Abstract

This study examines how travelers alleviate anxiety during trips through real-time self-disclosure on social media. Based on the Transactional Theory of Stress and Coping and Social Penetration Theory, this study explores a process model in which travel anxiety triggers self-disclosure, which subsequently strengthens perceived social connectedness and psychological comfort. Survey data from 240 Korean travelers who shared content during their trip were analyzed using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM), which is suitable to this research in terms of estimating complex, theory-building models with multiple latent constructs. Results show that psychological comfort predicts travel satisfaction and fully mediates the effect of social connectedness on satisfaction. By reframing social media use as a real-time coping mechanism rather than post-experience sharing, and positioning psychological comfort as a distinct low-arousal emotional mediator, this study extends tourism research on on-site digital coping and tourist experience management.

1. Introduction

In today’s digitally saturated travel environment, social networking platforms have become deeply integrated into the routines of travel, frequently reflected in activities such as sharing scenic images or connecting with others (Yan et al., 2024; B. Lin et al., 2024). This activity has been understood as a form of impression management or memory documentation during travel in the existing literature (Wang et al., 2017). Yet beneath this surface-level engagement lies a deeper, often overlooked psychological function. As travelers encounter uncertainty, isolation, and emotional friction in unfamiliar environments, social media may evolve from a tool for socialization into a mechanism for emotional regulation. What begins as casual content sharing can, in moments of stress or vulnerability, take on a different purpose—serving as an emotional coping strategy. Accordingly, this study examines whether and how travel anxiety shapes travelers’ real-time content sharing experience on social media during trips and its subsequent consequences. While extensive research has examined travelers’ use of social media, limited attention has been paid to its role from a process-oriented psychological perspective—how anxiety experienced during travel activates real-time self-disclosure as an emotion-focused coping process and how this process shapes travelers’ relational and emotional outcomes.

Given the paradoxical nature of travel, it is important to explore tourists’ coping dynamics on a trip. While tourism is widely associated with novelty, pleasure, and emotional rejuvenation, tourists can also experience stress and anxiety induced by factors including language barriers, cultural dissonance, and interpersonal ambiguity (H. Huang et al., 2023). The notion of travel anxiety is widely studied in the existing literature, in line with its influence on travel decisions, in which studies have examined travel anxiety in the context of pre-trip concerns or high-impact events like pandemics and terrorism (Karagöz et al., 2021; Rather et al., 2025). These studies offer valuable implications regarding the critical role that travel anxiety plays in diminishing individuals’ motivation to travel. However, limited attention has been paid to exploring anxiety aroused during travel. In fact, travel motivations such as the pursuit of pleasure or escape may heighten travelers’ sensitivity to emotional discomfort when expectations are unmet. To address this research gap, this research examines how travelers cope with anxiety in situ through socially embedded and digitally mediated behaviors.

While previous studies emphasized social effects of self-disclosure on social media, such as in connecting with others or in projecting idealized image, (C. Y. Lin et al., 2021; Cao et al., 2024), its role as an emotion-focused coping mechanism during the travel experience remains insufficiently examined. Furthermore, prior tourism research has rarely distinguished between different types of self-disclosure, even though these forms may have different relational and emotional effects. In addition, while it is known that social connectedness contributes to well-being and satisfaction (Zhuang & Wang, 2024), little is known about the role of digital coping behaviors in cultivating connectedness or the extent to which that connectedness shapes tourists’ appraisal of the travel experience including psychological comfort. Psychological comfort itself is often subsumed within broader constructs like emotional value, leaving important gaps in our understanding of its specific contribution to positive travel experiences (Radia et al., 2022; Prayag et al., 2013).

The research objective of this study is to empirically examine a sequential process model in which travel anxiety predicts real-time self-disclosure, which in turn enhances social connectedness and psychological comfort, leading to travel satisfaction. Based on the Transactional Theory of Stress and Coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) and Social Penetration Theory (Altman & Taylor, 1973), the proposed model extends current understanding of digitally mediated coping during travel and offers implications for supporting traveler well-being in social media-embedded tourism contexts.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Framework

Gross’s (1998) Process Model, one of the most widely cited emotion regulation work, highlights how individuals internally manage feelings through cognitive reappraisal or suppression. Similarly, Rimé’s (2009) work on the Social Sharing of Emotion emphasizes the verbalization of affect. However, past studies have overlooked the underlying stress-appraisal mechanisms. While these models offer valuable insights into how emotions can be managed, they are limited in understanding the short-term and socially embedded nature of travel-related anxiety in digital environments. When tourists share their experiences online, they regulate emotions in ways that are socially distributed and mediated through indirect digital interactions (Wolfers & Utz, 2022). This dynamic underscores the need for a framework that captures the interplay between environmental stressors and interpersonal coping resources. Therefore, this study adopts the Transactional Theory of Stress and Coping (TTSC) and Social Penetration Theory (SPT) to explain how emotion-focused coping is enacted through real-time self-disclosure on social media. This theoretical synthesis offers a contextually appropriate lens by aligning the appraisal-driven activation of coping responses (TTSC) with the relational processes through which social support and emotional stability are achieved (SPT).

To identify how travelers regulate anxiety and emotional outcomes through real-time social media content sharing, this study integrates two key theories: the Transactional Theory of Stress and Coping (TTSC) (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) and Social Penetration Theory (SPT) (Altman & Taylor, 1973). Together, they illuminate the motivational drivers and interpersonal-emotional consequences of digital self-disclosure during travel. By integrating TTSC and SPT, this study moves beyond treating social media as a mere sharing tool to examining it as a dynamic system where travelers process internal stress through external relational building

2.1.1. Transactional Theory of Stress and Coping (TTSC)

TTSC conceptualizes stress as a dynamic and ongoing transaction between individuals and their environment. At its core is the appraisal process in which primary evaluation includes whether an event is threatening or challenging, and a secondary evaluation of one’s coping resources. When coping capacity is perceived as inadequate, individuals employ coping strategies, categorized as problem-focused or emotion-focused (Folkman & Lazarus, 1985).

While problem-focused strategies target external issues, emotion-focused strategies regulate internal emotional states, particularly under ambiguous or uncontrollable stress. In digitally mediated settings, emotion-focused coping increasingly involves communication and social interaction (Demirtepe-Saygili, 2022).

Prior research has applied TTSC in tourism and digitally mediated contexts to explain how stressors translate into outcomes through coping processes. For example, TTSC-based tourism studies demonstrate that appraisal factors influence behavioral outcomes indirectly via coping strategies, supporting TTSC’s process-oriented logic (Yin & Hwang, 2025). Qualitative evidence further shows that emotion-focused coping often involves expressive behaviors, such as writing or communicating with others, which help restore emotional balance under conditions of uncertainty (Y. Lee, 2025). In addition, TTSC has been used to model stress processes in SNS-mediated environments, including contexts in which digital platforms function as sources of strain or fatigue, underscoring the theory’s applicability to psychologically embedded digital interactions (X. Zhang et al., 2024).

