Impact of Oral and Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in Patients with Multiple Myeloma and Hematological Malignancies: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. The Oral and Gut Microbiota: An Overview

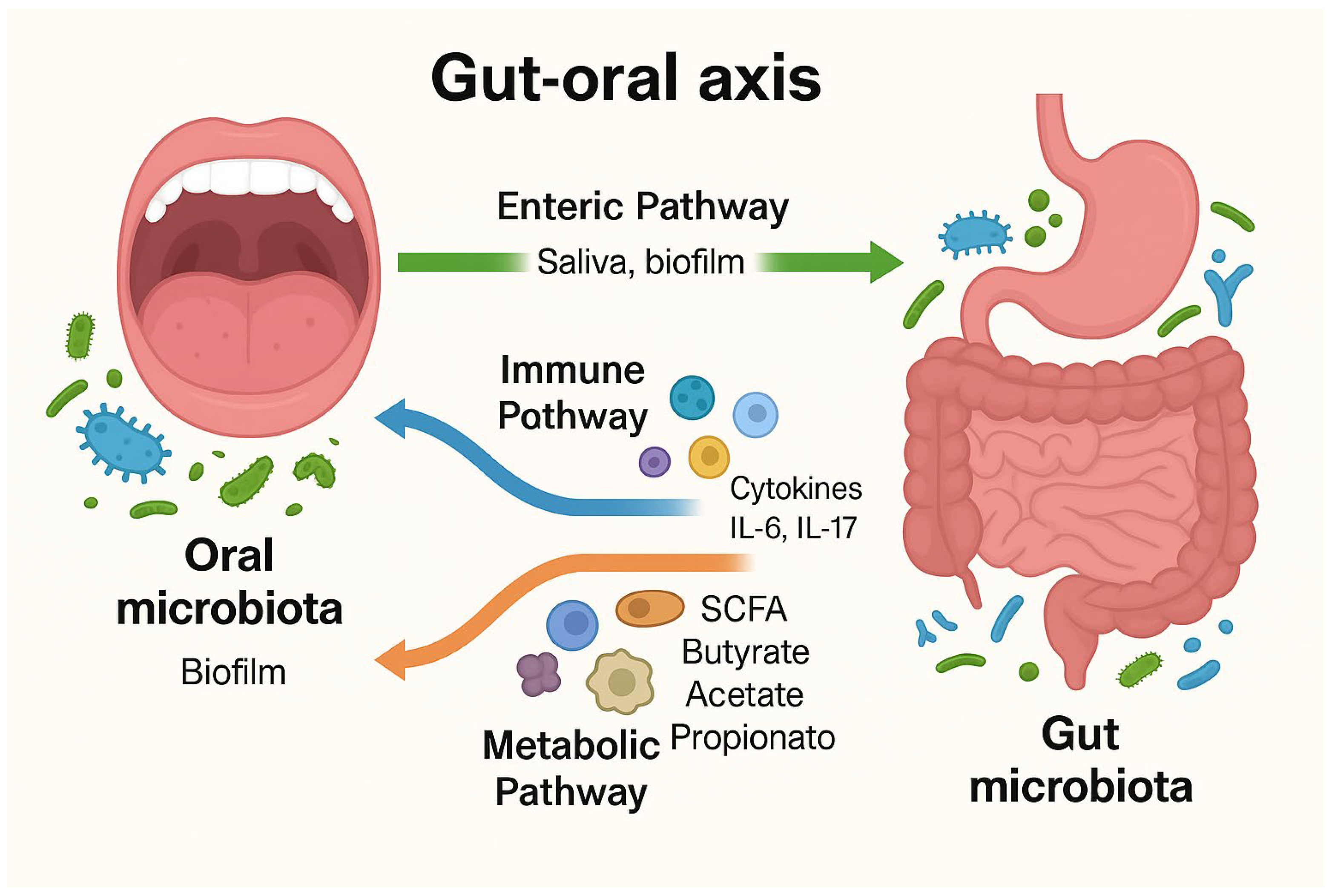

3.1. Composition and Functions of Oral and Gut Microbiota

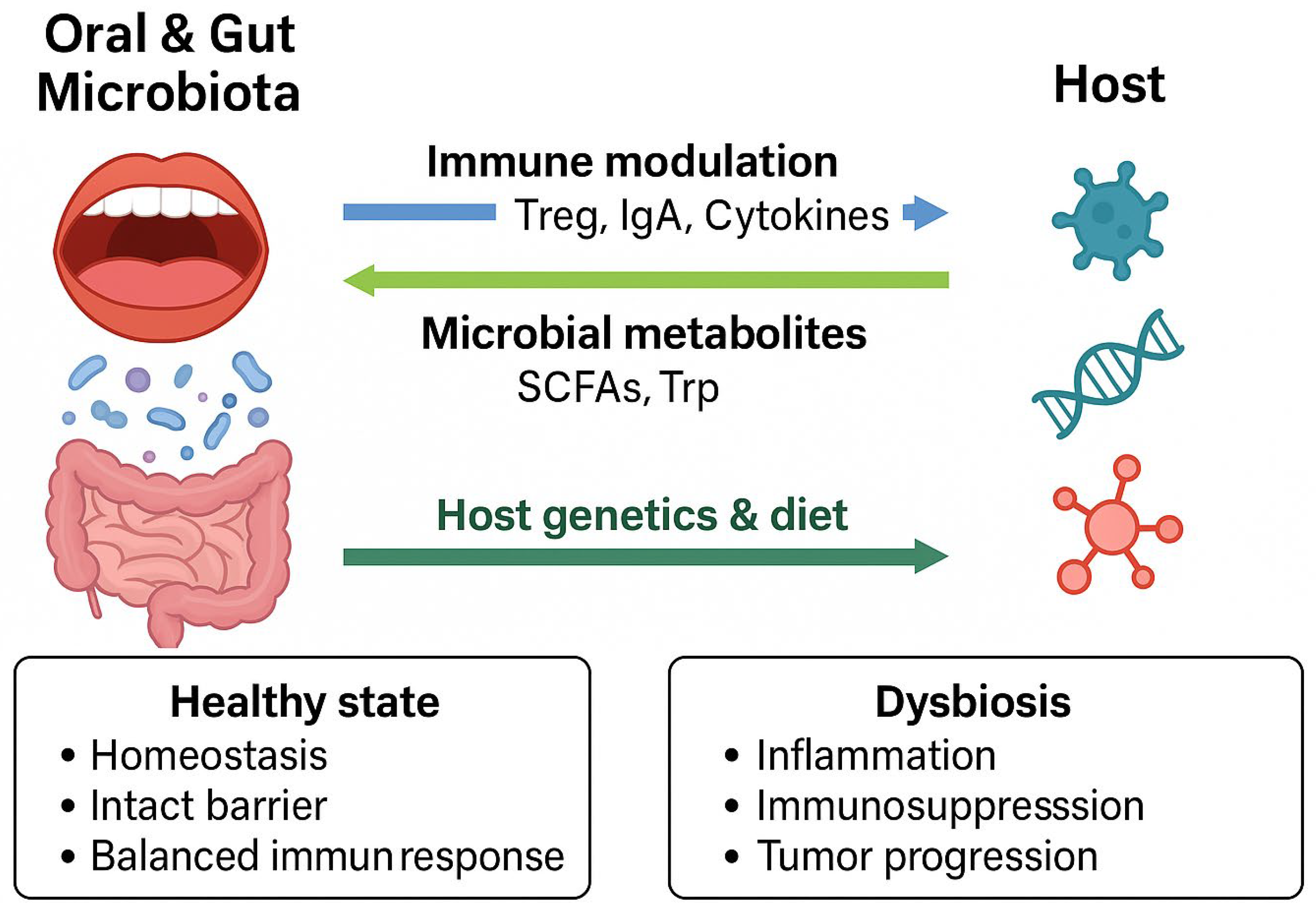

3.2. Interactions Between Microbiota and Host Immune System

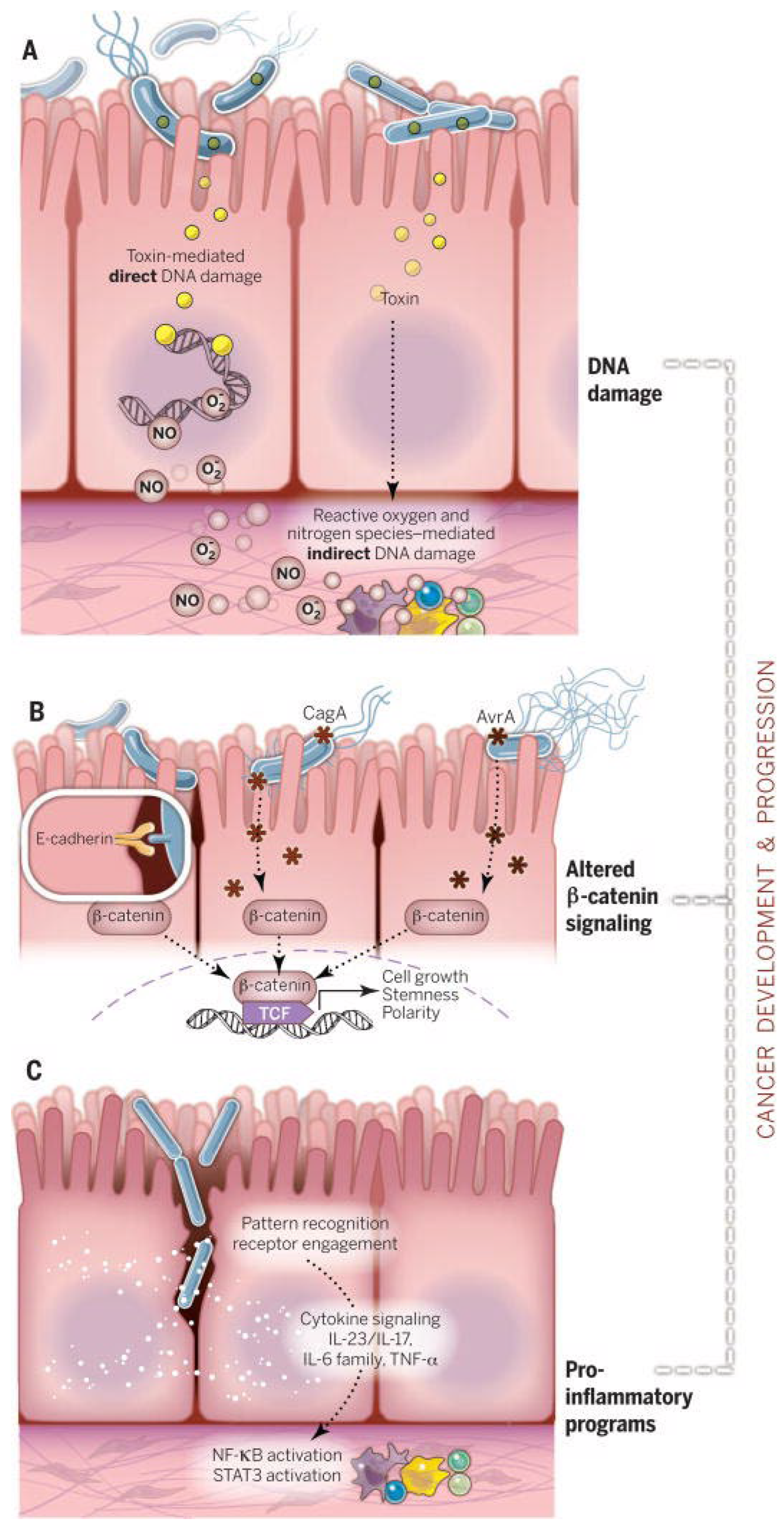

4. Dysbiosis and Haematological Malignancies

4.1. Definition and Characterization of Dysbiosis

- Loss of beneficial microbiota: a reduction in essential commensal bacteria such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium.

- Overgrowth of pathogenic microbes: an increase in opportunistic bacteria such as Clostridium difficile or Escherichia coli, that disrupts microbial balance.

- Loss of microbial diversity: a decrease in the variety of microbial species, often linked to reduced resilience of the intestinal ecosystem [38].

