Abstract

This study investigates the deep-seated impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on Macao, a mono-economy extremely dependent on the single factor of “tourism mobility”. We investigate a counter-intuitive phenomenon observed during the 2020–2022 shock: the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) declined significantly, suggesting “apparent diversification”. Using counterfactual simulations and a Two-Way Fixed Effects (TWFE) model, we quantitatively deconstruct this “resilience illusion”. The results confirm that the decline in the HHI was driven entirely by the “denominator effect” triggered by the collapse of the dominant industry’s (gaming) GVA; if the impact of this recession is excluded, the Counterfactual HHI was even higher than pre-pandemic levels, indicating that the structure did not undergo substantive optimization. Furthermore, inferential statistical tests confirmed the existence of significant “structural lag” in the labor market. This study further reveals a dual divergence mechanism based on “skill specificity”: in sectors with high skill universality (e.g., transport and catering), a structural shift toward “workforce casualization” occurred, manifested by a significant decline in the full-time ratio; conversely, in sectors with strong skill specificity (e.g., gaming and hospitality), firms tended toward “labor hoarding”. This study exposes the macro-indicator trap faced by tourism mono-economies under extreme shocks and provides new micro-evidence for understanding the heterogeneous scars in the service labor market.

1. Introduction

As a highly open micro-economy, Macao’s economic structure has demonstrated an extreme dependence on a single industry over the past few decades (Zeng & Zhang, 2012; L. Sheng, 2020). Since the liberalization of gaming concessions in 2002, the gaming industry—and the associated service sectors it drives, such as tourism, hospitality, and retail—has rapidly evolved into the absolute pillar of the economy (Siu, 2023). While generating significant growth, this model tethered the economy to the singular factor of “tourism mobility” (Yuan & Liang, 2013). Consequently, Macao’s fiscal revenue, Gross Value Added (GVA), and employment structure became heavily dependent on tourist arrivals and Gross Gaming Revenue (GGR) (Lv, 2023). This monolithic industrial structure has severely challenged the region’s economic resilience, rendering it highly susceptible to external shocks (Y. Han et al., 2024; Zhu & Tang, 2018). This structural fragility is not an isolated phenomenon but rather a classic manifestation of “regional lock-in” within evolutionary economic geography (EEG). Recent studies indicate that resource-dependent communities often succumb to path dependence due to institutional and allocative inertia, weakening their adaptive capacity (Haisch, 2018; Hu et al., 2025). Similarly, Hall et al. (2024) emphasize that while crises offer opportunities for change, “lock-in effects” frequently constrain destination diversification. This makes the recovery process fraught with uncertainty, making the recovery process fraught with uncertainty and path competition. For Macao, this lock-in effect is not merely reflected in the industrial structure but is deeply embedded in the skills supply of the labor market and the broader social fabric. Consequently, the economic system exhibits extreme sensitivity and vulnerability when facing shocks that sever mobility, such as COVID-19.

The COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2022) constituted a unique and targeted external shock. Distinct from traditional financial crises or economic cycle recessions, the transmission mechanism of this crisis was highly precise: global travel restrictions and stringent public health policies directly severed the “tourism mobility” upon which Macao’s economy is most dependent (Z. Chen & Yang, 2022). For economies highly reliant on tourism, this “travel shock” inflicted disproportionately immense economic losses (Milesi-Ferretti, 2024; Jaffur et al., 2024). Against this backdrop, the “1 + 4” adequate diversification development strategy—actively promoted by the Macao SAR government in recent years to consolidate the gaming and tourism industry while vigorously developing emerging sectors such as finance, technology, and MICE—faced an extreme stress test (Z. Chen, 2024).

During the period when the pandemic shock was most severe and the macro-economy faced tremendous downward pressure (2020–2022), a counter-intuitive macroeconomic phenomenon emerged. Preliminary data reveals that the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) of industrial concentration in Macao actually showed a distinct downward trend during this period. For tourism destination managers seeking economic resilience, a decline in the HHI is typically interpreted as a positive signal of structural optimization and the effectiveness of diversification strategies. However, the appearance of this signal precisely when the dominant industry (gaming tourism) was shrinking dramatically due to external shocks raises the core puzzle of this study. Although existing literature has extensively explored the post-disaster recovery of tourism destinations, the majority of studies focus on forecasting recovery trajectories or measuring the “bounce-back speed” of aggregate indicators (e.g., tourist arrivals, GDP) (Cheng et al., 2024; C. Sheng & Li, 2025). Nevertheless, an increasing number of scholars are beginning to warn of the divergence between macro indicators and social reality. For instance, Clò et al. (2025) found that post-disaster GDP growth might mask exacerbated social vulnerability, creating a mirage of “creative destruction” (Clò et al., 2025); similarly, Galiano et al. (2025) utilized counterfactual simulations to reveal the asymmetry of tourism mobility recovery in the post-pandemic era (Galiano et al., 2025). Regrettably, in tourism economies dominated by a single industry, the phenomenon of “spurious optimization” in statistical indicators triggered by the collapse of the leading sector has not yet received sufficient theoretical attention or empirical examination. Existing research often tacitly assumes that a decline in HHI equates to an improvement in diversification, ignoring the “resilience illusion” that may arise from the drastic contraction of the economic denominator (total economic output) under extreme shocks. This theoretical gap requires urgent attention.

Accordingly, this study proposes the first research question (RQ1): Does the trend of “apparent diversification” observed during the pandemic reflect the initial success of the “1 + 4” diversification strategy, or is it merely a “resilience illusion” driven by the “stalling of the tourism engine”? What is the underlying mechanism? Furthermore, such an acute and targeted external shock inevitably exerts profound impacts on a highly specialized economic structure. The gaming-tourism cluster not only contributes the majority of GVA but also serves as the core reservoir for employment absorption (Liu et al., 2020). When such a dominant industry suffers severe devastation, its impact on the labor market may exhibit latency and persistence. Therefore, this study proposes the second research question (RQ2): What long-term consequences has this shock inflicted on Macao’s highly specialized labor market? Is the recovery of GVA synchronous with that of employment and wages? Do “structural lags” or “scarring effects” exist?

To address these questions, the core objective of this study is to deconstruct this “resilience illusion” and identify the shocks sustained by the labor market. The central thesis is that the decline in the HHI was not derived from the growth of emerging industries. Instead, it was driven by the disproportionate and precipitous decline of “visitor-facing sectors” (e.g., gaming, hospitality, retail)—which constitute the absolute bulk of GVA—due to the interruption of tourism mobility. When the total GVA (the denominator) shrank drastically due to the collapse of the dominant industry, the GVA share of non-visitor-facing sectors (e.g., finance, public administration) passively increased, thereby mathematically manufacturing a facade of structural optimization.

At the labor market level, this study further reveals that the shock caused significant “scarring effects”. We argue that within the tourism cluster, a “pronounced divergence” emerged between the recovery speed of GVA and that of employment and wages. This structural lag further manifests heterogeneously as a decline in “job quality”. Particularly in sectors with high labor substitutability (e.g., transport, catering), firms—seeking to hedge against future risks—have tended toward “workforce casualization”, resulting in a structural shift in full-time employment rates.

The marginal contributions of this study are primarily reflected in two dimensions. At the macro level, incorporating an EEG perspective, we highlight the counterfactual HHI analysis as a core methodological contribution. By constructing counterfactual simulations, we effectively isolate the “denominator effect” and quantify the “resilience illusion” in a mono-cultural tourism economy for the first time, revealing the misleading nature of macro indicators under extreme shocks. At the micro level, we extend the analysis of the tourism labor market from mere quantitative recovery to structural “precarity”. As Baum et al. (2020) noted, the pandemic essentially amplified the normality of “precarious work” that has long existed in the tourism industry. By identifying the trend of “workforce casualization”, this study responds to recent discussions regarding the “dual burden” (job insecurity and health risks) faced by tourism practitioners during crises (H. Han et al., 2022; Aguiar-Quintana et al., 2021), filling the theoretical gap concerning the divergence between “metric prosperity and substantive scarring” in single-industry dependent economies.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews relevant theories on path dependence, diversification assessment, and labor market “scarring effects”, and constructs the analytical hypotheses. Section 3 details the data sources, definitions of key variables (specifically the classification of “visitor-facing” sectors), and the empirical strategy. Section 4 presents the empirical results, first employing the two-way fixed effects (TWFE) model to deconstruct the mechanism of the “resilience illusion”, followed by descriptive analyses and structural comparisons to demonstrate the “pronounced divergence” and changes in “job quality” within the labor market. Section 5 discusses the theoretical implications of the findings for the application of macro indicators, as well as policy implications for the “1 + 4” diversification strategy and labor market repair. Section 6 concludes the study.