In tourism, TTSC has informed studies on how travelers cope with uncertainty, cultural unfamiliarity, and crisis (Pratt & Tolkach, 2022; Peterkin et al., 2024). However, most focus on visible behaviors such as avoidance or itinerary changes, giving less attention to digitally mediated, socially embedded coping. Building on prior TTSC applications and evidence that emotion-focused coping can operate through communicative expression, the present study extends TTSC to examine real-time self-disclosure on social media as an adaptive coping resource during travel-related anxiety.

2.1.2. Social Penetration Theory (SPT)

SPT explains the development of interpersonal closeness through gradual, reciprocal self-disclosure (Altman & Taylor, 1973). As individuals reveal more personal information, both in depth and frequency, the relationship deepens, fostering intimacy and emotional bonding.

While SPT originated in face-to-face interactions, recent research has extended its relevance to digital contexts, particularly where social media platforms mediate relationship development (Lei et al., 2023; M. Liu et al., 2023). In such environments, individuals are more likely to engage in deep self-disclosure due to perceived anonymity and selective self-presentation, accelerating intimacy formation (Tidwell & Walther, 2002). For instance, Lei et al. (2023) found that online self-disclosure significantly enhanced perceived social support, leading to reduced depressive mood—demonstrating the relational and emotional value of disclosure. Similarly, mutual self-disclosure between restaurant servers and customers increased trust and engagement, highlighting how disclosure behaviors grounded in SPT build emotional connectedness (M. Liu et al., 2023).

The proposition of SPT has also been applied in tourism studies such as in the work of H. Lin et al. (2019) which demonstrated that tourists who engaged in interpersonal disclosure experienced greater cohesion, intimacy, and satisfaction with their travel experiences. Moreover, Hu et al. (2025) showed that emotionally expressive communication strengthens emotional solidarity in guided tours.

These empirical findings validate SPT’s core proposition that relational depth arises through structured disclosure processes. They also reinforce the theory’s application to emotionally charged, transient settings such as travel, where individuals seek emotional stability through digital interaction.

Accordingly, the current study builds on SPT by framing real-time social media self-disclosure not only as a mechanism of relational closeness, but also as an adaptive tool for emotional regulation in unfamiliar travel contexts. The research model tested in this study, from anxiety to self-disclosure, and from self-disclosure to social connectedness, represent empirical operationalizations of SPT’s central claims.

2.1.3. Theoretical Synthesis: Socially Mediated Emotion Regulation

While TTSC and SPT have traditionally been applied independently to stress regulation and interpersonal development, this study synthesizes them through the higher-order mechanism of socially mediated emotion regulation. Drawing on propositions of Wolfers and Utz (2022) on social media’s role in coping, we theorize that the appraisal of travel anxiety activates emotion-focused strategies that are optimally aligned with relationally embedded forms of regulation. Within this integrated framework, self-disclosure operates as the regulatory mechanism through which emotion-focused coping is enacted, transforming internal psychological distress into socially mediated relief. The depth and breadth of disclosure (SPT) enable affect regulation through perceived empathy, visibility, and support. Rather than treating TTSC and SPT as sequential, this model positions self-disclosure as a dual-purpose act: a motivated response to resource deficits (TTSC) and a structured relational process that sustains emotional stability (SPT) in dynamic, transient travel environments.

2.2. Travel Anxiety

Anxiety is a psychological state marked by unease and hyper-vigilance in response to uncertainty or lack of control, which differs from discrete emotions like anger or sadness and is particularly prevalent in ambiguous environments (Kirillova et al., 2017). In tourism, anxiety is commonly linked to perceived risks such as safety threats, unfamiliar norms, or language barriers (H. Huang et al., 2023). For example, Jiang et al. (2024) found that anxiety is a dominant emotional response in crisis tourism, influencing both decisions and psychological well-being.

Empirical studies consistently show that travel-related anxiety negatively affects behavioral intentions. Anxiety reduces perceived destination attractiveness, suppresses travel plans, and increases avoidance-oriented behavior (Karagöz et al., 2021; Rather et al., 2025). During the COVID-19 pandemic, heightened anxiety led to decreased willingness to travel among Hong Kong residents (Luo & Lam, 2020), and reduced overall interest in booking trips (Zenker et al., 2021). While most research emphasizes crisis-related anxiety or vulnerable groups (e.g., female solo travelers), routine forms of anxiety such as navigating unfamiliar environments or dealing with language barriers are also impactful yet understudied (H. Huang et al., 2023).

Despite its relevance, little research explores how tourists actively manage anxiety in real time. One exception is Wang (2025), who found that exposure to others’ travel posts prior to travel reduced perceived constraints. However, this study focused on passive media use before trips, not active emotional coping during travel. To address this gap, this study applies TTSC’s concept of emotion-focused coping, where self-disclosure—the act of sharing personal thoughts or emotions—functions as a key mechanism (H. Huang et al., 2023). In digital contexts, self-disclosure often provides emotional regulation and validation.

Studies in health and crisis communication indicate that anxiety frequently triggers disclosure behaviors aimed at securing reassurance (Rains & Keating, 2015; Nabity-Grover et al., 2020). For example, R. Zhang (2017) found that people disclose most on Facebook during stressful episodes, leading to reductions in next-day negative affect through supportive feedback. In tourism, although direct evidence is limited, preliminary research suggests that travelers experiencing stress turn to social media to vent or connect with others (Choe et al., 2017; H. Huang et al., 2023).

Building on SPT, this study conceptualizes self-disclosure along two dimensions: amount (frequency or volume) and depth (emotional intimacy or vulnerability). Past research shows that individuals under emotional strain may increase disclosure frequency to gain visibility or validation, while deeper disclosure may reflect a need for empathy and support (Bai et al., 2025). Accordingly, we hypothesize the following:

H1.

Travel anxiety positively influences the self-disclosure amount.

H2.

Travel anxiety positively influences the self-disclosure depth.

2.3. Self-Disclosure

Self-disclosure refers to the sharing personal information, emotions, or experiences to others, playing a crucial role in forming interpersonal closeness (Altman & Taylor, 1973). It is defined along two dimensions of amount and depth, based on the frequency of communication and the intimacy of the shared content (Wheeless & Grotz, 1976).

In digital spaces like social networking sites, self-disclosure serves several psychosocial functions: it helps users express identity, offload emotions, and seek social affirmation (Bai et al., 2025; Lei et al., 2023). It can also be shaped by algorithmic design features that prompt users to share frequently to maintain visibility or engagement (Wang et al., 2017). While these performative and platform-driven motives are well documented, this study focuses on self-disclosure as an adaptive, emotionally expressive response to situational stress—particularly relevant in the context of travel anxiety. Grounded in the transactional theory of stress and coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), this conceptualization reflects the idea that when individuals experience acute stress, they engage in behaviors aimed at restoring emotional equilibrium. Therefore, this research positions emotionally motivated disclosure as a coping resource activated in response to travel-induced anxiety.

Tourism offers a distinctive context in which travelers use SNS platforms to document experiences, maintain a sense of social presence, and seek engagement from distant peers. Such digital interactions can strengthen perceived closeness and trust, even in transient or unfamiliar environments (Hu et al., 2025). However, most prior research frames self-disclosure as an outcome influenced by variables like trust or ostracism (C. Y. Lin et al., 2021; Cao et al., 2024), rather than examining its independent psychological and social consequences.

