiveness is achieved only when early detection enables non-restorative, minimally invasive interventions rather than an increase in invasive procedures [38].

Despite encouraging progress, clinical implementation still faces major challenges, particularly regarding the generalizability of models and variability in image quality. Addressing these issues requires the creation of large, high-quality datasets that reflect diverse clinical scenarios. Additional barriers include the transparency and explainability of AI systems (the “black box” problem), the data requirements for model training, and the need for robust ethical and regulatory frameworks to guarantee safe and effective deployment. Interdisciplinary collaboration between AI developers and dental professionals remains essential to ensure that these tools meet clinical needs and deliver practical value.

In contrast to previous reviews that examined either broad digital diagnostic aids for early caries detection [3] or focused specifically on deep-learning approaches with limited clinical interpretation (e.g., Mohammad-Rahimi et al. [40]), this scoping review provides an updated, methodologically structured synthesis that integrates architectural comparisons, preprocessing strategies, validation approaches, and translational considerations into a single framework. By emphasizing clinically relevant outcomes, dataset representativeness, and the practical barriers to implementation—including generalizability, regulatory constraints, and interpretability—this review offers a more comprehensive and clinically oriented understanding of the current landscape of AI-based caries detection. These strengths position the present work as a complementary contribution that extends beyond technical performance to address real-world applicability in dental practice.

This scoping review has limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the search was limited to three major biomedical databases (PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science) and did not include engineering or computer science repositories such as IEEE Xplore or the ACM Digital Library, which may host additional studies on algorithmic development or technical implementations of AI systems. Moreover, the use of a focused search expression (“Artificial Intelligence AND Dental Caries”) may have excluded studies employing broader terminology such as “deep learning” “machine learning,” or “neural network” which should be considered when interpreting the scope of the evidence. Second, only articles published in English or Spanish were included, potentially excluding relevant research in other languages. Third, the review covered studies published between 2019 and June 2024, which may have omitted earlier AI applications for caries detection, and given the rapidly evolving nature of AI research, additional studies have been published since June 2024. These newer publications were not incorporated to preserve methodological consistency, but their emergence highlights the need for periodic updates in this expanding field. Fourth, no quantitative synthesis or meta-analysis was conducted, as heterogeneity in datasets, imaging modalities, and outcome measures precluded statistical pooling. Finally, the design of scoping reviews inherently limits the ability to perform a formal quality or risk-of-bias assessment beyond descriptive appraisal. These constraints were mitigated through rigorous eligibility criteria, adherence to PRISMA-ScR guidelines, and a structured synthesis emphasizing methodological transparency.

The studies included in this scoping review show that AI—particularly CNN-based deep learning architectures—has considerably improved sensitivity, specificity, and reduced interobserver variability, addressing a long-standing challenge in conventional dentistry. However, despite these promising results in controlled research environments, validation in real-world clinical settings remains a key requirement. Future research should focus on the development of more robust, clinically applicable, transparent, and reproducible models, trained on large and diverse datasets. Furthermore, strengthening the interpretability of AI systems to support clinician confidence, together with the establishment of appropriate ethical and regulatory frameworks, will help facilitate their integration into routine care. In this regard, expanding multicenter validation efforts represents an important step toward improving generalizability and supporting the reliable implementation of AI-based diagnostic tools in everyday dental practice.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review systematically mapped the current evidence on AI tools for dental caries detection, encompassing 30 studies published between 2019 and 2024. The findings show that convolutional neural networks (CNNs) remain the predominant architecture for image-based caries diagnosis, achieving high diagnostic accuracy (≥90%) across multiple imaging modalities, particularly bitewing radiographs. However, substantia heterogeneity in datasets, labeling protocols, preprocessing methods, and validation strategies limits comparability and generalizability across models.