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

2.1. Evolutionary Resilience and the Vulnerability of Mono-Specialized Destinations

Traditional research on regional resilience has predominantly focused on an economy’s ability to return to an equilibrium state following a shock (engineering resilience). However, from the perspective of EEG, resilience is redefined as the capacity of a regional economy to adapt to new environments and unlock new development paths (evolutionary resilience). For island or micro-economies heavily reliant on tourism, this adaptive capacity is often severely constrained by historical paths. Yigitcanlar et al. (2018) point out that tourism islands dependent on a single economic driver exhibit extreme vulnerability during global crises because their resource allocation has been locked into specific industrial trajectories.

This “lock-in effect” has been further elucidated in recent studies on destination transitions. Through a case analysis of post-earthquake recovery in New Zealand, Hall et al. (2024) found that although crises are often viewed as opportunities for change, existing stakeholder networks and institutional arrangements frequently generate a powerful “negative lock-in”, impeding the destination’s leap toward more diverse paths. Similarly, a dynamic analysis of inter-sectoral linkages in Tibet by Hu et al. (2025) confirmed that path dependence renders it difficult for traditional service sectors to achieve a structural transition toward high value-added industries in the short term.

Specifically at the tourism organizational level, Jiang et al. (2019) propose that organizations lacking dynamic capabilities often resort to passive resource retrenchment rather than active reconfiguration of routines when facing disruptive events. For Macao, this mono-specialized structure dominated by the gaming-tourism industry implies not only a lack of risk-diversification capabilities but also a deficiency in “path plasticity” within the entire economic system when facing shocks that sever mobility, such as COVID-19. Consequently, the economy is highly prone to falling into the dual dilemma of deep recession and sluggish recovery.

2.2. “Resilience Illusion” and Diversification Assessment

Industrial concentration is a standard metric for assessing market structure and diversification levels, among which the HHI is widely utilized due to its sensitivity to the market share information of all participants (Kvålseth, 2022a; Dai et al., 2019). The HHI measures concentration by calculating the sum of the squares of the market shares (typically measured by output, value added, or employment) of each firm (or in this context, each industry) within the market. Generally, a higher HHI value indicates that the market (or economic structure) is concentrated among a few dominant entities; conversely, a lower HHI is typically interpreted as a sign of intense market competition or a diversified economic structure (Rakshit & Bardhan, 2023). Consequently, a decline in the HHI is often viewed as a positive signal of progress in industrial diversification.

However, as a summary measure, the drivers behind changes in the HHI can be complex, necessitating extreme caution in interpretation, especially in the face of severe external shocks (Kvålseth, 2022b). The HHI formula dictates that it is simultaneously influenced by the relative shares of industries and the number of industries (though the latter remains fixed in this context). When an external shock causes drastic fluctuations in total economic output, the HHI may exhibit misleading changes due to the “denominator effect” (Hartwig, 2008). Specifically, if a dominant industry collapses, the relative shares of smaller sectors mechanically rise even if their absolute output remains constant. This mathematical artifact can create a “resilience illusion”, falsely signaling structural diversification (Humphries & Sarasúa, 2012), causing its output (the numerator in share calculation) to shrink precipitously, the relative share of other smaller sectors within the diminished total economy (the denominator) will passively rise, even if their absolute output remains constant or declines slightly. Since the HHI calculates the sum of squared shares, such relative share fluctuations triggered by the collapse of a dominant industry are highly likely to lead to a decline in the HHI, thereby manufacturing a “resilience illusion” that the economic structure is trending toward diversification (Humphries & Sarasúa, 2012).

This phenomenon shares similarities with “structural breaks” in economics (Herrera & Pesavento, 2005) or the “Dutch Disease” effect triggered by specific shocks (Corden, 1984; Reisinezhad, 2023). In the classic Dutch Disease model, the abnormal boom of one sector (e.g., natural resources) squeezes the development space of other tradable sectors (e.g., manufacturing) through the “resource movement effect” and the “spending effect”, leading to structural distortion (Forsyth et al., 2014). Although the context of this study is the recession rather than the boom of a leading industry, the core mechanism—whereby a drastic fluctuation (whether expansion or contraction) in one sector distorts the relative shares of others—is analogous. The impact of COVID-19 on Macao’s visitor-facing sectors can be viewed as a severe “structural break”, and the resulting decline in the HHI may not represent a genuine diversification process.

Based on the theoretical analysis above, this study proposes the first core hypothesis:

H1 (Resilience Illusion Hypothesis).

The impact of the pandemic on “tourism mobility” will disproportionately and severely batter Macao’s dominant “visitor-facing” sectors. This will cause a substantial contraction in the GVA of these sectors (which constitutes the primary component of Macao’s total GVA). Consequently, the “denominator effect” mechanically drives a passive increase in the relative GVA share of “non-visitor-facing” sectors, reducing the overall HHI. This creates a “resilience illusion”: a statistical appearance of diversification that is, in reality, driven by the decay of the dominant industry.

2.3. Crisis Recovery in Tourism and Labor Precarity

While traditional economic crisis theories focus on the lagged recovery of unemployment rates, the impact of COVID-19 on the tourism labor market has exhibited a unique structural characteristic: the intensification of “precarity”. Baum et al. (2020) poignantly noted that the pandemic did not create a new labor crisis but rather extremely amplified the “normality” of low pay, lack of social protection, and high turnover that has long existed in the tourism industry. This shock subjected practitioners to the dual pressure of infection risks and dismissal threats, significantly weakening their organizational commitment and job performance (Aguiar-Quintana et al., 2021; C.-C. Chen et al., 2022).

Recent empirical studies have revealed how this precarity translates into structural “scarring”. Research by Jung et al. (2021) and Bajrami et al. (2021) demonstrates that high job insecurity directly drives the turnover intention of skilled employees, leading to a permanent loss of human capital. Crucially, this impact exhibits significant heterogeneity across different skill types. By comparing airline and hotel employees, H. Han et al. (2022) found that due to differences in skill specificity, distinct sectors display markedly different vulnerabilities and recovery patterns in the face of shocks.

Regarding corporate response strategies, to alleviate the tension between precipitous revenue decline and operating costs, a multitude of tourism enterprises have pivoted toward a strategy of “workforce casualization”. Vo-Thanh et al. (2021) pointed out that if crisis response measures neglect employee well-being, they will exacerbate employees’ psychological distress and deviant behavior. This structural degradation from standard full-time employment to non-standard, temporary employment constitutes the core “scar” focused on by this study—namely, a hidden but profound deterioration in job quality masked by the superficial appearance of aggregate recovery.

Based on the analysis above, this study proposes the second core hypothesis:

H2 (Structural Lag Hypothesis).

The pandemic shock will inflict a significant “scarring effect” or “structural lag” on the labor market of Macao’s “visitor-facing” sectors. Specifically: (a) After the GVA of the sector begins to recover, the recovery speed of its total employment and average wages will exhibit a pronounced divergence (lag); (b) To hedge against future uncertainty risks and reduce rigid costs, firms in the impacted sectors (especially those with high labor substitutability) will tend to adjust their employment structures, leading to a “decline in job quality”, exemplified by a decrease in full-time employment rates (the phenomenon of “workforce casualization”).

3. Research Design

3.1. Construction of the Policy Severity Index

To precisely capture the intensity and temporal dimension of the Pandemic shock, this study constructs a comprehensive “policy severity index” (PSI) based on a systematic review of cross-border control policies implemented in the Macao SAR during the pandemic (primarily from early 2020 to early 2023). Given Macao’s high dependence on tourism mobility (Zeng & Zhang, 2012), the stringency of border control measures directly reflects the intensity of the external shock.