One such consequence is social connectedness, defined as a subjective sense of emotional closeness and integration within a social network (R. M. Lee & Robbins, 1995). Evidence from health and crisis communication suggests that self-disclosure enhances perceived connectedness by eliciting affirmation and empathetic responses (H.-Y. Huang, 2016; Wu-Ouyang & Hu, 2023).

These benefits, however, may arise through distinct psychological pathways depending on the form of disclosure. Prior studies suggest that the amount and depth of self-disclosure serve distinct psychosocial functions. According to Social Penetration Theory (Altman & Taylor, 1973), the amount of disclosure reflects the range and frequency of shared content, maintaining social presence and signaling availability for interaction (C. Y. Lin et al., 2021). In contrast, the depth of disclosure involves emotionally intimate or vulnerable content that fosters empathy, validation, and psychological relief (Cao et al., 2024). Under conditions of travel anxiety, these dimensions may support coping through different channels: frequent sharing enhances perceived connection, while deeper emotional sharing enables more meaningful emotional adjustment. Based on this background, following hypotheses are proposed:

H3.

The self-disclosure amount positively influences perceived social connectedness.

H4.

The self-disclosure depth positively influences perceived social connectedness.

2.4. Social Connectedness and Outcomes

Social connectedness reflects an individual’s sense of belonging, closeness, and emotional integration within social relationships (S. Lee et al., 2023). In tourism, connectedness can arise through interpersonal interactions or online communities, helping travelers manage emotional tension in unfamiliar contexts (Zhuang & Wang, 2024; W. Liu et al., 2022).

Although some studies distinguish between different types of social connectedness such as bonding (from close ties) and bridging (from weak or diverse ties) (Putnam, 2000), this study conceptualizes social connectedness as a unified psychological state. This approach is in line with findings that the emotional benefit of feeling socially connected, particularly in anxiety-inducing contexts, can arise from both strong and weak ties (Michikyan et al., 2023). Rather than the structural nature of the tie, it is the perceived emotional function of the interaction, feeling supported, acknowledged, and less alone, that underpins its psychological value. This perspective is especially relevant in digitally mediated environments, where self-disclosure on SNS can elicit emotional validation and affirm social presence regardless of tie strength (Michikyan et al., 2023).

Connectedness has been shown to yield various psychological benefits, including emotional security and increased well-being. For instance, W. Liu et al. (2022) found that tourist-to-tourist interactions improved life satisfaction, with bonding serving as a mediator. Li et al. (2025) showed that value co-creation activities enhance both hedonic and eudaimonic well-being by strengthening social ties. These outcomes reflect the role of connectedness as a psychosocial resource that buffers stress, fosters emotional safety, and supports adaptive coping (Zhuang & Wang, 2024). These relational benefits may promote psychological comfort by providing emotional stability and support in unfamiliar environments (Li et al., 2025; W. Liu et al., 2022). Based on this background, the following is hypothesized:

H5.

Perceived social connectedness positively influences psychological comfort.

Social connectedness may also influence travel satisfaction. Tourists who feel emotionally supported are more likely to report satisfaction due to meaningful interactions and positive emotions (Li et al., 2025; Zhuang & Wang, 2024). Thus, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H6.

Perceived social connectedness positively influences satisfaction.

2.5. Psychological Comfort and Satisfaction

Psychological comfort refers to a state of emotional security and freedom from stress that fulfills fundamental emotional needs (Radia et al., 2022; Spake et al., 2003). In tourism, it involves feeling calm, safe, and relaxed during activities—whether through service interactions, familiar settings, or social bonds (Prayag et al., 2013). For instance, travelers may experience psychological comfort when eating familiar food abroad or interacting with welcoming locals (Wang et al., 2023).

While constructs such as relaxation, emotional value, and affective well-being may appear similar to psychological comfort, it is conceptually distinct in both scope and function. Unlike affective well-being, which represents a holistic and enduring state of life satisfaction (Hofmann et al., 2014), psychological comfort is situational and transient. It also differs from relaxation, which is typically defined as a passive and physical state (Rehman et al., 2025), whereas psychological comfort is as an active cognitive–emotional response to situational stressors. Finally, while emotional value encompasses various high-arousal perceptions of utility (Buzova et al., 2023), psychological comfort is characterized by its low-arousal nature, focusing specifically on the restoration of emotional equilibrium and safety. Treating psychological comfort as a standalone construct allows for a more granular analysis of the relief phase of the coping process, a nuance that is typically obscured when subsumed under global metrics like generic emotion-related constructs.

Unlike physical comfort, psychological comfort can be a stronger predictor of satisfaction. Tourists may remain satisfied even if service elements fall short, provided their emotional needs are met (Pizam et al., 1978). Comfort also strengthens trust and loyalty in relational contexts (Ainsworth & Foster, 2017), and reinforces emotional stability (Radia et al., 2022). Comfort shapes travelers’ emotional appraisals, allowing them to focus on positive aspects of the experience (Gaur et al., 2019). Low-arousal emotional states like calmness and relief are positively linked to satisfaction. Emotional security improves destination evaluations and post-travel reflections (Prayag et al., 2013). Yet, few studies treat psychological comfort as a standalone predictor, often subsuming it within constructs like emotional value. This study addresses this gap by proposing the following hypothesis:

H7.

Psychological Comfort Positively Influences Satisfaction.

2.6. Mediating Role of Psychological Comfort

In addition to its direct effect, psychological comfort may mediate the relationship between social connectedness and satisfaction. According to TTSC, supportive social ties reduce psychological strain by reframing stressors as manageable (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Fredrickson’s (2001) Broaden-and-Build Theory suggests that such emotional states broaden cognitive and evaluative capacity, increasing the likelihood of favorable judgments.

Recent studies support this sequence. W. Liu et al. (2022) found that emotional states mediate the link between social bonding and life satisfaction. Zhou et al. (2024) identified psychological comfort as a key emotional outcome of host–guest interaction. In services, emotional ease enhances satisfaction and trust even beyond functional quality (Spake et al., 2003). However, tourism research often assumes a direct path between connectedness and satisfaction, overlooking affective mechanisms. This study proposes that comfort mediates that relationship as follows:

H8.

Psychological comfort mediates the relationship between social connectedness and satisfaction.