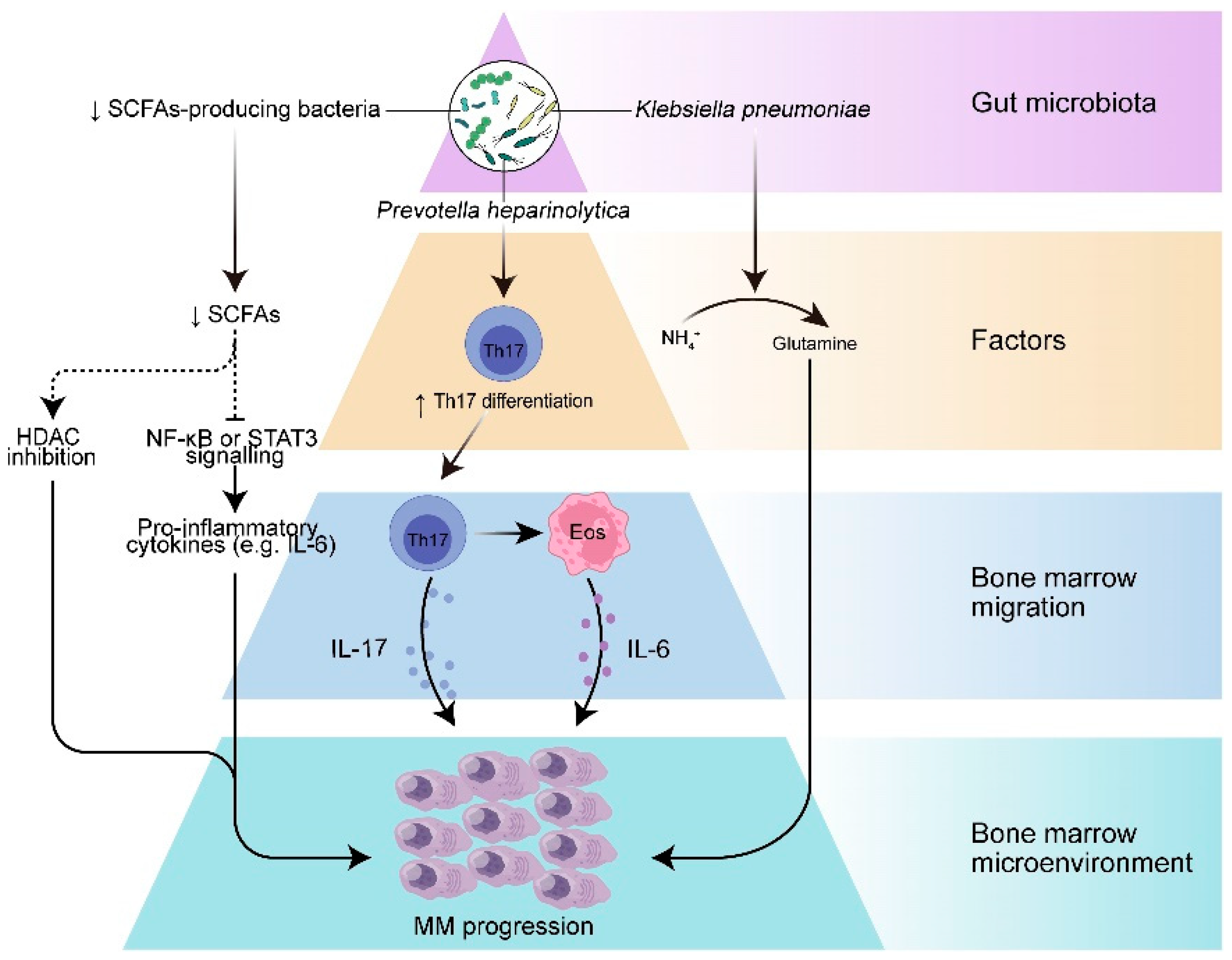

4.2. Evidence Linking Dysbiosis with Multiple Myeloma and Other Hematological Malignancies

4.3. Influence of Immune Dysfunction on Microbial Balance

4.4. Role of Antibiotics in the Onset of Dysbiosis

5. Microbial-Derived Metabolites and Immune Modulation

5.1. Key Microbial Metabolites and Their Roles in Health and Disease

5.2. Impact on Immune Regulation in Hematological Malignancies

5.3. Potential of Microbial-Derived Metabolites and Biomarkers for Disease Progression and Treatment Outcomes

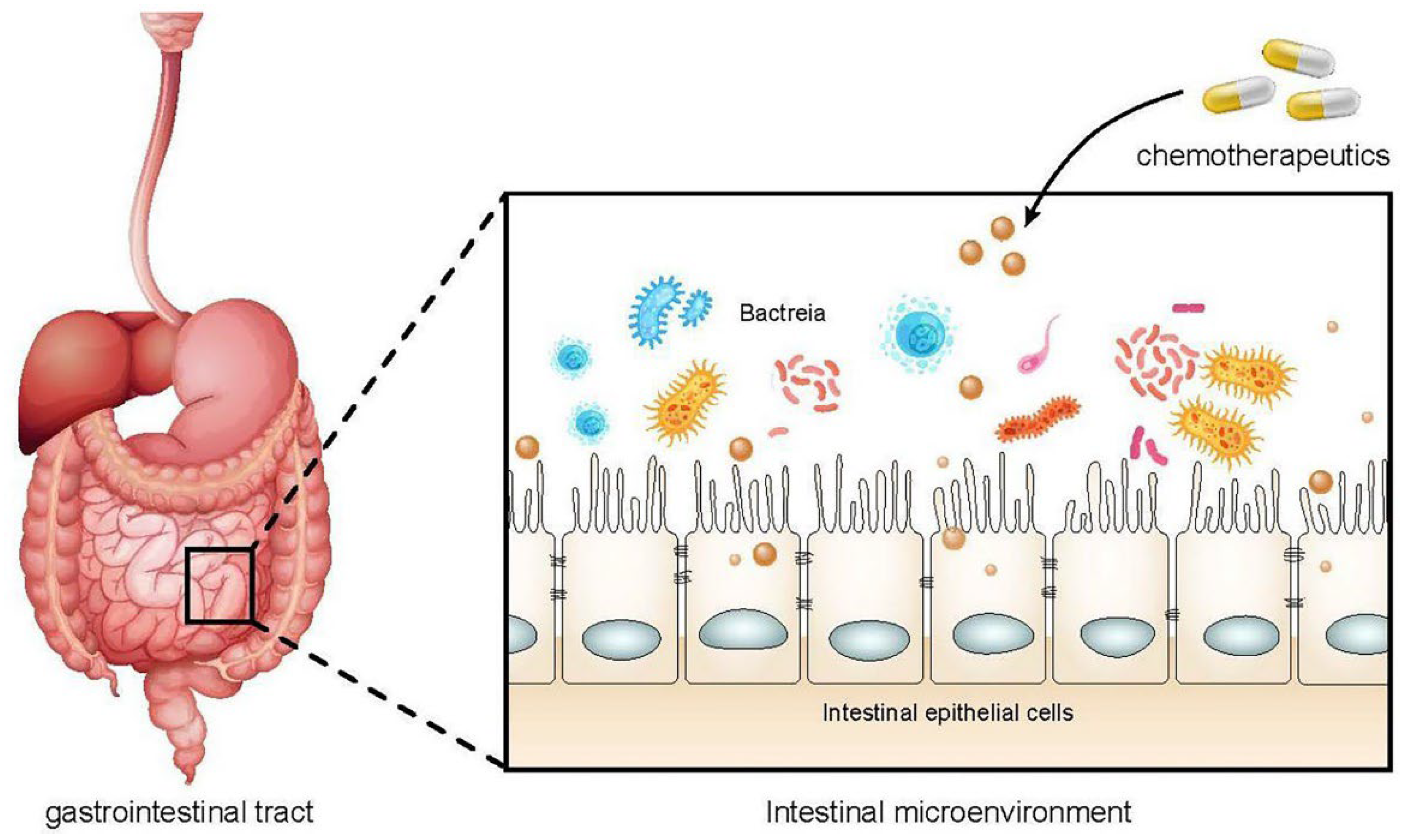

6. Chemotherapy-Induced Complications and Dysbiosis

6.1. Role of Microbiota in Chemotherapy-Related Mucositis and Infections

6.2. Chemotherapy-Induced Mucositis

6.3. Systemic Infections

6.4. Dysbiosis as a Consequence of Anticancer Therapies

7. Emerging Microbiota-Targeted Therapeutic Strategies

7.1. Probiotics and Prebiotics: Current Evidence and Future Directions

7.2. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation: Potential and Limitations