We distilled four core dimensions from the complex and evolving epidemic prevention policies to quantify their severity. Each dimension was assigned a score based on the degree to which it restricted tourism mobility. The construction methodology is as follows:

Step 1: Dimension identification and scoring. Based on a qualitative analysis of official announcements (see Appendix A.1), we identified four key policy dimensions and established corresponding scoring criteria, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Construction Dimensions and Scoring Criteria for the Policy Severity Index.

Step 2: Monthly scoring. The research team assigned monthly scores (from January 2020 to February 2023) to the four dimensions based on the prevailing policies enforced each month.

Step 3: Dimension normalization. To ensure comparability across dimensions when synthesizing the aggregate index and to avoid weighting imbalances caused by different scoring ranges, we normalized the raw score of each dimension to a 0–1 interval:

where represents the monthly raw score of the dimension, and denotes the maximum possible score for that dimension (i.e., 4.0 for Dim1 and Dim2, and 2.0 for Dim3 and Dim4).

Step 4: Index synthesis. The final “policy severity index” is calculated as the arithmetic mean of the four normalized dimension scores for the month:

This composite index ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating stricter border control policies and greater impediments to tourism mobility in that month. This index will serve as the core explanatory variable for measuring the intensity of the exogenous shock in the subsequent econometric models. To verify robustness, we also constructed an alternative index using “clearance-oriented” weights. This sensitivity check aims to rule out potential bias arising from subjectivity in weight setting.

3.2. Data Sources and Variable Definitions

The macroeconomic and labor market data utilized in this study were primarily sourced from official statistics published by the Direcção dos Serviços de Estatística e Censos (DSEC) of the Macao SAR. Based on these data, we constructed two core panel datasets for empirical analysis: an annual panel dataset covering the period from 2008 to 2023, primarily used to analyze changes in GVA; and a panel dataset with higher frequency (quarterly or semi-annual) to analyze labor market dynamics, where the specific time span depends on variable availability.

To test the core hypotheses of this study, we defined the following key variables, as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Definitions and Descriptions of Key Variables.

3.3. Empirical Strategy

To test the two core hypotheses proposed in this study, we adopted a two-stage empirical strategy. The first stage employs econometric models to test H1, while the second stage, given data characteristic limitations, utilizes rigorous descriptive and visualization analyses to examine H2.

3.3.1. Strategy I: Deconstructing the “Resilience Illusion” (H1)

To verify H1—that “apparent diversification” stems from disproportionate shocks to the dominant industry—we designed a two-step identification strategy:

First, at the macro level, we employ ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models (results in Table 2) to verify the transmission channels of the shock. We use the policy stringency (PolicySeverity) as the exogenous shock to examine its impact on key mediating variables—tourist arrivals (Log(TouristArrivals)) and gross gaming revenue (Log(GGR))—and further test the relationship between these mediators and industrial concentration (HHI).

Second, at the industry level, we employ the TWFE model to identify the heterogeneous impacts of the pandemic shock on the GVA of different types of industries (Angrist & Pischke, 2009). The TWFE model is a classic method for evaluating policy shocks (Baltagi et al., 2024; Imai & Kim, 2021), capable of simultaneously controlling for industry-specific factors that are time-invariant (e.g., industry nature, business model) and time-specific factors that are invariant across industries (e.g., macroeconomic cycles, overall pandemic phases) (Zheng et al., 2023; Lee et al., 2020). Our baseline model is specified as follows:

where i denotes the industry and denotes the year. is the logarithm of the value added of industry in year . represents industry fixed effects, and represents year fixed effects. is a dummy variable marking the pandemic shock (taking the value of 1 for 2020 and onwards). The core explanatory variable is the interaction term . Its coefficient, , captures the difference in the average GVA shock suffered by visitor-facing sectors (treatment group) relative to non-visitor-facing sectors (control group) after the outbreak. According to the expectation of H1, should be significantly negative. Furthermore, to deeply examine the transmission mechanism proposed in H1, we replace with specific shock transmission variables, such as Log(TouristArrivals) or Log(GGR), to construct the following mechanism test model:

In this model, if the coefficient of the interaction term involving the mechanism variable (e.g., Log(GGR)) is significantly positive, it provides robust evidence that the shock exerted a disproportionate negative impact on visitor-facing sectors through this specific channel (i.e., the collapse of gaming revenue).

Third, to precisely quantify the specific contribution of the “denominator effect” to the decline in HHI, this study further employs a counterfactual simulation method. By constructing a counterfactual scenario where the GVA of the gaming industry remains constant, we calculate and compare the evolutionary trajectories of the “Observed HHI” and the “Counterfactual HHI”, thereby intuitively deconstructing the mathematical origin of the “resilience illusion”.

3.3.2. Strategy II: Demonstrating the “Structural Lag Effect” (H2)

To comprehensively test H2 (the scarring effect on the labor market), this study adopts a mixed analytical strategy combining “trend visualization” with “inferential statistical tests”.

Step 1 (Dynamic trajectory comparison): We categorize industries into “visitor-facing” and “non-visitor-facing” groups and plot the recovery rate curves for GVA, employment, and average earnings (using 2019 as the baseline) to visually identify potential “divergence gaps”.

Step 2 (Inferential statistical testing): We introduce rigorous statistical tests. Given the small industry sample size (N = 14) and the potential violation of the normality assumption, we employ both parametric tests (Welch’s t-test, assuming unequal variances) and non-parametric tests (Mann–Whitney U test) to test for significant differences in the average post-shock recovery rates between the two groups. This dual-testing strategy effectively mitigates estimation biases arising from small samples, ensuring the robustness of the conclusions.

Step 3 (In-depth analysis of job quality): Finally, delving into the micro-level, we calculate changes in the “full-time ratio” of key sectors to verify the structural shift toward “workforce casualization”.

4. Empirical Results

This section presents the empirical results used to test the research hypotheses. We first report the descriptive statistics of the main variables (Section 4.1), then deconstruct the puzzle of the “resilience illusion” under the pandemic shock (Section 4.2), and finally provide an in-depth analysis of the “structural lag” and “scarring effects” observed in the labor market (Section 4.3).

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

This study constructs annual (2008–2023) and quarterly panel datasets covering 14 industries. Table 3 reports the descriptive statistics of the core variables utilized for analysis.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics of Key Variables.

As shown in Table 3, the data exhibit substantial volatility, reflecting the unique characteristics of Macao’s economic structure and the severity of the pandemic shock. In the annual data, the standard deviation of industrial GVA (51,086.45 million MOP) is far higher than its mean, and there is a gap of hundreds of times between the maximum and minimum values. This highlights the massive scale disparity between visitor-facing sectors (e.g., the gaming industry) and other industries.

The variables that best capture the pandemic shock are “tourist arrivals” and “gross gaming revenue” (GGR). In the quarterly data, the extremely high standard deviation of “Tourist Arrivals” intuitively reflects the extreme situation where tourism mobility came to a near standstill during the pandemic. Correspondingly, GGR—as the core tourism output—experienced a precipitous decline. Meanwhile, the high volatility of the “Policy Severity” index indicates significant temporal variation in the intensity of controls targeting tourism mobility during the study period. These characteristics provide the necessary data foundation for the subsequent identification of the heterogeneous impacts of the shock.

4.2. Deconstructing the “Resilience Illusion”

4.2.1. The Puzzle of Apparent Diversification Trends

Industrial concentration (HHI) is a standard metric for measuring the level of economic structure diversification (Kvålseth, 2022a). For tourism destination managers, a decline in the HHI is typically interpreted as a positive signal that the industrial structure is trending toward equilibrium and that diversification strategies are making progress. However, under the specific context of the Pandemic shock, Macao’s macroeconomic data exhibit a counter-intuitive phenomenon, constituting the core puzzle of this study (Milesi-Ferretti, 2024).