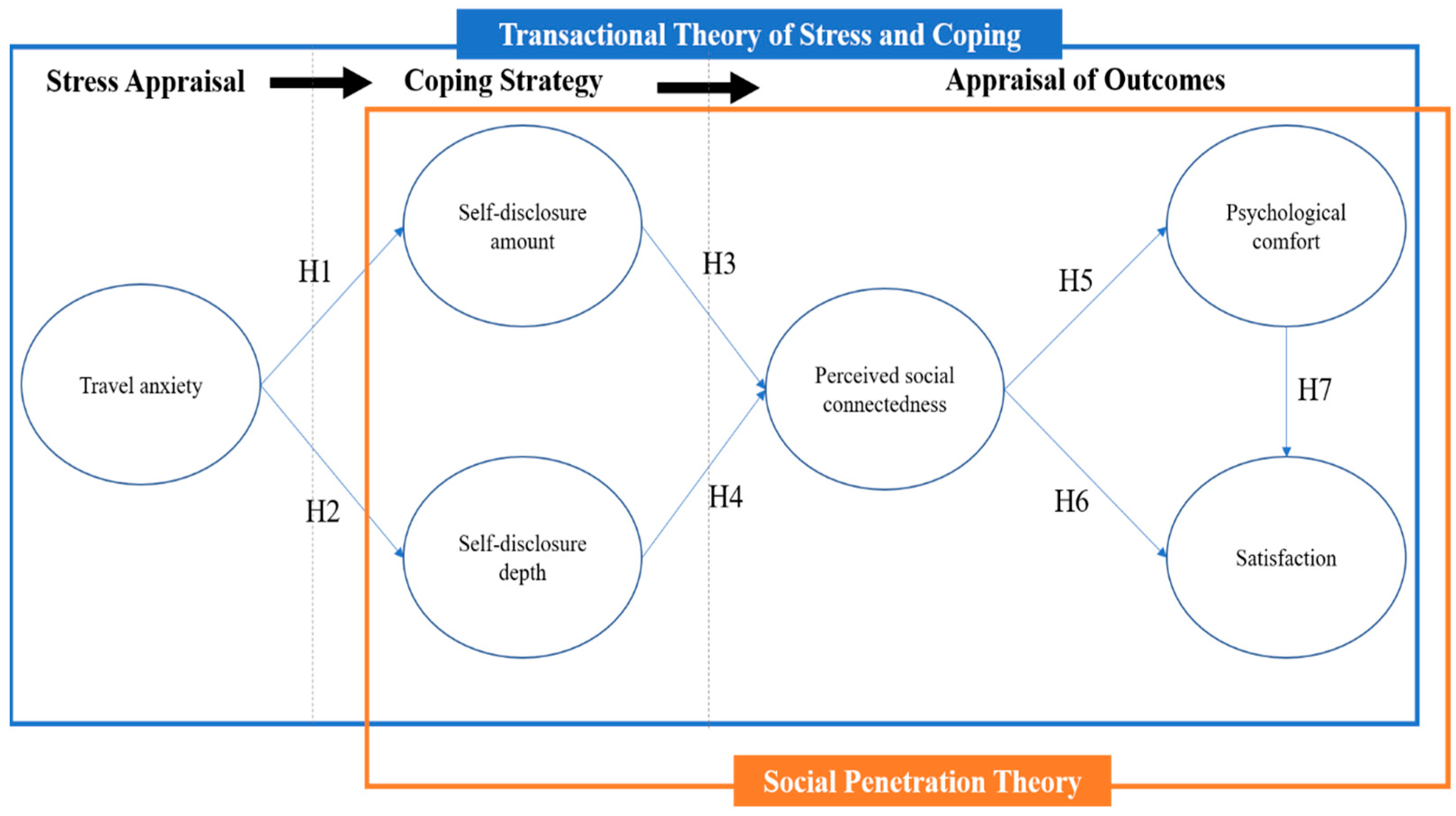

The model summarized in Figure 1 integrates TTSC and SPT, which demonstrates the transition from travel anxiety to emotional relief through social media content sharing as a coping strategy. Specifically, TTSC explains the motivational drivers, why travelers disclose (to cope), while SPT elucidates interpersonal mechanism of how this disclosure fosters social connectedness and psychological comfort. By synthesizing these frameworks, the study moves beyond seeing social media as a mere sharing tool to examining it as a dynamic system for real-time emotion regulation.

Figure 1.

Research model.

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

Data were collected via an online survey targeting individuals with prior experience sharing travel content on social media. Participants were recruited through a professional research firm in Korea to ensure demographic diversity. To align with the study’s focus, screening criteria required that respondents had shared social media posts during their most recent trip. Respondents first selected on-site trip activities from a predefined list, and only those who indicated content-sharing behavior were invited to complete the survey. To verify that self-disclosure occurred during travel, participants also reported the dates of their most recent trip and submitted sample social media content shared during that period.

Koreans were selected as the sample of this study due to their exceptionally high digital engagement and social media use. South Korea exhibits 97.9% internet penetration and 95.4% social media penetration which is among the world’s highest, with 49.3 million social media users reflecting advanced mobile infrastructure and SNS integration into daily life, including travel (Kemp, 2026). This digital-native context makes Korean tourists ideal for studying SNS-based coping and connectedness during travel.

The final sample consisted of 240 valid responses, exceeding the PLS-SEM “10-times rule,” which recommends a minimum sample ten times the highest number of structural paths directed at any single endogenous construct (Hair et al., 2017). This satisfies established guidelines for model estimation reliability in variance-based structural equation modeling.

3.2. Questionnaire Design

The survey measured key constructs using multi-item scales adapted from prior research. Travel anxiety was assessed with five items capturing discomfort and apprehension (Jiang et al., 2024; Karagöz et al., 2021). In this study, travel anxiety is treated as a unidimensional state of momentary distress. This approach aligns with the Transactional Theory of Stress and Coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), which emphasizes the magnitude of situational appraisal as the primary driver of coping behavior. To maintain model parsimony and focus on perceived stress intensity as the functional trigger for self-disclosure, this unidimensional measure follows established tourism research on situational travel anxiety (Karagöz et al., 2021). Self-disclosure amount was measured with three items on sharing frequency and volume; depth was assessed with four items capturing emotional intimacy (C. Y. Lin et al., 2021; Cao et al., 2024). Social connectedness was measured with four items on emotional closeness (Wu-Ouyang & Hu, 2023), and psychological comfort with four items reflecting emotional ease (Radia et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2023). Travel satisfaction was captured using three items evaluating overall trip experience (Ramsey et al., 2024).

All items were measured using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree” to 7 = “strongly agree”). This format was selected over 5-point alternatives to enhance response sensitivity and increase variance in observed indicators—factors that improve the reliability and discriminability of latent constructs in structural equation modeling (Hair et al., 2017; Finstad, 2010; Joshi et al., 2015). In addition, 7-point scales offer greater measurement precision while maintaining cognitive ease for respondents, and are widely adopted in tourism and PLS-SEM research.

3.3. Data Analysis

Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was employed to estimate both the measurement and structural models. This approach was chosen for its methodological fit with the study’s objectives, modeling multiple latent constructs and sequential mediators with the goal of maximizing explained variance in satisfaction (Hair et al., 2017). The integration of two theoretical frameworks (TTSC and SPT) in a novel context further necessitated an estimation method that accommodates model complexity without assuming data normality. In addition, it is robust to small sample sizes, which is particularly relevant given the small sample size in the current study (Hair et al., 2019). Given these strengths, PLS-SEM was deemed suitable for this research.

3.4. Sample Profile

A total of 240 individuals participated in the survey. The sample comprised 56.3% females and 43.8% males. The largest age group was participants in their 30s (40.8%), followed by those in their 20s and 40s. Just over half of the respondents (53.3%) were unmarried. In terms of educational attainment, the majority held at least a bachelor’s degree (78.3%), while a smaller proportion reported vocational, high school, or lower education levels. Monthly household income was diverse, with approximately one-quarter (25.4%) earning 8 million KRW or more. A detailed summary of participant demographics is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic profiles of the respondents.