These results directly address the review objectives by identifying methodological patterns, characterizing architectural trends, and highlighting key areas for improvement in transparency and validation. Collectively, the evidence supports the technical maturity of CNN-based systems while emphasizing the urgent need for standardized datasets, open benchmarking, and multicenter clinical validation to ensure reliable real-world deployment. Future research should also align reporting practices with TRIPOD-AI and advance explainability frameworks to enhance clinician trust and promote the ethical integration of AI into dental diagnostics.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/oral5040102/s1, Table S1: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.M.R., M.R.L., M.D.A., S.N., M.F.V.D., J.J.R. and A.V.B.; methodology, P.M.R., M.R.L. and S.N.; validation, P.M.R., M.R.L., M.D.A. and S.N.; formal analysis, P.M.R., M.R.L., M.D.A., S.N., M.F.V.D., J.J.R. and A.V.B.; investigation, P.M.R., M.R.L. and M.D.A.; writing—original draft preparation, P.M.R.; writing—review and editing, P.M.R., M.R.L., M.D.A., S.N., M.F.V.D., J.J.R. and A.V.B.; project administration, P.M.R.; funding acquisition, P.M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo (ANID), Chile, through the Doctorado en Chile Scholarship Program, Academic Year 2025 (Grant No. 1340/2025).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses extension for scoping reviews |

| WoS | Web of science |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| ML | Machine learning |

| ANN | Artificial neural network |

| CNN | Convolutional neural network |

| MeSH | Medical subject headings |

| TRIPOD-AI | Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis |

| IoU | Intersection over union |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| SE | Sensitivity |

| SP | Specificity |

| PPV | Positive predictive value |

| NPV | Negative predictive value |

| NILT | Near-infrared light transillumination |

| TFSNs | Targeted fluorescent nanoparticles |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| CD | Caries detection |