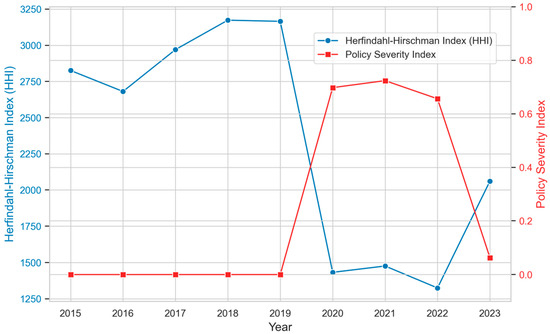

Figure 1 intuitively illustrates this core puzzle. The data show that prior to the outbreak (2015–2019), Macao’s HHI maintained a high level between 2680.82 and 3173.50, reflecting the economic structure’s high dependence on a single industry. However, following the outbreak in 2020, as cross-border control measures (the “Policy Severity Index”)—serving as a proxy for the exogenous shock—surged (0.70 in 2020, peaking at 0.72 in 2021), the HHI experienced a precipitous decline. It plummeted from 3165.48 in 2019 to 1432.40 in 2020, further bottoming out at 1324.58 in 2022.

Figure 1.

Industrial Concentration (HHI) and Policy Severity in Macao (2015–2023).

This rapid decline in the HHI, occurring precisely during the period of most severe external shock and macroeconomic depression, presents a trend of “apparent diversification” (Humphries & Sarasúa, 2012). The significant negative correlation between the HHI and Policy Severity (Figure 1) contradicts the traditional view of structural optimization. Instead, it suggests a “resilience illusion” driven by the disproportionate contraction of the dominant gaming industry, rather than the endogenous growth of emerging sectors (Siu, 2023). In 2023, as pandemic policies relaxed and tourism mobility recovered, the HHI rapidly rebounded, further confirming this point. To verify hypothesis H1, we must first validate the transmission channel of the shock at the macro level, and subsequently identify its heterogeneous impacts at the industry level.

4.2.2. Macro Mediation Pathways of Policy Shock Transmission

To initiate the verification of hypothesis H1—specifically, that the pandemic shock was transmitted by precisely targeting the critical element of “tourism mobility”—this study first conducted a macro-level OLS path analysis using annual time-series data (N = 9, 2015–2023). As shown in Table 4, we examined the impact of the “Policy Severity” index on two core mediating variables—“Tourist Arrivals” (Log(TouristArrivals)) and “Gross Gaming Revenue” (Log(GGR))—while simultaneously quantifying its macro-level association with the HHI.

Table 4.

OLS Regression Results of Macro Shock Pathways (Annual Data, 2015–2023).

The results in Table 4 clearly verify the transmission mechanism of the shock. Models (2) and (3) show that “Policy Severity” exerts a significant negative impact on both Log(TouristArrivals) and Log(GGR). This provides compelling preliminary evidence at the macro level, confirming that Macao’s stringent cross-border control measures (acting as an exogenous shock) indeed directly and precisely severed tourism mobility, leading to the collapse of gaming tourism revenue—the economy’s lifeline (Jaffur et al., 2024; Wu et al., 2025).

Model (1) quantifies the “puzzle” presented in Figure 1 at the macro level: the stricter the policy (i.e., the greater the shock), the lower the HHI (implying apparent diversification). In summary, Table 4 confirms the logical premise of H1: the policy shock triggered the collapse of tourism mobility and core revenues, which coincided chronologically with the decline in the HHI. To reveal the true source of this apparent diversification, it is imperative to delve into the industry level to examine whether this shock exerted disproportionate heterogeneous impacts on different types of sectors (Martin & Sunley, 2006).

4.2.3. Core Identification of Heterogeneous Impacts: TWFE Results

The core of hypothesis H1 lies in demonstrating that the shock exerted a disproportionate impact on the GVA of industries. To this end, we employed the TWFE model to isolate the heterogeneous impacts of the shock on “visitor-facing” sectors (Angrist & Pischke, 2009). The results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

TWFE Regression Results of Heterogeneous Impacts on Industry GVA (Dependent Variable: Log(GVA)).

The results in Table 5 provide core empirical support for hypothesis H1. Model (6), adopting a standard DiD specification, shows that the coefficient of the interaction term is significantly negative (β = −0.534, p = 0.099), indicating that the pandemic shock inflicted a disproportionate and significant negative blow to the GVA of “visitor-facing” sectors.

The mechanism tests in Models (2) and (3) are even more critical. Model (2) reveals that the sensitivity of GVA in these sectors to Log(TouristArrivals) is significantly positive; similarly, Model (3) shows that their sensitivity to Log(GGR) is also significantly positive. These two positive coefficients clearly demonstrate that the survival and development of visitor-facing sectors are highly dependent on tourism mobility (Yuan & Liang, 2013). Consequently, when tourist arrivals collapsed due to the pandemic, these sectors suffered devastating losses, whereas non-visitor-facing sectors were less affected. This precisely validates the transmission mechanism proposed in H1.

Regarding robustness, in Model (4), where the gaming industry was excluded, the coefficient lost its significance. This provides compelling evidence that the observed heterogeneous shock was primarily driven by the dominant sector—the gaming-tourism cluster. Model (7), which utilizes raw variables (levels specification) and focuses on the shock window, reveals a highly significant negative impact (p < 0.001), reaffirming the robustness of the core findings (Zeng & Zhang, 2012).

4.2.4. Qualitative Explanation of the Illusion Source

Although the TWFE model has confirmed the heterogeneity of the shock in terms of statistical significance, to further precisely quantify the specific contribution of the “denominator effect” to the decline in HHI, and to directly respond to the skepticism regarding whether “apparent diversification” stems from structural optimization, this study constructs a counterfactual simulation.

We established a counterfactual scenario: assuming the dominant industry (Gaming) was unaffected by the pandemic, its GVA remains at the 2019 baseline level (i.e., = 226,353 million MOP), while the GVA of all other industries varies according to actual observed values. Based on this assumption, we recalculated the “Counterfactual Total GVA” and the corresponding “Counterfactual HHI” for the years 2020 to 2023, comparing them with the “Observed HHI” calculated from actual data. The simulation results are detailed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Decomposition and Comparison of Observed HHI vs. Counterfactual HHI (2019–2023).

The simulation results reveal a highly illuminating phenomenon of divergence. As shown in Table 6, the Observed HHI declined precipitously during the severe shock period (2020–2022), dropping from 3165.48 in 2019 to a trough of 1324.58 in 2022. Superficially, this suggests a high level of diversification. In contrast, the Counterfactual HHI remained high (3300–3700) throughout the same period, even exceeding the 2019 baseline, even exceeding the 2019 baseline level.

This immense numerical divergence provides decisive evidence: the decline in the HHI was driven entirely by the collapse of Gaming GVA. Specifically, when Gaming GVA drastically contracted from 226,353 million MOP in 2019 to 29,821 million MOP in 2022, it caused the total economic output (the denominator, i.e., Total GVA) to passively contract from 423,425 million MOP to 202,323 million MOP. With the denominator halved, the relative shares of other non-gaming sectors would mathematically double even if their outputs remained constant, thereby mechanically depressing the HHI value.

The elevated level of the Counterfactual HHI (e.g., 3772.80 in 2020) further illustrates that, if the impact of the gaming collapse is excluded, the rest of Macao’s industrial structure did not undergo substantive structural diversification; in fact, it appeared even more concentrated due to the synchronous atrophy of other service sectors. Therefore, this study confirms that the “apparent diversification” observed in Figure 1 is unequivocally a “resilience illusion” triggered by the recession of a single dominant industry, rather than the result of endogenous structural transformation.

4.2.5. Sensitivity Check of Policy Severity Index Weights

In constructing the “Policy Severity Index” (PSI), the baseline model adopted a synthetic method of equal weighting (25% each) for the four policy dimensions (Isolation, Clearance, Visa, and Permission). However, given Macao’s economy’s high dependence on Mainland tourists, the actual weight of “Mainland border clearance stringency” (Dim2) on tourism mobility may be greater than that of other dimensions. To address concerns regarding the subjectivity of weight setting and to verify the robustness of the empirical results, this study conducted a sensitivity check.

We constructed an alternative “Weighted Policy Severity Index” by assigning a 50% weight to the “Clearance” dimension (which has the most direct impact on the Macao tourism market), a 30% weight to the “Overseas Quarantine” dimension, and reducing the weights of the “Visa” and “Foreign Entry Permission” dimensions to 10% each. Based on this weighted index, we re-estimated the TWFE baseline model.