4. Results

Before proceeding with the analyses, we addressed the potential for common method bias (CMB). Procedurally, respondents were assured of anonymity and confidentiality, and the questionnaire emphasized that there were no right or wrong answers to reduce evaluation apprehension. To address potential common method bias (CMB), both procedural and statistical actions were conducted. Respondents were assured of anonymity and confidentiality, and the questionnaire emphasized that there were no right or wrong answers to minimize evaluation apprehension (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Statistically, full collinearity VIFs were examined following Kock (2015), with all values ranging from 1.62 to 2.41, below the 3.3 threshold, indicating that CMB is unlikely to bias the results. Harman’s single-factor test further confirmed this, with the first factor accounting for only 37.02% of the variance—well below the 50% threshold. Following the two-stage approach recommended by Hair et al. (2017), we first assessed the measurement model to ensure the constructs exhibited acceptable levels of reliability and validity. This was followed by an evaluation of the structural model to test the proposed hypotheses and examine the explanatory power of the framework.

4.1. Measurement Model

To establish the adequacy of the measurement model, both reliability and validity were assessed, which the results are summarized in Table 2. Convergent validity was examined through item loadings and the average variance extracted (AVE). One item, “troublesome–peace of mind,” was removed from the psychological comfort construct due to its low factor loading (<0.50) and its broader ambiguity compared to the other items, which more directly reflected internal emotional ease and stress reduction central to the construct. The revised model demonstrated acceptable standardized loadings above 0.70 for all remaining items. Additionally, all AVE values ranged from 0.727 to 0.893, surpassing the minimum recommended threshold of 0.50 (Hair et al., 2017), confirming that the latent constructs share a substantial proportion of variance with their indicators.

Table 2.

Validity and reliability of the scale.

Internal consistency was verified using Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability (CR), and Rho_A coefficients. Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from 0.817 to 0.937, composite reliability scores varied from 0.891 to 0.956, and Rho_A values were between 0.831 and 0.962. These results, all exceeding the 0.70 benchmark, confirm that the constructs demonstrate strong reliability and consistency.

Discriminant validity was first examined using the Fornell–Larcker criterion. As presented in Table 3, the square roots of the average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct exceeded the corresponding inter-construct correlations, supporting the presence of discriminant validity. In line with more recent methodological recommendations (Henseler et al., 2015), the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio was also assessed to provide a more stringent evaluation. All HTMT values fell below the conventional threshold of 0.90 as outlined in Table 4, with one value slightly exceeding it at 0.902. Nonetheless, this is still considered acceptable based on Hair et al.’s (2017) guidance, which allows some flexibility in practical applications. To further validate discriminant validity, the HTMT-inference test was conducted using bootstrapped confidence intervals. The 95% confidence interval for the 0.902 value did not include 1.0, which meets the criterion proposed by Henseler et al. (2015) in confirming discriminant validity. In fact, these two are conceptually distinct in which social connectedness reflects the interpersonal experience of belonging and inclusion, whereas psychological comfort pertains to intrapersonal emotional ease.

Table 3.

Fornell-Lacker analysis.

Table 4.

HTMT (heterotrait–monotrait) analysis.

4.2. Structural Model

Prior to interpreting the structural paths, inner-model multicollinearity was assessed. All variance inflation factor (VIF) values were well below the recommended threshold of 5 (Hair et al., 2017)—and also below the more conservative cut-off of 3.3—ranging from 1.000 to 1.342. These results indicate that multicollinearity is not a concern in the model. Detailed VIF values are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Results of hypothesis testing.

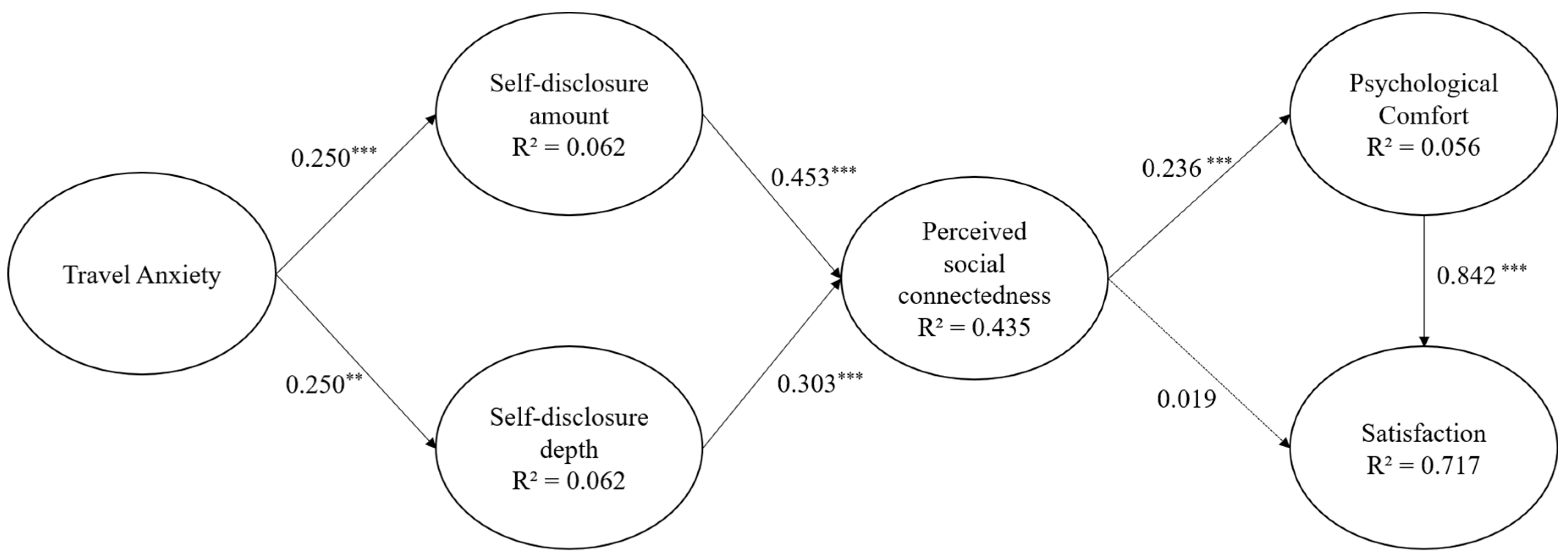

We tested hypotheses H1 through H12 using a bootstrapping procedure with 10,000 resamples. As shown in Table 5 and Figure 2, travel anxiety significantly influenced both self-disclosure amount (β = 0.250, p < 0.001) and self-disclosure depth (β = 0.250, p = 0.001), supporting H1 and H2. In turn, both self-disclosure amount (β = 0.453, p < 0.001) and depth (β = 0.303, p < 0.001) positively predicted social connectedness, supporting H3 and H4.

Figure 2.

Study results. (Notes: ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

Social connectedness significantly influenced psychological comfort (β = 0.236, p < 0.001), validating H5. However, its direct influence of social connectedness on satisfaction was not significant (β = 0.019, p = 0.648), failing to support H6. In contrast, psychological comfort had a strong positive effect on satisfaction (β = 0.842, p < 0.001), confirming H7.