| CBCT | Cone beam computed tomography |

| Micro-CT | Micro computed tomography |

| DL | Deep learning |

References

- Phillips, M.; Bernabé, E.; Mustakis, A. Radiographic assessment of proximal surface carious lesion progression in Chilean young adults. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2020, 48, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kühnisch, J.; Meyer, O.; Hesenius, M.; Hickel, R.; Gruhn, V. Caries Detection on Intraoral Images Using Artificial Intelligence. J. Dent. Res. 2022, 101, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, E.K.; Wah, Y.Y.; Lam, W.Y.; Chu, C.H.; Yu, O.Y. Use of Digital Diagnostic Aids for Initial Caries Detection: A Review. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez de Frutos, J.; Holden Helland, R.; Desai, S.; Nymoen, L.C.; Langø, T.; Remman, T.; Sen, A. AI-Dentify: Deep learning for proximal caries detection on bitewing x-ray—HUNT4 Oral Health Study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsiwala-Scheppach, L.T.; Castner, N.J.; Rohrer, C.; Mertens, S.; Kasneci, E.; Cejudo Grano de Oro, J.E.; Schwendicke, F. Impact of artificial intelligence on dentists’ gaze during caries detection: A randomized controlled trial. J. Dent. 2024, 140, 104793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Xu, T.; Peng, L.; Cao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, S.; Zhao, Y.; Meng, F.; Ding, J.; Liang, S. Faster-RCNN based intelligent detection and localization of dental caries. Displays 2022, 74, 102201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cañas, Á.; Bonfanti-Gris, M.; Paraíso-Medina, S.; Martínez-Rus, F.; Pradíes, G. Diagnosis of Interproximal Caries Lesions in Bitewing Radiographs Using a Deep Convolutional Neural Network-Based Software. Caries Res. 2022, 56, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwendicke, F.; Mertens, S.; Cantu, A.G.; Chaurasia, A.; Meyer-Lueckel, H.; Krois, J. Cost-effectiveness of AI for caries detection: Randomized trial. J. Dent. 2022, 119, 104080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panyarak, W.; Wantanajittikul, K.; Suttapak, W.; Charuakkra, A.; Prapayasatok, S. Feasibility of deep learning for dental caries classification in bitewing radiographs based on the ICCMS™ radiographic scoring system. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2023, 135, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutselos, K.; Berdouses, E.; Oulis, C.; Maglogiannis, I. Recognizing Occlusal Caries in Dental Intraoral Images Using Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 41st Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Berlin, Germany, 23–27 July 2019; pp. 1617–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilyfard, R.; Bonyadifard, H.; Paknahad, M. Dental Caries Detection and Classification in CBCT Images Using Deep Learning. Int. Dent. J. 2024, 74, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, E.T.; Vinayahalingam, S.; van Nistelrooij, N.; Xi, T.; Romero, V.H.D.; Flügge, T.; Saker, H.; Kim, A.; Lima, G.D.S.; Loomans, B.; et al. Detection of caries around restorations on bitewings using deep learning. J. Dent. 2024, 143, 104886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantu, A.G.; Gehrung, S.; Krois, J.; Chaurasia, A.; Rossi, J.G.; Gaudin, R.; Elhennawy, K.; Schwendicke, F. Detecting caries lesions of different radiographic extension on bitewings using deep learning. J. Dent. 2020, 100, 103425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, G.S.; Moons, K.G.M.; Dhiman, P.; Riley, R.D.; Beam, A.L.; Van Calster, B.; Ghassemi, M.; Liu, X.; Reitsma, J.B.; van Smeden, M.; et al. TRIPOD+AI statement: Updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods. BMJ 2024, 385, e078378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalegno, F.; Newton, T.; Daher, R.; Abdelaziz, M.; Lodi-Rizzini, A.; Schürmann, F.; Krejci, I.; Markram, H. Caries Detection with Near-Infrared Transillumination Using Deep Learning. J. Dent. Res. 2019, 98, 1227–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwendicke, F.; Elhennawy, K.; Paris, S.; Friebertshäuser, P.; Krois, J. Deep learning for caries lesion detection in near-infrared light transillumination images: A pilot study. J. Dent. 2020, 92, 103260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udod, O.A.; Voronina, H.S.; Ivchenkova, O.Y. Application of neural network technologies in the dental caries forecast. Wiad. Lek. 2020, 73, 1499–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayraktar, Y.; Ayan, E. Diagnosis of interproximal caries lesions with deep convolutional neural network in digital bitewing radiographs. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtkamp, A.; Elhennawy, K.; Cejudo Grano de Oro, J.E.; Krois, J.; Paris, S.; Schwendicke, F. Generalizability of Deep Learning Models for Caries Detection in Near-Infrared Light Transillumination Images. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.C.; Chen, T.Y.; Chou, H.S.; Lin, S.Y.; Liu, S.Y.; Chen, Y.A.; Liu, Y.L.; Chen, C.A.; Huang, Y.C.; Chen, S.L.; et al. Caries and Restoration Detection Using Bitewing Film Based on Transfer Learning with CNNs. Sensors 2021, 21, 4613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, M.; Faria, M.; Giraldi, G.; Bastos, L.; Oliveira, L.; Conci, A. Classification of Approximal Caries in Bitewing Radiographs Using Convolutional Neural Networks. Sensors 2021, 21, 5192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinayahalingam, S.; Kempers, S.; Limon, L.; Deibel, D.; Maal, T.; Hanisch, M.; Bergé, S.; Xi, T. Classification of caries in third molars on panoramic radiographs using deep learning. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Guo, J.; Ye, J.; Zhang, M.; Liang, Y. Detection of Proximal Caries Lesions on Bitewing Radiographs Using Deep Learning Method. Caries Res. 2022, 56, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estai, M.; Tennant, M.; Gebauer, D.; Brostek, A.; Vignarajan, J.; Mehdizadeh, M.; Saha, S. Evaluation of a deep learning system for automatic detection of proximal surface dental caries on bitewing radiographs. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2022, 134, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.A.; Jones, N.; Tenuta, L.M.A.; Bloembergen, W.; Flannagan, S.E.; González-Cabezas, C.; Clarkson, B.; Pan, L.C.; Lahann, J.; Bloembergen, S. Convolution Neural Networks and Targeted Fluorescent Nanoparticles to Detect and ICDAS Score Caries. Caries Res. 2022, 56, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.Y.; Cho, H.; Kang, S.; Jeong, S.; Kim, E.K. Caries detection with tooth surface segmentation on intraoral photographic images using deep learning. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liang, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, C.; Gu, D.; Sun, W.; Miao, L. Development and evaluation of deep learning for screening dental caries from oral photographs. Oral Dis. 2022, 28, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Yu, G.; Yin, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, J. Context Aware Convolutional Neural Network for Children Caries Diagnosis on Dental Panoramic Radiographs. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2022, 2022, 6029245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Azhari, A.; Fawaz, K.; Ahmed, H.; Alsadah, Z.; Majumdar, A.; Carvalho, R. Artificial intelligence in the detection and classification of dental caries. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2023, 133, 1326–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baydar, O.; Różyło-Kalinowska, I.; Futyma-Gąbka, K.; Sağlam, H. The U-Net Approaches to Evaluation of Dental Bite-Wing Radiographs: An Artificial Intelligence Study. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayı, B.; Üzen, H.; Çiçek, İ.B.; Duman, Ş.B. A Novel Deep Learning-Based Approach for Segmentation of Different Type Caries Lesions on Panoramic Radiographs. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qayyum, A.; Tahir, A.; Butt, M.A.; Luke, A.; Abbas, H.T.; Qadir, J.; Arshad, K.; Assaleh, K.; Imran, M.A.; Abbasi, Q.H. Dental caries detection using a semi-supervised learning approach. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basri, K.N.; Yazid, F.; Mohd Zain, M.N.; Md Yusof, Z.; Abdul Rani, R.; Zoolfakar, A.S. Artificial neural network and convolutional neural network for prediction of dental caries. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 312, 124063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ForouzeshFar, P.; Safaei, A.A.; Ghaderi, F.; Hashemikamangar, S.S. Dental Caries diagnosis from bitewing images using convolutional neural networks. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K.; Jeong, H.M.; Kim, J.W.; Park, J.H.; Choi, J. AI-based dental caries and tooth number detection in intraoral photos: Model development and performance evaluation. J. Dent. 2024, 141, 104821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Oh, S.I.; Jo, J.; Kang, S.; Shin, Y.; Park, J.W. Deep learning for early dental caries detection in bitewing radiographs. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwendicke, F.; Rossi, J.G.; Göstemeyer, G.; Elhennawy, K.; Cantu, A.G.; Gaudin, R.; Chaurasia, A.; Gehrung, S.; Krois, J. Cost-effectiveness of Artificial Intelligence for Proximal Caries Detection. J. Dent. Res. 2021, 100, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amasya, H.; Alkhader, M.; Serindere, G.; Futyma-Gąbka, K.; Aktuna Belgin, C.; Gusarev, M.; Ezhov, M.; Różyło-Kalinowska, I.; Önder, M.; Sanders, A.; et al. Evaluation of a Decision Support System Developed with Deep Learning Approach for Detecting Dental Caries with Cone-Beam Computed Tomography Imaging. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad-Rahimi, H.; Motamedian, S.R.; Rohban, M.H.; Krois, J.; Uribe, S.E.; Mahmoudinia, E.; Rokhshad, R.; Nadimi, M.; Schwendicke, F. Deep learning for caries detection: A systematic review. J. Dent. 2022, 122, 104115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, J.; Yu, Y.; Li, X.; Shi, K.; Zhang, F.; Yu, F.; Shi, K.; Sun, Z.; et al. Artificial intelligence in the diagnosis of dental diseases on panoramic radiographs: A preliminary study. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).