The test results are shown in Table 7. After adopting the “clearance-oriented” weighted index, the coefficient estimate for the core interaction term (Policy_Weighted × Dummy) is −0.846. This is perfectly consistent in direction with the baseline model’s −0.756, and the magnitude of the effect is even more pronounced (the absolute value of the coefficient increased). The p-value improved from 0.114 to 0.107, and the model’s goodness of fit (R2) also saw a slight increase. These results indicate that the core finding of this study—that pandemic policies exerted a negative shock on visitor-facing sectors—is not driven by the weight selection in the index construction process. Even under extreme weighting assumptions, the asymmetry of the shock remains robust.

Table 7.

Sensitivity Check of Policy Index Weight Settings (TWFE Model Comparison).

4.3. Structural Lag in the Labor Market

The second core argument of this study (H2) posits that the pandemic shock has left deep “scars” on the labor market. To verify this, we combine a visual analysis of dynamic recovery trajectories with rigorous inter-group statistical tests.

4.3.1. The “Divergence Gap” in GVA, Employment, and Earnings

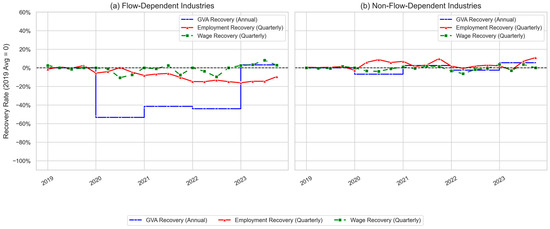

To visually demonstrate hypothesis H2a (Structural Lag), Figure 2 plots the recovery rates (using 2019 as the 0% baseline) for GVA, Employment, and Average Earnings for two groups: “Visitor-facing Sectors” (VisitorFacingDummy = 1) and “Non-visitor-facing Sectors” (VisitorFacingDummy = 0).

Figure 2.

Trajectories of Recovery Rates for GVA, Employment, and Earnings (2019–2023, by Industry Group).

Figure 2 provides compelling visual evidence supporting hypothesis H2. The two subplots exhibit distinct recovery patterns.

In Figure 2b “Non-visitor-facing Sectors”, the three curves for GVA (blue), Employment (red), and Earnings (green) remained relatively stable throughout the 2019–2023 period, clustering tightly around the 2019 baseline (0%). Data show that the GVA of this group declined only slightly by 6.9% in 2020, the year of the most severe pandemic impact, and rapidly recovered to above the baseline (+2.6%) in 2021. Both employment and earnings fluctuated only marginally around the baseline. This indicates that the impact of the pandemic shock on non-tourism-dependent sectors was transient and controllable, causing no long-term structural lag.

In sharp contrast, Figure 2a “Visitor-facing Sectors” reveals a clearly visible “divergence gap” within the tourism cluster. GVA (blue line) collapsed immediately in 2020 (−53.3%) and remained at a low level of −44.0% in 2022. Although employment (red line) and earnings (green line) also declined, their magnitude of decline was far smaller than that of GVA.

However, the core of hypothesis H2—“structural lag”—manifested most vividly during the recovery phase in 2023. In 2023, as tourism mobility fully resumed, GVA (blue line) rebounded rapidly, recovering to above the baseline (+3.15%). Yet, the recovery of the labor market significantly lagged behind. The employment rate (red line) did not rebound synchronously with GVA in 2023; instead, it remained persistently below the baseline (−16.1% in Q1 2023, and still −9.5% in Q4). The recovery of earnings (green line) also lagged; although it approached the baseline by the end of 2023, its recovery speed was significantly slower than that of GVA. This phenomenon of “decoupling”—where GVA output has recovered but labor (especially employment numbers) remains far from recovery—is a typical manifestation of the “lag effect” or “scarring effect” in the labor market (Yagan, 2019; Huckfeldt, 2022). This suggests that the shock was not merely cyclical but structural: after experiencing drastic fluctuations, tourism firms may have undergone a permanent shift in employment strategies, no longer tending to restore their workforce to pre-pandemic scales (Kalleberg, 2009).

To further statistically confirm that the “divergence gap” shown in Figure 2 is significant rather than a result of random fluctuations, this study conducted inferential tests on the average employment recovery rates of the two industry groups post-shock (2020–2023). We calculated the average employment recovery rate for each industry in the post-pandemic period and compared them by grouping them into “Visitor-Facing” (N = 5) and “Non-Visitor-Facing” (N = 9).

The statistical test results reveal a significant structural difference in labor recovery performance between the two groups (see Table 8). Descriptive statistics show that the average employment recovery rate for “Non-visitor-facing” sectors is positive (+10.68%), indicating that their employment scale has exceeded pre-pandemic levels. In contrast, the average recovery rate for “Visitor-facing” sectors is significantly negative (−7.60%), indicating that their workforce scale remains in a state of severe contraction. The average gap between the two reaches 18.28 percentage points.

Table 8.

Tests for Differences in Employment Recovery Rates Between Industry Groups (2020–2023 Average).

Given the small sample size (N = 14) and the potential for unequal variances, we employed both Welch’s t-test (parametric) and the Mann–Whitney U test (non-parametric) to ensure the robustness of the results. The test results show a t-statistic of −2.603 (p = 0.024) and a U-statistic of 6.0 (p = 0.029). The p-values for both tests are less than the 0.05 significance level, statistically confirming that the labor recovery speed of “Visitor-facing” sectors significantly lags behind that of other sectors. This provides conclusive econometric evidence for the hypothesis of “structural lag” in the labor market proposed in H2.

Table 9 further lists the specific recovery rate rankings for each industry, intuitively illustrating this heterogeneity. Data show that among the five industries with the lowest recovery rates, visitor-facing sectors accounted for four spots. Specifically, Gaming (−14.22%) and Hospitality (−13.81%) suffered the most severe labor contraction, exhibiting profound “scars”. In contrast, essential service sectors (characterized by inelastic demand) such as Electricity, Gas and Water (+51.95%), and Health and Social Welfare (+20.38%) exhibited robust expansionary trends. This extreme polarization between industries further corroborates that the pandemic shock, channeled through the specific mechanism of “tourism mobility”, inflicted asymmetric structural damage on specific labor markets.

Table 9.

Rankings of Average Employment Recovery Rates by Industry (2020–2023).

4.3.2. Evidence of “Scarring” in Job Quality

The “divergence gap” shown in Figure 2 reveals the lag in the labor market in terms of “quantity” (employment numbers), while hypothesis H2b further posits that this “scar” is also manifested in the decline of “quality” (job quality). Following an economic shock, to cope with future uncertainty and reduce rigid labor costs, firms may tend to increase “non-standard employment”, leading to “workforce casualization” (Matilla-Santander et al., 2021; W. J. Han & Hart, 2021). To test this mechanism, this study uses semi-annual labor data to analyze changes in “job quality” within “visitor-facing sectors”, specifically utilizing the “Full-time Ratio” (FT_Share) as the core metric (Picatoste et al., 2021).

We compared data from the pre-pandemic baseline (2019-H2) with the initial economic recovery phase (2025-H1). The results are shown in Table 10.

Table 10.

Changes in Job Quality in Key Visitor-Facing Sectors (2019-H2 vs. 2025-H1).

The results in Table 10 clearly reveal the “industrial heterogeneity” proposed in H2b: the “scars” in the labor market are not uniform but exhibit significant differentiation based on the labor “substitutability” of each industry.

The core findings of this study focus on “Transport and Communications” and “Catering”. “Transport and Communications” suffered the most severe structural damage: its full-time ratio dropped significantly from 93.5% to 88.5%, a net decrease of 5.0 percentage points. This provides the strongest support for H2b and represents a typical structural shift toward “workforce casualization”. In this sector, firms (e.g., land transport, logistics) significantly increased the use of part-time or temporary labor to manage the immense risks of tourism mobility fluctuations. Even more critically, Transport and Communications is the only sector among the five to also experience a decline in “average full-time earnings” (−4.64%), indicating “dual scarring” in terms of both “quality” and “price”.

“Catering” exhibited a similar trend of “workforce casualization”, with the full-time ratio dropping by 1.15 percentage points. The commonality between these two industries lies in the relatively high “substitutability” of their labor skills.