To test the mediating role of psychological comfort, a bootstrapped mediation analysis was conducted. The indirect effect of social connectedness on satisfaction via psychological comfort was significant (β = 0.199, p < 0.001), while the direct path remained nonsignificant. This pattern indicates full mediation, thus supporting H8.

To assess the model’s explanatory power, we examined the R2 values of all endogenous variables. While travel anxiety accounted for only 6.2% of the variance in both self-disclosure amount and depth (), this modest effect is not unusual in behavioral research. Self-disclosure is a complex behavior influenced by diverse dispositional and contextual factors, and the purpose here was to establish whether travel anxiety activates disclosure as a coping mechanism. Despite the limited , both paths were statistically significant: travel anxiety positively predicted self-disclosure amount () and depth (), confirming its role as a meaningful antecedent in the coping process.

Building on this, self-disclosure amount and depth together explained 43.5% of the variance in perceived social connectedness (R2 = 0.435). Social connectedness then explained 5.6% of the variance in psychological comfort (R2 = 0.056). Moreover, psychological comfort alone explained 71.7% of the variance in satisfaction (R2 = 0.717), reflecting its pivotal role as the final affective outcome in the model. This strong explanatory power is conceptually consistent with the Transactional Theory of Stress and Coping, which frames emotional regulation as the key determinant of satisfaction following stress exposure.

Finally, Q2 values were assessed to evaluate the model’s predictive relevance. All endogenous constructs yielded Q2 values greater than zero, indicating acceptable predictive performance. Specifically, the Q2 values ranged from 0.041 to 0.522, surpassing the minimum threshold of 0, and suggesting that the model demonstrates small to large predictive relevance for the constructs of social connectedness, psychological comfort, and satisfaction (Hair et al., 2017).

5. Conclusions and Discussion

This study examined how travel anxiety influences tourists’ real-time coping behaviors on social networking sites (SNS), and how these behaviors affect social connectedness, psychological comfort, and satisfaction. The findings offer valuable insights that both align with and extend findings from previous studies.

First, the results confirmed that travel anxiety positively predicts both the amount and depth of self-disclosure on SNS during trips (H1 and H2). This suggests that travelers experiencing heightened anxiety are more likely to engage in real-time digital self-disclosure, both in frequency and emotional expressiveness, as a behavioral response to in situ stressors. Rather than treating self-disclosure solely as a form of expression as commonly discussed in existing studies (Bai et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2017), these findings extend its role as a coping strategy to deal with travel anxiety experienced during travel. Moreover, both the amount and depth of self-disclosure significantly enhanced perceived social connectedness (H3 and H4), confirming the finding from prior studies highlighting the relational benefits of online sharing is also valid even when triggered by anxiety (Wu-Ouyang & Hu, 2023).

Second, social connectedness significantly contributed to psychological comfort (H5), reinforcing the existing literature that emphasizes the importance of supportive social ties in reducing stress and fostering emotional well-being (W. Liu et al., 2022; Zhuang & Wang, 2024). However, in contrast to earlier findings that suggest a direct link between social connectedness and satisfaction (e.g., Li et al., 2025), this study found no such direct effect (H6). Drawing on the Transactional Theory of Stress and Coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), this result suggests that relational resources enhance satisfaction only when they reduce perceived stress first. In this context, psychological comfort functions as a critical emotional intermediary. The full mediation effect (H8) reinforces this interpretation such that for anxious travelers, satisfaction is not shaped by social connection itself, but from the emotional relief it facilitates. This adds conceptual clarity to the relational–emotional pathway proposed in prior tourism research.

Finally, the model confirmed that psychological comfort predicts satisfaction (H7), in accordance with arguments from the existing literature that emotional ease and security are key determinants of positive travel evaluations (Prayag et al., 2013).

5.1. Theoretical Implications

Findings of this research bear several valuable theoretical implications. This study contributes to the tourism literature by integrating the Transactional Theory of Stress and Coping (TTSC; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) and Social Penetration Theory (SPT; Altman & Taylor, 1973) to conceptualize how self-disclosure on social networking sites (SNS) transforms travel anxiety into satisfaction through an emotionally sequenced process. While prior research typically applies TTSC and SPT independently, this study demonstrates their integration in digitally mediated, time-sensitive contexts. Specifically, the amount and depth of self-disclosure, core dimensions of SPT, are reframed as strategic coping behaviors in response to travel anxiety. This positions digital self-disclosure not merely as an outcome of social connectedness, but as a means of emotional regulation. In doing so, the study highlights a sequential mechanism whereby self-disclosure fosters social connectedness, which in turn enables psychological comfort. This application clarifies how TTSC and SPT can be meaningfully aligned to account for real-time social behavior under stress, expanding their relevance to anxiety-inducing experiences during trip.

Moreover, this research reconceptualizes the notion of travel anxiety, expanding its scope beyond crisis-driven or high-intensity scenarios. Most prior research has framed travel anxiety as a response to extreme threats such as pandemics, terrorism, or solo travel (Karagöz et al., 2021). In contrast, this study demonstrates that low-intensity, routine stressors can also activate coping responses during travel. By focusing on everyday emotional tensions, the study shifts the theoretical lens from exceptional disruptions to ordinary psychological friction as a relevant domain of analysis. This reframing advances the tourism literature by proposing that emotional regulation is not confined to crisis contexts but is a pervasive, ongoing component of the travel experience.

This study introduces psychological comfort as a distinct emotional construct within the context of tourism experiences. In contrast to prior research that subsumes comfort within broader affective categories such as generalized positive emotion (Biswas et al., 2021), this study conceptualizes it as a discrete low-arousal state characterized by calmness, emotional security, and relief from psychological strain. Findings from this study indicate that psychological comfort directly predicts satisfaction, even in the absence of interpersonal stimuli, thereby establishing its independent explanatory relevance. This challenges the emphasis in tourism emotion research on high-arousal affective states such as joy and excitement (Costa-Feito et al., 2025), and highlights emotional safety as equally influential determinant of tourist evaluations. By reclassifying psychological comfort as a core emotional outcome, this study advances affective theory in tourism and underscores the importance of incorporating low-arousal emotions into models of tourist well-being and satisfaction.

Building on empirical support for the mediating role of psychological comfort, this study advances a theoretically integrated process model in which relational resources are transformed into satisfaction through affective regulation. Specifically, psychological comfort is conceptualized as a functional mechanism that channels emotionally supportive social bonds into positive evaluative outcomes. Grounded in the Transactional Theory of Stress and Coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), the findings demonstrate that such social ties reduce psychological strain, fostering psychological comfort. This low-arousal emotional state enhances evaluative judgments, in line with the Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions (Fredrickson, 2001). By focusing on emotional safety as a central mediating pathway, the study contributes to tourism literature by offering a process-oriented account of how socially embedded experiences shape affective appraisals—thereby extending existing models that have primarily emphasized direct or high-arousal determinants of satisfaction.