7.3. Other Novel Microbiota-Targeted Interventions

8. Bidirectional Interactions Between Host and Microbiota

9. Implication for Clinical Practice

9.1. Translation of Current Knowledge into Clinical Settings

9.2. Potential Diagnostic and Therapeutic Applications

10. Future Perspective

11. Discussion

12. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pérez, G.B.; Calaf, G.M.; Villalba, M.T.M.; Prieto, K.S.; Burgos, F.C. Frequency of hematologic malignancies in the population of Arica, Chile. Oncol. Lett. 2019, 18, 5637–5643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flowers, C.R.; Glover, R.; Lonial, S.; Brawley, O.W. Racial differences in the incidence and outcomes for patients with hematological malignancies. Curr. Probl. Cancer 2007, 31, 182–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, L. Haematological cancers. Nurs. Stand. 2016, 30, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolles, S.; Giralt, S.; Kerre, T.; Lazarus, H.M.; Mustafa, S.S.; Ria, R.; Vinh, D.C. Agents contributing to secondary immunodeficiency development in patients with multiple myeloma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: A systematic literature review. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1098326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Wang, Y.; Gong, T. The interplay between oral microbiota, gut microbiota and systematic diseases. J. Oral Microbiol. 2023, 15, 2213112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, K.; Wu, Z.-X.; Chen, X.-Y.; Wang, J.-Q.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, C.; Zhu, D.; Koya, J.B.; Wei, L.; Li, J.; et al. Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jia, Z.; Zhang, B.; Peng, L.; Zhao, F. Tracing the accumulation of in vivo human oral microbiota elucidates microbial community dynamics at the gateway to the GI tract. Gut 2020, 69, 1355–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maki, K.A.; Kazmi, N.; Barb, J.J.; Ames, N. The Oral and Gut Bacterial Microbiomes: Similarities, Differences, and Connections. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2021, 23, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, W.S. Cancer and the microbiota. Science 2015, 348, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisano, M.; Giordano, F.; Sangiovanni, G.; Capuano, N.; Acerra, A.; D’Ambrosio, F. The Interaction between the Oral Microbiome and Systemic Diseases: A Narrative Review. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 14, 1862–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manos, J. The human microbiome in disease and pathology. APMIS Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Immunol. Scand. 2022, 130, 690–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Hayashi-Okada, Y.; Falkner, K.L.; Shimizu, Y.; Zambon, J.J.; Kirkwood, K.L.; Schifferle, R.E.; Genco, R.J.; Diaz, P.I. Effect of an intensive antiplaque regimen on microbiome outcomes after nonsurgical periodontal therapy. J. Periodontol. 2025, 96, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggiani, S.; Mengoli, M.; Conti, G.; Fabbrini, M.; Brigidi, P.; Barone, M.; D’Amico, F.; Turroni, S. Gut microbiota resilience and recovery after anticancer chemotherapy. Microbiome Res. Rep. 2023, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, D.W.; Stringer, A.M.; Gibson, R.J. Chemotherapy-induced mucositis: The role of the gastrointestinal microbiome and toll-like receptors. Exp. Biol. Med. 2013, 238, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Gao, M.; Zhao, C.; Yang, J.; Gao, H.; Lu, X.; Ju, R.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y. Oral Administration of Probiotics Reduces Chemotherapy-Induced Diarrhea and Oral Mucositis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 823288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitamoto, S.; Nagao-Kitamoto, H.; Hein, R.; Schmidt, T.M.; Kamada, N. The Bacterial Connection between the Oral Cavity and the Gut Diseases. J. Dent. Res. 2020, 99, 1021–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Methé, B.A.; Nelson, K.E.; Pop, M.; Creasy, H.H.; Giglio, M.G.; Huttenhower, C.; Gevers, D.; Petrosino, J.F.; Abubucker, S.; Badger, J.H.; et al. A framework for human microbiome research. Nature 2012, 486, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adak, A.; Khan, M.R. An insight into gut microbiota and its functionalities. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 2018, 76, 473–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazor, C.E.; Mitchell, P.M.; Lee, A.M.; Stokes, L.N.; Loesche, W.J.; Dewhirst, F.E.; Paster, B.J. Diversity of bacterial populations on the tongue dorsa of patients with halitosis and healthy patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003, 41, 558–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Aidy, S.; van den Bogert, B.; Kleerebezem, M. The small intestine microbiota, nutritional modulation and relevance for health. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2015, 32, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollister, E.B.; Gao, C.; Versalovic, J. Compositional and functional features of the gastrointestinal microbiome and their effects on human health. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 1449–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, D.J.; Preston, T. Formation of short chain fatty acids by the gut microbiota and their impact on human metabolism. Gut Microbes 2016, 7, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, W.; Rył, A.; Mizerski, A.; Walczakiewicz, K.; Sipak, O.; Laszczyńska, M. Immunomodulatory potential of gut microbiome-derived short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). Acta Biochim. Pol. 2019, 66, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, S.V.; Pedersen, O. The Human Intestinal Microbiome in Health and Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2369–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, L.V.; Littman, D.R.; Macpherson, A.J. Interactions between the microbiota and the immune system. Science 2012, 336, 1268–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, X.; Gao, Y.; Yang, R. Gut Microbiota-Derived Tryptophan Metabolites Maintain Gut and Systemic Homeostasis. Cells 2022, 11, 2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilian, M. The oral microbiome—Friend or foe? Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2018, 126 (Suppl. S1), 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocco, S.; Tempesta, A.T.; Aluisio, G.V.; Mezzatesta, M.L.; Romano, A.; Schiavo, V.; Pergolizzi, B.; Santagati, M.; Panuzzo, C.; Isola, G. Antibacterial and cytotoxic effects of chlorhexidine combined with Sodium DNA on oral microorganisms: An in vitro study using Dictyostelium discoideum. J. Oral. Microbiol. 2025; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoogmoed, C.G.; Geertsema-Doornbusch, G.I.; Teughels, W.; Quirynen, M.; Busscher, H.J.; Van der Mei, H.C. Reduction of periodontal pathogens adhesion by antagonistic strains. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 2008, 23, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhurakivska, K.; Troiano, G.; Caponio, V.C.A.; Dioguardi, M.; Laino, L.; Maffione, A.B.; Lo Muzio, L. Do Changes in Oral Microbiota Correlate with Plasma Nitrite Response? A Systematic Review. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burne, R.A.; Marquis, R.E. Alkali production by oral bacteria and protection against dental caries. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2000, 193, 1–6. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11094270/ (accessed on 24 February 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Q.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Cui, J.; Zhu, M.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y. The oral-gut microbiota axis: A link in cardiometabolic diseases. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2025, 11, 11. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41522-025-00646-5 (accessed on 31 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Angjelova, A.; Jovanova, E.; Polizzi, A.; Leonardi, R.; Isola, G. Effects of Antiseptic Formulations on Oral Microbiota and Related Systemic Diseases: A Scoping Review. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belizário, J.E.; Faintuch, J. Microbiome and Gut Dysbiosis. Exp. Suppl. 2018, 109, 459–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blander, J.M.; Longman, R.S.; Iliev, I.D.; Sonnenberg, G.F.; Artis, D. Regulation of inflammation by microbiota interactions with the host. Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Bai, J.; Ma, C.; Wei, J.; Du, X. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Tumor Immunotherapy. J. Immunol. Res. 2021, 2021, 5061570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baima, G.; Minoli, M.; Michaud, D.S.; Aimetti, M.; Sanz, M.; Loos, B.G.; Romandini, M. Periodontitis and risk of cancer: Mechanistic evidence. Periodontol. 2000 2024, 96, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreiner, A.B.; Kao, J.Y.; Young, V.B. The gut microbiome in health and in disease. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2015, 31, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwabe, R.F.; Jobin, C. The microbiome and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2013, 13, 800–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigle, K.; Rogers, B. Pathobiology and Diagnosis of Multiple Myeloma. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2017, 33, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, A. Gut microbiota in acute leukemia: Current evidence and future directions. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1045497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peled, J.U.; Gomes, A.L.C.; Devlin, S.M.; Littmann, E.R.; Taur, Y.; Sung, A.D.; Weber, D.; Hashimoto, D.; Slingerland, A.E.; Slingerland, J.B.; et al. Microbiota as Predictor of Mortality in Allogeneic Hematopoietic-Cell Transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 822–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway-Peña, J.R.; Jobin, C. Microbiota Influences on Hematopoiesis and Blood Cancers: New Horizons? Blood Cancer Discov. 2023, 4, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachter, F.; Pikman, Y. Pathophysiology of Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Acta Haematol. 2024, 147, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malard, F.; Mohty, M. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet 2020, 395, 1146–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.-Y.; Mei, J.-X.; Yu, G.; Lei, L.; Zhang, W.-H.; Liu, K.; Chen, X.-L.; Kołat, D.; Yang, K.; Hu, J.-K. Role of the gut microbiota in anticancer therapy: From molecular mechanisms to clinical applications. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, H. Crosstalk Between Intestinal Microbiota Derived Metabolites and Tissues in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 703298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanov, I.I.; Tuganbaev, T.; Skelly, A.N.; Honda, K. T Cell Responses to the Microbiota. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 40, 559–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xiang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J. Gut microbiome in multiple myeloma: Mechanisms of progression and clinical applications. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1058272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hueso, T.; Ekpe, K.; Mayeur, C.; Gatse, A.; Joncquel-Chevallier Curt, M.; Gricourt, G.; Rodriguez, C.; Burdet, C.; Ulmann, G.; Neut, C.; et al. Impact and consequences of intensive chemotherapy on intestinal barrier and microbiota in acute myeloid leukemia: The role of mucosal strengthening. Gut Microbes 2020, 12, 1800897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriga, F.; Ramírez, P.; Wietstruck, A.; Rojas, N. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: Clinical use and perspectives. Biol. Res. 2012, 45, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balassa, K.; Danby, R.; Rocha, V. Haematopoietic stem cell transplants: Principles and indications. Br. J. Hosp. Med. 2019, 80, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shono, Y.; van den Brink, M.R.M. Gut microbiota injury in allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staffas, A.; Burgos da Silva, M.; van den Brink, M.R.M. The intestinal microbiota in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant and graft-versus-host disease. Blood 2017, 129, 927–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Shao, J.; Liao, Y.-T.; Wang, L.