In contrast, “Gaming” and “Hospitality” demonstrated strong “skill rigidity”. Since employees in the gaming industry (e.g., dealers) typically require specialized skills or government licenses, their labor “non-substitutability” is high. Consequently, firms tended to engage in “labor hoarding” during the shock to retain their core workforce (Kuo, 2024). Table 10 confirms this: the full-time ratio in Gaming remained at an absolute high of over 99% and increased slightly (+0.51 pp); the Hospitality ratio also stabilized at 98.9%. Meanwhile, average full-time earnings in these two sectors achieved significant growth (+11.16% for Gaming, +8.07% for Hospitality).

“Retail” presents a third pattern: wage stagnation. Its full-time ratio remained stable, but average full-time earnings showed almost no growth over the six-year period (−0.80%), indicating that the “scar” in this sector is primarily reflected in the stagnation of wage growth.

In summary, the micro-evidence in Table 10 deeply deconstructs the macro “divergence gap” observed in Figure 2. The structural lag in the labor market (H2) is confirmed: after the GVA rebound, total employment recovery is slow (Figure 2), and in specific industries (Transport, Catering), this recovery comes at the cost of “workforce casualization” (decline in job quality). This poses a potential challenge to future service quality.

5. Discussion

This study utilizes counterfactual simulations and inferential statistical tests to quantitatively deconstruct the phenomenon of “apparent diversification” observed in Macao’s economy during the COVID-19 pandemic and to deeply analyze the heterogeneous scars left on the tourism labor market. The results not only confirm the “resilience illusion” driven by the denominator effect at the macro level but also reveal at the micro level how skill specificity leads to “structural divergence” within the tourism service workforce. This section will engage in a deep theoretical dialogue around these two core findings and explore their policy implications for building resilience in tourism mono-economies.

5.1. Passive Diversification and Resilience Illusion: Structural Paralysis of a Tourism Mono-Economy

For a long time, the HHI has been widely regarded as a barometer for measuring regional economic structure optimization. However, our counterfactual simulation reveals a different reality: the decline in Macao’s HHI was driven entirely by the “denominator effect” following the collapse of the gaming sector’s GVA. Once the recessionary impact is removed, the index shows no substantive structural optimization, the Counterfactual HHI not only failed to decline but remained at high levels, even exceeding those of 2019. This finding challenges the traditional resilience assessment narrative that views “crisis as an opportunity for structural transformation”, revealing a specific crisis response pattern—“passive diversification”. This phenomenon did not stem from the endogenous growth of non-gaming elements, but rather from the structural paralysis of the system’s core functions caused by the stalling of the tourism engine. In other words, the rise in the share of non-gaming sectors was merely a mathematical passive result, rather than a reflection of substantive competitiveness.

This severe divergence between macro indicators and economic substance provides new empirical evidence for recent academic discussions regarding the “misleading nature” of post-disaster recovery indicators. Similarly to the asymmetry in source market structures found in studies of Spanish tourism recovery (Galiano et al., 2025), and the warning in regional disaster research that a simple GDP rebound may mask social vulnerabilities (Clò et al., 2025), this study confirms that under extreme mobility shocks, the relative share indicators of a tourism mono-economy can emit “false signals”. These signals mislead policymakers into believing that the economic structure has automatically optimized; in essence, the decline in HHI caused by the shock to the dominant industry represents “path lock-in” rather than “path breaking”. For economies highly dependent on external flows, this “passive diversification” masks the urgency of pushing for genuine structural reform. Therefore, a true resilience assessment must move beyond single flow or share indicators. This study demonstrates that the counterfactual HHI analysis serves as a robust methodological tool to deconstruct the “denominator effect”. Future research on mono-economies should adopt similar structural considerations based on counterfactual scenarios to identify and filter out the “resilience illusion” driven by recession.

5.2. Skill Specificity and the Dual Divergence Mechanism in the Tourism Labor Market

At the micro level, our structural analysis reveals that the tourism labor market did not experience a homogeneous decay when responding to the shock. Instead, a significant “dual-path” divergence emerged: the coexistence of “labor hoarding” in sectors with high skill specificity and “workforce casualization” in sectors with low skill thresholds. This finding provides a new micro-perspective for understanding the complex adjustment mechanisms of the service labor market under crisis shocks.

The first path appears in the gaming and luxury hospitality sectors. Despite suffering severe blows to GVA, these sectors maintained extremely high full-time ratios (>98%) and even witnessed wage growth. This “anomalous” labor retention behavior is rooted in the unique “skill specificity” of the tourism service industry. Gaming operators and five-star hotels tend to retain core employees through internal incentive mechanisms, as these strictly screened staff—who hold government licenses (e.g., dealers) and are familiar with specific luxury service standards—entail high replacement and training costs (King & Tang, 2020). When firms anticipate the demand shock to be temporary, they strategically “hoard” these core talents with specific skills to avoid hiring friction costs during the recovery period (Radlinska & Gardziejewska, 2022). Although this hoarding behavior protects employment stability in the short term, it generates a “lock-in effect”. It solidifies high-quality labor within traditional gaming service paths, hindering their flow toward emerging industries (such as MICE and technology) in the “1 + 4” strategy, thereby forming a kind of “defensive rigidity”.

The second path appears in the transport and catering sectors, characterized by a significant decline in full-time ratios (−5.0 pp) and a contraction in real earnings. Unlike the gaming industry, these sectors possess higher skill universality and strong labor substitutability, making them the primary targets for corporate cost control when facing shocks. This corroborates the view that the pandemic has amplified the long-existing precarity of tourism employment to an extreme (Baum et al., 2020). Firms leverage the gig economy to convert rigid labor costs into variable ones, effectively transferring market risks. Although this strategy alleviates short-term financial pressure, it severely undermines job security and organizational commitment (Jung et al., 2021; Xiao et al., 2022). Data show that this structural divergence has exacerbated “dual inequality” within the tourism labor market: a segment of core service personnel is “protected” but may fall into path lock-in, while another segment of basic service personnel is forced to bear the cost of “precarious work”. This potential decline in service quality poses a threat to the destination’s long-term competitiveness.

5.3. From Aggregate Relief to Precision Repair: Evidence-Based Policy Pathways

Based on the deep analysis of the “resilience illusion” and “structural divergence”, future policy interventions should shift from generalized “aggregate relief” to “precision structural repair” based on industry characteristics. Addressing the dual scars emerging in the tourism labor market, we propose a targeted two-track strategy.

First, for the transport and catering sectors where the trend of “casualization” is evident, the policy focus should be on establishing a flexible employment safety net. This study finds a significant decline in full-time ratios in these sectors, implying that a large number of tourism service workers have shifted into the unprotected gig market, facing the dilemma of an “absence of safety nets” (Ravenelle et al., 2021). Therefore, the government should establish social protection mechanisms adapted to the characteristics of the gig economy (Katiyatiya & Lubisi, 2025). Specifically, it should explore the establishment of a “Tourism Seasonality Adjustment Fund”, providing trigger-based subsidies for gig workers dependent on tourist flows during off-seasons or shock periods. Simultaneously, a “pay-per-order” micro-social insurance system should be established, allowing platform practitioners such as chartered bus drivers and food delivery riders to contribute to work injury and medical insurance based on working hours or orders. This is not only a protection for vulnerable workers but also a necessary measure to prevent the permanent loss of grassroots service talent due to deteriorating job quality.

Second, for the gaming and hospitality sectors where “labor hoarding” has occurred, the policy focus should shift toward implementing “reskilling” to unlock path dependence. For the large volume of full-time labor “hoarded” by large leisure enterprises, the policy goal should be to prevent them from becoming sunk costs that hinder industrial diversification. The government should utilize the recovery window to implement active labor market policies (ALMPs), particularly upgrading the skills of seasonal and cyclical tourism workers (Fasone & Pedrini, 2023). Establishing public–private partnerships (PPPs) is crucial in this process (Khandii et al., 2025). The government can subsidize gaming enterprises to conduct retraining for digital transformation and non-gaming businesses (e.g., MICE planning, entertainment management, smart tourism applications), transforming “passively hoarded” single-skill service personnel into composite talents driving the “1 + 4” adequate diversification strategy. This will not only alleviate human capital cost pressures on firms but also enhance labor transferability, thereby truly elevating the evolutionary resilience of the tourism economic system against future shocks.

6. Conclusions

This study aims to investigate the deep-seated impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic—a unique exogenous shock—on Macao, a mono-economy highly dependent on “tourism mobility”. Focusing on the counter-intuitive decline in the HHI during the pandemic, this study deconstructed the underlying mechanisms and assessed the structural consequences on the labor market.