A further theoretical contribution of this study lies in reconceptualizing self-disclosure on social networking sites (SNS) as a proactive, real-time coping strategy rather than a passive outcome of pre-existing psychological states. Whereas previous research has predominantly framed self-disclosure as a response to constructs such as trust, social support needs, or ostracism (C. Y. Lin et al., 2021; Cao et al., 2024), this study positions both the amount and depth of self-disclosure as intentional, emotion-focused coping mechanisms enacted during moments of travel-related stress. This reframing extends the theoretical scope of the Transactional Theory of Stress and Coping (TTSC) by incorporating digitally mediated communication as an active regulatory behavior, and broadens the application of Social Penetration Theory (SPT) by demonstrating how self-disclosure simultaneously fulfills affective and relational functions. In doing so, the study advances a dual-function view of self-disclosure within tourism contexts, where digital interaction facilitates both emotional adjustment and social connectedness in real time.

Finally, this study contributes by reconfiguring the temporal framing of social media within tourism research. Whereas existing literature has predominantly conceptualized digital sharing as a retrospective, evaluative activity focusing on memory curation or post-experience reflection (CIT), empirical investigations into in situ sharing remain limited, despite travelers frequently engaging with social media during their trips. This study addresses that gap by demonstrating that social networking sites (SNS) serve as real-time platforms for emotional regulation during travel. By foregrounding the immediacy of digital engagement, the study introduces a novel temporal perspective that expands the conceptualization of technology’s role in shaping affective and relational experiences. This temporal shift holds theoretical significance for understanding how digital tools mediate coping processes as they unfold, and it invites further inquiry into the dynamic, in situ functions of social media in emotionally charged tourism contexts.

5.2. Practical Implications

This study offers valuable insights for tourism practitioners in managing travelers’ emotional well-being.

First, this research reframes digital content sharing as a real-time coping mechanism for travel anxiety, not just a promotional or reflective act. Tourism professionals can encourage this by creating emotionally conducive environments that feel safe and personal for sharing—such as scenic pause points or reflective digital prompts. Framing self-disclosure as a form of emotional self-care may also empower tourists to manage their stress during trip.

Second, as sharing personal thoughts or emotions were found to increase tourists’ sense of social connectedness, destinations can create opportunities for travelers to engage with others through their shared content. This could include features like curated hashtags to utilize when sharing content on social media or shared digital storytelling campaigns that connect individuals around common experiences.

Third, since social connectedness promotes psychological comfort, embedding opportunities for social bonding into the travel experience can reduce anxiety during travel. Hospitality spaces in travel destination that support interaction—such as co-working lounges, peer-to-peer chats, or themed group itineraries—can create a sense of belonging, especially for solo or anxious travelers.

Finally, given that psychological comfort was found to enhance satisfaction, tourism practitioners should consider low-effort interventions and embracing environments that minimize confusion and anxiety. These include clear multilingual signage, culturally inclusive communication, calming design elements, and staff training in embracing cultural differences. Collectively, these efforts can support travelers’ emotional security and contribute to more positive destination evaluations.

5.3. Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, although it differentiates between the amount and depth of self-disclosure, it does not consider specific content features (e.g., tone, topic, audience engagement) that may influence outcomes. Qualitative or mixed-method approaches could capture the emotional nuance and context of shared content. Second, the study did not account for participants’ baseline social media habits, which may shape the psychological effects of content sharing. Future research should consider usage intensity, platform familiarity, or dependency as potential moderators of coping efficacy. Third, the study’s small sample size may limit the generalizability of the findings. Future research should validate the proposed model with larger and more diverse samples to enhance external validity. Fourth, the study’s cross-sectional design limits its ability to capture real-time psychological states. Future research could collect data in situ during travel to explore temporal dynamics of coping behaviors. Finally, while psychological comfort was modeled as a key emotional outcome, other emotion-regulation strategies such as distraction, reappraisal, or avoidance were not included. Broader frameworks could explore how travelers alternate between digital and non-digital coping strategies during emotionally demanding travel experiences.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the Ethics Committee of the Dong-Eui University, the Code of Ethics and Conduct of Research of our University (https://irb.deu.ac.kr/menu0202/578498) (accessed on 1 July 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ainsworth, J., & Foster, J. (2017). Comfort in brick and mortar shopping experiences: Examining antecedents and consequences of comfortable retail experiences. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 35, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, I., & Taylor, D. A. (1973). Social penetration: The development of interpersonal relationships. Holt, Rinehart & Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Q., Dan, Q., Choi, Y., & Luo, S. (2025). Why we disclose on social media? Towards a dual-pathway model. Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, C., Deb, S. K., Hasan, A. A. T., & Khandakar, M. S. A. (2021). Mediating effect of tourists’ emotional involvement on the relationship between destination attributes and tourist satisfaction. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 4(4), 490–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzova, D., Sanz-Blas, S., & Cervera-Taulet, A. (2023). Co-creating emotional value in a guided tour experience: The interplay among guide’s emotional labour and tourists’ emotional intelligence and participation. Current Issues in Tourism, 26(11), 1748–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X., Wang, M., & Zhang, W. (2024). How social media trust and ostracism affect tourist self-disclosure on SNSs: The perspective of privacy management strategy. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 30(1), 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, Y., Kim, J., & Fesenmaier, D. R. (2017). Use of social media across the trip experience: An application of latent transition analysis. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 34(4), 431–443. [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Feito, A., Rodríguez-Santos, C., González-Fernández, A. M., & Marques dos Santos, J. P. (2025). The emotional paradox of short promotional videos in urban tourism: Cognitive and affective responses in decision-making under stress or joy. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 42(5), 708–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirtepe-Saygili, D. (2022). Stress, coping, and social media use. In Research anthology on combating cyber-aggression and online negativity (pp. 1036–1055). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Finstad, K. (2010). Response interpolation and scale sensitivity: Evidence against 5-point scales. Journal of Usability Studies, 5(3), 104–110. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1985). If it changes it must be a process: Study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(1), 150–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. [Google Scholar]