-N.; Jia, Y.; Dong, P.; Liu, Z.; He, D.; Li, C.; Zhang, X. Regulation of short-chain fatty acids in the immune system. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1186892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, S.M.; Nephew, K.P. Unintended Consequences of Antibiotic Therapy on the Microbiome Delivers a Gut Punch in Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Res. 2022, 82, 4511–4512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patangia, D.V.; Anthony Ryan, C.; Dempsey, E.; Paul Ross, R.; Stanton, C. Impact of antibiotics on the human microbiome and consequences for host health. MicrobiologyOpen 2022, 11, e1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, D.J.; Langdon, A.E.; Dantas, G. Understanding the impact of antibiotic perturbation on the human microbiome. Genome Med. 2020, 12, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwin, A.; Xie, J.; Smith, M. Antibiotic use: Impact on the microbiome and cellular therapy outcomes. Blood Adv. 2025, 9, 3356–3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, A.; Elebyary, O.; Fine, N.; Oveisi, M.; Glogauer, M. Metabolites of the oral microbiome: Important mediators of multikingdom interactions. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2022, 46, fuab039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belizário, J.E.; Faintuch, J.; Garay-Malpartida, M. Gut Microbiome Dysbiosis and Immunometabolism: New Frontiers for Treatment of Metabolic Diseases. Mediat. Inflamm. 2018, 2018, 2037838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantarel, B.L.; Lombard, V.; Henrissat, B. Complex carbohydrate utilization by the healthy human microbiome. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e28742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillemin, G.J.; Brew, B.J. Implications of the kynurenine pathway and quinolinic acid in Alzheimer’s disease. Redox Rep. Commun. Free Radic. Res. 2002, 7, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Amelio, P.; Sassi, F. Gut Microbiota, Immune System, and Bone. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2018, 102, 415–425. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28965190/ (accessed on 25 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Bourgin, M.; Kriaa, A.; Mkaouar, H.; Mariaule, V.; Jablaoui, A.; Maguin, E.; Rhimi, M. Bile Salt Hydrolases: At the Crossroads of Microbiota and Human Health. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe-Herranz, M.; Klein-González, N.; Rodríguez-Lobato, L.G.; Juan, M.; Fernández de Larrea, C. Gut Microbiota Influence in Hematological Malignancies: From Genesis to Cure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-García, A.; Arroyo, A.; García-Vicente, R.; Morales, M.L.; Gómez-Gordo, R.; Justo, P.; Cuéllar, C.; Sánchez-Pina, J.; López, N.; Alonso, R.; et al. Short-Chain Fatty Acid Production by Gut Microbiota Predicts Treatment Response in Multiple Myeloma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 904–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trézéguet, V.; Fatrouni, H.; Merched, A.J. Immuno-Metabolic Modulation of Liver Oncogenesis by the Tryptophan Metabolism. Cells 2021, 10, 3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Castro, L.; Garcia, R.; Venkateswaran, N.; Barnes, S.; Conacci-Sorrell, M. Tryptophan and its metabolites in normal physiology and cancer etiology. FEBS J. 2023, 290, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbert, C.E.; Cullen, M.T.; Casero, R.A.; Stewart, T.M. Polyamines in cancer: Integrating organismal metabolism and antitumour immunity. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2022, 22, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Režen, T.; Rozman, D.; Kovács, T.; Kovács, P.; Sipos, A.; Bai, P.; Mikó, E. The role of bile acids in carcinogenesis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 2022, 79, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostic, A.D.; Chun, E.; Robertson, L.; Glickman, J.N.; Gallini, C.A.; Michaud, M.; Clancy, T.E.; Chung, D.C.; Lochhead, P.; Hold, G.L.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum potentiates intestinal tumorigenesis and modulates the tumor-immune microenvironment. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 14, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botticelli, A.; Cerbelli, B.; Lionetto, L.; Zizzari, I.; Salati, M.; Pisano, A.; Federica, M.; Simmaco, M.; Nuti, M.; Marchetti, P. Can IDO activity predict primary resistance to anti-PD-1 treatment in NSCLC? J. Transl. Med. 2018, 16, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Wingard, J.R. Infection and mucosal injury in cancer treatment. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2001, 2001, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, J.; Al-Dasooqi, N.; Bossi, P.; Wardill, H.; Van Sebille, Y.; Al-Azri, A.; Bateman, E.; Correa, M.E.; Raber-Durlacher, J.; Kandwal, A.; et al. The pathogenesis of mucositis: Updated perspectives and emerging targets. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 4023–4033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, J.S.; Al-Qadami, G.H.; Laheij, A.M.G.A.; Bossi, P.; Fregnani, E.R.; Wardill, H.R. From Pathogenesis to Intervention: The Importance of the Microbiome in Oral Mucositis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartha, V.; Boutin, S.; Schüßler, D.L.; Felten, A.; Fazeli, S.; Kosely, F.; Luft, T.; Wolff, D.; Frese, C.; Schoilew, K. Exploring the Influence of Oral and Gut Microbiota on Ulcerative Mucositis: A Pilot Cohort Study. Oral Dis. 2025, 31, 1776–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Vliet, M.J.; Harmsen, H.J.M.; de Bont, E.S.J.M.; Tissing, W.J.E. The role of intestinal microbiota in the development and severity of chemotherapy-induced mucositis. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1000879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polizzi, A.; Leanza, Y.; Belmonte, A.; Grippaudo, C.; Leonardi, R.; Isola, G. Impact of Hyaluronic Acid and Other Re-Epithelializing Agents in Periodontal Regeneration: A Molecular Perspective. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkodee-Adoo, C.B.; Merz, W.G.; Karp, J.E. Management of infections in patients with acute leukemia. Oncology 2000, 14, 659–666, 671–672, discussion 672–677. [Google Scholar]