6.1. Summary of Core Findings

The core findings of this study can be summarized in two points:

First, the study successfully deconstructed that the “apparent diversification” exhibited by Macao’s economy under the pandemic shock was, in reality, a “resilience illusion” (H1). Our counterfactual HHI analysis proved particularly effective in identifying the source of statistical distortion. Through this simulation, we confirmed that, the Counterfactual HHI did not decline during the pandemic and even exceeded 2019 levels. This indicates that the observed HHI decline was a mathematical artifact driven entirely by the “denominator effect”. TWFE model results confirm that border controls disproportionately impacted “visitor-facing” sectors. The rising share of other sectors was merely passive. Thus, “apparent diversification” reflects a macro-indicator trap driven by the stalled tourism engine rather than genuine structural optimization.

Second, the study reveals that the shock caused significant and heterogeneous “structural lag” and “dual divergence” in Macao’s labor market (H2). Inferential statistical tests confirmed that the employment recovery speed of visitor-facing sectors lagged significantly behind that of non-visitor-facing sectors. Micro-structural analysis further found two distinct adjustment paths based on differences in “skill specificity”: in the transport and catering sectors, where skill universality is higher, a structural shift toward “workforce casualization” occurred, manifested by a significant drop in the full-time ratio (−5.0 pp); conversely, in the gaming and hospitality sectors, where skill specificity is stronger, firms tended toward “labor hoarding”, maintaining extremely high full-time ratios. This suggests that the pandemic shock not only caused employment losses in aggregate terms but also structurally led to a dual polarization in job quality—with one segment of the workforce facing intensified precarity and the other facing path lock-in risks.

6.2. Policy Implications

Based on these findings, this study advises policymakers to move beyond the singular pursuit of aggregate indicators (such as tourist arrivals and GDP) and turn toward precision repair of the labor market structure. Specifically, a “two-track” intervention strategy should be implemented: For transport and catering sectors showing “casualization” trends, a flexible employment safety net should be established. We suggest setting up a “tourism practitioner income fluctuation compensation fund” and promoting “pay-per-order” micro-social insurance. This aims to repair the social security chain fractured by the loss of full-time positions and prevent the permanent loss of grassroots service talent. For gaming and hospitality sectors showing “labor hoarding”, a “reskilling” strategy should be implemented. The government should utilize the recovery window to fund enterprises in conducting retraining focused on digitalization and non-gaming businesses. This will transform passively hoarded human resources into active reserves driving appropriate economic diversification, thereby unlocking path dependence and enhancing the evolutionary resilience of the economic system.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

This study also has several limitations. First, the counterfactual simulation is based on the static assumption that “Gaming GVA remains at 2019 levels”. While this effectively isolated the denominator effect, it did not account for potential dynamic general equilibrium effects (e.g., inter-industry spillover effects). Second, the classification of the core explanatory variable “visitor-facing” was based on qualitative standards. Although verified through multiple rounds of coding, future research could explore constructing continuous dependency metrics based on Input-Output (I-O) tables or mobile signaling data. Third, limited by data availability, the analysis of “casualization” relied primarily on changes in full-time ratios and failed to directly measure the specific working hours and welfare conditions of gig workers.

Future research could further track the long-term healing of these labor market “scars”, particularly focusing on the career mobility trajectories of “hoarded” labor and whether the trend of “casualization” reverses as tourism demand recovers. Furthermore, applying the analytical framework of this study to comparative research on other tourism mono-destinations (such as the Maldives or Las Vegas) would help distill a more generalizable theory of resilience management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C. and Y.Y.; methodology, C.W.; software, C.W.; validation, H.H. and W.I.H.; formal analysis, C.W., W.I.H. and K.I.C.; data curation, J.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C., H.H. and Y.Y.; writing—review and editing, C.W., W.I.H., K.I.C. and Y.Y.; visualization, C.W. and H.H.; supervision, Y.Y.; project administration, J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in FigShare at http://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30703511.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table A1.

Evolution of Major Entry-Exit Policies in Macao During the COVID-19 Pandemic (2020–Early 2023).

Table A1.

Evolution of Major Entry-Exit Policies in Macao During the COVID-19 Pandemic (2020–Early 2023).

| Effective Date | Policy Change Summary | Affected Regions/Populations | Key Requirements (Quarantine, Testing, Health Code, etc.) | Main Source Authority |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 January 2020 | Implementation of border temperature screening | All entrants, esp. from Wuhan | Body temperature checks; Health Declaration Form required | Health Bureau/CPSP |

| 27 January 2020 | Restrictions on Hubei travelers; shortened Border Gate hours | Travelers from Hubei province; all users of the Border Gate | Entry denied for Hubei residents; Border Gate operating hours shortened to 06:00–22:00 | Health Bureau/CPSP |

| 18 March 2020 | Ban on all non-resident foreigners (exempting residents of Mainland, HK, TW, and non-resident workers) | Non-resident foreign nationals | Entry prohibited | GCS/CPSP |

| 25 March 2020 | Expansion of entry ban; suspension of airport transit services | Residents of Mainland, HK, TW with foreign travel history in past 14 days | Entry prohibited; 14-day Centralized Medical Observation imposed on eligible entrants (e.g., Macao residents) | GCS/CPSP |

| 3 May 2020 | Official launch of the “Macao Health Code” system | All Macao residents and entrants | Required as a health credential for local and cross-border movement | Health Bureau |

| 11 May 2020 | Mutual recognition of NAT results with Zhuhai; quarantine exemption for specific groups | Macao non-resident workers living in Zhuhai | Exempt from 14-day quarantine with valid negative Nucleic Acid Test (NAT) | Health Bureau/Zhuhai-Macao Joint Mechanism |

| 15 July 2020 | Lifting of centralized quarantine for Guangdong-Macao travel | Eligible persons traveling between Guangdong and Macao | Quarantine-free border clearance with valid 7-day negative NAT and Green Health Code | Health Bureau/Guangdong-Macao Joint Mechanism |

| 12 August 2020 | Quarantine-free entry to Mainland from Macao; Resumption of Zhuhai tourist visas | All persons entering Mainland from Macao; Zhuhai residents | Quarantine-free entry to Mainland with 7-day negative NAT | NIA/Zhuhai-Macao Joint Mechanism |

| 23 September 2020 | Nationwide resumption of Mainland tourist visas to Macao | All Mainland residents | Marked the full reopening to the primary source market (Group tours and IVS) | NIA/MGTO |

| 21 January 2021 | Implementation of “Quarantine + Self-health Management” model | All entrants requiring medical observation | 14 days centralized quarantine + 14 days self-health management; or 21 + 7 days | Health Bureau |

| 16 May 2021 | Extension of medical observation for Taiwan entrants to 21 days | Entrants with travel history to Taiwan | 21 days Centralized Medical Observation | Health Bureau |

| 5 August 2021 (Approx) | Shortening of NAT validity at Zhuhai-Macao borders (fluctuating between 12/24/48 h) | Persons traveling via Zhuhai-Macao land borders | traveling via Zhuhai-Macao land borders; Short-term tightening of NAT validity duration | Health Bureau/Zhuhai-Macao Joint Mechanism |

| 6 August 2022 | Adjustment to “7 + 3” Model | Entrants from HK, TW, and foreign regions | 7 days centralized quarantine + 3 days self-health management (Yellow Code) | Health Bureau/GCS |

| 12 November 2022 | Adjustment to “5 + 3” Model | Entrants from HK, TW, and foreign regions | 5 days centralized quarantine + 3 days home isolation (Red Code) | Health Bureau/GCS |

| 9 December 2022 | Cancelation of on-arrival NAT | All entrants | Mandatory post-entry NAT canceled, but pre-entry negative proof still required | Health Bureau |

| 8 January 2023 | Comprehensive relaxation of entry and transit measures | All entrants | No testing for Mainland/HK/TW entrants; 48h Antigen/NAT for foreigners; All quarantine abolished | Health Bureau/GCS |

| 6 February 2023 | Full resumption of personnel exchange between Mainland and HK/Macao | All persons traveling between Mainland and Macao | Cancelation of all remaining restrictions; restoration of pre-pandemic border norms | State Council Joint Mechanism |

Note: This table is compiled based on public information; specific implementation details were subject to dynamic adjustments based on the situation. Main information sources include announcements and press releases from the Macao SAR Government Information Bureau (GCS), Health Bureau (SSM), Public Security Police Force (CPSP), Macao Government Tourism Office (MGTO), National Immigration Administration (NIA), and the Guangdong-Macao/Zhuhai-Macao Joint Prevention and Control Mechanisms.