- Gaur, S. S., Kingshott, R. P., & Sharma, P. (2019). Managing customer relationships in emerging markets: Focal roles of relationship comfort and relationship proneness. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 29(5–6), 592–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 271–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Matthews, L. M., Matthews, R. L., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. International Journal of Multivariate Data Analysis, 1(2), 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, W., Luhmann, M., Fisher, R. R., Vohs, K. D., & Baumeister, R. F. (2014). Yes, but are they happy? Effects of trait self-control on affective well-being and life satisfaction. Journal of Personality, 82(4), 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C., Hu, X., & Zhang, Y. (2025). How important is charisma? The impacts of charismatic tour-guiding and service disclosure on tourist trust, self-disclosure, interaction quality, and emotional solidarity. Tourism Management Perspectives, 58, 101367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H., Ruan, W. Q., Li, Y. Q., & Wang, M. Y. (2023). Can companions share anxiety? The effect of travel companions on tourist anxiety during crisis situations. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 28(9), 1000–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-Y. (2016). Examining the beneficial effects of individual’s self-disclosure on the social network site. Computers in Human Behavior, 57, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G. X., Li, Y. Q., Ruan, W. Q., & Zhang, S. N. (2024). Relieving tourist anxiety during the COVID-19 epidemic: A dual perspective of the government and the tourist. Current Issues in Tourism, 27, 1095–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A., Kale, S., Chandel, S., & Pal, D. K. (2015). Likert scale: Explored and explained. British Journal of Applied Science & Technology, 7(4), 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagöz, D., Işık, C., Dogru, T., & Zhang, L. (2021). Solo female travel risks, anxiety and travel intentions: Examining the moderating role of online psychological-social support. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(11), 1595–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, S. (2026, January 31). Digital 2026: South Korea. DataReportal. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2026-south-korea (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Kirillova, K., Lehto, X. Y., & Cai, L. (2017). Existential authenticity and anxiety as outcomes: The tourist in the experience economy. International Journal of Tourism Research, 19(1), 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration, 11(4), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R. M., & Robbins, S. B. (1995). Measuring belongingness: The social connectedness and the social assurance scales. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 42(2), 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S., Moon, H., Ko, J., Cankaya, B., Caine, E., & You, S. (2023). Social connectedness and mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in a community sample in Korea. PLoS ONE, 18(10), e0292219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. (2025). Travel alienation and coping strategies of international students: A qualitative exploration of the role of social support. International Journal of Tourism Research, 27(4), e70100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X., Wu, H., Deng, Z., & Ye, Q. (2023). Self-disclosure, social support and postpartum depressive mood in online social networks: A social penetration theory perspective. Information Technology & People, 36(1), 433–453. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L., Yu, M., Choi, H.-S. C., & Lee, H. (2025). Exploring the psychological benefits of value co-creation in tourism: Enhancing hedonic and eudaimonic well-being through empowerment, social connectedness, and positive emotions. Journal of Vacation Marketing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B., Fu, X., & Murphy, K. (2024). Investigating the foodstagramming mechanism: A customer-dominant logic perspective of customer engagement. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 58, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. Y., Chou, E. Y., & Huang, H. C. (2021). They support, so we talk: The effects of other users on self-disclosure on social networking sites. Information Technology & People, 34(3), 1039–1064. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H., Zhang, M., Gursoy, D., & Fu, X. (2019). Impact of tourist-to-tourist interaction on tourism experience: The mediating role of cohesion and intimacy. Annals of Tourism Research, 76, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M., Xu, J., Li, S., & Wei, M. (2023). Engaging customers with online restaurant community through mutual disclosure amid the COVID-19 pandemic: The roles of customer trust and swift guanxi. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 56, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W., Xu, W., & Wu, M. (2022). The effect of tourist-to-tourist interaction on life satisfaction: A mediation role of social connectedness. Sustainability, 14(23), 16257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J. M., & Lam, C. F. (2020). Travel anxiety, risk attitude and travel intentions towards “travel bubble” destinations in Hong Kong. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21), 7859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michikyan, M., Subrahmanyam, K., Regan, P., Castillo, L. G., Ham, L., Harkness, A., & Schwartz, S. J. (2023). Social connectedness and negative emotion modulation: Social media use for coping among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Emerging Adulthood, 11(4), 1039–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabity-Grover, T., Cheung, C. M., & Thatcher, J. B. (2020). Inside out and outside in: How the COVID-19 pandemic affects self-disclosure on social media. International Journal of Information Management, 55, 102188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterkin, K. Y., Badu-Baiden, F., & Alhuqbani, F. M. (2024). Stress and coping: Exploring the experiences of travellers during COVID-19 hotel quarantine. Tourism Recreation Research, 49(5), 1063–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizam, A., Neumann, Y., & Reichel, A. (1978). Dimensions of tourist satisfaction with a destination area. Annals of Tourism Research, 5(3), 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, S., & Tolkach, D. (2022). Affective and coping responses to quarantine hotel stays. Stress and Health, 38(4), 768–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prayag, G., Hosany, S., & Odeh, K. (2013). The role of tourists’ emotional experiences and satisfaction in understanding behavioral intentions. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 2(2), 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. In Culture and politics: A reader (pp. 223–234). Palgrave Macmillan US. [Google Scholar]

- Radia, K. N., Purohit, S., Desai, S., & Nenavani, J. (2022). Psychological comfort in service relationships: A mixed-method approach. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 64, 102824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rains, S. A., & Keating, D. M. (2015). Health blogging: An examination of the outcomes associated with making public, written disclosures about health. Communication Research, 42(1), 107–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, J. R., Zhang, Y., Lorenz, M. P., & Hosany, S. (2024). Travel stress, leisure exploration, and trip satisfaction: The mediating role of travel adjustment. Journal of Travel Research. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar]

- Rather, R. A., Hollebeek, L. D., Wait, M., & Khan, I. (2025). Tourists’ perceived travel risk, desire to travel, travel engagement, and subjective wellbeing: The moderating role of emotion regulation. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S., Ahmad, J., Khan, A., & Alotaibi, K. A. (2025). Frequency of leisure travel and psychological well-being in pharmacists: The sequential mediating roles of perceived stress and social support. BMC Psychology, 13(1), 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimé, B. (2009). Emotion elicits the social sharing of emotion: Theory and empirical review. Emotion Review, 1(1), 60–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spake, D. F., Beatty, S. E., Brockman, B. K., & Crutchfield, T. N. (2003). Consumer comfort in service relationships: Measurement and importance. Journal of Service Research, 5(4), 316–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidwell, L. C., & Walther, J. B. (2002). Computer-mediated communication effects on disclosure, impressions, and interpersonal evaluations: Getting to know one another a bit at a time. Human Communication Research, 28(3), 317–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. (2025). Travel through time: Harnessing nostalgic Instagram content to overcome travel barriers. Journal of Vacation Marketing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Kirillova, K., & Lehto, X. (2017). Travelers’ food experience sharing on social network sites. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 34(5), 680–693. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S., Lehto, X., Cai, L., Behnke, C., & Kirillova, K. (2023). Travelers’ psychological comfort with local food experiences and place attachment. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 47(8), 1453–1477. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeless, L. R., & Grotz, J. (1976). Conceptualization and measurement of reported self-disclosure. Human Communication Research, 2(4), 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfers, L. N., & Utz, S. (2022). Social media use, stress, and coping. Current Opinion in Psychology, 45, 101305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu-Ouyang, B., & Hu, Y. (2023). The effects of pandemic-related fear on social connectedness through social media use and self-disclosure. Journal of Media Psychology, 35(2), 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H., Shen, C., Wei, Y., & Xiong, H. (2024). The visual effects of emoji in social media travel sharing on user engagement. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 61, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J., & Hwang, J. (2025). Information overload and tourists’ booking discontinuance intention: An application of the transactional theory of stress and coping. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 62, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S., Braun, E., & Gyimóthy, S. (2021). Too afraid to travel? Development of a pandemic (COVID-19) anxiety travel scale (PATS). Tourism Management, 84, 104286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R. (2017). The stress-buffering effect of self-disclosure on Facebook: An examination of stressful life events, social support, and mental health among college students. Computers in Human Behavior, 75, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Liu, Y., & Wang, Z. (2024). The impact of SNS and COVID-19-related stress on psychological outcomes: An application of the transactional theory of stress and coping. Computers in Human Behavior, 149, 107944. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, G., Hu, J., Du, Q., & Xiang, M. (2024). Impact of sincere social interaction on tourist citizenship behavior—Perspective from “self” and “relationships”. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 61, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X., & Wang, Y. (2024). Social support and travel: Enhancing relationships, communication, and understanding for travel companions. International Journal of Tourism Research, 26(4), e2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.