- Fink, M.P. Gastrointestinal mucosal injury in experimental models of shock, trauma, and sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 1991, 19, 627–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zembower, T.R. Epidemiology of infections in cancer patients. Cancer Treat. Res. 2014, 161, 43–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taur, Y.; Jenq, R.R.; Perales, M.-A.; Littmann, E.R.; Morjaria, S.; Ling, L.; No, D.; Gobourne, A.; Viale, A.; Dahi, P.B.; et al. The effects of intestinal tract bacterial diversity on mortality following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood 2014, 124, 1174–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway-Peña, J.; Smith, D.P.; Sahasrabhojane, P.; Ajami, N.J.; Wadsworth, W.D.; Daver, N.G.; Chemaly, R.F.; Marsh, L.; Ghantoji, S.S.; Pemmaraju, N.; et al. The Role of The Gastrointestinal Microbiome in Infectious Complications During Induction Chemotherapy for Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer 2016, 122, 2186–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soghli, N.; Khormali, A.; Mahboubi, D.; Peng, A.; Miguez, P.A. Recent advancements in artificial intelligence-powered cancer prediction from oral microbiome. Periodontol. 2000, 2025; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soveral, L.F.; Korczaguin, G.G.; Schmidt, P.S.; Nunes, I.S.; Fernandes, C.; Zárate-Bladés, C.R. Immunological mechanisms of fecal microbiota transplantation in recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 4762–4772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoil, D.; Parga, A.; Bostanci, N.; Belibasakis, G.N. Microbial diagnostics in periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000 2024, 95, 176–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vindigni, S.M.; Surawicz, C.M. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation. Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am. 2017, 46, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakken, J.S.; Borody, T.; Brandt, L.J.; Brill, J.V.; Demarco, D.C.; Franzos, M.A.; Kelly, C.; Khoruts, A.; Louie, T.; Martinelli, L.P.; et al. Treating Clostridium difficile infection with fecal microbiota transplantation. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2011, 9, 1044–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montassier, E.; Gastinne, T.; Vangay, P.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Bruley des Varannes, S.; Massart, S.; Moreau, P.; Potel, G.; de La Cochetière, M.F.; Batard, E.; et al. Chemotherapy-driven dysbiosis in the intestinal microbiome. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 42, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McQuade, J.L.; Daniel, C.R.; Helmink, B.A.; Wargo, J.A. Modulating the microbiome to improve therapeutic response in cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, e77–e91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Hou, X.; Wang, H.; Du, H.; Liu, Y. Influence of Gut Microbiota-Mediated Immune Regulation on Response to Chemotherapy. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, G.; D’Amico, F.; Fabbrini, M.; Brigidi, P.; Barone, M.; Turroni, S. Pharmacomicrobiomics in Anticancer Therapies: Why the Gut Microbiota Should Be Pointed Out. Genes 2022, 14, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yang, Y.; Pan, M.; Yang, F.; Yu, Y.; Qian, Z. Role of the gut microbiota in tumorigenesis and treatment. Theranostics 2024, 14, 2304–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvamani, S.; Mehta, V.; Ali El Enshasy, H.; Thevarajoo, S.; El Adawi, H.; Zeini, I.; Pham, K.; Varzakas, T.; Abomoelak, B. Efficacy of Probiotics-Based Interventions as Therapy for Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Recent Update. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 29, 3546–3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, K.; Shi, C.; Li, G. Cancer Immunotherapy: Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Brings Light. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2022, 23, 1777–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wark, G.; Samocha-Bonet, D.; Ghaly, S.; Danta, M. The Role of Diet in the Pathogenesis and Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Review. Nutrients 2020, 13, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.K.; Kumari, I.; Singh, B.; Sharma, K.K.; Tiwari, S.K. Probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics: Safe options for next-generation therapeutics. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 505–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, Y.P.; Bernardi, A.; Frozza, R.L. The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids from Gut Microbiota in Gut-Brain Communication. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlawat, S.; Asha, null; Sharma, K.K. Gut-organ axis: A microbial outreach and networking. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 72, 636–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baruch, E.N.; Youngster, I.; Ben-Betzalel, G.; Ortenberg, R.; Lahat, A.; Katz, L.; Adler, K.; Dick-Necula, D.; Raskin, S.; Bloch, N.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplant promotes response in immunotherapy-refractory melanoma patients. Science 2021, 371, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antushevich, H. Fecal microbiota transplantation in disease therapy. Clin. Chim. Acta 2020, 503, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinert, A.; Radulovic, K.; Niess, J. Gastrointestinal Tract: The Leading Role of Mucosal Immunity. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2016, 146, w14293. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Gastro-intestinal%20tract%3A%20the%20leading%20role%20of%20mucosal%20immunity&publication_year=2016&author=A.%20Steinert&author=K.%20Radulovic&author=J.%20Niess (accessed on 28 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Zhou, H.-Y.; Shen, H.-H.; Lufumpa, E.; Li, X.-M.; Guo, B.; Li, B.-Z. Microbe-Metabolite-Host Axis, Two-Way Action in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Human Autoimmunity. Autoimmun. Rev. 2019, 18, 455–475. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Microbe-metabolite-host%20axis%2C%20two-way%20action%20in%20the%20pathogenesis%20and%20treatment%20of%20human%20autoimmunity&publication_year=2019&author=X.%20Meng&author=H.-Y.%20Zhou&author=H.-H.%20Shen&author=E.%20Lufumpa&author=X.-M.%20Li&author=B.%20Guo&author=B.-Z.%20Li (accessed on 28 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Baunwall, S.M.D.; Lee, M.M.; Eriksen, M.K.; Mullish, B.H.; Marchesi, J.R.; Dahlerup, J.F.; Hvas, C.L. Faecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine 2020, 29–30, 100642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Montero, C.; Fraile-Martínez, O.; Gómez-Lahoz, A.M.; Pekarek, L.; Castellanos, A.J.; Noguerales-Fraguas, F.; Coca, S.; Guijarro, L.G.; García-Honduvilla, N.; Asúnsolo, A.; et al. Nutritional Components in Western Diet Versus Mediterranean Diet at the Gut Microbiota–Immune System Interplay. Implications for Health and Disease. Nutrients 2021, 13, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohr, M.W.; Narasimhulu, C.A.; Rudeski-Rohr, T.A.; Parthasarathy, S. Negative Effects of a High-Fat Diet on Intestinal Permeability: A Review. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nobre, L.M.S.; Fernandes, C.; Florêncio, K.G.D.; Alencar, N.M.N.; Wong, D.V.T.; Lima-Júnior, R.C.P. Could paraprobiotics be a safer alternative to probiotics for managing cancer chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal toxicities? Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2023, 55, e12522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Generoso, S.V.; Viana, M.L.; Santos, R.G.; Arantes, R.M.E.; Martins, F.S.; Nicoli, J.R.; Machado, J.A.N.; Correia, M.I.T.D.; Cardoso, V.N. Protection against increased intestinal permeability and bacterial translocation induced by intestinal obstruction in mice treated with viable and heat-killed Saccharomyces boulardii. Eur. J. Nutr. 2011, 50, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isola, G.; Annunziata, M.; Angjelova, A.; Alibrandi, A.; Tartaglia, G.M.; Scannapieco, F.A. Effectiveness of two supportive periodontal care protocols and outcome predictors during periodontitis: A randomized controlled trial. J. Periodontol. 