Appendix A.2

The core grouping variable of this study, VisitorFacingDummy (Visitor-Facing Grouping), was determined based on a qualitative classification method. We classified the 14 industries into binary categories (0 or 1) primarily based on the following two criteria:

Nature of the Business Model: Assessing whether the industry’s Gross Value Added (GVA) and core operations rely directly on the Physical Presence and Tourism Mobility of customers (especially tourists).

Official Documentary Evidence: Referencing definitions of “tourism-related industries” in official documents, such as the Analysis Report on Statistical Indicator System for Macao’s Economic Diversification published by the Statistics and Census Service (DSEC).

To ensure the objectivity of the classification, the research team (comprising three research assistants) conducted multiple rounds of independent coding. During the initial coding phase, we calculated the inter-coder reliability (Krippendorff’s Alpha), achieving a high consistency level of 0.935. Subsequently, the research team resolved all inconsistent classifications through group discussion, deliberating on each of the 14 industries one by one until a consensus was reached.

The classification results and rationales are presented in the table below:

Table A2.

Classification Criteria and List for “Visitor-Facing” Industries (VisitorFacingDummy).

Table A2.

Classification Criteria and List for “Visitor-Facing” Industries (VisitorFacingDummy).

| Unified Industry (14 Categories) | VisitorFacingDummy | Classification Rationale (Nature of Industry) |

|---|---|---|

| Gaming | 1 | GVA and service consumption strictly rely on the physical presence of tourists. |

| Hospitality | 1 | GVA and service consumption strictly rely on the physical presence of tourists. |

| Retail | 1 | GVA (especially luxury goods and souvenirs) relies heavily on the physical presence and consumption of tourists. |

| Catering | 1 | GVA (especially high-end dining) relies heavily on the physical presence and consumption of tourists. |

| Transport and Communications | 1 | Core operations (passenger transport, roaming, aviation) rely directly on the physical cross-border mobility of tourists. |

| Finance | 0 | GVA derives mainly from interest, commissions, and investments; does not rely directly on the physical presence of customers. |

| Construction | 0 | GVA derives from engineering projects; does not rely directly on current tourist flows. |

| Electricity, Gas and Water | 0 | GVA derives from public utilities, primarily serving local needs; does not rely directly on tourist flows. |

| Manufacturing | 0 | GVA derives from commodity production (mostly for export or local consumption); does not rely directly on tourist flows. |

| Real Estate and Business Activities | 0 | GVA derives mainly from rents and business services; does not rely directly on current tourist flows. |

| Health and Social Welfare | 0 | GVA derives mainly from serving local residents; does not rely directly on tourist flows. |

| Education | 0 | GVA derives from teaching services; does not rely directly on tourist flows. |

| Public Administration | 0 | GVA derives from government services; does not rely directly on tourist flows. |

| Other Services | 0 | Primarily includes services for local residents (e.g., security, cleaning); does not rely directly on tourist flows. |

Appendix A.3

The 14 unified industry categories employed in this study were established by harmonizing and aggregating the original industry classifications from the Gross Value Added (GVA) and labor statistics published by the Statistics and Census Service (DSEC) of Macao.

To ensure the rigor and consistency of the classification, the research team (comprising three research assistants) conducted independent coding based on DSEC’s official industry definitions. During the initial coding phase, we calculated the inter-coder reliability coefficient (Krippendorff’s Alpha), achieving a high consistency level of 0.918. Subsequently, the research team resolved all inconsistent classifications through discussion to reach the final harmonized scheme.

The correspondence table is shown below:

Table A3.

Industry Classification Harmonization.

Table A3.

Industry Classification Harmonization.

| Unified Industry (14 Categories) | Corresponding Original DSEC GVA/Labor Classification (Examples) |

|---|---|

| Gaming | Gaming and Junket Activities |

| Hospitality | Hotel Industry (Hotels and Similar Establishments) |

| Retail | Retail Trade |

| Catering | Restaurants and Similar Establishments |

| Transport and Communications | Transport, Storage, and Communications |

| Finance | Financial Activities (including Banking, Insurance, Other Financial Intermediation, etc.) |

| Construction | Construction |

| Electricity, Gas and Water | Electricity, Gas, and Water Supply |

| Manufacturing | Manufacturing |

| Real Estate and Business Activities | Real Estate Activities; Business Services |

| Health and Social Welfare | Health Services; Social Welfare Services (e.g., Child Care, Elderly Care) |

| Education | Education |

| Public Administration | Public Administration |

| Other Services | Other Services (e.g., Security Services, Sewage/Waste Management, Cultural/Recreational/Sports Activities) |

References

- Aguiar-Quintana, T., Nguyen, T. H. H., Araujo-Cabrera, Y., & Sanabria-Díaz, J. M. (2021). Do job insecurity, anxiety and depression caused by the COVID-19 pandemic influence hotel employees’ self-rated task performance? The moderating role of employee resilience. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J. S. (2009). Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajrami, D. D., Terzić, A., Petrović, M. D., Radovanović, M., Tretiakova, T. N., & Hadoud, A. (2021). Will we have the same employees in hospitality after all? The impact of COVID-19 on employees’ work attitudes and turnover intentions. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltagi, B. H., Bresson, G., & Etienne, J.-M. (2024). A pretest estimator for the two-way error component model. Econometrics, 12(2), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, T., Mooney, S. K. K., Robinson, R. N. S., & Solnet, D. (2020). COVID-19’s impact on the hospitality workforce—New crisis or amplification of the norm? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(9), 2813–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-C., Zou, S., & Chen, M.-H. (2022). The fear of being infected and fired: Examining the dual job stressors of hospitality employees during COVID-19. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 102, 103131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z. (2024). Exploration and prospect of Macao’s appropriate economic diversification upon the 25th anniversary of return. Asia-Pacific Economic Review, 5, 174–184. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., & Yang, X. (2022). Research on the development of industrial chain relationship between Macao and mainland China after COVID-19. Asia-Pacific Economic Review, 2, 146–152. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T., Ma, L., Zhao, Y., & Zhao, C. (2024). Large-scale and rapid perception of regional economic resilience from data-driven insights. International Journal of Digital Earth, 17(1), 2365971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clò, S., Ciulla, L., Martellozzo, F., Gatto, A., & Segoni, S. (2025). Creative destruction revisited: Regional impacts of natural disasters beyond GDP. Regional Studies, 59(1), 2546973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corden, W. M. (1984). Booming sector and dutch disease economics: Survey and consolidation. Oxford Economic Papers, 36(3), 359–380. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2662669 (accessed on 5 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z., Guo, L., & Luo, Q. (2019). Market concentration measurement, administrative monopoly effect and efficiency improvement: Empirical data from China civil aviation industry 2001–2015. Applied Economics, 51(34), 3758–3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasone, V., & Pedrini, G. (2023). Industry-specific upskilling of seasonal tourism workers: Does occupational gender inequality matter? Tourism Economics, 29(7), 1915–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, P., Dwyer, L., & Spurr, R. (2014). Is Australian tourism suffering Dutch Disease? Annals of Tourism Research, 46, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiano, A., Martín-Álvarez, J. M., & Mata, L. (2025). Spanish tourism’s post-pandemic recovery: Insights from a market source-specific approach. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haisch, T. (2018). Interplay between ecological and economic resilience and sustainability and the role of institutions: Evidence from two resource-based communities in the Swiss Alps. Resilience-International Policies Practices and Discourses, 6(3), 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C. M., Prayag, G., & Fang, S. (2024). Destination transitions and resilience following trigger events and transformative moments. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 24(4–5), 390–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H., Lee, K.-S., Kim, S., Wong, A. K. F., & Moon, H. (2022). What influences company attachment and job performance in the COVID-19 era?: Airline versus hotel employees. Tourism Management Perspectives, 44, 101001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]