2025; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H. Host gene-microbiome interactions: Molecular mechanisms in inflammatory bowel disease. Genome Med. 2017, 9, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrich, J.K.; Waters, J.L.; Poole, A.C.; Sutter, J.L.; Koren, O.; Blekhman, R.; Beaumont, M.; Van Treuren, W.; Knight, R.; Bell, J.T.; et al. Human genetics shape the gut microbiome. Cell 2014, 159, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Liwinski, T.; Elinav, E. Interaction between microbiota and immunity in health and disease. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 492–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkaid, Y.; Hand, T.W. Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell 2014, 157, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makki, K.; Deehan, E.C.; Walter, J.; Bäckhed, F. The Impact of Dietary Fiber on Gut Microbiota in Host Health and Disease. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 23, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steer, T.; Carpenter, H.; Tuohy, K.; Gibson, G.R. Perspectives on the role of the human gut microbiota and its modulation by pro- and prebiotics. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2000, 13, 229–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, L.A.; Maurice, C.F.; Carmody, R.N.; Gootenberg, D.B.; Button, J.E.; Wolfe, B.E.; Ling, A.V.; Devlin, A.S.; Varma, Y.; Fischbach, M.A.; et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 2014, 505, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Ghannoum, M.; Gallogly, M.; de Lima, M.; Malek, E. Influence of gut microbiome on multiple myeloma: Friend or foe? J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e000576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, X.; Zhu, Y.; Ouyang, J.; Wang, Y.; Lei, Q.; Xia, J.; Guan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Guo, J.; He, Y.; et al. Alterations of gut microbiome accelerate multiple myeloma progression by increasing the relative abundances of nitrogen-recycling bacteria. Microbiome 2020, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Yuan, X.; Wang, M.; He, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Li, Q. Gut microbiota influence immunotherapy responses: Mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matson, V.; Chervin, C.S.; Gajewski, T.F. Cancer and the Microbiome-Influence of the Commensal Microbiota on Cancer, Immune Responses, and Immunotherapy. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 600–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luu, M.; Weigand, K.; Wedi, F.; Breidenbend, C.; Leister, H.; Pautz, S.; Adhikary, T.; Visekruna, A. Regulation of the effector function of CD8+ T cells by gut microbiota-derived metabolite butyrate. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghpour Heravi, F. Gut Microbiota and Autoimmune Diseases: Mechanisms, Treatment, Challenges, and Future Recommendations. Curr. Clin. Microbiol. Rep. 2024, 11, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routy, B.; Le Chatelier, E.; Derosa, L.; Duong, C.P.M.; Alou, M.T.; Daillère, R.; Fluckiger, A.; Messaoudene, M.; Rauber, C.; Roberti, M.P.; et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science 2018, 359, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viaud, S.; Saccheri, F.; Mignot, G.; Yamazaki, T.; Daillère, R.; Hannani, D.; Enot, D.P.; Pfirschke, C.; Engblom, C.; Pittet, M.J.; et al. The intestinal microbiota modulates the anticancer immune effects of cyclophosphamide. Science 2013, 342, 971–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarasinghe, S.L.; Su, S.; Dong, X.; Zappia, L.; Ritchie, M.E.; Gouil, Q. Opportunities and challenges in long-read sequencing data analysis. Genome Biol. 2020, 21, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.L. Illuminating the oral microbiome and its host interactions: Recent advancements in omics and bioinformatics technologies in the context of oral microbiome research. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2023, 47, fuad051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hebshi, N.N.; Baraniya, D.; Chen, T.; Hill, J.; Puri, S.; Tellez, M.; Hasan, N.A.; Colwell, R.R.; Ismail, A. Metagenome sequencing-based strain-level and functional characterization of supragingival microbiome associated with dental caries in children. J. Oral Microbiol. 2019, 11, 1557986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Li, D.; Liu, Y.-X. Microbiome research outlook: Past, present, and future. Protein Cell 2023, 14, 709–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Zheng, X.; Cohen, M.F.; Liu, Y.-X. Sequence-based Functional Metagenomics Reveals Novel Natural Diversity of Functional CopA in Environmental Microbiomes. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2023, 21, 1182–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Li, Z.; Peng, X. Regulatory effects of oral microbe on intestinal microbiota and the illness. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1093967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, C.F.F.A.; Correia-de-Sá, T.; Araujo, R.; Barbosa, F.; Burnet, P.W.J.; Ferreira-Gomes, J.; Sampaio-Maia, B. The oral-gut microbiota relationship in healthy humans: Identifying shared bacteria between environments and age groups. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1475159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.; Xie, P.; Yang, S.; Niu, G.; Liu, X.; Ding, Z.; Xue, C.; Liu, Y.-X.; Shen, Q.; Yuan, J. ggClusterNet: An R package for microbiome network analysis and modularity-based multiple network layouts. iMeta 2022, 1, e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickramarachchi, A.; Lin, Y. Binning long reads in metagenomics datasets using composition and coverage information. Algorithms Mol. Biol. AMB 2022, 17, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadegar, A.; Bar-Yoseph, H.; Monaghan, T.M.; Pakpour, S.; Severino, A.; Kuijper, E.J.; Smits, W.K.; Terveer, E.M.; Neupane, S.; Nabavi-Rad, A.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation: Current challenges and future landscapes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2024, 37, e0006022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woerner, J.; Huang, Y.; Hutter, S.; Gurnari, C.; Sánchez, J.; Wang, J.; Huang, Y.; Schnabel, D.; Aaby, M.; Wanying, X.; et al. Circulating microbial content in myeloid malignancy patients is associated with disease subtypes and patient outcomes. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y. Gut microbiota derived metabolites in cardiovascular health and disease. Protein Cell 2018, 9, 416–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Belmonte, A.; Leanza, Y.; Polizzi, A.; Romano, A.; Allegra, A.; Leonardi, R.; Panuzzo, C.; Isola, G. Impact of Oral and Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in Patients with Multiple Myeloma and Hematological Malignancies: A Narrative Review. Oral 2025, 5, 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral5040101

Belmonte A, Leanza Y, Polizzi A, Romano A, Allegra A, Leonardi R, Panuzzo C, Isola G. Impact of Oral and Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in Patients with Multiple Myeloma and Hematological Malignancies: A Narrative Review. Oral. 2025; 5(4):101. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral5040101

Chicago/Turabian StyleBelmonte, Antonio, Ylenia Leanza, Alessandro Polizzi, Alessandra Romano, Alessandro Allegra, Rosalia Leonardi, Cristina Panuzzo, and Gaetano Isola. 2025. "Impact of Oral and Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in Patients with Multiple Myeloma and Hematological Malignancies: A Narrative Review" Oral 5, no. 4: 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral5040101

APA StyleBelmonte, A., Leanza, Y., Polizzi, A., Romano, A., Allegra, A., Leonardi, R., Panuzzo, C., & Isola, G. (2025). Impact of Oral and Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in Patients with Multiple Myeloma and Hematological Malignancies: A Narrative Review. Oral, 5(4), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral5040101